Tiago Forte's Blog, page 23

December 14, 2020

Tiago’s 2020 Year-End Review

As I start writing this year-end review, the latest in a long line of year-end rituals, I’m filled with an overwhelming sense of gratitude. Even more than usual. In 2020 so many people around the world got sick, lost their jobs or businesses, or their lives. I want to start this ritual grounded in that reality, to never forget how lucky I am to be here at all.

What feels strangest about the year of COVID is how little it affected us. I don’t quite know what to make of it. The business thrived as millions flocked to online education. My work took off as the concept of a “Second Brain” caught fire. No one close to me got sick, much less had serious complications from COVID. Many of them actually seemed to benefit in many unexpected ways, from having more time to spend with their kids at home, to working in industries that have seen surges in demand during lockdown. Privilege isn’t just about having extra advantages, it’s about having built-in protection against disadvantages.

The biggest change of the year for me was of course the birth of our son Caio. He is just about 2 months old, and I’m still very much grappling with the aftershocks of this momentous life event. What’s clear so far is that he’s prompted a complete inversion of the principles by which I organize my life. I’ve had to go from optimizing completely for my own needs and goals, to optimizing for his. I’ve had to switch from a long-term planning horizon to a very short one, about the time between his dirty diapers. My focus of investment has gone from myself and my skills to his growth and development. And of course, I’ve had to give up all kinds of control – over my time, my sleep, my meals, my free time – in favor of being available for whatever he and Lauren need.

It’s become very clear to me that becoming a “family man” is a decision. It doesn’t happen automatically just because you have a kid. It’s a distinct identity shift that I think has to be by choice. My intention for this year-end review is to lay the foundation for my shift from a work-obsessed to a family-centric life, with my son and wife at the center of my universe. I want everything else in my life to be in service of them, simply because nothing else matters as much as them.

I want to start as I always do, by recapping our successes this year and revisiting the goals I set at the beginning of the year to close the accountability loop.

Signed a book deal for Building a Second Brain

This was the culmination of more than a year of work with my editor and agent. In April my book proposal went to auction between 4 imprints from 3 major publishers, and after a couple rounds of bidding it went to Atria, a division of Simon & Schuster.

It wasn’t quite as dramatic as in the movies, with editors screaming ever higher numbers over the phone in a desperate panic. I wish! Instead, the bids were made in two rounds via email within a 2-hour time window. I sat at my computer staring at my inbox for those two hours as the bids came in. When it was all said and done, Atria won the auction by a wide margin, and I couldn’t be happier to work with them. Read the full story behind the book here.

Recently it was announced that Simon & Schuster is being acquired by the largest of the Big 5 publishers, Penguin Random House, which means my book will be published by the biggest publisher in the U.S. and one of the biggest in the world. That means I’ll potentially have access to more resources and more distribution channels, but it also means I’m part of a much larger portfolio that includes books by heavy hitters like Barack Obama and Danielle Steel. I’ll need to make a real splash to attract the attention needed to stand out among this crowd.

I’m currently working with my editor on the manuscript, which is due July 1, and it will then take around 9-12 months to prepare and distribute the book before its release. I’m expecting it will be available for sale around spring or fall 2022. We currently only have a publisher in the U.S., but are on the lookout for publishers in other countries. Let me know if you know any

December 7, 2020

The Second Brain Manifesto

Ideas are not mere playthings. They are the building blocks of the modern world. Ideas inform our thinking and behavior every day. We depend on new ideas to improve our health, productivity, and relationships. To understand culture, politics, science, and history. New ideas breathe fresh life into how we view the world.

We believe that leveraging the power of ideas requires shifting our mindset from scarcity to abundanceOur society is desperately in need of a new paradigm in our relationship to information. The lens of scarcity, control, and pure consumption is no longer serving us. If we’re going to thrive in this new era, we need to transform information from a source of stress and uncertainty into a source of creativity and abundance. We need to learn how to surf the information wave instead of being drowned by it.

We believe that human progress depends on putting our ideas into actionThe most important factor in our effectiveness, in our impact, and in our future is putting new ideas into practice. But despite all the knowledge we now have access to, it remains as difficult as ever to put it into action – to learn, to innovate, and to develop new ways of thinking and working. Our progress as individuals and as a species depends on our ability to turn our knowledge into concrete results in the real world.

We believe that power comes from sharing ideas, instead of hoarding themThe scarcity mindset of the past led us to hide and protect our ideas. But today, power and influence come from sharing our ideas, not from keeping them secret. Creativity is no longer limited to a select few, but is open to anyone with the courage and dedication to share their work with the world. We can all become creators of the ideas we most want to see manifested in the world.

We believe that everyone has the opportunity to improve their thinking using technologyWe all feel this pressure to constantly be learning and improving ourselves, but so much of what we consume doesn’t get preserved in any form. With the rise of modern technology, we all now have the opportunity to outsource the job of “remembering” to computers and even use them to enhance and amplify our thinking. Now that we have “tools for thought,” we are free to dedicate our minds to the creativity that only we are capable of.

We believe that building a Second Brain enables us to develop our First BrainFar from making humans obsolete, better tools for thinking will free us to invest in ourselves. A Second Brain takes over the burden of remembering facts and details, so we are free to imagine, to create, and to enjoy our lives. The ultimate purpose of a Second Brain is to put our ideas to work for us, so we are free to live a more fulfilling and meaningful life.

Subscribe below to receive free weekly emails with our best new content, or follow us on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, or YouTube. Or become a Praxis member to receive instant access to our full collection of members-only posts.

The post The Second Brain Manifesto appeared first on Forte Labs.

November 24, 2020

Introducing the Keystone Course Accelerator

“Honestly, I feel like more people should know about you and your content.”

That’s how the email from a guy named Billy started.

It was April 2019, and I was at a crossroads.

I had been teaching my Building a Second Brain course for a couple years at that point. I’d had success, but the workload was totally unsustainable.

I was burnt out trying to do everything myself, from incessantly promoting the course to teaching all the lessons to answering customer service questions late into the night. The course I had created was consuming me, and I didn’t see any way out.

I knew that I either needed to turn my little program into a full-fledged online education business, and build the team and the support systems I needed, or risk burning out completely and losing all the progress I’d made.

I longed to get back to the original reason I’d started working for myself: to have more control over my time, my income, and my destiny. To have the freedom to pursue whatever interested me, and to work when and where and how I chose.

I’d lost sight of my ultimate purpose: to make a positive impact on people’s lives without sacrificing my happiness, quality of life, or integrity.

Billy explained that he was a marketing consultant for online course creators. He wanted to talk to me about potentially working together to grow my business.

I receive a lot of this kind of email, but as my finger hovered over the “delete” button, his name caught my attention: Billy Broas.

Hadn’t I seen this name before?

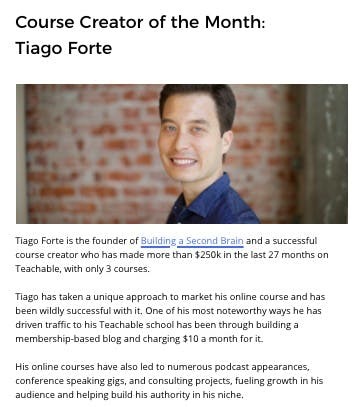

I searched my email and lo and behold, he’d been featured in Teachable’s newsletter just a couple days before right alongside me:

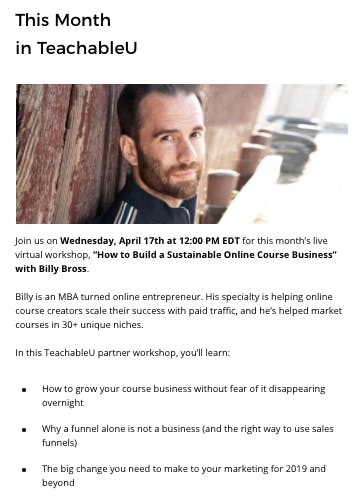

He was hosting a workshop on “How to Build a Sustainable Online Course Business,” which had piqued my attention. I saw that he was the only marketing consultant recommended by Teachable, the learning platform I use for my courses.

Needless to say, I replied to Billy’s email instead of deleting it:

“I’d love to have a call. I’ve been thinking for some time that it’s time to expand the marketing for BASB and my other courses. It’s becoming a full curriculum for how to work in the digital age and I think a lot more people could benefit from it than my own audience I’ve been focusing on.”

The phone call we got on a few days later would change my work, my business, and my life in more dramatic ways than I could have possibly imagined.

I decided to join Billy’s 10-week Course Accelerator program a couple months later. It was a group coaching program in which he taught course creators a scalable system for not only selling their product, but doing so in a repeatable, sustainable, and classy way.

Alongside Billy and a group of other impressive participants, I learned more about online marketing and persuasive psychology in 10 weeks than in the previous 6 years of solitary trial and error combined.

I realized that what I thought of as “marketing” was really a corrupted version of true marketing, based on the worst excesses I’d been exposed to. True marketing is about deep empathy and connection with others. So much so that when done well, we don’t call it marketing at all. We call it “sharing” or “storytelling” or “coaching.”

With that realization, the mindset of scarcity and anxiety around “selling” that was severely constraining me and my business completely dissolved, and was replaced by a philosophy based on generosity and abundance.

We focused on two main efforts: Building an engine to convert more of my audience into paying customers, and then pouring more fuel into that engine.

Over the next year, using the system that Billy and I architected together, I grew my email list from 6,000 to 38,000 subscribers.

And that drove my course launches from a previous high of $39k to a recent record of $985k.

Those aren’t results that happen by accident. They don’t just show up on your doorstep overnight.

It takes a system. But not the super complicated “sales funnels” or scammy ad campaigns you see influencers bragging about. Those “tactics” make everyone involved feel slimy afterwards. They aren’t consistent with creating a reputation you are proud of.

It takes an extremely high level of integrity combined with the fundamentals of storytelling: an email list you control, a deep understanding of the problems your customers are facing, a compelling story about what you can do for them, authentic testimonials and proof to back up your claims, all delivered in a consistent format with a clear invitation to join you.

It’s no secret that I’ve long wanted to create a program on how to successfully launch courses like mine. I’ve now launched three separate courses by three different instructors into the six-figure range, and have seen what a transformative impact they’ve had on the students and instructors alike. But my own course is growing so fast that it takes all my attention. Not to mention that I became a parent last month

November 16, 2020

The Dawn of Personal Documentaries: Democratized Storytelling in an Age of Narrative Disruption

I recently discovered a treasure trove of family home videos stretching back almost 40 years.

The earliest video was from my parents wedding in 1981 in São Paulo. The footage was grainy and barely in color, and looked like it was taken by a professional crew. Consumer camcorders hadn’t even been invented yet.

The more than 100 hours of video went on to document my birth and childhood in Southern California, me and my three siblings’ early years through the 80s and 90s, right up until our recent family vacations, birthdays, and holidays. Thousands of precious memories meticulously documented across four decades of life.

The first commercial consumer-grade camcorder, the Sony Betamovie BMC-100P, was released in 1983. It ushered in a revolution in collective memory. For the first time ever, families around the world could afford to document their lives in video form. College TV studios could teach film classes, and amateur video hobbyists could produce full-length films at a reasonable cost.

The Sony Betamovie BMC-100P, the first consumer-grade camcorder

The Sony Betamovie BMC-100P, the first consumer-grade camcorderBut after this initial surge in innovation, the field of consumer video recording stagnated. Most of these recordings remained stuck in obsolete formats lost in storage. As consumers we’ve lacked the tools to edit our footage together into a coherent story, and to share it in ways that fit into our busy lives.

This has always made the title of “filmmaker” a very rare and exclusive position. You need expensive equipment, and a crew to carry around and operate it. You need a dozen specialized kinds of expertise, which demands a sizable budget. Making a film has required the vision and leadership of a CEO combined with the attention to detail and technical expertise of an engineer.

Until now.

The technological boundaries that long separated amateur “home videos” from professional movie-making have become increasingly blurred, and even erased.

Through the Internet and social media, we all now have access to a global distribution system unprecedented in human history. Our smartphones have capabilities until recently reserved only for the highest end professional cameras. Our computers are multimedia studios equipped with the same software used by Hollywood studios.

The latest Apple iPhones are the first smartphones to come equipped with Dolby Vision, a technology used by top Hollywood filmmakers for blockbuster feature films.

We are in the midst of a revolution in personalized filmmaking as people awaken to the power of the tools they have access to. It is a narrative renaissance, connecting us back to our deep roots as storytellers out on the primordial savannah. Except this time, unshackled from the limits of space and time.

We are seeing the rise of “personal documentaries” – long-form, personal, narrative-driven videos told through a particular perspective, combining the objectivity of traditional documentary filmmaking with the intimacy of social media.

Most of us have gotten used to sharing small snippets of our lives with our social media networks – an Instagram story of a meal we’re having, a Snap of a fun moment with friends, and maybe even a YouTube video about something interesting we’ve learned. The natural next step is to start to combine these snippets into longer, richer, more engaging and meaningful stories.

A convergence of technological trends is making this kind of synthesis possible for the first time:

Professional-quality smartphone-based cameras (with software-based features like motion stabilization, exposure control, and augmented reality that once required expensive hardware)Plentiful storage space with solid-state memory and cheap cloud storageMobile chips and apps that can handle sophisticated editing right on mobile devicesProsumer software available as an affordable monthly subscriptionSocial media networks designed specifically for video, with options for monetization (including YouTube, Vimeo, Twitch, Patreon, and Onlyfans)Consumer UX design influencing professional video-editing tools, making them much more user-friendly and intuitiveMore powerful consumer computers that can run editing software without requiring high-end upgrades I made this short video about my trip to the Living Computer Museum in Seattle completely on my iPhone, including splitting and combining different clips, audio and video transitions, and text captions. I happened to capture the unveiling of the first working Unix version 0 computer in at least 45 years.

I made this short video about my trip to the Living Computer Museum in Seattle completely on my iPhone, including splitting and combining different clips, audio and video transitions, and text captions. I happened to capture the unveiling of the first working Unix version 0 computer in at least 45 years.Traditional documentaries are films that “document reality, primarily for the purposes of instruction, education, or maintaining a historical record.” Now that we all carry high-resolution cameras with us at all times, documentation is becoming a part of everyday life.

But because the videos we record are personal, they also blur the line between fact and fiction. The goal is not to create a factual record for the history books, but to share an event, a story, or a cause from our personal lives, through our own lens.

I discovered in my own personal documentary film project, on the life and artistic career of my father Wayne Forte, that I could completely change the meaning of a scene through editing. Sometimes the difference of one or two seconds in the placement of a cut could shift it from sad to hopeful, harsh to sarcastic, deceptive to authentic. I quickly realized that there was no “objective” version of events – the narrative had to be crafted, not just captured.

Video is a uniquely powerful medium because it is immersive, while also being shared. It engages both the visual and auditory senses across large numbers of people in a synchronized way, just like the real world. It touches us on an emotional level, allowing us to see through others’ eyes and walk in their shoes.

Personal documentaries use stories – the basic unit of meaning for humans – to inspire, educate, entertain, and change perspectives.

Narrative disruptionWe are living in a time of “narrative collapse.” The “big narratives” told by governments, traditional media, and other large institutions that have always been the guiding pillars of society have broken down.

A new generation of “small narratives” are emerging to take their place. Just as startups “disrupt” established companies in the business world with simpler, more innovative products, these “narrative startups” disrupt official narratives with more tailor-made, flexible stories that react much more quickly to every news cycle.

This fragmentation and loss of a grand narrative has mostly been framed as a negative trend. We’ve clearly seen the impact of filter bubbles and conspiracy theories, as people grasp for any sense of coherence. But I see a silver lining. We have the chance to equip people with the tools to write their own stories, in their own way, through their own lens.

The short-form videos that have exploded across YouTube, Snapchat, Instagram, and TikTok in recent years represented the first wave of democratized video. They’ve demonstrated a stunning level of creativity, but also revealed the pitfalls of “contextless” storytelling.

Clips taken on the street are edited to inflame passions, and spread around the world in hours. Soundbites are extracted from interviews and spun to misrepresent someone’s position. Stripped of their context, these clips lose the details that might give nuance to the story of “what happened.”

I see personal documentary filmmaking as the rebuilding of that context – weaving together a new story about what happened and what’s happening out of bits and pieces of audio and video. It won’t return us to a single, “official” narrative that everyone agrees on. That narrative has shattered into a million fragments. The rebuilding has to take place at the individual level, as we each put the pieces back together in a way that makes sense to us.

Personalized filmmakingThe democratization and personalization of video-making is part of a much broader trend.

Computers became personal computers. Productivity became personal productivity. Finance became personal finance. And of course, knowledge management is evolving into personal knowledge management.

As each of these disciplines have become miniaturized, democratized, and customized down to the level of a single individual, they have unleashed both daunting challenges and priceless opportunities. I believe the tools of filmmaking are crossing a similar threshold.

They will allow us to answer new kinds of questions:

What will happen when people are given the opportunity to tell their own stories?What hidden narratives will come to light once the gatekeepers don’t get to decide what stories are worth telling?How will flows of money, attention, time, and effort be shaped and redirected once those stories are free to emerge?What will people pay attention to and how will they live once they have an abundance of stories to choose from, not just a few?What new professions and even industries would arise if we saw storytelling as a practical craft, with principles and rules and models?When you change how you pay attention, the things you pay attention to change. Filmmaking is nothing if not the ability to shape how others pay attention. I suspect that that ability is one of the most powerful untapped sources of change in the world today.

What kinds of films could we make?Here are a few ideas for how personal documentaries could be used, including examples:

Personal autobiographies could be a way of transforming trauma into healing, by allowing people to retell their own stories as victors, instead of victims. They could be empowered to highlight everything that is beautiful and worthy in their lives, even if they’ve experienced terrible abuses. Sharing one’s story can be a powerful route to healing.

In Unrest, Jennifer Brea tells her own story of dropping out of Harvard due to Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (commonly known as Chronic Fatigue Syndrome), and going on a journey to diagnose and understand a condition that none of her doctors recognize. She created it largely while bedridden, collecting the stories of others she found online suffering from the same condition. This film morphs from patient history to advocacy as Brea realizes that millions of people around the world suffer from this misunderstood disease.

You can watch the trailer below, and the full film on Netflix or Amazon Prime Video:

Personal dramatizations could be used to recreate scenes from the distant or recent past, allowing others to feel what it was really like to be there. We could develop deeper empathy for the victims of the Holocaust, or the activists of the U.S. Civil Rights Movement, or the victims of the Massacre at Wounded Knee, or any event that played an important part in the historical consciousness.

The Battle of Orgreave is an hour-long film by Mike Figgis on the 1986 reenactment of a clash between striking miners and police during the Great Miners’ Strike of 1984-5. Although it pre-dates smartphones, and is closer in production quality to a home video, it illustrates how we can relive parts of our history and document those recreations for future generations using video.

Personal nature documentaries could show the impact of climate change not just on distant, exotic locales like glaciers or the rainforest, but on the closest local environments. Imagine the impact of a documentary showing how the forests, streams, coastlines, and animal species you see every day in your own town are already suffering from climate change.

In Learning to See: The World of Insects, Jake Oelman documented the life and second career of his father, psychologist-turned-photographer Robert Oelman. While telling the story of how his father moved to the rainforest to become a nature photographer, he also tells the story of his father’s main subject: insects. Endangered and underappreciated, these tiny creatures represent one of the most important fronts in the climate change crisis. By mixing the personal with the universal, Learning to See pulls viewers in from both sides.

Watch the trailer below, and rent or buy it on Apple iTunes:

Personal biographies could document the lives and work of important figures in your local community. There is a vast swath of people who have had a major impact on their community, yet aren’t famous enough to attract a big budget film project. Capturing their stories could help us understand where we came from, how much people sacrificed to give us the lives we have, and inspire future generations of leaders, activists, scientists, entrepreneurs, politicians, and more.

In My Brother Jordan, filmmaker Justin Robinson set out to document the life of his brother Jordan, who had passed away due to cancer. The film is made up of more than 100 interviews with family and friends who knew Jordan, plus excerpts from many hours of home videos. In other words, it used personal relationships, existing media, and affordable equipment to tell a personal story that has been viewed almost 10 million times.

Personal advocacy could see important social issues highlighted in a new way or from a new angle. Imagine watching the story of a teenager struggling with the decision of whether to get an abortion. Or a small business owner trying to stay afloat under the crush of burdensome taxes. All points along the political spectrum deserve empathy, even if you don’t agree that they deserve priority. I think it would help us understand each other more if we understood the stories that led us to where we are today.

Backstage Capital – jOURney tells the story of up-and-coming venture capital firm Backstage Capital, founded and led by Arlan Hamilton. Backstage is on a mission to invest in companies led by women, People of Color, and LGBTQ founders, who typically receive less than 10% of venture funding. Made during the COVID pandemic, it is clearly compiled mostly from amateur footage shot on subjects’ personal smartphones. But it manages to effectively both tell the remarkable story of the firm’s and founder’s trajectory so far, and also advocate for the wider industry to invest more in minority founders.

Personal futurism could be used by individuals or businesses to tell stories about how the future could be. Imagine how much more effective it would be to persuade people to invest in a certain future for a business, product, team, community, or neighborhood if you could portray viscerally “what it will be like” to build that park, invest in that district, or fund that public transport line. We could multiply potential futures, test them out, and compare them against each other using the closest thing to virtual reality that exists on a wide scale, which is video.

This 6-minute YouTube video SpaceX’s Starlink: Global Internet Begins explains the background of the satellite-based internet service called Starlink, currently being launched by space launch company SpaceX. By providing a window into how such a service would function, how it would look, and what it would cost, this video gives viewers a chance to think through the many implications it would have on every aspect of society.

Telling our story

My mom and I decided to make a highlight reel of the best moments from our archive of home videos.

The footage was valuable because she’d captured everything, but that very fact meant that the gems were difficult to find. There were hours of video documenting entire soccer games, or babies sleeping for 30 minutes straight, or school plays in which we barely appeared. There was far too much footage to watch in any reasonable amount of time.

My mom shipped the recordings – which included everything from disks to cassettes to solid state storage to ancient VHS tapes – to a home video digitization service called iMemories. Within a few weeks they were all converted into digital format and uploaded to a website where we could watch them on demand, like a private YouTube channel.

[image error]The gallery view of the home video digitization service iMemories.From there, I started watching the videos one at a time, downloading the best of them onto my computer, and importing them into Adobe Premiere to start making edits. I hope to have the first in a series of highlight reels ready by the end of the year, for us to watch together as a family over Christmas.

As I watched video after video, it struck me that our family has a story. It might not mean anything to anyone else, but it is priceless to us. It is the story of where we come from, how we became who we are today, and the moments along the way that were most meaningful. It is a story that I want to be able to share with my children and their children. And with the gifts of technology, I will now have the ability to do so.

The power of immersive, visual storytelling is too great for anyone to ignore. It is the power to change people’s perception of reality, which might as well be reality itself.

The ability for anyone anywhere to tell any story and distribute it instantly for free around the world is as revolutionary as the printing press.

No one is immune.

No one is too late.

Everyone has a story to tell.

Subscribe below to receive free weekly emails with our best new content, or follow us on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, or YouTube. Or become a Praxis member to receive instant access to our full collection of members-only posts.

The post The Dawn of Personal Documentaries: Democratized Storytelling in an Age of Narrative Disruption appeared first on Forte Labs.

November 14, 2020

My Interview on Noah Kagan Presents: Behind the Scenes of a $5,000,000 Online Productivity Course

I was very happy to receive an invitation to join Noah Kagan, influential online marketer and founder of Sumo Group, on his podcast. I’m officially on hiatus from interviews this year while I write my book, but I couldn’t say no.

I remember back in 2012 when I first arrived in San Francisco to start my career, I asked around for who I should listen to about online marketing. Noah Kagan was (and continues to be) one of the most well-known and influential people in this space. He taught me some of my earliest marketing lessons back then, and I’m proud to be able to join him on Noah Kagan Presents.

This was a WIDE-ranging conversation. We started talking about productivity and Building a Second Brain, but also touched on:

How to figure out what kind of online course you should create

The psychology of high-ticket pricing for courses

How to build a strong brand in a saturated niche

My anger management technique using gloves and a tennis racket (though I wouldn’t called it “management” because that implies anger is a bad thing)

How to shoot a documentary on your iPhone

Listen to the interview below, watch a 15-minute highlight reel on YouTube (though I’m not sure why there’s a picture of Tai Lopez in the thumbnail), or visit the episode webpage.

Subscribe below to receive free weekly emails with our best new content, or follow us on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, or YouTube. Or become a Praxis member to receive instant access to our full collection of members-only posts.

The post My Interview on Noah Kagan Presents: Behind the Scenes of a $5,000,000 Online Productivity Course appeared first on Forte Labs.

November 9, 2020

Announcing the Praxis Fellowship

It is my pleasure to announce the new Praxis Fellowship, a writing residency for emerging thought leaders at the frontier of modern productivity, creativity, and knowledge management.

In December of 2015 I was invited to become a Writer-in-Residence for Ribbonfarm, a niche but influential blog that had made a big impact on my own intellectual journey. I had exchanged a few messages with the Editor-in-Chief of the site, Venkatesh Rao, who offered me the opportunity after seeing my writing on my own fledgling blog.

Over the next year, I would write five long-form essays for Ribbonfarm, in which I developed my ideas on modern productivity. Those ideas had been simmering on the backburner for quite some time. But it was the firm push from someone I looked up to, plus guaranteed distribution to thousands of Ribbonfarm readers, that gave me the confidence to put them into writing.

Those essays became the bedrock of my business, bringing me countless opportunities to collaborate and learn from others. I launched my paid membership off the momentum of those essays, incorporated them into my online course Building a Second Brain, and to this day they still serve as one of the best introductions to my work for newcomers.

I’ve long wanted to offer the same opportunity to promising writers in my field – to give them the exposure and feedback needed to develop new ideas to their full potential. And in the process, nurturing new voices with new ways of seeing things in a field that is sorely lacking diversity. We are living in the midst of an explosion in productivity tools, and my goal is for this Fellowship to push forward and broaden our current thinking on how and why they should be used.

We are welcoming three inaugural Praxis Fellows: Carrie Ben-Yisrael, Frank Anaya, and Christina Luo. All three were formerly Alumni Mentors in our Building a Second Brain course, and we’ve invited them to continue to develop the work they’ve done with our students. They each offer new perspectives that are missing from the conversation about what it means to be an effective person in the world today.

[image error]

Fellows will commit to writing 3-5 essays over the next three months on a topic of their choice, related in some way to the Praxis mission of “exploring the frontier of modern work.” This could include developing a new methodology, introducing a new framework, exploring an unusual angle or approach, or telling an illuminating story – anything that sheds light on the nature of modern work and how to perform it more effectively and mindfully.

They will receive an honorarium, editorial support, and guaranteed distribution to thousands of members of Praxis and Everything, a publication which includes other writers, of which Praxis is a part. Join either one below if you’d like to see what our Fellows come up with:

Join Praxis ($10 per month)

Join the Everything bundle ($20 per month)

Subscribe below to receive free weekly emails with our best new content, or follow us on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, or YouTube. Or become a Praxis member to receive instant access to our full collection of members-only posts.

The post Announcing the Praxis Fellowship appeared first on Forte Labs.

November 5, 2020

Tiago’s 21 Notes for Documentary Filmmaking

Subscribe below to receive free weekly emails with our best new content, or follow us on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, or YouTube. Or become a Praxis member to receive instant access to our full collection of members-only posts.

The post Tiago’s 21 Notes for Documentary Filmmaking appeared first on Forte Labs.

How I Made a Documentary Film with Digital Notes

Over the last year I filmed a short documentary on the life and artistic career of my father Wayne Forte. He has been one of the strongest influences on me, not only as a father, but as a prolific lifelong artist.

I wanted a way to share his remarkable story with a wider public, to preserve a record of his memories for future generations, and to better understand the roots of my own ideas.

I used only the most basic equipment: a smartphone, a microphone, a tripod, a stabilizing gimbal, and video-editing software on my computer. I had no film crew, no expensive cameras, and did no post-production except what I could accomplish on my own.

I had never made a film before. I had no real experience with sound, cinematography, lighting, scripts, interviewing, editing, or any of the dozens of specialities that go into making films. I didn’t even have much of a plan when I started. I simply turned on my smartphone camera and started recording.

It took 16 months, more than 100 total hours of work, and 17 hours of footage from 4 countries, all condensed down to 46 minutes.

The full editing timeline for the final film in Adobe Premiere. Each slice is a different video clip.

The full editing timeline for the final film in Adobe Premiere. Each slice is a different video clip.When I finished the final cut, I premiered the film on YouTube in a coordinated viewing with over a hundred family, friends, and random Internet strangers watching from their homes in the midst of a global pandemic. In the couple months since, the film has been viewed more than 6,000 times by people around the world.

Every part of this story would have been improbable or impossible just 10 years ago. It was enabled by a quiet revolution in our ability to tell long-form stories using video, disguised as a steady stream of hardware and software updates every year.

This is the story of how I did it, what I learned, and the profound implications for the modern creative process I discovered along the way.

The ProjectIn March of 2019 I received news that an art gallery in Los Angeles would be hosting an exhibition of 30 years of my father’s Biblically themed artwork.

This was a huge milestone for him. And not just because it would be a prominent showcase in the heart of Hollywood. He had had a lot of success with his paintings of figures and still lifes, but the secular, mainstream art world had never embraced his religious art, which has long been his true passion.

Here was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to showcase decades of his most personally meaningful work in his hometown. I was living in Mexico City at the time, and decided to fly back to be there.

From there it quickly became a project.

If I was going to fly all the way back to the U.S., I thought, I might as well film the opening night. If I was going to film the opening night, I might as well do a few short interviews with the friends and collectors who would be there.

And if I was going to do all that, why not just film a few other interviews while I’m in town and tell the story of my dad’s career as an artist?

In my productivity courses I’m constantly advising people to “dial down the scope.” In other words, to reduce the size and complexity of their projects so they have a better chance of finishing them.

But once in a while, a project comes along that is so interesting, so unique, and so meaningful that it’s worth dialing up the scope. The main purpose of keeping most projects small is so that when a really special one comes along, you have the time and space to make it big.

I realized that by making this film, I could accomplish a few different goals at once.

It would be an opportunity to learn how to make higher quality, longer videos to promote my work. I’d long wanted to be more active on YouTube, but without a hands-on project, I never seemed to get around to it. I sensed the revolutionary implications of everyone walking around with a professional-quality camera at all times. I knew I needed to get my hands dirty to be a part of it.

I also had a more personal motivation. A few years earlier, my dad had had a cancer scare. Although he was now fully recovered, it had shocked me with the realization that he wouldn’t be around forever. As I looked forward to starting a family of my own, I wanted to document his life so my future kids would have the chance to know him like I did. And to better understand for myself how his attitudes toward art, creativity, productivity, spirituality, and life in general had so deeply influenced my own.

At first glance, this was an absolutely absurd project for a novice to take on.

I had made a few short videos on YouTube, but nothing anywhere close to this scale or complexity. I didn’t have any special equipment, had never used professional video editing software, and didn’t know the first thing about lighting or sound.

But I did have one trick up my sleeve: my system for digital note-taking, which I teach in my course Building a Second Brain. I knew that I could easily manage the information that I’d need to plan, organize, and execute the project using digital notes.

16 months later, on June 2, 2020, my dad’s 70th birthday, I screened the final cut for my family online. We watched it together at a coordinated time, and had a touching conversation afterward on Zoom about our shared memories.

It was truly one of the most special and meaningful moments with my family that I can remember.

A screenshot from my family’s post-screening conversation on Zoom

A screenshot from my family’s post-screening conversation on ZoomA month later I screened the film again for my followers using YouTube’s Premiere feature. I shared the starting time and a link with the subscribers of my weekly email newsletter, and over 100 of them showed up to experience it together.

As promised, I’m finally ready to share what I learned.

From how I managed the whole project using digital notes, to what I learned about interviewing, to what I discovered about creating virtual community, to the future potential of amateur films. I’ll share screenshots of all 21 notes I created along the way, explain how I used them, and give you my best advice on how to make a film of your own.

The role of digital notesThis project simply would not have been possible without digital notes.

From the very beginning, I needed an easy, lightweight way to manage large amounts of information. For example, scenes to shoot, questions to ask in interviews, filming tips, editing guidelines, examples to borrow from, lessons from other films, checklists to follow, and many other logistical details.

There are a few things that make notes uniquely suited to amateur filmmaking:

They are casual, fitting easily into the small moments of the dayThey are multimedia, allowing you to capture text but also screenshots, still frames, pictures of backgrounds or locations, etc. in one centralized placeThey are mobile-friendly, allowing for easy entry and retrieval when you’re out and about filmingThere are specialized software programs available for managing full-scale film projects. But I wasn’t a professional filmmaker and couldn’t afford to dedicate myself full time to the project. I didn’t need a sophisticated tool nor did I want to learn a new interface.

What I needed was a quick and dirty way of making small bits of progress whenever I had the time, approximately 1-2 days per month. Notes perfectly fit the bill.

There were five overlapping stages I moved through in this project:

ResearchPlanningFilmingEditingScreeningLet’s examine the notes I used for each one.

For Praxis members only, click here to download the full content of all 21 notes shown below in Evernote and Notion formats. You can borrow from what I learned, explore how I construct notes, and even use my notes as a template for your own video project.

STAGE 1: RESEARCHI knew right from the start that I would need a lot of exposure to good filmmaking. I had watched many documentaries throughout my life, but now I had a completely different motivation: to borrow the parts I liked and avoid the parts I disliked.

I polled my followers on Twitter and Facebook for recommendations of good documentaries, and within a few hours had several dozen. The popularization of video streaming services has made an endless variety of documentaries available to us at the click of a button. They don’t get as much attention as the latest hit series, but we’ve never had such easy access to the world’s best documentary films. Or as many options for distributing our own.

I put the list of film recommendations into a note, and over the next few weeks drew from this list for my evening watching, instead of the usual endless Netflix browsing. I noted the takeaways from each film below the title using bullet points:

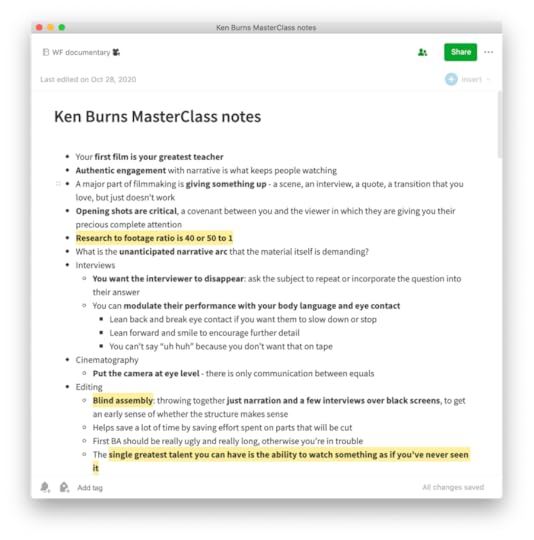

I also decided to take an online course on filmmaking for more structured learning. I was delighted to discover that Ken Burns, one of the filmmakers I most admired, offered a class on documentary filmmaking on the Masterclass platform.

It only took me a couple days to watch the videos and take notes on that course, and I came away with a wealth of practical knowledge and timeless wisdom that Burns had to offer. Here’s a sample of my notes, which I returned to time and again as my experience grew:

From the very beginning of the research phase, I was already capturing footage. I turned on my camera and started filming anytime I was with my family, or when I had some downtime. I experimented with new angles, tried all the buttons, played with all the settings, and played back clips on my computer to see how they came out.

Once I started editing my footage in Adobe Premiere, I quickly realized that I would need to learn how the program works. I watched some free videos on YouTube, but knew that being able to ask questions of someone would help me move a lot faster. I hired a friend of mine, Joshua, to meet with me on Zoom and help me through those roadblocks.

Premiere is an intimidating tool. It bristles with buttons and switches and toggles on every square inch. It is made for professional videographers and filmmakers, and thus offers a staggering array of the most finely tuned capabilities.

Luckily, almost as soon as Joshua and I started going through those options, I realized I would only need to know about 10-15% of Premiere’s features. I had no need for sophisticated video or audio effects, or stitching together multiple camera angles, or adjusting the exposure or color correction (thanks to the iPhone’s brilliant built-in image algorithms).

I only ended up doing three 1-hour calls with Joshua over the course of 6 months, plus a couple other short troubleshooting calls much later when I accidentally messed up my audio tracks.

Here are my notes from our calls:

I also saved a couple notes on potential topics for future exploration, such as how to organize large amounts of footage, how to do video transcription, and tips on how to interview one’s parents.

That was the extent of my research!

In the past, it would have been necessary to dive deep into the technical details of video formats, compression types, frame rates, lighting equipment, audio bitrates, and on and on.

With so much of that complexity now abstracted away behind the lens of my smartphone camera, I was left with far more time for the parts I really cared about: how to ask penetrating questions, how to construct a scene, how to tell a story, how to pack an emotional punch.

Even now, I barely understand most of the technical aspects of filmmaking. It’s simply not needed to get started anymore.

STAGE 2: PLANNINGMy default approach to almost any project is to execute it in a “bottom-up” way.

What does that mean?

Instead of spending tons of time upfront creating detailed plans that might have nothing to do with reality, which would be a “top down” approach, I prefer to start taking action as soon as possible, and then see what kinds of plans emerge organically.

This project was no different. In fact, the very first shot I ever took ended up becoming the opening shot of the film. How’s that for getting right into the action!

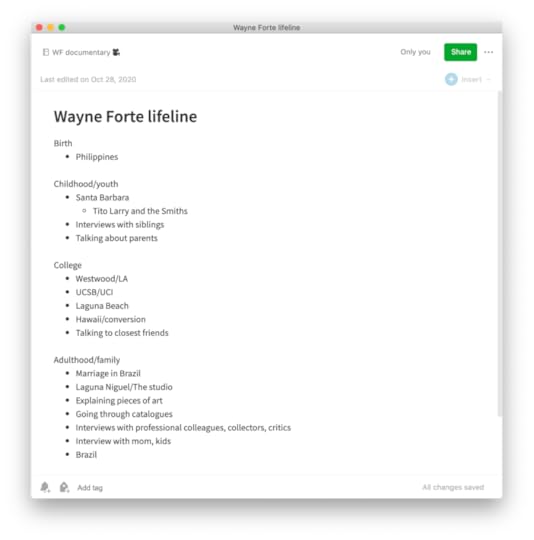

My planning was thus very light, and almost always done in the midst of filming. For example, I made a bulleted timeline of my dad’s life to make sure I was covering each of the major stages.

Even a short, casual list like this one sparked ideas for people I could interview, places to visit, and questions to ask. I then recorded those new ideas in a separate note, so I had a quick reference and checklist of shots still left to take.

Much later on in the editing stage, I realized I could insert photos into my film, using the classic “Ken Burns” effect of slow panning. I whipped up a note with ideas of photos I could look for, which again served as a handy reference as I went through old photo albums.

These quick, lightweight planning methods provided me with a tremendous amount of direction without bogging me down in bureaucracy. The notes I’ve shared above took mere minutes and served as critical touchstones every time I decided to take out my camera.

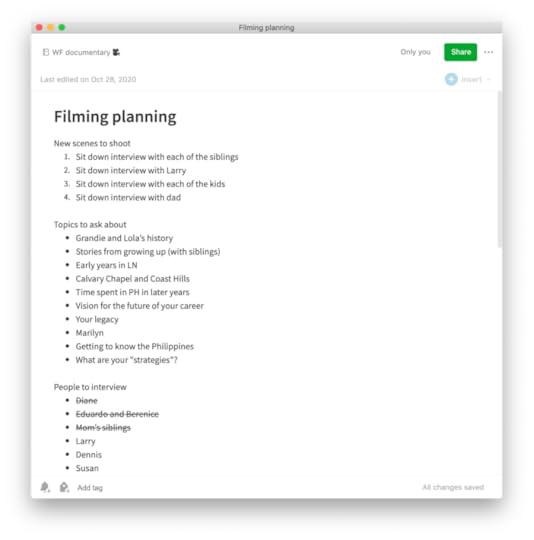

STAGE 3: FILMINGAs I said before, filming was not a specific stage. It took place throughout the project, from the first day I decided to commit to it, to almost the very week it was screened. But I’ll consolidate all the notes I found most useful here to give you a window into how I used them.

Most of my filming-related notes were made up of tips and guidelines to follow. In the heat of the moment, with precious seconds passing by, I needed to be able to look at a single list or risk being completely thrown off track.

For example, I created this note to summarize the most important settings for my wireless microphone, the Zoom H1n.

It includes the “need-to-know” settings at the top, and pictures of the entire manual toward the bottom in case I needed to find an obscure setting. This is a great example of how useful it can be to create a succinct summary of a body of knowledge, while also keeping the full details close by in case you need them.

I made a similar checklist of “filming tips” to run through every time I turned on my camera, to make sure I didn’t miss a critical step.

Similar to filming, I didn’t wait long to start editing. I knew from experience that the best learning would happen when I tried to take one “slice” of raw footage all the way to a final product, so I attempted to do that as early as possible.

And I was right: only by seeing the footage on a large screen, sitting back and imagining how they would feel to an audience, did I gain fundamental insights into how the original footage could be made better.

Things like how long to linger on someone’s face as they’re speaking, where the cut between shots should go, how fast to pan across a landscape to make it engaging but not too quick, how high or far away from a subject to hold the camera, etc.

It’s difficult to put this kind of tacit knowledge into words. Which is why it can only be gained through experience. It’s an endless list of micro and macro-adjustments that no YouTube video or textbook or course could teach me. I had to make every mistake (in some cases several times) to understand these principles for myself.

“...gut feeling is not a mysterious force, but an incorporated history of experience. It is the sedimentation of deeply learned practice through numerous feedback loops on success or failure."

– Sönke Ahrens

Let’s take a look at the notes I used in my editing.

This note of “editing tips” was my checklist each time I sat down to import and edit a new set of clips. It ensured that I was using the same settings each time, organizing the footage in a sensible way, and remembering the decisions I had made previously.

Later I added some further guidelines as I moved into the editing stage as my primary focus, and uncovered some of the more advanced and subtle features of Premiere.

After about 16 months of on-and-off work on the film, I was ready to schedule a screening. I knew I needed a looming date on the calendar to give me the accountability for that final push.

This was in the midst of the initial COVID surge, so I knew it had to be virtual. I did some research on livestreaming platforms, captured in this note, to figure out the best way of sharing the experience across the world.

Eventually I settled on YouTube Livestreaming as the best option, since it was widely supported and familiar to an audience that wouldn’t necessarily be tech-savvy.

And then one day I realized that I could skip the complicated livestreaming altogether, and simply upload the film as a normal YouTube video using an unlisted link. At that point, all I had to do was follow the standard upload guidelines, which I took note of, bolding the parts that were relevant to me.

The virtual premiere ended up being quite an event, with more than 100 family, friends, and total strangers syncing up from around the world. I used this note to plan the event and write the email invite, which needed to explain how to access the screening from a wide variety of devices and which settings to use.

All the information needed to bring my film to completion is contained in the notes above, exactly as presented. It amounts to only 62.5 MB, the size of a large Word document.

This small collection of informal notes is a testament to the incredible leaps filmmaking has made in recent years to make the technology, skills, and knowledge of the craft widely available to anyone with the courage and dedication to make it happen. As well as to the impressive power of digital note-taking for learning new skills and executing creative projects.

Telling the storyToward the end of this film project, I started creating a different kind of note. I saw that the story of the story – why I decided to do this project, what I learned from it, how I did it – was interesting within itself. These notes became the article you’re reading right now.

For example, I saved a research finding that “kids who know more about their family history had a greater belief that they could control their world and a higher degree of self-confidence.” This was the first piece of hard evidence of something I had long suspected: that knowing more about your past can directly impact your present wellbeing.

One day sitting at a sidewalk cafe in Mexico City where I lived, I had the crazy idea that I could teach a course on how to make a personal documentary. I wrote down this proposed curriculum, which I’ve kept on the backburner since then.

And I started noting down the first inklings of the “big picture” ideas that have led me to believe that personal documentaries represent a profound shift in democratized storytelling.

The last note I took was about future changes to make. Inevitably, as you share a creative work like this one that touches the lives of many people, the “casual suggestions” start coming in. People want a scene cut or added, they want you to interview just one more person, they want to correct something they said, and so on.

I knew that if I kept making these changes the film would never be finished. So I put them all in this note, knowing that if and when I wanted to make a new cut, all these ideas would be ready and waiting for me.

I want to emphasize that I didn’t know I needed most of the notes above until I actually created them. There was no grand master plan I was following. I got into action as quickly as possible, and captured learnings and insights in my notes as they came up.

What I LearnedHere are the biggest lessons I learned from the experience.

I WAS MORE PRESENT AND ENGAGED WITH MY SURROUNDINGSOne of my biggest concerns with starting this project was that I’d be less present in my life. I worried that I would obsess over looking out for opportunities to “get the shot,” instead of just enjoying everyday experiences.

I was surprised to find that the exact opposite happened.

I started to pay more attention to the little moments. The light reflecting off a dish as my mom placed it on the counter. The reflection in a doorknob as my brother reached to open it. The bubbles rising to the surface of a carbonated drink.

With my filmmaker’s eye, I started to notice that I was surrounded by little moments of beauty and poetry. As these moments became my creative medium, I started to appreciate them much more deeply. Time often seemed to slow down as I zoomed in on a particular scene, sound, or word.

PEOPLE RESPOND SURPRISINGLY WELL TO BEING FILMEDAnother concern I had was that everyone around me would feel awkward being “on the spot” all the time. I didn’t want to be that annoying person who is constantly asking people to pose.

But once again, I found that the exact opposite was the case. I was honestly shocked how comfortable people were being filmed.

Virtually everyone I captured on camera was far more vulnerable than normal, because the camera gave them a “reason” to be vulnerable. They opened up and shared memories that I’d never heard. Something about the focused attention of the lens, like a closely listening ear, gave them permission to speak incredibly honestly about their experiences.

PEOPLE HAVE MORE MEMORIES AND STORIES THAN THEY REALIZEIf you ask one of your parents, “What was your happiest memory as a child?”, you’re very likely to get a flippant answer. Not because they don’t want to tell you – they do. But in the humdrum routine of daily life, there just isn’t usually an opportunity to get into such memories. It feels strange for both parties.

But when you turn on a camera, even if that camera is just a smartphone, suddenly everything changes. Suddenly they feel a responsibility to tell you the real answer. They are doing you the favor of “helping you with your film project.” They open up because they have an excuse to.

I often had the thought that I could have put up the camera and only pretended to film, and it would have been worth it just for the depth of conversation it made possible. I was shocked to hear so many new stories from people I’ve spent more time with than anyone else.

I don’t think we realize how deep of a well of memory each human being has access to. Everyday life doesn’t give us many opportunities to revisit those memories. But recording them does.

THERE IS AN ART TO INTERVIEWINGI initially had the idea that interviewing was essentially just asking questions. I would look at journalists and wonder, “How hard could it be?”

I quickly discovered that there is a subtle art to interviewing. I played a major part in the performance of an interview as the “director” behind the scenes. The subject gets to just show up and talk. I am the one that has to plan, prepare, listen, and react to wherever they want the conversation to go.

People tend to drop all kinds of hints about what lies underneath the surface – offhand comments that point to something deeper, inflections in their voice that signal a hidden emotion, shifts in body language suggesting you’re getting somewhere sensitive.

It was in the moments that I noticed those hints, and pushed a little, that magic happened. A comment as simple as “Say more” can unlock an exquisite outpouring. And I think that people secretly hope you’ll ask for more. We all want to be heard, but we don’t want to speak unless we know the other person is listening.

FILM EVERYTHINGI learned early on that it paid to “film everything.” I started out being very picky about what I captured. I thought I needed just the perfect light, the perfect audio conditions, perfect preparation, and the perfect state of mind to get it right.

But I soon noticed that a perfectionistic attitude caused me to miss out on valuable shots, which tend to arise spontaneously in the moment. Sitting down at my computer to review my footage, I realized that there was a world of difference between “footage I had” and “footage I didn’t have,” whereas the difference between “footage I had,” and “the perfect footage” was much smaller.

Having any footage at all was essential, so it was worth getting out my camera and hitting record even if I wasn’t sure what I was filming or why. The magic of editing is that even if there is just one meaningful phrase in an hour-long clip, you know you’ll be able to find it and use it.

There’s a parallel here to note-taking in general. If you wait until you know exactly why you’re writing something down, it’s already far too late. You have to capture it right in the moment, taking advantage of the natural serendipity of the moment. Listening to your intuition about what resonates can give you a shortcut to saving valuable material before your conscious mind even knows what’s happening.

In the end I had a 17-to-1 ratio of raw footage to final cut, which should give you an idea of just how much you need to record in the first place. Professional filmmakers often report a ratio of 40 or 50 to 1.

HUMAN MOTIVATION IS STILL THE BOTTLENECKInitially I thought my takeaway from this project would be “See? It’s easy!”

But in retrospect that isn’t true at all. In fact, it took every skill in my toolbelt, every ounce of motivation, and a lot of support from others to maintain my momentum and persevere until the end, even with all the technological breakthroughs we’ve seen.

I estimate it took me about 100 hours of work spread over 16 months, broken down approximately as:

10 hours: planning, researching, coordinating30 hours: filming (spread out over about 20 filming days)10 hours: learning, testing, experimenting50 hours: importing files, organizing, editingInstead, my takeaway is “It’s easier than ever…but still very hard.” That said, I was also learning to make a documentary at the same time I was making it. For the next one, I’ll be able to reuse a lot of what I learned and use my time much more effectively. I estimate I could do it in half the time.

The decisive factor in any creative project is still the human being – their fears, desires, anxieties, limiting beliefs. It’s always been that way, and always will be. I found myself relying heavily on my productivity skills, capturing the many open loops for edits I had to make and tracking them through to completion. I also relied heavily on my note-taking skills, saving all sorts of tips and ideas and guidelines as you saw in the notes above.

I have no idea how I could have completed this project without having all the relevant information saved outside my head. I could only afford to spend a day or two at a time working on it in the midst of my other responsibilities, which meant that every time a bit of free time opened up I had to be able to jump into my notes and pick up right where I left off. I don’t know any other way of doing that besides keeping the “work in process” outside one’s head.

We are living in the midst of a creative renaissance, with every creative medium rapidly becoming more affordable, accessible, and shareable. But in some ways this makes it harder for us to create our own works – we are exposed at all times to the very best creators, artists, writers, musicians, and dancers in the world.

How could we compete with all that? What do we have to say that hasn’t already been said? It’s so much easier to give up our ambitions and spend our days scrolling through the accomplishments of others.

We could try to optimize how our brains work to make the creative process more efficient. We could set rigid schedules and work up the self-discipline to churn through our To Do lists. But I think that’s a mistake. Creativity requires randomness and serendipity, and we run the risk of optimizing the creativity right out of the experience.

I have another idea: we remove the bottleneck. Take the human out of the loop as much as possible, replacing her with a system of knowledge management. Such a system never sleeps, remembers all details perfectly, can connect and communicate with other digital tools, and preserves everything she’s working on so she can step away when life gets crazy and come right back to it later.

IF A STORY ISN’T SUCCINCT, IT’S INVISIBLEA few years back, my mom paid for a service to digitize several decades of home videos. She shipped off a few boxes of tapes in multiple shapes, sizes, and formats, and a few weeks later we received a login to access them via a convenient web portal.

But even with that convenience, we’ve rarely gone back to watch those videos. There are just too many of them – perhaps 300+ separate videos adding up to hundreds of hours of footage. In most of the clips I’ve seen there’s not much happening most of the time. The exceptional moments are rare and unexpected by definition.

It would take a serious effort to watch, curate, organize, label, and condense those best moments into a compilation video of 1-2 hours. Yet I don’t know of any other way to make those memories accessible in the future. Without such a succinct artifact, I doubt we will get much value out of this treasure trove of precious memories.

Here is what I’ve realized: even if records exist, if they’re not organized and condensed and presented in an accessible way, they might as well not exist. The effort required to weave together disparate clips with skillful editing, transitions and effects, audio and music into a captivating story isn’t a nice-to-have. It is essential to allow that story to survive through time in a way that it touches the lives of future generations.

But time and attention are more scarce than ever. Which makes me wonder whether, despite the many thousands of photos and videos we’ll capture digitally over our lifetimes, we’ll really have as much access to those in the future as we think.

Making our information digital was supposed to mean that we never lost anything again. But in making it so seamless and easy to just “save things in the cloud,” our technology has masked the very real effort required to create artifacts that stand the test of time.

Is it possible that the surplus of digital information is leading us toward a poverty of memory? That our lives will be no better documented than our parents or grandparents, and maybe not even that well?

VIDEO WILL BE THE COMMUNITY GATHERING OF THE FUTUREWorking on this project in the midst of the COVID pandemic, I was struck by how meaningful of an experience it was to watch this film together.

We all have an essential human need to come together – to grieve, to celebrate, to express ourselves, to resolve conflicts, to share our feelings. This need hasn’t disappeared in the digital era. It’s been channeled and amplified by “social” networks, and not usually in a healthy and productive way.

When I look out across the social media landscape I see a desperate, aching need to connect with each other. In the absence of positive connection, people will turn to destructive connection. That is how deep our need for connection goes.

Part of my motivation for this project was to see if I could create a true community experience online. I’d lived abroad in various countries for years, and so maintaining my community of family and friends had always been a preoccupation.

It succeeded beyond my wildest dreams. Even scattered across the country and world, the shared experience of immersion in a story created a “living room” experience. We all were watching something, knowing that others were watching it, knowing that they knew we were watching it, and so on in a reciprocal web of thoughts and emotions.

The essential ingredients for virtual community seem to be:

An artifact to gather around and spark conversation (the film)A strong pull of timeliness (an event happening at a particular time at a particular “place”)A reason to come: the ideas and insights and realizations promised by the filmA pre-existing community: my family, friends, and community around my work at Forte LabsA host (to welcome people and “manage the room”)A way to share reactions and feedback (comments during the YouTube Premiere, and a followup Zoom call we did right after)Video is the most widely available creative medium, as well as the most immersive. It is unique in allowing groups of people, even spread apart in different locations, to be immersed together. I’m fascinated by the potential of using video-based storytelling to bring people together in an era of social distancing.

No longer do you need an MFA or Hollywood internship to tell stories to a global audience.

We are living in a new world of democratized storytelling, but it is only those who take the time to turn their stories into tangible creative works who get a vote.

Thank you to Fred Esere, Shayna Englin, George Gusewski, Carlos Esteban Balderas, and Daniel Chapman for their feedback and suggestions on this article.

Subscribe below to receive free weekly emails with our best new content, or follow us on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, or YouTube. Or become a Praxis member to receive instant access to our full collection of members-only posts.

The post How I Made a Documentary Film with Digital Notes appeared first on Forte Labs.

October 26, 2020

Knowledge Building Blocks: The New Meaning of Notes

One day in your early school years, a teacher probably told you to “take notes” for the first time.

Looking around at your fellow classmates, this seemed to involve writing down what the teacher said, word for word, on lined pieces of paper.

For most of us, this is how our experience of note-taking started: with a mysterious command, and very little guidance in how to carry it out.

If you were lucky, you might have received a few basic note-taking tips. Make two columns. Use abbreviations. Underline key words. Write down the date. But that’s where it ended.

You knew it was time to take notes when the teacher said “This will be on the test.” This declaration implied that “getting a good grade” was the only reason you might want to take notes. The minute the final exam was over, you knew you would never make use of those notes again.

Taking notes in this way might have been the primary way you participated in your education – passively, for the short term, and only for the test.

And then you entered the professional world, and suddenly the whole approach to note-taking you learned in school became obsolete.

Unlike in school, in the professional world:

It’s not at all clear what you should be taking notes onNo one tells you when or how your notes will be neededThe “test” can come at any time and in any formYou’re allowed to reference your notes, but it’s up to you to organize themYou are expected to take action on your notes and turn them into results, not just regurgitate themNot to mention that the volume of information we are expected to manage doesn’t go down once we enter the workplace.

It explodes.

Every single day is filled with an overwhelming torrent of emails, invites, updates, messages, notifications, reports, reminders, and to do’s…each one screaming for our attention.

Once again, we are left on our own to somehow tame this flood tide. And again we are given precious little training or guidance. Even if we are lucky enough to have good note-taking habits left over from school, those habits don’t serve us in the radically different environment of work.

The new meaning of notesLuckily, the same technology that has fueled an explosion in the volume of information coming our way has also equipped us with the tools to manage it: digital notes apps.

Now that our notes are digital, they can become durable. They can last for the long term, supporting our long-term goals and ambitions without relying on our fragile memory.

But to fully embrace this digital future, we need to flip the definition of note-taking on its head, and leave behind the outdated approach we learned in school.

Here is my proposed definition:

A digital note is a “knowledge building block” – a discrete unit of information interpreted through your unique perspective and stored outside your head.

It could be a passage from a book or article that you were inspired by, a photo or screenshot with annotations, or a bullet-point list of your thoughts on a subject, among many other examples.

Once a piece of information has been interpreted through your lens, curated according to your taste, translated into your own words, or drawn from your life experience, and stored somewhere outside your head, then it’s a note.

Unlike a long, formal document, a note is discrete – it makes a single point, comes from a single source, or serves a single purpose. This gives each note clear edges and makes it easy to directly compare and contrast with other notes.

Like a LEGO block, a knowledge building block stands on its own and has intrinsic value. Yet each block can also be combined with others into greater works – a report, an essay, a website, or a video for example.

And just like LEGOs, these building blocks are reusable. You only need to put in the effort to create a note once, and then it can be mixed and matched with other notes again and again for any kind of project you work on, now or in the future.

When you take a digital note, you don’t have to worry about where it fits in. There doesn’t need to be any comprehensive table of contents. Just save any idea that resonates with you that you might want to reflect on, reconsider, or reference in the future. They can easily be moved, retitled, or edited later.

All you have to do is craft a single building block of knowledge each time you read or learn something, and save it in a central place. You can leave it to your future self to figure out what to do with it.

This approach simplifies our note-taking while also making it more valuable and flexible. It relieves us of the burden of sticking to a grand strategic plan, and frees us to focus on what really matters: the present moment, here and now.

Every digital note is like a bookmark reminding you of something you’ve learned in the past, and pointing you back to the original source if you want to recall it. Your notes are like a garden full of familiar, winding pathways, but also secret and secluded corners. Every pathway is a jumping off point to new ideas and perspectives.

Technology doesn’t just make note-taking more efficient. It transforms the very nature of notes.

No longer do we have to write our thoughts on Post-Its or legal pads that are fragile, easy to lose, and impossible to search. Now we write notes in the cloud, and the cloud follows us everywhere.

No longer do we have to spend countless hours meticulously cataloguing and transcribing our notes. Now we collect knowledge building blocks, and spend our time imagining the possibilities for what they could become.

Subscribe below to receive free weekly emails with our best new content, or follow us on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, or YouTube. Or become a Praxis member to receive instant access to our full collection of members-only posts.

The post Knowledge Building Blocks: The New Meaning of Notes appeared first on Forte Labs.

October 12, 2020

My Complete Gear Kit for Filming a Personal Documentary

This guide details the exact gear I used to make my personal documentary film Wayne Lacson Forte: On My Way To Me. For the full story behind the film, read here.

My priorities were:

The most minimal and affordable gear possible, since this was an experimentProducts that were highly adaptable and could be repurposed for other usesProducts that were as lightweight, compact, and portable as possible, since I knew I’d be traveling with this gearA filming setup I could easily carry and operate completely on my own, without requiring other peopleI was surprised to discover that there were essentially only 4 categories of gear I needed:

CameraMicrophoneTripodVideo-editing softwareBelow I’ve explained each item I used in my own film project, how I used it, and whether I would use it again. I’ve included “basic” and “advanced” options, labeled accessories as “required” or “optional,” and suggested alternatives when possible.

Here’s the complete kit, with affiliate links to buy each item:

[image error]Essential items are labeled in red#1 Camera (smartphone + $300)

1. Camera: Apple iPhone 10 XS, 512 GB storage capacity

$1,350

2. Freefly Movi Cinema Robot Smartphone Stabilizer

$300

Optional accessory for use with any smartphone

#2 Microphone ($27-275)

3. Basic option: PoP voice Premium 16 Feet Dual-Head Lavalier Microphone

$19

4. Apple Lightning to 3.5 mm Headphone Jack Adapter ($8)

$8

Required accessory for PoP voice mic

5. Belkin F8J212btWHT 3.5mm Audio + Charge

$39

Optional accessory for PoP voice mic

6. Advanced option: Zoom H1n Portable Recorder

$120

7. Rode SmartLav+ Omnidirectional Lavalier Microphone

$76

Required accessory for Zoom H1n

8. Movo MC4 TRRS to TRS Adapter

$13

Required accessory for Zoom H1n

#3 Tripod ($20-198)

9. Basic option: UBeesize Mini Tripod S

$20

10. Advanced option: Vanguard VEO 235AB Aluminum Travel Tripod

$150

11. Glif Quick Release Tripod Mount for Smartphones

$28

Required accessory for mounting smartphone on any tripod

#4 Video-editing software ($300 + $32/mo)

12. Video-editing software: Adobe Premiere Pro subscription

$32/mo

13. Red Giant Pluraleyes 4

$300

Optional accessory for Adobe Premiere

The total cost of the items above was $2,416. $1,350 of that was the smartphone, which most people are likely to have already. Which means that beyond the phone, my total expenditure was only $1,066.

If cost is your main concern, and you already have a smartphone, you could do perfectly fine with this alternative kit of the essentials, for as little as $47:

Essentials kit ($47)

1. Basic option: PoP voice Premium 16 Feet Dual-Head Lavalier Microphone

$19

2. Apple Lightning to 3.5 mm Headphone Jack Adapter ($8)

$8

Required accessory for PoP voice mic

3. Basic option: UBeesize Mini Tripod S

$20

4. Free video-editing program

$0

Pre-installed programs like Apple iMovie or Microsoft Movie Maker, programs with free versions such as DaVinci Resolve, or open-source programs like OpenShot or Kdenlive

Read on for my full recommendations and lessons learned.