Natan Slifkin's Blog, page 182

June 3, 2012

Agudah Acknowledges Dropping The Ball On Abuse, Claims Near-Perfection

Mishpachah magazine just featured an interview with Chaim Dovid Zwiebel, Executive Vice-President of Agudath Israel of America. I've met him, and he's a very nice, very intelligent person. But his comments are astonishing.

"Look, I don’t write off the bloggers as leitzanim and reshaim, because they will be judged, as we all will, after 120 years for their motivations and techniques. I'm not a condemner, by nature."

"I do believe that among them there are people who are deeply pained about certain issues and feel that this is the way they can express their pain. I will even go a step further and say that through the pressure they’ve created, communal issues that needed to be confronted were moved to the front burner and taken seriously. A case in point is abuse and molestation issues. The question is, if the fact that they've created some degree of change is worth the cost. At the very least, it’s rechilus, lashon hara, and bittul zman. That’s a high price to pay."

"Then there is the damage wrought to the hierarchy of Klal Yisrael. We've always been a talmid chacham-centered nation, and it’s dangerous to ruin the fabric of Klal Yisrael by denigrating the ideal of daas Torah and by allowing personal attacks on gedolei Torah.”

Reb Chaim Dovid believes that the process of decision-making through the Moetzes is as close to perfect as can be. “It’s a homogeneous group of the most intelligent, empathetic individuals — all great talmidei chachamim — and they grasp all aspects of an issue right away.”

Where do I begin?

Let's start with the positive. Zwiebel acknowledges that the charedi world was not taking the issue of abuse and molestation seriously. That's worthy of credit, even though it's blindingly obvious. Given that there are other Agudah spokesmen who only weigh in on this topic to claim that there is a baseless witch-hunt in this area, it's refreshing to see Zwiebel admit that the charedi leadership dropped the ball on this issue.

It's also good to see Zwiebel acknowledge that a large part of the credit for the charedi world beginning to take these issues seriously is due to bloggers. That can't be an easy admission to make; Failed Messiah and UOJ write many things that are distasteful, to say the least. But it is clearly due to them that the charedi world started to address abuse, and so it is good that Zwiebel gives credit where credit is due.

On the other hand, given these admissions, Zwiebel's other comments are all the more incomprehensible.

Zwiebel admits that the Charedi world did not take these issues seriously - that the abuse of hundreds, probably thousands, of children continued, while molesters were protected and parents were told to shut up. But he wonders if stopping that evil is worth rechilus, lashon hara, and - I'm almost gagging at typing this - bittul zman! By what possible measure might it not be worth it?!

Then we have to think about whether there really are crimes of rechilus, lashon hara, and bittul zman. Sure, there may be some accusations that are false. But, as Rabbi Yaakov Horowitz notes, the majority of discussions about abuse are about cases which are true. And it's talking about them on the Internet which has gotten them dealt with - nothing else worked! So where is the excess of rechilus, lashon hara, and bittul zman?

Then we come to Zwiebel's protest that the blogosphere has denigrated Daas Torah and the honor of the Gedolim. Well, yes, it has. But considering that Agudas Yisrael's version of Daas Torah is a recent invention, I can't see that the exposure of its failings is such a terrible thing. And considering that the Gedolim are the leaders, and are thus responsible for dropping the ball on the issue of abuse, surely any loss of respect is their own responsibility. I haven't seen anyone denigrating and losing respect for rabbis such as Rabbi Yaakov Horowitz, Rabbi Yosef Blau, Rabbi Chaim Soloveitchik and Rabbi Yitzchok Adlerstein. Respect is given when it is justly earned.

Next we have Mishpachah describing Zwiebel as believing that "the process of decision-making through the Moetzes is as close to perfect as can be." Given that he's just admitted that, unlike the majority of society, the Gedolim did not know how to deal with the issue of child abuse (i.e. they did not know that YES IT REALLY HAPPENS, YES IT'S REALLY TERRIBLE, NO YOU CAN'T DEAL WITH IT ON YOUR OWN, GO TO THE AUTHORITIES), how on earth does he believe that their decisions are "as close to perfect as can be"?

Look back at the fiasco of Daas Torah over the last decade. Banning Lipa's Big Event at Madison Square Gardens, at a cost of hundreds of thousands of dollars, due to it being irredeemably wrong, then permitting it a year later (where Rav Shmuel Kamenetzky publicly admitted that the Gedolim erred). Issuing various bans based on information from askanim with a deserved reputation for incitement and devious behavior, in some cases an actual criminal record for fraud! Giving great honor and power in geirus to a known manipulator and scumbag, and failing to condemn him when his even worse crimes are exposed on the Internet. Protesting the innocence of the monster Elior Chen, and defending this on the grounds that other rabbis say he's innocent. Announcing to a crowd of 40,000 people at CitiField, who have been informed that Daas Torah in such a context is binding on all Klal Yisrael, that kids from homes with Internet must be expelled from yeshivos - then promptly retracting it the next week. Heck, there are still rabbis who covered up for molestors being honored as Gedolim! Even charedi apologist Jonathan Rosenblum writes subversive columns about the problems in the Daas Torah process, though he attributes all the blame to askanim. This is a decision-making process that every normal person can see is deeply flawed - and Zwiebel claims that it's "as close to perfect as can be"?

And what reason does Zwiebel give for believing this? That the Gedolim are talmidei chachamim, intelligent and empathetic. I am sure that they are; but these are not sufficient requirements for good leadership. It's troubling that Zwiebel sees a positive aspect in their being homogenous; that is, of course, a negative. Note that Chazal say that if a Sanhedrin reach a verdict unanimously, it is rejected! (There are a number of other halachos in the Gemara regarding the process of rabbinic judgment that are negated in the contemporary Daas Torah process. With all the talk about the greatness of Chazal, why are they not followed in this area?)

Good leadership requires people who are relatively young and independent, not elderly and relying on handlers. It requires people who are in touch with the community, not living in the ivory towers of the yeshivah world. Leadership in the area of abuse requires people who understand the problems, respect the expertise of people in the mental health profession, and respect civil law; not people who are too naive to believe the "tawdry tales," do not respect the expertise of people in the mental health profession, and think that the authorities are the goyishe enemy. Good leadership requires a system of checks and balances, not cronyism and the suppression of criticism. And most of all, as Rav Aharon Lichtenstein explains so well, good leadership requires wisdom.

Zwiebel, representing Agudath Israel, has always insisted that someone with suspicions of child abuse may not go directly to the authorities without consulting a suitably-qualified rabbi first. Recently, he admitted that Agudath Israel will not be providing a list of such allegedly suitably-qualified rabbis (for the simple reason that any rabbi that Agudah names will face prison if he does not report the cases that come to his attention). And Zwiebel agrees here that many rabbis have not dealt with such cases properly. So he knows that the system is badly broken, but insists that it must continue!

Sometimes, observing the system of rabbinic authority in the contemporary Charedi world is like watching a comedy. Except that it isn't funny, because the consequences are so tragic.

June 1, 2012

Rabbinic Responses to the Transit of Venus

GUEST POSTRabbinic Responses to The Transit of Venus

Jeremy Brown

Jeremy Brown lives outside of Washington DC. He is the author of New Heavens and a New Earth: The Jewish Reception of Copernican Thought, to be published later this year by Oxford University Press.

It’s hard not to have noticed that a remarkable celestial event will occur this Tuesday. The blogs have been discussing it, and new books have been published to commemorate the event. The event if the transit of Venus, and if the weather cooperates and the clouds stay away, you will be able to witness an event that will not occur again for another one hundred and five years. You’ll need the right equipment too, but that need not cost more than a few dollars.[1] With it, you will be able to see the planet Venus pass in front of the sun. Seen as a small black dot, it will make its way across the face of the sun over a period of several hours. The exact length of time depends on where you are located; in New York City the transit of Venus will be visible at 6.04pm, while in Jerusalem it can be seen at 7.37am.[2]

The transit of Venus was of huge scientific importance in the nineteenth century, because by observing it from various locations and using some clever trigonometry, it allowed astronomers estimate the distance from the Earth to the sun more accurately than had ever been done before.[3] Knowing this distance would allow the distance of other planets from the Earth to be calculated, which would then give the answer to one of the most important unanswered astronomical questions of the time: Just how big is the solar system?

The transit of Venus occurs twice in eight years, followed by a gap of 105.5 or 121.5 years[4]. The first time it could be viewed was in 1639, but that transit was witnessed by only two observers. By the time of the paired transits of 1761 and 1769, scientific instruments were accurate enough to provide the data needed for the all-important calculations. So in 1760 and again in 1768 the major European nations including Britain, France, Spain and Russia, sent teams across the globe to measure the transit times of Venus. Perhaps the most famous expedition was that led by Captain James Cook, who sailed from London to Tahiti and made a series of accurate measurements that allowed the all-important calculations to be made.

Much less well known are the Jewish responses to all this. Although Jews had been taking a keen interest in astronomy since Talmudic times, the Copernican revolution had challenged the notions of the centrality and immobility of the Earth. However the arguments for the truth of heliocentric system of Copernicus were still largely theoretical (and would remain so until the discovery of stellar parallax in 1836 and the demonstration of Foucault’s pendulum in 1853). The transit of Venus offered some indirect support for the Copernican model, in that it would allow an accurate measurement of the size of the solar system.

SEFER HABERIT, 1798

The first Hebrew book to discuss the transit of Venus was Sefer Haberit, The Book of the Covenant, first published in 1797 in Brno. The author was Pinhas Hurwitz, a self-educated Jew from Vilna. Sefer Haberit was divided in two parts; the first, consisting of some two hundred and fifty pages is a scientific encyclopedia, addressing what Hurwitz called human wisdom (hokhmat adam) and focuses on the material world. The second part, shorter than the first at only one hundred and thirty pages, is an analysis of divine wisdom (hokhmat elohim), and focuses on spiritual matters.[5] Sefer Haberit was an encyclopedia, and contained information on astronomy, geography, physics, and embryology. It described all manner of scientific discoveries, from the barometer to the lightening rod, and gave its readers up to date information on the recent discovery of the planet Uranus, and the (not so recent) discovery of America. Sefer Haberit was also incredibly popular; it has been reprinted some thirty times, was translated into Yiddish and Ladino, and remains available today.

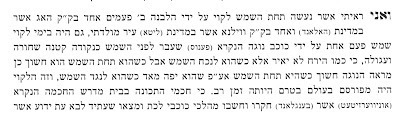

In a section on solar and lunar eclipses, Hurwitz recalled the transit of Venus in 1769. He described how Cook’s expedition had almost been in vain when some of their scientific instruments were stolen the night before the transit, and how, thanks to the team’s valiant efforts, the stolen instruments were returned. Here is the original text:

This was a fairly accurate recounting of the facts, although in actuality the theft occurred a month before the transit. (Despite guards that were placed to patrol the camp, a local had managed to slip in and steal a vital piece of equipment.) What is of interest here is that Hurwitz did not inform his readers of the real reason that the transit was to be observed. There is no mention of the way in which the transit of Venus could be used to determine the size of the solar system or the distance from the sun to the Earth, which were of course the real reasons for all the time and effort being spent in observing it. Why did Hurwitz leave all this out, and suggest instead that the reason for sending Captain Cook all the way from London to Tahiti was to see if the predictions for the time of the transit were accurate?

The answer lies in the fact that Hurwitz was somewhat conflicted about his belief in the model suggested by Copernicus in which the Earth and all the planets revolve around a stationary sun. In some places in Sefer Haberit he was supportive of the Copernican model. For example, he noted that Copernicus provided

proofs and supports for his position [that] are clearly written in his book. He was remarkably successful in this matter, for today virtually all of the wise men of the world agree that this opinion is in fact correct. His model is used to understand all matters of astronomy, the phases of the moon and the movement of the stars. Any calculation involving their appearance can be understood far more clearly and simply than if we accept the earlier model…[6]Despite this approval, Hurwitz ultimately sided with the Tychonic model in which all the planets except the Earth revolve around the sun, while the sun orbits a stationary Earth, dragging the planets along with it. He did this for a number of scientific and theological reasons, including a belief that the Earth was the crowning glory of creation. “All of the planets were only created for the sake of this Earth, and everything was created for the sake of mankind on the Earth...even if the purpose of these other heavenly creations is not always clear to us.”[7] Since the Earth was the reason for creation, it was only fitting that it lay at the center of the universe. Although he ultimately rejected the Copernican model, Hurwitz wrote that that a Jew may believe in it without fear of heresy:

any person of Jewish faith who strongly believes in this [heliocentric] theory should not be considered to be weak in his belief in the written Torah or the Oral Law, and certainly such a person should never be branded or suspected of heresy. Indeed he could be considered a zadik among Israel, so long as his other beliefs and practices follow both the written Torah and the Oral Law, and he fears God.[8]However, Hurwitz felt that because there were a number of biblical verses that described the Earth as being stationary, that must in fact be the way it was in reality. One of the experimental supports that Hurwitz gave was the evidence from a stone dropped from the top of a tower. If the Earth was in motion the stone should, it was argued, fall some distance west of the tower, since during the time the stone was in free-fall, the Earth was moving from west to east. Hurwitz claimed that when a stone is dropped from a tall mast on a moving ship, it fell a small distance from the base of the mast. The fact that this did not occur on land was conclusive evidence that the Earth was in fact stationary.[9]

Hurwitz described the goal of Cook’s expedition to Tahiti as testing the predictions of the timing of the transit, when in fact its mission was far more important than that. But since Hurwitz ultimately rejected the Copernican model he likely chose not to discuss the real reason for Cook’s expedition, namely to provide data that would allow the size of the Copernican solar system to be calculated. Instead, Hurwitz described the mission as one to verify the times of the predicted transit, as a sort of test of the ability of astronomers to predict these kinds of events. Although he did not reveal the real goals of the expedition, he noted that is was a great success, and that transit of Venus occurred precisely the times predicted, or as he put it “כתבו אשר מכל דבר נפל לא.”

KOCHAVA DESHAVIT, 1835

In 1835 a young Jew from eastern Poland called Hayyim Slonimski published a book called Kokhava Deshavit, (The Comet), to coincide with the return of Halley’s comet. Slonimski was a remarkable figure in the history of Jewish science. He was traditionally educated in yeshiva, yet earned recognition from the Russian government and a prize from the Imperial Academy of Sciences in St Petersburg for his work developing a calculating machine. Slonimski founded the famous Hebrew language weekly Hazefirah (Dawn), which focused on scientific and political issues, and he wrote several books on astronomy and mathematics. Unlike Hurwtiz, Slonimski fully embraced the Copernican model, and had no problem with the biblical verses that suggested the Earth did not move. They were not to be interpreted literally, and scientific facts could never be in conflict with the truths of the Torah, “for both are true and given by the true God.”

Specifically, if we believe that the Earth has a daily revolution around its axis, and a yearly revolution around the sun, this does not contradict our Torah or our faith, Heaven forbid. For in his Torah God only revealed that which ensures eternal spiritual perfection, things that are far from the normal understanding of a person. But God did not reveal the secret detailed workings of creation. Instead he left this goal for the mind.[10]

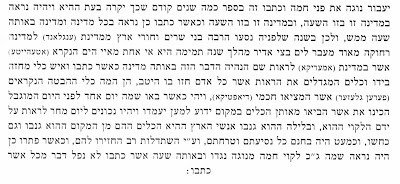

It is no wonder then that Slonimski described the real importance of the transit of Venus for his readers, for it was not a threat to his pro-scientific worldview. Here is the original text:

Notice here how Slonimski had no hesitation in telling his readers the reason why the transit was so important: “if [Venus] happens to pass in front of the sun and we can see it, that would be the time for astronomers to measure the angle it subtends in front of the sun (solar parallax),[11] which is a fundamental and valuable [measure] for astronomy, as those who know these things understand. This is the reason that astronomers went to such lengths at that time to measure the moment of its [Venus’] conjunctions at various locations across the Earth. In 1769, when astronomers calculated that the transit would occur, they all prepared for this time in order to provide the most precise measurements…”

NIVRESHET LENEZ HAHAMAH, 1898

The last rabbinic text we will review was called Nivreshet Lenez Hahamah (The Chandelier of the Sunrise), published in Jerusalem in 1898. Its author was Hiyyah David Spitzer, and he rejected Copernicus and his model, believing instead that the entire universe revolved around the Earth, because “everything, including the Sun, was created for the Earth and for Israel who dwell on it and keep the Torah.” Spitzer’s main interest was in determining the precise times of sunrise and sunset in halakhah, and he spent hours carefully measuring these times in and around Jerusalem. His book was a summary of his findings, but included a criticism of Joseph Ginzburg’s Ittim Lebinah (Times for Wisdom) that had been published in Warsaw in 1886. Ginsberg had defended the heliocentric model and had included a folded pull out chart of the solar system. Spitzer was outraged at Ginsberg’s suggestion that the new astronomy was acceptable to Jews. “I saw things written in [Ittim Lebinah] that bring a person to heresy,” he wrote, and he was particularly incensed to see the colored illustration at the end of the book. “Woe to those eyes that must witness a universe turned upside down.”[12]

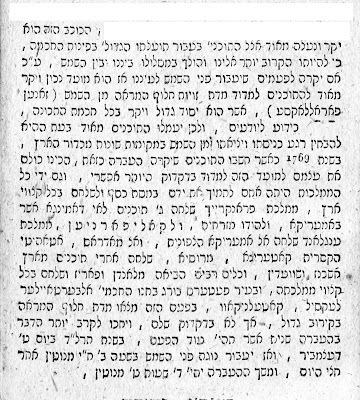

Spitzer did not directly address the transit, but rather the rejected all the calculations about the size of the solar system and the distance to the nearest stars, that had been calculated using the observations of the transit of Venus, as well as estimates of the speed of light that had been made in the nineteenth century. He did so on both scientific and religious grounds. For example, if as astronomers claimed, some stars were 24,000 light years away from Earth, their light could not have reached the Earth that had only exited for some 6,000 years. In addition, what purpose would there have been in creating such remote stars, whose light served no purpose for those on Earth?[13] Finally, since the speed of light is not mentioned in the Talmud, the notion that light has a finite speed cannot be correct. Here is the original text.[14]

Even when judged by the scientific standards of his own time, Spitzer’s work was astonishingly naive. Using a thought experiment he proved to his satisfaction that starlight actually needed only a second to reach the Earth.[15] Furthermore, Spitzer asked how astronomers could possibly have performed the work necessary to claim that some stars were 3,000 light years from Earth. Here is his rather sarcastic objection, aimed at Copernicus himself.[16]

Spitzer claimed that anyone could perform a simple experiment that would refute the notion that light took a finite time to travel vast distances. If, during the day, the door to a house was suddenly closed, it should still be possible to see an image of the sun for some time since the light would take time to travel from the site of the now closed door across the room and into the eye of the observer. Similarly,

if we open a closed door or window…we should not be able to see sunlight for some time, and we should be forced to sit in darkness as if the doors had not been opened. What can be said of this idiocy and stupidity, at which any person would laugh? Rather, as soon as a person opens his eyes he stops seeing nothing and when he opens his eyes at night he immediately sees all the stars, both those nearby that need sixteen years for their light to travel, and those far away whose light takes one hundred and twenty years to reach us.[17]

The motivation for Spitzer’s attack on science was his belief that the scientists themselves had but one goal in mind - to destroy the fundamentals of Jewish belief: “Their entire aim is to deny God’s Torah, to destroy religion, to confuse those who would disagree with them and to embarrass and belittle the sages of Israel.”[18] Here is the original:

These three rabbinic authors had three quite different ways of approaching both the history of the transit of Venus and the science that was deduced from it. Hurwitz was certainly inquisitive about all things scientific, but did not reveal the real goals of the expeditions to observe the transit, because they would raise further questions about the model of the solar system in which he believed- a model in which the Earth was the unmoving center. Slonimski informed his readers of the real goals of the observations and had no issues – religious or scientific - with accepting a universe in which the Earth was not the center. But for Spitzer, the enterprise of astronomy was a vast conspiracy to undermine Torah values. He therefore stretched to reject any science that the transit of Venus bequeathed to future generations.

We’ve come a long way as a people since the transits of 1765 and 1882. The next time this celestial event occurs will be in December 2117. What the Jewish people will look like then is hard to guess, it seems likely that we will continue to argue over the religious meaning of natural events for many generations to come.

________________________________

[1] For details see http://www.exploratorium.edu/eclipse/how.html#PIN2.

[2] Precise times of the transit and its visibility can be found at http://eclipse.gsfc.nasa.gov/OH/tran/TOV2012-Tab03.pdf and http://eclipse.gsfc.nasa.gov/OH/tran/TOV2012-Tab04.pdf. See also http://transitofvenus.nl/wp/where-when/local-transit-times/.

[3] For a good discussion which requires only a minimal understanding of the mathematics see Mark Anderson, The Day the World Discovered the Sun. De Capo Press 2012; 231-240.

[4] Rarely, there is no second transit eight years after the first. The next this occurs will be in 3089.

[5] As somewhat of a disappointment for those for whom Hurwitz exemplified the rationalist movement, Hurwitz revealed that he had written his book to explain a sixteenth century kabbalistic work of Hayyim Vital entitled Sha’arei Kedushah (The Gates of Holiness).

[6] Sefer Haberit Part one #9:8 (1990 ed. 149-150).

[7] Sefer Haberit Part one #3:3 (1990 ed. 50).

[8] Sefer Haberit Part one #9:8 (1990 ed. 52).

[9] There are other reasons that Hurwitz gave for rejecting the Copernican model. These are fully discussed in my forthcoming book.

[10] Slonimski, Kokhava Deshavit , fourth un-numbered page of the author’s introduction.

[11] Slonimski here is absolutely correct. Solar parallax is an angular measurement that is one-half of the angular size of the Earth as seen from the sun. The reason the measurement is so important is that the distance to the sun is the radius of the Earth divided by the solar parallax.

[12] Hayah David Spitzer, Nivreshet Lenez Hahamah (Jerusalem: Blumenthal, 1898). 30b-31a.

[13] Spitzer, Nivreshet Lenez Hahamah 33b-34a.

[14] Ibid. 35a.

[15] Ibid. 34b.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid.

May 29, 2012

The Unsung Heroes of Daf Yomi

Daf Yomi is an extraordinary phenomenon. Thousands of Jews, all over the world, making time every day - every single day - to learn a page of Gemara.

My father, of blessed memory, did not grow up in a religious home and did not have the benefit of a yeshivah education. While he became religious at a young age and always learned Torah in various settings, it was only when he moved to Israel and decided to plunge into Daf Yomi that his studies really took off. Every single day, for nearly twenty years, he walked a half-mile, no matter what the weather, to his Daf Yomi shiur.

Daf Yomi was the brainchild of Rabbi Meir Shapiro, who put forward his idea at the First World Congress of Agudas Yisrael in Vienna, 1923. Agudas Yisrael arranged the last Siyum HaShas at Madison Square Gardens in New York, and are arranging the forthcoming Siyum HaShas, to be held August 1 at MetLife Stadium. These are the greatest public celebrations of Torah in the history of the world.

Unfortunately, at these events, the glory is stolen from the true heroes of Daf Yomi and given to others.

There are two groups of people that are the heroes of Daf Yomi. First are the actual participants. These are largely ba'alei batim - regular people with regular jobs, who have every excuse to not be able to find the time for learning, and yet who make time in their schedules to keep up with the Daf. People learning the Daf on the train to work instead of playing games on their phones or spacing out. People on vacation getting up early to do the Daf before the day's activities. People setting up a system for keeping up with Daf Yomi on their iPads, on their mp3 players, so that mundane activities can be turned into an opportunity to connect with Torah and tradition.

The other heroes of Daf Yomi are the maggidei shiurim - those who prepare and teach the Daf every single day. It's a crushing schedule; I have great admiration for those who keep it up week after week, month after month, year after year. This group also includes those who teach Daf Yomi in other ways, such as those scholars who put together the ArtScroll and Steinsaltz Gemaras and the Daf Yomi Advancement Forum. These open up the Gemara to thousands of people who would not otherwise be able to learn it.

But who are the guests of honor at the grand Siyumim? Who performs the siyum, who makes the speeches, who gets the glory? Not the Daf Yomi participants and not even the maggidei shiurim. Instead, it's the roshei yeshivah.

This is not only tragic; it's also ironic. For the roshei yeshivah are the ones who not only do not learn Daf Yomi; they also often speak out against it!

Now, to be sure, there is room to criticize Daf Yomi. The breakneck pace means that the learning is often superficial and not committed to memory. But there is room to criticize the yeshivah style of learning, too. Spending endless weeks on three lines of Gemara is not exactly the traditional form of study. And learning without coming to clear halachic conclusions is entirely in opposition to the reasons for learning Torah that the Rishonim give.

But whatever the respective merits and drawbacks of the different approaches to learning Gemara, one thing is clear: yeshivos don't do Daf Yomi. Rabbi Meir Shapiro wanted all Jews to be studying the same material at the same time; yeshivos make no such effort. Rabbi Meir Shapiro wanted masechtos of the Gemara that are not usually studied to receive their due respect; yeshivos ignore those masechtos on principle. Daf Yomi is about covering ground in Shas, whereas in most yeshivos, the emphasis is on endless analysis of a few lines of Gemara - the "oker harim" approach instead of the "Sinai" approach. Most fundamentally of all, Daf Yomi is for ba'alei battim, the laymen from whom society is built, not yeshivah students. Why, then, would roshei yeshivah be the ones getting the glory at the Daf Yomi Siyum HaShas, and giving intricate pilpulim in Gemara (and in Yiddish!)? Mah inyan Rav Elya Ber Wachtfogel aitzel Sinai?

If I'm not mistaken, the explanation is as follows. The grand pomp of the Siyum HaShas, with tens of thousands of participants, offers Agudas Yisrael an opportunity to further one of their primary goals: strengthening the Daas Torah form of rabbinic authority, and specifically that of roshei yeshivah.

(Ironically, this latter aspect is not only contrary to tradition of Judaism in general; it is even contrary to the original form of Agudas Yisrael. The Council of Torah Sages of Agudath Israel were originally mostly either community rabbis or those with experience in such roles; today, they are virtually all roshei yeshivah who have never functioned in any such role.)

These are thy Gedolim, O Israel! That is what the siyum haShas does. Make the biggest public Jewish event, and give the stage exclusively to the people that you want to publicize as the heroes and leaders of the Jewish community.

With the glory being given to the exponents of Daas Torah, it provides them with a platform to use the event for the politics of Daas Torah. The last Siyum HaShas took place during the peak of the controversial ban on three of my books. One yeshivah figurehead took advantage of the opportunity to strengthen the ideology of Daas Torah, and capitalized on the martyrs of the Holocaust, in whose memories the Siyum HaShas is dedicated. Rav Mattisyahu Solomon spoke about how the martyrs demand us to reject the "makeshift answers" to conflicts between the Gemara and science that are offered by the "midgets of our generation." Aside from the question of whether approaches to the Gemara offered by countless Geonim and Rishonim and Acharonim can be called "makeshift," and the question of whether the victims of the Holocaust really did die for this belief, one has to wonder why a siyum on Daf Yomi is being used to further such an agenda. It's a siyum haShas, not an Agudas Yisroel convention!

Orthodox Jewish society is made up of many different important people and institutions. We need baalei battim and teachers and schools and lay leaders and yeshivos and roshei yeshivah and universities and academics and shuls and community rabbis and mohelim and shochtim. And there are differences of opinion about whether leadership should be held by lay leaders, community rabbis or roshei yeshivah. But Daf Yomi is not about any of those three groups. They have plenty of opportunities to receive glory, at dinners and Internet Asifas and Agudas Yisroel conventions. Daf Yomi is about the ordinary man who takes his ArtScroll Gemara on the train with him every morning on the way to work. He is the hero of the Siyum HaShas. Let's grant him his well-deserved honor!

May 24, 2012

Guest Post: R. Shimon b. Tzemach Duran's Encyclopedia

Guest post by Rabbi Dr. Seth Kadish, continuing the series on R. Shimon b. Tzemach Duran

The Torah Encyclopedia of the Cosmos and Life on Earth

A few years ago, my son was given a gift by his metapelet (the woman who took care of him along with a small group of children at an after-school day care center in her home). It was a lovely book of “questions and answers” about nature and the world around us, beautifully illustrated with vivid color pictures, and published by a ḥareidiorganization especially for religious children, to show them the wonders of Hashem's creation. My son loves animals, and he loved the book.

At the time, I was working together with a talented talmid ḥakhamwho also serves as a rabbi in the powerful network of ḥareidi-run synagogues in my town, all under the supervision of the official rabbi of the city. Both within his local ḥareidicommunity and outside of it, this particular talmid ḥakhamis considered relatively “moderate” and “open” (in the sense of being deeply involved in the outside world on a positive level and capable of working together with people of all kinds). He even does milu'im (reserve duty), although his children most likely will not.

When I came into his home, I immediately noticed a copy of my child's book on his dining room table, and innocently commented that we had the very same book at home, that it was such a lovely book and my son too had received it as a gift. He replied that the copy on the table wasn't actually his. It belonged to one of the members of the local ḥareidicommunity, who had brought it over for him to look at and make sure that it was “kosher” enough to keep in a Torah home. (That person was apparently concerned that it might have “problematic” ideas like natural history or dinosaurs.) So it seems that if you have a respected place in a ḥareidicommunity (by wearing the right hat and getting the backing of the right rabbi), and yet you are still thought to be relatively broadminded, then people will make you their authority to paskenon the kashrut of childen's books... :-)

That parent who brought a children's book on nature to a rav for a hekhsherrepresents a need that is to be found wherever there are people of a very specific mindset: Religious Jews who think that the Torah teaches hard facts about nature or history which may be contrary to what is generally thought to be true. Communities like this will inevitably demand sources of general knowledge (books, magazines, documentary movies, etc.) that have been “cleaned up”—farendert un farbesert!—to reflect the facts of nature according to what the Torah supposedly teaches whenever such a contradiction seems to exist. A most desirable tool for such a community would be a “Torah encyclopedia,” i.e. a compendium of general knowledge from which all possible heresy has been removed or properly modified, and which in addition contains plenty of information that is of particular use to its readers (such as an emphasis on Jewish history in a way that reflects what is considered to be the proper “Torah attitude”). During the 20th century numerous people and publishing houses made attempts to create books and compendiums of this sort.

But there is also a completely different way to approach the issue. When Yeshiva University granted an honorary doctorate to Rabbi Adin Steinzaltz (this was in 1991 when I was a young semikhah student), he gave a public lecture on Torah u-Madda that I still remember vividly. He began by remarking that when people find themselves confronted by conflicts between science and the Torah, those problems are usually rooted in “popular science” or “popular Torah” (or both). The more serious and broadminded a scholar is, said Rabbi Steinzaltz, the less likely he is to find substance in many or most such apparent contradictions. But at the same time there will always still be some deeper and more nuanced problems, which are far more difficult to deal with, and for which there may not be satisfactory solutions. For these questions the answer is not censorship but honesty, along with the kind of intellectual humility capable of acknowledging that “no one ever died from a question.”

Neither sanitized science nor censored Torah is the answer. Rather, they are both the very root of the problem. Sanitized science is a sin against God's gift to us of the human mind, and against any true appreciation of the wondrous universe that He made. But censored Torah is even more frightening and dangerous, because when the study of God's Torah is limited to those opinions which are deemed acceptable in a certain community at a certain time, or according to certain rabbis who are deemed gedolim, the result will be not just hyper-inflated contradictions between Torah and science but something far worse: a perversion of the Torah itself and thus of God's will for Israel.

Serious questions about Torah and science are nothing new. In every generation mankind tries anew to understand both itself and the universe around it, and this continuing search reveals new truths. At the very same time, men of Torah in every generation—who are themselves also men of truth—honestly strive to understand anew both God's Torah and the world around them using the best tools available to them. This dual engagement not only forces them to meet deep and important challenges head on, but also has the potential to enrich their understanding of mankind, of the universe, and of the Torah itself.

In Rabbis Ḥasdai Crescas and Shimon ben Ẓemaḥ Duran we have two great men who were both outstanding in their pursuit of truth in the realms of Torah and universal knowledge alike. Both of them received the best possible education in both Torah and the science of their time. Both of them possessed encyclopedic knowledge of both realms, and they both continued to fully engage in Torah and science alike throughout their entire lives. Each of them was also the outstanding rabbinic leader in his locale, devoting his life to rebuilding Torah life in the devastated Jewish communities of Spain (Crescas) or to strengthening Torah life within a community of exiles in North Africa (Duran). For both of them, the hard but honest and high-quality work they did when they dealt seriously with the relationship between Torah and science was an integral part of their Torah leadership.

Nevertheless, despite their common origins, similar educations and parallel interests, Crescas and Duran were extremely different as men of the mind. Duran's passion, both in Torah and science, was always for the details. On any given topic, no matter how seemingly trivial at times, he loved to survey (in most cases apparently by heart) every opinion ever expressed in the generations before him, and every possible interpretation that might now be offered in light of them. This characteristic is true of his biblical interpretation, of his talmudic commentaries and halakhic responsa, and also in matters of science: The latter might be anything from personal experimentation to show whether or not spontaneously generated animals can themselves reproduce, to proofs of the existence of angels and demons. Essential to Duran's approach is that the Torah has much of importance to say about nearly every detail of the physical world, and that its wisdom regarding plant and animal life, humanity, and the cosmos is superior to human wisdom of the Aristotelian variety. Duran does not entirely reject allegorical interpretation of the Torah—indeed he occasionally revels in it—but his general approach is that the Torah and Ḥazal fully intended to describe the myriad details of concrete really and that they did so successfully.

Also essential to Duran's approach, however—though usually understated, and sometimes nearly lost entirely in his frequent praise of the Torah as superior to human knowledge—is the assumption that Aristotelian wisdom is generally correct, in its overall approach if not in all of its details. Duran is quite sure that human wisdom has objectively proven a great many truths about the universe (though it has also occasionally stumbled in the places where it contradicts the Torah), the most important of them by far being the existence of God, but no less so for matters such as the biological derivation of semen and the laws of heredity. The literary result of Duran's way of thinking is Magen Avot, as an encyclopedic compendium of knowledge about plant and animal life, human life, and the structure of the cosmos, in which the scientific corpus is corrected when necessary through the superior wisdom of the Torah.

Crescas' intellectual passion was the exact opposite of Duran's: It was nearly always the underlying concepts that fascinated him, not the concrete details. And unlike Duran, he was willing and even eager to cast doubt upon nearly everything. His major goal in Or Hashem is to show that human wisdom can never prove anything absolutely (up to and including the existence of God). And as for the Torah, he felt no compulsion to assume that it describes the concrete reality of the cosmos. A startling example of this is his discussion of the Garden of Eden towards the end of the book: Crescas—fully aware of both Maimonides' allegorical view of Eden and of Naḥmanides' harsh critique of it, in which the latter musters the stories of explorers who have stumbled upon it as proof of its concrete existence—argues that the Eden of Genesis is a concrete place where the body and the soul will be rewarded together at the resurrection. He finds this position compelling because on the one hand it reflects the plain sense of the biblical text, while on the other hand rational inquiry simply has nothing at all to say about the issue. But he nevertheless admits that the question must remain open in principle by its very inclusion in Part IV of Or Hashem, on topics for which the Torah itself mandates no particular view: “Since the Torah does not reveal the true conclusion in these matters, whether to affirm them or reject them, the way to study them is therefore to explain the arguments in both directions for each of them, so that he who investigates them may separate that which is correct from that which is incorrect.” In other words, the ultimate conclusion in matters like these is up to each person, and there is no room for mandating any particular position on matters that the Torah itself fails to mandate.

Crescas' approach to the nature of Eden is typical of his overall approach to both Torah and science. His primary goal is always to deal with the most important conceptual issues, and not with other details: What is a “personality” and does God have one? What is causality? What is “will”? What is “creation”? What are “infinity” and “time”? For each and any of these issues, Crescas always begins by asking what science reallysays and what the Torah really says. Regarding science, what are the various approaches to the issue? If Aristotelian science has proven something, is that proof truly conclusive or is another explanation possible based on a new understanding of the underlying concepts? I emphasize that in no way did Crescas engage in anything remotely like the cheap disparagement of modern science popular among some Orthodox Jews today. Quite the opposite: Crescas didn't engage in polemics so that he could “save” the Torah. Rather, he placed himself firmly at the cutting edge of the science of his day by questioning its underlying concepts, and he was able to offer alternatives that other contemporary scientists found compelling.

Regarding the Torah, Crescas' also asks what it really means in principle regarding each and every concept it touches upon. In this way he delineates the underlying concepts of the Torah (an intricate structure of shorashimand pinnot quite different from Maimonides' 13 ikkarim) for comparison to the possibilities uncovered by human wisdom.

When we compare Duran and Crescas, it is obvious that there are far more contradictions between the Torah and human wisdom for the former than the latter. We might even say, in a certain sense, that this is the result of Duran's reliance on the popular ways to understand both Torah and science in his time. Regarding Torah, the extreme rationalistic approach had already fallen out of favor in the rabbinic world of which he was a part, and allegorical interpretation—while not forbidden—was nevertheless thought to be far less attractive than to say that the Torah correctly described concrete reality. And regarding human wisdom, Aristotelian science in Duran's time was still generally thought to be the only possible way to describe the universe, while those who cast doubt upon its very core (such as Crescas) were still far outside of the mainstream.

But to say that Duran engaged in “popular” Torah and “popular” science would also be extremely misleading. On the contrary, his extraordinary expertise in both fields is second to none in terms of its encyclopedic breadth, depth of understanding, and creative interpretation. By modern standards Duran would have earned several Ph.D.s, and should he have chosen an academic career he might well have been a respected professor of Bible, Talmud, Biology or Philosophy. But more likely is that in our day he would have been a rosh yeshivah and professor at Yeshiva University who teaches semikhah students in the morning and biology or mathematics in the afternoon. What he lacked nonetheless was a passion for rethinking underlying concepts in creative new ways. In other words, he was not at the cutting edge of his fields. But he most certainly was an expert.

Regarding Crescas, however, neither his Torah nor his science can possibly be thought of as “popular” in any way. He was both an expert andat the cutting edge. He tried to rethink assumptions on both sides for every issue he confronted. Nothing in Torah or human wisdom was obvious to him, and nothing was beyond question. By shattering popular notions in both realms he was able to not only reduce the friction between them, but also allowed each one to enrich the other.

In the middle ages, a single science reigned for centuries. But now that the static and dogmatic science of the middle ages is a thing of the past, and our understanding of both the world and the Torah is changing continually, it would seem that Crescas' more flexible approach is the one most appropriate for us today. Nevertheless, Duran's model remains highly relevant as a vivid illustration of how and why such an approach is extremely attractive to Torah Jews (including many to this very day), as well as of the great expertise, creativity and love that must go into building such a model for it to be done well.

Chapter 4 of The Book of Abraham (“The Torah Encyclopedia of the Cosmos and Life on Earth”) is available here(the PDF is a “hybrid” which means that it can also be opened as a fully editable file using LibreOffice). The full index of chapters and blog posts is here.

May 22, 2012

Monitor Lizard; Plus, New Google Search

I recently acquired a new specimen for my forthcoming "Jewish Museum of Natural History." In the Torah's list of sheratzim - small creatures that transmit ritual impurity when dead - one of the creatures is called koach. According to some scholars, this refers to the monitor lizard. Monitors grow to be very large - the desert monitor in Israel grows to around four feet, while in other parts of the world monitors can reach ten feet or more. Accordingly, koach, which means "power," is a worthy name.

The monitor that I acquired is a Savannah monitor. Fully grown, it can reach 4-5 feet in length, but the one that I purchased is just a baby, no more than six inches long. He's incredibly vicious - when I open the cage, he jumps up with an open mouth and tries to bite - but when I hold him for a while, he calms down, and hopefully he will become tamer in due course.

Anyway, the day after I got him, I saw the following e-mail posted to the local Bet Shemesh mailing list:

Subject: Baby MonitorWow, I thought, isn't that a strange coincidence? The day after I get a baby monitor, somebody else wants one! And why does he want one, anyway?

Date: Wed May 9, 2012 10:07 am

Hi i am looking to buy or borrow a baby monitor from somebody. If anybody has one available please respond to this email.

Thank You, Yossi

Then I realized that he wasn't looking for a baby monitor. He was looking for a baby monitor!

* * *

While we're on a light note, you might find the following amusing. Google has made some changes to its search engine; when you search for the name of a person, it now displays a picture, some biographical info, and also some pictures and names of associated people. This is what it displays for "Rabbi Slifkin":

Post-Asifa Reflections

A comprehensive and level-headed write-up by S. about the event: Link

Rabbi Ron Eisemann's reflections on the responsibilities of those at the Asifa to the counter-Asifa: Link

Rabbi Eli Fink's perspective: Link

Finally, here's a fascinating statement by a non-Jew on a report at the Gizmodo tech blog: Link.

May 21, 2012

Rav Steinman's Speech

The focus of Rav Steinman's talk was to set up two polar opposites: learning Torah versus educating oneself to earn a living. There is no nuance to his words; he sets them up as two opposites. In other words, yeshivah ketanah versus high school; yeshivah gedolah versus yeshivah+college; kollel versus working for a living. In this model, Rav Steinman correlates the following with the yeshivah/ kollel/ not-working model:

Being a talmid chacham;Doing mitzvos;Gaining nachas from one's children;Fulfilling the purpose of creation; Gaining everlasting life.

Those who gain a secular education and work for a living are deprived of these; their lot is apparently with the eight billion murderers and thieves and people without seichel. (I don't know if Rav Steinman himself actually believes that. But there are certainly those in his audience who do, and with the complete absence of nuance in his talk, he strengthens that view.)

What about all the Rishonim in Sepharad who studied secular subjects, and saw it as part of their avodas Hashem? Even Chasam Sofer, grandfather of charedi Judaism, studied secular subjects extensively. And certainly there was no mass kollel until a few decades ago! What about all Chazal's teachings on the importance of teaching one's children to earn a trade, and on the value of being self-sufficient?

Rav Steinman also claims that most rich people do not have a strong secular education, which, he says, is because parnassah is all up to Hashem. But actually, there is a distinct general correlation between education and income, and especially between employment and income. If it's all up to Hashem and has nothing to do with hishtadlus, then it's interesting that Hashem has decided to generally reward those who go to college and engage in hishtadlus with parnassah, while those who learn in kollel tend to struggle with poverty.

The greatest irony is in the following quote from Rav Steinman:

"The Chayei Adam writes in one of his books that when he was young the parents did not think about what the child would be later, from what he would earn his living. They only thought about the Torah."

There is no doubt that everyone in attendance understood that by taking the path of yeshivah and kollel, they are following in the holy path of the Chayei Adam. But in fact, the Chayei Adam - Rabbi Avraham Danzig - refused employment as Rabbi of Vilna and instead earned his livelihood as a merchant! (Later in life, when he lost his money, he was forced to take employment as a rabbi. But at no time did he learn in kollel!)

To be sure, Rav Steinman is extraordinary in many ways. But I don't see anything profound in his lecture. Worse, there seems to be much that is untrue and inconsistent with Jewish tradition. Chazal and the Rishonim did not believe that Jews should not learn a trade, engage only in Torah and be supported by others. Chazal and the Rishonim said precisely the opposite.

May 20, 2012

Do Scientists Pray?

In January of 1936, a young non-Jewish girl named Phyllis wrote to Albert Einstein on behalf of her Sunday school class, and asked, "Do scientists pray?" Her letter, and Einstein's reply, can be read below. (Source: Dear Professor Einstein; via Letters of Note)

The Riverside ChurchFor discussion of various possibilities as to how providence interacts with natural law, see chapter four of The Challenge Of Creation. For a discussion of Rambam's view of petitionary prayer, see Marvin Fox, Interpreting Maimonides.

January 19, 1936

My dear Dr. Einstein,

We have brought up the question: Do scientists pray? in our Sunday school class. It began by asking whether we could believe in both science and religion. We are writing to scientists and other important men, to try and have our own question answered. We will feel greatly honored if you will answer our question: Do scientists pray, and what do they pray for?

We are in the sixth grade, Miss Ellis's class.

Respectfully yours, Phyllis

January 24, 1936

Dear Phyllis, I will attempt to reply to your question as simply as I can. Here is my answer: Scientists believe that every occurrence, including the affairs of human beings, is due to the laws of nature. Therefore a scientist cannot be inclined to believe that the course of events can be influenced by prayer, that is, by a supernaturally manifested wish.

However, we must concede that our actual knowledge of these forces is imperfect, so that in the end the belief in the existence of a final, ultimate spirit rests on a kind of faith. Such belief remains widespread even with the current achievements in science. But also, everyone who is seriously involved in the pursuit of science becomes convinced that some spirit is manifest in the laws of the universe, one that is vastly superior to that of man. In this way the pursuit of science leads to a religious feeling of a special sort, which is surely quite different from the religiosity of someone more naive.

With cordial greetings,

your A. Einstein

While on the topic of prayer: Longtime blog reader Rabbi Joshua Cohen of Elizabeth NJ has tragically suffered a stroke. He is only 38 years old and has a wife and four small children. Please pray for Moshe Yehuda Yehoshua Michoel ben Chava, that God should keep him with us and preserve his mind intact.

May 16, 2012

That Bothersome Bardelas!

Many students of the Gemara have been perplexed by a mysterious creature called the bardelas, which appears in several places in Shas. People ask, is it a cheetah? A hyena? A polecat? (And, some people ask, what the heck is a polecat, anyway?) Even Tosafos admits to being perplexed.

The answer is that it depends on who's discussing it.

The first reference to the bardelas is in the Mishnah, discussing the laws regarding which animals are classified as dangerous, such that their owners have a higher degree of liability for damage that they cause:

"The wolf, the lion, the bear, the leopard, the bardelas and the snake are muadin (rated as expected to cause damage). (Mishnah, Bava Kama 1:4)

The word bardelas is not Hebrew or Aramaic - it is quite obviously a transliteration of the Greek pardalis. This name originally referred to the leopard, but cannot refer to the leopard here, since the Mishnah lists the leopard separately. In the Mishnah, it therefore presumably refers to another spotted cat — the cheetah.

The word bardelas is not Hebrew or Aramaic - it is quite obviously a transliteration of the Greek pardalis. This name originally referred to the leopard, but cannot refer to the leopard here, since the Mishnah lists the leopard separately. In the Mishnah, it therefore presumably refers to another spotted cat — the cheetah.However, while the authors and audience of the Mishnah, living in the land of Israel, were familiar with such Greek terms, the same was not true of the sages in Babylon, who had far less exposure to Greek culture. The Babylonian Talmud therefore asks what type of animal the bardelas is, and concludes that it is the hyena:

"What is the bardelas? Rav Yehudah said: The nafraza. What is the nafraza? Rav Yosef said: the afeh. (Talmud, Bava Kama 16a)

The afeh is identical with the af’ah that appears as the Aramaic translation of “valley of the Tzevo’im” in I Samuel 13:18. From an etymological standpoint, af’ah is actually the same word as tzavua, in Aramaic transliteration (where the “tz” sound becomes “a”; cf. eretz becomes ar’a). Thus, the bardelas is being identified with the tzavua. This is definitely the hyena, which, as Rambam points out, is called al-tzaba in Arabic.

The afeh is identical with the af’ah that appears as the Aramaic translation of “valley of the Tzevo’im” in I Samuel 13:18. From an etymological standpoint, af’ah is actually the same word as tzavua, in Aramaic transliteration (where the “tz” sound becomes “a”; cf. eretz becomes ar’a). Thus, the bardelas is being identified with the tzavua. This is definitely the hyena, which, as Rambam points out, is called al-tzaba in Arabic.(While the reference to the bardelas in the Talmud here refers to the hyena, it seems that other references to the bardelas in the Talmud do not refer to the hyena. Instead, they are apparently a corruption of the word mandris, which refers to the mongoose, polecat, or similar such creature.)

Because the Bavli identifies the bardelas as the tzavua, it then runs into a difficulty: that Rabbi Meir adds the tzavua to the Mishnah's list, as an additional animal. The Bavli is forced to answer that the bardelas and tzavua are both the hyena, but that one term refers to the male hyena, and one to the female hyena. While the Gemara attempts to explain why this is necessary, the answer is forced.

Of course, from the perspective of Rabbi Meir (who lived in Eretz Yisrael and understood bardelas to refer to a cheetah), he was not adding a different gender of an already-named animal; he was adding a different animal.

And if it's not bad enough that I have to point out that the Bavli did not understand the Mishnah's terms, the Bavli then goes and speaks about how hyenas transform into bats, and then into thorns, and then into demons.

Siz shver tzu zein ah ZooRabbi!

Fortunately, I'm able to finish the chapter with an inspirational concept, based on Perek Shirah, about how the hyena is an essential part of the circle of life. With thanks to Rav Moshe Shapiro, who told it to me a number of years ago.

(For the definitive study on this topic, see Avraham Ofir-Shemesh, “The Bardelas in Ancient Rabbinic Literature: A Test Case of Geographic Identification” (in Hebrew), Mo’ed 14 (5764) pp. 70-80.)

May 15, 2012

Reflections on the Internet Asifah

When the Asifah was first announced, there were a lot of negative reactions, which I did not understand. OK, perhaps it's slightly over the top to host it in New York's third largest venue. But the Internet does indeed pose great challenges to society in general and Orthodox Judaism in particular, not to mention it being absolutely lethal to charedi society.

People who claim that the enticements of alien values, pornography and heresy always existed, and that the internet doesn't really change anything, are, frankly, naive. Of course these things always existed, but when they become vastly more easily accessible, they are going to be accessed by people (and especially children) who wouldn't otherwise access them. In fact, people who claim that the Internet doesn't change anything are precisely those people who need an Asifah that will open their eyes to the reality!

Then there are those who criticize the "Unity" theme of the event, pointing out that this unity does not include YU, MO, Chabad, and various other groups. But it's difficult to sustain this criticism, when most of us would limit our "unity." YU does not want unity with YCT, YCT does not want unity with Reform, Reform does not want unity with Jews for Jesus, etc. I suppose one could make an argument that some seek to be as restrictive as possible while others seek to be inclusive, but I'm not sure that such an argument would be airtight enough to allow a criticism of charedim for wanting unity only with other charedim.

So, the internet poses serious challenges. That's why the Asifah seems to be a good idea. But then there are some disturbing questions about the nature of this event.

First, despite the problems and dangers of the internet, there are also some tremendous benefits. Now, apparently this Asifah will not be about banning the internet; instead, it will be about using it properly, acknowledging the necessity of the internet for many people in the modern world. But the internet is not just an evil entity that is useful for parnassah. It has numerous benefits, and specifically in one area in which Charedi society fails dismally and which is an even bigger problem than the internet: the scourge of child abuse and other abuses of power. Rav Mattisyahu Solomon, the rabbinic name behind the Asifah, complained to a friend of mine that he knows of three dozen pedophiles walking around Lakewood. Well, it's only because of the Internet that this problem is starting to be addressed! There's plenty of grounds not to like blogs such as UOJ or Failed Messiah, but there's no denying that to the extent that serious steps have been taken to deal with abuse, it is primarily due to such blogs. This makes it especially ironic that an Asifah is being dedicated to the evils of the Internet rather than to the plague of abuse.

Second, it has emerged that the main initiator and organizer of the event is a problematic individual who, by all accounts, would be right at home with Pinter, Schmeltzer and Tropper. It's disturbing that such people always seem to wield power in charedi society. The results are always bad.

Nevertheless, as stated, the Internet does pose serious challenges, and it is something that Orthodox Jewish society should address in a serious way. That's why I liked the guest post. It was not unreservedly cynical (at least, that's not how I read it). It acknowledged that in theory, the Asifah is a good idea, and much good could potentially come of it. Unfortunately, as we have seen with the bans on rationalist Rishonim, the Lipa concert at Madison Square Gardens, Mishpachah, and with defending abusers, EJF, Troppergate, the general effort to condemn all charedi society to enforced poverty and so on, the charedi rabbinic pseudo-leadership seems to never miss an opportunity to mess up.