Madeline Miller's Blog, page 8

February 6, 2012

Myth of the Week: Pyrrhus, Part I

Monday, February 6th, 2012

It is one of the oldest stories: a famous and powerful man has a son. The son grows up. How will he interact with his father's reputation? How will he define himself as his own man? It was an even more fraught question in ancient Greece, where no matter how famous a man became, he was called not by his own name, but by his patronymic (his father's name plus an ending that meant "son of"). So, even though Achilles' fame far surpassed his father's, he was still referred to as "Pelides" (son of Peleus). Comparison was inescapable, stitched into one's identity.

In the stories of the Trojan War, there is a trinity of sons who grow up in the shadow of intimidating paternal legacies: Telemachus, son of Odysseus; Orestes, son of Agamemnon; and Neoptolemus, son of Achilles. All of their stories are worth telling, but I thought I'd start with Neoptolemus (also called Pyrrhus).

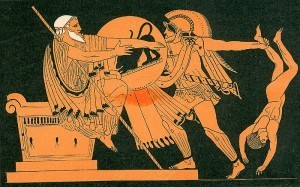

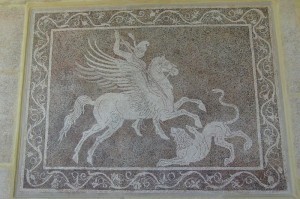

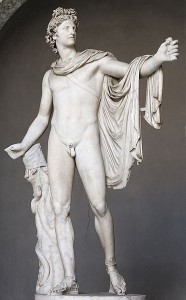

Pyrrhus/Neoptolemus, the son of Achilles. Photo credit: Zafky

One of the strangest things about Neoptolemus is the fact that there seem, in the myths, to be two of him: two mutually exclusive versions of his story, each championed by a master poet, Vergil and Sophocles. In one, Neoptolemus is a sadistic perversion of his father's legacy, heir to his strength and capacity for violence, but not his humanity; in the other, he is a heroic young man, struggling to do the right thing. Generally, Vergil's portrait, from book II of the Aeneid, has proved the more lasting, so that is where I will start.

Achilles' sea-nymph mother, Thetis, desperate to keep her son from an early death at Troy, dressed him as a woman and hid him on the island of Scyros, in the court of King Lycomedes. But Lycomedes' daughter, Deidameia, discovered the fraud, and she and Achilles conceived a child—Neoptolemus. Shortly thereafter, Achilles was found out, and sailed for Troy, leaving his wife and unborn child behind, for good.

Achilles being discovered in a dress on Scyros, as he seizes a shield. From a fresco at Pompeii

Neoptolemus grew up with a head of red-gold hair, and so earned the nickname Pyrrhus (fiery, the same root as the word pyre). Of his childhood, we know little other than that he was raised on Scyros by his mother and grandfather, with help from Thetis. Like his father, he was named in a prophecy: Troy would never fall unless Pyrrhus came to fight for the Greeks. When his father was killed in the tenth year of the Trojan War, Pyrrhus sailed for Troy. If the timing seems off to you, it is—even if we give Achilles a few years to get to Troy, Pyrrhus should still only be around twelve, absolute maximum.

All I can say is: that is one creepy twelve-year-old. When he gets to Troy, Pyrrhus takes his father's place as one of the most terrifying and reckless warriors of the Greeks. He is among those in the Trojan Horse, and according to the Odyssey, the only one who isn't afraid of being caught. Once inside the city of Troy, he uses an ax—Shining style—to tear his way into Priam's palace, leaving a bloody trail behind him.

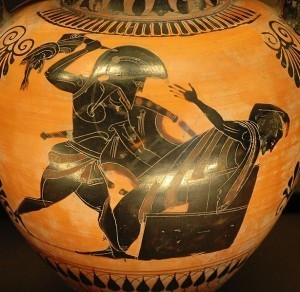

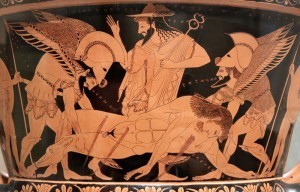

Pyrrhus attacking King Priam, on the altars

One of the things that I love about Vergil as an author is his profound humanism. Even his so-called villains are worthy of sympathy and understanding—all, that is, except for Pyrrhus. With Pyrrhus, Vergil seems to be doing something else entirely: creating a person with no ability to pity or empathize with others. It is, as far as I can tell, the first depiction of a sociopath in Western literature.

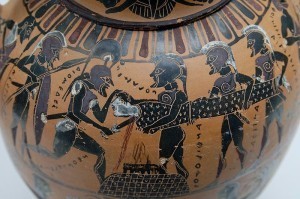

Once inside the palace, Pyrrhus chases down the Trojan prince Polites, killing him in front of his father, the aged King Priam, who has taken shelter at the household alters. The old king, in one of the most moving moments in the Aeneid, rises, trembling with grief and age, to deliver a ringing speech that calls down the wrath of the gods upon Pyrrhus for his double blasphemy: killing a son in front of his father, and defiling a sanctuary. As a further reproach, he compares him to his father, unfavorably: "Not even Achilles behaved so to me. He knew how to respect the laws of the suppliant; he returned my son's body to me, and sent me safely home again." This is a reference to the famous scene in the Iliad where Priam goes to Achilles' tent to beg for Hector's body, and Achilles relents–a shining moment of mercy and hope in an otherwise bloody work.

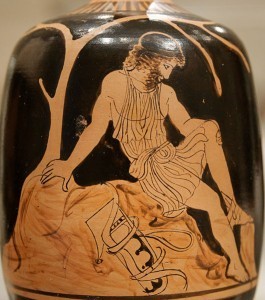

Priam begs Achilles for Hector's body

But you cannot shame a man like Pyrrhus. His response is sneering contempt: "You can go tell my father about my disgraceful deeds yourself. Now, die!"

He seizes the old man by his hair, and drags him, slipping in the blood of his son, to the altar to dispatch him. Later we hear that Priam's body has been left on the shore, missing its head, for the animals to eat. It is not enough for Pyrrhus to have killed him, he must also dishonor him—mutilating his body and depriving his soul of its eternal peace. The hope kindled in the meeting between Achilles and Priam is snuffed, utterly, by the son.

Pyrrhus killing Priam on the altars, with Hector's baby son, Astyanax, as a club.

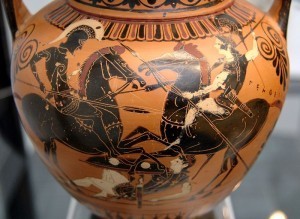

Sadly, that is only the beginning. After killing Priam, Pyrrhus goes in search of Andromache, Hector's wife. When he finds her, he seizes from her arms her infant son, Astyanax, and smashes his brains out against the wall. (In fact, in some lurid versions of the story, he uses the baby's body to club the grandfather Priam before killing him.) Andromache herself he takes captive, as his slave-wife. It is a horrifying cruelty: forcing her to share the bed of the man who murdered her son, and whose father murdered her husband. Then, before returning to Greece, Pyrrhus sacrifices the princess Polyxena on his father's tomb.

Perhaps it will be no surprise to hear that such a violent man comes to a violent end. Pyrrhus, upon returning to Greece, decides that no bride is worthy of him except for the daughter of Helen herself, Hermione—even though she is already betrothed to Orestes. Rather than wooing her, or trying to negotiate with her father, Pyrrhus presses forward with his usual method: force. He abducts the girl, and rapes her.

Pyrrhus sacrificing the Trojan princess Polyxena. Photo by Marie-Lan Nguyen

One of the things that is most disturbing about Pyrrhus' story is that his victims are not, as his father's were, fellow warriors. There is no Memnon here, no Hector, no Penthesilea. Instead we have people who are powerless: infants, the elderly, women not trained in combat. Vergil's point isn't, I think, that Pyrrhus is a coward–we see his fearlessness and ferocity in the sack of Troy– but that he's unnatural. The things which would normally arouse pity in us mean nothing to him. This makes him a very different kind of villain from someone like Agamemnon, whose faults we recognize: selfishness, cowardice, pride, petty brutality. To me, Pyrrhus is a far more frightening figure, a man who is moved by no boundaries or bonds of affection, who acknowledges no limitation on his behavior. The world is made up only of his own strength and everyone else's weakness.

So who, then, finally stops this unstoppable force? In some versions of the story it takes the god Apollo himself. But in Vergil's version, it's Orestes, Agamemnon's son, enraged at the violence done to his fiance. Pyrrhus has finally crossed the wrong person, and Orestes cuts him down. A satisfying end, and an interesting one too: Agamemnon and Achilles' feud has repeated itself in the next generation–only this time, at least for me–with the sympathies reversed.

By the way, at Pyrrhus' death Andromache is freed and, with her brother-in-law Helenus, able to found a new city in Troy's image, and live out her life in peace.

Coming on Wednesday: Pyrrhus, part II, the son Achilles would have been proud of.

January 30, 2012

Myth of the Week: Penthesilea

Monday, January 30th, 2012

My students often tease me that every mythological character is "one of my favorites." But, really, this week's character is: Penthesilea, Queen of the Amazons.

The Amazons were a legendary race of warrior women who lived somewhere in the region of the Black Sea (sources differ as to exactly where). There were a number of popular stories about them—that they were daughters of Ares, that no men were allowed in their camp. But the most famous of all is the one about their chest: that, in order to be able to wield a bow better, they would cut off one of one of their breasts. The story gained traction from some ancient etymologists, who claimed that the word Amazon derived from "a" (without) and "mazon" (breast, the same root as the "maste" in mastectomy).

An Amazon

As I child, I remember goggling at the breast story with horrified admiration. Those Amazons sure were committed to their archery! Now, of course, it seems absurd. As Olympic-level female archers the world over can testify, breasts do not interfere with shooting a bow. Surely the Greeks would have known that? But perhaps not—perhaps there simply weren't enough female archers in the ancient world to disprove it. And part of me can't help but wonder if the story wasn't on some level meant to discourage women from taking it up—sorry, you'll have to cut off your breast first.

Penthesilea, Amazon Queen

The Amazons had a number of famous Queens, but Penthesilea is perhaps the most storied. She was a daughter of the war-god Ares, and Pliny credits her with the invention of the battle-ax. She was also sister to Hippolyta, who married the hero Theseus, after being defeated by him in battle. Penthesilea ruled the Amazons during the years of the Trojan war—and for most of that time stayed away from the conflict. However, after Achilles killed Hector, Penthesilea decided it was time for her Amazons to intervene, and the group rode to the rescue of the Trojans—who were, after all, fellow Anatolians. Fearless, she blazed through the Greek ranks, laying waste to their soldiers. I love Vergil's glorious description of her in battle:

"The ferocious Penthesilea, gold belt fastened beneath her exposed breast, leads her battle-lines of Amazons with their crescent light-shields…a warrioress, a maiden who dares to fight with men."

(By the way, the word that Vergil uses for warrioress is bellatrix, the inspiration for Bellatrix Lestrange's name in Harry Potter.)

A Renaissance representation of Penthesilea

I can still remember the moment in my high school Latin class when I first translated those lines. I had heard of Penthesilea and the Amazons before, but this was the first time I really understand just how impressive and unusual it was in the ancient world to be a woman who "fights with men." The heroines of Greek mythology tend towards thoughtfulness, fidelity and modesty (Andromache, Penelope), while the daring and headstrong personalities generally go to the antagonists–Medea, Clytemnestra, Hera. But Penthesilea is something else entirely: a woman who meets men on her own terms, as their equal. Perhaps in honor of this, Vergil doesn't give her the standard heroine epithet of "beautiful." For him, it is her majesty and obvious power that make her notable, not her looks.

Sadly, Penthesilea's story ends in tragedy, at the hands of none other than Achilles himself. The most popular version of it is quite strange–that Achilles falls in love with her as he stabs her, catching her tenderly, even as she collapses to the ground. I have never been sure how to take this–is it a compliment to her spirit? Or is it an indignity–Achilles turning the warrior back into a woman? It all depends upon the telling, of course. But I like to think that maybe Achilles sees in her a sort of kindred spirit–another fierce and flashing youth, proud and driven towards honor. But he is so absorbed in his own drama that he realizes it, alas, a moment too late.

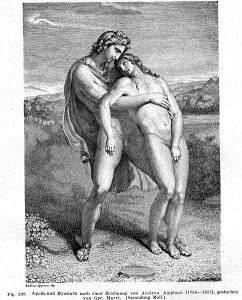

Achilles, love-struck, catches the dying Penthesilea

A broken statue of Achilles catching Penthesilea. I took this picture myself at the Aphrodisias museum, in Turkey.

Contrary to popular belief, Penthesilea's story isn't actually told in the Iliad (which ends with Hector's funeral, before the Amazons arrive), but in a lost ancient epic called Aethiopis. This poem continued the story of Achilles' great deeds, which included the killing of several famous warriors—Memnon, King of Aethiopia, and Penthesilea most prominent among them.

It is unsurprising that such a vivid character had a long legacy in art and literature–first and foremost as the inspiration for Vergil's great female warrior, Camilla, in the Aeneid. Penthesilea's name became synonymous with female strength; when Eleanor of Aquitaine accompanied her husband on the second crusade, she is rumored to have attired herself as the famous Amazon. As far as I can find, there aren't any novels focused on Penthesilea's story, but she does appear in several poems (including one by Robert Graves, author of I, Claudius and Hercules My Shipmate). If any one knows a story centered on her, drop me a line!

Achilles and Penthesilea ride into combat with each other.

A final story about Amazons. When I was in college, I volunteered to teach mythology to fifth graders. One day, I told the students a number of myths, the Amazons included, and then had them pick one story and draw a picture of it. Going around the room, I saw lots of Pegasuses, Heracleses, and Minotaurs. So I was excited when I noticed that one boy had drawn a very buff looking Amazon, wielding a bow. At her feet was a round object.

"What's that?" I asked.

"That's the breast she just cut off," he answered.

"Oh!" I think I said. "Very vivid!"

On that note, have a wonderful, and mythological, week!

January 23, 2012

Myth of the Week: Pegasus and Bellerophon

Monday, January 22nd, 2012

Last week I talked about Medusa, from whose neck the winged horse Pegasus was born. This week, I thought it would be only fitting to return to Pegasus' story, along with his most famous rider, Bellerophon. As I sat down to write, my significant other Nathaniel (a fellow myth-lover) told me that Pegasus and Bellerophon was one of his favorite myths, and offered to do a guest post for the week. I happily accepted–though you see I couldn't resist adding a few of my own thoughts at the end. Take it away, Nathaniel!

"As a child, there was no one in Greek myth I envied more than Bellerophon. You may not have heard of him—he doesn't have the name recognition of a Heracles or a Theseus. But you've heard of the reason I envied him: Pegasus.

Pegasus Vase-Painting, image from theoi.com

To befriend a horse, to tame him, and to ride: this is the fantasy that countless novels and movies are made of. So what could be more thrilling than a horse that could go even further, bear you beyond the bounds of gravity itself? Perseus may have had winged sandals, but they were nothing compared to the visceral pleasure of a living, breathing companion that could lift you into the sky.

Bellerophon came to Pegasus from a typically nasty Greek myth situation. Born in Corinth to King Glaucus (or sometimes the god Poseidon), Bellerophon accidentally killed a man, and found himself exiled to the court of King Proitos—where he was then falsely accused of rape by the Queen. Proitos packed him off to his father-in-law, King Iobates in Lycia, bearing a sealed message with instructions that he should murder Bellerophon immediately upon arrival. But Iobates was reluctant to do the deed himself, fearing the wrath of Zeus, and so sent Bellerophon off to fight, and be killed by, the local rampaging monster: the Chimera.

The fearsome Chimera

One of the wonderful things about Greek myth is that the monsters tend to combine primal terror with a touch of total absurdity. Take Medusa: a woman whose gaze turns you to stone. In this we can see ancient fears about female power and sexuality—the ability of a woman to rob a man of his will with a glance. Snakes too, are primal horrors. But snakes for hair? This seems to invite all sorts of overly literal question like: Does she have to give them haircuts? Do they bite her? Does she have to feed them separately?

Similarly, the Chimera: a fearsome lion-headed creature that breathes fire, with a snake for a tail. If the ancients had stopped there it would have been all right. But they didn't. For along with its lion-head and snake-tail, the Chimera has a goat head sprouting from its middle (see above). Yes, a goat, that fearful predator that haunted the sleep of dawn age humanity. The Oxford Classical Dictionary notes that the goat "may be made less risible by allowing it to perform the fire-breathing." Fear the now less-risible goat! But I suppose the very improbability of this combination is part of what makes the Chimera frightening: it's a loathsome hybrid, a perversion of all logic and natural order.

In despair at ever defeating such a thing, Bellerophon went to sleep in Athena's temple, hoping for the goddess' advice and aid. She appeared to him in a dream, and told him where he might find the horse Pegasus. When he woke, there was a golden bridle waiting at his side.

If ever a horse deserved gilded tack, it's Pegasus. With it, Bellerophon was able to successfully tame him, and the two flew off to do battle with the Chimera. But because of the fire-breathing, Bellerophon and Pegasus couldn't get close enough to the monster to stab it. So Bellerophon attached a piece of lead to his spear, then rammed it into the Chimera's mouth on his next fly-by.

Bellerophon Killing the Chimera

The lead melted and filled the beast's throat, suffocating it. I'm not sure why it suffocated, with two other apparent windpipes to draw on, but let's not look too closely. The lesson is clear: clever thinking and a flying horse are tough to beat.

This is Greek myth, and there are no happy endings. Not content with his status as a great hero and rider of the most wondrous horse ever to live, Bellerophon yearned for more: to see Olympus itself, the home of the gods. So Bellerophon urged Pegasus to fly higher and higher still, all the way up to Olympus' gleaming gates. Just as he was about to reach them, Pegasus bucked, and Bellerophon fell back to earth. His death, at this point, would have been merely tragic. But the gods, in punishment for his hubris, devised something far worse. Bellerophon lived, but crippled and blinded, stumbling over the earth for the rest of his days in search of his beloved Pegasus–who never appeared to him again. It always seemed far worse to me than Heracles' fate, or Achilles' or Icarus'. The once-great hero forced to live the rest of his life with his regrets, "devouring his own soul," as Homer puts it. And Pegasus? He goes to live in Olympus with the gods.

Hi, Madeline again. I agree, I've always found the story so sad. And Bellerophon's love for Pegasus reminds me of the ancient appreciation of horses in general, even ones that couldn't fly: Alexander the Great named cities after his steed Bucephalus, while Caligula made his horse a senator. In the Iliad, Achilles' immortal horses weep for the death of Patroclus, and later try, in vain, to warn Achilles about his fate. Flying or not, horses were magic in the ancient world.

Bellerophon's story also plays an important role in the history of literacy. In the Iliad, Glaucus of Lycia tells us that his grandfather Bellerophon was sent to King Iobates from King Proitus with a message scratched on a tablet.

As scholars have long noted, this is Homer's only mention of writing, and the first reference to it in the history of Greece letters. It's also tantalizingly vague: Homer doesn't say that the tablet has words on it—rather, he says that it contains semata lugra "sad signs." The sad part refers to the note's murderous content, but the semata is fascinating. Does it imply some earlier, more rudimentary form of writing, like pictographs? Or is it merely that written messages were so new in Homer's age that there wasn't a more elegant way to describe them? It's unclear. Scripts did exist in the Greek world before Homer's time (like Linear B), but they were used largely for clerical things–keeping track of sacrificial offerings, for instance, not messages.

Sarpedon's body, carried off by Death and Sleep, while Hermes looks on

By the way, Glaucus isn't the only grandson of Bellerophon who makes a notable appearance in the Iliad. There's also Sarpedon, the son of Zeus, who helps Hector lead the charge against the Greek camp, and tears down its protective palisade with his bare hands. He was one of my favorite cameo parts to write in The Song of Achilles—he's the only son of Zeus who fights in the war, and he's from the exotic (to the Greek eye) Lycia. He's killed by none other than Patroclus himself.

Have a favorite myth? I'd love to hear about it! Drop me a line either on my contact page or twitter (@MillerMadeline).

January 15, 2012

Mythological Character of the Week: The Gorgons

Monday, January 16th, 2012

The worst part, by far, of writing The Song of Achilles was researching snakes. Those of you who have read it know that a single snake appears, very briefly. But, just like all the rehearsal that goes into a single scene onstage, getting that serpent right involved major rolling-up of herpetological sleeves. For one thing, I needed to find out which snakes existed in that particular part of Greece (the island of Lemnos) during Homeric times. Of those varieties, I then had to choose the snake that I wanted, and observe how it looked and moved.

The upshot was that I spent two days looking at pictures and videos of snakes. Though, if I'm honest, part of the reason that it took so long wasn't diligence but the fact that if I studied these images for more than about ten seconds I got the creeping, shuddering horrors. So I had to take a lot of breaks. All this is by way of introducing the new Myth of the Week, those slithery, shudder-inducing ladies themselves, the Gorgons. Thanks to Chris for the great suggestion!

A Gorgon from Artemis' temple on Corfu. Such renderings were intended to be apotropaic--to ward off evil. Sidenote: I spent a summer during college on an archaeological dig in Corfu. I saw this in person!

Like other love-to-hate-them monsters in Greek mythology, the Gorgons attracted a lot of story-tellers, and therefore a lot of contradictory stories. For instance, in Homer, there was only a single Gorgon, simply called "Gorgo" whose fearsome, snaky head adorned Athena's shield. In later myths, however, there were three of them: Euryale, Sthenno and, of course, Medusa. They were described as having snake hair, and were often also depicted with boar tusks, wide, grinning faces and wings (see above, and below).

One of the strangest things about the Gorgons is that though they were supposedly sisters, two of them were goddesses, and the third, Medusa, was mortal. The comedian Eddie Izzard has a funny piece about Medusa's outrage when she discovers this. (It's followed by a hilarious bit about Medusa putting on a mouse video to try to keep her snakes calm. It's on youtube, if you're interested.)

A similar Gorgon motif, from the Louvre

From a narrative perspective, one of the Gorgons needs to be mortal so that Perseus can slay it. But other myths sprang up to explain why it was Medusa in particular. In the most popular of these, Medusa had been born a beautiful mortal woman, with particularly gorgeous hair. As she was praying to Athena in her temple, the god Poseidon appeared and raped her. Athena was so deeply offended by this that she—

Blasted the sea-god with her father's thunderbolt? Stabbed him through his fishy chest with her awesome goddess-of-war spear?

No. Rather than being concerned about the girl, she was concerned about the pollution of her temple. She averted her eyes in disgust during the act, and afterwards, when Poseidon was gone, blamed Medusa for flaunting her too-seductive beauty. Then, to punish her, she cursed the girl's appearance, changing her into a hideous monster who turned all she looked on to stone.

Mosaic of Medusa

What's most disturbing about this story, I think, is how casually and matter-of-factly Ovid tells it. It isn't meant to be a tragedy; it isn't meant to highlight Athena's gross unfairness. If anything, it seems to find her choice of punishment fitting. It makes for some deeply unpleasant commentary on Roman culture, and a particularly brutal portrait of the cruelty of the gods.

Afterwards, the newly transformed Medusa goes to live with her "sisters," and this is where the well-known story picks up. Perseus is given the task of slaying her and bringing back her head as proof. With Athena's help he arrives at her lair, and using his reflective shield is able to avoid her deadly gaze. With his sword, he strikes off her head. Medusa falls to the ground, dead.

Medusa's head, Caravaggio

Next comes one of my favorite parts of the story. From the stump of Medusa's severed neck is born the beautiful, winged horse, Pegasus. I have always found this fascinating: that one of the most beloved, and lovely creatures from Greek myth derives from the ugliest. This is all the more interesting because in the ancient mythological worldview, external beauty was a sign of similarly beautiful inner character–there was no Greek adage against judging a book by its cover. Thus, the scurrilous soldier Thersites, with his virulent attacks on the aristocracy, is depicted as hideous, while the noble Achilles is the most beautiful of the Greeks. But Pegasus and Medusa seem to break the pattern. If we take Ovid's story as true, that Medusa was once a normal young woman, I like to think that Pegasus is some final remnant of that former, truer self. Through Pegasus, maybe she is able, at last, to escape Athena's curse.

Pegasus, from Theoi.com

Medusa's petrifying power was so strong that it lived on, even after her death. Perseus is able to use the gruesome head against his enemies, including the sea-serpent from whom he rescues the princess Andromeda. Eventually, judging such a thing too dangerous for a mortal to keep, Athena takes custody of the head and fixes it on her shield. We never hear what happens to the other two gorgons, whether they mourned for their sister or how they lived out their eternal lives. It's too bad; it might make a good story.

The myth of Medusa is filled with transformations—from beautiful girl to monster, from living flesh to stone, from corpse to winged horse. But there is one more strange and minor transformation associated with her that I've always enjoyed. After Perseus has slain the sea-monster, but before Athena has relieved him of the head, Perseus wants to put the head down for a moment. But he frets that it will get damaged on the hard earth. So, with a solicitousness that no one showed poor Medusa in real life, he pulls seaweed and greens from the sea, and makes a pallet for the head. As soon as Medusa's skin touches the sea-greens, they begin to stiffen. And this, says Ovid, was the beginning of the first reef.

Perseus holding aloft Medusa's head

Unsurprisingly, Medusa's story was a popular one in visual arts, and painters seem to have been particularly taken with the image of the severed head. I included Caravaggio's version above, but the absolutely grossest one I refuse to post, since it gives me snake-shivers. But if you really want to see it, click here.

I warned you.

Next Week: The winged horse Pegasus himself.

January 10, 2012

Achilles is an Indie Next pick!

Tuesday, January 10th

I am thrilled to announce that the independent bookseller collective IndieBound has chosen The Song of Achilles for one of its March Indie Next picks! This is a huge honor for me, as I have been spent many, many happy hours in independent bookstores in my life, and found several of my favorite books through bookseller recommendations. I feel humbled and gratified knowing that these passionate book-lovers enjoyed my novel, and I am very much looking forward to visiting some of their stores in March and April.

Click here to get The Song of Achilles from IndieBound!

January 3, 2012

Gregory Maguire Interview

I had the amazing fortune to be interviewed recently by the hilarious and lovely Gregory Maguire, author of Wicked, Confesssions of an Ugly Step-Sister, and many other best-selling novels. Not only is he a fellow Bostonian, but I am pretty sure that this is the most fun I will ever have answering questions. Click here to read our conversation!

December 18, 2011

Myth of the Week: Philoctetes

Monday, December 19th, 2011

Today's myth of the week is one of my very favorites, though I didn't discover it until college. When I graduated from high school, my Latin teacher had given me a book of Sophocles' tragedies as a gift, and I was steadily working my way through it. Somewhere in the middle, I came to one called "Philoctetes." Who?

This was before the days of Google, so I got out my trusty Oxford Classical Dictionary and learned that Philoctetes had been a close companion of Heracles. Maybe the closest: when Heracles was dying in agony, he begged his friends to put him out of his misery; Philoctetes was the only one who had the guts to do it. In gratitude, Heracles bequeathed Philoctetes his famous bow, with its arrows dipped in the poison blood of the hydra.

Bust of the playwright Sophocles

But that was just the beginning of Philoctetes' story. Years later, he joined the other heroes of Greece in pursuing Helen of Sparta's hand in marriage. By then he was renowned for his connection to Heracles, and also for his deadly archery. And though usually in the ancient stories a bow and arrows are considered the weapons of a coward (as with Paris), you never hear a single word against Philoctetes. Heracles' bow would have been enormous, and only a true hero could have strung and drawn it.

As a suitor of Helen, Philoctetes must have seemed out of place among the other men. He was a generation, or more, above them, and I imagine him as weathered, dignified, and still full of stoic grief for the loss of his famous friend. It was unlikely that such a man would tempt Helen, and of course he did not. But he did, along with all the other suitors, swear to uphold her marriage to Menelaus.

A powerful-looking Philoctetes, clutching his wounded foot.

Which is how, some years later, he found himself summoned to Troy to get her back. Despite his age, Philoctetes upheld his oath and, paired with Odysseus as a sailing partner, the two men and their fleets began making their way to Troy. Like all Homeric journeys, there were frequent stops on islands along the way, and on one such island, Lemnos, Philoctetes was bitten by a terrible viper. He didn't die, but the wound festered agonizingly, stinking and causing Philoctetes to fall into seizures. Odysseus, practical as ever, didn't want a smelly, hideous, screaming man on the ship, so he persuaded the other men to abandon Philoctetes while he slept.

When people ask me why I don't see Odysseus as a straight-up hero, this myth is one of my answers. Odysseus' pragmatism here seems indistinguishable from ruthlessness: he abandons an aging hero, in excruciating pain, on a deserted island without any supplies of food or water. When Philoctetes wakes, there is only empty beach and his bow. Ten years of lonely, crushing pain follow. In describing these years, Sophocles is at his most moving. As in Oedipus at Colonus, and Ajax, Sophocles once again shows himself the champion of those who have been cast out from society, who feel themselves betrayed and abandoned. Philoctetes' bitter monologues are absolutely piercing in their indictment of a society that would throw away its elders because they have become inconvenient. No matter how many times I read them, I always find myself caught up anew.

Philoctetes, with his wounded foot. Heracles' bow and arrows in the background. He has been hunting birds to feed himself.

Fast forward ten years, after Achilles has died but before Troy has fallen. The Greeks learn from a prophecy that they will never take the city of Troy unless the bow of Heracles fights on their behalf. In Sophocles' play, the Greek leaders dispatch Odysseus and Neoptolemus, Achilles' young son, to go get Philoctetes (in other versions, Odysseus' partner is the tricksy Diomedes). Odysseus' plan is to send Neoptolemus in as mediator because Philoctetes doesn't know Neoptolemus, and is less likely to shoot him on sight. Neoptolemus is supposed to engage the old man in conversation, wait for him to fall into a fit, then steal his bow and arrows. After all, reasons Odysseus, the prophecy never said that it needed the hero, only his weapons.

But Neoptolemus finds himself drawn to the old man's dignity, and moved by his suffering. When Philoctetes falls into a fit, he does not take the bow, only holds it until Philoctetes recovers, then returns it, chastising Odysseus: "It is far better to be just than wise." Still enraged by their betrayal, Philoctetes refuses to help the Greeks. Just when all seems lost, the god Heracles appears, urging his old friend to relent, and promising Philoctetes that if he goes to Troy he'll find a healer—Machaon, son of Asclepius—who can end his agony. Philoctetes, obedient to his friend, agrees. Once at Troy, Philoctetes helps to take the city and, most importantly, kills the prince Paris—one archer slaying another. He survives the war and returns safely home.

Vase Painting of Philoctetes, with his wound, bow and arrows. Fletcher Fund, 1956, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

What makes this such an interesting tragedy is that, in the end, it isn't one. Thanks to Neoptolemus, Philoctetes is welcomed back into society. The middle-aged Odysseus is inveterate, set in his ruthless ways, but there is still hope to be found in the innocent and clear-eyed gaze of youth. It also offers hope in the form of forgiveness. Philoctetes could indeed make the Greeks suffer as he has suffered; but in the end, he does not. I love his story so much that I found myself constantly having to battle the temptation to include it in my novel. There are several Philoctetes scenes that got left on the cutting room floor simply because they didn't fit, but one cameo remains.

I am not the only person who has been moved by Philoctetes' story over the years. He is the subject of a Wordsworth sonnet, and Sophocles' play forms the core of the amazing "Philoctetes Project," which brings this play and others to army veterans. At the other end of the spectrum is Disney's "Hercules" which features–sort of–Philoctetes as a character. The satyr voiced by Danny Devito was inspired, I can only guess, by some unholy combination of Philoctetes and Chiron, plus some goat thrown in. He calls himself "Phil."

The Myth of the Week is going to take a vacation next week, but will return in the New Year. I wish you all very happy, myth-making holidays!

December 15, 2011

Achilles is Daily Mail Christmas Pick

The Daily Mail recently chose The Song of Achilles for its Christmas Historical Fiction Pick. Critic Kathy Stevenson calls it, "One of the most extraordinary books I've read this year" and "as great an epic retelling of Homer's Iliad as you will find." She ends the review by saying:

"The tragedy of Achilles's hubris and death in the battle for Troy is so poetically heartrending that I confess, dear reader, I wept."

To see the entire article, click here (scroll down to Historical Fiction).

December 11, 2011

Myth of the Week: Hyacinthus

Monday, December 12th, 201

Recently, a friend and I were talking about how the homosexual undertones (or overtones) are often bowdlerized from retellings of Greek myths. As children, we had both been puzzled by the story of Ganymede, the beautiful youth whom Zeus falls in love with and, in the form of an eagle, abducts to Mount Olympus to be his lover and cupbearer. In the version I read, there was no mention of Zeus' desire, and I remember feeling confused as to how Zeus knew he was such an excellent cupbearer just by looking at him, and why cupbearers were so hard to come by, and furthermore, why did it make Hera so mad?

All this is by way of leading up to today's story about the youth Hyacinthus and the god Apollo, which was the first myth where I realized that the two men were definitely lovers, not just "close companions."

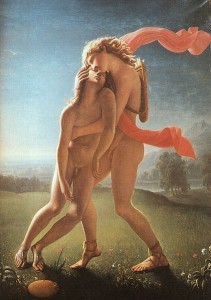

Apollo and the dying Hyacinthus, with the fateful discus on the ground. Alexander Kiselev.

Hyacinthus was a beautiful Spartan youth, beloved by the god Apollo. As the good Spartan he was, Hyacinthus loved athletics, and one day the two decided to practice throwing the discus. Apollo went first, sending the disc flying up to "scatter the clouds" as Ovid says. Hyacinthus ran laughing after it, thinking to catch the disc, but instead it hit him in the head, killing him. Ovid has a beautiful passage about Apollo holding the dying youth, desperately trying to use his skill with medicine to keep him alive. But even the mighty god of healing could not save the one he loved.

In honor of his lover, Apollo makes a flower spring up from Hyacinthus' blood. Confusingly, this flower isn't actually what we today call a hyacinth. Most sources agree that it was most likely an iris or a larkspur, since the myth tells us that Apollo writes on the flower the sound of his grief (Ai, Ai). The iris, with its yellow markings on the purple leaf, seems the likeliest to me, though theoi.com disagrees, offering this helpful visual aid on behalf of the larkspur. (On a side note, some say this flower, whichever it was, actually sprang from the dead Ajax's blood, not Hyacinthus'. In that case, the markings spell out AI, in honor of Aias, Ajax's Greek name.)

An iris. I know, I don't see the "AI" either. Photo taken by Danielle Langlois, July 2005, Forillon National Park of Canada, Quebec, Canada

In a second, quite popular variant of the myth, Hyacinthus' death is actually a murderous crime of passion. Turns out that not only was Apollo in love with Hyacinthus, but so was Zephyrus, the west wind. Seeing how attached Apollo and Hyacinthus were, he grew jealous, and in an old-fashioned twist on "If I can't have him no one can" he deliberately blows the discus into Hyacinthus' path, killing him. This version emphasizes the terrifying pettiness of the gods, and the dangers of mixing with them, even if–especially if–they love you. Love nearly all ancient love affairs between mortals and divinities, it ends in tragedy for the mortal.

Apollo and a swooning, strategically modest Hyacinthus

Whenever I tell this story, I always wish that there were more of it. Its final image of Apollo cradling Hyacinthus is so beautiful and sad (and very popular in art). But we don't know anything about Hyacinthus and Apollo's love beyond that moment, how they came to meet, or who Hyacinthus was. It's almost more of a triptych then a story, three moments caught in amber: the youth and Apollo happy together, the youth chasing the discus, the lover grieving over his dying beloved. It's enough to make me feel sympathy for Apollo, who has never been a particular favorite of mine.

Apollo catches the falling youth. Jean Broc

Aside from its tragedy, Hyacinthus' story also has a historical significance. The "-nth" suffix in Hyacinthus indicates that the name is actually quite old, a remnant of some sort of pre-Greek language, from before the development of ancient Greek culture as we know it. Other examples include "Corinth" and the word "labyrinth" (see the Minotaur myth).

Some speculate (the Oxford Classical Dictionary included), that the story of Apollo tragically killing Hyacinthus is actually symbolic. Given the antiquity of his name, it's likely that Hyacinthus was some sort of older native nature deity, who was replaced by the Olympian Apollo. The myth preserves this cultural change in story form, having the new god "kill" the old one.

Classical statue of Apollo, known as "Apollo Belvedere"

Either way, Hyacinthus became an important religious figure, who was particularly worshipped in Sparta during a three-day festival, called Hyacinthia. The festival included mourning rites for the youth's death, then celebration of his rebirth as a flower. In this regard, Hyacinthus seems similar to the god Adonis, and the eastern Attis, all three of whom are youths who die in order to ensure the earth's fertility—the male versions of Persephone. The festival was important enough to the Spartans that they were said to have broken off a military campaign in order to return home and celebrate it.

Vase painting of a discus-thrower, with other athletic gear.

A final story about Apollo and Hyacinthus. Though the myth has had a long life in visual art, it hasn't been nearly popular in other types of media. The only exception I could find was an opera composed by the eleven-year-old Mozart, entitled "Apollo et Hyacinthus." The libretto for the piece was written by a priest, Rufinus Widl, who apparently found the story too scandalous because he invented a sister for Hyacinthus, Melia, to replace Hyacinthus as Apollo's love interest. In this version, the youth's death is more tragic to the family than Apollo, affecting the god only because it is an impediment to wooing the sister.

The lovely thing about myths is how adaptable they are, how much they can be shaped and molded by each new teller. But there is bending, and then there is breaking. To remove Apollo and Hyacinthus' love from this story is to take out the spine of the tale, rendering it unrecognizable. There is certainly a beautiful story to be told about a lover who kills his beloved's kinsmen (as Shakespeare knew when Romeo killed Tybalt), but that is another story, not this one. Hyacinthus and Apollo (and Zephyrus), do well enough on their own.

Thanks to reader Sam for the suggestion!

December 4, 2011

Myth of the Week: Persephone

Monday, December 5th, 2011

Happy December! Here in Massachusetts, the weather has become decidedly wintry, and the grocery stores are full of the season's fruits: clementines, grapefruits and, my favorite, pomegranates. In honor of that luscious fruit, and the changing season, today's myth is Persephone. The suggestion comes thanks to the fabulous Sarah Clayton (@Clayton_Sarah), a passionate reader and advocate for books.

Persephone (Proserpina in Latin) was the beautiful daughter of Zeus and the goddess of grain, Demeter. One day while she was picking flowers with her companions (Artemis and Athena, in one version of the story), Hades burst from the earth in a golden chariot, seized the girl, and carried her off to his palace in the Underworld.

Persephone being abducted by Hades. Note Athena, with the helmet, trying to rescue her. Rubens.

In modern retellings of Greek myths, it's become common to portray Hades as evil, or demonic (see Disney's Hercules). This is absolutely not present in the ancient myths. Though he was a gloomy and frightening god, the ancients never saw Hades as evil. He wasn't responsible for human death or suffering, merely charged with shepherding the souls once they had left their bodies—a necessary, if melancholy, job. Out of respect and awe for his position, he was rarely depicted in ancient art. (Post-Classical artists had no such restrictions, where his abduction of Persephone is a favorite subject.)

In snatching Persephone he was no more villainous than any other ancient abductor, Zeus, Poseidon and Apollo included. In fact, some might argue he was less so. The lonely god of the Underworld had gone to his brother Zeus asking for a bride. Zeus suggested Persephone and, knowing that her mother would never allow the girl to go, likewise suggested the abduction. So it was with her father's permission that Hades took the girl—as polite as it gets among the divine unions. Small consolation, of course, to Persephone.

When Demeter discovered what had happened to her daughter, her grief was so great it blighted the soil, causing the first winter. In some versions of the story she even purposefully destroyed the earth, holding the world hostage until Zeus ordered her daughter returned. I like this portrait of Demeter as vengeful mother (see Clytemnestra), and Demeter's name is even etymologically related to the word for mother (meter), so fiercely canonical was this part of her identity.

Demeter (Ceres in Latin) is shown searching the world for her daughter, carrying a torch and a symbol of her power, a sheaf of wheat.

Hermes, guider of souls to the underworld, was sent to fetch the girl. But before she could be set free, she ate the fateful pomegranate seeds—the food of the dead, and a bright-red stand-in for the blood that dead souls were said to crave. The poet Louise Glück describes it like this:

"Persephone

returns home

stained with red juice like

a character in Hawthorne—"

She may leave, but the seeds condemn her to return and spend a season each year in the land of the dead. Winter is born.

Hermes bringing Persephone back to her joyful mother. Frederic Leighton.

Sadly, Persephone isn't given much personality in the myths, beyond that of passive victim. More often the tale is focused on Demeter, or the dramatic moment of abduction. In some stories, Persephone is even stripped of her name, called simply "Kore" (maiden), as though the authors wanted us to see her symbolically, rather than personally. It was in this symbolic role that she was worshipped alongside her mother in the Eleusinian mysteries, a cult of Demeter near Athens. The rituals were famously secret, but centered around Demeter and Persephone as guardians of the earth's cyclical fertility.

Persephone stands at right. On the left is Triptolemus, another agrarian deity. With Persephone and Demeter he makes up the Eleusinian trinity.

But where myth is silent, artists and poets have stepped in to fill in the gap. I particularly love Louise Glück's poetry collection Averno (which I quoted from above), a series of poems about death, centered on Persephone's story. Glück takes the bold and unusual step of making Hades a tempting and genuine lover. In turn, Demeter becomes a more ambiguous figure, a mother who may be suffocating her daughter's desire for independence. Persephone is shuttled back and forth between these two figures, at home in neither place, something Glück expresses beautifully:

"The terrible reunions in store for her

will take up the rest of her life."

There is a division at the heart of Persephone, who is at once the bringer of spring and the grim and terrifying Queen of the dead. Her story is rich with symbolic and allegorical resonance about death and rebirth. She is the incarnation of that ancient saying supposed to make a sad man happy, and a happy man sad: This too shall pass.

Persephone with her pomegranate. Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

Persephone also helped to provide for the ancients a more merciful face of death. Hades was known for being immovable, but Persephone assists a number of heroes and grieving lovers who stumble down into her world. She is the one who grants Eurydice back to Orpheus, and she likewise aids Psyche in her quest to earn back Eros.

In honor of Persephone's story, I will end with a great trick I just learned for peeling pomegranates (without becoming your own red-splattered character from Hawthorne).

Fill a large bowl up with water, submerge the pomegranate, and cut and strip it underwater. Not only will it contain the juice squirts, but the white pulp floats and the seeds sink. Much easier! Good thing I am not Persephone or it would never been spring again….