Moniek Bloks's Blog, page 83

April 28, 2023

New portrait of Queen Camilla released

A new portrait has been released of Queen Camilla ahead of the coronation next week.

Photo by Hugo Burnand/Buckingham Palace

Photo by Hugo Burnand/Buckingham PalaceThe photo was taken by Hugo Burnand in the Blue Drawing Room at Buckingham Palace last month. Queen Camilla can be seen wearing a blue wool crepe coat dress by Fiona Clare. She is wearing pearl drop earrings set with sapphire and ruby that used to belong to Queen Elizabeth II. Her pearl necklace is from her private collection. She is sitting in a giltwood and silk upholstered bergeres underneath a portrait of King George V.

The post New portrait of Queen Camilla released appeared first on History of Royal Women.

April 27, 2023

Royal Jewels – The Coronation Earrings

The coronation earrings were created for Queen Victoria to replace the earrings that she had been required to hand over to her uncle, the King of Hanover.

Embed from Getty ImagesThe drops, which were approximately 12 and 7 carats, were originally part of the Koh-i-nûr armlet. In 1858, they were taken from the Timur Ruby necklace in which they had been placed in 1853. The other stones for the new earrings were taken from an aigrette and a garter star. The jeweller Garrad’s charged £23 10s. After being made, the earrings were designated as an heirloom to the Crown by Queen Victoria.

Embed from Getty ImagesThey were worn by Queen Mary in 1911, Queen Elizabeth in 1937 and Queen Elizabeth II in 1953.1

The post Royal Jewels – The Coronation Earrings appeared first on History of Royal Women.

April 26, 2023

The Coronation of Anne Boleyn

King Henry VIII of England had moved heaven and earth to be able to marry his second wife, Anne Boleyn. When he finally did, it was a rather private wedding. When Anne turned out to be pregnant, he arranged for a magnificent coronation for her. It was important to him that his son was born to a mother who was consecrated as Queen.1

Anne travelled to the Tower of London on the first day of the coronation festivities on a barge that had once belonged to her predecessor, Catherine of Aragon. The festivities were planned to take place over five days. When Anne travelled to the Tower of London, it was 29 May 1533, and she landed at Tower wharf to the sounds of a gun salute. Henry came out to greet her “with a noble loving countenance.”2

They then retired to the royal apartments in the Tower so that Anne could rest. Anne spent the following day quietly at the Tower while Henry created 19 knights of Bath. Then, on 31 May, Anne set out for Westminster in a grand procession. She sat in a litter with a rich canopy held over her, and she was dressed in her finest clothes. Once more, she received a gun salute. Her route was planned out meticulously, and at Fenchurch Street, she stopped to watch a pageant given by children before travelling to Gracechurch, where she viewed another pageant on Apollo and the nine muses. After several more festivities, she finally arrived at York Place, where she would spend the night.

On 1 June, Anne was crowned at Westminster Abbey by Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Cranmer. He later wrote his own account of the occasion and wrote that Anne was “Apparelled in a robe of purple velvet, and all the ladies and gentlemen in robes and gowns of scarlet, according to the manner used before time in such business; and so her grace sustained of each side with two bishops; the bishop of London and the bishop of Winchester, came forth in the procession unto the church in Westminster, she in her hair, my lord of Suffolk bearing also before her a sceptre and a white rod, and so entered up unto the high altar, where divers ceremonies used about her, I did set the crown on her head, and then was sung Te Deum & c. And after that was sung a solemn mass: all which while her grace sat crowned upon a scaffold, which was made between the high altar and the choir in Westminster church; which mass and ceremonies done and finished, all the assembly of noblemen brought her into Westminster Hall again, where was kept a solemn feast all that day.”3

Claire Foy as Anne Boleyn in Wolf hall (Screenshot/Fair Use)

Claire Foy as Anne Boleyn in Wolf hall (Screenshot/Fair Use)Anne had to lay prostrate at the beginning of the service, a difficult task for someone who was six months pregnant. When she arose, the Archbishop anointed her on her head and her breast and crowned her with the St. Edward’s Crown, which was usually reserved for the coronation of the monarch.4

The following day, Anne attended jousts in honour of her coronation and then also attended a second feast. Her triumph was complete; all she needed to do now was give birth to a son.

The post The Coronation of Anne Boleyn appeared first on History of Royal Women.

April 25, 2023

Royal Wedding Recollections – The Duke of York & Lady Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon

The engagement between Prince Albert, Duke of York, second son of King George V and Queen Mary, and Lady Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon was announced in January 1923.

The statement read, “It is with the greatest pleasure that the King and Queen announce the betrothal of their beloved son, the Duke of York, to Lady Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon, the daughter of the Earl and Countess of Strathmore and Kinghorne, to which union the King has gladly given his consent.”1

The wedding took place on 26 April 1923 at Westminster Abbey, and crowds had gathered along the route. Elizabeth got ready at Bruton street and left from there with her father in a state landau. Around 1780 guests were seated in Westminster Abbey, which was described as “a large and brilliant congregation which included many of the leading personages of the nation and the Empire.”2

Embed from Getty ImagesEmbed from Getty ImagesThe service began with a procession into the Abbey led by the Archbishop of Canterbury. King George V was splendid in the uniform of an Admiral of the Fleet, while Queen Mary wore a dress and turban of aquamarine blue. Also present were Queen Alexandra and her sister Empress (dowager) Marie Feodorovna, and several other members of the family. Elizabeth’s family were also present, with her mother wearing a gown of “black marocain.”3

The groom was dressed in the dress uniform of the Royal Air Force, adorned with the Garter Riband and Star, and the Star of the Order of the Thistle, in honour of his Scottish bride. His brothers, the Prince of Wales and Prince Henry, were dressed in the uniform of the 10th Hussars.

The bride was accompanied by eight bridesmaids, Lady Mary Cambridge, Lady May Cambridge, Lady Katherine Hamilton, Lady Mary Thynne, Betty Cator, Diamond Hardinge and Elizabeth Elphinstone and Cecilia Bowes-Lyon. They were all dressed in “ivory-coloured dresses of crêpe de chine with bands of Nottingham lace, covered with white chiffon.”4 They had all received a gift from the groom, a carved crystal brooch in the form of a white rose of York with a diamond centre with the letters E and A. In addition, they all carried bouquets of white roses and white heather.

Embed from Getty ImagesElizabeth herself wore “a dress of cream chiffon moiré with appliquéd bars of silver lamé, embroidered with gold thread and beads of paste and pearl.”5 The dress had a square neckline and short sleeves, with a straight-cut bodice. She wore a long train with lace edging and a point de Flandres lace veil, lent to her by Queen Mary. The veil was held into place by a wreath of myrtle leaves, white roses and white heather. Her shoes were ivory silk moiré embroidered with silver roses. She carried a bouquet of roses and lily of the valley.6

Elizabeth entered the Abbey with her father, but as they waited after a member of the procession fainted, she suddenly left her father’s side and placed her bouquet on the Tomb of the Unknown Warrior. As she walked up the aisle, a guest reflected, “There was Elizabeth with her father & looking extraordinarily nice & I couldn’t help feeling most extraordinarily proud of her as if she’d been my own sister. She did it amazingly well & even appeared to be enjoying it as she smiled up at Lord S when he bent down & asked her something.”7

Embed from Getty ImagesAfter the address by the Archbishop of Canterbury, the family went into the chapel of Edward the Confessor to sign the registers. As Mendelssohn’s wedding march played, the new Duchess of York reappeared from the chapel with her husband. Her mother later reflected that Elizabeth looked “lovely… so dignified and restful, just her own sweet little self as usual.”8 The Duke and Duchess then bowed and curtseyed to the King and Queen before walking back out of the Abbey.

Embed from Getty ImagesThey entered a scarlet and gold coach, which took them to Buckingham Palace, where she received a curtsey from her eight bridesmaids. At the palace, a wedding breakfast took place with 60 guests. The 80o-pound wedding cake was cut in the Blue Drawing Room. Elizabeth later changed into her going-away dress, and she purposely wore a small hat so that the crowd could see her.

Embed from Getty ImagesEmbed from Getty ImagesEmbed from Getty ImagesElizabeth later ended her diary entry of her wedding day with the words, “Very tired & happy. Bed 12.”9

Embed from Getty ImagesElizabeth and Albert would eventually become King and Queen upon her brother-in-law’s abdication. They went on to have two daughters, including the future Queen Elizabeth II. Their grandson Charles is the current King.

The post Royal Wedding Recollections – The Duke of York & Lady Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon appeared first on History of Royal Women.

April 23, 2023

Royal Wedding Recollections – Princess Alexandra of Kent & The Honourable Angus Ogilvy

The engagement between Princess Alexandra of Kent, daughter of Prince George, Duke of Kent and Princess Marina of Greece and Denmark, and The Honourable Angus Ogilvy, son of David Ogilvy, 12th Earl of Airlie and Lady Alexandra Coke, was announced on 19 November 1962.

They had reportedly met at a ball of Luton Hoo and had known each other for around eight years at the time of their engagement. Princess Alexandra received an engagement ring with a cabochon sapphire surrounded by diamonds. Exactly one month after the announcement, Queen Elizabeth II officially gave her consent to the union.1

The festivities began on 22 April when Queen Elizabeth II hosted a ball at Windsor Castle. She received a tiara from her future husband, who had incorporated a set of diamond and turquoise flowers that she had previously worn. She wore the tiara on the night of the ball. The tiara was later worn by her granddaughter, Flora Ogilvy, during her wedding to Timothy Vesterberg.

Embed from Getty ImagesOn 24 April 1963, the pair were married at Westminster Abbey. The service was conducted according to the Book of Common Prayer by The Very Rev. Eric Abbott, Dean of Westminster, and The Most Rev. and Rt Hon. Michael Ramsey, Archbishop of Canterbury. Princess Alexandra wore a gown of Valenciennes lace, with a matching veil and train, which was designed by John Cavanagh. The gown included a piece of lace from Princess Alexandra’s late grandmother, Grand Duchess Elena Vladimirovna of Russia. Her veil was previously worn by Princess Patricia of Connaught. Her tiara belonged to her mother, and she had received it as a wedding gift in 1934. Angus wore morning dress.

Embed from Getty ImagesEmbed from Getty ImagesEmbed from Getty ImagesEmbed from Getty ImagesAfter the ceremony, the pair travelled to St. James’s Palace, where a wedding breakfast was held. Afterwards, they honeymooned on the Balmoral estate. Angus and Princess Alexandra went on to have two children together, James and Marina. They would have celebrated their wedding anniversary today, but unfortunately, Angus Ogilvy (by then Sir

Angus Ogilvy) died 26 December 2004.

The post Royal Wedding Recollections – Princess Alexandra of Kent & The Honourable Angus Ogilvy appeared first on History of Royal Women.

Royal Wedding Recollections – Mary, Queen of Scots & Francis, Dauphin of France

Mary, Queen of Scots, had been sent to France at the age of five as part of a marriage agreement with the future Francis II of France. However, their wedding would not take place until 24 April 1558 at the Cathedral of Notre Dame.

The Notre Dame had been embellished with a special structure to make a sort of open-air theatre with a twelve-foot arch inside. The fleur-de-lys was embroidered everywhere it could be embroidered.1

The procession into the cathedral was led by the Swiss guards, quickly followed by Mary’s uncle Francis, Duke of Guise. Then came Eustace du Bellay, the bishop of Paris, followed by a string of musicians dressed in yellow and red. They were followed by a hundred gentlemen-in-waiting to King Henry II of France and the princes of the blood. Then came the bishops and princes of the church, all magnificently dressed. Finally, the groom entered with Antoine of Bourbon, King of Navarre, and his two younger brothers Charles (later King Charles IX of France) and Henry (later King Henry III of France).2

Mary, Queen of Scots, entered with her soon-to-be father-in-law King Henry II and her cousin, the Duke of Lorraine. She wore a white robe, which defied tradition as white was seen as a mourning colour. Her long train was borne by two young girls. Mary also wore diamonds around her neck, and she wore a golden crown with pearls, rubies, sapphires and several other precious stones.3

Behind Mary came her soon-to-be mother-in-law, Catherine de’Medici, with the Prince of Condé and King Henry’s sister Margaret, Duchess of Berry. Several other princesses and ladies also followed. Joan III, Queen of Navarre, also attended with her young son, the future King Henry IV of France.4

The Archbishop of Rouen married the pair with a ring that King Henry II had, only moments before, taken from his own finger. Following the ceremony, the bishop of Paris said Mass with Henry and Catherine on one side and Mary and Francis on the other. When Mass was over, the parade of nobles began again.

The festivities continued with a long banquet during which Mary suffered from the weight of the crown on her head. A ball followed in the afternoon, and afterwards, the court processed to the palace of parliament. Mary travelled in a golden litter with her mother-in-law as Francis followed them on horseback. They had supper at the palace, followed by yet another ball with masks and mummeries.5

Mary later wrote to her mother about her happiness and how much honour Francis and his parents continually do to her.6

The marriage would not last long. Although Francis succeeded his father as King in 1559, he would die just over a year later at the age of 16. Mary was left a widow at the age of 17.

The post Royal Wedding Recollections – Mary, Queen of Scots & Francis, Dauphin of France appeared first on History of Royal Women.

April 21, 2023

Book News May 2023

Embroidering Her Truth: Mary, Queen of Scots and the Language of Power

Paperback – 19 January 2023 (UK) & 30 May 2023 (US)

In sixteenth-century Europe women’s voices were suppressed and silenced. Even for a queen like Mary, her prime duty was to bear sons. In an age when textiles expressed power, Mary exploited them to emphasise her female agency. From her lavishly embroidered gowns as the prospective wife of the French Dauphin to the fashion dolls she used to encourage a Marian style at the Scottish court and the subversive messages she embroidered in captivity for her supporters, Mary used textiles to advance her political agenda, affirm her royal lineage and tell her own story.

Rasputin and his Russian Queen: The True Story of Grigory and Alexandra

Hardcover – 30 March 2023 (UK) & 30 May 2023 (US)

Rasputin’s relationship with Russia’s last Tsarina, Alexandra, notorious from the famous Boney M song, has never been adequately addressed; biographies are always for one or the other, or simply Alexandra and her husband Nicholas. In this new work, Mickey Mayhew reimagines Alexandra for the #MeToo generation: ‘neurotic’; ‘hysterical’; ‘credulous’ and ‘fanatical’ are shunted aside in favour of a sympathetic reimagining of a reserved and pious woman tossed into the heart of Russian aristocracy, with the sole purpose of providing their patriarchal monarchy with an heir. When the son she prayed for turns out to be a haemophiliac, she forms a friendship with the one man capable of curing the child’s agonising attacks. Some say that between them, Grigori and Alexandra brought down 300 years of Romanov rule and ushered in the Russian Revolution, but theirs was simply the story of a mother fighting for the health of her son against a backdrop of bigotry, sexism and increasing secularism. Bubbling with his trademark bon mots, Mickey Mayhew’s new book breathes fresh life into two of history’s most fascinating – and polarising – figures. She liked to pray and he liked to party, but when they found themselves steering Russia into the First World War, her gender and his class meant that society simply had to crush them. This is the real story of Rasputin and his Russian queen, Alexandra.

Cleopatra’s Daughter: From Roman Prisoner to African Queen

Hardcover –23 May 2023 (US)

The first biography of one of the most fascinating yet long-neglected rulers of the ancient world: Cleopatra Selene, daughter of Antony and Cleopatra.

Anne Boleyn & Elizabeth I: The Mother and Daughter Who Changed History

Kindle Edition – 18 May 2023 (US & UK)

Piecing together evidence from original documents and artefacts, this audiobook tells the fascinating, often surprising story of Anne Boleyn’s relationship with, and influence over her daughter Elizabeth. In so doing, it sheds new light on two of the most famous women in history and how they changed England forever.

Princess Mary: The First Modern Princess

Paperback – 16 May 2023 (US)

Princess Mary was born in 1897. Despite her Victorian beginnings, she strove to make a princess’s life meaningful, using her position to help those less fortunate and defying gender conventions in the process. As the only daughter of King George V and Queen Mary, she would live to see not only two of her brothers ascend the throne but also her niece Queen Elizabeth II.

Queen Elizabeth II: An Oral History

Paperback – 9 May 2023 (US)

Featuring interviews from diverse sources from private staff at Buckingham Palace and family friends, to international figures like Nelson Mandela, it contains a broad spectrum of views on Queen Elizabeth II—her story and her personality and how her life has intersected and impacted others.

The Daughters of George III: Sisters and Princesses

Paperback – 31 May 2023 (US)

The six daughters of George III were raised to be young ladies and each in her time was one of the most eligible women in the world. Tutored in the arts of royal womanhood, they were trained from infancy in the skills vial to a regal wife but as the king’s illness ravaged him, husbands and opportunities slipped away.

Young Queens: Three Renaissance Women and the Price of Power

Hardcover – 11 May 2023 (UK) & 15 August 2023 (US)

Catherine, Mary and Elisabeth lived at the French court together for many years before scattering to different kingdoms. These years bound them to one another through blood and marriage, alliance and friendship, love and filial piety; bonds that were tested when the women were forced to part and take on new roles. To rule, they would learn, was to wage a constant war against the deeply entrenched misogyny of their time. A crown could exalt a young woman. Equally, it could destroy her.

Drawing on new archival research, Young Queens masterfully weaves the personal stories of these three queens into one, revealing their hopes, dreams, desires and regrets in a time when even the most powerful women lived at the mercy of the state.

Henry VIII’s Children: Legitimate and Illegitimate Sons and Daughters of the Tudor King

Hardcover – 30 May 2023 (UK) & 6 August 2023 (US)

Behind the narrative of Henry VIII’s wives, wars, reformation and ruthlessness, there were children, living lives of education among people who cared for them, surrounded by items in generous locations which symbolised their place in their father’s heart. They faced excitement, struggles, and isolation which would shape their own reigns. From the heights of a surviving princess destined and decreed to influence Europe, to illegitimate children scattered to the winds of fortune, the childhoods of Henry VIII’s heirs is one of ambition, destiny, heartache, and triumph.

Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine: Founding an Empire

Paperback – 15 May 2023 (UK) & 22 August 2023 (US)

This book charts the early lives of Henry and Eleanor before they became a European power couple and examines the impact of their union on contemporaries and European politics. It explores the birth of the Angevin Empire that spread from Northumberland to the Mediterranean, and the causes of the disintegration of that vast territory, as well as the troublesome relationships between Henry and his sons, who dragged their father to the battlefield to defend his lands from their ambitious intriguing.

Messalina: A Story of Empire, Slander and Adultery

Hardcover – 11 May 2023 (UK)

In her new life of Messalina, the classicist Honor Cargill-Martin reappraises one of the most slandered and underestimated female figures of ancient history. Looking beyond the salacious anecdotes, she finds a woman battling to assert her position in the overwhelmingly male world of imperial Roman politics – and succeeding. Intelligent, passionate, and ruthless when she needed to be, Messalina’s story encapsulates the cut-throat political manoeuvring and unimaginable luxury of the Julio-Claudian dynasty in its heyday.

Cargill-Martin sets out not to ‘salvage’ Messalina’s reputation, but to look at her life in the context of her time. Above all, she seeks to reclaim the humanity of a life story previously circumscribed by currents of high politics and patriarchy.

The post Book News May 2023 appeared first on History of Royal Women.

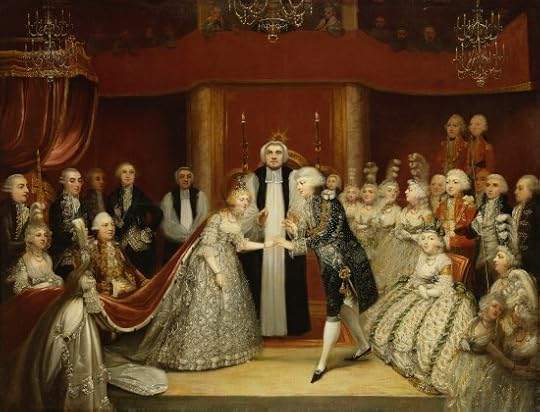

Earliest surviving British royal wedding dress goes on display

The wedding dress of Princess Charlotte of Wales, the only legitimate child of the future King George IV, is going on display for the time in over a decade. It will be part of the new exhibition at The Queen’s Gallery, Buckingham Palace: Style & Society: Dressing the Georgians.

Click to view slideshow.The exhibition explores the fashion of Georgian Britain through clothes, jewellery, paintings and accessories. All layers of society will be covered.

Princess Charlotte’s dress is the only surviving royal wedding gown from the Georgian period, although it does appear to have been altered somewhat. She followed the European tradition of wearing silver, despite white wedding dresses already being a popular choice.

Royal Collection Trust / © His Majesty King Charles III 2023

Royal Collection Trust / © His Majesty King Charles III 2023Her mother also wore silver for her wedding. Also on display, for the first time, is a portrait of that wedding ceremony with the silver and gold dress samples for the bride and the royal guests.

Royal Collection Trust / © His Majesty King Charles III 2023

Royal Collection Trust / © His Majesty King Charles III 2023Also on display will be diamond rings given to Queen Charlotte on her wedding day and a bracelet with lockets containing locks of hair.

Royal Collection Trust / © His Majesty King Charles III 2023

Royal Collection Trust / © His Majesty King Charles III 2023Style & Society: Dressing the Georgians is at The Queen’s Gallery, Buckingham Palace, 21 April – 8 October 2023.

The post Earliest surviving British royal wedding dress goes on display appeared first on History of Royal Women.

April 20, 2023

Li Yuqin – The Last Imperial Concubine of China (Part two)

Li Yuqin (also formally known as Noble Lady Fu) was the fourth wife of Puyi, the Last Emperor of China. Lu Yuqin was the last Imperial Concubine in Chinese history. However, in 1945, Li Yuqin’s life as an imperial concubine had abruptly come to an end. Li Yuqin would soon face a series of hardships. She would constantly struggle with poverty as she tried hard to find a good job. She also faced discrimination because she married the Emperor, whom many people believed to be a traitor.[1] These difficulties led Li Yuqin to divorce the Last Emperor of China.

On 18 August 1945, Manchukuo collapsed, and the imperial family were forced to leave Changchun Palace. The imperial family left Changchun and sought refuge in Dalizigou.[2] However, the situation grew so direr that Emperor Puyi began to fear for his life.[3] Thinking solely of his own safety, he left Empress Wanrong and Noble Lady Fu behind.[4] He took a plane where the pilot betrayed him.[5] Emperor Puyi was captured and became a prisoner of the Soviet Union.[6] Because both Empress Wanrong and Noble Lady Fu were abandoned by Emperor Puyi, they began to depend on each other.[7] They were so grateful for each other’s company because they did not know the outcome of their situation.[8]

Since Noble Lady Fu was a hostage under the Chinese army, she was under intense scrutiny.[9] The Chinese army asked her to join the army, but her devotion to Emperor Puyi led her to refuse.[10] Then, they began to pressure her to divorce the Emperor.[11] They assured her that she could go home to her family once she did.[12] Noble Lady Fu initially refused because of her fondness for Emperor Puyi.[13] She believed that she should remain faithful to her husband.[14] However, the army let her parents visit Noble Lady Fu and persuaded her to divorce the Emperor so that she could return home.[15] Noble Lady Fu realized that there was no choice but to agree.[16]

Noble Lady Fu wrote a divorce letter and was allowed to return home.[17] However, the divorce letter was considered to be insufficient for a divorce.[18] Noble Lady Fu was still considered to be the legal wife of Emperor Puyi.[19] She felt guilty about leaving Empress Wanrong behind, but there was nothing she could do.[20] She went home, where she grieved for betraying her husband.[21] She tried to become a Buddhist nun. However, none of the nunneries would accept her because she was a member of the Chinese imperial family.[22]

In 1946, Noble Lady Fu left her parents’ home to live with Emperor Puyi’s relatives in Tianjin. In Tianjin, Prince Puxiu became Noble Lady Fu’s tutor.[23] Noble Lady Fu learned calligraphy, poems, and female virtue.[24] However, the imperial family often struggled with hunger.[25] There was not enough food, so the imperial family often went hungry.[26] Because Noble Lady Fu was not from the Manchu Eight Banners clan, Emperor Puyi’s relatives began to look down on her.[27] Noble Lady Fu began to wash laundry and do other chores for them.[28] They would not even give her the money to buy toilet paper![29] She stayed with Emperor Puyi’s family for seven years.

In 1953, Noble Lady Fu returned to Changchun to take care of her mother while still waiting for news of Emperor Puyi.[30] From 1953-1956, Noble Lady Fu went through a series of temporary jobs such as working in food factories, as a governess, as a cleaner, and as a printing factory worker.[31] Because she was Emperor Puyi’s wife, many people looked at her with hatred and called her a traitor.[32] Noble Lady Fu kept searching for news of Emperor Puyi, but her search remained ineffective. She did not know whether her husband was dead or alive.[33]

In the summer of 1955, Noble Lady Fu finally received a letter from her husband. Noble Lady Fu was so relieved and happy to have received word from Emperor Puyi.[34] The letter stated that he was currently a prisoner in Fushun, China.[35] Noble Lady Fu wrote him a letter back. The letter that Emperor Puyi received touched him so deeply while he was undergoing difficulties in prison.[36]

Noble Lady Fu visited her husband three times. In order to see him, she had to borrow money from her friends.[37] While Emperor Puyi was genuinely happy to see her, seeing Emperor Puyi in prison reminded Noble Lady Fu of her hardships.[38] Noble Lady Fu had struggled with poverty and attracted hatred from strangers for being the Emperor’s wife.[39] Emperor Puyi seemed oblivious to her own sufferings and the sacrifices she had made for him.[40] Emperor Puyi also did not seem like he would get out of prison anytime soon.[41] Noble Lady Fu began to wonder if it was worth it to remain married to the Emperor.[42]

In August of 1956, Noble Lady Fu finally got a job as a librarian at Changchun City Library.[43] Noble Lady Fu loved her job.[44] However, she was given an ultimatum. She either had to divorce Emperor Puyi or lose her job.[45] Noble Lady Fu did not want to quit her job.[46] Therefore, she decided it was time to discuss divorce with Emperor Puyi.[47]

On 25 December 1956, Noble Lady Fu visited Emperor Puyi in prison and painfully told him that she wanted a divorce.[48] Emperor Puyi was heartbroken to hear Noble Lady Fu’s request to divorce him.[49] He told her he would never agree to it.[50] However, Noble Lady Fu was determined. She told him she wanted to have a normal life and be free from discrimination.[51] Throughout the conversation, Noble Lady Fu was crying because she still loved him and did not want to part from him.[52] Emperor Puyi went back to his cell, where he broke down in tears about the inevitable ending of his marriage to Noble Lady Fu.[53]

Emperor Puyi asked the Chinese government for help in reconciling his marriage with Noble Lady Fu.[54] During Noble Lady Fu’s fifth visit, the government allowed Emperor Puyi to cohabit with his wife.[55] Noble Lady Fu and Emperor Puyi were given a room with a double bed.[56] This was the only time that they had ever consummated their marriage.[57] The government had hoped that this would lead to a reconciliation between the couple.[58] Instead, it only strengthened Noble Lady Fu’s resolve to divorce Emperor Puyi.[59]

On 16 March 1957, Noble Lady Fu officially filed for divorce. In May 1958, the divorce was granted.[60] She no longer held the title of Noble Lady Fu.[61] She was married to Emperor Puyi for fifteen years. Li Yuqin became a member of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party.[62] In 1958, Li Yuqin married Huang Yugeng, an engineer at Jilin Provincial Radio Station.[63] The couple produced a son.[64] In the 1980s, Li Yuqin was a member of the advisory council of the Changchun City Government.[65] On 24 April 2001, Li Yuqin died of cirrhosis in Changchun.[66] She was 73 years old.[67] Li Yuqin’s death represented the passing of Imperial China and the Qing Dynasty.

Sources:

DayDayNews. (June 15, 2020). “The last imperial concubine of the Qing Dynasty, who lived to the 21st century, told her secret marriage to Puyi before her death”. Retrieved on 11 November 22 from https://daydaynews.cc/en/history/amp/....

iNews. (n.d.). “She was the last imperial concubine of the Qing Dynasty. She lived to 2001 and told her marriage secret with Puyi on her deathbed”. Retrieved on 11 November 2022 from https://inf.news/en/history/cc154bac8....

Poole, T. (June 27, 1997). “The Last Concubine”. The Independent. Retrieved on 11 November 2022 from https://www.independent.co.uk/news/th....

The New York Times. (April 28, 2001). “Li Yuqin; Chinese Emperor’s Widow, 73”. Retrieved on 11 November 2022 from https://www.nytimes.com/2001/04/28/wo....

Wang, Q. (2014). The Last Emperor and His Five Wives. (Translated by Jiaquan Han et al.). Beijing, China: China Intercontinental Press.

[1] Wang, 2014

[2] Wang, 2014

[3] Wang, 2014

[4] Poole, The Independent, 27 June 1997, “The Last Concubine”

[5] Poole, The Independent, 27 June 1997, “The Last Concubine”

[6] Poole, The Independent, 27 June 1997, “The Last Concubine”

[7] Wang, 2014

[8] Wang, 2014

[9] Wang, 2014

[10] Wang, 2014

[11] Wang, 2014

[12] Wang, 2014

[13] Wang, 2014

[14] Wang, 2014

[15] Wang, 2014

[16] Wang, 2014

[17] DayDayNews, 15 June 2020, “The last imperial concubine of the Qing Dynasty, who lived to the 21st century, told her secret marriage to Puyi before her death”

[18] Wang, 2014

[19] Wang, 2014

[20] Wang, 2014

[21] Wang, 2014

[22] Wang, 2014

[23] Wang, 2014

[24] Wang, 2014

[25] Wang, 2014

[26] Wang, 2014

[27] Wang, 2014

[28] Wang, 2014

[29] Wang, 2014

[30] Wang, 2014

[31] Wang, 2014

[32] Wang, 2014

[33] Wang, 2014

[34] Wang, 2014

[35] Wang, 2014

[36] Wang, 2014

[37] Wang, 2014

[38] Wang, 2014

[39] Wang, 2014

[40] Wang, 2014

[41] Wang, 2014

[42] Wang, 2014

[43] Poole, The Independent, 27 June 1997, “The Last Concubine”

[44] Poole, The Independent, 27 June 1997, “The Last Concubine”

[45] Poole, The Independent, 27 June 1997, “The Last Concubine”

[46] Poole, The Independent, 27 June 1997, “The Last Concubine”

[47] Wang, 2014

[48] Wang, 2014

[49] Wang, 2014

[50] DayDayNews, 15 June 2020, “The last imperial concubine of the Qing Dynasty, who lived to the 21st century, told her secret marriage to Puyi before her death”

[51] Wang, 2014

[52] Wang, 2014

[53] Wang, 2014

[54] Wang, 2014

[55] Poole, The Independent, 27 June 1997, “The Last Concubine”

[56] Poole, The Independent, 27 June 1997, “The Last Concubine”

[57] Poole, The Independent, 27 June 1997, “The Last Concubine”

[58] Poole, The Independent, 27 June 1997, “The Last Concubine”

[59] Poole, The Independent, 27 June 1997, “The Last Concubine”

[60] Wang, 2014

[61] Wang, 2014

[62] Wang, 2014

[63] iNews, n.d., “She was the last imperial concubine of the Qing Dynasty. She lived to 2001 and told her marriage secret with Puyi on her deathbed”

[64] iNews, n.d., “She was the last imperial concubine of the Qing Dynasty. She lived to 2001 and told her marriage secret with Puyi on her deathbed”

[65] The New York Times, 28 April 2001, “Li Yuqin; Chinese Emperor’s Widow, 73”

[66] The New York Times, 28 April 2001, “Li Yuqin; Chinese Emperor’s Widow, 73”

[67] The New York Times, 28 April 2001, “Li Yuqin; Chinese Emperor’s Widow, 73”

The post Li Yuqin – The Last Imperial Concubine of China (Part two) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

April 19, 2023

Li Yuqin – The Last Imperial Concubine of China (Part one)

Li Yuqin (formally known as Noble Lady Fu) was the fourth wife of Puyi, the Last Emperor of China. Li Yuqin was China’s Last Imperial Concubine. Li Yuqin was a schoolgirl when she was chosen to become a concubine to Emperor Puyi. Yet, her legendary life was often tumultuous. Li Yuqin was the last living symbol of Imperial China.

On 15 July 1928, Li Yuqin was born in Shandong Province.[1] She came from a very poor family.[2] Her father, Li Wancai, spent his life working as a waiter at various restaurants.[3] Her mother was Wang Xiuru. She was the sixth child in the family. She had two older brothers, three older sisters and one younger sister. When she was seven, the family moved to the slums of Changchun.[4] In her early childhood, Li Yuqin learned to sing from Catholic priests.[5] She and her younger sister also enrolled in a free primary school. She was very diligent in her studies.[6] After she graduated from primary school, Li Yuqin enrolled in Nanguan National High-grade School, which was famous for its highly qualified teachers.[7]

On 13 March 1942, Imperial Consort Tan Yuling suddenly died. Puyi (the puppet Emperor of the Japanese state of Manchukuo) did not have the will to choose another concubine but was pressured by Yoshioka, the Lieutenant General of Japan.[8] Yoshioka wanted him to choose a Japanese wife, but Emperor Puyi did not trust the Japanese.[9] Instead, he insisted on having a Chinese wife.[10] The Japanese went to Li Yuqin’s school and took photographs of all the girls, including Li Yuqin.[11] The girls did not know why they were being photographed.[12] The photographs were then sent to Emperor Puyi. Emperor Puyi looked at the photographs, and his eyes rested on Li Yuqin. He chose her because she seemed innocent and easy to manipulate.[13]

Once he made his decision, the Japanese went to her home and told the family that Li Yuqin was selected to become Emperor Puyi’s student.[14] She would study under Emperor Puyi and go to college. Her parents were suspicious about what it meant to be the Emperor’s student.[15] They initially refused but submitted to the Emperor’s will.[16] Li Yuqin packed her schoolbooks and bade farewell to her family.[17] Before she arrived at Changchun Palace, she was taken to Princess Yunhe (Emperor Puyi’s younger sister), who subjected her to an intense medical examination.[18]

Li Yuqin was taken to Changchun Palace. Upon her arrival, she was brought to the Emperor’s study. She met Emperor Puyi for the first time. She made three kowtows. Emperor Puyi pulled her up and was alarmed that her hands were hot.[19] He asked if she had a fever, and she replied that she had a headache.[20] Emperor Puyi sent for a doctor to give her an injection.[21] After she was injected, he told her to get some rest. Emperor Puyi’s care and attention left a favourable impression on her.[22] He seemed kind and caring. Li Yuqin believed that she would have a comfortable life in the palace as the Emperor’s student.[23]

The next day, Li Yuqin and Emperor Puyi had another meeting. Emperor Puyi showed Li Yuqin his portrait and asked if she liked it.[24] However, Li Yuqin told him that it did not resemble him at all, to which Emperor Puyi agreed.[25] Emperor Puyi asked Li Yuqin about her background. After she told him about her life, she asked Emperor Puyi about meeting her new teacher.[26] Emperor Puyi told her that they were still looking for one.[27] This raised Li Yuqin’s suspicions, and she wondered if she had been tricked into entering the palace.[28] Emperor Puyi did not know the Japanese had tricked her into coming to the palace as his student.[29] He assumed that she already knew that she would become his new concubine.[30] He still did not trust her because he thought that she may be a Japanese spy.[31] The two ate dinner quietly. The conversation consisted of him liking a dish and insisting Li Yuqin eat more.[32] After dinner, they prayed and retired to their own rooms.

Li Yuqin took etiquette lessons taught by Princess Yunhe. Since she was about to become a member of the imperial family, Li Yuqin’s every move had to be perfect.[33] If she was not, the servants and the Emperor’s relatives would laugh at her behind her back.[34] After two weeks of etiquette lessons, Li Yuqin realized that she was not in the palace to become the Emperor’s student but to be his wife.[35] Li Yuqin was not unhappy with the prospect of marrying the Emperor.[36] Instead, she had become fond of him because he was helpful and caring.[37]

In April 1943, Li Yuqin married Emperor Puyi. They were married in a European style rather than a traditional Chinese wedding.[38] The ceremony was held at a Catholic church, and Emperor Puyi put a diamond ring on Li Yuqin’s finger.[39] Emperor Puyi was very happy with Li Yuqin and had genuinely fallen in love with her.[40] In May, he conferred upon Li Yuqin the title of Noble Lady Fu. After the ceremony, Emperor Puyi held a grand banquet for his new concubine, which all the ministers attended.[41]

Shortly after Noble Lady Fu’s conferment ceremony, Noble Lady Fu saw her parents for the first time.[42] Her parents were honoured to be related to royalty and were guests at Changchun Palace.[43] When Emperor Puyi learned of Li Wancai’s occupation as a waiter, he was so embarrassed by his father-in-law’s lowly job that he ordered him to quit.[44] Emperor Puyi was afraid that people would mock him for having a waiter as his father-in-law.[45] Li Wancai agreed, but he was so poor that he could not make ends meet. Emperor Puyi refused to help his wife’s family with their money problems.[46] Therefore, Li Wancai had no choice but to return to his job as a waiter.[47]

Noble Lady Fu spent time in the palace watching Charlie Chaplin movies and listening to music.[48] She instructed the daughters of Emperor Puyi’s siblings in the Confucian classics.[49] She would play tennis and knit sweaters.[50] Noble Lady Fu also spent her time singing to Emperor Puyi. Emperor Puyi also became her teacher. He taught her Chinese Classics and Buddhism.[51] Due to her husband’s influence, Noble Lady Fu became a staunch Buddhist.[52]

While Noble Lady Fu and Emperor Puyi were happy, their marriage remained unconsummated.[53] Emperor Puyi was sexually abused as a child, and it had traumatized him.[54] Emperor Puyi tried to get over his trauma and consummate his marriage by taking hormone injections and medicines.[55] However, it remained ineffective.[56] Noble Lady Fu was so disappointed that their marriage remained unconsummated that she began to yell at her servants.[57] She even stopped singing for Emperor Puyi.[58]

On 18 August 1945, Manchukuo collapsed, and the imperial family were forced to leave Changchun Palace. With the downfall of the Manchukuo state, Li Yuqin’s life as an imperial concubine ended. Li Yuqin would no longer live a life of luxury. She would soon learn that being married to the Emperor would have consequences. In my next article, I will detail the hardships that Li Yuqin faced while being married to Emperor Puyi and her eventual decision to divorce him.

Part two coming soon.

Sources:

Laitimes. (November 6, 2021).“Originally a poor girl, why did Li Yuqin become the “fugui person” of the puppet Manchukuo emperor?”. Retrieved on 11 November 2022 from https://www.laitimes.com/en/article/m....

Poole, T. (June 27, 1997). “The Last Concubine”. The Independent. Retrieved on 11 November 2022 from https://www.independent.co.uk/news/th....

Wang, Q. (2014). The Last Emperor and His Five Wives. (Translated by Jiaquan Han et al.). Beijing, China: China Intercontinental Press.

[1] Wang, 2014

[2] Wang, 2014

[3] Wang, 2014

[4] Wang, 2014

[5] Wang, 2014

[6] Wang, 2014

[7] Wang, 2014

[8] Laitimes, 6 November 2021, “Originally a poor girl, why did Li Yuqin become the “fugui person” of the puppet Manchukuo emperor?”

[9] Laitimes, 6 November 2021, “Originally a poor girl, why did Li Yuqin become the “fugui person” of the puppet Manchukuo emperor?”

[10] Laitimes, 6 November 2021, “Originally a poor girl, why did Li Yuqin become the “fugui person” of the puppet Manchukuo emperor?”

[11] Wang, 2014

[12] Wang, 2014

[13] Wang, 2014

[14] Poole, The Independent, 27 June 1997, “The Last Concubine”

[15] Wang, 2014

[16] Wang, 2014

[17] Wang, 2014

[18] Wang, 2014

[19] Wang, 2014

[20] Wang, 2014

[21] Poole, The Independent, 27 June 1997, “The Last Concubine”

[22] Wang, 2014

[23] Wang, 2014

[24] Wang, 2014

[25] Wang, 2014

[26] Wang, 2014

[27] Wang, 2014

[28] Wang, 2014

[29] Wang, 2014

[30] Wang, 2014

[31] Wang, 2014

[32] Wang, 2014

[33] Wang, 2014

[34] Wang, 2014

[35] Wang, 2014

[36] Wang, 2014

[37] Wang, 2014

[38] Wang, 2014

[39] Wang, 2014

[40] Wang, 2014

[41] Wang, 2014

[42] Wang, 2014

[43] Wang, 2014

[44] Wang, 2014

[45] Wang, 2014

[46] Wang, 2014

[47] Wang, 2014

[48] Wang, 2014

[49] Wang, 2014

[50] Wang, 2014

[51] Wang, 2014

[52] Wang, 2014

[53] Wang, 2014

[54] Wang, 2014

[55] Wang, 2014

[56] Wang, 2014

[57] Wang, 2014

[58] Wang, 2014

The post Li Yuqin – The Last Imperial Concubine of China (Part one) appeared first on History of Royal Women.