John Elder Robison's Blog, page 4

November 13, 2017

If you could change autism research today, what would you do?

Recently I suggested that people who are actually autistic need to have a strong voice in guiding autism research. I made the point that anyone who is not autistic is simply guessing when it comes to interpreting our behaviors. Only an autistic person can truly know autistic life. That is not a slight against parents; it is just reality.

Some autistic people are parents too, and they have both perspectives. That’s particularly valuable. And parents as a group are the only ones who can report fully on the development of very young children who can’t speak for themselves.

But it leaves a fundamental question unanswered. If I believe autistic people should have a strong voice in guiding research, what would I ask for?

Autism is a difference that affects us through the lifespan. Childhood is 20-25% of the typical lifespan. Less than 5% of current research is directed toward understanding adult issues. I would shoot for 50% of newly funded research addressing at either adult or full lifespan issues.

I’d require that proposed research include a statement from autistic community members about the methodology, utility, and ethics of the proposed study. I’d expect at least half the community members to be actual autistic people with the others being parents and professionals.

As for the topics of study . . .

I’d make the study of apparent early mortality of autistic people a top priority. Why does it happen and what can we do?

The initial findings on suicide and suicidal ideation are scary enough that I think that area deserves its own concentration of study.

I’d put considerably more emphasis on understanding the co-occurring conditions that accompany autism. Epilepsy, anxiety, intestinal issues, depression, and others. Most of these conditions seem more resistant to treatment or control in autistic people. Why is that and what can we do? If we could control or remediate these symptoms we’d be a lot closer to minimizing autistic disability.

Look at epilepsy in the general population. Successful management via meds means no seizures. Now look at many autistics - same meds every day, but seizures still happen. Poor control. Or take depression. Autistic and non autistic mostly manage with meds. Yet we autistics are nine times more likely to kill ourselves. Why are our outcomes so much worse?

Many autistic people have sleep problems. That is another co occurring condition that merits more study. The number of problems associated with these co-occcurring conditions make me think that a large fraction of the pain and suffering we autistics experience comes from those things, and if we could relieve that it would be a really big deal.

I’d encourage research aimed at improving communication skills, both verbal and non verbal. We've funded programs like PEERS and UNSTUCK to tremendous benefit.

I’d encourage research into improving executive function for autistic people at all levels of support.

I’d figure out how to expand apprenticeship/work training programs like Project Search that can transition both low and high support autistic people into the workforce. These projects have shown very encouraging results but we don’t know how to replicate them widely.

I’d seek research proposals from engineering and industrial design people looking for innovative solutions to help non speaking autistics communicate. We have letter and symbol boards, and ipad versions of same, but I think there is a lot more potential there. Unlocking communication is the biggest thing we could do to relieve disability in some people.

I’d study other ways technology could be used to minimize our autistic disabilities. We think of autism as something we’ll address through medical treatment or behavioral therapy but there is tremendous promise for help through engineering.

I’d study the housing options for adults who cannot live independently. Sharp differences exist between supporters of community and individual apartment housing. We should agree that we need safe, supportive, affordable housing options that parents can trust when they can no longer care for higher support adult children at home.

I’d figure out how to extend the supports given to autistic people through high school into adulthood.

I’d tackle the pressing questions the IACC has collectively identified in the 2017 Strategic Plan Update.

Finally, I’d ask the community what their concerns are and synthesize them into a revised plan.

This is far from a complete list, but it’s a start

John Elder Robison

John Elder Robison is an autistic adult and advocate for people with neurological differences. He's the author of Look Me in the Eye, Be Different, Raising Cubby, and Switched On. He serves on the Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee of the US Dept of Health and Human Services and many other autism-related boards. He's co-founder of the TCS Auto Program (A school for teens with developmental challenges) and he’s the Neurodiversity Scholar in Residence at the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia and a visiting professor of practice at Bay Path University in Longmeadow, Massachusetts.

The opinions expressed here are his own. There is no warranty expressed or implied. While reading this essay will give you food for thought, actually printing and eating it may make you sick. (c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

Published on November 13, 2017 20:27

October 23, 2017

A Change in Direction for the Federal Autism Committee

I am pleased to see that our government’s understanding of autism is changing. For the first time, the IACC’s Strategic Plan recognizes that the needs of people living with autism today are paramount. This portion of the introduction to the 2016-17 Update speaks for itself:

The IACC has moved toward a paradigm shift in how we approach autism. A few years ago, scientists saw autism as a disorder to be detected, treated, prevented and cured. The majority of research was directed at understanding the genetic and biological foundations of autism, and toward early detection and intervention.

Today, our understanding of autism is more nuanced. We realize that there are many different “autisms” – some severe, and some comparatively mild – and that ASD affects several distinct domains of functioning differently in each individual. We have come to understand that autism is far more common than previously suspected and there are most likely many undiagnosed children, adolescents, and adults in the population, as well as under-identified and underserved individuals and groups, such as girls/women with ASD, people in poorly resourced settings, members of underserved minority communities, and individuals on the autism spectrum with language and/or intellectual disabilities.

Most importantly, individuals on the autism spectrum have become leading voices in the conversation about autism, spurring acknowledgment of the unique qualities that people on the autism spectrum contribute to society and promoting self-direction, awareness, acceptance and inclusion as important societal goals.

Research on genetic risk and the underlying basic biology of ASD remains a primary focus of the research portfolio and does play an important long-term role in the potential to develop new and broadly beneficial therapies and interventions. These advances may one day mitigate or even eliminate some of the most disabling aspects of autism, especially for those on the spectrum who are most severely impacted.

However, balanced with the potential for long term efforts to lead to significant future advance and opportunities, is the importance of efforts that can have a more immediate impact. Individuals on the autism spectrum today will remain autistic for the foreseeable future; most of them have significant unmet needs. To help those people – who range in age from infants to senior citizens – we must in the short-term translate existing research to develop effective tools and strategies to maximize quality of life, and minimize disability, while also ensuring that individuals on the autism spectrum are accepted, included, and integrated in all aspects of community life.

The community has been very clear in its calls for more research into adult issues and better services and supports for the millions of Americans living with autism today. Recent studies of adult mortality have indicated that people with ASD are at higher risk of premature death than people in the general population, painting a very disturbing picture that bears investigation. In light of data and insights from the community, the IACC proposes a comprehensive research agenda that addresses the needs of autistic people across the spectrum and across the lifespan, including improvements to services, supports, and policies. The IACC also believes that, as many in the autism community have indicated, efforts to address the many co-occurring conditions that accompany autism should be made a greater priority.

IACC in session, at NIH in Bethesda MD J E Robison photo

IACC in session, at NIH in Bethesda MD J E Robison photo

(c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

The IACC has moved toward a paradigm shift in how we approach autism. A few years ago, scientists saw autism as a disorder to be detected, treated, prevented and cured. The majority of research was directed at understanding the genetic and biological foundations of autism, and toward early detection and intervention.

Today, our understanding of autism is more nuanced. We realize that there are many different “autisms” – some severe, and some comparatively mild – and that ASD affects several distinct domains of functioning differently in each individual. We have come to understand that autism is far more common than previously suspected and there are most likely many undiagnosed children, adolescents, and adults in the population, as well as under-identified and underserved individuals and groups, such as girls/women with ASD, people in poorly resourced settings, members of underserved minority communities, and individuals on the autism spectrum with language and/or intellectual disabilities.

Most importantly, individuals on the autism spectrum have become leading voices in the conversation about autism, spurring acknowledgment of the unique qualities that people on the autism spectrum contribute to society and promoting self-direction, awareness, acceptance and inclusion as important societal goals.

Research on genetic risk and the underlying basic biology of ASD remains a primary focus of the research portfolio and does play an important long-term role in the potential to develop new and broadly beneficial therapies and interventions. These advances may one day mitigate or even eliminate some of the most disabling aspects of autism, especially for those on the spectrum who are most severely impacted.

However, balanced with the potential for long term efforts to lead to significant future advance and opportunities, is the importance of efforts that can have a more immediate impact. Individuals on the autism spectrum today will remain autistic for the foreseeable future; most of them have significant unmet needs. To help those people – who range in age from infants to senior citizens – we must in the short-term translate existing research to develop effective tools and strategies to maximize quality of life, and minimize disability, while also ensuring that individuals on the autism spectrum are accepted, included, and integrated in all aspects of community life.

The community has been very clear in its calls for more research into adult issues and better services and supports for the millions of Americans living with autism today. Recent studies of adult mortality have indicated that people with ASD are at higher risk of premature death than people in the general population, painting a very disturbing picture that bears investigation. In light of data and insights from the community, the IACC proposes a comprehensive research agenda that addresses the needs of autistic people across the spectrum and across the lifespan, including improvements to services, supports, and policies. The IACC also believes that, as many in the autism community have indicated, efforts to address the many co-occurring conditions that accompany autism should be made a greater priority.

IACC in session, at NIH in Bethesda MD J E Robison photo

IACC in session, at NIH in Bethesda MD J E Robison photo

(c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

Published on October 23, 2017 06:33

August 19, 2017

A Death in the Night, and Pause for Thought

This morning I arrived work to a disturbing piece of news. “A pedestrian got killed by a car last night in . . . .” Our complex is home to a fleet of emergency ambulances and we hear lots of things, but deaths still stand out.

“She used to live at the State School,” and “I remember seeing her cross the street with her cat on a leash. Inside a cat carrier box. Just pulling it along behind her.” “She would just walk out in front of cars, and I guess one finally got her.” Later, comments following a newspaper article would describe her as eccentric, and “Our town’s most famous pedestrian.”

I perked my ears up at that, because the Belchertown State School was where teachers threatened to send me, forty years earlier, when I failed to meet their behavioral expectations. The State School was a nasty place, a school in name only; a nasty warehouse for autistic and intellectually disabled people.

That reflection and the news story made me wonder . . . was the person who was killed autistic? I have no idea, but the way her story was presented gave me pause for thought. When a young autistic person is hit by a car, parents furnish the headlines, which usually read something like this: “Autistic teen killed by car in terrible accident.” The danger of wandering is often cited.

When researchers gather statistics on wandering deaths they look for headlines like that, and tally them up. But what happens to the autistic people who get old, and have no parents to tell their story when they step in front of traffic? People in the community shake their heads, and remember their eccentricity. Some remember the institution where they used to live. The headlines are noncommittal; “Pedestrian killed in late night crash.”

The cause could be anything.

That story made me realize two things:

The role of autism and developmental difference in deaths of adults with disabilities is almost certainly significantly underreported when older people don’t have parents or others to present that part of the story. Children "die from wandering." Older people are just one more casualty, "hit by a car."

Parents who are concerned that their autistic child will walk in front of a car someday are right to be worried about what may happen when they are gone. Many of us remain oblivious to cars and other dangers our whole lives, and for some, life is cut short as a result. Yet our freedom is precious, and not likely taken away or constrained, even when it leads us into danger.

Wandering presents the autism community with a difficult moral dilemma. Autistic advocates argue that the “wandering” some parents call out is really an effort to satisfy curiosity or escape a stressful situation. While that is surely true some of the time, what if the person’s escape takes them into the path of an oncoming car?

We’ve discussed this more than once at IACC, without seeing any good solutions. Tracking devices don’t prevent people from falling in water or dying in roadways. Locks present a whole host of problems as a type of restraint. Supervision sounds like a good answer, but very expensive and frankly impractical on a 24/7 basis.

At some point, most cognitively disabled people are either left unsupervised in the community, or they end up in a group home, jail or some other form of institutionalization. Many die early from accident or neglect. And of those deaths, the contribution of cognitive disability to the premature mortality (for whatever reason) surely often goes overlooked.

In the case that caught my eye, the headline simply said, “Woman struck and killed by car.”

Would you – as a reader – have felt different if the headline had said, Intellectually disabled woman . . ., or, Autistic woman . . .?

I think the addition of either of those words would have implied a connection between cognitive disability and the death. They would give readers pause for thought, and perhaps make people think that some of the folks wandering the streets are more vulnerable to unwittingly step in front of a car than others.

But who would add the words? The sad truth is, many cognitively disabled people live lonely lives, and at the end, there may be no one to tell our story.

I believe we have a duty to protect the vulnerable members of our society. At the same time, I understand the feelings of those who say we should not have a duty to protect against stupidity. It’s a matter of context. People rightly object when our Coast Guard spends thousands to rescue drunken boaters. The rescue of children and cognitively disabled people is a very different story because they do not “know better,” and often cannot help themselves.

If you agree with me, give some thought to the question. Where do you think people with cognitive disabilities should live as adults? If you agree the community is best, how might we protect people while still respecting free choice and self determination? Can we, and should we even try? Does the protection we extend to children just run out at some point in adulthood?

These are difficult ethical questions and they don’t have easy answers.

John Elder Robison is an autistic adult and advocate for people with neurological differences. He's the author of Look Me in the Eye, Be Different, Raising Cubby, and Switched On. He serves on the Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee of the US Dept of Health and Human Services and many other autism-related boards. He's co-founder of the TCS Auto Program (A school for teens with developmental challenges) and he’s the Neurodiversity Scholar in Residence at the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia and a visiting professor of practice at Bay Path University in Longmeadow, Massachusetts.

The opinions expressed here are his own. There is no warranty expressed or implied. While reading this essay will give you food for thought, actually printing and eating it may make you sick.

(c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

“She used to live at the State School,” and “I remember seeing her cross the street with her cat on a leash. Inside a cat carrier box. Just pulling it along behind her.” “She would just walk out in front of cars, and I guess one finally got her.” Later, comments following a newspaper article would describe her as eccentric, and “Our town’s most famous pedestrian.”

I perked my ears up at that, because the Belchertown State School was where teachers threatened to send me, forty years earlier, when I failed to meet their behavioral expectations. The State School was a nasty place, a school in name only; a nasty warehouse for autistic and intellectually disabled people.

That reflection and the news story made me wonder . . . was the person who was killed autistic? I have no idea, but the way her story was presented gave me pause for thought. When a young autistic person is hit by a car, parents furnish the headlines, which usually read something like this: “Autistic teen killed by car in terrible accident.” The danger of wandering is often cited.

When researchers gather statistics on wandering deaths they look for headlines like that, and tally them up. But what happens to the autistic people who get old, and have no parents to tell their story when they step in front of traffic? People in the community shake their heads, and remember their eccentricity. Some remember the institution where they used to live. The headlines are noncommittal; “Pedestrian killed in late night crash.”

The cause could be anything.

That story made me realize two things:

The role of autism and developmental difference in deaths of adults with disabilities is almost certainly significantly underreported when older people don’t have parents or others to present that part of the story. Children "die from wandering." Older people are just one more casualty, "hit by a car."

Parents who are concerned that their autistic child will walk in front of a car someday are right to be worried about what may happen when they are gone. Many of us remain oblivious to cars and other dangers our whole lives, and for some, life is cut short as a result. Yet our freedom is precious, and not likely taken away or constrained, even when it leads us into danger.

Wandering presents the autism community with a difficult moral dilemma. Autistic advocates argue that the “wandering” some parents call out is really an effort to satisfy curiosity or escape a stressful situation. While that is surely true some of the time, what if the person’s escape takes them into the path of an oncoming car?

We’ve discussed this more than once at IACC, without seeing any good solutions. Tracking devices don’t prevent people from falling in water or dying in roadways. Locks present a whole host of problems as a type of restraint. Supervision sounds like a good answer, but very expensive and frankly impractical on a 24/7 basis.

At some point, most cognitively disabled people are either left unsupervised in the community, or they end up in a group home, jail or some other form of institutionalization. Many die early from accident or neglect. And of those deaths, the contribution of cognitive disability to the premature mortality (for whatever reason) surely often goes overlooked.

In the case that caught my eye, the headline simply said, “Woman struck and killed by car.”

Would you – as a reader – have felt different if the headline had said, Intellectually disabled woman . . ., or, Autistic woman . . .?

I think the addition of either of those words would have implied a connection between cognitive disability and the death. They would give readers pause for thought, and perhaps make people think that some of the folks wandering the streets are more vulnerable to unwittingly step in front of a car than others.

But who would add the words? The sad truth is, many cognitively disabled people live lonely lives, and at the end, there may be no one to tell our story.

I believe we have a duty to protect the vulnerable members of our society. At the same time, I understand the feelings of those who say we should not have a duty to protect against stupidity. It’s a matter of context. People rightly object when our Coast Guard spends thousands to rescue drunken boaters. The rescue of children and cognitively disabled people is a very different story because they do not “know better,” and often cannot help themselves.

If you agree with me, give some thought to the question. Where do you think people with cognitive disabilities should live as adults? If you agree the community is best, how might we protect people while still respecting free choice and self determination? Can we, and should we even try? Does the protection we extend to children just run out at some point in adulthood?

These are difficult ethical questions and they don’t have easy answers.

John Elder Robison is an autistic adult and advocate for people with neurological differences. He's the author of Look Me in the Eye, Be Different, Raising Cubby, and Switched On. He serves on the Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee of the US Dept of Health and Human Services and many other autism-related boards. He's co-founder of the TCS Auto Program (A school for teens with developmental challenges) and he’s the Neurodiversity Scholar in Residence at the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia and a visiting professor of practice at Bay Path University in Longmeadow, Massachusetts.

The opinions expressed here are his own. There is no warranty expressed or implied. While reading this essay will give you food for thought, actually printing and eating it may make you sick.

(c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

Published on August 19, 2017 09:57

August 17, 2017

More Questions About the Reliquary

The later Anglican church at Jamestown (as reconstructed at the turn of the 20th century)

The later Anglican church at Jamestown (as reconstructed at the turn of the 20th century)It’s always hard to put ourselves in someone else’s shoes. It’s particularly tough when four hundred years and vast cultural differences separate us. Assumptions about how we think today, in a society informed by modern morality and a foundation of present-day science may be very far afield when set in the context of 1600 England or Virginia.

Today, when a new Catholic church is built, the bishop will oversee the installation of the relics in the altar. In most new churches the relics are installed in a niche made for that purpose and the installation is part of a ceremony. Things were very different in the Virginia colony in 1609.

There were no bishops in Virginia, nor were there any recognized Catholic clergy, though it’s possible Archer was a secret priest or deacon. Nothing at all is known of the person who set the reliquary atop his casket. All we can say for certain is that a traditional Catholic ceremony around the installation of relics would not have been possible in Virginia, in that day.

Catholics may have been tolerated in the Virginia settlement, but a Catholic church would not have been allowed. The only place of worship would have been the first Anglican church and its successors. Given that situation, did Catholics think of that as “their church” too?

If so, did one of them seize an opportunity to put the reliquary under the altar for that reason? We don’t know.

Imagine that Archer brought the reliquary and its contents to America intending to place them in a place of Catholic worship. But before he could do that, he died. We don’t know if he died suddenly or after a period of sickness. That means we have no idea if he had any opportunity to express a deathbed wish, and if so, if the reliquary was involved.

The reliquary was buried about 70 years after the Church of England broke with Rome. While they had adopted some elements of the Protestant Reformation, there was still much similarity between Anglican and Roman rites. Even today there is considerable similarity. How might that have affected Catholics who attended services?

Today we would expect a bishop or a priest to keep custody of a church’s relics. The situation was very different in 1609 Virginia. The colonists had come from an England where Catholicism had been outlawed and the many Catholic relics had found their way to safekeeping underground in Catholic homes.

Consequently we could expect relics to be in the custody of leading Catholics in English communities, recognizing that “leading Catholics” had a different meaning in that day because almost all Catholics were underground due to persecution.

If Archer’s parents were such people, it would not be any surprise that they may have entrusted him with relics with which to establish a Catholic outpost in Virginia. The fact that there was no bishop in Virginia may not have mattered, from the spiritual perspective of the settlers. Life itself was enough of a struggle that they were forced to be practical and do the best they could.

While there is no evidence (as yet) that Archer was a secret priest we do know he was an educated man and he studied the law. Today we would not be surprised to find a person of that description as a Catholic deacon, and that was likely true in 1600 as well. Deacons and Vestrymen tended to be community leaders, and education is often a part of that. So, while we may never know if he was a priest, he may well have been a deacon and for purposes of Catholicism in Virginia, that may have served the same purpose.

Finally, I have a question about the meaning of the reliquary in that time and place. I see its presence as a sign that Catholics were more tolerated at the colony’s founding than many scholars thought. Yet the fact that it remained buried and lost for 400 years speaks to the fact that mortality and turnover was so high that knowledge of the original church – let alone the reliquary beneath it – could not be maintained. Was Catholic tolerance – if real - indicative of broader toleration? And who was tolerant, and who tolerated?

I will be interested in thoughts from the Anglican and Catholic community on this and welcome any discussion.(c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

Published on August 17, 2017 08:09

May 14, 2017

Mastering the Obvious in Autism Science

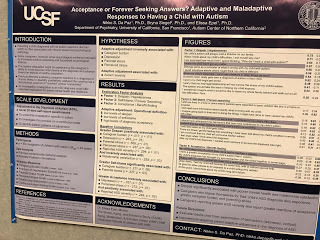

At this years IMFAR autism science conference I saw several presentations on seemingly obvious topics. For example, one study (DaPaz, University of California at San Francisco) assessed the responses of 89 parents to their children’s autism. The comments were grouped into three categories – despair/hopelessness; self-blame/searching; and acceptance/benefit finding. The researchers drew conclusions about the relationship between the types of comments and the parent’s states of mind. Not surprisingly the parents who reported mostly despair had poorer outcomes and acceptance was associated with lower stress. When I mentioned that study the most common reaction was, “Isn’t that obvious? Why are we spending money on a study like that?”

There were plenty of other similarly “obvious” studies. For example, one showed that parents who are educated about their children’s autism do better. Another found that kids do better when parents are taught basic autism therapy skills.

Here’s a really important point to consider when you ask why agencies fund studies like that: When it comes to arguing what health insurance should cover, decisions are driven by evidence. You may think a certain thing is obvious, but without clear evidence, you are unlikely to see any insurance company cover it. Even when we think the evidence is clear, doubt may remain and that can necessitate more studies. Occasionally, studies of the obvious reveal really surprising things, showing us that the obvious is sometimes badly misunderstood.

For example we have all hear that employment statistics for autistic people are dismal. “90% unemployed,” is a number that’s commonly bandied about. Personally I always doubted that and in fact an Autistica UK study that I saw on Friday night showed the number was closer to 60%. In that case far more people seem to be working that previously assumed.

There are obvious implications for public health policy in number like that.

There’s a third group of “obvious” studies that we need very much. Those are the studies that further validate initial research results. It’s great when a lab reports positive outcomes for a new intervention or therapy. But one great result is not enough to put that new there app on the menu all across the country. We need a plethora of studies – on disparate populations; done by different groups of researchers – to build a really solid base of evidence that something worked. That’s what it takes to win insurance approval for anything new, and even then, it takes years.

You can certainly decry this system as unfair and exclusionary. You might feel the insurers are just trying to escape what you see as a moral obligation. But of course they would answer that they have responsibilities to both their insured population and their share holders. The fact is, without evidence, we are nowhere with even the best new therapy.

Sometimes these “obvious” studies are conducted by young scientists who are just starting out. I encourage that. Other times they are conducted by better established scientists under the sponsorship of someone with a stake in the therapy under test. We have to be careful with work like that because conflicts of interest can destroy the credibility of even the best done research.

The next time you see a piece of work you think is obvious, rather than criticize it as wasteful, as if this will be enough to expand the coverage of autism services to be closer to what we really need. In far too much of the country, the only thing insurers cover is ABA. That is equivalent to saying the only thing we will cover to treat your depression is Trazodone. All those other depression mess and therapies – not enough evidence for them. How well do you think that would work? If you say, not well at all, that is the reality we face in deploying therapies for autism right now.

That said, we do sometimes have too many studies of certain topics. That is particularly true of well-studied paths that are not direct tests of new therapies. People sometimes ask how many eye tracking studies we need, or how many baby sibs studies? In my opinion, those questions relate to a larger question – the balance of research funding. Should we spend less on basic research (such as the examples I cite) and move some of that money to develop and prove out therapies we could use tomorrow? If my conversations in the community are a guide many who live with autism would say yes, though most would also want basic scientific research to continue.

Deciding how to spend our limited research dollars is difficult. But there’s less outright waste than many people imagine. There is good reason to “master the obvious.”

John Elder Robison is an autistic adult and advocate for people with neurological differences. He's the author of Look Me in the Eye, Be Different, Raising Cubby, and Switched On. He serves on the Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee of the US Dept of Health and Human Services and many other autism-related boards. He's co-founder of the TCS Auto Program (A school for teens with developmental challenges) and he’s the Neurodiversity Scholar in Residence at the College of William & Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia and a visiting professor of practice at Bay Path University in Longmeadow, Massachusetts.

The opinions expressed here are his own. There is no warranty expressed or implied. While reading this essay may give you food for thought, actually printing and eating it may make you sick.

(c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

Published on May 14, 2017 12:51

May 11, 2017

Getting involved guiding autism research

In the early days of autism research non-autistic doctors and scientists observed autistic people like me, asked questions, and then formulated their best ideas about what our problems were, and what research might be beneficial and interesting. Autistic people were patients and study subjects, but we had little say in the research designs.

Over the past few decades autistic people have come into their own, and an autistic culture has emerged. Autistic people began to assert themselves in research, taking stances on the ethics of some studies and the basic purpose of other work. The Internet empowered many people, and some began offering their thoughts on research and autism science.

I’ve written about my own autism science journey, and autistic people now ask how they can get involved. I’d like to offer some suggestions.

The first place for most of us is where we live. Are you part of a local autism support group? Do you know other autistic people? If you live in an area where no such groups exist I suggest you get something started. The first step in powerful advocacy is to have a community, and encourage it to grow.

Check with local colleges and universities, and see who’s doing autism research where you may be able to contribute. Many departments may be involved in research, and you often find the different departments don’t know what the others are doing. You can find autism researchers in such diverse departments as Communication Science Disorders, Speech Pathology, Occupational Therapy, Psychology, the medical school, Education, Nursing and even the business school.

Research in your area may be focused on very low-level biology, or more practical things like workplace safety. Given the available research – which is dependent on faculty interests, abilities, and funding – where might you make a contribution? My first suggestion is that you approach autism researchers, explain that you are an autistic person yourself, and ask how you may be of help. If my experience is a guide most researchers will welcome your help. In my own advocacy work I encourage our government funders to require autistic involvement in structuring new studies, and I encourage members of INSAR – the professional society for autism science – to do the same.

I'd like to be clear about something here . . . Autistic people have been connecting with researchers for years . . . In the context of volunteering to be research subjects. In the same way, autism parents have connected with researchers for years, to volunteer their children as subjects. This essay is not about that. In this essay I recognize that those researchers will benefit from guidance and advice from actual autistic people in structuring the studies they may later ask us to take part in as volunteers. I'm encouraging you to be one of those guides or advisors, at least at first. If you want to volunteer, fine, but let's make sure what we volunteer for is shaped to help us best.

If you are lucky enough to live in a city where an autism conference is hosted you’ll have a great opportunity to meet researchers from all over. For example, this years IMFAR conference is in San Francisco and there are a number of autistic people in attendance, making connections with researchers. This is the world’s largest autism science gathering, and it happens once a year, but there are smaller autism science conferences at universities all over, all the time.

Government agencies are also looking for autistic people who can help shape research. One central point for contact is the Office of Autism Research Coordination in the National Institutes of Health. Contact them and offer your services as a reviewer of research grant applications, and that could lead to service on any number of other committees within our public health services. If you are chosen to review proposed research you will be reimbursed for travel and paid a small stipend.

Opportunities may also exist for autistic people to work with private foundations who fund autism research. Some groups will be open to your thoughts; others will have their own agendas. The more you can open up funding groups to autistic input, the better.

Those are hands-on actions you can take to ensure autism science is usefully guided by autistic thinking. Are you ready to tackle them? In some cases all you need to provide useful input is the live experience of autism. That is enough to get started. The deeper you get the more you will find a knowledge of the research landscape useful. Medical science is complex, and so are all the other disciplines that offer promise for improved quality of life. No one person can master them all, but if you become expert in a particular area you may wish to focus your guidance and advice there. Others will prefer to remain generalists and use their lived experience alone.

Many self advocates talk about medical and social models of autism, and some suggest that we need to “switch” from medical to social perspectives. I believe there is a place for both. There are social scientists studying that very question, and they may benefit enormously from autistic insight. More than that, the medical issues that often accompany autism are real, and to turn away from a medical model of autism is to ignore that reality. You may not see a need for medical science to improve your quality of life, but others who suffer intestinal pain, epilepsy or anxiety may have a very different perspective.

Finally, I encourage you to speak out. By writing about your experiences you may inspire others. You will contribute to the building of community which is what gives our advocacy perspective. With community we become part of a tribe with all that entails. We have unique strengths and we share certain weaknesses. The better we join our voices, the louder and more effective we will be.

John Elder Robison is an autistic adult and advocate for people with neurological differences. He's the author of Look Me in the Eye, Be Different, Raising Cubby, and Switched On. He serves on the Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee of the US Dept of Health and Human Services and many other autism-related boards. He's co-founder of the TCS Auto Program (A school for teens with developmental challenges) and he’s the Neurodiversity Scholar in Residence at the College of William & Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia and a visiting professor of practice at Bay Path University in Longmeadow, Massachusetts.

The opinions expressed here are his own. There is no warranty expressed or implied. While reading this essay may give you food for thought, actually printing and eating it may make you sick.

(c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

Over the past few decades autistic people have come into their own, and an autistic culture has emerged. Autistic people began to assert themselves in research, taking stances on the ethics of some studies and the basic purpose of other work. The Internet empowered many people, and some began offering their thoughts on research and autism science.

I’ve written about my own autism science journey, and autistic people now ask how they can get involved. I’d like to offer some suggestions.

The first place for most of us is where we live. Are you part of a local autism support group? Do you know other autistic people? If you live in an area where no such groups exist I suggest you get something started. The first step in powerful advocacy is to have a community, and encourage it to grow.

Check with local colleges and universities, and see who’s doing autism research where you may be able to contribute. Many departments may be involved in research, and you often find the different departments don’t know what the others are doing. You can find autism researchers in such diverse departments as Communication Science Disorders, Speech Pathology, Occupational Therapy, Psychology, the medical school, Education, Nursing and even the business school.

Research in your area may be focused on very low-level biology, or more practical things like workplace safety. Given the available research – which is dependent on faculty interests, abilities, and funding – where might you make a contribution? My first suggestion is that you approach autism researchers, explain that you are an autistic person yourself, and ask how you may be of help. If my experience is a guide most researchers will welcome your help. In my own advocacy work I encourage our government funders to require autistic involvement in structuring new studies, and I encourage members of INSAR – the professional society for autism science – to do the same.

I'd like to be clear about something here . . . Autistic people have been connecting with researchers for years . . . In the context of volunteering to be research subjects. In the same way, autism parents have connected with researchers for years, to volunteer their children as subjects. This essay is not about that. In this essay I recognize that those researchers will benefit from guidance and advice from actual autistic people in structuring the studies they may later ask us to take part in as volunteers. I'm encouraging you to be one of those guides or advisors, at least at first. If you want to volunteer, fine, but let's make sure what we volunteer for is shaped to help us best.

If you are lucky enough to live in a city where an autism conference is hosted you’ll have a great opportunity to meet researchers from all over. For example, this years IMFAR conference is in San Francisco and there are a number of autistic people in attendance, making connections with researchers. This is the world’s largest autism science gathering, and it happens once a year, but there are smaller autism science conferences at universities all over, all the time.

Government agencies are also looking for autistic people who can help shape research. One central point for contact is the Office of Autism Research Coordination in the National Institutes of Health. Contact them and offer your services as a reviewer of research grant applications, and that could lead to service on any number of other committees within our public health services. If you are chosen to review proposed research you will be reimbursed for travel and paid a small stipend.

Opportunities may also exist for autistic people to work with private foundations who fund autism research. Some groups will be open to your thoughts; others will have their own agendas. The more you can open up funding groups to autistic input, the better.

Those are hands-on actions you can take to ensure autism science is usefully guided by autistic thinking. Are you ready to tackle them? In some cases all you need to provide useful input is the live experience of autism. That is enough to get started. The deeper you get the more you will find a knowledge of the research landscape useful. Medical science is complex, and so are all the other disciplines that offer promise for improved quality of life. No one person can master them all, but if you become expert in a particular area you may wish to focus your guidance and advice there. Others will prefer to remain generalists and use their lived experience alone.

Many self advocates talk about medical and social models of autism, and some suggest that we need to “switch” from medical to social perspectives. I believe there is a place for both. There are social scientists studying that very question, and they may benefit enormously from autistic insight. More than that, the medical issues that often accompany autism are real, and to turn away from a medical model of autism is to ignore that reality. You may not see a need for medical science to improve your quality of life, but others who suffer intestinal pain, epilepsy or anxiety may have a very different perspective.

Finally, I encourage you to speak out. By writing about your experiences you may inspire others. You will contribute to the building of community which is what gives our advocacy perspective. With community we become part of a tribe with all that entails. We have unique strengths and we share certain weaknesses. The better we join our voices, the louder and more effective we will be.

John Elder Robison is an autistic adult and advocate for people with neurological differences. He's the author of Look Me in the Eye, Be Different, Raising Cubby, and Switched On. He serves on the Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee of the US Dept of Health and Human Services and many other autism-related boards. He's co-founder of the TCS Auto Program (A school for teens with developmental challenges) and he’s the Neurodiversity Scholar in Residence at the College of William & Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia and a visiting professor of practice at Bay Path University in Longmeadow, Massachusetts.

The opinions expressed here are his own. There is no warranty expressed or implied. While reading this essay may give you food for thought, actually printing and eating it may make you sick.

(c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

Published on May 11, 2017 16:39

February 22, 2017

The Role of Autism in Polynesian Navigation

The past 40 years has seen a remarkable renaissance of Polynesian cultural awareness, with rediscovery and celebration of ancient skills and practices. Polynesians are taking pride in their heritage - particularly the seafaring skills that made settlement of the Pacific islands possible. The navigation techniques developed and practiced by these island people were distinctly different from those developed by Europeans. They were originally characterized as primitive by western anthropologists, but we now realize they were in many ways more sophisticated than methods developed in the west.

Polynesian navigators are called wayfinders, and their craft is called wayfinding. Western researchers have studied their techniques over the past 50 years. Their efficacy is firmly established; what’s missing is a study of the intellectual requirements of wayfinding. This is significant because European navigators rely on measurements with instruments and pen and paper calculation. Thanks to tools and method, most people can learn to do it. Wayfinding does not use tools or pen and paper; it is all “in the head,” and for that reason it is more challenging. Wayfinders are consequently much less common. This essay considers the cognitive issues and explores a possible relationship between those voyagers and autism.

Autism is a neurological difference that was first recognized in people who showed profound disability but at the same time, flashes of intellectual exceptionality. Autism has been recognized since the 1930s but it has undergone a renaissance of its own in terms of understanding in the past 50 years. At first, autism was only diagnosed in people with very severe disability. Then in the 1990s the diagnostic criteria were broadened. The phrase “communication disability” that once meant “nonverbal person” now refers to anything from that to inability to understand facial expressions in an otherwise articulate person. With that change, far more autistic people were recognized, especially kids. At the same time, the perception of autism changed. Where it was seen as a crushing disability, autism is now viewed on a continuum. There are extremely disabled autistic people, but the autism spectrum also encompasses some gifted individuals.

The mental gymnastics performed by wayfinders appear to match capabilities bright autistic people are known for, and excel at. At the same time, the wayfinding job and its social context seems to be one where autistic disabilities would be minimized. The closer a knowledgeable (with respect to autism) person looks, the better the fit appears to be.

Anthropologists who are accustomed to seeing autism through the lens of disability might initially doubt the connection because wayfinders have traditionally been important figures in island cultures. They are not socially isolated as the disability model might predict. Yet that does not rule out their being autistic. There are many autistic leaders in western society.

Profoundly disabled autistics make less than one-half percent of the human population. The number of people who have some autistic traits without total disability is much larger. The autism spectrum – the term for all autistic people – includes 1.5% to 2% of humanity. Adding in people who have some autistic traits but not enough for formal diagnosis yields what researchers call the “broad autism phenotype,” which may total 5% of the population. This essay explores some of their unique attributes and why autistics might have been drawn to wayfinding.

We begin by looking at the wayfinding task, and asking a question: what kind of person sets sail in a vessel, with no navigational instruments, into the vastness of the South Pacific, and travels 2,500 miles on winds and currents to reach a destination island that is just 50 miles wide in an otherwise open sea? Wayfinders have extraordinary sensory and calculating abilities – two areas of common strength in bright autistic people.

We understand that different types of people are best at certain jobs. Building houses requires manual skills - dexterity, and brawn. Assembling electronic devices calls for precise coordination. A few jobs – like code breaking or software engineering – require special cognitive skills. Some jobs with unusual cognitive demands may be particularly suited to autistic people. A western example of that might be a computer science or math department at a university, where people joke that “half the faculty are on the autism spectrum,” with more than a grain of truth to the statement. Hans Asperger – one of the doctors who originally characterized autism – noted the connection between autism and certain technical and creative pursuits in the 1930s.

When thinking of a cognitively demanding job you might imagine engineering or science. Those are good examples, but they are fairly new to humanity in the form we see today. Wayfinding is an example of a job that was cognitively demanding in a less technological society, such as existed in the South Pacific.

The job is not physically strenuous, though it does require stamina, as the navigator must be awake and alert for most of a voyage. He/she must remember a vast body of data about the movements of stars, sun and moon. The wayfinder must sense direction and currents from the feel of swells acting upon his vessel, and be attuned to clues in the environment, like birds showing the direction to land. Finally the wayfinder must integrate observations with memory, and extrapolate from what’s known of places previously visited to what is anticipated for the destination. An in-depth description of wayfinding can be found in David Lewis’s 1972 book, We the Navigators.

The complexity of wayfinding is easily underestimated, particularly compared to western navigation. Anyone observing the navigator aboard a modern merchant ship sees a person surrounded by high-tech gear – satellite navigation, depth finders, radar and more. The array of equipment fairly screams out “complex task!” A Pacific wayfinder, in comparison, has nothing in his/her hands, and no tools or aids in sight. They simply stands on the ship’s deck and observe, occasionally giving directions to the helmsman. There is no observable evidence of the calculations taking place in the mind.

Until recently, non-sailing anthropologists doubted early wayfinders had the ability to deliberately sail open canoes thousands of miles between islands like Tahiti, New Zealand, and Hawaii. After all, European navigators didn’t learn to calculate longitude (position on an east-west axis) until the 18thcentury, and they thought that was essential to precise navigation, especially when it came to finding islands.

Prior to developing the ability to calculate longitude European sailors were left with latitude (north-south orientation) as their only measure of position. Early navigators had little understanding of ocean currents or other factors that might affect their course. Luckily when Europeans ventured west they had two huge continents as targets. No matter what direction he sailed, an early European navigator would fetch up somewhere on the shores of North or South America.

The Pacific Ocean presented a rather different problem. There, tiny islands were scattered over millions of square miles of deep trackless ocean. A Pacific navigator needs to hold a course much more precisely to avoid missing his targets. That was a problem European navigators of the last millennium did not solve until the invention of the chronometer, so anthropologists assumed the Polynesians – who did not have chronometers – must never have solved it for themselves.

In a classic display of ethnocentricity some anthropologists concluded Polynesian sailors must have reached distant destinations only by lucky accident. Their arguments were buttressed with stories of shipwrecked European navigators. However studies showed winds and currents make it impossible for a boat to drift from Tahiti to Hawaii yet legends describe voyaging between the two islands. Polynesians insisted the settlement of their islands was purposeful, not accidental.

Westerners also doubted the ability of craft described as “canoes” to cross vast distances of open sea. That notion was largely founded on misunderstanding – a Polynesian voyaging canoe has nothing in common with the car-top craft of the same name that Americans know and love. In fact, Polynesian voyaging canoes have much more in common with the sophisticated twin-hull sailing yachts that routinely cross the oceans today, and in many ways they are even more rugged and seaworthy.

A group of Hawaiians set out to prove the hypothesis that their boatbuilding and navigation skills were sufficient to have settled the vast Pacific. In 1975 they launched the first Hawaiian voyaging canoe to set sail in 600 years – the Hōkūle‘a. Built in the pattern of the voyaging canoes of the last millennium, Hōkūle‘a proved to be a remarkably capable craft. When navigated by traditional methods of star and current observation, Hōkūle‘a crossed 2,500 miles of open sea between Hawaii and Tahiti to make landfall with as much accuracy as any western craft in the pre-GPS era. The navigator for that trip was Mau Piailug, a wayfinder from the island of Satawal. His apprentice was Hawaiian Nainoa Thompson, who continues as a wayfinder today and leads the Polynesian Voyaging Society. Will Kyselka’s 1987 book An Ocean in Mind describes these voyages and the individuals who made them.

Piailug, Thompson, and the wayfinders they trained show that accurate navigation is possible without the use of any modern instruments. The mind and hand alone are sufficiently powerful tools, given correct training and suitable cognitive powers. The culture of Polynesian navigation that has been passed on from master to apprentice is once again enjoying resurgence thanks to groups like the Polynesian Voyaging Society.

When we consider that traditional navigation is a skill Polynesian cultures have guarded and preserved for over 2,000 years we might ask if there is anything special about the individuals chosen to become navigators. I began to wonder about that when I learned of the cognitive complexity of Polynesian navigation, particularly the idea it is “all in the mind.” The difference between that and European-style navigation is striking given that the latter relies on specialized tools and pen and paper calculation, where the Polynesian system uses no tools at all yet it produces an equally functional result.

The early Polynesian people had more of a seafaring culture than what is retained today. Young navigators apprenticed themselves to master navigators and learned the stars, swells, and currents through observation on long ocean voyages. Wayfinder accounts of the last century suggest that apprenticeship started as early as five years of age. Navigators often ran in families, with older men training promising sons or nephews. That process has been largely lost with the disappearance of traditional long distance Polynesian sailing craft, though there is a recent move to resurrect it.

Modern-day Polynesian navigators train for voyages by looking at the stars and “learning the sky.” They make mental maps of the sky and gain understanding of the relationship between time, one’s position on earth, and the stars. This gives them a deeper understanding of the relationship of the sky to one’s position on earth than that held by European sailors of the last 1,000 years and it is key to their success. In addition to the stars wayfinders learn to read ocean swells and currents and interpret countless other clues that point the way to land over the horizon.

Man’s ability to acquire and use this knowledge is a remarkable display of human cognition. When westerners learn navigation, they do so within a complex framework of map reading and advanced mathematics to calculate latitude and longitude. For westerners, navigation also relies on precise timekeeping – hence the importance of the chronometer in our culture. Pacific navigators do not use those tools. Their navigation is more elemental. Pacific islanders find their position accurately (with respect to their home and destination islands) without knowledge of western math or celestial mechanics. They grasp and manipulate the complex concepts of position fixing instinctively.

A westerner can learn basic instrument navigation in a few weeks. However most don’t even do that – they rely on navigation devices to show the way with no training at all. The downside of that is, they are totally lost if the tools fail. Polynesian wayfinders spend a lifetime training their minds but they are then free of dependence on tools or technology. The more we learn about wayfinding the more respect we can have for the few people who master its challenges. To put their achievements in western terms, master wayfinders are in many respects Olympians of the mind.

After studying all the requirements, it appears that certain autistic people – including those of the broader autism phenotype – are uniquely suited to the cognitive demands of wayfinding. Very few non-autistic people can gaze at the sky with enough intensity and focus to burn an accurate map into their heads, particularly as the map moves when the navigator changes position, time or season. Yet anyone who works with autistic people would look at that challenge and see an autistic strength.

That’s not the only hint of autism in wayfinding. In the accounts of Lewis and others, wayfinders exhibit what may be other traits of autism, such as lack of social awareness. Autistic people tend to have some degree of social disability, either from challenges with language or blindness to other social cues. Polynesian sailing vessels had small, tightly knit crews, where such disabilities would be minimized by familiarity. A Polynesian wayfinder would be less disabled by autism in his job than he might be in most traditional western workplaces.

What’s most important to the wayfinding role are some of the gifts certain autistic people have. These gifts are part and parcel of autism because they have the same neurological roots as the disability aspects; the two go hand in hand. Autism is not widely recognized among present-day native Hawaiians and Polynesians. Yet studies suggest it should be just as common there as elsewhere in the world. In reading accounts of present-day Polynesian navigators, I see many signs of the broad autism phenotype.

Some of the autistic traits that can be seen in descriptions of Polynesian navigators are:· Social isolation – wayfinders are often portrayed in text as loners or strongly independent. Being independent is not itself diagnostic of autism, but independence and aloneness are common traits for autistic people. · Anecdotes of wayfinders often present them as socially inept or unaware. Gaffes were attributed to culture (i.e.; being “from Satawal” or another distant island) but they may just as well have been due to autistic social disability;· Accounts of wayfinders describe multiple generations of navigators, who were trained from early childhood, and who then trained the next generation. Autism has a strong inherited component, so the cognitive abilities needed for wayfinding would likely be passed on in a family line.· In his descriptions of wayfinders, Lewis described men who were very tied to routines. He described several instances of distress when routines were broken. Restricted interests, love of routine, and distress when routine is broken are diagnostic traits of autism.· Most descriptions of wayfinders describe them as very focused on their craft. Extreme focus and extraordinary powers of concentration are common in autistic people.· Video of navigators like Mau Piailug (See maupiailugsociety videos on youtube) shows scenes an autism therapist would describe as “very autistic.” Behavioral examples include limited facial expressions; animation of the bottom of the face but not the top; gaze at the floor rather than other people; and cadence and pattern of speech. While no one would propose to render an autism diagnosis from a short series of videos, it is more possible to recognize the broader autism phenotype.· Wayfinders need an ability to sense subtle clues in the environment, like the way ocean swells feel under the boat. Autistic people are prone to extraordinary sensory sensitivities, and they are typically good at recognizing patterns or deviations from them (like the way swells feel.) In his accounts of voyaging with Piailug, Thompson describes how the older man could sense and feel things invisible to him. That could well be an example of superior sensitivity that might be disabling in some contexts on shore but was a great gift at sea.· Wayfinders rely on knowledge and logic as opposed to emotion. Lewis makes that point when quoting wayfinders, who assure him their craft is based on knowledge and not superstition or belief. A preference for logic over emotion is suggestive of autism.· A strong ability to systematize is essential to wayfinding. Examples are judging position from the star map overhead and the classification and interpretation of ocean swells and other evidence relevant to position and course. Autistic people tend to be strong systematizers;· Given the number of stars one can see in the sky, a person’s ability to memorize the position data that is revealed by patterns of stars aligning or setting must be extraordinary. Thompson says he uses several hundred stars for navigation. Such exceptionality is extremely rare in the general population but somewhat common among autistics.· Exceptional calendar calculating skills are very useful for manipulating and evaluating celestial maps in the head. Autistics are the only group of people known to commonly possess calendar calculating skills. Psychiatrist Darold Treffert has suggested more than 6% of autistics have extraordinary calendar skills.· Exceptional visual memory is necessary to acquire the star maps needed for navigation, and that too is common in autistics but rare in the general population. · Finally, a wayfinder needs the ability to transform complex visual images in the mind (i.e. sophisticated thinking in pictures.)

While none of these skills are individually diagnostic of autism they are – when taken together – strongly suggestive that a person fitting this wayfinder description is part of the broader phenotype, and may be autistic. Of course, not every autistic person is a potential wayfinder. The required ability set is probably very rare in the population but to the extent it exists at all, it will be found among members of the autism community.

Some researchers refer to autistic people as “nature’s engineers” because they can learn complex computational skills on their own, without the need for schools or modern teaching practices. Exceptional focus and concentration are autistic traits, and in this case they may have helped Polynesian autistics to acquire the skills to design and then navigate their vessels, thereby facilitating the original settlement of the Pacific islands.

The question of autism in Polynesian navigators actually raises another question – Does a western diagnostic label that we associate with disability have any relevance when applied to a wayfinder in the South Pacific? That question struck me as I watched old video of Mau Piailug, who died in 2010. When I watched him in the videos I saw many signs of the broad autism phenotype in his speech, his expressions, and his behavior. Yet he was a respected leader in his community; there is no evidence that anyone perceived him as disabled in his lifetime. To apply a disability diagnosis now from afar would strike many people as disrespectful and wrong.

A significant number of Polynesian wayfinders may have been autistic throughout the years. We have no way to know. The fact is, autism per se had nothing to do with their finding their profession. They were chosen for their ancestry or their behaviors – both of which might suggest “autistic” to us but suggested “navigator material” to the Polynesians. It’s worth pondering which worldview is more personally empowering.

On a pacific island world, an autism diagnosis has no meaning. The place it has meaning is in our hi-tech western world. It’s here that autistics are disabled, and seeking explanation and insight. For an autistic teen in a modern-day Hawaiian school, the idea that a great wayfinder like Piailug may be “autistic like me” is very empowering. What it shows is that a class of people who are mostly disabled and less capable in our society can be exceptional in other circumstances and cultures.

It’s a fascinating idea.

John Elder RobisonNeurodiversity Scholar, The College of William & MaryWilliamsburg, VA

Visiting Professor of Practice, EducationBay Path UniversityLongmeadow, MA

John Elder Robison is an autistic adult who studies the role of autistic people in society. He navigates a small boat on inland rivers near his home in Western Massachusetts. He is the NY Times bestselling author of four books on life with autism: Look Me in the Eye, Be Different, Raising Cubby, and Switched On.

(c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

Polynesian navigators are called wayfinders, and their craft is called wayfinding. Western researchers have studied their techniques over the past 50 years. Their efficacy is firmly established; what’s missing is a study of the intellectual requirements of wayfinding. This is significant because European navigators rely on measurements with instruments and pen and paper calculation. Thanks to tools and method, most people can learn to do it. Wayfinding does not use tools or pen and paper; it is all “in the head,” and for that reason it is more challenging. Wayfinders are consequently much less common. This essay considers the cognitive issues and explores a possible relationship between those voyagers and autism.

Autism is a neurological difference that was first recognized in people who showed profound disability but at the same time, flashes of intellectual exceptionality. Autism has been recognized since the 1930s but it has undergone a renaissance of its own in terms of understanding in the past 50 years. At first, autism was only diagnosed in people with very severe disability. Then in the 1990s the diagnostic criteria were broadened. The phrase “communication disability” that once meant “nonverbal person” now refers to anything from that to inability to understand facial expressions in an otherwise articulate person. With that change, far more autistic people were recognized, especially kids. At the same time, the perception of autism changed. Where it was seen as a crushing disability, autism is now viewed on a continuum. There are extremely disabled autistic people, but the autism spectrum also encompasses some gifted individuals.

The mental gymnastics performed by wayfinders appear to match capabilities bright autistic people are known for, and excel at. At the same time, the wayfinding job and its social context seems to be one where autistic disabilities would be minimized. The closer a knowledgeable (with respect to autism) person looks, the better the fit appears to be.

Anthropologists who are accustomed to seeing autism through the lens of disability might initially doubt the connection because wayfinders have traditionally been important figures in island cultures. They are not socially isolated as the disability model might predict. Yet that does not rule out their being autistic. There are many autistic leaders in western society.

Profoundly disabled autistics make less than one-half percent of the human population. The number of people who have some autistic traits without total disability is much larger. The autism spectrum – the term for all autistic people – includes 1.5% to 2% of humanity. Adding in people who have some autistic traits but not enough for formal diagnosis yields what researchers call the “broad autism phenotype,” which may total 5% of the population. This essay explores some of their unique attributes and why autistics might have been drawn to wayfinding.

We begin by looking at the wayfinding task, and asking a question: what kind of person sets sail in a vessel, with no navigational instruments, into the vastness of the South Pacific, and travels 2,500 miles on winds and currents to reach a destination island that is just 50 miles wide in an otherwise open sea? Wayfinders have extraordinary sensory and calculating abilities – two areas of common strength in bright autistic people.

We understand that different types of people are best at certain jobs. Building houses requires manual skills - dexterity, and brawn. Assembling electronic devices calls for precise coordination. A few jobs – like code breaking or software engineering – require special cognitive skills. Some jobs with unusual cognitive demands may be particularly suited to autistic people. A western example of that might be a computer science or math department at a university, where people joke that “half the faculty are on the autism spectrum,” with more than a grain of truth to the statement. Hans Asperger – one of the doctors who originally characterized autism – noted the connection between autism and certain technical and creative pursuits in the 1930s.

When thinking of a cognitively demanding job you might imagine engineering or science. Those are good examples, but they are fairly new to humanity in the form we see today. Wayfinding is an example of a job that was cognitively demanding in a less technological society, such as existed in the South Pacific.

The job is not physically strenuous, though it does require stamina, as the navigator must be awake and alert for most of a voyage. He/she must remember a vast body of data about the movements of stars, sun and moon. The wayfinder must sense direction and currents from the feel of swells acting upon his vessel, and be attuned to clues in the environment, like birds showing the direction to land. Finally the wayfinder must integrate observations with memory, and extrapolate from what’s known of places previously visited to what is anticipated for the destination. An in-depth description of wayfinding can be found in David Lewis’s 1972 book, We the Navigators.

The complexity of wayfinding is easily underestimated, particularly compared to western navigation. Anyone observing the navigator aboard a modern merchant ship sees a person surrounded by high-tech gear – satellite navigation, depth finders, radar and more. The array of equipment fairly screams out “complex task!” A Pacific wayfinder, in comparison, has nothing in his/her hands, and no tools or aids in sight. They simply stands on the ship’s deck and observe, occasionally giving directions to the helmsman. There is no observable evidence of the calculations taking place in the mind.

Until recently, non-sailing anthropologists doubted early wayfinders had the ability to deliberately sail open canoes thousands of miles between islands like Tahiti, New Zealand, and Hawaii. After all, European navigators didn’t learn to calculate longitude (position on an east-west axis) until the 18thcentury, and they thought that was essential to precise navigation, especially when it came to finding islands.

Prior to developing the ability to calculate longitude European sailors were left with latitude (north-south orientation) as their only measure of position. Early navigators had little understanding of ocean currents or other factors that might affect their course. Luckily when Europeans ventured west they had two huge continents as targets. No matter what direction he sailed, an early European navigator would fetch up somewhere on the shores of North or South America.

The Pacific Ocean presented a rather different problem. There, tiny islands were scattered over millions of square miles of deep trackless ocean. A Pacific navigator needs to hold a course much more precisely to avoid missing his targets. That was a problem European navigators of the last millennium did not solve until the invention of the chronometer, so anthropologists assumed the Polynesians – who did not have chronometers – must never have solved it for themselves.

In a classic display of ethnocentricity some anthropologists concluded Polynesian sailors must have reached distant destinations only by lucky accident. Their arguments were buttressed with stories of shipwrecked European navigators. However studies showed winds and currents make it impossible for a boat to drift from Tahiti to Hawaii yet legends describe voyaging between the two islands. Polynesians insisted the settlement of their islands was purposeful, not accidental.

Westerners also doubted the ability of craft described as “canoes” to cross vast distances of open sea. That notion was largely founded on misunderstanding – a Polynesian voyaging canoe has nothing in common with the car-top craft of the same name that Americans know and love. In fact, Polynesian voyaging canoes have much more in common with the sophisticated twin-hull sailing yachts that routinely cross the oceans today, and in many ways they are even more rugged and seaworthy.

A group of Hawaiians set out to prove the hypothesis that their boatbuilding and navigation skills were sufficient to have settled the vast Pacific. In 1975 they launched the first Hawaiian voyaging canoe to set sail in 600 years – the Hōkūle‘a. Built in the pattern of the voyaging canoes of the last millennium, Hōkūle‘a proved to be a remarkably capable craft. When navigated by traditional methods of star and current observation, Hōkūle‘a crossed 2,500 miles of open sea between Hawaii and Tahiti to make landfall with as much accuracy as any western craft in the pre-GPS era. The navigator for that trip was Mau Piailug, a wayfinder from the island of Satawal. His apprentice was Hawaiian Nainoa Thompson, who continues as a wayfinder today and leads the Polynesian Voyaging Society. Will Kyselka’s 1987 book An Ocean in Mind describes these voyages and the individuals who made them.

Piailug, Thompson, and the wayfinders they trained show that accurate navigation is possible without the use of any modern instruments. The mind and hand alone are sufficiently powerful tools, given correct training and suitable cognitive powers. The culture of Polynesian navigation that has been passed on from master to apprentice is once again enjoying resurgence thanks to groups like the Polynesian Voyaging Society.