Sesshu Foster's Blog, page 11

April 1, 2015

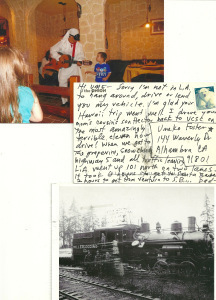

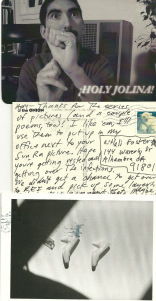

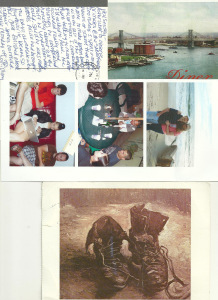

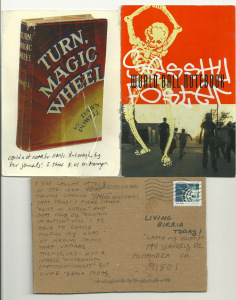

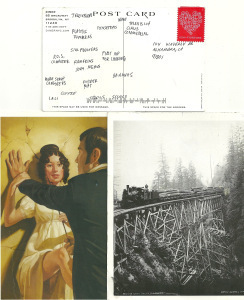

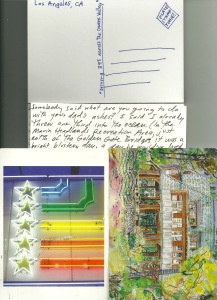

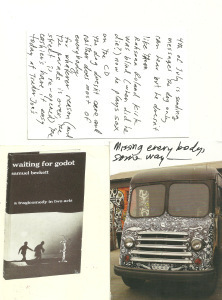

Postcards, March 2015

good morning postcard

fish scales, each particle licensed by the city, flying about like those seagull cries escaping from a torn and rent denim outlook, molecular personalities waiting on suburbs with apocalyptic eyelashes, fingernail eyebrows almost roaring down the straightaway except for colored enumeration in petroleum, except for happy smiles, car doors slamming twice when I cough Calif., stir Calif. into coffee that���s almost like coffee, the bed, a pause, somebody wears my clothes all vertical and almost good, fearfully congealed on surfaces, laminated by mucous and horizons, I exit or attempt to exit between a shrub and its leaves, between a sunrise and its eyelid, locate an elbow in the neck, recover memory in fingertips and dog, it���s all there in the photograph I was dreaming I���d deliver to you, photograph of black money, white corn syrup, thanks to you, wherever you may be (I see you eating pancakes on top of a skyscraper made of pancakes, nothing they shall ever do to me can erase that chilly wind)

March 30, 2015

‘A man passes with a load of bread on his shoulder’ by Cesar Vallejo

Un hombre pasa con un pan al hombro… por Cesar Vallejo

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HOFtmb2ds9Q

Un hombre pasa con un pan al hombro.

��Voy a escribir, despu��s, sobre mi doble?

Otro se sienta, r��scase, extrae un piojo de su axila,��m��talo.

��Con qu�� valor hablar del psicoan��lisis?

Otro ha entrado a mi pecho con un palo en la mano.

��Hablar luego de S��crates al m��dico?

Un cojo pasa dando el brazo a un ni��o.

��Voy, despu��s, a leer a Andr�� Bret��n?

Otro tiembla de fr��o, tose, escupe sangre.

��Cabr�� aludir jam��s al Yo profundo?

Otro busca en el fango huesos, c��scaras,

��C��mo escribir, despu��s, del infinito?

Un alba��il cae de un techo, muere y ya no almuerza.

��Innovar, luego, el tropo, la met��fora?

Un comerciante roba un gramo en el peso a un cliente,

��Hablar, despu��s, de cuarta dimensi��n?

Un banquero falsea su balance.

��Con qu�� cara llorar en el teatro?

Un paria duerme con el pie a la espalda.

��Hablar, despu��s, a nadie de Picasso?

Alguien va en un entierro sollozando.

��C��mo luego ingresar a la Academia?

Alguien limpia un fusil en su cocina.

��Con qu�� valor hablar del m��s all��?

Alguien pasa contando con sus dedos.

��C��mo hablar del no-yo sin dar un grito

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lOZiK22SQaE

A man passes with a load of bread on his shoulder

After that, am I going to write about my double?

Another sits and scratches, finds a louse and kills it.

What���s the point of discussing psychoanalysis then?

Another has entered my chest, club in hand.

Shall I talk Socrates to the doctor?

The cripple goes by, a kid on his arm.

I’ll read read Andre Breton after that?

Another shivers from cold, coughs, spits blood.

Never to fit again, those most profound allusions?

Another gropes the pile for bones, rinds?

How to write, after that, about the infinite?

A bricklayer falls off the roof and dies, no longer eats lunch.

Innovate then the trope, the metaphor?

The retailer cheats his client out of a gram by weight.

Afterward, we���ll be talking about the 4th dimension?

A banker falsifies his balance.

Like this, this face, weeping in the theater?

The homeless person sleeps feet folded underneath.

Later, can anybody be talking about Picasso?

Someone weeps on the way to the burial.

After that, how to work your way into academia?

Someone cleans arms in their kitchen.

How will we speak of what exists in the world beyond?

Someone passes counting on their fingers.

How to speak of some Other without howling?

Second International Conference of Anti-fascist writers, Madrid 1937

March 29, 2015

later

in another sense, when we don’t feel so ill, when we’re better

as an afterthought, in the litter behind the giant yucca hedge

in between one concept and the next, framing all colorization

in the flats, telling ourselves stuff we decided to believe

in one untold story, whoever it was who said they’d get back to you

they did get back to you… in the shade of the ficus against the wall

in another version, you didn’t resent the person you always acted like

in dreams where you were always busy, hurrying to get things done

in a lapse, when the sound system cuts out, pausing for a moment

in a variant, where supposedly he not only followed through, he

actually did something no one else was able to do, without fear

or expectation, even that anyone would ever might know,

in that spot, somewhat implausibly, just did what he could do

March 28, 2015

“Happy Saturday morning Dad.”

March 25, 2015

Are You Okay? by Edgar Hernandez

Are You Okay?

Foster is a snowflake.

His jeans are timeless.

His classroom walls are pale.

His students feed on knowledge.

He teaches like the many wonders of the world.

He towers all of his students.

He hunts those who use a phone in class.

His eyes, although small, love to dance around the room.

His grip is stronger than a father���s instinct.

His black shirt is lighter than any shade of white.

He murders noise during a reading session.

He reserves his voice to be used in his thoughts.

He loves right answers no less than Lucy���s brownies.

His watch speaks cheap but screams coolness.

His sarcasm is stronger than a mother���s care.

His hair are goals for all men over 40.

He laughs in the face of absurdity and embarrassment.

He walks miles to get to a student.

He rubs his eyes to kill the morning.

His writing apologizes to no one.

His temper is calm like an untouched pond.

His pay would not convince to become a teacher.

He became a teacher.

He teaches to seed the next human citizen.

He would love to know if you are okay.

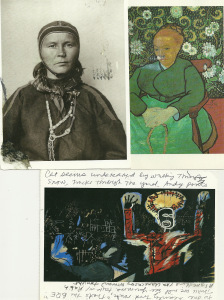

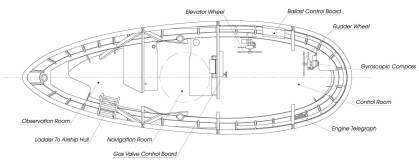

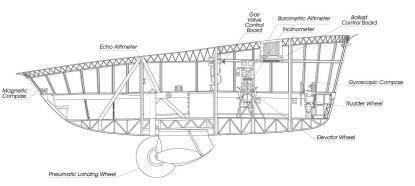

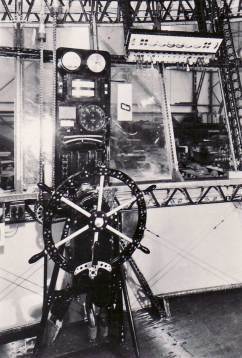

Airship built by factory workers, Moscow, 1924

March 24, 2015

Are You Dead? Postcard

I had not heard from R. in I don’t know, a couple of years or more. He moved to the Bay Area a year or two ago, I think. He was worried about M. “Hey man, have you heard from M.? I heard that she died. No one can get ahold of her. Have you had any news from her recently? I’m really concerned. J., from the L.A. Times, told me she heard something to that effect, too. So I’m really worried.” So I called M. As usual, she let the call go to message, but as I was leaving the message, “Hey, how are you? This is S., just checking in. R. called me, he heard—I mean… he’s worried about you…” —she picked up, immediately I could tell she was fine. I could hear laughter in her voice, happy to hear me, speaking out of the blue, after intervening years. “You sound good,” I said. “I am, you know, I”m happy,” she said. We talked for awhile, catching up. M. got around to asking me about W., how I dealt with hearing that W. had died. “That hit me hard,” she said. “I couldn’t even… I couldn’t even believe it, I couldn’t process it. You know? She was, I don’t know, something like the mother of us all. Her effect on my work was just incalculable. You know, when I was coming up, she was my role model, my mentor, everything. She had such an effect on me. She had this sort of mean persona, but really, underneath it, she was always supportive of everybody.” She asked me how W.’s death had affected me, how I’d felt when I’d heard that. She told me that she had stopped writing, “I just had to let that go. I had to. I had to make peace with that. And I did. I am, I’m happy.” She mentioned that M.S. also had died, and A. died. Did I have contact information for A.’s people? I said the last time I saw A. was one of the last times I saw W. We were checking into the motel next to Naropa, where Naropa puts up its summer instructors. W. and her husband were walking across the parking lot to their room and I called out, but W. said she couldn’t talk right at that moment. The strange thing was that she called me in my room shortly thereafter, and we talked over the phone, four doors down from each other. By that time she’d moved out to the desert, I told M. “You were gone, W. was out in the desert, A. was living out here in Boulder, teaching at Naropa,” I said. “The whole scene we knew was over and gone.” “How did you feel about that?” M. asked. “I don’t know. That it was a loss. It was more than just a social scene was gone, because you know, when R. used to invite me to writing circles, to hang out with writers or whatever, I never went, I was never into socializing… It was more than that, for me. It was the rise of a whole L.A. aesthetic, an articulation, a dialogue,” I said, “And poof, it was gone. Whatever had happened, it was gone. What was there to do about it? What could I do about it? Everybody left. I just kept going. Yeah, that was the last time I talked to A., out in Naropa while she chain-smoked, sitting on a bike rack under a cottonwood tree.” M. said, “she wasn’t even fifty.” “I got messages and emails about the memorials they held for her in Brooklyn and L.A. Some have contact information, probably; I’ll forward them to you.” So I texted R., “M. is fine.” “That’s a relief, thanks,” he replied. Those people came and went; mention them to some kid now, if they even recognize the names at all, they’d think, all those people were from a previous century. We got the 21st century now.

March 14, 2015

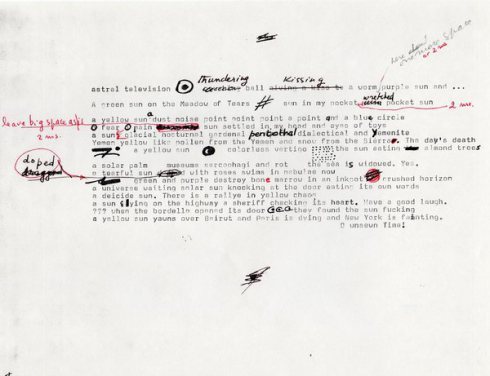

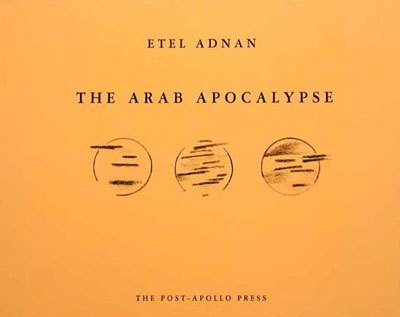

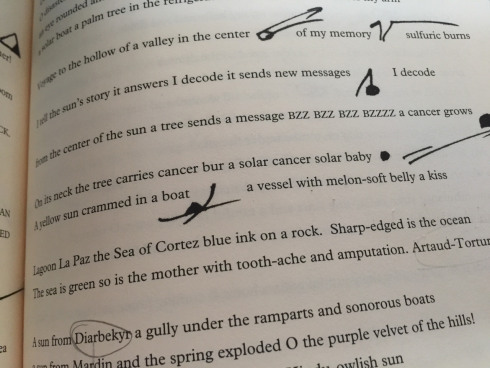

Etel Adnan reads from The Arab Apocalypse

audio file:

http://telegraph-books.net/mondayarchive/audio/090202-etel-adnan.mp3

see also

http://www.eteladnan.com/thearabapocalypse.html

more Etel Adnan videos:

http://www.eteladnan.com/videos

and see also:��http://www.spdbooks.org/Producte/9780...

March 5, 2015

The Blue Garage Postcard

a handful of people amid desultory scattering of student desks,

what's going on? nothing? the instructor who is a pal,

doesn't have programming or agenda, turns to me,

"you want to read something? you got something?"

of course, i always have something. i can always do something.

i'll read, "the blue garage." but what is "the blue garage"?

it was supposed to be something i could run through without thinking.

but now i can't recall exactly what it was. i just need something,

just a little clue, a word would suffice, just to get started.

hold on, i'll do this. i got this. but i can't remember what it was.

it's like everything has gone dark, and indeed, i am standing in

the middle of the blue garage. it's an old abandoned garage, debris,

blue paint blistered and peeling, and i've been standing there so long

only one person's left, my host leads me away. there's a reception or

gathering afterward in some little downtown storefront, but

i'm in no mood, disgusted with myself, later i wake up in a

furniture store in a pile of rugs, it's morning in the town, time to go.

February 23, 2015

Analysis Postcard

���Abyss (from The Emily Dickinson Series).��� Janet Malcolm, 2013.

Emily Dickinson, arguably one of America���s foremost poets, is characterized by critics as able to capture extreme emotional states in her greatest work. Recent dating of her poems offers the periodicity of her writing as a behavior that can be examined for patterns of affective illness that may relate to these states. The bulk of Dickinson���s work was written during a clearly defined 8-year period when she was age 28���35. Poems written during that period, 1858���1865, were grouped by year and examined for annual and seasonal distribution. Her 8-year period of productivity was marked by two 4-year phases. The first shows a seasonal pattern characterized by greater creative output in spring and summer and a lesser output during the fall and winter. This pattern was interrupted by an emotional crisis that marked the beginning of the second phase, a 4-year sustained period of greatly heightened productivity and the emergence of a revolutionary poetic style. These data, supported by excerpts from letters to friends during this period of Dickinson���s life, demonstrate seasonal changes in mood during the first four years of major productivity, followed by a sustained elevation of creative energy, mood, and cognition during the second. They suggest, as supported by family history, a bipolar pattern previously described in creative artists.

Sincerely,

John F. McDermott M.D.

���Crater (from The Emily Dickinson Series).����� Janet Malcolm, 2013.

��

Sesshu Foster's Blog

- Sesshu Foster's profile

- 41 followers