R.L. LaFevers's Blog, page 3

January 1, 2018

Embracing 2018

I have spent a lot of time thinking about this past year and trying to decide what my word for 2018 would be. That’s when I realized I never picked a word for 2017. I’m not sure I could have come up with a word that would have fully encompassed all that 2017 has held. It started with so much uncertainty: Physically—was I ever going to make significant progress in getting stronger and reclaiming some of the vitality I used to have? Professionally: Would I truly be able to write a full length book again? Did I even remember HOW to write a book? And then personally, was I ever going to stabilize and feel like ME again.I had no words, only questions. Maybe that was my word for 2017—simply a ?

I have spent a lot of time thinking about this past year and trying to decide what my word for 2018 would be. That’s when I realized I never picked a word for 2017. I’m not sure I could have come up with a word that would have fully encompassed all that 2017 has held. It started with so much uncertainty: Physically—was I ever going to make significant progress in getting stronger and reclaiming some of the vitality I used to have? Professionally: Would I truly be able to write a full length book again? Did I even remember HOW to write a book? And then personally, was I ever going to stabilize and feel like ME again.I had no words, only questions. Maybe that was my word for 2017—simply a ?

The year held many things—some sad, some harrowing, some discouraging. But it also held great joy and progress and hope and lots and lots of baby steps.

My father in law passed away after a long struggle with Alzheimers.

My son got married to a wonderful girl whom we adore.

My other son found a job a career tailor made for him where he is happy and challenged and is able to make a contribution.

Not only did I remember how to write, but I wrote six drafts of the longest flippin’ book I have ever written.

Wildfires raged through the area, evacuating tens of thousands—including us—and came far, far closer to our house than we would have wished.

And then, on Winter Solstice, my stepfather of 35 years passed away.

So many goodbyes, but so many new beginnings as well, proving that life is nothing if not change.

Finally, just this morning I settled on my 2018 word: Embrace. Even as the word slipped into my consciousness, I saw all the ways it would apply. Embracing change was simply the beginning.

Embrace—to hold close, to pull towards oneself, to accept or support, to include.

As 2017 drew to a close, I found myself longing to do precisely those things.

Embrace myself. My weaknesses. And yes, my strengths.

Embrace my limitations, not as a way of giving up, but in an act of radical acceptance that will allow me to find ways to thrive in spite of those limitations.

Embrace my wildly disorganized and messy writing process.

Embrace others. Even those I disagree with or struggle to understand.

Embrace new experiences and challenges, something I have shied away from for the last couple of years.

I find I am even open to embracing conflict, not because I have suddenly changed into a combative person, but because I am beginning to see just how big an opportunity for growth it truly is.

I want to embrace even the ugly stuff—professional envy or personal resentments—and use them as opportunities to transform the way I think or approach those people or situations.

I want to embrace those I love and let them know how much they mean to me. I want to embrace and foster the friendships and connections that have languished the last few years while radical self care had to be my top priority.

The cool thing is, by embracing that self care and honoring my physical and emotional needs (aided by a body that wouldn’t let me do anything else) I have come full circle, back to where I am eager to embrace all the things I once had to jettison. I cannot tell you how much joy just typing that sentence brings me.

Embrace. The word conjures up love and nurturing and acceptance. It’s a big word for a big gesture—far more encompassing than a hug. And of longer duration.

It is a way to say yes to life in a way I have missed greatly.

So that is the true north I am setting this year’s compass to. What about you guys? Do you have words you have chosen for 2018? Is there anything you hope to embrace in the coming year?

August 1, 2017

Some Updates

Taking a quick break from revising the fourth HFA book to bring you a few updates:

The first draft is finished!

It has a title! (And no, I can’t tell you yet quite yet.)

It will publish in Fall of 2018.

The 5th HFA book is scheduled to publish in Fall of 2019.

Secondly, now don’t faint, but I will be doing an event this fall! I’m so excited to be participating the Pasadena Teen Book Festival! It takes place on Saturday, Sept 16, 2017 from 11am – 4pm. I’m not exactly sure what time my panel will be, but I expect it will be at the earlier end of the range. I’ll update when I have the exact time.

Where: Pasadena Public Library, 285 East Walnut Street Pasadena, CA 91101

Cost: Free! No tickets are necessary.

And lastly, after an over two year hiatus I stopped by Writer Unboxed today to talk about The Perils of Perfection. While the post is geared towards writers, I think it might be helpful to anyone who battles with perfection.

I’d like to promise I’ll be better about checking in here, but the truth is that likely won’t be happening until I finish the revisions. But once I do, I have some fun things lined up!

Until then . . .

November 22, 2016

On Writing: Frog Marching the Muse

(From the Writer Unboxed archives.)

(From the Writer Unboxed archives.)

Here are eighteen tips I use to help me produce words when my creative muse packed up and left me, leaving no forwarding address. You can, in fact, get an entire book written this way, although it is not the most joyful of processes.

Some of the things on this list are about assembling the raw materials you will need to write the story. Others are about priming the writing pump to get the words flowing. Often, the suggestions will do both. But all of them are about building forward momentum and finding a way—any way—to get those damn words on the page.

I tend to think of them as the equivalent of hauling the bricks, bag of cement, mortar, etc. over to where I am going to build the wall, assembling all the things I will need. Sometimes, having them all there and ready provides motivational juice. Other times I still have to build brick by brick, but at least I don’t have to go hunting for all the parts.

And look! Just in time for NaNoWriMo!

1. Write in short bursts of 20-30 minutes or 500 words.

2. Take a short 10-15 minute walk. Bring a small notebook or recording device.

3. Even if you’re not an outliner see if you can at least find your story’s turning points. It is much easier to build drama and write across shorter distances and can seem more doable. Exploring either of the internal or external turning points can often produce scene ideas and help propel you forward.

External turning points are those moment when everything shifts for your character; surprises or twists are revealed; or the stakes suddenly become higher. (And if none of those happen, then brainstorm some immediately.)

Internal turning points—think about your character’s emotional arc, who she is at the beginning of the story and how she will be different at the end. Be sure there is enough there there, then look at the incremental steps she will need to take in order to achieve that emotional growth.

4. Assemble the story’s descriptive details and building blocks. Map out the world of your story so all the info you need will be there when you’re ready. Map of the word, the neighborhood, history of the players involved, floor plan of the castle, whatever. This is not procrastinating because at some point you will need to be grounded in the story logistics enough that you can block your scenes and character movements.

5. Journal your characters wounds and scars and early life traumas. Once your character is fleshed out more, you often get a better idea for the sorts of obstacles she will need to face in the story, which in turn creates dramatic events and scene ideas.

6. If your antagonist is not a POV character, consider writing a few short scenes from his POV anyway, just for your own benefit. Knowing what your antagonist is doing, thinking, planning often helps you understand what needs to happen next and what your protagonist will need to do.

7. Repeat the above for the love interest, especially if they are not a POV character. It gives you a better feel for the push/pull of the relationship dynamics.

8. Plot out the beats of the main romance/relationship. What characteristics/attributes/specific moments/personality details feed the attraction between the two characters. Writing them down will help you see what needs to be woven into the story and will often generate scene ideas.

9. Create character cards. This can be especially helpful for secondary characters and creates a wonderful shorthand to help you focus the way the character interacts with other people, which in turn can help provide scene momentum. Oftentimes just being reminded of character’s dominant traits and the way they move in the world can help get things started.

Take a 3 x 5 index card for each character with their name on the top: Baron Geffoy

List three characteristics for that person: jovial, opportunistic, nurses grudges.

Add a hidden core motivation for both his personality traits and actions: impotent

Next, list a handful of dominant physical features that will help you key into that character and can also act as tags to help anchor the reader:

pale read beard hides a weak chin,

blue eyes watery from too many evenings spent drinking wine,

barrel chested.

Lastly, come up with two or three mannerisms the person uses:

stroking his beard,

shifting eyes,

rocking back on his heels

10. Assemble a list of physical actions for the story in general, individual scenes, and for each character. These physical actions characters perform are a great way to pull action into the scene—action you can then tweak to create DRAMATIC action and subtext. For example, let’s say one of your characters whittles wood to keep his hands busy whenever he is sitting still. If he does that enough times, at some point he can fumble the wood or drop it or the knife can slip and you won’t even have to tell the reader that he was surprised or perturbed by what just happened. How he whittles–slowly, vigorously, carelessly–will add depth of emotion and subtext to the scene. And really, there are thousands of everyday actions that can be used to give the scene some extra layering.

11. Write whatever scene is most vivid in your mind, regardless of where it will come in the book. I know this is hard for a lot of people, but sometimes those vivid scenes will provide story juice or clues or touchstones that we can then use to work back from. Yes, it does involve some scene stitching later on, but if you are on a deadline and that’s all you’ve got to work with, you sometimes can’t afford not to try it.

12. Assemble a book specific thesaurus. We all have words we overuse, and each manuscript has it’s own special set of words we use too often. Mysterious, dangerous, dark, compelling, whatever words you see coming up thematically in your work. Take some time and a really good thesaurus and fill your word well with new choices that you haven’t used or thought of before. (Not overly fancy words or those that force people to use dictionaries—this is more of a way to break out of your word rut.)

13. Scene sketching – This is a great tool for brainstorming a scene and getting some bare bones down that you can then fill in with more detail. You can pick one of these per scene or throw the full monty at it, depending on how utterly blank your mind is.

a) gather the descriptive details you will need for the scene, location, weather, clothing

b) block out the physical action and logistics of the scene

c) list what has to happen here—what is the reason the scene exists.

D) write the dialog only—as if you are listening in on a conversation—what can you hear the characters saying to one another.

14. Write transitions. These are those chunks of writing that propel the reader from one scene to the next or across time and space where nothing happens. It’s a great way to jump through swaths of time and keep moving. You also might find in the end that you don’t actually need anything there. It’s a great way to avoid boring daily accounting of characters’ activities and keep the story moving forward.

15. Switch into a telling mode if you need to. This allows you to ‘tell’ the story. You can then go back in and convert it to showing/action based scenes later but being able to ‘tell’ helps you keep moving forward.

16. Give yourself 10-15 minutes to research visuals for your scene—the location, the room, the clothing, a picture of what your character either looks like or expressions that convey the emotion she is feeling. Sometimes it can be easier to describe what we can actually see.

17. Pick five or six dramatic events that you know occur in your story. Take those moments and really dig deep, delving into your characters deepest layer of thoughts and feelings. Sometimes the story stalls out not due to lack of action, but because we don’t truly understand what our characters would be experiencing in the moment and how that would impact their future decisions and actions.

18. Turn off the internet. No, really. Just turn it off.

And there you have it! All my quick and dirty tricks for getting words on the page.

November 20, 2016

On Writing: Spackle

A lot of us are feeling woefully behind on our word counts right now and doing anything we can to move forward. One of my the things I rely on in these sorts of situtations is the literary equivalent of spackle.

Spackle, you might ask? You mean like that weird, white plastery stuff that you use to cover holes in the wall?

Yes. That is exactly what I mean.

Spackle when writing is just what it sounds like: a flimsy lick and a promise to get back to a spot and create something better. Stronger. Heftier. When I am in the zone and the story is unfolding before me, if I take too long in trying to capture the words, they’ll disappear before I can get them down. For me, always, the race is to get the story down while I’m in the heated flush of that writing zone. I can linger and dally over language all I want later, once the bones of the story are firmly in place.

Or, conversely, if I am having a hard time getting the words to flow, or flow in a jumbled, out-of-order sort of way, I use spackle to fill in the blanks so I can at least maintain my forward momentum. Sadly, this is the situation I find myself in this month.

Spackle often shows up as a set of brackets [like this] when I know I need a better word or simile but I don’t want to stop the writerly flow and search right then.

Something in his face made me [uneasy].

His eyes hardened like [sharp flat stones].

Sometimes though, spackle can be an entire action.

[Heroine and hero escape stronghold and make their way to safety. Will need to learn something on the road that will be critical to final solution/climax.]

As you can see, that’s no mere phrase or word choice, but an entire plot point that needs to be worked out.

The thing is, with rough drafts I know I will need a series of scenes in there. Some of them are showing up, right on cue, and others aren’t. But I still need a placeholder in this new draft I’m building, something to help me capture the pacing and the rhythm of the scenes. In that case, I spackle entire scenes, which go something like this:

[They arrive at court. Hero leaves her to talk politics with duchess’s advisors. She pretends she’s bored and wanders away. Uses this as excuse to eavesdrop on other’s conversations. Learns Count Z has returned, sees Lord X and Lady Y in tete a tete, wonders what they’re up to. Protects one of the serving maids against an overbearing baron, accidentally runs into the French ambassador, then herofinds her and invites her to dance.]

In that bit I list all the things from the various plot threads I’m juggling that I know have to happen then, in that scene. It also helps me capture in really broad strokes what the scene will encompass, while also giving my subconscious time to figure out more of the details and the nuance and even what the scene will actually be about. (Because clearly, from looking at that list, I do not have a clue. Yet.)

Oftentimes, I’ll figure out major epiphanies for that scene in subsequent scenes—scenes I never would have written if I’d let myself get totally stuck and stymied in one spot and not allowed myself to use spackle.

So if you aren’t currently using spackle, you might see if there’s a place for it in your writer’s toolbox. Because honestly? Sometimes a lick and a promise and a healthy dollop of spackle is what finally gets us to the end of this first, rough draft.

October 31, 2016

On Writing: What’s In A Name?

For me, naming is a huge part of character. In fact, I cannot get very far in a novel until I have the correct name. I can be brainstorming and jotting down plot notes and some basic character sketching but until the true name clicks, I’m rudderless. The character doesn’t become real to me until that name solidifies.

The truth is, names matter. A lot. Both in real life and in fiction. So much goes into a name; parental hopes, ancestry, gender, ethnicity, and social status.

Because names carry all that weight, they can also be a hugely valuable tool in terms of world-building, setting an emotional tone, creating an integrated setting, and of course, characterization. The right name can also help anchor us in the story world, whether it be historical or contemporary or Other. Think how different the name Araminta is from Jennifer, or Carradoc is from Justin.

Plus all words have connotations, even names. The way they sound, feel, roll around in our mouths as we say them. All those elements affect how we perceive a name as well. As writers, we can use that, make it work for us. The names can do a significant amount of “showing” so we don’t have to waste time “telling.”

And then some letters are just funnier than others. I think u is the funniest of the vowels. Perhaps it’s something as juvenile as being reminiscent of certain forbidden words, or hearkens back to the ugh of the caveman. I don’t know, but it amuses me.

There are also certain consonants that are funny (b, f, d, g, k) and others that are stately (s, t, r, c) and others still whose sound brings a lot to the table, (b, g, s, l, z) Let those inherent qualities in letters work for you as you choose your names.

(Now you all know how slightly whacked I am about letters, but that can’t be helped.)

Of course, one of the most obvious things names do is convey shades of character. Clearly a person named Mandy gives off an entirely different feel than one named Cassandra.

Not only can you have a lot of fun with this, you can let the names do some of the heavy lifting in terms of setting the tone. I did this a lot in the Theodosia books. It was especially fun naming the three governesses who bedeviled Theo in Theodosia and the Staff of Osiris. They were short, walk on roles, so I didn’t have much space to dedicate to describing them, so I turned to their names to help set the tone of their personalities. One was unbearably repressive, another a tippling nervous wreck, and the last was a lovely looking woman, but with a vicious edge to her. The names I assigned them were Miss Chittle, Miss Sneath, and Miss Sharpe.

There is also a pompous lord named Lord Chudleigh, the chu being very reminiscent of chump.

For the Beastologist books, I wanted a family name with the venerable weight of generations and tradition behind it. But I didn’t want it to take itself too seriously, almost like an inside joke. My first choice was Dinwiddie. I’d seen that name on a billboard somewhere and fell in love with it. However, the Beastologist books are chapter books, so I needed a shorter name. I finally came up with Fludd. (Note how many of my favorite letters it has in there!) It’s short, not too common, and carries a slight sense of ridiculousness about it—especially when paired with the concept of veneration.

That’s actually something I do a lot—go far back in family history to understand where the names came from. For example, a mother who has an unusual name and hates it, will often give her daughter a more popular name. Someone who felt their name was too bland, will be inclined to give their child a more unique, individual name. Ethnic roots come into play here too, many people trying to tap into those as they name their children. Names in the 1950s were wildly different than the names we give our children now. But also the interests and focus of the family can effect names. A family of classical scholars might name their children Persephone and Augustus.

If you feel that approaching names this way feels too contrived, let me tell you that you couldn’t possibly make up the following names of REAL PEOPLE I’ve run into:

Mr. Swindle – a bank manager—no lie (and he’s very upright and responsible!)

Dr. Kwacko – a doctor (Now tell me name’s aren’t destiny!)

A name I used in the Theodosia books, Fagenbush came from a kid in one of my kid’s classes back in elementary school.

Of course, I ran into a completely different set of problems with the His Fair Assassin books. For one, many of the names were of real people, so I was stuck with those. And la! All those French pronunciations! Another tricky impediment to names in historical periods is that often, a given time period had about five first names they used for about 90% of the populace! In medieval France/Brittany it was Anne, Louise, Mary, Jean, and Marguerite. But thankfully, writing in the age of Google, it is fairly easy to access some of the more unusual names from medieval French and Breton town records, and therefore keep the character’s names unique, yet not anachronistic. However, I must admit that I made up the names Ismae and Annith. The name Sybella was an adaptation of Sibylla from THE KINGDOM OF HEAVEN.

Besides Google, a great place to find historically authentic names is in the index of research books on the time period. A quick scan often reveals a number of names that can at least be used as a jumping off point.

And, phew! That was a lot of information on names!

Save

Save

Save

Save

October 30, 2016

On Writing: Managing a Cast of Thousands

Someday, I will write a book that does NOT have a cast of thousands. Some day. But for now, that seems to dog me with every book I write. Here then, is a trick I devised to not only help me keep track of the characters, but to help the ones that need to be memorable BE memorable.

When one’s novel is populated by hundreds of people, not every one of them can stand out, nor should they. It would be exhausting and overwhelming. Even worse, it would risk diluting those characters who truly were important. It is perfectly acceptable to have some characters in one’s novel simply be part of the backdrop, the bodies that populate the room for realism’s sake while the true drama unfolds among a select handful of your characters. For those walk-ons and stand-ins, its okay, necessary even, to use quick broad strokes, perhaps even, dare I say it—stereotypes—since their actions have no bearing on the plot.

Because their actions have no bearing on the plot.

Those words are key.

It’s essentially a matter of selecting the right tool for the right job, and complex characterization isn’t always the right tool. In pursuing some abstract concept of “good writing,” it’s easy to get so wrapped up in wanting every character to be meaningful, that we lose sight of the simple fact that it isn’t necessary. Or even desirable. Brilliant characterization for every single human being in a novel would be exhausting and would not even serve the story.

So for the His Fair Assassin books, I’m constantly juggling a cast of thousands. I need a sense of a full royal court worth of nobles, but I also need for the reader not to get swamped or bogged down by all the players. I want them to feel real enough that they add texture and richness to the story, but at the same time, I can’t allow them to swamp it, either sheer numbers or from being too vivid. And any vividness needs to serve the story overall, not threaten to run away with it.

*I* also need to not get overwhelmed by all the players.

These are more than simply walk-ons, but not true secondary characters. And there are a couple of traitors hidden in there, so they need to be on-screen enough that the readers don’t feel cheated when their identities are revealed.

So as I was staring bemusedly at the mss page, trying to decide how to make all these people stand out—for both myself and my readers—I came up with this little system.

I took a 3 x 5 index card for each character and put their name on the top: Baron Geffoy

Then I picked three characteristics for that person: jovial, opportunistic, nurses grudges.

Then I added a hidden core to that person, that was the core motivation for both his personality traits and actions. For Geffoy it was: impotent

Next I listed a handful of dominant physical features that would help me key into that character, but that would also act as tags to help anchor the reader in that character: pale read beard hides a weak chin, blue eyes watery from too many evenings spent drinking wine, barrel chested.

Last, I listed two or three mannerisms that this person used: stroking his beard, shifting eyes, rocking back on his heels

I was surprised by how much this helped me get everyone straight in my mind, and helped delineate them on the page. Especially since, at face value, many of them had similar characteristics. For example, many of them were arrogant, as nobles often are. But I learned that one of them was arrogant and dismissive, while another was arrogant and calculating, which totally informed how they interacted with others and helped me nail their speech patterns.

It also helped be sure that all the information I divulged about these characters went to building a cohesive impression.

So anyway, I thought I’d pass that trick along in case anyone else was struggling with a similar problem.

To recap…

Name:

Three Characteristics:

Hidden Core:

Dominant features:

Mannerisms:

October 20, 2016

On Writing: Arcs

Okay, I’m going to get all math-ish on you here, but bear with me a moment. And I say this as a person who hated geometry. (I liked algebra because it mimics life–in life we are always trying to solve for the unknown–but that’s the subject of a different post…)

In geometry, an arc is the path between two points. It is exactly the same with a character arc. A character arc marks the path between your character at the beginning of the story and your character at the end of the story. The change in the character does not happen all at once, it happens gradually over time, a series of small steps before the final climax when the character is remade into his new and improved self.

Think of a baby chick or a butterfly. It pokes and wriggles, attempting to free itself from the egg or the cocoon, until the very end where it makes a heroic final burst and breaks free. And as any naturalist will tell you, it is hugely detrimental to help the creature break free too early because it is in the actual struggle itself that the chick or butterfly will gain the strength to make that final valiant effort that frees it from it’s old trappings. That pretty much sums up a character’s internal journey and arc.

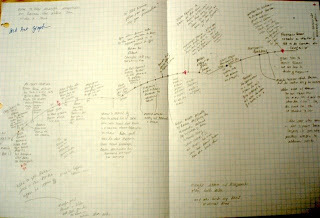

Here is a picture of one of my character arcs:

You can see the small, incremental steps, moving things forward and upward as well. Small points on the graph eventually build to a whole new place. But not only are their small, incremental steps, the larger arc is made up of smaller arcs, with dips and rises.

Sometime the small steps will be incredibly subtle, as subtle as a shift in perception by the character, a recognition that there is a problem, or that the best friend doesn’t have her best interests at heart, or the first time she ever, even tentatively, told someone no.

By plotting out your character’s growth toward change (either consciously or instinctively) you create a forward momentum in your story, a sense of true movement. Those small steps build on each other. As a writer, knowing and understanding those changes that have to occur help us to design or shape our scenes so they pack the most punch. They also allow us to make sure our story is BUILDING toward something, or recognize when it is not so we can fix it. (And yes, for those wondering, I do one of these for each act of my story.)

Save

October 14, 2016

On Writing: The Basics–Now Make It Worse

Let’s say you’ve spent some time and come up with this perfect conflict for your character. There is even something at stake if she fails. Go you!

Now think of a way to make it worse. Seriously.

I had an opportunity to attend one of Donald Maass’s all day workshops, and he asked this question. Many times. So often, we got to giggling, however, it was highly effective in driving home his point. Push the limits. Dare to take your character to the wall, then blow the wall away and take him even farther than that.

So, have you found a way to make it worse? Good.

Now make it matter even more. No, I’m not kidding. And there is a subtle different between making something worse, and making it matter more. Making something worse is about upping the stakes, making it matter more is about upping the emotional intensity of those stakes.

For example, when I was writing Theo, my initial external conflict was that she was going to discover this cursed artifact and removing the curse was going to fall on her shoulders. To make it worse, I decided that curse had the power to bring feast, famine, drought, and destruction to the entire country. To make it matter even more, to twist the conflict so that it uniquely and intensely skewered Theo, I had it be her mother who had unknowingly unleashed this horror on the world. For a child who felt responsible for her parents and whose familial role was to take care of them, this really upped the intensity of the conflict. Not only was it the worst that could happen (death and destruction on a national scale) but it would be her family’s fault, which gave her an added impetus to stop it.

So now take a look at your conflict.

How can you make it worse?

How can you make it matter even more?

Can you make it even worse than that? Oh go on, try. I bet you can.

Some things to consider:

Make your characters suffer. Whoever your hero cannot live without, cannot possibly succeed without, remove them. (Maass suggests killing him, but I write for kids so I take a gentler approach.)

What is your character’s greatest asset? Take it away.

What is sacred to your hero? Undermine it.

How much time does he have? Shorten it.

What matters most to your character? Threaten it.

You get the idea.

The thing is, Maass said that of all the manuscripts that cross his agency’s desks, few fail because they go too far or push too hard. No, the majority of them fail because they don’t go far enough, they don’t take things to their extremes. Which relates to my post of a couple of weeks ago about failing gloriously. Don’t let your failure be a whimpering one. If you aim for the bleachers, you have a better chance of getting past first base.

(Or something like that. I’m not so good with sports metaphors.)

October 13, 2016

On Writing: The Basics–Speaking of Conflict

Conflict drives the story. It’s pretty much that simple. If you don’t have conflict on some level, you don’t have a story. The good news is, conflict comes in many shapes and sizes, flavors and colors. The bad news is, most people tend to avoid conflict, so it can be difficult to grab it with both hands and force your characters into the thick of it.

Besides, we writers usually like our characters. We don’t want to put them through the wringer. But alas, if we want to effect a transformation in their lives, we must. Remember, we are the meddling, interfering Olympian gods in our book’s universe. It is our JOB to mess up our characters’ lives and force them to change or teach them a life lesson.

One of the first things I do after I’ve managed to come up with an internal and external GMC for my characters is I step back and try to decide if the nature of the conflict is actually big enough to sustain a book. The truth is, all of the manuscripts that languish under my bed are there because the initial idea simply wasn’t big enough or didn’t contain enough conflict to sustain an entire book. It is also one of the most frequent mistakes I see when editing or critiquing beginners’ work. Keep in mind that an average MG book is about 100-150 mss pages, and an adult book is around 300. There’s a fair amount of conflict needed to keep things clipping along toward the end. Without conflict, you have no dramatic push or narrative drive. Things just float along, attention wanders, and suddenly readers are putting your book down so they can go surf the net or watch a reality TV show.

So one of the first questions I ask myself is, If the protagonist doesn’t attain her goal, what is at stake? What does she stand to lose? And I usually need two answers to this, one that can be addressed by the physical actions of the story (if Theo doesn’t return the artifact to Egypt, her mother will have infected Britain with a curse so vile, it brings down the entire country) and a second one that addresses the emotional wounds or scars of my characters (If she saves the world, surely they’ll love her then. They’ll have to.)

The second question is, Why this character and this problem? This is where irony comes in, or Fate, or Kismet. Why has the universe graced this particular character with this particular problem? Why her?? Why is this the worse thing that could happen to her?

In fact, if you have a character in mind for a story and you’re not being able to get any sort of conflict to gel, ask yourself, what is the worst possible thing that could happen to her? That is conflict.

The thing is, random crappy stuff happens to people in real life all the time. Life is hard and then you die, as the saying goes. But the one thing we can do to prove that saying wrong is to choose to embrace our circumstance and learn from it. As writers, we simply have to plan that out ahead of time. Fiction can’t be random, it needs to mean something in order to resonate with readers.

Theo, a child who is emotionally abandoned and somewhat willfully ignored by her parents, gets by by being invisible and uber responsible. So if she suddenly starts blabbing about magic and curses, her parents are going to see her as being very fanciful, irresponsible, and constantly in the way and underfoot. They will stop taking her seriously, and she will lose what tenuous connection she has with them and will be completely dismissed by them. Considering the day and age she lived in, she might even be committed to a sanitorium. If her parents were more attuned to her, or more doting, she might have stood a chance in telling them the truth. But in light of their current dynamic, the truth didn’t stand a chance.

On the external plot level, the Why her? question is embedded in Theo herself, a young girl with few resources except an ability to detect ancient magic and evil curses. If she didn’t have that ability, she’d never have gotten wrapped up in all this business to begin with. For all intents and purposes her parents museum would have suffered a normal burglary and that would be the end of it. But since she does have that ability, she gets drawn into far more than the average bear.

So take a look at your conflict. First of all, do you have any? And if so, is it big enough? Is something truly at stake for your character if they fail? Lastly, why this character and this problem?

October 12, 2016

On Writing: The Basics–Plotting: Baby Steps

Okay, so let’s say you’ve figured out—kind of—what your characters motivations and desires. You even have a pretty good idea as to what is standing in their way—a bad guy, a raging storm, a stalking fae, a lovesick werewolf, whatever. Now how do you take what you know and shape it into a plot?

What I do at this point is I sit down and look at both the internal and external GMCs. Then I try to brainstorm four to six baby steps the character will need to take to achieve both the internal goal and the external goal. In real life, change may happen over night, but in fiction, we readers want to see the process of change, make that journey to a new, improved self along with the character, so it helps to be sure and break down the change into manageable bites.

Now is probably a good time for me to explain that I don’t do all of this at the very beginning. I usually spend some time writing what I do know, either snippets of scenes or dialogue, details about the world, setting, or characters. Sometimes, I’m pleasantly surprised by how very much I instinctively know about the story. Then I use these exercises to fill in the blanks.

Other times I’ll have a pretty clear idea of the external plot, but then need to be sure the action precipitates growth in the character. In that instance, I’ll look at the baby steps for my internal GMC, and make sure that the scenes I have for the external plot change the character’s internal landscape, using those baby steps as my guidelines.

Other times, I’ll have a solid idea of an internal journey, but no clue as to what has to happen physically in the story. In that case I’m pretty wide open for brainstorming the most effective (and dramatic) external events that will bring about those changes.

It’s also not a bad idea to write an entire discovery draft, learning about your characters and their internal landscape, friends and relationships, before applying any plotting or structure to the manuscript.

The point I’m trying to make here is that whatever you way you approach the story is the right way. It’s just a matter of finding a process that allows you to plug up the holes you don’t know yet.