Sesshu Foster's Blog, page 16

August 4, 2014

Poems for Gaza by Mahmoud Darwish

“Under Siege” by Mahmoud Darwish

Here on the slopes of hills, facing the dusk and the cannon of time

Close to the gardens of broken shadows,

We do what prisoners do,

And what the jobless do:

We cultivate hope.

***

A country preparing for dawn. We grow less intelligent

For we closely watch the hour of victory:

No night in our night lit up by the shelling

Our enemies are watchful and light the light for us

In the darkness of cellars.

***

Here there is no “I”.

Here Adam remembers the dust of his clay.

***

On the verge of death, he says:

I have no trace left to lose:

Free I am so close to my liberty. My future lies in my own hand.

Soon I shall penetrate my life,

I shall be born free and parentless,

And as my name I shall choose azure letters…

***

You who stand in the doorway, come in,

Drink Arabic coffee with us

And you will sense that you are men like us

You who stand in the doorways of houses

Come out of our morningtimes,

We shall feel reassured to be

Men like you!

***

When the planes disappear, the white, white doves

Fly off and wash the cheeks of heaven

With unbound wings taking radiance back again, taking possession

Of the ether and of play. Higher, higher still, the white, white doves

Fly off. Ah, if only the sky

Were real [a man passing between two bombs said to me].

***

Cypresses behind the soldiers, minarets protecting

The sky from collapse. Behind the hedge of steel

Soldiers piss — under the watchful eye of a tank —

And the autumnal day ends its golden wandering in

A street as wide as a church after Sunday mass…

***

[To a killer] If you had contemplated the victim’s face

And thought it through, you would have remembered your mother in the

Gas chamber, you would have been freed from the reason for the rifle

And you would have changed your mind: this is not the way

to find one’s identity again.

***

The siege is a waiting period

Waiting on the tilted ladder in the middle of the storm.

***

Alone, we are alone as far down as the sediment

Were it not for the visits of the rainbows.

***

We have brothers behind this expanse.

Excellent brothers. They love us. They watch us and weep.

Then, in secret, they tell each other:

“Ah! if this siege had been declared…” They do not finish their sentence:

“Don’t abandon us, don’t leave us.”

***

Our losses: between two and eight martyrs each day.

And ten wounded.

And twenty homes.

And fifty olive trees…

Added to this the structural flaw that

Will arrive at the poem, the play, and the unfinished canvas.

***

A woman told the cloud: cover my beloved

For my clothing is drenched with his blood.

***

If you are not rain, my love

Be tree

Sated with fertility, be tree

If you are not tree, my love

Be stone

Saturated with humidity, be stone

If you are not stone, my love

Be moon

In the dream of the beloved woman, be moon

[So spoke a woman

to her son at his funeral]

***

Oh watchmen! Are you not weary

Of lying in wait for the light in our salt

And of the incandescence of the rose in our wound

Are you not weary, oh watchmen?

***

A little of this absolute and blue infinity

Would be enough

To lighten the burden of these times

And to cleanse the mire of this place.

***

It is up to the soul to come down from its mount

And on its silken feet walk

By my side, hand in hand, like two longtime

Friends who share the ancient bread

And the antique glass of wine

May we walk this road together

And then our days will take different directions:

I, beyond nature, which in turn

Will choose to squat on a high-up rock.

***

On my rubble the shadow grows green,

And the wolf is dozing on the skin of my goat

He dreams as I do, as the angel does

That life is here…not over there.

***

In the state of siege, time becomes space

Transfixed in its eternity

In the state of siege, space becomes time

That has missed its yesterday and its tomorrow.

***

The martyr encircles me every time I live a new day

And questions me: Where were you? Take every word

You have given me back to the dictionaries

And relieve the sleepers from the echo’s buzz.

***

The martyr enlightens me: beyond the expanse

I did not look

For the virgins of immortality for I love life

On earth, amid fig trees and pines,

But I cannot reach it, and then, too, I took aim at it

With my last possession: the blood in the body of azure.

***

The martyr warned me: Do not believe their ululations

Believe my father when, weeping, he looks at my photograph

How did we trade roles, my son, how did you precede me.

I first, I the first one!

***

The martyr encircles me: my place and my crude furniture are all that I have changed.

I put a gazelle on my bed,

And a crescent of moon on my finger

To appease my sorrow.

***

The siege will last in order to convince us we must choose an enslavement that does no harm, in fullest liberty!

***

Resisting means assuring oneself of the heart’s health,

The health of the testicles and of your tenacious disease:

The disease of hope.

***

And in what remains of the dawn, I walk toward my exterior

And in what remains of the night, I hear the sound of footsteps inside me.

***

Greetings to the one who shares with me an attention to

The drunkenness of light, the light of the butterfly, in the

Blackness of this tunnel!

***

Greetings to the one who shares my glass with me

In the denseness of a night outflanking the two spaces:

Greetings to my apparition.

***

My friends are always preparing a farewell feast for me,

A soothing grave in the shade of oak trees

A marble epitaph of time

And always I anticipate them at the funeral:

Who then has died…who?

***

Writing is a puppy biting nothingness

Writing wounds without a trace of blood.

***

Our cups of coffee. Birds green trees

In the blue shade, the sun gambols from one wall

To another like a gazelle

The water in the clouds has the unlimited shape of what is left to us

Of the sky. And other things of suspended memories

Reveal that this morning is powerful and splendid,

And that we are the guests of eternity.

………………… Ramallah, January 2002

Mahmoud Darwish (1941-2008): Under Siege, from A State of Siege, 2002, translated by Marjolijn De Jager

from http://tomclarkblog.blogspot.com/2014/07/mahmoud-darwish-under-siege.html

“Silence for Gaza” by Mahmoud Darwish

Gaza is far from its relatives and close to its enemies, because whenever Gaza explodes, it becomes an island and it never stops exploding. It scratched the enemy’s face, broke his dreams and stopped his satisfaction with time.

Because in Gaza time is something different.

Because in Gaza time is not a neutral element.

It does not compel people to cool contemplation, but rather to explosion and a collision with reality.

Time there does not take children from childhood to old age, but rather makes them men in their first confrontation with the enemy.

Time in Gaza is not relaxation, but storming the burning noon. Because in Gaza values are different, different, different.

The only value for the occupied is the extent of his resistance to occupation. That is the only competition there. Gaza has been addicted to knowing this cruel, noble value. It did not learn it from books, hasty school seminars, loud propaganda megaphones, or songs. It learned it through experience alone and through work that is not done for advertisement and image.

Gaza has no throat. Its pores are the ones that speak in sweat, blood, and fires. Hence the enemy hates it to death and fears it to criminality, and tries to sink it into the sea, the desert, or blood. And hence its relatives and friends love it with a coyness that amounts to jealousy and fear at times, because Gaza is the brutal lesson and the shining example for enemies and friends alike.

Gaza is not the most beautiful city.

Its shore is not bluer than the shores of Arab cities.

Its oranges are not the most beautiful in the Mediterranean basin.

Gaza is not the richest city.

It is not the most elegant or the biggest, but it equals the history of an entire homeland, because it is more ugly, impoverished, miserable, and vicious in the eyes of enemies. Because it is the most capable, among us, of disturbing the enemy’s mood and his comfort. Because it is his nightmare. Because it is mined oranges, children without a childhood, old men without old age and women without desires. Because of all this it is the most beautiful, the purest and richest among us and the one most worthy of love.

We do injustice to Gaza when we look for its poems, so let us not disfigure Gaza’s beauty. What is most beautiful in it is that it is devoid of poetry at a time when we tried to triumph over the enemy with poems, so we believed ourselves and were overjoyed to see the enemy letting us sing. We let him triumph, then when we dried our lips of poems we saw that the enemy had finished building cities, forts and streets. We do injustice to Gaza when we turn it into a myth, because we will hate it when we discover that it is no more than a small poor city that resists.

We do injustice when we wonder: What made it into a myth? If we had dignity, we would break all our mirrors and cry or curse it if we refuse to revolt against ourselves. We do injustice to Gaza if we glorify it, because being enchanted by it will take us to the edge of waiting and Gaza doesn’t come to us. Gaza does not liberate us. Gaza has no horses, airplanes, magic wands, or offices in capital cities. Gaza liberates itself from our attributes and liberates our language from its Gazas at the same time. When we meet it – in a dream – perhaps it won’t recognize us, because Gaza was born out of fire, while we were born out of waiting and crying over abandoned homes.

It is true that Gaza has its special circumstances and its own revolutionary traditions. But its secret is not a mystery: Its resistance is popular and firmly joined together and knows what it wants (it wants to expel the enemy out of its clothes). The relationship of resistance to the people is that of skin to bones and not a teacher to students. Resistance in Gaza did not turn into a profession or an institution.

It did not accept anyone’s tutelage and did not leave its fate hinging on anyone’s signature or stamp.

It does not care that much if we know its name, picture, or eloquence. It did not believe that it was material for media. It did not prepare for cameras and did not put smiling paste on its face.

Neither does it want that, nor we.

Hence, Gaza is bad business for merchants and hence it is an incomparable moral treasure for Arabs.

What is beautiful about Gaza is that our voices do not reach it. Nothing distracts it; nothing takes its fist away from the enemy’s face. Not the forms of the Palestinian state we will establish whether on the eastern side of the moon, or the western side of Mars when it is explored. Gaza is devoted to rejection… hunger and rejection, thirst and rejection, displacement and rejection, torture and rejection, siege and rejection, death and rejection.

Enemies might triumph over Gaza (the storming sea might triumph over an island… they might chop down all its trees).

They might break its bones.

They might implant tanks on the insides of its children and women. They might throw it into the sea, sand, or blood.

But it will not repeat lies and say “Yes” to invaders.

It will continue to explode.

It is neither death, nor suicide. It is Gaza’s way of declaring that it deserves to live.It will continue to explode.

It is neither death, nor suicide. It is Gaza’s way of declaring that it deserves to live.

[Translated by Sinan Antoon From Hayrat al-`A’id (The Returnee’s Perplexity), Riyad al-Rayyis, 2007]

from http://mondoweiss.net/2012/11/mahmoud-darwish-silence-for-gaza.html

“Ahmad Al-Za’tar” by Mahmoud Darwish

For two hands, of stone and of thyme

I dedicate this song. For Ahmad, forgotten between two butterflies

The clouds are gone and have left me homeless, and

The mountains have flung their mantles and concealed me

From the oozing old wound to the contours of the land I descend, and

The year marked the separation of the sea from the cities of ash, and

I was alone

Again alone

O alone? And Ahmad

Between two bullets was the exile of the sea

A camp grows and gives birth to fighters and to thyme

And an arm becomes strong in forgetfulness

Memory comes from trains that have left and

Platforms that are empty of welcome and of jasmine

In cars, in the landscape of the sea, in the intimate nights of prison cells

In quick liaisons and in the search for truth was

The discovery of self

In every thing, Ahmad found his opposite

For twenty years he was asking

For twenty years he was wandering

For twenty years, and for moments only, his mother gave him birth

In a vessel of banana leaves

And departed

He seeks an identity and is struck by the volcano

The clouds are gone and have left me homeless, and

The mountains have flung their mantles and concealed me

I am Ahmad the Arab, he said

I am the bullets, the oranges and the memory

Mahmoud Darwish (1941-2008): Ahmad Al-Za’tar, 1998, translated by Tania Nasir, 1998

A relative of two-year old Lamar Radiya holds her body at the morgue of the Kamal Adwan hospital in Beit Lahia: photo by Marco Longari / AFP,, 24 July 2014

Fady Joudah’s translation of “State of Seige” can be found in his translation of Darwish’s The Butterfly’s Burden:

https://www.powells.com/biblio/9781556592416

The body of Ali al-Shibari, a 10-year-old Palestinian child who was killed after a UN school in the northern Beit Hanun district of the Gaza Strip was hit by an Israeli shell, lies wrapped in shrouds at the morgue of the Kamal Adwan hospital in Beit Lahiya on July 24, 2014: photo by Mahmud Hams / AFP, 24 July 201

See also “Unfortunately It Was Paradise: Selected Poems” by Mahmoud Darwish,

http://www.powells.com/biblio/1-9780520237544-6

July 29, 2014

“Urban Tectonics” Postcard, to Eetalah

my hat is a wish for rain

I take my hat off to Dave Eggers

my hat is a cup of coffee

I take my hat off to Gerda Taro

My hat is a bright shiny notion

I take my hat off to Anne Braden

my hat is a hot summer day

I take my hat off to Violeta Parra

my hat is a momentary reflection

I take my hat off to Luis Rodriguez

my hat is a sometime thing

I take my hat off to Ken Chen

my hat is a passing truck

I take my hat off to the flock of parrots

July 25, 2014

Fun Randy Cauthen reading

July 21, 2014

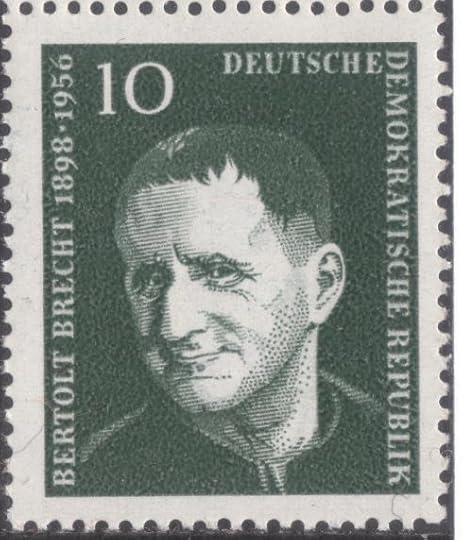

“5 Difficulties When Writing the Truth” by Bertolt Brecht and Brecht videos

WRITING THE TRUTH : THE FIVE DIFFICULTIES by Bertolt Brecht

Nowadays, anyone who wishes to combat lies and ignorance and to write the truth must overcome at least five difficulties. He must have the courage to write the truth when truth is everywhere opposed; the keenness to recognize it, although it is everywhere concealed; the skill to manipulate it as a weapon; the judgment to select those in whose hands it will be effective; and the cunning to spread the truth among such persons. These are formidable problems for writers living under Fascism, but they exist also for those writers who have fled or been exiled; they exist even for writers working in countries where civil liberty prevails.

1. The Courage to Write the Truth

It seems obvious that whoever writes should write the truth in the sense that he ought not to suppress or conceal truth or write something deliberately untrue. He ought not to cringe before the powerful, nor betray the weak. It is, of course, very hard not to cringe before the powerful, and it is highly advantageous to betray the weak. To displease the possessors means to become one of the dispossessed. To renounce payment for work may be the equivalent of giving up the work, and to decline fame when it is offered by the mighty may mean to decline it forever. This takes courage.

Times of extreme oppression are usually times when there is much talk about high and lofty matters. At such times it takes courage to write of low and ignoble matters such as food and shelter for workers; it takes courage when everyone else is ranting about the vital importance of sacrifice. When all sorts of honors are showered upon the peasants it takes courage to speak of machines and good stock feeds which would lighten their honorable labor. When every radio station is blaring that a man without knowledge or education is better than one who has studied, it takes courage to ask: better for whom? When all the talk is of perfect and imperfect races, it takes courage to ask whether it not hunger and ignorance and war that produce deformities.

And it also takes courage to tell the truth about oneself, about one’s own defeat. Many of the persecuted lose their capacity for seeing their own mistakes. It seems to them that the persecution itself is the greatest injustice. The persecutors are wicked simply because they persecute; the persecuted suffer because of their goodness. But this goodness has been beaten, defeated, suppressed; it was therefore a weak goodness, a bad, indefensible, unreliable goodness. For it will not do to grant that goodness must be weak as rain must be wet. It takes courage to say that the good were defeated not because they were good, but because they were weak.

Naturally, in the struggle with falsehood we must write the truth, and this truth must not be a lofty and ambiguous generality. When it is said of someone, “He spoke the truth,” this implies that some people or many people or least one person said something unlike the truth—a lie or a generality—but he spoke the truth, he said something practical, factual, undeniable, something to the point.

It takes little courage to mutter a general complaint, in a part of the world where complaining is still permitted, about the wickedness of the world and the triumph of barbarism, or to cry boldly that the victory of the human spirit is assured. There are many who pretend that cannons are aimed at them when in reality they are the target merely of opera glasses. They shout their generalized demands to a world of friends and harmless persons. They insist upon a generalized justice for which they have never done anything; they ask for generalized freedom and demand a share of the booty which they have long since enjoyed. They think that truth is only what sounds nice. If truth should prove to be something statistical, dry, or factual, something difficult to find and requiring study, they do not recognize it as truth; it does not intoxicate them. They possess only the external demeanor of truth-tellers. The trouble with them is: they do not know the truth.

2. The Keenness to Recognize the Truth

Since it is hard to write the truth because truth is everywhere suppressed, it seems to most people to be a question of character whether the truth is written or not written. They believe that courage alone will suffice. They forget the second obstacle: the difficulty of finding the truth. It is impossible to assert that the truth is easily ascertained.

First of all we strike trouble in determining what truth is worth the telling. For example, before the eyes of the whole world one great civilized nation after the other falls into barbarism. Moreover, everyone knows that the domestic war which is being waged by the most ghastly methods can at any moment be converted into a foreign war which may well leave our continent a heap of ruins. This, undoubtedly, is one truth, but there are others. Thus, for example, it is not untrue that chairs have seats and that rain falls downward. Many poets write truths of this sort. They are like a painter adorning the walls of a sinking ship with a still life. Our first difficulty does not trouble them and their consciences are clear. Those in power cannot corrupt them, but neither are they disturbed by the cries of the oppressed; they go on painting. The senselessness of their behavior engenders in them a “profound” pessimism which they sell at good prices; yet such pessimism would be more fitting in one who observes these masters and their sales. At the same time it is not easy to realize that their truths are truths about chairs or rain; they usually sound like truths about important things. But on closer examination it is possible to see that they say merely: a chair is a chair; and: no one can prevent the rain from falling down.

They do not discover the truths that are worth writing about. On the other hand, there are some who deal only with the most urgent tasks, who embrace poverty and do not fear rulers, and who nevertheless cannot find the truth. These lack knowledge. They are full of ancient superstitions, with notorious prejudices that in bygone days were often put into beautiful words. The world is too complicated for them; they do not know the facts; they do not perceive relationships. In addition to temperament, knowledge, which can be acquired, and methods, which can be learned, are needed. What is necessary for all writers in this age of perplexity and lightening change is a knowledge of the materialistic dialectic of economy and history. This knowledge can be acquired from books and from practical instruction, if the necessary diligence is applied. Many truths can be discovered in simpler fashion, or at least portions of truths, or facts that lead to the discovery of truths. Method is good in all inquiry, but it is possible to make discoveries without using any method—indeed, even without inquiry. But by such a casual procedure one does not come to the kind of presentation of truth which will enable men to act on the basis of that presentations. People who merely record little facts are not able to arrange the things of the world so that they can be easily controlled. Yet truth has this function alone and no other. Such people cannot cope with the requirement that they write the truth.

If a person is ready to write the truth and able to recognize it, there remain three more difficulties.

3. The Skill to Manipulate the Truth as a Weapon

The truth must be spoken with a view to the results it will produce in the sphere of action. As a specimen of a truth from which no results, or the wrong ones, follow, we can cite the widespread view that bad conditions prevail in a number of countries as a result of barbarism. In this view, Fascism is a wave of barbarism which has descended upon some countries with the elemental force of a natural phenomenon.

According to this view, Fascism is a new, third power beside (and above) capitalism and socialism; not only the socialist movement but capitalism as well might have survived without the intervention of Fascism. And so on. This is, of course, a Fascist claim; to accede to it is a capitulation to Fascism. Fascism is a historic phase of capitalism; in this sense it is something new and at the same time old. In Fascist countries capitalism continues to exist, but only in the form of Fascism; and Fascism can be combated as capitalism alone, as the nakedest, most shameless, most oppressive, and most treacherous form of capitalism.

But how can anyone tell the truth about Fascism, unless he is willing to speak out against capitalism, which brings it forth? What will be the practical results of such truth?

Those who are against Fascism without being against capitalism, who lament over the barbarism that comes out of barbarism, are like people who wish to eat their veal without slaughtering the calf. They are willing to eat the calf, but they dislike the sight of blood. They are easily satisfied if the butcher washes his hands before weighing the meat. They are not against the property relations which engender barbarism; they are only against barbarism itself. They raise their voices against barbarism, and they do so in countries where precisely the same property relations prevail, but where the butchers wash their hands before weighing the meat.

Outcries against barbarous measures may be effective as long as the listeners believe that such measures are out of the question in their own countries. Certain countries are still able to maintain their property relations by methods that appear less violent than those used in other countries. Democracy still serves in these countries to achieve the results for which violence is needed in others, namely, to guarantee private ownership of the means of production. The private monopoly of factories, mines, and land creates barbarous conditions everywhere, but in some places these conditions do not so forcibly strike the eye. Barbarism strikes the eye only when it happens that monopoly can be protected only by open violence.

Some countries, which do not yet find it necessary to defend their barbarous monopolies by dispensing with the formal guarantees of a constitutional state, as well as with such amenities as art, philosophy, and literature, are particularly eager to listen to visitors who abuse their native lands because those amenities are denied there. They gladly listen because they hope to derive from what they hear advantages in future wars. Shall we say that they have recognized the truth who, for example, loudly demand an unrelenting struggle against Germany “because that country is now the true home of Evil in our day, the partner of hell, the abode of the Antichrist”? We should rather say that these are foolish and dangerous people. For the conclusion to be drawn from this nonsense is that since poison gas and bombs do not pick out the guilty, Germany must be exterminated—the whole country and all its people.

The man who does not know the truth expresses himself in lofty, general, and imprecise terms. He shouts about “the” German, he complains about Evil in general, and whoever hears him cannot make out what to do. Shall he decide not to be a German? Will hell vanish if he himself is good? The silly talk about the barbarism that comes out of barbarism is also of this kind. The source of barbarism is barbarism, and it is combated by culture, which comes from education. All this is put in general terms; it is not meant to be a guide to action and is in reality addressed to no one.

Such vague descriptions point to only a few links in the chain of causes. Their obscurantism conceals the real forces making for disaster. If light be thrown on the matter it promptly appears that disasters are caused by certain men. For we live in a time when the fate of man is determined by men.

Fascism is not a natural disaster which can be understood simply in terms of “human nature.” But even when we are dealing with natural catastrophes, there are ways to portray them which are worthy of human beings because they appeal to man’s fighting spirit.

After a great earthquake that destroyed Yokohama, many American magazines published photographs showing a heap of ruins. The captions read: STEEL STOOD. And, to be sure, though one might see only ruins at first glance, the eye swiftly discerned, after noting the caption, that a few tall buildings had remained standing. Among the multitudinous descriptions that can be given of an earthquake, those drawn up by construction engineers concerning the shifts in the ground, the force of stresses, the best developed, etc., are of the greatest importance, for they lead to future construction which will withstand earthquakes. If anyone wishes to describe Fascism and war, great disasters which are not natural catastrophes, he must do so in terms of a practical truth. He must show that these disasters are launched by the possessing classes to control the vast numbers of workers who do not own the means of production.

If one wishes successfully to write the truth about evil conditions, one must write it so that the causes of evil might be identified and averted. If the preventable causes can be identified, the evil conditions can be fought.

4. The Judgment to Select Those in Whose Hands the Truth Will Be Effective

The century-old custom of trade in critical and descriptive writing and the fact that the writer has been relived of concern for the destination of what he has written have caused him to labor under a false impression. He believes that his customer or employer, the middleman, passes on what he has written to everyone. The writer thinks: I have spoken and those who wish to hear will hear me. In reality he has spoken and those who are able to pay hear him. A great deal, though still too little, has been said about his; I merely want to emphasize that “writing for someone” has been transformed into merely “writing.” But the truth cannot merely be written; it must be written for someone, someone who can do something with it. The process of recognizing truth is the same for writers and readers. In order to say good things, one’s hearing must be good and one must hear good things. The truth must be spoke deliberately and listened to deliberately. And for us writers it is important to whom we tell the truth and who tells it to us.

We must tell the truth about evil conditions to those for whom the conditions are worst, and we must also learn the truth from them. We must address not only people who hold certain views, but people who, because of their situation, should hold these views. And the audience is continually changing. Even the hangmen can be addressed when the payment for hanging stops, or when the work becomes too dangerous. The Bavarian peasants were against every kind of revolution, but when the war went on too long and the sons who came home found no room on their farms, it was possible to win them over to revolution.

It is important for the writer to strike the true note of truth. Ordinarily, what we hear is a very gentle, melancholy tone, the tone of people who would not hurt a fly. Hearing this one, the wretched become more wretched. Those who use it may not be foes, but they are certainly not allies. The truth is belligerent; it strikes out not only against falsehood, but against particular people who spread falsehood.

5. The Cunning to Spread the Truth Among the Many

Many people, proud that they posses the courage necessary for the truth, happy that they have succeeded in finding it, perhaps fatigued by the labor necessary to put it into workable form and impatient that it should be grasped by those whose interests they are espousing, consider it superfluous to apply any special cunning in spreading the truth. For this reason they often sacrifice the whole effectiveness of their work. At all times cunning has been employed to spread the truth, whenever truth was suppressed or concealed. Confucius falsified an old, patriotic historical calendar. He changed certain words. Where the calendar read “The ruler of Hun had the philosopher Wan killed because he said so and so,” Confucius replaced killed by murdered. If the calendar said that tyrant so and so died by assassination, he substituted was executed. In this manner Confucius opened the way for a fresh interpretation of history.

In our times anyone who says population in place of people or race, and privately owned land in place of soil, is by that simple act withdrawing his support from a great many lies. He is taking away from these words their rotten, mystical implications. The word people (Volk) implies a certain unity and certain common interests; it should therefor be used only when we are speaking of a number of peoples, for then alone is anything like community of interest conceivable. The population of a given territory may have a good many different and even opposed interests—and this is a truth that is being suppressed. In like manner, whoever speaks of soil and describes vividly the effect of plowed fields upon nose and eyes, stressing the smell and the color of earth, is supporting the rulers’ lies. For the fertility of the soil is not the question, nor men’s love for the soil, nor their industry in working it; what is of prime importance is the price of grain and the price of labor. Those who extract profits from the soil are not the same people who extract grain from it, and the earthy smell of a turned furrow is unknown on the produce exchanges. The latter have another smell entirely. Privately owned land is the right expressing; it affords less opportunity for deception.

Where oppression exists, the word obedience should be employed instead of discipline, for discipline can be self-imposed and therefore has something noble in its character that obedience lacks. And a better word than honor is human dignity; the latter tends to keep the individual in mind. We all know very well what sort of scoundrels thrust themselves forward, clamoring to defend the honor of a people. And how generously they distribute honors to the starvelings who feed them. Confucius’ sort of cunning is still valid today. Thomas Moore in his Utopia described a country in which just conditions prevailed. It was a country very different from the England in which he lived, but it resembled that England very closely, except for the conditions of life.

Lenin wished to describe exploitation and oppression on Sakhalin Island, but it was necessary for him to beware of the Czarist police. In place of Russia he put Japan, and in place of Sakhalin, Korea. The methods of the Japanese bourgeoisie reminded all his readers of the Russian bourgeoisie and Sakhalin, but the pamphlet was not blamed because Russia was hostile to Japan. Many things that cannot be said in Germany about Germany can be said about Austria.

There are many cunning devices by which a suspicious State can be hoodwinked.

Voltaire combated the Church doctrine of miracles by writing a gallant poem about the Maid of Orleans. He described the miracles that undoubtedly must have taken place in order that Joan of Arc should remain a virgin in the midst of an army of men, a court of aristocrats, and a host of monks. By the elegance of his style, and by describing erotic adventures such as characterized the luxurious life of the ruling class, he threw discredit upon a religion which provided them with the means to pursue a loose life. He even made it possible for his works, in illegal ways, to reach those for whom they were intended. Those among his readers who held power promoted or tolerated the spread of his writings. By so doing, they were withdrawing support from the police who defended their own pleasures. Another example: the great Lucretius expressly says that one of the chief encouragements to the spread of Epicurian atheism was the beauty of his verses.

It is indeed the case that the high literary level of a given statement can afford it protection. Often, however, it also arouses suspicion. In such case it may be necessary to lower it deliberately. This happens, for example, when descriptions of evil conditions are inconspicuously smuggled into the despised form of a detective story. Such descriptions would justify a detective story. The great Shakespeare deliberately lowered the level of his work for reasons of far less importance. In the scene in which Coriolanus’ mother confronts her son, who is departing for his native city, Shakespeare deliberately makes her speech to the son very weak. It was inopportune for Shakespeare to have Coriolanus restrained by good reasons from carrying out his plan; it was necessary to have him yield to old habit with a certain sluggishness.

Shakespeare also provides a model of cunning utilized in the spread of truth: this is Antony’s speech over Caesar’s body. Antony continually emphasizes that Brutus is an honorable man, but he also describes the deed, and this description of the deed is more impressive than the description of the doer. The orator thus permits himself to be overwhelmed by the facts; he lets them speak for themselves.

An Egyptian poet who lived four thousand years ago employed a similar method. That was a time of great class struggles. The class that had hitherto ruled was defending itself with difficulty against its great opponent, that part of the population which had hitherto served it. In the poem a wise man appears at the ruler’s court and calls for struggle against the internal enemy. He presents a long and impressive description of the disorders that have arisen from the uprising of the lower classes. This description reads as follows:

So it is: the nobles lament and the servants rejoice. Every city says: Let us drive the strong from out of our midst. The offices are broken open and the documents removed. The slaves are becoming masters.

So it is: the son of a well-born man can no longer be recognized. The mistress’s child becomes her slave girl’s son.

So it is: The burghers have been bound to the millstones. Those who never saw the day have gone out into the light.

So it is: The ebony poor boxes are being broken up; the noble sesban wood is cut up into beds.

Behold, the capital city has collapsed in an hour.

Behold, the poor of the land have become rich.

Behold, he who had not bread now possesses a barn; his granary is filled with the possessions of another.

Behold, it is good for a man when he may eat his food.

Behold, he who had no corn now possesses barns; those who accepted the largesse of corn now distribute it.

Behold, he who had not a yoke of oxen now possesses herds; he who could not obtain beasts of burden now possesses herds of neat cattle.

Behold, he who could build no hut for himself now possesses four strong walls.

Behold, the ministers seek shelter in the granary, and he who was scarcely permitted to sleep atop the walk now possesses a bed.

Behold, he who could not build himself a rowboat now possesses ships; when their owner looks upon the ships, he finds they are no longer his.

Behold, those who had clothes are now dressed in rags and he who wove nothing for himself now posses the finest linen.

The rich man goes thirsty to bed, and he who once begged him for lees now has strong beer.

Behold, he who understood nothing of music now owns a harp; he to whom no one sang now praises the music.

Behold, he who slept alone for lack of a wife, now has women; those who looked at their faces in the water now possess mirrors.

Behold, the highest in the land run about without finding employment. Nothing is reported to the great any longer. He who once was a messenger now sends forth others to carry his messages…

Behold five men whom their master sent out. They say: go forth yourself; we have arrived.

It is significant that this is the description of a kind of disorder that must seem very desirable to the oppressed. And yet the poet’s intention is not transparent. He expressly condemns these conditions, though he condemns them poorly…

Jonathan Swift, in his famous pamphlet, suggested that the land could be restored to prosperity by slaughtering the children of the poor and selling them for meat. He presented exact calculations showing what economies could be effected if the governing classes stopped at nothing.

Swift feigned innocence. He defended a way of thinking which he hated intensely with a great deal of ardor and thoroughness, taking as his theme a question that plainly exposed to everyone the cruelty of that way of thinking. Anyone could be cleverer than Swift, or at any rate more humane—especially those who had hitherto not troubled to consider what were the logical conclusions of the views they held.

Propaganda that stimulates thinking, in no matter what field, is useful to the cause of the oppressed. Such propaganda is very much needed. Under governments which serve to promote exploitation, thought is considered base.

Anything that serves those who are oppressed is considered base. It is base to be constantly concerned about getting enough to eat; it is base to reject honors offered to the defenders of a country in which those defenders go hungry; base to doubt the Leader when his leadership leads to misfortunes; base to be reluctant to do work that does not feed the worker; base to revolt against the compulsion to commit senseless acts; base to be indifferent to a family which can no longer be helped by any amount of concern. The starving are reviled as voracious wolves who have nothing to defend; those who doubt their oppressors are accused of doubting their own strength; those who demand pay for their labor are denounced as idlers. Under such governments thinking in general is considered base and falls into disrepute. Thinking is no longer taught anywhere, and wherever it does emerge, it is persecuted.

Nevertheless, certain fields always exist in which it is possible to call attention to triumphs of thought without fear of punishment. These are the fields in which the dictatorships have need of thinking. For example, it is possible to refer to the triumphs of thought in fields of military science and technology. Even such matters as stretching wool supplies by proper organization, or inventing ersatz materials, require thinking. Adulteration of foods, training the youth for war—all such things require thinking; and in reference to such matters the process of thought can be described. Praise of war, the automatic goal of such thinking, can be cunningly avoided, and in this way the thought that arises from the question of how a war can best be waged can be made to lead to another question—whether the war has any sense. Thought can then be applied to the further question: how can a senseless war be averted?

Naturally, this question can scarcely be asked openly. Such being the case, cannot the thinking we have stimulated be made use of? That is, can it be framed so that it leads to action? It can.

In order that the oppression of one (the larger) part of the population by another (the smaller) part should continue in such a time as ours, a certain attitude of the population is necessary, and this attitude must pervade all fields. A discovery in the field of zoology, like that of the Englishman Darwin, might suddenly endanger exploitation. And yet, for a time the Church alone was alarmed; the people noticed nothing amiss. The researches of physicists in recent years have led to consequences in the field of logic which might well endanger a number of the dogmas that keep oppression going. Hegel, the philosopher of the Prussian State, who dealt with complex investigations in the field of logic, suggested to Marx and Lenin, the classic exponents of the proletarian revolution, methods of inestimable value.

The development of the sciences is interrelated, but uneven, and the State is never able to keep its eye on everything. The advance guard of truth can select battle positions which are relatively unwatched.

What counts is that the right sort of thinking be taught, a kind of thinking that investigates the transitory and changeable aspect of all things and processes. Rulers have an intense dislike for significant changes. They would like to see everything remain the same—for a thousand years, if possible. They would love it if sun and moon stood still. Then no one would grow hungry any more, no one would want his supper. When the rulers have fired a shot, they do not want the enemy to be able to shoot; theirs must be the last shot. A way of thinking that stresses change is a good way to encourage the oppressed.

Another idea with which the victors can be confronted is that in everything and in every condition, a contradiction appears and grows. Such a view (that of dialectics, of the doctrine that all things flow and change) can be inculcated in realms that for a time escape the notice of the rulers. It can be employed in biology or chemistry, for example. But it can also be indicated by describing the fate of a family, and here too it need not arouse too much attention. The dependence of everything upon many factors which are constantly changing is an idea dangerous to dictators, and this idea can appear in many guises without giving the police anything to put their finger on. A complete description of all the processes and circumstances encountered by a man who opens a tobacco shop can strike a blow against dictatorship. Anyone who reflects upon this will soon see why. Governments which lead the masses into misery must guard against the masses’ thinking about government while they are miserable. Such governments talk a great deal about Fate. It is Fate, not they, which is to blame for all distress. Anyone who investigates the cause of the distress is arrested before he hits on the fact that the government is to blame. But it is possible to offer a general opposition to all this nonsense about Fate; it can be shown that Man’s Fate is made by men.

This is another thing that can be done in various ways. For example, one might tell the story of a peasant farm—a farm in Iceland, let us say. The whole village is talking about the curse that hovers over this farm. One peasant woman threw herself down a well; the peasant owner hanged himself. One day a marriage takes place between the peasant’s son and a girl whose dowry is several acres of good land. The curse seems to lift from the farm. The village is divided in its judgment of the cause of this fortunate turn of events. Some ascribe it to the sunny disposition of the peasant’s young son, others to the new fields which the young wife added to the farm, and which have now made it large enough to provide a livelihood.

But even in a poem which simply describes a landscape something can be achieved, if the things created by men are incorporated into the landscape.

Cunning is necessary to spread the truth.

Summary

The great truth of our time is that our continent is giving way to barbarism because private ownership of the means of production is being maintained by violence. Merely to recognize this truth is not sufficient, but should it not be recognized, no other truth of importance can be discovered. Of what use is it to write something courageous which shows that the condition into which we are falling is barbarous (which is true) if it is not clear why we are falling into this condition? We must say that torture is used in order to preserve property relations. To be sure, when we say this we lose a great many friends who are against torture only because they think property relations can be upheld without torture, which is untrue.

We must tell the truth about the barbarous conditions in our country in order that the thing should be done which will put an end to them—the thing, namely, which will change property relations.

Furthermore, we must tell this truth to those who suffer most from existing property relations and who have the greatest interest in their being changed—the workers and those whom we can induce to be their allies because they too have really no control of the means of production even if they do share in the profits.

And we must proceed cunningly.

All these five difficulties must be overcome at one and the same time, for we cannot discover the truth about barbarous conditions without thinking of those who suffer from them; cannot proceed unless we shake off every trace of cowardice; and when we seek to discern the true state of affairs in regard to those who are ready to use the knowledge we give them, we must also consider the necessity of offering them the truth in such a manner that it will be a weapon in their hands, and at the same time we must do it so cunningly that the enemy will not discover and hinder our offer of the truth.

That is what is required of a writer when he is asked to write the truth.

SOURCE: Brecht, Bertolt. Galileo, edited and with an introduction by Eric Bentley, English version by Charles Laughton (New York, NY: Grove Press, 1966); essay translated by Richard Winston, Appendix A, pp. 133-150. This quote and bibliographic information are from p. 133.

Publication history: “Writing the Truth: Five Difficulties”, translated by Richard Winston, originally published in the United States in Twice A Year (New York), Tenth Anniversary Issue, 1948. The first version of Brecht’s essay was first published in the Pariser Tageblatt, December 12, 1934, under the title “Dichter sollen die Wahrheit schreiben” (“Poets Are to Tell the Truth”). The final version of Brecht’s essay was published in Unsere Zeit (Paris), VIII, Nos. 2/3, April 1935, pp. 23-24. Galileo was previously published by Arvid Englind, 1940; Bertolt Brecht, 1952 (Indiana University Press).

Interrogation of Bertolt Brecht by the House Unamerican Activities Committee

Bertolt Brecht at the ‚House Committee on Un-American Activites’ — A historical document, presented by Eric Bentley: Like Gerhart and Hanns Eisler, also Bertolt Brecht had to answer the questions of the Members of the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HCUA), that was built to opress communist tendencies, which apparently infiltred the american society. After the Second World War and in aftermath of the first big wave of pursuit against communists, the HCUA get propagandistic importance and prepared some legal proceedings against communist expatriates. Hereafter we offer the recording of the interrogation of Bertolt Brecht in octobre 1947. The listeners get an impression of Bertolt Brechts bad, but self-confident spoken English (the exile-friends of Brecht laugh about and learned to like that pronunciation) and also of the trick of Brecht’s answers. The most interesting and surely absurd part of the questioning begins, when Brecht and the questioners quarrel about the interpretation of Brecht’s play »Die Maßnahme« (The Decision). The original recordings are introduced and commented by Eric Bentley. An important and interesting document of communist and anti-communist history.

Source & MP3: http://audioarchiv.blogsport.de/2012/…

“Galileo,” by Bertolt Brecht, directed by Joseph Losey

“If Sharks Were Men,” by Bertolt Brecht

Bertolt Brecht sings 'Lied von der Unzulänglichkeit menschlichen Strebens' (music by Kurt Weill)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FSk3TG5czcg

Traditional Theater versus Brechtian V-Effekt Distanced Theater

DRAMATIC THEATRE

EPIC THEATRE

plot

narrative

implicates the spectator in a stage situation

turns the spectator into an observer, but

wears down his capacity for action

arouses his capacity for action

provides him with sensations

forces him to take decisions

experience

picture of the world

the spectator is involved in something

he is made to face something

suggestion

argument

instinctive feelings are preserved

brought to the point of recognition

the spectator is in the thick of it, shares the experience

the spectator stands outside, studies

the human being is taken for granted

the human being is the object of the inquiry

he is unalterable

he is alterable and able to alter

eyes on the finish

eyes on the course

one scene makes another

each scene for itself

growth

montage

linear development

in curves

evolutionary determinism

jumps

man as a fixed point

man as a process

thought determines being

social being determines thought

feeling

reason

http://www.powells.com/biblio/72-9780809005420-0

July 16, 2014

To Gaza, from Rheim Alkadhi

“Via the agitated sea, I hereby transmit communiques and love letters to your shores, Gaza.”

-Rheim Alkadhi

July 12, 2014

“Greetings from York Valley,” by Arturo Romo-Santillano

Hi Everyone,

I spent some time today walking on York between Avenue 49 and Avenue

56, the experience illuminated. This is a work in progress, something

I wrote because even though I don’t have the language yet to respond

to the situation, I felt I should respond as best as I could.

To use a term I heard first from my friend Sesshu, the US suffers from

“apartheid imagination.” Chipotle, the burrito restaurant, recently

commissioned artists and writers to design a series of beverage cups–

not one of those commissioned was Latino… this is a place that

serves carnitas, burritos, guacamole! All non-whites are routinely

cropped out of the picture by the apartheid imagination. But the

imagination is flexible–the people who are excluded vary. MTV did a

study that found young people generally feel that racism is caused by

acknowledging and talking about race and that racism can be ended by,

in essence, “not caring” about race. In the case of this particular

form of blindness, other markers are used to designate who will be

excluded by the apartheid imagination. In the case of gentrification

in LA, white and non-white are not the only delineations, although

they still seem to dominate. Class and aspiration can also exclude

someone from existing in this imagination. Immigrants are not seen by

the apartheid imagination, working class people, blue collar workers,

and people who don’t aspire to the gentrified/boutique model of

consumption also are cropped out. People interviewed for articles on

gentrification routinely say things like “it’s so great that young

families are now moving into Highland Park.” when they mean to say

that young affluent families are moving into the neighborhood. This is

the result of wrong perceptions, wrong ideas–the apartheid

imagination is crippling to those who use it, destructive and

degrading to those who it means to exclude. The apartheid imagination

also happens to be the frame through which many gentrifiers seem to

define and construct their dreams.

Walking up and down York, I watched the aesthetics of each restaurant

and vintage shop that has been opened in the last 5 or so years. It

felt a little like walking through two different cities at once:

Highland Park, where I spent my early childhood and have spent almost

a decade as an educator, and York Valley, an offshoot of other cities

defined by niche and boutique business projects. The two cities exist

so distinct from one another that I felt like I was walking alongside

an accordion-fold book of which pages had been torn and replaced with

pages from another story, the oscillation between the two was

rhythmic, uneven and disorienting. The aesthetics of the new

businesses were part of this disorienting rhythm.

What is it that makes an aesthetic choice so divisive? What do the

shared aesthetics of these businesses (The York, Ba, Art Grist, Shop

Class, Hermosillo, Cafe de Leche, Town etc.) mean to their owners?

Their customers? The neighborhood? There is an obvious difference

between the “new” businesses and the established businesses in their

style. I think that the aesthetics, like earth tones and neutral paint

jobs, sans serif, vintage or ironic fonts in signage, and a shared

preference for modernist bareness, are signals to shoppers that these

places are going to be expensive to shop in. They also serve as

markers that connect them to the uniformity of this gentrified world

in other communities like Silverlake, Los Feliz etc.

This is important because maybe many people shop to define themselves–

where they shop is who they become. Because shopping is a statement of

who you are in a consumerist culture, you need to choose correctly to

maintain a particular identity. The aesthetics of signage and

decoration let us know which shop to choose.

Because they aim for exclusivity, the aesthetics may also tell certain

people that this store isn’t for them–that it’s too expensive,

doesn’t offer them what they need, or that they might be entering a

social situation where they could be patronized, objectified or

ignored. Maybe they say to us “You are now entering the Apartheid

Imagination”

I think there’s another layer to these aesthetic choices though. In

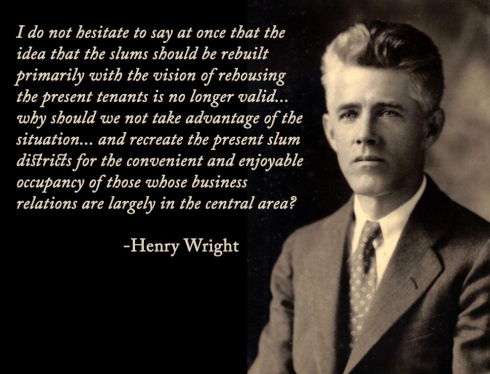

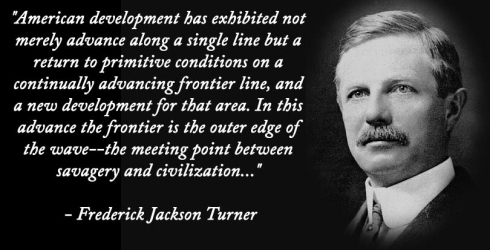

many stories I’ve read about gentrification, frontier or pioneer

themes come up. People who are considered gentrifiers have defined

themselves as “urban pioneers” or will insist that Highland Park was a

cultural “wasteland” before they got there. Or, there will be a

tendency for existing residents to be treated as part of the

landscape, “lots of Mexicans”… This mode of thinking draws from a

deep US mythology of the Frontier, where the frontier is the empty

land full of the promise of progress–increased wealth for the

individual and the nation. In fact, the idea of progress can’t exist

without the frontier in the US imagination. On York, the “frontier”

mythology is put into effect–in this case, the uniformity in look and

services these businesses offer act as clear markers… they’re

crystal clear signals that these businesses are not of or for the

existing community and also that they are part of a larger trend of

“progress” because they share an aesthetic and purpose with other

business across gentrified sectors of the city. Their aesthetics mark

them as outposts on the edge of the “frontier” and also tie them back

to more gentrified areas that where the frontier has been “tamed”.

Now, I don’t think the effects of gentrification are the same as the

effects of the US’ colonization and pillage of America, but the

mythology persists and is operationalized in the process of

gentrification–the mythology is obviously alive and a motivating

factor.

I walked down York and felt sad to see the social topography of

Highland Park split. One set of businesses out of reach for the

majority of its potential and local clientele and broadcasting the

fact out onto the street. It made me feel disheartened that the

apartheid imagination defined York based on the desires of a few

people rather than the needs of the larger community. That consumerist

“business as self expression” has trumped “business as service.” The

proliferation of vintage stores and boutiques that serve as

expressions and advertisements of their owners’ world view wilted me a

little.

My family came to Northeast LA from Mexico and Arizona about three

generations back. There is also a large community of first generation

or immigrants to the Northeast. To me, it’s not as much how long

you’ve been in any one place, but why you came to the place.

Immigrants and working people have moved to the Eastside because it

was designated to them through racist Federal and local laws that

forbade them from moving into “white” communities. A historic,

national rhetoric of violence, and local acts of discrimination,

intimidation and violence reinforced this apartheid system where

Highland Park and more accurately, the industrial Eastside, (like East

LA and Boyle Heights, Lincoln Heights) were created as redlined

ghettos for immigrants and working class people. And though we were

marginalized and routinely pushed out of power, we persisted in place

and built cohesive communities and political presence. We did this in

the face of discrimination and oppression from all levels of

government and mainstream culture. The cities we live in were left

disinvested, abandoned and left unprotected from predatory practices.

Still, art groups formed, civil rights groups made changes, people

worked and survived and built from the core of a community that bases

part of its agency in a specific place.

The threat of gentrification is real because it threatens to disperse

this community cohesion that’s been cultivated over generations by

immigrants and working class people. It threatens our political voice

as working people and people of color because it threatens one of the

things that voice rests on, which is our community cohesion. Whether

we came here in this lifetime or have roots going thousands of years

deep, the power of community is a resource that working people need to

hold on to.

That’s all for now, any thoughts would be great!

—Arturo

revumbio@yahoo.com

www.revumbio.com

Not sure if these links will work:

Apartheid Imagination:

Swirling: http://atomikaztex.wordpress.com/2014...

First mention of it I can find comes from Albie Sachs, in reference to

post-apartheid South Africa http://www.abebooks.com/servlet/BookDetailsPL?bi=10614163030&searchurl=an%3Dalbie%2Bsachs%26amp%3Bkn%3Dspring

Chipotle: http://www.takepart.com/article/2014/05/19/chipotles-short-stories-cups-have-no-latino-authors

Identity in consumerist culture: https://www.adbusters.org/magazine/79/hipster.html

Forbidden White communities:

http://www.theatlantic.com/features/archive/2014/05/the-case-for-reparations/361631/

In a country whose institutions historically fail or deliberately

erase us, community constitutes a central pillar in surviving hetero-

patriarchal white supremacy:

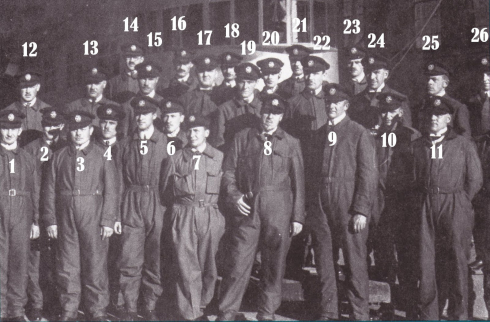

Meet the ELADATL Ground Crew

We are here to serve you! Please do not hesitate to ask for the first thing that crosses your mind! We intend our flights to transcend yellow green tremulations.

1. Swirling “Never Here” Alhambra

2. Tina “The It Girl” Lerma

3. Sergio “Make Him Do it” Tamayo

4. Bobby “Rockero” Diaz

5. Saul “Pedorrero” Osegueda

6. Unknown (tourist probably)

7. Ray “Happy” Palafox

8. Enrique “The Boss” Pico

9. Jose “Mister Jose to You” Lopez-Feliu

10. Monica “Tell Monica to Do it” Barragan

11. Chuy “I’m Outa Here” Koenig

12. Bobby “El Sereno Kid” Loera

13. Bert “Watch Your Elbows” Brecht

14. Kurt “Mack” Weill

15. Horiyuki “Ralph” Tadao

16. Rick “Fawn-Colored” Harsch

17. El “Guero” Lissitsky

18. Masafume “Wild Thing” Goto

19. Harry “Drink This Tequila” Gamboa

20. Muriel “Poet” Rukeyser

21. Bob “I’m a Poet Too!” Kaufman

22. Ralph “Ralph Williams Ford” Williams

23. Cal “Go See Cal” Worthington

24. Roy “The Brother” Palafox

25. Greg “Marlon Brando” Martinez

26. Tiburcio “The Rocks” Vasquez

waking up postcard

i awoke in a white room

unfurnished, but with rugs and scattered clothing, Lisa said we could stay here

semi-disoriented as usual, i go check things out

the next room is dim and green like entering a forest

like the rainforest of southeast alaska (last week), but this is like an art installation

this room is simulacrum or parody of a dim green forest

everything soft, i am trying to make it out

against the far wall, items in rows, on shelves?

what are they, i can’t tell, personal items repurposed or repainted, what do they represent?

some kind of art thing, art idea, I can’t tell exactly what the items are

against a mossy background, plush artificial moss or is it real

like mike kelly junk, what does it mean

a woman (white woman, brunette curly hair, resident i assume) goes by in the periphery of sight, like Emily Barton

(she has sour bird-faced expression like she needs her morning coffee) so there are other people in this apt.

she goes into the kitchen, maybe i should put my clothes on

my clothes are probably in a pile in that first bedroom

i ambulate past cavernous dark room that is probably dining and living area maybe a fireplace at far end

but keep going, where the hell are my pants? enter another bedroom

it’s not that first room i woke up, it’s another bedroom (someone else’s)

a guy, younger white guy like the woman with close-cropped dark hair goes by

shuts a door behind himself looking like Joe Mosconi, he also pays little or no attention to me (sour expression)

meanwhile i’m poking about piles of abandoned clothes in corners

i’ve awoken in gentrified white hipster America and i can’t find my pants

foto by Arturo Romo-Santillano

July 11, 2014

“Letter from Gaza,” by Ghassan Khafani

John Berger reads Ghassan Kanafani’s Letter from Gaza

from http://www.ghassankanafani.com/indexe...

Ghassan Kanafani, the famous Palestinian journalist, novelist, and short story writer, whose writings were deeply rooted in Arab Palestinian culture, inspired a whole generation during and after his lifetime, both in word and deed.He was born in Acre in the North of Palestine on 9th April 1936 and lived in Jaffa until May 1948, when he was forced to leave with family first to Lebanon and later to Syria. He lived and worked in Damascus, then Kuwait and later in Beirut from 1960 onwards. In July 1972, he and his young niece Lamis were killed by Israeli agents in a car bomb explosion in Beirut.

By the time of his untimely death, Ghassan had published eighteen books and written hundreds of articles on culture, politics, and the Palestinian people’s struggle. Following his assassination, all his books were re-published in several editions in Arabic. His novels, short stories, plays and essays were also collected and published in four volumes. Many of Ghassan’s literary works have been translated into seventeen languages and published in more than twenty different countries. Some have been adapted for radio plays and theatrical performances in several Arab and foreign countries. Two of his novels were adapted for the screen and turned into feature films. His literary works written between 1956 and 1972 are as important today as they were then. Although Ghassan’s novels, short stories and most of his other literary work were an expression of the Palestinian people and their cause, yet his great literary talents gave his works a universal appeal.

“Children are on future”, Ghassan often said. He wrote many stories in which children are the heroes. A collection of his short stories was published in Beirut, in 1978, under the title “Ghassan Kanafani’s Children”. The English translation, first published in 1984 and republished in 2000, was entitled “Palestine’s Children”.

Letter from Gaza

I have now received your letter, in which you tell me that you’ve done everything necessary to enable me to stay with you in Sacramento. I’ve also received news that I have been accepted in the department of Civil Engineering in the University of California. I must thank you for everything, my friend. But it’ll strike you as rather odd when I proclaim this news to you — and make no doubt about it, I feel no hesitation at all, in fact I am pretty well positive that I have never seen things so clearly as I do now. No, my friend, I have changed my mind. I won’t follow you to “the land where there is greenery, water and lovely faces” as you wrote. No, I’ll stay here, and I won’t ever leave.

I am really upset that our lives won’t continue to follow the same course, Mustafa. For I can almost hear you reminding me of our vow to go on together, and of the way we used to shout: “We’ll get rich!” But there’s nothing I can do, my friend. Yes, I still remember the day when I stood in the hall of Cairo airport, pressing your hand and staring at the frenzied motor. At that moment everything was rotating in time with the ear-splitting motor, and you stood in front of me, your round face silent.

Your face hadn’t changed from the way it used to be when you were growing up in the Shajiya quarter of Gaza, apart from those slight wrinkles. We grew up together, understanding each other completely and we promised to go on together till the end. But…

“There’s a quarter of an hour left before the plane takes off. Don’t look into space like that. Listen! You’ll go to Kuwait next year, and you’ll save enough from your salary to uproot you from Gaza and transplant you to California. We started off together and we must carry on. . .”

At that moment I was watching your rapidly moving lips. That was always your manner of speaking, without commas or full stops. But in an obscure way I felt that you were not completely happy with your flight. You couldn’t give three good reasons for it. I too suffered from this wrench, but the clearest thought was: why don’t we abandon this Gaza and flee? Why don’t we? Your situation had begun to improve, however. The ministry of Education in Kuwait had given you a contract though it hadn’t given me one. In the trough of misery where I existed you sent me small sums of money. You wanted me to consider them as loans. because you feared that I would feel slighted. You knew my family circumstances in and out; you knew that my meagre salary in the UNRWA schools was inadequate to support my mother, my brother’s widow and her four children.

“Listen carefully. Write to me every day… every hour… every minute! The plane’s just leaving. Farewell! Or rather, till we meet again!”

Your cold lips brushed my cheek, you turned your face away from me towards the plane, and when you looked at me again I could see your tears.

Later the Ministry of Education in Kuwait gave me a contract. There’s no need to repeat to you how my life there went in detail. I always wrote to you about everything. My life there had a gluey, vacuous quality as though I were a small oyster, lost in oppressive loneliness, slowly struggling with a future as dark as the beginning of the night, caught in a rotten routine, a spewed-out combat with time. Everything was hot and sticky. There was a slipperiness to my whole life, it was all a hankering for the end of the month.

In the middle of the year, that year, the Jews bombarded the central district of Sabha and attacked Gaza, our Gaza, with bombs and flame-throwers. That event might have made some change in my routine, but there was nothing for me to take much notice of; I was going to leave. this Gaza behind me and go to California where I would live for myself, my own self which had suffered so long. I hated Gaza and its inhabitants. Everything in the amputated town reminded me of failed pictures painted in grey by a sick man. Yes, I would send my mother and my brother’s widow and her children a meagre sum to help them to live, but I would liberate myself from this last tie too, there in green California, far from the reek of defeat which for seven years had filled my nostrils. The sympathy which bound me to my brother’s children, their mother and mine would never be enough to justify my tragedy in taking this perpendicular dive. It mustn’t drag me any further down than it already had. I must flee!

You know these feelings, Mustafa, because you’ve really experienced them. What is this ill-defined tie we had with Gaza which blunted our enthusiasm for flight? Why didn’t we analyse the matter in such away as to give it a clear meaning? Why didn’t we leave this defeat with its wounds behind us and move on to a brighter future which would give us deeper consolation? Why? We didn’t exactly know.

When I went on holiday in June and assembled all my possessions, longing for the sweet departure, the start towards those little things which give life a nice, bright meaning, I found Gaza just as I had known it, closed like the introverted lining of a rusted snail-shell thrown up by the waves on the sticky, sandy shore by the slaughter-house. This Gaza was more cramped than the mind of a sleeper in the throes of a fearful nightmare, with its narrow streets which had their bulging balconies…this Gaza! But what are the obscure causes that draw a man to his family, his house, his memories, as a spring draws a small flock of mountain goats? I don’t know. All I know is that I went to my mother in our house that morning. When I arrived my late brother’s wife met me there and asked me,weeping, if I would do as her wounded daughter, Nadia, in Gaza hospital wished and visit her that evening. Do you know Nadia, my brother’s beautiful thirteen-year-old daughter?

That evening I bought a pound of apples and set out for the hospital to visit Nadia. I knew that there was something about it that my mother and my sister-in-law were hiding from me, something which their tongues could not utter, something strange which I could not put my finger on. I loved Nadia from habit, the same habit that made me love all that generation which had been so brought up on defeat and displacement that it had come to think that a happy life was a kind of social deviation.

What happened at that moment? I don’t know. I entered the white room very calm. Ill children have something of saintliness, and how much more so if the child is ill as result of cruel, painful wounds. Nadia was lying on her bed, her back propped up on a big pillow over which her hair was spread like a thick pelt. There was profound silence in her wide eyes and a tear always shining in the depths of her black pupils. Her face was calm and still but eloquent as the face of a tortured prophet might be. Nadia was still a child, but she seemed more than a child, much more, and older than a child, much older.

“Nadia!”

I’ve no idea whether I was the one who said it, or whether it was someone else behind me. But she raised her eyes to me and I felt them dissolve me like a piece of sugar that had fallen into a hot cup of tea. ‘

Together with her slight smile I heard her voice. “Uncle! Have you just come from Kuwait?”

Her voice broke in her throat, and she raised herself with the help of her hands and stretched out her neck towards me. I patted her back and sat down near her.

“Nadia! I’ve brought you presents from Kuwait, lots of presents. I’ll wait till you can leave your bed, completely well and healed, and you’ll come to my house and I’ll give them to you. I’ve bought you the red trousers you wrote and asked me for. Yes, I’ve bought them.”

It was a lie, born of the tense situation, but as I uttered it I felt that I was speaking the truth for the first time. Nadia trembled as though she had an electric shock and lowered her head in a terrible silence. I felt her tears wetting the back of my hand.

“Say something, Nadia! Don’t you want the red trousers?” She lifted her gaze to me and made as if to speak, but then she stopped, gritted her teeth and I heard her voice again, coming from faraway.

“Uncle!”

She stretched out her hand, lifted the white coverlet with her fingers and pointed to her leg, amputated from the top of the thigh.

My friend … Never shall I forget Nadia’s leg, amputated from the top of the thigh. No! Nor shall I forget the grief which had moulded her face and merged into its traits for ever. I went out of the hospital in Gaza that day, my hand clutched in silent derision on the two pounds I had brought with me to give Nadia. The blazing sun filled the streets with the colour of blood. And Gaza was brand new, Mustafa! You and I never saw it like this. The stone piled up at the beginning of the Shajiya quarter where we lived had a meaning, and they seemed to have been put there for no other reason but to explain it. This Gaza in which we had lived and with whose good people we had spent seven years of defeat was something new. It seemed to me just a beginning. I don’t know why I thought it was just a beginning. I imagined that the main street that I walked along on the way back home was only the beginning of a long, long road leading to Safad. Everything in this Gaza throbbed with sadness which was not confined to weeping. It was a challenge: more than that it was something like reclamation of the amputated leg!

I went out into the streets of Gaza, streets filled with blinding sunlight. They told me that Nadia had lost her leg when she threw herself on top of her little brothers and sisters to protect them from the bombs and flames that had fastened their claws into the house. Nadia could have saved herself, she could have run away, rescued her leg. But she didn’t.

Why?

No, my friend, I won’t come to Sacramento, and I’ve no regrets. No, and nor will I finish what we began together in childhood. This obscure feeling that you had as you left Gaza, this small feeling must grow into a giant deep within you. It must expand, you must seek it in order to find yourself, here among the ugly debris of defeat.

I won’t come to you. But you, return to us! Come back, to learn from Nadia’s leg, amputated from the top of the thigh, what life is and what existence is worth.

Come back, my friend! We are all waiting for you.

what is to be done?

the israelis started bombing again, first 6 dead, then 21 dead, 23 more, lately it’s over 100 killed— a quarter of them children. 400 tons of bombs. it goes on.

jay asked, “what is to be done?”

obviously an important question, a good and useful question. not that we should only be reactive, but that some issues should have been acted on before they got to this point. probably, the question itself recognizes, in the asking of it, our position of relative weakness, by which i mean isolation.

I said, “at the very least, talk one on one.”

i know some are thinking that their previous condition, their difficulties and defeats make it impossible for them to act. “i can’t even deal with my own problems, let alone somebody else’s,” someone said when i suggested they try to get out and do something.

but not to act on an issue like this, or on similar pressing issues, is to acquiesce to our own isolation, to reinforce our past difficulties and defeats represented by that isolation.

so the first thing is, to talk one on one.

and the second is, why are you not part of some group or organization that will help you, stand up for you, fight for you?