Brendan I. Koerner's Blog, page 18

July 18, 2012

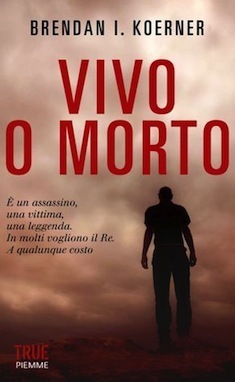

Vivo o Morto

Not sure how many Italian speakers I have in the Microkhan fold, but I felt the need to give some love to this new edition of Now the Hell Will Start from Milan-based Edizioni Piemme. I was tasked with approving the text, a job that gave me a new appreciation for the art of translation. I don’t speak a word of Italian beyond the standard food-related stuff, so I spent a good deal of time slotting phrases into Google Translate. And again and again, I was struck by how gorgeously the translator managed to transpose sentences into her native tongue. There is no greater example, perhaps, than the book’s very first line, which in English reads like this:

Not sure how many Italian speakers I have in the Microkhan fold, but I felt the need to give some love to this new edition of Now the Hell Will Start from Milan-based Edizioni Piemme. I was tasked with approving the text, a job that gave me a new appreciation for the art of translation. I don’t speak a word of Italian beyond the standard food-related stuff, so I spent a good deal of time slotting phrases into Google Translate. And again and again, I was struck by how gorgeously the translator managed to transpose sentences into her native tongue. There is no greater example, perhaps, than the book’s very first line, which in English reads like this:

It is best to use discretion when confronting an emotionally shattered man, especially if he’s holding a semiautomatic rifle.

The Italian version, by contrast, starts things off in much more elegant fashion, by creating a repetition that ratchets up the tension:

Bisogna usare molta cautela. Quando si affronta un uomo sconvolta, soprattutto se imbraccia un fucile semiautomatico, bisogna usare molta cautela.

(One must be very cautious. When facing a distraught man, especially if he is wielding a semi-automatic rifle, one must be very cautious.)

I also love the fact that they reworked the title as Vivo o Morto, which sounds like one of Sergio Leone’s unproduced screenplays. Plus it gives me something to discuss with Tom Clancy should we ever meet at a cocktail party.

July 17, 2012

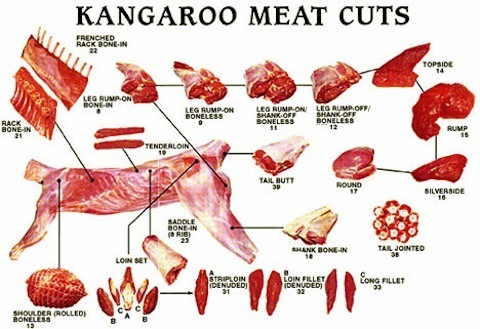

Hopping to Oblivion

The Jenga-like nature of markets is revealed in the tale of Australia’s kangaroo-meat crisis. There was a time when steaks and chops taken from Down Under’s most celebrated marsupials seemed destined to become a staple of butcher’s shops the world over. No country developed a more ravenous appetite for kangaroo meat than Russia, which came to account for 70 percent of the global market. Then, in 2009, Russia abruptly decided that it wasn’t cool with the hardscrabble ways in which the meat is produced. (See here for the first-person account of an Outback ‘roo shooter.) The Russian ban has yet to be lifted, to the great distress of Australian producers who claim they’re on the edge of extinction.

So what is the solution, other than coaxing Russia to start eating ‘roo meat once more? Sausages:

Tapping new markets for roo meat is seen as the best solution to help the struggling industry and deal with the overpopulation of kangaroos.

John Kelly, Australian Kangaroo Industry Association chief says top quality cuts of kangaroo meat – like steaks – continue to be exported to over 50 countries.

Mr Kelly says the problem is selling what is termed manufacturing meat – like sausage mince – from kangaroos.

“What we desperately need is for these other meat cuts to find a new market, as this is what the Russians were buying,” he said.

This presents a fascinating marketing challenge: How do you convince consumers to not only start eating a meat that is strange to them, but also one that is so low-grade that it must be mashed up into a tubular concoction rife with herbs and spices? And how do you compete on price against industrial meats like beef and pork? Roaming around the Outback with a rifle is labor intensive, and thus expensive.

Leave your ideas for kangaroo-sausage ad slogans in comments.

July 13, 2012

The Roles We Must Play

Like many a non-fiction nerd whose tastes run toward the sinister, I was enraptured by Richard Lloyd Parry’s People Who Eat Darkness. The book’s central narrative was compelling enough—a young British woman’s disappearance set against the backdrop of Japan’s hostess-club industry. But what really makes the work sing is Parry’s exploration of media drama, and how so much of it is based on unspoken codes of conduct. Just like Roppongi hostesses and their salarymen clients, who instinctively know which sexual lines can never be crossed, reporters and distraught subjects are expected to fill pre-determined roles on the public stage. And as People Who Eat Darkness makes clear, we detest those who refuse to play along:

In Britain, just as in Japan, powerful conventions govern the way that people under the load of unbearable stress are expected to behave in public. We like our anguished victims to be passive, confused, and broken; where those characteristics are absent, suspicion flourishes…

A Japanese family, deprived of their daughter in sinister circumstances, would shuffle before te cameras with downcast eyes. Their words would be halting and few. They would express love for their child, anxiety for her safety, and appeal to the good nature of her abductors to give her back. There would be tears, and even apology, or something close to it, for “causing inconvenience” by their plight…

In Britain, there is a little more room for the expression of individual anger and resentment, but only within limits. An unspoken code governs people in these situations, as strict in its was as old formalities of mourning.

Parry then describes the first press conference held by the father and sister of the abducted girl:

The photographers were crouching, lurking at the bottom of the podium, their lenses angled upwards. They were waiting for the shot that would make the following day’s papers: a finger brushing away a tear, a face crumpled with anxiety and despondency, even just the clenched hands of father and daughter. But there was nothing of the kind.

The press and public did not like this refusal to obey convention one bit. They found it unsettling, argues Parry, for it stripped us of our chance to feel the catharsis we so desperately crave. By refusing to break down on the podium, these family members took away our theater. And so we punished them by treating them as partly responsible for young Lucie Blackman’s bitter fate.

Read the whole book for more; it also includes a great thread about the marginalized culture of Koreans in Japan, and how the burden of “otherness” might have affected the development of the tale’s villain (pictured above).

Oh, and Parry is also the writer behind one of my all-time favorite Granta stories, “What Young Men Do.”

July 12, 2012

You Love Me for This

The above photo of Charles Bukowski on French TV, snapped by the Sophie Bassouls, is everything that we’ve come to expect of the so-called “laureate of American lowlife.” Yet for me, the image does not call to mind a scene from one of Bukowski’s stories or poems, but rather the wisdom of a less-noted public intellectual: Ozzy Osbourne. For it is Ozzy who, in his VHI “Behind the Music” episode, best summarized the feedback loop that keeps otherwise intelligent celebrities on the path to self-destruction:

If you went to you job in an evening dress with a Nazi hat on, drunk as a skunk, they’d say, “What are you doing, man?” But if I turn up [like that], they go, “Ah, should be a good night tonight, Ozzy’s up it tonight!”

This is the line I always think of when another talented artist falls into an early grave due to drugs or drink. How can we be terribly surprised when we offer them our warmest adulation for being their most bonkers?

(Image via Everyday I Show)

July 11, 2012

The First Touch of Pressure

Sorry for the radio silence today. Working on the publicity questionnaire for my long-discussed next book, which means the light at the end of the tunnel is getting a notch brighter. Back tomorrow with deep, deep thoughts on self-destructive celebrities.

July 10, 2012

Good Luck, Mr. Atayev

Turkmenistan’s National Space Agency has a new chairman, who will be expected to oversee the monumental task of launching the country’s first satellite. I’m still not entirely clear on why Turkmen dictator Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedov is making this such a huge priority, for the official explanation is gobbledygook: the satellite, the nation’s state news agency tells us, will be “designed to promote the development of space technology and modern telecommunications systems and the creation of regional innovation zones.” But suffice to say that the new space tsar, Alladurdy Atayev, will be under intense pressure to get the job done, regardless of its usefulness.

If Vegas was taking bets on whether Atayev will still have his job on launch day, however, I would bet a fortune on the negative. As evidenced by his recent handling of Turkmenistan’s bread crisis, President Berdimuhamedov is not a patient man:

In response to price rises and diminished harvest, Berdymukhamedov has fired Agriculture Minister Merdan Bairamov and Association for Bread Products Chairman Yeldash Ashyrov, the State News Agency of Turkmenistan reported on July 6.

A loaf of traditional white state-baked bread that formerly cost 1 TMT (35 US cents) now sells for 1.6 TMT (58 US cents). Privately baked bread and other baked goods also went up in price 30%.

Never mind that such price fluctuations are probably attributable to such uncontrollable factors as climate, demand, and transportation costs. Like most dictators who surround themselves with obsequious dolts, Berdymukhamedov seems incapable of grasping complexity. Which makes me think he will be none-too-pleased when he inevitably hears that his precious satellite might be slightly harder to launch and operate than his private jet.

July 9, 2012

The Accidental Challenge

The French photographer Marc Garanger, best known for his 1960 series on Algerian women, began his career while serving in the army. He was assigned to Algiers in 1960, right as France was beginning to accept that the jewel of its North African empire was fated to achieve independence. The inevitably of this outcome caused Garanger’s superiors no shortage of bile; one bitter commander, in particular, accidentally motivated Garanger to commit himself to making art that vibrated with empathy:

When the army forced villagers to abandon their homes and to build new ones around the French army’s barracks, Garanger’s commander asked the photographer to catalog all villagers to produce mandatory ID cards. “In 10 days I took 2000 images,” Garanger tells BJP. “The first days the portraits I took showed the women with their veils on. When I showed the image to the commander, he asked for the veils to be removed.” It was, for the photographer, yet another colonising move from the French army, echoing, he says, Edward Curtis’ images of Native Americans. “I felt it was a similar story. Curtis took images of a people being massacred by another. I wanted to show the violence of this war, not physical violence, but the violence imposed on these women.”

Upon seeing the final images, Garanger’s captain suddenly stood up screaming: “Come see, come see how ugly they are. They look like monkeys.” Upon hearing this, Garanger swore he would spend the rest of his life proving his captain wrong.

More from Garanger’s Algerian series here. It’s a collection I’ve been looking at a lot as I plow through the second draft of my next book.

July 5, 2012

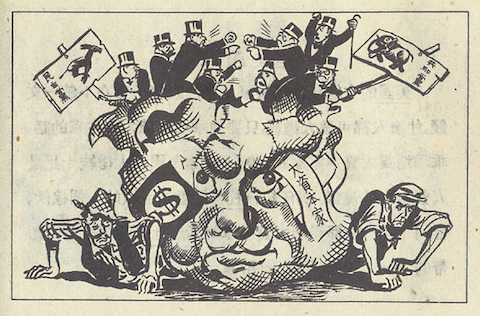

How They Saw Us, Cont’d

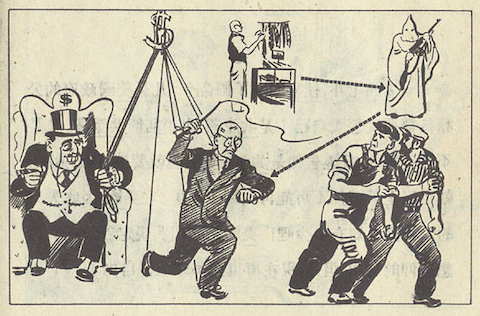

Quite some time ago, I posted about classic Soviet animation that hilariously stereotyped America as a Darwinian nightmare. As someone who grew up thinking that life in Moscow was accurately portrayed by that Wendy’s fashion show commercial, I was strangely pleased to learn that my Soviet peers were similarly duped into thinking that human happiness was utterly absent on the Cold War’s opposing side.

But the Soviets were not the only ones to produce hyperbolic visions of American dysfunction during the last century. This Chinese propaganda pamphlet, part of a stellar collection of such materials, makes the ostensible Leader of the Free World seem like the vilest dystopia ever. The images are ludicrously over-the-top, though not without a microscopic grain of truth on occasion. A few more favorites after the jump.

Check out the whole pamphlet here, and the whole rest of the Center for Research Libraries collection here.

July 3, 2012

The Streets Ain’t Paved with Gold

There is a common and compelling narrative regarding the power of immigrant remittances: A busboy or chambermaid supports their entire native village by wiring money back home. We love these stories because they affirm the economic superiority of our circumstances, as well as the continued robustness of the American dream—through gumption and hard work, anyone can earn a relative fortune on these shores.

Yet as is always the case, the reality of the situation bears only a passing resemblance to the likable myth. Immigrants often chafe at the demands placed upon them by their relatives back home; they find it difficult to provide as much money as requested, and the resulting feuds can lead to the fracture of familial bonds. This excellent study (PDF) of Somali immigrants in Southern Maine drives that point home, particularly in this account of a young woman’s burden:

According to Somalis in Lewiston, one of the reasons that pressure on those living in the diaspora to send money to their relatives is so great is because people living in and around Somalia do not understand how difficult it is to earn a decent living in the West. Kaltun, whose mother and close relatives live in Ethiopia’s Somali region, says that she tries to send as much money as she can as often as she can. She recalls, “I once sent my mother $300 and she refused to take it, saying it was too little. I could live on that much money! It is more than 2500 birr [in Ethiopian currency], and a Doctor’s salary is 500 birr… [But] she has twelve people living with her (four children of her brother who died and seven grandchildren and one other [child of one of her siblings]. I am the only child who is outside, so she depends on me, but she thinks that I have more money than I really do. I want to bring her here to show her how we live. She won’t want to stay. But at least she will see how difficult it is for me. I worry so much, I have so much stress about being able to earn enough money that I have gained a lot of weight. If I went back I would lose it I am sure.”

It will be interesting to see whether that sort of stress convinces some Somalis to return home, as this group is now urging members of the nation’s diaspora. Things do seem to be looking up in Mogadishu, after all. Whichever returnee from Maine establishes the first lobster shack at Lido Beach could make a fortune.

(Image via Bates Magazine)

July 2, 2012

“That’s Some Big Hole You’ve Got There”

Thanks a million for your patience while I was up in Maine, hacking away at the book and knocking back a whole mess of these. Catching up on a zillion different things today, then back tomorrow with a post about Somali immigrant remittances.