Brendan I. Koerner's Blog, page 13

October 17, 2012

When Curves Were King

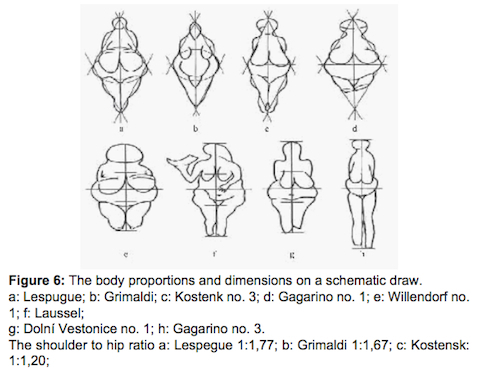

We’re all aware that standards of beauty shift over time, which is why there is such a vast difference between the body types of Peter Paul Rubens’ subjects and today’s Olive Oyl-ish fashion icons. How the taste pendulum swings seems largely tied to a basic law of economics: our species values things according to their rarity or abundance. A great example of this truism can be found in the apparent beauty ideals of our paleolithic ancestors, whose crude statues reveal that they were dazzled by curvaceous females. This recent study (PDF) of 97 female idols created tens of thousands of years ago breaks down the apparent infatuation:

Among the idols studied, 24 were skinny (mainly young ladies) and 15 normal weighed. All of these statues have small breasts, with the exception of two. More than half of the statuettes (51) are representing overweight or very obese females; their breasts mostly were also extremely large…

The association of fat to fertility has been widely discussed in anthropological literature. Through the Paleolithic Era there were frequent starvations, in fact the obesity was rare. As opposed to the sculptures where the skinny subjects are rare but the obesity is often seen. How can we solve this contradiction? I hypothetically would say, the obesity meant the ideal beauty, the prettiness, the desirable.

A slightly different take here, in which the authors contend that our statue-creating Paleolithic forebears were perhaps less interested in sex than in just surviving another godawful winter.

October 16, 2012

Can’t Buy a Thrill

Given that 2.4 million Americans have served in either Afghanistan or Iraq, there is bound to be a point at which some veterans who run afoul of the law will point to their combat experience as a mitigating factor. When lawyers cobble together such defenses, they will doubtless flip back to United States v. Tindall (PDF), a fascinating 1980 case in which a former Army helicopter pilot successfully argued that his combat trauma caused him to become a hashish smuggler.

The defendant, Michael Tindall, was accused of importing hashish from Morocco to Gloucester, Mass., over a six-month period. His lawyers contended that his post-traumatic stress disorder inured him to ordinary sensations, and so he was forced to try riskier and riskier endeavors just to feel some modicum of happiness:

At Tindall’s trial there was testimony that he “started to do what he called ‘crazy things.’ He would take LSD and jump into water, into the rivers and underground caves and would fly over the Everglades at a very low altitude to see if he could get what he called a rush or thrill”…The boat trip from Morocco to Gloucester represented “just another combat mission” to him.

It will be interesting to see whether contemporary juries are open to such explanations. Our collective view of the insanity defense has obviously narrowed over the past few decades.

October 15, 2012

The Beginning of the End

So today’s the deadline for the final draft of my next book; with any luck, I’ll have some bound galleys to give away before Christmas. It’s been a long, draining process—thirty-eight months of reporting, writing, and furious pacing about my shoebox-sized home office. Tough to believe that I’m just a few hundred checked endnotes away from dropping this project into the hands of Crown’s excellent production folks.

Between now and the June 18, 2013 release date, y’all are gonna be hearing a ton about the tale. But for the moment, let me just leave you with a random paragraph plucked from what is currently page 99—a nugget that, according to Ford Madox Ford, should convince you whether or not to press forward:

He held up his Samsonite briefcase and wiggled his left index finger, the one with the metal ring around it. The crew could see that the ring was connected to a piece of cooper wire that led into the briefcase. “This controls the detonator,” he explained. “There is a concussion grenade in here, and eight slabs of C-4. Now, captain, what is your name?”

My dream is to get Morgan Freeman to do the audio book, preferably in the guise of his Electric Company DJ character (above).

October 12, 2012

A Clear Division

I am generally no great fan of books about mountaineering disasters, but Buried in the Sky really got its hooks into me. That’s partly because of its unique narrative viewpoint: the tales protagonists are not the Western adventurers who met with bitter fates on K2, but rather those adventurers’ Sherpa guides. The authors did a fantastic job not only of recounting the guides’ life stories, but also of explaining the nuances of Sherpa culture that help explain why these men were drawn to such perilous work. One such explanatory triumph is the book’s breakdown of the difference between Sherpas and Bhotes, a Nepalese ethnic group to which one of the protagonists belonged—a fact he often concealed, since it make more professional sense for mountain guides to masquerade as famed Sherpas. As it turns out, Bhotes share something rather unsavory with the more traditional residents of Kyrgyzstan:

Bhote, pronounced BOE-tay, stems from Bhot (Sanskrit for “Tibet”), and the Bhotes in Hungung observe many Tibetan customs. With marriage, for instance, the Bhotes of the Upper Arun Valley, like other Tibetan tribal groups, practice bride abduction. When Pasang’s cousin Lahmu Bhote was fourteen, the groom’s brother secured permission from her father, seized her in the night, and dragged her to the wedding. This break from her paternal household may have been ritualized, but it was hard on the bride. “I was miserable for years,” Lahmu said. It took a long time for her resentment to wear off. “When I was twenty-three,” she added, “I finally realized I loved my husband.” Sherpa marriage rites, by contrast, are public-relations campaigns. Before betrothal, a Sherpa couple consults all stakeholders—families and gods—and gets a horoscope cross-check. Sherpas widely consider the Bhote approach, which is less common nowadays, a brutal and primitive practice.

It is puzzling why two such closely related ethnic groups, which have existed in close proximity to one another for centuries, would have such wildly divergent approaches to an essential life event. Perhaps human societies do not influence one another quite as much as those who fear McDonald’s-ization have led us to believe.

Check out more about the excellent Buried in the Sky here.

October 10, 2012

The Micronesian Olympics

The Micronesian Olympics—now known as the Micronesian Games for copyright reasons—were first held in 1969. As these photographs attest, the athletes competed in front of crowds that numbered in the dozens or even less. Yet those first Olympics still occupy a cherished place in the memories of Micronesian sports fans, particularly those whose tastes run toward baseball. As one of the event’s key figures recalls:

I was one of the chief organizers of the ’69 Micronesian Olympics and had the honor of watching Sotup Masatoki Steven urged on and cheer for the Chuukese team. He is truly Legendary.

Yes Susumu also is a Legend. Think he was in his early 50s when he pitched in 1969. The Palauan pitcher was Martin Ngchar. Some citizens of Micronesia call that gold medal game the greatest baseball game in the history of Micronesia.

To those lucky souls in the stands that day, that game must mean far more than the 1958 NFL Championship—even though the players involved never got their shot at the big time. Nor, for that matter, another shot at Micronesian glory; the next games weren’t held for another twenty-one year, by which time even hardy Yes Susumu couldn’t toss a slider to save his life.

Check out the full archive of 1969 Micronesian Olympics photos here. There is something quite alluring about the color processing that the developers used.

October 9, 2012

Mary, Queen of Business

Mary Antisarlook, popularly known as Sinrock Mary, was at one point the wealthiest woman in Alaska. She made her fortune by controlling a herd of approximately 1,500 reindeer, which she inherited after her second husband’s death in 1900. Mary was able to keep the herd together despite numerous legal challenges to her ownership, including those filed by a Swedish schemer who alleged to be her third husband, a conniving mail carrier, and even her own nephews, who argued that Inupiat inheritance traditions always favored males. Yet Mary was also the rare tycoon who did not pay mere lip service to the notion of personal asceticism, as recounted in a definitive 1984 article from Pacific Northwest Quarterly:

The income from her reindeer permitted her to adopt 11 children and to care for countless others…Despite her wealth and success in a rather sedentary occupation that was for eign to Eskimos, who usually changed their abodes with the seasons, Mary remained in outlook an Eskimo woman who fished for salmon and tomcod, dried seal meat and fish for the winter, picked berries and greens, and prepared skins for sewing.

I am trying to picture Marissa Mayer drying seal meat, but the image just isn’t coalescing for me.

Teaser for a Sinrock Mary documentary here.

October 5, 2012

Dedication to Minutiae

Back to endnoting the book today. The whole agonizing process has made me regret my lack of organization while writing—at some point, I just got tired of affixing Post-It notes to each and every primary-source document. I’m paying the price now, and I guess so are y’all—I’m too slammed to post anything richer than the street-style kuduro clip above. Back early next week with something more thoughtful, provided I can track down this one State Department report that has gone MIA in my trash-heap of an office.

October 4, 2012

Life in Limbo

Please take a moment today to check out this astounding collection of mid-1970s photos from Ujelang Atoll, a Micronesian speck that once played host to nuclear refugees from nearby Enewetak. When these particular photos were taken, the Enewetakese had been in exile for three decades, after being bounced from their homes so the United States could detonate 43 nuclear warheads over a period of years.

Contrary to the cheery images featured in the collection, life on Ujelang was far from carefree for the refugees, who were not allowed to resettle Enewetak until 1980. The daily hardships were described in great detail when the Enewetakese pressed for compensation before the Marshall Islands Nuclear Claims Tribunal:

Conditions there were characterized by famine, near starvation, and death from illness due to the severe limitations of the environment and resources on Ujelang. There were also polio and measles epidemics, an uncontrollable infestation of rats, and infrequent and irregular field trip ship service.

In its decision, the Tribunal stated that “the conditions suffered by those relocated go far beyond simple annoyance.” In determining the appropriate amount of compensation, the Tribunal adopted an approach based on an annual amount for each person on Ujelang for each of the 33 years between 1947 and 1980. Recognizing that the period of greatest suffering was from 1956 to 1972, the Tribunal awarded an annual per person amount of $4,500 for each of those 16 years. For the remaining 17 years, preceding and following that period, the annual amount is $3,000.

According to a recent United Nations report, however, the U.S. has been less than assiduous about making good on those meager payments.

October 3, 2012

The Purpose Server

The tri-winged Barling Bomber was one of the most notorious military boondoggles of the 1920s. The exorbitantly expensive plane, which never made it out of prototype, was knocked for being ludicrously slow despite being equipped with an unprecedented six engines. It was a prime example of what happens when designers feel obligated to respond to the demands of bean counters (PDF):

At the close of World War I, the Army owned Liberty aircraft engines far in excess of its airframes. Consequently, Congress mandated that the World War I surplus be used before the service could purchase new equipment. The Barling was one of many aircraft that featured government-furnished engines. The Barling’s wingspan of 120 feet (the exact distance of the first sustained heavier-than-air flight and longer than the B-17’s wingspan of 104 feet) made it unwieldy and underpowered, yet it needed only 320 yards to take off. The maximum speed of 96 miles per hour and range of 170 miles were far less than Army-aviation enthusiasts had hoped to achieve with the design. Initially costing $375,000, the aircraft carried a final price tag of $525,000, excluding its special hangar, which cost more than $700,000.

On the plus side, the Barling inspired some pretty heavy-metal art in its day.

October 2, 2012

The Persistence of Myth

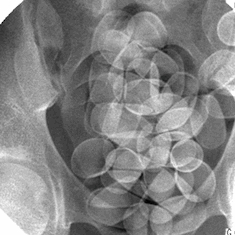

It has become an article of faith that the illicit drug business is every bit as sophisticated as its Fortune 500 counterparts. But a closer look at the industry’s transportation practices reveals some definite scientific shortcomings. As this Dutch study of drug-courier techniques demonstrates, trafficking networks continue to employ concealment practices that have long been discredited. Case in point:

It has become an article of faith that the illicit drug business is every bit as sophisticated as its Fortune 500 counterparts. But a closer look at the industry’s transportation practices reveals some definite scientific shortcomings. As this Dutch study of drug-courier techniques demonstrates, trafficking networks continue to employ concealment practices that have long been discredited. Case in point:

In this 44-year-old man, end-on coin was found along with rectosigmoid bolitas. Some traffickers have mistaken belief that coins or other metallic objects will degrade image sufficiently to make bolitas invisible [to X-rays]. In fact, coin is positive indicator; every case (n = 35) found with internal coins was positive for contraband.

After years of feedback regarding the ineffectiveness of this technique, why do drug traffickers keep using it? Perhaps it is because, unlike in legit enterprises, those at the top of drug-trafficking organizations have zero incentive to care about the fates of their lowest-level employees. There is no possibility of a class-action suit by wronged mules, after all, so why even bother paying attention to evidence regarding the efficacy of smuggling tricks? Enough get through to keep the profits rolling in. Unparalleled success breeds laziness.

An illustrated summary of the Dutch study is available here.