Bodhipaksa's Blog, page 70

September 18, 2012

Four ways to show love

In several places in the Pali canon, the Buddha praised loving families. For example:

To support mother and father,

to cherish wife and children,

and to be engaged in peaceful occupation

— this is the greatest blessing.

And this:

Husband and wife, both of them

having conviction,

being responsive,

being restrained,

living by the Dhamma,

addressing each other

with loving words:

they benefit in manifold ways.

To them comes bliss.

If you like what we do here on Wildmind, I’d invite you to support us by visiting our online meditation supplies store.

A recent article in the Wall Street Journal emphasizes the importance of affection in relationships, and the advice comes, poignantly, from people who have undergone divorce, as related in psychologist Terri Orbuch’s book, Finding Love Again: 6 Simple Steps to a New and Happy Relationship.In particular there are four components of affection that divorced people said were important:

How often the spouse showed love.

How often the spouse made them feel good about the kind of person they are.

How often the spouse made them feel good about having their own ideas and ways of doing things.

How often the spouse made life interesting or exciting.

The first of these, “showing love” includes “compliments, cuddling and kissing, hand-holding, saying ‘I love you,’ and emotional support.”

It’s the last three that are perhaps least obvious. It’s not hard to remember that a kiss or a hug communicates love, but helping someone feel good about the person they are is a very special and beautiful thing. And it’s something we might be inclined to forget.

One word of caution: when we see lists like this one of the first things we often do is to measure our significant other up against the criteria. This is not only unhelpful, it’s potentially disastrous. We need to focus on ourselves first. How do we measure up? What do we need to do more of, in order to be a more affectionate partner?

Remember to show love

In several places in the Pali canon, the Buddha praised loving families. For example:

To support mother and father,

to cherish wife and children,

and to be engaged in peaceful occupation

— this is the greatest blessing.

And this:

Husband and wife, both of them

having conviction,

being responsive,

being restrained,

living by the Dhamma,

addressing each other

with loving words:

they benefit in manifold ways.

To them comes bliss.

A recent article in the Wall Street Journal emphasizes the importance of affection in relationships, and the advice comes, poignantly, from people who have undergone divorce, as related in psychologist Terri Orbuch’s book, Finding Love Again: 6 Simple Steps to a New and Happy Relationship.

In particular there are four components of affection that divorced people said were important:

How often the spouse showed love.

How often the spouse made them feel good about the kind of person they are.

How often the spouse made them feel good about having their own ideas and ways of doing things.

How often the spouse made life interesting or exciting.

The first of these, “showing love” includes “compliments, cuddling and kissing, hand-holding, saying ‘I love you,’ and emotional support.”

It’s the last three that are perhaps least obvious. It’s not hard to remember that a kiss or a hug communicates love, but helping someone feel good about the person they are is a very special and beautiful thing. And it’s something we might be inclined to forget.

One word of caution: when we see lists like this one of the first things we often do is to measure our significant other up against the criteria. This is not only unhelpful, it’s potentially disastrous. We need to focus on ourselves first. How do we measure up? What do we need to do more of, in order to be a more affectionate partner?

September 15, 2012

Jesus meditating

Somewhere on the web I came across this interesting rendition of Jesus sitting in meditation posture.

I’m normally turned off by modern pictures of Christ, either because of the crucifixion aspect, or the general sappy vibe that a lot of them have, but I rather like this.

September 14, 2012

Becoming a rock-solid regular meditator

I really admire those few people I know who can honestly say they’ve been meditating for 10 or 20 years, and that they’ve never missed a day. I’ve been meditating for 30 years, but I’ve never been able to attain that kind of regularity. Sure, I’ve had periods of months at a time when I’ve never missed a day, but eventually I get tripped up and start missing days here and there. It doesn’t help that I have two young kids and that my sleep is often interrupted.

I really admire those few people I know who can honestly say they’ve been meditating for 10 or 20 years, and that they’ve never missed a day. I’ve been meditating for 30 years, but I’ve never been able to attain that kind of regularity. Sure, I’ve had periods of months at a time when I’ve never missed a day, but eventually I get tripped up and start missing days here and there. It doesn’t help that I have two young kids and that my sleep is often interrupted.

In some ways this irregularity might not matter. I’ve made progress. I’m kinder than I used to be. I’ve experienced all kinds of meditative states, including the jh?nas and (so-called) formless jh?nas). Heck, I’ve even had some powerful insights. But in some ways it definitely does matter. When I go through a period of meditating every day without fail, I find that my meditation practice really takes off. When I miss days here and there the quality of my meditation practice deteriorates. I lose momentum, and meditation seems more like maintenance than construction. Worse, the quality of my life suffers.

I suspect that the difference between people who meditate without fail and those who don’t (or can’t) is that the former see meditating daily as part of who they are. It’s just what they do. They don’t have to think about it, because it’s part of their identity. Those who struggle with meditating daily see that kind of rock-solid daily practice as something they need to achieve. And there’s a sense of doubt about this: “Will I ever get there?” And this doubt becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy because doubting you’ll ever sit every day without fail makes it less likely that you will.

How long do you have to sit anyway, before you develop this rock-solid confidence? This sense that “yes, meditating daily is just what I do. It’s part of who I am”? I’ve gone for months without missing a day, and then I have a late night and an early start the next day, and I’m back to being a non-regular meditator.

Is this familiar to you?

Recently I’ve been using an affirmation to help me get past this stumbling-block of doubt. It’s been helping me, and it may help you, too.

So here it is. Try repeating to yourself: “I meditate every day. It’s just who I am. It’s what I do.”

It’s pretty simple. I’ve been dropping this thought into my mind throughout the day. I did it while walking to work today. I even did it during my meditation, because I think that thoughts deliberately introduced into a still (well, relatively still) mind have more effect. Say these words as you lie in bed, before you go to sleep. Write them down, or stick a note to your computer monitor or on your car dashboard to remind you to call them to mind.

I feel a sense of confidence as I say these words. I can feel my sense of who I am changing.

I’ve been finding that by repeating that affirmation I’m building in to my sense of self the expectation that I’ll meditate daily. It therefore isn’t an “extra” to be fitted in. It’s part of how I see myself.

It’s definitely helping. I’m not promising that this will work, but you can regard it as an experiment. Maybe it’ll help you, too.

September 12, 2012

The goodness at the heart of us all

At a discussion group last night, we talked a little about the deep yearning for happiness that we all have. The discussion was sparked off by this statement:

At a discussion group last night, we talked a little about the deep yearning for happiness that we all have. The discussion was sparked off by this statement:

Most – perhaps all – of what we human beings do, say and think is associated with our attempt to escape from dissatisfaction or suffering, or, to put it the other way around, to find satisfaction and happiness.

I can actually remember when and where I had this insight myself. It was a real eye-opener for me to realize that everyone just wants to be happy, and that everything they do is an attempt to find happiness. Even the cruel and selfish things that people do (that we do) are attempts to deal with dissatisfaction and to find happiness.

So the problems we have are with the strategies we employ to find happiness. Below those strategies are needs and desires that are entirely good.

The reason that this insight so struck me was that it allowed me to find a way past people’s behavior, or rather past my judgements of their behavior, so that I could find some compassion for them. If people are just trying to find happiness, but in a confused way that doesn’t actually work and ends up causing further suffering for themselves and others, then I no longer had to see them as “bad.” The badness was a superficial layer of ineffective strategies (their behaviors) overlying a deep yearning for wholeness and freedom from pain.

Check out Bodhipaksa's meditation CDs and MP3s

The Buddha called this yearning “tanha,” which literally means “thirst.” I think it’s significant that he chose a word that refers to a simple biological need, rather than a more loaded term like “craving.” (Although he obviously used that word too, I think it refers to something a bit different from this primal need for wholeness and freedom from suffering.)I can’t say that this insight changed my life overnight. It wasn’t magic, and didn’t erase my impatience, my tendency to judge, my habit of being critical. But it did open a crack through which the light of compassion could shine. And the crack’s been getting wider.

At the end of a period of Dharma study, I like to spend a little time thinking about what was most relevant to my life, and what, specifically, I will work on in the coming week. And I write it down, otherwise I’ll get caught up in daily activities and forget about it. So for me, this week, I’m going to be working on remembering that all the people I deal with are simply trying to be happy. They’re often just not very good at it (although some are very skilled!). And I’m going to apply this to myself as well. When I find myself doing something I don’t think is me at my best (getting impatient with my kids, resisting meditating, eating something unhealthy) I’m going to remind myself that this is just me seeking happiness through strategies that simply don’t work very well. Already I have a sense that this is liberating. It frees me from self-judgement and allows me to have more compassion for myself. And there’s an implicit reminder that there are other ways to act.

September 8, 2012

Full-screen living

Leo Babauta has a great post at Zen Habits (a site I must remember to visit more often) on Full-Screen Living.

Leo Babauta has a great post at Zen Habits (a site I must remember to visit more often) on Full-Screen Living.

Many of us who write, he points out, use tools that simplify our computer screens. My last book, and most of my blog posts, were written in an application called WriteRoom, which presents me with a black screen, green plain type, and no formatting options, toolbars, or any other distractions. When I’m reading news articles on the web I often use “Readability,” which is a browser plugin that reformats the screen to make reading an undistracted full-screen experience. Babauta mentions these options, and more, and this may be new to you, but it’s something I’m already deeply into.

But where he gets really interesting is when he takes “full-screen” as a metaphor for life. It’s a brilliant metaphor, and along with many other writers I’m kicking myself that I didn’t think of it myself. Here’s the juicy part of his article:

That’s fine for computer work, but what about life in general? You can live exactly the same way.

If you’re going to spend time with your child, don’t switch between the child tab and the work tabs in the browser of your mind. Put your child into full-screen mode, and let him take up all your attention, and let work and everything else you need to do later fade into the background.

You’ll still get to the work, when you’re done with what you’re doing with your child, but for now, be fully in this one activity, with this one person. When you’re done with that, you can bring your work into full-screen mode, and let the rest of your life go into the background for the moment.

If you eat, let the food fill up the screen of your attention, not your thinking about other things. If you’re showering, let that fill your attention, instead of planning. When you’re brushing your teeth, let the “conversation” (read: argument) you had earlier fade away and just brush your teeth.

When you work, do one task at a time. And don’t just do one task at a time, but do that task with all your attention (or as much as possible), and don’t be thinking about the other tasks.

But how do we do this. Babauta has some advice on this too, but I’ll let you read that on Zen Habits.

September 6, 2012

Om Ah Simpson

Found on Google+, and the source tracked down with the help of Rod Meade Sperry at Shambhala Sun.

Homer Simpson on a donut zafu, holding a mala and pretzel. Yours for only $50.

August 31, 2012

Thai Group says Steve Jobs reincarnated as warrior-philosopher

A rather quirky Buddhist organization has taken the distasteful, and I must assume dishonest, step of making claims about Steve Job’s rebirth. Many people only became aware that the Apple leader was a BUddhist when he died last year after a prolonged battle with cancer.

According to the Wall Street Journal, the Dhammakaya Group in Thailand is now claiming that “Mr. Jobs has been reincarnated as a celestial warrior-philosopher .. and he’s living in a mystical glass palace hovering above his old office at Apple’s Cupertino, California headquarters.”

The WSJ pointed out that the widespread grief many felt after Jobs’ passing took an odd form, when some of hisadmirers in Malaysia “gathered on a tropical island and in a religious ceremony each took a bite from an apple before flinging the fruit into the sea in a bid to speed up his reincarnation.”

Now, over in Thailand, Phra Chaibul Dhammajayo, who is the abbot at the Dhammakaya Temple north of Bangkok, is claiming that Mr. Jobs has already been reborn.

“After Steve Jobs passed away, he was reincarnated as a divine being with a special knowledge and appreciation for science and the arts,” the Dhammakaya leader said in the first of a series of sermons beamed to hundreds of thousands of the group’s followers around the world.

The WSJ charitably notes that “Phra Chaibul’s claims are impossible to corroborate.” it seems reasonable to assume that they are, in fact, either fabrications or delusions.

It also notes that Chaibul has faced criticism for his claims, which have been accused of being part of a fundraising campaign. Sadly, that sounds about right. I have to say that Dhammakaya’s claims smack of an attempt to profit from the death of a prominent Buddhist.

It is salutary for us to remember that the Buddhist world is not as “pure” as we sometimes might like to think it is.

August 29, 2012

“A little bit pregnant”

In the Buddha’s day, many people got enlightened quickly. Some people would say this is because the Buddha was such a great teacher, and to some extent that’s got to be true. What better than to have an expert around? But most of the monks and nuns and householders would have had very little contact with the Buddha. After all, he couldn’t be everywhere!

In the Buddha’s day, many people got enlightened quickly. Some people would say this is because the Buddha was such a great teacher, and to some extent that’s got to be true. What better than to have an expert around? But most of the monks and nuns and householders would have had very little contact with the Buddha. After all, he couldn’t be everywhere!

What they did have, that was every bit as helpful as the presence of the Buddha, was the belief that enlightenment was possible. Having the Buddha around was helpful, perhaps, not so much because he was a “personal trainer” who was around to say just the right thing. It was more that he was a living example of what was possible. And as a result of the confidence this brought about, people awakened.

Even when people at the time of the Buddha talked about getting awakened in future lives, they didn’t talk in terms of the “countless lifetimes” that the Mahayana later came to regard as being necessary. They usually expected to get enlightened very soon, perhaps in the very next life. But the focus was very much on awakening here and now.

Nor did people at the time of the Buddha talk about deferring their own awakening until all others were awakened. This is another peculiar Mahayana idea that I believe makes enlightenment seem further away. It in fact makes enlightenment impossible. You just have to look at the Buddha’s own life to see how hollow this concept is; after all, the Buddha didn’t defer his own awakening! It might sound very noble and compassionate to say that we won’t get enlightened before others do, but surely the most compassionate thing we can do is to wake up right now, so that we can help others free themselves from suffering.

Now the first stage of enlightenment is traditionally held to be not far away from where we are. This use of “stages” of enlightenment can be confusing for people. We don’t always know there are stages to awakening. We think it’s all or nothing. Once I was teaching a class and I mentioned the traditional stages of awakening, and someone said, “Can you be a bit awakened? Isn’t being a bit awakened like being a little bit pregnant?” Actually, pregnancy’s a good metaphor. There is a big difference between having just conceived and being nine months pregnant, and between that and giving birth, and between that and having a toddler or a teenager. In other words, just as having a child is a process, so too awakening is a process. We’re all involved in this process of conceiving Buddhas, in giving birth to Buddhas, in giving birth to our own awakened selves.

Check out Bodhipaksa's meditation CDs and MP3s

So there are these stages in the process of awakening, of which the first stage is called “stream entry.” Like getting pregnant, this first stage, stream entry, is not that difficult. Well, stream entry is a bit more difficult than getting pregnant, at least for most people. My own teacher, Sangharakshita, encourages us to take stream entry as a “doable” goal for this life. It’s a significant goal because it’s irreversible. Up until stream entry our movement in the direction of awakening is reversible. We make progress, and then we fall back. We begin to wake up, and then we fall back into a sleep. Perhaps the dreams are interesting! But at stream entry there’s an unstoppable momentum behind the change, because you’ve really seen the truth of the marks for yourself. You’ve seen something, and you can never unsee it.We’re all, I’d say, half way to that point of no return. Stream entry is a doable goal. It’s quite concrete, and quite achievable. Even non-Buddhists seem to be able to attain this.

Now people still try to see stream entry as being more distant than it is! It’s quite extraordinary how we try so hard to make goals unattainable. Some people take the idea of stream entry and raise it up to a kind of perfection. They imagine the stream entrant as being close to perfect: not capable of being unethical, never getting into bad moods, never getting anxious, never annoying anybody, never having cravings. But that description is more like full Buddhahood (with the exception of annoying people — the Buddha really annoyed a lot of people). To get to full awakening, we have to break ten fetters, and these include ill will and craving, and those are going to be there for two out of the four stages of awakening. To get to stream entry we only have to break three fetters, so we still have greed, hatred, and a lot of delusion to overcome.

At a guess I’d say a reasonably diligent practitioner — not a monk, but someone with a job and family, for example — could go all the way to stream entry in 15 to 20 years. Some people think that’s a long time and get demoralized. But what are you going to do with your life anyway? And it might take much less time. Insight can come out of the blue. It involves a slight shift of consciousness. It could happen right now, right this very moment!

Although meditating is important, awakening probably won’t happen for you when you’re meditating. It’s more likely to happen when your mind is wandering, or when you drop something, or when you hear something and suddenly you see things in a different way. In the scriptures it’s recorded that some people awoke when they were depressed, or even on the point of suicide. For me it happened when I was putting my daughter to bed.

I think it’s supremely important to believe that enlightenment is possible for us, and that it’s not too far away. If you believe something’s impossible for you, it effectively becomes impossible. Once awakening happens, the thing that strikes you most about it is how easy it all was. Once it’s happened — once you’ve seen the truth that your “self” is not a “thing,” but a beautifully unfolding process — you wonder why it took you so long. The truth was sitting there in plain view the whole time, but for some reason you never looked.

So I’d urge you to open to the idea that awakening could happen anytime. That it’s just around the corner. That it’s a slight shift in perspective away. Once you accept that, anything can happen.

August 21, 2012

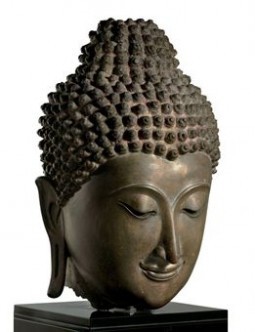

The first western portrayal of the Buddha?

Twitter still has its uses. While keeping an eye out for new Fake Buddha Quotes to document, I came across a link to a post at a rather eclectic blog called Obsidian Wings. The post was written by someone who calls himself Doctor Science, who I know little about Doctor Science except that he’s from New Jersey and has an MA in theoretical population genetics.

He’s not an art historian or religious scholar, but he’s spotted something interesting in Pieter Aertsen’s Adoration of the Magi. Pieter Aertsen, in case (like me) you haven’t heard of him, lived from 1508 to 1575, and was a Dutch historical painter. According to Wikipedia, “He was born and died in Amsterdam, and painted there and in Antwerp, though his genre scenes were influential in Italy.”

One of Doctor Science’s “sprogs” (children to non-Brits) commented that the young man in the center looked like the Buddha. And the sprog seems to be right.

One of Doctor Science’s “sprogs” (children to non-Brits) commented that the young man in the center looked like the Buddha. And the sprog seems to be right.

Could this be an image of the Buddha, given the time? It’s worth bearing in mind that in 1954, archaeologists excavating a Viking ruin in Helgö in Ekerö Island in Lake Mälaren in Sweden found a 10 cm (4″) Buddha statue that scholars have pinned to the Swat valley in North-western India. That wasn’t the only exotic artifact found at that site. Items from Byzantium and Egypt were also excavated. Although at the time Aertsen was active, Dutch trading with Asia had not yet begun — the first Dutch expedition round the Cape to the far east took place in 1595, it’s not inconceivable that artifacts could have made their way, through other means (which I’ll discuss shortly) to Europe.

Doctor Science hypothesizes that Aertsen may have seen a Buddha statue, and made a quick sketch, not quite understanding what he was seeing with respect to the Buddha’s hair-style, which is portrayed in the painting by a kind of “helmet” made of straps, along with some kind of top-knot.. To shaw what he might have been trying to represent, here’s a 15th century Buddha head from Thailand, with the Buddha’s hair shown in tight curls, along with a top-knot. The resemblance is striking, and it’s easy to see how Aertsen might have thought this was a helmet.

Doctor Science hypothesizes that Aertsen may have seen a Buddha statue, and made a quick sketch, not quite understanding what he was seeing with respect to the Buddha’s hair-style, which is portrayed in the painting by a kind of “helmet” made of straps, along with some kind of top-knot.. To shaw what he might have been trying to represent, here’s a 15th century Buddha head from Thailand, with the Buddha’s hair shown in tight curls, along with a top-knot. The resemblance is striking, and it’s easy to see how Aertsen might have thought this was a helmet.

The figure Aertsen paints is very androgynous, which is not uncommon in Buddha statues, especially from Thailand. Aertsen says that this figure is “an attendant to the old King who’s greeting Jesus.” Interestingly, he’s the only person in the room who’s being looked at, besides the infant Jesus; the younger attendant to the old King is gazing at him. Doctor Science says that the three Magi can to be seem as representing Europe, Africa, and Asia, with the oldest of the three being Asia. This connects the “Buddha” as an Asian figure.

The “Buddha” is in vaguely military garb, with a breastplate and kilt, which is obviously very different from how a Buddha statue would portray the Buddha’s dress. This makes me wonder if Aertsen saw not a full-body statue, but merely a head, like the one shown above. Perhaps, thinking that the Buddha’s “do” was a helmet, he decided to portray the rest of the body in this “military-lite” fashion. The scanty armor of the “Buddha” would fit with him being more of a prince than a mere attendant, which is perhaps why he’s being looked at by the boy servant holding “Asia’s” robe.

The “Buddha” is in vaguely military garb, with a breastplate and kilt, which is obviously very different from how a Buddha statue would portray the Buddha’s dress. This makes me wonder if Aertsen saw not a full-body statue, but merely a head, like the one shown above. Perhaps, thinking that the Buddha’s “do” was a helmet, he decided to portray the rest of the body in this “military-lite” fashion. The scanty armor of the “Buddha” would fit with him being more of a prince than a mere attendant, which is perhaps why he’s being looked at by the boy servant holding “Asia’s” robe.

As Doctor Science points out, Aertsen worked in Antwerp from about 1535 until 1556 or so, and from 1508 Antwerp was the site of a Portuguese “factory” which served as a northern European distribution center for Portuguese spices from Asia. It’s certainly conceivable that Portuguese traders brought a Buddha statue back to Europe while returning from one of their spice runs.

Doctor Science asks, “There’s a great project here for someone who can find and read the primary sources: is there any direct evidence that images of the Buddha arrived in Europe before 1600, or even 1700?”