Tiago Forte's Blog, page 19

September 7, 2021

The Keystone Course Accelerator: Cohort 2

The online education industry is blowing up.

Projected to grow by 247 billion dollars by 2024, online education is now known simply as “education.” Years’ worth of growth is happening in months as traditional institutions struggle to keep up and everyone from K-12 students to college students to professionals desperately seek ways to connect and learn remotely.

23 years after “e-learning” was first coined in 1998, the online education industry is also growing up. This new generation of online learners isn’t swayed by pushy ads, clickbait headlines, inflated promises, or fake urgency. They are looking for high-quality, professional, legitimate programs that reliably deliver the same kinds of results they might otherwise receive from an MBA, conference, or intensive seminar.

As exciting as all of this growth is, when I look at what truly matters in making an online course successful, the answer is clearly marketing. Online education is sales-centric in a way that no other previous kind of education was, because for the first time the teacher is responsible for finding their students. Without a consistent flow of sales, even the best course in the world will wither and die.

Within the sphere of marketing, the single most important element – the keystone of the entire edifice you are building – is messaging. Messaging is your “sales copy” – the words, emotions, metaphors, stories, and positioning you use to enable your prospects to decide if your course is the solution they need.

What is your message? What is the basic thing you have to say to the world? What do you stand for and represent? What are you offering that no one else can offer? There is a message at the core of what you do that, if you can identify it and learn to say it well, is like a key that unlocks the hearts and minds of the people you want to serve.

Strong messaging is what sells courses – not catchy names, slick design, ecstatic testimonials, or a curriculum packed with modules. I see course creators pouring so much time and money into every aspect of their programs, while neglecting the messaging that truly makes a difference. Your copy is like a permanent salesforce pitching what you do day and night around the world. To this day, my course website is something I built myself using a drag-and-drop website builder without involving a designer, developer, or agency. But it works, because the words do the heavy lifting.

When I look out across the online education landscape today, I see a dramatic underappreciation and underinvestment in the fundamentals of marketing. There are proven techniques and approaches from the direct marketing industry that have worked for decades. I think we have a blind spot for it because we think it’s corny and pushy. But that is exactly the opportunity: to update online marketing and make it classier, more authentic, more honest, and more humane.

In November 2020 I partnered with my marketing coach Billy Broas to launch the first ever cohort of the Keystone Course Accelerator. I’ve had the pleasure of watching that first group of 35 alumni take what they learned and apply it to their online education businesses. They’ve used the Keystone Framework to understand their audience on a deeper level, write more effective sales copy based on authentic stories, and ultimately create programs that are more profitable, sustainable, and connected to the needs of their customers.

We’ve taken every lesson and insight from the first cohort and distilled it into a radically improved second cohort of the Keystone Course Accelerator, which kicks off on October 11.

There are five major changes that Billy Broas, the creator and instructor of the accelerator, is making to ensure this is the best training on transformative education in the world:

1. Walk away with a custom Messaging PlaybookBilly will work alongside each participant to create a Messaging Playbook with the core messaging of your program.

Like a Brand Manual for a company (which can easily cost tens of thousands of dollars), this Playbook will be the “single source of truth” for the program you’re creating. It will inform every other component you’ll need, from the sales webpage to the free content to social media posts to sales scripts to use on the phone.

You’ll be an integral part of the process of creating the messaging that guides every subsequent decision, instead of having to make those decisions at every point along the way, which is exhausting. The crux of effective marketing is effective sales copy, and in Keystone you’ll spend the majority of your time finding the words that move people to purchase regardless of the medium.

2. Adding 12 months of implementation coachingLast time, a group of alumni decided to continue meeting and developing their copywriting skills. This time Billy is making that long-term support an official part of the program. Following the 8 weeks of the cohort, Billy will host regular check-in calls for the entirety of 2022 to go deeper on case studies, share what’s working from other successful programs, and provide feedback on the marketing systems you’re building.

The initial cohort is like the launch sequence shooting you beyond the planet’s gravity; the alumni coaching is the booster keeping you perpetually in orbit.

3. Focus on outcome-based educationThe biggest change in the education landscape that Billy has seen in the last year is the shift to “outcome-based” programs.

People enroll in courses because they want concrete, undeniable results in their own lives. They don’t care about the list of features, the fine details of the curriculum, or the minutiae of Zoom calls. As a society we are beginning to question the assumption that higher education inevitably leads to higher incomes and better careers. Online, we can measure those results, provide the support people need to realize them, and collect all the data needed to make it better.

From now on, the success of every online course will be measured by the reliability of the outcomes it produces for every student.

4. The latest version of Billy’s signature messaging frameworkYou’ve probably heard from many sources that “People aren’t buying content – they’re buying a transformation.”

But what the heck does that mean? I never knew what transformation truly meant until I was introduced to Billy’s messaging framework, The Bridge of Transformation. It’s become the centerpiece of his work with clients across dozens of niches due to its ability to illuminate a precise 5-step process (called the “5 Lightbulbs”) that every prospect must follow to become a customer.

Often, the transformation you create for people is so natural and innate for you that you can’t see it. In Keystone you’ll use an interviewing process to help each other find those nuggets of language that speak to people’s deepest, most hidden desires.

5. Alumni Mentors and Copywriting CoachesA small group of alumni from the first cohort have offered to come back and support the next round of Keystone. They will act as peer supporters encouraging you along the journey and demonstrating what success can look like.

Billy is also bringing on Copywriting Coaches for the first time – specialists with experience writing real copy for successful online programs who will provide feedback, edits, and suggestions on the writing participants produce.

You’ll also get access to exclusive guest workshops delivered by me and other former clients of Billy’s who have had breakout success applying his approach. I’ll share up-to-date details on what’s working for my course that I don’t share in any other forum, public or private.

Apply for one of the 30 spotsThe Keystone Accelerator is an advanced program for established subject matter experts and existing course creators who are ready to scale the marketing engine behind a program that’s already working. If you’re just getting started or have yet to begin your entrepreneurial journey, this isn’t the program for you.

We are limiting the next cohort to only 30 participants, selected via an application and interview process. The best candidates are actively selling premium educational products: online courses, cohort-based live courses, or high-end group coaching programs that promise and deliver on a tangible outcome.

This is NOT a program designed to help you develop or improve your content or design the student experience once they’re inside. It’s about telling the story of the impact you’re already making in a way that enables you to reach people you otherwise wouldn’t be able to.

I couldn’t be more proud to share access to one of the most experienced, in-demand consultants in the exploding world of online learning. If you are serious about making a difference in the lives of your students, if you refuse to waste your time on training by anyone but the best, and you are seeking the most direct path to the next level of success for your business, I invite you to join us.

Opt in below and I’ll send you a series of educational emails starting Monday, September 13 to bring you up to speed on what’s happening in the business of online education. I’ll introduce you to Billy, invite you to a free workshop we’re hosting on the Keystone Framework, and invite you to apply if it’s a good fit for you.

Subscribe below to receive free weekly emails with our best new content, or follow us on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, or YouTube. Or become a Praxis member to receive instant access to our full collection of members-only posts.The post The Keystone Course Accelerator: Cohort 2 appeared first on Forte Labs.

September 3, 2021

Dan Charnas on Working Clean: An Interview on the Power of Mise en Place

I recently hosted Dan Charnas, author of the book Work Clean: The Life-Changing Power of Mise-en-Place to Organize Your Life, Work, and Mind (affiliate link), for an in-depth conversation about the most interesting, impactful principles from his work.

Dan takes us on a fascinating journey through his career in the music business, as one of the first music executives to bring hip-hop to the mainstream, to watching the rise of Anthony Bourdain’s Kitchen Confidential, where he heard about the practice of mise en place that Bourdain used to stay centered in the eye of the media storm.

After studying the masters of productivity like Stephen Covey and David Allen, and getting a Master’s degree in journalism, Dan spent 2 years applying his journalistic lens and interviewing chefs, culinary students, teachers, restaurant executives, and people from many different walks of life to turn mise en place into something we can all use.

Watch the 60-minute recording below, and be sure to follow Dan on Twitter and visit his website to hear more about his work.

Subscribe below to receive free weekly emails with our best new content, or follow us on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, or YouTube. Or become a Praxis member to receive instant access to our full collection of members-only posts.The post Dan Charnas on Working Clean: An Interview on the Power of Mise en Place appeared first on Forte Labs.

August 30, 2021

Tiago Forte on the Mindvalley Podcast: 4 Powerful Tools to Boost Your Productivity

I recently joined Vishen Lakhiani, Founder and CEO of the education company Mindvalley, on the Mindvalley Podcast to talk about the 4 essential tools I think every modern professional needs in their toolkit. I also talked through my CODE methodology, which lies at the heart of my approach to building a “Second Brain.”

Listen below, or visit the episode webpage on Apple Podcasts.

Subscribe below to receive free weekly emails with our best new content, or follow us on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, or YouTube. Or become a Praxis member to receive instant access to our full collection of members-only posts.The post Tiago Forte on the Mindvalley Podcast: 4 Powerful Tools to Boost Your Productivity appeared first on Forte Labs.

August 29, 2021

Second Brains in the Wild

I’m often surprised when people find the idea of a “Second Brain” – a system of knowledge management that lives outside one’s head – to be fanciful or unrealistic.

When in fact, the practice of saving and storing important information in a trusted place is ubiquitous.

Professionals of all kinds have developed ways of documenting their ideas, insights, operational details, and lessons learned.

Here are examples of specific kinds of knowledge management tools used by various professions:

Songwriters keep hook books with musical passages that might make good hooksComedians keep gag archives with material for future bitsNatural dyers maintain dye journals with “dye recipes”Programmers keep code libraries with snippets, links, and examples of code that they’ve found useful in the pastTheatre stage managers use prompt books to record the details of sets and the scenes that play out on themFashion designers keep portfolios with their drawings and clothing designsGolfers keep yardage books with their notes on the golf courses they play so they know what to expect each time around that holeLawyers keep case files (also known as “brief banks” or “motion banks”) with details from past cases they might want to refer to in the futureCustomer service representatives maintain personal knowledge bases with standard responses for common customer issuesEntrepreneurs compile idea books with their business and product ideasScientists and researchers use field notebooks to record their observations in the fieldRappers have rhyme books with snippets of evocative lyricsTeachers keep lesson plan books for the next time they want to reuse a lessonMarketers and advertisers keep swipe files with examples of compelling adsMilitary officers use a little green notebook to take notes during briefings, log physical training scores, and keep track of inspections Subscribe below to receive free weekly emails with our best new content, or follow us on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, or YouTube. Or become a Praxis member to receive instant access to our full collection of members-only posts.The post Second Brains in the Wild appeared first on Forte Labs.

What do you call your Second Brain?

A system of personal knowledge management, which I call a “Second Brain,” is an indispensable part of any modern professional’s toolkit.

Because it is such a personal tool, it’s important to give it a name that evokes the special relationship you have with it. Here is a collection of alternative names for a Second Brain you can draw inspiration from, submitted in response to one of my tweets:

ZettelkastenExocortex/ExobrainExtended mind/External brainDigital twinAugmented memoryPeripheral brainDigital commonplace bookMind palaceNetworked knowledge systemThought potThink tankPensieve (from Harry Potter)Personal knowledge stackPersonal cloudSynaptic journalIdeaspaceMirrormindField notesDigitized memoryPersonal knowledge systemPersonal search engineLMS (Life Management System)Mindbase/MindvaultDigital distilleryMetabrainImagination engineCognitive prostheticsMemexStreamcatcherKnowledge graphMind sieveIdea labThought librarySearchable thought dumpsterDigital garden Subscribe below to receive free weekly emails with our best new content, or follow us on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, or YouTube. Or become a Praxis member to receive instant access to our full collection of members-only posts.The post What do you call your Second Brain? appeared first on Forte Labs.

August 23, 2021

Octavia Estelle Butler: Notetaking as Science Fiction

Octavia Estelle Butler was born in 1947 in Pasadena, CA.

Known in her early years as “Estelle,” she was raised by a single, widowed mother who worked domestic jobs to make ends meet. Painfully shy and introverted from a young age, Estelle became an easy target for bullying at school. Her shyness combined with slight dyslexia made schoolwork difficult as well.

Estelle turned inward – to her own imagination – and outward, to the Pasadena Central Library, where she would spend countless hours reading fairy tales and horse stories, and later, the fantasy and science-fiction novels that would inspire her to become a writer.

Despite so much stacked against her, this young woman would eventually become one of the most successful and influential science-fiction writers of her generation, winning multiple Hugo and Nebula awards and in 1995 becoming the first sci-fi writer to receive a MacArthur Fellowship (known as the “Genius Grant”).

How could an intensely shy little girl become a world-renowned, award-winning writer? How could an impoverished and overworked young woman emerge as a powerful prophet of the future?

There are clues in the Octavia Butler Archives, a collection of 9,062 items filling 386 boxes that was donated to the Huntington Library in San Marino, CA after Butler’s death. It contains her journals, commonplace books, speeches, library call slips, essay and story drafts, school notes, calendars, and datebooks as well as assorted odds and ends like school progress reports, bus passes, yearbooks, and contracts.

A new book by Lynell George, A Handful of Earth, A Handful of Sky: The World of Octavia Butler (from which all the pictures and quotations in this article are drawn), tells the story of how these notes played a crucial part in Estelle’s journey.

Early signs of promise and perilEstelle’s teachers at Garfield Elementary evaluated her earliest writing harshly, with comments like “Hyperbolic” and “You’re not even trying” scribbled in the margins.

A teacher once questioned in the margins of one of her writing assignments, “…why include the science fiction touch? I think the story would be more universal if you kept to the human, earthly touch.” And reported to her mother that, “She has the understanding, but doesn’t apply it. She needs to learn self discipline.”

At the age of 10, Estelle’s mother bought her a Remington typewriter to encourage her fledgling writing. She had no idea how to use it and spent years pecking away one finger at a time. When Estelle was 12 years old, she watched the film Devil Girl From Mars (1954), a sensationalist B-film that was so terrible it convinced her on the spot that she could write something better.

She said, “Until I began writing my own stories, I never found quite what I was looking for…In desperation, I made up my own.” She continues, “I made a universe in it. There I could be a magic horse, a Martian, a telepath. There I could be anywhere but here, any time but now, with any people but these.”

As the possibility of becoming a professional writer slowly dawned on her, Estelle began her transformation into “Octavia,” her powerful, assertive alter-ego. Octavia took on a series of temporary or part-time jobs after graduating from high school: clerical, factory, warehouse, laundry, and food preparation gigs. Anything that wasn’t too mentally taxing, allowing her to maintain a habit of waking before dawn each morning to write.

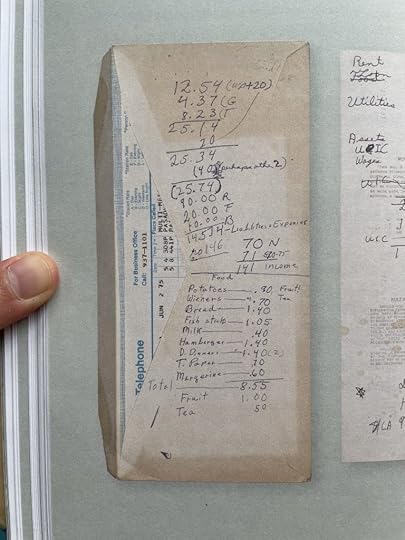

Back-of-the-napkin accounting Butler used to make ends meet Taking notes on the future

Back-of-the-napkin accounting Butler used to make ends meet Taking notes on the futureThe emerging Octavia had three rules for herself:

Don’t leave your home without a notebook, paper scraps, something to write with.Don’t walk into the world without your eyes and ears focused and open.Don’t make excuses about what you don’t have or what you would do if you did, use that energy to “find a way, make a way.” One of Butler's envelopes dedicated to "Free-floating ideas"

One of Butler's envelopes dedicated to "Free-floating ideas" Thus began Butler’s lifelong relationship with her commonplace books. She would scrape together twenty-five cents to buy small Mead memo pads, and in those pages took notes on every aspect of her life: grocery and clothes shopping lists, last-minute to-do’s, wishes and intentions, calculations of her remaining funds for rent, food, and utilities. She meticulously tracked her productivity and writing progress: daily goals and page counts, lists of her failings and desired personal qualities, her wishes and dreams for the future, and contracts she would sign with herself each day for how many words she would complete.

A contract Butler signed with herself: "This working period I'll complete a rough draft of a short story."

A contract Butler signed with herself: "This working period I'll complete a rough draft of a short story." And of course, Butler gathered material for her fantastical stories: lyrics to songs she’d heard on the radio, an idea for a character’s name or motivation, a new topic to research, details of news stories – everything she needed to build the worlds her characters would inhabit.

A worn memo pad, labeled with the years 1990-1992

A worn memo pad, labeled with the years 1990-1992 She studied dozens of topics both in school and independently – anthropology, English, journalism, and speech. She traveled to the Amazon and Inca ruins in Peru to get a firsthand taste of biodiversity and civilizational collapse. Like a journalist, Butler had a love for cold, hard facts to imbue her stories with a sense of authenticity and concreteness: “The greater your ignorance the more verifiably accurate must be your facts,” she said.

Pioneering AfrofuturismAs one of the first black women to gain recognition in the sci-fi genre, Butler explored ideas and themes that had been largely ignored until then: the potential consequences of environmental collapse due to climate change, corporate greed, the growing gap between the wealthy and poor, gender fluidity and the “othering” of marginalized groups, and criticism of the hierarchical nature of society. She was a pioneer of Afrofuturism, a genre that cast African-Americans as protagonists who embrace radical change in order to survive. Her stories allowed her readers to visualize futures in which marginalized people are heroes, not victims.

One of Butler’s novels, The Parable of the Sower, hit the New York Times Bestseller list for the first time in 2020, fulfilling one of Butler’s life goals 14 years after her death. The book portrays a post-apocalyptic future in which small communities must band together in order to survive.

Lauren Valdez describes the story in a blog post: “Two decades before the election of Trump, Sci-Fi writer Octavia Butler wrote about a presidential candidate with a zealot religious following who promises to ‘make America great again.’ The book Parable of the Sower takes place in the 2020s, the decade referred to as “The Pox” short for the apocalypse. The book, part of her Earthseed series, is a haunting depiction of a post-climate disaster society. Water is more expensive than gasoline. Public institutions shut down, most people are illiterate, and many die.”

These eerily prescient forecasts resonated with readers as the COVID pandemic unfolded, as our own time began to seem similarly bleak and uncertain. The radical re-imagination of what life can look like is no longer idle speculation – it has become a daily necessity for people around the world.

Butler has been called a prophet for her ability to forecast the future, but she often said that her work came from simply imagining, “If this goes on… it extrapolates from current technology, current ecological conditions, current social conditions, current practices of any sort. It offers good possibilities – as well as warnings.”

Butler knew that science-fiction was more than entertainment. It was a transformative way of viewing the world. Science-fiction removes barriers and constraints on what we allow ourselves to envision. Anything is possible in the future, so why not fill it with the people, the stories, the places, and the events that you most want to see?

Butler explained that “Science fiction allows me to write about sexually and/or racially egalitarian societies that don’t exist anywhere on earth today. I don’t write about perfect societies – utopias – first because they’re boring, and second because I don’t think they’re attainable by imperfect humans. But I can visualize societies in which sex and race are interesting differences and not a mark of inferiority or superiority.”

She expanded our vision of the future to include the experiences of the disenfranchised, the outcast, and the unconventional.

A typical weekly writing schedule for Butler Fueling writing with life

A typical weekly writing schedule for Butler Fueling writing with lifeButler drew on her life experience as a primary source: “The painful, horrifying, the unpleasant things that happen, affect my work more strongly than the pleasant ones. They’re more memorable and more likely to goad me into writing interesting stories.”

She used her notes and her writing to confront the demons of self-doubt within her: “The biggest obstacle I had to overcome was my own fear and self doubt – fear that maybe my work really wasn’t good enough, maybe I wasn’t smart enough; maybe the people telling me I couldn’t make it were right.”

One of Butler's commonplace notebooks

One of Butler's commonplace notebooks She used every bit of insight and detail she could find in the books she immersed herself in: “Use what you have; even if it seems meager, it may be magic in your hands.” Butler found a way to express her voice and her ideas even when her circumstances made it seem impossible.

The myth of the writer sitting down before a completely blank page, or the artist at a completely blank canvas, is just that – a myth. Prolific creatives depend on prolific notes. They constantly draw on sources of inspiration – their own daily experiences and observations, lessons gleaned from successes and failures alike, and the work of others.

If there is a secret to creativity, it is that creativity emerges from practical efforts to gather and organize outside influences.

Subscribe below to receive free weekly emails with our best new content, or follow us on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, or YouTube. Or become a Praxis member to receive instant access to our full collection of members-only posts.The post Octavia Estelle Butler: Notetaking as Science Fiction appeared first on Forte Labs.

August 9, 2021

The Godfather Notebook

In 1969, studio executives at Paramount Pictures were desperate to find a film director for a new movie they had purchased the rights to. It was to be a crime drama based on the New York Mafia.

One after another, all the top directors of the era turned the project down. They all found it too sensationalistic and sultry for their tastes. Gangster movies were known as cheap and gimmicky, appealing to clichés instead of standing out as art.

After exhausting all their top choices, studio executives approached a young film director who had done a few small, indie films. The director was a relative novice, with no major commercially successful films to his name. He was an outsider, working out of San Francisco instead of Hollywood, the industry capital. And he was known as an artist who wanted to experiment with new ideas, not a director of big budget movies.

That director’s name was Francis Ford Coppola, and the moive he was asked to make was called The Godfather.

Coppola initially turned down the project. As recounted in the Hollywood Reporter, he said “It was more commercial and salacious than my own taste.” But as his partner and protégé George Lucas (of future Star Wars fame) noted, they were broke. Without a major infusion of cash, they’d soon be evicted.

A second reading of the novel changed his mind, as he saw that it could be framed as “a story that was a metaphor for American capitalism in the tale of a great king with three sons.”

The Godfather would go on to become one of the greatest critical and commercial successes in filmmaking history. In 2007 the American Film Institute named it the second best American movie of all time, after Citizen Kane. It ultimately grossed $245 million dollars, won three Oscars, and spawned a series of sequels and spinoffs watched by a rabid fan base obsessed with the story of the fictional Corleone family.

Coppola’s strategy for making the complex, multi-faceted film rested on a technique he learned studying theatre at Hofstra College, known as a “prompt book.” He would start by cutting and pasting pages from The Godfather novel into a three-ring binder. Once there, he was free to add notes and comments that would later be used to write the screenplay and plan the production design.

A photo of the spine of Coppola's prompt book

A photo of the spine of Coppola's prompt book In a short documentary titled Francis Coppola’s Notebook released in 2001, Coppola explains his process. He started with an initial read of the entire novel: “I think it’s important to put your impressions down on the first reading because those are the initial instincts about what you thought was good or what you didn’t understand or what you thought was bad.”

In other words, he started by “capturing” the parts of the book that resonated with him, and moving them into an environment where they could be distilled and interpreted. The notebook was designed to last, with reinforced grommets to ensure the pages wouldn’t tear even after many turnings: “The object of this was to give one the large area around the text for the many notes a stage manager would need to enter, such as lighting cues, scene shift cues, actors’ entrances, special effects, music cues, and so forth.

This notebook became the central document guiding the creation of the film: “I called it the Godfather Notebook and put a big warning: if found return to this address for reward, because I recognized that it would have every opinion that I had on the book.”

Title page of the Godfather Notebook, including the address to forward it to if lost

Title page of the Godfather Notebook, including the address to forward it to if lost It took many hours to create, but those hours also gave Coppola time to let the ideas and themes and characters simmer semi-consciously in his mind: “The building of the prompt book took hours, and the tedious activity of cutting, reinforcing, and organizing the pages provided many meditative hours during which one could use the other side of the brain to roam over the ideas and essential themes of the playwright’s intention.”

Once he had reconstituted his version of the story, Coppola began to add his own interpretations and observations. He broke down each scene according to five key criteria: a synopsis (or summary) of the scene, the historical context, imagery and tone to give the “look and feel” of the scene, the core intention, and any potential pitfalls to avoid.

Coppola explains how he used the “synopsis” of each part of the book as a building block in his film outline: “l’d write a brief paragraph or two saying what was happening in that section. And also, I was being sneaky; I knew that when I was finished, if I just put the synopsis parts of each section together, I’d have the embryo of the script – which I did, and which it was. The script was based on the synopsis of each section.”

An index of key scenes drawn from The Godfather novel, which would form the backbone of the film

An index of key scenes drawn from The Godfather novel, which would form the backbone of the film The historical context of each scene was another pivotal part of his planning. When Coppola heard that Paramount Pictures wanted to shoot the film as a contemporary story set in the 1970s, and use another city like Kansas City or St. Louis to save on production costs, he pushed back: “I really had a very hard time accepting that and made a big point that it had to be period. I didn’t even remember why I did because obviously that was going to make the movie more expensive which is not what they wanted at all. And it must have been because I had just gone through this vast, big thick book writing notes as to why it had to be…what the 40s had to do with the story.”

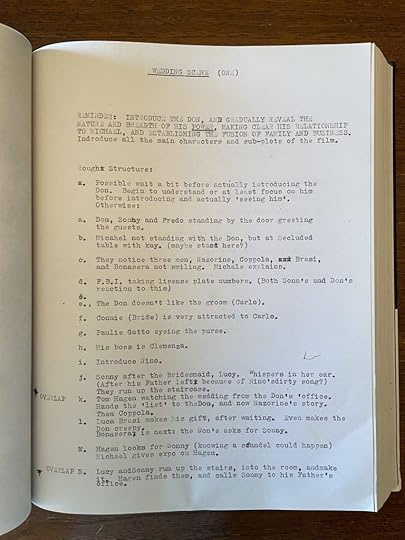

Production notes on the opening wedding scene, to which Coppola would add details from his memories of Italian weddings

Production notes on the opening wedding scene, to which Coppola would add details from his memories of Italian weddings The Godfather Notebook helped turn the complex and ambiguous task of creating a big-budget film into a regular routine: “I would sometimes go to a cafe, in particular in North Beach [a traditional Italian-American neighborhood in San Francisco] I used to go to the old Caffe Trieste, and sit in the corner with my Olivetti typewriter and this [prompt] book…”

Coppola continued, “This document was a kind of multi-layered road map for me to direct the film…so I was able to review not only Mario Puzo’s original text but all my first notation as to what…was important to me or what I felt was really going on in the book.” In the margins he wrote comments, observations, and emphasized certain details or emotional undercurrents.

Coppola continues, “…I very carefully went through each page of the novel, detailing and expanding my original pencil notes with different-colored pens and a ruler, putting down the details of how I would dramatize or especially accentuate certain things. When I saw an opportunity for great effect or showing violence, I’d make notes such as ‘mists of blood’ or ‘hit hard here.’ Those were just things that came from my imagination and instinct as I was reading the novel and trying to imagine it, and I put them down on those same pages, in color.”

One comment said simply “Hitchcock” to remind him of how the famed director of thrillers would have designed a scene, or “Frozen time” to remind him to slow down a shot, or “His fork frozen mid-air” to remember small details. He used different kinds of annotations to emphasize to his future self which parts were most important in a scene: “As I was reading the book and making these notes and then putting them on the margins obviously the more pens I was using and the more rulers, and the more squiggly lines, sort of implied the excitement of the book was higher and higher, so that the sheer amount of ink on the page would tell me later on this is one of the most important scenes.”

Notes on the shooting of Solozzo by Michael Corleone, one of the most important scenes of the film

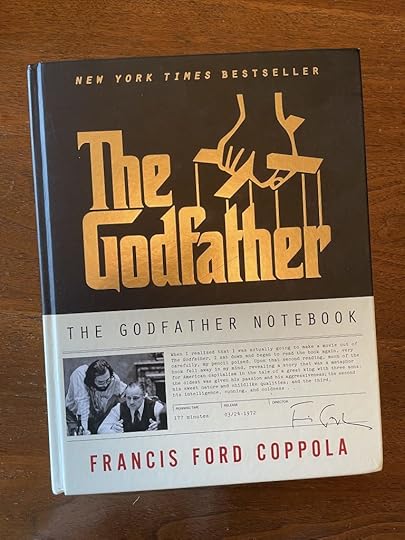

Notes on the shooting of Solozzo by Michael Corleone, one of the most important scenes of the film Coppola considered his prompt book his most important asset in the production of the film: “…the script was really an unnecessary document; I didn’t need a script because I could have made the movie just from this notebook.” So much so that he eventually published a complete replica of The Godfather Notebook in its entirety.

Front cover of the published version of The Godfather Notebook

Front cover of the published version of The Godfather Notebook In the introduction to that published version of The Godfather Notebook, Coppola says, “I endeavored to distill the essence of each scene into a sentence, expressing in a few words what the point of the scene was. It was very important, in the course of looking over the novel, always to say clearly what the core of every scene was.”

The Godfather Notebook illustrates that even for a fictional story, source material is essential. We might imagine a movie emerging straight out of the mind of a screenplay writer or director, when in fact, it depends heavily on a process of research and development. We don’t often get a window into the details of this creative process. It rarely gets documented and shared with the public. But Coppola’s story demonstrates that we can systematically build and improve our creative process to produce better, more imaginative work.

In The Godfather Legacy, a book on the behind-the-scenes making of the movie, Coppola is quoted as he reflects on his childhood aspirations to become a filmmaker: “I always felt I had a lot of gifts, but that my gifts were somehow not easily showable. I always felt I had a lot of stuff in my heart, but that I didn’t have the skills or the obvious talents of kids who can play an instrument, tap-dance, or draw. I always felt like I had a little vein of gold, and that if I could follow it further down I’d find a deposit of it.”

The films that he created were a way of finding and following that vein of gold within himself. And they didn’t depend on his willpower or imagination. They depended on a creative process that allowed the director to externalize his ideas, work with them as tangible building blocks, and distill the essence of the story he wanted to tell.

From the introduction to the published Godfather Notebook he explained what that process meant to him: “In truth, I think that I made the notebook out of profound fear. It’s important to understand that at the root of it all, I was terrified… I thought that if I could first work out the story on a set of blueprints – a plan – I would then be able to sleep at night. I would feel that at least I would be taking a step forward, that doing it this way would help me get a handle on how to do the script. I was sort of blindly looking for a structure to organize myself in order to get the most out of the subject matter, and the notebook was the result of that.”

If one of the greatest filmmakers of the 20th century can use notetaking to capture, organize, distill, and express his ideas then so can we.

Thank you to Alexandra Allen and Aries Chan for their feedback and suggestions on this piece.

The post The Godfather Notebook appeared first on Forte Labs.

July 15, 2021

Forte Labs Director of Content

TLDR: We’re seeking a Director of Content to take charge of our content production, develop a long-term strategy for growth, and lead our team in executing that strategy. You will touch every corner of the Forte Labs content universe and be responsible for leading our media brand across all channels. The role is highly flexible, fully remote, and asynchronous except for occasional trips within the U.S., with a salary in the $80,000–$100,000 range.

MissionAt Forte Labs, our mission is to help people capitalize on the value of their knowledge and expertise and use it to achieve their ambitions and lead more fulfilling lives in the 21st century. We produce written and audiovisual content on “the art and science of knowledge work.” From teaching people how to effectively use productivity software to helping them develop self-awareness around how their mind works, to creating a system of knowledge management to leverage what they know (which we call a “Second Brain”).

Our originsOver the last 7 years, a little blog started on Medium has grown into a full-fledged media company:

A website and blog that receive a million visitors a yearA newsletter that goes out to more than 47,000 subscribers every weekA Twitter following of over 45,000 (plus Facebook, LinkedIn, and Instagram)A YouTube channel with 18,000 subscribers and half a million views in the last yearCommunity groups on Facebook, Slack, and Circle with over 10,000 membersA premium online course taken by thousands of students per year and generating 7-figures per launchA forthcoming book to be published by Simon & Schuster in July 2022

Our new Director of Content will work across all of the above.

We are looking for an experienced professional to accelerate Forte Labs into a truly global, transformational media platform for personal productivity and knowledge management for the 21st century.

Here’s howEditorial workflow: Document and manage our content pipeline; add rigor and predictability to the process of turning new ideas into published content, products, and services.Coordinate content production: Work with both internal colleagues and outside contractors and specialists to produce new contentContent strategy: Set our long-term direction and content goals, set and follow an editorial calendar, follow monthly themes, cross-promote across channelsBranding: Develop consistent guidelines for the Forte Labs brand (colors, typeface, language) and ensure they’re followedContent promotion: SEO and keyword optimization (across all channels); repost and repurpose existing content into new formats and on new platformsAudience growth and engagement: Grow the Forte Labs audience (followers, subscribers, members, customers) through organic and paid acquisition (ads, partnerships, affiliates, referral incentives, etc.) while optimizing for engagementLaunch content products: Lead the launch of the Building a Second Brain book, due to be published in July 2022, as well as other products based on Forte Labs content

Every day in this role will be different. For example, a typical week could look like this: On Monday, you’ll be preparing a newsletter to go out to tens of thousands of people the next morning. On Tuesday, you’ll be producing an interview series for the podcast. On Wednesday, you’ll be helping me revise our course content to improve the student experience. On Thursday, you’ll be conducting research for an in-depth blog post. On Friday, you’ll be coordinating with a video editor on the next YouTube upload. You will touch every corner of the Forte Labs platform.

I’m looking for someone who wants to build a transformative media brand with the potential to shape how people work and learn all over the world. Who embraces growth and change and sees their work as a means of self-expression and service, not just a paycheck. Who believes in our mission of using technology as a force for good. And who understands the critical role of written and audio-visual content in realizing our vision.

Sound familiar?You have excellent writing skills, with experience producing written and other kinds of how-to contentYou have experience managing a small team, both in-house and contractors, to execute on long-term projectsYou have experience growing and scaling an online media brand based on the work of an independent creatorYou are comfortable wearing many hats, in a wide-ranging role requiring rapid learning and openness to feedbackYou can work across mediums and channels, from writing to video to audio to virtual and in-person eventsYou can manage both the creative and operational sides of high-volume content productionYou are comfortable working on a small, bootstrapped team to flexibly and creatively solve problems as they ariseYou are highly independent and self-directed, but also skilled at collaborating with a distributed, asynchronous teamYou are located in the U.S. and can travel regularly (every 2-3 months) to the LA area or other locations within the U.S. for team retreats and in-person collaborationCompensation and benefits$80,000-$100,000 annual salary depending on experienceComprehensive health, dental, and vision insuranceProfit-sharing via automatic 401k contributions (plus matching)Flexible, fully remote, asynchronous working environment (except for occasional travel within the U.S.)Opportunity to build a media brand from the ground floorAccess to numerous professional development trainings, including both our own courses and our partners’How to applyApplications are officially open. The first phase of the process includes submitting several video responses and short written pieces. Please use YouTube, Vimeo or Loom to share your videos.

Video 1: Why are you interested in the role? [60 seconds]Video 2: What is an example of a major content-related initiative you conceived and executed in a previous project or job? What was the process? What tools did you use? What was the outcome? [120 seconds]Written 1: A link to an existing piece of “how-to” content (written or otherwise) that you created [750 words max]Written 2: What do you think is the biggest opportunity for Forte Labs/Building a Second Brain? How would you move this forward? [750 words max]References: will be checked ahead of the offer

Important: This application must be completed in one sitting. There are 2 videos and 2 written questions for you to submit. We recommend you review the whole application first so you can plan for the appropriate time to complete the application before hitting submit. The job posting will close on Saturday, July 31, 2021.

From the initial submissions, we’ll select a smaller group for interviews, and then a set of finalists will be asked to complete a paid project and/or an in-person interview. You should be available to start on September 1st.

*Forte Labs, LLC is an Equal Opportunity Employer. Individuals seeking employment at Forte Labs are considered without regard to race, ethnicity, color, age, sex, religion, national origin, ancestry, pregnancy, sexual orientation, gender identity, gender expression, genetic information, physical or mental disability, registered domestic partner status, caregiver status, marital status, veteran or military status, citizenship status, or any other legally protected category.

Apply for the Director of ContentFrom the initial submissions, we’ll select a smaller group for interviews, and then a set of finalists will be asked to complete a paid project and/or an in-person interview. You should be available to start Wednesday, September 1, 2021.

*Forte Labs, LLC is an Equal Opportunity Employer. Individuals seeking employment at Forte Labs are considered without regard to race, ethnicity, color, age, sex, religion, national origin, ancestry, pregnancy, sexual orientation, gender identity, gender expression, genetic information, physical or mental disability, registered domestic partner status, caregiver status, marital status, veteran or military status, citizenship status, or any other legally protected category.

Subscribe below to receive free weekly emails with our best new content, or follow us on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, or YouTube. Or become a Praxis member to receive instant access to our full collection of members-only posts.The post Forte Labs Director of Content appeared first on Forte Labs.

July 12, 2021

Tiago’s 2021 Mid-Year Review

One of the most useful exercises I perform each year is a “mid-year” review in June or July.

It’s great to set ambitious goals at the start of the year, but that plan often doesn’t survive contact with the real world for more than a few weeks.

And looking back on the past year around January 1 is also a useful exercise, but by then it’s too late to make major changes.

But halfway through the year, there is a brief, liminal moment. You have enough information to know whether your goals are properly formulated, but there is also enough time left to change direction and finish the year stronger than you started.

This is a summary of my personal reflection process for mid-year 2021, which mainly involves a lot of reading, taking long walks, and journaling. Its purpose is to check in with the goals I set at the beginning of the year, celebrate any victories, and make any course corrections based on what I’ve learned.

1. Grow my email newsletter to 100,000 subscribersThis is my most important goal of the year, since the overall size of my audience drives every other business goal. In 2020 my weekly newsletter grew rapidly from 9,483 to 40,887 subscribers, or by more than 30,000. In the first half of 2021 I only added another 8,000, for a total of 48,352. In other words, growth slowed from 2,617 new subscribers per month last year to 622 per month in 2021, a 77% drop.

I’ve only begun to investigate why, but I have a couple solid hypotheses:

Email list growth naturally follows an “S curve” as strategies that worked before become less effective, and existing sources of new subscribers run dryI spent little time and attention on it so far this year, in favor of growing the size of our cohorts and building the teamThe deeper, underlying reason behind this plateauing is that I think I’ve reached the limits of what I can do as a solo creator sending emails on my own. I don’t have much interest in doing anything besides creating the content itself. I need someone to own this area of the business, from continuously finding new sources of subscribers, to managing the details of ConvertKit, to documenting and standardizing all the ways we use the email platform.

Half of this job will fall to our new Director of Course Operations, Dr. Monica Rysavy, who is working with our newly promoted Chief of Staff, Betheny Swinehart, on the operational side of email marketing. The other half will be the responsibility of the new Director of Content I’m hiring soon, who will manage the content side.

Besides building up this capability as a team, I’ve hired a promotional agency to work with us on the launch of my book over the next year. They’ve worked with some of the biggest names in online media on some of the biggest book projects of recent years, and will help us develop and execute a strategy for growing our audience as the primary lever in making the book a success.

2. Maintain our focus on our two flagship coursesI succeeded in staying focused on our flagship courses this year! Partly because of the accountability of having promised to do so on this blog.

I’m now beginning to think of our educational ecosystem in terms of three flagship courses: Building a Second Brain (BASB), Write of Passage, and The Art of Accomplishment (taught by our external partner Joe Hudson). Each of these courses trains people in an extremely important, yet challenging skill that can have a dramatic impact on their lives and careers – knowledge management, modern writing, and personal growth, respectively. They’re each taught by a uniquely qualified instructor, who is also dedicated to building it into a sizable business.

Each of these courses also checks all the boxes I look for in sustainable CBCs:

Includes both concepts and practical implementationProfessional/business-focused but including a strong personal growth componentDriven by or leveraged by technology and the InternetThese three factors are the moat around our programs. They are difficult for others to copy and require skills not commonly found together. They straddle traditional boundaries of education, which means existing institutions are unlikely to offer something similar. And they have some inherent friction which makes them difficult to scale easily, which means venture-funded startups are unlikely to take them on either.

When I think about these three programs as a symbiotic trio, I think their potential is basically unlimited. There is no reason they can’t each become a $10 million dollar business in the next 5 years. Especially when we take into account vertical integration into books, coaching, paid subscriptions, and physical products around the same intellectual property, each of them is like an extended universe unto itself.

3. Run a live cohort with 2,000 students at onceWe got close on this one already, with cohort 12 of BASB reaching just over 1,600 participants including both new students and returning alumni. It was a wild experience, akin to putting up a pop-up liberal arts college in the span of a couple months.

We tried a lot of different ways of making such a large group continue to feel intimate and personal. We had 30 Alumni Mentors delivering smaller breakout sessions each week. We created opt-in “feedback pods” where students could join a small group of students to discuss their progress and get feedback from each other. And we doubled down on making Circle the “town square” of the program. Hearing that people wanted a more real-time, chat-like environment, we also created a dedicated Slack just for this cohort, which we may reuse in the future.

Although each of these experiments was promising, I think we’re reaching a scale where we need to start putting limits on the size of the cohorts. I’m considering limiting the next one to 1,000 new students, plus 500 returning alumni. After that we can assess and decide whether to raise the cap incrementally, or standardize on that size so we can really master it. So much of the complexity of running cohorts comes from the uncertainty around how many students to expect, and although this limit would forgo some revenue, it will make our planning and the resulting student experience much better.

I’m also considering increasing the number of cohorts per year, from two to four, so we can continue serving more customers despite the enrollment limits. That would allow me to hire year-round staff instead of having to recruit a new group of mentors every cohort. And it would help us make longer-term decisions, in terms of semesters and academic years, instead of everything being a one-off.

4. Make operational excellence and customer service central pillars of our businessIt’s been incredible to see the explosive interest in CBCs (Cohort-Based Courses) over the last year. The field is unrecognizable compared to when I started. Investment is pouring in, new startups are being formed, and it seems like cohorts are quickly becoming the default format for high-impact, premium educational experiences.

As excited as I am to see all this interest, it also means the landscape is becoming far more competitive. You can’t get away with a few casual Zoom calls anymore. Customers expect high production values, strong follow-up on their questions and comments, practical feedback on their work, real relationship-building amongst their fellow students, and a consistent and distilled experience throughout. I think we’re going to see a shakeout in the next couple years with quirky, personality-driven CBCs taught by solo instructors giving way to more professional, commercial programs run by teams. The plane of competition will shift from personal loyalty to operational excellence.

There are so many components and aspects to a CBC, and all of them are advancing rapidly. Which means we have a lot of work to do to discover, understand, test, and integrate new components. For example, here are some of the major areas of improvement we have our eyes on:

Data collection, management, and visualization – How do we combine data from all the different platforms and tools we use and turn it into tangible improvements to the student experience?Mentor recruitment, training, and support – How do we double down on Alumni Mentors, and make their breakout sessions the most compelling and impactful part of the program?Evaluation and testing – How do we improve and expand the Second Brain Snapshot that students take before and after the course, and turn it into a personalized curriculum for the program itself?Live studio production – How do we upgrade the quality and reliability of our live broadcasts for the instructor, course staff, Alumni Mentors, and students?Calendaring and notifications – How do we radically improve the course calendar, and its ability to blend seamlessly into students’ lives with useful reminders without being intrusive?Video editing and distribution – How do we create a dedicated system for recording, editing, uploading, and distributing recordings of class sessions?We’ve laid the foundation for making major investments into these areas, including hiring a Director of Course Operations, our first Customer Support Rep, and creating a series of internal systems to allow for more hiring in the coming months. We also built a solid support portal, including many FAQs and a support ticketing system for both the courses and inquiries in general.

5. Launch 100 Cohort-Based Courses through the Keystone AcceleratorWe launched the first cohort of the Keystone Course Accelerator late last year, with about 35 participants teaching a wide variety of subjects.

The program produced some outstanding successes, but we also learned a difficult lesson: that there are SO MANY aspects of running a successful CBC, it isn’t realistic to expect any program to cover all or most of them. A CBC is a relatively advanced, mature product, meaning you need to have many foundational levels in place in order to make it work: an engaged audience of significant size; a team (or reliable contractors) you can lean on; an understanding of your customers and the most important need you can solve; an existing educational program that you know reliably produces great outcomes.

I think this is the biggest blindspot that the CBC craze is missing: people are trying to make a CBC as their first ever paid product, or in some cases, the first significant project they deliver online. It’s entirely feasible to attract some friends or colleagues for the first and maybe second cohorts, but after this close circle is quickly exhausted I think we’re going to see many instructors realize they don’t have any foundation in place to keep it going, much less scale it.

So we’re pivoting Keystone to focus only on existing education businesses who have that foundation in place, and are ready for growth. Instructor Billy Broas is going to zero in like a laser on the true bottleneck for such businesses: the core messaging that drives every other tactic, strategy, promotion, and piece of content. Messaging (including positioning, storytelling, and differentiation) that is truthful, authentic, and most importantly of all, powerfully effective in moving people to take action. Messaging is the keystone of a successful online education business, and no one does it better than Billy.

6. Redesign BASB brand identity and apply it to new websiteWe kicked off this project last month, and the two designers I’m working with are well on their way. The early results I’ve seen are incredibly promising. We are creating a comprehensive visual system for the BASB brand that will give us years of runway. It will provide the cohesiveness and shared context we need to extend the ideas developed in the course into books, workbooks, videos, local events, physical products, coaching services, subscriptions, and other media.

I don’t have anything to share just yet, but stay tuned as I begin to share bits and pieces of the brand as it emerges. It will culminate in a completely new buildingasecondbrain.com website by the end of the year.

7. Grow YouTube following to 50,000I’ve mostly ignored YouTube for the first half of the year, as my attention has been dedicated to finishing my manuscript (which is due at the end of this month!). But I have big plans for it in the second half of the year.

The first step has been remodeling our garage into a gorgeous, 360 square foot studio. I’ll have a lot more to share on this project soon as it’s been a fascinating learning experience. But the main goal is to have a completely dedicated space for not only working from home in general, but filming and livestreaming as well. We made every decision to maximize the usefulness of every part of the studio for creating video content.

In the meantime, here’s a playlist of periodic construction updates I’ve shared along the way.

8. Hire a personal trainer and train with them 90 timesI started working with a personal trainer I found on Yelp on February 11, and so far we’ve trained 37 times, about twice a week on average. This has been an interesting way of framing it for myself, because 37 doesn’t seem like a very dramatic or impressive number. But the 5 months of progress have already been transformational, like a whole body education in what it means to be holistically strong and flexible.

I’ve had to learn how to stay consistent and make room in my schedule for two hour-long sessions per week. I’ve had to learn how to eat better, before my workout to ensure I have energy, and after to make sure I’m capitalizing on my effort. I’ve learned a ton about correct posture and form, the relationships between body parts, and how to avoid injury. The pain and tension I’ve had in my lower back for years is gone, and I have more energy and sleep better than ever.

It’s kind of amazing in retrospect that so many of us walk into gyms and begin lifting weights without any training as to how to do it properly. I’ve had to unlearn many bad habits and correct mistaken assumptions gleaned from TV or watching others. It’s been a relief to accept that I don’t have the self-discipline right now to exercise regularly on my own, and to feel comfortable outsourcing that self-discipline to someone else.

But I think the biggest benefit has been psychological. I have a newfound pride in myself that I am taking care of my most fundamental and important responsibility, my health. It makes me happy that I am setting an example for my son, that health comes first. I’m beginning to think of myself as a cognitive athlete. It may not matter how fast I can run or how many pounds I can lift, but to the extent my body is the foundation of my mind, I depend just as much on it as any pro athlete.

9. Becoming a parentThis wasn’t on my list of goals, but becoming a father has of course been the most monumental change of the past year. Our son is almost 9 months old, and over the past 6 months his personality has really started to emerge.

It feels in many ways like I’ve entered a different dimension. An alternate reality that operates by different rules. Things that seemed critically important – launching new products, spending as many possible hours per week in deep focus, traveling extensively – suddenly don’t seem important at all. Or even desirable.

Other things that I’d never given much thought to have become paramount – improving our family’s dietary habits, spending as much time as possible with my parents, understanding and healing intergenerational trauma (I’m reading a book called It Didn’t Start With You that has been very moving on this subject).

I think the deepest shift is that my own life – my goals, priorities, and freedom – is not the central focus of my life anymore. Instead, my attention is dedicated to what my spouse and my son need, want, and will become. It’s jarring to realize that I’ve had the great privilege of focusing entirely on myself until now.

Becoming a parent has also changed how I view a lot of “life advice.” A lot of advice that makes complete sense for single 20-somethings or childless 30-somethings makes absolutely no sense once you have kids. They are like different worlds with little communication between them. As I approach 40 and identify less and less with hard-charging 20-somethings giving their career or business every last drop of their energy, I can see that the content I create and the lessons I teach are going to change as well.

As a parent, I have far less time, and especially solo, focused time, than I did previously. My sleep is far more unpredictable. We are fortunate to have childcare until about 3pm each weekday, but that means that my workday effectively ends at 3pm. Whereas in the past I would get a whole second wind to work through the afternoon and into the evening.

Now I’m looking to other sources for inspiration. Not so much productivity gurus, but fellow parents who seem to live with ease and grace. Not so much the puritanical extremes of human performance, but the messy middle. I’m interested in leaders and business owners who are somehow able to maintain and even expand the impact they have without sacrificing the needs of their growing families. I feel like a beginner again, and that is a precious gift.

3 areas of innovationI’ve long had this idea that the business just needed to mature, and then we’d reach this mythical plateau of stability where we’d have everything figured out and just sail smoothly into the horizon.

But now I understand that the only plateau is the plateau of stagnation. That change is the only constant, and it is our prerogative to get good at navigating it.

I’m starting to realize that every single year of the business requires a different strategy and even business model. We are growing quickly, approximately doubling revenue each year. Each doubling demands a different mix of goals, different roles for our team, and different kinds of partnerships and advisors.

From 2013 to 2017 I was in “solo creator” mode, experimenting with a broad range of projects, pursuing whatever resonated with me. In 2018 my Building a Second Brain course really took off, and the whole business reoriented to support it.

In 2020 we started hiring, ushering in a new stage of building a team that could deliver the course to a much larger number of students. We now have a team of 8 across two flagship courses. It’s been a wonderful experience to go beyond what I can deliver by myself, to watch others learn and grow alongside me, and to envision our future as a real company.

Now it’s time to shift once again. As strange as this sounds, it wasn’t until the past year that I truly committed to our future as an education business. There seemed to be so many interesting topics to learn about, and so many promising pathways to explore. Why would I commit to just one?

But the growth of the course alongside my newfound conservatism as a parent have combined to make it very clear to me that BASB is my big idea, the course is the breakout product, and the release of my book in just about a year is an opportunity to make it the definitive methodology on knowledge management, and productivity in general, on the planet. What GTD did for personal productivity, we can do for personal knowledge management (PKM).

Interestingly, this leads me to the conclusion that there are really only three areas of life that I want to innovate on:

My personal growthMy child’s education and upbringingIdeas related to PKMEach of these areas are ones where 1) I believe I can make a real difference, and 2) The existing defaults if I don’t act aren’t very good. One is for myself, the second for my family, and the third for the wider world, like concentric circles.

All the other areas of life, such as my marriage, home, family life, hobbies and free time, friends, and the running of the business, I want to be as mundane and boring as possible. Not “boring” in the sense that it lacks excitement, but in the sense that it draws on the timeless wisdom of the past instead of trying to invent a radical new future. We’re even considering buying a mini-van.

I take seriously Gustave Flaubert’s advice to “Be regular and orderly in your life, so that you may be violent and original in your work.” I’m discovering that the more violently original I want that work to be, the higher the percentage of the rest of my life that needs to be regular and orderly.

The post Tiago’s 2021 Mid-Year Review appeared first on Forte Labs.

July 5, 2021

The Box: Twyla Tharp on Project-Based Organizing

In my PARA Method, I teach people how to organize all their digital notes and files using a simple, 4-part system.

Your computer is your working environment for many of your waking hours. Until you take control of it and design it to support the kinds of thinking you want to do, every minute spent there will continue to feel taxing and distracting.

The PARA Method starts with the observation that every piece of information can be saved in one of four categories, based on how actionable it is:

Projects: information relevant to your currently active projectsAreas: information relevant to the major responsibilities of your lifeResources: other information that might become relevant in the futureArchives: inactive information from the previous three categoriesThis scheme is possible because we aren’t organizing information according to what it means, but according to how we’ll likely use it. Our current priorities and goals become the filter that helps us drastically reduce the amount of information we have to pay attention to at any given time.

I receive a lot of questions about how to implement PARA, including extremely detailed and specific questions about where a certain fact or quote or note should go. But the decision of where to put something is very forgiving, because we always have the powerful search capability to find what we need regardless of where it’s located.

The most important principle of PARA is that all the content related to each one of our most important projects is in one central, easily accessible place (whether that is a folder, a digital notebook, or a tag). Areas and resources are less actionable, and thus less important. But projects represent the frontier of our attention and the central thrusts of our most challenging endeavors.

I recently encountered a wonderful example of how this straightforward principle can be manifested in the medium of dance choreography. It is from the book The Creative Habit by Twyla Tharp, in which she describes the working habits and routines that have propelled her through a prolific career of more than 160 choreographed works, including 129 dances, 12 television specials, six major Hollywood movies, four full-length ballets, four Broadway shows, and two figure skating routines. Dance might seem like the creative medium that could least benefit from “organizing.” Yet her technique shows that creativity always emerges out of raw material drawn from other sources.

Tharp calls her approach “The box.” Every time she begins a new project, she takes out a foldable file box and labels it with the name of the project. Into the box she puts anything and everything related to the project, like a swirling cauldron of creative energy.

Any time she find a new piece of material ( such as a mix tape, a patch of fabric, a video of a dance routine, or a photo from an art gallery) she always knows where to put it – in the box. Any time she works on that project, she knows exactly where to look – in the box. It’s a stunningly simple system that reveals just how regular and mundane our creative habits can be. We don’t need complex, sophisticated systems to be able to produce complex, sophisticated works.

I compiled Tharp’s comments on how she uses the box from various places in her book. Her comments are the best possible guide on how to use “project-based organizing” to further your creative ambitions without getting bogged down in busywork. All the excerpts below are taken directly from her book, and I’ve bolded certain passages for emphasis.

Twyla Tharp and “The Box”

I start every dance with a box. I write the project name on the box, and as the piece progresses I fill it up with every item that went into the making of the dance. This means notebooks, news clippings, CDs, videotapes of me working alone in my studio, videos of the dancers rehearsing, books and photographs and pieces of art that may have inspired me.

The box documents the active research on every project. For a Maurice Sendak project, the box is filled with notes from Sendak, snippets of William Blake poetry, toys that talk back to you. I’m sure this is the sort of stuff that most people store on shelves or in files. I prefer a box.

There are separate boxes for everything I’ve ever done. If you want a glimpse into how I think and work, you could do worse than to start with my boxes. The box makes me feel organized, that I have my act together even when I don’t know where I’m going yet. It also represents a commitment. The simple act of writing a project name on the box means I’ve started work.

The box makes me feel connected to a project. It is my soil. I feel this even when I’ve back-burnered a project: I may have put the box away on a shelf, but I know it’s there. The project name on the box in bold black lettering is a constant reminder that I had an idea once and may come back to it very soon.

Most important, though, the box means I never have to worry about forgetting. One of the biggest fears for a creative person is that some brilliant idea will get lost because you didn’t write it down and put it in a safe place. I don’t worry about that because I know where to find it. It’s all in the box.

They’re one hundred percent functional; they do exactly what I want them to do: hold stuff. I can write on them to identify their contents (you wouldn’t do that with a thousand-dollar cherry file cabinet). I can move them around (which is also hard to do with a heavy wood filing system). When one box fills up, I can easily unfold and construct another. And when I’m done with the box, I can ship it away, out of sight, out of mind, so I can move on to the next project, the next box.

Easily acquired. Inexpensive. Perfectly functional. Portable. Identifiable. Disposable. Eternal enough. Those are my criteria for the perfect storage system. And I’ve found the answer in a simple file box.

That’s the true value of the box: It contains your inspirations without confining your creativity.

On developing the Billy Joel show Movin’ OutIt was one of those rare moments: an instant deal. We shook hands and he left. That’s the moment I started my Billy Joel box for the show Movin’ Out.

First in: my precious twenty-minute tape. Next in: two blue index cards. I believe in starting each project with a stated goal. Sometimes the goal is nothing more than a personal mantra such as “keep it simple” or “something perfect” or “economy” to remind me of what I was thinking at the beginning if and when I lose my way. I write it down on a slip of paper and it’s the first thing that goes into the box.

In this case, I had two goals. The first was “tell a story.” I felt that getting a handle on narrative in dance was my next big challenge, plus I wanted to find out what happened to Brenda and Eddie, the “popular steadies.”

The second was “make dance pay for the dancers.” I’ve always been resentful of the fact that some of the so-called elite art forms can’t survive on their own without sponsorship and subsidies. It bothers me that dance companies around the world are not-for-profit organizations and that dancers, who are as devoted and disciplined as any NFL or NBA superstar, are at the low end of the entertainment industry’s income scale. I wanted this Broadway-bound project not only to elevate serious dance in the commercial arena but also to pay the dancers well.

So I wrote my goals for the project, “tell a story” and “make dance pay,” on two blue index cards and watched them float to the bottom of the Joel box. Along with the tape, they were the first items in the box and they sit there as I write this, covered by months of research, like an anchor keeping me connected to my original impulse.

In the box you’ll also find my notebooks containing all the clips and images and scrawls to myself that I file away to jog my memory. There are tchotchkes in the box as well, all of which link me to some essential aspect of the project.

Eventually, the material for this show filled up twelve boxes.

That’s how a box is like soil to me. It’s basic, earthy, elemental. It’s home. It’s what I can always go back to when I need to regroup and keep my bearings. Knowing that the box is always there gives me the freedom to venture out, be bold, dare to fall flat on my face. Before you can think out of the box, you have to start with a box.

The box is not a substitute for creating. The box doesn’t compose or write a poem or create a dance step. The box is the raw index of your preparation. It is the repository of your creative potential, but it is not that potential realized.

My box is like the journalist’s notes. It’s the “reporting” routine I follow before creating a piece. If the quality of a journalist’s work is a direct function of how much background material he sifted through, how many people he talked to, how many times he went back to his sources to challenge or check up on their statements—that is, how diligent and clever he was in assembling his research—then the quality of my creative output is also a function of how diligent and clever I’ve been in filling up my boxes.

Sadly, some people never get beyond the box stage in their creative life. We all know people who have announced that they’ve started work on a project—say, a book—but some time passes, and when you politely ask how it’s going, they tell you that they’re still researching.

Weeks, months, years pass and they produce nothing. They have tons of research but it’s never enough to nudge them toward the actual process of writing the book. I’m not sure what’s going on here. Maybe they’re researching in the wrong places. Maybe they like the comfort zone of research as opposed to the hard work of writing. Maybe they’re just taking procrastination to a new extreme. All I know for sure is that they are trapped in the box.

There’s one final benefit to the box: It gives you a chance to look back. A lot of people don’t appreciate this. When they’re done with a project, they’re relieved. They’re ready for a break and then they want to move forward to the next idea.

But the box gives you the opportunity to reflect on your performance. Dig down through the boxes archaeologically and you’ll see a project’s beginnings. This can be instructive. How did you do? Did you get to your goal? Did you improve on it? Did it change along the way? Could you have done it all more efficiently?

I find the box is most useful at three critical stages: when you’re getting going, when you’re lost, and after you’ve finished (that’s when you can look back and see the directions you didn’t take, the ideas that intrigued you but didn’t fit this time around and might be the start of your next box).

A documentary on Tharp’s 6-decade career, Twyla Moves, was released in March 2021, including extensive archival footage from her past works and interviews. There are also segments on how she worked with dancers remotely during COVID. The film is only available via a PBS subscription, but that webpage includes a number of short clips that should give you a taste of her style:

Subscribe below to receive free weekly emails with our best new content, or follow us on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, or YouTube. Or become a Praxis member to receive instant access to our full collection of members-only posts.The post The Box: Twyla Tharp on Project-Based Organizing appeared first on Forte Labs.