Brendan I. Koerner's Blog, page 17

August 3, 2012

Knockoffs: Supertrain

Granted, I haven’t always been great about keeping up with Microkhan series dedicated to pop culture—both Bad Movie Friday and The Ponchos have fallen by the wayside over the years. But that isn’t going to stop me from launching a whole new series, one dedicated to craven acts of imitation which reveal the cynicism behind much of the entertainment products we consume. I’m gonna call it Knockoffs.

The series’ inaugural subject, NBC’s laughably terrible Supertrain, is a perfect way to kick things off. Like all future Knockoff “honorees,” its concept is obviously copped from an earlier hit—in this case, ABC’s The Love Boat. It takes little imagination to envision the executive meeting at which Supertrain was conceived—men in suits sat around a table and thought, “Okay, let’s do Love Boat, but on some other means of transport. A truck? A dirigible?”

As you might imagine, Supertrain was not long for this world, despite its awesome title-sequence music. After a few weeks of poor ratings, NBC fired much of the production staff, blaming them for failing to give the show a “mystery-adventure” feel. The axed executive producer, Dan Curtis, volleyed back with this nice rejoinder:

You want a light, bright show with mystery and comedy and sophisticated humor and suspense? And you want it once a week? Good luck!

Once the whole Three Mile Island situation went down, there was just no saving Supertrain, which was canceled after just nine episodes. People turned rather sour on the fantasy of having an atomic-powered train roaming the country.

Ideas for Knockoffs? Leave ‘em in comments, please. I’m looking for movies, TV shows, books, or other pop-culture artifacts in which imitation was motivated not by a sincere desire to flatter, but rather base cynicism about the profits to be made.

August 2, 2012

Firefighters, Firebugs

If I so desired, I could probably make this blog all about firefighters-turned-arsonists and still have enough material to post at least once a week. The latest example comes from Opp, Alabama, where a firefighter allegedly set a mobile home ablaze for no discernible reason.

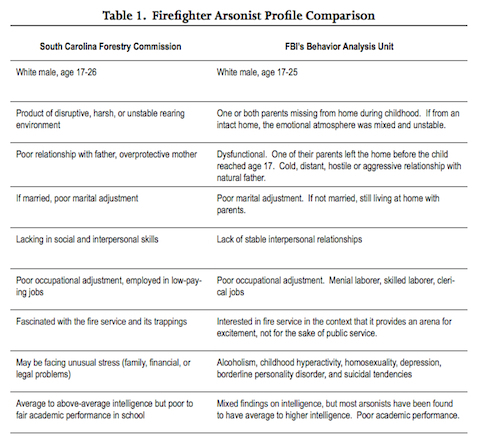

The problem has been serious enough in years past for the Department of Homeland Security to compile a special report, from which the table above (click to enlarge) is drawn. The report’s choicest section deals with motives, and includes this choice quote from an FBI investigator that gets to the heart of why criminals’ rationales so often elude comprehension:

Motives for arson, like other aspects of human behaviors, often defy structured, unbending definition. Strictly speaking, who can argue that vandals are not looking for excitement when they are engaging in their malicious mischief? Add an element of power and revenge and one can see the problem of strict, unyielding classification. Be aware that motivations may change.

That last line is key: Criminals themselves typically don’t totally understand what drives them, and so they will cite different motives over time. This vastly complicates our efforts to understand them—those who disregard society’s conventions have no interest in making our attempts at pop psychology any easier.

This is an irritating truth for writers, of course. How much easier our jobs would be if we could accurately summarize an evildoer’s motives in a single paragraph. And yet how many of us still attempt to do just that, even though such shortcutting does a disservice to our craft.

August 1, 2012

Sever All Ties

I turned in the second draft of my book yesterday, an event that made me more anxious than glad. I realize now that I only have a few weeks left to sort out some lingering mysteries in the central plot, specifically those related to the main characters’ inner dramas. Without giving too much away, my two protagonists turned their backs on everything they knew, and everyone who loved them. One came to regret that decision, and one did not—though perhaps that is an over-generalization. How did this act of total rejection fit into their attempts to take charge of their own narratives?

I turned in the second draft of my book yesterday, an event that made me more anxious than glad. I realize now that I only have a few weeks left to sort out some lingering mysteries in the central plot, specifically those related to the main characters’ inner dramas. Without giving too much away, my two protagonists turned their backs on everything they knew, and everyone who loved them. One came to regret that decision, and one did not—though perhaps that is an over-generalization. How did this act of total rejection fit into their attempts to take charge of their own narratives?

One masterpiece I’ve been looking to for inspiration is “The Making of a Terrorist,” a five-part United Press International series from 1970. (Link here; scroll down to the bottom for the stories.) The series, which earned a Pultizer Prize, recounts the short but fascinating life of Diana Oughton, the daughter of a wealthy Chicago family who died while building bombs for the Weathermen. It is an epic piece of reporting, rich in detail about Oughton’s transformation from privileged young lady to violent radical. This passage, in particular, is something I’ve been reading again and again; it describes a key moment from the two years that Oughton spent in Guatemala, working for Quaker-run volunteer program:

Diana’s growing concern over the American influence in Guatemala was matched by a growing dislike for the American tourists who came to Chichicastenango and stayed at the Mayan Inn, where the spent enough in a week to support an entire Indian family for a year. She hated the Americans’ gaudy clothes, their broken Spanish, their silly questions, the way they snapped pictures of the Indians. She began to hate doing the marketing because the Americans would always spot her blonde head above the crowd and ask what in the world an American girl was doing in such a godforsaken spot.

Diana’s distaste for American extravagance was also directed at her friends. When an old college friend and her husband, both heirs to large fortunes, came to Guatemala for a visit, Diana was disgusted by their complaints about the food and water and by their extravagant spending. “My God,” Diana said to Kimmel after the couple had left, “She used to be my very best friend in the whole wide world.”

That moment resonates with me because it’s something we’ve all experienced to some degree: the realization that the people with whom we shared childish pleasures have become strangers to us. But for Oughton, it represented something even deeper: that when she did return to the U.S., she would never be able to melt back into her previous life. The comfortable yet boring future that had been laid out for her during her years at Bryn Mawr was now odious. She had to find a way let the world know she rejected it in the strongest terms possible.

July 31, 2012

An Inconvenient Excuse

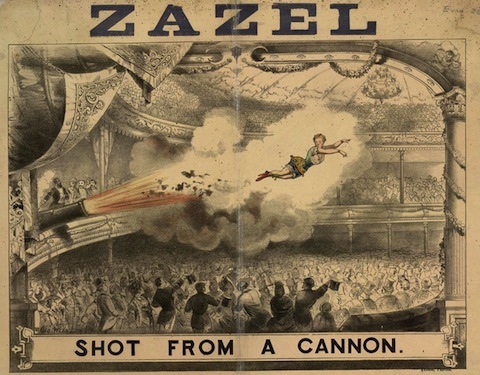

The human cannonball act is one of the most notoriously dangerous in all of circus-dom; performers have little to no control over their movement, so any minute error in firing trajectory is certain to cause catastrophe. The legendary Zazel, née Rossa Matilda Richter, was thus fortunate to survive her 19th-century career, though she did break her back while working for P.T. Barnum. Per this source, however, Zazel could have easily satisfied the English masses by simply removing a few articles of clothing, rather than risking life and limb:

Much of Zazel’s appeal lay in the fact that, in order to fit into the cannon, she had to she most of her Victorian clothing.

How many human cannonballs had to perish because of England’s sexual repression?

A wonderful gallery of Zazel photos here. And more biographical details here; kudos to her for her early advocacy of firefighter nets.

July 30, 2012

Penultimate Push

Endeavoring mightily to complete the second draft of the book by day’s end. Revel in the awesome that is Pearl Chang, and catch you back here tomorrow morning.

July 26, 2012

Reality Check

Compared to the Games of the late Cold War, when steroids were integral to athletic success, this year’s Olympics will be remarkably clean. Yet we also know that drug use has not vanished—how could it, give the rewards at stake at the ultra-competitive nature of those tempted to use? The big question is what percentage of cheats are ensnared by the current testing regime.

A definitive answer is impossible, of course, but a little light was shed by an email I recently received from an elite track-and-field athlete—not an Olympian, but someone who competes at the very highest levels of their sport. I promised to protect this person’s identity, for what they had to say was fairly damning, if somewhat hyperbolic:

In the past 8 months, I have been tested outside of competition six times by the USADA. I can only imagine how often USA Track & Field’s top stars are tested. In most countries (e.g. Belarus, Jamaica) they don’t even have a real agency like USADA to conduct Out of Competition tests. Sure, when an athlete wins an event at the Olympics, they get drug tested, but that doesn’t mean the person didn’t use steroids the entire year beforehand and simply stop using them in time for the drugs to clear his/her body at the Olympics. The science, which can be easily ascertained by a chemist or doctor is such that an athlete could still be retaining all of the physical advantages of the drugs without the metabolites appearing in their urine. The fact that most athletes around the world have less than a 0.1% chance of getting tested outside of the Olympics or World Championships is not a deterrent at all. Very few countries have the robust out-of-competition testing regimen that the United States has.

Something needs to be done outside of the Games themselves to ensure a level and fair playing field. If the IOC truly cared about this issue, they would mandate that an athlete have a certain number of random, out of competition tests with a year, six months, and three months from the Olympics.

Digging a bit deeper into the statistics for track-and-field athletes, it seems that my correspondent’s 0.1 percent figure was a bit low. But when I pinged him back with a correction, he made an important observation about the ease with which tests can be skipped:

I know that in the US, if you miss more than three out-of-competition tests during an 18-month period that it is the same as a positive test and you receive a suspension. I know many athletes in other countries go to “training camps” in places like South Africa for weeks or months at a time during the off-season and may not report their whereabouts to avoid testing officials.

The upshot is that elite athletes in many countries have the odds in their favor should they elect to enhance their performance with drugs. The penalties for getting caught are extreme—one could lose everything, as lengthy bans are the norm. But if you’re smart about your intake and your national sports authority doesn’t give a damn about testing, you may only face a one in ten chance of detection. After dedicating your whole life to an arcane pursuit, and knowing that drugs could provide just the boost you need to achieve athletic immortality, who wouldn’t take that risk?

July 25, 2012

The Perils of Going Legit

I’m one of those blokes who will argue ’til the end of time that The Godfather: Part II far surpasses the original. That’s largely because of the whole Vito Corelone backstory, which includes the single greatest flawed gangster of all time. But I also dig the quiet tension created by Michael Corleone’s vacillation over his family’s future. The angel on his shoulder tells him to make good on his promise to his wife and take the whole enterprise legit; the devil, of course, whispers very different instructions in his ear.

In the late 1960s, Chicago’s Conservative Vice Lords faced a similar choice. The gang ultimately opted to join the legitimate economy by opening a series of businesses on the city’s depressed West Side. They did so with seed money obtained from a number of charitable foundations, including the Rockefeller Foundation, which saw the CVLs’ transition to enterprise as a key step in Chicago’s renewal.

But within a few years, all of the CVLs’ stores had closed and they were back to working in the shadows, to Chicago’s great detriment. This fascinating post-mortem offers up a bevy of explanations for the CVLs’ failure, most of which can be distilled into a single adage: Street skills don’t necessarily translate into boardroom skills. This lesson, in particular, is something that Michael Corleone knew all-too-well:

While Vice Lord leadership were using these [businesses] to remake themselves into a bona fide community and political powerhouse, many of the thousands of rank-and-file Lords members, who were still facing conditions of poverty and blight (CVL, Inc., leaders took yearly salaries between $10,000 – $15,000), continued to act as violent criminals. Traditionally, leadership of a street gang goes to the biggest, strongest, and most violent members, and these leaders must constantly be on guard against newer, younger members, who attempt to prove themselves even more violent than their leaders. This is how the Vice Lords had always operated, and now Perry, Alford, Gore, and others, who by the late 1960s were in their late 20s, faced thousands of power-hungry teenagers bent on rising in the gang hierarchy, especially a subgroup of young Vice Lords calling themselves the Black Aces. Thus, violence was difficult to avoid.

It’s not clear from the write-up whether the CVLs’ leadership ever considered taking on young rivals as salaried employees, which might have been wise. Enemies closer than friends and all that.

Many more Conservative Vice Lords artifacts here. I love their letterhead.

July 24, 2012

Caught in the Act

A day late on this month’s deadline for my Wired column, so you’ll have to wait twenty-four hours for my cogent thoughts on either human cannonballs or gang entrepreneurship. (Sorry, haven’t decided yet.) In the meantime, occupy your spare moments by delving into this salacious collection of trial pamphlets, which provided true-crime buffs with plenty of reading material in the era before yellow journalism. The illustrations of the cases involving “criminal conversation” with married women (see above) are particularly delightful.

July 23, 2012

The Weight of a Prank

Nineteen days ago, a Swedish advertising agency made waves by airdropping a thousand teddy bears over Belarus—a minor protest against the nation’s repression of free speech. A student in Minsk posted several photos of the bears on his site, and was subsequently arrested by Belarusian authorities for undisclosed reasons. That arrest caused the Swede behind the stunt to release this rather awesome open letter to President Alexander Lukashenko, which I sincerely hope will pop to everyone’s mind whenever they hear the name of Belarusian dictator:

Recently, you announced that you, personally, guaranteed the effectiveness of the Belarus defence. You have spent 20 billions of euros on an air defence system that could not detect a homebuilt aeroplane with a cargo of teddy bears. As Pavel Kozlovsky, former Belarus minister of defence, expressed: You lead a regime that puts all its energy into pretending that the patient is healthy, but none into curing her.

Reports in Russian media – which you dare not censor – have caused many people to laugh at you. On the internet, you are described as a clown. But we are not naive. You are something much more frightening – an armed clown. Though in the long run, not even a heavily armed clown can stop people from laughing. And when people laugh at you, not even your friends will want to stick around.

A ground’s-eye view of the airdrop can be seen here. I guarantee you that someone fetched that bear that got caught in the tree; fingers crossed that they were not arrested for doing so.

July 19, 2012

A Milestone in Daredevil Law

There are few more colorful characters in recent modern Cleveland history than Alphonso Woodall, a daredevil who performed as “The Human Kite.” A former Army Air Force mechanic, Woodall built his own rig so he could soar above Lake Erie with water skis strapped to his feet. His derring-do eventually attracted the interest of a B-grade reality show called You Asked for It, which agreed to pay Woodall $500 for his act—though over dry land, attached to a car instead of a boat.

The stunt did not go well, to say the least, and Woodall sued the show’s producers. He was awarded $70,000, which the producers then appealed. The resulting decision established what is the most important precedent in the arcane field of daredevil law, one that establishes that the men and women who risk their lives for our entertainment are not entirely to blame when things go awry. For even the simplest stunt involves the expert participation of support staff—aid that was sorely lacking in Woodall’s case:

Soon after his arrival in Los Angeles on March 22, 1959, one Hochman drove plaintiff from his hotel to the drag strip where the stunt was to be put on. Hochman said he was to be plaintiff’s driver but when plaintiff discovered he had been driving with his emergency brake partially on he refused to have Hochman. So Welo was assigned by defendant to drive in the exhibition flight. Plaintiff gave Welo explicit and repeated instructions as to speed, signals, etc., and Welo was told to slow the car after reaching a speed of 27-30 miles; he agreed to do so. Plaintiff’s last word to Welo before the flight was, “Remember, now, don’t go over 30 miles an hour,” to which Welo agreed. Welo himself testified by deposition: “I have never represented myself to Mr. Woodall or anybody else as being a driver because I am not.” In fact Welo never held himself out to Henderson as a stunt driver, had never been used as such by defendant, but had been assigned to this stunt notwithstanding the assurances previously given to plaintiff.

On the occasion in question, according to plaintiff, Welo started too slowly, was given a signal to go faster and was supposed to accelerate at once; the kite jumped along and did not take off; then Welo gave a quick surge forward and the kite rocketed up. Plaintiff started giving the wave- off signal (for an emergency stop); the kite reversed itself, but plaintiff still felt a forward motion, the kite began to fall and he could no longer control it. They were jerked along the ground and plaintiff could feel the rope taut and could feel the forward motion. His estimate was that the car got up to 45 miles.

The kite turned over on plaintiff and he was seriously injured. He began to yell, “Too fast, too fast, I told him too fast.” A boy who was about five feet from plaintiff when on the ground heard him, less than a minute after the accident, repeating, “I told him not to go too fast.”

There is a halfway happy ending to this tale, at least for Woodall: Though still hampered by his broken leg in early 1960, he rescued a duck hunter whose boat had capsized on Lake Erie. For this he was awarded a Carnegie Medal for heroism—though, unfortunately, the accompanying $500 cash prize caused him some financial problems down the line.

View more photos of the Curt Flood of daredevil-dom here. Yes, he had an odd grudge against Martin Luther King Jr.—chalk it up to the madness of geniuses.

(Image via The Cleveland Memory Project)