Sesshu Foster's Blog, page 9

June 25, 2015

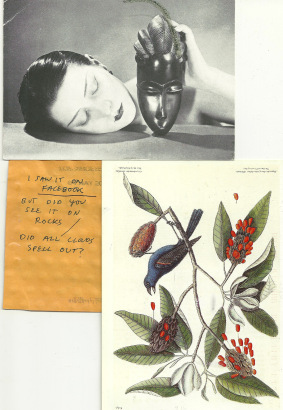

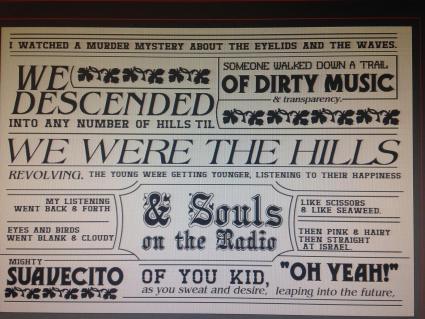

i like you postcards

i like you, so here are your instructions:

rattlesnake grass, yucca, prickly pear

interiors illuminated by lightning, structures and ridge lines seen from the back

the hard part is not the fight, the hard part is to get to the fight, to find it

the hard part is not losing, the hard part is to find out how to get into the fight

the hard part is not having lost, the hard part is being side-lined out of the fight forever

how does your blood taste this time

how is the wind this morning

for now we shall forget some of that other shit

memory of rain on wood, rain on tin

i like you, i said to myself

June 15, 2015

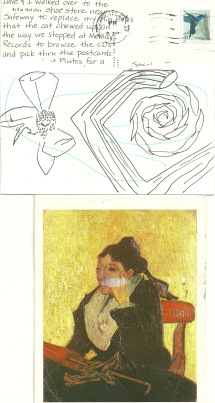

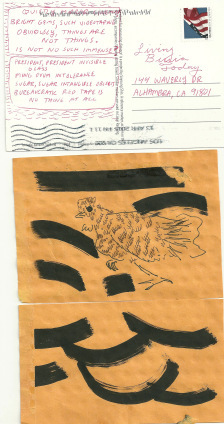

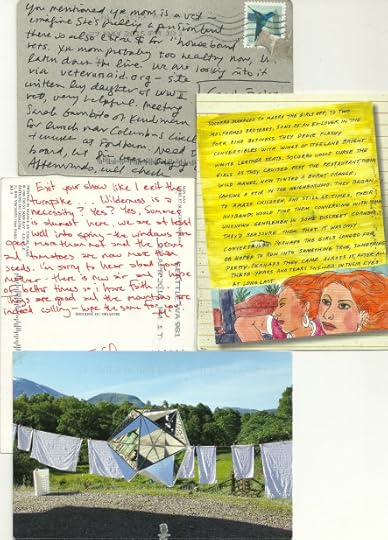

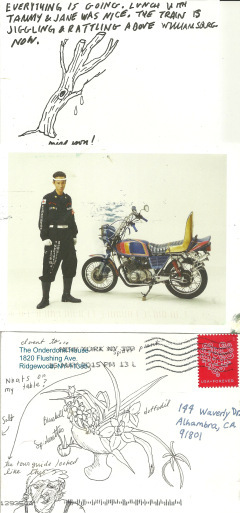

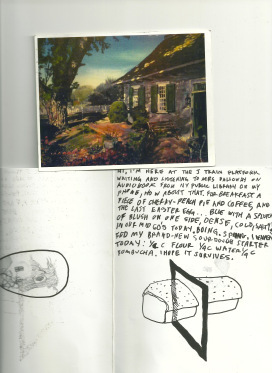

June Postcards

June 14, 2015

Another Portrait of Dad

I saw dad sitting on the porch of the rooming house on 6th Street, San Jose. Leaning back in a ratty chair with a tall can in his hand, he hadn’t shaved or cut his hair in months. I saw him before he saw me, staring off at a distant point. When he fixed on my face as I crossed the yellow lawn, he recognized me and grinned.

I saw Mario Ybarra standing in the center line of Sunset Boulevard at dusk, between lines of streaming traffic. I yelled “Hey Mario!” driving by, but I don’t think he heard me.

I saw Selene Santiago at the Alhambra farmers market, and when I turned around, she was gone.

In a warm summer drizzle in Manhattan, somebody said, “I heard someone call out your name.” I stepped off the corner at the corner of 5th and 34th and looked up and down the avenue between skyscrapers at the crowd emerging through corridors of plywood and scaffolding, flowing across the intersection in four directions, but I recognized no one.

At the Public Theater in Manhattan, on my way to see Roger Guenver Smith’s solo play, “A Huey P. Newton Story,” I got in the elevator and Roger entered. “Hey Roger,” I said, and he said, “How are you?”

Jimmy Lew had been a runner in hike school, and now on the trail to Vernal Falls at dawn in the Yosemite Valley, he rushed ahead of me. I hurried to keep up, breathing hard, lungs aching in the frozen air, trying to keep him in sight as he zigzagged the icy trail above.

My brother told me that the last time he saw Zeus Gaytan, he was on TV, wearing the blue helmet of a UN peace keeper in Bosnia. The last time I saw him was in the 1980s, in the Japanese garden on the rooftop of the New Otani Hotel, talking about people we never saw.

I had the wife and kids in the pickup truck; we’d visited one of my wife’s college friends who was working as a public defender in San Jose, and then drove downtown to 6th Street, where my father lived in a rooming house. He didn’t have a phone. He didn’t know we were in town. One of the boarders whose name was maybe Kevin (he’d mentioned other boarders in his frequent letters) said my father was out, but that he’d tell him we had come by. My wife said maybe we could return to see if he was in later. As we turned to get back in the truck, my father crossed the street and met us. He was drunk and looked like he hadn’t slept at home in days. In fact, he said he’d spent the week “across town with the Indians.” I could see him trying to shake off the drunkenness, to get a grip on himself internally. “Just a minute,” he said, walking over to vomit into the shrubbery. “Are you all right?” I asked. “I just need a cup of coffee,” he said. And it was true. He heated coffee on the stove in a tiny kitchen, drank two cups, and was ready to meet his grandchildren.

I saw Harry Gamboa in the Starbucks in the Fremont Ave. Alhambra Starbucks; as I entered, he saw me and rose to say hello. I saw Harry in the Mexico City Starbucks off the zocalo.

Dad grew angry when we said we all had to be quiet because the kids were going to bed. “I’ve never been treated so badly in my life!” he exclaimed, as he stalked down the stairs and away through the trees, a twelve pack in a sack under his arm.

The first time I saw Lawrence Ferlinghetti, I was walking toward City Lights Bookstore and saw him arranging books in the window.

I saw Rick Harsch sitting on my balcony, smoking and drinking a beer. He emitted smoke anxiously like my brother.

I saw a raven clucking and burbling in a tree in the Yosemite Creek Campground. Later, maybe it was the same one, the raven was taking a dust bath in the dirt road.

I saw Ernesto Cardenal under the eves of the fairgrounds in Managua where we went for the First International Nicaraguan Book Fair. The U.S. booth consisted of a consortium of small presses, including Children’s Book Press of San Francisco, Calyx Press of Oregon, Curbstone Press of Connecticut, and West End Press of Albuquerque. The Cubans and Mexico had big booths the next aisle over. Across the aisle, facing the U.S. stall and its improvised shelves and tables, were the Iranians with their giant laminated photographs of dead torture victims of the U.S.-supported-SAVAK strung like sheets on a clothes line next door to the North Koreans, with their immaculate white booth housing one shelf of books, the collected works of Kim Il-sung, underneath his smiling portrait. Sandinista Minister of Culture Cardenal toured the stalls, saying hello. I thanked him for hosting us, and especially for his own poetry, which I said was crucially important to me. Later I met Cardenal’s British translator, who said his books only sold a few hundred copies in the U.S.

Out on the flat Sea of Cortez, the broad back of the whale (a blue whale) broke the surface like the inverted black steel hull of a ship underwater, black and smooth and shining, with a kind of nub on the crest line down the center as it arched its back and swam on.

I saw Carlo Pedace sitting on my sister’s back porch, smoking. We’d first met Carlo in Naples in 1978, and now his hair was gray, but he looked good. He looked like he was waiting.

I saw my grandmother Alberta Northway sitting on her couch alone in her apartment in Santa Barbara.

In line at airport in Philadelphia, I saw my co-worker (Doctor) Joe Cocozza enter the line behind me. He introduced me to his partner.

I saw him at the table of professors with Karen Yamashita. I had walked into the cafe looking for lunch, and when Robert Allen started talking about the Port Chicago explosion and mutiny, I told him, “Robert, we met in Nicaragua more than twenty years ago,” and we laughed and hugged. He had talked about the 1944 Port Chicago explosion and mutiny case in Nicaragua twenty years earlier. “I learned about Port Chicago from you,” I said, “In fact, you’re the only person I’ve ever heard talk about it.”

I saw Willie Herron walking down the long hill on Eastern Avenue by the Dolores Canning Company, toward Floral.

I saw the yucca spike was a light golden blonde, its seed pods rattling like ear rings, halfway between the heavy reptilian green of its emergence and the last blasted desiccated hollow black stalk it would become.

Another Portrait of My Dad

I saw Mario Ybarra standing in the center line of Sunset Boulevard at dusk, between lines of streaming traffic. I yelled “Hay Mario!” driving by, but I don’t think he heard me.

I saw Selene Santiago at the Alhambra farmers market, and when I turned around, she was gone.

In a warm summer drizzle in Manhattan, somebody said, “I heard someone call out your name.” I stepped off the corner at the corner of 5th and 34th and looked up and down the avenue between skyscrapers at the crowd emerging through corridors of plywood and scaffolding, flowing across the intersection in four directions, but I recognized no one.

At the Public Theater in Manhattan, on my way to see Roger Guenver Smith’s solo play, “A Huey P. Newton Story,” I got in the elevator and Roger entered. “Hey Roger,” I said, and he said, “How are you?”

Jimmy Lew had been a runner in hike school, and now on the trail to Vernal Falls at dawn in the Yosemite Valley, he rushed ahead of me. I hurried to keep up, breathing hard, lungs aching in the frozen air, trying to keep him in sight as he zigzagged the icy trail above.

My brother told me that the last time he saw Zeus Gaytan, he was on TV, wearing the blue helmet of a UN peace keeper in Bosnia. The last time I saw him was in the 1980s, in the Japanese garden on the rooftop of the New Otani Hotel, talking about people we never saw.

I had the wife and kids in the pickup truck; we’d visited one of my wife’s college friends who was working as a public defender in San Jose, and then drove downtown to 6th Street, where my father lived in a rooming house. He didn’t have a phone. He didn’t know we were in town. One of the boarders whose name was maybe Kevin (he’d mentioned other boarders in his frequent letters) said my father was out, but that he’d tell him we had come by. My wife said maybe we could return to see if he was in later. As we turned to get back in the truck, my father crossed the street and met us. He was drunk and looked like he hadn’t slept at home in days. In fact, he said he’d spent the week “across town with the Indians.” I could see him trying to shake off the drunkenness, to get a grip on himself internally. “Just a minute,” he said, walking over to vomit into the shrubbery. “Are you all right?” I asked. “I just need a cup of coffee,” he said. And it was true. He heated coffee on the stove in a tiny kitchen, drank two cups, and was ready to meet his grandchildren.

I saw Harry Gamboa in the Starbucks in the Fremont Ave. Alhambra Starbucks; as I entered, he saw me and rose to say hello. I saw Harry in the Mexico City Starbucks off the zocalo.

Dad grew angry when we said we all had to be quiet because the kids were going to bed. “I’ve never been treated so badly in my life!” he exclaimed, as he stalked down the stairs and away through the trees, a twelve pack in a sack under his arm.

The first time I saw Lawrence Ferlinghetti, I was walking toward City Lights Bookstore and saw him arranging books in the window.

I saw Rick Harsch sitting on my balcony, smoking and drinking a beer. He emitted smoke anxiously like my brother.

I saw a raven clucking and burbling in a tree in the Yosemite Creek Campground. Later, maybe it was the same one, the raven was taking a dust bath in the dirt road.

I saw Ernesto Cardenal under the eves of the fairgrounds in Managua where we went for the First International Nicaraguan Book Fair. The U.S. booth consisted of a consortium of small presses, including Children’s Book Press of San Francisco, Calyx Press of Oregon, Curbstone Press of Connecticut, and West End Press of Albuquerque. The Cubans and Mexico had big booths the next aisle over. Across the aisle, facing the U.S. stall and its improvised shelves and tables, were the Iranians with their giant laminated photographs of dead torture victims of the U.S.-supported-SAVAK strung like sheets on a clothes line next door to the North Koreans, with their immaculate white booth housing one shelf of books, the collected works of Kim Il-sung, underneath his smiling portrait. Sandinista Minister of Culture Cardenal toured the stalls, saying hello. I thanked him for hosting us, and especially for his own poetry, which I said was crucially important to me. Later I met Cardenal’s British translator, who said his books only sold a few hundred copies in the U.S.

Out on the flat Sea of Cortez, the broad back of the whale (a blue whale) broke the surface like the inverted black steel hull of a ship underwater, black and smooth and shining, with a kind of nub on the crest line down the center as it arched its back and swam on.

I saw Carlo Pedace sitting on my sister’s back porch, smoking. We’d first met Carlo in Naples in 1978, and now his hair was gray, but he looked good. He looked like he was waiting.

I saw my grandmother Alberta Northway sitting on her couch alone in her apartment in Santa Barbara.

In line at airport in Philadelphia, I saw my co-worker (Doctor) Joe Cocozza enter the line behind me. He introduced me to his partner.

I saw him at the table of professors with Karen Yamashita. I had walked into the cafe looking for lunch, and when Robert Allen started talking about the Port Chicago explosion and mutiny, I told him, “Robert, we met in Nicaragua more than twenty years ago,” and we laughed and hugged. He had talked about the 1944 Port Chicago explosion and mutiny case in Nicaragua twenty years earlier. “I learned about Port Chicago from you,” I said, “In fact, you’re the only person I’ve ever heard talk about it.”

I saw Willie Herron walking down the long hill on Eastern Avenue by the Dolores Canning Company, toward Floral.

I saw the yucca spike was a light golden blonde, its seed pods rattling like ear rings, halfway between the heavy reptilian green of its emergence and the last blasted desiccated hollow black stalk it would become.

June 13, 2015

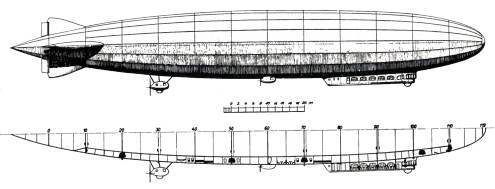

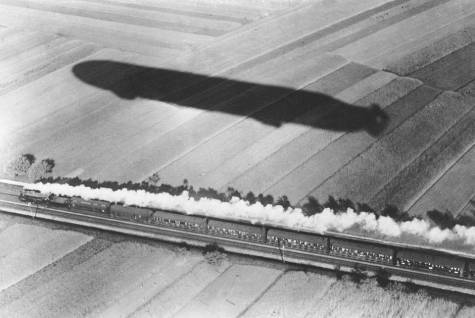

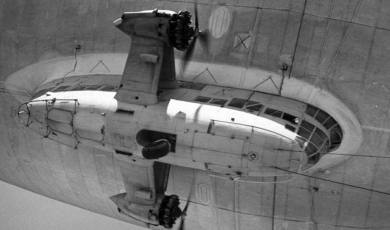

Proposed Minutes for the Next Meetin g of the East L.A. Balloon Club

we will meet in our office space (to be determined, it has to look real)

we will reconstitute the constitution and reogranize this organization

we will have applications for those who wish to join

we will recognize natural leaders

we will takes notes on stuff that people want done

we will have some sort of agenda like this

we will have music of avant garde noise

we will have food and drinks and refreshments for people

we will have posters and stationary of the organization

we will have sunshine coming through the windows

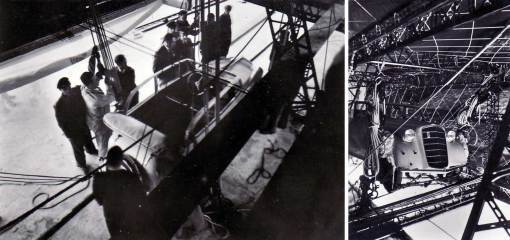

we will have screenings of films of the East Los Angeles Dirigible Air Transport Lines

we will have poets or writers read work related to the air

we will make it official

we will have an agenda and stuff

soon

June 11, 2015

Thoughts on Juan Felipe Herrera for Mike Sonksen

I met Juan Felipe Herrera around 1988. Ruben Martinez, Lindsey Haley and I drove to San Jose in my little white pickup truck to participate in a Flor y Canto commemoration of the series of floricantos that took place throughout the 70’s. Flor y Cantos were Chicano literary festivals JFH participated in with heavy hitters of the day, like JFH’s former roommate Alurista, Oscar Zeta Acosta, Jose Montoya, raulrsalinas, and that whole first wave of Chicano writers (of whom JFH is sort of like a champion, because he’s the LAST ONE STANDING). Ruben and Lindsey were invited to participate in the Flor y Canto and I went along as their driver. We drove to San Jose where JFH had a house with his partner, the poet Margarita Luna Robles and their kids. We participated in Flor y Canto readings at Casa Zapata at Stanford, where both JFH and my wife had gone to college. Afterwards we went to JFH’s backyard with JFH grilling green onions, nopales and chiles and passing them out in tortillas to everybody, exclaiming about the importance of Nino Rota’s music for Fellini movies. He played selected tracks for us on a boombox, while we listened intently. We’d driven 300 miles north for this, both Ruben and I busy in L.A.’s Central American solidarity movement. Ruben shook his head later, asking me, what do you make of all this? I don’t know where Ruben and Lindsey went, but I ended up going with JFH to his son’s soccer game, and that night I slept in the back of my pickup across the street in the camper shell. The next day I wandered into the house a little stiff and groggy—but apparently I’d brought a cassette recorder, so I interviewed JFH while he drove to San Francisco, which took maybe an hour or so in a green and white lowrider classic car straight out of a Frank Romero painting, plying JFH with all the questions I could think of about Chicano literary history.

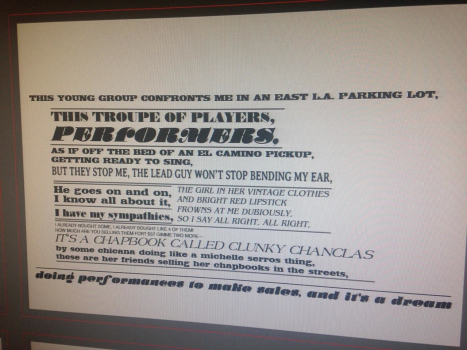

In 1988, it seemed totally possible that this generation of great Chicano writers would pass by unpublished or unknown, just like the generation of outstanding Chicano movement muralists. In the 1980s, no corporate New York presses published Chicanos. First Maxine Hong Kingston and then Sandra Cisneros a few years later would break through that wall, open up the whole U.S. market. But in 1988, it seemed likely that a whole generation of West Coast writers of color like Jessica Hagedorn, Alejandro Murguia, Lorna Dee Cervantes, Omar Salinas, Jeff Tagami, Ntozake Shange, Cherrie Moraga and Ana Castillo would only be known by the rest of us in small circles, like friends, with their books published by tiny presses in small editions, like Lorna Dee Cervantes’s Mango Press or Ernesto Padilla’s Lalo Press, which published JFH’s atomic hand grenade of a book, Exiles of Desire, as well as the first edition of Michelle Serros’s Chicana Falsa, which started her career. Who has ever seen a copy of JFH’s Exiles of Desire? Why not? It’s such a brilliant book, the literary equivalent to Asco’s work in Los Angeles at the same time. Why were those editions limited to a few hundred copies sold out of City Lights Bookstore in San Francisco or Midnight Special Bookstore in Santa Monica or Bookworks in Albuquerque. In those days, who knew any of those books, those presses, or those writers but a few of us? So many voices went unheard, so many lives were silenced, and outside of outposts like Ishmael Reed’s Yardbird, there was no certainty that “multicultural” literature would be allowed to live. In the interview with JFH I asked him about all those literary scenes from Austin to Fresno, from the Taos Poetry Circus and the Bisbee Poetry Festival, from Barrio Logan to the Mission District. JFH was a mover and shaker everywhere he went; he knew about all those scenes; he’d performed with Culture Clash and teatros, on pyramids and stages in Mexico, coffee shops and college campuses across the U.S. for hipsters and Chipsters, pochos and campesinos, for anyone and everyone.

For me, that’s one of the beautiful, essential things about JFH. That’s why he’s a master. Poets like JFH are senseis for the rest of us writers. JFH will bring the poetry to anyone. He will lay it at the feet of everyone. When I met him, JFH was teaching poetry in Soledad prison. We drove past it on highway 101, and he talked about what he did there. He didn’t tell the prisoners, you’re a convict, you’re despised and feared—no poetry for you. He ran the same writing exercises he used with college students. He is not going to say, what, you’re a little kid? No poetry for you. He didn’t say, you’re a farmworker from Oaxaca, barely speak Spanish? No poetry for you. You’re a woman who works day and night, trying to keep your family alive? No time for poetry. You’re from a lost generation, a lame suburb, some mysterious fate? No poetry for you. No! You might be a ghost, a spirit, a raven, a nahual, some unformed being not yet emerged from the air. JFH still has a poem for you! JFH will bring it. Look at JFH’s books. Spanish, English, poetry, prose, novellas in verse, children’s books, memoirs, young adult books, performance pieces, articles, interviews, JFH went there! He does not say, here’s my poem, I don’t know who you are but maybe if you can rise to it, you might be able to read it. Instead, he gets out there, he hits the road, he shatters his own poetry into dust and puts the powder in a little paper sack or a folded paper; he takes it to people wherever they are and says, “This is ours—this is our poem we’re making.” He’s not theorizing a democratic poetics, the political poetry of a public intellectual. He’s doing it; he’s been doing it for forty years. He’s a sensei.

June 1, 2015

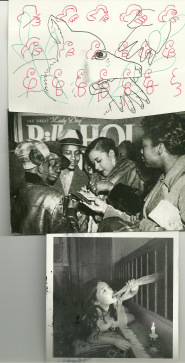

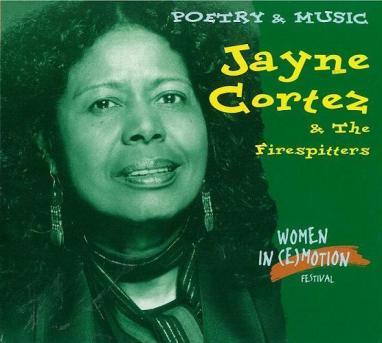

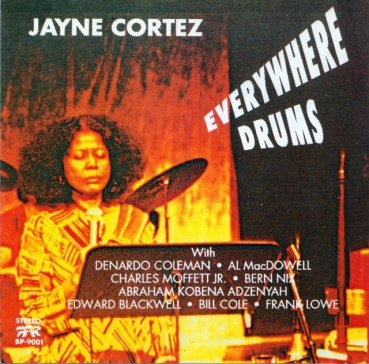

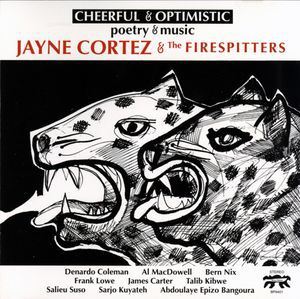

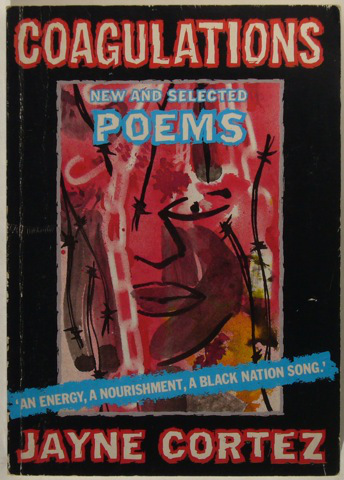

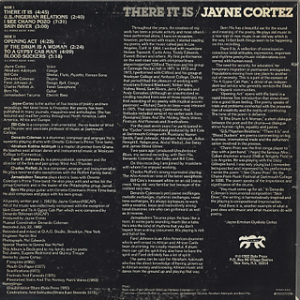

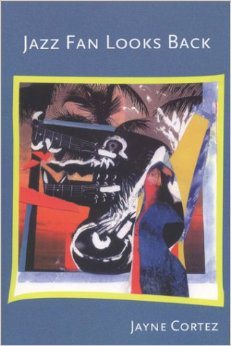

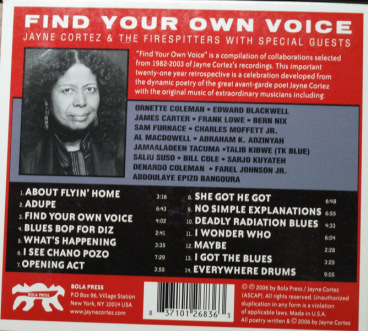

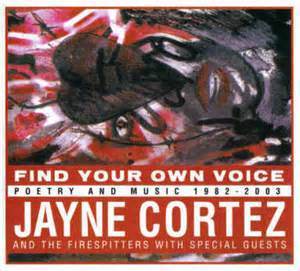

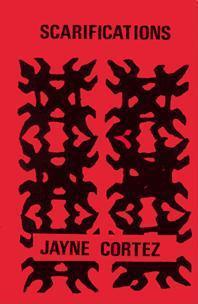

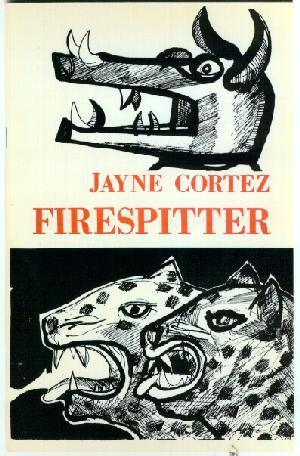

Jayne Cortez & the Firespitters

There It Is

My friend

they don’t care

if you’re an individualist

a leftist a rightist

a shithead or a snake

They will try to exploit you

absorb you confine you

disconnect you isolate you

or kill you

And you will disappear into your own rage

into your own insanity

into your own poverty

into a word a phrase a slogan a cartoon

and then ashes

The ruling class will tell you that

there is no ruling class

as they organize their liberal supporters into

white supremist lynch mobs

organize their children into

ku klux klan gangs

organize their police into killer cops

organize their propaganda into

a devise to ossify us with angel dust

pre-occupy us with western symbols in

african hair styles

inoculate us with hate

institutionalize us with ignorance

hypnotize us with a monotonous sound designed

to make us evade reality and stomp our lives away

And we are programmed to self destruct

to fragment

to get buried under covert intelligence operations of

unintelligent committees impulsed toward death

And there it is

The enemies polishing their penises between

oil wells at the pentagon

the bulldozers leaping into demolition dances

the old folks dying of starvation

the informers wearing out shoes looking for crumbs

the lifeblood of the earth almost dead in

the greedy mouth of imperialism

And my friend

they don’t care

if you’re an individualist

a leftist a rightist

a shithead or a snake

They will spray you with

a virus of legionnaire’s disease

fill your nostrils with

the swine flu of their arrogance

stuff your body into a tampon of

toxic shock syndrome

try to pump all the resources of the world

into their own veins

and fly off into the wild blue yonder to

pollute another planet

And if we don’t fight

if we don’t resist

if we don’t organize and unify and

get the power to control our own lives

Then we will wear

the exaggerated look of captivity

the stylized look of submission

the bizarre look of suicide

the dehumanized look of fear

and the decomposed look of repression

forever and ever and ever

And there it is

Death Poem

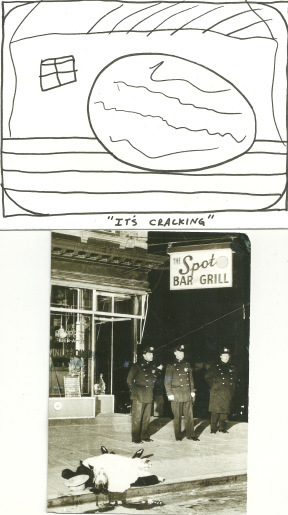

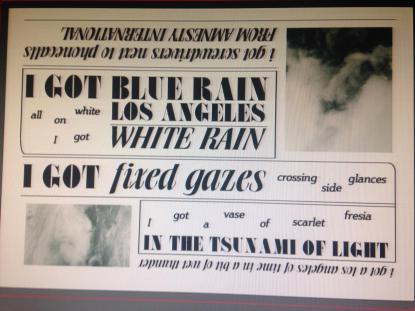

What killed the dirigible and the electric car?

Death came in the form of the internal combustion engine on fire on the freeway.

What killed the pay telephone outside the liquor store?

Death was little screens that lit up a million faces like a Roosevelt dime.

What killed the passenger pigeon and the California grizzly?

Death arrived in the form of guns that massacred imagination.

What killed Japanese American towns such as Crystal Cove and Terminal Island Furusato?

Death was delivered by the Western Growers Protective Association, http://www.wga.com/about.

What killed California and the United States of America?

Death, death killed them, in the form of red demon of Wall Street and the blue demon of Hollywood.

May 25, 2015

Happy Memorial Day 2015

I remember those who stood for peace and fought for peace—when they go their lives stand still like trees.

Don White 1937 – 2008

http://www.walterlippmann.com/donwhite.html

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RGg5g3NSlTM

Michael Zinzun 1949 – 2006

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Michael_Zinzun

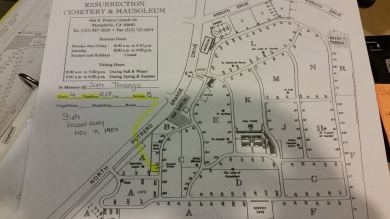

Sixto Tarango 1957 – 1987

Dennis Brutus 1924 – 2009

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dennis_Brutus

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lNAfhW_kzn0

Chris Hani 1942 – 1993

http://www.sacp.org.za/main.php?ID=2294

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NGKhN2BL1-U

Iqbal Masih 1983 – 1995

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Iqbal_Masih

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3tYKFV8UUAo

Bob Kaufman 1925 – 1986

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bob_Kaufman

https://atomikaztex.wordpress.com/2015/04/25/bob-kaufman/

https://atomikaztex.wordpress.com/2014/08/11/plea-by-bob-kaufman/

Reine Moffett (died 1997)

May 19, 2015

Q & A Postcard

Where did I put it? Can I get there across the untethered plank? How old are the planks of the rotting walkway, leading up from the dock (with the sunken yacht, bridge black with mold)? How wide is this island? How parenthetical is one last appositive? How is it I feel the shadow cutting silent across the mudflat, cutting across the flat green water? How does the deep opacity of green refract blades of sunglare into my useless old thoughts? How about these nails sticking out? How about the rocks in the mudflats, the moss in the trees? How shall I fall through the next fifteen minutes? How to drop down through the hole rotten in the deck to the pilings underneath, thence to proceed across the rocks, slippery below? How to find out the overgrown trails they had to have used? How about the shiny commercial mixer on the counter of the abandoned kitchen where the roof had fallen in, except on that part, that looked like the kitchen was still in use? How about the bedroom, all motel beige, burnt sienna, olive green, coverlet on the beds made, lamp on the nightstand and everything under thick dust, maritime print on the wall warping? How about algae sliming the opening of the concrete reservoirs? How about the shack at the end of the walkway, looking out on the silent cove (with one dock sunken between rotting pilings, the water deep, deep green, black against the uplifted black rock of the island), shattered glass and shattered white ceramic plates littering the floor? Will it tug at my thinking like gristle, like a ligament, when it comes, the call?

Sesshu Foster's Blog

- Sesshu Foster's profile

- 41 followers