Religion's Contribution to Philosophy and Science

What is religion’s contribution to science and philosophy?

It is a person’s worldview that determines how he or she looks at reality. How they look at reality determines whether they think it is knowable and how they think it should be known. In this sense, then, a person’s worldview determines how that person does science and philosophy.

To illustrate this abstract truth, consider a situation where girl meets boy. They go on a date. If the girl finds out that he is a jerk, she does not want to get to know him better and cancels future meetings. If the girl finds that he is a prince charming, she ardently desires to get to know him better and ultimately spends the rest of her life with him. In either case, it is her view of the boy that determines whether she wants to know him more or ignore him. Our worldview does the same thing for us in relation to reality. It tells us how to look at reality and, in doing so, determines whether we want to know more about it or ignore it.

Where have people’s worldview typically come from? From religion. This was true of all of the civilizations of the past, before the advent of our current secular societies in the 19th century. It was true of the pre-Christian cultures: the Indians, the Chinese, the Babylonians, the Egyptians, the Jews, the Greeks, the Romans, the Mayans, the Incans, the Aztecs, and so on. This was also true of Christian and Islamic cultures.

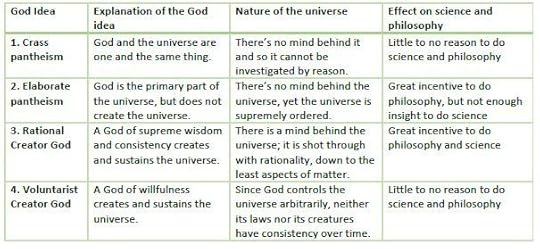

What effect did the religions of these cultures have on the pursuit of science and philosophy? Well, it all depended on the ultimate explanation which the various religions gave to the universe. This could be called their ‘God idea’ and it has the biggest impact on a religion-driven worldview. That idea says whether reality should be explored or ignored.

There are four different God ideas, coming from four different species of religion, that I would like to consider, in relation to their influence on the pursuit of science and philosophy. This table will summarize my view and then we will get into the details.

1. Crass pantheism: God is the universe

(for the extended version of this section, see Stanley Jaki’s Science And Creation: From Eternal Cycles To An Oscillating Universe)

Pagan religions were universally pantheist. They all struggled to make sense of the world around them, but their solutions were overly simplistic. One thing that especially struck the pagans was the cycles they observed in nature. The recurrence of the seasons, the rising and the setting of the sun, the waxing and waning of the moon, the rotations of the heavens, the births and deaths of organic life, are all so many evidences that circular patterns are built into the very fabric of reality.

If the mind makes this observation and goes no further, then cyclical change does not present itself as an aspect of reality, but as the whole of reality. A key characteristic of circles is that they participate in the infinite. They have no edges, no beginning and no end. To illustrate this, imagine someone driving around a perfectly circular track at a constant speed, the wheels always turned to the same angle. Under these conditions, the driver can go around the track forever without a single change (ignoring friction and fuel consumption). And so, if the heavens are turning around in circles, and Earth processes are going around in circles, then perhaps the heavens and the Earth are eternal. And if they are eternal, then perhaps they are the ultimate reality. The universe and God are one. Such was the inference of the pantheists.

When this crass pantheism becomes the master thought of a civilization, and that culture is unable to make further progress in causal reasoning, then it is only natural that some mythology will start to encrust itself around that metaphysical kernel which is still in a stage of philosophical infancy. In other words, thinkers will just arrest their philosophical speculation there and, instead of continuing to investigate reality with reason, they will just tell stories about it. The Greek word for ‘story’ is mythos, and this is where we get the word ‘mythology’.

Belief that the universe and God are one and the same thing is a ‘God idea’, and it is not a very healthy one for the intellectual pursuits of philosophy and science. The reason is that pantheism projects a picture of a universe that has no mind behind it. It just it what it is and so you must not expect to understand it. Precisely because you cannot understand it or even expect to understand it, you make up tall tales about it.

Take, for instance, the mythology of Buddhism, the idea that humans reincarnate again and again until, or unless, they reach nirvana. This is an interesting story, but it is not true. The only way for a human to become a horse is by changing its very being. But, changing its very being, it will no longer be a human. Thus, it is impossible for a human to reincarnate and retain his personal identity at the same time.

The Buddhists took this idea from all of the cycles that they noticed in nature, especially the cycles of life and death manifested in the seasons. They assumed, from these cycles, that humans also continually die and come to life again. They also assumed that these cycles were eternal.

The effect of this idea upon intellectual endeavor can be devastating. Consider how you would feel if you were stuck on a wheel that was endlessly turning and you had no way to relate or talk to the one operating the wheel. The wheel just turned and turned and there was nothing you could do about it, no one who would listen, no way to stop the turning or make any sense out of it.

If such were your plight, you might very well seek to escape from the turning by shutting yourself off mentally from the reality outside of you and trying to reach a state of total escape, a state where you do not even realize what is happening to you, a state of utter numbness. Well, that state is the nirvana that the ancient Buddhists sought and they sought it because they saw reality as going around in endless and mindless cycles.

The take home lesson is this: if the universe is seen as being the ultimate principle, then it is not seen as having a mind behind it which would put any rational order into it. And if your culture does not hold that the universe is shot through with rationality, then its ethos is one that discourages humans from the investigative pursuits of science and philosophy.

To be motivated to do philosophy and science, humans needed to break free from mythology and needed to form the idea of a transcendent, all-wise God behind the universe who creates it and builds rationality into its very fabric. The Greeks accomplished the former and gave birth to philosophy; the Catholic Middle Ages did the latter and gave birth to science.

2. Elaborate pantheism: God within the universe, but not the universe

The first recorded culture which set reason free from mythology to systematically pursue a total causal knowledge of reality was the Greeks’. The metaphysician Thales (624–546 BC) put the Greeks on the trail of hunting for ultimate causes when he argued, by means of reason, for water as being the ultimate principle of the universe. This idea of the principle of all reality being within the universe, instead of identifying the ultimate with the universe, I call ‘elaborate pantheism’.

Thales’s challenge helped the Greeks set mythos to one side, in order to see what logos or ‘reason’ could do. They started forming, by means of philosophical reasoning alone, in independence from religion, more sophisticated notions of God than those of mythology, ones wherein God was a cause accounting for reality, not one wherein stories about gods accounted for it. Schools of philosophy sprouted like mushrooms in the Hellenic world from around 550 to about 350 BC, each with their own answer to the ultimate questions.

The story of those 200 years is fascinating, but we only have time to bring up the thinker that culminated the Greek philosophical Olympic games, namely, Aristotle. His powerful genius was able to set down the rules for human thought (logic), formulate an epistemology (realism) that matches exactly with our human faculties of knowing, and develop a powerful and even scientific conceptual apparatus for philosophic endeavor. To him we owe the invaluable distinctions which form the only launching pad from which a philosopher can hope to safely discover the first principle of reality: act and potency, substance and accident, matter and form, the four causes, the ten categories.

By means of his insights, Aristotle accomplished something extraordinary: he used philosophy as a bridge to religion. He constructed a theology by means of reason alone, something we today refer to as ‘natural theology’, also known as metaphysics. Starting with the observation of the nature of movement around us, he argued, conclusively, that some immaterial, unchanging, most perfect being must be at the ultimate cause of all movement. By all movement, he meant any movement whatsoever. If there is no First Mover at every moment, then all movement ceases.

Aristotle’s First Mover somehow did not completely transcend the universe, still being in it in some way, and thus Aristotle was still something of a pantheist. He had the Prime Mover perform his work of causing all movement by attracting everything in the universe to himself. Thus, Aristotle did not see God as moving things by creating them; he rather saw God as moving things by motivating them.

Aristotle’s philosophy was fantastic, but his inability to see God as a creator meant that his physics was extremely deficient. He explained all physical motion in terms of attraction and so claimed that heavier balls fall to the ground faster than lighter ones, that rocks fall to the ground because of an attraction to their natural place, and that the air around a projectile aids its upward movement rather than impedes it.

Because Aristotle was so amazing in just about every intellectual discipline, both his good philosophy and his false science were widely accepted in the centuries that followed. In the end, it would take 1500 years before his physics was rejected and replaced with what we now know as science and the scientific method.

In the case of the pagans, then, their religions impeded, to a greater or lesser degree, the fruitful pursuit of philosophy and science. It was only when mythological paganism was ignored that the great Greek philosophers were able to make their irreplaceable contribution to all future thought.

But, unlike philosophy, which was born by ignoring religion, science was born because of religion, specifically by a religion that believed in a God who builds rationality into every nook and cranny of his material creation, and that created a civilization wherein that God idea informed the attitude of its citizens towards reality.

3. Rational Creator God

(for the extended version of this section, see Edward Grant’s The Foundations of Modern Science in the Middle Ages: Their Religious, Institutional and Intellectual Contextsor James Hannam’s Genesis of Science or Stanley Jaki’s The Savior Of Science)

We have seen two God ideas so far: that of the crass pantheists, coming from mythology, an obstacle to intellectual pursuits; that of Aristotle, who used reason alone to form the God idea of a Prime Mover who orders the movement of the universe by providing it a goal. Now, we come to the God idea of the Catholic Middle Ages, especially as conceptualized in the Summa Theologica of St. Thomas Aquinas.

For Aquinas, God is a wise creator, embedding a rational order into all of creation, and so making its utmost recesses intelligible to human minds; He is good, conferring worth on every aspect of the universe, including lowly matter. By means of this fuller notion of God, St Thomas was able to refound and bring to perfection Aristotle’s realist metaphysics. He established five ways to prove, by reason alone, that there must be a God who is a creator that endows creatures with essence and existence, the ultimate components of created being.

The doctrine of creation in time led Aquinas to develop a perspective of a universe conducive to scientific exploration, one that was contingently created by God to have necessary laws. He and other scholastics convinced the Western world that such was the universe we live in, and exact science can only have a coherent basis in such a universe. The reason is that exact science must assume that the universe has rigorously consistent natural laws that can be discovered by rational minds. We should not be surprised, then, that scholastics coming after Aquinas directly prepared the way for the launching of modern science that was to take place in the seventeenth century. They did not hesitate to reject Aristotle’s physics, realising that God could endow inert matter with innate properties, and that matter did not have to be motivated to move. One among them, Jean Buridan, formulated landmark ideas about material movement, which were later used by the great scientists Galileo, Descartes, and Newton. This was the beginning of modern science, and it was built on a God idea that derived from a specific theological perspective.

Such is an historical example of religion contributing to science, and contributing to science to such a degree that we can say it gave birth to science, at least to science as we know it today.

4. Willful Creator God

There were other contexts in the post-Christian era where religion provided more of a hindrance than a help to philosophical and scientific explorations. Let us consider two examples.

Islam

(for the extended version of this section, see Robert Reilly’s The Closing of the Muslim Mind: How Intellectual Suicide Created the Modern Islamist)

There were some great Muslim philosophers, who made some important contributions to philosophy. I think especially of Alfarabi (+950 AD), who advanced philosophy’s conceptual toolbox in three major aspects:

1. the epoch-making distinction of essence and existence in created beings

2. the notion of the contingency of created beings, that is, their dependence at the level of being

3. the distinction between necessary and possible being, wherein necessary beings cannot not exist, for example, it is impossible for God not to exist; while possible beings can exist or not exist, for example, horses and centaurs.

There are other famous names, such as Avicenna and Averroes. However, the problem was that they did philosophy and science more in spite of their religion than under its influence.

This conflict between reason and faith had its origin in a dispute over the interpretation of the Koran. Muslims hold that Allah has a language and that that language is Arabic. Thus, language is not a merely human construct, but also belongs to God, at least in the sense of an ‘inner speech’. From this perspective, the text of the Koran is not so much the ideas of God expressed in the language of men as the precise thought and speech of God as God. The very letters and words are sacred. Thus, when one seeks to discover the meaning of those words, it would seem disrespectful to find multiple senses in them by a process of reasoning, and reject one while choosing another. Adhering to a literal interpretation for one passage and a figurative one to another becomes akin to superimposing human reason over the divine mind. In short, holding the text of the Koran to be so numinous that it is the words of God in the language of God makes all non-literal interpretations seem unorthodox.

This idea led to a conflict in early Muslim history, between ‘mutazilites’, who believed that the Koran should be interpreted in accordance with human reason, and the followers of Al-Ash’ari (+936 AD), who championed a strictly literal interpretation. The Asharites ended up winning, especially through the work of Al-Ash’ari’s foremost successor, Al-Ghazali (1058-1111). What this meant is that the Muslim world embraced, as orthodoxy, the idea that their sacred text was not to be reconciled with reason. As a result, Allah was not to be considered reasonable. Rather, Allah was not bound to any of the rules of logic or consistency; no limits whatsoever should be put on his will.

The God idea that results from this theology is that of a voluntarist God, a God who wills what he wills, without reason being able to find any intelligibility behind his decisions. At every moment, the whole of creation is utterly subject to his whims. In fact, there is only one agent in the universe: Allah. The creatures we see around us only seem to act.

Here is what Maimonides (1135-1204), a medieval Jewish philosopher living in the Muslim world, remarks about this system:

Most of the Muslim theologians believe that it must never be said that one thing is the cause of another; some of them who assumed causality were blamed for doing so … They believe that when a man has the will to do a thing and, as he believes, does it, the will has been created for him, then the power to conform to the will, and lastly the act itself. … Such is, according to their opinion, the right interpretation of the creed that God is efficient cause.

The upshot of this God idea is that the human mind is not able to do philosophy or science. Every cause that the human mind would ascribe to a given effect—fire is causing heat, gravity is causing the earth to move around the sun, my voice is causing the sound of my words—is false, since only Allah acts. Not only that, but ascribing an effect to any other cause than God would be stripping Allah of his total power over creation and so would be a disrespect to him.

Protestantism

(for the extended version of this section, see Hartmann Grisar’s Martin Luther: His Life and Work)

The idea of a voluntarist God entered Christianity mainly by way of two Catholic monks, William of Occam and Martin Luther. Occam is sometimes referred to as the “first Protestant”, though he remained a Catholic all his life, because he formulated a theology that later became incarnated in Protestantism. He had a desire similar to that of the Muslim theologians: he wanted to save the freedom of God by removing the reason of God. To do so, he claimed that God did have any ideas in mind when creating the world, ideas which would be embodied in the natures of God’s creatures. Creatures don’t have natures. Thus, the concepts that we form of the nature of creatures are false.

If such is the case, then we must profess ourselves agnostics in philosophy, since we cannot say what things are. The only territory left for knowledge is the data of our senses; this is why Occam’s system of thought leads to empiricism, the philosophy (!) that only sense knowledge is true knowledge of reality.

The Augustinian order to which Martin Luther belonged taught the ideas of Occam. Luther embraced the spirit of Occam, taking the latter’s trajectory to its full consequences, the total rejection of reason.

In the place of reason and human judgement as the ultimate reference for the choice of one’s philosophy and religion, Luther advocated blind adherence to the literal sense of the Bible, as interpreted privately by each individual. Since the literal sense of the Bible sometimes conflicts with reason (and so is not the true sense of the Bible), Luther had to remove from God any need to act reasonably. In other words, he had to think of the Biblical God in ways not very dissimilar from the way orthodox Muslims think of Allah.

For the Luther and the other Reformers, not only must we expect God to be arbitrary, but we must see that God needs to be arbitrary. If He put all knowledge in the Bible, then he needs to teach humans not to look for knowledge in other areas. The best way to do this would be to show them that their reason is not trustworthy. And what better way to prove to humans that their reason is not trustworthy than by confounding their reason?

Thus, by dint of their biblicist worldview, not only were the Reformers not interested in respecting reason and reconciling it with faith, they even needed to go out of their way to malign reason, so that reason could not compete with the literal sense of the Bible. They co-opted God to assist them in this project by painting a fantastic picture of a God who is arbitrary in his running of the universe. This sets up a situation where humans think that they have learned something from the world around them, but then God steps in with a revelation from the Bible to say, “No, that is only a trick of your mind. If I was consistent, your inference would be true. But I have not run the universe consistently, so that you will learn not to trust reason and instead will trust the Bible alone.”

Needless to say, such a God dissuades humans from doing philosophy and science as much as a voluntarist Allah. In fact, wherever the voluntarist God holds sway—whether it be in Islam, in Catholicism, or Protestantism—neither reason nor reality can be accorded their God-given rights. Those who worship a God with will but no reason tend to believe by an unreasoning act of the will and so tend to have no reasonable motive to understand the reality around them.

Conclusion

In this answer, we have seen four different God ideas, coming from cultures with a religious worldview, and the effects of those ideas on the pursuit of science and philosophy. We have not examined which of these God ideas is correct. That is an entirely other subject. We have only seen what impact those ideas have on the way that humans look at reality, as follows:

1. Crass pantheism – if God and the universe are seen to be the same thing, then humans do not expect there to be any intelligible order in the universe and so are discouraged from investigating it

2. Elaborate pantheism – if God is an intelligent principle within the universe that makes it move, then humans expect there to be order in the universe, which motivates them to do philosophy. But since they do not think that God has creatively designed each material thing, they tend to neglect science as we know it today, with its methods of measurement and experimentation.

3. Rational creator God – if God is a creator who makes a universe that is shot through with intelligibility, then humans are maximally motivated to investigate every nook and cranny—and so do science—and also to understand the order of the whole of reality, that is, do philosophy.

4. Willful creator God – if God is all power and will, but is not reasonable, then he will not allow creatures to be causes, or he will go out of his way to confound human reason. Either way, there is no reason for humans to investigate a universe that is the product of such a God.

(for the extended version of this answer, see chapters 4-7 of my book The Realist Guide to Religion and Science).

Published on August 20, 2018 01:36

•

Tags:

catholicism, god, islam, middle-ages, philosophy, protestantism, religion, science

No comments have been added yet.