Bodhipaksa's Blog, page 72

June 19, 2012

Violent Buddhists and the “No True Scotsman” fallacy

I recently had a conversation on Google+ (it’s a social network that’s — in my opinion — a much better alternative to Facebook) about Buddhist violence in Burma. Following the alleged rape of a Buddhist woman in Burma by members of that country’s Muslim minority, there was an outbreak of violence in which 2,600 homes were torched and at least 29 people died.

I recently had a conversation on Google+ (it’s a social network that’s — in my opinion — a much better alternative to Facebook) about Buddhist violence in Burma. Following the alleged rape of a Buddhist woman in Burma by members of that country’s Muslim minority, there was an outbreak of violence in which 2,600 homes were torched and at least 29 people died.

I condemned this violence unequivocally. There is no justification in the Buddhist scriptures for violence. There is no Buddhist doctrine of “just war” or even of “righteous anger.” The Buddha condemned all forms of violence, and famously said that even if bandits were sawing you limb from limb, you should have compassion for your torturers. In fact he said that anyone who had any anger in such a situation would not be one of his followers.

Now that seems kind of crazy, because every single Buddhist experiences anger. I know I do. Does that mean that the Buddha has no followers? I don’t think so. I think what the Buddha meant was that in the moment of being angry you are not following his teachings. In the moment of being angry we are not pursuing the path of mindfulness and compassion.

But back to that discussion on Google+.

The original thread I was commenting on was started by an atheist, and she had a number of atheist followers who chimed in, citing the violence as evidence that Buddhism is a bad thing (“full of shit”) was one phrase used. I had a feeling that there was a generalized disdain of religion which was being uncritically extended to Buddhism.

Check out Bodhipaksa's meditation CDs and MP3s

But in what way does it make sense to criticize Buddhism itself because of the behavior of people who call themselves Buddhists? If Buddhism (i.e. the Buddha’s teachings) said “violence is wrong unless…” then, sure, I’d accept the premise that Buddhism is full of shit. But it doesn’t. The Buddha was completely uncompromising on the question of violence. When people are violent they’re not following the Buddha’s teachings.I articulated the point above, and was accused of employing the “No True Scotsman” fallacy. In case you’re unaware of this fallacy, it runs like this:

McTavish says, “No Scotsman would refuse to help an old lady crossing the road.”

Smyth says, “I witnessed, just yesterday, a Scotsman who refused an old lady’s entreaties to help her cross a busy thoroughfare.”

MacTavish replies, “Ah, but he was no true Scotsman.”

What our dear friend McTavish is doing here is trying to justify an unsupportable generalization when challenged with examples contradicting it. [Full disclosure: I am a True Scotsman.]

So, what does that mean in terms of Buddhists who are violent? Well, given that I would never make a generalization of the type “No Buddhists are violent” I don’t need to backtrack as McTavish did. My statement (and the Buddha’s) is more akin to a definition: “The Buddha’s teaching is to practice nonviolence. When someone is violent, they are not practicing the Buddha’s teaching.

So if I said “Scientists do not falsify results” that could be challenged by someone pointing to examples of scientists falsifying results. I could then fall back on the “No True Scotsman” fallacy by arguing that those cheating scientists are “not true scientists.” I’m attempting (using a fallacious argument) to justify a false generalization.

Now if I say that scientists who falsify results are not doing science, there’s no fallacy involved. I haven’t made a false generalization that I am trying to defend. I’ve made a fairly precise statement about what science does and does not consist of.

Similarly, people who are acting violently are not “doing Buddhism. The Buddha’s teachings provide no “excuses” for violence — not even the “he did it first” or the “I was just defending myself” types of excuses.? There’s no use of the “No True Scotman” fallacy here — just a clear definition.

Now if only we could remember, as Buddhists, that when we express hatred we cease, at least for a while, to be Buddhists.

June 17, 2012

Not knowing how near the Truth is, people seek it far away

Some years ago I noticed an odd thing; a lot of the Buddhists I knew (including myself) didn’t talk much about getting enlightened. We didn’t talk much about what, specifically, we were doing in order to get enlightened. We didn’t talk much about what enlightenment was. And this was not just my impression. I asked other people whether this was what was going on, and they all agreed: enlightenment was not on our radar. And this is very odd, since the only reason that Buddhism exists is to help get us enlightened. The Dharma is nothing but the Way to enlightenment. And it seemed few of us were interested in going all the Way. So what were we interested in?

Some years ago I noticed an odd thing; a lot of the Buddhists I knew (including myself) didn’t talk much about getting enlightened. We didn’t talk much about what, specifically, we were doing in order to get enlightened. We didn’t talk much about what enlightenment was. And this was not just my impression. I asked other people whether this was what was going on, and they all agreed: enlightenment was not on our radar. And this is very odd, since the only reason that Buddhism exists is to help get us enlightened. The Dharma is nothing but the Way to enlightenment. And it seemed few of us were interested in going all the Way. So what were we interested in?

When think about what we’re doing in our Buddhist practice, we often think in worldly terms. We think about becoming a better person, about being kinder and more content. We think about how the Dharma can help us with specific problems we have. We think about being happier. These are all very good aims, and I’m not going to knock them. But Buddhism’s about much more than becoming more positive. It’s about transforming, on a very deep level, the way we see the world.

So I made it a project to be more concerned with enlightenment and how to get there. I made a point to make this concern more central in my life, to reflect on what enlightenment means, and what I should be doing to get there. And that brings us on to insight meditation, or vipassana. Vipassana is the next step beyond being more positive, which is a samatha activity. Vipassana is the practice of looking closely at your experience in order to recognize that everything constituting that experience is constantly changing. This what we call the “mark” or impermanence, or anicca. When we recognize the impermanence of our experiences, on deeper and deeper levels, this leads to us recognizing that there’s nothing in our experience worth grasping on to; after all, if our experiences are all constantly changing, then none of them can be the basis of lasting happiness. That’s the mark of unsatisfactoriness, or dukkha. And an awareness of impermanence, applied to ourselves, drums in the fact that there is no permanent self here to do any grasping. This is the mark of anatta, or not-self. These are the three marks. This is what vipassana is about. It’s about recognizing these three marks. It’s not just about intellectually understanding them, although some intellectual engagement is necessary, but about seeing their truth in our own experience.

Vipassana is an activity that we can do in any meditation practice. It’s not a special kind of meditation. So we can do it in the mindfulness of breathing practice, the metta bhavana, or just sitting. There are practices in which vipassana is more explicit, however, such as the six element practice, but this isn’t an exception. We could do the six element practice as a samatha (calming) practice, but as a matter of course we include insight reflections: “This is not me, this is not mine, I am not this.”

We can do vipassana reflections outside of meditation as well — when walking, taking the bus, having a conversation, cooking — although activities in which there’s some mental quiet are more conducive to this kind of reflection. And to reiterate an important point, vipassana is not opposed to samatha. What we’re meant to do is to calm and concentrate the mind, and then to take that calm, focused mind, and apply it to investigating the existential issues of the three marks. Samatha and vipasssana are like two wings, and we need both if we want to go the way to enlightenment.

Not knowing how near the Truth is, people seek it far away.

Now, how far away is enlightenment? We generally think of it as being very remote, which is perhaps why we don’t think about it very much. But as Hakuin said:

Not knowing how near the Truth is,

People seek it far away. What a pity!

I think there are a number of reasons why we think Enlightenment is far away, when it’s actually close by — right under our noses, or even closer than that.

Some of the perspectives of the Mah?y?na don’t help. In early days, when the Buddha’s feet were walking India’s dusty soil, people often got enlightened immediately. Many, many people seem to have had a radical shift of consciousness just upon hearing the Buddha speak for the first time. It just took a slight reorientation of the way they saw things, and bam! they were awakened. This didn’t happen to everybody, of course. Obviously some people had to practice for years. But many of them became awakened in this lifetime. Now the later Mah?y?na tradition, starting from about 500 years after the Buddha, were keen to build up the status of the Buddha. Presumably they were playing the game of “our teacher is the best.” So they built up the goal of Buddhism. Buddhists were now seeking enlightenment for the sake of all sentient beings, not just in our world but throughout the entire universe. And achieving this task would take countless lifetimes. Countless lifetimes, needless to say, is a long time. Elevating the status of the Buddha and of enlightenment in this way may have been very inspiring, but it also made the goal seem very remote. And those ideas still linger and influence us.

It’s interesting to note that although many contemporary schools call themselves Mah?y?na, few if any of them still emphasize these cosmic timescales. The Zen schools focus on awakening right here, right now. The Theravadin schools emphasize awakening in this life. The Pure Land schools are slightly different, because they emphasize awakening after death: we die and, through the grace of Amida Buddha, we are reborn in his Pure Land paradise, Sukh?vati, where we are assured enlightenment. So even there we’re aiming for enlightenment just after this very lifetime — not countless lifetimes from now. The Tibetan schools, or at least most of them, emphasize the possibility of awakening in this life. I think we need to embrace the notion of enlightenment in this lifetime, and not be overly swayed by this Mah?y?na perspective.

Another reason we think of enlightenment as being far away is because of a lack of self-worth. We think we have so many problems. We’re unworthy! We’re often very aware of our flaws. And then what do we not know about ourselves? Freud gave us this idea what there’s all this nastiness under the surface. I remember a scene from the comedy movie The Front Page where a Viennese Freudian psychoanalyst asks a condemned murderer about his childhood. The murderer replies that he had a perfectly normal childhood, to which the shrink replies, “I see. You wanted to kill your father and sleep with your mother.” So this is quite literally what Freud thought a “normal” person was like — a incestuous parricide kept in check by the super-ego. We’ve been affected by these ideas and we fear that there is unknown emotional baggage holding us back from enlightenment.

And I think we fear enlightenment. Being fully enlightened would surely involve a big change. What would it be like? Would I be a different person? Would I still have my life. What about all my likes and dislikes? We like our attachments! We fear that there might in fact be so much change that enlightenment would be a kind of death. So this is scary. We might fear that we’re going to lose ourselves, and our individuality. I remember having this thought once, that if Buddhas are all perfect, then are they all the same? They’re clearly not, but we can fear that our personalities are going to be erased.

The models and language we use — even very traditional language and models — can be unhelpful. The Buddhist tradition has tended to talk in terms of exalted states of consciousness. We think of the jh?nas. There are these four jh?nas, and most of us have only limited experience of these. And then the commentaries take another set of four meditative states — the formless spheres, or ay?tanas, and pile them on top of the jh?nas. So there’s now this towering skyscraper that we might thing of as ever-more blissful states of consciousness, disappearing up into the sky. And we might think of enlightenment as being piled on top of all that. And here we are on the ground, or maybe, if we’re lucky, on the first floor from time to time. If even the jh?nas are hard to get into, then enlightenment must be quite literally unattainable for us!

But this way of looking at enlightenment is inaccurate. Enlightenment is not a meditative state similar to the jh?nas. It’s a way of looking at the world. We need some jh?nic experience to prepare ourselves for having a breakthrough into insight, but we don’t need to have experienced all of the jh?nas to have insight, and we don’t go through all the jh?nas and find enlightenment awaiting us at the top. Enlightenment is more likely to happen at a time of crisis, or during a conversation, than during meditation. Many people, according to the P?li scriptures, got enlightened when they were depressed and suicidal, or when they heard a teaching and had a “holy crap!” moment.

Another aspect of language that can mislead is when we talk about the “path” from sa?s?ra to Nirv??a. There’s nothing inherently wrong with this language, but we often take it too literally and slip into thinking that sa?s?ra and Nirv??a are almost literally like separate places, geographically isolated from each other. We think of the path as disappearing somewhere over the horizon, vanishing goodness-knows where. And then we think that this isn’t the place, this is not the life, in which we’re going to get enlightened. We may think that on some level we have to move away from this life in order to get to this “place” called enlightenment.

But sa?s?ra and Nirv??a are not separate places. They’re not even places — they’re states of mind. The way to nirv?na is by looking closely at your sams?ric mind. It’s not by getting away from where you are now, but by totally being where you are and getting to know that place intimately. We need to look at how we structure our experience into self and other. We need to question our assumptions and come to see how we misinterpret your experience. We need to look at things we think are permanent and come to see them as they are. We need to look at things we think are sources of lasting happiness and realize that actually they aren’t, and can’t be, sources of lasting happiness. We need to look at what we take to be a permanent and substantial self and to see that there’s no self like that to be found.

This is the place where we get enlightened. Awakening is just a shift in perspective away. So I suggest adopting the perspective that awakening is not far, but is right here. And when you make that shift in perspective, one of the first things that’s going to strike you is, “Why did it take me so long to see something so obvious?”

June 11, 2012

Search Inside Yourself, by Chade-Meng Tan

The cover of Search Inside Yourself is a clever riff on Google’s famous multicolored logo, and this is appropriate given that the author is a long-term Google employee and that the material is based on a course developed for Google’s staff.

Meng, as he is called, is a long-term meditator. Quite how long I’m not sure, but he refers to meditating before he joined Google (which was in 1999). Google’s workers are allowed to spend 20% of their time on personal projects, and so Meng and some of his colleagues spent that time developing a personal-development course which had meditation and mindfulness at its core.The course was jokingly called Search Inside Yourself, and the name stuck. This book is the result. SIY (the course) has been taught at Google since 2007, and has been taken by hundreds of people.

Search Inside Yourself is in some ways an odd book, no doubt because it’s written by an eccentric person. Meng seems irrepressibly jokey. (His Google business card describes his job title as “Jolly Good Fellow.”) The book is peppered with goofy cartoons and constant quips. At times these provoked chuckles, but mostly I found it all a little wearying. Quite literally I found my energy to be drained by Meng’s jokes, which I think is to do with the jokes taking my attention away from Meng’s more serious points, and thus requiring me to have to re-engage. I’ve had a similar sense of weariness overcome me at times when talking with people who can’t stop joking.

Title: Search Inside Yourself: The Unexpected Path to Achieving Success, Happiness (and World Peace)

Author: Chade-Meng Tan

Publisher: HarperOne

ISBN: 978-0-06-211692-5

Available from: Amazon.co.uk, UK Kindle store, Amazon.com, US Kindle Store, IndieBound.

Which is not to say that the book is not valuable — in many ways it is, and I’ll come to that shortly. But at one point I almost put the book down for good. One of Meng’s traits is constant name-dropping and a lack of modesty that some might find refreshing but which to me is distasteful. Here is the point at while I nearly abandoned my reading:

[E]ven though I am very shy, I find myself able to project a quiet but unmistakable self-confidence, whether I am meeting world leaders like Barack Obama, speaking to a large audience, or dealing with a traffic police officer. I watched the video of myself speaking at the United Nations, and I was amazed how confident I appeared.

In the very next paragraph Meng mentions “interacting” with Natalie Portman and Bill Clinton. It was several days after reading that particular passage before I could persuade myself to pick up SIY again.

What kind of book is this? It’s a guide to achieving success and happiness, according to the subtitle. Inside we learn that we do this by developing greater emotional intelligence. It’s therefore not just a meditation book. Meditation here is just one tool to develop emotional intelligence. As the book went on I became increasingly enthusiastic and interested in Meng’s approach. The later material is more connected with empathy, lovingkindness, and compassion, which is for me inherently more interesting than the earlier material on mindfulness.

Who is the book aimed at? At times it seems that the target market consists of managers and CEOs, and often it’s reminiscent of Stephen Covey’s “The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People.” There’s nothing wrong with that, of course — and in fact Covey’s book had a big influence on me. But some may find the recurring references to the corporate world a little off-putting if that’s not part of their experience.

I present what I didn’t like first, because my experience of reading the book was of being tripped up on the way to reading about an interesting program of personal development. And there is a lot of useful material in the book, and Meng has a number of strengths as a guide.

One strength Meng has is that he is an engineer and likes to know what works and what’s the science behind what works. And so there’s a lot of scientific backing for the meditative methods he outlines. For a meditation geek like me this was a delight. He’s also keen on taking systems to pieces and putting the back together again. So he breaks down the skills of mindfulness, empathy, compassionate communication, motivation, etc., and presents them very clearly.

I found myself looking forward to the gray boxes that contained the actual exercises. These were very stimulating and sometimes suggested exercises that I’d never thought of, such as the “meditation circuit training” on page 73. There’s an exercise on dealing with memories of “success” and “failure” (pp. 149–151) that’s similar to exercises I’ve taught in dealing with painful memories generally, but never with regard to that particular topic. His lovingkindness meditation (pp. 169–170) is very brief, and very familiar, but laid out in a very clear and concise way.

(As an aside, talking of familiarity, Meng uses a diagram on page 36 of his book that’s almost identical to one I devised for my own teaching twenty years ago, and use on this site. He referenced this to researcher Philippe Goldin, who used the diagram in a lecture he gave at Google, and I’m intrigued to know whether Goldin read my book, saw this site, or maybe happened to come up with the same schema independently.)

Another of Meng’s strengths is that he is not shackled to a particular ideology. The very common, almost standard, mindfulness-based stress reduction model, for example, that tends to downplay lovingkindness and compassion meditation (although it integrates those qualities into the meditation it teaches). Meng is prepared to take whatever works and to go with it. And so his approach is refreshingly varied and creative, including mindfulness, compassion, tonglen, communication exercises, etc.

One of the other things I admire about Meng is that he is a big thinker. In discussing motivation and “higher purpose” he says,

If you find yourself inspired by your ideal future, I highly recommend talking about it a lot to other people. There are two important benefits. First, the more you talk about it, the more real it becomes to you … The second important benefit is the more you talk to people about your ideal future, the more likely you can find people to help you.

This is something practical I’ll certainly take away from Meng’s book, and for that teaching alone I felt deep gratitude for having spent time with his writings. I realized how much I keep my vision to myself, as I work on from day to day trying to bring the benefits of meditation to more people. How sad! And how limiting! I’ll be spending more time reflecting on this.

The conclusion to SIY is in fact an outline of how Meng plans to make meditation accessible to the world. He wants to get to the point where everybody knows as a matter of course that meditation is good for them (just as they know that exercise is good for them), where everyone who wants to meditate can find a way to learn it, where companies value meditation and encourage their employees to do it, and where, in short, meditation is taken for granted. Or as Meng says, people will get to the point where they think, “Of course you should meditate, duh.”

SIY (both the course and the book) is part of Meng’s strategy for achieving these goals. He wants to make the SIY course “open source,” and to “give it away as one of Google’s gifts to the world,” although it’s not clear what he means by this. The book itself is not free. Even the Google Books preview limits how many pages can be read, which is rather ironic. And given that the book is under traditional copyright, it’s not strictly legal for people to copy and possibly even teach verbatim the exercises in it without permission. I wonder if Meng could have published the book under a Creative Commons license rather than traditional copyright, making the material freely available on a non-commercial basis, so encouraging others to spread the word?

Still, I wish Meng well. He’s a crazy dreamer, but when has anyone but a crazy dreamer ever pulled off anything big?

June 2, 2012

Fake Buddha Quote: “If we could see the miracle of a single flower clearly, our whole life would change.”

Thanks to Viv for bringing this one to my attention in a comment on another Fake Buddha Quote.

If we could see the miracle of a single flower clearly, our whole life would change.

It’s from page 112 of Jack Kornfield’s “Buddha’s Little Instruction Book,” in which Jack “distilled and adapted an ancient teaching for the needs of contemporary life.” This is a common pattern: if a book is called “The Teaching of Buddha” or “Buddha’s Little Instruction Book” then people jump to the conclusion that any quote from it is the teaching of the Buddha or one of the Buddha’s instructions. It’s not the fault of the author, of course…

As I said to Viv, how I can tell (usually) that a quote is a Fake Buddha Quote is that it may resonate with the teachings, but the language and idiom is all to heck.

The Buddha, to the best of my recollection, didn’t talk in terms of miracles in this metaphorical way (although he talked about literal miracles, such as psychic powers). And he was more inclined to talk about paying attention to the five clinging aggregates and recognizing that they were anatta — not your self — than paying attention to flowers.

He used flower metaphors, but I don’t think he ever suggested looking at flowers (or at least it’s not recorded that he did, which is all that’s important when you’re talking about quotes).

The language in this quote is more like something Thich Nhat Hanh would say. It’s nice, but it’s too sentimental for the Pali canon.

Related posts:

Fake Buddha Quote: “When words are both true and kind, they can change our world.”

“Thousands of candles can be lighted from a single candle, and the life of the single candle will not be shortened.”

Fake Buddha Quote: A generous heart, kind speech, and a life of service and compassion are the things that renew humanity.

May 29, 2012

Fake Buddha Quote: “The secret of health for both mind and body is not to mourn for the past, worry about the future, or anticipate troubles, but to live in the present moment wisely and earnestly.”

This is one I came across on Google+ last night, and it immediately struck me as suspect:

“The secret of health for both mind and body is not to mourn for the past, worry about the future, or anticipate troubles, but to live in the present moment wisely and earnestly.”

You’ll find this on ThinkExist and a whole bunch of other quotes sites.

It’s another quote that’s been taken from a translation of a Japanese book called “The Teaching of Buddha,” by the Bukkyõ Dendõ Kyõkai organization. It’s a Buddhist version of the Gideon Bible, and is put in hotel rooms in order to spread the word. The quote is from a passage interpreting the Buddha’s teaching and not quoting him. What I’d imagine happens is that the quote gets posted with the attribution “The Teaching of Buddha” and then someone thinks the quote is, verbatim, the teaching of the Buddha. And then it’s attributed as being the word of the Buddha.

There are things that the Buddha said that are along these lines, about not clinging to the past, future, or present. And he did sometimes talk about health. But I’m pretty sure he never bundled all these elements together into one neat quote. The phrasing is just not right for this to be something from the Pali canon…

Related posts:

Back to the Present: How to Live in the Moment

Taking care of the present moment

Fake Buddha Quote of the Day

Awakening to our true nature

Spiritual practice is about coming back, over and over again, to love and mindfulness, making those our home.

Spiritual practice is about coming back, over and over again, to love and mindfulness, making those our home.

I subscribe to the newsletters of Rick Hanson, who contributes articles to Wildmind and who is a well-known author and neuropsychologist. He’s a very stimulating man! Today’s newsletter was an interesting one, and it prompted some thinking on my part.

He opens by asking a much-pondered question about human nature: “Deep down, are we basically good or bad?” From a neurological point of view, he comes down firmly on the side of good.

His reasoning is this:

When the body is not disturbed by hunger, thirst, pain, or illness, and when the mind is not disturbed by threat, frustration, or rejection, then most people settle into their resting state, a sustainable equilibrium in which the body refuels and repairs itself and the mind feels peaceful, happy, and loving.

Basically, he’s talking about the sympathetic nervous system (responsible for “fight, flee, or freeze” responses to potential danger) and the parasympathetic nervous system (responsible for the “rest and digest” response that brings us back to balance when danger is past). Rick calls this “rest and digest” state the Responsive mode, and the “flight, flight, or freeze” state the Reactive mode.

Rick points out that the Responsive mode is our default state — a fundamental “strange attractor” in our brain states. And therefore, he says, it’s this relaxed and loving state that’s your true nature: “Your deepest nature is peace not hatred, happiness not greed, love not heartache, and wisdom not confusion.”

I don’t have any disagreement with this at all. What Rick is trying to do, I think, is to align neuroscience with certain Buddhist views of Buddha Nature which suggest that the mind is inherently pure and compassionate. Buddha Nature can be a useful way to see things as long as it’s not taken too seriously.

Check out Bodhipaksa's meditation CDs and MP3s

The thought I had, though, was that relaxation and rest, and even happiness and love, are not enough. It’s great to be free from stress — for a while. But then what happens if we stay relaxed? We start to seek out sources of excitement. We can’t handle too much peace! I don’t think that the resting state is actually a “sustainable equilibrium,” because rest and being “peaceful, happy, and loving” are not in themselves deeply satisfying enough for us. We always want something more. And the resting state is fragile because it’s always going to be challenged by events from our lives (a crazy day at the office, a child with a tantrum).The untrained mind in Responsive mode can never be loving enough, or peaceful enough to avoid being tipped over into reactivity. So we need to deepen our capacity for responsiveness. We need to train the mind, and not simply relax. I’m not disagreeing with Rick or criticizing him, incidentally, — just drawing out some of the implications of his presentation; Rick suggests a number of ways in his newsletter of how we can “tip forward into our deepest nature.”

Cultivating attentiveness, or mindfulness, changes the base state of our Responsive mode so that it’s less prone to reactivity. With mindfulness we notice quicker when the mind is starting to slip into reactivity. And this allows us to act. In a mindful state we learn to regulate the brain’s “fight or flight” module, the amygdala. In fact, with repeated training the amygdala — the part of the brain largely responsible for the Reactive mode — gets smaller, the parts of the brain responsible for regulating the amygdala get larger, and the number of connections from one to the other (allowing for this regulation) increase.

Deepening our lovingkindness by training in metta — as Buddhism calls the loving response that wants others to be happy — also helps us to go more deeply into Rick’s Responsive mode. Lovingkindness allows us to calm down the amygdala faster. The amygdala’s task is to scan our environment, looking for danger, and to alert us (via a flood of visceral feelings) when it’s detected a potential threat. Lovingkindness allows us to see people as beings who want to be happy rather than as beings who want to hurt us (and very few people want to hurt us). Rather than seeing someone’s anger, say, as a threat to our peace of mind, we refocus on their wellbeing; how can I help this person be happier? and we develop more lovingkindness and compassion for ourselves, as well. We take care of ourselves through compassion rather than through fear and anger.

These two practices, of mindfulness and lovingkindness, don’t fix thing instantly. But they help us bring ourselves back into the Responsive mode over and over again. And we do have to keep coming back, because our reactions to life’s events will keep propelling us into Reactive mode. That’s what training’s about; coming back over and over again to our purpose or living from a deeper level of fulfillment.

Lastly, a deep appreciation of change helps us to feel less threatened so that we can put the amygdala (perhaps, if this is what Awakening is really like) permanently offline, so that the Responsive mode becomes not just our default mode, but where we live, permanently.

May 22, 2012

Comical genitalia

The following post is contributed by Paul Duxbury, who blogs as “poetmcgonagall” (Left wing, atheist curmudgeon with a black sense of humour and a heart of gold. Love[s] music, books, theatre, tea, and marmite). He can also be found on Google+. Do circle Paul on G+ and visit his blog.

The following post is contributed by Paul Duxbury, who blogs as “poetmcgonagall” (Left wing, atheist curmudgeon with a black sense of humour and a heart of gold. Love[s] music, books, theatre, tea, and marmite). He can also be found on Google+. Do circle Paul on G+ and visit his blog.

“Comical Genitalia.” It’s not often you get a chance to use that phrase. I’m deeply grateful to an unsung staff reporter on the Sun for unleashing it on an unsuspecting world in this 2007 article, ‘Rude Buddha’ causes outrage. It was later lifted almost word for word in a Metro article – Cops probe Rude Buddha – a headline so brilliant you can forgive them the plagiarism.

The genitalia in question – a banana and two eggs – are welded onto a bog-standard statue of a seated Buddha. The work, by artist Colin Self, was probably considered rude by the good people of Norwich for a number of reasons. A banana and two eggs are surely innocent objects in themselves, but placed in the lap of a seated figure in an upstanding position, they acquire a whole new meaning. Then there’s the bronze colour of the foodstuffs, which stands out against the black of the Buddha. Finally, there’s the position of the hand curled in the lap – a classic meditation posture – suggesting an alternative activity is taking place. I’m reminded of a greeting card, with the picture of a seated mystic and the caption, “If that’s the sound of one hand clapping, I wonder what the other hand is doing?” Oh, and the statue was facing out into the street.

A Trilogy: The Iconoclasts is actually a witty spoof, melding ideas of sacred art with pop art, and evoking all the metaphorical associations of bananas and eggs. It’s a pity some people were so prudish as to complain to the police, forcing the gallery owner to turn it round so it faced into the shop. But I’d be surprised if it didn’t sell very quickly with all the free publicity. Perhaps Self got his friends to make the complaint.

So thanks to that staff reporter for adding an essential phrase to the English language – I hope it goes viral.

Dispute closes NKT’s Bexhill Buddhist centre

An extraordinary power struggle is tearing apart a Buddhist community in England.

An extraordinary power struggle is tearing apart a Buddhist community in England.

While scouring the headlines for stories that might fit on Wildmind’s blog under the “news” category, I came across the intriguing headline “Dispute closes Buddhist centre,” discussing problems at the Maitreya Buddhist Center of the New Kadampa Tradition, or NKT, in Bexhill in East Sussex.

Unfortunately both newspapers that carried the story had removed the article. But a friend came to the rescue by pointing me toward Google’s cache of the story, and someone on Facebook sent me a link to a blog which presents one side of the dispute (read the blog from the bottom up).

First, a bit of background. The NKT were founded by Geshe Kelsang Gyatso, and they’re one of the largest Buddhist movements in the UK. Probably in terms of the number of centers they have, they are the absolute largest, although some of the “centers” are no more than rooms rented for an evening class. They have a strong expansionist policy.

The NKT is also famous for the “Dorje Shugden Controversy,” which is, to my mind, a rather weird dispute about a Tibetan Deity. Dorje Shugden is a deity who has been worshipped in Tibetan Buddhism since the 1700s. However, the Fourteenth Dalai Lama came to the conclusion that Shugden is not an enlightened being but is a worldly figure, and he first spoke out against his worship and then issued a ban on the practice. Since Geshe Kelsang Gyatso is a firm believer in Shugden, this caused a bitter dispute between the NKT and the Dalai Lama. This puts the NKT in the unfortunate position of being opposed to one of the most popular and revered figures in the world.

This particular story, however, has nothing at all to do with the Dorje Shugden dispute, which is a phenomenon I find weird (it’s a dispute over a figure I consider to be purely imaginary). It seems to have to do more with tensions between an individual, and legally autonomous, local center of the NKT, and the central organization itself, to the point where the central NKT is attempting a takeover. Whether or not they have good reason to do that I don’t know, but it doesn’t seem that they have the legal right to do so, if indeed the local centers are constituted as independent charities with their own boards of trustees.

Bearing in mind that we only have one side of the story presented here, the Maitreya Buddhist Centre, which is a charity registered under English law and with its own board of trustees, ended up with a resident teacher, Kelsang Chodor, who made organizational decisions that were unpopular with the board. A teacher who was asked to stop teaching refused to do so, and when Chodor bypassed the trustees in some of his decision making he refused to meet with them. The newspaper article outlines the background and explains the build-up of the conflict:

A volunteer at the Maitreya Buddhist Centre claims “a traumatic and bitter dispute” has left this former haven of peace changed forever.

Now the building in Sea Road is locked with no sign of when it will be opened again.

Andrew Durling helped set up the meditation centre having been at the start of New Kadampa Tradition meditation classes in Bexhill.

He was one of the trustees when the charity was registered and was responsible for the oversight of administration.

The centre became established and thrived with up to 50 people a week attending regular meditation classes led by resident teacher Lam-ma and other teachers she appointed.

However since she retired there has been a breakdown in the relationship between NKT and the centre’s management team, and from there Andrew and others have struggled to reach agreement with the head office based in Cumbria.

One of the trustees claims that the central NKT tried to replace the board of trustees, which would seem to be an illegal course of action:

The Charity Commission has now replied to the submission made to it by the charity trustees of Maitreya Buddhist Centre many weeks ago. The key element of that reply was that the attempts by NKT head office back at the beginning of March to remove the existing trustees of the centre and to replace them with trustees of the NKT’s own choosing was invalid and a breach of the centre’s own constitution

As the newspaper article puts it, “This appears to have become a struggle for control between a handful of volunteers and the umbrella organization which has more than 1,000 branches throughout the country.”

The blog also alleges that the NKT made “repeated threats of litigation” against the center.

From an organizational point of view I find this fascinating, partly because the organization I’m part of (Triratna) is similarly constituted in such a way that individual centers are independent. But what’s difference we don’t have a “head office” that could attempt a takeover. The most that could happen if a center were, for example, to go off the rails,is that center could be told that they could no longer consider themselves to be affiliated with the parent organization. This actually happened once, with our Croydon center, where the Order member in charge of the situation there had created a kind of personality cult based on manipulation and bullying. He wasn’t the only person involved, because he had created a kind of “gang” that maintained control using the same techniques he himself employed. After attempts were made to correct the situation through dialogue, Sangharakshita, then founder of the Triratna Order, told the board of trustees that they would have to change their ways or cease being affiliated with the rest of the Triratna Community. And things did change as a result, with the ringleader leaving both the Croydon center and the Order.

The Bexhill situation is also interesting to me simply because it’s got to the point where a Buddhist center is no longer functional because of internal politics. That’s quite an extraordinary situation, and I’ve never head of that happening before. I’m not sensing a lot of dialog going on, which is unfortunate. Of course we don’t really know what’s going on. I’ve only seen one side of the story, and even if I was aware of both sides it would be impossible to be certain of the facts. Unfortunately, as the newspaper reports, “The head office was approached several times for a comment this week but none was forthcoming.”

The NKT has quite a traditional authoritarian structure (traditional for Tibetan Buddhism, anyway), where monks and nuns are basically told where to go and when. The NKT tries to be highly centralized, with the guru making decisions for the local centres, but the local centers are legally separate entities, and so ultimately the guru (or the central organization) has no legal control over them. That suggests a fragility in the NKT. Two ways to hold a local center in place when it has problems with the central organization are dialogue and authoritarianism. In this case the NKT seems to have adopted an authoritarian approach, through wielding power.

This following excerpt from the blog reveals a fascinating twist in how this power is being used:

A website purporting to be the official site of Maitreya Buddhist Centre, using the charity’s registration number and using its registered address, is currently active. However, this website is entirely without the sanction of the current legally valid trustees and management team of Maitreya Buddhist Centre, and is in direct conflict with the website that has always been the real official site of Maitreya Buddhist Centre, a site registered with the Charity Commission. This fraudulent website has therefore been reported to the relevant authorities, including the police and the Charity Commission.

Creating an alternative website for the center — one not controlled by the trustees — is an extreme step, or mis-step. It suggests that the NKT is struggling, within an authoritarian mind-set, to find ways to prevent one of its centers going its own way.

This tactic, of setting up an alternative website, is one I’ve seen the NKT use before, albeit in a different form. Several years ago, members of a Buddhist Center in England were surprised to discover that the NKT had set up a website using the name of their center, which was not in any way NKT affiliated. This was almost certainly a breach of trademark law as well as a breach of UK charity law. It was also rather unpleasant — a kind of spiritual “phishing” attempt. The situation was resolved through dialog between the two organizations.

Back in the Bexhill power struggle, the blog also describes a new management team being sent in to wrest control from the elected trustees:

It appears that Maitreya Buddhist Centre has now been ‘taken over’ and a new management team is attempting to take charge of the premises. This is as flagrant a violation of charity and company law as it is possible to achieve …

Certainly, if the board of trustees is properly constituted, then an outside entity has no legal standing to take over the center. Even the parent body — the NKT — can consider itself to be only the spiritual, rather than the legal, head of the center.

It seems that having opted for an authoritarian approach, the NKT is finding that it’s not a viable option.

I take no pleasure in reporting these events. The situation must be intensely painful for all concerned, and I truly hope that dialog and trust can be restored.

I wonder, however, whether dialogue is now even possible in Bexhill now that the authoritarian path has been chosen? Trust is more easily broken than restored.

This pain is evident both in the comments of Andrew Durling, one of the trustees, who has been at the epicenter of the conflict:

“Whoever ‘wins’ (so called) the situation will find there is nothing left. I am as guilty as anyone else.

“This bold experiment in bringing buddhist meditation to Bexhill has, temporarily at least, failed.”

He said the community had been irrevocably split, with some backing him and others supporting NKT, and added: “It is anyone’s guess whether it will be alright.”

It’s also evident in the comments of a woman who had been attending classes at the Maitreya Centre:

“They have taken my place of worship away from me. It isn’t a proper buddhist centre anymore.”

She added: “It is just awful.

“I won’t go back there, it’s a mess. I am really sad. I want to say – how dare you do this[?]”

As the Buddha said, “Spiritual friendship is the whole of the spiritual life.” It’s worth remembering that as we witness this painful conflict.

May 18, 2012

Keeping a level head while meditating

One thing I noticed a long time ago was that the position of my head during meditation made a surprising difference to my state of mind. If my chin was down even a fraction of an inch, then I’d tend to get tired, or to get caught up in often very heavy emotional story lines, full of drama. If my chin was up even a fraction of an inch, then I’d tend to get lost in thoughts that were generally more speculative and excited. Chin down focuses our energy on the emotions; chin up puts more energy into our thoughts. This is perhaps why when someone’s depressed we tell them to “keep their chin up” and when someone’s a dreamer we say they have their “head in the clouds.” Both of these metaphors convey essential truths about the relationship between head position and mental states.

One thing I noticed a long time ago was that the position of my head during meditation made a surprising difference to my state of mind. If my chin was down even a fraction of an inch, then I’d tend to get tired, or to get caught up in often very heavy emotional story lines, full of drama. If my chin was up even a fraction of an inch, then I’d tend to get lost in thoughts that were generally more speculative and excited. Chin down focuses our energy on the emotions; chin up puts more energy into our thoughts. This is perhaps why when someone’s depressed we tell them to “keep their chin up” and when someone’s a dreamer we say they have their “head in the clouds.” Both of these metaphors convey essential truths about the relationship between head position and mental states.

In the ideal position the back of the neck feels long and open, almost as if a space were opening up between the skull and the first vertebra. In this position the muscles holding the skull in place are doing the minimum amount of effort. When the head is nicely balanced on top of the spine in this way, with the chin slightly tucked in, and in a “neutral” position, then it’s easier to be mindfully aware of both our thoughts and emotions without getting sucked into either of them. We can maintain a more mindful distance between us and our experience. We’re, to use another popular idiom, “level-headed.”

Explore meditation with Bodhipaksa's Wildmind: A Step-by-Step Guide to Meditation

To some extent this relationship seems to be one of simple cause-and-effect from mental state to posture. If you’re excited, then the body’s muscle tone is higher, and the muscles on the back of the neck tense up, raising the chin. If you’re feeling low in energy, then the body’s muscle tone decreases, and you slump, bringing the chin down. In a balanced state the head is held in a balanced way.But the causal relationship also works in reverse. If you adjust the angle of the head, then the mind shifts in energy and focus. And so this is something we can be aware of and use in our meditation practice. Whenever we sit down to meditate, it’s advisable to first check out and adjust our posture. We need to make sure that the body’s position is going to support both alert mindfulness and relaxation. And as part of that check-in with the body, we can make sure that the head is in an appropriate and helpful position. Ideally, the head should be balanced effortlessly on top of the spine.

If, during meditation, we notice that the head has drifted out of alignment, we can bring it back to this point of balance.

I’d like to suggest two experiments for you to try out, so that you can explore the powerful affect that our head position has on our experience.

1. So start by setting up your posture for meditation, and let the head find a natural point of balance on top of the spine. Let your breathing settle, and notice how much of the breathing is happening in the chest, and how much in the belly.

Then, try dropping the chin a fraction of an inch, and notice again how much of the breathing is happening in the chest, and how much in the belly. And then bring the head back to a neutral position.

Then, try raising the chin a fraction of an inch, and notice how much of the breathing is happening in the chest, and how much in the belly.

What did you find?

This varies from person to person, but most people notice an effect. Generally, people find that dropping the chin makes it harder to breathe into the chest, and the breathing shifts to the belly. When we breathe more into the belly, the mind can become calm, but sometimes it becomes dull. Most people find that when they raise the chin the opposite happens. It becomes harder to breathe into the belly, and it’s more natural to breathe into the chest. Chest-breathing tends to promote mental excitement. In the balanced position, it’s easier to use both the chest and the belly in order to breathe (although of course we may have habits that favor one or the other manner of breathing).

A few people have reported the exact opposite of what the majority of people notice: as the chin goes up they breathe more into the belly. I’d love to know what’s going on there.

2. Let’s repeat the previous experiment, but this time notice the degree of light or dark that we perceive internally.

Try it with the head in a normal position. Notice how light or dark your internal experience is.

Then drop the chin. Notice how light or dark your internal experience is. Then come back to neutral.

Then raise the chin, and notice how light or dark your experience is.

Often our light sources are above us, so it’s not surprising that when the chin’s up our experience is brighter, and when it’s down our experience is darker. I don’t think there’s anything mystical about this. It’s possible that there’s some kind of blood-flow issue involved as well, though, since sometimes I think I can detect this change even in the dark. It’s quite possible that this is wishful thinking, however.

All the same, this physical effect of seeing more or less light has an effect on the mind. One of the traditional remedies for sleepiness in meditation is to open the eyes, or to visualize light, or to look at a source of light. And often meditation halls are slightly darkened in order to produce a calming effect. So the angle of the head, by adjusting the amount of light we perceive, may also affect our degree of alertness.

I think this is all important to be aware of because we need all the help we can get in being mindful. It would be most helpful if we could maintain a balanced position for the head during meditation (and in the rest of our lives). But we can watch for the chin drifting out of alignment and gently bring it back to a point of balance.

Sometimes I’ve used head position as a tool, however, by deliberately putting my head out of alignment. When I’ve been overcome by sleepiness in meditation I’ve sometimes consciously raised my head a fraction of an inch. The head still tends to start dropping as I nod off, but I have more time to catch it on the way down because it has further to go! Basically I catch the chin falling from a raised position to a normal position, and bring it back up again. I’ve never tried going that far in the opposite direction; in other words when I’m overexcited I don’t tend to drop the chin down below a normal position. Maybe I should try that. Usually, I just bring it back to a point of balance, and use other techniques to calm the mind.

So, what did you find it trying out these two experiments? Is there anything else you’ve learned about the importance of head position in meditation?

May 17, 2012

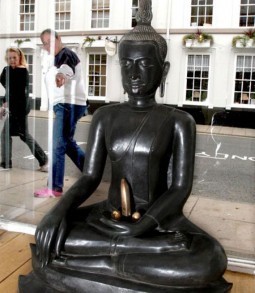

Buddha statue, Nagaloka

A photograph of a Buddha statue at Nagaloka Buddhist Center in Portland, Maine, taken when I was leading a workshop there a few weeks ago.