Madeline Miller's Blog, page 6

April 19, 2012

T Magazine, The New York Times

Thursday, April 19th, 2012

In a very different vein than the recent Orange news, The New York Times T Magazine featured me in the April 15th issue on Women’s Fashion. Those of you who know me know that stylishness isn’t really my milieu, so I was VERY grateful that they did all the clothes selection for me! It was a wild and wonderful experience, and included an interview with the terrific Liza Nelson.

Orange Prize Shortlist!

Thursday, April 19th, 2012

I was absolutely thrilled and bowled over that The Song of Achilles was shortlisted for the Orange Prize. It is a huge honor for me to be in the company of such amazing authors: Ann Patchett (State of Wonder), Cynthia Ozick (Foreign Bodies), Esi Edugyan (Half-Blood Blues), Georgina Harding (Painter of Silence) and Anne Enright (The Forgotten Waltz).

By total and wonderful coincidence, I was actually with Ann Patchett on the day the shortlist was announced, doing a reading at her bookstore, Parnassus Books. Ann was so gracious and lovely, and I also got to meet her Parnassus partner, Karen Hayes, and the Parnassus staff, all of whom were just terrific. A giddy, unforgettable evening!

If you love having signed books, you might want to check out Parnassus’ First Editions club–you don’t have to live in Nashville to join!

April 16, 2012

Ancient Greek and Modern English

Monday, April 16th, 2012

I’ve had a busy past few weeks on my US booktour, with lots of terrific events, and lots of wonderful things still to come. In particular, I am thrilled to be going to Ann Patchett’s bookstore, Parnassus, on Tuesday for the kickoff of her First Editions club. She is fabulous, and getting to see her and visit her store is a literary dream come true. Then this weekend I get to hang out at the Books on the Nightstand Vermont Booktopia retreat, with a whole bunch of other book-lovers and authors. After that, it’s on to California!

Unfortunately, amidst all this I haven’t had the chance to give Atalanta, my chosen myth of the week, all the attention she deserved. So rather than short shrift that eminent lady hero, I thought I would push her off to next week, and have this week’s post be a bit different.

Not very horse-y, but pretty cute. Photo by Frank Wouters

For some time now, I’ve been thinking about doing a series about the delights of ancient Greek-derived English. When I first started studying Greek, one of my absolute favorite parts was realizing that so many English words had these old, secret roots. Learning Greek was like being given a super-power: linguistic x-ray vision. Or like in CSI, when they shine the blacklight on the carpet. A silly, ordinary word like hippopotamus sprang suddenly to life as “river horse.” A terrible description, to be sure, but a fascinating one. Is that really how the Greeks thought of them?

I still love these Greek etymologies just as much as I did back then, and thought I would share five of my favorites.

Amazons fight Greeks on the side of a sarcophagus in Thessaloniki. Photo by Anton Lefterov

Sarcophagus. By the time I got to my high school Greek class, this word and I were old friends. I had been very fortunate as a child to live near the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, and to have a mother who was excited to take me there. My favorite exhibits were the Greeks, Romans, and Egyptians, and between the three I saw lots of sarcophagi. I had always assumed that the word was Egyptian, because it sounded mysterious to me, so it was a thrilling moment to realize it was actually Greek: from sark-, meaning flesh, and phag- meaning eating. The sinister name came from the fact that the sarcophagi were often cut from a type of limestone, which was thought to help “devour” the bodies.

When a person in the ancient world was ecstatic, she was actually possessed—so consumed by the god’s presence that she was out of her mind, or standing (stat-) outside (ek-) herself. It’s interesting to me that the word has been now entirely stripped of those religious associations, and come to mean simply the most extreme and delirious type of happiness.

A female follower of Bacchus, perhaps preparing to enter religious ecstasy.

The ancient Greeks were lovers of the human form, especially when it was fit and naked. Ancient athletes both worked out and competed in the nude, and the place where they exercised became known as “the naked place,” or gymnasium, from gymnos, the word for naked. Something to contemplate next time you’re on the elliptical….

Petrichor is one of my favorite words of all time, because it gives a name to something we’ve all experienced: that smoky-mineral scent that rises from the earth after rain. It’s derived from the Greek for rock (petr-) and divine blood (ichor). By the way, that “petr-“ shows up elsewhere in English, in the word petrify, and the name Peter. Jesus makes a clever play on words when he says that the apostle Peter is the rock upon which he will build his church.

An apatosaurus skeleton, from the Carnegie museum. Photo by Tadek Kurpaski

I’m not sure what the cut off age is for growing up with Apatosaurus versus Brontosaurus, but I definitely missed it. As a child, I loved my “Brontos” and was very sad to learn that they didn’t, in fact, exist. It’s even sadder because brontosaurus has such a wonderful, evocative name: “thunder lizard.” It used to make me shiver to imagine a creature so big its steps sounded like a storm. But the new improved version, apatosaurus, has a pretty good name too: deceiving lizard. The story goes that this is because paleontologists were “tricked” into mis-identifying it as brontosaurus, but apparently the truth is that the name apatosaurus is actually the older of the two (which is why it won out). It derived from the fact that some of its bones were deceptively like the bones of other dinosaurs.

Have an ecstatic and etymological week!

April 13, 2012

Video

Along with the UK paperback release, Bloomsbury has created a short video of me discussing The Song of Achilles.

April 12, 2012

UK Paperback, and Hay Festival

Thursday, April 12th, 2012

The UK Paperback of The Song of Achilles is officially released today! Here's a peek at the new cover:

UK Paperback Cover

In other thrilling news, I will be coming to the UK in June to speak at the Hay Festival. More details on that and other possible appearances coming soon!

April 9, 2012

Myth of the Week: Atlas

Monday, April 9th, 2012

As a child in New York City, I had numerous opportunities to walk past the huge statue of Atlas holding up the world in front of Rockefeller center. I would always wonder: "But what is Atlas standing on?"

Statue of Atlas, at Rockefeller center. Photo by Sami Cetinkaya

Though I didn't know it at the time, it was an age-old question. If Atlas, or four elephants, or a turtle (all in various mythologies) are holding up the world, what's holding them up? In a possibly apocryphal story from modern physics, a scientist has just finished delivering a lecture about the nature of the cosmos, and an old woman raises her hand and says that he's wrong, the world is really balanced on the back of a giant turtle. The scientist asks, "Then what's the turtle balanced on?" The old lady famously retorts, "It's turtles all the way down." Except in this case, I guess the answer is: "Atlases all the way down."

As I got older, and read more of the mythology, I realized that the ancient Greek version of this story is a lot more clear than that. In the original Greek, Atlas isn't holding up the world at all, he's holding up the sky. Ah-ha! Now that made sense.

Statue of Atlas with the World

Atlas was a second-generation Titan, the race of gods that ruled before Zeus and his Olympian kin took over. His father was Iapetus, which makes him the brother to one of my favorite mythological figures of all time, Prometheus. From birth Atlas was exceptionally strong, and when war broke out between the Titans and Olympians, Atlas took vigorous part on the Titan side. Too vigorous, as it turns out, because after the Titans were defeated, Zeus felt threatened by Atlas' mighty strength, and sentenced him to hold up the vault of the sky for all eternity. No wonder his name is derived from the Greek word for "enduring."

For aeons, Atlas stood in the garden of the Hesperides, at the far edge of the world, holding up the sky. He wasn't entirely alone: there were the nymphs of the garden (the Hesperides), who tended to a golden apple tree, which was also guarded by a fearsome dragon. And sometime during all of this (probably before the whole holding up the sky thing) Atlas managed to have children, including the goddess Calypso, who would later seduce Odysseus on her enchanted island, and Maia, who was the mother of Hermes.

Hercules holding up the World, with Atlas beside him

Atlas had visitors too, including Heracles, who needed the golden apples to fulfill one of his famous labors. Heracles managed to slay the dragon guarding the tree, but needed a god to do the actual picking for him. He offered to take the great weight of Heaven off of Atlas' shoulders for a few moments, in return for the god retrieving the apple for him. Atlas gratefully agreed. But after picking the apples, Atlas realized that he didn't want to go back to literally carrying the weight of the world.

No problem, Heracles said. He was happy to keep holding up the heavens, but would Atlas mind taking it back for just one second so he can make a pad for his shoulders with his lionskin?

Oh, Atlas. The brains of the family definitely went to Prometheus, because the Titan agreed. I always feel sorry for Atlas at this moment, because his actions, however, foolish, come from empathy. After all, who understands better the crushing and terrible weight of the sky? He's one of those people about which great movies are made—they commit a crime out of desperation, but don't really have what it takes to follow through. Heracles picks up the apples, and leaves the Titan to his suffering.

NASA photo of the Atlas Mountains

In a later story, Perseus uses Medusa's head to turn the Titan into stone, creating the Atlas mountains. In many of the retellings this is meant to be Perseus retaliating (Atlas won't let him pass), but it seems like a kindness to me. I know if I had to hold up the sky, I'd definitely rather be a mountain than a person.

Because of his association with holding up the sky, Atlas also became linked to the poles and the constellations. In fact, in some versions of the myth he's an expert astronomer and map-maker, which is what gives us our word atlas today. For a modern interpretation of the Atlas story, check out Jeanette Winterson's "Weight" which is part of the wonderful Canongate Myth series.

I wish you all a good week, without too much extra weight on your shoulders!

April 2, 2012

Myth of the Week: Arachne

Monday, April 2nd, 2012

One of the earliest Greeks myths I remember is the story of the artist Arachne, whose name means "spider" in Greek. Back then, it seemed fairly standard: hubris, a confrontation with a god, transformation as punishment (to, unsurprisingly, a spider), with some natural explanation thrown in (this is why spiders spin webs!)

A spider's web, with raindrops on it. Photo by Wusel007

But when I got a bit older, and read Ovid's full version of the myth, Arachne quickly became one of my favorite heroines. First of all, she's one of the few ancient females who isn't a princess or beautiful nymph. She's the daughter of a tradesman, a Lydian dye-merchant, with no noble connections, nor extraordinary looks. She is famous, Ovid tells us, for her skill in weaving alone. I particularly love his description of her at her loom—how gracefully and deftly she handles the threads, how the nymphs abandon their fields and forests to come stare in awe. I have always found it so pleasurable to watch someone do something that they are truly gifted at, and Ovid captures that feeling perfectly.

Arachne is relentlessly proud of her excellence, and defiant in the face of attempts to cow her into modesty. She is, she says, as skilled as Athena in her work. Why should she lie and say she is not? There aren't too many heroines in ancient literature who are so single-minded and proud–usually those characteristics are identified with men like Achilles and Ajax. In fact, that comparison does her a bit of a disservice, since her rebelliousness and pride are actually much more deliberate and intellectual than either of those two heroes (much as I love them). A better comparison might be another favorite of mine, Pentheus, the ill-fated King of Thebes, who loses his life standing up to Dionysus. Like him, Arachne dares to criticize the gods, and doesn't back down even when threatened. Foolish? Maybe. But also principled and courageous.

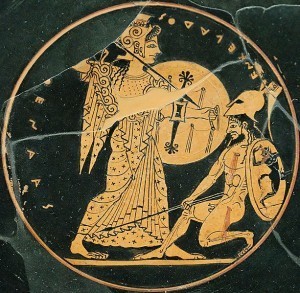

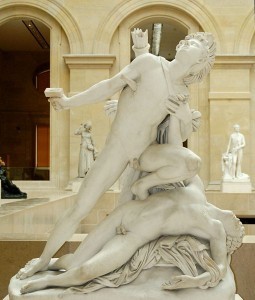

Athena vanquishing the giant Enceladus

The gods, of course, never like to be challenged, and Athena is known for being particularly vicious towards rivals. She decides to pay a visit to Arachne, disguised as an old woman, warning the girl that she must learn to acknowledge the goddess' superiority. But Arachne dismisses her–why should she acknowledge Athena? She hasn't met the goddess, nor seen her weaving. And she has supreme faith in her own powers. "Let her come!" she says. And Athena (the gods do love their dramatic revelations) throws off her disguise declaring "She is here!"

The contest is on. And it's a testament to Ovid's skill as a poet that what should be exceedingly boring (a long, lingering description of the two women weaving) becomes an edge-of-the-seat fireworks display. Ovid spends every bit of his prodigious skill evoking the vivid colors and beauty of the materials, before moving on to the astonishing pictures taking shape on the rival tapestries. Because, of course, this isn't just about beauty: it's an intellectual debate about whether humans have the right to challenge gods.

Athena attacking Arachne, after the contest

Athena's cloth is a gorgeous depiction of the gods in their full glory, looking on at the scene of her triumph over Poseidon in the contest for Neptune. In the four corners of the tapestry, she weaves four admonitory scenes of humans who dared to compare themselves with gods, and the bad ends that each came to. But Arachne's cloth shows something else entirely: not the gods in triumph, but the gods as clowns. Each part reveals the gods behaving badly. There are several episodes of Zeus in goatish pursuit of nymphs, along with other undignified affairs of the immortals. Her message is clear: the gods are not all they say they are; they are ignoble, embarrassing, childish. More flawed, in fact, than humans. Arachne had guts.

When it comes time to judge the quality of the two works, it would have been easy for Ovid to simply have Arachne lose. She is human, after all, and so it would be expected that her work would be lesser. But Ovid doesn't do that. Arachne's work, he says, is utterly flawless. Not even Athena's envy can find a single error in it. The girl, if she hasn't won, has at the very least tied. Athena is utterly enraged–both by the work's perfection, and by its blasphemous content. One might think that as the goddess of reason and intelligence, Athena would find a way to teach the girl a lesson, to argue her into submission. But instead, she only proves Arachne's point that the gods are imperfect and irrational: she tears Arachne's beautiful weaving all to pieces. Can there be a greater testament to Arachne's intellectual triumph? The great Athena is speechless, reduced to a tantrum-throwing child.

Arachne as a spider (a particularly creepy depiction, I think)

In the version of the story that I read when I was young, Athena turns the girl into a spider at this point, as punishment. But the full version is much darker, and more interesting. Athena, after tearing apart the tapestry, seizes the spindle and beats the girl with it. Arachne is now herself enraged, and decides to hang herself. It's a moment that doesn't read very well in our modern world, where suicide is often equated with giving up. But in the context of the ancient world, suicide was what warriors did, when they refused to accept defeat. It said, in effect: only I can defeat myself. And in that sense, it is a perfect fit for bold, uncompromising Arachne.

But Athena is a god, so she gets the last word. She pities the dying girl (I like to think that she finally recognizes the toughness of a kindred spirit), and saves Arachne's life, transforming her to a spider. Arachne is allowed to keep her extraordinary skill at weaving–or maybe Athena lacks the power to take it from her. What Arachne thinks of this we never find out, but Arachne and her descendants continue to spin their beautiful, miraculous creations to this day.

Another famous weaver: Odysseus' wife Penelope at her loom

I recognize that there is, of course, another way to read this story–as a tale of immoderate hubris, of foolish, reckless arrogance. But even read that way, I still can't help rooting for Arachne–the ordinary girl with the soul of a warrior, who was able to beat a goddess.

March 26, 2012

Myth of the Week: Nisus and Euryalus

Monday, March 26th, 2012

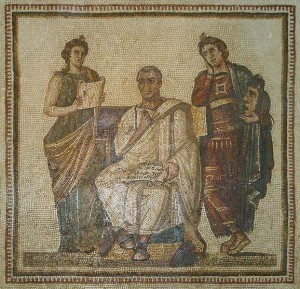

As those of you who are regular readers know, I love the Aeneid. Encountering Vergil's great epic poem in high school was an absolute revelation to me—and it has never stopped being a revelation, no matter how many times I read it. With Vergil, there is always a greater depth, another subtlety, a further shining moment of poetry.

Mosaic of the poet Vergil, flanked by the muses of tragedy and history

Within the Aeneid, one of the saddest episodes (and one of my favorites) is the story of the lovers Nisus and Euryalus. Both are Trojans, refugees from their burned and fallen city, who are following the Trojan noble Aeneas to a new home. Euryalus is described as surpassingly beautiful, and also very young—still in the time of "green youth," beardless, and tenderly connected to his mother. Nisus is a bit older, but still young himself, and deeply in love with Euryalus. When we meet them, it is in a rare moment of leisure: they have both signed up as contestants in a footrace.

Initially, Nisus flashes ahead of the other runners, but then disaster strikes: he slips on the grass, blood-soaked from the sacrifice, and tumbles to the ground. Salius, the Trojan in second place, surges into the lead; Euryalus is close behind. But Nisus knows how much it would mean to his beloved to triumph. He trips Salius, and Euryalus finishes first. Understandably, Salius complains about Nisus' cheating, and the good Aeneas ends up awarding all three of them prizes. It's a slight scene—sweet and almost comic. But given what comes later, it also carries strains of darkness. We see already how deep Nisus and Euryalus' bond runs—and we see that Nisus will do anything for his lover.

Ancient footrace, in armor. Photo by Matthias Kabel

When we see them next in book IX, games have been replaced by bloody war. The Trojans have arrived in Italy, only to find themselves opposed by a native Latin force. Aeneas has gone off to look for allies, leaving the Trojan forces besieged by the Latins. Nisus bravely proposes a night raid, which Euryalus insists on joining. Vergil again emphasizes the depth of feeling they have for each other, the "single love between them." Nisus tries to convince Euryalus to stay behind, fearing for his safety, but Euryalus won't let his beloved go alone.

The scene that follows is a brutal one: the two young men venture into the sleeping camp, and begin killing all the men they can find. It's a strange mix—as if Achilles and Patroclus had been possessed by the spirits of Odysseus and Diomedes. Nisus is like "a hungry lion" as he tears through the sheep-like, helpless Latins; Euryalus is no less vicious. Vergil, always sensitive to the cost of war, lingers a moment over the victims, who are themselves beautiful young men with their own stories, and their own families who will mourn them.

Euryalus, photo by Marie-Lan Nguyen

As dawn creeps near, Nisus urges Euryalus to leave off slaughter and make their escape. Euryalus agrees, stopping to gather a few pieces of armor as his spoils, including a beautiful helmet. But as they flee the camp, the polished metal of the helm catches the moonlight, alerting a group of Latin horsemen, who immediately give chase. Nisus and Euryalus plunge through the woods. Nisus, who grew up in the mountains, escapes; Euryalus does not. When Nisus realizes he has lost his friend he immediately races back, only to see Euryalus being taken captive. Hurling his javelin, he kills one guard, then another. The Latins, enraged, prepare to stab Euryalus.

It is a terrifying moment. Vergil keeps us with the desperate Nisus, who bursts from the woods screaming that they should attack him instead, that Euryalus is blameless. But it is too late. The Latins stab Euryalus, whose slumps forward like "a blood-red flower, cut by a plow." Nisus flings himself among them, desperate to kill the man who killed his lover, before he himself is slain. With his last breath, he falls upon his beloved's body.

Nisus, over the fallen Euryalus. Photo by Marie-Lan Nguyen

Vergil does not stop the story there. The angry Latins take their revenge, cutting off the heads of the young men, and sticking them on spikes. For all their bravery and tragic love, we can't help but see that Nisus and Euryalus' night-raid has single-handedly escalated the war's brutalities. Vergil also does not forget Euryalus' mother, whose grief-stricken lament for her lost son is perhaps the most heart-breaking of all.

One of the things I love most about Vergil is his profound sympathy for human nature. Nisus and Euryalus aren't idealized heroes, but flawed, and very real young men, with maybe more courage than good sense. Vergil's great heart mourns for their lost youth and honors their love, even stepping outside the bounds of his narrative to deliver a moving epitaph:

"If my song has any power, no day shall ever remove you from memory."

March 19, 2012

Myth of the Week: Centaurs

Monday, March 19th, 2012

If ancient Greek mythology had a consistent villain, it would definitely be centaurs. With the exception of the wise and kind Chiron, these half-horse half-man creatures were depicted as bestial, drunken, lecherous bullies strewing chaos and strife wherever they went.

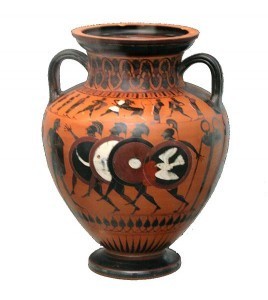

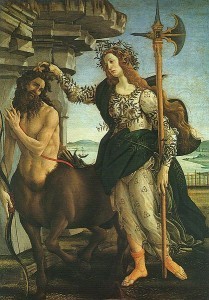

The goddess Athena with a centaur

The origins of Centaurs (or Kentauroi) are obscure. The most common story seems to involve the wicked king Ixion, who tried to rape the goddess Hera. At the last minute, however, Zeus substituted a cloud/nymph (depending on the story) named Nephele. She bore him a monstrous child, Kentaurus, who was either the first centaur, or who mated with horses and produced the first centaur. Ixion, meanwhile, was bound to a flaming wheel, and banished to the pit of Tartarus to suffer alongside Tantalus and Sisyphus.

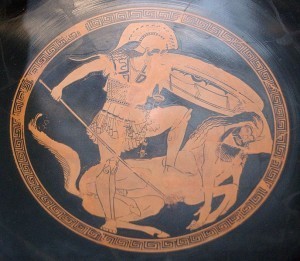

One of the most famous stories of centaur misbehavior is at the wedding of the Lapith king Perithoos, best friend of Theseus. Perithoos invites the centaurs to the wedding, but after consuming alcohol, they become feral, attempting to carry off the bride and the other women. A huge battle ensued, one that was quite popular in art—the Parthenon metopes (large marble friezes on the outside of the building) take this battle as their subject. Such depictions with centaurs became so popular that they actually had their own name—"Centauromachies" (literally, centaur fights).

The fight between the Lapiths and the centaurs

A fascinating side-story about the Lapith/centaur battle involves the unusual hero Caeneus, who was born a beautiful woman, named Caenis. She was raped by the god Poseidon, who after offered to grant her any wish. She wished to be transformed into a man, to escape further persecution. She–now he–became one of the greatest warriors of the Lapiths, and couldn't be killed by normal means. In order to defeat him, the centaurs were forced to pile giant fir trees and rocks on top of him, until he was literally forced into the earth by their weight.

Maybe the most famous centaur story is the one about Heracles and his wife Deianeira. The two arrive at the river Evenus, where the centaur Nessus has set himself up as the ferryman. Heracles boosts Deianeira only Nessus' back, but rather than taking her over the river, the centaur starts to run off with her. Heracles pulls out one of his hydra-poisoned arrows and shoots Nessus, who collapses, thankfully not on Deianeira. He whispers to her his apologies and says that she should gather up a bit of his blood. Then, if she ever doubts her husband's faithfulness, she can give him some of it, and it will make him love her again.

A warrior conquering a centaur

Unfortunately, the next part of the myth doesn't exactly cover Deianeira in glory. Why she thinks it's a good idea to listen to anything her would-be rapist would say is beyond me. But she does indeed gather some of his blood—which by this point (unbeknownst to her, but knownst to Nessus) has mixed with the poison from the hydra-arrow. And, of course, a little while later Deianeira does become jealous that Heracles isn't paying enough attention to her, and does indeed slip him some of the blood. The poison causes Heracles agony so extreme that all he wants is to die. He builds himself his own funeral pyre (tough to the end), and climbs on it. None of his friends will light it, except for the loyal Philoctetes. Heracles is at last released from his pain, and Nessus, in death, has his revenge.

A vicious human/centaur fight

A final tale of centaur-menace concerns the swift-footed hero Atalanta. She is hunting in the woods one day when she is accosted by two centaurs. Single-handedly, she dispatches both of them, and later goes on to participate in the Calydonian Boar Hunt. She's definitely going to be an upcoming Myth of the Week.

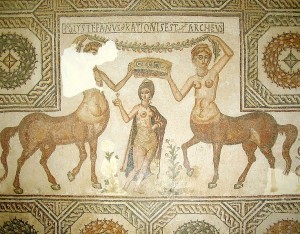

Mosaic with two female centaurs (surrounding the goddess Venus)

Although I never think of centaurs as female, they did appear in some later art (see above). In fact, they were renowned for their beauty. Can I help it if I think of Leslie Knope's centaur likeness in Parks and Recreation? I don't watch much TV so this doesn't mean much, but that show is one of my absolute favorites.

I wish you all a very happy, sunny week. I'm breaking out the shorts!

March 17, 2012

New York Times Bestseller!

I am thrilled to announce that The Song of Achilles debuted in the US at #31 on the New York Times Bestseller list! I am so grateful to all of you who have supported this book–thank you for making this author's dream come true!