Natan Slifkin's Blog, page 184

April 20, 2012

Shlissel Challah: Serious Segulah or Pagan Piffle?

On the Shabbos following Pesach, there is a custom of some to bake "Shlissel Challah" - challah with the design of a key, or challah with a real key actually baked into it. It is alleged to be a segulah for parnassah (sustenance).

Needless to say, this is not exactly consistent with the rationalist approach to Judaism. Parnassah is to be obtained via hishtadlus coupled with good-old-fashioned prayer. And there is a fascinating study of this topic on a YBT-affiliated website which demonstrates that shlissel challah is rooted in Christian and/or pagan practices. Keys used to be manufactured in the form of a cross, and at Easter time, Christians would bake them into a rising loaf of bread to symbolize Jesus rising from the dead. (This is the source of the British "hot cross buns.")

Yet, unlike the hyper-rationalists, I'm usually not so fervently opposed to such things. There's lots of things in Judaism that originated in foreign cultures; but where something originated is less important than what we've made of it. And segulos are often harmless placebos.

In this case, however, I am a little more concerned, given the wider context. In the ultra-Orthodox community, there is a prevalent message that it is wrong and futile to engage in regular efforts to obtain parnassah (i.e. education, training and work). There is a real risk of people focusing on segulos instead of doing the necessary hishtadlus.

Recently I came across a story in one of the charedi magazines which was not as heartwarming as it first appeared. The letter-writer told of how, several years earlier in the supermarket, a person in front of him paid the entire bill for a needy family, saying that "he needs the merits." After this person died, the letter-writer visited the family and told them of their father's generosity, which surprised them greatly, because they were in financially difficult circumstances themselves. So was this person's deed a selfless and praiseworthy act of generosity, or an irresponsible giving away of money that his own family needed "in order to gain merits"?

(See too my post on The Ring Of Power)

In other news, for readers outside of Israel, this week is parashas Shemini - hyrax week! And, by a remarkable coincidence, hyraxes made the New York Times this week (and Wired Magazine). My own pet hyrax is positively giddy with excitement.

Needless to say, this is not exactly consistent with the rationalist approach to Judaism. Parnassah is to be obtained via hishtadlus coupled with good-old-fashioned prayer. And there is a fascinating study of this topic on a YBT-affiliated website which demonstrates that shlissel challah is rooted in Christian and/or pagan practices. Keys used to be manufactured in the form of a cross, and at Easter time, Christians would bake them into a rising loaf of bread to symbolize Jesus rising from the dead. (This is the source of the British "hot cross buns.")

Yet, unlike the hyper-rationalists, I'm usually not so fervently opposed to such things. There's lots of things in Judaism that originated in foreign cultures; but where something originated is less important than what we've made of it. And segulos are often harmless placebos.

In this case, however, I am a little more concerned, given the wider context. In the ultra-Orthodox community, there is a prevalent message that it is wrong and futile to engage in regular efforts to obtain parnassah (i.e. education, training and work). There is a real risk of people focusing on segulos instead of doing the necessary hishtadlus.

Recently I came across a story in one of the charedi magazines which was not as heartwarming as it first appeared. The letter-writer told of how, several years earlier in the supermarket, a person in front of him paid the entire bill for a needy family, saying that "he needs the merits." After this person died, the letter-writer visited the family and told them of their father's generosity, which surprised them greatly, because they were in financially difficult circumstances themselves. So was this person's deed a selfless and praiseworthy act of generosity, or an irresponsible giving away of money that his own family needed "in order to gain merits"?

(See too my post on The Ring Of Power)

In other news, for readers outside of Israel, this week is parashas Shemini - hyrax week! And, by a remarkable coincidence, hyraxes made the New York Times this week (and Wired Magazine). My own pet hyrax is positively giddy with excitement.

Published on April 20, 2012 02:09

April 18, 2012

The Riddle of the Bears and the Grapes; plus, summer

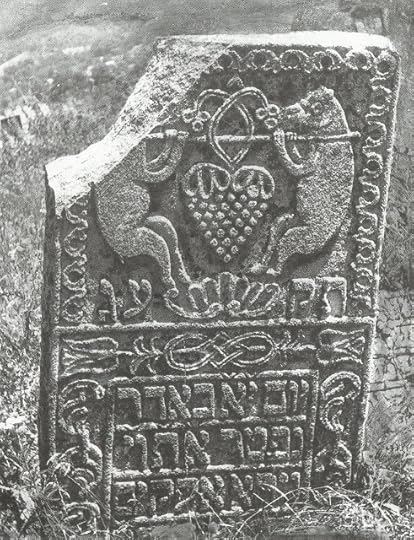

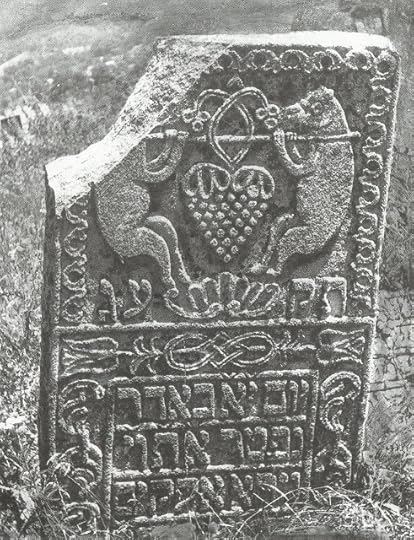

The other day, I picked up what must surely be one of the most arcane books ever published: "Jewish Tombstones in Ukraine and Moldova." It's not likely to ever have been on the New York Times' bestseller list, nor one of Oprah's books of the month. The book is mostly comprised of pictures of these tombstones. Many of them are carved with pictures - menorahs, flowers, animals. Of the animals, the lion and deer are by far the most common. But I was fascinated to find three tombstones, from early 19th century Kishinev and Sadgora, depicting bears standing upright and carrying a cluster of grapes:

From Bear Art

From Bear Art

From Bear Art

From Bear Art

From Bear Art

From Bear Art

(The second tombstone might be argued to be depicting lions rather than bears, given the tails and quasi-manes. However, in light of the person being named Dov, and the other two images, it's probably a mistaken picture of bears.)

What on earth is this about? I've studied the symbolism and significance of bears in Judaism very extensively, and I have never come across any connection to grapes. Google didn't help me, either. Does anyone have any insights?

In other news - I am currently planning my summer lecture tour in the US. I have availability for Shabbos July 21 in the NY region, and July 28 and August 11 in California. If you are interested in arranging a scholar-in-residence program, please write to me.

From Bear Art

From Bear Art

From Bear Art

From Bear Art

From Bear Art

From Bear Art(The second tombstone might be argued to be depicting lions rather than bears, given the tails and quasi-manes. However, in light of the person being named Dov, and the other two images, it's probably a mistaken picture of bears.)

What on earth is this about? I've studied the symbolism and significance of bears in Judaism very extensively, and I have never come across any connection to grapes. Google didn't help me, either. Does anyone have any insights?

In other news - I am currently planning my summer lecture tour in the US. I have availability for Shabbos July 21 in the NY region, and July 28 and August 11 in California. If you are interested in arranging a scholar-in-residence program, please write to me.

Published on April 18, 2012 07:03

April 17, 2012

"How Can You Cite Him?!" Plus, publishing woes

[image error]

Here is an interesting anonymous objection that I received recently, regarding my book "The Challenge Of Creation":

Although my book The Challenge Of Creation certainly has an ideological slant rather than being merely an academic history of views, it is also intended to provide a history of views. One of my goals in this book was to cite everything of relevance to Judaism and evolution, no matter who said it. At the same time, I try, within the confines of available space, to put the person in context, to explain what larger approach he represents and how he is viewed by others. I make no claim that every person cited is a religious authority to be relied upon.

Thus, for example, I quote non-Jewish atheists on various points - not to claim that they themselves reflect the overall approach of the book, or that they are not atheists, but only insofar as the specific point that they are making. I cite the approach of the Lubavitcher Rebbe that God created fossils, not that I agree with it (in fact I explain at length why I don't agree with it), but because it should be discussed. I briefly describe how leading rabbis in the Reform movement, such as Abraham Geiger and Isaac Mayer Wise, were hostile to evolution, and how this subsequently reversed itself in the Reform movement - not because I am Reform, but because I am documenting Jewish approaches to evolution. And I describe how certain 19th century religious Jews such as Rabbi Eliyahu Benamozegh, Naftali Levy and Yosef Yehudah Leib Sossnitz, accommodated evolution. But at the same time I noted that some of these figures were associated with the haskalah and that the overall attitude to evolution from the Orthodox Jewish community was hostile.

With regard to Rabbi Eliyahu Benamozegh specifically, I had never heard of his view about the Gospels. However, in my experience, it is often possible to find views amongst accepted Torah scholars that sound very strange to us - especially with rabbis from Italy.

While on the topic of "The Challenge of Creation," I should mention that it is currently out of print, and has been the subject of publishing woes beyond that of the overall disastrous situation these days with publishing in general and Jewish publishing in particular. My nine years of publishing and distributing with Targum/ Feldheim were wonderful, but came to an end with the ban on my books. Rabbi Gil Student rescued me with Yashar Books, but as a tiny Jewish publishing operation it was doomed and he had to close down. I then took up with another distributor, which was a very poor choice and worked out badly, and so now I have to republish "The Challenge Of Creation" yet again - this time distributing with Gefen Books. (There are a few very minor changes from the third edition.) It's ready to go to press, but I still have to raise about half the funds for publication. If you value the Rationalist Judaism enterprise, and are interested in sponsoring this project, please write to me.

Here is an interesting anonymous objection that I received recently, regarding my book "The Challenge Of Creation":

"You quote certain people in your books that I do not usually see quoted. What are your requirements for someone to be considered a Jewish authority? To be more specific, I am most bothered by your quotation from Elijah Benamozegh who (it is attested in Wikipedia at least) "even considered the Gospels to be a highly valuable Jewish Midrash, comparable to the Talmudic Aggadah". Does this not make him suspect regarding anything he says? Why should you pay attention to him at all?"The anonymous letter-writer is, I think, under two misconceptions - one regarding the nature of my book, and another regarding people such as Benamozegh.

Although my book The Challenge Of Creation certainly has an ideological slant rather than being merely an academic history of views, it is also intended to provide a history of views. One of my goals in this book was to cite everything of relevance to Judaism and evolution, no matter who said it. At the same time, I try, within the confines of available space, to put the person in context, to explain what larger approach he represents and how he is viewed by others. I make no claim that every person cited is a religious authority to be relied upon.

Thus, for example, I quote non-Jewish atheists on various points - not to claim that they themselves reflect the overall approach of the book, or that they are not atheists, but only insofar as the specific point that they are making. I cite the approach of the Lubavitcher Rebbe that God created fossils, not that I agree with it (in fact I explain at length why I don't agree with it), but because it should be discussed. I briefly describe how leading rabbis in the Reform movement, such as Abraham Geiger and Isaac Mayer Wise, were hostile to evolution, and how this subsequently reversed itself in the Reform movement - not because I am Reform, but because I am documenting Jewish approaches to evolution. And I describe how certain 19th century religious Jews such as Rabbi Eliyahu Benamozegh, Naftali Levy and Yosef Yehudah Leib Sossnitz, accommodated evolution. But at the same time I noted that some of these figures were associated with the haskalah and that the overall attitude to evolution from the Orthodox Jewish community was hostile.

With regard to Rabbi Eliyahu Benamozegh specifically, I had never heard of his view about the Gospels. However, in my experience, it is often possible to find views amongst accepted Torah scholars that sound very strange to us - especially with rabbis from Italy.

While on the topic of "The Challenge of Creation," I should mention that it is currently out of print, and has been the subject of publishing woes beyond that of the overall disastrous situation these days with publishing in general and Jewish publishing in particular. My nine years of publishing and distributing with Targum/ Feldheim were wonderful, but came to an end with the ban on my books. Rabbi Gil Student rescued me with Yashar Books, but as a tiny Jewish publishing operation it was doomed and he had to close down. I then took up with another distributor, which was a very poor choice and worked out badly, and so now I have to republish "The Challenge Of Creation" yet again - this time distributing with Gefen Books. (There are a few very minor changes from the third edition.) It's ready to go to press, but I still have to raise about half the funds for publication. If you value the Rationalist Judaism enterprise, and are interested in sponsoring this project, please write to me.

Published on April 17, 2012 08:44

April 15, 2012

The Challenge of Blogging

Writing this blog has been valuable and rewarding in all kinds of ways. But I'm feeling quite strained these days over how many projects I am involved in -- my PhD, my encyclopedia, various publishing tasks, and other exciting projects, the details of which I hope to reveal soon. So I think that I'm going to have to slow down the pace of posting to this blog. If you want to be notified when new posts appear, you can subscribe by email using the form on the right, or set up an RSS feed.

Meanwhile, here are three pictures that I took over Pesach:

An Arabian oryx (probably the Biblical re'em) in the Arava wilderness.

An Arabian oryx (probably the Biblical re'em) in the Arava wilderness.

My feet, being cleaned by "doctor fish."

My feet, being cleaned by "doctor fish."

An aerial view of Masada, which I took from a helicopter provided by Warren Buffett and piloted by Brigadier-General Ilan Hershkowitz.

An aerial view of Masada, which I took from a helicopter provided by Warren Buffett and piloted by Brigadier-General Ilan Hershkowitz.

Meanwhile, here are three pictures that I took over Pesach:

An Arabian oryx (probably the Biblical re'em) in the Arava wilderness.

An Arabian oryx (probably the Biblical re'em) in the Arava wilderness.  My feet, being cleaned by "doctor fish."

My feet, being cleaned by "doctor fish."  An aerial view of Masada, which I took from a helicopter provided by Warren Buffett and piloted by Brigadier-General Ilan Hershkowitz.

An aerial view of Masada, which I took from a helicopter provided by Warren Buffett and piloted by Brigadier-General Ilan Hershkowitz.

Published on April 15, 2012 23:36

April 4, 2012

Why On Earth Would One Eat A Kezayis?

The reaction of many people to my conclusions about the kezayis is one of shock, followed by the question: "So do you yourself really eat such a small portion of matzah and maror?"

This is a very strange question. It also sheds light on problems caused by the evolution of the large kezayis-shiur.

Why on earth would I, or anyone, only eat an olive-sized portion of matzah and maror? The mitzvah comes late at night, after a really long day, when I haven't eaten for hours. Any normal person will eat much more than an olive-sized portion!

The kezayis is a minimum . The halachah says that eating anything less than a kezayis is just not called an act of eating. But any ordinary act of eating is obviously more than the bare minimum!

Does anyone build a sukkah ten tefachim high?!

So why do people wonder if people like me will be eating an olive-sized portion? Probably because the evolution of the large kezayis, along with the change from traditional matzah to Ashkenazi matzah (a.k.a. concrete) and from traditional maror (wild lettuce, sowthistle, etc.) to horseradish, has made eating a kezayis such a tricky and stomach-challenging ordeal that this is all that people aim for. Kezayis becomes not the minimum, less than which is simply not an act of eating, but rather the challenge, the goal. And people become so focused on eating the right quantity that this becomes the main thing that they think about!

But when you eat traditional matzah, and traditional maror (which was the normal hors d'oeuvre in antiquity), and a kezayis is a kezayis, why on earth would anyone only eat a kezayis?

This is a very strange question. It also sheds light on problems caused by the evolution of the large kezayis-shiur.

Why on earth would I, or anyone, only eat an olive-sized portion of matzah and maror? The mitzvah comes late at night, after a really long day, when I haven't eaten for hours. Any normal person will eat much more than an olive-sized portion!

The kezayis is a minimum . The halachah says that eating anything less than a kezayis is just not called an act of eating. But any ordinary act of eating is obviously more than the bare minimum!

Does anyone build a sukkah ten tefachim high?!

So why do people wonder if people like me will be eating an olive-sized portion? Probably because the evolution of the large kezayis, along with the change from traditional matzah to Ashkenazi matzah (a.k.a. concrete) and from traditional maror (wild lettuce, sowthistle, etc.) to horseradish, has made eating a kezayis such a tricky and stomach-challenging ordeal that this is all that people aim for. Kezayis becomes not the minimum, less than which is simply not an act of eating, but rather the challenge, the goal. And people become so focused on eating the right quantity that this becomes the main thing that they think about!

But when you eat traditional matzah, and traditional maror (which was the normal hors d'oeuvre in antiquity), and a kezayis is a kezayis, why on earth would anyone only eat a kezayis?

Published on April 04, 2012 11:43

April 2, 2012

Matzah/ Maror Chart for Rationalists

I am pleased to make available a free chart depicting the minimum quantities required of matzah and of maror, from a rationalist perspective. You can download it at this link. Share and enjoy!

Published on April 02, 2012 12:23

April 1, 2012

Why Do We Eat Matzah? Plus, more on the bear

Why do we eat matzah on Pesach? It's a very basic, simple and obvious question, so it should have a very basic, simple and obvious answer, right?

The usual answer is that the Torah commands us to eat matzah on Pesach in commemoration of the Bnei Yisrael rushing out of Egypt so quickly that their dough did not have time to rise. But why would this make it so very important? And is that really the straightforward understanding of what the Torah says? It might come from combining two pesukim which are not necessarily to be combined.

In Devarim 16:3, we have the following passuk:

Of course, one could say that God commanded it knowing what would happen. But then why is there no mention of that? Furthermore, way back in Bereishis 19:3, Lot serves matzos to the angels. Rashi says it was Pesach, and a very non-rationalist person in a book entitled Seasons of Life claims that "the observance of Pesach is based on the spiritual powers in force at that time of year," and "matzah is representative of certain metaphysical forces in effect at that time." But the idea of Lot observing Pesach and serving matzah to his guests is reminiscent of a certain video involving bear-dogs. Is there a more rationalist explanation?

The answer to all these questions is quite simple. And it provides an example of academic scholarship enhancing the Torah rather than challenging it.

Put very simple, the answer is this: Bread, of the chametz variety, is an Egyptian invention.

In Canaan, the lifestyle was a nomadic society of shepherds. The bread that they ate was matzah - of course, not the hard Ashkenazi crackers, but the original, somewhat softer, pita-like matzah. (Which is why Lot served it to his guests.)

Egypt, on the other hand, was a land of farming, which despised the nomadic lifestyle. As Yosef advises his brothers to tell Pharaoh: "You should answer, 'Your servants have tended livestock from our boyhood on, just as our fathers did.' Then you will be allowed to settle in the region of Goshen, for all shepherds are detestable to the Egyptians." The Egyptians had mastered the art of leavening bread, which was unknown to those from Canaan (which may be why Potiphar entrusted everything to Yosef except baking bread - see Bereishis 43:32). Baking leavened bread was of tremendous importance in Egypt - that is why there was a sar ha-ofim, a royal baker. There is a list presented by Rameses III which has an amazing variety of breads. But shepherds didn't and don't eat such things - they roam around free, without the burden of heavy ovens and without waiting around for bread to rise.

And so the prohibition against eating leavened bread on Pesach is so very important because it is a way of demonstrating that we left Egypt, the land known for its leavened bread, and we became free, like nomads, to travel to the Promised Land.

For more on all this, see this article from Neot Kedumim, and also this article and this one.

* * *

And now for something completely different. Following my post on Crowdsourcing the Bear, which proved very effective, I have one final bear-related question which has so far stumped everyone that I've asked. The Gemara (Avodah Zarah 2b) speaks about the future judgment of the nations, which takes place in order of their importance. First is Rome; second is Persia:

But surely the whole proof for the bear being number two is that it appears after the lion in Daniel's vision. If the lion is not more important than the bear, how does the Gemara's proof work? And if the Gemara is indeed proving that Persia is second from it being second to the lion in Daniel, then why isn't Babylon before Persia?

Many thanks for any light that people can shed on this!

The usual answer is that the Torah commands us to eat matzah on Pesach in commemoration of the Bnei Yisrael rushing out of Egypt so quickly that their dough did not have time to rise. But why would this make it so very important? And is that really the straightforward understanding of what the Torah says? It might come from combining two pesukim which are not necessarily to be combined.

In Devarim 16:3, we have the following passuk:

You shall eat no leavened bread with it; seven days you shall eat matzos, the bread of affliction; for in haste (chipazon) did you come forth out of the land of Egypt; that you may remember the day when you came forth out of the land of Egypt all the days of your life.The usual assumption is that the mention of "haste" is a reference to the pessukim in Shemos 12:33-34 talking about how the Bnei Yisrael rushed out of Egypt without time for their dough to rise:

"And the Egyptians were urging upon the people, to send them out of the land in haste; for they said: 'We are all dead men.' And the people took their dough before it was leavened, their kneading-troughs being bound up in their clothes upon their shoulders."But the word chipazon, which appears later with regard to matzos, does not appear in these pessukim. Instead, it appears earlier, in Shemos 12:11, before the end of the plagues, with regard to the korban Pesach:

"And thus shall you eat it: with your loins girded, your shoes on your feet, and your staff in your hand; and you shall eat it in haste--it is a Passover to God."A few verses later, we have the commandment that on Pesach we must eat matzah and there may be no chametz in our houses. But the tenth plague, and the Bnei Yisrael rushing out, hasn't happened yet!

Of course, one could say that God commanded it knowing what would happen. But then why is there no mention of that? Furthermore, way back in Bereishis 19:3, Lot serves matzos to the angels. Rashi says it was Pesach, and a very non-rationalist person in a book entitled Seasons of Life claims that "the observance of Pesach is based on the spiritual powers in force at that time of year," and "matzah is representative of certain metaphysical forces in effect at that time." But the idea of Lot observing Pesach and serving matzah to his guests is reminiscent of a certain video involving bear-dogs. Is there a more rationalist explanation?

The answer to all these questions is quite simple. And it provides an example of academic scholarship enhancing the Torah rather than challenging it.

Put very simple, the answer is this: Bread, of the chametz variety, is an Egyptian invention.

In Canaan, the lifestyle was a nomadic society of shepherds. The bread that they ate was matzah - of course, not the hard Ashkenazi crackers, but the original, somewhat softer, pita-like matzah. (Which is why Lot served it to his guests.)

Egypt, on the other hand, was a land of farming, which despised the nomadic lifestyle. As Yosef advises his brothers to tell Pharaoh: "You should answer, 'Your servants have tended livestock from our boyhood on, just as our fathers did.' Then you will be allowed to settle in the region of Goshen, for all shepherds are detestable to the Egyptians." The Egyptians had mastered the art of leavening bread, which was unknown to those from Canaan (which may be why Potiphar entrusted everything to Yosef except baking bread - see Bereishis 43:32). Baking leavened bread was of tremendous importance in Egypt - that is why there was a sar ha-ofim, a royal baker. There is a list presented by Rameses III which has an amazing variety of breads. But shepherds didn't and don't eat such things - they roam around free, without the burden of heavy ovens and without waiting around for bread to rise.

And so the prohibition against eating leavened bread on Pesach is so very important because it is a way of demonstrating that we left Egypt, the land known for its leavened bread, and we became free, like nomads, to travel to the Promised Land.

For more on all this, see this article from Neot Kedumim, and also this article and this one.

* * *

And now for something completely different. Following my post on Crowdsourcing the Bear, which proved very effective, I have one final bear-related question which has so far stumped everyone that I've asked. The Gemara (Avodah Zarah 2b) speaks about the future judgment of the nations, which takes place in order of their importance. First is Rome; second is Persia:

"The kingdom of Rome leaves, and then the kingdom of Persia enters. Why? Because it follows Rome in prestige. How do we know this? As it is written, "And behold another beast, a second, like a bear" (Daniel 7), and Rav Yosef taught that this refers to the Persians…"Tosafos raises the question that if we are judging the prominence of nations via their symbolism with animals, then surely the lion, as king of beasts, is more important than the bear. Since the lion represents Babylon, then surely Babylon should be judged after Rome, before Persia! Tosafos answers that even though the lion is king of beasts, the bear is more powerful and more devious.

But surely the whole proof for the bear being number two is that it appears after the lion in Daniel's vision. If the lion is not more important than the bear, how does the Gemara's proof work? And if the Gemara is indeed proving that Persia is second from it being second to the lion in Daniel, then why isn't Babylon before Persia?

Many thanks for any light that people can shed on this!

Published on April 01, 2012 07:05

March 29, 2012

The All-Time Most Popular Post

The most popular post on this blog of all time is that featuring my monograph on The Evolution Of The Olive, with over 3600 pageviews, and many more who received the monograph via e-mail. I assume that the reasons for its popularity are that everyone encounters this topic at least once a year, and many people are confounded by the strange and common practice of eating huge amounts as a "kezayis." (See too my follow-up post, The Riddle of the Giant Kezayis Defense.)

I noticed that the Jewish Press has a new column on this by Rabbi David Bar-Hayim, which was also picked up by Vos Iz Neias (on which the comments always provide fascinating material for social anthropology). While I agree with Rabbi Bar-Hayim's analysis of the halachic history of the kezayis, I cannot agree with his positions regarding how halachah must always confirm to reality as we understand it. Judaism attributes great significance to tradition, and furthermore I'm not sure that he appreciates just how much of a Pandora's box his approach opens.

I noticed that the Jewish Press has a new column on this by Rabbi David Bar-Hayim, which was also picked up by Vos Iz Neias (on which the comments always provide fascinating material for social anthropology). While I agree with Rabbi Bar-Hayim's analysis of the halachic history of the kezayis, I cannot agree with his positions regarding how halachah must always confirm to reality as we understand it. Judaism attributes great significance to tradition, and furthermore I'm not sure that he appreciates just how much of a Pandora's box his approach opens.

Published on March 29, 2012 09:27

March 27, 2012

Rav Dessler: In or Out?

In the first part of my book The Challenge Of Creation, which evolved from my earlier book The Science Of Torah, I develop the idea of how the system of natural law is immensely significant and valuable from a rationalist Jewish perspective. One of the authorities that I invoke in support of this approach is Rav Dessler:

But does Rav Dessler have a place in a presentation of the rationalist approach? There is a newly published book, Modern Orthodox Judaism , by the late Rabbi Dr. Menachem-Martin Gordon, whose excellent studies of mezuzah and netilas yadayim can be found linked on the side of this website. In a footnote on p. 31, he describes Rav Dessler's "anti-science position" as follows:

Is his understanding of Rav Dessler's position correct? And if so, should I therefore remove my discussion of Rav Dessler's position from my book? This is immediately pertinent, because I am currently preparing a new edition of The Challenge Of Creation. Due to unfortunate problems with my previous distributor, I have to switch to a new distributor and re-do the book from scratch - sponsorship opportunities for the book are available and assistance would be welcomed!

Rabbi Dessler explains that there are different levels of appreciation of God's control of the world. The lowest level, on which many of us find ourselves, is that we profess to recognize the truth of it, but do not really do so at heart. The litmus test of this is whether we live our lives any differently. We might say, "God sustains us," but we wouldn't dream of actually entrusting Him to handle any of it. Because the person in this position does not really recognize God's control of the world, he will be treated strictly according to natural law, with no suspensions of it ever made for him. (It is in comparison to such a person that Rav Yosef praised the man who experienced the miracle of being able to nurse his child.)

A higher level is to recognize that God can do with nature as He pleases. A person at this level, however, might be distracted from this viewpoint if he never sees providence overriding the ordinary course of nature. He needs occasional proof that God controls his destiny. Such was the level of the man who miraculously nursed his child, which was why Abayey commented that it didn't place him in the best light. Another reason why this is not the highest level is that it still perceives nature as a tool—an extension of God, something one level removed from Him. This also implies a deficiency in God's abilities, as one only uses a tool if one can't do the job oneself.

The highest level is to see nature not as a tool of God, but as a representation of God Himself. It is not that matters are controlled by nature, which in turn is controlled by laws, which in turn are powered by God—God is present at every stage of the process. This is not, Heaven forbid, to imply a position of pantheism, or Spinoza's position that God is nothing more than a synonym for the laws of nature. It is not that God is really nature; rather, nature is really a concealed representation of God. He is not using tools.

(Adapted from Michtav Me-Eliyahu vol. I pp. 197-203)

But does Rav Dessler have a place in a presentation of the rationalist approach? There is a newly published book, Modern Orthodox Judaism , by the late Rabbi Dr. Menachem-Martin Gordon, whose excellent studies of mezuzah and netilas yadayim can be found linked on the side of this website. In a footnote on p. 31, he describes Rav Dessler's "anti-science position" as follows:

Rav Dessler's book, Mikhtav me-Eliyahu, whose impact on the yeshiva world in recent years has been enormous, represents a radical departure from the Talmudic position (Hullin 105a, Niddah 70b), as well as the medieval philosophic tradition (Rambam, Moreh Nevuchim, 3:17), in its denial of the reality of natural law and the cause—and—effect nexus of human initiative (Mikhtav, I, pp. 177-206). For Rav Dessler, the study of the sciences - even medicine, for that matter - is pointless, since the exclusive determinate of human welfare is the providential hand of God responding to religious virtue. Similarly, serious financial initiative is unnecessary. The diagnostic skill of the physician (Mikhtav, III, p. 172), the financier's business acumen (Mikhtav, I, p. 188), ostensibly critical factors in the effectiveness of their efforts, are only illusory causes, argues Rav Dessler. Admittedly, he concedes, one must "go through the motions" of practical activity (the notion of hishtadlut, Mikhtav, I, pp. 187-88) - visiting a physician, making a phone call for financial support - but such is necessary only as a "cover" for the direct Divine conduct of human affairs, which men of faith are challenged to discern. Recognizing the immediacy of the Divine hand behind the facade of human initiative is the ultimate test of faith. One should be engaged in practical effort only for the purpose, paradoxically, of discovering its pointlessness! Therefore, asserts Rav Dessler, to the degree that a man has already proved his spiritual mettle, his acknowledgment of Divine control, could the extensiveness of his "cover" be reduced. Or, alternatively, to the degree that a man is not yet sufficiently spiritually perceptive - wherefore pragmatic initiative might "blind" him to Divine control - should he limit such recourse. Accordingly, b'nei yeshiva are implicitly discouraged from any serious financial initiative - or involvement across the board in any area of resourceful effort, be it technological, political, etc. - since the circumstances of life are, in reality, a spontaneous Divine miracle. (Note Rav Dessler's necessarily strained interpretation of Hullin, ad loc. and Niddah, ad loc., where one is advised by Harzal to survey one's property with regularity, and to "abound in business." in the pursuit of wealth! — Mikhtav, I, pp. 200-01).

Rav Dessler's position cannot draw support from the doctrine of Ramban, although he

assumes such an identification (ibid., III, pp. 170-73). While Ramban defines the ultimate providential relationship of God to Israel as one of ongoing miracle, he essentially never denies the reality of natural law. Israel, Ramban argues, through its fulfillment of mitzvot, is ideally able to transcend nature and engage God in the special faith—miracle association. In actuality, Ramban in fact concedes, such a relationship with the Divine does not generally prevail today, so that one must live, as a rule, in response to natural law. Thus he legitimates medical practice - he himself, after all, was a physician - not as a "cover" for some outright miracle deceptively operative behind the scenes, as Rav Dessler would have it, but as a genuine recourse to an efficacious discipline. (See Ramban, Commentmy, Lev. 26:11; Torat ha-Adam, in Kitvei Ramban, II, pp. 42-43.) For Rav Dessler, the "natural agency" of medical treatment (III, p. 172), which, admittedly, those of low—faith level must necessarily pursue, is not an effect of natural law as Ramban recognizes it, but, once again, a deceptive expression at every moment of the spontaneous Divine will (see his own reference [ad loc., p. 173] to his basic definition of "nature" in I, pp. 177-206).

Rambam, of course - in contrast even with Ramban - rejects as patently absurd the notion that faith healing, a disregard for nature, could ever prevail as the will of God (see his Commentary to Mishnah, Pesachim 4:10).

Is his understanding of Rav Dessler's position correct? And if so, should I therefore remove my discussion of Rav Dessler's position from my book? This is immediately pertinent, because I am currently preparing a new edition of The Challenge Of Creation. Due to unfortunate problems with my previous distributor, I have to switch to a new distributor and re-do the book from scratch - sponsorship opportunities for the book are available and assistance would be welcomed!

Published on March 27, 2012 11:18

March 22, 2012

Crowdsourcing the Bear

Eleven years ago, I began the biggest project of my writing career: The Torah Encyclopedia of the Animal Kingdom (click on this link for more info and a free sample chapter on leopards). Instead of working on the (projected) four volumes in order, I worked on which creature grabbed my interest at that time and sparked my creativity. For example, when I found a rarely-seen Mediterranean mole-rat, I started working on that entry; when I attended a halachic dissection of a stork, I worked on that entry. As a result, although I have written well over 100,000 words spanning many entries, no single volume is complete.

Eventually, I decided to focus on finishing the first volume, on chayos (wild animals), which is about 80% complete. Then I was distracted by the ban on my books and my academic career. I'm now trying to finish it off, but due to my doctoral dissertation and other projects, I can't give it my full attention. In addition, with each entry, there are sometimes a few sources that present difficulties.

And then I had the idea of crowdsourcing it. Here on this website I am blessed with an audience of over a thousand readers, many of whom are greatly learned. And so occasionally, I would like to present some sources and invite your input. Today's topic is bears, and following are two sources from Chazal that are giving me difficulties.

Question #1: Why did Rav and Shmuel say that there was any miracle at all? Couldn't there just have been a forest and bears already there? Maharsha suggests that if so, the children would have been afraid to go there, and also that the deaths of the children would not have been attributable to Elisha's curse. Both those answers seem rather difficult.

Question #2: How would the rationalist Rishonim have understood this Gemara? Creation of bears and trees ex nihilo would surely be problematic for them.

Question #3: Kids can be cruel, but doesn't mass slaughter of them seem to be rather a disproportionate response?

Question #4: Is the Modern Hebrew expression "Lo dubim, lo ya'ar" based on a misunderstanding of the Gemara? (See, for example, here)

Next source: When Avraham attempted to prevent God from destroying Sodom, he argued that righteous people would also end up being killed if destruction was unleashed upon the city. The Midrash compares such unwanted results to a bear whose anger does not find a target:

Thank you in advance for your suggestions!

Eventually, I decided to focus on finishing the first volume, on chayos (wild animals), which is about 80% complete. Then I was distracted by the ban on my books and my academic career. I'm now trying to finish it off, but due to my doctoral dissertation and other projects, I can't give it my full attention. In addition, with each entry, there are sometimes a few sources that present difficulties.

And then I had the idea of crowdsourcing it. Here on this website I am blessed with an audience of over a thousand readers, many of whom are greatly learned. And so occasionally, I would like to present some sources and invite your input. Today's topic is bears, and following are two sources from Chazal that are giving me difficulties.

"...And two bears came out of the forest and tore up forty-two of the children" (Kings II 2:24, referring to the children that taunted Elisha). There was a dispute between Rav and Shmuel; one said that this was a miracle, and the other said that it was a miracle within a miracle. The one who said that it was a miracle is of the opinion that there was already a forest, but there were not any bears. The one who said that it was a miracle within a miracle is of the opinion that there was previously neither forest nor bears. But let there be bears without a forest? Because they would be afraid. (Talmud, Sotah 46b-47a)

Question #1: Why did Rav and Shmuel say that there was any miracle at all? Couldn't there just have been a forest and bears already there? Maharsha suggests that if so, the children would have been afraid to go there, and also that the deaths of the children would not have been attributable to Elisha's curse. Both those answers seem rather difficult.

Question #2: How would the rationalist Rishonim have understood this Gemara? Creation of bears and trees ex nihilo would surely be problematic for them.

Question #3: Kids can be cruel, but doesn't mass slaughter of them seem to be rather a disproportionate response?

Question #4: Is the Modern Hebrew expression "Lo dubim, lo ya'ar" based on a misunderstanding of the Gemara? (See, for example, here)

Next source: When Avraham attempted to prevent God from destroying Sodom, he argued that righteous people would also end up being killed if destruction was unleashed upon the city. The Midrash compares such unwanted results to a bear whose anger does not find a target:

"And Abraham drew near…" (Genesis 18:23) Rabbi Levi said: [It is comparable] to a bear that was raging against an animal, and could not find the animal to rage against, and raged against her children. (Midrash Bereishis Rabbah 49:8)Bears are not known to ever do such a thing; their instinct to protect their young is incredibly strong. (I double-checked with the world's greatest expert on bear aggression.) I'm not averse to simply saying that it is zoologically inaccurate, but obviously it would be great to avoid having to do so - especially because this book is directed towards a broader audience than my other books. Matnos Kehunah says that the correct version is בבהמות not בבניה, which would certainly solve the problem, but is there any manuscript or other evidence for this?

Thank you in advance for your suggestions!

Published on March 22, 2012 06:57