Madeline Miller's Blog, page 7

March 12, 2012

Myth of the Week: Callisto

Monday, March 12th, 2012

Today's Myth of the Week is in honor of Latin teacher extraordinaire Walter, and his delightful students. Good luck on the upcoming National Latin exam!

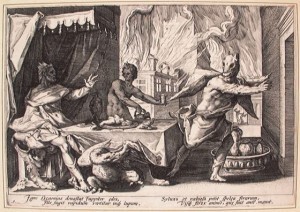

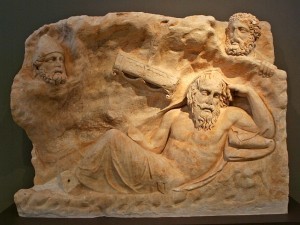

Galileo knew his mythology. After discovering the four largest moons of Jupiter, he decided to name them, fittingly, after four famous loves of Zeus (Jupiter, to Romans): Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto. Of these four, Callisto's story is the least well known, but maybe the most fascinating. Callisto (Kallisto in the Greek) was an Arcadian nymph, whose name literally means "most beautiful." Her father was the infamous and cruel Lycaon, whom Jupiter changed into a wolf as punishment for his savage and "wolfish" behavior. He is often cited as a mythological precursor of the werewolf.

Zeus transforming Lycaeon to a wolf

Callisto preferred the woods to her father's house. She loved to hunt and became a favorite of the goddess Artemis, joining her band of nymphs and swearing to remain a virgin eternally. Although today we might regard this as overly stringent, in the world of ancient mythology virginity meant freedom. As one of Artemis' virgins, she would never have to marry a man of her father's choosing, and could remain without domestic responsibilities in the woods her entire life.

Unfortunately, like many beautiful nymphs, she caught the eye of Zeus. By this point in myth history Zeus was getting cannier in his disguises. Rather than transforming into a bull, or swan, Zeus decided to appear to the girl as Artemis herself. Ovid describes the two women talking intimately, then "Artemis" begins kissing Callisto.

Artemis, goddess of the hunt, photo by Steffen Heilfort

It's an electrifying moment, and an unusual one; there are very few surviving mentions of women loving women from the ancient world, simply because nearly all of the ancient writers were men. The references that do survive are generally dismissive or disgusted. But that is not that case here: Callisto welcomes her mistress' passionate embrace. For a moment it almost seems like we have stumbled upon a wonderful secret history.

But the audience knows better, because it isn't Artemis at all–it's Zeus. The story gave its ancient readers just enough time to be intrigued, or titillated, or shocked before setting the world "right" again. Callisto's error is played for laughs: she thinks it's Artemis who she likes, but fake out! It's really Zeus, who she doesn't!

Zeus disguised as Artemis, with Callisto

Call me humorless, but I'm not laughing. Zeus reveals himself, rapes Callisto, then vanishes. The girl is doubly distraught—not only about the assault, but about the breaking of her oath of virginity to Artemis. (This being the ancient world, it doesn't matter that it was unwilling—the oath is broken all the same). She is all the more distressed when she learns that she is pregnant, and must hide the pregnancy from her sharp-eyed mistress as long as possible.

A suspicious Callisto, with Zeus-as-Artemis. By Rubens

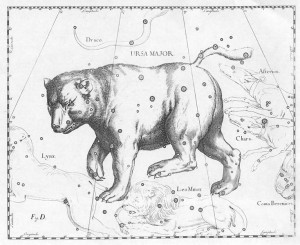

We can see where this is going. Artemis is notoriously unsympathetic and uncompromising about transgressions—witness her punishment of poor Actaeon for accidentally glimpsing her in the bath: he's torn apart by his own dogs. When Callisto takes off her dress to bathe, Artemis notices her belly. She flies into a rage, and is joined by Hera, who is herself angry at Callisto for having slept with her husband. As usual, Hera doesn't care whether it was consensual. She turns the girl into a bear and Artemis kills her. Zeus (where were you five minutes ago?) swoops down to rescue Callisto's unborn child, a boy named Arcas. And, in homage to the boy's mother takes Callisto's body and sets it in the sky as the "Great Bear"—Ursa Major. Her son, when he dies, joins her, becoming Ursa Minor.

Artemis discovers that Callisto is pregnant

That's one version of the story—in another, Callisto flees into the woods in her new ursine form, living out her days as an animal. Fast forward fifteen years or so. Callisto's son, Arcas, has grown up a gifted hunter, just like his mother. He is wandering in the woods one day, and spots a bear. Hoisting his javelin, he prepares to kill it with a single blow. But as he is about to hurl the spear, Zeus stops him, not wanting him to be guilty of the sin of killing his own mother. He whisks the two of them up to the heavens, transforming them into constellations.

Ursa Major, the Great Bear

In later generations, Zeus' embrace of Callisto while disguised as Artemis was the part of the story that really seemed to grab people's imaginations. Partially that's because it was Ovid's version, but surely also because of its frisson of transgression. But for me the most moving and tragic part of the story is the moment after, when Callisto realizes what is really happening. That she's been tricked by Zeus, and is about to lose everything she holds dear—Artemis' favor, her fidelity to her oath, her place in the world, even her humanity. Becoming a constellation just doesn't seem like recompense enough.

A final, completely different, thought. Artemis seems to have been particularly associated with bears, and at her sanctuary at Brauron young girls would serve as "little bears" in a ritual to honor the goddess. It's a much nicer face of the goddess than Callisto sees.

I'm excited to announce that tomorrow (March 13th) is the kick-off of my US book tour. If you're in the area and interested, please join me!

March 10, 2012

My Trip to Troy

I recently wrote a "Traveler's Tale" for the Wall Street Journal about the first time I visited the archaeological site of Troy. The experience was absolutely amazing. You can also see a slideshow of the trip here.

Orange Prize Longlist

I was delighted, and very honored, to find out that The Song of Achilles had been longlisted for the Orange Prize. It is especially exciting to be in such amazing company: fellow long-listees include Ann Patchett, for State of Wonder, Emma Donoghue for The Sealed Letter, Jane Harris for Gillespie and I, and Half Blood Blues by Esi Edugyan. Here is the Guardian's article about the entire longlist.

March 5, 2012

US Publication News

In just a handful of hours, The Song of Achilles will be officially released in the US! Thrillingly, it has been chosen as a Best Book of the Month by Amazon, and a March Indie Next pick. There are also some early reviews out, including O Magazine, The Bryn Mawr Classical Review, and the Historical Novels Society. Here's a taste of what they said:

"You don't need to be familiar with Homer's The Iliad (or Brad Pitt's Troy, for that matter) to find Madeline Miller's The Song of Achilles spellbinding. While classics scholar Miller meticulously follows Greek mythology, her explorations of ego, grief, and love's many permutations are both familiar and new. –O Magazine, Liza Nelson

"Miller's debut novel…is a tour de force of history, mythology, politics, and devotion… Readers may suffer from withdrawal as they reluctantly finish this book, and this reviewer hopes to see more soon from this talented author." The Historical Novels Society, Editor's Choice Review

"With this novel, we can fall in love again: for Madeline Miller has made blind Homer sing to her… It has the magnificence of myth; it has the passions of humanity." Bryn Mawr Classical Review, Catherine Conybeare

If you're interested in reading more, visit my reviews page. Meanwhile, I am counting down those hours!

Myth of the Week: Orpheus

Monday, March 5th, 2012

Most of the heroes in ancient Greek myth were known either for their exploits in war or their victories over terrifying monsters. But two of the most famous ancient figures made their mark in other ways—Daedalus, the master craftsman, and Orpheus the great musician. I love the stories of both of these men, but thanks to the excellent suggestion of reader Simon, I'm going to start with Orpheus.

Orpheus' origins are obscure. He was associated with the region of Thrace, north and east of Greece, and was most often said to be the child of the muse Calliope. In some versions of the story his father is a king of Thrace, in others it's Apollo, god of music himself.

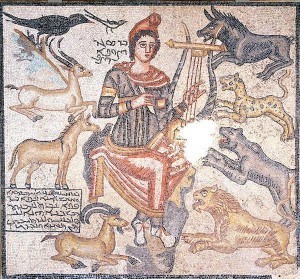

Mosaic of Orpheus taming wild animals with his music

Orpheus was born with a god-like gift for music, able to sing and play the lyre so beautifully that even the rocks themselves wept. It was a popular trope in art, both ancient and modern, to show the great musician surrounded by formerly savage animals made tame by the sweetness of his music.

Orpheus was also a favorite subject of poets, especially since in the ancient world poems and songs synonymous. That's why Homer asks the muse to "sing of the rage of Achilles," and why Vergil tells us he is going to "sing of arms and a man." The Iliad literally means "the song of Troy" ("Ili" means Troy, and "ad" here is the ancestor of our modern word "ode"). Orpheus was the incarnation of a writer's power, proof that you don't need a club, or magic sandals–you could change the world with your words alone.

Orpheus enchanting the wild beasts, including a unicorn

Of course, any author who did take on Orpheus' story had a true artistic challenge—were they going to try to create an example of one of Orpheus' legendary songs? I always find this a fascinating moment in art, when a character who is meant to be a genius at something must finally reveal their work. Characteristically, Ovid dares to write for Orpheus—Vergil, ever modest, does not. I love both of those ancient poets, but I have to say that if I were forced to pick one of them for the voice of Orpheus it would be Vergil. I would believe it that he made the stones weep.

Orpheus falls in love with the beautiful nymph Eurydice, and the two make plans to wed. But on their wedding day, Eurydice steps on a snake, which bites her. In some versions of the story, she doesn't see the snake because she is dancing with her handmaidens; in Vergil's version, she is fleeing Aristaeus, a young demi-god attempting to rape her. Either way she is killed, and Orpheus is stricken with terrible and all-consuming grief.

Eurydice bitten by the snake

Vergil's description of the mourning Orpheus is hauntingly beautiful, as he sits alone on the shore singing to his lost wife. Part of what makes it so arresting is that Vergil addresses Eurydice herself, "he was singing to you, sweet wife" making the reader, Orpheus and Vergil all one. He also echoes the sound of the "you" ("te," in Latin) throughout the line, mirroring the repetitive nature of Orpheus' longing. It's the type of effect that is nearly impossible to capture in translation, so here are the lines, in Latin, with the "te" sounds highlighted:

te, dulcis coniunx, te solo in litore secum,

te veniente die, te decedente canebat.

You, sweet wife, he was singing of you, by himself on the lonely shore,

you as day was coming, you as day was departing.

Orpheus decides on a desperate course of action—he will go into death itself to try to retrieve Eurydice. Armed only with his lyre and his beautiful voice, Orpheus makes his way past every terrifying danger the underworld holds, from Cerberus to the crossing of the river Styx. Finally he arrives at the court of Hades and Persephone, and begins to sing. Ovid has an amazing description of the whole underworld stopping to listen—even those eternally tormented souls in the pit of Tartarus. Tantalus no longer reaches for food and water, and Sisyphus sits upon his rock. Moved to tears, the king and queen agree to release Eurydice on their one, famous condition: that as he leads Eurydice up to life again, he not turn to look at her.

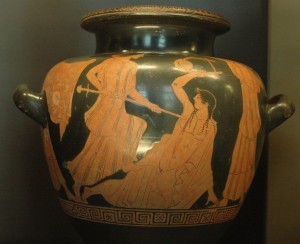

Orpheus losing Eurydice to death a second time

As a child, I always found this part inexplicable—why couldn't he look at her? Were they just being cruel? But as I got older I began to appreciate its allegorical resonance, like the story of Psyche, about human nature, and doubt, and trust. It's easy to say I would not have looked. But if I really think about it, I can name half a dozen times in my life when I did, metaphorically, look back. Fortunately, I have never had to suffer the consequences Orpheus did for my fears.

Just as they are almost safely away, Orpheus is overcome with doubt about whether she is truly behind him. Without thinking, he turns to look. Her faithful shade immediately vanishes, and the devastated Orpheus attempts to return to Hades and rescue her again. But this time the boatman Charon refuses to carry him across the river. He sits on the shore starving, hoping for death, so that he may join Eurydice. But the gods will not let him die. Reluctantly, he returns to the upper world, finding solace only in his music. I am no musician myself, but I know how often I have turned to songs for comfort and understanding. I love that this has been a part of humanity for as long as our myths go back.

A maenad attacks Orpheus, who clutches his lyre

Ovid adds an interesting twist to the story at this point. He says that many women sought to replace Eurydice in Orpheus' affections, but that Orpheus spurned them all, and turned instead to men, which was the origin of homosexuality in Thrace. A fascinating detail, that he doesn't delve into further. But it does give him a transition to Orpheus' unfortunate, grisly end. A group of Maenads, female followers of Bacchus, are enraged by Orpheus' rejection of women, and in their wine-sodden frenzy decide to tear him to pieces–a version of "if we can't have him, no one can!"

As they approach him, Orpheus doesn't run, only keeps playing his beautiful, mournful songs. The Maenads throw rocks at him, but even the rocks are in love with Orpheus, and fall far short. It is only when the Maenads begin to scream and beat their drums, drowning out Orpheus' song, that they are able to attack him—and literally tear him apart. Ovid, never one to spare a gruesome image, has Orpheus' head float down the river, still singing.

Nymphs find the head of Orpheus

Eventually, all ends well. Orpheus is reunited with his Eurydice in the underworld where, Ovid says, they may walk together, leading or following, and looking back as they please. In framing the story this way, Ovid doesn't use the allegorical resonance of looking back as a failure of trust. Instead, he makes the story about the cruelty of life that can keep lovers apart. Here, in the underworld, there is no bar to love.

The story of Orpheus and Eurydice has inspired numerous artists working in film, on the stage, and in print. Most recently, I enjoyed Sarah Ruhl's play "Eurydice" which takes the perspective of the story's heroine, and adds the character of Eurydice's dead father. Eurydice is poignantly torn between life and her lover, and staying with her beloved father.

I wish you all a very happy start to March, whichever direction you happen to be looking.

February 27, 2012

Myth of the Week: Athena

Monday, February 27th, 2012

Like a lot of bookish, myth-reading girls, Athena was my hero. After all, what wasn't to love about this goddess? She was brilliant, bold, wore amazing armor, and could hold her own against even the greatest Olympian gods. Her powers—of strategy, craftsmanship and wisdom—were all things I wanted to be good at too.

One of my favorite stories is the one about her birth—bursting, full-grown, from her father's head. Her mother, Metis, was the goddess of wisdom and cunning, and Zeus' first wife (before Hera). Unfortunately, a prophecy revealed that she would give birth to two children—one a daughter, and the second a son, who would grow up to be greater than Zeus himself. The ever-insecure Zeus decided to diffuse the problem by swallowing Metis whole, with the side benefit of taking her wisdom for himself.

Athena bursting fully armed from Zeus' head

But nine months later Zeus was struck down with an agonizing headache. Ever-helpful son Hephaestus seized his ax, and split open Zeus' head. From the cleft leapt his daughter Athena, gray-eyed goddess of wisdom. Like her half-sister Artemis, she announced that she would be remaining a virgin, and unmarried. Quickly, she became one of her father's most trusted counselors, often sitting on his right hand to offer advice. She never rebelled against her father, so we don't know if she was in fact greater than he was—but there was a legend that her aegis (breastplate), was so strong that even Zeus' thunderbolt couldn't pierce it. The dreaded son never manifests.

Athena armed and wearing her aegis

Athena also proved her mettle during the war against the Giants and Titans, where she was one of the most powerful warriors on the Olympian side. According to some myths, she battled the fire-breathing giant Enceladus, at last hurling the island of Sicily upon him, beneath which he still vents his smoky breath (Mount Etna). She also battled the giant Pallas, and in one myth, skinned him alive to make her powerful aegis—the same breastplate that she would later affix with the head of the Gorgon Medusa. She also added the giant's name to her own as a trophy, which is why she's often referred to as "Pallas" or "Pallas Athena."

Pallas Athena

One of the most famous legends about Athena is how she came to be patron of the great city of Athens. Both she and her uncle Poseidon wanted the city for themselves, and they decided to hold a contest: whoever could give the city the most useful gift would get to have it. Poseidon struck the ground with his trident, and a spring of salt water bubbled up. Impressive yes, but useful? No.

When it was her turn, the ever-wise Athena gave the city an olive tree, which not only provided food, but also olive oil, wood, and (very important in Greece) shade. The decision went unanimously in her favor. Did Poseidon really think he had a chance? Also, Athens sounds a lot better than "Poseidons."

Statue of Athena

Athena was also known for being a great champion of heroes—aside from her favorite of favorites, Odysseus, she lent a hand to Perseus, Diomedes, Hercules, Bellerophon, Orestes, the master craftsman Daedalus (surely a hero after her own heart), and many more.

Her most famous epithet is "grey-eyed" (glaucopis). But she was also known by other names—daughter of Zeus, craftswoman, and interestingly, horsewoman (hippia). Her uncle Poseidon may have been the god of horses, but Athena was the god of horse-taming. Among her many other accomplishments, she helped inspire the bridle.

Athena with Pegasus, who was tamed thanks to a golden bridle

For all my Athena-love, as I got older, I started to recognize other sides to the goddess. Yes, she could be a hero's best support, but she could also be terrifyingly ruthless, as in her treatment of Medusa, or Arachne, or how she impales Ajax the lesser on a rock (though, frankly, he had it coming—more on that later). It's also interesting to note that nearly all of those she favored were men, Odysseus' clever wife Penelope excepted. One thing is clear; she isn't a goddess of wisdom in the mold of Prometheus, who sees himself as a universal protector of human kind. Instead, she is a strict mistress who favors only those who have earned—and who work to keep—her good will.

Athena also figures prominently in the story of the golden apple, being one of the three goddesses in competition for the prize of "most beautiful." I've always been vaguely disappointed in Athena that she cared about this—it seems beneath her dignity, somehow. Maybe she should have taken her cue from her little sister Artemis, and left it to Hera and Aphrodite to battle out.

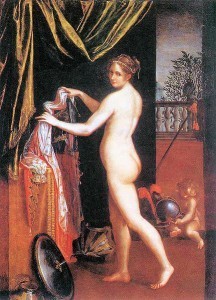

Athena dressing, with her armor on the floor.

Each of the goddesses offers the judge, the Trojan prince Paris, a bribe to convince him to choose them. Hera offers power (she's queen of the gods, after all), Aphrodite offers the most beautiful woman in the world to be his wife (Helen, who's—whoops!—already married), and Athena offers to make him the wisest man in the world. Paris chooses Aphrodite, of course, but as one of my middle school students pointed out: "That was really dumb. He should have taken wisdom. If you're smart enough, you could figure out how to get everything else." No one ever accused Paris of being an intellectual giant.

In vengeance for the slight, Athena becomes a fierce defender of the Greek army, and is involved in one of my favorite minor episodes in the Iliad. With Achilles on the bench, Athena decides to invest the clever Diomedes with divine strength and send him out to kill Trojans. But, she warns him, he should be very careful whom he's stabbing—there are gods fighting in the fray, and he wouldn't want to accidentally attack a god. Unless, that is, he sees Aphrodite. He can go ahead and stab her. (Yet again: don't get on Athena's bad side).

Paris awarding the golden apple to Aphrodite (Athena's on the far right, looking annoyed)

Diomedes wades into battle, suffused with the goddess' power, and finds himself facing the Trojan hero Aeneas, son of Aphrodite. He beats Aeneas badly, hurling a rock at him that crushes the Trojan's hip. When Aphrodite swoops down to bear him away to safety, Diomedes sees his chance and stabs her in the wrist. Aphrodite screams and abandons her son, fleeing off to Mount Olympus (luckily for Aeneas, Apollo comes to his rescue). Aphrodite sobs in her mother Dione's lap, while Hera and Athena look on scornfully. Athena taunts her by asking if she scratched herself with a pin. I kind of have to go with Athena on this one—Aphrodite shows herself to be pretty wimpy, given that the wound heals almost instantly.

A little later in the fight, Athena aids Diomedes again, tossing his charioteer out in order to take the reins herself. She leads him against Ares, using her power to help him stab the god of war–who goes up to Olympus to complain to Zeus that he lets Athena get away with anything. (Zeus retorts that Ares is his least favorite child, and should stop whining).

Bust of Athena, photo by Vitold Muratov

Athena makes some wonderful appearances in Zachary Mason's "Lost Books of the Odyssey," but sadly I don't know of any other modern novels that feature her. Let me know if you do!

I wish you all a very wise week!

February 20, 2012

Myth of the Week: Psyche and Eros

Monday, February 20th, 2012

Maybe it's just the dark and cold of February getting to me, but it seems like a good time of the year for love stories. This one comes at the suggestion of the lovely Kayleigh and Sam: the story of Psyche and Eros.

Eros and Psyche has proved one of most enduring and beloved Greek myths. Partially, I think its popularity stems from the combination of its specific, romantic story, and its allegorical implications— the two main characters have names that literally mean "Soul" and "Desire." So you can see why those interested in myth and psychology, like Carl Jung, loved it.

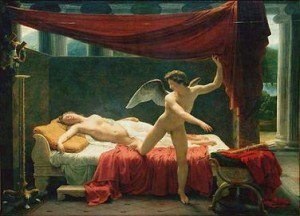

Eros and Psyche, by a favorite painter of mine, William-Adolphe Bouguereau

For me the story has always felt more fairy-tale than Greek myth. There are jealous sisters, quests of penance, helpful animals, and a supposedly-hideous monster who turns out to be a handsome god. And, as I noted last week, it is one of the few love stories in mythology with a happy ending. The first extant version of it is by a Roman author, Apuleius, but I'm going to use the Greek names throughout (Eros, rather than Cupid, and Aphrodite, rather than Venus).

The story begins with Psyche, a girl so surpassingly beautiful that the neighbors mistake her for Aphrodite and begin to worship her. This only makes Psyche miserable. Not only is she worried that Aphrodite will be angry with her, she's desperately lonely—her beauty is so intimidating, no one will speak to her. She envies her plainer sisters, who each have husbands and families already.

Aphrodite, goddess of love, and her winged son Eros

This doesn't, of course, stop Aphrodite from being enraged when she hears that her rightful worship is being diverted to a mere mortal. She orders her son, Eros, to go and punish the girl by—a touch of Midsummer Night's Dream—making her fall in love with the most hideous creature imaginable. One of the creepiest details of the story is that, after asking him this, Aphrodite kisses her son "with open mouth for a long time." I guess this is what it's like if your mother is the goddess of love?

Meanwhile, back on earth, Psyche's father has consulted Apollo's oracle about what he should do with his beautiful, but apparently unmarriagable daughter. The oracle tells him that Psyche is destined to marry a hideous, flying snake-creature, and the only way to appease the angry gods is to tie her to a mountain crag and let the creature carry her off. The father obeys, dressing his daughter in bridal finery, and sending her to the mountain.

Eros and an enraptured Psyche

Up on the rock, it turns out that there isn't a snake-creature after all, only the (invisible) god Eros, waiting to avenge his mother. But instead of punishing Psyche, he falls madly in love with her. He tells the west wind, Zephyr, to waft her to his palace—a beautiful place of gold, marble and jewels, filled with luxuries and helpful invisible servants. Definitely some strains of this filtered into the story of Beauty and the Beast. The servants feed and bathe the girl, then lead her to her bedroom and let her know that their master, her new husband, will come to visit her that evening. Which, if this were a realistic story, would be a frightening announcement.

Cupid and Psyche as husband and wife

But this is a fairy-tale, and we know that the husband is Eros, and that Psyche will of course fall in love with him–he is the god of desire, after all. The two consummate their love that night, though in total darkness because Eros has forbidden her to look at him. An interesting moment that could be taken a lot of different ways, the most appealing of which is that love is about trust: having faith in your feelings for the other person, rather than obsessing about appearances. But (maybe it's the cynic in me) I can't ever completely ignore the other interpretation—that Psyche, as a woman, is supposed to blindly trust her husband, and obey him without question.

Eros, with sleeping Psyche. I find this painting hilarious. The adolescent expression on Eros' face is amazing.

And so it goes. Psyche spends her nights with her beloved but unseen husband, and her days alone (except for the invisible servants). After a time, she asks her husband if she may invite her sisters for a visit. He warns her to be careful of them, but innocent, trusting Psyche doesn't believe him. Already envious of their sister's greater beauty, the two are enraged by her further good fortune. They decide to try to destroy her relationship with her new husband, by implying that he's a hideous monster. They convince her that she must get a look at him, so she can know for sure.

Psyche and Eros

Of course, on some level, Psyche does already know—after all, she's been sleeping with him at night and it's difficult to mistake a handsome human body for a hideous snake creature when everybody's naked. But the moment still resonates. It speaks to a universal human experience—struggling to trust our own understanding, in the face of familial or societal pressure. It is always harder to do than we think it will be. If I had been Psyche, I probably would have looked.

That night, Psyche waits until her husband has fallen asleep, and lights the oil lamp. She finds not a hideous monster, but a divinely beautiful young man. She is so entranced that she doesn't notice the hot oil begin to spill from the lamp. It falls on Eros, waking him. He leaps from the bed, tells her that she has ruined everything, and flies away. Without faith there can be no love.

Psyche, lifting the lamp to see her lover, and waking him with the spill of hot oil

Poor Psyche wanders from place to place, searching in vain for her husband. Her sisters are delighted by her misfortune, and both rush to the crag where Psyche had been carried off. They leap from it, expecting to be wafted to the god's bedchamber to take her place. Instead, they smash on the stones below. Of all the ends of evil sisters in fairy-tales, that's definitely one of the more decisive.

Psyche decides to pray to Aphrodite, hoping that she will intervene with her son. But Aphrodite is still angry about the girl's beauty, and jealous of her son's love for her. She says that she will help the girl, as long as Psyche performs several tasks as penance. Here is where the fairy-tale really takes hold: the first task is to sort a huge pile of mixed grain over night, an impossible task for one girl. But not for some valiant, friendly ants! They sort the entire pile for her.

Eros, leaving Psyche's bed

Aphrodite is angry and tells Psyche that she will next have to collect the fleeces from a special flock of vicious sheep (I'll take your word for it, Apuleius. But I do think that another animal would have been more convincing.). Bravely, Psyche sets off to do so, but is stopped by a helpful reed (yes, a reed) who whispers to her that the sheep are too dangerous to be approached, but if she waits a little, she can collect the fleece that they leave behind on bushes. She does so, and once again, Aphrodite is angry.

The quests continue, culminating in Aphrodite sending Psyche down to the underworld to fetch some of Persephone's beauty. Psyche, in despair, knows that she cannot succeed, and goes to a high tower to throw herself off—but the tower prevents her, and gives her valuable advice about how to slip into the underworld past Cerberus (feed him a seed-cake), and then slip out again. Most importantly, the tower warns, she is not to look in the box of "beauty" under any circumstances.

Psyche traveling through the underworld

I think we can see where this is going. Psyche, wanting her husband to love her again, does indeed look in the box of beauty, hoping to take a little for herself. But instead of beauty, what she finds is deathly sleep—and she falls, unconscious, to the ground.

Eros rushing to the aid of his fallen Psyche

At last, Eros takes pity on his poor Psyche. He appeals to Zeus, who uses his power to wake her from her sleep, and to make her immortal. She and Eros are reunited, and even Aphrodite is reconciled to her new daughter-in-law, acknowledging that while Psyche is imperfect, her dedication to her husband cannot be doubted, since she was willing to go into death itself to win him back. The two live happily every after, and have a daughter, whose name is Hedone (pleasure).

As you can see from above, the story made a wildly popular subject for artists. C. S. Lewis also wrote a fascinating version of this story from the point of view of one of the evil sisters. It has the great title Till We Have Faces.

Finally, the loveliest bit of linguistic trivia I know: in Greek, the word for soul—psyche—also means butterfly.

February 14, 2012

New Foreign Editions

I am thrilled to be able to announce two new foreign editions of The Song of Achilles. The first is with the wonderful Netherlands publisher, Meulenhoff Boekerij, and the other is with the equally terrific Pensamento, in Brazil. I couldn't be happier about them both, and am very much looking forward to seeing how Patroclus sounds in Dutch and Portuguese!

February 13, 2012

Myth of the Week: Baucis and Philemon

Monday, February 13th, 2012

There are two problems with romance in Greek mythology. The first is that many of the so-called "love" myths are anything but. For instance, I've often seen Daphne and Apollo classed as a love story. But, of course, Daphne is fleeing from Apollo, and only narrowly escapes being raped by him. So, there's that.

The second problem is that the stories which are about genuine love are almost uniformly tragic. The list of these is quite long: Hector and his beloved Andromache, Achilles and Patroclus, Pyramus and Thisbe, Orpheus and Eurydice, Hero and Leander, Apollo and Hyacinthus, Atalanta and Meleager, and on, and on.

Hector, Andromache, and their infant son, Astyanax

But there are a few—a very few—stories that are both romantic and happy. The best known ones are Psyche and Eros (more on that soon), and my favorite: the story of Baucis and Philemon.

At first glance, Baucis and Philemon make non-traditional romantic leads. For one thing, when the story begins they are bent over with age. For another, they are poor commoners, while the lovers in Greek myths tend towards aristocrats or divinities. Thirdly, there is no question of "will they or won't they?" Baucis and Philemon have been married for years, living happily together in the same humble, straw-roofed dwelling.

Their rustic routine is interrupted by two weary strangers, knocking at the door looking for food and shelter—they have been turned away, they say, by all the finer houses in the neighborhood. Baucis, the wife, and Philemon, the husband, welcome the two men warmly. Even though their resources are scant, they set about cheerfully making the best of what they have. One of my favorite parts of this story is the elaborate preparations: Baucis scrubbing the dinner table with mint to make it smell fresh (good idea!), and Philemon carving the meat.

Baucis and Philemon prepare a humble welcome for their guests

We also get a lovely description of their rustic dinner, which sounds much more appetizing than many of the absurd Greco-Roman dishes that have come down to us (larks' tongues, eel pastries, jellyfish). Instead there are:

"olives, and cherries preserved in wine…, endive and radish, cheese, eggs roasted in the hearth-embers… nuts, and figs scattered among wrinkly dates, plums and apples fragrant in their broad baskets, grapes collected from their purple vines, and a gleaming honeycomb."

Baucis and Philemon at dinner with their mysterious guests

YUM. But even more important than the food is the care that the old couple uses in preparing it, the generous goodwill they show in laying out the best they have. Hospitality was a virtue in the ancient Greek world—guests were sacred to Zeus himself. Myth texts often note that this is because you never knew when a stranger might prove to be a god. But Baucis and Philemon aren't so calculating. They are reflexively kind, not fearfully so. There are also some lovely descriptions of the couple working together in practiced synchronicity—carrying the wood, putting a wedge under the wobbly leg of the table, setting out the earthenware plates. Ovid beautifully captures the house's domestic harmony and contentment—these are people at peace with themselves.

The four sit down to the meal. But as they eat and drink, they notice that the wine bowl, filled with the best humble vintage the couple has, never seems to empty. No matter how often Baucis and Philemon pour for their guests, the bowl is always brimming. Beginning to suspect that their guests may be gods, they are fearful that they haven't done enough to please them, and decide to kill their beloved pet goose to add to the dinner spread. However, slow with age as they are, they cannot catch him, and end up pursuing him around and around the house.

Baucis chasing the troublesome goose, while Zeus looks on.

Many people have seen a sort of humor in this moment—the old couple stumbling after their nimble goose. But to be honest, I have always found it sad. This good old couple is afraid for their lives, and are desperately trying to offer the only thing they have left to appease the gods.

Luckily, all ends well. The goose runs to the two travelers for sanctuary, and they stand to reveal themselves as, yes, gods: Zeus and Hermes himself. They tell the old couple to forget about the goose, and to come with them up the mountain to its top. The couple obeys (Ovid offers a nice detail about them leaning on their walking sticks), and when they reach the top and turn around they see that their old neighborhood, with all its houses and people, has been swept away. Only Baucis and Philemon's house remains, which—even as they look—is transformed into a beautiful, marble-and-gold temple.

It is a miraculous and upsetting moment. Yes, Baucis and Philemon have been saved but all their neighbors are dead. For the sake of the happy ending, Ovid does not dwell on this, beyond mentioning that the couple grieves for those who have been lost. But it is hard to forget the swift and unforgiving punishment—there is no second chance, if you displease the gods.

Zeus and Hermes lead the old couple up the hill and out of danger.

Fortunately, the gods are pleased with Baucis and Philemon. Zeus offers to grant the pious, good-hearted pair whatever they wish. The two whisper together for a moment, and then Philemon announces that they would like to live out their lives as servants of the gods in the new temple. Further, because of their great love for each other, they do not wish to have to live alone, without the other. They ask the gods to let them die at the same moment:

"Let the same hour bear us both off; let me never see the tomb of my wife, nor be buried by her."

Zeus agrees, and the couple spend many joyful years together in their new home. Then, one day, as they stand outside their temple talking of their lives, they notice something strange—branches are beginning to grow from their heads, their hair is transforming into leaves. With their last breaths, they call out their farewells to each other. A moment later, two trees, an oak and a linden tree, stand where the old couple was. And, just as in life, the two are bound together, sprung from the same trunk, their branches entwining into eternity.

A sweet story. May we all be as lucky in love as Baucis and Philemon.

February 8, 2012

Myth of the Week: Pyrrhus, part II

Wednesday, February 8th, 2012

In my last post, I talked about Vergil's Pyrrhus as the epitome of the very worst of human behavior. Happily, Sophocles' Pyrrhus is the opposite: a celebration of our most conscientious, best selves.

The play in which he co-stars, Philoctetes, is cleverly set before Troy falls, before the death of Priam. This allows Sophocles to avoid the entire second half of Pyrrhus' life—almost as if he is offering a "reboot" of the young man's story, an alternate line of destiny. Certainly, by the play's end, it is difficult to imagine Pyrrhus killing Priam as he does in the Aeneid.

The play begins with a prophecy that Troy won't fall unless Heracles' bow fights on the Greek side. Unfortunately, Heracles' bow is with Philoctetes, whom Odysseus had abandoned on an island with a festering wound ten years earlier. Odysseus must go get the old soldier and persuade him to put aside his resentment and aid the Greek cause. He cleverly decides to bring Pyrrhus with him: as Pyrrhus was the only man who didn't come with them to Troy originally, he is also the only man not implicated in Philoctetes' abandonment—so Philoctetes may be persuaded to listen to him.

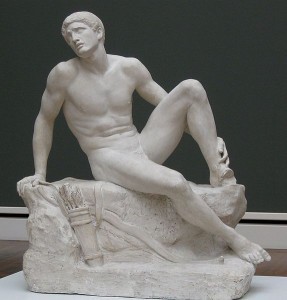

The wounded hero Philoctetes, with his bow and quiver of poisoned arrows from Heracles. Photo by Rufus46

Odysseus tells Pyrrhus that he is to pretend that he hates the Greeks, in order to gain Philoctetes' trust. If the old soldier will not co-operate, Pyrrhus is supposed to wait until he falls into a festering-wound fit, and then either steal the bow and arrows, or carry him off to the boat while unconscious.

Given what we know of Pyrrhus from Vergil, we would assume that he happily agreed, pausing only to club Philoctetes with somebody's child first. But Sophocles' Pyrrhus is a different man. He is appalled by Odysseus' treachery, and reproaches him for using deceit. Such tricks, he says, are not in his nature, just as they were not in his father's. He refers here to Achilles' reputation for honesty, demonstrated by his famous line in the Iliad that he "hates like death the man who says one thing, and hides another in his heart." Such a man, of course, is Odysseus. He and Achilles are perfect foils—youthful honesty-to-a-fault balanced against practiced, shades-of-grey pragmatism. Sophocles here has Pyrrhus take his father's place as Odysseus' opposite.

Yet, because he is young, and impressionable—and because Odysseus is a master at persuasion—Pyrrhus reluctantly agrees to the plan. This is the genius, I think, of Sophocles' characterization: Pyrrhus is a young man looking to find his way in the world, without a father's guidance. Although his instinct is to spurn Odysseus' methods, he has no other model to adopt, besides a vague rumor about his father's values—a father he has never met. Maybe Odysseus is right, after all. I think it perfectly captures those first, unsure steps into adult identity.

The embassy to persuade Philoctetes. To the left is Odysseus, and the right is Diomedes (who, in some versions, accompanies Odysseus in Pyrrhus' place)

But Pyrrhus is in luck, because for a young man looking for a role model, it is hard to do better than Philoctetes. The two meet, and Pyrrhus finds himself instantly drawn to the older man's plight, character and dignity. When the moment comes to defraud Philoctetes, Pyrrhus hesitates, torn between his duty to the Greeks and his own instincts. Movingly, he exclaims, "I wish I were back in Scyros!" He feels tainted by the moral compromises of the adult world, and longs to return to the simplicity of childhood. Yet, he cannot return, and is pressed hard on both sides by Odysseus and Philoctetes.

Sophocles stacks the deck against Odysseus a bit here—for although we see Pyrrhus' dilemma, the right choice seems obvious—if he is to keep his soul, he must help Philoctetes, and reject Odysseus. But playing devil's advocate, let's examine Odysseus' motive, which is, always, to serve the army's greater good, and to get himself home again safely. If Pyrrhus forces Philoctetes to come to Troy, Philoctetes will be miserable—but an entire army's worth of soldiers will be able to return home again. In the Iliad, we see the dire consequences of Achilles setting the personal over public good—what does it mean to save a single person at the expense of an entire nation?

Sophocles, however, doesn't make Pyrrhus suffer the consequences of his choice: as soon as he has agreed to help Philoctetes, the god Heracles appears to pacify his old companion, and order him to Troy. It is almost as if the entire episode were an elaborate test, a moral gymnasium designed to help an young man practice his path.

Sarah Bernhardt as Hamlet. Photo by James Lafayette

Pyrrhus—both Pyrrhuses—had an interesting afterlife, including a notable cameo in Shakespeare's Hamlet. When the players arrive, Hamlet recites a speech about Pyrrhus' killing of Priam, where Pyrrhus stands over Priam with his sword raised and, for a moment, "does nothing." Here Pyrrhus becomes a stand-in not only for Claudius—killer of the old King—but for Hamlet himself, stuck in his own inaction.

For a more recent portrait of Pyrrhus, I would recommend Mark Merlis' audacious novel, An Arrow's Flight, which tells the story of Pyrrhus' struggle to separate himself from the reputation of his bloody and distant father. I admire this novel not just for its storytelling, but its flat-out daring: Merlis takes the story of Pyrrhus (drawn mostly from Sophocles' play), and puts it straight into the modern world, while still retaining all the ancient Greek structures, the gods included.

And, by the way, Pyrrhus also makes an appearance in The Song of Achilles. My take on him is decidedly Vergilian.

Thanks so much to myth-lover Susanne for the terrific suggestion! Next week: Ancient Greek romance, just in time for Valentine's Day….