Ajith Kumar's Blog: The Murder of Alexander the Great - Posts Tagged "kalanus"

• The assassin of Alexander the Great identified

For the first time ever, evidence has emerged from the ancient Sanskrit texts that the legend of Alexander the Great, who invaded India in 326 BC, forms part of the Indian folklore. Astonishing new findings in the historical narrative, "The Murder Of Alexander the Great" (in two books: the Puranas and The Secret war) by Ajith Kumar unbundle the untold parts of the history of Alexander's global conquests, which culminated in his mysterious death in Babylon 3 years later.

In 331 BC, after defeating of the Persian Emperor Darius at the bloody battle at Gaugamela, at the Arbela temple (modern Erbil in Iraq) Alexander was enthroned as the King of the World. More importantly, he was designated as the mortal representative of the great lord Azura Mazda. During the coronation ceremony, the conqueror was crowned as the King of the Assur region (Assyria in modern Iraq), where the Kings were traditionally named as an Asura, the mortal representative of the lord. Consequently, when he subsequently invaded India, in the legends in the Indian Sanskrit texts, known as the Puranas, he came to be called an Asura Raja. The Puranas were Sanskrit texts that chronicled the deeds of ancient kings. The Sanskrit word Purana literally means ancient history. In this tradition, the Vamana Purana, Bhagavata Purana, and the Skanda Purana tell us the untold story of Alexander the Great's Indian invasion.

In the Indus valley, the holy land of the Aryan tribes, Alexander successfully encountered massive opponents, monstrous floods, and treacherous warfare. Unexpectedly, he also faced an army mutiny, following which he was compelled to stop his Indian campaign and what followed were disasters that crippled the Greek army as he returned to Persia.

Deification legends were quite common in the ancient world. The fascinating myths of Alexander, widely spread through the ancient religious texts, appears in the gospels in the prophecies of Daniel. In the Hebrew traditions, he appears as a prophet who knocks at the gates of heaven. In European texts, he became an invincible knight. In the Persian legends, he appears as a two-horned Satan who destroyed the fire altars of Zoroastrian priests. Finally, in the Indian texts he is depicted as the king of the Asuras, Mahabali, who ruled the netherworlds.

The Indian Puranas apparently tell us the history of the ancient world through enchanting mythology, and one can only admire at the huge share of historical information available in the Indian scriptures. A popular myth in the Puranas recounts the history of the Greek conquest of the Indus Valley and unveils the covert Indian strategy that led to the rapid return march and the early death of Alexander.

"The Murder of Alexander the Great, Book 1 - The Puranas" draws, for the first time, a parallel between Greek and Indian history. The book presents sixteen pieces of evidence to confirm that Alexander was prominently represented in the ancient Sanskrit texts as Mahabali. In fact, when the invading army descended from the Hindukush mountains in 326 BC into the Indus Valley and occupied Taxila first, the massive army consisted of 120,000 soldiers. However, Alexander could not conquer India, as he had to abandon the attempt after a religious sacrifice on an altar in Kurukshetra (in modern Punjab), where a Sadhu named Kalanus declared the omens unfavourable to proceed. Alexander abandoned his aggressive campaigns and decided to return to return to Babylon. The Puranas link this incident in the myths of Asura Raja Mahabali and recount how the King of Asuras was tactfully deceived and guided by the Sadhu to a region known as Patala. The unearthly domains of Patala, at the mouth of the Indus, was truly the capital of Alexander the Great for about an year. He was trapped for months in the Patala region, stuck between two deserts on both sides of the Indus River, and the Arabian sea at its mouth. The Sadhu, known to the Greek historians as Kalanus (Calanus), had deceived and led him to Patala, the hell in Indian mythology.

Confirming this, a verse in the Sanskrit Puranas records the chronology of the day Alexander submitted to the oracular advice of the Sadhu on the altar in Kurukshetra in Punjab. The date coincides with the annual Onam festival which commemorates the surrender of Mahabali, the legendary role of Alexander, and thus confirms this to be a historical fact. The surrender of Mahabali (Alexander) is even today celebrated as the Onam festival in Kerala, a state in South India, on the twelfth day in the month of Shravana, which is the same day Alexander submitted to the oracular advice of the Sadhu. During the Onam festival people in Kerala commemorate the legends of Alexander the Great, who tried to conquer the three worlds, but was compelled to return to Patala.

The Indian texts tell us a stranger than fiction version of the ancient history and explains how Alexander’s invincible army, which came to conquer India in 326 BC, was crippled and its leader secretly assassinated.

In Book 2 - The Secret War, the narrative explores the ruthless execution of a secret war strategy, known as the Battle of intrigue, outlined in the Arthashastra of Chanakya. Chanakya, the renowned military strategist of ancient India, was the Prime Minister of Taxila, when Alexander occupied it in April 326 BC. The secret strategies of war prescribed in the Arthashastra of Chanakya were unleashed against the Greek war lord, which crippled the invading army, created a mutiny in its ranks, and diverted it out of India to Patala. Alexander was cunningly forced into the barrenness of the Gedrosian desert subsequently and most of the Greek soldiers perished in its treacherous landscape.

The hidden history of the age comes alive in the two books and explains how Alexander was trapped in the Indus valley for two years and why his army revolted in Punjab. Only the Arthashastra of Chanakya explains the reasons for the revolt in the Greek army and the disasters that trailed Alexander during the Indian campaign.

After his disastrous Indian expedition, on reaching Babylon, Alexander died in suspicious circumstances at the age of 33. Widespread rumors circulated in the ancient world that he was murdered. But there was no evidence until now. However, the Indian Puranas, and other ancient Sanskrit texts, unravel the name of the exotic weapon used to murder Alexander.

The narrative in 'The murder of Alexander the Great" unravels seventy-two discoveries that go on to unearth not only Alexander’s assassin but also identifies the lethal weapon named as the ‘destroyer of time’.

The suspicions surrounding the death of Alexander had remained unresolved even after two millennia. 'The Murder of Alexander the Great' provides the final answers to the greatest murder mystery of the ancient world.

Available on Amazon Books:

The Puranas

The Murder of Alexander the Great, Book 1: The Puranas.

The Secret War

The Murder of Alexander the Great, Book 2: The Secret war

https://murderofalexanderthegreat.com

In 331 BC, after defeating of the Persian Emperor Darius at the bloody battle at Gaugamela, at the Arbela temple (modern Erbil in Iraq) Alexander was enthroned as the King of the World. More importantly, he was designated as the mortal representative of the great lord Azura Mazda. During the coronation ceremony, the conqueror was crowned as the King of the Assur region (Assyria in modern Iraq), where the Kings were traditionally named as an Asura, the mortal representative of the lord. Consequently, when he subsequently invaded India, in the legends in the Indian Sanskrit texts, known as the Puranas, he came to be called an Asura Raja. The Puranas were Sanskrit texts that chronicled the deeds of ancient kings. The Sanskrit word Purana literally means ancient history. In this tradition, the Vamana Purana, Bhagavata Purana, and the Skanda Purana tell us the untold story of Alexander the Great's Indian invasion.

In the Indus valley, the holy land of the Aryan tribes, Alexander successfully encountered massive opponents, monstrous floods, and treacherous warfare. Unexpectedly, he also faced an army mutiny, following which he was compelled to stop his Indian campaign and what followed were disasters that crippled the Greek army as he returned to Persia.

Deification legends were quite common in the ancient world. The fascinating myths of Alexander, widely spread through the ancient religious texts, appears in the gospels in the prophecies of Daniel. In the Hebrew traditions, he appears as a prophet who knocks at the gates of heaven. In European texts, he became an invincible knight. In the Persian legends, he appears as a two-horned Satan who destroyed the fire altars of Zoroastrian priests. Finally, in the Indian texts he is depicted as the king of the Asuras, Mahabali, who ruled the netherworlds.

The Indian Puranas apparently tell us the history of the ancient world through enchanting mythology, and one can only admire at the huge share of historical information available in the Indian scriptures. A popular myth in the Puranas recounts the history of the Greek conquest of the Indus Valley and unveils the covert Indian strategy that led to the rapid return march and the early death of Alexander.

"The Murder of Alexander the Great, Book 1 - The Puranas" draws, for the first time, a parallel between Greek and Indian history. The book presents sixteen pieces of evidence to confirm that Alexander was prominently represented in the ancient Sanskrit texts as Mahabali. In fact, when the invading army descended from the Hindukush mountains in 326 BC into the Indus Valley and occupied Taxila first, the massive army consisted of 120,000 soldiers. However, Alexander could not conquer India, as he had to abandon the attempt after a religious sacrifice on an altar in Kurukshetra (in modern Punjab), where a Sadhu named Kalanus declared the omens unfavourable to proceed. Alexander abandoned his aggressive campaigns and decided to return to return to Babylon. The Puranas link this incident in the myths of Asura Raja Mahabali and recount how the King of Asuras was tactfully deceived and guided by the Sadhu to a region known as Patala. The unearthly domains of Patala, at the mouth of the Indus, was truly the capital of Alexander the Great for about an year. He was trapped for months in the Patala region, stuck between two deserts on both sides of the Indus River, and the Arabian sea at its mouth. The Sadhu, known to the Greek historians as Kalanus (Calanus), had deceived and led him to Patala, the hell in Indian mythology.

Confirming this, a verse in the Sanskrit Puranas records the chronology of the day Alexander submitted to the oracular advice of the Sadhu on the altar in Kurukshetra in Punjab. The date coincides with the annual Onam festival which commemorates the surrender of Mahabali, the legendary role of Alexander, and thus confirms this to be a historical fact. The surrender of Mahabali (Alexander) is even today celebrated as the Onam festival in Kerala, a state in South India, on the twelfth day in the month of Shravana, which is the same day Alexander submitted to the oracular advice of the Sadhu. During the Onam festival people in Kerala commemorate the legends of Alexander the Great, who tried to conquer the three worlds, but was compelled to return to Patala.

The Indian texts tell us a stranger than fiction version of the ancient history and explains how Alexander’s invincible army, which came to conquer India in 326 BC, was crippled and its leader secretly assassinated.

In Book 2 - The Secret War, the narrative explores the ruthless execution of a secret war strategy, known as the Battle of intrigue, outlined in the Arthashastra of Chanakya. Chanakya, the renowned military strategist of ancient India, was the Prime Minister of Taxila, when Alexander occupied it in April 326 BC. The secret strategies of war prescribed in the Arthashastra of Chanakya were unleashed against the Greek war lord, which crippled the invading army, created a mutiny in its ranks, and diverted it out of India to Patala. Alexander was cunningly forced into the barrenness of the Gedrosian desert subsequently and most of the Greek soldiers perished in its treacherous landscape.

The hidden history of the age comes alive in the two books and explains how Alexander was trapped in the Indus valley for two years and why his army revolted in Punjab. Only the Arthashastra of Chanakya explains the reasons for the revolt in the Greek army and the disasters that trailed Alexander during the Indian campaign.

After his disastrous Indian expedition, on reaching Babylon, Alexander died in suspicious circumstances at the age of 33. Widespread rumors circulated in the ancient world that he was murdered. But there was no evidence until now. However, the Indian Puranas, and other ancient Sanskrit texts, unravel the name of the exotic weapon used to murder Alexander.

The narrative in 'The murder of Alexander the Great" unravels seventy-two discoveries that go on to unearth not only Alexander’s assassin but also identifies the lethal weapon named as the ‘destroyer of time’.

The suspicions surrounding the death of Alexander had remained unresolved even after two millennia. 'The Murder of Alexander the Great' provides the final answers to the greatest murder mystery of the ancient world.

Available on Amazon Books:

The Puranas

The Murder of Alexander the Great, Book 1: The Puranas.

The Secret War

The Murder of Alexander the Great, Book 2: The Secret war

https://murderofalexanderthegreat.com

Published on August 31, 2020 16:52

•

Tags:

alexander-the-great, ancient-indian-history, ancient-world-history, arbela, arthashastra, assassination, asura, asura-raja, calanus, chanakya, greek-history, historical-mystery, kalanus, kuruskshetra, macedonia, mahabali, murder, murder-of-alexander-the-great, patala, puranas, sanskrit-myths

Kalanus (Calanus) and Alexander the Great

Kalanus (Calanus) stopped Alexander's Indian invasion.

Anyone familiar with the history of Alexander the Great will easily recognize the name of Kalanus (Calanus, Kalana, Kalanos), the mysterious ascetic Brahman from Taxila who accompanied Alexander throughout his campaign in India.

Arrian wrote: “I have mentioned Kalanus because no history of Alexander would be complete without the story of Kalanus.” The Greeks fittingly called him a gymnosophist, meaning a “naked philosopher.” Kalanus gained a great reputation as an oracle and a philosopher (sophist) in Alexander’s camp.

Kalanus was one of a group of monks belonging to a cult that practiced extreme asceticism. They sowed no seeds nor reaped any grains, and built no homes nor wore any clothes. They displayed their contempt for the propriety of civilized life by discarding clothing and shelter. These mendicants, as is usual with the eastern mystic cults, lived in the open in Taxila, usually exposed to the harsh elements of nature. Because life’s miseries start with the greed for basic human needs, they restricted their physical and mental needs to the barest necessities for survival.

The first appearance of Kalanus in front of Alexander is incredibly theatrical and it had unpredictable consequences in the life of Alexander.

Arrian has recorded the intriguing episode: “On the stately appearance of Alexander and his huge army at the city gates of Taxila, some naked Brahman ascetics standing by the roadside, dismally stamped their feet on the ground and gave no other signs of interest.”

General Onesecritus, who was sent by Alexander to fetch these sadhus, says that Kalanus was lying naked, resting on stone, when he first saw him; that he therefore, approached him and greeted him. Kalanus told him that if he wished to learn, he should take off his clothes, lie down naked on the same stones, and thus to hear his teachings.

Later, Plutarch confirms: “As to Kalanus, it is certain that King Taxiles prevailed with him to go to Alexander.” Kalanus soon accompanied the army up to Persia and Alexander took his “impartial” spiritual advice all through the campaign.

Later events prove that Kalanus was part of a major military strategy defined by the Indian sages as "kuta-yuddha," or the Battle of Intrigue. The Indians tactically planted Sadhu Kalanus in the barracks of Alexander and thereby successfully infiltrated the enemy camp.

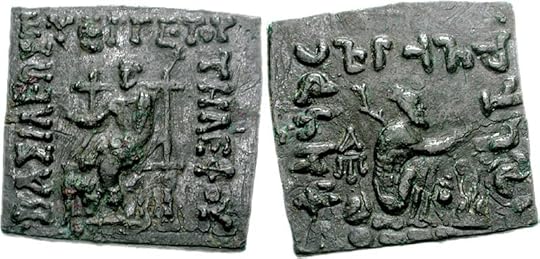

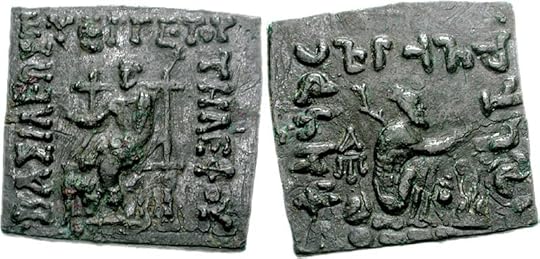

Amazingly, a solid piece of evidence in the form of a coin that portrays the real image of Kalanus has survived all these centuries in the legendary city of Taxila. The coin, issued by King Telephos of Taxila, depicts the icon of Kalanus, with his name. King Telephos appears to have issued the coin as a tribute to Kalanus, who had miraculously stopped Alexander on the altar in Kurukshetra and helped the Indians to recapture the throne of Taxila. The commemorative coin records the decisive defeat of Alexander and confirms the end of his Indian conquest in Punjab.

On the reverse side of the coin, contrary to tradition, a naked Indian sadhu is featured sitting on an altar of stones and offering a fire sacrifice.

This image has perplexed most scholars, because no other coin ever depicts the icon of a sadhu Brahman, on the side on which, notably, the king’s image customarily appears. Shockingly, however, on this coin King Telephos had boldly replaced the image of Alexander with that of Sadhu Kalanus.

The Kharosthi legend on the coin reads: “Maharajasa Kalana kramasa Telephasa.” The corresponding Greek legend on the other side of the coin reads: “Basileos Eyepgetoy Thlefoy.” As the Greek word eyepgetoy means “inherited divine power,” we can assume that the corresponding Kharosthi word kramasa on the other side of the coin also means eyepgetoy, or divine inheritance.

Plutarch narrates what happened on the altar in Punjab, before Alexander decided to stop his Indian invasion.

“It was Kalanus, as we are told, who laid before Alexander the famous illustration of state government. It was this. He threw down upon the ground a dry shrivelled hide, and set his foot upon the outer edge of it; the hide was pressed down in one place, but rose up in others. He stepped all around the hide and showed that this was the result wherever he pressed the edge down, and then at last he stood in the middle of it, and amazingly, it was all held down firm and still. The similitude was designed to show that Alexander ought to put most constraint upon the middle of his empire and not wander far away from it.”

After few minutes, as the sacrifice ended on the altar, Alexander declared to the crowds that he accepted the oracular advice of the Brahman, and the war campaign in India ended abruptly. Alexander announced to the crowds that the sacrificial omens were averse to proceeding. This event alone eventually helped to change the inflexible resolve of Alexander and altered the course of world history.

Read more about this amazing story in "The Murder of Alexander the Great: Book 2 - The Secret War." - https://amzn.com/0999071440

About what followed the altar sacrifice and the demonstration by the oracle (Sadhu), we have the testimony of Arrian in the Anabasis. (Arrian, Anabasis, 5.28.)

"When there was a profound silence throughout the camp, and the soldiers were evidently annoyed at his wrath, without being at all changed by it. Ptolemy, son of Lagus, says that he nonetheless offered sacrifices there for passing the river.

But the sacrificial victim was unfavourable to him when he sacrificed.

Then he collected the oldest of the Companions and especially those who were friendly to him, and as all things indicated the advisability of returning, he made known to the army he had resolved to march back."

A legend on the ancient Roman road map, the Peutinger map, written by the side of the altars in Punjab, said in ancient Latin: “Hic Alexander responsum accepit. About what followed the altar sacrifice and the demonstration by the oracle (Sadhu), we have the testimony of Arrian in the Anabasis. (Arrian, Anabasis, 5.28.)

"When there was a profound silence throughout the camp, and the soldiers were evidently annoyed at his wrath, without being at all changed by it. Ptolemy, son of Lagus, says that he nonetheless offered sacrifices there for passing the river.

But the sacrificial victim was unfavourable to him when he sacrificed.

Then he collected the oldest of the Companions and especially those who were friendly to him, and as all things indicated the advisability of returning, he made known to the army he had resolved to march back."

The legend on the ancient Roman road map, the Peutinger map, engraved by the side of the icon of the altars, said in ancient Latin: “Hic Alexander responsum accepit. Usque quo Alexander.”

Roman emperor Augustus had ordered the creation of this map in 12 BC. The map was engraved in marble and put on display in the Porticus Vipsania in the Campus Agrippae area in Rome.

The curious label on the map means, “Here Alexander accepted the oracular advice to the question: How far can you go, Alexander?” “No further,” the priest himself had answered.

This sentence is the most significant evidence, literally carved on stone that proves that Alexander stopped his military campaign on the advice of the sadhu (oracle) Kalanus.

Anyone familiar with the history of Alexander the Great will easily recognize the name of Kalanus (Calanus, Kalana, Kalanos), the mysterious ascetic Brahman from Taxila who accompanied Alexander throughout his campaign in India.

Arrian wrote: “I have mentioned Kalanus because no history of Alexander would be complete without the story of Kalanus.” The Greeks fittingly called him a gymnosophist, meaning a “naked philosopher.” Kalanus gained a great reputation as an oracle and a philosopher (sophist) in Alexander’s camp.

Kalanus was one of a group of monks belonging to a cult that practiced extreme asceticism. They sowed no seeds nor reaped any grains, and built no homes nor wore any clothes. They displayed their contempt for the propriety of civilized life by discarding clothing and shelter. These mendicants, as is usual with the eastern mystic cults, lived in the open in Taxila, usually exposed to the harsh elements of nature. Because life’s miseries start with the greed for basic human needs, they restricted their physical and mental needs to the barest necessities for survival.

The first appearance of Kalanus in front of Alexander is incredibly theatrical and it had unpredictable consequences in the life of Alexander.

Arrian has recorded the intriguing episode: “On the stately appearance of Alexander and his huge army at the city gates of Taxila, some naked Brahman ascetics standing by the roadside, dismally stamped their feet on the ground and gave no other signs of interest.”

General Onesecritus, who was sent by Alexander to fetch these sadhus, says that Kalanus was lying naked, resting on stone, when he first saw him; that he therefore, approached him and greeted him. Kalanus told him that if he wished to learn, he should take off his clothes, lie down naked on the same stones, and thus to hear his teachings.

Later, Plutarch confirms: “As to Kalanus, it is certain that King Taxiles prevailed with him to go to Alexander.” Kalanus soon accompanied the army up to Persia and Alexander took his “impartial” spiritual advice all through the campaign.

Later events prove that Kalanus was part of a major military strategy defined by the Indian sages as "kuta-yuddha," or the Battle of Intrigue. The Indians tactically planted Sadhu Kalanus in the barracks of Alexander and thereby successfully infiltrated the enemy camp.

Amazingly, a solid piece of evidence in the form of a coin that portrays the real image of Kalanus has survived all these centuries in the legendary city of Taxila. The coin, issued by King Telephos of Taxila, depicts the icon of Kalanus, with his name. King Telephos appears to have issued the coin as a tribute to Kalanus, who had miraculously stopped Alexander on the altar in Kurukshetra and helped the Indians to recapture the throne of Taxila. The commemorative coin records the decisive defeat of Alexander and confirms the end of his Indian conquest in Punjab.

On the reverse side of the coin, contrary to tradition, a naked Indian sadhu is featured sitting on an altar of stones and offering a fire sacrifice.

This image has perplexed most scholars, because no other coin ever depicts the icon of a sadhu Brahman, on the side on which, notably, the king’s image customarily appears. Shockingly, however, on this coin King Telephos had boldly replaced the image of Alexander with that of Sadhu Kalanus.

The Kharosthi legend on the coin reads: “Maharajasa Kalana kramasa Telephasa.” The corresponding Greek legend on the other side of the coin reads: “Basileos Eyepgetoy Thlefoy.” As the Greek word eyepgetoy means “inherited divine power,” we can assume that the corresponding Kharosthi word kramasa on the other side of the coin also means eyepgetoy, or divine inheritance.

Plutarch narrates what happened on the altar in Punjab, before Alexander decided to stop his Indian invasion.

“It was Kalanus, as we are told, who laid before Alexander the famous illustration of state government. It was this. He threw down upon the ground a dry shrivelled hide, and set his foot upon the outer edge of it; the hide was pressed down in one place, but rose up in others. He stepped all around the hide and showed that this was the result wherever he pressed the edge down, and then at last he stood in the middle of it, and amazingly, it was all held down firm and still. The similitude was designed to show that Alexander ought to put most constraint upon the middle of his empire and not wander far away from it.”

After few minutes, as the sacrifice ended on the altar, Alexander declared to the crowds that he accepted the oracular advice of the Brahman, and the war campaign in India ended abruptly. Alexander announced to the crowds that the sacrificial omens were averse to proceeding. This event alone eventually helped to change the inflexible resolve of Alexander and altered the course of world history.

Read more about this amazing story in "The Murder of Alexander the Great: Book 2 - The Secret War." - https://amzn.com/0999071440

About what followed the altar sacrifice and the demonstration by the oracle (Sadhu), we have the testimony of Arrian in the Anabasis. (Arrian, Anabasis, 5.28.)

"When there was a profound silence throughout the camp, and the soldiers were evidently annoyed at his wrath, without being at all changed by it. Ptolemy, son of Lagus, says that he nonetheless offered sacrifices there for passing the river.

But the sacrificial victim was unfavourable to him when he sacrificed.

Then he collected the oldest of the Companions and especially those who were friendly to him, and as all things indicated the advisability of returning, he made known to the army he had resolved to march back."

A legend on the ancient Roman road map, the Peutinger map, written by the side of the altars in Punjab, said in ancient Latin: “Hic Alexander responsum accepit. About what followed the altar sacrifice and the demonstration by the oracle (Sadhu), we have the testimony of Arrian in the Anabasis. (Arrian, Anabasis, 5.28.)

"When there was a profound silence throughout the camp, and the soldiers were evidently annoyed at his wrath, without being at all changed by it. Ptolemy, son of Lagus, says that he nonetheless offered sacrifices there for passing the river.

But the sacrificial victim was unfavourable to him when he sacrificed.

Then he collected the oldest of the Companions and especially those who were friendly to him, and as all things indicated the advisability of returning, he made known to the army he had resolved to march back."

The legend on the ancient Roman road map, the Peutinger map, engraved by the side of the icon of the altars, said in ancient Latin: “Hic Alexander responsum accepit. Usque quo Alexander.”

Roman emperor Augustus had ordered the creation of this map in 12 BC. The map was engraved in marble and put on display in the Porticus Vipsania in the Campus Agrippae area in Rome.

The curious label on the map means, “Here Alexander accepted the oracular advice to the question: How far can you go, Alexander?” “No further,” the priest himself had answered.

This sentence is the most significant evidence, literally carved on stone that proves that Alexander stopped his military campaign on the advice of the sadhu (oracle) Kalanus.

Published on October 08, 2020 11:33

•

Tags:

alexander-the-great, ancient-world-history, calanus, greek-history, historical-fiction, indian-history, indian-invasion, indo-greek, kalanus, murder-mystery

Alexander the Great, Kalanus and Telephos coin

Alexander the Great, the Telephos coin and Kalanus

Ajith Kumar.

(These research notes were prepared for my 2 books - “The Murder of Alexander the Great, Book 1: The Puranas” and “The Murder of Alexander the Great, Book 2: The Secret War.”) Available on Amazon.com.

--------------------------------------------------------

Kalanus (Calanus, Greek : Kalanos, Sanskrit/ Kharosthi: Kalana), the mysterious ascetic Brahman from Taxila who accompanied Alexander the Great throughout his campaign in India, is familiar to historians. Kalanus gained a reputation as an oracle and a philosopher (sophist) in Alexander’s camp. The Greek historians called him a gymnosophist, meaning a “naked philosopher.” The classic sources called him a Brahman, as he was a member of the priestly caste, who advised the King on political matters.

Arrian wrote: “I have mentioned Kalanus because no history of Alexander would be complete without the story of Kalanus.” Plutarch points out the “attentions which Alexander so lavishly bestowed upon Dandamis and Kalanus.” (Plutarch, Lives, 8.5)

Kalanus belonged to a cult of Brahman monks that practiced extreme asceticism. They never ploughed any lands nor reaped any grains; they neither built homes nor wore any clothes. By discarding both clothing and shelter, they displayed their complete contempt for earthly comforts of life. These sadhus (mendicants), lived in the open outside the city gates of Taxila, always exposed to the harsh elements of nature. By ignoring basic human wants, they restricted their needs to the barest necessities for survival.

Alexander’s first encounter with Kalanus was outrageous by any means. In April 326 BC, after victoriously marching in arms for about eight years across Persia and Egypt, the heavily armed Greek army entered the Vedic world by crossing the Hindukush Mountains and then the Indus River at Attock, just below its junction with the Kabul River. Taxila, near modern Islamabad in Pakistan, was the first country beyond the Hindukush mountains that Alexander’s invading army occupied in the Indian subcontinent.

As Alexander approached Taxila city, he encountered a bizarre spectacle, which he had witnessed nowhere else in the world. Arrian has recorded the intriguing episode: “On the stately appearance of Alexander and his huge army at the city gates of Taxila, some naked Brahman ascetics standing by the roadside, dismally stamped their feet on the ground and gave no other signs of interest.” (Arrian, Anabasis, 7.1.5.)

The ascetics looked unconcerned by the massive ceremonial march of the army passing by. This unusual behavior surely attracted the attention of the majesty, who was also “a philosopher in arms.” Alexander asked through interpreters what they meant by this unusual behavior and the leader of these ascetics, Dandamis, replied: “You are just human like the rest of us, save you are always fighting and up to no good, traveling so many miles from your home, a nuisance to yourself and to others. Ah well! You will soon be dead, and then you will own just as much of this earth as will suffice to bury you.” (Arrian, Anabasis, 7.1.6.)

Alexander’s General Onesecritus says that he later met one of these sophists, Kalanus, who then accompanied the king as far as Persia and committed suicide in accordance with their ancestral custom, being placed upon a pyre and burned up. (Strabo, Geography, 15.1.61.)

Plutarch confirms that the Indian King Taxiles persuaded Kalanus to join Alexander’s camp: “As to Kalanus, it is certain that King Taxiles prevailed with him to go to Alexander. His real name was Sphines, but as in the Indian tongue, he saluted all he met with the word ‘Kala,’ the Greeks named him Kalanus. It was Kalanus, as we are told, who laid before Alexander the famous illustration of government.” (Plutarch, Alexander, 65.5.)

Alexander, while camping in Taxila, was much fascinated by Kalanus. He took him into his camp, made him one of his closest associates and often consulted him as his adviser. Because of this, Kalanus has received undue attention from the historians of Alexander. Alexander’s admiral Nearchus, engineer Aristobulus, and General Onesecritus were eyewitnesses in Taxila, and they mention in their records their own accounts about Kalanus. The later historians Arrian, Strabo, and Plutarch, who took the information from many earlier sources, also devote time to mention Kalanus, who appears to have had an important relation to Alexander. (Arrian, Anabasis, 7.1.5-3.6; Strabo 15.1.61-68; Plutarch, Lives, 7.67-70).

Onesecritus says he was sent by Alexander to meet the two ascetics, Dandamis and Kalanus, and to have requested them to come to Alexander (Strabo 15.1.63–65.715–716, Plutarch Alex. 64–65, Arrian, Anabasis, 7.2.2–4). Aristobulus claimed to have seen the two gymnosophists standing as they dined at Alexander’s table (Strabo 15.1.61.714).

The Telephos coin

---------------------

Now, to confirm the stories of Kalanus, research has unravelled a solid piece of evidence in the form of an ancient coin with the image and the name of Kalanus on it. (Ajith Kumar, The Murder of Alexander the Great, Book 1: The Puranas.)

The coin, issued by King Telephos of Taxila, is an exceptionally rare specimen that depicts a naked priest with his name inscribed on it. It depicts the image of Kalanus conducting an altar ceremony.

Numismatist Osmund Bopearachchi has identified the square bronze coin found in Taxila as that of the Indo-Greek king Telephos (Telephus), who ruled the region in around 75 BC. (Bopearachchi (1995), ‘Indian Brahman on a coin of Telephus’, Oriental Numismatic Society Newsletter 145, 8-9.) These coins weigh about nine grams each and are made of bronze or copper. Only few specimens of them exist.

Telephos, a king of Taxila, had issued the coin as a tribute to Kalanus, who had miraculously stopped Alexander the Great on the sacrificial altar in India and helped the Indians to recapture the throne of Taxila. Thus, the commemorative coin records the retreat of Alexander and confirms the end of his Indian conquest in Punjab.

In 1872, the Royal Numismatic Society mentioned a Telephos coin that was found at Attock in Taxila, where Alexander had pitched his camp few centuries earlier. (Royal Numismatic Society, 1872, vol. 12. Google ebooks, Plate XIV, Elliot collection.)

Another Telephos coin with the icon of Kalanus was found in Taxila in 1910. (Journal of the Asiatic society of Bengal. (J.A.S.B.), 1910, p. 561, copper, rectangular.) Pioneering archaeologist Sir Alexander Cunningham (1814–1893) assigned the Telephos coin to King Telephos of Taxila, who ruled at the time of King Maues of Kashmir, around 75 BC.

Telephos has been identified as the King of Taxila by Whitehead. (Whitehead, NC p. 334 no. 53, Pl. XVI, 14; Journal of the Asiatic society of Bengal (JASB), 1910, p. 496.) Alexander occupied the countries Bactria, Gandhara and Taxila, and established several colonies in ancient India (including modern Afghanistan and Pakistan).

After the invasion, territories conquered by Alexander were under the Indo-Greek Kingdom, ruled by more than 30 Hellenistic kings from the 2nd century BC to the beginning of the 1st century AD. They were often in conflict with each other. Indo-Greek kings combined the Greek and Indian symbols and scripts, as seen on their coins. All Indo-Greek kings after Apollodotus I mainly issued bilingual (Greek and Kharoshti) coins.

Bopearachchi noted:

"Telephos, who was a close contemporary of Apollodotus II, borrowed two of King Maues’ monograms: Apart from the monograms, the posteriority of Telephos is now attested by a bronze coin of this king overstruck on a coin of Archebius. The Greek power in Paropamisadae (ancient Afghanistan and Gandhara) came to an end with the Kushan (Yuezhi, nomads) invasion. Soon the territories around Taxila yielded to the IndoScythian Maues. Apollodotus II was the immediate successor of Maues and both reigned within a short lapse of time in the same region around Taxila. The monogram (like T) introduced by Maues, was taken by Telephos."" (New numismatic evidence on the pre-Kushan history of the Silk Road, Osmund Bopearachchi, C.N.R.S. Paris.)

The obverse side of this coin features the image of sitting Zeus, the Greek god, making a benediction gesture, which is a familiar icon of all coins issued by the Indo-Greek kings in this region. Obviously, the Greek symbol and script on the coin was essential for the currency to hold any monetary value for trade along the Silk Road.

On the reverse side of the coin, contrary to tradition, a naked Indian priest is featured sitting on an altar of stones and offering a fire sacrifice to the right, with a water-pot at his feet and cradling a walking stick over his left arm. It reminds of the ascetic brahman Vamana, who appeared in the legends in the Puranas, and stopped the aggressive conquest of India by the world conqueror Mahabali, an Asura King. Vamana, the Brahman in disguise, had suddenly appeared on the sacrificial altar holding in his hands the walking stick, an umbrella and a waterpot. (Bhagavata Purana, 8.18.23) This legend in the Puranas has more to tell about the story of Kalanus.

He is almost naked, with the traditional long, matted hair of an ascetic, and he carried a walking stick and a water-pot as specified in the Sanskrit Puranas. The Brahmans represented by this attire were Vedic scholars who worshipped the fire altar.

The Ashokan rock inscriptions (268-232 BC) confirm the existence of two types of ascetics in those days: “There is no country where these two classes, the Brahmanas and the Sramanas, do not exist, except among the Greeks.” (Hultzsch, Inscriptions of Asoka, 1913, rock edict 188.) The above rock inscription confirms that the icon on the coin was not a Greek priest but an Indian ascetic, which his name also confirms. Some scholars may disagree with this view, as the physical appearances of all Indian sadhus are similar. In this case, however, the identity of the sadhu who accompanied Alexander is indisputable, as the name of Kalana appears on the coin and, moreover, the coin was found at Taxila, where Alexander had camped for about 2 months, from 13 April to middle of June 326 BC. (Arrian, Anabasis of Alexander, 4.22; 5.3; Curtius, History, 8.12; Diodorus, History, 17.86; Plutarch, Alexander, 59, 65; Strabo, Geography, 15.)

The epithet embossed on the coin in Kharosthi script reads from right to left as “Maharajasa Kalana kramasa Telephasa.”

The image on the coin has perplexed scholars, because no other coin ever depicts the icon of an ascetic Brahman priest, on the side on which, notably, the local king’s image customarily appears. In the first century BC, the coins in this region used to portray the ruler on the obverse with a Greek legend, and a Hellenistic deity like Zeus on the reverse with a Kharosthi legend surrounding it.

The coins issued by the Indo-Greek king Menander of the Bactria, a neighbouring country to Taxila, had Greek gods on the reverse of the coins, with the king’s bust on the front. Zeus seated in a chair is very common, like that of King Antialkidas, who ruled from 115 to 95 BC and reigned from his capital at Taxila. The coin of Telephos is the only omission, depicting an Indian priest on one side instead of the image of the king.

The “Zeus enthroned” image is a common trademark of the coins minted at the Kapisa mint, (modern Bagram near Kabul) established by the Greek followers of Alexander the Great.

Several important conclusions can be derived from the image and the words embossed on this unique coin. The most notable information available from it is the appearance of the name Kalana, which reminds us of the name of Kalanus (Calanus, Ancient Greek: Καλανoς) in the records of the Greek authors, as the “s” in Greek is always silent. Incredibly, therefore, the coin portrays the name and the image of the naked philosopher, Kalanus, who had joined Alexander at Taxila as a gymnosophist and appeared at the concluding event of the Indian invasion on the altar.

Alexander himself had minted his coins while in Taxila, with the icon of the god Zeus on one side and the icon of Alexander on the other side. Later Indo-Greek had also followed this tradition, as the image of Alexander added monetary value to the coin. Shockingly, however, King Telephos had boldly replaced on this coin the image of Alexander with that of Kalanus. By ancient traditions, this was certainly audacious and yet outrageous.

Apparently, the Indian king was trying to give a political message to the opposing Indo-Greek kings ruling the neighbouring states, especially in Bactria and Sogdiana. Telephos was the first king to issue coins with Indian motifs in the region conquered by Alexander the Great. By introducing familiar Indian icons on his new coins, he was trying to restore the Indian legacy in the country of Taxila.

Notably, even the chiseled stone tablets on which the priest is sitting match with the historical records of Alexander’s altar stones, as historian Curtius notes: “The altar stones were built of hewn stone, as standing monuments of his expedition.” (Curtius, History, 9.19.) In the ancient mounds of Taxila, archaeologist have found burnt bricks, but not chiselled stones, which were the handiwork of the Greek masons, who alone had the iron tools in that epoch to cut hard rocks to shape. The largest durable building built in India after Alexander’s conquest was the Sanchi stupa, which was built in 250 BC with burnt bricks, and not using cut stones. Similarly, the large halls of the magnificent Mauryan palace at Pataliputra was built with wooden columns. Prior to 326 BC, in ancient India, as in Persia, the masonry was always made with burnt bricks. No known cut-stone structures exist anywhere in India prior to Alexander’s invasion. Therefore, the rectangular stone slabs depicted on the coin, on which Kalanus is sitting for the sacrifice, must have been cut to shape by sharp steel hammers wielded by Alexander’s masons.

Further, anyone familiar with the rituals of fire sacrifices (yajna sacrifice) in India would attest that the priest never sits on an elevated altar of stones. They always sit beside the elevated fire pit on the ground with their legs crossed. According to tradition, the sitting position of the master of the ceremonies (Yajamaan) should not be higher than that of the raised platform with the fire of Yajna sacrifice. (Rigveda: 10-88-19). “A comfortable sitting position is called Aasan” (Yog Darshan: Sadhna Paad: Sutra 46). The fire sacrifice itself is an Indian tradition. However, the fire sacrifice depicted on the coin, and the posture of the priest is notably different.

The Kharosthi legend on the coin reads from right to left: “Maharajasa Kalana kramasa Telephasa.” (Vincent A. Smith, Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, 1898, Numismatic notes and novelties No. III, p 131; See also “Emergence of Hinduism in Gandhara: An Analysis of Material Culture; Vorgelegt von, Abdul Samad, Kohat.)

The corresponding Greek legend on the other side of the coin reads: “Basileos Eyepgetoy Thlefoy.” As the Greek word eyepgetoy means “inherited divine power,” we can assume that the corresponding Kharosthi word kramasa on the other side of the coin also means eyepgetoy, or divine inheritance.

Moreover, in the Kharosthi, Sanskrit and Prakrit languages, the word kramasa means “as a consequence of, or inheritance.” According to the Sanskrit dictionary and the modern Malayalam language, the word krama-sa means “hereditary descent.”

According to scholars, the deities on the coin indicate the “dynastic lineage” of the local issuer. (R. C. Senior, Indo-Scythian Coins and History IV, Supplement, London, 2004, pp. xxvi-xxvii.)

Therefore, the Kharosthi monogram on the coin means: “King Telephos who inherits the lineage of Kalanus.” The Telephos coin, therefore, is one of the so-called pedigree coins often issued by Indo-Greek kings to claim their inheritance rights. Kings of neighbouring Bactria and the other Indian kingdoms usually proclaimed their lineage to their predecessors by striking such commemorative coins. The identification of this coin is an important discovery in the story of Alexander. This is an exciting finding that confirms the hypothesis that Kalanus helped to reinstate the throne of Taxila to the Indian King.

After Alexander’s invasion in 326 BC, the Greek Satraps controlled Bactria and the other kingdoms west of Taxila. Soon after Alexander left Taxila, Chandragupta Maurya usurped the throne of Taxila in 324 BC. His descendants, the Mauryas, ruled Taxila from 324 BC to 180 BC, ending with the reign of King Brihadrata Maurya. In 180 BC, Taxila was attacked by the Greco-Bactrian king from the Afghan side, Dharmamita or Demetrius, who was a descendant of the Greek rulers who came with Alexander to this part of the world. This is confirmed in the Indian Puranas also, as the Yuga Purana confirms that a Greek [Yavana] army under King Dharmamita [Demetrius] annexed the territories around Taxila and Punjab in the second century BC.

On checking the chronology of events, we find that shortly before King Telephos, a Greek king, Antialkidas, ruled Taxila in 110 BC. An inscription found on a stone pillar in central India, known as the Heliodorus Pillar, confirms this.

A decade before King Telephos, another Greek king, Hermaois of Taxila, had issued his coins in 90 BC, with the image of the king and his queen, Calliope. The subsequent coins of King Maues, who ruled Taxila, just before Telephos, featured Nike, the goddess of victory, or Buddha on his coins. Telephos, however, changed the icons of the deities and replaced it with the image of Kalanus.

King Telephos recaptured Taxila in 75 BC and issued the commemorative coin with the image of Kalanus, thereby claiming his Indian roots. The coins of Telephos and Maues, probably contemporaries, depict peculiar monograms which are not found on any other coins of the region. (Journal of the Asiatic society of Bengal (JASB), 1910, p. 146.)

Telephos, therefore, claimed his Indian heritage through the Kalanus coin.

This leads us to several fascinating conclusions. First, it confirms that Kalanus, a naked sadhu, lived in ancient Taxila, as recorded in the Greek texts. Second, the coin reveals that Kalanus held a sacrifice on an altar and heralded the liberation of Taxila from foreign rule. Third, on the widely circulated Greek coins of the age, the icon of Kalanus replaced the image of Alexander the Great. Forth, Kalanus had attained a divine status to be depicted on a coin in the region.

Finally, and most interestingly, the coin shows how Kalanus had acquired godlike stately eminence, as his icon was embossed on the side of the coin, where the Indian deities were being embossed by the other kings in the region. King Telephos struck a few other coins with Indian deities like goddess Lakshmi on the coins, proving that Kalanus was worshipped as a deity in Taxila. Apparently, the legends of the ascetic Brahman had acquired legendary proportions throughout the Indus valley. We might take this as indisputable evidence of the divine status of Kalanus and thus accept his mystic role in saving the world around the Indus from the invader.

The army rebellion

---------------------

After a restful stay in Taxila, after two months, by the middle of June 326 BC, Alexander confidently marched east toward the Jhelum River. Punjab, the land of five rivers, was now unpassable, as the rivers were inundated. Alexander’s army was immobilized. Arrian describes the night in which Alexander crossed the flooded Jhelum River, before the solstice on 21 June: “The noise of the storm, with the violence of the thunder and lightning, hindered the clashing of their armor and the voices of the commanding officers.” (Arrian, Anabasis of Alexander, 12.) The Greeks had never experienced anything like the monsoon thunderstorms, and they were trapped by the turbulent flood, unable to stay or to move on.

The soldiers were in distress, deprived of necessary clothing, shelter and food. They soon revolted, besieged by the worrisome climate. The rebellious soldiers held meetings throughout the camp, where some men resolutely refused to follow Alexander any farther. (Arrian, Anabasis of Alexander, 5.23.5.) Curtius records that Alexander spoke to his men thus: “I am not insensible, soldiers, that the Indians have within these few days spread several rumors on purpose to terrify you; but you do not need being told, how groundless such reports are.” (Curtius, History, 9.3.) The Indians had spread the news of the massive armies waiting for the battle, with thousands of elephants. Alexander was aware of this vicious campaign and could not persuade the army to stay calm.

The Greek generals, most of them childhood friends, (including Perdiccas, Nearchus, Ptolemy, Onesecritus, and Seleucus) seemed to be manifestly determined not to obey Alexander. The Macedonian commanders apparently agreed with the soldiers and probably steered the revolt against Alexander. Initially, not realizing the full import of the situation, Alexander is known to have said, “Let them grumble, so long as they obey.” But they refused to obey. Alexander soon realized with alarm that a mutiny was imminent and that he was alone in enemy territory.

It continuously rained in the monsoon season for about seventy days until the five rivers of Punjab were all in a wild rage. For safety, Alexander set up his camp on Dasuya Hill on the Beas riverside waiting for the torrential rains to subside. According to Strabo, “Aristobulus gives even the measure of the height to which the river rises twenty cubits [thirty feet] of measure of the water when it overflows the plains.” (Strabo, Geography, 15.1.18–19.)

The army struggled in the watery world, with the rivers overflowing everywhere. Most of his soldiers were weary and desperate to return home. (Diodorus, History, 17.94; Plutarch, Lives, 6; Strabo, Geography, 15.1.18–19.) Alexander was determined, however, and it appeared that nothing could stop him from marching to the east. The rains had then stopped, and the floods soon receded.

Alexander then summoned a meeting of his top generals to order them to start marching. Alexander asked them to speak first, but no one dared to speak to him. Below the calm stance was great concern and much fear. They stood together against him on this occasion and refused to be of any help. During the meeting, most of the officers were paralyzed with terror and remained silent, with their eyes steadfastly fixed on the ground. (Curtius, History, 9.3.2.) They appeared to lead the rebellion as a united force.

The meeting was a failure, as Alexander refused to accept their stubborn demands to return home. Still, Alexander was inflexible as usual in his resolve. “I observe that the officers no longer follow my orders with your old spirit,” he shouted in the last meeting. “I have now called this meeting so that we may come to a decision together: Are we, upon my advice, to march forward, or, upon yours, to turn back?” (Arrian, Anabasis, 5.28.1.)

Distressed, Alexander shouted at his men thus: “Those who wish to return home can do so and tell their countrymen that they deserted their king in the midst of his enemies. But tell them he did not force any Macedonian to accompany him against his will.” With visible rage, he then dismissed the council and leaped down from the podium. (Curtius, History, 9.3.18.)

Alexander was now stuck alone in enemy land, and he also knew he was in extreme danger from his own troops. In a nasty temper, he withdrew into the royal tent alone, into which he forbade anyone to be admitted. For two days he sulked in his hopelessness, but on the third day he ordered twelve altars of square stones to be erected to offer sacrifices, determined to proceed with the expedition. (Curtius, History, 9.3.18.) He decided to perform a sacrifice to the gods, and he hoped to receive favorable omens for the invasion of the rest of India.

The altar sacrifice.

---------------------

The rains had stopped by the middle of August, and the altars were built in a week’s time. Curtius records say that “the altars were built of hewn stone, as standing monuments of his expedition.” (Curtius, History, 9.3.19.) Before the sacrifice, Alexander again delivered a speech to his men trying to persuade the army to follow him. (Curtius, History, 9.2.34.) Arrian records his desperate mood, with Alexander pleading with his men not to desert him. (Arrian, Anabasis, 5.28.2.)

Alexander had few options now. He could not reprimand and punish his men for insubordination as it may erupt into violence. He could not also give in to their rebellious demands and threats, which they would take as his weakness. But he had found a solution to this. Since all Macedonians including the Greek priests were part of the revolt, he deputed Kalanus, a trustworthy associate, as the priest on the altar. Kalanus seems to have played a crucial role during the altar ceremony in Punjab. He had refused to meet any of the Greek Generals and priests for 3 days before the sacrifice, as he refused admission to all except his regular attendants. (Curtius, History, 9.3.18.)

Alexander stood motionless on the altar as Kalanus lit the sacrificial fire. Kalanus, apparently unattached to worldly matters, performed the sacrifices, as he was the only person whom Alexander could trust now.

To Alexander’s great relief, and as he expected, Kalanus declared the sacrificial omens unfavorable to proceed with the conquest.

To the soldiers watching anxiously for the final decision, Alexander announced his decision to halt the campaign and to return home. Arrian records that “then the soldiers shouted as a mixed multitude would shout when rejoicing; and most of them shed tears of joy.” (Arrian, Anabasis, 5.24.)

Kalanus tactfully advised Alexander with a textbook illustration on how to successfully govern a huge empire. This event eventually helped to change the inflexible resolve of Alexander and altered the course of world history.

The following paragraph from the Roman biographer Plutarch reconfirms our assumption that the story of Kalanus is a realistic historical event that ended the Greek invasion of India.

Plutarch (Plutarch, Alexander, 64.6.) describes the incident thus:

"It was Kalanus, who laid before Alexander the famous illustration of governing a huge empire. It was this. He spread down upon the ground a dry and shriveled hide and set his foot upon the outer edge of it; the hide was pressed down in one place but rose up in others. He went all around the hide and showed that this was the result wherever he pressed the edge down, and then at last he stood in the middle of it, and lo! It was all held down flat and still. The similitude was designed to show that Alexander ought to put most [of his] attention upon the middle of his empire and not wander far away from it."

This could have happened only on the Altar during the sacrifice, as Alexander was considering his next move. “How far further can you go, Alexander?” the priest asked.

Alexander watched the Indian priest measure few steps on the floor, symbolically marking the boundaries of his empire, and he accepted his advice to return to the center of his empire, rather than roaming farther ahead to its extreme boundaries. (Plutarch, Alexander, 64.6.) It appears that Alexander patiently listened to the Brahman priest as he explained to the king the art of kingship.

Until this day, at every other sacrifice, the priests had pronounced favorable omens, auguring great successes for Alexander. On the banks of the Beas River, however, Alexander’s fortunes fortuitously turned adverse, because of Kalanus.

Subsequent events confirm that Kalanus saved Alexander from the revolt and also protected India from the conqueror. It appears Kalanus attained divine status as the Indians venerated the site of the altar for centuries afterward. As Plutarch notes in Morals, “We are told that the first emperor of India, Chandragupta, who succeeded to the lordship of Alexander’s conquests, and his successors for centuries afterwards, continued to venerate the altars, and were in the habit of crossing the river to offer sacrifice upon them.” (Plutarch, Morals; Henry Frowde, Early History of India, London: Oxford, 1904.) In Lives, Plutarch says that “Alexander also set up altars, which even to the present day are reverenced by the kings of the Prachi [Magadha], who cross the river to them, and offer sacrifice upon them in the Greek fashion.” (Plutarch, Alexander, 6.62.) The Indian kings were paying homage to Kalanus at the altar, as presented on the Telephos coin.

On 24 August 326 BC, for the first time in his eventful career, Alexander the Great stopped and turned back. (Ajith Kumar, The Murder of Alexander the Great, Book 2: The Puranas.)

After the altar ceremony, Alexander told General Ptolemy, “Since all things conspired to hinder further progress, I am determined to return.” (Arrian, Anabasis, 5.28.4.) Alexander also dedicated and installed a pillar with an inscription: “Here Alexander stopped.” (Philostratus, Life of Apollonius.) This likely marked the end of his military career, as he did not successfully win any major battles after this.

Kalanus, the Indian Ascetic, tricked Alexander.

As we have noted earlier, Plutarch confirms that Taxiles, the king of Taxila, persuaded Kalanus to join Alexander’s camp: “As to Kalanus, it is certain that King Taxiles prevailed with him to go to Alexander. It was Kalanus, as we are told, who laid before Alexander the famous illustration of government.” (Plutarch, Alexander, 65.5.)

Kalanus wanted Alexander to abort his war plans and return from India. The demonstration with the goat skin was intended to persuade Alexander to stop the war and withdraw to the center of his domains. The Telephos coin confirms the role played by Kalanus, as the King of Taxila embossed the words “Maharajasa Kalana kramasa Telephasa.” The freedom of Taxila was a divine gift from Kalanus.

In those chaotic days of distrust and revolt, one of the few people who had access to the emperor was Kalanus, who was officially a soothsayer and philosophical adviser to the king. Alexander’s regular Greek priest, Aristander, had been dismissed a few months earlier while crossing a river in Afghanistan. Aristander had refused to obey the king and review an adverse religious forecast, as Alexander desired, to cross the Jaxartes River. Having failed to forecast favorably, Alexander had ordered him to repeat another sacrifice, which he did hesitatingly, but again the sacrifice resulted in an unfavorable omen. Alexander rebuked Aristander for failing to obey his instructions. (Arrian, Anabasis, 4.4.3; 4.4.9; Curtius, History, 7.7.8; 7.7.22.)

Whenever he was determined to proceed with a campaign, Alexander normally commanded a priest to perform another sacrifice to obtain a more favorable result. However now, since the Macedonian priests were also part of the revolt, Alexander could not trust them, and so Kalanus was ordered to conduct the ceremonies for Alexander: a fact the Telephos coin attests. Kalanus was amicable to Alexander’s fickle demands. Kalanus, as expected, faithfully executed the king’s wishes. Alexander eagerly accepted the unfavorable omens Kalanus announced, which helped to publicly justify Alexander’s decision to return from India. With Kalanus’s help, he diplomatically appeased the mutineers without surrendering to their demands.

Significantly, the Telephos coin and the note from Plutarch proves that Kalanus had a key role to play in the history of Alexander. Kalanus appears to have had serious discussions with Alexander on the eminent issue of invading India, as the demonstration on the skin showed. Alexander had several experienced generals to recommend on such important matters. Yet, it appears that the Indian Brahman had significant influence and equal authority to advise the world emperor on matters of state in such a critical situation.

Unfortunately, on that historic day, on the altar, while the sacrificial fire fumed and the solemn prayers concluded, Alexander’s quest for a world empire came to a sudden and surprising end. The king of Taxila had reasons to rejoice and issue a commemorative coin in the name of Kalanus.

According to the historian Ptolemy, Alexander then called together those who were closest to him, and because everything was concluded against his wishes, he declared to the army that he intended to return. It was a mystical moment that would be remembered for ages by the soldiers who witnessed it. Hesitantly, Alexander ordered his men to prepare for the long march back home, but their problems were far from over. Alexander was not going back via the mountain route he had come. He was going to Patala, a remote hell, at the southernmost corner of the inhabited world.

This is attested by the Puranas. After the altar sacrifice the Brahman escorted the conqueror to Patala. “Oh, King of the Asuras, I will stay with you, as the gatekeeper of the city of Patala in the realms of Sutala.” (Bhagavata Purana, 8.22) According to Indian folklore, Patala was at the furthest southern end of the Aryan domains, and it formed the realms of the netherworld, hell itself.

According to Greek records, also Kalanus subsequently led Alexander to Patala. (Greek: Patelene, Pattala.)

On the altar in Kurukshetra, Alexander inadvertently followed the advice of the most dangerous opponent he had ever faced. He was unarmed and pious, and beyond any suspicious attributes of an enemy. He had lead Alexander into a death trap at the furthest corner of the primitive world at Patala at the mouth of the Indus, where Alexander was trapped for about 6 months. In the Indian texts, Patala was the netherworld ruled by the demons. (Ajith Kumar, The Murder of Alexander the Great, Book 2: The Secret War.)

Once he reached there, Alexander was stuck at Patala, as it was surrounded by two large deserts, the Gedrosian desert and the Rajasthan desert. There were no easy exits from Patala. An army could easily sail on the Indus River into Patala from the north, but once in Patala, the place is a cage with no easy exits on any side. In every direction, the country is deserted and empty. The Indus is sandwiched between the Thar Desert in the east and the mountainous Gedrosian Desert in the west. The ocean roars in the south, and the Indus River flows down from the north.

The Indians had led him into a dead end. As he had no other choice, he made himself the king of Patala and made it his capital for about six months. “Alexander had to wait for the monsoon winds to change direction in winter to allow his fleet to sail into the Arabian Sea. He also could not return to Taxila, as the Indus River had been in flood since the end of June because of the annual monsoon rains.” (Ajith Kumar, The Murder of Alexander the Great, Book 1: The Puranas.) Arrian says that Patala was an uninhabited region, which was waterless, and the army had to dig wells to render the land fit for habitation. (Arrian, Anabasis, 6.28.)

Without doubt, the real Kalanus was also an actor, a decoy, whom Alexander naively accepted as a reliable guide. The unexpected developments on the altar, and the unnecessary trip to the dead end at Patala, indicate that a secret war had been unleashed against the invader and the king’s days were numbered thereafter.

The cumulative evidence thus leads to the conclusion that the Telephos coin records the climax of the drama on the altar, where, after symbolically measuring a few steps on the ground, the sadhu Brahman miraculously ended the imperial ambitions of Alexander the Great.

The Peutinger map

----------------------

The Peutinger Map was made over a period of several years in the first century BC, to mark the Roman roads that led to the far-flung global colonies. It mapped an area roughly from southeast England to present day Kochi in south India. The Roman emperor Augustus created this earliest sketch of the world. The emperor ordered it to be engraved on a marble top and set it up in the Porticus Vipsania in Rome in 12 BC. (Pliny, Natural History, 3.17.)

The altars of Alexander are marked on the map, with two icons in northern India, east of Taxila, where Kalanus performed the sacrifice.

An unusual label on the map proves that the cartographers remembered the historic moment on the altar even after 300 years when they carved the words on the marble top. The legend on the map said in ancient Latin: “Here Alexander accepted the oracular advice to the question: How far can you go, Alexander?”

These were the same concepts in words spoken by Kalanus during the goat skin demonstration, as attested by Plutarch. (Plutarch, Alexander, 64.6.)

This sentence is the most significant piece of evidence, literally carved on stone, that proves that Alexander aborted his military campaign on the advice of the sadhu Brahman Kalanus. With these firm words of advice, Kalanus helped Alexander to end his invasion of India. As we know, “Here Alexander stopped.” (Philostrautus, Life of Apollonius.)

Unbelievable though it may be, the Peutinger Map confirms that the Brahman depicted on the Telephos coin persuaded Alexander to stop his military campaign in India.

The end of Kalanus

----------------------

The suicide of Kalanus is recorded by several ancient historians. (Diodorus, History, 17.107; Strabo, Geography, 15.1.68; Plutarch, Alexander, 69.3; Arrian, Anabasis, 7.3.)

“In Persia, too, Calanus, who had suffered for a little while from intestinal disorder, asked that a funeral pyre might be prepared for him. To this he came on horseback, and after offering prayers, sprinkling himself, and casting some of his hair upon the pyre, he ascended it, greeting the Macedonians who were present, and exhorting them to make that day one of pleasure and revelry with the king, whom, he declared, he should soon see in Babylon. After thus speaking, he lay down and covered his head, nor did he move as the fire approached him, but continued to lie in the same posture as at first, and so sacrificed himself acceptably, as the wise men of his country had done from of old. The same thing was done many years afterwards by another Indian who was in the following of Caesar, at Athens; and the "Indian's Tomb" is shown there to this day. But Alexander, after returning from the funeral pyre and assembling many of his friends and officers for supper, proposed a contest in drinking neat wine, the victor to be crowned. Well, then, the one who drank the most, Promachus, got as far as four pitchers; he took the prize, a crown of a talent's worth, but lived only three days afterwards. And of the rest, according to Chares, forty-one died of what they drank, a violent chill having set in after their debauch.” (Plutarch 7.69)

Plutarch’s testimony says: “Then he lay down and covered his head and did not stir at all when the flames swallowed him, and he perished.” (Plutarch, Alexander, 69)

In the whole history of humanity, we have not found anyone else capable of burning alive without flinching. How could the sparks of the flames have silenced the reflexes when the whole body is on fire? This does not seem to be realistic.

Kalanus’s self-immolation establishes that he likely had taken poison of some kind, as he did not move at all when the flames engulfed him.

Further, he did something more mysterious before climbing onto his funeral pyre.

Arrian records the suspicious incident:

"Also concerning Calanus, the Indian philosopher, the following story has been recorded. When he was going to the funeral pyre to die, he gave the parting salutation to all his other companions; but he refused to approach Alexander to give him the salutation, saying he would meet him at Babylon and there salute him. At the time indeed this remark was treated with neglect; but afterwards, when Alexander had died at Babylon, it came to the recollection of those who had heard it, and they thought forsooth that it was a divine intimation of Alexander's approaching end." (Arrian, Anabasis, 7.18.)

Kalanus refrained from bidding farewell to Alexander, his well-wisher. His last emotionless words to the few people surrounding him were, “I shall certainly meet the King again in Babylon.” It seemed he predicted the premature death of Alexander at the age of 32. Kalanus seemed confident about what awaited the emperor in the coming days, as if he could foretell the future. Maybe he could.

Kalanus declared the last words of a victor who was ending his campaign on a happy note. After predicting Alexander’s untimely death, Kalanus climbed on the burning pile of wood and remained silent. We can conclude that Kalanus had specific information about the pending plot against Alexander. Kalanus certainly knew Alexander would be killed, and he had foretold the time and place of his death.

The mystery did not end with the suicide of Kalanus. Further, on the day Kalanus committed suicide, the Greek historians reported a far more bizarre incident: forty-one soldiers also died soon after Kalanus burned himself on the pyre.

This incident was quoted by the orator Athenaeus in his work Deipnosophistae: "Then Alexander instituted a contest in athletic games and a musical recital of praises for Kalanus. 'And he instituted,' Chares says, 'because of the love of drinking on the part of the Indians, also instituted a contest in the drinking of unmixed wine, and the present for the winner was a talent, for the second-best thirty minas, for the third ten minas. Out of those who drank the wine, thirty-five died immediately of a chill, and six others shortly after in their tents. The man who drank the most and came off victor drank twelve quarts and received the talent, but he lived only four days more; he was called Champion.' (Athenaeus, Deipnosophistae, 4.49, FGrH, 125 F19a.)

Plutarch calls Chares a royal usher or chamberlain (someone who entertained court visitors), so his notes are reliable personal accounts of the tragic incident. (Plutarch, Alexander, 46.)

This is what happened according to Plutarch:

"Alexander, after returning from the funeral pyre and assembling many of his friends and officers for supper, proposed a contest in drinking neat wine, the victor to be crowned. Well, then, the one who drank the most, Promachus, got as far as four pitchers; he took the prize, a crown of a talent's worth, but lived only three days afterwards. And of the rest, according to Chares, forty-one died of what they drank, a violent chill having set in after their debauch."

Forty-one soldiers died after suffering for a few days from something like a fever. Their deaths were not sudden, but slow. From the symptoms of the victims, it is clear that the brew contained a peculiar type of “slow” poison that took effect gradually. This observation is vital to the history of Alexander because, while analyzing Alexander’s death, Greek historians claimed that they were unaware of a poison that could act this slowly. The toxin in the wine had also induced peculiar symptoms, as “most of them had fever.”

Alexander did not drink the same wine, but he was now a marked victim. As predicted by Kalanus he died a few months later at Babylon, with the same symptoms due to a slow poison named in the Sanskrit Puranas as the “destroyer of Time.” (Ajith Kumar, The Murder of Alexander the Great, Book 2: The Secret War.)

In Morals, Plutarch wrote: “Aristobulus says that he had a raging fever, and that when he got thirsty, he drank wine, whereupon he became delirious, and died on the thirtieth day of the month Daesius.” (Plutarch, Morals, 337.)

Death came as a final relief to Alexander, with his jaws locked and eyes staring, but fully aware of his surroundings holding the terror within. In the evening of 10 June 323 BC, Alexander, the King of the World, died quietly without a murmur after ten days of silent agony. Historian Justinus said what many historians felt: “He was overcome at last, not by the prowess of any enemy, but by a conspiracy of those whom he trusted, and the treachery of his own subjects.” (Justinus, Epitome, 12.6)

Plutarch wrote about the rumors: “At the time, nobody had any suspicion of his being poisoned, but upon some information given six years after, they say Olympias put many to death, and scattered the ashes of Iolaus, then dead, as if he had given it him. But those who affirm that Aristotle counselled Antipater to do it, and that by his means the poison was brought, …… gathered like a thin dew, and kept in an ass's hoof; for it was so very cold and penetrating that no other vessel would hold it.” (Plutarch, 77)

Who killed Alexander the Great? The true history of Alexander the Great has never been convincingly narrated. Even after two millennia, the mystery surrounding his premature death at the prime age of 32 remains unresolved. It appears, however, that the Puranas, the ancient Indian Sanskrit texts, hold solemn secrets which could settle the archaic mystery surrounding Alexander’s death.

The Sanskrit word “Purana” literally means “old stories.” The puranic literature includes eighteen Puranas, two epics (Mahabharata and Ramayana) and several commentaries. These sacred texts contain ancient Indian history, religious instructions, and fascinating folk tales. They are also encyclopaedic texts that contain itihasa, or the history of the Indian dynasties which ruled the Aryavartha, the land of the Aryan tribes, for almost 5,000 years.

A popular legend in the Puranas narrates the story of the Greek conquest of the Indus Valley and unveils the covert strategy that led to the rapid return march and the early death of the world conqueror, Alexander. Unfortunately, scholars have not studied these Sanskrit manuscripts in relation to Alexander the Great, mainly because his name is not identifiable in these primeval scriptures. Nevertheless, the historians consider the narrative in the Puranas a highly valuable history because it provides the list of 153 ancient kings who ruled India for more than 5,000 years. (Pargiter, Ancient Indian Historical Tradition, 1922; Vishnu Purana, part IV, section I and section VI.)

The Bhagavata Purana (8.18) portrays the legends of the ‘world conqueror’ who aborted his Indian conquest on the advice of a Brahman ascetic on the altar in Punjab. It has the same narrative sketch and the surprising ending as on the altar of Alexander with a Brahman acting as the priest.

The altar ceremony conducted by the world conqueror is described in many Sanskrit texts. During the altar sacrifice, the Puranas even record the lion emblem on the Grecian flag and the color of Alexander’s famous horse Bucephalus, which were identifiable royal icons of Alexander.

The Bhagavata Purana describes with exciting clarity the horse and the royal emblem of the conqueror: "Thereafter, a chariot wrapped with gold and silk, a bay horse with reddish brown color, and a flag displaying the emblem of a lion, appeared in the light of the blazing flames while offering ghee to the sacrificial fire." (Bhagavata Purana, 8.15.5.)

The reddish-brown color of the bay horse is unmistakable in the Alexander Mosaic, which was found in the House of the Faun in Pompeii, installed around 200 BC. The other proof available in the Purana is again undeniable, and perhaps irrefutable; it declares the national identity of the emperor, with the famous Macedonian lion emblem. The Puranas say that the conqueror carried the lion flag, the iconic royal emblem of the king of Macedonia.

An ancient carnival on the Malabar coast in south India, known as the “Onam” festival, recounts these ancient tales and provides the primary key to resolve the age-old mystery behind Alexander’s death.

Kalanus thus played a significant role in the “The Secret War” against Alexander. The Telephos coin, the Peutinger map, the death prediction by Kalanus and Plutarch’s testimony regarding the slow poison suggest that Alexander was murdered. The Puranas even identify the weapon as the “Destroyer of Time.”

Further reading:

"The Murder of Alexander the Great: Book 1 - The Puranas." - https://www.amazon.com/dp/0999071416

"The Murder of Alexander the Great: Book 2 - The Secret War."- https://www.amazon.com/dp/0999071440

---------------------------------------------------

The Puranas

The Secret War

Ajith Kumar.

(These research notes were prepared for my 2 books - “The Murder of Alexander the Great, Book 1: The Puranas” and “The Murder of Alexander the Great, Book 2: The Secret War.”) Available on Amazon.com.

--------------------------------------------------------

Kalanus (Calanus, Greek : Kalanos, Sanskrit/ Kharosthi: Kalana), the mysterious ascetic Brahman from Taxila who accompanied Alexander the Great throughout his campaign in India, is familiar to historians. Kalanus gained a reputation as an oracle and a philosopher (sophist) in Alexander’s camp. The Greek historians called him a gymnosophist, meaning a “naked philosopher.” The classic sources called him a Brahman, as he was a member of the priestly caste, who advised the King on political matters.

Arrian wrote: “I have mentioned Kalanus because no history of Alexander would be complete without the story of Kalanus.” Plutarch points out the “attentions which Alexander so lavishly bestowed upon Dandamis and Kalanus.” (Plutarch, Lives, 8.5)