Juho Pohjalainen's Blog: Pankarp - Posts Tagged "bugbears"

Bugbears, and other things that go bump in the night

So what exactly is Peal? What does it mean to be a "bugbear", apart from some small and timid prey animal? Let's try to figure them out.

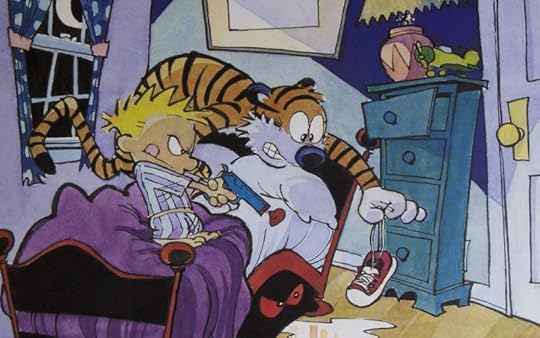

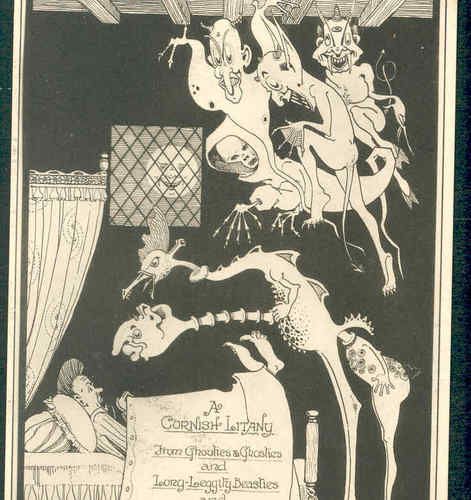

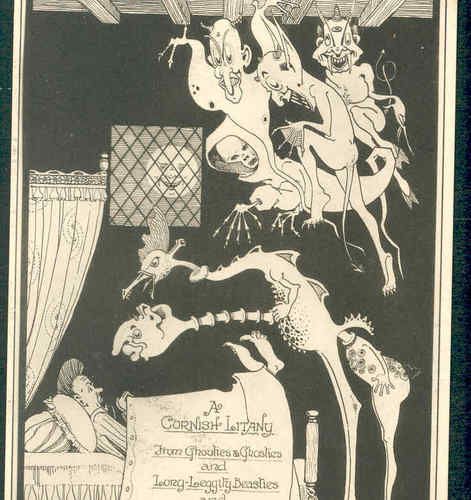

When you're a small child, darkness is a living and deathly thing in a way it never again will be as you grow up. Things live under your bed, in your closet, creaking up in the attic or down in the basement... or looking at you through your bedroom window when the lights are shut. The hollow trees, under roots, abandoned buildings, empty playgrounds, dark alleyways, even your dreams - all are teeming with life.

You never see a bogeyman, but you know it's there. Stalking. Waiting. Even as an adult, you're not always sure that you're alone.

So the first question I asked was: "Why do they hide?"

The usual answer, in fairy tales and literature, is that they're predators that are just waiting for you to lower your guard so that they might pounce up and devour you. As dreadful as the empty darkness and occasional glowing pair of eyes is, it's still vastly preferable to the true terror of what they look like.

I flipped the premise around: what if they hid not because they're predators, but because they're the prey?

They're small and weak, scared of all the big loud folk like you and I, or wolves and eagles - but they're quick on their feet and good at laying low. They almost never come out in the open if they can at all help it, so most people don't even believe they exist, let alone know that they're not all that big or scary or toothy after all.

If you're a small child living out in a small village or farm, or an ancient manor or castle, and like to explore your surroundings... you might just meet one. They aren't that scared of children. But even then, odds are low - and odds of you remembering it, and not chalking it up as overactive imagination of childhood, probably won't be much higher.

And then, the natural next question... what if one was forced out of hiding? What if they lost their home and found themselves in the daylight sun, at the road to faraway lands and places?

It would be a highly uncomfortable and terrifying experience to the poor creature... and therefore make for a great story premise.

It's exactly what happened to Peal, after all. He found himself as a prey out in clear view... forced to take a page or two out of the book of the other kind of bugbears - and become more like a predator.

I intended to tell a little more about bugbears, their appearance and culture and what they were meant to represent, at the beginning of The Straggler's Mask - but in the end I cut most of these away, shoving the rest down into footnotes, so that the story itself might pick up faster without having to wade through all this exposition first. It probably worked a little better like that, but it still wasn't entirely ideal... and maybe it started a bit slow anyway.

Perhaps, if I ever end up writing an epic trilogy of books where Peal has to wander to a distant volcano and throw the palarum in, I can start it with a prologue called On Bugbears.

When you're a small child, darkness is a living and deathly thing in a way it never again will be as you grow up. Things live under your bed, in your closet, creaking up in the attic or down in the basement... or looking at you through your bedroom window when the lights are shut. The hollow trees, under roots, abandoned buildings, empty playgrounds, dark alleyways, even your dreams - all are teeming with life.

You never see a bogeyman, but you know it's there. Stalking. Waiting. Even as an adult, you're not always sure that you're alone.

So the first question I asked was: "Why do they hide?"

The usual answer, in fairy tales and literature, is that they're predators that are just waiting for you to lower your guard so that they might pounce up and devour you. As dreadful as the empty darkness and occasional glowing pair of eyes is, it's still vastly preferable to the true terror of what they look like.

I flipped the premise around: what if they hid not because they're predators, but because they're the prey?

They're small and weak, scared of all the big loud folk like you and I, or wolves and eagles - but they're quick on their feet and good at laying low. They almost never come out in the open if they can at all help it, so most people don't even believe they exist, let alone know that they're not all that big or scary or toothy after all.

If you're a small child living out in a small village or farm, or an ancient manor or castle, and like to explore your surroundings... you might just meet one. They aren't that scared of children. But even then, odds are low - and odds of you remembering it, and not chalking it up as overactive imagination of childhood, probably won't be much higher.

And then, the natural next question... what if one was forced out of hiding? What if they lost their home and found themselves in the daylight sun, at the road to faraway lands and places?

It would be a highly uncomfortable and terrifying experience to the poor creature... and therefore make for a great story premise.

It's exactly what happened to Peal, after all. He found himself as a prey out in clear view... forced to take a page or two out of the book of the other kind of bugbears - and become more like a predator.

I intended to tell a little more about bugbears, their appearance and culture and what they were meant to represent, at the beginning of The Straggler's Mask - but in the end I cut most of these away, shoving the rest down into footnotes, so that the story itself might pick up faster without having to wade through all this exposition first. It probably worked a little better like that, but it still wasn't entirely ideal... and maybe it started a bit slow anyway.

Perhaps, if I ever end up writing an epic trilogy of books where Peal has to wander to a distant volcano and throw the palarum in, I can start it with a prologue called On Bugbears.

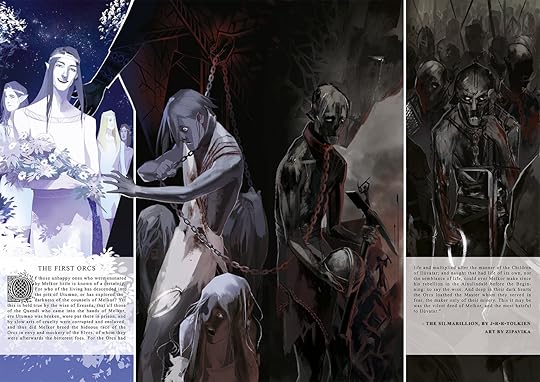

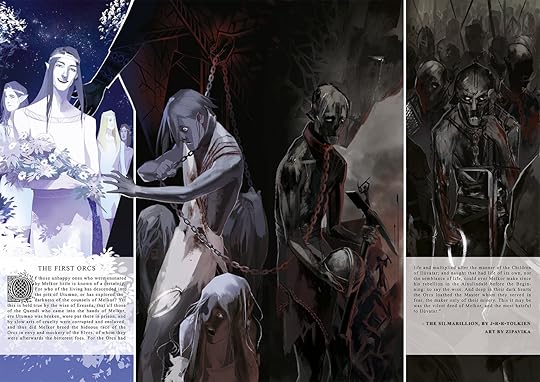

Orcs - Fantasy, Racial Familiarity, and Mundanity

I've seen a lot of discourse about fantasy racism these past couple days, especially with the context of orcs. This got me thinking about such racial matters in general. I thought I'd throw in my own two cents.

Tolkien - the father of modern fantasy - spawned his nonhuman races out of the old human mythology, fairy tales, and shared consciousness. Elves were like humans except far more magical and spiritually connected to the world; orcs were then the result of basically Lucifer himself getting his grubby hands on some elves; dwarves were the creation of a different god, dwellers under the earth, resilient as stone and greedy for gold and other shining metals; finally, the hobbits just sort of showed up, pudgy little folk with a love for idyllic life and peace, the closest to regular human. Some of them had in common with real-life nationalities and cultures - according to Tolkien himself, dwarves have more than a touch of Jewish in them, orcs Mongolian, and hobbits of course are basically British countryside dwellers - but these had a fairly minor role in their creation, helped by the man himself disliking allegory. All of them were also quite insular and had little to do with the businesses of other races: the Council of Elrond, the races coming together to address a grave issue, was an anomaly that was noted in-universe. On the whole they had strongly mythical roots, and drip with magical and fantastic flavour. All was well.

Then Dungeons & Dragons poached them into its great big fantasy patchwork. Now any player could roll up an elf, a dwarf, or ahobbi halfling; and every DM liked to use orcs as their basic mooks. Half-elves were codified into a race of their own, and soon after, so were the half-orcs... with fairly disturbing implications for the latter, at first. Gnomes were brought along from elsewhere, the enemy ranks swelled with kobolds and gnolls and others, and soon the world teemed with all manner of fantasy races great and small - and they quickly grew a familiar, even a mundane, sight in any fantasy setting.

And once you grow familiar with something, the next step is to explore and expand - to stretch its definitions, to ponder its identity, and to deconstruct what it all means. It didn't take long before the players wanted to be the orc rather than kill it, be it in a game of flipped perspectives where the whole party took up the role of the bad guys, or as a singular heroic individual who's fled home and wants to do good things, or a half-orc whose parents actually loved one another, or an orc wizard, or really just about anything else. At this stage, your imagination is the limit.

By now it seems like D&D's become the new standard bearer of fantasy - the introduction of the concept for most people, the originator of new ideas, and the wellspring of new fantasy and literature. It's next to impossible to write a fantasy story without it having been influenced by D&D in some way or the other - either by embracing it, or by consciously rejecting it. In it, magic and fantasy are a pretty standard fare, all over the place and accessible to everyone. The new races it added later on - genasi, tiefling, and dragonborn among others - followed this trend, each having their cultures and their nations and each blending in with humans just fine. It all tends towards the melting-pot feel, very much a modern concept... and indeed tied to modern sensibilities and attitudes in many other ways as well, the interpretations of morality and good and evil, the ideas of equality and inclusiveness.

All of this finally culminates to the topic of the present - racism. The big question on everyone's lips is, are orcs racist? Do they have to be racist? How to fix it?

But I reject these, and instead bring forth a whole other issue: What difference is there between these races, and plain old humans? How are they not just humans with tusks or pointed ears and other meaningless window-dressing?

The metamorphosis - the mundanization - is now complete. Through the twists and branches of a hundred-year-old evolutionary tree, the roots of mythology are now forgotten. Through intense familiarization and numerous deconstructions and parodies, the magic and fantasy is lost. "Fantasy" is no longer a description, but a genre, with medieval technology and various squat bearded and pointy-eared and green tusked people. The "orc" is no longer a strange mythical horror, he's your neighbour. The cultural counterparts and allegories, once a minor footnote, have grown to the forefront of their identity - because at this point, what else is there?

This is the great underlying issue for me - the dragon that gnaws at the tree of fantasy. I solve it by taking several big steps back. I grab all the nonhuman races and hide them back into the corners of the earth. You have to go looking for them, and therefore they remain fantastic and weird.

But where Tolkien tapped into mythology for his inspiration, I tend to look outward, into the realm of science fiction. My races tend to be substantially more different from humans, with many physical and mental traits that we might find utterly alien, just as they would never understand many facets of humanity.

Peal is not human, and I emphasize this inhumanity whenever it would be relevant. His size, his senses, his natural habitat, the faiths and superstitions drummed into him as a youth, all serve to separate him from humanity even after he's spent many years living among us. He still considers us weird or disgusting in many ways, while we in turn often find his way of thinking difficult to understand. It is a constant theme in the stories starring him - how humans might be viewed from an outsider's perspective.

I still have elves and orcs around, but you're not going to see them any more than you're going to see bugbears, which is very little indeed. I hope that I can maintain their fantastic elements forevermore.

Tolkien - the father of modern fantasy - spawned his nonhuman races out of the old human mythology, fairy tales, and shared consciousness. Elves were like humans except far more magical and spiritually connected to the world; orcs were then the result of basically Lucifer himself getting his grubby hands on some elves; dwarves were the creation of a different god, dwellers under the earth, resilient as stone and greedy for gold and other shining metals; finally, the hobbits just sort of showed up, pudgy little folk with a love for idyllic life and peace, the closest to regular human. Some of them had in common with real-life nationalities and cultures - according to Tolkien himself, dwarves have more than a touch of Jewish in them, orcs Mongolian, and hobbits of course are basically British countryside dwellers - but these had a fairly minor role in their creation, helped by the man himself disliking allegory. All of them were also quite insular and had little to do with the businesses of other races: the Council of Elrond, the races coming together to address a grave issue, was an anomaly that was noted in-universe. On the whole they had strongly mythical roots, and drip with magical and fantastic flavour. All was well.

Then Dungeons & Dragons poached them into its great big fantasy patchwork. Now any player could roll up an elf, a dwarf, or a

And once you grow familiar with something, the next step is to explore and expand - to stretch its definitions, to ponder its identity, and to deconstruct what it all means. It didn't take long before the players wanted to be the orc rather than kill it, be it in a game of flipped perspectives where the whole party took up the role of the bad guys, or as a singular heroic individual who's fled home and wants to do good things, or a half-orc whose parents actually loved one another, or an orc wizard, or really just about anything else. At this stage, your imagination is the limit.

By now it seems like D&D's become the new standard bearer of fantasy - the introduction of the concept for most people, the originator of new ideas, and the wellspring of new fantasy and literature. It's next to impossible to write a fantasy story without it having been influenced by D&D in some way or the other - either by embracing it, or by consciously rejecting it. In it, magic and fantasy are a pretty standard fare, all over the place and accessible to everyone. The new races it added later on - genasi, tiefling, and dragonborn among others - followed this trend, each having their cultures and their nations and each blending in with humans just fine. It all tends towards the melting-pot feel, very much a modern concept... and indeed tied to modern sensibilities and attitudes in many other ways as well, the interpretations of morality and good and evil, the ideas of equality and inclusiveness.

All of this finally culminates to the topic of the present - racism. The big question on everyone's lips is, are orcs racist? Do they have to be racist? How to fix it?

But I reject these, and instead bring forth a whole other issue: What difference is there between these races, and plain old humans? How are they not just humans with tusks or pointed ears and other meaningless window-dressing?

The metamorphosis - the mundanization - is now complete. Through the twists and branches of a hundred-year-old evolutionary tree, the roots of mythology are now forgotten. Through intense familiarization and numerous deconstructions and parodies, the magic and fantasy is lost. "Fantasy" is no longer a description, but a genre, with medieval technology and various squat bearded and pointy-eared and green tusked people. The "orc" is no longer a strange mythical horror, he's your neighbour. The cultural counterparts and allegories, once a minor footnote, have grown to the forefront of their identity - because at this point, what else is there?

This is the great underlying issue for me - the dragon that gnaws at the tree of fantasy. I solve it by taking several big steps back. I grab all the nonhuman races and hide them back into the corners of the earth. You have to go looking for them, and therefore they remain fantastic and weird.

But where Tolkien tapped into mythology for his inspiration, I tend to look outward, into the realm of science fiction. My races tend to be substantially more different from humans, with many physical and mental traits that we might find utterly alien, just as they would never understand many facets of humanity.

Peal is not human, and I emphasize this inhumanity whenever it would be relevant. His size, his senses, his natural habitat, the faiths and superstitions drummed into him as a youth, all serve to separate him from humanity even after he's spent many years living among us. He still considers us weird or disgusting in many ways, while we in turn often find his way of thinking difficult to understand. It is a constant theme in the stories starring him - how humans might be viewed from an outsider's perspective.

I still have elves and orcs around, but you're not going to see them any more than you're going to see bugbears, which is very little indeed. I hope that I can maintain their fantastic elements forevermore.

Peal is Not Human - a mind map

I've said before that I like it when the nonhuman races and creatures are depicted as legitimately alien, rather than just regular folks with pointy ears and a bit of fur and what have you. As an experiment, I put up a mind map about all the ways Peal's nonhumanity affects his character. I was delighted when I could trace just about all of him to him being what he was.

Here is the full thing if you'd like to learn more of him. Truthfully it ended up as a bit of a mess.

Here is the full thing if you'd like to learn more of him. Truthfully it ended up as a bit of a mess.

Published on June 24, 2020 11:21

•

Tags:

aliens, bugbears, fantasy, fantasy-races, inhumanity, mind-map, mind-maps, peal

Pankarp

Pages fallen out of Straggler's journal, and others.

Pages fallen out of Straggler's journal, and others.

...more

- Juho Pohjalainen's profile

- 352 followers