Natan Slifkin's Blog, page 183

May 12, 2012

Internet Asifa a Great Kiddush Hashem

A guest post by Yosef Drimmel

May 20, 2012, Flushing, NY – A gathering of Ultra-Orthodox Jews from the New York tri-state area was held today at Citi Field. 40,000 men gathered here as approximately 40,000 women followed the events in their neighborhoods via satellite connection. This remarkable event filled with excitement and optimism offered a unique reflection on almost twenty years of Internet use and its effects on a generation.

Leading Rabbis spoke passionately about the various problems facing the community today and urged people to use the Internet and any tools available to address them. An introspective atmosphere was created that united laymen and leadership fostering a commitment to truth and transparency.

The leaders acknowledged they were short-sighted and unrealistic when in the past they attempted to ban the Internet entirely and that methods such as forced signatures on school applications were inappropriate and ineffective. Instead they expressed that many schools need to focus more on the academic and social growth of their students and less on their ability to conform to exclusive rules.

In a humbling manner, some rabbis went so far as to suggest that in the past they felt threatened by the dissemination of information and opinions over the Internet. But in the end they realized that transparency and open dialogue are in the greater interests of Klal Yisroel.

Perhaps the most moving moment of the day was the public apology issued by the leadership in the name of the entire community to the victims of decades of sexual abuse that occurred within our community, noting that it was the Internet that gave a voice to those who had none in the face of the establishment. A new covenant was drawn promising complete cooperation with law enforcement and advocating tougher laws to prevent and report child abuse. A number of enablers were removed from their positions and a new fund to support victims was created.

Some of the speakers also brought attention to the problems of Internet addiction. Expert psychologists and social workers discussed the pathways and pitfalls of excessive use of the Internet, a human challenge more than a religious one. Emphasis was made for teachers and clergy to be aware of individuals suffering from emotional problems of all sorts and to understand the best ways to help people. The disastrous stories of well-meaning but incompetent rabbis who offered counseling proved to be very enlightening to many in the field.

Some attention was paid to the unfortunate availability of pornography on the Internet. While no rabbi wanted to make a fire-and-brimstone rant against basic human instinct, even-keeled advice was offered regarding coping with this distraction and enjoying a healthy lifestyle and fulfilling relationships. A new program was presented to educate brides and grooms on the subject of positive attitudes about intimacy, mutual love and respect.

In the final remarks, the rabbis pledged to move forward with the continuous forging of new ideas. Future gatherings will probably be at a lower cost and scale but focused on actual changes and improvements the community will need to make. Future agendas will include problems and questions such as attitudes towards education and employment, proper allocation of charity funds, funding Jewish education as a community, today’s shidduchim system, agunos, extremism and intolerance, segregation of Ashkenazim and Sefaradim, participation in the Israeli workforce and armed forces, the system of Halachic rulings in Israel and America, reliance on subsidies, and integrity and honesty.

Many of the attendees left the event feeling invigorated about their future and that of their children and grandchildren, echoing the sentiment that through justice and kindness we may merit the coming of the Messiah.

Published on May 12, 2012 20:02

May 10, 2012

You Don't Mess With The Zohar

(A re-post from October 2010)

On the earlier post, Baby's Blue Beads, someone left the following comment:

I think that he's probably correct. You don't mess with the Zohar. Even a relatively moderate charedi figure such as Rav Leff said that somebody who does not believe that the Zohar was written by Rav Shimon Bar Yochai is a heretic (see this link for audio, transcript and analysis). I am told that Rav Leff did later retract this upon being made aware of various information, but the fact that he said it at all shows how widespread such a view is.

It is fairly well known that Rav Yaakov Emden challenged the origins of much of the Zohar, but this doesn't seem to be taken very seriously in traditionalist circles today. Perhaps this is because Rav Emden's opposition to Rav Yonasan Eybeshitz as a Sabbatean, which is popularly (though probably mistakenly) considered unfounded, gives him an image of someone who unjustifiably opposes things. But in the course of my research for my Shiluach HaKein article, I was surprised to find that even a figure as conservative as Chassam Sofer was of the opinion that most of the Zohar was written in a much later period. One would think that the Chassam Sofer would be an unimpeachable authority, but it seems that his views on the Zohar are not widely known.

Personally I have never really explored the issue, beyond the aforementioned view of the Chassam Sofer. There was an article on this which was floating around the net a few years ago, which you can download at this link. I can't give it a haskamah, since I'm not nearly knowledgeable enough in this area to evaluate it, and I haven't even read it carefully; just enough to see that it needs quite a bit of editing! But the quotations at the end, from unnamed Charedi gedolim, are fascinating and show just how divisive and explosive this issue is.

UPDATE: See too this post: Rav Ovadiah Yosef on the Zohar

On the earlier post, Baby's Blue Beads, someone left the following comment:

...the reaction to questioning the Zohar - either its authenticity or its authority - and delving into the superstitious elements or some outdated medieval concepts that underlie the work, will probably be the most visceral and I think more so than any subject, even the evolution issue. The difference is that you don't really see this happening in print, unlike the evolution issue which has been a fairly prominent issue, relatively speaking, in recent decades.

Personally, I think the reaction against an intellectually honest historical approach to the Zohar would be even stronger than the reaction against Rabbi Slifkin. Even many reasonable people who would not necessarily go "on the attack" over it would nonetheless feel it's out of bounds or offensive to question that work.

I think that he's probably correct. You don't mess with the Zohar. Even a relatively moderate charedi figure such as Rav Leff said that somebody who does not believe that the Zohar was written by Rav Shimon Bar Yochai is a heretic (see this link for audio, transcript and analysis). I am told that Rav Leff did later retract this upon being made aware of various information, but the fact that he said it at all shows how widespread such a view is.

It is fairly well known that Rav Yaakov Emden challenged the origins of much of the Zohar, but this doesn't seem to be taken very seriously in traditionalist circles today. Perhaps this is because Rav Emden's opposition to Rav Yonasan Eybeshitz as a Sabbatean, which is popularly (though probably mistakenly) considered unfounded, gives him an image of someone who unjustifiably opposes things. But in the course of my research for my Shiluach HaKein article, I was surprised to find that even a figure as conservative as Chassam Sofer was of the opinion that most of the Zohar was written in a much later period. One would think that the Chassam Sofer would be an unimpeachable authority, but it seems that his views on the Zohar are not widely known.

Personally I have never really explored the issue, beyond the aforementioned view of the Chassam Sofer. There was an article on this which was floating around the net a few years ago, which you can download at this link. I can't give it a haskamah, since I'm not nearly knowledgeable enough in this area to evaluate it, and I haven't even read it carefully; just enough to see that it needs quite a bit of editing! But the quotations at the end, from unnamed Charedi gedolim, are fascinating and show just how divisive and explosive this issue is.

UPDATE: See too this post: Rav Ovadiah Yosef on the Zohar

Published on May 10, 2012 20:20

May 8, 2012

What You Can Do

In the last post, I announced the development of The Jewish Museum Of Natural History. There are a few areas in which people might be able to help:

1) There are certain items required that can only be purchased in the US, England and Europe, and are too large or fragile to go into regular luggage, such as small display enclosures. If you are making aliyah from these countries and have space on your lift, that would be appreciated (of course, the space would be paid for).

2) A 501(c)(3) charitable organization needs to be set up in the US. If you have any expert advice to contribute regarding this, or can recommend a good lawyer - ideally, one who is supportive of the project and is willing to charge a low rate! - please be in touch.

3) Donations of unusual shofars, taxidermy, certain animals (if you live in Israel) and animal husbandry equipment, and of course funds, will be gratefully appreciated!

4) If you have any other ideas, or would like to be involved in some capacity, please be in touch.

If you can help with any of the above, don't notify me by way of the comments; instead, please email me.

1) There are certain items required that can only be purchased in the US, England and Europe, and are too large or fragile to go into regular luggage, such as small display enclosures. If you are making aliyah from these countries and have space on your lift, that would be appreciated (of course, the space would be paid for).

2) A 501(c)(3) charitable organization needs to be set up in the US. If you have any expert advice to contribute regarding this, or can recommend a good lawyer - ideally, one who is supportive of the project and is willing to charge a low rate! - please be in touch.

3) Donations of unusual shofars, taxidermy, certain animals (if you live in Israel) and animal husbandry equipment, and of course funds, will be gratefully appreciated!

4) If you have any other ideas, or would like to be involved in some capacity, please be in touch.

If you can help with any of the above, don't notify me by way of the comments; instead, please email me.

Published on May 08, 2012 23:54

May 7, 2012

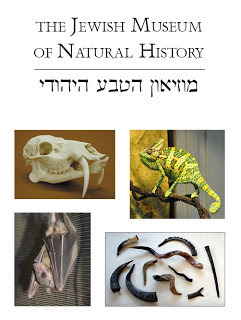

The Jewish Museum of Natural History

I am thrilled to announce that plans are moving ahead for the development of "The Jewish Museum Of Natural History." The mission is outlined below, and you can download a full prospectus at this link.

I am thrilled to announce that plans are moving ahead for the development of "The Jewish Museum Of Natural History." The mission is outlined below, and you can download a full prospectus at this link.Mission

The Jewish Museum of Natural History will be a unique institution. Its primary goals are twofold: To enhance appreciation and understanding of Scripture, Talmud and Jewish tradition via the natural world, and to thereby also enhance appreciation and understanding of the natural world itself. Visitors will learn about Scriptural and Midrashic symbolism, Jewish law and history, and the natural history of the Land of Israel.

The museum will accomplish this mission via a combination of extraordinary live and inanimate exhibits, including taxidermy mounts and other intriguing biological artifacts. All exhibits, including live specimens, will be hands-on, since tactile experiences are the most powerful. Visits will be conducted exclusively via guided tours, in order to maximize the educational value. The Jewish Museum of Natural History will also serve as an invaluable educational resource, providing teacher training courses, extended lecture series, and trainee assistant curator programs for teens.

The nucleus of the collection has already been assembled and is licensed by the Nature Reserves Authority. Plans are currently underway for a temporary facility, under the auspices of a Foundation created for the museum and its associated publications. The long-term goal is to construct a building for the museum in the city of Bet Shemesh. Although housing a population of 80,000 which is projected to double in the next decade, and home to a large Anglo population which regularly receives visitors from abroad, Bet Shemesh lacks any kind of tourist attraction. The Jewish Museum of Natural History will fill that gap in a unique way.

Published on May 07, 2012 10:14

May 6, 2012

Lactating Snakes and Vampire Owls

What are tanim? I used to think that this was fairly straightforward, but I recently realized that there may be a basic error that was made by those who studied the natural history of Scripture and assigned names for animals in Modern Hebrew.

In Scripture, there is mention of tanin (with a nun at the end) and tanim (with a mem at the end). The former is a generic term for serpentine/ monstrous creatures such as snakes, crocodiles, and whales (singular tanin, plural taninim). But what are the tanim (which, incidentally, is a plural form; the singular is tan)? The tanim are mentioned in several places in Scripture as creatures that live in ruins and desolate areas, along with birds called bnos ya'anah (ostriches or some kind of owl), and they are described as making a wailing sound. Thus far, they could be either jackals or a different type of owl.

There is one crucial verse which is thought to conclusively resolve this:

There is one crucial verse which is thought to conclusively resolve this:

This all seems straightforward. But there is an assumption being made here, which is not necessarily correct! The assumption being made is that the Scriptural writer knew which animals nurse their young and which don't. However, as Rambam and others make clear, the prophets (and even the Torah) speaks within the scientific worldview of antiquity. Thus, there is no reason to assume that the zoological description is necessarily accurate.

What does this mean with regard to tanim? One scholar, Othniel Margalith, argues that the verse in Eichah should be read as tanin - which matches the Septuagint's translation of draco (serpent). Margalith claims that this verse reflects a belief in antiquity that snakes nurse their young on milk. As evidence, he points to clay cobras from Beth Shean which are seemingly formed with breasts. Thus, the verse in Eichah is referring to snakes, and is not talking about the wailing tanim of the ruins that are mentioned elsewhere in Scripture. These can therefore be identified as some kind of owl.

While Margalith's view should certainly be taken into consideration, I don't know if it is necessarily correct. The interpretation of such clay figurines is debated; even if they do depict breasts, some argue that it may reflect artistic or idolatrous concepts rather than zoological beliefs.

(See too R. Yaakov of Lisa, Palgei Mayim (link: p. 171, second column, line 8), who, in a different approach, says that Chazal believed that snakes would take milk from women. I haven't been able to find any reference to such a thing in Chazal, and I would be indebted if anyone can point me to such a source.)

But Margalith's approach led me to consider another possibility. Even if the verse in Eichah should be read as tanim (and is referring to the wailing tanim of the ruins), does it rule out owls? As R. Josh Waxman pointed out in another context, there was an ancient belief in a strange type of owl called a strix, which was thought to nurse its young on milk.

There are advantages to positing that tanim are strix owls rather than jackals. Tanim are always translated by Targum Yonasan as yarudin, and the Talmud Yerushalmi (Kilayim 8:4) identifies these as birds. Thus, the most ancient traditions for the identity of tanim favors owls rather than jackals (whereas the earliest source for positively identifying them as jackals is Tanhum Yerushalmi, in the thirteenth century).

A further piece of evidence is that Gemara in Sanhedrin 59b mentions a “yarod nala”; according to Sokoloff's Dictionary Of Jewish Babylonian Aramaic, s.v. נלא, this refers to a demon or vampire. The strix was believed to be a demonic bird which sucked people’s blood, and thus this phrase in the Gemara is further indication that the yarod (which is the tan) is the strix.

A further piece of evidence is that Gemara in Sanhedrin 59b mentions a “yarod nala”; according to Sokoloff's Dictionary Of Jewish Babylonian Aramaic, s.v. נלא, this refers to a demon or vampire. The strix was believed to be a demonic bird which sucked people’s blood, and thus this phrase in the Gemara is further indication that the yarod (which is the tan) is the strix.

Of course, it's still not absolutely straightforward. The verse in Eichah refers to the young of the tanim as gurim. This word is elsewhere used only to describe lion cubs, which would perhaps favor identifying tanim as jackals, which have cubs, rather than strix owls. Still, it seems that Chazal, at least, understood the term to refer to lactating vampirous strix owls. And one thing is clear: the identity of the tanim of Scripture is certainly not as straightforward as is often assumed.

In Scripture, there is mention of tanin (with a nun at the end) and tanim (with a mem at the end). The former is a generic term for serpentine/ monstrous creatures such as snakes, crocodiles, and whales (singular tanin, plural taninim). But what are the tanim (which, incidentally, is a plural form; the singular is tan)? The tanim are mentioned in several places in Scripture as creatures that live in ruins and desolate areas, along with birds called bnos ya'anah (ostriches or some kind of owl), and they are described as making a wailing sound. Thus far, they could be either jackals or a different type of owl.

There is one crucial verse which is thought to conclusively resolve this:

There is one crucial verse which is thought to conclusively resolve this: Even the tanin have bared their breast, nursing their cubs; yet the daughter of my people has become cruel, like ya’enim in the wilderness. (Eichah 4:3)In this verse, there is a kri/kesiv mesorah that the word written as tanin is to be read as tanim. There is reason to believe that this is the correct reading - no serpentine creature nurses its young. Thus, tanim are mammals. Hence, the tanim described elsewhere as wailing creatures of the wilderness must be jackals, not owls. That is why in modern Hebrew, jackals are called tanim.

This all seems straightforward. But there is an assumption being made here, which is not necessarily correct! The assumption being made is that the Scriptural writer knew which animals nurse their young and which don't. However, as Rambam and others make clear, the prophets (and even the Torah) speaks within the scientific worldview of antiquity. Thus, there is no reason to assume that the zoological description is necessarily accurate.

What does this mean with regard to tanim? One scholar, Othniel Margalith, argues that the verse in Eichah should be read as tanin - which matches the Septuagint's translation of draco (serpent). Margalith claims that this verse reflects a belief in antiquity that snakes nurse their young on milk. As evidence, he points to clay cobras from Beth Shean which are seemingly formed with breasts. Thus, the verse in Eichah is referring to snakes, and is not talking about the wailing tanim of the ruins that are mentioned elsewhere in Scripture. These can therefore be identified as some kind of owl.

While Margalith's view should certainly be taken into consideration, I don't know if it is necessarily correct. The interpretation of such clay figurines is debated; even if they do depict breasts, some argue that it may reflect artistic or idolatrous concepts rather than zoological beliefs.

(See too R. Yaakov of Lisa, Palgei Mayim (link: p. 171, second column, line 8), who, in a different approach, says that Chazal believed that snakes would take milk from women. I haven't been able to find any reference to such a thing in Chazal, and I would be indebted if anyone can point me to such a source.)

But Margalith's approach led me to consider another possibility. Even if the verse in Eichah should be read as tanim (and is referring to the wailing tanim of the ruins), does it rule out owls? As R. Josh Waxman pointed out in another context, there was an ancient belief in a strange type of owl called a strix, which was thought to nurse its young on milk.

There are advantages to positing that tanim are strix owls rather than jackals. Tanim are always translated by Targum Yonasan as yarudin, and the Talmud Yerushalmi (Kilayim 8:4) identifies these as birds. Thus, the most ancient traditions for the identity of tanim favors owls rather than jackals (whereas the earliest source for positively identifying them as jackals is Tanhum Yerushalmi, in the thirteenth century).

A further piece of evidence is that Gemara in Sanhedrin 59b mentions a “yarod nala”; according to Sokoloff's Dictionary Of Jewish Babylonian Aramaic, s.v. נלא, this refers to a demon or vampire. The strix was believed to be a demonic bird which sucked people’s blood, and thus this phrase in the Gemara is further indication that the yarod (which is the tan) is the strix.

A further piece of evidence is that Gemara in Sanhedrin 59b mentions a “yarod nala”; according to Sokoloff's Dictionary Of Jewish Babylonian Aramaic, s.v. נלא, this refers to a demon or vampire. The strix was believed to be a demonic bird which sucked people’s blood, and thus this phrase in the Gemara is further indication that the yarod (which is the tan) is the strix.Of course, it's still not absolutely straightforward. The verse in Eichah refers to the young of the tanim as gurim. This word is elsewhere used only to describe lion cubs, which would perhaps favor identifying tanim as jackals, which have cubs, rather than strix owls. Still, it seems that Chazal, at least, understood the term to refer to lactating vampirous strix owls. And one thing is clear: the identity of the tanim of Scripture is certainly not as straightforward as is often assumed.

Published on May 06, 2012 07:21

May 2, 2012

A Close Shave... But With What?

Last week, I was invited to the Yom Ha-Atzma'ut celebrations at the home of the President of Israel. It is a long ceremony, involving awards to the 120 most outstanding soldiers, songs by the Prime Minister and President (!), and lunch. For various reasons, I was not able to go.

Which was just as well. It turns out that the caterer discovered, the day before Yom Ha'Atzma'ut, that the meat had all spoiled. Shockingly, he decided to replace it with meat from a supplier in Abu Ghosh - which was, of course, entirely treife. Somehow slipping it past the mashgiach, the caterer thought he had gotten away with it. But it transpired that he had been caught on the security cameras in Abu Ghosh. Unfortunately, this was only after the meat had been eaten by the guests.

And so it's just as well that I didn't attend the event. Because if I would have gone, then I would have inadvertently eaten treife, and... what?

As Professor Menachem Kellner explains, in Maimonides' Confrontation With Mysticism , the consequences of inadvertently eating treife are subject to a dispute between Rambam (Maimonides) and Ramban (Nachmanides).

According to Nachmanides (and probably most other rabbinic authorities), non-kosher food inherently houses spiritual harm. If one had some kind of metaphysical measuring device like those of the Ghostbusters, one could take a measurement of it. Like poisonous food, it will cause harm even if one eats it entirely inadvertently.

According to Nachmanides (and probably most other rabbinic authorities), non-kosher food inherently houses spiritual harm. If one had some kind of metaphysical measuring device like those of the Ghostbusters, one could take a measurement of it. Like poisonous food, it will cause harm even if one eats it entirely inadvertently.

According to Maimonides, on the other hand, the laws of kashrus are institutional rather than relating to some kind of metaphysical reality. There are various reasons why we must not eat non-kosher food, but it has nothing to do with anything metaphysical inherent to the food itself. Consequently, if one inadvertently and unknowingly eats non-kosher food, one's soul has not been harmed.

Personally, the thought of eating treife food, even inadvertently, gives me the heeby-jeebies. I guess I'm not so much of a rationalist, after all.

Which was just as well. It turns out that the caterer discovered, the day before Yom Ha'Atzma'ut, that the meat had all spoiled. Shockingly, he decided to replace it with meat from a supplier in Abu Ghosh - which was, of course, entirely treife. Somehow slipping it past the mashgiach, the caterer thought he had gotten away with it. But it transpired that he had been caught on the security cameras in Abu Ghosh. Unfortunately, this was only after the meat had been eaten by the guests.

And so it's just as well that I didn't attend the event. Because if I would have gone, then I would have inadvertently eaten treife, and... what?

As Professor Menachem Kellner explains, in Maimonides' Confrontation With Mysticism , the consequences of inadvertently eating treife are subject to a dispute between Rambam (Maimonides) and Ramban (Nachmanides).

According to Nachmanides (and probably most other rabbinic authorities), non-kosher food inherently houses spiritual harm. If one had some kind of metaphysical measuring device like those of the Ghostbusters, one could take a measurement of it. Like poisonous food, it will cause harm even if one eats it entirely inadvertently.

According to Nachmanides (and probably most other rabbinic authorities), non-kosher food inherently houses spiritual harm. If one had some kind of metaphysical measuring device like those of the Ghostbusters, one could take a measurement of it. Like poisonous food, it will cause harm even if one eats it entirely inadvertently.According to Maimonides, on the other hand, the laws of kashrus are institutional rather than relating to some kind of metaphysical reality. There are various reasons why we must not eat non-kosher food, but it has nothing to do with anything metaphysical inherent to the food itself. Consequently, if one inadvertently and unknowingly eats non-kosher food, one's soul has not been harmed.

Personally, the thought of eating treife food, even inadvertently, gives me the heeby-jeebies. I guess I'm not so much of a rationalist, after all.

Published on May 02, 2012 03:07

April 30, 2012

Praying For Survival: The Hassidization of Litvaks

Lately, with a number of elderly Haredi Gedolim being very sick, there has been many people in the Haredi community calling upon the community to pray for their health. Previously, I have discussed whether this is as much of a life-changing crisis as some are describing it, but in this post I want to discuss a different point. I was somewhat taken aback to see that much of the talk about the need to pray for the health of the Gedolim asserts that the reason why it is so important is that the Gedolim are needed in order to pray for our own survival.

Let's leave aside, for now, the question of whether this makes the entire effort somewhat selfish. I am more intrigued by the theological concept that is implicitly being presented here. Instead of us praying for our survival, we are better off simply praying for the Gedolims' survival. The Gedolim are assumed to be better at praying for our survival than we are, and thus, to the extent that our prayers are effective, they are best directed towards the health of the Gedolim, rather than directed towards the things that we want the Gedolim to pray for.

Now, this seems to be consistent with Chassidic thought. In Chassidic circles, it is only the Admor that has a significant connection to God. Everyone else connects to God via the Admor - eating his shirayim, etc. But is it consistent with Litvishe thought? My impression is that Litvaks had traditionally subscribed to קרוב ה' לכל קוראיו - "God is close to all that call upon Him." You don't pray for someone else to be able to pray for you - you just pray yourself for the things that you need. Am I wrong?

(On another note, I still have an opening in my schedule for Shabbos July 21 in the NY/ NJ region and Shabbos August 11 in LA - please write if you want to schedule a scholar-in-residence weekend.)

Published on April 30, 2012 04:53

April 25, 2012

Yom Ha-Atzmaut and Rationalism

(A re-post from two years ago, with new material at the end)

What is the connection between Yom Ha-Atzmaut and rationalism?

What is the connection between Yom Ha-Atzmaut and rationalism?

I would like to suggest that the rationalist/ non-rationalist divide serves to explain one very minor aspect of the dispute between those who celebrate Yom HaAtzmaut and those who do not.

When I was in yeshivah, I remember that we all viewed the Biblical and Talmudic era as being something like Tolkien's Middle-Earth. There were giants, dwarfs, fabulous beasts, and magicians. Our revered ancestors possessed extraordinary powers; Chazal could instantly incinerate people by looking at them, and any of the Avos would be able to defeat hundreds of people in battle without even raising a finger. These people were of perfect character and of a spiritual level that we cannot even begin to start to attempt to grasp in the slightest degree; if we were to even look at them, we would drop dead. In the wonderful sefer Sichas Chullin, which explains the topics in Maseches Chullin with the aid of diagrams, the author apologizes for including simple illustrations of people involved in slaughtering animals, etc.; he assures the reader that these are certainly not intended to be depictions of Chazal, "who have the visage of a Seraph, and no person shall see them and live." (Which is paraphrasing a verse referring to God, not man.) And this is Chazal; the figures in Tenach were many orders of magnitude greater.

These, it was considered, are the type of people who are involved in events of religious significance. Super-special people; not ordinary people like you or me, and certainly not irreligious people. I think that this perhaps contributes to the Charedi unthinkability of attributing religious significance to the State of Israel and its victorious battles. How could there be religious significance to events in which the pivotal people were ordinary folk, and in many cases not even religious?

People with a more rationalist outlook, on the other hand, don't look at people from the Biblical and Talmudic era as being that different from people today. Accordingly, it is perfectly possible for people of today to be involved in events of monumental religious significance.

ADDITION:

See too Rabbi Dov Lipman's article in the Jerusalem Post, where he points out the following:

(In the picture: The Israeli flag flying at Ponovezh yeshivah in Bnei Brak)

What is the connection between Yom Ha-Atzmaut and rationalism?

What is the connection between Yom Ha-Atzmaut and rationalism?I would like to suggest that the rationalist/ non-rationalist divide serves to explain one very minor aspect of the dispute between those who celebrate Yom HaAtzmaut and those who do not.

When I was in yeshivah, I remember that we all viewed the Biblical and Talmudic era as being something like Tolkien's Middle-Earth. There were giants, dwarfs, fabulous beasts, and magicians. Our revered ancestors possessed extraordinary powers; Chazal could instantly incinerate people by looking at them, and any of the Avos would be able to defeat hundreds of people in battle without even raising a finger. These people were of perfect character and of a spiritual level that we cannot even begin to start to attempt to grasp in the slightest degree; if we were to even look at them, we would drop dead. In the wonderful sefer Sichas Chullin, which explains the topics in Maseches Chullin with the aid of diagrams, the author apologizes for including simple illustrations of people involved in slaughtering animals, etc.; he assures the reader that these are certainly not intended to be depictions of Chazal, "who have the visage of a Seraph, and no person shall see them and live." (Which is paraphrasing a verse referring to God, not man.) And this is Chazal; the figures in Tenach were many orders of magnitude greater.

These, it was considered, are the type of people who are involved in events of religious significance. Super-special people; not ordinary people like you or me, and certainly not irreligious people. I think that this perhaps contributes to the Charedi unthinkability of attributing religious significance to the State of Israel and its victorious battles. How could there be religious significance to events in which the pivotal people were ordinary folk, and in many cases not even religious?

People with a more rationalist outlook, on the other hand, don't look at people from the Biblical and Talmudic era as being that different from people today. Accordingly, it is perfectly possible for people of today to be involved in events of monumental religious significance.

ADDITION:

See too Rabbi Dov Lipman's article in the Jerusalem Post, where he points out the following:

But what about the claim that monumental steps towards the Messiah’s arrival cannot possibly be driven by secular leaders? This argument holds no weight. The Bible, especially in the book of Kings, reveals that God is willing to perform great miracles and brings salvation through individuals far more anti-religious than any of the state’s secular founders and leaders.As I mentioned above, though, all this only explains one very minor aspect of those who do not celebrate Yom Ha'Atzmaut. The main reason, especially today, has very little to do with halachic or religious positions, and a lot more to do with sociological factors. See my monographs on "The Novelty of Orthodoxy" and "The Making of Haredim" to understand why the notion of being a fully participating citizen of the State of Israel, and the very idea of incorporating a new entity (The State of Israel) into one's religious worldview, is entirely at odds with the isolationism and traditionalism of charedi society. They'd be uncomfortable with it even if the Ribbono Shel Olam Himself were to say that it's kosher.

King Ahab, who married a non-Jew, encouraged idol worship and stood silent while his wife killed prophet, was told by a prophet that he would lead troops to miraculous victory (see Kings I 20:13-14). Omri, identified as a greater sinner than all the wicked Jewish kings before him, (Kings I 16:25), merited a long-lasting dynasty because he added a city to the Land of Israel (Sanhedrin 102b) despite the fact that his intention in adding that city was to eliminate Jerusalem as the focus of the Jews! The secular leaders of the State of Israel most certainly have more noble intentions in building Israeli cities and, thus, can certainly merit playing a role in the redemption process.

Kings I, Chapter 14 describes Yeravam as a terrible sinner who caused others to sin, as well. Despite his sins, he led the Jews to victory in restoring the borders of Israel. The Bible its elf explains that the time came for this “redemption” and God used whoever the leader was at the time, despite his being irreligious.

(In the picture: The Israeli flag flying at Ponovezh yeshivah in Bnei Brak)

Published on April 25, 2012 21:13

April 24, 2012

Rabbi Storch Responds

A guest post by Rabbi Ari Storch, in response to yesterday's review of his book by David Zinberg

Prior to responding to the recent critique by David S. Zinberg of my work, The Secrets of the Stars, let me thank Rabbi Slifkin for graciously allowing me to respond on his blog. A careful reading of Mr. Zinberg’s review allows the reader to recognize that he is not criticizing my work inasmuch as he is instead criticizing the use of astrology by many sages. The issues raised with my work such as determinism, are actually concerns non-specific to my work.

My work, herein called SOTS, was intended to give the reader a clearer perspective of the thought processes of many of our sages. It is irrefutable that many great rabbinic authorities, although not all, were firm believers in astrology. While one may simply ignore these statements on the basis that they are “pseudoscience”, those who choose to actually learn from these statements to glean further understanding of Torah would benefit from a knowledge of the outlook and of the mindset of that day. Whether or not astrological beliefs should be rejected or adhered in today’s day and age is completely irrelevant to this discussion. In my work I attempt to build a framework to understand works containing astrological references such as: Midrash Rabbah, Tanchuma, Pesikta Zutresa, Midrash Hagadol, Baraisa D’Mazalos, the Talmud, and many others; similarly, of the later sages: Rashi, Tosefos, Ramban, Rashba, Rabbeinu Bacheye, Rokeach, Recanati, R. Yosef Gikatilla, R. Avraham ibn Ezra, R. Avraham ibn Chiya, Tur, R. Yosef Karo, Rema, and others.

While Mr. Zinberg as dissatisfied with how I address the conflict between determinism and freewill, he ignores that this is not my own conclusion, but rather that of earlier Torah giants who believed in astrology. Mr. Zinberg seems to have ignored that I directly cited from the Ibn Ezra when discussing this matter. As for future predictions, Chazal (Sukkah 29a) make the statement that eclipses are predictions of ominous events, yet, even in their era eclipses were predictable via the Saros Cycle. They understood that throughout history, the world was predisposed to certain occurrences, but that has no bearing on how a person chooses to act. Just because a hurricane will inevitably hit does not take away one’s freewill. Thus, my very isolated statement with regards to the events of six-hundred years were an assessment of the predisposition of the world as based on the imagery utilized by the sages who believed in astrology. I have never suggested nor attempted to calculate when the messiah will arrive. In fact, I am a firm believer that the practice of doing so is frowned upon by our Sages as seen in Sanhedrin 97b. (The reader should not think that there were no authorities who have attempted to predict these matters, though. In his Megilas Hamegaleh, R. Avraham ibn Chiya did, in fact, estimate the date of the messiah via astrological reasoning. This date was then repeated by Ramban and others. Alas, the projected date has come and gone.) Furthermore, this is an isolated comment and the book in its entirety does not address future events, rather, it focuses on the perspective of the many sages’ view of the natural world as it pertains to the celestial realm.

Mr. Zinberg harshly criticized the exclusion of Rambam’s opinion in SOTS. Any student of medieval rabbinic literature is well aware of Rambam’s staunch opposition to the acceptance of astrology. Rambam made that clear in the eleventh chapter of hilchos avodas kochavim of his Mishneh Torah where he expresses an extremely derisive view of astrology as well as in Moreh Nevuchim, Peirush Hamishnayos, his letter to Montpelier (Marseilles), and other works. However, SOTS was never intended to be a comprehensive compilation of Jewish thought regarding astrology. As such, there was no need to cite Rambam or mention his ardent opposition. The exclusion of his opinion was purely because it had no relevance. The purpose of SOTS was to allow one to understand many of those otherwise confounding statements of Chazal, as most of modern day man is not proficient in medieval astronomy or astrology. My goal was to provide the perspective of those sages that did espouse these beliefs and allow one to recognize how these sages saw beauty and significance in this world. Furthermore, throughout much of our history, our Torah writings are replete with these colorful astrological/astronomical references, and neglecting them by simply writing them off as archaic would tragically erase much of their message. One can understand these statements regardless of whether or not he believes astrology to be a valid science.

But to address Mr. Zinberg’s point, in a previously published work, Tiferes Aryeh: Kuntras Hatemimus, I addressed the rabbinic dispute of astrology more comprehensively and detailed Rambam’s approach there. I concluded that, philosophically, one is free to believe or reject astrology. (Although I feel the need to note that practicing forms of astrology is certainly prohibited and one should consult a competent rabbi prior to engaging in this practice. This is even if one feels that these practices are silly and baseless.) My personal positions on the validity of astrology are neither addressed in this earlier work nor in SOTS.

Mr. Zinberg mentions my creativity and provides an example that is intended to show how I have taken quite the literary license and is, in his words, “bizarre.” Although I do believe I have a creative side, it probably would have been best for Mr. Zinberg to have reread that passage prior to mentioning the association of the tribe of Judah to Cancer, the crab. This association was not one fabricated or concocted by me, rather, it is, in fact, mentioned by the Pesikta Zutresa which is clearly footnoted in the text itself. The Pesikta Zutresa mentions that the twelve tribes are associated with the signs of the zodiac and that the tribes are aligned to the months based on the order of their birth. As such, Judah, the fourth son, is associated with the month of Tammuz and the sign of Cancer. I am merely attempting to show the reader how this Midrash understood these associations.

Another concern of Mr. Zinberg seems to be my understanding that much of Greek mythology parallels biblical narratives. I find it difficult for one to reject this assessment. There are numerous examples of both biblical and midrashic narratives bearing an extremely close resemblance to Greek mythology. The story of the twins of Gemini, Castor and Pollux, invading the kingdom of Attica to save their sister Helen who had been kidnapped by King Theseus bears a striking resemblance to the invasion of Shechem by the two brothers, Shimon and Levi, after their sister Dinah had been kidnapped by Prince Shechem. Procustes’ bed in which he would stretch the legs of short wayfarers and gruesomely amputate those of tall wayfarers is identical to the talmudic account (Sanhedrin 109b) of the ways in which the people of Sedom would act.

Mr. Zinberg attempts to marginalize the Ibn Ezra by painting him as controversial. Despite this attempt, anyone who has studied R. Avraham ibn Ezra’s writings knows that they are piercing, invaluable, and a testament to his great scholarship. Mr. Zinberg mentions that in some circles Ibn Ezra’s views are unpopular and this, no doubt, is an attempt to present me as one who unknowingly rests upon, what Mr. Zinberg feels to be, unstable shoulders. I am fully aware of the views he mentions and have even addressed them in a public forum. Those who are offended by citations of the Ibn Ezra will probably not be comfortable with SOTS (or a standard Mikraos Gedolos for that matter), but somehow I suspect that was not what Mr. Zinberg was getting at with those comments. Although I would have no problem relying solely upon the Ibn Ezra, he is but one of many sources cited in my work. I have not tallied how many times I have quoted specific sources, but I would venture to say that I quote Rabbeinu Bacheye just as frequently, in addition to many other Rishonim and Midrashim. The controversies surrounding Ibn Ezra’s writings are irrelevant to SOTS. Just as I did not mention that science has honored Ibn Ezra by naming a crater on the moon, Abenezra, for him; I did not mention the Ibn Ezra’s views with regards to post-Mosaic authorship. Although these are fascinating tidbits of information, they have no bearing on SOTS.

The attempt to discredit Ibn Ezra, and my usage of him as a source in my work, by citing Maharshal’s scathing critique of Ibn Ezra is at best disingenuous. Mr. Zinberg, very apologetically, rejects small portions of Rambam’s Mishneh Torah due to discrepancies between those writings and contemporary science (“To be fair, much of Maimonides’ cosmology, summarized in Basic Principles of the Torah, the very first section of the Mishneh Torah, is also obsolete ...”), but it seems clear that he has no problem adhering to the rest of Mishneh Torah. If Mr. Zinger defers to Maharshal’s opinion as to which books should be read and which should be censored, then he should wholeheartedly reject the adherence of any opinion espoused by Rambam in Mishnah Torah. Just a few lines prior to Mr. Zinberg’s citation of Maharshal’s criticism of Ibn Ezra, the Maharshal comments on Rambam’s Mishnah Torah, “Therefore, one cannot accept [Mishnah Torah] in an intellectually honest way because one never knows what is the true source [of Rambam’s halacha].” I have tremendous respect for Maharshal, but it would seem that most scholars have not adhered to these statements found in his introduction to Yam Shel Shlomo.

Mr. Zinberg states that my work is part of an increasing trend to prove that the Sages were infallible. Nowhere has Mr. Zinberg shown where this idea was gleaned from SOTS, nor is this concept even expressed in the work. I can only guess that he misunderstood two of my statements (in an over two-hundred page work) that express my amazement of how two interpretations of Chazal bear striking resemblance to scientific thought that had not yet been discovered at their time. Mind you, had these two statements of mine not been included in SOTS, the work would remain entirely intact, and yet, Mr. Zinberg attempts to discredit the entire book based upon them. Furthermore, he has grossly misinterpreted my words as I have NEVER stated in my work that Chazal were infallible. I have not addressed the topic of fallibility of the Sages in this work, or in any other public forum. This topic, albeit fascinating and a point of heated debate in recent years, has no place in my SOTS, as it is addresses an entirely different topic. Once again, the purpose of the work was to display the beauty of the world, specifically the celestial objects, as seen through the perspective of many of our great sages. It does not take a stance, nor does it project an opinion one way or another as to whether or not the Sages were able to err. I hardly see how the Sages’ comparison of the twelve tribes to the twelve signs of the zodiac, or the comparison of Yechezkel’s prophetic vision to the zodiac (matters discussed from pp. 61-164 and which constitute about half of the book), or any similar imagery (of which the rest of the book is compiled but would take a lot more than a quick sentence in a blog to describe), could be taken to advocate the concept that the Sages were infallible. In fact, the overwhelming majority of SOTS has nothing to do with contemporary science. Rather, it explains how the astrological imagery and symbolism of earlier generations allows a better understanding of these writings.

I am not certain, but it seems to me, that Mr. Zinberg assumed that I had some other agenda and he proceeded to attack what he feels is an alarming trend. It appears that he stereotyped me in some way or another. Perhaps this was because my work deals with astrology, or maybe because my publisher was located in Lakewood. It is also possible that as a self-proclaimed “rational person of the twenty-first century” it is his desire to “gladly consign astrology to its rightful place next to alchemy, magic, divination, and other medieval fallacies.” Nevertheless, it seems this bias forced him to read into SOTS an entire perspective that does not exist. Any objective reader of SOTS will notice that the concerns Mr. Zinberg has with SOTS are actually concerns he has with the approach of the sages in our history that believed in astrology. Whether one rejects astrology in today’s day and age or whether he embraces it is his choice, however, censorship of early works or of attempts to explain them, would be tragic as it would undoubtedly be the cause of hundreds of years of rabbinic thought relegated to misunderstandings and misinterpretation.

Prior to responding to the recent critique by David S. Zinberg of my work, The Secrets of the Stars, let me thank Rabbi Slifkin for graciously allowing me to respond on his blog. A careful reading of Mr. Zinberg’s review allows the reader to recognize that he is not criticizing my work inasmuch as he is instead criticizing the use of astrology by many sages. The issues raised with my work such as determinism, are actually concerns non-specific to my work.

My work, herein called SOTS, was intended to give the reader a clearer perspective of the thought processes of many of our sages. It is irrefutable that many great rabbinic authorities, although not all, were firm believers in astrology. While one may simply ignore these statements on the basis that they are “pseudoscience”, those who choose to actually learn from these statements to glean further understanding of Torah would benefit from a knowledge of the outlook and of the mindset of that day. Whether or not astrological beliefs should be rejected or adhered in today’s day and age is completely irrelevant to this discussion. In my work I attempt to build a framework to understand works containing astrological references such as: Midrash Rabbah, Tanchuma, Pesikta Zutresa, Midrash Hagadol, Baraisa D’Mazalos, the Talmud, and many others; similarly, of the later sages: Rashi, Tosefos, Ramban, Rashba, Rabbeinu Bacheye, Rokeach, Recanati, R. Yosef Gikatilla, R. Avraham ibn Ezra, R. Avraham ibn Chiya, Tur, R. Yosef Karo, Rema, and others.

While Mr. Zinberg as dissatisfied with how I address the conflict between determinism and freewill, he ignores that this is not my own conclusion, but rather that of earlier Torah giants who believed in astrology. Mr. Zinberg seems to have ignored that I directly cited from the Ibn Ezra when discussing this matter. As for future predictions, Chazal (Sukkah 29a) make the statement that eclipses are predictions of ominous events, yet, even in their era eclipses were predictable via the Saros Cycle. They understood that throughout history, the world was predisposed to certain occurrences, but that has no bearing on how a person chooses to act. Just because a hurricane will inevitably hit does not take away one’s freewill. Thus, my very isolated statement with regards to the events of six-hundred years were an assessment of the predisposition of the world as based on the imagery utilized by the sages who believed in astrology. I have never suggested nor attempted to calculate when the messiah will arrive. In fact, I am a firm believer that the practice of doing so is frowned upon by our Sages as seen in Sanhedrin 97b. (The reader should not think that there were no authorities who have attempted to predict these matters, though. In his Megilas Hamegaleh, R. Avraham ibn Chiya did, in fact, estimate the date of the messiah via astrological reasoning. This date was then repeated by Ramban and others. Alas, the projected date has come and gone.) Furthermore, this is an isolated comment and the book in its entirety does not address future events, rather, it focuses on the perspective of the many sages’ view of the natural world as it pertains to the celestial realm.

Mr. Zinberg harshly criticized the exclusion of Rambam’s opinion in SOTS. Any student of medieval rabbinic literature is well aware of Rambam’s staunch opposition to the acceptance of astrology. Rambam made that clear in the eleventh chapter of hilchos avodas kochavim of his Mishneh Torah where he expresses an extremely derisive view of astrology as well as in Moreh Nevuchim, Peirush Hamishnayos, his letter to Montpelier (Marseilles), and other works. However, SOTS was never intended to be a comprehensive compilation of Jewish thought regarding astrology. As such, there was no need to cite Rambam or mention his ardent opposition. The exclusion of his opinion was purely because it had no relevance. The purpose of SOTS was to allow one to understand many of those otherwise confounding statements of Chazal, as most of modern day man is not proficient in medieval astronomy or astrology. My goal was to provide the perspective of those sages that did espouse these beliefs and allow one to recognize how these sages saw beauty and significance in this world. Furthermore, throughout much of our history, our Torah writings are replete with these colorful astrological/astronomical references, and neglecting them by simply writing them off as archaic would tragically erase much of their message. One can understand these statements regardless of whether or not he believes astrology to be a valid science.

But to address Mr. Zinberg’s point, in a previously published work, Tiferes Aryeh: Kuntras Hatemimus, I addressed the rabbinic dispute of astrology more comprehensively and detailed Rambam’s approach there. I concluded that, philosophically, one is free to believe or reject astrology. (Although I feel the need to note that practicing forms of astrology is certainly prohibited and one should consult a competent rabbi prior to engaging in this practice. This is even if one feels that these practices are silly and baseless.) My personal positions on the validity of astrology are neither addressed in this earlier work nor in SOTS.

Mr. Zinberg mentions my creativity and provides an example that is intended to show how I have taken quite the literary license and is, in his words, “bizarre.” Although I do believe I have a creative side, it probably would have been best for Mr. Zinberg to have reread that passage prior to mentioning the association of the tribe of Judah to Cancer, the crab. This association was not one fabricated or concocted by me, rather, it is, in fact, mentioned by the Pesikta Zutresa which is clearly footnoted in the text itself. The Pesikta Zutresa mentions that the twelve tribes are associated with the signs of the zodiac and that the tribes are aligned to the months based on the order of their birth. As such, Judah, the fourth son, is associated with the month of Tammuz and the sign of Cancer. I am merely attempting to show the reader how this Midrash understood these associations.

Another concern of Mr. Zinberg seems to be my understanding that much of Greek mythology parallels biblical narratives. I find it difficult for one to reject this assessment. There are numerous examples of both biblical and midrashic narratives bearing an extremely close resemblance to Greek mythology. The story of the twins of Gemini, Castor and Pollux, invading the kingdom of Attica to save their sister Helen who had been kidnapped by King Theseus bears a striking resemblance to the invasion of Shechem by the two brothers, Shimon and Levi, after their sister Dinah had been kidnapped by Prince Shechem. Procustes’ bed in which he would stretch the legs of short wayfarers and gruesomely amputate those of tall wayfarers is identical to the talmudic account (Sanhedrin 109b) of the ways in which the people of Sedom would act.

Mr. Zinberg attempts to marginalize the Ibn Ezra by painting him as controversial. Despite this attempt, anyone who has studied R. Avraham ibn Ezra’s writings knows that they are piercing, invaluable, and a testament to his great scholarship. Mr. Zinberg mentions that in some circles Ibn Ezra’s views are unpopular and this, no doubt, is an attempt to present me as one who unknowingly rests upon, what Mr. Zinberg feels to be, unstable shoulders. I am fully aware of the views he mentions and have even addressed them in a public forum. Those who are offended by citations of the Ibn Ezra will probably not be comfortable with SOTS (or a standard Mikraos Gedolos for that matter), but somehow I suspect that was not what Mr. Zinberg was getting at with those comments. Although I would have no problem relying solely upon the Ibn Ezra, he is but one of many sources cited in my work. I have not tallied how many times I have quoted specific sources, but I would venture to say that I quote Rabbeinu Bacheye just as frequently, in addition to many other Rishonim and Midrashim. The controversies surrounding Ibn Ezra’s writings are irrelevant to SOTS. Just as I did not mention that science has honored Ibn Ezra by naming a crater on the moon, Abenezra, for him; I did not mention the Ibn Ezra’s views with regards to post-Mosaic authorship. Although these are fascinating tidbits of information, they have no bearing on SOTS.

The attempt to discredit Ibn Ezra, and my usage of him as a source in my work, by citing Maharshal’s scathing critique of Ibn Ezra is at best disingenuous. Mr. Zinberg, very apologetically, rejects small portions of Rambam’s Mishneh Torah due to discrepancies between those writings and contemporary science (“To be fair, much of Maimonides’ cosmology, summarized in Basic Principles of the Torah, the very first section of the Mishneh Torah, is also obsolete ...”), but it seems clear that he has no problem adhering to the rest of Mishneh Torah. If Mr. Zinger defers to Maharshal’s opinion as to which books should be read and which should be censored, then he should wholeheartedly reject the adherence of any opinion espoused by Rambam in Mishnah Torah. Just a few lines prior to Mr. Zinberg’s citation of Maharshal’s criticism of Ibn Ezra, the Maharshal comments on Rambam’s Mishnah Torah, “Therefore, one cannot accept [Mishnah Torah] in an intellectually honest way because one never knows what is the true source [of Rambam’s halacha].” I have tremendous respect for Maharshal, but it would seem that most scholars have not adhered to these statements found in his introduction to Yam Shel Shlomo.

Mr. Zinberg states that my work is part of an increasing trend to prove that the Sages were infallible. Nowhere has Mr. Zinberg shown where this idea was gleaned from SOTS, nor is this concept even expressed in the work. I can only guess that he misunderstood two of my statements (in an over two-hundred page work) that express my amazement of how two interpretations of Chazal bear striking resemblance to scientific thought that had not yet been discovered at their time. Mind you, had these two statements of mine not been included in SOTS, the work would remain entirely intact, and yet, Mr. Zinberg attempts to discredit the entire book based upon them. Furthermore, he has grossly misinterpreted my words as I have NEVER stated in my work that Chazal were infallible. I have not addressed the topic of fallibility of the Sages in this work, or in any other public forum. This topic, albeit fascinating and a point of heated debate in recent years, has no place in my SOTS, as it is addresses an entirely different topic. Once again, the purpose of the work was to display the beauty of the world, specifically the celestial objects, as seen through the perspective of many of our great sages. It does not take a stance, nor does it project an opinion one way or another as to whether or not the Sages were able to err. I hardly see how the Sages’ comparison of the twelve tribes to the twelve signs of the zodiac, or the comparison of Yechezkel’s prophetic vision to the zodiac (matters discussed from pp. 61-164 and which constitute about half of the book), or any similar imagery (of which the rest of the book is compiled but would take a lot more than a quick sentence in a blog to describe), could be taken to advocate the concept that the Sages were infallible. In fact, the overwhelming majority of SOTS has nothing to do with contemporary science. Rather, it explains how the astrological imagery and symbolism of earlier generations allows a better understanding of these writings.

I am not certain, but it seems to me, that Mr. Zinberg assumed that I had some other agenda and he proceeded to attack what he feels is an alarming trend. It appears that he stereotyped me in some way or another. Perhaps this was because my work deals with astrology, or maybe because my publisher was located in Lakewood. It is also possible that as a self-proclaimed “rational person of the twenty-first century” it is his desire to “gladly consign astrology to its rightful place next to alchemy, magic, divination, and other medieval fallacies.” Nevertheless, it seems this bias forced him to read into SOTS an entire perspective that does not exist. Any objective reader of SOTS will notice that the concerns Mr. Zinberg has with SOTS are actually concerns he has with the approach of the sages in our history that believed in astrology. Whether one rejects astrology in today’s day and age or whether he embraces it is his choice, however, censorship of early works or of attempts to explain them, would be tragic as it would undoubtedly be the cause of hundreds of years of rabbinic thought relegated to misunderstandings and misinterpretation.

Published on April 24, 2012 20:22

April 23, 2012

Review of "The Secrets of the Stars"

Guest post by David S. Zinberg

Review of The Secrets of the Stars by Rabbi Ari Storch (Lakewood: Israel Bookshop Publications, 2011).

May a Jew believe in astrology? Most modern-leaning, traditional Jews would likely say no. Astrology has long been considered a pseudoscience, and we Jews have a proud tradition of scientific study and accomplishment which has flourished in parallel to our religious legacy. As rational twenty-first-century people, most of us would gladly consign astrology to its rightful place next to alchemy, magic, divination, and other medieval fallacies. Furthermore, from a moral and religious standpoint, we tend to regard free will as an axiom, and astrological determinism undermines the very foundation of human freedom and accountability. To posit a mechanism by which human behavior may be guided by the zodiac and the planets, acting as a sort of providential conduit between God and man – even if man is allowed to overcome that mechanism – is to diminish both man’s freedom and God’s omnipotence.

Yet references to astrology are found throughout the Talmud and the Midrash, and in the writings of great medieval Jewish thinkers. Abraham Ibn Ezra (c.1089-c.1161), for example, wrote several treatises on the subject and generously applied astrological theory in his biblical commentaries. Even Rashi (1040-1105), in his commentary on Exodus (quoting the Midrash), says that Pharaoh received advice from his astrologers on the day Moses was born and, before agreeing to release the Israelites, warned Moses of “a star that is a sign of blood and murder” awaiting them in the desert. So how can we reconcile the undeniable presence of astrology in Jewish texts with our modern conviction that it is nonsense?

There are three general approaches to this problem, particularly with respect to the literature of the Talmudic Sages. There is the historical approach, which places astrology and other discredited notions in the context of the ancient world in which the Talmud was formulated. Despite their greatness, the Sages repeated ideas – including many now known to be false – that were prevalent in the Near East in the first few centuries BCE and CE. They were simply operating within the intellectual climate of their day. The second approach is apologetic; its adherents insist that the Sages would not err, even in scientific matters. Therefore, we misunderstand what appear, only superficially, to be incorrect notions about the physical world. Such statements in the Talmud, according to this approach, must have an esoteric meaning representing a deeper metaphysical, rather than scientific, truth. The third, and most radical, response is fundamentalist. Talmudic fundamentalists reject the historical approach and do not feel compelled to rationalize the Sages’ statements. Much like biblical fundamentalists, they maintain that everything in the Talmud and Midrash, even from the realm of biology and the physical sciences, is literally accurate.

The Secrets of the Stars is a product of the fundamentalist approach to astrology in Judaism. It is based on the premise that astrology is a true science having the full support of Jewish tradition. The author does not argue this position; he takes it as a given, based on passages in the Talmud, Midrash, and medieval Jewish works sympathetic to his thesis. He does not acknowledge the disputes over astrology in both general and Jewish intellectual history, and includes only a passing reference to a debate in the Talmud itself about Israel’s subjection to astrological influence. To avoid being cast as a full-fledged determinist, or as a proponent of predictive astrology, the author attempts to hedge his astrological philosophy with the following disclaimer, in his Introduction: “Despite the power of the mazalos suggested in this work, it does not suggest pre-determined destiny. The Creator endowed man with free choice, a fundamental belief in Judaism . . . While this sefer points to the strong parallels between the events and figures of history and the constellations, never is a cause-and-effect relationship suggested. The argument that as mirror images one affects the other is easily countered. Hindsight is twenty-twenty, and it is only after the fact that one can decode the celestial secrets. The stars do not necessarily dictate the future, but history may be read from them.” This makes astrology sound like a purely subjective art form, valid only for past events. But, in fact, this is not the consistent message of the book. In a chapter entitled “Nearing Completion,” for example, the author predicts what will occur when the point of the vernal equinox on the celestial sphere enters the constellation Aquarius (this will indeed take place in approximately 600 years from now – the precise date depends on where you decide to draw Aquarius’ border – due to a real astronomical phenomenon called precession of the equinoxes). Identifying Aquarius as “the mazal of Yisrael,” Rabbi Storch states that this event “will undoubtedly infuse the year with a spirituality that only Klal Yisrael can bring, and ultimately with geulah, redemption.” (This discussion may recall a hit song from the late 1960’s on “the dawning of the Age of Aquarius”).

Rabbi Storch is an energetic advocate for astrology as an interpretive method for Judaism and has tapped into deep creative reserves to implement his program. He offers several novel parallels between the zodiac – which he considers divinely ordained – and a variety of themes, such as the Hebrew months, the twelve tribes, and Ezekiel’s vision of the heavenly chariot. But his unbridled creativity leads him down some strange and dangerous paths; he makes a rare proposal for a syncretism of Greek mythology and biblical narratives (though Rabbi Storch maintains that the Greek myths are merely corruptions of our own traditions). Thus, Hercules, who defeated Draco the Dragon, “represents the ideal man who overpowered his evil inclination, in contrast to the failure of Adam and Chavah.” And, “the centaur, a man-like creature with four legs . . . depicts this handicap – Noach’s inability to walk on his own two feet.” Occasionally, his ideas take a turn to the bizarre, such as when he links the tribe of Judah with Cancer, the crab. Adding to the famous midrashic tradition which has Nachshon ben Aminadav jumping into the Red Sea before it parted, Rabbi Storch says that Nachshon “quite literally took on the persona of the crab . . . He was not bound by perceived boundaries.”

Not surprisingly, Rabbi Storch finds a kindred spirit in Ibn Ezra. Describing him only as a “great Torah scholar,” Rabbi Storch cites Ibn Ezra’s astrological works numerous times throughout the book. He fails to mention, however, that Ibn Ezra was a highly controversial figure, in his own lifetime and for centuries following his death. Today, in fact, many of his opinions – unrelated to astrology – are considered heretical in some Orthodox circles. Ibn Ezra often rejected midrashic exegesis on the narrative portions of the Bible, preferring his own brand of natural (peshat) interpretation. He was a harsh critic of Rashi for being inclined towards midrashic commentary. Ibn Ezra pointed to verses in the Torah which could not have been written by Moses and believed that the latter half of Isaiah (from chapter forty) was written by an anonymous prophet who lived at the end of the Babylonian Exile. The great Polish Talmudist, Rabbi Solomon Luria (known as Maharshal, 1510-1574), wrote scathingly of Ibn Ezra, “he did not master the Talmud . . . he frequently criticized great Torah scholars . . . we do not follow his commentaries . . . for he opposed Halakhah on many occasions, and even came out against the Sages of the Mishnah and Talmud . . . I believe he has already been punished, since he has lent support to heretics and disbelievers.” Ibn Ezra is hardly a mainstream figure within rabbinic Judaism, and one wonders whether Rabbi Storch has thought through the implications of standing on the shoulders of this particular giant.

While Rabbi Storch champions Ibn Ezra’s astrology, he conspicuously neglects Maimonides. Maimonides stated his objections to astrology explicitly and repeatedly within his halakhic and philosophical writings. Incredibly, though consistent with its fundamentalist approach, there is not a single reference to Maimonides’ rejection of astrology in this book. Responding to an inquiry on astrology from the Rabbis of Provence, Maimonides wrote: “Know, my masters, that every one of those things concerning judicial astrology that (its adherents) maintain – namely, that something will happen one way and not another, and that the constellation under which one is born will draw him on so that he will be of such and such a kind and so that something will happen to him one way and not another – all those assertions are far from being scientific; they are stupidity.” Because it is false, Maimonides insisted, the Torah prohibited astrology as it prohibited other forms of idolatry. Referring to the Bible’s list of idolatrous practices, including astrology (me’onen of Deut. 18:10), Maimonides wrote in his Mishneh Torah, Laws Concerning Idolatry (11:16): “Whoever believes in these and similar things and, in his heart, holds them to be true and scientific and only forbidden by the Torah, is nothing but a fool . . .” In the Laws of Repentance (5:4), he argued that the fatalism of the “foolish astrologers” is contradictory to all moral and religious law. To be fair, much of Maimonides’ cosmology, summarized in Basic Principles of the Torah, the very first section of the Mishneh Torah, is also obsolete (e.g., the four-element theory and the idea that the celestial orbs are intelligent). But like the Sages, Maimonides could only work with the best science of his day. His rejection of astrology, unique within medieval Jewish thought, remains on target from the perspective of modern, traditional Judaism.

The Secrets of the Stars draws mostly from post-biblical sources or, more precisely, from a carefully selected sample of sources. To gain a wider perspective on the issue, it is helpful to take a step back from the period of the Sages, when Hellenistic astrology was pervasive in the Near East, and return to the Bible. As part of its unrelenting campaign against paganism, the Bible sharply condemns astrology. The Torah and the Prophets repeatedly contrast Israel, who is told to place her faith directly in God, with her neighbors, who divine their future from the stars. Thus, Deuteronomy (18:13-14): “You must be wholehearted with the Lord your God. Those nations that you are about to dispossess indeed resort to soothsayers and augurs; to you, however, the Lord your God has not assigned the like”; Isaiah (47:13): “You are helpless, despite all your art. Let them stand up and help you now, the scanners of the heavens, the star-gazers, who announce, month by month, whatever will come upon you”; Jeremiah (10:2): “Thus said the Lord: Do not learn to go the way of the nations, and do not be dismayed by portents in the sky; let the nations be dismayed by them!”

Just as Judaism as a whole evolved considerably since biblical times, the Bible did not have the last word on astrology. However, we need not be overly embarrassed by astrology or by other false scientific beliefs in the Talmud; after all, they represent the Sages’ best attempt at engagement with general culture. On the other hand, we must not embrace these statements as the truth simply because they are in the Talmud.

Viewed in its larger ideological context, Secrets of the Stars represents an alarming tendency within recent Orthodox thought to make the Sages infallible, even on matters of nature and science. But an attempt to bolster tradition by assigning quasi-divine status to the Sages is a desperate measure that is ultimately destined to fail. On a practical level, by adding unnecessary layers of superstition to our religion, we risk alienating a critically important segment of Jewish society that would like to come closer to Jewish tradition, but will be repelled by a theology so obviously out of touch with reality.

Hopefully, Secrets of the Stars will generate further discussion about the interaction of Jewish thought and law, today and in the past, with both good and bad science. That discussion deserves a much deeper and more balanced treatment than is found within its pages.

Review of The Secrets of the Stars by Rabbi Ari Storch (Lakewood: Israel Bookshop Publications, 2011).

May a Jew believe in astrology? Most modern-leaning, traditional Jews would likely say no. Astrology has long been considered a pseudoscience, and we Jews have a proud tradition of scientific study and accomplishment which has flourished in parallel to our religious legacy. As rational twenty-first-century people, most of us would gladly consign astrology to its rightful place next to alchemy, magic, divination, and other medieval fallacies. Furthermore, from a moral and religious standpoint, we tend to regard free will as an axiom, and astrological determinism undermines the very foundation of human freedom and accountability. To posit a mechanism by which human behavior may be guided by the zodiac and the planets, acting as a sort of providential conduit between God and man – even if man is allowed to overcome that mechanism – is to diminish both man’s freedom and God’s omnipotence.

Yet references to astrology are found throughout the Talmud and the Midrash, and in the writings of great medieval Jewish thinkers. Abraham Ibn Ezra (c.1089-c.1161), for example, wrote several treatises on the subject and generously applied astrological theory in his biblical commentaries. Even Rashi (1040-1105), in his commentary on Exodus (quoting the Midrash), says that Pharaoh received advice from his astrologers on the day Moses was born and, before agreeing to release the Israelites, warned Moses of “a star that is a sign of blood and murder” awaiting them in the desert. So how can we reconcile the undeniable presence of astrology in Jewish texts with our modern conviction that it is nonsense?

There are three general approaches to this problem, particularly with respect to the literature of the Talmudic Sages. There is the historical approach, which places astrology and other discredited notions in the context of the ancient world in which the Talmud was formulated. Despite their greatness, the Sages repeated ideas – including many now known to be false – that were prevalent in the Near East in the first few centuries BCE and CE. They were simply operating within the intellectual climate of their day. The second approach is apologetic; its adherents insist that the Sages would not err, even in scientific matters. Therefore, we misunderstand what appear, only superficially, to be incorrect notions about the physical world. Such statements in the Talmud, according to this approach, must have an esoteric meaning representing a deeper metaphysical, rather than scientific, truth. The third, and most radical, response is fundamentalist. Talmudic fundamentalists reject the historical approach and do not feel compelled to rationalize the Sages’ statements. Much like biblical fundamentalists, they maintain that everything in the Talmud and Midrash, even from the realm of biology and the physical sciences, is literally accurate.