Moniek Bloks's Blog, page 41

August 9, 2024

Book Review: Young Queens: Three Renaissance Women and the Price of Power by Leah Redmond Chang

*review copy*

Young Queens: Three Renaissance Women and the Price of Power by Leah Redmond Chang follows the stories of Catherine de’ Medici, her daughter Elisabeth, Queen of Spain, and her daughter-in-law, Mary, Queen of Scots.

Particularly Mary, Queen of Scots, has been covered extensively by historians, so I was glad to see the inclusion of Elisabeth of Valois, who has not received the same treatment, even though the two women practically grew up together. Catherine de’ Medici has also received her fair share of biographies, but that doesn’t mean that Young Queens doesn’t add anything.

The power dynamic and relationship between the women are very interesting to read about, and you can tell that the author has done her research. The book flows really well, despite covering several decades, and does not become monotonous.

I would highly recommend this book.

Young Queens: Three Renaissance Women and the Price of Power by Leah Redmond Chang is available now in the US and the UK.

The post Book Review: Young Queens: Three Renaissance Women and the Price of Power by Leah Redmond Chang appeared first on History of Royal Women.

August 8, 2024

The Cameo Tiara

The Cameo Tiara, which belongs to the Swedish royal family, was originally a gift from Emperor Napoleon I of France to his first wife, Josephine, in 1809. It was part of a parure that also included a necklace, bracelet, and earrings. A brooch was later added.

Embed from Getty ImagesThe cameos on the gold tiara are surrounded by seed pearls, and there is not a single diamond.

Josephine of Leuchtenberg wearing the tiara (public domain)

Josephine of Leuchtenberg wearing the tiara (public domain)It was inherited by Josephine’s son, Eugene de Beauharnais, who then passed it to his daughter, Josephine of Leuchtenberg. She passed the parure to her daughter, Princess Eugenie, and she passed it to her nephew, Prince Eugen. Eugen then gave the parure to Princess Sibylla of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha as a wedding gift in 1932. She became the mother of King Carl XVI Gustaf of Sweden, and the parure has remained with the Swedish royal family since then.1

Embed from Getty ImagesOver time, the Cameo Tiara has become a wedding favourite. It was worn by King Carl XVI Gustaf’s two sisters, Princess Birgitta and Princess Desiree, as well as his wife, Queen Silvia. It was most recently worn as a bridal tiara by his daughter, Crown Princess Victoria, for her wedding in 2010.

Embed from Getty ImagesThe post The Cameo Tiara appeared first on History of Royal Women.

August 7, 2024

The Yellow Palace in Copenhagen – Birthplace of a Queen and an Empress

The Yellow Palace in Copenhagen is perhaps most famous as the birthplace of Queen Alexandra, the consort of King Edward VII, and her sister Dagmar. the consort of Emperor Alexander III of Russia.

Their parents, then known as Prince and Princess Christian (the future King Christian IX and Louise of Hesse-Kassel), were given the Yellow Palace as a residence, and their first child, Frederick, was born there in 1843. The following year, the future Queen Alexandra was born there in “a room overlooking the courtyard.”1 Alexandra was named for her mother’s sister-in-law, Grand Duchess Alexandra Nikolaevna of Russia, who had been pregnant at the same time as Louise. Tragically, both the Grand Duchess and her baby died during a visit to Russia in August. Baby Alexandra was christened at the palace, in a silver-gilt font used in the Danish royal family.

The family lived in the Yellow Palace mostly on Prince Christian’s army salary, and it was an economical household. The Yellow Palace was not far from the water, and Alexandra liked to watch the ships in the harbour.

Photo by Moniek Bloks

Photo by Moniek BloksIn 1853, Prince Christian was selected as the heir presumptive to the Danish throne, and although this came with improved status and additional residences, the family continued to live at the Yellow Palace as well.

After Alexandra was confirmed in 1860, she was given her own bedroom at the Yellow Palace. She had previously shared a room with her sister Dagmar. Her new room was upholstered in blue and had her piano, worktable and a cabinet.2 When she left Denmark to marry the Prince of Wales, she said farewell to her former teachers during a private audience at the Yellow Palace.3

Alexandra’s younger brother Valdemar was the last royal to live in the Yellow Palace. It currently houses the Lord Chamberlain’s Office.

The post The Yellow Palace in Copenhagen – Birthplace of a Queen and an Empress appeared first on History of Royal Women.

August 6, 2024

Empress Dowager Dou Miao – The indecisive Regent

Empress Dou Miao was the third Empress of Emperor Huan of the Eastern Han Dynasty. Emperor Huan disliked her and neglected her.[1] When Emperor Huan died, she became Empress Dowager. Empress Dowager Dou Miao has often been criticised for being an indecisive Regent.[2] It is because of her indecisiveness that she ends up having a tragic end.[3]

In circa 151 C.E., Empress Dou Miao was born in Pingling in Fufeng County (modern-day Xianyang City in Shaanxi Province).[4] Her father was Dou Wu, who taught the classics and ran a private school.[5] Dou Miao was descended from the legendary warlord Dou Rong.[6] She was also a distant cousin of Empress Dowager Dou.[7]

On 27 March 165 C.E., Empress Deng Mengnu was deposed, which left the Empress position vacant.[8] Dou Miao entered Emperor Huan’s harem as a possible candidate for Empress.[9] She was promoted to Worthy Lady (the highest rank below Empress).[10] Her appointment as Worthy Lady allowed Dou Wu to be promoted to Gentleman-of-the-Palace.[11] Still, Worthy Lady Dou Miao was still not appointed Empress. This was because Emperor Huan wanted to promote his favourite, Consort Tian Sheng (who was the lowest-ranked imperial concubine in his harem), as his Empress instead.[12] However, his ministers opposed Consort Tian Sheng as his Empress because of her lowly background.[13] They advised Emperor Huan to appoint Consort Dou Miao as his Empress because of her prestigious background.[14] At last, Emperor Huan agreed to his ministers’ counsel.[15]

On 10 December 165 C.E., Dou Miao was invested as Empress of China. Dou Wu was promoted to colonel of a unit in the Northern Army.[16] He was also made a Marquis and was given revenue from 5,000 households.[17] However, Emperor Huan did not favour Empress Dou Miao.[18] He did not even try to visit her.[19] If he did see her, the visits “were extremely rare.”[20] He preferred spending time with Consort Tian Sheng and eight of his other unnamed favourite imperial concubines.[21] Thus, Empress Dou Miao was very lonely.[22] She became very jealous of Consort Tian Sheng.[23] Throughout her reign as Empress Consort, Emperor Huan grew to dislike Empress Dou Miao’s father, Dou Wu.[24] He also continued to neglect Empress Dou Miao.[25]

In December of 167 C.E., Emperor Huan fell seriously ill. On 25 January 168 C.E., Emperor Huan died. Upon his death, Emperor Huan asked for Consort Tian Sheng and his other eight favourite imperial concubines to be promoted to Worthy Ladies.[26] However, Empress Dou Miao was now Empress Dowager. She and her father, Dou Wu, were the most powerful people in China.[27] She refused for them to be promoted.[28] She executed Consort Tian Sheng out of jealousy.[29] She spared the other eight favourite imperial concubines of Emperor Huan.[30]

Emperor Huan had no sons.[31] Empress Dowager Dou Miao and Dou Wu settled on the twelve-year-old Prince Liu Hong, the Marquis of Jiedu.[32] He was the great-great-grandson of Emperor Zhang of the Eastern Han Dynasty.[33] On 17 February 167 C.E., Prince Liu Hong ascended the throne as Emperor Ling. Because he was still very young, Empress Dowager Dou Miao became Regent.[34]

The Dou family was the most powerful family in China.[35] Dou Wu became General-in-Chief.[36] Dou Wu also formed close partnerships with both Chen Fan and Liu Shu.[37] They became known as the “Three Monarchs.”[38] However, Dou Wu found himself caught in a power struggle with the palace eunuchs. Since Emperor Huan’s reign, they were very influential in government affairs and were very powerful.[39] Dou Wu, Chen Fan, and Liu Shu wanted to destroy the palace eunuchs, particularly Cao Jie and Wang Fu, who were still in charge of government affairs.[40]

Dou Wu asked Empress Dowager Dou Miao to kill the palace eunuchs.[41] However, Empress Dowager Dou Miao remained indecisive.[42] She did not want to kill the palace eunuchs because they respected and flattered her.[43] Thus, she ignored her father’s request.[44] Months passed, and Empress Dowager Dou Miao still remained indecisive.[45]

In the autumn of 167 C.E., Dou Wu realised that he could not rely on his daughter, Empress Dowager Dou Miao, to handle the matter.[46] Dou Wu, Chen Fan, and Liu Shu ordered the arrest of Empress Dowager Dou Miao’s favourite palace eunuchs named Guanba and Su Kang.[47] However, the palace eunuchs went to Emperor Ling and asked for his support.[48] Emperor Ling agreed. Cao Jie and the other palace eunuchs arrested Dou Wu and his family.[49] Dou Wu and his son committed suicide.[50] The rest of his family members were exiled to modern-day Vietnam.[51] Chen Fan and his supporters were killed.[52]

Empress Dowager Dou Miao was placed under house arrest in the Southern Palace at Luoyang.[53] She was often abused by her palace eunuch jailers.[54] In the winter of 171 C.E., Emperor Ling visited her and was concerned about her health.[55] A palace eunuch requested that she be given medicine.[56] Emperor Ling agreed. However, the palace eunuch was falsely charged with impiety and was executed.[57] On 18 July 172 C.E., Empress Dowager Dou Miao died “from grief.”[58] Yet, many historians believe that the palace eunuchs assassinated her.[59] The palace eunuchs requested for Emperor Ling to demote her to Worthy Lady.[60] However, Emperor Ling determined that she should be buried with the honours befitting an Empress Dowager.[61] On 8 August 172 C.E., Empress Dowager Dou Miao was buried in the same tomb as Emperor Huan in Xuanling.[62] She was given the posthumous name of Empress Huansi.[63]

Empress Dowager Dou Miao was from a noble family. However, she was neglected by her husband, Emperor Huan. There were times in which Empress Dowager Dou Miao was decisive.[64] This is especially evident when she kills her rival, Consort Tian Sheng.[65] When it came to the matter of eliminating the palace eunuchs, Empress Dowager Dou Miao was very indecisive.[66] Her indecisiveness led to the loss of her father, her brother, and her own life. If she had been more assertive on matters of the most importance, then her ending, as well as the fate of the Eastern Han Dynasty, would have been very different.[67] Instead, the palace eunuchs continued to remain in power, which led to the decline and fall of the Eastern Han Dynasty.[68]

Sources:

De Crespigny, R. (2015). “Dou Miao, Empress of Emperor Huan”. Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Women: Antiquity Through Sui, 1600 B.C.E. – 618 C.E. (L. X. H. Lee, Ed.; A. D. Stefanowska, Ed.; S. Wiles, Ed.). NY: Routledge. pp. 128-132.

iMedia. (n.d.). “Dou Miao: No mercy towards rivals in love, but indecision towards eunuchs and finally a bleak evening scene”. Retrieved on 20 October 2023 from https://min.news/en/history/760b705ab....

iMedia. (n.d.). “Reading Seals and Knowing the Ancients: Appreciation of the Empress Huansi of the Eastern Han Dynasty “Dou Miao” Young Phoenix Niyu Seal”. Retrieved on 20 October 2023 from https://min.news/en/news/2622c54f4c6a....

iMedia. (n.d.). “The three empresses of Emperor Huan of the Han Dynasty: jealousy became mad and the end was bleak”. Retrieved on 20 October 2023 from https://min.news/en/news/578c75bfafea....

iNews. (n.d.). “Dou Miao, the Empress Dowager of the Eastern Han Dynasty, opposed her father, Dou Wu, to eradicate the eunuch. Why did the eunuch want to imprison Dou Miao and destroy the Dou family?”. Retrieved on 20 October 2023 from https://inf.news/en/history/4d737ab65....

iNews. (n.d.). “Treating rivals without mercy, but being indecisive when dealing with eunuchs, the final night scene is bleak”. Retrieved on 20 October 2023 from https://inf.news/en/history/af81add48....

McMahon, K. (2013). Women Shall Not Rule: Imperial Wives and Concubines in China from Han to Liao. NY: Rowman and Littlefield.

[1] De Crespigny, 2015

[2] De Crespigny, 2015

[3] De Crespigny, 2015

[4] iMedia, n.d., “Reading Seals and Knowing the Ancients: Appreciation of the Empress Huansi of the Eastern Han Dynasty “Dou Miao” Young Phoenix Niyu Seal”

[5] De Crespigny, 2015

[6] De Crespigny, 2015

[7] De Crespigny, 2015

[8] De Crespigny, 2015

[9] De Crespigny, 2015

[10] De Crespigny, 2015

[11] De Crespigny, 2015

[12] De Crespigny, 2015

[13] De Crespigny, 2015

[14] De Crespigny, 2015

[15] De Crespigny, 2015

[16] De Crespigny, 2015

[17] De Crespigny, 2015

[18] De Crespigny, 2015

[19] De Crespigny, 2015

[20] McMahon, 2013, p. 107

[21] De Crespigny, 2015

[22] iNews, n.d., “Treating rivals without mercy, but being indecisive when dealing with eunuchs, the final night scene is bleak”

[23] iMedia, n.d., “Dou Miao: No mercy towards rivals in love, but indecision towards eunuchs and finally a bleak evening scene”

[24] De Crespigny, 2015

[25] De Crespigny, 2015

[26] De Crespigny, 2015

[27] De Crespigny, 2015

[28] De Crespigny, 2015

[29] McMahon, 2013

[30] McMahon, 2013

[31] De Crespigny, 2015

[32] De Crespigny, 2015

[33] McMahon, 2013

[34] De Crespigny, 2015

[35] De Credpigny, 2015

[36] De Crespigny, 2015

[37] De Crespigny, 2015; iNews, n.d. “Dou Miao, the Empress Dowager of the Eastern Han Dynasty, opposed her father, Dou Wu, to eradicate the eunuch. Why did the eunuch want to imprison Dou Miao and destroy the Dou family?”

[38] iNews, n.d., “Dou Miao, the Empress Dowager of the Eastern Han Dynasty, opposed her father, Dou Wu, to eradicate the eunuch. Why did the eunuch want to imprison Dou Miao and destroy the Dou family?”, para. 10

[39] De Crespigny, 2015

[40] iNews, n.d., “Dou Miao, the Empress Dowager of the Eastern Han Dynasty, opposed her father, Dou Wu, to eradicate the eunuch. Why did the eunuch want to imprison Dou Miao and destroy the Dou family?”

[41] iNews, n.d., “Treating rivals without mercy, but being indecisive when dealing with eunuchs, the final night scene is bleak”

[42] iNews, n.d., “Treating rivals without mercy, but being indecisive when dealing with eunuchs, the final night scene is bleak”

[43] iNews, n.d., “Dou Miao, the Empress Dowager of the Eastern Han Dynasty, opposed her father, Dou Wu, to eradicate the eunuch. Why did the eunuch want to imprison Dou Miao and destroy the Dou family?”

[44] iNews, n.d., “Dou Miao, the Empress Dowager of the Eastern Han Dynasty, opposed her father, Dou Wu, to eradicate the eunuch. Why did the eunuch want to imprison Dou Miao and destroy the Dou family?”

[45] De Crespigny, 2015

[46] De Crespigny, 2015

[47] De Crespigny, 2015; iNews, n.d., “Dou Miao, the Empress Dowager of the Eastern Han Dynasty, opposed her father, Dou Wu, to eradicate the eunuch. Why did the eunuch want to imprison Dou Miao and destroy the Dou family?”

[48] De Crespigny, 2015

[49] iMedia, n.d., “Dou Miao: No mercy towards rivals in love, but indecision towards eunuchs and finally a bleak evening scene”

[50] iMedia, n.d., “Dou Miao: No mercy towards rivals in love, but indecision towards eunuchs and finally a bleak evening scene”

[51] De Crespigny, 2015

[52] De Crespigny, 2015

[53] De Crespigny, 2015

[54] De Crespigny, 2015

[55] De Crespigny, 2015

[56] De Crespigny, 2015

[57] De Crespigny, 2015

[58] De Crespigny, 2015, p. 131

[59] De Crespigny, 2015

[60] De Crespigny, 2015

[61] De Crespigny, 2015

[62] iMedia, n.d., “The three empresses of Emperor Huan of the Han Dynasty: jealousy became mad and the end was bleak”

[63] iMedia, n.d., “The three empresses of Emperor Huan of the Han Dynasty: jealousy became mad and the end was bleak”

[64] iMedia, n.d., “Dou Miao: No mercy towards rivals in love, but indecision towards eunuchs and finally a bleak evening scene”

[65] iMedia, n.d., “Dou Miao: No mercy towards rivals in love, but indecision towards eunuchs and finally a bleak evening scene”

[66] iMedia, n.d., “Dou Miao: No mercy towards rivals in love, but indecision towards eunuchs and finally a bleak evening scene”

[67] iMedia, n.d., “Dou Miao: No mercy towards rivals in love, but indecision towards eunuchs and finally a bleak evening scene”

[68] iMedia, n.d., “Dou Miao: No mercy towards rivals in love, but indecision towards eunuchs and finally a bleak evening scene”

The post Empress Dowager Dou Miao – The indecisive Regent appeared first on History of Royal Women.

August 4, 2024

A tradition of abdication – Luxembourg & The Netherlands

Luxembourg and the Netherlands both have a tradition of abdication, which can perhaps be explained by the fact that they were once in personal union. As the first steps have been made by Grand Duke Henri of Luxembourg to abdicate, take a look at the history of abdication in the two nations.

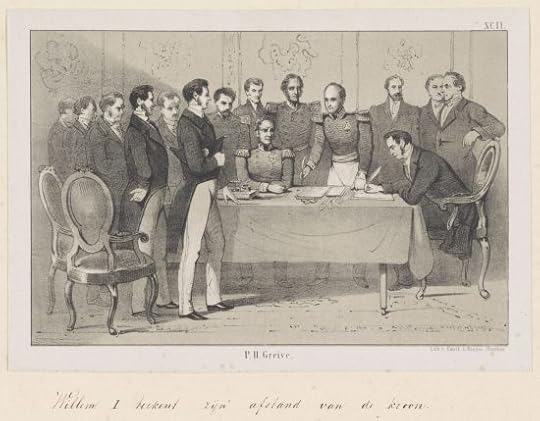

From 1815, King William I of the Netherlands was also Grand Duke of Luxembourg. He also became the first to abdicate in 1840, following the disappointment of the loss of Belgium and his intention to marry his late wife’s lady-in-waiting, Henriette d’Oultremont. Officially, his reasons for abdication were the changes to the constitution that limited the monarch’s powers, and they may have played a role as well. On 7 October 1840, King William I officially abdicated in favour of his eldest son, who became King William II of the Netherlands and Grand Duke of Luxembourg.

Abdication of King William I (RP-P-OB-88.675 – Public domain via Rijksmuseum)

Abdication of King William I (RP-P-OB-88.675 – Public domain via Rijksmuseum)The former King later wrote to Henriette, “Everything went very well yesterday. What had to be done was done in an appropriate manner. […] Public life has given way to private life, and the son is now charged with the duties that have rested on the father for so many years. May God help my son. May He bless him and grant him all that is necessary to fulfil the difficult and important task that rests on him with honour and for the happiness and satisfaction of all. You will certainly say, my dearest friend: Amen.”1

King William II reigned from 1840 until his death from illness in 1849. He was succeeded as King and Grand Duke by his eldest son, now King William III. He had been reluctant to accept his new position as he loathed the constitutional changes in 1848 that his father had agreed to, and he said he couldn’t possibly govern that way. Apparently, it took quite a bit of persuading from his mother for him to accept becoming King. William III had three sons by his first wife, Sophie of Württemberg, but all three predeceased him. Following Sophie’s death, he remarried the much younger Emma of Waldeck and Pyrmont, who became the mother of his eventual heir, Queen Wilhelmina. As William left no son, Wilhelmina succeeded him in the Netherlands. However, in Luxembourg, there was a family pact that mandated male-only succession.

Thus, King William III was succeeded as Grand Duke of Luxembourg by a distant family member, Adolphe, Duke of Nassau. He reigned from 1890 until his death in 1905 and was succeeded by his eldest son, William IV, Grand Duke of Luxembourg. He would be the last male member of the Nassau, and he and his wife had six daughters. According to the family pact, “a daughter, and if there are several, the first-born, or in her absence, the next heir of the last male line, to the exclusion of all other more distant ones, should be called to succeed.” 2 William confirmed his eldest daughter, Marie-Adélaïde, as his heir and she succeeded him, briefly under the regency of her mother, in 1912.

Marie-Adélaïde reigned throughout the First World War, but her perceived support of the German occupiers led to great unpopularity. On the parliament’s advice, Marie-Adélaïde abdicated the throne in favour of her eldest sister, Charlotte, on 14 January 1919. She had written in October 1918, “In any new arrangements necessitated by the probable end of war, there is no need to show consideration for my person; I am contemplating abdication. For the future of the Luxembourg dynasty, the securing of heirs is an essential condition. I shall never marry. My sister Charlotte has entered into an engagement with her cousin Prince Felix of Bourbon-Parma. An early marriage is desirable.” 3

Following her abdication, she wrote, “By virtue of the report submitted to me by the Government concerning the conference recently held in Paris between them and the Minister for Foreign Affairs. I have decided to renounce the crown of the Grand Duchy. In the fulfilment of my duties, I have always been animated by love for my country and by the desire to further its material and spiritual welfare. I wish to spare the Luxembourg people any difficulties which might hinder the Government in the adjustment of the economic future of the country with the neighbouring nations.” 4 Following a referendum, Charlotte regained the love of the people and reigned until her own abdication in 1964. Marie-Adélaïde died of influenza in 1924.

Meanwhile, in the Netherlands, a young Queen Wilhelmina had grown up and reigned independently since her 18th birthday. She led the neutral Netherlands through the First World War but was forced to make her way to England when the Second World War broke out. Queen Wilhelmina’s decision to abdicate certainly caused some raised eyebrows with her British cousins, who had been left reeling by the abdication of King Edward VIII in 1936. When the future Queen Elizabeth II dedicated her entire life to her people at the age of 21, Queen Wilhelmina commented, “She has definitely settled better to the inevitable than me and has raised herself higher above it.”5

Embed from Getty ImagesIn her memoirs, Wilhelmina wrote, “It was only after the period of transition following the liberation that I felt justified in seriously considering the question of abdication. An incentive was provided by my daily duties, which were more numerous than before the war and left my spirit little or no time for relaxation, which did not help my fitness at moments when special demands were made of me.” 6 On 12 May 1948, Wilhelmina announced her intention to abdicate in a speech on the radio. The date had some significance as the date of her father’s inauguration 99 years earlier. On 31 August 1948, a grand celebration took place in the Olympic Stadium of Amsterdam where she spoke the words, “I have fought the good fight.” 7 She would officially abdicate on 4 September 1948, 50 years and four days since the start of her personal reign. The new Queen was her only surviving child, now Queen Juliana.

Queen Juliana reigned from 1948 until her abdication in 1980, even though she had dreaded becoming Queen. The day before her official abdication, Juliana looked back on her reign with the words, “Life is beautiful but hard.” 8 The following day, Juliana signed her abdication, and her eldest daughter became Queen Beatrix. Like her mother before her, Juliana returned to using the style and title of Her Royal Highness Princess Juliana.

Embed from Getty ImagesOver in Luxembourg, Charlotte reportedly felt her age when she expressed her desire to abdicate in favour of her eldest son.9 She passed some duties to Jean in 1961 before fully abdicating in 1964 at the age of 68. With the solemn words, “We, Charlotte, by the grace of God, Grand Duchess of Luxembourg and Duchess of Nassau, proclaim that we are renouncing the crown of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg in favour of our beloved son, the Crown Prince (sic) Jean.” She cited the length of her reign and “the limit that wisdom imposes to any human activity.” 10

In the Netherlands, Queen Beatrix reigned from 1980 until her abdication in 2013. According to the official website, she was convinced that the responsibility for the country should now go to a new generation. She also thanked everyone for the trust they had given her during the many beautiful years of her reign.11 She was succeeded by her eldest son, now King Willem-Alexander, who still reigns today.

Embed from Getty ImagesBack in Luxembourg, Grand Duke Jean reigned from 1964 until his abdication in 2000. He gave up some royal duties to his eldest son, Henri, in 1998 before completely abdicating in 2000. According to the official website, Prime Minister Jean-Claude Juncker told the retiring Grand Duke, “You are one of us, and you have never given us the impression that you are different from us. (…) We have been and remain proud of you.” 12

Embed from Getty ImagesGrand Duke Henri recently announced his intention to sign away some royal duties to his eldest son, Guillaume, thus paving the way for his abdication.

© SIP / Claude Piscitelli

© SIP / Claude PiscitelliThe reasons for the abdication in the Netherlands and Luxembourg started off as rather diverse, but in more recent times, it was more of a way of making way for a new generation to take over. Or as Queen Wilhelmina poignantly wrote in her memoirs, “When we entered, we found a somewhat subdued atmosphere, which was, however, soon improved by my happy and cheerful manner. How numerous were and are my reasons for gratitude, in the first place, my confidence in Juliana’s warm feelings for the people we both love so much and in her devotion to the task that was awaiting her and her ability which she had proved on various occasions. Then also the fact that my office was transferred to her during my lifetime and that I might have the opportunity to see something of her reign. Really, there was no room for sadness in my heart.” 13

The post A tradition of abdication – Luxembourg & The Netherlands appeared first on History of Royal Women.

August 3, 2024

Book News Week 32

Book News Week 32 – 5 August – 11 August 2024

Catherine, the Princess of Wales: A Biography of the Future Queen

Hardcover – 6 August 2024 (US)

The Women Who Ruled China: Buddhism, Multiculturalism, and Governance in the Sixth Century

Paperback – 6 August 2024 (US & UK)

The King’s Loot: The Greatest Royal Jewellery Heist in History

Hardcover – 8 August 2024 (UK)

The post Book News Week 32 appeared first on History of Royal Women.

August 2, 2024

The Year of Isabella I of Castile – The voyages of Christopher Columbus

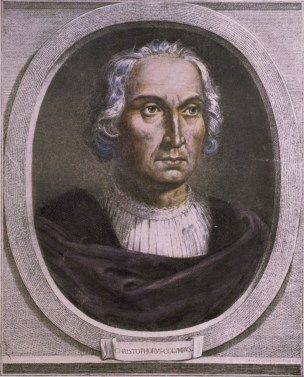

On 3 August 1492, Genoese explorer Christopher Columbus departed on the first of four voyages across the Atlantic Ocean to seek out new lands. For years, Columbus had petitioned the nobles and royals of Europe to gain funding for his ventures, before finally receiving backing from Queen Isabella I of Castile and King Ferdinand II of Aragon.

(public domain)

(public domain)Christopher Columbus was born sometime in 1451 to Domenico Colombo, a weaver and shopkeeper, and his wife Susanna Fontanarossa, who hailed from a wealthy Corsican family. The couple raised Christopher alongside his four siblings, Giovanni, Bartholomew, Giacomo and Bianchinetta.1 The family are said to have moved around the Ligurian Coast, settling in places such as Genoa and Savona where his father worked in the weaving trade or at his cheese stall. The young Christopher helped in the family businesses before heading out for a life at sea at fourteen.

Christopher Columbus had little formal schooling and was mostly self-taught. Due to the innovations in print at this time, Columbus and other laymen had access to materials previously out of their reach. Over time he learned a number of languages and studied extensively the topics of history, geography and astronomy.2 Columbus wished to be a part of this era of discovery from a young age.

In 1473, heading into his twenties, Columbus began working as an apprentice business agent for a number of wealthy Genoese families, allowing him to gain experience in travel and trade. In the 1470s, it is believed that Columbus visited England, Ireland and even Iceland before settling in Lisbon, Portugal, where he met up with his brother Bartholomew and began working with him for a family called the Centuriones. He spent a long period in Portugal, staying there until 1485. It was on a sugar-buying trip for the family that he met the twenty-five-year-old Filipa Moniz Perestrelo. The pair married in 1477 on the Portuguese island of Maderia. This marriage produced a son named Diego.3

During the 15th and 16th centuries, the royal and noble families of Europe began to sponsor voyages to discover unknown areas in the hope of providing their countries with wealth and new land. The Portuguese were some of the earliest to do this, and Columbus began to come up with plans for his own voyages. He wished to reach China by sailing west from Europe and through the Northwest Passage which had not been discovered by this point.

In order to fund such a trip, Christopher Columbus had to secure the backing of a wealthy benefactor and began approaching royal courts to pitch his plans. In 1484, Columbus approached King John II of Portugal, who would not offer support. The Portuguese stated that Columbus was greatly underestimating the distance he would need to travel to reach Asia by heading west (they were correct!).

After the death of his wife and the rejection of the King of Portugal, Columbus relocated to Castile. Here, he began a relationship with a woman named Beatriz Enriquez de Arana, and the couple had a son named Ferdinand.4 Columbus had gone to Castile to seek funding from the Catholic Monarchs, Isabella I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon. His plans were again rebuffed when he met them in 1486, but the monarchs wished to keep Columbus around so that he could not take these ideas elsewhere. He was paid a salary and encouraged to stay on in Castile. His brother Bartholemew had already been sent to England to try to gain funding from King Henry VII but was instead captured by pirates and held in captivity for years. Even when Bartholemew was released the brothers’ plans were again rejected.

By 1491, Ferdinand and Isabella agreed to open discussions again with Columbus. In January 1492, Columbus met with a group of councillors who, as before, rejected his plans because they seemed unrealistic. Feeling defeated, Columbus left for France. Once the explorer had left, King Ferdinand had a change of heart and sent the Queen’s bishop and confessor to plead with her to back the plans. If they did not support Columbus, somebody else would. Isabella finally relented and Columbus was halted as he reached Córdoba. Columbus signed an agreement with Ferdinand and Isabella called The Capitulations of Santa Fe. This stated that if he succeeded, he would receive 10% of the revenue of any discovered lands as well as a range of titles, including those of the Admiral of the Ocean Sea as well as Viceroy and Governor of any founded land.

Ferdinand and Isabella (public domain)

Ferdinand and Isabella (public domain)On 3 August 1492, Christopher Columbus finally set sail from Andalusia with three ships: the Santa Maria, the Niña and the Pinta. The fleet was setting off to discover the riches of India and China, and after sixty-one days, they reached land. Columbus believed he had reached India and incorrectly named the indigenous people “Indians.” He had, in fact, made it to what we now know as The Bahamas, first reaching the island of San Salvador, meaning Holy Saviour. The island was known by the native people as Guanahani. Columbus described the local population in his journal and his plans to bring them into servitude and convert them to Catholicism.5

While on the islands, Columbus searched for precious metals and spices and found very little. He traded with native peoples and took some of them into captivity, not seeing them as equals or even as a threat. He wrote in his journal, “With fifty men, we could subjugate them all and make them do whatever we want.”6 He also wrote extensively about the animals and plant life he discovered.

After exploring other areas and leaving men to create settlements in what we now know as the Dominican Republic and Haiti, Columbus set off on his return to Spain in January 1493. News had spread of his successful voyage and Christopher Columbus returned to Spain as a hero. He met with Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand in Barcelona, where he presented them with goods and plants that he had gathered and news of the new lands.

Christopher Columbus went on to make three further voyages to the “New World” on behalf of Spain. These voyages and his subsequent settlement of areas of the Caribbean, North, and South America changed the world forever. His four voyages provided more than his Spanish benefactors could have imagined, as they were able to conquer the Americas and spread Spanish culture, language, and, of course, Catholicism due to his hard work and perseverance.

The voyages of Christopher Columbus – CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

The voyages of Christopher Columbus – CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia CommonsWhile many still celebrate his extensive achievements, even hosting annual parades and holidays in his honour, we now also have the benefit of hindsight and can understand why others see him in a very different light. We can now look back and see the damage caused to native populations by European explorers. Brutal leadership, war, disease and widescale enslavement decimated native peoples, and in most areas, these populations never recovered.7 While it is important to look back at Columbus’ navigational achievements and celebrate the new medicines, foods and minerals brought over to Europe on his voyages, these horrific consequences of European greed cannot be ignored.8

Sources

Columbus, C., First Voyage to America: from the log of the “Santa Maria”

Winsor, J., Christopher Columbus and How He Received and Imparted the Spirit of Discovery

Tremlett, G., Isabella of Castile: Europe’s First Great Queen

Phillips, W.D., The Worlds of Cristopher Columbus

Brink, C., Christopher Columbus: Controversial Explorer of the Americas

https://www.britannica.com/biography/...

The post The Year of Isabella I of Castile – The voyages of Christopher Columbus appeared first on History of Royal Women.

August 1, 2024

Princess Andrew’s Meander Tiara

Princess Andrew’s Meander Tiara entered the British royal family through the mother of Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, Princess Alice of Battenberg. Through marriage, she became Princess Andrew of Greece and Denmark.

It is unclear when she acquired the tiara, but this likely happened after her marriage in 1903. The tiara consists of diamonds with a central laurel wreath element and two honeysuckle elements. The earliest photograph of Alice wearing the tiara was taken around 1914.1

Embed from Getty ImagesPrincess Alice gave the tiara to the then Princess Elizabeth in 1947 as a wedding gift when she married her son, Prince Philip. However, Elizabeth was never pictured wearing this tiara. It was first lent and then given to Princess Anne, and she has worn it regularly.

Embed from Getty ImagesMost notably, Princess Anne’s daughter, Zara, wore it for her 2011 wedding to Mike Tindall.

The post Princess Andrew’s Meander Tiara appeared first on History of Royal Women.

July 31, 2024

Book Review: Six Lives: The Stories of Henry VIII’s Queens

The lives of the six Queens of King Henry VIII of England have continued to fascinate us over 500 years later.

The National Portrait Gallery is running an exhibition called “Six Lives. The Stories of Henry VIII’s Queens”, and this wonderful hardcover book accompanies it. So, even if you can’t make it down to London, you can still enjoy some of the exhibition. You may recognise the names Suzannah Lipscomb, Nicola Clark, and Nicola Tallis as some of the contributors to this volume.

The book is divided into six main chapters dedicated to Katherine of Aragon, Anne Boleyn, Jane Seymour, Anne of Cleves, Katherine Howard and Katherine Parr. In these chapters, you’ll also find thematic pieces about music, jewels and ladies-in-waiting. It is a gorgeous book that will make an excellent addition to any bookcase.

And although I imagine it is not the same as seeing such an exhibition in person, it will certainly help soothe the pain of missing it.

Six Lives: The Stories of Henry VIII’s Queens is available now in the UK and will be released in the US on 20 August 2024.

The post Book Review: Six Lives: The Stories of Henry VIII’s Queens appeared first on History of Royal Women.

July 30, 2024

Empress Deng Mengnu – The deposed Empress who had three surnames

Empress Deng Mengnu was the second Empress of Emperor Huan of the Eastern Han Dynasty. She was the only Empress in China to have three surnames.[1] Empress Deng Mengnu was mostly known for her jealousy of other imperial concubines.[2] It was because of her jealousy and the fact that she was childless that caused her deposition as Empress of China.[3] Thus, Empress Deng Mengnu’s downfall was sudden and tragic.

In circa 140 C.E., Empress Deng Mengnu was born in Xinye, Nanyang.[4] Her personal name means “fierce woman.”[5] Her father was Deng Xiang. Her mother was Lady Xuan.[6] Deng Mengnu was the great-great-niece of Empress Dowager Deng Sui.[7] Deng Xiang died a few years after Deng Mengnu’s birth. Her mother, Lady Xuan, was remarried to Liang Ki.[8] Deng Mengnu changed her surname from Deng to Liang.[9]

In 153 C.E., Liang Mengnu entered Emperor Huan’s harem at the age of thirteen.[10] She was given the title of Lady of Elegance (the lowest rank in the harem).[11] Her beauty caught Emperor Huan’s eye.[12] She quickly became his favourite.[13] He promoted her to Worthy Lady (the highest rank below Empress).[14] Emperor Huan also promoted her brother, Deng Yan, as county Marquis in Nanyang.[15] Shortly after her promotion, her stepfather, Liang Ki, died.[16]

On 9 August 159 C.E., Empress Liang Nuying died. Empress Liang Nuying’s brother, Liang Ji, requested for Worthy Lady Liang Mengnu to be installed as the next Empress.[17] Emperor Huan agreed with Liang Ji’s proposal because he did not have any other favourites.[18] Liang Ji rebelled against Emperor Huan, but he was defeated and killed. Worthy Lady Liang Mengnu renounced her connection with the Liang family.[19]

On 14 September 159 C.E., Liang Mengnu was invested as Empress of China. Emperor Huan did not like her surname because it reminded him of Liang Ji.[20] He insisted that Liang Mengnu should adopt the surname Bo.[21] This was to remind the new Empress to follow the example of Grand Empress Dowager Bo.[22] In 161 C.E., Emperor Huan learned that Empress Bo Mengnu’s surname was originally Deng.[23] Therefore, he made her change her surname back to Deng.[24] Empress Deng Mengnu’s family received a lot of money and honours.[25] Her father, Deng Xiang, was posthumously promoted to Marquis.[26] Her mother, Lady Xuan, was given the title of Lady of Kunyang.[27] Thus, the Deng family became the most powerful family in court.[28]

Empress Deng Mengnu continued to be favoured by Emperor Huan.[29] However, she remained childless.[30] In order to beget a son and keep her husband’s favour, Empress Deng Mengnu developed the worship of the Huang-Lao.[31] Empress Deng Mengnu also tried various forms of fertility treatments, which were forbidden in the palace.[32] Yet, none of them worked. Emperor Huan gradually began to lose interest in her because she remained barren.[33] He expanded his harem to roughly 5,000 or 6,000 imperial concubines.[34]

Empress Deng Mengnu grew increasingly jealous of Emperor Huan’s favourite imperial concubines.[35] She began to worry that she would end up like Empress Liang Nuying, who was initially favoured by Emperor Huan but ended up losing his favour.[36] Empress Deng Mengnu became jealous of Consort Guo, one of Emperor Huan’s favourites.[37] She fought with her, cursed her, and slandered her.[38] She even tried to kill her using witchcraft.[39] Emperor Huan was angry at Empress Deng Mengnu’s behaviour.[40] He believed her behaviour was unfit for an Empress.[41]

On 27 March 165 C.E., Emperor Huan officially deposed Empress Deng Mengnu. He imprisoned her in the Drying House (a place of seclusion for imperial women who were no longer favoured).[42] Shortly after her imprisonment, the deposed Empress Deng Mengnu “died of worry.”[43] She was buried in Beimang.[44] Her family immediately lost power.[45] They were stripped of their property and honours.[46] Their positions were removed from court.[47] They were all arrested. Some of them died in prison.[48] The survivors were sent back to their home county in Nanyang.[49]

Empress Deng Mengnu was Empress for six years. The change of her surnames indicated the political turmoil during Emperor Huan’s reign.[50] Even though her jealousy contributed to her downfall, her greatest downfall was that she failed to produce any children.[51] This made Emperor Huan lose interest in her and made it easy to depose her.[52] Thus, Empress Deng Mengnu suffered a worse fate than her predecessor, Empress Liang Nuying.

Sources:

De Crespigny, R. (2015). “Deng Mengnu, Empress of Emperor Huan”. Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Women: Antiquity Through Sui, 1600 B.C.E. – 618 C.E. (L. X. H. Lee, Ed.; A. D. Stefanowska, Ed.; S. Wiles, Ed.). NY: Routledge. pp. 118-122.

iMedia. (n.d.). “The three empresses of Emperor Huan of the Han Dynasty: jealousy became mad and the end was bleak”. Retrieved on 20 October 2023 from https://min.news/en/news/578c75bfafea....

iNews. (n.d.). “How many times has Deng Mengnu’s surname changed? Why was she thrown into the cold palace by Emperor Huan of Han?”. Retrieved on 20 October 2023 from https://inf.news/en/news/9cc0f29a3275....

McMahon, K. (2013). Women Shall Not Rule: Imperial Wives and Concubines in China from Han to Liao. NY: Rowman and Littlefield.

[1] iNews, n.d., “How many times has Deng Mengnu’s surname changed? Why was she thrown into the cold palace by Emperor Huan of Han?”

[2] iMedia, n.d., “The three empresses of Emperor Huan of the Han Dynasty: jealousy became mad and the end was bleak”

[3] De Crespigny, 2015; McMahon, 2013

[4] De Crespigny, 2015; iMedia, n.d., “The three empresses of Emperor Huan of the Han Dynasty: jealousy became mad and the end was bleak”

[5] McMahon, 2013, p. 107

[6] De Crespigny, 2015

[7] De Crespigny, 2015

[8] De Crespigny, 2015

[9] iNews, n.d., “How many times has Deng Mengnu’s surname changed? Why was she thrown into the cold palace by Emperor Huan of Han?”

[10] De Crespigny, 2015

[11] De Crespigny, 2015

[12] De Crespigny, 2015

[13] De Crespigny, 2015

[14] De Crespigny, 2015

[15] De Crespigny, 2015

[16] De Crespigny, 2015

[17] De Crespigny, 2015

[18] De Crespigny, 2015

[19] De Crespigny, 2015

[20] iNews, n.d., “How many times has Deng Mengnu’s surname changed? Why was she thrown into the cold palace by Emperor Huan of Han?”

[21] iNews, n.d., “How many times has Deng Mengnu’s surname changed? Why was she thrown into the cold palace by Emperor Huan of Han?”

[22] De Crespigny, 2015

[23] iNews, n.d., “How many times has Deng Mengnu’s surname changed? Why was she thrown into the cold palace by Emperor Huan of Han?”

[24] iNews, n.d., “How many times has Deng Mengnu’s surname changed? Why was she thrown into the cold palace by Emperor Huan of Han?”

[25] De Crespigny, 2015

[26] De Crespigny, 2015

[27] De Crespigny, 2015

[28] De Crespigny, 2015

[29] De Crespigny, 2015

[30] De Crespigny, 2015

[31] De Crespigny, 2015

[32] De Crespigny, 2015

[33] De Crespigny, 2015

[34] McMahon, 2013

[35] iMedia, n.d., “The three empresses of Emperor Huan of the Han Dynasty: jealousy became mad and the end was bleak”

[36] iMedia, n.d., “The three empresses of Emperor Huan of the Han Dynasty: jealousy became mad and the end was bleak”

[37] iMedia, n.d., “The three empresses of Emperor Huan of the Han Dynasty: jealousy became mad and the end was bleak”

[38] iMedia, n.d., “The three empresses of Emperor Huan of the Han Dynasty: jealousy became mad and the end was bleak”

[39] De Crespigny, 2015

[40] iMedia, n.d., “The three empresses of Emperor Huan of the Han Dynasty: jealousy became mad and the end was bleak”

[41] McMahon, 2013

[42] De Crespigny, 2015

[43] McMahon, 2013, p. 107

[44] iMedia, n.d., “The three empresses of Emperor Huan of the Han Dynasty: jealousy became mad and the end was bleak”

[45] McMahon, 2013

[46] De Crespigny, 2015

[47] De Crespigny, 2015

[48] De Crespigny, 2015

[49] De Crespigny, 2015

[50] iNews, n.d., “How many times has Deng Mengnu’s surname changed? Why was she thrown into the cold palace by Emperor Huan of Han?”

[51] De Crespigny, 2015

[52] De Crespigny, 2015

The post appeared first on History of Royal Women.