Moniek Bloks's Blog, page 39

September 3, 2024

The Year of Isabella I of Castile – The peace treaty with Portugal

From the death of Queen Isabella’s half-brother, King Henry IV of Castile, she had been at war with Portugal.

King Henry IV left one daughter as heiress to the throne, but her legitimacy was questioned. She became known in history as Joanna La Beltraneja for her supposed father, Beltrán de la Cueva. Joanna was sworn in as heiress on 9 May 1462, with Isabella and her brother Alfonso being the first to swear.

However, it appears that several nobles already doubted Joanna’s legitimacy, not in the least because of jealousy towards Beltrán de la Cueva, who held the King’s favour. Isabella later wrote that she knew why some objected to swearing the oath. She wrote, “It was something she [the Queen] had demanded because she knew the truth about her pregnancy and was taking precautions.”1 Rumours about Beltrán de la Cueva being little Joanna’s biological father were beginning to circulate. It is impossible to tell if Joanna was Beltrán de la Cueva’s daughter, but we know Joan conceived again within the year. Tragically, she lost the child, a boy, at six months.

However, these rumours were the perfect fuel for a rebellion.

Joanna was just two years old when a manifesto of complaints and grievances was issued against King Henry by several nobles. This led to the Representation of Burgos in 1464, where Henry was forced to recognise Alfonso as the legitimate heir.2 This was agreed upon with the condition that Alfonso would one day marry Joanna. However, Henry soon reconsidered, and this led to a ceremonial deposition in effigy in 1465, and the 11-year-old Alfonso was crowned as rival King. Meanwhile, Isabella was still at court with Henry and Joan.

Isabella and Alfonso were reunited in 1467 when he triumphantly rode into Segovia as Queen Joan fled. Isabella asked to return to her mother at Arévalo, and at the end of the year, they celebrated Alfonso’s 14th birthday with the three of them. They stayed there until they were forced to flee due to an outbreak of the plague at the end of June 1468. Alfonso fell ill at Cardeñosa, and for four days, he fought for his life. His death was expected, and Isabella wrote, “And you all know that in the moment that the Lord decided to take his life, succession of the kingdoms and royal lands of Castile and Leon will, as his legitimate heiress and successor, pass to me.”3

Alfonso died on 5 July 1468. The battle was now between Joanna and Isabella.

Joanna’s father died on 11 December 1474, and her aunt Isabella successfully claimed the throne of Castile. It is not clear if Joanna and her mother were present when Henry died. After a few more marriage proposals, Joanna was married to her maternal uncle, King Afonso V of Portugal, on 29 May 1475. King Afonso invaded Castile to support Joanna’s claim shortly after their betrothal ceremony on 1 May. Shortly after her marriage, her mother, Joan, also died. Joanna was still only 13 years old, while her aunt was a mature married woman with a daughter of her own. Afonso did not consummate the marriage with his 13-year-old niece as he went to war.

Meanwhile, Joanna sent out letters to the cities and towns of Castile which read, “During his lifetime, he always wrote and swore, both in public and in private, to all those prelates and grandees who asked about it and to many other trustworthy people that he knew me to be his true daughter.”4 She also claimed that her father had named her as his heiress on his deathbed and that he had been poisoned by Isabella and her husband, Ferdinand. She called for Isabella to be punished, saying, “You must all rise and join, serving, helping and ensuring that this abominable, detestable action be punished.”5

The War of the Castilian succession would continue for four years. After the Battle of Toro in March 1476, Joanna and Afonso left Castile in June. However, troops remained stationed in Castile. Most of the time, Joanna was left in Portugal, and she often went long periods without seeing her husband. However, her exact whereabouts can not always be established.

They soon lost the support of Diego López de Pacheco, 2nd Duke of Escalona, and he “promised to serve them [Isabella and Ferdinand] in public and private from then on with complete faithfulness and loyalty, be it against the Portuguese King, his niece [Joanna], the French, their allies or anyone else.”6 Archbishop Carrillo also soon pledged his loyalty to Isabella. Another big blow came on 30 June 1478 when Isabella gave birth to a son named John. To some, the birth of a male heir was the proof that God had chosen Isabella as Queen.

It was Isabella’s aunt, Beatriz of Portugal, Duchess of Viseu (who was also King Afonso’s sister-in-law), who made the first approach for peace. Isabella agreed to meet her at the frontier town of Alcántara. They talked for three days, and Isabella insisted on Joanna being sent to a convent. She also refused to name Joanna as a Princess as “giving her that title is to confess that she is the daughter of a king and queen. And the queen [Isabella] thinks that… this in itself is sufficient reason to stop talking about peace.”7 Negotiations dragged on for another six months.

The peace treaty was signed in Alcáçovas (present-day Viana do Alentejo) on 4 September 1479. It was ratified by King Afonso on 8 September, followed by Queen Isabella I and King Ferdinand II on 6 March 1480. It became known as the Treaty of Alcáçovas-Toledo.

One chronicler wrote, “She, with no less grief than her own sadness and with painful lamentations of her own and of all her people, left the title of Queen and took the name of Doña Juana. She stripped her body of the brocades and silks she wore, and they dressed her in the brown habits of St Clare, taking from her the royal crown of Castile and Portugal, with which she was titled, and cutting her hair off like a poor maiden.”8

The post The Year of Isabella I of Castile – The peace treaty with Portugal appeared first on History of Royal Women.

September 1, 2024

Time in the Tower – Anne Boleyn

On May Day 1536, Anne Boleyn, Queen of England as the second wife of King Henry VIII, watched the jousts before her. She had given the King a daughter, the future Queen Elizabeth I, but no son. And now, her downfall was being plotted.

Her husband had been with her, but he reportedly suddenly departed. Had he perhaps already learned that the musician Mark Smeaton had been tortured into confessing adultery with Anne? In any case, Anne was arrested the following day. Mark Smeaton, Sir Henry Norris, and her brother George Boleyn were also arrested and were already in the Tower.

On 2 May, late in the afternoon, Anne was brought to the Tower of London. She arrived there around 5 in the afternoon by barge and entered through one of these gates, rather than the Traitor’s Gate as previously believed.

Photo by Moniek Bloks

Photo by Moniek BloksAnne fell to her knees as she reached the top of the steps and proclaimed her innocence. At this point, she only knew she had been accused of adultery with three men. She was then escorted into the Tower through the Byward postern gate and into the outer ward. She was informed that she would be housed in the royal apartments, where she had also stayed sometime before her coronation. Anne responded that they were too good for her and fell to her knees again. Sir William Kingston, the Constable of the Tower, was baffled by her behaviour, which was clearly one of shock.

This is the area where the Royal Apartments that Anne Boleyn would have known were. On the left is the White Tower – Photo by Moniek Bloks

This is the area where the Royal Apartments that Anne Boleyn would have known were. On the left is the White Tower – Photo by Moniek BloksFour women had been chosen to attend Anne, or rather spy on her. Anne continued to babble nervously even after Sir William retired for the evening. She mentioned two other men, Sir Francis Weston and Sir William Brereton, who were promptly arrested. Anne soon learned that her brother was also in the Tower, and she “made very good countenance.” 1

As the days passed, Anne’s mood swung from one extreme to the other. One moment, she was convinced she was being tested, and the next, she was convinced she would die. It would be impossible to speak to her husband in person, and there is a hotly debated letter that Anne may have sent Henry from the Tower on 6 May.

On 10 May, Anne, George, Sir Henry Norris, Sir Francis Weston, Sir William Brereton and Mark Smeaton were indicted. All but Anne and George were arraigned on 12 May at Westminster Hall. Anne and George were arraigned at the Tower on 15 May. Sir Henry Norris, Sir Francis Weston, Sir William Brereton and Mark Smeaton were arraigned for high treason and to no one’s surprise, they were all found guilty and sentenced to be executed at Tyburn.

Although Anne had not confessed to anything, her household was broken up on 13 May and her servants were discharged. On 14 May, Jane Seymour, who had supplanted Anne and would soon be Henry’s wife, was moved to a house close to Henry. As Anne prepared for her trial, Henry informed Jane that she would soon hear of Anne’s condemnation. The trial was to take place in the King’s Hall in the Tower, where special stands were erected for spectators.

Anne was brought it and sat in a chair provided for her as she listened to the indictment. She was accused of “despising her marriage and entertaining malice against the King.” 2 She was accused of committing adultery with Sir Henry Norris, Sir Francis Weston, Sir William Brereton and Mark Smeaton and incest with her brother George. She was also accused of plotting the death of the King with the men. Anne denied the charges, but the verdict was already set – she was found guilty of treason and condemned to death by burning or beheading. Anne remained calm, and according to the report of Ambassador Chapuys, “she was prepared to die, but was extremely sorry to hear that others, who were innocent and the king’s loyal subjects, should share her fate and die through her.” 3 She was then escorted back to the royal apartments as George faced his trial. He, too, was found guilty.

On 16 May, Sir William Kingston informed the men that they were to die the following day. During that day, Anne told him that she would go into a nunnery and was “in hope of life.” 4 The following day, Anne and Henry’s marriage was declared null and void. The five men were taken to the scaffold on Tower Hill as Henry had commuted their sentences to beheading.

The memorial on Tower Hill – Photo by Moniek Bloks

The memorial on Tower Hill – Photo by Moniek BloksAnne would not have been able to see the executions from the royal apartments. She began to prepare for her own execution, which she believed would be the following day. She spent most of the night in prayer with her almoner and took Mass with Sir William Kingston in the morning. He looked on as she took the Sacrament and swore she had never been unfaithful to the King. That same day, Henry issued a writ that Anne would not be burned but beheaded, and a swordsman had been ordered from Calais. He would not arrive that day, and Anne told Sir William Kingston, “I hear say I shall not die before noon, and I am very sorry, therefore, for I thought to be dead and past my pain.” 5 Sir William Kingston assured her there would be no pain to which she responded, “I heard say the executioner is very good, and I have a little neck.” 6

Anne would have to wait another day, and it wasn’t until the following morning that she was informed that her execution would take place imminently. The scaffold was erected on the north side of the Tower (a short walk from where the current memorial is).

Photo by Moniek Bloks

Photo by Moniek BloksShe distributed alms, and she spoke to the crowd from the scaffold with “a goodly smiling countenance.” 7 She said, “Good Christian people, I am come hither to die, for according to the law, and by the law, I am judged to die, and therefore I will speak nothing against it. I am come hither to accuse no man, nor to speak anything of that, whereof I am accused and condemned to die, but I pray God save the King and send him long to reign over you, for a gentler nor a more merciful prince was there never; and to me, he was ever a good, a gentle and sovereign lord. And if any person will meddle of my cause, I require them to judge the best. And thus, I take my leave of the world and of you all, and I heartily desire you all to pray for me. O Lord, have mercy on me; to God, I commend my soul.” 8

Her hair was tucked into a linen cap, and she was possibly blindfolded. It was over in seconds. Anne’s attendants covered her head and body with a white sheet and carried her to the St Peter ad Vincula.

The post Time in the Tower – Anne Boleyn appeared first on History of Royal Women.

August 31, 2024

Book News Week 36

Book News Week 36 – 2 September – 8 September 2024

[no image yet]

Izyaslav and Gertrude: The King and Queen of Rus’ at the Nexus of Medieval Europe (Harvard Papers in Ukrainian Studies)

Paperback – 3 September 2024 (US)

The post Book News Week 36 appeared first on History of Royal Women.

August 30, 2024

Empress Xiaoyichun – The third Empress of the Qianlong Emperor and mother of the Jiaqing Emperor

Empress Xiaoyichun was the third Empress of Emperor Qianlong of the Qing Dynasty. She was sixteen years younger than Emperor Qianlong.[1] While she was not appointed Empress during her lifetime, she was posthumously made an Empress because her son was Emperor Jiaqing of the Qing Dynasty.[2] Empress Xiaoyichun was originally a palace maid and became one of Emperor Qianlong’s favourites.[3] Within a span of a few short years, she rose up the ranks from a lowly-ranked concubine to a high-ranked Consort.[4] Thus, Empress Xiaoyichun enjoyed a life of wealth and privilege.

On 23 October 1727, Empress Xiaoyichun was born. Her personal name is unknown.[5] She was of Han descent, but her father had a Manchu name.[6] Her father was Wei Qingtai, a fifth-ranked official responsible for the inner court’s food and clothing.[7] Thus, they were from a middle-class family.[8] Her mother was Lady Yanggiya. She had two brothers.

It is unknown when Lady Wei entered the palace to become a palace maid.[9] She happened to catch Emperor Qianlong’s eye.[10] In 1745, she was given the title of Noble Lady.[11] On 9 December 1745, she was made an imperial concubine, and her name was changed to Ling.[12] On 20 May 1749, she was promoted to Consort Ling.[13] Therefore, within a span of four years, Consort Ling moved from a lowly concubine to a high-ranked Consort.[14] She still did not give him any children during her promotions.[15] After she was made Consort Ling, she gave birth to three sons named Prince Yonglu, Prince Yongyan (the future Emperor Jiaqing), and Prince Yonglin (who became Prince Qing of the First Rank).[16] She had an additional miscarriage, and she also gave birth to an unnamed son who died in infancy.[17] Consort Ling also bore two daughters named Princess Hejing and Princess Heke.[18] Thus, Consort Ling gave him six children within ten years of her promotion.

Consort Ling continued to have a loving relationship with Emperor Qianlong.[19] On 3 February 1760, she was given the title of Noble Consort Ling.[20] Emperor Qianlong wrote several poems for her.[21] She even accompanied him on his Southern tours in China.[22] On a certain tour, Emperor Qianlong sent his second Empress, Ulanara, back to the Forbidden City because of her erratic behaviour.[23] After Empress Ulanara died, Noble Consort Ling was promoted to Imperial Noble Consort. She managed the affairs of the six palaces.[24] This made her the second most powerful woman in China after Empress Xiaoshengxian.[25] Emperor Qianlong did not make her Empress in her lifetime.[26]

On 9 February 1775, Imperial Noble Consort’s eldest daughter, Princess Heijing, died. Imperial Noble Consort Ling fell ill after her daughter’s death. On 28 February 1775, Imperial Noble Consort Ling died at the age of forty-seven. She was buried next to Emperor Qianlong in Yu Mausoleum at the Eastern Qing Tombs.[27] She was posthumously elevated to the rank of Empress.[28] Her posthumous name was Empress Xiaoyichun. Her son, Prince Yongyan, ascended the throne as Emperor Jiaqing in 1796.[29]

In 1928, the Yu Mausoleum was destroyed and ransacked.[30] Emperor Puyi sent someone to clean up the tomb.[31] The person who discovered Empress Xiaoyichun’s body found that it was very well preserved and had not decomposed.[32] This has puzzled experts for decades.[33] Recently, experts have finally discovered the reason.[34] They found a lot of cinnabar in her body.[35] Cinnabar was often used as a sleep medicine.[36] Empress Xiaoyichun must have been using cinnabar as a sleep medication before she died.[37] Thus, experts have discovered that it was cinnabar that ultimately killed her.[38]

Empress Xiaoyichun was truly a remarkable woman. She was able to climb the ranks very quickly.[39] She bore him six children within ten years.[40] She was the most powerful woman in China after Empress Xiaoshengxian.[41] Her son became the next Emperor. Thus, she continued to have Emperor Qianlong’s love and respect for twenty years.[42] Empress Xiaoyichun is played by Wu Jingyan in the popular Chinese drama, Story of Yanxi Palace. She is also portrayed by Chun Li in the highly acclaimed Chinese drama, Ruyi’s Royal Love in the Palace.

Sources:

iMedia. (n.d.). “Did Qianlong really love Consort Ling in history?”. Retrieved on 23 October 2023 from https://inf.news/en/history/d9749c0fd....

iNews. (n.d.). “Consort Ling gave birth to 6 children in a row for ten years. After 100 years, her body was dug up, and people knew her true cause of death.”. Retrieved on 23 October 2023 from https://inf.news/ne/history/873a50e43....

iNews. (n.d.). “How did Consort Ling die? 153 years later, the concubine’s bones revealed the real cause of death”. Retrieved on 23 October 2023 from https://inf.news/en/history/d03f222cb....

iNews. (n.d.). “What’s so good about Consort Ling, which has been favoured by Qianlong for 20 years”. Retrieved on 23 October 2023 from https://inf.news/en/history/d9749c0fd....

Shanpu, Yu, et al. “Empress Ula Nara.” Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Women: v. 1: The Qing Period, 1644-1911. (L. X. H. L., et al., Ed.) Routledge, 2015, pp. 356–358.

Song, G. (2022). Televising Chineseness: Gender, Nation, and Subjectivity. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press.

[1] iMedia, n.d., “Did Qianlong really love Consort Ling in history?”

[2] iMedia, n.d., “Did Qianlong really love Consort Ling in history?”

[3] iMedia, n.d., “Did Qianlong really love Consort Ling in history?”

[4] iNews, n.d., “What’s so good about Consort Ling, which has been favoured by Qianlong for 20 years”

[5] iNews, n.d., “What’s so good about Consort Ling, which has been favoured by Qianlong for 20 years”

[6] Song, 2022

[7] iNews, n.d., “Consort Ling gave birth to 6 children in a row for ten years. After 100 years, her body was dug up, and people knew her true cause of death.”

[8] iNews, n.d., “Consort Ling gave birth to 6 children in a row for ten years. After 100 years, her body was dug up, and people knew her true cause of death.”

[9] iNews, n.d., “What’s so good about Consort Ling, which has been favoured by Qianlong for 20 years”

[10] iNews, n.d., “What’s so good about Consort Ling, which has been favoured by Qianlong for 20 years”

[11] iMedia, n.d., “Did Qianlong really love Consort Ling in history?”

[12] iMedia, n.d., “Did Qianlong really love Consort Ling in history?”

[13] iMedia, n.d., “Did Qianlong really love Consort Ling in history?”

[14] iNews, n.d., “What’s so good about Consort Ling, which has been favoured by Qianlong for 20 years”

[15] iNews, n.d., “What’s so good about Consort Ling, which has been favoured by Qianlong for 20 years”

[16] iNews, n.d., “What’s so good about Consort Ling, which has been favoured by Qianlong for 20 years”

[17] iNews, n.d., “Consort Ling gave birth to 6 children in a row for ten years. After 100 years, her body was dug up, and people knew her true cause of death.”

[18] iNews, n.d., “Consort Ling gave birth to 6 children in a row for ten years. After 100 years, her body was dug up, and people knew her true cause of death.”

[19] iNews, n.d., “How did Consort Ling die? 153 years later, the concubine’s bones revealed the real cause of death.”

[20] iMedia, n.d., “Did Qianlong really love Consort Ling in history?”

[21] iNews, n.d., “How did Consort Ling die? 153 years later, the concubine’s bones revealed the real cause of death.”

[22] Shanpu, et al, 2015

[23] Shanpu, et al, 2015

[24] iMedia, n.d., “Did Qianlong really love Consort Ling in history?”

[25] iMedia, n.d., “Did Qianlong really love Consort Ling in history?”

[26] iMedia, n.d., “Did Qianlong really love Consort Ling in history?”

[27] iMedia, n.d., “Did Qianlong really love Consort Ling in history?”

[28] iMedia, n.d., “Did Qianlong really love Consort Ling in history?”

[29] iMedia, n.d., “Did Qianlong really love Consort Ling in history?”

[30] iNews, n.d., “How did Consort Ling die? 153 years later, the concubine’s bones revealed the real cause of death.”

[31] iNews, n.d., “How did Consort Ling die? 153 years later, the concubine’s bones revealed the real cause of death.”

[32] iNews, n.d., “How did Consort Ling die? 153 years later, the concubine’s bones revealed the real cause of death.”

[33] iNews, n.d., “How did Consort Ling die? 153 years later, the concubine’s bones revealed the real cause of death.”

[34] iNews, n.d., “How did Consort Ling die? 153 years later, the concubine’s bones revealed the real cause of death.”

[35] iNews, n.d., “How did Consort Ling die? 153 years later, the concubine’s bones revealed the real cause of death.”

[36] iNews, n.d., “How did Consort Ling die? 153 years later, the concubine’s bones revealed the real cause of death.”

[37] iNews, n.d., “How did Consort Ling die? 153 years later, the concubine’s bones revealed the real cause of death.”

[38] iNews, n.d., “How did Consort Ling die? 153 years later, the concubine’s bones revealed the real cause of death.”

[39] iNews, n.d., “What’s so good about Consort Ling, which has been favoured by Qianlong for 20 years”

[40] iNews, n.d., “What’s so good about Consort Ling, which has been favoured by Qianlong for 20 years”

[41] iMedia, n.d., “Did Qianlong really love Consort Ling in history?”

[42] iNews, n.d., “What’s so good about Consort Ling, which has been favoured by Qianlong for 20 years”

The post Empress Xiaoyichun – The third Empress of the Qianlong Emperor and mother of the Jiaqing Emperor appeared first on History of Royal Women.

August 29, 2024

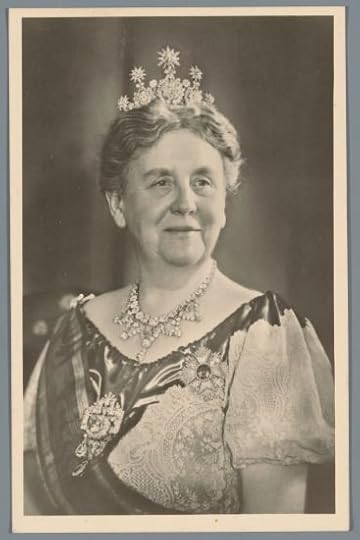

Queen Emma’s Diamond Tiara

Queen Emma’s Diamond Tiara was made for Emma of Waldeck and Pyrmont and gifted by her husband, King William III of the Netherlands to her in 1890. However, it arrived shortly after his death.

RP-F-F21027 via Rijksmuseum (public domain)

RP-F-F21027 via Rijksmuseum (public domain)It was made by Royal Begeer and features a trio of harp designs with diamond rosette-style clusters made from silver and gold. She often wore it topped with diamond stars from her own collection, for example, to her daughter’s wedding in 1901.

The tiara was a favourite of Princess Beatrix, and she is shown wearing it in the famous Warhol portrait.

Photo by Moniek Bloks

Photo by Moniek BloksThe centre of the rosette can be swapped for a ruby, and Princess Laurentien wore it in this setting for Crown Princess Victoria of Sweden’s wedding in 2010.

Embed from Getty ImagesOf course, Queen Maxima has also worn this piece, such as in New Zealand in 2016.1

Embed from Getty ImagesThe post Queen Emma’s Diamond Tiara appeared first on History of Royal Women.

August 27, 2024

Empress Xu – The deposed Empress who was blamed for causing a total solar eclipse because of her childlessness

Empress Xu was the first Empress of Emperor Cheng of the Western Han Dynasty. She initially had Emperor Cheng’s love.[1] However, she did not produce a son and was blamed for natural disasters that occurred frequently throughout the empire.[2] Her husband eventually saw her as a great calamity because of her barrenness and no longer loved her.[3] Empress Xu’s life is tragic because she did not make any mistakes as Empress.[4] Instead, she was vulnerable and a scapegoat because she was infertile.[5] Therefore, Empress Xu’s childlessness made her a victim of political intrigue.[6]

Empress Xu was from Shanyang (modern-day Shandong Province).[7] Her father was Xu Jia, the Marquis of Ping’en, who had once served as Commander-in-Chief during Emperor Xuan’s reign.[8] Empress Xu was the niece of Emperor Xuan’s first Empress, Xu Pingjun.[9] Emperor Yuan often grieved over the loss of his mother, Empress Xu Pingjun.[10] He wanted to keep his mother’s family prosperous.[11] Thus, he wanted someone from the Xu family to be the next Empress.[12] He chose Lady Xu to marry his Crown Prince.[13]

Lady Xu married the Crown Prince named Liu Ao. Lady Xu became Crown Princess. Crown Prince Liu Ao deeply loved his wife.[14] Crown Princess Xu quickly bore him a son, but the son died at birth.[15] On 8 July 33 B.C.E., Emperor Yuan died. On 4 August 33 B.C.E., Crown Prince Liu Ao ascended the throne of China as Emperor Cheng. On 13 May 31 B.C.E., Lady Xu was invested as Empress. She gave birth to a daughter, but she died shortly afterwards.[16] Empress Xu would remain childless.[17]

Empress Xu was known to be intelligent and virtuous, and she was educated in literature and history.[18] These were some of the reasons why she had Emperor Cheng’s love.[19] However, his mother, Empress Dowager Wang Zhengjun, constantly criticised Empress Xu about the lack of a male heir.[20] Whenever natural disasters occurred throughout the empire, high-ranked officials blamed Empress Xu for causing these disasters.[21] Empress Xu’s barrenness was seen as a great calamity.[22] Emperor Cheng also started to believe that Empress Xu was the cause of these disasters.[23] In 28 B.C.E., Emperor Cheng cut Empress Xu’s palace expenses.[24] Empress Xu submitted a memorial protesting the cut of her expenses but was rejected. [25]

One day, a total solar eclipse occurred. The ministers originally blamed Wang Feng because he held absolute power in court as Emperor Cheng’s uncle.[26] However, Wang Feng placed the blame for the eclipse on Empress Xu because of her barrenness.[27] Everyone in court, including Emperor Cheng, then blamed her for the eclipse.[28] Emperor Cheng no longer loved Empress Xu because he saw her barrenness as a calamity.[29] Instead, he transferred his affections to other palace women.[30] One of his favourites was Imperial Consort Ban Jieyu.

In 18 B.C.E., two of Emperor Cheng’s favorite Imperial Consorts named Zhao Feiyan (who would be Emperor Cheng’s second Empress) and Zhao Hede, accused Empress Xu and Imperial Consort Ban Jieyu of having an illicit affair with each other.[31] Imperial Consort Ban Jieyu, Empress Xu and her sister, Xu Ye, were charged with practising witchcraft to harm both Wang Feng and Imperial Consort Wang Meiren, who was pregnant with Emperor Cheng’s child.[32] When Empress Dowager Wang Zhengjun heard these accusations, she was outraged.[33] She ordered an investigation. Imperial Consort Ban Jieyu lost her imperial position and moved into Empress Dowager Wang Zhengjun’s side palace.[34]

On 8 January 17 B.C.E., Empress Xu was deposed. She was sent to Zhaotai Palace.[35] Her relatives were sent to Shanyang.[36] Her sister, Xu Ye, was executed.[37] Her nephew, who was the new Marquis of Ping’en, returned to his fiefdom.[38] In 16 B.C.E., Zhao Feiyan was invested as Emperor Cheng’s second Empress.

In 10 B.C.E., Emperor Cheng pardoned the deposed Empress Xu’s relatives and gave them permission to return to the capital.[39] The deposed Empress Xu’s sister, Xu Mi, wanted her sister to become the Empress again.[40] Xu Mi was a young and attractive widow.[41] She had an affair with Chunyu Chang, the nephew of Empress Dowager Wang Zhengjun.[42] Chunyu Chang was very close to Emperor Cheng and Empress Dowager Wang Zhengjun.[43] He also helped make Zhao Feiyan the Empress.[44] Therefore, Xu Mi hoped that he could help the deposed Empress Xu regain her former position.[45] Chunyu Chang promised her that he could make her sister a secondary Empress (which was a step below Empress Zhao Feiyan).[46] When the deposed Empress Xu learned of Chunyu Chang’s promise, she bribed him to help make her a secondary Empress.[47] They began to exchange letters.[48]

In 8 B.C.E., Wang Mang discovered the letters that were exchanged between Chunyu Chang and the deposed Empress Xu.[49] He sent them to Emperor Cheng.[50] Some of these letters were very provocative, which led Emperor Cheng to believe that the deposed Empress Xu was having an affair with Chunyu Chang.[51] Emperor Cheng was so outraged that his deposed Empress was cheating on him that he arrested Chunyu Chang and had him executed.[52] Then, Emperor Cheng ordered the deposed Empress Xu to commit suicide by poison.[53] She was buried in Yanling.[54]

Empress Xu was truly a tragic figure. Her naïvety and trust in the wrong person led her to be accused of infidelity and lose her own life.[55] Yet, her greatest downfall was that she could not give the Emperor children.[56] She originally had the Emperor’s love, but he began to see her as a calamity because of her barrenness.[57] Her infertility made her lose her husband’s love and the Empress position.[58] It also made her a scapegoat for natural disasters.[59] If she had produced an heir, her ending would have been very different.[60]

Sources:

iMedia. (n.d.). “The owner of the harem of the Western Han Dynasty – Empress Xu of Emperor Cheng of the Han Dynasty (born in a famous family and given poisonous wine). Retrieved on 20 October 2023 from https://min.news/en/history/33b669cd5....

iNews. (n.d.). “Chunyu Chang only took three steps to capture the heart of Empress Xu? I didn’t expect to be dug my cousin Wang Mang”. Retrieved on 20 October 2023 from https://inf.news/ne/history/90ed970ec....

McMahon, K. (2013). Women Shall Not Rule: Imperial Wives and Concubines in China from Han to Liao. NY: Rowman and Littlefield.

Wu, J. (2015). “Xu, Empress of Emperor Cheng”. Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Women: Antiquity Through Sui, 1600 B.C.E. – 618 C.E. (L. X. H. Lee, Ed.; A. D. Stefanowska, Ed.; S. Wiles, Ed.). NY: Routledge. pp. 224-226.

[1] McMahon, 2013

[2] Wu, 2015

[3] Wu, 2015

[4] iNews, n.d., “Chunyu Chang only took three steps to capture the heart of Empress Xu? I didn’t expect to be dug my cousin Wang Mang”

[5] iNews, n.d., “Chunyu Chang only took three steps to capture the heart of Empress Xu? I didn’t expect to be dug my cousin Wang Mang”

[6] iNews, n.d., “Chunyu Chang only took three steps to capture the heart of Empress Xu? I didn’t expect to be dug my cousin Wang Mang”

[7] Wu, 2015

[8] Wu, 2015

[9] McMahon, 2013

[10] iNews, n.d., “Chunyu Chang only took three steps to capture the heart of Empress Xu? I didn’t expect to be dug my cousin Wang Mang”

[11] iNews, n.d., “Chunyu Chang only took three steps to capture the heart of Empress Xu? I didn’t expect to be dug my cousin Wang Mang”

[12] iNews, n.d., “Chunyu Chang only took three steps to capture the heart of Empress Xu? I didn’t expect to be dug my cousin Wang Mang”

[13] Wu, 2015

[14] McMahon, 2013

[15] Wu, 2015

[16] Wu, 2015

[17] Wu, 2015

[18] Wu, 2015

[19] Wu, 2015

[20] Wu, 2015

[21] Wu, 2015

[22] Wu, 2015

[23] Wu, 2015

[24] Wu, 2015

[25] Wu, 2015

[26] Wu, 2015

[27] Wu, 2015

[28] Wu, 2015

[29] Wu, 2015

[30] Wu, 2015

[31] Wu, 2015

[32] Wu, 2015

[33] Wu, 2015

[34] McMahon, 2013

[35] Wu, 2015

[36] Wu, 2015

[37] Wu, 2015

[38] Wu, 2015

[39] Wu, 2015

[40] Wu, 2015

[41] iNews, n.d., “Chunyu Chang only took three steps to capture the heart of Empress Xu? I didn’t expect to be dug my cousin Wang Mang”

[42] Wu, 2015

[43] Wu, 2015

[44] Wu, 2015

[45] Wu, 2015

[46] Wu, 2015

[47] Wu, 2015

[48] Wu, 2015

[49] iNews, n.d., “Chunyu Chang only took three steps to capture the heart of Empress Xu? I didn’t expect to be dug my cousin Wang Mang”

[50] iNews, n.d., “Chunyu Chang only took three steps to capture the heart of Empress Xu? I didn’t expect to be dug my cousin Wang Mang”

[51] iNews, n.d., “Chunyu Chang only took three steps to capture the heart of Empress Xu? I didn’t expect to be dug my cousin Wang Mang”

[52] iNews, n.d., “Chunyu Chang only took three steps to capture the heart of Empress Xu? I didn’t expect to be dug my cousin Wang Mang”

[53] Wu, 2015

[54] Wu, 2015

[55] iMedia, n.d., “The owner of the harem of the Western Han Dynasty – Empress Xu of Emperor Cheng of the Han Dynasty (born in a famous family and given poisonous wine)

[56] Wu, 2015

[57] Wu, 2015

[58] Wu, 2015

[59] Wu, 2015

[60] iMedia, n.d., “The owner of the harem of the Western Han Dynasty – Empress Xu of Emperor Cheng of the Han Dynasty (born in a famous family and given poisonous wine)

The post Empress Xu – The deposed Empress who was blamed for causing a total solar eclipse because of her childlessness appeared first on History of Royal Women.

August 25, 2024

Empress Wang of the Xin Dynasty- The first Empress of Emperor Wang Mang the Usurper who killed three of their own children for power

Empress Wang of the Xin Dynasty was one of China’s most miserable Empresses. She was the first Empress of Emperor Wang Mang of the Xin Dynasty. She bore Emperor Wang Mang four sons. Yet, Emperor Wang Mang killed three of them for the sake of power.[1] Emperor Wang Mang destroyed his own family to gain the throne of China and ultimately ruined his own newly created dynasty.[2]

The birthdate of Empress Wang of the Xin Dynasty is unknown. Her personal name is unknown.[3] She was the daughter of Wang Xian, the Marquis of Yichun. She married Wang Mang, the nephew of Empress Dowager Wang Zhengjun. Lady Wang bore Wang Mang four sons named Wang Yu, Wang Huo, Wang An, and Wang Lin.[4] She also bore a daughter, who was Lady Wang (who would later become Empress to Emperor Ping of the Western Han Dynasty).

In 16 B.C.E., Emperor Cheng gave Wang Mang the title Marquis of Xindu and later promoted him to Commander-in-Chief in 8 B.C.E.[5] This was the highest position in the government, and Wang Mang became the most powerful man in court.[6] In 7 B.C.E., Emperor Cheng died, and Emperor Ai ascended the throne. Wang Mang was often feuding with Emperor Ai’s grandmother, Empress Dowager Fu.[7] This led Wang Mang to resign from his position.[8] He lost power and was sent back to Xindu to live in retirement.[9]

In 5 B.C.E., Wang Mang’s second son, Wang Huo, killed a servant.[10] Wang Mang thought that this would ruin his reputation.[11] Wang Mang forced his son, Wang Huo, to commit suicide.[12] This act led Wang Mang to win many officials’ hearts.[13] They all saw it as a sacrifice that Wang Mang had to perform to appease the victim’s family.[14] This pressured Emperor Ai to recall Wang Mang back to the palace to serve Empress Dowager Wang Zhengjun.[15] Wang Mang had achieved his aim of regaining power by sacrificing his own son.[16] However, Lady Wang deeply mourned the loss of her second son.[17] She grieved for three years. Whenever she thought of him, her face was full of tears.[18]

In 1 B.C.E., Emperor Ai died, and Emperor Ping ascended the throne. Wang Zhengjun became Grand Empress Dowager and was made Regent. Wang Mang became Grand Empress Dowager Wang Zhengjun’s right-hand man.[19] Under the reign of Emperor Ping, Wang Mang enjoyed many privileges.[20] In 1 C.E., he was made Duke of Anhan.[21] Thus, Lady Wang was made Duchess of Anhan.

In 3 C.E., Wang Mang’s eldest son, Wang Yu, disapproved of his father’s tyranny.[22] He conspired with his half-brothers to overthrow his father.[23] When Wang Mang learned of the plot, he arrested Wang Yu and his pregnant wife named Lu Yan.[24] He ordered Wang Yu to commit suicide.[25] He waited until Lu Yan could give birth.[26] Then, he executed her and the child.[27] Duchess Wang deeply mourned the loss of her eldest son.[28] She cried so much over the deaths of both Wang Huo and Wang Yu that she became blind.[29]

In 4 C.E., Wang Mang married his daughter, Lady Wang, to Emperor Ping. Wang Mang was made Steward-Regulator of State (which was a higher status than Duke).[30] Duchess Wang was given the title of Lady of Evident Merit.[31] In 5 C.E., Emperor Ping died. Wang Mang installed a one-year-old named Liu Ying as Emperor.[32] Wang Mang became Regent.

In 9 C.E., Wang Mang usurped the throne of China and became Emperor.[33] He created the Xin Dynasty. Duchess Wang was invested as Empress of China. His third son, Prince Wang An, was mentally ill.[34] Therefore, Emperor Wang Mang made his youngest son, Wang Lin, the Crown Prince.[35] Emperor Wang Mang asked Crown Prince Wang Lin to take care of Empress Wang because she was blind.[36] Empress Wang was said to be very “humble and unostentatious.”[37] When Emperor Wang Mang’s mother fell ill, all the wives of the nobility came to the palace to visit her.[38] Empress Wang greeted them, and they mistook her for a servant because of her humble clothing.[39] When the wives of the nobility learned that she was the Empress, they were very astonished.[40]

Empress Wang died in January of 21 C.E. She was given the posthumous title of Empress Xiaomu.[41] She was buried in Yinian Tomb in Changshou Garden in Weiling (modern-day Xanyang in Shaanxi Province).[42] Empress Wang’s two remaining sons died that same year.[43] Prince Wang An died of natural causes.[44] Crown Prince Wang Lin had an affair with a woman named Yuan Bi, who was once favoured by Emperor Wang Mang.[45] Crown Prince Wang Lin conspired with her to kill his father.[46] When Emperor Wang Mang discovered the plot, he forced Crown Prince Wang Lin to commit suicide.[47] Her only daughter, Empress Wang of the Western Han Dynasty, would also commit suicide in 23 C.E.[48]

Empress Wang of the Xin Dynasty’s tale is truly tragic. She had four sons. However, her ruthless husband killed three of them.[49] Emperor Wang Mang’s ruthlessness left him with no remaining sons to carry on his own dynasty.[50] His love for power was more than his love for his family.[51] Emperor Wang Mang’s Xin Dynasty would fall in 23 C.E. After the Xin Dynasty ended, the Eastern Han Dynasty began. The Eastern Han Dynasty continued for almost two hundred years.

Sources:

iMedia. (n.d.). “She was Wang Mang’s queen, she gave birth to 5 children and 3 died at Wang Mang’s hands. Why?”. Retrieved on 20 October 2023 from https://min.news/en/history/4c43376d8....

iNews. (n.d.). “As the queen of Wang Mang, the founder of the new dynasty, what is her fate?” Retrieved on 20 October 2023 from https://inf.news/en/history/578a79d8d....

McMahon, K. (2013). Women Shall Not Rule: Imperial Wives and Concubines in China from Han to Liao. NY: Rowman and Littlefield.

Yang, H. (2015). “Wang, Empress of Wang Mang of Xin”. Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Women: Antiquity Through Sui, 1600 B.C.E. – 618 C.E. (L. X. H. Lee, Ed.; A. D. Stefanowska, Ed.; S. Wiles, Ed.). NY: Routledge. pp. 203-204.

[1] iNews, n.d., “As the queen of Wang Mang, the founder of the new dynasty, what is her fate?”

[2] iMedia, n.d., “She was Wang Mang’s queen, she gave birth to 5 children and 3 died at Wang Mang’s hands. Why?”

[3] Yang, 2015

[4] Yang, 2015

[5] Yang, 2015

[6] iNews, n.d., “As the queen of Wang Mang, the founder of the new dynasty, what is her fate?”

[7] iNews, n.d., “As the queen of Wang Mang, the founder of the new dynasty, what is her fate?”

[8] iNews, n.d., “As the queen of Wang Mang, the founder of the new dynasty, what is her fate?”

[9] iNews, n.d., “As the queen of Wang Mang, the founder of the new dynasty, what is her fate?”

[10] McMahon, 2013

[11] iNews, n.d., “As the queen of Wang Mang, the founder of the new dynasty, what is her fate?”

[12] iNews, n.d., “As the queen of Wang Mang, the founder of the new dynasty, what is her fate?”

[13] iNews, n.d., “As the queen of Wang Mang, the founder of the new dynasty, what is her fate?”

[14] iNews, n.d., “As the queen of Wang Mang, the founder of the new dynasty, what is her fate?”

[15] iNews, n.d., “As the queen of Wang Mang, the founder of the new dynasty, what is her fate?”

[16] iNews, n.d., “As the queen of Wang Mang, the founder of the new dynasty, what is her fate?”

[17] iNews, n.d., “As the queen of Wang Mang, the founder of the new dynasty, what is her fate?”

[18] iNews, n.d., “As the queen of Wang Mang, the founder of the new dynasty, what is her fate?”

[19] Yang, 2015

[20] Yang, 2015

[21] Yang, 2015

[22] McMahon, 2013

[23] iNews, n.d., “As the queen of Wang Mang, the founder of the new dynasty, what is her fate?”

[24] iNews, n.d., “As the queen of Wang Mang, the founder of the new dynasty, what is her fate?”

[25] McMahon, 2013

[26] iNews, n.d., “As the queen of Wang Mang, the founder of the new dynasty, what is her fate?”

[27] iNews, n.d., “As the queen of Wang Mang, the founder of the new dynasty, what is her fate?”

[28] iNews, n.d., “As the queen of Wang Mang, the founder of the new dynasty, what is her fate?”

[29] Yang, 2015

[30] Yang, 2015

[31] Yang, 2015

[32] Yang, 2015

[33] Yang, 2015

[34] iMedia, n.d., “She was Wang Mang’s queen, she gave birth to 5 children and 3 died at Wang Mang’s hands. Why?”

[35] iMedia, n.d., “She was Wang Mang’s queen, she gave birth to 5 children and 3 died at Wang Mang’s hands. Why?”

[36] Yang, 2015

[37] McMahon, 2013, p. 92

[38] Yang, 2015

[39] Yang, 2015

[40] Yang, 2015

[41] Yang, 2015

[42] Yang, 2015

[43] McMahon, 2013

[44] iMedia, n.d., “She was Wang Mang’s queen, she gave birth to 5 children and 3 died at Wang Mang’s hands. Why?”

[45] McMahon, 2013

[46] McMahon, 2013

[47] McMahon, 2013

[48] McMahon, 2013

[49] iMedia, n.d., “She was Wang Mang’s queen, she gave birth to 5 children and 3 died at Wang Mang’s hands. Why?”

[50] iMedia, n.d., “She was Wang Mang’s queen, she gave birth to 5 children and 3 died at Wang Mang’s hands. Why?”

[51] iMedia, n.d., “She was Wang Mang’s queen, she gave birth to 5 children and 3 died at Wang Mang’s hands. Why?”

The post Empress Wang of the Xin Dynasty- The first Empress of Emperor Wang Mang the Usurper who killed three of their own children for power appeared first on History of Royal Women.

August 24, 2024

Book News Week 35

Book News Week 35 – 26 August – 1 September 2024

The Two Eleanors of Henry III: The Lives of Eleanor of Provence and Eleanor de Montfort

Paperback –30 August 2024 (US & UK)

Stephen and Matilda’s Civil War: Cousins of Anarchy

Paperback – 30 August 2024 (US)

A Voyage Around the Queen

Kindle & Hardcover – 29 August 2024 (US & UK)

Courting the Virgin Queen: Queen Elizabeth I And Her Suitors

Hardcover – 30 August 2024 (US)

Planning the Murder of Anne Boleyn

Hardcover – 30 August 2024 (UK)

The Tragic Life of Lady Jane Grey

Hardcover – 30 August 2024 (UK)

Worlds of Byzantium: Religion, Culture, and Empire in the Medieval Near East

Hardcover – 31 August 2024 (US)

The post Book News Week 35 appeared first on History of Royal Women.

August 23, 2024

Grand Empress Dowager Qiongcheng – The unfavoured Empress who became a respected Empress Dowager

Grand Empress Dowager Qiongcheng was the third Empress of Emperor Xuan of the Western Han Dynasty. She was never favoured by Emperor Xuan. However, Grand Empress Dowager Qiongcheng established a close bond with Emperor Yuan. She would be highly regarded by two Emperors who would reward her for her virtue.

The birthdate of Grand Empress Dowager Qiongcheng is unknown. Her personal name is also unknown.[1] She was from Pei District in modern-day Jiangsu Province.[2] She was from the Wang family.[3] Her father was Wang Fengguang, the Marquis of Guannei.[4] Her father had developed a friendship with Prince Liu Xun through their love of cockfighting.[5] On 10 September 74 B.C.E., Prince Liu Xun ascended the throne of China as Emperor Xuan. Because of his friendship with her father, Emperor Xuan sent for Lady Wang to become his imperial concubine.[6] He gave her the rank of Jieyu (the second highest rank below the Empress position).[7] She was not favoured, and she remained childless.[8]

In 66 B.C.E., Empress Huo Chengjun was deposed for trying to assassinate Liu Shi, the Crown Prince whom he had with Empress Xu Pingjun.[9] The Empress position remained vacant.[10] Emperor Xuan was hesitant to appoint another Empress because he was afraid that she would try to kill the Crown Prince.[11] For three years, he did not appoint an Empress.[12] After much pressure from his ministers, Emperor Xuan considered possible candidates for the Empress position.[13] His three favourite imperial concubines all gave him sons.[14] This threatened Liu Shi’s position as Crown Prince.[15] Instead, he chose Consort Wang because she was childless and had a gentle disposition.[16] He believed that Consort Wang would be a suitable stepmother to Liu Shi.[17]

On 26 March 64 C.E., Consort Wang was invested as Empress of China. Her father was made Marquis of Qiongcheng.[18] Emperor Xuan gave Crown Prince Liu Shi to her to raise as her stepson.[19] Emperor Xuan still did not favour her.[20] She rarely saw him, and she remained childless.[21] On 10 January 48 B.C.E., Emperor Xuan died.

On 29 January 48 B.C.E., Liu Shi ascended the throne as Emperor Yuan. Emperor Yuan made Empress Wang the Empress Dowager.[22] When Emperor Yuan died, his son, Emperor Cheng, ascended the throne on 4 August 33 B.C.E. Emperor Cheng made her the Grand Empress Dowager Qiongcheng.[23] He chose Qiongcheng to distinguish her from his mother, Empress Dowager Wang Zhengjun.[24] Qiongcheng was the title of her father’s Marquisate.[25] On 22 September 16 B.C.E., Grand Empress Dowager Qiongcheng died. She was over seventy.[26] She was buried next to Emperor Xuan in the Eastern Mausoleum in present-day Chang’an District in Shaanxi Province.[27]

Even though very little information is known about her, it is clear that Grand Empress Dowager Qiongcheng was a remarkable Empress.[28] Three Emperors made her the Empress, Empress Dowager, and Grand Empress Dowager.[29] Even though she was not favoured and had no children of her own, she was given the greatest honour.[30] Unlike her predecessor, Empress Huo Chengjun, she established a close relationship with Emperor Yuan.[31] Emperor Yuan and Emperor Cheng deeply honoured and respected her.[32] Therefore, she was able to live a long life and received many privileges.[33] Grand Empress Dowager Qiongcheng proved to be a virtuous Empress.[34]

Sources:

Cutter, R. J. (1989). The Brush and The Spur: Chinese Culture and The Cockfight. Hong Kong: Chinese University Press.

Wang, X. (2015). “Wang, Empress of Emperor Xuan”. Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Women: Antiquity Through Sui, 1600 B.C.E. – 618 C.E. (L. X. H. Lee, Ed.; A. D. Stefanowska, Ed.; S. Wiles, Ed.). NY: Routledge. pp. 202-203.

[1] Wang, 2015

[2] Wang, 2015

[3] Cutter, 1989

[4] Wang, 2015 Cutter, 1989

[5] Cutter, 1989; Wang, 2015

[6] Cutter, 1989; Wang, 2015

[7] Wang, 2015

[8] Wang, 2015

[9] Wang, 2015

[10] Wang, 2015

[11] Wang, 2015

[12] Wang, 2015

[13] Wang, 2015

[14] Wang, 2015

[15] Wang, 2015

[16] Wang, 2015

[17] Wang, 2015

[18] Wang, 2015

[19] Wang, 2015

[20] Wang, 2015

[21] Wang, 2015

[22] Wang, 2015

[23] Wang, 2015

[24] Wang, 2015

[25] Wang, 2015

[26] Wang, 2015

[27] Wang, 2015

[28] Wang, 2015

[29] Wang, 2015

[30] Wang, 2015

[31] Wang, 2015

[32] Wang, 2015

[33] Wang, 2015

[34] Wang, 2015

The post Grand Empress Dowager Qiongcheng – The unfavoured Empress who became a respected Empress Dowager appeared first on History of Royal Women.

Margaret of Parma to be honoured with joyeus entry ahead of exhibition

Ahead of a new exhibition celebrating the life of Margaret of Parma, the city of Oudenaarde will honour her with a joyous entry.

This tradition stems from Margaret’s time and would be a welcome to the city by its inhabitants. Margaret will be represented by an actress in a historical spectacle with horses, musicians and flagbearers. The parade will begin at 3 pm on Sunday, 22 September.

The Museum Oudenaarde (MOU) will host the exhibition”Margaret of Parma – The Emperor’s Daughter between Power and Image from 23 September until 5 January 2025. Stefaan Vercamer, the alderman for Culture, said, “We reveal the life story of this strong woman and introduce you to this grande dame of the 16th century. The exhibition includes paintings and drawings, tapestries and miniatures, gold and silver work, stained glass windows and other personal objects belonging to Margaret. With many loans from museums all over the world, this exhibition has an international allure. On the very first day, we will provide many extras to welcome visitors, such as demonstrations and animations. It is a fascinating experience for young and old: for example, the MOU team has developed a game of snakes and ladders to take even the smallest Margaret fans through the exhibition.”

The exhibition will be accompanied by a publication.

Read more about the exhibition here.

The post Margaret of Parma to be honoured with joyeus entry ahead of exhibition appeared first on History of Royal Women.