Moniek Bloks's Blog, page 37

September 26, 2024

The Antique Pearl Tiara

The Antique Pearl Tiara was made in 1900 and was designed to mimic the shape of an older Pearl tiara in the Dutch collection once owned by Anna Pavlovna, wife of King William II of the Netherlands. It is not clear what happened to the older pearl tiara.

The large pearls sit upright on this tiara, and they used to belong to Amalia of Solms-Braunfels, Princess of Orange.

Embed from Getty ImagesQueen Wilhelmina was the first to wear this tiara and it has remained a favourite with the Dutch Queens and Princesses since. Queen Juliana placed the tiara in the family’s jewel foundation in 1962.

The tiara can also be worn without the pearls, which the future Queen Maxima did before her marriage to the then Prince of Orange, to the wedding of Crown Prince Haakon of Norway.1

Embed from Getty ImagesThe post The Antique Pearl Tiara appeared first on History of Royal Women.

September 24, 2024

Time in the Tower – Catherine Howard

Catherine Howard was born at an unknown date, probably in 1524, the daughter of Lord Edmund Howard, son of Thomas Howard, 2nd Duke of Norfolk, and Jocasta Culpeper. She was one of five children. Her mother probably died in 1527, as her father had remarried to Dorothy Troyes, but the marriage was probably short, and he married Margaret Jennings for a third time.

Catherine was sent to live in the household of her step-grandmother, the Dowager Duchess of Norfolk, Agnes (née Tilney), after the deaths of her stepmothers. Catherine was closely related to Henry VIII’s second and third Queens. Her father’s sister, Elizabeth, was the mother of Henry VIII’s second wife, Anne Boleyn. Her father’s first cousin, Margery Wentworth, was the mother of Henry’s third wife, Jane Seymour.

By 1536, Catherine was receiving music lessons from Henry Manox at the Dowager Duchess’s household. Musical talents were highly appreciated at court, and perhaps she was hoping for a place in Jane Seymour’s household. Henry Manox would later be accused of molesting Catherine during these years. She also became acquainted with Francis Dereham, who served in the Duke of Norfolk’s household. Catherine shared a chamber with other young women which young gentlemen often visited. Francis was one of these gentlemen, though there is little evidence to suggest she consented to his advances. As Queen, her tainted childhood would come back to haunt her.

After the death of Jane Seymour, Henry remarried Anne of Cleves on 6 January 1540, and Catherine was chosen to serve in the new Queen’s household. She was probably around 15 years old then. She probably travelled to Greenwich Palace in December 1539 in anticipation of Anne of Cleves’s arrival. Henry was disappointed with his new wife from the start and admitted after their wedding night, “I have left her as a good a maid as I found her.” Their marital issues were compounded by the fact that Henry had fallen in love with her maid, Catherine. It is possible that they met before Anne’s arrival, but we do not know this for sure.

By April, Catherine was granted forfeited goods of two murderers, and it became clear that the King intended to annul his marriage to Anne and marry Catherine. His infatuation with Catherine was an open secret. “This was first whispered by the courtiers, who observed the King to be much taken with another young lady of very diminutive stature, whom he now has. It is a certain fact, that about the same time many citizens of London saw the King very frequently in the day-time, and sometimes at midnight, pass over to her on the river Thames in a little boat. The Bishop of Winchester also very often provided feastings and entertainments for them in his palace, but the citizens regarded all this not as a sign of divorcing the Queen, but of adultery.”1 On 28 July 1540, Henry married Catherine shortly after his annulment.

Henry was rejuvenated by his new marriage to his “jewel”, but it was not to last long. Although Catherine certainly enjoyed the perks of being Queen, she was not in love with him. She was already in love with someone else at the time of her wedding. She had met Thomas Culpeper, a member of Henry’s privy chamber, shortly after arriving at court. They likely became lovers after her marriage, and Catherine’s only surviving letter is written to Thomas.

Catherine relied on Lady Rochford, who was the widow of George Boleyn, the brother of Anne Boleyn, to help her meet with Thomas in secret. It all came crashing to a halt when another of the Dowager Duchess’s household came forward and told her of Catherine’s past dealing with Dereham and Manox. Thomas Cranmer put it all in writing and passed it along to Henry, who was devastated and refused to believe it. However, he did order an investigation to be carried out. Henry Manox soon cracked under the pressure, and Catherine was arrested on 4 November 1541.

She was interrogated and confessed to her relationship with Manox and Dereham. Soon, her relationship with Thomas was revealed, which was perhaps even more dangerous than her previous affairs. On 14 November, she was sent to Syon House, where she was “kept in the estate of a Queen.”2 Nevertheless, her jewels were taken from her, and they removed “knives and all such things as wherewith she may hurt herself.”3

In her desperation, Catherine said that the only reason she had even spoken to Thomas Culpepper was because Lady Rochford had pushed her to it. Nevertheless, evidence was found that Catherine was a willing participant in the form of a letter. Catherin had written, “It makes my heart die to think I cannot be always in your company. Come when my Lady Rochford is here, for then I shall be best at leisure to be at your commandment.”4 The more Catherine talked, the more trouble she brought upon them.

Meanwhile, Lady Rochford was taken to the Tower of London. Lady Rochford was protected from torture, but she was interrogated and confessed that she had helped Catherine look out for him. She added, “Culpepper hath known the Queen carnally considering all things that this deponent hath heard and seen.”5

Following a trial on 1 December, both Dereham and Thomas were executed on 10 December 1541. For now, Catherine remained at Syon House as they had to await the opening of Parliament on 16 January. Catherine was not to be given a trial and was instead convicted by an Act of Attainder. On 21 January, the bill of attainder for high treason against both Catherine and Lady Rochford was introduced. Meanwhile, Catherine was still at Syon House “making good cheer”, even though she “expects death and only asks for a secret [private] execution.”6 The bill of attainder passed on 7 February 1542.

(public domain)

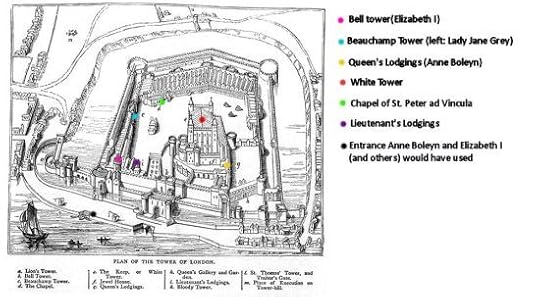

(public domain)On 10 February, Catherine was removed from Syon House and, “after some difficulty and resistance”, put into a barge to be taken to the Tower of London.7 Catherine “dressed in black velvet” entered the Tower of London through the sally door at Byward Tower. She entered the royal lodgings, which have not survived to this day. Following her arrival at the Tower, she “weeps, cries, and torments herself miserably, with ceasing.”8

The area of the former royal lodgings – Photo by Moniek Bloks

The area of the former royal lodgings – Photo by Moniek BloksOn 12 February in the evening, Catherine was informed “to dispose her soul and prepare for death, for she was to be beheaded the next day.”9 Catherine asked to see the block because “she wanted to know how she was to place her head on it.”10 Catherine then spoke of “the miscarriages of her former life, before the King married her: but stood absolutely to her denial, as to any thing after that. […] She took God and his angels to be her witnesses, upon salvation of her soul, that she was guiltless of that act of defiling her sovereign’s bed, for which she was condemned.”11

The memorial near the execution site – Photo by Moniek Bloks

The memorial near the execution site – Photo by Moniek BloksThe following morning, Catherine ate breakfast before she was dressed in a black velvet gown. Just before 9 o’clock, the Constable came to escort her. She walked through Coldharbour gate, passed the White Tower and arrived on Tower Green where the scaffold awaited her. Catherine climbed the wooden steps and spoke a few words. Several versions exist of her final words, but the French ambassador reported that Catherine was “so weak that she could hardly speak, but confessed in a few words that she merited a hundred deaths for so offending the King who had so graciously treated her.”12

Photo by Moniek Bloks

Photo by Moniek BloksHer ladies removed her hood and gloves and put her hair into a lined coif. They bound her eyes and then withdrew to the back. Catherine knelt and said her prayers and positioned herself as she had practised. Her head was struck off in a single stroke.

By VCR Giulio19 – CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

By VCR Giulio19 – CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia CommonsHer ladies then stepped forward again to cover her body with a black cloak and laid it to the side as Lady Rochford was escorted to the scaffold to also be executed. Their remains were carried to the Church of St Peter ad Vincula and buried beneath the altar.

The post Time in the Tower – Catherine Howard appeared first on History of Royal Women.

September 22, 2024

Empress Myeongseong the Great – Korea’s beloved Empress

Empress Myeongseong the Great has been known as one of Korea’s greatest Queens. She has been regarded as a national heroine.[1] She has been known for her reforms and her attempts to maintain Korean independence.[2] Empress Myeongseong the Great has often been praised for her “wisdom and insight”.[3] She has also been praised for being a talented and accomplished politician.[4]

On 17 November 1851, Empress Myeongseong the Great was born in Gyeonggi Province.[5] Her personal name was Min Ja-yeong.[6] Her father was Min Chi-rok (later known as Internal Prince Yeoseong).[7] Her mother was Lady Yi (later known as Internal Princess Consort Hanchang). Her aunt was Grand Internal Princess Consort Sunmok.[8] Her uncle was Grand Internal Prince Heungseon Daewongun (the Regent of Korea).[9] This meant that her future husband, King Gojong of Korea, was her first cousin.[10] Min Chi-rok died when Min Ja-yeong was eight years old.[11] She was raised by Lady Yi. She was said to be very intelligent.[12]

Grand Internal Princess Consort Sunmok wanted King Gojong’s bride to be someone from her own clan.[13] She chose Min Ja-yeong as the wife for her son.[14] Grand Internal Prince Heungseon Daewongun also agreed with his wife’s choice because Min Ja-yeong’s father had already passed away.[15] This meant that she had no living father who could influence King Gojong in court.[16] On 21 March 1866, Min Ja-yeong married King Gojong of Korea. She became Queen of Korea at the age of fourteen.[17]

Initially, King Gojong of Korea neglected Queen Min for his concubines.[18] She spent her lonely nights reading history, philosophy, religion, and politics.[19] King Gojong eventually recognized Queen Min’s intelligence.[20] He began to form a close relationship with her. He also relied heavily on her advice on political matters.[21] Five years after their marriage, Queen Min finally gave birth to an infant son.[22] However, he died four days later.[23]

Queen Min blamed her father-in-law, Grand Internal Prince Heungseon Daewongun, for her son’s death.[24] She believed he had poisoned her son through a ginseng emetic treatment.[25] She persuaded King Gojong to oust his father and his supporters.[26] On 5 November 1873, King Gojong removed his father as Regent and his supporters from court.[27] He ruled Korea in his own name.[28] He relied solely on Queen Min.[29] A week after King Gojong ruled in his own name, a mysterious explosion occurred in Queen Min’s chambers.[30] However, Queen Min and her attendants were not harmed.[31]

On 13 February 1873, Queen Min gave birth to an unnamed daughter who only lived for a few months. On 25 March 1874, she gave birth to a son named Yi Cheok (the future Emperor Sunjong).[32] However, he remained sickly throughout his life.[33] Queen Min began to promote her family members in high court positions.[34] She began to make reforms to modernize Korea.[35]

In 1876, Queen Min and King Gojong signed the Treaty of Ganghwa, which opened international trade between Korea and Japan.[36] She made many reforms in “economy, transportation, agriculture, education, and medicine.”[37] She also founded hospitals.[38] Even though she was a Buddhist, she allowed Christian missionaries in Korea.[39]

Queen Min distrusted the Japanese and wanted to ally Korea with the United States of America.[40] She established English language schools in Korea.[41] She sent an emissary to meet with President Arthur to discuss the growing threat of Japan.[42] Queen Min even patronised an American missionary named Mary F. Scranton.[43] Mary F. Scranton founded a women’s university known as Ewha Academy (now known as Ewha University).[44]

In 1881, Queen Min began to make military reforms.[45] She tried a military system based on the Japanese military system.[46] However, she angered many military officials who opposed the new military system.[47] It led to a military rebellion that was supported by Grand Internal Prince Heungseon Daewongun in 1882.[48] This forced Queen Min and King Gojong to flee Seoul in disguise.[49] They fled to Cheongju. Queen Min asked China for help to restore her husband to the throne.[50]

Once China restored King Gojong and Queen Min to power, the British Navy occupied Geomun Island in 1885.[51] Queen Min sent a German to Japan to negotiate for the British Navy to withdraw.[52] Japan began to entrench itself deeper into Korean politics.[53] Queen Min tried to oppose Japan by becoming allies with Russia.[54] Queen Min met with Russian emissaries. She invited Russian students to study abroad in Seoul.[55] The Japanese officials grew concerned about Queen Min’s alliance with Russia.[56] They planned to eliminate her to increase their ambitions in Korea.[57]

In the autumn of 1895, a Japanese ambassador named Miura Goro began to plan Queen Min’s assassination.[58] The assassination plot was called “Operation Fox Hunt.”[59] On 8 October 1895, a group of fifty assassins stormed Gyeongbokgung Palace.[60] They broke into Queen Min’s chambers.[61] They dragged Queen Min and four of her palace maids.[62] They stabbed her multiple times.[63] Then, they forced her four maids to confirm if it was Queen Min that they had killed.[64] They even whipped and raped the maids.[65] Once the maids confirmed Queen Min’s death, the assassins publicly displayed her body.[66] Then, the assassins took Queen Min’s body to the forest and burned it.[67] They scattered her ashes.[68]She was forty-three years old.

After Queen Min was murdered, the Japanese denied that they were responsible for the Queen’s assassination.[69] They pressured King Gojong to posthumously strip her royal titles.[70] King Gojong refused.[71] The Japanese government put Miura Goro on trial for the murder of Queen Min, but he was acquitted.[72] In 1897, King Gojong ordered a search to find Queen Min’s body.[73] However, all they could find was a finger bone.[74] He gave an elaborate funeral for her.[75] King Gojong declared Korea to be named the Korean Empire.[76] He elevated her to the status of Empress.[77] He gave her the posthumous name of Empress Myeongseong the Great.[78]

Empress Myeongseong the Great has been deeply mourned by Koreans for over a century.[79] Koreans still commemorate the anniversary of her death.[80] It is no wonder why Empress Myeongseong the Great has been considered a national heroine.[81] She put the interests of her country first before herself. She has also become a very popular icon in Korea. She has been featured in magazines, musicals, fashion, songs, poems, and Korean dramas.[82] An example is the famous 2009 movie, The Sword with No Name, in which she is portrayed by Soo Ae. There is also a popular 2001 Korean drama based on her life called Empress Myeongseong, in which she is portrayed by three actresses: Moon Geung-young, Lee Mi-Yeong, and Choi Myung-gil. Thus, Empress Myeongseong the Great’s legacy will never be forgotten.

Sources:

Harper, D. (2022). Lonely Planet Korea. Ireland: Lonely Planet.

KBS World. (2012, 3 November). “Empress Myeongseong, the greatest female politician of the Joseon Dynasty”. Retrieved on October 28, 2023 from https://world.kbs.co.kr/service/conte....

Kore Limited. (2023, 24 March). “KORE Celebrates Women’s History Month (Feat. Queen Myeongseong). KORE: Keeping Our Roots Eternal. Retrieved on October 28, 2023 from https://korelimited.com/blogs/korelim....

Rowe, P. G., Fu, Y., Song, J. (2021). Korean Modern: The Matter of Identity: An Exploration Into Modern Architecture in an East Asian Country. Germany: Walter de Gruyter GmbH.

Shinichi, K. (2018). The Political History of Modern Japan: Foreign Relations and Domestic Politics. NY: Taylor & Francis.

Szczepanski, K. (2019, 16 May). “Biography of Queen Min, Korean Empress”. ThoughtCo. Retrieved on October 28, 2023 from https://www.thoughtco.com/queen-min-o....

World History. (2018). (n.p.): EDTECH.

[1] Harper, 2022

[2] KORE LIMITED, 24 March 2023

[3] KBS WORLD, 3 November 2011, para. 2

[4] KBS WORLD, 3 November 2011

[5] KBS WORLD, 3 November 2011

[6] KBS WORLD, 3 November 2011

[7] KBS WORLD, 3 November 2011

[8] KBS WORLD, 3 November 2011

[9] KBS WORLD, 3 November 2011

[10] KBS WORLD, 3 November 2011

[11] KBS WORLD, 3 November 2011

[12] KBS WORLD, 3 November 2011

[13] KBS WORLD, 3 November 2011

[14] KBS WORLD, 3 November 2011

[15] KBS WORLD, 3 November 2011

[16] KBS WORLD, 3 November 2011

[17] KBS WORLD, 3 November 2011

[18] Szczepanski, 16 May 2019

[19] KBS WORLD, 3 November 2011

[20] KBS WORLD, 3 November 2011

[21] KBS WORLD, 3 November 2011

[22] Szczepanski, 16 May 2019

[23] Szczepanski, 16 May 2019

[24] Szczepanski, 16 May 2019

[25] Szczepanski, 16 May 2019

[26] Szczepanski, 16 May 2019

[27] KBS WORLD, 3 November 2011

[28] KBS WORLD, 3 November 2011

[29] KBS WORLD, 3 November 2011

[30] Szczepanski, 16 May 2019

[31] Szczepanski, 16 May 2019

[32] Szczepanski, 16 May 2019

[33] Szczepanski, 16 May 2019

[34] World History, 2018

[35] Rowe, et al., 2021

[36] Harper, 2022

[37] KORE LIMITED, 24 March 2023, para. 2

[38] KORE LIMITED, 24 March 2023

[39] KORE LIMITED, 24 March 2023

[40] KORE LIMITED, 24 March 2023

[41] KORE LIMITED, 24 March 2023

[42] KORE LIMITED, 24 March 2023

[43] KORE LIMITED, 24 March 2023

[44] KORE LIMITED, 24 March 2023

[45] Shinichi, 2018

[46] Shinichi, 2018

[47] Shinichi, 2018

[48] Shinichi, 2018; Harper, 2022

[49] KBS WORLD, 3 November 2011

[50] KBS WORLD, 3 November 2011

[51] KBS WORLD, 3 November 2011

[52] KBS WORLD, 3 November 2011

[53] KBS WORLD, 3 November 2011

[54] KBS WORLD, 3 November 2011

[55] Szczepanski, 16 May 2019

[56] Szczepanski, 16 May 2019

[57] Szczepanski, 16 May 2019

[58] Szczepanski, 16 May 2019

[59] Szczepanski, 16 May 2019, para. 28

[60] Szczepanski, 16 May 2019

[61] Szczepanski, 16 May 2019

[62] Szczepanski, 16 May 2019

[63] Szczepanski, 16 May 2019

[64] Szczepanski, 16 May 2019

[65] Szczepanski, 16 May 2019

[66] Szczepanski, 16 May 2019

[67]Szczepanski, 16 May 2019

[68] Szczepanski, 16 May 2019

[69] Szczepanski, 16 May 2019

[70] Szczepanski, 16 May 2019

[71] Szczepanski, 16 May 2019

[72] Szczepanski, 16 May 2019

[73] Szczepanski, 16 May 2019

[74] Szczepanski, 16 May 2019

[75] Szczepanski, 16 May 2019

[76] Harper, 2022

[77] KBS WORLD, 3 November 2011

[78] Szczepanski, 16 May 2019; KORE LIMITED, 24 March 2023

[79] Shinichi, 2018

[80] Shinichi, 2018

[81] Harper, 2022

[82] KORE LIMITED, 24 March 2023

The post Empress Myeongseong the Great – Korea’s beloved Empress appeared first on History of Royal Women.

September 21, 2024

Book News Week 39

Book News Week 39 – 23 September – 29 September 2024

Cooking and the Crown: Royal recipes from Queen Victoria to King Charles III

Hardcover – 26 September 2024 (UK)

Royal Women at Ugarit (The Ancient Word)

Hardcover – 27 September 2024 (US & UK)

Princess Victoria Ka’iulani: Last Heir of the Hawaiian Kingdom

Paperback – 23 September 2024 (US & UK)

The post Book News Week 39 appeared first on History of Royal Women.

Royal Wedding Recollections – Princess Astrid of Belgium & Lorenz, Archduke of Austria-Este

On 22 September 1984, Princess Astrid of Belgium married Lorenz, Archduke of Austria-Este.1 He is a grandson of the last Emperor of Austria, Charles I, while Princess Astrid is the daughter of King Albert II of Belgium.

Embed from Getty ImagesPrincess Astrid wore a taffeta dress with a high neck and large puffed sleeves made by Louis Mies. She wore her mother’s family veil, which was fastened with a crown of flowers.

(Screenshot/Fair Use)

(Screenshot/Fair Use) (Screenshot/Fair Use)

(Screenshot/Fair Use)The civil ceremony took place in the Gothic chamber of the Brussels Town Hall, while the religious ceremony took place in the Notre-Dame des Sablons Roman Catholic Church.

Astrid and Lorenz went on to have five children together. On 10 November 1995, his father-in-law, King Albert II of Belgium, created Lorenz a Prince of Belgium by royal decree.

The post Royal Wedding Recollections – Princess Astrid of Belgium & Lorenz, Archduke of Austria-Este appeared first on History of Royal Women.

September 19, 2024

The Dutch Diamond Bandeau

The Dutch Diamond Bandeau consists of diamonds that were originally part of a necklace.

RP-F-F15718 via Rijksmuseum (public domain)

RP-F-F15718 via Rijksmuseum (public domain)This necklace was given to Emma of Waldeck and Pyrmont in 1879 for her wedding to King William III of the Netherlands.

It was her daughter Wilhelmina who had the necklace turned into a bandeau tiara in 1937. After her death, it was inherited by her daughter Juliana.

Embed from Getty ImagesIt is still a much-loved and much-worn tiara by the women in the Dutch royal family.

Embed from Getty ImagesThe post The Dutch Diamond Bandeau appeared first on History of Royal Women.

September 18, 2024

The Year of Isabella I of Castile – Isabella is recognised as the rightful heir to the throne

On 19 September 1468, King Henry IV of Castile recognised his half-sister, the future Queen Isabella I of Castile, as the rightful heir to the throne of Castile over his daughter, Joanna.

The Treaty of the Bulls of Guisando was agreed upon on top of the hill near the Bulls of Guisando. Isabella now officially became the Princess of Asturias.

In the years before this, a rebellion had broken out following rumours that Henry’s daughter Joanna was not his daughter but rather the daughter of a nobleman named Beltrán de la Cueva. Isabella’s younger brother Alfonso had initially been the face of the rebellion, but he died at the age of 14 in 1468. Isabella took over his claim upon Alfonso’s death, and she preferred to negotiate with King Henry.

Neither Joanna nor her mother, Joan of Portugal, was present when the treaty was signed. Joan, “as soon as she heard how the infanta Isabella had been sworn in as princess, she was very sad, both because of the dishonour it brought her and because of the loss of her daughter to such vituperation. For which, to speak without affection or passion, she bears great guilt and responsibility because if she had lived more honestly, she would not have been treated with such vituperation.”1 Joan protested to Isabella being made Princess of Asturias, but it does appear she was briefly reunited with her daughter at Buitrago.

There was another important stipulation in the treaty – while Isabella would allow Henry to search for a husband for her, she would have the final say in the matter. It said, “She must marry whoever the king decides on, with the volition of the lady princess and by agreement with the council [made up] of the archbishop [of Seville], the Master [of the Santiago Order, Pachecho] and the Count [of Plascencia, Álvaro de Zúñiga].”2

The following year, Isabella married the future King Ferdinand II of Aragon, which went against the stipulation in the treaty. Henry indeed changed his mind in the face of Isabella’s marriage and reinstated Joanna as Princess of Asturias. Joan swore an oath that Joanna was “the legitimate and natural daughter of the said lord king and mine.”3

King Henry declared, “In order to stop certain warring and divisions that existed in these kingdoms at the time and more of which was expected, and because the said infanta [Isabella] promised and publicly swore to obey and serve me as her king… and to marry whomsoever I chose… I ordered that that my sister, the infanta, should be entitled and sworn in as princess and heiress. She did the opposite, doing me a great and damaging disservice, disrespecting me, breaking both her own sworn oath and the laws of these kingdoms while creating great upheaval and scandal. As a result, and given that her swearing-in [as heiress] prejudiced my daughter Princess Joanna and her rights, that second oath to my sister is declared invalid.”4

Isabella angrily wrote to Henry, “You complain about the breaking of promises, but forget the promises made to me that were broken. For which reason I was no longer obliged to abide by anything that had been pledged.”5

It would be a few years before there was a chance of a reconciliation between brother and sister.

The post The Year of Isabella I of Castile – Isabella is recognised as the rightful heir to the throne appeared first on History of Royal Women.

September 17, 2024

Book Review: The Making of Juana of Austria: Gender, Art, and Patronage in Early Modern Iberia edited by Noelia García Pérez

*review copy*

Juana, or Joanna of Austria, was the daughter of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor and Isabella of Portugal.

Born in 1535 as their youngest surviving child, she went on to marry her double first cousin, the 14-year-old John Manuel, Prince of Portugal, when she was 16 years old. She was left a pregnant widow just two years later and gave birth to the future King Sebastian of Portugal in 1554.

However, she was recalled to Spain just six months after her son’s birth to act as regent and would never see her son again.

The Making of Juana of Austria: Gender, Art, and Patronage in Early Modern Iberia, edited by Noelia García Pérez, consists of several essays about different aspects of Joanna’s life. While the essays are all excellent, for me, this book really highlighted how much I would have liked a full biography about this remarkable woman.

The essays range from subjects about her image to representation and display. This may seem rather vague, and some of them do divert a bit from their primary focus. Overall, I really enjoyed this book, but the separate essays give it a different feel.

The Making of Juana of Austria: Gender, Art, and Patronage in Early Modern Iberia edited by Noelia García Pérez is available now in the UK and the US.

The post Book Review: The Making of Juana of Austria: Gender, Art, and Patronage in Early Modern Iberia edited by Noelia García Pérez appeared first on History of Royal Women.

September 15, 2024

Mary of Austria – “A woman, no less” (Part two)

After being installed as governor on 5 July 1531, Mary moved her court to Brussels and sold her aunt’s palace to the city of Mechelen. Perhaps one of her biggest challenges was her personal sympathy for Protestantism, but she had to remain opposed to it publicly. Charles could be cruel to her, and he once told her, “You are a woman; you are not allowed to speak of such things.”1 She was forced to execute Charles’s religious policies.

She was faced with unrest in the Low Countries several times and acted as a mediator during these times. However, she did not have enough military manpower to end any uprising. She also continued to act as a fundraiser for her brother, as he was almost constantly at war with France.

Her court in Brussels consisted of over 150 people, and the protocol would rule over daily life. Religion played a large part, and Mary went to Mass daily. She also maintained her love of music, and musicians accompanied her when she travelled. She took in her nieces, Dorothea and Christina, after the death of their mother, Isabella, and their aunt, Margaret. Mary became especially close to Christina, and Mary was horrified to learn that the 11-year-old Christina was due to marry the much older Duke of Milan.

She wrote to her brother, “Monseigneur, since the words of the treaty clearly show that the marriage is to be consummated immediately and she will have to take her departure without delay, I must point out that she is not yet old enough for this, being only eleven years and a half, and I hold that it would be contrary to the laws of God and reason to marry her at so tender an age.”2 Charles refused to yield, but Mary managed to delay the wedding anyway.

Mary would be Governor of the Habsburg Netherlands for 24 years. She had been considering giving up the job for some time, and her health had been in decline as well. She asked Charles for permission to withdraw to Spain with her sister, Eleanor. At the time, Charles was also in the process of passing power to his son and brother. Charles tried everything he could to keep Mary as governor, but while she was devoted to Charles, she was less attached to his son, the future King Philip II. In the end, Mary was allowed to resign.

On 25 October 1555, Charles transferred the sovereignty of the Habsburg Netherlands to Philip as Mary watched on. He took the time to praise Mary for her work. Mary also spoke and asked for forgiveness for any mistakes she had made. She said, “If my abilities, my knowledge and my wealth had been commensurate with the goodwill, love and devotion with which I have given myself to this office, I am sure that no monarch would ever have been better served and no country would ever have been better governed than thou.”3

It wasn’t until September 1556 that Charles, Eleanor and Mary finally departed for Spain. While Charles headed for a convent in Yuste, the sisters had not decided where to settle. Mary had wanted to be with her mother, Joanna, but she died in April 1555. Eleanor had one wish above all – to see her daughter again. She had one daughter named Maria from her first marriage to King Manuel I of Portugal, but she had not seen her since she was a child. The Portuguese court was not willing to cooperate in facilitating a meeting. While they waited out the negotiations, Mary and Eleanor travelled to Jarandilla, from where they could visit Charles.

Finally, a meeting was arranged between Eleanor and Maria and on 14 December 1557, Mary joined her sister and travelled to Badajoz. They stayed there for three weeks and showered Maria with gifts. In the end, Maria did not want to stay with her mother and chose to return to Lisbon. After this meeting, Eleanor and Mary wanted to visit Our Lady of Guadalupe, but Eleanor fell ill while on the way. Mary wrote to their brother, “It’s so sad to see her like this; she could no longer speak; she sobbed and shed so many tears.”4 Eleanor died at Talavera on 18 February 1558.

Despite everything, both Charles and Philip still tried to convince her to return to the Habsburg Netherlands. In March 1558, she settled in Cigales as she awaited Philip’s permission for where she could stay. In September, she finally conceded under terms, among others, that the assignment was temporary. During this time, her brother Charles lay dying, and he would no doubt be comforted by the fact that she would be returning to the Habsburg Netherlands. But she would not see him again – he died on 21 September 1558.

His death hit Mary hard. In early October, she was struck twice by heart problems, but she insisted that she would still go. She rested at Valladolid before returning to Cigales, where the preparations were being made. On 18 October 1558, she suffered a third heart attack, which proved to be fatal. Her niece, Joanna, had been present at her bedside, and she told Philip that their aunt had to be in heaven, as she had died as such a good Christian.5

In her will, she requested that a small golden heart necklace, once worn by her husband Louis, should be melted and donated to the poor.6

Mary saw her governorship as a failure and blamed it partly on her sex. She wrote, “How could I have been so reckless to think that I am capable of leading this government, or any government, as a woman no less, and as such incapable of the important acts of government?” She seemed to have forgotten that both her grandmother and her mother ruled in their own right, admittedly with varying degrees of success, but still. Mary underestimated herself, and even the people of the Netherlands knew they had lost a great leader.7

The post Mary of Austria – “A woman, no less” (Part two) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

September 14, 2024

Book News Week 38

Book News week 38 – 16 September – 22 September 2024

The Romanovs: Imperial Russia and Ruling the Empire, 1613-1917

Hardcover – 19 September 2024 (UK)

Queens in Antiquity and the Present: Speculative Visions and Critical Histories

Hardcover – 19 September 2024 (US)

The post Book News Week 38 appeared first on History of Royal Women.