John Elder Robison's Blog, page 2

February 25, 2019

A Letter to High School Students

Over the past week I received a dozen letters from students who read Look Me in the Eye as part of English class in Southbury CT. At first I thought to answer them one by one, but now they're coming by the dozen and I thought I'd answer them all here.

You asked about my childhood pranks. Why did I do them, and how could I do such awful things? Two passages in the book seemed to stand out for a number of you. One was when my parents were taking us to a therapist, and my little brother was too young to accompany us. I was about 14, and he was 6. I suggested we chain Varmint (that was what I named him) up in the basement, and several of you asked: was that sarcasm, or did I really do it?

Yes, I really called him Varmint. Many of you have brothers and sisters. I suspect, if you admit the truth, each of you has wished to chain your sibling in the basement on more than one occasion. Did you actually do it, or was it only an idea? Remember, in the book I just suggest it.

The second thing you noted was the hanging of the mannequin. You asked how and why I’d do such a thing. It started with the abandoned clothing store dummy. I could not leave such a treasure to be carried off with the trash, and I had to think of something to do with it.

Several of you observed that you could be arrested and punished if you did such a thing today. I agree, you could. But times were different when I was growing up. Keep in mind that I wrote the book about growing up in a small town in Western Massachusetts, and I still live there today.

The book does not say this, but later in life, I got to know the owner of that store. She remembered me carrying off the mannequin, and proudly put a signed copy of the story on her wall. Many of the people who appear in my stories remain friends today.

One of you remarked on the time I sent my biology teacher a truckload of gravel. Years later, I met the owner of the quarry, and he still remembers the irate call from my teacher. So the takeaway from that is, however awful those things may seem when you read them on paper, in town they were just kid pranks, and we remember them fondly.

Compare that with today, where everything around school is tightly regulated. No one talks things over anymore. You have fights at school and the police are called. Everyone turns to the authorities to solve problems because the ability to work things out has been lost. Sure, my pranks were irritating. But how does that compare to today, when an angry student comes to school with a knife or gun and kills someone? Today all this student frustration is bottled up and hidden and when it explodes, it’s deadly. My own angry outbursts were essentially harmless. No one actually got hurt, no matter how awful it sounded. I didn’t feel the need or desire to shoot or stab people.

One of you asked about Little Bear, and why she does not have a bigger part in the book. When I wrote Look Me in the Eye, we had been divorced a number of years, and I guess that’s the reason. If you wonder what happened, she reappears in Raising Cubby – the story of raising our son – and in Switched On – the story of my experiments with brain stimulation.

A few of you asked about drugs and drinking – how did I avoid that, on the road with rock and roll bands? Some of you mentioned peer pressure. As an autistic person, I was pretty oblivious to a lot of what went on around me, so I was probably not as sensitive to peer pressure as some of you. Also, I did drink and do drugs that were set in front of me. I’d sample what was being passed around. But I would not keep at it, night after night, getting hammered like others I saw. My violent drunk father put me off of that I guess. I didn’t buy drugs or drink when I was not on the road.

I guess I had enough trouble understanding the social dynamics around me without adding the complication of being a drunk or high fool also. As I got older, my interest just dissipated. When I stopped going on the road, I pretty much stopped all that too. Beyond that I really don’t know why I ended up drug and drink free, when so many others (including my own family) wrestle with addiction. My parents, brother, cousins, and grandfathers all had substance abuse troubles, so I must have the genes. Watching them – especially when I was a kid – may have scared me off.

Several of you commented on Asperger’s, autism, and how those are part of my adult sense of identity. You rightly observed that I grew up without any knowledge of autism, but I certainly knew I was different. Other kids had friends, other kids were invited to join teams and groups, other kids were popular and I wasn’t. What could a kid in that position conclude, except that they were defective; not as good as the others?

That was what I heard, in all the pronouncements that I’d never amount to anything. But it had kind of an opposite effect. People must have said, “you’d be successful if you’d just act right,” a thousand times. I heard, “You’d do really well if you put your mind to it.” Everyone ascribed my troubles to behaviors they assumed I could change, so in that telling, becoming successful was within my grasp.

And that is indeed what happened. I taught myself electronics and became a successful engineer, and then I taught myself about cars and became successful with them, and then I took up writing and that was a success too. It’s not that my life was all success – I had many failures on the way – but I was persistent both because I wanted to show my critics, and because I assumed it was “succeed or starve.” No one else was taking care of me.

What if I’d known I was autistic from age 5? What if people had whispered how I’d be in special ed, how I probably wouldn’t be able to live on my own, how I’d probably never get a good job or marry? That is what many kids hear today about autism. There is a benefit to having a non-judgmental explanation for how we are different, but an autism diagnosis comes with a very low set of life expectations, at least on the part of many teachers and parents. If I had been told my future was turning 18 and filing for social security disability, would I have been driven to do any of the things I did?

When I was a teenager I began gravitating toward places freaks and geeks hung out. Those included the science fiction society, the technology center, and the engineering lab at the local university. I am still friends with some of the kids I met there. What’s amazing is how many of us turned out to be on the autism spectrum or have kids who are autistic.

That shows how I was able to find others like me, even before I know about autism. Now it’s way easier to find similar autistic people. We’re forming communities online and in real life. We even have a word and movement: neurodiversity.

Some of you will make autism or other neurological difference part of your identity. When that happens, you are embracing neurodiversity – neurological diversity. Autism, ADHD, and other neurological differences are labels a doctor or psychologist gave you. Medical terms. Neurodiversity is the concept that those things are more than medical problems. Some degree of neurological diversity is a healthy thing and contributes to human diversity. Neurodiversity is our word – those of us who are neurodivergent. We wear that badge with pride, which is a great alternative to the shame surrounding the medical labels we had before.

As high school students you might wonder what comes next. For students who want to go to college, but need some help getting ready, Landmark College is the first neurodiversity college in the country. All the students at Landmark are neurodivergent, and proud of it. From there it’s a short step to regular colleges that embrace neurodiversity. I’m the Neurodiversity Scholar at William & Mary, one of the top public universities in America. I’ve advised neurodiversity programs at Drexel, Carnegie Mellon, UMass, and other schools, all of whom are proud of their neurodiversity initiatives.

When you look for work you’re going to see a different landscape. Companies from SAP to Microsoft to Home Depot to CVS are embracing neurodivergent people, under the moniker of Autism at Work. Autistic people with greater challenges are supported by programs like Project Search. That’s wonderful to see.

There has never been a better time to be different.

(c) 2019 John Elder Robison

John Elder Robison is an autistic adult and advocate for people with neurological differences. He's the author of Look Me in the Eye, Be Different, Raising Cubby, and Switched On. He serves on the Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee of the US Dept of Health and Human Services and many other autism-related boards. He co-founded the TCS Auto Program (A school for teens with developmental challenges) and he’s the Neurodiversity Scholar in Residence at the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia and an advisor to the Neurodiversity Institute at Landmark College in Putney, Vermont.

The opinions expressed here are his own. There is no warranty expressed or implied. While reading this essay will give you food for thought, actually printing and eating it may make you sick. (c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

Published on February 25, 2019 10:39

November 18, 2018

Neurodiversity and Relationships

Humans seek relationships for all sorts of reasons: protection and mutual aid, employment, friendship, romance . . . It should not surprise anyone to read that people like to be with others who are like them. There are a million ways to define “like themselves,” and it may not even be a conscious choice, but there is no doubt that many communities of like-minded people exist, just as many like-minded people become friends or romantic partners.

Evolutionary psychologists have a term for that: Assortative Mating.

Said that way, you might think people primarily pair off with others like them for romance, but in fact people connect with “folks like them” for most all relationships in life. In the case of neurodivergent people, a recent Swedish study supports the assortative mating theory:

In that study, researchers found an autistic person was 11 times more like to marry another autistic person than average. They were also more likely to marry a person with ADHD schizophrenia or bipolar diagnosis. In that study, neurodiversity marries neurodiversity.https://www.spectrumnews.org/news/people-with-autism-prefer-partners-on-the-spectrum/

Anecdotally, it appears many who are diagnosed on the autism spectrum in adulthood discover many of their old friends are autistic too. I’ve written about that in my books. It’s not unusual for an adult to have 5-10 adult friends who turn out to be on the spectrum. How does that happen, given ignorance of neurodiversity at the time of becoming friends? If it was just chance, a person’s circle of acquaintances would have to be 50 times the number of autistic friends they have, and that’s rarely the case. That’s an illustration of “assortative mating” matching up non romantic friends.

How does it work?· Does assortative mating work at a subconscious level?· How do we select friends?· How do we select people for other relationships, if we select at all?

Being different has a huge impact on one’s relationship skills/success, as in these accounts of women discovering their neurodiversity:https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/resources/idt-sh/women_late_diagnosis_autism

People often try to hide their differences in hope of fitting in. In the neurodiversity community that’s called masking. Here’s an account of its effect:https://www.spectrumnews.org/features/deep-dive/costs-camouflaging-autism/

Questions for the class:

What are some psychological consequences of an inability to form or sustain relationships?

How do those consequences match the psychological challenges common among neurodivergent people (from earlier class discussions)?

In previous neurodiversity classes we talked about neurodivergent people’s often-diminished ability to read body language, understand subtle cues in language, or respond in expected ways in social settings. While those challenges are real, they are not exclusive to neurodivergent people. Who else has similar challenges?1. People from foreign countries who don’t speak the local language?2. People from cultures whose behavioral norms are unacceptable in a different culture?3. Blind people, and individuals with some other perceptual disabilities?4. Other groups?

Is the diminished ability to read others, etc., a “neurodivergent reading neurotypical” issue, or is it a “neurodivergent reading anyone else” issue? In other words, is this a universal disability, or a mismatch between neurotypes?

There is no doubt neurodivergent people have more challenges with relationships than neurotypical people, as a group. But are the challenges unique, or a microcosm of what every human faces at some level?

What do we do about difficulty forming relationships? Mutual support – often from online communities – is helpful. Therapies like PEERS are emerging. Are they just for the neurodivergent, or for anyone? Read and consider . .

https://www.semel.ucla.edu/peers

(c) 2018 John Elder Robison

John Elder Robison is an autistic adult and advocate for people with neurological differences. He's the author of Look Me in the Eye, Be Different, Raising Cubby, and Switched On. He serves on the Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee of the US Dept of Health and Human Services and many other autism-related boards. He's co-founder of the TCS Auto Program (A school for teens with developmental challenges) and he’s the Neurodiversity Scholar in Residence at the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia and an advisor to the Neurodiversity Institute at Landmark College in Putney, Vermont.

The opinions expressed here are his own. There is no warranty expressed or implied. While reading this essay will give you food for thought, actually printing and eating it may make you sick.

(c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

Published on November 18, 2018 16:44

October 2, 2018

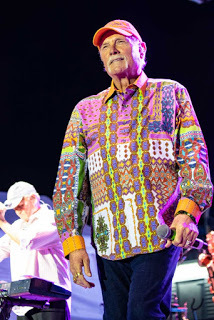

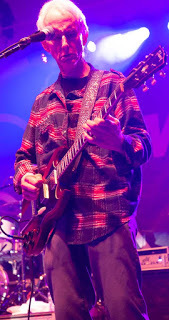

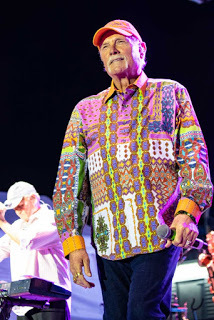

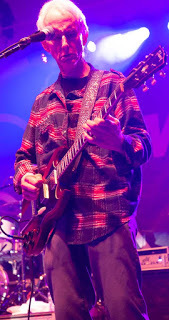

Images of the Big E 2018 - Concert and Performance Photography

For 20 years I have had the pleasure of photographing the entertainment at New England’s largest fair, the Eastern States Exposition in West Springfield, MA. With over 1,500,000 people passing through the gates over its 17-day run The Big E is one of the largest fairs in North America and by far the biggest draw in New England.

The Beach Boys play for a packed house on closing night, October 30, 2018

The Beach Boys play for a packed house on closing night, October 30, 2018

Over the years I’ve developed what I suppose is a distinct style of photography, and the managers, promoters, musicians and other performers have welcomed it, and invited me onto their stages, into the back rooms, and wherever else I cared to venture in search of the winning image.

In this blog I’ve shown many of the performers who graced the stages at this year’s (2018) fair. If you performed at the fair and don’t see yourself or your group, I apologize as there were some I inevitably missed due to time conflicts and just sheer numbers.

The pictures you will see were taken with Nikon D5 and D4S system cameras. Most of the photos were shot through a Nikon 80-400 lens with image stabilization. All are hand-held, and no flash or other supplemental light was used. None of these shots are posed. All the performers were shot while performing their acts. There are no rehearsals for this kind of picture taking. You put in your earplugs, pick up the camera, and go do it.

Most images were shot at night under stage lighting, using ISO sensitivities of 1000-12000. It is amazing how good the images are for a speed that would have been almost unattainable 10 years ago. Shutter speeds range from 1/80 to 1/250 of a second, with most shots being 1/100 or so. That allows enough motion blur to make the performers look alive, but not so much as to make the whole shot blurry.

The challenge with taking pictures like this is to see the image, compose and focus in the brief milliseconds that the possible picture exists. Since the performers are in constant motion you have to decide to shoot or not very fast, and you need a camera that can keep up. With the exception of the flying trapeze act (which happens too fast to see) all these pictures were taken in single shot mode. Each one represents a deliberate choice; not a lucky accident of timing.

Another thing you need for good performance images is proximity. I'm lucky to be offered special access because people like the resultant images. In the world of autism advocacy my books speak for me, to positive effect. In the music and circus worlds, I'm proud to see my imagery has done the same. In most cases I shot these performers at distances under fifteen feet. Many were shot at six feet and some even closer. To get that close I had to creep onto or beside the stages, and into areas where audiences never go. Interestingly, it’s the photos from those places that audiences look at and say, “Yeah, that is just how I remember it.” It seems the closer I get, and the more surreal the composition or exposure, the more real it feels to many people.

This is an example of proximity and what it means. For the photo below I stood three feet from funk drummer Jellybean Johnson, and shot this image from a perspective few people see firsthand. Yet it's this image that people say looks real to them. That shows how our imagination often means more to memory than what we actually saw, when it comes to emotional things like music.

I thank everyone in these shots for welcoming me onto their stages and into their performances, and the promoters and managers for bringing me onto the grounds. In every case they know I’m there and I sometimes feel we are in a dance – performer and I – looking at each other, looking away, both of us moving, waiting for that perfect moment. Sometimes people ask me how the music was, and the answer is . . . I don’t know. When I concentrate to take the photos I don’t really hear the music. I feel it, but I can’t recall it to you later. Others ask what kind of music is my favorite, and the truth is, I live turning all of it into imagery. I don’t really care what they play; it’s magic when it works.

John Elder Robison

Alyssa and Ruby of Sisterhood

Tom Dobson

Raelynn, famous for That's Why God Made Girls

Noah Cyrus

Country star Chase Bryant

Cathy Richardson, of Jefferson Starship

Mike Love of The Beach Boys

The King Charles Troupe - basketball on unicycles in the middle of the circus

The Mardi Gras Parade

Jacob Sartorious

The King Charles Troupe, the first all-black Barnum and Bailey act from 1954

Trent Harmon

Robby Krieger of The Doors

Eliot Sloan of Blessid Union of Souls

Marcus James Henderson and Chris Hicks of The Marshall Tucker Band

Matthew Ramsey of Old Dominion

Melody DeVevo of Casting Crowns

Morris Day of M.D. and the Time

Tony Orlando, famous for Tie a Yellow Ribbon, Knock Three Times, Candida and more

Circus star Bello Nock

The Voice, performed live on the Big E stage

Tito Jackson

Ice T

Terry Adams of NRBQ

The Drifters, who I first saw when working Studio Instrument Rentals in NY in the 70s

The Platters

The Beatles Tribute

And the Official Blues Brothers Band

War

Jenny Tolman, up from Nashville for a single show

Hanson

Reel Big Fish

Reel Big Fish

(c) John Elder Robison

John Elder Robison is an autistic adult and advocate for people with neurological differences. He's the author of Look Me in the Eye, Be Different, Raising Cubby, and Switched On. He serves on the Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee of the US Dept of Health and Human Services and many other autism-related boards. He's co-founder of the TCS Auto Program (A school for teens with developmental challenges) and he’s the Neurodiversity Scholar in Residence at the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia and an advisor to the Neurodiversity Institute at Landmark College in Putney, Vermont.

The opinions expressed here are his own. There is no warranty expressed or implied. While reading this essay will give you food for thought, actually printing and eating it may make you sick.

(c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

The Beach Boys play for a packed house on closing night, October 30, 2018

The Beach Boys play for a packed house on closing night, October 30, 2018Over the years I’ve developed what I suppose is a distinct style of photography, and the managers, promoters, musicians and other performers have welcomed it, and invited me onto their stages, into the back rooms, and wherever else I cared to venture in search of the winning image.

In this blog I’ve shown many of the performers who graced the stages at this year’s (2018) fair. If you performed at the fair and don’t see yourself or your group, I apologize as there were some I inevitably missed due to time conflicts and just sheer numbers.

The pictures you will see were taken with Nikon D5 and D4S system cameras. Most of the photos were shot through a Nikon 80-400 lens with image stabilization. All are hand-held, and no flash or other supplemental light was used. None of these shots are posed. All the performers were shot while performing their acts. There are no rehearsals for this kind of picture taking. You put in your earplugs, pick up the camera, and go do it.

Most images were shot at night under stage lighting, using ISO sensitivities of 1000-12000. It is amazing how good the images are for a speed that would have been almost unattainable 10 years ago. Shutter speeds range from 1/80 to 1/250 of a second, with most shots being 1/100 or so. That allows enough motion blur to make the performers look alive, but not so much as to make the whole shot blurry.

The challenge with taking pictures like this is to see the image, compose and focus in the brief milliseconds that the possible picture exists. Since the performers are in constant motion you have to decide to shoot or not very fast, and you need a camera that can keep up. With the exception of the flying trapeze act (which happens too fast to see) all these pictures were taken in single shot mode. Each one represents a deliberate choice; not a lucky accident of timing.

Another thing you need for good performance images is proximity. I'm lucky to be offered special access because people like the resultant images. In the world of autism advocacy my books speak for me, to positive effect. In the music and circus worlds, I'm proud to see my imagery has done the same. In most cases I shot these performers at distances under fifteen feet. Many were shot at six feet and some even closer. To get that close I had to creep onto or beside the stages, and into areas where audiences never go. Interestingly, it’s the photos from those places that audiences look at and say, “Yeah, that is just how I remember it.” It seems the closer I get, and the more surreal the composition or exposure, the more real it feels to many people.

This is an example of proximity and what it means. For the photo below I stood three feet from funk drummer Jellybean Johnson, and shot this image from a perspective few people see firsthand. Yet it's this image that people say looks real to them. That shows how our imagination often means more to memory than what we actually saw, when it comes to emotional things like music.

I thank everyone in these shots for welcoming me onto their stages and into their performances, and the promoters and managers for bringing me onto the grounds. In every case they know I’m there and I sometimes feel we are in a dance – performer and I – looking at each other, looking away, both of us moving, waiting for that perfect moment. Sometimes people ask me how the music was, and the answer is . . . I don’t know. When I concentrate to take the photos I don’t really hear the music. I feel it, but I can’t recall it to you later. Others ask what kind of music is my favorite, and the truth is, I live turning all of it into imagery. I don’t really care what they play; it’s magic when it works.

John Elder Robison

Alyssa and Ruby of Sisterhood

Tom Dobson

Raelynn, famous for That's Why God Made Girls

Noah Cyrus

Country star Chase Bryant

Cathy Richardson, of Jefferson Starship

Mike Love of The Beach Boys

The King Charles Troupe - basketball on unicycles in the middle of the circus

The Mardi Gras Parade

Jacob Sartorious

The King Charles Troupe, the first all-black Barnum and Bailey act from 1954

Trent Harmon

Robby Krieger of The Doors

Eliot Sloan of Blessid Union of Souls

Marcus James Henderson and Chris Hicks of The Marshall Tucker Band

Matthew Ramsey of Old Dominion

Melody DeVevo of Casting Crowns

Morris Day of M.D. and the Time

Tony Orlando, famous for Tie a Yellow Ribbon, Knock Three Times, Candida and more

Circus star Bello Nock

The Voice, performed live on the Big E stage

Tito Jackson

Ice T

Terry Adams of NRBQ

The Drifters, who I first saw when working Studio Instrument Rentals in NY in the 70s

The Platters

The Beatles Tribute

And the Official Blues Brothers Band

War

Jenny Tolman, up from Nashville for a single show

Hanson

Reel Big Fish

Reel Big Fish(c) John Elder Robison

John Elder Robison is an autistic adult and advocate for people with neurological differences. He's the author of Look Me in the Eye, Be Different, Raising Cubby, and Switched On. He serves on the Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee of the US Dept of Health and Human Services and many other autism-related boards. He's co-founder of the TCS Auto Program (A school for teens with developmental challenges) and he’s the Neurodiversity Scholar in Residence at the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia and an advisor to the Neurodiversity Institute at Landmark College in Putney, Vermont.

The opinions expressed here are his own. There is no warranty expressed or implied. While reading this essay will give you food for thought, actually printing and eating it may make you sick.

(c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

Published on October 02, 2018 19:05

August 19, 2018

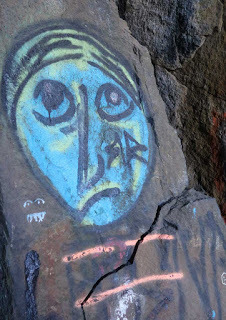

Petroglyphs, Graffiti, and the inscrutability of public art

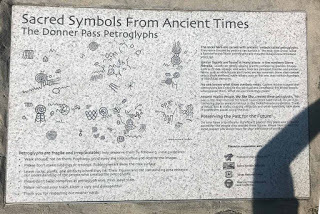

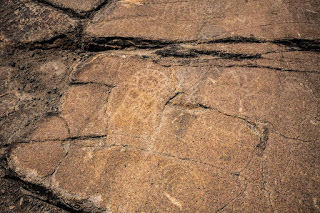

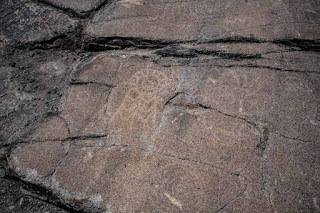

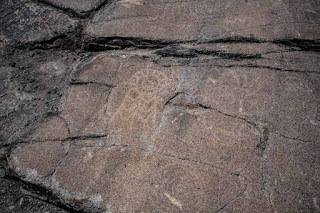

Donner Pass, a few miles west of Truckee, California, contains an area of well-preserved Indian petroglyphs. Petroglyphs are carved art created by cutting into the surface of rock. Archaeologists have found petroglyphs in many remote areas of the Sierra, often in places like the flat granite at Donner summit. This pass has been a trade route for a long time; the petroglyphs are thought to be two to three thousand years old.

Petroglyph at Donner Pass (c) John Robison 2018The marker at the Donner petroglyphs is titled, “Sacred Symbols from Ancient Times,” but I’m not sure what evidence we have that the carvings were sacred beyond modern interpretation. We know very little about the context of these artworks. Were they trailside art that early people walked past as they followed a track over the mountain? Or were they carved in a special place, off the main trail?

Petroglyph at Donner Pass (c) John Robison 2018The marker at the Donner petroglyphs is titled, “Sacred Symbols from Ancient Times,” but I’m not sure what evidence we have that the carvings were sacred beyond modern interpretation. We know very little about the context of these artworks. Were they trailside art that early people walked past as they followed a track over the mountain? Or were they carved in a special place, off the main trail?

Back in the day, the petroglyphs may have been painted or enhanced to be more visible.

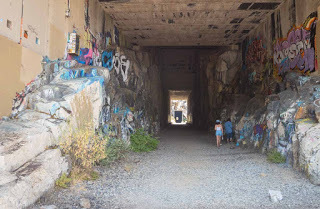

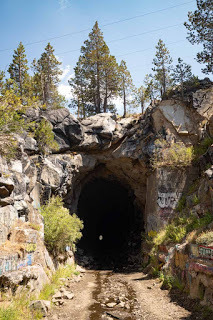

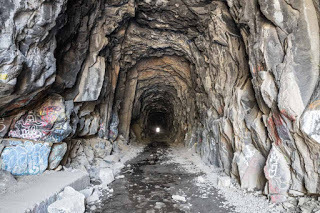

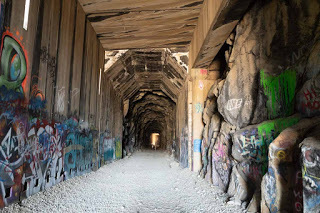

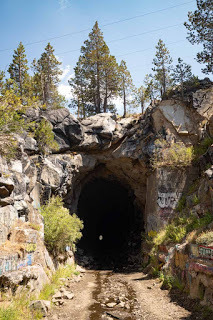

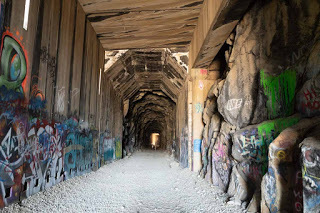

A few hundred yards uphill you can see the tunnels that carried the first transcontinental railroad over the Sierra. The tunnels were cut in the 1860s, and augmented by wooden snow sheds to shelter the tracks from snow. The wooden sheds were vulnerable to fire and avalanche, and they were replaced by concrete structures in the 1950s.

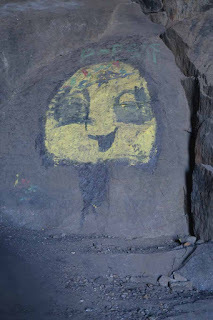

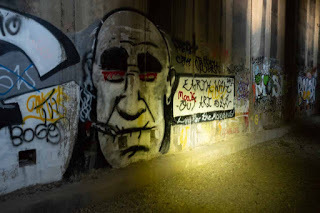

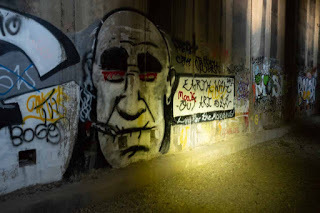

Donner Pass - petroglyphs on flat granite in foreground, tunnels and snow sheds above and behindWalking into the train tunnels the first thing you see is the art adorning the walls. The tunnels are protected from rain and snow, and they provide miles and miles of concrete and stone canvas for today’s artists. Are those sacred art?

Donner Pass - petroglyphs on flat granite in foreground, tunnels and snow sheds above and behindWalking into the train tunnels the first thing you see is the art adorning the walls. The tunnels are protected from rain and snow, and they provide miles and miles of concrete and stone canvas for today’s artists. Are those sacred art?

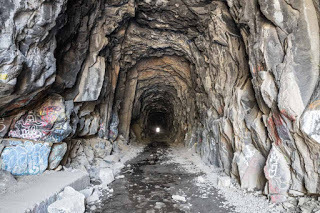

In many places, in the tunnels, quality artworks lie next to or even underneath rougher drawings, symbols, and written messages. What are the messages in the modern art? As with the petroglyphs, no one knows.

When we call outdoor art graffiti we often use the term as if it’s not art at all. Graffiti is to many a form of vandalism. Some who paint it may think that way, but others see it as a serious form of art, and they see themselves as serious artists. In some cases graffiti artists explain the thinking behind their creations but more often they are anonymous, and the view is left to draw his or her own conclusions.

It’s reasonable to think that much wall art is serious, and sacred might be a proper term for some of it. Other wall paintings are malicious; slashing or covering earlier works out of jealously, anger, or emotions we cannot fathom. Some is whimsical or notational, like“Kilroy was here, 2015,” and its like.

In cities some street art contains gang symbols and messages. Art that appears inscrutable to the general public (myself included) may have a clear meaning to a smaller group of initiated. Something similar may have been the case when the petroglyphs were carved, too.

Gangs over-write each other's symbols, but that is far from the only reason people write over existing art. Some simply want space for their creation. Others are jealous. Some of the notion of cleaning up "non-approved" art with something else. If we cannot understand the dynamics of graffiti now, how can we possibly understand the dynamics of 2,000BC?

Most of the modern day tunnel art will be gone 2,000 years from now, but some will probably survive. When the petroglyphs are contrasted with the graffiti of today – lining a modern railroad trade route – we may wonder if they were the outdoor art of that era, lining the trade paths of that day. Perhaps what we see is just a fraction of what was once there, and the reason the symbols seem jumbled and indecipherable is that the art was created by many people with many goals and intentions, and there was no coherent meaning.

We tend to interpret arrays of art (petroglyphs) or arrays of ruins (towns) as if there was a common purpose or an overall guiding theme. As today’s graffiti makes clear, that is not always the case today and there’s no reason to think the street art of times past was any different.

If an archaeologist of the future were to try and understand our civilization from the symbols in the Donner Pass tunnels, what would they conclude? The train tracks have been removed from the tunnels, so their overall purpose might not be apparent to a later observer. Would a future archaeologist assume a purposeful relationship between the tunnel and the paintings?

Recently some scientists have looked at the style of cave paintings in Europe and suggested the artists may have been autistic. We could ask the same about today’s graffiti artists. How many of them may be autistic? The scientists found parallels between some cave art and the drawings style of known autistic artists today. The same parallels may be found in contemporary graffiti, just as other graffiti is of different style.

It’s interesting to think that autistic people may have been creating art for tens of thousands of years. And non-autistic people have been doing it just as long. Looking at the jumble of styles on Donner Pass today it’s clear the two groups co-exist now, and the evidence of European caves suggest the same situation prevailed in the distant past.

If today’s graffiti art is anonymous, yesterdays is even more so. In some cases, modern art comes with readable messages, but all too often its meaning is in the mind of the viewer, and we can never know if our interpretation bears any similarity to what was in the creator’s mind.

Some things can never be understood.

(c) 2018 John Elder Robison

John Elder Robison is an autistic adult and advocate for people with neurological differences. He's the author of Look Me in the Eye, Be Different, Raising Cubby, and Switched On. He serves on the Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee of the US Dept of Health and Human Services and many other autism-related boards. He's co-founder of the TCS Auto Program (A school for teens with developmental challenges) and he’s the Neurodiversity Scholar in Residence at the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia and an advisor to the Neurodiversity Institute at Landmark College in Putney, Vermont.

The opinions expressed here are his own. There is no warranty expressed or implied. While reading this essay will give you food for thought, actually printing and eating it may make you sick.

(c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

Published on August 19, 2018 18:19

August 16, 2018

Crossing the Sierra on the Way to the Pacific

Headed west through Truckee, California, the road starts climbing as you approach Donner Pass. For thousands of years Indians used this route to journey from the inland plains to the Pacific coast. Today we see their legacy in petroglyphs on the flat hard granite just below the summit. These carvings are thought to be two to three thousand years old, but no one really knows.

Some symbols are suggestive, but their precise meaning isn’t known either. The marks are cut on a gently sloping stone plain. I've got a separate essay on them here, if you are curious.

Petroglyphs are visible beyond this marker at Donner Summit

Petroglyphs are visible beyond this marker at Donner Summit

In 1844 the Stephens-Townsend-Murphy party followed the old Indian trail past present-day Donner Lake and over the pass, becoming the first settlers to use the route. In the fall of 1846 the ill-fated Donner party tried to do the same, but early snows blocked them at Donner Lake. Half the group starved and the survivors resorted to cannibalism, giving the lake and pass the name it’s known by today.

Donner Lake seen from the pass. The Central Pacific (now UP) rail line clings to the slope on the rightOver the next 20 years thousands of settlers used Donner Pass to reach the promised lands of California. The granite was rough and unforgiving, forcing settlers to dismantle their wagons and haul them over rocks, with many losing their belongings and even limbs or lives in the process.

Donner Lake seen from the pass. The Central Pacific (now UP) rail line clings to the slope on the rightOver the next 20 years thousands of settlers used Donner Pass to reach the promised lands of California. The granite was rough and unforgiving, forcing settlers to dismantle their wagons and haul them over rocks, with many losing their belongings and even limbs or lives in the process.

When talk of a transcontinental rail link materialized, the route was surveyed through Donner Pass. Trains need a constant gentle slope, without up and down, so the route they chose was a bit south of the footpath and wagon road. The two paths do remain in sight of each other across the pass. The trail goes up and down over terrain to follow the most direct route. The rail line is cut at a constant angle into the sides of the mountains, clinging to them like a pasted-on stripe.

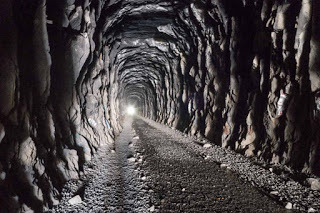

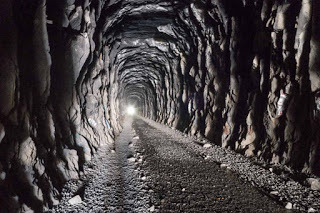

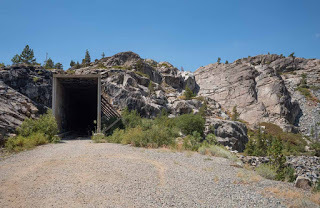

In the spring of 1868 the Central Pacific Railroad completed the laying of track over the pass. It took a crew of mostly Chinese laborers five years to cross the mountains, with numerous tunnels and cuts. The longest is tunnel #6, at 1,659 feet.

These tunnels were dug entirely by hand, with some assistance from draft animals and explosives. Thousands of laborers died in the building of the line, with most unknown today. The rough hacked appearance of the tunnels make a sharp contrast to the finished highway tunnels we pass through today.

Even at the height of summer tunnel 6 is dark and cold. Light barely penetrates the quarter-mile to the center; the photos above were made with the help of some scattered sunlight, my own miner's headlamp, and a Leica M10 camera at ISO 50,000 - almost seeing in the dark.

The shorter tunnels are not as cold, but there is still an eerie feeling inside them. It's easy to imagine the ghosts of the Chinese laborers, and the many railroaders who lost their lives on this pass.

The builders of the railroad also built a wagon road to bring up workers and supplies from Truckee. In 1914 that construction road was rebuilt as the Lincoln Highway, the nation’s first transcontinental auto road. Vestiges of the Lincoln Highway are visible through the pass today, including this overpass that carried the road under the rail grade before the summit tunnel. Compared to overpasses today this one looks tiny, but the biggest thing that went under it back then was a Ford Model T.

In the photo above a mother and child stand in front of a Lincoln Highway underpass. This road has vanished today but portions still carry modern data cables as evidenced by the yellow warning post.

Railroad engineers had assumed they could keep the rail line open through winter storms by running plows back and forth. They did not foresee the amount of snow that would fall. Donner pass usually sees thirty feet of snow, and sometimes twice that. Snow lingers on the mountainside well into summer. Not only did the snow bury the lines, avalanches swept the threads of track into the valleys below, sometimes taking trains and passengers with them.The answer was snow sheds, miles of structures that protected the tracks from snow and hopefully allowed avalanches to pass over harmlessly. By the early 20thcentury the original wood snow sheds had been replaced with concrete, anchored to the mountainside with heavy steel rods and girders.

In many places the railroad appears to cling to sheer cliffs, and inside the snowsheds that is evident with rock wall on one side and concrete on the other.

The image above shows a snow shed from outside. The image below is the same shed, inside. Light streams in through the slits in the walls, which are enough to give weak illumination without filling the shed with snow.

Outside the concrete is a few feet of flat ground and then a drop of one thousand feet or more into the valley. The rail line climbs to 7,100 feet at the top of the pass. The edge is visible in the photo below:

Another interesting feature is the Chinese wall, so named for the laborers who built it, with stone alone. This structure carries the rail line across a dip in the contours. There is no mortar in the main embankment, which carried increasingly heavy train traffic for 100+ years. There is post-construction mortar in the upper retaining wall; both are impressive examples of stonework. They are built from granite cut for the tunnel bores.

This retaining wall held back winter avalanches and supported massive freight trains for 130 years, just as the original Chinese stone masons built it.

This is the hiking trail down from the Chinese wall. This is probably not much different from the path the Indians and original emigrants trod:

Here is another filled embankment. You can see a snow shed entrance at the upper right. The slope is all fill, carrying the railroad over the low spot. Huge amounts of fill were required in areas like this to prevent being washed out in floods or avalanches.

In this next two images you can see a smaller rock wall. This is a built up section of the construction service road, which later became the Lincoln Highway for early motorcars.

This view looks up at the Chinese walls. The trees give a sense of scale

In 1993 the Union Pacific abandoned the six mile section at the top of Donner Pass in favor of a newer three mile tunnel through adjacent Mt. Judah that carries the rails under the worst of the summit conditions. The photo below looks west, shortly after the rails emerge from the Mt. Judah tunnel:

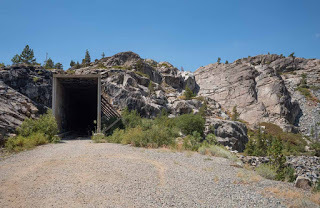

Since then the abandoned tunnels have become a destination for hikers. They are also a destination for urban artists, few of whom braved the threats of trains and railroad police before the tracks were taken up. The tunnels today have an eerie feel, even looking in from outside.

The tunnels are filled with graffiti:

In the photo below I am walking through a snow shed, which transitions to a tunnel a short distance ahead. The light at the end is the sun illuminating the exit, and not an oncoming locomotive.

More graffiti:

This image shows how massive the tunnel construction has to be, to survive the onslaught of winter snow and slides:

A shaft of sunlight streams in through an opening in the wall. The people in the image give a sense of scale. Look at the size of the concrete columns that reinforce the roof. That is necessary in areas that may be hit with avalanches. Why the height, you ask? In olden days the tunnels needed to be tall to hold and diffuse the steam locomotive smoke. Today they need height to accommodate double stack containers, such as these cars headed west through Truckee:

If you want to see this for yourself take the Donner Pass Road west from Truckee. There are exits for the road on I-80. Climb to the overlook bridge parking area and walk across the road and downhill a few hundred yards to the trail up to the petroglyphs. From there the trail goes up to the Chinese walls between two of the tunnels. Tunnel six will be on your right, to the west.

The images in this essay were taken with a Leica M10 camera and a Leica 28 2.8 lens. All images were shot hand held at shutter speeds ranging from 1/500 to 1/2 second. The rangefinder system has an advantage focusing in the dark, compared to more automated cameras where focus would tend to hunt or be wrong. The M10 finally gives Leica a body whose sensor really performs to the level set by cameras like the Nikon D5 SLR. Leica lenses have always been superlative, and their manual nature forces the photographer to think more before each shot.

I certainly could have taken these shots with a D5, but doing so would have required a tripod and it would have been a much bigger production to get it up there. Smaller point and shoot camera could not have delivered the results of the M10 in the tunnels, though they would have been competitive outside. Photographers always have to trade quality against size and portability.

When photographing landscapes like these I like the slow reflective nature of the Leica camera, combined with the top-shelf image quality.

(c) 2018 John Elder Robison

(c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

Some symbols are suggestive, but their precise meaning isn’t known either. The marks are cut on a gently sloping stone plain. I've got a separate essay on them here, if you are curious.

Petroglyphs are visible beyond this marker at Donner Summit

Petroglyphs are visible beyond this marker at Donner Summit

In 1844 the Stephens-Townsend-Murphy party followed the old Indian trail past present-day Donner Lake and over the pass, becoming the first settlers to use the route. In the fall of 1846 the ill-fated Donner party tried to do the same, but early snows blocked them at Donner Lake. Half the group starved and the survivors resorted to cannibalism, giving the lake and pass the name it’s known by today.

Donner Lake seen from the pass. The Central Pacific (now UP) rail line clings to the slope on the rightOver the next 20 years thousands of settlers used Donner Pass to reach the promised lands of California. The granite was rough and unforgiving, forcing settlers to dismantle their wagons and haul them over rocks, with many losing their belongings and even limbs or lives in the process.

Donner Lake seen from the pass. The Central Pacific (now UP) rail line clings to the slope on the rightOver the next 20 years thousands of settlers used Donner Pass to reach the promised lands of California. The granite was rough and unforgiving, forcing settlers to dismantle their wagons and haul them over rocks, with many losing their belongings and even limbs or lives in the process.When talk of a transcontinental rail link materialized, the route was surveyed through Donner Pass. Trains need a constant gentle slope, without up and down, so the route they chose was a bit south of the footpath and wagon road. The two paths do remain in sight of each other across the pass. The trail goes up and down over terrain to follow the most direct route. The rail line is cut at a constant angle into the sides of the mountains, clinging to them like a pasted-on stripe.

In the spring of 1868 the Central Pacific Railroad completed the laying of track over the pass. It took a crew of mostly Chinese laborers five years to cross the mountains, with numerous tunnels and cuts. The longest is tunnel #6, at 1,659 feet.

These tunnels were dug entirely by hand, with some assistance from draft animals and explosives. Thousands of laborers died in the building of the line, with most unknown today. The rough hacked appearance of the tunnels make a sharp contrast to the finished highway tunnels we pass through today.

Even at the height of summer tunnel 6 is dark and cold. Light barely penetrates the quarter-mile to the center; the photos above were made with the help of some scattered sunlight, my own miner's headlamp, and a Leica M10 camera at ISO 50,000 - almost seeing in the dark.

The shorter tunnels are not as cold, but there is still an eerie feeling inside them. It's easy to imagine the ghosts of the Chinese laborers, and the many railroaders who lost their lives on this pass.

The builders of the railroad also built a wagon road to bring up workers and supplies from Truckee. In 1914 that construction road was rebuilt as the Lincoln Highway, the nation’s first transcontinental auto road. Vestiges of the Lincoln Highway are visible through the pass today, including this overpass that carried the road under the rail grade before the summit tunnel. Compared to overpasses today this one looks tiny, but the biggest thing that went under it back then was a Ford Model T.

In the photo above a mother and child stand in front of a Lincoln Highway underpass. This road has vanished today but portions still carry modern data cables as evidenced by the yellow warning post.

Railroad engineers had assumed they could keep the rail line open through winter storms by running plows back and forth. They did not foresee the amount of snow that would fall. Donner pass usually sees thirty feet of snow, and sometimes twice that. Snow lingers on the mountainside well into summer. Not only did the snow bury the lines, avalanches swept the threads of track into the valleys below, sometimes taking trains and passengers with them.The answer was snow sheds, miles of structures that protected the tracks from snow and hopefully allowed avalanches to pass over harmlessly. By the early 20thcentury the original wood snow sheds had been replaced with concrete, anchored to the mountainside with heavy steel rods and girders.

In many places the railroad appears to cling to sheer cliffs, and inside the snowsheds that is evident with rock wall on one side and concrete on the other.

The image above shows a snow shed from outside. The image below is the same shed, inside. Light streams in through the slits in the walls, which are enough to give weak illumination without filling the shed with snow.

Outside the concrete is a few feet of flat ground and then a drop of one thousand feet or more into the valley. The rail line climbs to 7,100 feet at the top of the pass. The edge is visible in the photo below:

Another interesting feature is the Chinese wall, so named for the laborers who built it, with stone alone. This structure carries the rail line across a dip in the contours. There is no mortar in the main embankment, which carried increasingly heavy train traffic for 100+ years. There is post-construction mortar in the upper retaining wall; both are impressive examples of stonework. They are built from granite cut for the tunnel bores.

This retaining wall held back winter avalanches and supported massive freight trains for 130 years, just as the original Chinese stone masons built it.

This is the hiking trail down from the Chinese wall. This is probably not much different from the path the Indians and original emigrants trod:

Here is another filled embankment. You can see a snow shed entrance at the upper right. The slope is all fill, carrying the railroad over the low spot. Huge amounts of fill were required in areas like this to prevent being washed out in floods or avalanches.

In this next two images you can see a smaller rock wall. This is a built up section of the construction service road, which later became the Lincoln Highway for early motorcars.

This view looks up at the Chinese walls. The trees give a sense of scale

In 1993 the Union Pacific abandoned the six mile section at the top of Donner Pass in favor of a newer three mile tunnel through adjacent Mt. Judah that carries the rails under the worst of the summit conditions. The photo below looks west, shortly after the rails emerge from the Mt. Judah tunnel:

Since then the abandoned tunnels have become a destination for hikers. They are also a destination for urban artists, few of whom braved the threats of trains and railroad police before the tracks were taken up. The tunnels today have an eerie feel, even looking in from outside.

The tunnels are filled with graffiti:

In the photo below I am walking through a snow shed, which transitions to a tunnel a short distance ahead. The light at the end is the sun illuminating the exit, and not an oncoming locomotive.

More graffiti:

This image shows how massive the tunnel construction has to be, to survive the onslaught of winter snow and slides:

A shaft of sunlight streams in through an opening in the wall. The people in the image give a sense of scale. Look at the size of the concrete columns that reinforce the roof. That is necessary in areas that may be hit with avalanches. Why the height, you ask? In olden days the tunnels needed to be tall to hold and diffuse the steam locomotive smoke. Today they need height to accommodate double stack containers, such as these cars headed west through Truckee:

If you want to see this for yourself take the Donner Pass Road west from Truckee. There are exits for the road on I-80. Climb to the overlook bridge parking area and walk across the road and downhill a few hundred yards to the trail up to the petroglyphs. From there the trail goes up to the Chinese walls between two of the tunnels. Tunnel six will be on your right, to the west.

The images in this essay were taken with a Leica M10 camera and a Leica 28 2.8 lens. All images were shot hand held at shutter speeds ranging from 1/500 to 1/2 second. The rangefinder system has an advantage focusing in the dark, compared to more automated cameras where focus would tend to hunt or be wrong. The M10 finally gives Leica a body whose sensor really performs to the level set by cameras like the Nikon D5 SLR. Leica lenses have always been superlative, and their manual nature forces the photographer to think more before each shot.

I certainly could have taken these shots with a D5, but doing so would have required a tripod and it would have been a much bigger production to get it up there. Smaller point and shoot camera could not have delivered the results of the M10 in the tunnels, though they would have been competitive outside. Photographers always have to trade quality against size and portability.

When photographing landscapes like these I like the slow reflective nature of the Leica camera, combined with the top-shelf image quality.

(c) 2018 John Elder Robison

(c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

Published on August 16, 2018 11:35

May 10, 2018

Thoughts from INSAR2018 Autism Science in Rotterdam

Every day of #INSAR2018 brings a new round of scientists presenting their research. They are sorted into rough categories with psychologists, social scientists, and anthropologists being among today’s presenters.

As an American I was pleased to see that the majority of research was not from America, or indeed from any one country. Great Britain is smaller than the USA but there were as many presenters from there today. There were also scientists from countries in Africa, Asia, and South America. The Australian contingent was there, as were the Russians.

When looking at posters from developing nations I noted they were all focused on parents. A poster might be titled “Life with Autism in . . .” and then the description says “Interviews with parents in . . . .”

As an autistic adult from a country where we have a #neurodiversity culture I found those posters (there were many of them with that format) troubling. I asked the researchers if they recognized that they were not studying life with autism, but rather parental interpretation of life with autism. Accurately studying life with autism means studying actual autistic people, not people who watch us.

Responses varied. The most common response was that the kids in the studies could not all be interviewed because they had limited language, were too young, etc. Some researchers said they would like to study actual autistics but did not know any older kids or adults. Some said autism was just getting recognized in their country, and they did not have any population of diagnosed adults to draw from.

It made me wonder if we could jump start the process of awareness and understanding but I don’t know if there is a way to do that(c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

Published on May 10, 2018 06:03

April 16, 2018

Neurodivergent People and the Law

Today we will look at how neurodivergent people come in contact with the legal systems in America. In this country individuals may engage with the civil or criminal courts, or both.

Neurodivergent people are more likely to be disabled – either visibly or invisibly – as compared to the general population. People with disabilities often seek legal assistance or protection. That is usually a civil matter. Examples may include:Getting a child evaluated for developmental disabilities, so that they can get services and supports in school.Once a student is evaluated and a plan in in place some school parents and school districts are unable to agree on the services needed or provided. In such cases parents may turn to attorneys for help.Adults who cannot access things or places may turn to government agencies and attorneys to interpret or enforce laws like the ADA.Adults may seek legal assistance with workplace accommodations or with workplace issues.Parents may seek guardianship for disabled children. Disabled people may challenge others’ guardianship over them.

Neurodivergent people are likely to act different from the average person particularly in stressful circumstances. This may be because they perceive situations differently, or because they respond differently, or because they don’t pick up messages that others receive, and therefore don’t respond at all.ND people are more likely to have trouble with police and first responders, by not answering questions, not answering as expected, or responding differently to being touched.ND people are more likely to be isolated, and may be more vulnerable to adopting fringe ideologies that can lead to societal conflicts.ND people are more likely to be poor and socially isolated. This translates to a lack of community support and greater vulnerability to interactions with law enforcement.Being neurodivergent magnifies an individual’s chances of mistreatment, particularly for members of marginalized groups.

Society has a duty to protect its members. However not everyone wants or needs the protection. Sometimes protecting us from one thing subjects us to harm from another. That makes for a difficult ethical landscape.

Some of the problems encountered by ND people can be resolved with the help of attorneys. Other problems are addressed by local courts. When a court decision seems unjust it may be reviewed by the Supreme Court, and our interpretation of the law may change. Elected officials may change or establish laws and regulations.

When laws and regulations change and evolve they affect all of us. (c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

Neurodivergent people are more likely to be disabled – either visibly or invisibly – as compared to the general population. People with disabilities often seek legal assistance or protection. That is usually a civil matter. Examples may include:Getting a child evaluated for developmental disabilities, so that they can get services and supports in school.Once a student is evaluated and a plan in in place some school parents and school districts are unable to agree on the services needed or provided. In such cases parents may turn to attorneys for help.Adults who cannot access things or places may turn to government agencies and attorneys to interpret or enforce laws like the ADA.Adults may seek legal assistance with workplace accommodations or with workplace issues.Parents may seek guardianship for disabled children. Disabled people may challenge others’ guardianship over them.

Neurodivergent people are likely to act different from the average person particularly in stressful circumstances. This may be because they perceive situations differently, or because they respond differently, or because they don’t pick up messages that others receive, and therefore don’t respond at all.ND people are more likely to have trouble with police and first responders, by not answering questions, not answering as expected, or responding differently to being touched.ND people are more likely to be isolated, and may be more vulnerable to adopting fringe ideologies that can lead to societal conflicts.ND people are more likely to be poor and socially isolated. This translates to a lack of community support and greater vulnerability to interactions with law enforcement.Being neurodivergent magnifies an individual’s chances of mistreatment, particularly for members of marginalized groups.

Society has a duty to protect its members. However not everyone wants or needs the protection. Sometimes protecting us from one thing subjects us to harm from another. That makes for a difficult ethical landscape.

Some of the problems encountered by ND people can be resolved with the help of attorneys. Other problems are addressed by local courts. When a court decision seems unjust it may be reviewed by the Supreme Court, and our interpretation of the law may change. Elected officials may change or establish laws and regulations.

When laws and regulations change and evolve they affect all of us. (c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

Published on April 16, 2018 10:35

April 13, 2018

Autism and Mercy in Capital Crimes

In the past decade autism has been diagnosed or suggested in a number of high profile spree killers. Most of the conversation to date has centered on three facts:

· People with autism are more likely to be victims than perpetrators of aggressive violence. · In many cases spree killers kill themselves, or are killed by police, and no official mental health diagnoses emerge. Suggestions of autism or anything else are therefore speculation which is rightly criticized as inflammatory;· Even when a credible diagnosis exists there is considerable dispute about any role autism may have played in shaping the defendant toward the crime.

All three of the issues raised above are real. No matter what the answers are one is led to this fundamental question: Should society treat autistic defendants differently than other kinds of defendants? Why or why not?

In June of 2002 the US Supreme Court ruled that executing people with intellectual disabilities violated the Eighth Amendment prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment. That decision, known as Atkins, had far-reaching implications.

The Court made several arguments, one being that people with intellectual disability may understand a specific act (such as shooting someone) but lack the intellectual capacity to understand the moral wrong of their action. Executing them for the act would therefore be wrong. Society has generally agreed with the Court. But what are the boundaries of the decision? What exactly defines an intellectually disabled person?

Death penalty opponents saw that decision as “chipping away” at legal execution, by carving out a protected group of people. Some thought that opened the door to the identification of other protected groups.

To my surprise, advocates for intellectually disabled people were not unanimous in praise of Atkins. Some opposed it; arguing that the court's opinion that ID people should be protected because they could not tell right from wrong would provide a basis for discrimination against them in more prosaic circumstances. Might the court's decision support denying an intellectually disabled person a job over imagined inability to tell right from wrong with respect to stealing money?

It’s hard to know if Supreme Court decisions trickle down to that extent but it’s clear that people think they do, or fear they will. Intellectually disabled people are certainly subject to many forms of marginalization. Observers make a leap from looking at a crime and theorizing why it was committed, to identifying people who have some imagined similarity to the defendant, and considering how those people may act in a less extreme context.

You might call this armchair psychology at its worst; thinking “a killer didn’t know right from wrong and he’s intellectually disabled,” to imagining the convenience store you manage, and how an intellectually disabled employee might harm you. Crazy as that sounds many of us have seen it in action.

At the same time, it’s true that some people don’t know right from wrong, and there is a strong moral argument that they should be protected from execution for doing a thing whose implications they cannot understand.

Note that the court only addressed the question of execution. They did not have issue with the idea that society deserves protection from criminals, whether intellectually disabled or not. The justices did not in any way equate intellectually disabled with not guilty.

The justices extended their thinking three years later. In March of 2005, in Roper vs. Simmons, the Court held that the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments forbade the execution of offenders who were under the age of 18 when their crimes were committed.

Justice Kennedy, writing for the majority, said: When a juvenile offender commits a heinous crime, the State can exact forfeiture of some of the most basic liberties, but the State cannot extinguish his life and his potential to attain a mature understanding of his own humanity.

That application of a controversial idea from Atkins was not questioned in this context because the intellectual limitation was grounded in youth as opposed to so-called permanent disability. A subsequent decision extended the protection of youth to age 21.

Prior to Atkins and Roper the court recognized other situations where individuals could not recognize right from wrong. Over the years those arguments led to the idea of psychiatric hospitalization instead of prison in cases of insanity, and mercy for those who committed crimes in the heat of passion.

We now face the next step in the application of this path of thinking. If a person who cannot understand the moral implications of their acts must be protected, and an undeveloped mind falls under this protection, then a person whose mind is undeveloped through the combination of youth and developmental delay should be protected by extension of the arguments in Atkins and Roper.

Autism is a developmental delay. That means the cognitive abilities of a young autistic adult may still be those of a child, even some years into legal adulthood, which should qualify them as part of the protected group. Furthermore, there is considerable overlap between the autistic and intellectually disabled populations so the original application of Atkins may be arguable there too.

Autism is one condition that causes delayed moral maturation in some non intellectually disabled people. There are other possible causes, which raises the point that one’s ability to know right from wrong in the mature way expected by the Court does not magically appear on one’s 21stbirthday. Some come to that ability sooner, more later, and a few never get there.

One challenge the public faces when applying and understanding this reasoning in high profile cases is the nature of the crimes. What if the young person who supposedly did not know right from wrong killed a number of kids in school?

The truth is, all capital murder cases are horrific in their details. We talk dispassionately about how intellectual disability should protect Atkins from execution for what he did, without giving much thought to what that was. In fact he willingly abducted, robbed and murdered an innocent person he and his friend found at a nearby convenience store. Roper participated in a break in and robbery, after which they tied up and blindfolded their victim, drove her to a state park and threw her off a bridge.

In these decisions the justices recognize the merciful nature of an advancing society, and the recognition that it’s morally wrong to execute people who cannot understand the implications of their actions, for a variety of reasons. The argument for extending the protections set out in Atkins a bit further is not without merit. However the absence of definite boundaries makes its definition far from clear.

There is another moral issue at play, which is that the justification for protecting a killer with a cognitive disability may contribute to marginalization of many innocent people with the same cognitive disability. They might feel the greater moral imperative lies with protecting themselves, even if that bodes ill for the killer.

Some people (a large part of the US population) are morally opposed to all executions, and so see this as superfluous. Others (also a significant group) support the death penalty but make exceptions for a small number of people. A smaller minority of Americans support the death penalty for all, in the case of most serious crimes, and therefore disagree with Atkins and successive decisions.

These are difficult questions, with unexpected complexity.

(c) 2018 John Elder Robison

John Elder Robison is an autistic adult and advocate for people with neurological differences. He's the author of Look Me in the Eye, Be Different, Raising Cubby, and Switched On. He serves on the Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee of the US Dept of Health and Human Services. He's co-founder of the TCS Auto Program (A school for teens with developmental challenges) and he’s the Neurodiversity Scholar at the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia. He's also a visiting professor of practice at Bay Path University in Longmeadow, Massachusetts and advisor to the Neurodiversity Institute at Landmark College in Putney, Vermont.

The opinions expressed here are his own. There is no warranty expressed or implied. While reading this essay will give you food for thought, actually printing and eating it may make you sick.

(c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

· People with autism are more likely to be victims than perpetrators of aggressive violence. · In many cases spree killers kill themselves, or are killed by police, and no official mental health diagnoses emerge. Suggestions of autism or anything else are therefore speculation which is rightly criticized as inflammatory;· Even when a credible diagnosis exists there is considerable dispute about any role autism may have played in shaping the defendant toward the crime.

All three of the issues raised above are real. No matter what the answers are one is led to this fundamental question: Should society treat autistic defendants differently than other kinds of defendants? Why or why not?

In June of 2002 the US Supreme Court ruled that executing people with intellectual disabilities violated the Eighth Amendment prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment. That decision, known as Atkins, had far-reaching implications.

The Court made several arguments, one being that people with intellectual disability may understand a specific act (such as shooting someone) but lack the intellectual capacity to understand the moral wrong of their action. Executing them for the act would therefore be wrong. Society has generally agreed with the Court. But what are the boundaries of the decision? What exactly defines an intellectually disabled person?

Death penalty opponents saw that decision as “chipping away” at legal execution, by carving out a protected group of people. Some thought that opened the door to the identification of other protected groups.

To my surprise, advocates for intellectually disabled people were not unanimous in praise of Atkins. Some opposed it; arguing that the court's opinion that ID people should be protected because they could not tell right from wrong would provide a basis for discrimination against them in more prosaic circumstances. Might the court's decision support denying an intellectually disabled person a job over imagined inability to tell right from wrong with respect to stealing money?

It’s hard to know if Supreme Court decisions trickle down to that extent but it’s clear that people think they do, or fear they will. Intellectually disabled people are certainly subject to many forms of marginalization. Observers make a leap from looking at a crime and theorizing why it was committed, to identifying people who have some imagined similarity to the defendant, and considering how those people may act in a less extreme context.

You might call this armchair psychology at its worst; thinking “a killer didn’t know right from wrong and he’s intellectually disabled,” to imagining the convenience store you manage, and how an intellectually disabled employee might harm you. Crazy as that sounds many of us have seen it in action.

At the same time, it’s true that some people don’t know right from wrong, and there is a strong moral argument that they should be protected from execution for doing a thing whose implications they cannot understand.

Note that the court only addressed the question of execution. They did not have issue with the idea that society deserves protection from criminals, whether intellectually disabled or not. The justices did not in any way equate intellectually disabled with not guilty.

The justices extended their thinking three years later. In March of 2005, in Roper vs. Simmons, the Court held that the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments forbade the execution of offenders who were under the age of 18 when their crimes were committed.

Justice Kennedy, writing for the majority, said: When a juvenile offender commits a heinous crime, the State can exact forfeiture of some of the most basic liberties, but the State cannot extinguish his life and his potential to attain a mature understanding of his own humanity.

That application of a controversial idea from Atkins was not questioned in this context because the intellectual limitation was grounded in youth as opposed to so-called permanent disability. A subsequent decision extended the protection of youth to age 21.

Prior to Atkins and Roper the court recognized other situations where individuals could not recognize right from wrong. Over the years those arguments led to the idea of psychiatric hospitalization instead of prison in cases of insanity, and mercy for those who committed crimes in the heat of passion.

We now face the next step in the application of this path of thinking. If a person who cannot understand the moral implications of their acts must be protected, and an undeveloped mind falls under this protection, then a person whose mind is undeveloped through the combination of youth and developmental delay should be protected by extension of the arguments in Atkins and Roper.

Autism is a developmental delay. That means the cognitive abilities of a young autistic adult may still be those of a child, even some years into legal adulthood, which should qualify them as part of the protected group. Furthermore, there is considerable overlap between the autistic and intellectually disabled populations so the original application of Atkins may be arguable there too.

Autism is one condition that causes delayed moral maturation in some non intellectually disabled people. There are other possible causes, which raises the point that one’s ability to know right from wrong in the mature way expected by the Court does not magically appear on one’s 21stbirthday. Some come to that ability sooner, more later, and a few never get there.

One challenge the public faces when applying and understanding this reasoning in high profile cases is the nature of the crimes. What if the young person who supposedly did not know right from wrong killed a number of kids in school?

The truth is, all capital murder cases are horrific in their details. We talk dispassionately about how intellectual disability should protect Atkins from execution for what he did, without giving much thought to what that was. In fact he willingly abducted, robbed and murdered an innocent person he and his friend found at a nearby convenience store. Roper participated in a break in and robbery, after which they tied up and blindfolded their victim, drove her to a state park and threw her off a bridge.

In these decisions the justices recognize the merciful nature of an advancing society, and the recognition that it’s morally wrong to execute people who cannot understand the implications of their actions, for a variety of reasons. The argument for extending the protections set out in Atkins a bit further is not without merit. However the absence of definite boundaries makes its definition far from clear.

There is another moral issue at play, which is that the justification for protecting a killer with a cognitive disability may contribute to marginalization of many innocent people with the same cognitive disability. They might feel the greater moral imperative lies with protecting themselves, even if that bodes ill for the killer.

Some people (a large part of the US population) are morally opposed to all executions, and so see this as superfluous. Others (also a significant group) support the death penalty but make exceptions for a small number of people. A smaller minority of Americans support the death penalty for all, in the case of most serious crimes, and therefore disagree with Atkins and successive decisions.

These are difficult questions, with unexpected complexity.

(c) 2018 John Elder Robison

John Elder Robison is an autistic adult and advocate for people with neurological differences. He's the author of Look Me in the Eye, Be Different, Raising Cubby, and Switched On. He serves on the Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee of the US Dept of Health and Human Services. He's co-founder of the TCS Auto Program (A school for teens with developmental challenges) and he’s the Neurodiversity Scholar at the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia. He's also a visiting professor of practice at Bay Path University in Longmeadow, Massachusetts and advisor to the Neurodiversity Institute at Landmark College in Putney, Vermont.

The opinions expressed here are his own. There is no warranty expressed or implied. While reading this essay will give you food for thought, actually printing and eating it may make you sick.

(c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

Published on April 13, 2018 06:45

April 7, 2018

Autism - Ability, Disability, and the ICF Core Set

How do you define autism? Five years ago I became an autistic member of the steering committee for the World Health Organization’s Autism ICF Core Set project. This January the Core Set was released. You can read it here:

http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/...

You can read about the process in our group’s earlier papers, which are listed in the above article.

The Core Set identifies the ways autism affects us, and gives a better focus for understanding and study. One thing I am proud of Is that this represents the first time the WHO has recognized both disability and exceptionality in a condition. Before autism, the WHO’s descriptions only described degrees of diminished function. Now, with the autism set, we recognize that exceptional abilities in certain areas of function can be just as characteristic of autism as disabilities in others.

For the first time a WHO definition encompasses what we call social and medical models of autism by integrating how we engage the wider world into the characteristic description of how autism shapes us.

It’s also noteworthy that this is one of the first (if not the first) Core Set to be developed with the input of actual affected individuals.