Moniek Bloks's Blog, page 85

April 7, 2023

Gytha of Wessex – An Anglo-Saxon Princess goes East

Gytha of Wessex is probably one of the most unique wives of a Rus prince. Originally from England, she eventually became the wife of Vladimir II Monomakh. So what brought about this marriage of two people from opposite sides of Europe?

Early Life

Gytha was born around 1053, or perhaps a little bit later, to Harold Godwinson, Earl of East Anglia and Wessex and Edith Swanneck. Harold was one of the most powerful noblemen in England at the time. Harold and Edith were not married by the church but joined in a handfasting marriage. These marriages were common at the time, and any children born from them would be considered legitimate. Harold and Edith had six known children, sons Godwin, Edmund, Magnus, and Ulf and two daughters, Gytha and Gunhild.

On 5 January 1066, the English King, Edward the Confessor, died without heirs. The next day, Harold was crowned King of England. However, his right to the English throne was soon contested. In September 1066, William, Duke of Normandy, invaded England. On 14 October 1066, Harold was defeated and killed in battle. His death would change the course of Gytha and her siblings’ lives.

Exile

With their father dead and the Saxons conquered, Gytha and her brothers fled England. They spent some time in Flanders, where Gytha probably established close relations with the Church of St. Pantaleon in Cologne, which she supported throughout her life. Gytha and two of her brothers eventually went to Denmark. There they lived at the court of the Danish King, Sweyn II, who was also their cousin.

With their hopes to regain England unlikely, Sweyn planned other options for his exiled cousins. He had Gytha’s brother, Magnus, enter a high-ranking position in the service of Boleslaw II, Duke of Poland. He also wanted to plan an advantageous marriage for Gytha.

Marriage

After Gytha arrived in Denmark, Sweyn betrothed her to Vladimir Monomakh, one of the Rus princes. The exact reason for the betrothal is unknown, but it was probably made because Sweyn wanted to make an alliance with the Rus. The Rurikid dynasty that ruled there had Scandinavian origins and maintained connections with Scandinavia through marriage and trade. Also, Gytha’s paternal grandmother, who had the same name as her, was Danish.

Neither Vladimir nor his father, Vsevolod, were Grand Prince of Kyiv at the time, but they still held large amounts of land and had a prominent position in the Rus. The exact date of Gytha and Vladimir’s marriage is unknown, but it must have been between 1069 and 1075. At the time of the wedding, Vladimir’s father, Vsevolod, was Prince of Pereyaslavl and Chernigov. Vladimir became Prince of Smolensk in 1073. After Gytha married, she is believed to have settled in Suzdal with Vladimir. Both Gytha and Vladimir would have known Danish, which was probably the language they used to communicate. Gytha would have been raised in the Catholic faith, but Vladimir and his family followed the Orthodox faith. Because of this, Gytha converted to Orthodoxy when she married.

Gytha as a Rus Princess

Gytha and Vladimir were close in age. Not much is known about their marriage, but they seem to have got along. During the marriage, Vladimir would change principalities a couple of times. In 1078, he became Prince of Chernigov. In 1094, Chernigov went to his cousin, Oleg, and Vladimir became Prince of Pereyaslavl. His father became Grand Prince of Kyiv in 1078 and reigned there until his death in 1093. Afterwards, Vladimir’s cousin, Sviatopolk, became Grand Prince of Kyiv. Vladimir himself would not become Grand Prince until 1113. However, Gytha had died by then.

During their marriage, Gytha and Vladimir had between six and thirteen children:

Mstislav I (1076-1032) Prince of Novgorod and Grand Prince of Kyiv. Also known as Harold.

Izyaslav (c.1077-1096) Prince of Kursk.

Svyatoslav (c.1080-1114) Prince of Smolensk and Pereyaslavl.

Yaropolk II (1082-1139) Prince of Smolensk, Pereyaslavl and Grand Prince of Kyiv.

Viacheslav I (1083-1154) Prince of Smolensk, Pereyaslavl and Turov, Grand Prince of Kyiv.

Marina (d. 1146) Married to an imposter claiming to be the Byzantine Prince, Leo Diogenes.

Gleb, existence uncertain

There is debate if it was Gytha or a second wife of Vladimir who was the mother of these children:

Roman (d. 1119) Prince of Volhynia

Yuri (c. 1090/95-1157) Prince of Rostov and Suzdal, Grand Prince of Kyiv

Euphemia (c. 1096-1139) Married Coloman, King of Hungary

Agafia (d. bef. 1144) Married Vsevolod Davidovich, Prince of Gorodno

Evpraxia (d. 1109) Not mentioned in most sources

Andrew (1102-1141) Prince of Volhynia and Pereyaslavl

Gytha seems to have taken an active role in cultural life. She is believed to have brought some books from England. Perhaps she was trying to take these books to safety when she fled following the Norman Conquest. Her father-in-law spoke five languages, and Old English might have been one of them. If so, Gytha would have taught him English. Vsevolod might have wanted to learn this language so he could read the books Gytha brought.

Scholars have noticed some similarities between Anglo-Saxon texts and the texts from the time of Vladimir Monomakh, such as his teachings and The Russian Primary Chronicle. It is believed that these first Russian chronicles were inspired by the Anglo-Saxon ones. It has been suggested that perhaps Gytha took part in editing the chronicles herself.

Another cultural legacy of Gytha is the veneration of Saint Pantaleon in Rus. Saint Pantaleon was a Greek martyr from the third century who was praised for his healing powers. Gytha seems to have had ties with the church dedicated to him in Cologne; she may have spent some time there soon after she was exiled from England. For the rest of her life, she maintained close ties to this church and made generous donations to them. One of the frescoes in the Saint Sophia Cathedral in Kyiv contained an image of St. Pantaleon. It may have been Gytha herself who commissioned this image.

In the 1120s, Rupert, an abbot of a Cologne monastery, gave the monks at St. Pantaleon Cologne a sermon that mentioned Gytha and her oldest son. According to Rupert, Mstislav was attacked by a bear while hunting and seriously wounded. Gytha then prayed to St. Pantaleon that he would survive. The saint eventually appeared to Mstislav in a vision, telling him that he would be healed. Gytha was told about this vision, and when Mstislav recovered, she vowed to take a pilgrimage to the Holy Land in thanks for this miracle. The date of these events is not mentioned, but it is believed to have occurred around 1097. Mstislav and his son, Izyaslav, continued to venerate St. Pantaleon and maintained ties with the church in Cologne.

Later Years and Death

There is debate about when Gytha died. The two dates usually given are 1098 or 1107. For the earlier date, it is said that Gytha made a pilgrimage to the Holy Land and even joined the First Crusade, which was happening at that time. She is believed to have not survived the journey and died in the Holy Land in 1098. The date is believed to have been 7 or 10 March, based on records from St. Pantaleon, Cologne.

However, it is said that she was unlikely to have joined the First Crusade, and if she indeed did make a pilgrimage to Jerusalem, it was probably after the crusaders took the city in 1099. By then, it would have been safer for Christians to make the journey to Jerusalem.

The second date is 7 May 1107. This date comes from Vladimir’s writings, where he mentions that the mother of his son, Yuri, died on that day. It is sometimes thought that this referred to Vladimir’s second wife rather than Gytha. However, it is likely that Gytha was Yuri’s mother. Furthermore, Yuri was old enough to marry in 1107, so he must have been born before 1098.

Currently, it looks like the 1107 date is more accepted. The burial place of Gytha is not known. She did not live long enough to become Grand Princess of Kyiv, for Vladimir did not become Grand Prince until 1113 when his cousin, Sviatopolk II of Kyiv, died.

Interestingly, the blood of Harold Godwinson would eventually make its way back into the English royal family via Gytha. Her son Mstislav’s 5th great-granddaughter was Isabella of France, who married Edward II of England, and was the mother of Edward III, who was the ancestor of all subsequent English monarchs.

Sources

Connolly, Sharon Bennett; Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest

Evgenievna, Morozova Lyudmila; Great and Unknown Women of Ancient Russia

Lewis, Stephen; “Gytha of Wessex, an Anglo-Saxon Russian Princess”

McGrath, Carol; “Gytha, Princess of Kyiv” (video)

“Gytha of Wessex” on the website The Court of the Russian Princesses of the XI-XVI centuries

The Russian Primary Chronicle: Laurentian Text

The post Gytha of Wessex – An Anglo-Saxon Princess goes East appeared first on History of Royal Women.

April 6, 2023

Royal Jewels – Queen Adelaide’s Brooch

Queen Adelaide’s brooch was made as a clasp for a pearl necklace for Queen Adelaide (born of Saxe-Meiningen) on the orders of her husband, King William IV.

The stones were taken from a jewelled badge of the Order of the Bath that used to belong to King George III. The order was completed in 1831, and the intended necklace was probably worn by Queen Adelaide for the coronation on 8 September 1831.

Embed from Getty ImagesAfter Queen Adelaide’s death, the necklace was next seen in Queen Victoria’s inventory. Queen Alexandra (born of Denmark) wore it as a brooch on her waist. Queen Mary (born of Teck) and Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother also wore it as brooches. Queen Mary sometimes attached a pear-shaped pendant.1 Queen Elizabeth II notably wore the brooch for the 2001 National Service of Remembrance for Britons killed in the 9/11 attacks.

Embed from Getty Images

The post Royal Jewels – Queen Adelaide’s Brooch appeared first on History of Royal Women.

April 4, 2023

What if Queen Victoria hadn’t been born?

The death of Princess Charlotte of Wales, the only child and heir of the future King George IV, left the succession wide open again.

King George IV’s next brother was Prince Frederick, Duke of York and Albany was married to Princess Frederica Charlotte of Prussia, but the couple had remained childless and were living apart.

The next brother was the future King William IV, who had made a life with his mistress Dorothea Bland, perhaps better known as Dorothea Jordan. William and Dorothea had ten children together, who were not in the line of succession due to their illegitimacy. When Princess Charlotte died, William went to find a suitable wife in the form of Princess Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen. Adelaide gave birth to five children, though three of those were stillborn. The other two lived only briefly, for a few hours and a few months. Thus, King William IV also did not leave any successors.

The next brother was Prince Edward, Duke of Kent, who had also made a life with a mistress – Madame de Saint-Laurent. He, too, sought a suitable wife after Princess Charlotte’s death and found the widowed Princess Victoria of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld. She had two surviving children from her first marriage to Emich Karl, Prince of Leiningen, and soon gave birth to the future Queen Victoria in 1819. Queen Victoria would succeed her uncle King William IV in 1837. But what would have happened if Queen Victoria hadn’t been born?

The next brother after Prince Edward was Prince Ernest Augustus, Duke of Cumberland and Teviotdale. He had married his first cousin, Duchess Frederica of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, in 1815. She had been married twice before. Following two stillborn children, Frederica gave birth to a son named George just three days after the future Queen Victoria had been born. But in this tale, Victoria wasn’t born, so George would have been the future heir, following his father. If George had been the next heir, it would also have meant that the personal union between the Kingdom of Hanover and the United Kingdom would have remained intact. Unfortunately, Victoria was not able to inherit Hanover as a woman, and this thus passed to Ernest Augustus, ending the personal union.

Assuming that male-preference primogeniture was followed as it was in reality but without Victoria, the thrones of Hanover and United Kingdom went to Ernest Augustus and then to his son George. George’s eldest son was also named Ernst Augustus. This Ernst Augustus was succeeded by his youngest (but eldest surviving) son, also named Ernst Augustus. Perhaps unsurprisingly, he, too, was succeeded by a son named Ernst Augustus. The current King would be his son – yet again named Ernst August (who in reality, is married to Princess Caroline of Monaco). He has two sons and a daughter, and the eldest is also named Ernst August.

Embed from Getty ImagesIn reality, absolute primogeniture went into effect in the United Kingdom in 2015 for those in the line of succession born after 28 October 2011. If we assume the same happened in our alternative reality, the line of succession would be Prince Ernst August (eldest son of the “king”), his eldest child Princess Elisabeth (born 2018), his second child Prince Welf August and his third child Princess Eleonora. Quite interesting to see that it would once again lead to a Queen Elisabeth (Elizabeth).

The post What if Queen Victoria hadn’t been born? appeared first on History of Royal Women.

April 2, 2023

Book Review: Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II: Platinum Jubilee Celebration: 70 Years: 1952-2022 by Brian Hoey

With The Queen celebrating 70 years on the throne last year, a number of books about her were released as well. Pitkin, known for its souvenir books, could hardly stay behind.

The book is just under 100 pages and is thus quite compact. To fit the life of The Queen in so few pages is quite an accomplishment. It’s quite an easy read and covers many important events in The Queen’s life. However, it also contains a few awkward mistakes. For example, Queen Elizabeth I is described as the ancestor of both Queen Victoria and Queen Elizabeth II, despite the fact that Queen Elizabeth I rather famously (supposedly?) remained a virgin. The Countess of Wessex also receives a new title – that of Duchess, and apparently, Prince William will become Prince of Wales when his father accedes the throne. While the latter is ultimately true, it doesn’t happen automatically or immediately.

Some of the text seems a little outdated, with the repeated use of “Her Majesty” and the use of “females” when describing women working in Buckingham Palace’s telephone exchange.

Overall, it’s a nice little souvenir book to own, but if you’re looking for something more substantial, this isn’t the book for you.

Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II: Platinum Jubilee Celebration: 70 Years: 1952-2022 by Brian Hoey is available now in the UK and the US.

The post Book Review: Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II: Platinum Jubilee Celebration: 70 Years: 1952-2022 by Brian Hoey appeared first on History of Royal Women.

March 31, 2023

Brunswick Cathedral – The final resting place of an exiled Queen

Brunswick Cathedral was established by Henry the Lion, Duke of Saxony and Bavaria, as a collegiate church between 1173 and 1195. He and his wife, Matilda of England, were both buried in the church while it was still unfinished.

Their tomb was made between 1230 and 1240, and the church was eventually consecrated in 1226. The Cathedral is now the final resting place of many more royal women, such as Caroline of Brunswick, the estranged wife of King George IV of the United Kingdom. The crypt underneath the cathedral can be visited, though I was quite lucky to be allowed through the gates for a closer look.

Tomb of Princess Christine Louise of Oettingen-Oettingen and her husband Louis Rudolph I, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg

Click to view slideshow.Epitaph of Henry the Lion, Duke of Saxony and his wife Mathilda of England

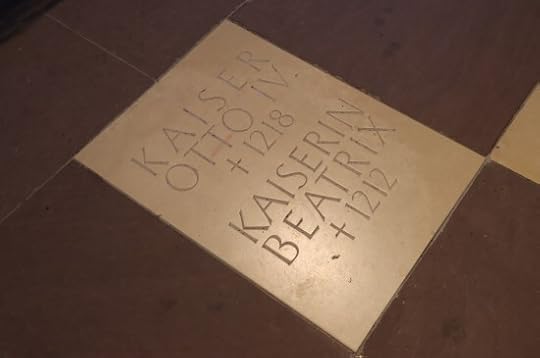

Click to view slideshow.Marker for Beatrix of Swabia and her husband Otto IV, Holy Roman Emperor

Photo by Moniek Bloks

Photo by Moniek BloksEntrance to the crypt

Photo by Moniek Bloks

Photo by Moniek BloksThe first two tombs belong to Ferdinand Albert I, Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel-Bevern and his wife, Christine of Hesse-Eschwege.

Photo by Moniek Bloks

Photo by Moniek BloksTombs of Ferdinand Albert II, Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel and his wife, Antoinette Amalie of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel

Photo by Moniek Bloks

Photo by Moniek BloksTombs of Ferdinand Albert I, Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel-Bevern and his wife, Christine of Hesse-Eschwege

Photo by Moniek Bloks

Photo by Moniek BloksTomb of Ferdinand Christian of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel-Bevern

Photo by Moniek Bloks

Photo by Moniek BloksTomb of Frederick George of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel-Bevern

Photo by Moniek Bloks

Photo by Moniek BloksTomb of Henry Ferdinand of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel-Bevern

Photo by Moniek Bloks

Photo by Moniek BloksTomb of August Ferdinand of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel-Bevern

Photo by Moniek Bloks

Photo by Moniek BloksTombs of William, Duke of Brunswick and his aunt Caroline of Brunswick, Queen of the United Kingdom

Photo by Moniek Bloks

Photo by Moniek BloksCaroline of Brunswick was unhappily married to the future King George IV of the United Kingdom and was the mother of Princess Charlotte of Wales. After being famously turned away from her husband’s coronation, Caroline died a mere three weeks later, and her body was returned to Brunswick.

Tomb of Albert of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel

Photo by Moniek Bloks

Photo by Moniek BloksTombs of Ferdinand of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, Frederick William, Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel and Charles William Ferdinand, Duke of Brunswick

Photo by Moniek Bloks

Photo by Moniek BloksTombs of Eleonore Charlotte Kettler (daughter of Frederick Casimir Kettler, Duke of Courland and Semigallia) and her husband Ernest Ferdinand, Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel-Bevern

Photo by Moniek Bloks

Photo by Moniek BloksShared tomb of Gertrude of Brunswick the elder, Margravine of Meissen (d.1077), her grandson Egbert II, Margrave of Meissen and his sister Gertrude of Brunswick the younger, Margravine of Meissen (d.1117)

Photo by Moniek Bloks

Photo by Moniek BloksTombs of Henry the Lion, Duke of Saxony and his wife Mathilda of England

Photo by Moniek Bloks

Photo by Moniek BloksTombs of Leopold of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, Charles I, Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, Ferdinand Albert II, Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel and Antoinette Amalie of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel. The heart urn contains the heart of Philippine Charlotte of Prussia, wife of Charles I.

Photo by Moniek Bloks

Photo by Moniek BloksTomb of one-year-old Frederick William of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, son of Ferdinand Albert II, Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel and Antoinette Amalie of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel

Photo by Moniek Bloks

Photo by Moniek BloksTombs of brothers Ludwig Ernest of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel and Frederick Francis of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel

Photo by Moniek Bloks

Photo by Moniek BloksThe so-called Welfentumba

This contains the bones of those buried in the nave before 1707. Anthony Ulrich, Duke of Brunswick, had his ancestors exhumed and buried together in this tomb. In this tomb is, among others, Beatrice of Swabia. Her original tomb is commemorated with a plaque, as you have seen above.

Photo by Moniek Bloks

Photo by Moniek BloksThe post Brunswick Cathedral – The final resting place of an exiled Queen appeared first on History of Royal Women.

March 30, 2023

Royal Jewels – Queen Adelaide’s Fringe Necklace

Queen Adelaide’s Fringe necklace has “sixty brilliant-set graduated bars, the central bars terminating in cushion-cut and pear-shaped stones, divided by 60 graduated brilliant-set spikes; an extra six small graduated bars and five spikes detached; tiara fittings removed.”1

It was created on the orders of King William IV, using diamonds removed from various items belonging to George III and Queen Charlotte.

Upon the death of King William IV, Queen Victoria inherited the Queen Adelaide fringe necklace, as it was considered Crown property. Queen Adelaide did not die until 1849. Queen Victoria liked the necklace as a tiara and wore it early in her reign during a visit to the theatre and at the opening of the Great Exhibition. After her husband died, she may have worn it as a border to the neckline of her dress.2

Embed from Getty ImagesQueen Alexandra wore it as a girdle around her waist for her 1902 coronation. Queen Mary had it reset as a tiara on a new frame and wore it a bit more horizontally than Queen Victoria had done. After that, it passed to Queen Elizabeth (later the Queen Mother), and she had it turned into a necklace once more. It then passed to Queen Elizabeth II in 2002.

The post Royal Jewels – Queen Adelaide’s Fringe Necklace appeared first on History of Royal Women.

March 28, 2023

The Year of Marie Antoinette – The tragic fate of King Louis XVII (Part three)

Just a few days after his mother’s death, Louis Charles was bullied into admitting that his aunt Elisabeth was the one “who carried out the plots best.” This information was duly brought to the council by Antoine Simon. 1 Eventually, it was argued that Elisabeth should also be tried by the Revolutionary Tribunal, but this did not happen immediately. Instead, in January 1794, Antoine Simon was relieved from his post as “tutor” to Louis Charles. He now fell into the power of Pierre Gaspard Chaumette and Jacques Hébert, and his re-education stopped altogether.

Chaumette and Hébert’s main objective was to keep the boy incarcerated. Following Antoine Simon’s departure, Louis Charles was moved into solitary confinement in one of the rooms on the second floor of the great tower. This was probably the dining room where he had last seen his father. The door was double-locked and strengthened with iron bars. The room had basically no natural light, and the window was almost entirely boarded up. The only other light came from a lantern, which was not allowed at night. He also had no books or toys. No one was allowed to enter the cell, not even to give him clean clothes. He was given two bowls of soup daily with a chunk of bread and maybe some boiled meat. He only saw the hands of those delivering the meals. In the evening, one of the commissioners shouted into the cell for him to get up and show himself.

Marie-Thérèse heard of her brother’s treatment and was outraged. “They had the cruelty to leave my brother alone; unheard of barbarity which has surely no other example! That of abandoning a poor child, only eight years old, already ill, and keeping him locked and bolted in, with no succour but a bill, which he did not ring, so afraid was he of the persons it would; he preferred to want for all, rather than ask anything of his persecutors.”2 No provisions were made for sanitation, which quickly turned the room into an unhygienic mess. As time passed, Louis Charles became too withdrawn to care for himself or the room. Fleas came into his bed and caused sores all over his body. He spent hours curled up on the infested bed. His room became infested with rats and mics, and he sometimes left his meals out so the vermin would leave him alone.

On 9 May 1794, in the room above, Princess Elisabeth was taken from the Temple to the Conciergerie. She turned to Marie-Thérèse and told her “to have courage, to practise the good principles of religion given [her] by [her] parents, and to hope in God.”3 Marie-Thérèse was now totally alone as well, and she was devastated. Elisabeth was executed the following day. Marie-Thérèse was not told of the execution, and she remained oblivious to her mother’s death as well.

It was not until Paul Barras’s visit in July 1794 that Louis Charles’s room was finally cleaned, and he ordered a doctor for Louis Charles, though it is not certain if one actually came. However, within weeks, the room was back to the same filthy state as it had been before. A man named Jean-Jacques Laurent was appointed as his guardian. Marie-Thérèse was struck by his polite manner and was much relieved to see him appointed as her brother’s guardian. Laurent was horrified by Louis Charles’s condition. He was “an emaciated boy in great pain, his head and neck fretted with sores, his shoulders stooped, his limbs unusually long and thin, and blue and yellow tumours on his wrists and knees.”4 Nevertheless, it took until the end of August before something was finally done. Laurent himself bathed the boy carefully.

Laurent was still only allowed to enter the cell during mealtimes, so Louis Charles was still largely in solitary confinement, and he remained highly suspicious of his improved treatment. He also became almost entirely silent. By the end of the year, he was allowed to move around the prison, and he once left flowers in front of his mother’s former rooms. However, he was not allowed any contact with his sister. In May, Laurent was replaced by Étienne Lasne.

In May 1795, a doctor visited Louis Charles, and he recorded the shocking sight. He had “encountered a child who is mad, dying, a victim of the most abject misery and of the greatest abandonment, a being who has been brutalised by the cruellest of treatments and whom it is impossible for me to bring back to life… What a crime!”5 He continued to visit Louis Charles until his own death on 1 June. Louis Charles, terminally ill and distressed at the doctor’s death, was without medical care for almost another week. On 6 June, he was visited by surgeon-in-chief Philippe-Jean Pelletan, who tried to treat him as best he could. Louis Charles was taken to the keeper’s lodge, which overlooked the garden, for fresh air. Pelletan later reported, “Unfortunately, all assistance was too late… no hope was to be entertained.”6

In the evening of 7 June, Louis Charles’s condition suddenly deteriorated, and Pelletan found him very weak the following day. He wrote, “We found Capet’s son with a weak pulse and an abdomen distended and painful. During the night and again in the morning, he had several green and bilious evacuations. His condition appearing to us to be very serious, we have decided to see the child again this evening… It is essential to have an intelligent female nurse by his side.”7 That evening, he found Louis Charles in tears, desperately wanting to see his mother. In the afternoon of 8 June, Louis Charles slipped into unconsciousness. He began to have difficulty breathing, and Lasne tried to lift him up to help with his breathing. In the arms of Lasne, he breathed his last breath and went limp. King Louis XVII was no more – he was just ten years old.

Photo by Moniek Bloks

Photo by Moniek BloksHis heart was removed during the autopsy, and he was buried in the Sainte Marguerite cemetery. His remains were not recovered after the revolution. The urn with his heart now rests near the tomb of his parents.

The post The Year of Marie Antoinette – The tragic fate of King Louis XVII (Part three) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

March 27, 2023

The Year of Marie Antoinette – The tragic fate of King Louis XVII (Part two)

They had arrived at the Temple with virtually nothing, but over the next few weeks, they were able to buy items to decorate their rooms. By then, they had been stripped of their attendants, including the Princess of Lamballe and the Marquise de Tourzel. Louis Charles couldn’t be alone, so he would now sleep in his mother’s room. The family now began to hope for rescue, which seemed like the only way out. Unfortunately, on 2 September, they were disturbed during their daily walk, and that night an angry mob stormed the Temple. When the King asked what was happening, the guard responded, “Well, if you want to know, it is the head of Madame de Lamballe they want to show you, for you to see how the people avenge themselves on tyrants.”1 The Princess of Lamballe had been hastily brought before a tribunal, and she was lynched by the mob. Both Louis Charles and Marie-Thérèse were sobbing at the horror of it all.

Following the horrors, the family tried to keep a routine in the Temple. Louis Charles received lessons from his father, while Marie-Thérèse received lessons from her mother. They were permitted to talk walks in the compound and exercised there as well. Nevertheless, Louis Charles suffered from nightmares and was often visibly distressed and nervous. Finally, in September 1792, the monarchy was abolished, and France was proclaimed a republic. In October, the family was moved to the other tower. The King and the Dauphin were on the second floor, while Marie Antoinette, Marie-Thérèse and Elisabeth were on the third floor.

On 11 December, Louis Charles was taken from his father to his mother, and he certainly sensed that something was wrong. The King’s trial had begun, and he was told he could see his children, but only if they did not see their mother or aunt as long as the trial lasted. Thus, he refused. The trial continued throughout December and early January. The vote for his execution ended with 361 in favour – a majority of just one. Due to this close majority, another motion for a reprieve was made, which was rejected with a majority of 70. 20 January 1793, he was informed that he would be executed within 24 hours. Later that day, he was finally reunited with his family. He told Louis Charles directly to pardon those who were putting him to death. He also told him and Marie-Thérèse to always be close friends and support each other and to be obedient to their mother.2 He gave them their blessing but refused to spend the night with them. He promised to see them in the morning, but their sobs still echoed as they left him. He was executed the following day without seeing his family again to spare them the agony.

“Shouts of joy” reached the ears of Marie Antoinette and Madame Élisabeth, the latter of whom exclaimed, “The monsters! They are satisfied now!”3 Marie Antoinette was unable to speak, but she, Elisabeth and Marie-Thérèse curtsied deeply for the new – titular – King – the seven-year-old King Louis XVII. Marie Antoinette devoted her life to Louis Charles and took over the lessons. The stifling conditions were bad for Louis Charles’s health, and he began to suffer from headaches, convulsions and a worm infestation. His mother and sister dutifully nursed him through the worst.

On 3 July 1793, Louis Charles was forcibly separated from his family. He “flung himself into my mother’s arms, imploring not to be taken from her.”4 Marie Antoinette refused to give him up, telling the guards they would have to kill her first. After being threatened that all would be killed, Marie Antoinette dressed him and handed him over. Louis Charles “kissed us all very tenderly and went away with the guards, crying his heart out.”5 He was taken to a room on the floor below, the late King’s room. He cried for the next two days, which his mother and sister could hear in the room above. It was decided that Louis Charles should be re-educated into a good citizen, and a man named Antoine Simon was chosen for the task. He treated Louis Charles well initially.

In August 1793, Marie Antoinette was taken to the Conciergerie for her trial, and she was separated from Marie-Thérèse and Elisabeth. As she left, she commended the care of her children to Elisabeth. She would never see them again and was executed on 16 October 1793.

(public domain)

(public domain)Meanwhile, Louis Charles was made to sing revolutionary songs at the window so his sister and aunt could hear them. Marie-Thérèse wrote, “Simon made him eat horribly and forced him to drink much wine, which he detested. All this gave him a fever… and his health became totally out of order.”6 He was made to wear the revolutionary uniform, and Antoine’s wife cut off his hair. He was taught to use foul language and was forced to refer to his aunt and sister as “common whores.”7 As Antoine became bored with his royal charge, he became more violent. Louis Charles, manipulated by the abuse, eventually testified against his mother. During this time, he briefly saw his sister, who rushed to embrace him. Marie-Thérèse was questioned about the alleged sexual relationship between her mother and brother. She was horrified at the allegations, and this would be the last time she saw her brother. Louis Charles remained unaware of his mother’s execution.

Part three coming soon.

The post The Year of Marie Antoinette – The tragic fate of King Louis XVII (Part two) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

March 26, 2023

The Year of Marie Antoinette – The tragic fate of King Louis XVII (Part one)

In 1784, Marie Antoinette was once again pregnant. She had given birth to a daughter – Marie-Thérèse – in 1778 and a son – Louis Joseph – in 1781. She had also suffered a miscarriage in late 1783. Louis Joseph was proving to be a sickly child, and a second son would be beneficial for the succession.

For some time, there were rumours about an affair between Count Axel von Fersen, and he had just returned to court after a three-year absence in June 1783. Although it is likely that Marie Antoinette and Axel had sexual intercourse, at the time, there was very little evidence for this. Could he be the biological father of this child? Possibly, though, we’ll never know for sure. Marie Antoinette’s husband certainly never doubted that he was the child’s father.

On Easter Sunday, 27 March 1785, Marie Antoinette gave birth to a healthy baby boy. Just 30 minutes after birth, the boy was baptised as Louis Charles, and he was created Duke of Normandy. His elder brother Louis Charles was still the Dauphin. Marie Antoinette’s sister Maria Carolina, Queen of Naples, was to be his godmother and the name Charles paid tribute to her. The infant was given into the hands of Yolande de Polastron, Duchess of Polignac, who was the Governess to the Children of France and a great favourite of Marie Antoinette.

The young boy was immediately showered in luxury. He had a wet nurse, a cradle rocker, a personal rocker, valets, two room boys, four ushers, a porter, a silver cleaner, a laundress, a hairdresser, two first chamber women, eight ordinary women and other minor staff. 1 He turned out to be the picture of health, and Marie Antoinette wrote that he was “a real peasant boy, big, rosy and plump.”2 His elder brother, who was prone to infections, was moved to his own suite on the ground floor of Versailles. His elder sister was eventually moved out of the nursery into her own apartment near their mother. Louis Charles was taken on carriage trips around the park, and he visited the farm at the Trianon. On 9 July 1786, Marie Antoinette gave birth to her fourth child, a daughter named Sophie. Tragically, the little girl lived for just 11 months.

Louis Charles remained in the care of the Duchess of Polignac until July 1789, when she was asked to leave by his father at the outbreak of the revolution. By then, he had been Dauphin of France for a month as his elder brother had died in June. The following October, Louis Charles was with his family when they were forced to move from Versailles to the Tuileries Palace in Paris. As their carriage led them to house arrest, young Louis Charles shouted out of the window, “Spare my mother, spare my mother!”3 For the next three years, they were to live under surveillance at the Tuileries.

Marie Antoinette asked the Marquise de Tourzel, who had replaced the Duchess of Polignac, to watch over Louis Charles at night. The young boy was terrified by the noises from the crowds outside. The palace was surrounded by the National Guard, who answered to the Assembly. Their every move was monitored, and Marie Antoinette told him to treat everyone politely. He soon made friends with the sons of the Guards and had a pretend “Royal Dauphin Regiment”, of which he was the colonel. He kept his own pet rabbits and tended to a small garden. The family spent a lot of time together.

On 21 June 1791, the family tried to escape from the Tuileries Palace, which is now known as the Flight to Varennes. Louis Charles was annoyed that he was being dressed as a girl, and he hid under the Marquise de Tourzel’s gown in the carriage. Initially, the escape went well, and they managed to get to Varennes, just 30 miles from the border. Unfortunately, there were no fresh horses waiting for them, and eventually, they were surrounded by the pursuing soldiers. They were detained in the mayor’s house, and the Assembly demanded their return to Paris. It took four days for them to return to Paris, and Louis Charles became very ill. Once back in Paris, the King was provisionally suspended from his royal duties, and any support he had left was quickly dwindling. Finally, in September 1791, he reluctantly signed the new constitution, and the King was now a mere figurehead.

The Tuileries 20 June 1792 (public domain)

The Tuileries 20 June 1792 (public domain)The following year, an angry mob stormed the Tuileries, demanding Marie Antoinette’s head. The King’s sister, Madame Elisabeth, had stood next to her brother and was mistaken for her. She told the other, “Don’t disillusion them. If they take me for the Queen, there may be time to save her.”4 Meanwhile, Marie Antoinette, Louis Charles and Marie-Thérèse fled from the Dauphin’s room and took refuge in the Council Chamber, where they were protected by just a few guards. For hours, they endured the taunts of the crowd. The mayor of Paris finally managed to disperse the crowds.

On 10 August 1792, a revolutionary government was established, and soon 20,000 armed citizens were on the streets of Paris. After a terrifying night, the family fled to the Legislative Assembly, where they feared for their lives. Louis Charles clung to his mother as the Legislative Assembly deliberated over what to do with the family. They were eventually taken to a former medieval fortress, known as the Temple. They were settled into sparse rooms with folding beds. Louis Charles had one room with the Marquise de Tourzel, and Marie Antoinette slept in the next room with Marie-Thérèse. The Princess of Lamballe slept in the antechamber while the King and his valet were in a room on the third floor. Finally, Madame Elisabeth and several waiting women slept in the kitchen.

Before the exhausted Marie Antoinette finally went to bed, she checked on Louis Charles as he slept.

Part two coming soon.

The post The Year of Marie Antoinette – The tragic fate of King Louis XVII (Part one) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

March 23, 2023

Royal Jewels – The King Khalid Necklace

The King Khalid necklace consists of “brilliants, marquises and 20 graduated pear-shaped pendants in openwork claw settings.”1

The necklace was made by the jeweller Harry Winston and was given to Queen Elizabeth II by King Khalid of Saudi Arabia. This happened during an official visit to Saudi Arabia in 1979.

Embed from Getty ImagesEmbed from Getty ImagesQueen Elizabeth II wore the necklace frequently and also loaned it to the Princess of Wales during the 1980s.

Embed from Getty ImagesThe post Royal Jewels – The King Khalid Necklace appeared first on History of Royal Women.