Paul Athanasius Robinson's Blog: Realism Rampant, page 3

October 24, 2018

Publication Choice for The Realist Guide to Religion and Science

Why was your book published with a non-SSPX publisher?

For two reasons. The first reason is audience. It is the desire of every author that as many people as possible read his book. This is especially true if you feel, as I did, that you were making a new contribution to an old topic.

Now, the likelihood of people reading my book, or at least purchasing it, would go up in proportion to the distribution of the publisher. At first, I was thinking (dreaming?) of having a press like Regnery, with its global market, publish the book. After some investigation, I realized that I would need much better connections than I do to make that happen.

The next best thing would be to have a publisher that could market to the mainstream Catholic world. I thought this would be at least a possibility, despite my membership in the SSPX, because of the fact that my book is not about the crisis in the Church, but rather is about the intersection of religion and science.

Thus, with the approval of my superiors, I submitted the manuscript to Gracewing. The rest, as they say, is history.

It turned out that Gracewing was a particularly apt choice, at least from one point of view, and this is the second reason. The priest who runs Gracewing, Fr Paul Haffner, is, in a sense, the intellectual heir of Fr Stanley L. Jaki (1924-2009), the late, great physicist theologian. Fr Haffner did his dissertation on the work of Fr Jaki, “the only book on Father Jaki approved by him during his lifetime”. The dissertation was published under the title Creation and Scientific Creativity: A Study in the Thought of S. L. Jaki. Fr Haffner is also the founder of the Stanley Jaki Foundation.

My own book seeks to deepen one of the important insights of Fr Jaki, namely, that both science and natural theology have the same basic epistemological structure. He gave the greatest elaboration to this insight in his Gifford Lectures of 1974-75 and 1975-76, published as The Road of Science and the Ways to God. Because of Gracewing’s connection to Fr Jaki through Fr Haffner, it was particularly appropriate that, of all the mainstream Catholic publishers, it be the one that publish my book.

The result has been that my book has a much easier entry into parish book shops that it would have otherwise. The diocese of Armidale here in Australia, for instance, kindly put a notice in all of their bulletins about my book, and placed flyers in the churches. Besides this, certain Catholic publications have offered to print reviews. Other Catholic media outlets have offered to do interviews.

Some people have been critical of the fact that I have attempted to popularize an idea of Fr Jaki, because they accuse him of being a Modernist. This accusation is certainly false, as anyone who has read his writings would realize. He was attached to his Catholic faith, and even belligerently attached to it, in his feisty Hungarian way.

The main beef against Fr Jaki is that he was a theistic evolutionist. This is true. However, I explicitly differ from Fr Jaki on that question in my book, and besides, theistic evolution is a position allowed to orthodox Catholics. If Catholics want to argue against theistic evolution, the Church has them do so on scientific grounds, not theological ones. Catholics are free to be strict creationists, progressive creationists or theistic evolutionists.

I could go on about why Fr Jaki favored theistic evolution, but that is really for another question. It was mainly because of his desire to reduce all science to physics, and his favoring of theistic evolution did not at all prevent him from leveling some very sharp criticisms against Darwinism.

In the end, the main thing is the salvation of souls. If a person is able to assist the salvation of souls better by one means than another, without committing sin or compromising his faith, then it is prudent to do so. This was my ultimate consideration in seeking to find a publisher with a wider distribution.

October 6, 2018

Is Biblicism Catholic?

Introduction

In my article “St. Maximilian Kolbe’s Disagreement with the Kolbe Center”, I pointed out that St. Maximilian Kolbe held positions on science that are directly contrary to positions which the Kolbe Center holds to be “clearly” taught by Scripture and so the only views allowed to Catholics. Robert Sungenis, whose books are promoted by the Kolbe Center, wrote a rebuttal to my article in order to come to the defense of the Kolbe Center. This rebuttal was posted on the “Catholic Layman’s Theology” group’s Facebook page.

The main contention of my article was that, while Catholic creationists—I will refer to them as ‘biblicists’ in the rest of this article to be clearer—pretend that only their views are orthodox, it is, in fact, difficult, if not impossible, to find those views among the perfectly orthodox Catholic exegetes of the first half of the 20th century.

Biblicism is the practice of using the Bible as an exclusive determinant of truth, especially in its strict literal sense. The biblicist begins by holding that certain passages of the Bible can only be interpreted in their proper literal sense. Then, clinging to that sense as infallibly true, he refuses to allow any information from outside the Bible to deny that interpretation. Such information would include the data of science, arguments of reason, and even statements of the Church’s Magisterium. In the end, biblicism is simply a species of the Protestant doctrine of sola Scriptura.

In The Realist Guide to Religion and Science, I point out how dangerous it is for humans to isolate one particular mode of knowing and make it the only way to discover truth. Doing so leads the mind to form a priori ideas about reality and then forbids reality itself to teach the mind anything different from those ideas. In this case, biblicism reduces all knowledge to Biblical knowledge.

The Catholic Church has always fostered a realist view of reality, one which balances the modes of human knowing: sense knowledge, conceptual knowledge, and the knowledge obtained from revelation. As such, she has never employed a biblicist model of Scriptural exegesis. This is why she has allowed for varying interpretations of Genesis 1 over the ages, as long as those interpretations remained within the boundaries of the faith. It would be heretical to hold that Genesis 1 is a myth, that is, a pure invention of humans with no truth value. But it is not heretical to hold that Genesis 1 teaches certain religious truths, necessary for our salvation, but does not teach that the universe is a certain age, a question that has no direct bearing on salvation.

With the advance of science, it became clear that the universe has a history, that it is much older than 6000 years, that it was not created by God in a fully formed state. Catholics had no problem utilizing this information to assist in finding the right sense of the Bible. Specifically, Pope Leo XIII and the Pontifical Biblical Commission clarified that there is no need to interpret Genesis 1 as saying that the universe was created in six, 24 hour days.

Despite the freedom granted by the Church on these questions, Catholic biblicists are convinced that the strictly literal sense of Genesis 1 is the only orthodox one. To assist their cause, they portray their position as authentically Catholic and, whenever upstanding Catholic figures disagree with them, they attack them as being either ignorant or heterodox. We will see how this is the case with St. Maximilian Kolbe and Fr. Fulcran Vigouroux. We will also consider the position of Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre.

Before proceeding, however, I want to repeat my main contention—that the biblicist view did not exist among Catholic exegetes after Leo XIII (nor, really, did it exist before him either)—and kindly warn the Catholic biblicists that, if they are prudent, they will stop trying to say otherwise.

A difference in formation

When Mr. Sungenis seeks to defend the Kolbe Center in face of the fact that St. Maximilian Kolbe was a progressive creationist like myself, he does not find it advisable for him to accuse St. Maximilian of heresy for being a heliocentrist and a believer in an ancient universe. Instead, he claims that St. Maximilian erred in ignorance, that he adopted the wrong position on account of having a defective formation:

My inkling is that if Maximilian Kolbe had been educated from the patristics, the tradition and the official decisions of the magisterium to geocentrism, short ages and a global deluge, he, unlike Fr. Robinson, would have accepted them.

Now, this claim is not just extraordinary from the fact that Mr. Sungenis seems to be touting his own formation above that of St. Maximilian Kolbe; it is also extraordinary in that St. Maximilian’s formation was among the best possible. He earned a doctorate in philosophy at the foremost seminary in the Catholic world—the Gregorian in Rome—beginning his studies under the greatest pontiff of the 20th century, St. Pius X. He went on to earn a second doctorate in theology at the Pontifical University of St. Bonaventure. In other words, it would be hard for any Catholic to dream of a better seminary formation than the one that St. Maximilian received.

Mr. Sungenis, meanwhile, has never studied Catholic theology in any official capacity. He received a Master’s in theology from a Protestant seminary in Pennsylvania. He also claims to hold a doctorate, but the worth of that doctorate may be safely questioned. The degree was obtained from the organization Calamus International University in the third-world archipelago of Vanuatu—a university without Catholic faculty or courses in any Catholic discipline—under a non-Catholic academic advisor who specializes in past-life regression and neo-shamanic healing. (For more about Sungenis’s academic credentials, see here or read The New Geocentrists by Karl Keating.)

If one wishes to escape the charge of being a biblicist, the reasonable thing to do when confronted with St. Maximilian Kolbe’s positions is to admit that the Church does not teach geocentrism or a 6000 year old universe. For to be a biblicist is to refuse to countenance the Church, or a saint, holding any position other than that of the strictly literal sense. As such, when biblicists are confronted with evidence that perfectly orthodox Catholics believed in an ancient universe, they do not conclude that their own position is not Catholic, but rather that the position of the perfectly orthodox Catholics is not Catholic. What eventually happens, when this strategy is employed consistently to meet every challenge, is that all Catholic authority crumbles, and we are only left with the sola Scriptura authority of the biblicist.

The authority of the Pontifical Biblical Commission

Having seen how Mr. Sungenis handles the witness of St. Kolbe, we must turn to the authority of the Pontifical Biblical Commission and that of Fr. Fulcran Vigouroux.

In The Realist Guide to Religion and Science, pp. 277-278, I state the following:

In an effort to see what was the standard pre-Vatican II teaching in Catholic seminaries on these questions (pre-Vatican II texts would be, if anything, more conservative than post-Vatican II ones), I investigated several manuals. What I found was that not a single manual advocated any of the Protestant fundamentalist positions.

I then provide a table with four examples of such pre-Vatican II Scripture manuals. Since Mr. Sungenis agrees with the Protestant fundamentalist positions that I mention and disagrees with the manuals, he portrays the teaching of Catholic manuals as being un-Catholic:

In his book, Fr. Robinson gives us only four individuals he regards as “pre-Vatican II Catholic exegetes” (Gigot, Vigouroux, Renié, Simon-Prado). The first three were French liberals who were already entrenched in the neo-orthodox interpretation of Scripture they learned from the Protestant liberals, beginning with the Protestants of the 1700s. As such, Fr. Robinson’s mention of these individuals only proves our point that Vatican II’s liberals did not arrive in a vacuum. The seeds of dissent were laid many decades prior, mostly by the liberal French and German schools.

In another place, he states:

These manuals are not Catholic doctrine, either official or unofficial. They are the opinions of the men who wrote them (Gigot, Vigouroux, Renié, Simon-Prado).

It is a dangerous game to attack these manuals, for they were used to instruct generations of priests in the study of Sacred Scripture. The manuals all received their imprimaturs and were a benchmark for orthodoxy. They encapsulated the age-old teaching of the Church on Scriptural matters in clear, readable, multi-volume sets. If those manuals were wrong, then we may really wonder if the Church was ever right.

I could have listed several more manuals in my book, and I have yet to find a single one that took biblicist stances, but let that pass. I rather want to focus on the accusations that are laid against the four authors I cited, and specifically, the implications of those accusations for one of them, Fr. Fulcran Vigouroux. According to the statement above:

1. Fr. Vigouroux learned his interpretation of Scripture from Protestants.

2. He was a precursor for the liberals of Vatican II.

3. He was a member of the French liberal school of interpretation.

The first point, we note in passing, would disqualify Mr. Sungenis himself, for, as we saw, he did his Scriptural training under Protestants. At least, it does seem that Mr. Sungenis is willing to accept some Catholic authority on Scriptural matters, namely, the Pontifical Biblical Commission:

One only needs to read the 1909 Pontifical Biblical Commission to see the Church settled many of the issues, as did Lateran Council IV and Vatican Council I, and the PBC was an authoritative arm of the Church at that time under Pius X. The only thing the Church left open was whether the Hebrew YOM was to be interpreted as a “24-hour period” or a “certain space of time.” It left both meanings open, but not because it was endorsing or allowing evolution, but because the Hebrew YOM has five different meanings in the Hebrew language. Even then, the most that anyone could get out of the 1909 PBC, that is, if he were to base it on what the Tradition taught, is that “a certain space of time” in Augustine’s alternative interpretation, is that God created everything at once. There was no recourse to either evolution or theistic evolution or progressive creationism in the 1909 PBC document.

Now, what Mr. Sungenis does not realize when he makes this statement is that he disagrees with himself. He both accepts and rejects the same authority. For the primary signatory of the 1909 PBC document was Fr. Fulcran Vigouroux.

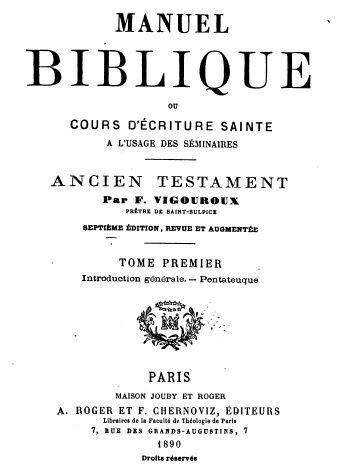

Fr. Vigouroux the traditionalist

Not only was Fr. Vigouroux neither a liberal nor a Modernist, he was one of the purest representatives of Catholic orthodoxy in Scriptural interpretation, which was why St. Pius X chose him to be a consultor for the Pontifical Biblical Commission and its first secretary, from 1903-1912.

Marvin O’Connell wrote an historical study of the drama leading up to St. Pius X’s condemnation of Modernism in 1907, a book entitled Critics on Trial: An Introduction to the Catholic Modernist Crisis. Here is O’Connell’s portrayal of the rivalry between Vigouroux and the Modernist Fr. Alfred Loisy:

Alfred Loisy was duly named professor of sacred Scripture in the Institut Catholique of Paris. But the prior appointment of Vigouroux threw a long shadow over his new dignity. It meant that he had for a senior colleague—a supervisor almost—an intransigent traditionalist who was, besides, highly influential within the closed clerical world. (p. 69)

So, Fr. Vigouroux was not a liberal after all; he was rather an ‘intransigent traditionalist’. (For other examples of Mr. Sungenis attacking other pre-Vatican II traditionalists, see here and here). This explains the confidence of St. Pius X in him. After all, the documents of the PBC had tremendous weight. St. Pius X bound Catholics to submit to its decisions in his Motu Proprio Praestantia Scripturae in 1907:

After long discussions and most conscientious deliberations, certain excellent decisions have been published by the Pontifical Biblical Commission, very useful for the true advancement of Biblical studies and for directing the same by a definite norm. Yet we notice that there are not lacking those who have not received and do not receive such decisions with the obedience which is proper, even though they are approved by the Pontiff.

Therefore, we see that it must be declared and ordered as We do now declare and expressly order, that all are bound by the duty of conscience to submit to the decisions of the Biblical Pontifical Commission, both those which have thus far been published and those which will hereafter be proclaimed, just as to the decrees of the Sacred Congregations which pertain to doctrine and have been approved by the Pontiff; and that all who impugn such decisions as these by word or in writing cannot avoid the charge of disobedience, or on this account be free of grave sin. (Dz 2113)

Thus, St. Pius X certainly followed closely the work of the Commission and approved its decisions. This is why he accorded those decisions a magisterial weight. This includes the clarifications made in 1909. If Catholic biblicists accept the authority of the PBC under St. Pius X, it would only be logical for them to hold Fulcran Vigouroux in very high regard.

Fr. Vigouroux’s understanding of Fr. Vigouroux

For Mr. Sungenis, when the PBC allows that YOM or ‘day’ can mean ‘a certain space of time’, the PBC is only allowing for one other interpretation than ‘day’ meaning a 24-hour period (see citation above). The other permitted interpretation is that everything was created at once, that is, instantaneously. In other words, ‘a certain space of time’ can only mean no time at all, for what is instantaneous is what does not take place in time.

If we want to find Fr. Vigouroux’s thinking on this question, we have only to consult his manual. I have available to me three editions of that manual, the 7th appearing in 1890, the 8th appearing in 1892, and the 11th appearing in 1901, two years before Fr. Vigouroux began his work on the Commission. I will quote a paragraph from each of them.

Here is something from the 1890 manual (all translations mine):

When did the great events that we have just studied take place? Scholars hold that matter was produced at a very distant time. The Bible is silent on this point. Consequently, it leaves us free to accept the scientific opinion on the date of the origin of the world that seems to be the most probable. (Manuel Biblique, Ou Cours D'Ecriture Sainte A L'Usage Des Seminaires, Vol. 1: Ancien Testament; Introduction Generale, Pentateuque, §278)

In the 1892 manual, he states:

First, let us examine the word ‘yom’, ‘day’. Nothing obliges us to understand it in the strict sense of a duration of 24 hours. God certainly did not take 24 hours to create light, nor 24 hours to create the stars, the plants, and the animals; an instantaneous act of the will was sufficient for Him to produce all such beings. Since God could not have spent an entire day in giving existence to each of the species of creatures which appeared during the days of Genesis, there is every reason to think that the word ‘day’ is a figurative expression which here means an ‘epoch’. (Manuel Biblique, vol. 1, §267)

In the 1901 manual, we find the following:

The word ‘rest’, when applied to God, is certainly metaphorical, as everyone agrees. It is to be believed that the expressions ‘day’, ‘evening’, and ‘morning’ are likewise metaphorical. … Yom ordinarily indicates the space of time between two risings of the sun, ‘ereb (evening) marks the setting of that star, and boqer (morning) its rising; several reasons which are not without their importance, however, seem to indicate that these three terms should not be taken in a proper sense, but in a figurative sense. The use of metaphors in Genesis, at a time when everything was expressed in images, should not surprise those who know the customary speech of oriental language. (Manuel Biblique, vol. 1, §267)

In The Realist Guide to Religion and Science, besides citing Fr. Vigouroux’s position on this question, I also quote at length his presentation of the scientific obstacles to there being a globally universal Flood (p. 291). And who would dare claim that his position was not Catholic? After all, if this terror of Loisy, this confidante of St. Pius X, and this renowned Catholic manualist who was behind the great decrees of the PBC in the first decade of the 20th century—if Fr. Fulcran Vigouroux, I say, cannot be trusted as being representative of Catholic orthodoxy, who can?

Archbishop Lefebvre

Like St. Maximilian Kolbe, Archbishop Lefebvre received his seminary formation in Rome (from 1923-1929). He famously joked to his seminarians in later years that he realized, in Rome, that he was a liberal, through the teaching of Fr. le Floch (Marcel Lefebvre: The Biography by Bernard Tissier de Mallerais, p. 36). This was his way of indicating that he learned the purest of Catholic orthodoxy at the French Seminary there.

I asked His Excellency Bishop Bernard Tissier de Mallerais, the greatest living authority on the work and writings of Archbishop Lefebvre, whether he knew of any statements of the Archbishop on questions of geocentrism/heliocentrism, or suchlike. He did not recall any explicit statements on these specific questions, but he did state the following, words which he gave me permission to pass on:

Maybe in Mortain, in 1945 and 1946, he may have dealt with the subject, as teacher of Holy Scripture; but I am sure that he did not depart from the explanations given in the Catholic classic manuals of biblical studies.

The Archbishop would certainly have received his formation in tradition, namely, the tradition of the Catholic manuals.

Conclusion

The Council of Trent, in its decree Insuper, stated the following:

No one... shall presume to interpret Scripture contrary to the sense which Holy Mother the Church held and holds, to whom it belongs to judge the true sense and interpretation of Holy Scripture.

This statement defeats biblicism, because it places an authority above the Bible, an authority which determines whether a strict literal sense of the Bible is to be followed or not. In the case of Genesis 1, the Church has made it abundantly clear that Catholics are not bound to hold that the Bible teaches a 144-hour creation period. They are also free to allow for the universe being far older than 6000 years.

To deny this is to place one’s own interpretation of the Bible above that of the Church. It is, at the same time, the destruction of the authority of the Church. The pontificate of St. Pius X is held, by traditional Catholics, to be the very model of orthodoxy and magisterial authority. When authorities in the immediate environment of that pontificate are torn down, when a saint formed at Rome under the watch of St. Pius X is found deficient, when a Scripture scholar hand-picked by St. Pius X to be the mouthpiece of his magisterium on Scriptural questions is denounced as a liberal—once these authorities are discredited, to whom then can a Catholic possibly have recourse as being safe?

There is no need for any faithful Catholic to distrust the standard pre-Vatican II Scriptural manuals, or the likes of St. Maximilian Kolbe and Fr. Fulcran Vigouroux. All that is necessary is to simply submit oneself to the obvious truth of Catholic teaching on these Scriptural questions: the Bible does not teach geocentrism or heliocentrism; it does not teach a universe thousands of years old or billions; it does not teach a geographically universal Flood. Fr. Vigouroux and St. Maximilian Kolbe had freedom on these questions under St. Pius X, and so do we now.

August 29, 2018

St. Maximilian Kolbe’s Disagreement with the Kolbe Center

Introduction

The Kolbe Center designates itself as “a Catholic apostolate dedicated to proclaiming the truth about the origins of man & the universe”. That ‘truth’ amounts to a purportedly Catholic version of what is really just modern Protestant creationism, the idea—more properly referred to as ‘biblicism’—that God intended for the Bible to teach science through a strictly literal interpretation of the Biblical text. This idea leads the Kolbe Center to conclude that the Bible teaches geocentrism, a 6000 year age of the universe, and a Deluge that covered the entire Earth, instead of a limited part of it. Since they insist that this is what the Bible teaches, and the Bible is inerrant (as we all agree), they also conclude that this is what the Church teaches. This is where they go astray.

Since Pope Leo XIII’s encyclical Providentissimus Deus (1893), Catholic exegetes have abandoned the idea that the Bible is meant to teach science, adding this principle to the age old Catholic principle that the Bible must be reconciled with science, at least with settled science. Pope Leo explicitly states that:

• Sacred Scripture speaks in a popular language that describes physical things as they appear to the senses, and so does not describe them with scientific exactitude.

• The Fathers of the Church were mistaken in some of their opinions about questions of science.

• Catholics are only obliged to follow the opinion of the Fathers when they were unanimous on questions of faith and morals, where they did not err, and not on questions of science, where they sometimes erred.

Notwithstanding the authority of this encyclical and succeeding pre-Vatican II encyclicals on Scripture; notwithstanding the fact that biblicism has never been a position of the Catholic Church, but rather has its origins in Protestantism; notwithstanding the clear evidence that pre-Vatican II Catholic exegetes, including those fully orthodox, did not countenance the creationist position in their Scripture manuals and scholarly Biblical journals—despite all this, the Kolbe Center claims that creationist biblicism is the ‘traditional Catholic doctrine of creation’.

Defending Orthodoxy

Once the Kolbe Center embraces the idea that God Himself—through His Bible and His Church—teaches that He created the universe fully formed in six, 24 hour days, 6000 years ago, with the Earth at the center of that universe, it becomes for them a matter of Catholic orthodoxy to defend these positions. They insist that Catholics must be convinced that they are falling into a Modernist trap if they abandon these positions.

This is why the Kolbe Center warns, in an article on their website:

The argument is sometimes made that abusing the literal meaning of Scripture has little effect on moral perspectives. Whether creation or evolution is true, we are told, is a question to be resolved by science, as it marches on, every day, in steady progress toward improving the general welfare and standard of living. This modernist attitude is refuted by the progressive and degenerative moral effect produced by rejection of, first, geocentrism in the 17th century, then special creation in the 19th century, and now the very existence of human life in the womb in the 20th . The theistic evolutionists and Scriptural revisionists have twisted the literal meaning of Genesis to accept both biotic and cosmic evolution.

In this way, the acceptance of geocentrism and young Earth creation is placed on the same level as the acceptance of life beginning at the moment of conception.

Moreover, according to the Kolbe Center, one capitulates to a plot of atheists when one rejects geocentrism and young Earth creation:

Atheists understand that in order to replace the Bible-based Christian worldview and system of morality, they need to discredit the Church and the Bible. They do this by questioning the Genesis account of Creation and the Fall, and the global Flood. One can even argue that the effort to replace geocentrism with heliocentrism was more an attack on the Church and the Bible than it was a scientific endeavor.

Additionally, the Kolbe Center strongly promotes the book The Doctrines of Genesis 1-11 by Fr. Victor Warkluwiz. It includes as doctrines of Genesis the following:

• God created each thing in the world immediately.

• God created the world in six natural days.

• God created the world several thousand years ago.

• God destroyed the world that was with a worldwide flood.

In this book Fr. Warkluwiz also espouses geocentrism as the “clear” teaching of the Bible.

The Realist Guide Review

The Church holds that the questions of the age and development of the universe are not settled by the Bible, thus leaving these questions to the investigations of science and leaving Catholics free to hold their own opinions on those questions. In my own book, I demonstrate that the Church binds her members to believe that God created the universe, that He created our first parents directly, and that all human beings descend from Adam and Eve.

It is my own opinion, expressed in The Realist Guide to Religion and Science, that there is strong scientific evidence for the Big Bang Theory and so for an ancient universe, while there is strong scientific evidence against Darwinian evolution, whether it be the development of life from non-life by purely natural processes, or whether it be the development of more complex species from less complex species by purely natural processes, what is known as macroevolution.

In the terminology, this makes me a ‘progressive creationist’, one who holds that there was a chemical and galactic development of the universe over billions of years by means of the fine tuning that God built into the universe, but that God Himself directly intervened, on multiple occasions, to create biological life.

Because I hold this position, I came under fire in the review of my book that appeared on the Kolbe Center website in May. The reviewer was naturally pleased at my strong criticism of Darwinian evolution, but was not surprisingly displeased at other aspects of the book and attacked my orthodoxy, as follows:

“To deny the global Flood is essentially to call Our Lord Jesus Christ a liar or mistaken about a fact of history.”

“The Bible explicitly says three times that the earth does not move (Psalms 92:1, 95:10, and 103:5 DRB). It also states three times that the world was created in six days (Gen. 1, Exodus 20:11 and 31:17) and the Genesis genealogies are given in exact years.”

“Fr. Robinson gives far too much credit to fallible human hypotheses in natural science in thinking that geocentrism, a young earth, and a global Flood have been disproven, contrary to the Bible.”

By making these statements, the reviewer is not only calling into question my own orthodoxy as a Catholic priest, but also that of many perfectly orthodox and much more illustrious figures of our Catholic past. For the fact is that the standard pre-Vatican II and post-Providentissimus Deus position of Catholics was to consider themselves completely free on these questions. For instance, one example of a pre-Vatican II progressive creationist can be provided in the figure of St. Maximilian Kolbe.

St. Maximilian and cosmic evolution

The Kolbe Center provides seven reasons for choosing St. Maximilian Kolbe as its patron saint, one of them being that he “did not subscribe to theistic evolutionism or to long ages”. It is important to note that they count ‘progressive creationism’ as a form of ‘theistic evolutionism’, as may be seen in the review of The Realist Guide:

Fr. Robinson takes the position of progressive creation, which is a form of theistic evolution.

To discover St. Maximilian’s views on subjects of natural science, one may profitably consult the two volume The Writings of St. Maximilian Maria Kolbe: Volume 1 Letters & The Writings of St. Maximilian Maria Kolbe: Volume 2 Various Writings, released in English in 2016. While I did not find anything in these volumes that refers to his position on the extent of the Flood, his position on the other matters are made quite clear.

The helpful index at the conclusion of the second volume has four entries for the topic “Evolutionism/Evolution”, of which n.1186 perhaps contains St. Maximilian’s clearest statement on that topic:

I am not able to believe that man is a perfected ape. We are dealing here with the problem of evolutionism. One hundred and twenty years ago, there was no theory more diffused among the people than evolution. A whole mountain of critical essays has been published in this regard, but the more books are written, the more the problem persists. This theory not only does not accord with the findings of contemporary experimental sciences, which are in continuous development, but they even contradict them, as has been accurately ascertained.

What is notable about this passage is not just that St. Maximilian rejects Darwinian evolution, as I do, on the basis of scientific evidence, but also that he does not have recourse to Scripture or theology in refuting it, knowing that it is not a question for theology. In n.1124, he even states that, if evolution were true, it would still have to come from God:

Even if we amuse ourselves by being evolutionists and proclaim that all of this has developed from a certain primitive material, the same question would still apply. Who gave life to this matter? And who, with such wisdom, has endowed it with movement, so that after so many years, during which several changes have taken place, could implement the intended purpose? Well, this mind, which is guided by such intelligence, we call God.

On the questions of heliocentrism and the age of the universe, there is a text by St. Maximilian, n.1201, that could not make his position clearer: he accepted the standard scientific position on these questions, namely, that

1. The earth revolves around the sun.

2. The solar system itself is moving.

3. The earth and the moon developed from nebular matter over very long periods of time.

Here, then, is his position on heliocentrism and the movement of the solar system:

My chair, rotating together with the earth, moves at a speed of 300 m a second, while our earth revolves around the sun at 30 km/s. The earth, together with the sun, is moving toward the constellation of Hercules.

He likewise holds that the stars are millions of years old:

To reach the furthest star [in the Milky Way], 140 million years would be necessary. It is therefore easy to understand that the position of the stars, which we now see with our eyes, is not the actual one, but the position they had 140 million years ago.

Finally, Fr. Maximilian does not believe that the earth, moon, and sun were created directly by God, but rather that they formed over long periods of time from a nebula:

[Science] teaches that the moon was detached from the earth after the latter came into existence. The earth itself was detached from the sun, while the sun originated from a nebula. Besides, it seems probable that an enormous number of stars, together with the Milky Way, have been detached from a nebula. This is what science teaches. It could be observed that the history and evolution of the earth take place just as they used to happen in the past, in very remote eras, in some nebula.

St. Maximilian did not find these positions to be injurious to the faith; on the contrary, he expressed them in an issue of his Japanese version of The Knight of the Immaculata and concluded them with an argument for the existence of God. If we couple his stance on cosmic evolution with his rejection of Darwinian evolution, we have the position of progressive creationism.

Conclusion

I did not realize, when I wrote my book, that my own position was so close to that of St. Maximilian Kolbe. Though I am obviously gratified to find that such is the case, it is nevertheless disconcerting to find that St. Maximilian Kolbe should fall under the same condemnations under which I fell by the Kolbe Center of which he is the patron. If his Knight of the Immaculata article from above were submitted anonymously to the Kolbe Center, it would certainly receive a negative review.

It would seem that using the name of St. Maximilian Kolbe in support of the teachings of the Kolbe Center is similar to starting an Annibale Bugnini Center for the promotion of the Tridentine Mass, or founding a Society of St. Pius X for the promotion of Modernism. The fact is that St. Maximilian did not agree with the central tenets of the Biblicist creationism on which the Kolbe Center is founded. The Kolbe Center professes to have chosen him as its patron, because “he was an expert in theology, philosophy, and natural science”, but it does not follow him in questions of natural science nor those of exegetical science.

In light of this fact, it would seem that the Kolbe Center should either choose a different patron for its endeavors or, please God, adopt the position of its patron.

August 20, 2018

Religion's Contribution to Philosophy and Science

What is religion’s contribution to science and philosophy?

It is a person’s worldview that determines how he or she looks at reality. How they look at reality determines whether they think it is knowable and how they think it should be known. In this sense, then, a person’s worldview determines how that person does science and philosophy.

To illustrate this abstract truth, consider a situation where girl meets boy. They go on a date. If the girl finds out that he is a jerk, she does not want to get to know him better and cancels future meetings. If the girl finds that he is a prince charming, she ardently desires to get to know him better and ultimately spends the rest of her life with him. In either case, it is her view of the boy that determines whether she wants to know him more or ignore him. Our worldview does the same thing for us in relation to reality. It tells us how to look at reality and, in doing so, determines whether we want to know more about it or ignore it.

Where have people’s worldview typically come from? From religion. This was true of all of the civilizations of the past, before the advent of our current secular societies in the 19th century. It was true of the pre-Christian cultures: the Indians, the Chinese, the Babylonians, the Egyptians, the Jews, the Greeks, the Romans, the Mayans, the Incans, the Aztecs, and so on. This was also true of Christian and Islamic cultures.

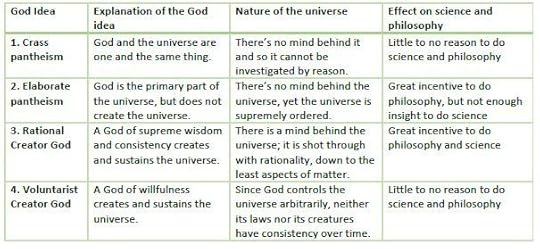

What effect did the religions of these cultures have on the pursuit of science and philosophy? Well, it all depended on the ultimate explanation which the various religions gave to the universe. This could be called their ‘God idea’ and it has the biggest impact on a religion-driven worldview. That idea says whether reality should be explored or ignored.

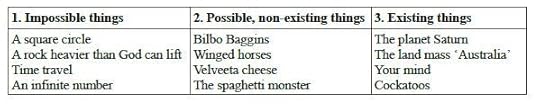

There are four different God ideas, coming from four different species of religion, that I would like to consider, in relation to their influence on the pursuit of science and philosophy. This table will summarize my view and then we will get into the details.

1. Crass pantheism: God is the universe

(for the extended version of this section, see Stanley Jaki’s Science And Creation: From Eternal Cycles To An Oscillating Universe)

Pagan religions were universally pantheist. They all struggled to make sense of the world around them, but their solutions were overly simplistic. One thing that especially struck the pagans was the cycles they observed in nature. The recurrence of the seasons, the rising and the setting of the sun, the waxing and waning of the moon, the rotations of the heavens, the births and deaths of organic life, are all so many evidences that circular patterns are built into the very fabric of reality.

If the mind makes this observation and goes no further, then cyclical change does not present itself as an aspect of reality, but as the whole of reality. A key characteristic of circles is that they participate in the infinite. They have no edges, no beginning and no end. To illustrate this, imagine someone driving around a perfectly circular track at a constant speed, the wheels always turned to the same angle. Under these conditions, the driver can go around the track forever without a single change (ignoring friction and fuel consumption). And so, if the heavens are turning around in circles, and Earth processes are going around in circles, then perhaps the heavens and the Earth are eternal. And if they are eternal, then perhaps they are the ultimate reality. The universe and God are one. Such was the inference of the pantheists.

When this crass pantheism becomes the master thought of a civilization, and that culture is unable to make further progress in causal reasoning, then it is only natural that some mythology will start to encrust itself around that metaphysical kernel which is still in a stage of philosophical infancy. In other words, thinkers will just arrest their philosophical speculation there and, instead of continuing to investigate reality with reason, they will just tell stories about it. The Greek word for ‘story’ is mythos, and this is where we get the word ‘mythology’.

Belief that the universe and God are one and the same thing is a ‘God idea’, and it is not a very healthy one for the intellectual pursuits of philosophy and science. The reason is that pantheism projects a picture of a universe that has no mind behind it. It just it what it is and so you must not expect to understand it. Precisely because you cannot understand it or even expect to understand it, you make up tall tales about it.

Take, for instance, the mythology of Buddhism, the idea that humans reincarnate again and again until, or unless, they reach nirvana. This is an interesting story, but it is not true. The only way for a human to become a horse is by changing its very being. But, changing its very being, it will no longer be a human. Thus, it is impossible for a human to reincarnate and retain his personal identity at the same time.

The Buddhists took this idea from all of the cycles that they noticed in nature, especially the cycles of life and death manifested in the seasons. They assumed, from these cycles, that humans also continually die and come to life again. They also assumed that these cycles were eternal.

The effect of this idea upon intellectual endeavor can be devastating. Consider how you would feel if you were stuck on a wheel that was endlessly turning and you had no way to relate or talk to the one operating the wheel. The wheel just turned and turned and there was nothing you could do about it, no one who would listen, no way to stop the turning or make any sense out of it.

If such were your plight, you might very well seek to escape from the turning by shutting yourself off mentally from the reality outside of you and trying to reach a state of total escape, a state where you do not even realize what is happening to you, a state of utter numbness. Well, that state is the nirvana that the ancient Buddhists sought and they sought it because they saw reality as going around in endless and mindless cycles.

The take home lesson is this: if the universe is seen as being the ultimate principle, then it is not seen as having a mind behind it which would put any rational order into it. And if your culture does not hold that the universe is shot through with rationality, then its ethos is one that discourages humans from the investigative pursuits of science and philosophy.

To be motivated to do philosophy and science, humans needed to break free from mythology and needed to form the idea of a transcendent, all-wise God behind the universe who creates it and builds rationality into its very fabric. The Greeks accomplished the former and gave birth to philosophy; the Catholic Middle Ages did the latter and gave birth to science.

2. Elaborate pantheism: God within the universe, but not the universe

The first recorded culture which set reason free from mythology to systematically pursue a total causal knowledge of reality was the Greeks’. The metaphysician Thales (624–546 BC) put the Greeks on the trail of hunting for ultimate causes when he argued, by means of reason, for water as being the ultimate principle of the universe. This idea of the principle of all reality being within the universe, instead of identifying the ultimate with the universe, I call ‘elaborate pantheism’.

Thales’s challenge helped the Greeks set mythos to one side, in order to see what logos or ‘reason’ could do. They started forming, by means of philosophical reasoning alone, in independence from religion, more sophisticated notions of God than those of mythology, ones wherein God was a cause accounting for reality, not one wherein stories about gods accounted for it. Schools of philosophy sprouted like mushrooms in the Hellenic world from around 550 to about 350 BC, each with their own answer to the ultimate questions.

The story of those 200 years is fascinating, but we only have time to bring up the thinker that culminated the Greek philosophical Olympic games, namely, Aristotle. His powerful genius was able to set down the rules for human thought (logic), formulate an epistemology (realism) that matches exactly with our human faculties of knowing, and develop a powerful and even scientific conceptual apparatus for philosophic endeavor. To him we owe the invaluable distinctions which form the only launching pad from which a philosopher can hope to safely discover the first principle of reality: act and potency, substance and accident, matter and form, the four causes, the ten categories.

By means of his insights, Aristotle accomplished something extraordinary: he used philosophy as a bridge to religion. He constructed a theology by means of reason alone, something we today refer to as ‘natural theology’, also known as metaphysics. Starting with the observation of the nature of movement around us, he argued, conclusively, that some immaterial, unchanging, most perfect being must be at the ultimate cause of all movement. By all movement, he meant any movement whatsoever. If there is no First Mover at every moment, then all movement ceases.

Aristotle’s First Mover somehow did not completely transcend the universe, still being in it in some way, and thus Aristotle was still something of a pantheist. He had the Prime Mover perform his work of causing all movement by attracting everything in the universe to himself. Thus, Aristotle did not see God as moving things by creating them; he rather saw God as moving things by motivating them.

Aristotle’s philosophy was fantastic, but his inability to see God as a creator meant that his physics was extremely deficient. He explained all physical motion in terms of attraction and so claimed that heavier balls fall to the ground faster than lighter ones, that rocks fall to the ground because of an attraction to their natural place, and that the air around a projectile aids its upward movement rather than impedes it.

Because Aristotle was so amazing in just about every intellectual discipline, both his good philosophy and his false science were widely accepted in the centuries that followed. In the end, it would take 1500 years before his physics was rejected and replaced with what we now know as science and the scientific method.

In the case of the pagans, then, their religions impeded, to a greater or lesser degree, the fruitful pursuit of philosophy and science. It was only when mythological paganism was ignored that the great Greek philosophers were able to make their irreplaceable contribution to all future thought.

But, unlike philosophy, which was born by ignoring religion, science was born because of religion, specifically by a religion that believed in a God who builds rationality into every nook and cranny of his material creation, and that created a civilization wherein that God idea informed the attitude of its citizens towards reality.

3. Rational Creator God

(for the extended version of this section, see Edward Grant’s The Foundations of Modern Science in the Middle Ages: Their Religious, Institutional and Intellectual Contextsor James Hannam’s Genesis of Science or Stanley Jaki’s The Savior Of Science)

We have seen two God ideas so far: that of the crass pantheists, coming from mythology, an obstacle to intellectual pursuits; that of Aristotle, who used reason alone to form the God idea of a Prime Mover who orders the movement of the universe by providing it a goal. Now, we come to the God idea of the Catholic Middle Ages, especially as conceptualized in the Summa Theologica of St. Thomas Aquinas.

For Aquinas, God is a wise creator, embedding a rational order into all of creation, and so making its utmost recesses intelligible to human minds; He is good, conferring worth on every aspect of the universe, including lowly matter. By means of this fuller notion of God, St Thomas was able to refound and bring to perfection Aristotle’s realist metaphysics. He established five ways to prove, by reason alone, that there must be a God who is a creator that endows creatures with essence and existence, the ultimate components of created being.

The doctrine of creation in time led Aquinas to develop a perspective of a universe conducive to scientific exploration, one that was contingently created by God to have necessary laws. He and other scholastics convinced the Western world that such was the universe we live in, and exact science can only have a coherent basis in such a universe. The reason is that exact science must assume that the universe has rigorously consistent natural laws that can be discovered by rational minds. We should not be surprised, then, that scholastics coming after Aquinas directly prepared the way for the launching of modern science that was to take place in the seventeenth century. They did not hesitate to reject Aristotle’s physics, realising that God could endow inert matter with innate properties, and that matter did not have to be motivated to move. One among them, Jean Buridan, formulated landmark ideas about material movement, which were later used by the great scientists Galileo, Descartes, and Newton. This was the beginning of modern science, and it was built on a God idea that derived from a specific theological perspective.

Such is an historical example of religion contributing to science, and contributing to science to such a degree that we can say it gave birth to science, at least to science as we know it today.

4. Willful Creator God

There were other contexts in the post-Christian era where religion provided more of a hindrance than a help to philosophical and scientific explorations. Let us consider two examples.

Islam

(for the extended version of this section, see Robert Reilly’s The Closing of the Muslim Mind: How Intellectual Suicide Created the Modern Islamist)

There were some great Muslim philosophers, who made some important contributions to philosophy. I think especially of Alfarabi (+950 AD), who advanced philosophy’s conceptual toolbox in three major aspects:

1. the epoch-making distinction of essence and existence in created beings

2. the notion of the contingency of created beings, that is, their dependence at the level of being

3. the distinction between necessary and possible being, wherein necessary beings cannot not exist, for example, it is impossible for God not to exist; while possible beings can exist or not exist, for example, horses and centaurs.

There are other famous names, such as Avicenna and Averroes. However, the problem was that they did philosophy and science more in spite of their religion than under its influence.

This conflict between reason and faith had its origin in a dispute over the interpretation of the Koran. Muslims hold that Allah has a language and that that language is Arabic. Thus, language is not a merely human construct, but also belongs to God, at least in the sense of an ‘inner speech’. From this perspective, the text of the Koran is not so much the ideas of God expressed in the language of men as the precise thought and speech of God as God. The very letters and words are sacred. Thus, when one seeks to discover the meaning of those words, it would seem disrespectful to find multiple senses in them by a process of reasoning, and reject one while choosing another. Adhering to a literal interpretation for one passage and a figurative one to another becomes akin to superimposing human reason over the divine mind. In short, holding the text of the Koran to be so numinous that it is the words of God in the language of God makes all non-literal interpretations seem unorthodox.

This idea led to a conflict in early Muslim history, between ‘mutazilites’, who believed that the Koran should be interpreted in accordance with human reason, and the followers of Al-Ash’ari (+936 AD), who championed a strictly literal interpretation. The Asharites ended up winning, especially through the work of Al-Ash’ari’s foremost successor, Al-Ghazali (1058-1111). What this meant is that the Muslim world embraced, as orthodoxy, the idea that their sacred text was not to be reconciled with reason. As a result, Allah was not to be considered reasonable. Rather, Allah was not bound to any of the rules of logic or consistency; no limits whatsoever should be put on his will.

The God idea that results from this theology is that of a voluntarist God, a God who wills what he wills, without reason being able to find any intelligibility behind his decisions. At every moment, the whole of creation is utterly subject to his whims. In fact, there is only one agent in the universe: Allah. The creatures we see around us only seem to act.

Here is what Maimonides (1135-1204), a medieval Jewish philosopher living in the Muslim world, remarks about this system:

Most of the Muslim theologians believe that it must never be said that one thing is the cause of another; some of them who assumed causality were blamed for doing so … They believe that when a man has the will to do a thing and, as he believes, does it, the will has been created for him, then the power to conform to the will, and lastly the act itself. … Such is, according to their opinion, the right interpretation of the creed that God is efficient cause.

The upshot of this God idea is that the human mind is not able to do philosophy or science. Every cause that the human mind would ascribe to a given effect—fire is causing heat, gravity is causing the earth to move around the sun, my voice is causing the sound of my words—is false, since only Allah acts. Not only that, but ascribing an effect to any other cause than God would be stripping Allah of his total power over creation and so would be a disrespect to him.

Protestantism

(for the extended version of this section, see Hartmann Grisar’s Martin Luther: His Life and Work)

The idea of a voluntarist God entered Christianity mainly by way of two Catholic monks, William of Occam and Martin Luther. Occam is sometimes referred to as the “first Protestant”, though he remained a Catholic all his life, because he formulated a theology that later became incarnated in Protestantism. He had a desire similar to that of the Muslim theologians: he wanted to save the freedom of God by removing the reason of God. To do so, he claimed that God did have any ideas in mind when creating the world, ideas which would be embodied in the natures of God’s creatures. Creatures don’t have natures. Thus, the concepts that we form of the nature of creatures are false.

If such is the case, then we must profess ourselves agnostics in philosophy, since we cannot say what things are. The only territory left for knowledge is the data of our senses; this is why Occam’s system of thought leads to empiricism, the philosophy (!) that only sense knowledge is true knowledge of reality.

The Augustinian order to which Martin Luther belonged taught the ideas of Occam. Luther embraced the spirit of Occam, taking the latter’s trajectory to its full consequences, the total rejection of reason.

In the place of reason and human judgement as the ultimate reference for the choice of one’s philosophy and religion, Luther advocated blind adherence to the literal sense of the Bible, as interpreted privately by each individual. Since the literal sense of the Bible sometimes conflicts with reason (and so is not the true sense of the Bible), Luther had to remove from God any need to act reasonably. In other words, he had to think of the Biblical God in ways not very dissimilar from the way orthodox Muslims think of Allah.

For the Luther and the other Reformers, not only must we expect God to be arbitrary, but we must see that God needs to be arbitrary. If He put all knowledge in the Bible, then he needs to teach humans not to look for knowledge in other areas. The best way to do this would be to show them that their reason is not trustworthy. And what better way to prove to humans that their reason is not trustworthy than by confounding their reason?

Thus, by dint of their biblicist worldview, not only were the Reformers not interested in respecting reason and reconciling it with faith, they even needed to go out of their way to malign reason, so that reason could not compete with the literal sense of the Bible. They co-opted God to assist them in this project by painting a fantastic picture of a God who is arbitrary in his running of the universe. This sets up a situation where humans think that they have learned something from the world around them, but then God steps in with a revelation from the Bible to say, “No, that is only a trick of your mind. If I was consistent, your inference would be true. But I have not run the universe consistently, so that you will learn not to trust reason and instead will trust the Bible alone.”

Needless to say, such a God dissuades humans from doing philosophy and science as much as a voluntarist Allah. In fact, wherever the voluntarist God holds sway—whether it be in Islam, in Catholicism, or Protestantism—neither reason nor reality can be accorded their God-given rights. Those who worship a God with will but no reason tend to believe by an unreasoning act of the will and so tend to have no reasonable motive to understand the reality around them.

Conclusion

In this answer, we have seen four different God ideas, coming from cultures with a religious worldview, and the effects of those ideas on the pursuit of science and philosophy. We have not examined which of these God ideas is correct. That is an entirely other subject. We have only seen what impact those ideas have on the way that humans look at reality, as follows:

1. Crass pantheism – if God and the universe are seen to be the same thing, then humans do not expect there to be any intelligible order in the universe and so are discouraged from investigating it

2. Elaborate pantheism – if God is an intelligent principle within the universe that makes it move, then humans expect there to be order in the universe, which motivates them to do philosophy. But since they do not think that God has creatively designed each material thing, they tend to neglect science as we know it today, with its methods of measurement and experimentation.

3. Rational creator God – if God is a creator who makes a universe that is shot through with intelligibility, then humans are maximally motivated to investigate every nook and cranny—and so do science—and also to understand the order of the whole of reality, that is, do philosophy.

4. Willful creator God – if God is all power and will, but is not reasonable, then he will not allow creatures to be causes, or he will go out of his way to confound human reason. Either way, there is no reason for humans to investigate a universe that is the product of such a God.

(for the extended version of this answer, see chapters 4-7 of my book The Realist Guide to Religion and Science).

August 15, 2018

Reactions to the Big Bang Theory

1. Introduction

When Albert Einstein proposed his general theory of relativity in 1915, he was ushering in a new era of science. By means of his theory, scientists could, for the first time, construct physical models for the universe as a whole. Newton’s universe was infinite and the infinite cannot be measured. Einstein’s theory, however, required a finite universe, a universe that could both be tracked in its history and undergo mathematical modeling.

The Theory of Relativity quickly received several empirical confirmations, one being that it could calculate the orbit of Mercury around the sun with perfect accuracy, whereas the same calculation using Newton’s theory of gravitation contained statistical error. The most important confirmation of Einstein’s theory was Sir Arthur Eddington’s observation of a star shift during a solar eclipse in West Africa in 1919, a shift predicted by the theory of relativity.

These predictions, however, seemed minor compared to one remarked by a Catholic Belgian priest, Fr. Georges Lemaître. In a paper published in 1927, he pointed out that, if Einstein’s theory were correct, then heavenly bodies are technically not moving in the universe, but are rather moving the universe. In other words, the universe is expanding when heavenly bodies move farther and farther away from one another.

Lemaître went further in a book he published in 1931. If the universe is expanding, he reasoned, then to go back in time is to go back to a more contracted state of the universe. If we continue going back in time in this way, then we will eventually reach a point wherein all of the matter in the universe is compacted into a single point, something Lemaître referred to as a Primeval Atom, a phrase which he made the very title of his book. In this perspective, the entire matter/energy of our present universe started off in an enormously dense state at a single point and from there expanded over a long period of time up to the present day.

Lemaître’s idea was met with mixed reactions. British astronomer Fred Hoyle, for one, dismissed it out of hand, referring to it jokingly as the Big Bang Theory. Hoyle was the champion of a rival theory, called the Steady State Theory, which held that the universe is eternal and largely unchanging. Others took up the Big Bang Theory and tried to provide it empirical support.

Our objective in this multi-part article is to explore the attitude of three sets of people to Lemaître’s Big Bang Theory: atheist scientists, fundamentalist Protestants, and mainstream Catholics. After observing their reactions, we will consider whether there is solid empirical evidence for the theory.

2. Atheist scientists

Whenever we look at the reaction of this or that person to a certain event, we have to remember that it is impossible for any one of us to avoid bringing some personal bias to a given situation. If humans were mere intellects, raw thinking machines, then we could reasonably expect all of our reactions to be entirely objective. But humans are much more than what they know. They are also what they want and what they feel. Their reactions, therefore, are always some combination of intellect, will, and emotions.

It is our reason which helps us distinguish whether objectivity or subjectivity predominates in the reactions of those around us. The person reacting with rational argumentation is more objective and less biased, while the person reacting with emotional outburst is less objective and more biased.

All of this is by way of preface to considering the reaction of atheist scientists to the Big Bang Theory. They were an up and coming intellectual class starting with the wave of rationalism sweeping through the Western world in the 19th century. That wave was largely fueled by an explosion of scientific discovery. The rapid casting out of old and long-standing scientific errors worked like swelling agent on man’s all too easily inflated pride. Purely naturalistic explanations of everything under the sun—like the sun—became the rage. Many began to believe that science would eventually be able to explain everything in the universe, and do so without ever having recourse to the causality of God. The Holy Grail for unholy science soon became the goal of accounting for the existence of everything in the universe by mathematical laws alone.

Thomist philosophers know immediately that such an enterprise is doomed to failure, for the simple reason that mathematical laws do not explain the existence of anything; they only describe what things do, how things act. By and large, however, modern scientists do not understand this, for one characteristic that seems to dominate their tribe is a complete lack of philosophical knowledge. The reader does not have to rely on me for this statement; he can safely consult Einstein saying that “the man of science is a poor philosopher.”

Despite the fact that science can never even speak about the existence of things, much less assign a cause for their existence, atheistic scientists generally believe that they can use science to prove that the universe is the ultimate reality. When they embark on this quixotic enterprise, they understand that, to make the universe the ultimate reality, they have to endow it with the attributes of God. What are the attributes of God? God is eternal, He is unchanging, uncaused, infinite. That, then, is what the universe must be if it is to pretend to be a God substitute. But does science show that we live in such a universe?

The idea that the universe is infinite in space and time gained traction in scientific minds since the great Isaac Newton had put his weight behind it in the 1600s. There were, however, two strong scientific arguments against a universe without a beginning and without boundaries, both arguments being framed in the form of a paradox:

1. If the universe is eternal, then the force of gravitation has been working forever. If gravitation works forever, only two scenarios are possible: either all bodies get pulled together into a single body or no bodies come together. But neither of these is true.

2. If the universe is eternal, then the light of stars has been shining eternally. When stars shine forever, the night sky becomes entirely lit up as light eventually reaches the Earth from all directions. But the night sky is not all lit up, but is rather dark.

Fr Stanley Jaki notes with amazement in his book on this particular topic, The Paradox of Olbers’ Paradox, that the majority of scientists still maintained blind faith in the infinity of the universe in space and time, despite such solid arguments against it.

So far, so bad. Both reason and science indicate that the universe cannot be infinite. But how, one may ask, could a scientist maintain that the universe is unchanging? Well, clearly, he can’t without falling into utter absurdity. The best he can do is depict a universe that is unchanging in an approximate sense. This is what Fred Hoyle and his Steady-State crew did. They proposed that:

1. The stars are all approximately the same in composition and the same distance from one another.

2. The general character of the universe remains the same always, such that the universe is unchanging in its grand scheme.

3. The motions of all bodies in the universe are generally the same.

Clearly, such a universe is a poor substitute for God. Evidently, however, it was enough of a substitute for those who wanted it to be God, for the Steady-State Theory maintained a reputability in scientific circles long past its used-by date, which turned out to be extremely limited in time.

I could continue in this vein by speaking of other attempts by scientists, and especially the atheist types, to erect a scaffolding around the universe in order to hold up the divinity they wished to confer upon it.

There is no need for me to do so, however, for the main point that I wish to make can now be made with reasonable clarity, and that is that the Big Bang Theory makes all of the scaffolding come crashing down.

If the Big Bang Theory is true, the universe is finite in time, because it began with the initial burst of energy.

If the Big Bang Theory is true, the universe is finite in space, because it began at a single point and has since been expanding.

If the Big Bang Theory is true, the universe is forever in a state of change, because it is continually getting bigger, cooler, and less dense.

If the Big Bang Theory is true, the universe is surely caused by God, for what could possibly initiate a universe in such a way other than a Being of immense power that is outside of space and time?

This last point especially stuck in the craw of scientistic atheists. They knew that Christianity had long held to the belief that the universe is not eternal, but had a beginning in time. The last thing that they wanted to see was all of their efforts in science, their discoveries, their formulas, their experiments, and so on point ultimately to a dogma of the Christian faith, held on the basis of religious belief.

No one has expressed the disappointment more aptly than the late NASA astronomer Robert Jastrow:

For the scientist who has lived by his faith in the power of reason, the story ends like a bad dream. He has scaled the mountain of ignorance; he is about to conquer the highest peak; as he pulls himself over the final rock, he is greeted by a band of theologians who have been sitting there for centuries.

Later in this article, we will see that even atheist scientists had to accept the evidence for the Big Bang—though of course that did not convert many of them to God—but for now we just register their reaction to the theory: a reaction of intense dislike followed by an attempt to discredit and destroy the theory, and finishing with a begrudging acceptance.

3. Fundamentalist Protestants

We have just seen that atheist scientists were biased against the Big Bang Theory because it lent support for a dogma of Christianity. We will now see that fundamentalist Protestants are also biased against the theory because it does not lend support to that dogma in the way that they would like.

Under the Big Bang scenario, the development of the universe from an initial point of immense energy to a diverse collection of galaxies, stars and planetary systems takes many eons of time. While the theory indirectly implies that a being outside of space and time was at the origin of the universe, it directly asserts, by scientific argument, the precise conditions under which the universe had to develop. One of those conditions is a time period in the billions of years.

Fundamentalist Protestants, meanwhile, hold as dogma not just that God created the universe with a beginning in time, but also that He did so 6000 years ago and in a period of six, twenty-four hour days. For them, the time and the way that God created are just as dogmatic as the fact of God’s creation. This position today is commonly referred to as Young Earth Creationism (YEC).

The YEC stance stems directly from the fact that Protestantism is a text-based religion and not an institution-based religion. Protestants do not start with a divine institution that informs them on the supernatural truths that are necessary to reach salvation. They rather start with a text (compiled and transmitted across the centuries by Catholics) and seek to derive a set of revealed truths from that text.

They see that text as the only means which God has established to communicate saving truths to believers. This perspective is sometimes referred to as ‘biblicism’ because it makes the Bible the be all, end all source of religion. The Bible is made to play for Protestants the same role that the Church plays for Catholics. Just as the Church is the living voice of Jesus Christ for Catholics, so too the Bible is that voice for Protestants.

Those who over-divinize the Bible in this way tend to:

1. Interpret the Bible literally. To interpret the Bible literally here and allegorically there is to place oneself above the Bible and so above the divine mind.

2. Read the Bible as a science book as well as a spiritual book. The strictly literal sense of some passages of the Bible, especially Genesis, speaks of things which can be taken as scientific fact. Since deviating from the literal sense is to be irreverent to the Bible, those things must be taken as scientific fact.

3. Place the Bible above reason, instead of alongside it. When scientific data taken from a literal reading of God’s Word conflicts with scientific data taken from God’s nature, God’s Word must be upheld over God’s nature. It is human reason that has to interpret nature, but human reason does not have to be involved in taking a literal sense of the Bible. Because human reason can fail, the literal sense of the Bible is to be preferred over even the clearest conclusions of human reason.

Protestant biblicism sets fundamentalists on a beeline collision course with the Big Bang Theory. It leaves them with only two choices: reject all evidence for the Big Bang Theory or reject the Bible and Christian religion. An article from a 2013 issue of their Creation magazine sums it up this way:

The timescale in and of itself is not the important issue. It ultimately comes down to, “Does the Bible actually mean what it says?” The issue is about the trustworthiness of Scripture—compromising with long ages severely undermines the whole Gospel.

It undermines the whole Gospel IF you believe that a young age for the universe is part of the Gospel. And you believe that a young age for the universe is part of the Gospel only if you take your revealed truths from the Bible alone rather than take your revealed truths from Jesus Christ’s divine institution and then find them in the Bible.

4. Mainstream Catholics

This brings me to the Catholic reaction to the Big Bang Theory. I have already mentioned that the theory originated with a Belgian Catholic priest. Neither to him nor to the other Catholics of his day did the theory seem to violate any teaching of the Catholic faith. A short history of Catholic exegesis will help us understand why.

For the Fathers of the Church, the first rule of Biblical interpretation is to maintain the literal sense unless it is shown to be false. When that happens, it becomes obvious that the literal sense cannot be the sense intended by Scripture, because Scripture is the Word of God and so without error.

This rule teaches us that reason can be used to clarify the true meaning of Scripture. When the rule is followed, faith and reason, Bible and science, do not come into conflict. When the rule is not followed—when one is so attached to the literal sense that he clings to it in the face of contrary evidence—religion becomes unreasonable and subject to the mockery of the learned.

The two greatest thinkers in Christian history—Sts. Augustine and Thomas Aquinas—sternly warned Catholics not to interpret Scripture against reason. Here is St. Thomas summarizing St. Augustine in the Summa:

Since Sacred Scripture can be interpreted in many ways, one must not hold so firmly to a given interpretation such that, once that interpretation is clearly shown to be false, he presume to assert that the false interpretation is Scripture’s meaning, lest, by doing so, he expose Scripture to ridicule by non-believers, and close off for them the path to belief.

There have been many Catholic Scripture scholars in Church history who have interpreted Genesis 1 in a literal sense. They did so, however, in the spirit of the primal interpretational rule. As such, they were willing to cast aside a strictly literal sense if strong evidence was found to contradict it. They understood that certain supernatural truths of Genesis were non-negotiable—one God as creator of everything from nothing, creation in time, the direct creation of man, the unity of the human race, man’s superiority over other creatures on earth and over the heavenly bodies, man’s state of original justice and his fall, etc. Natural truths not underpinning those supernatural truths, however, were negotiable.

The time in which God created the universe and the way He had it develop are certainly among the negotiable truths, since whether God created in a long period of time or a short period changes nothing of the Catholic Faith. It was for this reason that the Fathers were fairly unanimous on the religious truths taught by Genesis 1, but were quite varied in their opinions on the scientific truths taught by the same.

St. Augustine’s opinion, the one favored by St. Thomas, was that God created everything at once, not in a period of six days. For him, the six day description was a teaching tool used by the sacred author to communicate religious truths in the most effective way possible.

In our age, a series of Popes have written encyclicals on Scripture clarifying the relationship between the Bible and science. Leo XIII was particularly clear on this question when he wrote the following in Providentissimus Deus:

[T]he sacred writers, or to speak more accurately, the Holy Spirit ‘who spoke by them, did not intend to teach men these things (that is to say, the essential nature of the things of the visible universe), things in no way profitable unto salvation.’ [St. Augustine, De Gen. ad litt., i., 9, 20] Hence they did not seek to penetrate the secrets of nature, but rather described and dealt with things in more or less figurative language, or in terms which were commonly used at the time and which in many instances are in daily use at this day, even by the most eminent men of science.

In the end, Catholics have freedom to embrace or reject the Big Bang Theory, for the Church considers it to be a question of science, not of religion. No doubt, most Protestants hold the same opinion. The difference, however, is that Protestants consistent with the spirit of their religion will read the Bible as a science book, while Catholics consistent with the spirit of Catholicism will not. The savvy Catholic exegete, on the contrary, will be careful to protect both faith and reason in his interpretation of the Bible, in order to avoid portraying religion as an exercise in irrationality.