John Elder Robison's Blog, page 3

March 26, 2018

W&M Neurodiversity - class on brain stimulation

Neurodiversity Class – Monday March 26Brain Stimulation

In our class on brain stimulation I’d like to present some emerging therapies that offer the promise of changing brains in elemental ways. Changing brains means changing personality, intelligence. Such an action has the potential for altering one’s very hopes and dreams, and that carries significant ethical implications for anyone who advocates for the therapy, whether as a parent, guardian, or professional. It also has implications for any adult who considers partaking, or any child or person under guardianship who faces having it “done to them.”

Bertrand the Brain Dog, waiting outside the hospital.

Bertrand the Brain Dog, waiting outside the hospital.

Dogs like Bertrand made an unheralded but substantial

contribution to neurological research over the past 150 years.

The development of these therapies heralds a new era for humanity. Cognitive attributes that were thought to be immutable turn out to be flexible. Ideas like "That's evolution, nothing you can do," or, “God made him that way” will be supplanted by the possibility of human-driven change.

As new cognitive therapies and treatments emerge they will present great opportunity to help people. Some of those people will have profound and long unmet needs. Others will have wants. Some may not want treatment at all, yet have it thrust upon them. With tools as powerful as these ethical questions will surely arise.

Let’s discuss those issues with the help of several scenarios.

Scenario #1:

The brain is an electrical organ. Billions of neurons are connected with almost uncountable numbers of microscopic threads – axons and dendrites – carrying signals from one neuron to another. The network builds itself and then fine tunes itself throughout our lifespan.

In addition to the natural process of development we can energize and change the network. Chemicals can travel through the bloodstream into the brain where they change the properties of that network. That’s how recreational drugs and psychiatric medication work.

Electrical stimulation can enter the brain through electrodes applied to the scalp or through wires implanted in the brain. This is called (transcranial) direct brain stimulation, or TDCS

Circuits in the forebrain may be energized and stimulation with infrared laser energy, where photos of laser light penetrate the skull and are absorbed by molecules in the neurons, stimulation them to action. That is Transcranial Laser Stimulation.

The circuitry in the outer layers of the brain may also be energized or suppressed through the process of electromagnetic induction. That is Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation, or TMS

The therapies above are all real. Psychiatric meds and recreational drugs are widely used. TMS and TDCS are being studied for some therapies and deployed for others. Laser therapy is still in the research stage but shows promise.

Now consider this scenario:

A therapy is used to relieve anxiety and depression and it works well for 30% of patients. 10% report slight benefit. 5% feel worse. 0.02% commit suicide and can no longer be evaluated. The causal connection between the therapy and suicide is disputed because some percentage of the population is destined to commit suicide anyway.

13 of every 100,000 people in the general population kill themselves every year.20 of every 100,000 people in the treatment kill themselves every year.30,000 of every 100,000 report a benefit

You are a regulator. What do you do? Is the risk real, and should a therapy with that risk be allowed?You are a therapist. Do you take the chance and recommend therapy, or take the safe route and talk instead?You are a patient. Do you do it?

Scenario #2:

A ten-year-old autistic child has a strong logical mind, but very little sense of the emotions in the children around him. He has no friends and is very lonely. At the same time, he seems to be quite the prodigy on the computer.

He says he’s going to be a computer scientist when he grows up. He says the thing he wants most of all is to have friends who will play with him at his birthday party.

You have been told about a brain therapy that will rebalance his brain, allowing him to see emotion in other kids. The therapy has worked for other kids, and he is likely to gain the ability to make friends, but he may lose interest in logic and computers. Nothing like this existed when you were a child; the very idea was the subject of fantasy movies. But it’s real now and some applications are even covered by health insurance.

You are his parent. Do you give him the therapy? What do you tell him?You're ten years old. What do you want most in life? Are friends more important than intellectual superpower? Is intellectual superpower important to you? Think back a few years . . .

Scenario #3:

Thanks to the convergence of brain stimulation and brain imaging we know that your brain and mine react the same when we see a red ball. We know that red, green, or blue trigger specific patterns in our brains, and when we use eye tracking to know where we are gazing and brain imaging to see the reaction, a computer can now tell what color we are looking at.

Shapes and objects form distinct and recognizable patterns too. Supercomputers can accurately resolve thousands of common objects including cars, airplanes, dogs, cats, guns and pencils. The computers can associate emotion too, separating any house from home, and any female from mom.

Science has delivered us the ultimate lie detector. The mind probe of science fiction is real.

You have a suspected terrorist in your custody. He is placed in the scanner and shown images associated with a recent bombing. You have identified the house where the bomb was made. The suspect’s brain lights up as home. You show a picture of the carnage of the bomb. The suspect’s brain reflects a pattern of pride.

You are a government leader. What do you do with the suspect? Is a trial needed; would it serve a purpose?You are a scientist in the program. Should your newfound power be kept secret?You call yourself a freedom fighter. The enemy calls you a terrorist. How do you combat this machine?

This technology is [very likely] in development now (it’s classified.) The practical difficulty of getting uncooperative subjects into the scanner and getting them to view materials may delay deployment somewhat.

(c) 2018 John Elder Robison

John Elder Robison is an autistic adult and advocate for people with neurological differences. He's the author of Look Me in the Eye, Be Different, Raising Cubby, and Switched On. He serves on the Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee of the US Dept of Health and Human Services. He's co-founder of the TCS Auto Program (A school for teens with developmental challenges) and he’s the Neurodiversity Scholar at the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia. He's also a visiting professor of practice at Bay Path University in Longmeadow, Massachusetts and advisor to the Neurodiversity Institute at Landmark College in Putney, Vermont.

The opinions expressed here are his own. There is no warranty expressed or implied. While reading this essay will give you food for thought, actually printing and eating it may make you sick.

(c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

In our class on brain stimulation I’d like to present some emerging therapies that offer the promise of changing brains in elemental ways. Changing brains means changing personality, intelligence. Such an action has the potential for altering one’s very hopes and dreams, and that carries significant ethical implications for anyone who advocates for the therapy, whether as a parent, guardian, or professional. It also has implications for any adult who considers partaking, or any child or person under guardianship who faces having it “done to them.”

Bertrand the Brain Dog, waiting outside the hospital.

Bertrand the Brain Dog, waiting outside the hospital. Dogs like Bertrand made an unheralded but substantial

contribution to neurological research over the past 150 years.

The development of these therapies heralds a new era for humanity. Cognitive attributes that were thought to be immutable turn out to be flexible. Ideas like "That's evolution, nothing you can do," or, “God made him that way” will be supplanted by the possibility of human-driven change.

As new cognitive therapies and treatments emerge they will present great opportunity to help people. Some of those people will have profound and long unmet needs. Others will have wants. Some may not want treatment at all, yet have it thrust upon them. With tools as powerful as these ethical questions will surely arise.

Let’s discuss those issues with the help of several scenarios.

Scenario #1:

The brain is an electrical organ. Billions of neurons are connected with almost uncountable numbers of microscopic threads – axons and dendrites – carrying signals from one neuron to another. The network builds itself and then fine tunes itself throughout our lifespan.

In addition to the natural process of development we can energize and change the network. Chemicals can travel through the bloodstream into the brain where they change the properties of that network. That’s how recreational drugs and psychiatric medication work.

Electrical stimulation can enter the brain through electrodes applied to the scalp or through wires implanted in the brain. This is called (transcranial) direct brain stimulation, or TDCS

Circuits in the forebrain may be energized and stimulation with infrared laser energy, where photos of laser light penetrate the skull and are absorbed by molecules in the neurons, stimulation them to action. That is Transcranial Laser Stimulation.

The circuitry in the outer layers of the brain may also be energized or suppressed through the process of electromagnetic induction. That is Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation, or TMS

The therapies above are all real. Psychiatric meds and recreational drugs are widely used. TMS and TDCS are being studied for some therapies and deployed for others. Laser therapy is still in the research stage but shows promise.

Now consider this scenario:

A therapy is used to relieve anxiety and depression and it works well for 30% of patients. 10% report slight benefit. 5% feel worse. 0.02% commit suicide and can no longer be evaluated. The causal connection between the therapy and suicide is disputed because some percentage of the population is destined to commit suicide anyway.

13 of every 100,000 people in the general population kill themselves every year.20 of every 100,000 people in the treatment kill themselves every year.30,000 of every 100,000 report a benefit

You are a regulator. What do you do? Is the risk real, and should a therapy with that risk be allowed?You are a therapist. Do you take the chance and recommend therapy, or take the safe route and talk instead?You are a patient. Do you do it?

Scenario #2:

A ten-year-old autistic child has a strong logical mind, but very little sense of the emotions in the children around him. He has no friends and is very lonely. At the same time, he seems to be quite the prodigy on the computer.

He says he’s going to be a computer scientist when he grows up. He says the thing he wants most of all is to have friends who will play with him at his birthday party.

You have been told about a brain therapy that will rebalance his brain, allowing him to see emotion in other kids. The therapy has worked for other kids, and he is likely to gain the ability to make friends, but he may lose interest in logic and computers. Nothing like this existed when you were a child; the very idea was the subject of fantasy movies. But it’s real now and some applications are even covered by health insurance.

You are his parent. Do you give him the therapy? What do you tell him?You're ten years old. What do you want most in life? Are friends more important than intellectual superpower? Is intellectual superpower important to you? Think back a few years . . .

Scenario #3:

Thanks to the convergence of brain stimulation and brain imaging we know that your brain and mine react the same when we see a red ball. We know that red, green, or blue trigger specific patterns in our brains, and when we use eye tracking to know where we are gazing and brain imaging to see the reaction, a computer can now tell what color we are looking at.

Shapes and objects form distinct and recognizable patterns too. Supercomputers can accurately resolve thousands of common objects including cars, airplanes, dogs, cats, guns and pencils. The computers can associate emotion too, separating any house from home, and any female from mom.

Science has delivered us the ultimate lie detector. The mind probe of science fiction is real.

You have a suspected terrorist in your custody. He is placed in the scanner and shown images associated with a recent bombing. You have identified the house where the bomb was made. The suspect’s brain lights up as home. You show a picture of the carnage of the bomb. The suspect’s brain reflects a pattern of pride.

You are a government leader. What do you do with the suspect? Is a trial needed; would it serve a purpose?You are a scientist in the program. Should your newfound power be kept secret?You call yourself a freedom fighter. The enemy calls you a terrorist. How do you combat this machine?

This technology is [very likely] in development now (it’s classified.) The practical difficulty of getting uncooperative subjects into the scanner and getting them to view materials may delay deployment somewhat.

(c) 2018 John Elder Robison

John Elder Robison is an autistic adult and advocate for people with neurological differences. He's the author of Look Me in the Eye, Be Different, Raising Cubby, and Switched On. He serves on the Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee of the US Dept of Health and Human Services. He's co-founder of the TCS Auto Program (A school for teens with developmental challenges) and he’s the Neurodiversity Scholar at the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia. He's also a visiting professor of practice at Bay Path University in Longmeadow, Massachusetts and advisor to the Neurodiversity Institute at Landmark College in Putney, Vermont.

The opinions expressed here are his own. There is no warranty expressed or implied. While reading this essay will give you food for thought, actually printing and eating it may make you sick.

(c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

Published on March 26, 2018 07:41

March 17, 2018

Lobbyists and Autism Advocacy

We often read about lobbyists in the news, and in last week’s neurodiversity class we talked about what lobbying actually means. The popular perception is that of polished lobbyists wining and dining senators in upscale restaurants. The reality is often rather more prosaic.

Before new rules or programs are enacted there is generally a period when government agencies seek public comment. While anyone can send comments to government agencies or elected officials, in-person comments are often more influential. A lobbyist who travels to Washington and states a position can engage in dialogue with government. Such a person is much more likely to advance whatever position they bring with them than a write-in commenter.

If the situation under discussion is one that affects autistic people – like housing for the cognitively disabled – there is widespread agreement that a lobbyist who represents an autism society has a duty to do their best to represent all autistic people.

But what if another lobbyist comes to comment, and he represents a home builder’s association. Now imagine that the solution he is there to advocate for is in opposition to the solution preferred by the autism community. Where does that lobbyist’s duty lie?

The majority of students in our neurodiversity class felt that the home builder’s lobbyist had a duty to his employer and should advocate for their position no matter what the autism community thought.

A large number of people agree with this position, justifying it with arguments like, “there are winners and losers in every negotiation.” Some dissenters believe corporations should have consciences, and they should not do things that make them money to the detriment of large groups of people.

Now imagine that the homebuilder’s lobbyist was accompanied by a team of assistants who called and set up meetings with many of the government officials central to the decision. When the homebuilder lobbyist spoke he had a very impressive multimedia presentation and worked the room afterwards during the break. Meanwhile the public was represented by a few families who came to speak, and two individuals from autism societies, neither of whom had any of the resources of the home builder’s association.

Who do you think had the greater influence?

This example is based on real scenarios from my own time in government advocacy, and it speaks to the question of who our government represents. When lawmakers or rule makers hear from commenters before making a decision, the commenters tend to be lobbyists who speak for groups as opposed to individuals speaking for themselves. When individuals do speak for themselves it’s been my observation that the words of lobbyists on behalf of groups still have more impact.

That should not be surprising; no one should wonder that an experienced professional lobbyist would be more successful at making his arguments heard than a neophyte visitor to Washington.

However, this raises a fundamental question about the role of government: Are we a government of and for the people, or is government for the often-corporate lobbying interests? Lobbyists can work for advocacy groups on behalf of affected populations, or they can work for advocacy groups on behalf of corporations. They can also work directly for corporations.

Many times, lobbyists work for groups whose names are misleading. For example, research might reveal that “Citizens for Fairer Energy Policy” is actually a trade group for coal miners. It’s often hard to discern where the loyalties of lobbyists lie and it’s even more difficult for government officials to discern the policies that will provide the broadest public good in the face of such polished and well-funded corporate lobbying. Average citizens are generally unable to do anything like that, which leaves lawmakers listening only to the rich and the corporate to make decisions that affect everyone.

As the example of the autism society representative and the home builder’s lobbyist shows, the loyalties of many if not most lobbyists are not with the broad public. Many of the government decisions shaped by lobbyists are not Republican-Democrat in nature at all. Rather, they are “benefit the public” versus “benefit certain corporate interests.”

Even when lobbyists represent a group, the group might not be the one implied by their name nor might it be what you expect. For example, when judged by their name it sounds like Autism Speaks should be the voice of autistic people. Yet they have - from the beginning - been primarily a voice of parents and grandparents as opposed to actual autistic people. Autistic people come in all ages and abilities. Given that, and the fact most of us are adults the idea that parents of autistic children should dominate the conversations seems ridiculous but in their case that is what happened. The sad truth is that many lobbying groups are not what their names imply and it's very hard for an individual to know who truly represents their interests in Washington.

Cynics imagine government is corrupted by huge cash contributions to re-elect public officials, or lucrative post-government employment offers once compliant public officials leave office. While those things surely happen the much more insidious concern should be the massive resources corporate interests pour into lobbying and how that renders the opinions of individuals – the people government is supposed to represent – largely invisible.

The situation today is dire, but it’s not hopeless. Groups like the Autistic Self Advocacy Network demonstrate that a group of passionate people can – with very little cash expenditure but a lot of thought and commitment – move public policy in directions that are beneficial to most people. They also demonstrate that population groups who once had no voice (in this case, actually autistic people) can find voice in advocacy.

It’s tempting to say, “let’s just ban corporate lobbying.” But it’s not that simple. Public health authorities will continue to ask questions like, “what can the pharmaceutical companies do with this?” in response to proposed policies, and it’s necessary for their interest to answer for an informed decision. The goal should not be the silencing of corporate voices; rather it should be the putting them in proper perspective relative to the true public interests, which are those of the American citizens.

How might we accomplish this?

(c) 2018 John Elder Robison

John Elder Robison is an autistic adult and advocate for people with neurological differences. He's the author of Look Me in the Eye, Be Different, Raising Cubby, and Switched On. He serves on the Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee of the US Dept of Health and Human Services. He's co-founder of the TCS Auto Program (A school for teens with developmental challenges) and he’s the Neurodiversity Scholar at the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia. He's also a visiting professor of practice at Bay Path University in Longmeadow, Massachusetts and advisor to the Neurodiversity Institute at Landmark College in Putney, Vermont.

The opinions expressed here are his own. There is no warranty expressed or implied. While reading this essay will give you food for thought, actually printing and eating it may make you sick.(c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

Before new rules or programs are enacted there is generally a period when government agencies seek public comment. While anyone can send comments to government agencies or elected officials, in-person comments are often more influential. A lobbyist who travels to Washington and states a position can engage in dialogue with government. Such a person is much more likely to advance whatever position they bring with them than a write-in commenter.

If the situation under discussion is one that affects autistic people – like housing for the cognitively disabled – there is widespread agreement that a lobbyist who represents an autism society has a duty to do their best to represent all autistic people.

But what if another lobbyist comes to comment, and he represents a home builder’s association. Now imagine that the solution he is there to advocate for is in opposition to the solution preferred by the autism community. Where does that lobbyist’s duty lie?

The majority of students in our neurodiversity class felt that the home builder’s lobbyist had a duty to his employer and should advocate for their position no matter what the autism community thought.

A large number of people agree with this position, justifying it with arguments like, “there are winners and losers in every negotiation.” Some dissenters believe corporations should have consciences, and they should not do things that make them money to the detriment of large groups of people.

Now imagine that the homebuilder’s lobbyist was accompanied by a team of assistants who called and set up meetings with many of the government officials central to the decision. When the homebuilder lobbyist spoke he had a very impressive multimedia presentation and worked the room afterwards during the break. Meanwhile the public was represented by a few families who came to speak, and two individuals from autism societies, neither of whom had any of the resources of the home builder’s association.

Who do you think had the greater influence?

This example is based on real scenarios from my own time in government advocacy, and it speaks to the question of who our government represents. When lawmakers or rule makers hear from commenters before making a decision, the commenters tend to be lobbyists who speak for groups as opposed to individuals speaking for themselves. When individuals do speak for themselves it’s been my observation that the words of lobbyists on behalf of groups still have more impact.

That should not be surprising; no one should wonder that an experienced professional lobbyist would be more successful at making his arguments heard than a neophyte visitor to Washington.

However, this raises a fundamental question about the role of government: Are we a government of and for the people, or is government for the often-corporate lobbying interests? Lobbyists can work for advocacy groups on behalf of affected populations, or they can work for advocacy groups on behalf of corporations. They can also work directly for corporations.

Many times, lobbyists work for groups whose names are misleading. For example, research might reveal that “Citizens for Fairer Energy Policy” is actually a trade group for coal miners. It’s often hard to discern where the loyalties of lobbyists lie and it’s even more difficult for government officials to discern the policies that will provide the broadest public good in the face of such polished and well-funded corporate lobbying. Average citizens are generally unable to do anything like that, which leaves lawmakers listening only to the rich and the corporate to make decisions that affect everyone.

As the example of the autism society representative and the home builder’s lobbyist shows, the loyalties of many if not most lobbyists are not with the broad public. Many of the government decisions shaped by lobbyists are not Republican-Democrat in nature at all. Rather, they are “benefit the public” versus “benefit certain corporate interests.”

Even when lobbyists represent a group, the group might not be the one implied by their name nor might it be what you expect. For example, when judged by their name it sounds like Autism Speaks should be the voice of autistic people. Yet they have - from the beginning - been primarily a voice of parents and grandparents as opposed to actual autistic people. Autistic people come in all ages and abilities. Given that, and the fact most of us are adults the idea that parents of autistic children should dominate the conversations seems ridiculous but in their case that is what happened. The sad truth is that many lobbying groups are not what their names imply and it's very hard for an individual to know who truly represents their interests in Washington.

Cynics imagine government is corrupted by huge cash contributions to re-elect public officials, or lucrative post-government employment offers once compliant public officials leave office. While those things surely happen the much more insidious concern should be the massive resources corporate interests pour into lobbying and how that renders the opinions of individuals – the people government is supposed to represent – largely invisible.

The situation today is dire, but it’s not hopeless. Groups like the Autistic Self Advocacy Network demonstrate that a group of passionate people can – with very little cash expenditure but a lot of thought and commitment – move public policy in directions that are beneficial to most people. They also demonstrate that population groups who once had no voice (in this case, actually autistic people) can find voice in advocacy.

It’s tempting to say, “let’s just ban corporate lobbying.” But it’s not that simple. Public health authorities will continue to ask questions like, “what can the pharmaceutical companies do with this?” in response to proposed policies, and it’s necessary for their interest to answer for an informed decision. The goal should not be the silencing of corporate voices; rather it should be the putting them in proper perspective relative to the true public interests, which are those of the American citizens.

How might we accomplish this?

(c) 2018 John Elder Robison

John Elder Robison is an autistic adult and advocate for people with neurological differences. He's the author of Look Me in the Eye, Be Different, Raising Cubby, and Switched On. He serves on the Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee of the US Dept of Health and Human Services. He's co-founder of the TCS Auto Program (A school for teens with developmental challenges) and he’s the Neurodiversity Scholar at the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia. He's also a visiting professor of practice at Bay Path University in Longmeadow, Massachusetts and advisor to the Neurodiversity Institute at Landmark College in Putney, Vermont.

The opinions expressed here are his own. There is no warranty expressed or implied. While reading this essay will give you food for thought, actually printing and eating it may make you sick.(c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

Published on March 17, 2018 14:22

March 13, 2018

Neurodiversity and Government Advocacy

Thoughts for William & Mary neurodiversity class, March 14, 2018 . . .

What is government advocacy?

The most common form of government advocacy advances the goals of groups, which may be membership organizations, corporations, foreign governments, or other groups before our government (either state or federal.) Advocates may be professional lobbyists, lawyers, or concerned members of affected groups.

Advocates use their knowledge of issues, relationships, and experience in government to advance their agendas. In many cases they compete with – or are opposed by – other advocates with different agendas.

Often members of a group have divergent or mutually exclusive goals. Other times totally different groups focus on a single issue with identical approaches and objectives.

Most times, the group doing the advocacy defines itself and the advocacy. Other times, the central government defines the group, and seeks representatives.

There is another form of advocacy within our legal system. In that, individuals or groups advance their agendas through or on behalf of individual defendants or plaintiffs.

Are there other forms of government advocacy, and if so, what are they?

What can government do for the community of Neurodivergent people?

Government can do many things at the request of advocates. Among other things, it can . . .Conduct research to find solutions to problems,Study and develop medical treatments,Institute protections from discrimination or marginalization,Encourage employment of disadvantaged groups,Provide protections, legal, physical, environmental, and other,Directly employ members of a group in government service,Provide housing, sustenance, and support to needy groups

Through legal advocacy, government can be encouraged to do a better job of sheltering us from harm, making our lives more comfortable, keeping us safe, granting us relief, or extending compassion or mercy in criminal sentencing.

How does neurodiversity fit in?

With respect to neurodiversity, there is no recognized group as regards government advocacy. That’s because neurodiversity is only a concept. It’s not a defined medical condition needing treatment. It’s not a defined population needing benefits or services. It’s not a recognized group needing legislative protection.

Rather, the concept of neurodiversity is that there is a subgroup of humanity who have inborn neurological differences that make them cognitively different from “typical” humans. These neurodivergent individuals learn differently, process information differently, and think and solve problems via different pathways. Compared to typical people they exhibit a mix of disability and exceptionality.

The most widely recognized neurological difference is ADHD. The next most common are OCD, Dyslexia, and Autism. Most (but not all) people outgrow or learn to manage the first three conditions by adulthood, so there is not a large call for adult research or support. Many autistic people have some level of lifelong disability severe enough to require support. Autism is the most visibly disabling of the neurological differences.

No government agency I know of recognizes neurodiversity as a movement or group with which they would engage in dialogue, or support. Rather, the government recognizes and supports the constituent groups who make up the neurodivergent community. This includes autistic people and their families, the ADHD community, folks with dyslexia, and the cognitive disability community more generally.

We may think of neurological diversity as conferring a mix of disability and exceptionality but in general the government only provides support and services to people with disabilities.

Who advocates for neurodivergent people?

Advocacy groups like the Autistic Self Advocacy Network, the Autism Society, the Simons Foundation, and Autism Speaks advocate for autistic people, but from different perspectives.

Groups like The Arc and Easter Seals advocate for neurodivergent people in the context of advocating for all people with cognitive disabilities or all people with disabilities.

Affected and concerned individuals advocate for specific medical conditions before our public health agencies (NIH, CDC, DOD.)

Attorneys, medical professionals and (only very recently) qualified affected individuals advocate for neurodivergent individuals in the legal system.

Why do people advocate in the neurodiversity realm?

Each advocacy group has its own agenda. Sometimes their advocacy is broad and deep with respect to our community. Other times it is very narrow.

The original neurodiversity advocates were the parents who advocated for educational, living, and employment supports for their neurodivergent children. When we talk about advocacy for, say, autistic people . . . should parents be recognized as part of the community? In this example, should teachers, doctors, and others who help and support autistics be part of the community?The population of children diagnosed with neurodivergent conditions has exploded since the 1990s. The first generation of those children have reached adulthood and some have emerged as advocates. Some neurodivergent members of prior generations are also advocates.How might the pre and post 90s’ generations of neurodivergent people differ in views and advocacy?How and why might the opinions or goals of parents and children diverge?When parents and children have divergent opinions, whose should be primary?

Educators have been overwhelmed by the surge in students needing special education services and accommodations. They advocate for better support tools and financial support. They may also advocate for injunctive relief from burdens imposed by government regulations they feel unable to meet.

Medical professionals advocate for research to identify the needs of neurodivergent people. This is an emerging trend.

More traditionally, medical professionals assumed they knew or could personally determine what was needed to help neurodivergent people, and they advocated for research or other support to do so.

Medical corporations advocate for support and protection to encourage or enable the development of medications and treatment devices.What are some examples of government supporting the development of medications?What are some examples of government protecting corporations who develop medications or treatments?Should government take a role supporting or protecting corporations? Why or why not?

Individual government agencies have ideas that impact the neurodivergent population. They often state positions and then engage the public to defend or revise those positions. What would be some examples?Should the armed forces ban people with autism and ADHD?Should the rules that govern six college students renting rooms in a house differ from the rules for six cognitively disabled people living in a similar house?

When advocates approach the government to advance their views, how should government balance the goals of affected individuals who advocate for themselves or their groups, versus representatives of corporations?If, as some have suggested, corporations are people in a legal sense, how do we balance their vastly greater lobbying resources against the concerns of individuals?The Citizens United case is often cited in the context of corporate influence over elections. Are elections a unique situation or is there actually a broader issue of corporate versus individual influence over government policy making?A corporation and an individual are clearly different, right? Merck pharmaceuticals is different from John Smith who takes Merck-made drugs. He and Merck may advocate for different things, or the same thing. If we distinguish between corporate and individual advocacy, on which side should we place advocacy from groups like autism societies, or educator’s associations?

When a person decides to engage in government advocacy on behalf of a group, like the population of neurodivergent people . . .Should there be a qualification process for a potential advocate? Is there a process?When an advocate speaks for a community, what is the moral imperative to advocate for the best of all, as opposed to what's best for the advocate?Assuming an advocate is a qualified member of a community (a diagnosed autistic person on an autism committee, or a recognized member of a tribe on an Indian affairs committee) does the advocate have a duty to gain a special understanding of issues, or is general life experience enough?

How does neurodiversity advocacy differ from advocacy for other issues in the news today, such as gun control, women's reproductive rights, or gay marriage? Does it differ?

How would a William & Mary grad get into advocacy, either as a career, a personal passion, or both?Careers in government,Working for political consulting, public relations, or law firms that engage in lobbying,Working for think tanks that generate research to inform lobbying (such firms share the building housing the W&M Washington DC campus),Volunteering as an individual representative of a community to government,Working as a group representative for community before government,Expressing ideas which shape public policy through mass mediaHow else might you engage in government advocacy?

Interested in getting involved yourself?

Thoughts on advocacy from Britains National Autistic Society

Here are policy advocacy toolkits from the Autistic Self Advocacy Network

This blog talks about research at the Dept. of Defense and how you could get involved

The IACC (the federal autism committee) welcomes the public to its meetings by webcast or in person, and makes all records available online

(c) 2018 John Elder Robison

John Elder Robison is an autistic adult and advocate for people with neurological differences. He's the author of Look Me in the Eye, Be Different, Raising Cubby, and Switched On. He serves on the Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee of the US Dept of Health and Human Services. He's co-founder of the TCS Auto Program (A school for teens with developmental challenges) and he’s the Neurodiversity Scholar at the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia. He's also a visiting professor of practice at Bay Path University in Longmeadow, Massachusetts and advisor to the Neurodiversity Institute at Landmark College in Putney, Vermont.

The opinions expressed here are his own. There is no warranty expressed or implied. While reading this essay will give you food for thought, actually printing and eating it may make you sick.

(c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

What is government advocacy?

The most common form of government advocacy advances the goals of groups, which may be membership organizations, corporations, foreign governments, or other groups before our government (either state or federal.) Advocates may be professional lobbyists, lawyers, or concerned members of affected groups.

Advocates use their knowledge of issues, relationships, and experience in government to advance their agendas. In many cases they compete with – or are opposed by – other advocates with different agendas.

Often members of a group have divergent or mutually exclusive goals. Other times totally different groups focus on a single issue with identical approaches and objectives.

Most times, the group doing the advocacy defines itself and the advocacy. Other times, the central government defines the group, and seeks representatives.

There is another form of advocacy within our legal system. In that, individuals or groups advance their agendas through or on behalf of individual defendants or plaintiffs.

Are there other forms of government advocacy, and if so, what are they?

What can government do for the community of Neurodivergent people?

Government can do many things at the request of advocates. Among other things, it can . . .Conduct research to find solutions to problems,Study and develop medical treatments,Institute protections from discrimination or marginalization,Encourage employment of disadvantaged groups,Provide protections, legal, physical, environmental, and other,Directly employ members of a group in government service,Provide housing, sustenance, and support to needy groups

Through legal advocacy, government can be encouraged to do a better job of sheltering us from harm, making our lives more comfortable, keeping us safe, granting us relief, or extending compassion or mercy in criminal sentencing.

How does neurodiversity fit in?

With respect to neurodiversity, there is no recognized group as regards government advocacy. That’s because neurodiversity is only a concept. It’s not a defined medical condition needing treatment. It’s not a defined population needing benefits or services. It’s not a recognized group needing legislative protection.

Rather, the concept of neurodiversity is that there is a subgroup of humanity who have inborn neurological differences that make them cognitively different from “typical” humans. These neurodivergent individuals learn differently, process information differently, and think and solve problems via different pathways. Compared to typical people they exhibit a mix of disability and exceptionality.

The most widely recognized neurological difference is ADHD. The next most common are OCD, Dyslexia, and Autism. Most (but not all) people outgrow or learn to manage the first three conditions by adulthood, so there is not a large call for adult research or support. Many autistic people have some level of lifelong disability severe enough to require support. Autism is the most visibly disabling of the neurological differences.

No government agency I know of recognizes neurodiversity as a movement or group with which they would engage in dialogue, or support. Rather, the government recognizes and supports the constituent groups who make up the neurodivergent community. This includes autistic people and their families, the ADHD community, folks with dyslexia, and the cognitive disability community more generally.

We may think of neurological diversity as conferring a mix of disability and exceptionality but in general the government only provides support and services to people with disabilities.

Who advocates for neurodivergent people?

Advocacy groups like the Autistic Self Advocacy Network, the Autism Society, the Simons Foundation, and Autism Speaks advocate for autistic people, but from different perspectives.

Groups like The Arc and Easter Seals advocate for neurodivergent people in the context of advocating for all people with cognitive disabilities or all people with disabilities.

Affected and concerned individuals advocate for specific medical conditions before our public health agencies (NIH, CDC, DOD.)

Attorneys, medical professionals and (only very recently) qualified affected individuals advocate for neurodivergent individuals in the legal system.

Why do people advocate in the neurodiversity realm?

Each advocacy group has its own agenda. Sometimes their advocacy is broad and deep with respect to our community. Other times it is very narrow.

The original neurodiversity advocates were the parents who advocated for educational, living, and employment supports for their neurodivergent children. When we talk about advocacy for, say, autistic people . . . should parents be recognized as part of the community? In this example, should teachers, doctors, and others who help and support autistics be part of the community?The population of children diagnosed with neurodivergent conditions has exploded since the 1990s. The first generation of those children have reached adulthood and some have emerged as advocates. Some neurodivergent members of prior generations are also advocates.How might the pre and post 90s’ generations of neurodivergent people differ in views and advocacy?How and why might the opinions or goals of parents and children diverge?When parents and children have divergent opinions, whose should be primary?

Educators have been overwhelmed by the surge in students needing special education services and accommodations. They advocate for better support tools and financial support. They may also advocate for injunctive relief from burdens imposed by government regulations they feel unable to meet.

Medical professionals advocate for research to identify the needs of neurodivergent people. This is an emerging trend.

More traditionally, medical professionals assumed they knew or could personally determine what was needed to help neurodivergent people, and they advocated for research or other support to do so.

Medical corporations advocate for support and protection to encourage or enable the development of medications and treatment devices.What are some examples of government supporting the development of medications?What are some examples of government protecting corporations who develop medications or treatments?Should government take a role supporting or protecting corporations? Why or why not?

Individual government agencies have ideas that impact the neurodivergent population. They often state positions and then engage the public to defend or revise those positions. What would be some examples?Should the armed forces ban people with autism and ADHD?Should the rules that govern six college students renting rooms in a house differ from the rules for six cognitively disabled people living in a similar house?

When advocates approach the government to advance their views, how should government balance the goals of affected individuals who advocate for themselves or their groups, versus representatives of corporations?If, as some have suggested, corporations are people in a legal sense, how do we balance their vastly greater lobbying resources against the concerns of individuals?The Citizens United case is often cited in the context of corporate influence over elections. Are elections a unique situation or is there actually a broader issue of corporate versus individual influence over government policy making?A corporation and an individual are clearly different, right? Merck pharmaceuticals is different from John Smith who takes Merck-made drugs. He and Merck may advocate for different things, or the same thing. If we distinguish between corporate and individual advocacy, on which side should we place advocacy from groups like autism societies, or educator’s associations?

When a person decides to engage in government advocacy on behalf of a group, like the population of neurodivergent people . . .Should there be a qualification process for a potential advocate? Is there a process?When an advocate speaks for a community, what is the moral imperative to advocate for the best of all, as opposed to what's best for the advocate?Assuming an advocate is a qualified member of a community (a diagnosed autistic person on an autism committee, or a recognized member of a tribe on an Indian affairs committee) does the advocate have a duty to gain a special understanding of issues, or is general life experience enough?

How does neurodiversity advocacy differ from advocacy for other issues in the news today, such as gun control, women's reproductive rights, or gay marriage? Does it differ?

How would a William & Mary grad get into advocacy, either as a career, a personal passion, or both?Careers in government,Working for political consulting, public relations, or law firms that engage in lobbying,Working for think tanks that generate research to inform lobbying (such firms share the building housing the W&M Washington DC campus),Volunteering as an individual representative of a community to government,Working as a group representative for community before government,Expressing ideas which shape public policy through mass mediaHow else might you engage in government advocacy?

Interested in getting involved yourself?

Thoughts on advocacy from Britains National Autistic Society

Here are policy advocacy toolkits from the Autistic Self Advocacy Network

This blog talks about research at the Dept. of Defense and how you could get involved

The IACC (the federal autism committee) welcomes the public to its meetings by webcast or in person, and makes all records available online

(c) 2018 John Elder Robison

John Elder Robison is an autistic adult and advocate for people with neurological differences. He's the author of Look Me in the Eye, Be Different, Raising Cubby, and Switched On. He serves on the Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee of the US Dept of Health and Human Services. He's co-founder of the TCS Auto Program (A school for teens with developmental challenges) and he’s the Neurodiversity Scholar at the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia. He's also a visiting professor of practice at Bay Path University in Longmeadow, Massachusetts and advisor to the Neurodiversity Institute at Landmark College in Putney, Vermont.

The opinions expressed here are his own. There is no warranty expressed or implied. While reading this essay will give you food for thought, actually printing and eating it may make you sick.

(c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

Published on March 13, 2018 09:07

January 29, 2018

Look Me in the Eye in Australia

One of the exciting things about this publication process is the fact that my book is appearing all over the English-speaking world. This blog has a photo of the American cover, but that's not the only edition of the book.

Look Me in the Eye is being published in Australia and New Zealand in October, and then three months later in the British Isles.

(c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

Look Me in the Eye is being published in Australia and New Zealand in October, and then three months later in the British Isles.

(c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

Published on January 29, 2018 08:32

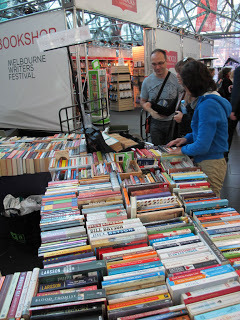

Thoughts from Australia

This is my last day at the Melbourne Writer's Festival. I'll be doing my last program at 4PM, and then it's off the University of Western Australia in Perth. Thanks to the organizers and sponsors for bringing me down here, and also to Antonia Hayes at Random House for setting everything up.

The Festival is held in the Australia Center for the Moving Image, a striking complex on the Yarra River. This is BMW EDGE. I was a guest there for the Friday night event.

The people have all been friendly. Here are some other images of the festival

As an American who's never been here before I can't help but see some contrasts between this country and my own. The first thing I saw was the cars.

(c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

The Festival is held in the Australia Center for the Moving Image, a striking complex on the Yarra River. This is BMW EDGE. I was a guest there for the Friday night event.

The people have all been friendly. Here are some other images of the festival

As an American who's never been here before I can't help but see some contrasts between this country and my own. The first thing I saw was the cars.

(c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

Published on January 29, 2018 08:22

January 28, 2018

The blog is updated

I am pleased to announce the first-ever change in the style of this blog. I hope you find it more accessible and usable.

Circus at The Big E, West Springfield, MA

Circus at The Big E, West Springfield, MA

John Rando's Long Wheelbase Shadow restoration takes 1st at the RROC National Meet

John Rando's Long Wheelbase Shadow restoration takes 1st at the RROC National Meet

Flowers in the Garden

Flowers in the Garden

On the big stage, Big E

On the big stage, Big E

Volcano

Volcano

Southwest desert

Southwest desert

Bentley Flying Spur

Bentley Flying Spur

San Francisco cable car

San Francisco cable car

Inside a transmission

Inside a transmission

(c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

Circus at The Big E, West Springfield, MA

Circus at The Big E, West Springfield, MA John Rando's Long Wheelbase Shadow restoration takes 1st at the RROC National Meet

John Rando's Long Wheelbase Shadow restoration takes 1st at the RROC National Meet Flowers in the Garden

Flowers in the Garden On the big stage, Big E

On the big stage, Big E Volcano

Volcano Southwest desert

Southwest desert Bentley Flying Spur

Bentley Flying Spur San Francisco cable car

San Francisco cable car Inside a transmission

Inside a transmission(c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

Published on January 28, 2018 13:54

January 5, 2018

Join us in Washington for January IACC - the US Govt's autism committee

Meeting of the Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee (IACC)

Please join us for an IACC Full Committee meeting that will take place on Wednesday, January 17, 2018 from 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. ET at the Bethesda Marriott Hotel, 5151 Pooks Hill Road, Bethesda, MD 20814. Onsite registration will begin at 8:00 a.m. The meeting will also be available by live webcast and conference call.

Agenda: To discuss business, updates, and issues related to ASD research and services activities.

Meeting location:

Bethesda Marriot Hotel

5151 Pooks Hill Road

Bethesda, MD 20814

Access

Medical Center (Red Line) in combination with a 26 minute walk or short taxi ride; parking available at the hotel those who drive

Security:

Visitors will be asked to sign in and show one form of identification (for example, a government-issued photo ID, driver’s license, or passport) at the meeting registration desk during the check-in process. Pre-registration is recommended. Seating will be limited to the room capacity and seats will be on a first come, first served basis, with expedited check-in for those who are pre-registered.

Remote Access:

The meeting will be remotely accessible by videocast and conference call. Members of the public who participate using the conference call phone number will be in listen-only mode.

Public Comment – Guidelines:

Any member of the public interested in presenting oral comments to the Committee must notify the Contact Person listed on this notice by 5:00 p.m. ET on Friday, January 5, 2018, with their request to present oral comments at the meeting, and a written/electronic copy of the oral presentation/statement must be submitted by 5:00 p.m. ET on Tuesday, January 9, 2018.

A limited number of slots for oral comment are available, and in order to ensure that as many different individuals are able to present throughout the year as possible, any given individual only will be permitted to present oral comments once per calendar year (2018). Only one representative of an organization will be allowed to present oral comments in any given meeting; other representatives of the same group may provide written comments. If the oral comment session is full, individuals who could not be accommodated are welcome to provide written comments instead. Commenters will have 3-5 minutes to present their comments depending on the number of commenters, but a longer version may be submitted in writing for the record. Commenters going beyond their given time slot in the meeting may be asked to conclude immediately in order to allow other comments and presentations to proceed on schedule.

Any interested person may submit written public comments to the IACC prior to the meeting by e-mailing the comments to IACCPublicInquiries@mail.nih.govor by submitting comments at the web link: https://iacc.hhs.gov/meetings/public-comments/submit/index.jsp by 5:00 p.m. ET on Tuesday, January 9, 2018. The comments should include the name and e-mail address for contact purposes, and when applicable, the business or professional affiliation of the interested person. NIMH anticipates written public comments received by 5:00 p.m. ET on Tuesday, January 9, 2018 will be presented to the Committee prior to the meeting for the Committee’s consideration. Any written comments received after the 5:00 p.m. ET, January 9, 2018 deadline through January 16, 2018 will be provided to the Committee either before or after the meeting, depending on the volume of comments received and the time required to process them in accordance with privacy regulations and other applicable Federal policies. All written public comments and oral public comment statements received by the deadlines for both oral and written public comments will be provided to the IACC for their consideration and will become part of the public record. Attachments of copyrighted publications are not permitted, but web links or citations for any copyrighted works cited may be provided.

Public Comment – Deadlines:

Notification of intent to present oral comments: Friday, January 5, 2018 by 5:00 p.m. ET

Submission of written/electronic statement for oral comments: Tuesday, January 9, 2018 by 5:00 p.m. ET

Submission of written comments: Tuesday, January 9, 2018 by 5:00 p.m. ET

Conference Call Access

USA/Canada Phone Number: 888-928-9527

Access code: 6435114

Individuals who participate using this service and who need special assistance, such as captioning of the conference call or other reasonable accommodations, should submit a request to the Contact Person listed below at least five days prior to the meeting. If you experience any technical problems with the conference call or webcast, please e-mail iaccpublicinquiries@mail.nih.gov.

Please visit the IACC Meetings page for the latest information about the meeting, including remote access information, the agenda, materials, and information about prior IACC events.

Contact Person for this meeting is:

Ms. Angelice Mitrakas

Office of Autism Research Coordination

National Institute of Mental Health, NIH

6001 Executive Boulevard, NSC

Room 6183A

Rockville, MD 20852

Phone: 301-435-9269

E-mail: IACCpublicinquiries@mail.nih.gov(c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

Please join us for an IACC Full Committee meeting that will take place on Wednesday, January 17, 2018 from 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. ET at the Bethesda Marriott Hotel, 5151 Pooks Hill Road, Bethesda, MD 20814. Onsite registration will begin at 8:00 a.m. The meeting will also be available by live webcast and conference call.

Agenda: To discuss business, updates, and issues related to ASD research and services activities.

Meeting location:

Bethesda Marriot Hotel

5151 Pooks Hill Road

Bethesda, MD 20814

Access

Medical Center (Red Line) in combination with a 26 minute walk or short taxi ride; parking available at the hotel those who drive

Security:

Visitors will be asked to sign in and show one form of identification (for example, a government-issued photo ID, driver’s license, or passport) at the meeting registration desk during the check-in process. Pre-registration is recommended. Seating will be limited to the room capacity and seats will be on a first come, first served basis, with expedited check-in for those who are pre-registered.

Remote Access:

The meeting will be remotely accessible by videocast and conference call. Members of the public who participate using the conference call phone number will be in listen-only mode.

Public Comment – Guidelines:

Any member of the public interested in presenting oral comments to the Committee must notify the Contact Person listed on this notice by 5:00 p.m. ET on Friday, January 5, 2018, with their request to present oral comments at the meeting, and a written/electronic copy of the oral presentation/statement must be submitted by 5:00 p.m. ET on Tuesday, January 9, 2018.

A limited number of slots for oral comment are available, and in order to ensure that as many different individuals are able to present throughout the year as possible, any given individual only will be permitted to present oral comments once per calendar year (2018). Only one representative of an organization will be allowed to present oral comments in any given meeting; other representatives of the same group may provide written comments. If the oral comment session is full, individuals who could not be accommodated are welcome to provide written comments instead. Commenters will have 3-5 minutes to present their comments depending on the number of commenters, but a longer version may be submitted in writing for the record. Commenters going beyond their given time slot in the meeting may be asked to conclude immediately in order to allow other comments and presentations to proceed on schedule.

Any interested person may submit written public comments to the IACC prior to the meeting by e-mailing the comments to IACCPublicInquiries@mail.nih.govor by submitting comments at the web link: https://iacc.hhs.gov/meetings/public-comments/submit/index.jsp by 5:00 p.m. ET on Tuesday, January 9, 2018. The comments should include the name and e-mail address for contact purposes, and when applicable, the business or professional affiliation of the interested person. NIMH anticipates written public comments received by 5:00 p.m. ET on Tuesday, January 9, 2018 will be presented to the Committee prior to the meeting for the Committee’s consideration. Any written comments received after the 5:00 p.m. ET, January 9, 2018 deadline through January 16, 2018 will be provided to the Committee either before or after the meeting, depending on the volume of comments received and the time required to process them in accordance with privacy regulations and other applicable Federal policies. All written public comments and oral public comment statements received by the deadlines for both oral and written public comments will be provided to the IACC for their consideration and will become part of the public record. Attachments of copyrighted publications are not permitted, but web links or citations for any copyrighted works cited may be provided.

Public Comment – Deadlines:

Notification of intent to present oral comments: Friday, January 5, 2018 by 5:00 p.m. ET

Submission of written/electronic statement for oral comments: Tuesday, January 9, 2018 by 5:00 p.m. ET

Submission of written comments: Tuesday, January 9, 2018 by 5:00 p.m. ET

Conference Call Access

USA/Canada Phone Number: 888-928-9527

Access code: 6435114

Individuals who participate using this service and who need special assistance, such as captioning of the conference call or other reasonable accommodations, should submit a request to the Contact Person listed below at least five days prior to the meeting. If you experience any technical problems with the conference call or webcast, please e-mail iaccpublicinquiries@mail.nih.gov.

Please visit the IACC Meetings page for the latest information about the meeting, including remote access information, the agenda, materials, and information about prior IACC events.

Contact Person for this meeting is:

Ms. Angelice Mitrakas

Office of Autism Research Coordination

National Institute of Mental Health, NIH

6001 Executive Boulevard, NSC

Room 6183A

Rockville, MD 20852

Phone: 301-435-9269

E-mail: IACCpublicinquiries@mail.nih.gov(c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

Published on January 05, 2018 06:17

December 15, 2017

Limiters, Compressors, and how to play music loud

The excessive volume of commercials has struck everyone who’s watched television. You’re watching a show at a comfortable volume, and there’s a commercial break, and suddenly you are blasted out of your seat. If you had the volume on 5 it feels like it just went up to 100, all by itself. How does that happen?

I was reminded of that question when reading a new book - Damon Krukowski’s The New Analog – Listening and Reconnecting in a Digital World. The book tackles that question in the context of the transition from analog to digital audio and television. Younger readers may not remember that transition (it was a process, not a single event) but all of us who were adults in the 1980s lived through it not once but many times.

Journey in concert (c) John E Robison

Journey in concert (c) John E RobisonFirst there was the transition from vinyl records (analog) to compact discs (digital.) Then the audio processing went digital, with smartphone apps replacing sound processors and digital Bluetooth links replacing analog headphone cords. Call phones started as analog and now are all digital, and far more capable for the change.

But interestingly, it’s not digital technology that allows those commercials to blast us. That is an old analog trick that came from the radio broadcast world seventy-plus years ago.

In his book Krukowski shows waveform samples from two versions of a popular song, showing how one version has “normal” dynamic range and the “loud” version has everything pressed to the maximum. Any listener would say the second version is louder than the first, but an engineer would point out that the peak energy in both programs is the same.

Krukowski explains that everything was turned up, but maximum volume remained the same, so that the soft passages got louder and the loud passages all became 100%, or full volume. What he does not explain is how that happened without the music getting horribly distorted.

Building upon his excellent book I’d like to offer that missing explanation. The answer to how music got louder is compression and limiting, two technologies that existed for a long time but which were enhanced dramatically in the 1970s.

I designed compression and limiting systems when I worked as an audio engineer. Limiters were originally developed for radio broadcasting, where too much program volume corrupted the radio transmission. Limiters prevented that by turning the program down automatically if the radio announcer got too exuberant.

Limiters operate by measuring the peak level of a program and turning down volume when a preset threshold is exceeded. If the limiting threshold is set below the level a sound system can deliver cleanly, the system will in principle always be clean.

As concert sound systems grew larger in the 1970s sound engineers realized something else. When amplifiers are driven beyond full power the output waveform is “clipped” at the maximum level the system can deliver. Clipping turns a smooth musical wave into a harsh square wave. Listeners know this clipping as “fuzz,” a sound effect that remains popular today. When one instrument is clipped the effect sounds purposeful. When the whole musical program is clipped, the whole program sounds bad.

Sound quality is not the only casualty when amplifiers clip. Clipping is also destructive to speakers. In fact, most concert speaker failures are traceable to excessive clipping. Horn drivers are prone to shatter and voice coils in speakers overheat and deform.

In 1978 I spent the whole of April Wine’s FirstGlance tour replacing speaker diaphragms after they shattered from the lack of limiters in Pink Floyd’s Britannia Row rental sound system. It was that tour that showed us the need for limiters on each of the amplifier banks in a multi-way system.

April Wine - First Glance tour plans photo (c) John E Robison

April Wine - First Glance tour plans photo (c) John E RobisonLimiters prevent that by keeping amplifiers from breaking into their clip or overload region. When a limiter is triggering occasionally it’s said to be “peak limiting” which is an acoustically transparent thing. The only thing listeners notice is the absence of clip distortion.

If the program level is raised as the limit threshold is lowered the limiter begins operating all the time, as opposed to only during loud passages. When a limiter is used in that way it’s called a compressor because it’s reducing the dynamic range (ratio of loud to soft parts) of the program.

Limiters are usually set up with “hard” limits, meaning material that exceeds their limit threshold are reduced in overall volume to stay under the threshold level.

Compressors, on the other hand, have “soft” limits, meaning signals that exceed the threshold are limited, but in ratio. So a burst that exceeds the limit threshold by 50% might be limited to just 25% increase at the output.

Soft limits reduce dynamic range without limiting peak volume so they still allow amplifiers to go into clip distortion (and radio stations to overload.) Consequently they are not seen in those applications. Hard limiting is the rule there. Soft limiting is used when producers want to compress the dynamic range of a music program; for example to make it more audible in a crowded area, or to make it seem louder at a given volume setting.

Soft limiting for compression followed by hard limiting for overload protection is the technique that delivers maximum average sound levels in live performance and the loudest program on playback.

Lower frequencies (bass) use most of the power in a concert sound system so the bass speakers are usually driven by separate amplifiers. For maximum volume we applied separate limiters to the bass amps and the higher frequency amps. As volume rose, the bass would be heavily limited even as the highs remained untouched, with their full dynamic range. That bass limiting made for a very solid steady foundation that became part of the characteristic sound of the disco/soul/funk era.

While some musicians used limiting or compression as an effect on individual instruments it was mostly a tool to get more reliability and volume from house sound systems. As far as I know that remains true today.

The main difference between limiters and compressors of the 1970s and the units in use today is that the sound signals are now digital, and compression/limiting is done in software rather than by purpose-built circuits.

Digital limiting allows for a range of options that could not be accomplished with analog circuits, particularly in the studio. For example, digital compression software can evaluate a whole song and apply smoother compression and limiting by looking ahead and behind the peaks before calculating adjustments.

The main tradeoff of digital limiting is that it takes time to do the calculations, and the application of limiting contributes a few milliseconds of delay to the signal flow. Some musicians are bothered by that latency if they hear the house sound system on stage. Others won’t notice, or will ignore it as they ignore natural hall echoes and delays. Analog limiters don't have delays.

When you hear music or commercials that are far louder than you expect on the radio or tv, you can thank limiting and compression for it. When you hear LOUD on a concert stage, it's limiting, compression, and possibly just a shitload of horsepower in the amplifiers.

John Elder Robison

John Elder Robison is an autistic adult and advocate for people with neurological differences. He's the author of Look Me in the Eye, Be Different, Raising Cubby, and Switched On. He serves on the Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee of the US Dept of Health and Human Services and many other autism-related boards. He's co-founder of the TCS Auto Program (A school for teens with developmental challenges) and he’s the Neurodiversity Scholar in Residence at the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia and a visiting professor of practice at Bay Path University in Longmeadow, Massachusetts.

The opinions expressed here are his own. There is no warranty expressed or implied. While reading this essay will give you food for thought, actually printing and eating it may make you sick.

(c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

Published on December 15, 2017 08:37

December 8, 2017

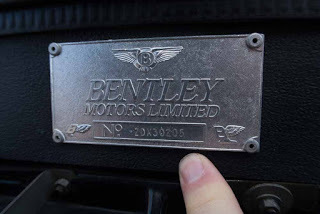

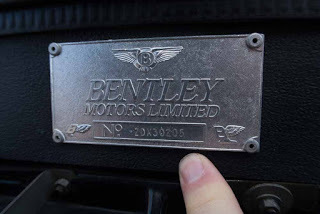

Rolls-Royce and Bentley serial numbers - 1980s and early 1990s

Modern cars have standard machine readable vehicle identification (VIN) numbers. Old cars have numbering methods that vary from one brand to the next. In this essay I will show you what numbers look like on Rolls-Royce and Bentley motorcars from the 1970s Shadow through the 1990s Spur era

This article is illustrated with images of a 1983 Rolls-Royce and a 1990 Bentley. The 1983 car is a Corniche Drophead; the 1990 is a Continental Convertible

The number plate most people know is in the driver door jamb - the area of body in front of the front door. You should see a small plate that identifies the model (Continental in this example) and a larger plate with the date of manufacture and gross vehicle weight (the maximum the car can weigh, fully loaded) and the gross axle weights (the maximum weight on each axle, fully loaded.)

The large plate has the vehicle identification number and say the car meets requirements for whatever market for which it was originally built. The photo here shows a US market car but other markets are similar.

Cars built after 1987 should have bar code tags with a machine readable version of the VIN at the rear edge of the doors, as shown below:

You should see a metal plate with the VIN at the base or side edge of the windshield:

If you open the hood (bonnet) you will see a body number plate on the firewall. This shows the body number, which is the fourth digit of the VIN, and the last 7 digits. Reading the plate below you can see how the body number is derived from the whole VIN, shown in the photos above at the windshield base.

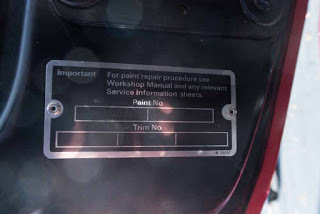

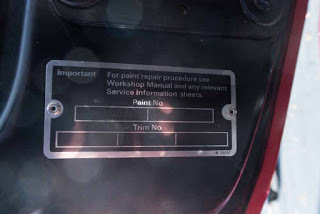

The plate on the left underside face of the bonnet (hood) gives the paint and interior trim codes. Some cars will have one code; two-tone vehicles will have two.

The VIN is also stamped into a structural part of the body on or adjacent to the right front strut tower or wheel well, as shown below. Newer cars will have a bar code VIN tag on the strut tower also.

Here is an excellent article on decoding Rolls-Royce and Bentley numbers.

Here is an earlier article on chassis and engine serial numbers, using a 1972 car as example. This is on the Robison Service blog also

© 2017 John Elder Robison

John Elder Robison is the general manager of J E Robison Service Company, celebrating 30 years of independent Bentley, Rolls-Royce, BMW/MINI, Mercedes, and Land Rover restoration and repair in Springfield, Massachusetts. John is a longtime technical consultant to the car clubs, and he’s owned and restored many fine British and German motorcars. Find him online at www.robisonservice.com or in the real world at 413-785-1665

Reading this article will make you smarter, especially when it comes to car stuff. So it's good for you. But don't take that too far - printing and eating it will probably make you sick.

(c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

This article is illustrated with images of a 1983 Rolls-Royce and a 1990 Bentley. The 1983 car is a Corniche Drophead; the 1990 is a Continental Convertible

The number plate most people know is in the driver door jamb - the area of body in front of the front door. You should see a small plate that identifies the model (Continental in this example) and a larger plate with the date of manufacture and gross vehicle weight (the maximum the car can weigh, fully loaded) and the gross axle weights (the maximum weight on each axle, fully loaded.)

The large plate has the vehicle identification number and say the car meets requirements for whatever market for which it was originally built. The photo here shows a US market car but other markets are similar.

Cars built after 1987 should have bar code tags with a machine readable version of the VIN at the rear edge of the doors, as shown below:

You should see a metal plate with the VIN at the base or side edge of the windshield:

If you open the hood (bonnet) you will see a body number plate on the firewall. This shows the body number, which is the fourth digit of the VIN, and the last 7 digits. Reading the plate below you can see how the body number is derived from the whole VIN, shown in the photos above at the windshield base.

The plate on the left underside face of the bonnet (hood) gives the paint and interior trim codes. Some cars will have one code; two-tone vehicles will have two.

The VIN is also stamped into a structural part of the body on or adjacent to the right front strut tower or wheel well, as shown below. Newer cars will have a bar code VIN tag on the strut tower also.

Here is an excellent article on decoding Rolls-Royce and Bentley numbers.

Here is an earlier article on chassis and engine serial numbers, using a 1972 car as example. This is on the Robison Service blog also

© 2017 John Elder Robison

John Elder Robison is the general manager of J E Robison Service Company, celebrating 30 years of independent Bentley, Rolls-Royce, BMW/MINI, Mercedes, and Land Rover restoration and repair in Springfield, Massachusetts. John is a longtime technical consultant to the car clubs, and he’s owned and restored many fine British and German motorcars. Find him online at www.robisonservice.com or in the real world at 413-785-1665

Reading this article will make you smarter, especially when it comes to car stuff. So it's good for you. But don't take that too far - printing and eating it will probably make you sick.

(c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

Published on December 08, 2017 10:40

December 3, 2017