R.J. Stowell's Blog: rjsomeone, page 36

November 3, 2019

Childhood's End

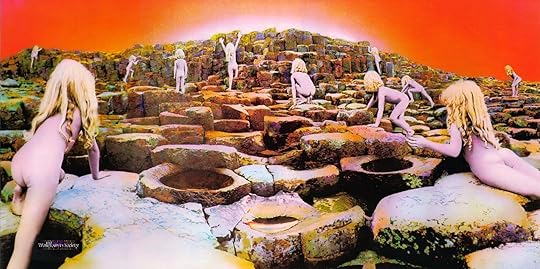

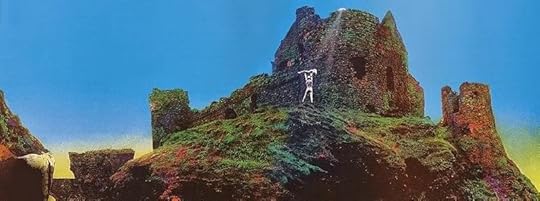

Houses of the Holy

(AM9)Artist: Led ZeppelinProduced by: Jimmy PageReleased: March 28, 1973Length: 40:58Tracks: 1) The Song Remains the Same (5:32); 2) The Rain Song (7:39); 3) Over the Hills and Far Away (4:50); 4) The Crunge (3:17); 5) Dancing Days (3:53) 6) D’yer Mak’er (4:23); 7) No Quarter (7:00); 8) The Ocean (4:31); Players: Jimmy Page – lead guitar, acoustic guitar, 12 string, pedal steel, theramin; Robert Plant – vocals; John Paul Jones – bass, keyboards, synthesizer bass, backing vocals; John Bonham – drums, backing vocals

Houses of the Holy

(AM9)Artist: Led ZeppelinProduced by: Jimmy PageReleased: March 28, 1973Length: 40:58Tracks: 1) The Song Remains the Same (5:32); 2) The Rain Song (7:39); 3) Over the Hills and Far Away (4:50); 4) The Crunge (3:17); 5) Dancing Days (3:53) 6) D’yer Mak’er (4:23); 7) No Quarter (7:00); 8) The Ocean (4:31); Players: Jimmy Page – lead guitar, acoustic guitar, 12 string, pedal steel, theramin; Robert Plant – vocals; John Paul Jones – bass, keyboards, synthesizer bass, backing vocals; John Bonham – drums, backing vocals

Again, like Wish You Were Here and Joni Mitchell's Court and Spark, a follow-up to Led Zeppelin IV (ZOSO, Runes) was daunting, but although Houses of the Holy didn't attain the lofty commercial success of its predecessor, a mature genius is scattered throughout to make it an arguably more fascinating and equally diverse listening experience. Led Zeppelin strove, generally successfully, to develop and advance their sound by consistently incorporating new ideas, from reggae (the often maligned, in particular by John Paul Jones, "D'yer Mak'er") to the James Brown inspired funk (the bottom-heavy and tricky time signature of "The Crunge"). Jimmy Page's tough stomping lick, which opens "The Ocean," remains one of his finest, and the John Paul Jones showcase "No Quarter" with its dreamy, spooky piano and loud/soft dynamics was a concert showcase and one of the band’s most sublime moments. Adding strings to bring new textures to the acoustic "The Rain Song," at nearly eight minutes the disc's longest and most complex track, served to create what may be the most beautiful song in rock music (bar "God Only Knows"). From the Childhood’s End album cover (my all-time favorite) to the sonic landscapes inured through impeccable musicianship, Houses of the Holy is Led Zeppelin's penultimate achievement. It shines often more brightly than ZOSO, but fails at times in its new direction and experimentation. ZOSO, on the other hand, is the pinnacle of who Led Zeppelin would become and carved the way for the confidence that Houses exemplified.

From the opening thrill of "The Song Remains The Same," Houses Of The Holy strikes one as the most intelligent and considered of all Led Zeppelin albums in that it doesn't always go straight for the most obvious approach, songs are allowed to unfold and breath before they take shape.

Published on November 03, 2019 02:55

November 2, 2019

Grace Slick

80 years and aging Grace-fully.

If you’re looking for our Jefferson Airplane coverage, check out the Featured Article on the sideboard. Join us Monday for our complete coverage!

If you’re looking for our Jefferson Airplane coverage, check out the Featured Article on the sideboard. Join us Monday for our complete coverage!

Published on November 02, 2019 05:12

October 31, 2019

Zeppelin: Let's Get This Out of the Way - Part 1

Over the next week AM will devote its time to Led Zeppelin. We begin here with the plagiarism controversy.

Over the next week AM will devote its time to Led Zeppelin. We begin here with the plagiarism controversy.Romeo and Juliet by William Shakespeare. Othello: Shakespeare. MacBeth: Shake. No, no and no: Arthur Brook/Ovid (R+J); Hecatommithi, a novella by Cinthio (Othello); Holinshed's Chronicles ("The Scottish Play") - but if you said so, you'd sound like an idiot. Because you would be. According to Ecclesiastes, there is nothing new under the sun, so frankly, shut the hell up already about Led Zeppelin. The allegations have indeed brought lawsuits, mostly (five to be exact) settled out of court discretely with the evidence truncated, and in the most famous case, "Whole Lotta Love," the song credits amended to include Willie Dixon, who claimed that Robert Plant used lyrics from his song "You Need Love." Here we go: "You've got yearnin' and I got burnin'/ Baby you look so sweet and cunnin'./ Baby way down inside, woman you need love." Willie Dixon obviously was the first person ever to say what guys say in the heat of the moment (wait, did I just steal that from Asia?).

Sorry, I get it, intellectual property, blah blah blah, but this is simply fucking to music - the improv of sex - and it doesn't belong to Plant, nor does it belong to Dixon. The Small Faces' Steve Marriot has a far better case with Plant's lifted stylings, but push to shove reality: Romeo and Juliet: Shakespeare; "Whole Lotta Love:" Zeppelin. This (and only this) is the sexiest, dirtiest song ever recorded and not Willie Dixon's Song of the South rendition. Muddy Waters' take, bluesy and incredible as it is, holds nothing on Zeppelin's. (Not a soul, by the way, has challenged John Williams for lifting the Star Wars Theme straight from Erich Wolfgang Korngold's incidental music for King's Row. Why? Because Korngold's original pales in comparison.)

Sorry, I get it, intellectual property, blah blah blah, but this is simply fucking to music - the improv of sex - and it doesn't belong to Plant, nor does it belong to Dixon. The Small Faces' Steve Marriot has a far better case with Plant's lifted stylings, but push to shove reality: Romeo and Juliet: Shakespeare; "Whole Lotta Love:" Zeppelin. This (and only this) is the sexiest, dirtiest song ever recorded and not Willie Dixon's Song of the South rendition. Muddy Waters' take, bluesy and incredible as it is, holds nothing on Zeppelin's. (Not a soul, by the way, has challenged John Williams for lifting the Star Wars Theme straight from Erich Wolfgang Korngold's incidental music for King's Row. Why? Because Korngold's original pales in comparison.)More importantly, this writer's purview is not that Led Zeppelin (Plant in particular) can claim intellectual ownership of lyrics like those in "The Lemon Song," which clearly reconstruct "Killing Floor" by Chester Burnett (a.k.a. Howlin' Wolf), but that lawsuits and purported plagiarism are absurd when one analyzes both the history of the blues, and its construct. If Plant indeed needs to include Howlin' Wolf in the credits to "The Lemon Song," then Howlin' Wolf must also qualify "Killing Floor" by including Robert Johnson. By extension, Led Zeppelin, Howlin' Wolf and Robert Johnson must re-credit their sexually explicit "lemon" tracks with the addition of Joe Williams for his 1929 penned tune, "I Want it Awful Bad," which is, if not the original, at least the oldest existing lyrics to take the lemon in hand (so to speak): "You squeezed my lemon,/ Caused my juice to run." To emphasize the details: not Zeppelin, not Burnett, not Johnson, not Roosevelt Sykes ("She Squeezed My Lemon"), not Memphis Minnie nor Sonny Boy Williamson can lay claim to the lyrics of Joe Williams.

Equally compelling is the "Killing Floor" reference. The killing floor is classic/timeless blues phrasing that initially referred to the slaughterhouse. After the Civil War, many black migrants found work in the slaughterhouses on the "killing floor," a term that came to mean hitting rock bottom. Plant's use of the lyric as a white British lyricist in "The Lemon Song" is ridiculous, but again, it is far from plagiarism.

The point is simple. So much energy and clever naysaying on the web and in print goes into proving that Plant and Page plagiarized the blues greats, overlooking the inherent plagiarism in the genre's construct: blues borrows.

By the way, there really was a William Shakespeare who wrote 37 plays and 154 sonnets. Not a soul among us reads Sir Francis Bacon's Hamlet.

Published on October 31, 2019 04:51

October 29, 2019

Miles in California

Read Miles From Nowhere on Kindle Unlimited for FREE or get your copy on Amazon. AM is supported by sales from Miles and from Jay and the Americans. Unlike Patreon, when you offer up your hard-earned cash, you get something in return. Want a hand-signed edition of either novel, send me an email. Enjoy.

Published on October 29, 2019 03:33

October 27, 2019

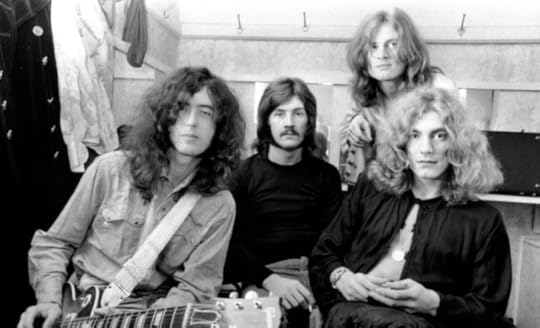

Led Zeppelin 2 - 50 Years Ago

During September 1968, The New Yardbirds (Jimmy Page, John Bonham, John Paul Jones and Robert Plant) toured Scandinavia performing Yardbirds material as well as new material like "Communication Breakdown," "I Can't Quit You, Baby," "Babe I'm Gonna Leave You," and "How Many More Times." That same month, at Keith Moon's mocking ("That'll go down like a lead zeppelin), The New Yardbirds were renamed Led Zeppelin, and on October 15, 1968, Led Zeppelin made their debut at Surrey University. Soon after, the group began touring the U.S., backing up headliners like Vanilla Fudge and The MC5. Nearly instantaneous recognition followed. On January 31, 1969, Led Zeppelin opened for Iron Butterfly, who, due to "In a Gadda Da Vida," was one of the hottest bands in the world. Led Zeppelin received such resounding approval from the audience that Doug Ingle, lead singer for the Butterfly scrapped the remainder of the tour. Led Zeppelin had become headliners in their own right.

Led Zeppelin would end up opening for Vanilla Fudge with the band name mistakenly advertised as "Len Zeffelin." Doesn't quite have the same ring to it. No one had ever heard anything like it. By the time Zeppelin left the stage, psychedelia was dead and heavy metal was born. Poor Vanilla Fudge.

Within eight months of their official debut, Zeppelin was at the top of the bill at the Playhouse Theater in London, and the Pop Proms at the Royal Albert Hall. On October 17, 1969, a year after the band's inception, Zeppelin played Carnegie Hall, ending a ban on rock groups caused by the Rolling Stones' antics in 1965.

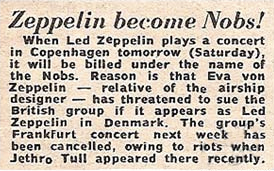

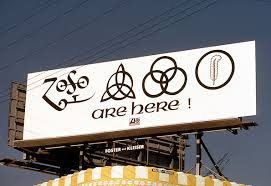

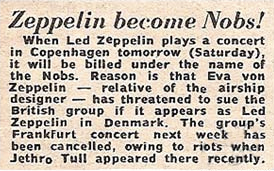

While playing in Denmark, Eva von Zeppelin, a relative of the designer of the airship, Ferdinand von Zeppelin, threatened to sue the band if they used the name for their gig in Copenhagen. For that one show, Led Zeppelin played under the alias, The Nobs.

While playing in Denmark, Eva von Zeppelin, a relative of the designer of the airship, Ferdinand von Zeppelin, threatened to sue the band if they used the name for their gig in Copenhagen. For that one show, Led Zeppelin played under the alias, The Nobs.

The first LP took but 36 hours of studio time, including mixing and mastering and was fit into the band's hectic touring schedule. The band was without a label and on the clock to the tune of £1,782, or roughly $3,500. Released January 12, 1969, in the U.S., Led Zeppelin climbed to No. 10 in the U.S. and to No. 6 in the U.K. (Released March 28th). Until the late 60s, producers placed microphones directly in front of the amplifiers and drums. For Led Zeppelin, Page placed an additional microphone some distance from the amplifier (as far as twenty feet) and then recorded the balance between the two. By adopting this "distance equals depth" technique, Page was among the first producers to record a band's "ambient sound;" the distance of a note's time-lag from one end of the room to the other. Led Zeppelin was the first album to be released in stereo-only form; at the time, the practice of releasing both mono and stereo versions was the norm. The LP was the virtual Sgt. Pepper of Heavy Metal Blues.

Somehow, this band of misfits broke down the walls of critics (who abhorred the first LP) going straight for the audience, and won with their interpolation of blues, garage rock, soul, shuffle, psychedelic vibes and violin-bowed guitar fer chrissakes; they were over-the-top and minimalist, often in the same song. With tracks about hobbits, mythology and sex in equal form, Led Zeppelin made it look easy.

Somehow, this band of misfits broke down the walls of critics (who abhorred the first LP) going straight for the audience, and won with their interpolation of blues, garage rock, soul, shuffle, psychedelic vibes and violin-bowed guitar fer chrissakes; they were over-the-top and minimalist, often in the same song. With tracks about hobbits, mythology and sex in equal form, Led Zeppelin made it look easy.

Led Zeppelin's debut album (AM8) is a monster of barely contained monolithic intensity (yeah pompous as shit). The album's artistic success hinges on the tension between the reflective/creative/experimental natures of Jimmy Page and John Paul Jones rubbing elbows with the bombastic/flamboyant/amped-up traditionalism of Robert Plant and John Bonham. When these tensions interact fireworks ensue. These are basic musical forms, blues, folk and bluegrass, taken to new extremes of sonic density and timbrel heaviness. Here was a conscious move to unearth the swamp blues from which all rock and roll originated and, at the same time, revitalize the format for a contemporary audience. The likes of The Yardbirds, The Small Faces, John Mayall's Bluesbreakers and Joe Cocker fronted a movement that occasionally bruised the singles chart, but was primarily an underground faction. Hendrix, Beck and Cream pushed this to another, darker dimension and Zeppelin's debut was an integral player in the cadre that opened the floodgates to a bevy of progressive bands whose growing obsession with self-indulgent, sprawling epics lead to an inevitable implosion and the backlash that was punk. That's a lot of rock history in one breath: Led Zeppelin was the catalyst for it all. By year's end, the band released Led Zeppelin II (Led Zeppelin II, quickly moved up to No. 1 in both the U.S. and the U.K., remaining on the charts for 98 weeks in the States and an astounding 138 weeks in Britain.)

As we've reported, Led Zeppelin chose to skip Woodstock for their first American tour, playing the Asbury Park Convention Center instead with a crowd of 1500. Just after Woodstock, the band played The Carousel in Framingham, Massachusetts. You can read an account of what that was like in my novel Miles From Nowhere.

As we've reported, Led Zeppelin chose to skip Woodstock for their first American tour, playing the Asbury Park Convention Center instead with a crowd of 1500. Just after Woodstock, the band played The Carousel in Framingham, Massachusetts. You can read an account of what that was like in my novel Miles From Nowhere.

Late in '69 we'd just moved to a new apartment in North Hollywood. There was no furniture in the living room, bar the white Mediterranean style console stereo. My mother was putting up new curtains and my brother put on Zeppelin II. The acoustic effects (because of the empty room) were amazing, and the transfer of sound from one speaker to the other intensified my fascination. My mother yelled, "Turn that down." There may have been the insertion of an expletive. Nothing seals one's affinity for a rock LP like the criticism of a parent. Just eight years old at the time, I was sold.

Want to know what hard rock is? Led Zeppelin II (AM8), no bones about it. Zep II delivers in spades with bountiful and bludgeoning force, sex-hot passion, and intricate grace. "Whole Lotta Love" immediately seduces with Page's strutting chops, driving drums and Plant's mile-high wails before hurtling the listener into a sparse and shaky atmosphere of twitching percussion and mind-bending guitar squeals. And that's just the first track. Just try to sit still through "The Lemon Song," absorb the beautifully understated "Thank You" and don't forget the Bonham showcase "Moby Dick." This album exhibits a handful of the most influential songs in rock history with blues-soaked attitude to spare, indulgences in instrumentation that have yet to be surpassed, and compositions designed to rock your ass. Zep II is why the boys had their own private jet.

Want to know what hard rock is? Led Zeppelin II (AM8), no bones about it. Zep II delivers in spades with bountiful and bludgeoning force, sex-hot passion, and intricate grace. "Whole Lotta Love" immediately seduces with Page's strutting chops, driving drums and Plant's mile-high wails before hurtling the listener into a sparse and shaky atmosphere of twitching percussion and mind-bending guitar squeals. And that's just the first track. Just try to sit still through "The Lemon Song," absorb the beautifully understated "Thank You" and don't forget the Bonham showcase "Moby Dick." This album exhibits a handful of the most influential songs in rock history with blues-soaked attitude to spare, indulgences in instrumentation that have yet to be surpassed, and compositions designed to rock your ass. Zep II is why the boys had their own private jet.

Don't forget your copy of Miles available on Amazon. Click the link in the sidebar for the softbound and Kindle editions.

Led Zeppelin would end up opening for Vanilla Fudge with the band name mistakenly advertised as "Len Zeffelin." Doesn't quite have the same ring to it. No one had ever heard anything like it. By the time Zeppelin left the stage, psychedelia was dead and heavy metal was born. Poor Vanilla Fudge.

Within eight months of their official debut, Zeppelin was at the top of the bill at the Playhouse Theater in London, and the Pop Proms at the Royal Albert Hall. On October 17, 1969, a year after the band's inception, Zeppelin played Carnegie Hall, ending a ban on rock groups caused by the Rolling Stones' antics in 1965.

While playing in Denmark, Eva von Zeppelin, a relative of the designer of the airship, Ferdinand von Zeppelin, threatened to sue the band if they used the name for their gig in Copenhagen. For that one show, Led Zeppelin played under the alias, The Nobs.

While playing in Denmark, Eva von Zeppelin, a relative of the designer of the airship, Ferdinand von Zeppelin, threatened to sue the band if they used the name for their gig in Copenhagen. For that one show, Led Zeppelin played under the alias, The Nobs.The first LP took but 36 hours of studio time, including mixing and mastering and was fit into the band's hectic touring schedule. The band was without a label and on the clock to the tune of £1,782, or roughly $3,500. Released January 12, 1969, in the U.S., Led Zeppelin climbed to No. 10 in the U.S. and to No. 6 in the U.K. (Released March 28th). Until the late 60s, producers placed microphones directly in front of the amplifiers and drums. For Led Zeppelin, Page placed an additional microphone some distance from the amplifier (as far as twenty feet) and then recorded the balance between the two. By adopting this "distance equals depth" technique, Page was among the first producers to record a band's "ambient sound;" the distance of a note's time-lag from one end of the room to the other. Led Zeppelin was the first album to be released in stereo-only form; at the time, the practice of releasing both mono and stereo versions was the norm. The LP was the virtual Sgt. Pepper of Heavy Metal Blues.

Somehow, this band of misfits broke down the walls of critics (who abhorred the first LP) going straight for the audience, and won with their interpolation of blues, garage rock, soul, shuffle, psychedelic vibes and violin-bowed guitar fer chrissakes; they were over-the-top and minimalist, often in the same song. With tracks about hobbits, mythology and sex in equal form, Led Zeppelin made it look easy.

Somehow, this band of misfits broke down the walls of critics (who abhorred the first LP) going straight for the audience, and won with their interpolation of blues, garage rock, soul, shuffle, psychedelic vibes and violin-bowed guitar fer chrissakes; they were over-the-top and minimalist, often in the same song. With tracks about hobbits, mythology and sex in equal form, Led Zeppelin made it look easy.Led Zeppelin's debut album (AM8) is a monster of barely contained monolithic intensity (yeah pompous as shit). The album's artistic success hinges on the tension between the reflective/creative/experimental natures of Jimmy Page and John Paul Jones rubbing elbows with the bombastic/flamboyant/amped-up traditionalism of Robert Plant and John Bonham. When these tensions interact fireworks ensue. These are basic musical forms, blues, folk and bluegrass, taken to new extremes of sonic density and timbrel heaviness. Here was a conscious move to unearth the swamp blues from which all rock and roll originated and, at the same time, revitalize the format for a contemporary audience. The likes of The Yardbirds, The Small Faces, John Mayall's Bluesbreakers and Joe Cocker fronted a movement that occasionally bruised the singles chart, but was primarily an underground faction. Hendrix, Beck and Cream pushed this to another, darker dimension and Zeppelin's debut was an integral player in the cadre that opened the floodgates to a bevy of progressive bands whose growing obsession with self-indulgent, sprawling epics lead to an inevitable implosion and the backlash that was punk. That's a lot of rock history in one breath: Led Zeppelin was the catalyst for it all. By year's end, the band released Led Zeppelin II (Led Zeppelin II, quickly moved up to No. 1 in both the U.S. and the U.K., remaining on the charts for 98 weeks in the States and an astounding 138 weeks in Britain.)

As we've reported, Led Zeppelin chose to skip Woodstock for their first American tour, playing the Asbury Park Convention Center instead with a crowd of 1500. Just after Woodstock, the band played The Carousel in Framingham, Massachusetts. You can read an account of what that was like in my novel Miles From Nowhere.

As we've reported, Led Zeppelin chose to skip Woodstock for their first American tour, playing the Asbury Park Convention Center instead with a crowd of 1500. Just after Woodstock, the band played The Carousel in Framingham, Massachusetts. You can read an account of what that was like in my novel Miles From Nowhere. Late in '69 we'd just moved to a new apartment in North Hollywood. There was no furniture in the living room, bar the white Mediterranean style console stereo. My mother was putting up new curtains and my brother put on Zeppelin II. The acoustic effects (because of the empty room) were amazing, and the transfer of sound from one speaker to the other intensified my fascination. My mother yelled, "Turn that down." There may have been the insertion of an expletive. Nothing seals one's affinity for a rock LP like the criticism of a parent. Just eight years old at the time, I was sold.

Want to know what hard rock is? Led Zeppelin II (AM8), no bones about it. Zep II delivers in spades with bountiful and bludgeoning force, sex-hot passion, and intricate grace. "Whole Lotta Love" immediately seduces with Page's strutting chops, driving drums and Plant's mile-high wails before hurtling the listener into a sparse and shaky atmosphere of twitching percussion and mind-bending guitar squeals. And that's just the first track. Just try to sit still through "The Lemon Song," absorb the beautifully understated "Thank You" and don't forget the Bonham showcase "Moby Dick." This album exhibits a handful of the most influential songs in rock history with blues-soaked attitude to spare, indulgences in instrumentation that have yet to be surpassed, and compositions designed to rock your ass. Zep II is why the boys had their own private jet.

Want to know what hard rock is? Led Zeppelin II (AM8), no bones about it. Zep II delivers in spades with bountiful and bludgeoning force, sex-hot passion, and intricate grace. "Whole Lotta Love" immediately seduces with Page's strutting chops, driving drums and Plant's mile-high wails before hurtling the listener into a sparse and shaky atmosphere of twitching percussion and mind-bending guitar squeals. And that's just the first track. Just try to sit still through "The Lemon Song," absorb the beautifully understated "Thank You" and don't forget the Bonham showcase "Moby Dick." This album exhibits a handful of the most influential songs in rock history with blues-soaked attitude to spare, indulgences in instrumentation that have yet to be surpassed, and compositions designed to rock your ass. Zep II is why the boys had their own private jet.Don't forget your copy of Miles available on Amazon. Click the link in the sidebar for the softbound and Kindle editions.

Published on October 27, 2019 12:40

October 23, 2019

The California Sound - Taking a Stand

I object to the absurd categorization of anything, with, of course, the genre names attached to music the heart of this tirade. I've long hated the term "Classic Rock." Rather than simply categorizing the music produced from 1966 to 1975, the term places a stigma that suggests that this is "your parents' music" rather than its timelessness. It's interesting that for young people there is this idea of "parents' music" until there’s an artist they embrace, someone like Neil Young, Pink Floyd or Led Zeppelin. The reality is, popular music today, along the lines of Taylor Swift and her mediocre disciples, suggest instead that young people are already listening to parents' music, and they're not parents yet. I am ashamed of 16 and 17-year-old boys whose favorite artist is Taylor Swift; the musical equivalent of a guy having The Notebook as his favorite movie (yeah, yeah, I know I’ll hear about that one).

I object to the absurd categorization of anything, with, of course, the genre names attached to music the heart of this tirade. I've long hated the term "Classic Rock." Rather than simply categorizing the music produced from 1966 to 1975, the term places a stigma that suggests that this is "your parents' music" rather than its timelessness. It's interesting that for young people there is this idea of "parents' music" until there’s an artist they embrace, someone like Neil Young, Pink Floyd or Led Zeppelin. The reality is, popular music today, along the lines of Taylor Swift and her mediocre disciples, suggest instead that young people are already listening to parents' music, and they're not parents yet. I am ashamed of 16 and 17-year-old boys whose favorite artist is Taylor Swift; the musical equivalent of a guy having The Notebook as his favorite movie (yeah, yeah, I know I’ll hear about that one). Of the genre-specific terms, my least favorite is "Yacht Rock." The moniker is pretentious, inaccurate, and derogatory and it makes far more sense, if categorization is a necessity, to refer to the musical type as The California Sound, which in itself is a misnomer but at least suggests an accurate musical category. The term Yacht Rock intimates the type of music that the yuppie-set of the 70s listened to, supposedly on their yachts, essentially inspired by the Beach Boys' "Sloop John B." or the most famous Yacht Rock song of all, "Sailing" by Christopher Cross.

The California Sound was a direct result of FM picking up where AM left off, essentially FM's top 40. The Wrecking Crew, those studio musicians in L.A. who are responsible for the incredible musicianship of those 60s AM Hits found their talents less necessary as AOR (Album Oriented Rock) took over the FM airwaves, and started creating their own bands, like Toto, or working on a full-time basis with the artists of the day. The California Sound represented those musicians who still work primarily in the studio or were borrowed from bands of other genres. The perfect example being Steely Dan.

Steely Dan, with the exception of its first three LPs, Can't Buy a Thrill, Countdown to Ecstacy and Pretzel Logic, wasn't really a band but an ideology, a coming together of musical artists, not unlike The Alan Parsons Project with a jazz sensibility. Here the term Yacht Rock is at its most offensive. Like Alan Parsons, Donald Fagen and Walter Becker recruited members for the band and into the studio. Bringing along with them, more often than not, jazz fusion musicians like Wayne Shorter, Larry Carlton, and Jaco Pastorius. The high production values certainly fit that Yacht Rock mold, but the terminology cheapens what could be described as the most sophisticated music of the 70s.

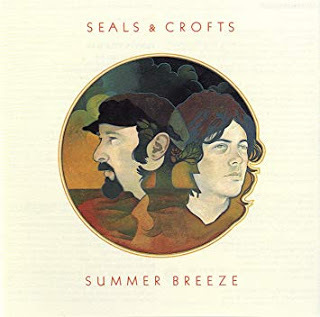

Steely Dan, with the exception of its first three LPs, Can't Buy a Thrill, Countdown to Ecstacy and Pretzel Logic, wasn't really a band but an ideology, a coming together of musical artists, not unlike The Alan Parsons Project with a jazz sensibility. Here the term Yacht Rock is at its most offensive. Like Alan Parsons, Donald Fagen and Walter Becker recruited members for the band and into the studio. Bringing along with them, more often than not, jazz fusion musicians like Wayne Shorter, Larry Carlton, and Jaco Pastorius. The high production values certainly fit that Yacht Rock mold, but the terminology cheapens what could be described as the most sophisticated music of the 70s. My point is to put an end to foolhardy categorization. Should we need to put everything into neat little cubbies, The California Sound is far more broadly appropriate term without the derogatory implication. The California sound held a distinctly popular sound, a recognizable musical motif that fit into that FM top 40 mold. And while it encompasses, on a popular level, artists like Ambrosia, Boz Scaggs, Kenny Loggins, Gerry Rafferty, Andrew Gold, Seals and Crofts and the Little River Band. As an extension of The Wrecking Crew ideology, many musicians, particularly jazz musicians, ventured out of the commercial realm to work with artists like Steely Dan, Tom Waits, Rickie Lee Jones, Jackson Browne, and Joni Mitchell. Not one pejorative thing can be said about any of those artists; enough with the corny monikers.

Published on October 23, 2019 11:45

Repost: The Wrecking Crew

By the late 60's, the rock auteur, an often overlooked evolution in popular music, changed the face of music forever. Sinatra, the sole surviving American Standard Vocalist, ushered out the era of the songwriter as The Beatles and The Beach Boys took the reigns. Sinatra, of course, was a song stylist, and we indeed have those today, but the genre change led directly to rock's golden era, that decade from 1966 to 1976 (give or take a year). Nonetheless, the early 60s provided a wealth of songwriters, from Boyce and Hart to Carole King, whose contributions set the pace throughout the 60s. While AOR (Album Oriented Rock) was rearing its head, AM radio continued nonplussed on a journey that began with Your Hit Parade in 1935. The Monkees, Sonny and Cher and The Carpenters bombarded the airwaves with compositions written by someone else. It was the last era when songwriter was a viable occupation. The casual listener has never heard of Jimmy Webb, Tom Hardin or John Bettis, but has undeniably heard their songs (indeed, Hardin was a featured act at Woodstock). The anonymity of the 60s songwriter is on a par with the anonymity of the session musician.

When it comes to The Monkees, there was no Milli-Vanilli pretense, the pop-lite version of the Fab Four indeed sang their plethora of hits, a wealth of recognizable pop surpassed by few - from "I'm a Believer" to their "Day in a Life" moment, "Pleasant Valley Sunday" - yet it wasn't until Headquarters that the four elevated themselves from crooners to musicians; a common thread that was shared with radio's top hits throughout the golden years of pop/rock and countdown radio.

When it comes to The Monkees, there was no Milli-Vanilli pretense, the pop-lite version of the Fab Four indeed sang their plethora of hits, a wealth of recognizable pop surpassed by few - from "I'm a Believer" to their "Day in a Life" moment, "Pleasant Valley Sunday" - yet it wasn't until Headquarters that the four elevated themselves from crooners to musicians; a common thread that was shared with radio's top hits throughout the golden years of pop/rock and countdown radio.

More often than not, the songs on the radio, the great riffs and licks that are indelibly etched in our minds, were the work of musicians of the highest caliber: The Wrecking Crew. From the unmistakable bass of Carol Kaye on "The Beat Goes On" to the infectious guitar theme from Bonanza (Tommy Tedesco), The Wrecking Crew was the most recognizable band you never knew.

Many of us may find a surge of disappointment to learn that the great radio hits of the 60s weren't performed by the artists we admire. We don’t really care who played bass for Sonny and Cher, but cringe that there wasn't an intrinsic Sonny and Cher "band," or that it's not The Beach Boys (with the exception of Brian) who created the signature instrumental sound found in "Wouldn't It Be Nice" or "Good Vibrations." Oh well, get over it. Instead, we should celebrate the genius that was initially and unofficially called "The First Call Gang" in the 1950s, of guitarist/bassist Ray Pohlman (Pohlman additionally was the musician who popularized the electric bass). Pohlman & Co. (Earl Palmer, Glen Campbell, Barney Kessel, etc.) played with artists as diverse as Merle Haggard, Leonard Cohen and Pat Boone.

Many of us may find a surge of disappointment to learn that the great radio hits of the 60s weren't performed by the artists we admire. We don’t really care who played bass for Sonny and Cher, but cringe that there wasn't an intrinsic Sonny and Cher "band," or that it's not The Beach Boys (with the exception of Brian) who created the signature instrumental sound found in "Wouldn't It Be Nice" or "Good Vibrations." Oh well, get over it. Instead, we should celebrate the genius that was initially and unofficially called "The First Call Gang" in the 1950s, of guitarist/bassist Ray Pohlman (Pohlman additionally was the musician who popularized the electric bass). Pohlman & Co. (Earl Palmer, Glen Campbell, Barney Kessel, etc.) played with artists as diverse as Merle Haggard, Leonard Cohen and Pat Boone.

In 1962, Phil Spector would recruit Pohlman, along with studio regulars like Hal Blaine (Drums) and Tommy Tedesco (guitar), as the progenitors of The Wall of Sound, Spector’s trademark vibe on hits like "Be My Baby," "Then He Kissed Me" and "You've Lost That Lovin' Feeling." During this period, Spector referred to the band as The Wall of Sound Orchestra.

In 1962, Phil Spector would recruit Pohlman, along with studio regulars like Hal Blaine (Drums) and Tommy Tedesco (guitar), as the progenitors of The Wall of Sound, Spector’s trademark vibe on hits like "Be My Baby," "Then He Kissed Me" and "You've Lost That Lovin' Feeling." During this period, Spector referred to the band as The Wall of Sound Orchestra.

In the mid-60s, the newly monikered Wrecking Crew represented a plurality of AM's hits. The impact is best realized with a list, an exhaustive one: "California Dreamin'" "Monday Monday," "Windy," "California Girls," "Mr. Tambourine Man," "Dead Man’s Curve," "Aquarius," "Strangers in the Night," "These Boots Were Made for Walkin'" "I Got You, Babe," "MacArthur Park," "This Diamond Ring," "Eve of Destruction," "Bridge Over Troubled Water," "Cracklin' Rosie" and "Classical Gas" – these hardly scratch the surface.

Aside from those already mentioned, add on Leon Russell, Joe Osborne, Plas Johnson, Max Bennett and Don Randi, but that's not half the musicians who offered their talents. The Wrecking Crew was the ultimate rock orchestra.

When it comes to The Monkees, there was no Milli-Vanilli pretense, the pop-lite version of the Fab Four indeed sang their plethora of hits, a wealth of recognizable pop surpassed by few - from "I'm a Believer" to their "Day in a Life" moment, "Pleasant Valley Sunday" - yet it wasn't until Headquarters that the four elevated themselves from crooners to musicians; a common thread that was shared with radio's top hits throughout the golden years of pop/rock and countdown radio.

When it comes to The Monkees, there was no Milli-Vanilli pretense, the pop-lite version of the Fab Four indeed sang their plethora of hits, a wealth of recognizable pop surpassed by few - from "I'm a Believer" to their "Day in a Life" moment, "Pleasant Valley Sunday" - yet it wasn't until Headquarters that the four elevated themselves from crooners to musicians; a common thread that was shared with radio's top hits throughout the golden years of pop/rock and countdown radio.More often than not, the songs on the radio, the great riffs and licks that are indelibly etched in our minds, were the work of musicians of the highest caliber: The Wrecking Crew. From the unmistakable bass of Carol Kaye on "The Beat Goes On" to the infectious guitar theme from Bonanza (Tommy Tedesco), The Wrecking Crew was the most recognizable band you never knew.

Many of us may find a surge of disappointment to learn that the great radio hits of the 60s weren't performed by the artists we admire. We don’t really care who played bass for Sonny and Cher, but cringe that there wasn't an intrinsic Sonny and Cher "band," or that it's not The Beach Boys (with the exception of Brian) who created the signature instrumental sound found in "Wouldn't It Be Nice" or "Good Vibrations." Oh well, get over it. Instead, we should celebrate the genius that was initially and unofficially called "The First Call Gang" in the 1950s, of guitarist/bassist Ray Pohlman (Pohlman additionally was the musician who popularized the electric bass). Pohlman & Co. (Earl Palmer, Glen Campbell, Barney Kessel, etc.) played with artists as diverse as Merle Haggard, Leonard Cohen and Pat Boone.

Many of us may find a surge of disappointment to learn that the great radio hits of the 60s weren't performed by the artists we admire. We don’t really care who played bass for Sonny and Cher, but cringe that there wasn't an intrinsic Sonny and Cher "band," or that it's not The Beach Boys (with the exception of Brian) who created the signature instrumental sound found in "Wouldn't It Be Nice" or "Good Vibrations." Oh well, get over it. Instead, we should celebrate the genius that was initially and unofficially called "The First Call Gang" in the 1950s, of guitarist/bassist Ray Pohlman (Pohlman additionally was the musician who popularized the electric bass). Pohlman & Co. (Earl Palmer, Glen Campbell, Barney Kessel, etc.) played with artists as diverse as Merle Haggard, Leonard Cohen and Pat Boone.  In 1962, Phil Spector would recruit Pohlman, along with studio regulars like Hal Blaine (Drums) and Tommy Tedesco (guitar), as the progenitors of The Wall of Sound, Spector’s trademark vibe on hits like "Be My Baby," "Then He Kissed Me" and "You've Lost That Lovin' Feeling." During this period, Spector referred to the band as The Wall of Sound Orchestra.

In 1962, Phil Spector would recruit Pohlman, along with studio regulars like Hal Blaine (Drums) and Tommy Tedesco (guitar), as the progenitors of The Wall of Sound, Spector’s trademark vibe on hits like "Be My Baby," "Then He Kissed Me" and "You've Lost That Lovin' Feeling." During this period, Spector referred to the band as The Wall of Sound Orchestra.In the mid-60s, the newly monikered Wrecking Crew represented a plurality of AM's hits. The impact is best realized with a list, an exhaustive one: "California Dreamin'" "Monday Monday," "Windy," "California Girls," "Mr. Tambourine Man," "Dead Man’s Curve," "Aquarius," "Strangers in the Night," "These Boots Were Made for Walkin'" "I Got You, Babe," "MacArthur Park," "This Diamond Ring," "Eve of Destruction," "Bridge Over Troubled Water," "Cracklin' Rosie" and "Classical Gas" – these hardly scratch the surface.

Aside from those already mentioned, add on Leon Russell, Joe Osborne, Plas Johnson, Max Bennett and Don Randi, but that's not half the musicians who offered their talents. The Wrecking Crew was the ultimate rock orchestra.

Published on October 23, 2019 10:01

October 22, 2019

Grow Old With Me

There are artists like William Butler Yeats, the great Irish poet, who painstakingly made his work look easy when in reality he would suffer over each word. Everything published was a masterpiece, everything else left alone, hidden away. Woody Allen, conversely, directed films like Annie Hall, Manhattan and Paris After Midnight that are darn near perfect for their genre, yet as quintessential as these films are, others, too many to mention, are simply awful, mediocre at best. It's simply a different philosophical approach to artistry.

Such was the case with Lennon. Lennon would, like Yeats, make something seem easy, flawless, and he'd hide everything else away. Yoko, instead, and I am not passing Yoko-judgment here, has subsequently released everything John ever wrote. I suppose there are some shopping lists in there, as well.

Not everything should have been released, and yet, if we don't treat what was like canon and only as a tidbit of history, I'm okay. Nothing was taken away from Pet Sounds when Capitol, 40 years later, released the alternate takes and snippets, the edited sequences and the things that didn't work.

The Beatles Anthology was an exhaustive work and documentary that bears it all. Though critics were cautious at best, when "Free As a Bird" and "Real Love" were released in 1995 and 1996, at least for a day or so, I was an emotional wreck. (Understand that I cried when the new Star Wars trailer came out.)

Nonetheless, there was a new single for Anthology 1, another for Anthology 2, but none for Anthology 3. No single was ever release although Yoko had released two other songs for the project.

On his latest LP, What's My Name, Ringo has released the Lennon track, "Grow Old With Me," with Paul McCartney on bass and backing vocals. The video here is a mash-up of a 1980 Lennon demo recorded in Bermuda with the track released on Ringo's new LP. It's not Beatles, it's certainly not of the quality of "Free As a Bird" or "Real Love," but it is the closest thing left of anything even remotely Beatles, even if it is a forgery. Treat it as such, but close your eyes - there is some Beatles in there.

Published on October 22, 2019 20:41

October 20, 2019

The Wrecking Crew is not a band…

Based on a popular documentary from 2008, many are under the impression that The Wrecking Crew was, indeed, a band. Instead, The Wrecking Crew was a nickname for 15 to 35 California-based studio musicians who worked with artists from the early 1960s until 1974, particularly Sonny and Cher ("The Beat Goes On"), The Mamas and the Papas ("California Dreamin'") and The Beach Boys. "Wouldn't It Be Nice" is a shining moment in rock history; the instrumentation for the Pet Sounds opening track one of popular music's finest achievements.

Based on a popular documentary from 2008, many are under the impression that The Wrecking Crew was, indeed, a band. Instead, The Wrecking Crew was a nickname for 15 to 35 California-based studio musicians who worked with artists from the early 1960s until 1974, particularly Sonny and Cher ("The Beat Goes On"), The Mamas and the Papas ("California Dreamin'") and The Beach Boys. "Wouldn't It Be Nice" is a shining moment in rock history; the instrumentation for the Pet Sounds opening track one of popular music's finest achievements.Incredible musicians like Max Bennett who worked alongside Frank Zappa as the bassist for the Hot Rats project, Carol Kaye, whose bassline for "The Beat Goes On" remains the most famous bass riff of all time, Glen Campbell (Guitar) and Leon Russell (Keyboards) convened in an everchanging array of the world’s most talented musicians. It was The Wrecking Crew's talent and expertise that led to the rise of the classic rock 'n' roll era of the 70s, and ironically also brought about their own demise.

The collective Wrecking Crew went uncredited for most of their history. When critics, for example, contemplate the top bassists or drummers of the rock era, the names often and deservedly listed are Chris Squire (bass, Yes), John Entwistle (bass, The Who), Jack Bruce (bass, Cream), Bill Bruford (Drums, Yes; King Crimson), John Bonham (Drums, Led Zeppelin), but the likes of Carol Kaye and Hal Blaine remain anonymous. It’s a scenario in the industry leftover from the era of the American Standard and singers like Frank Sinatra, Sammy Davis Junior and Doris Day. During the 1940s, the Big Band Era, band leaders like Glen Miller, Harry James and Tommy Dorsey had singers as members of the band. As the era faded, those singers would then tour and record with talented though unknown musicians. By the late 1950s, many of these musicians settled in L.A., working the studio circuit. The Wrecking Crew (minus the name) was born.

The collective Wrecking Crew went uncredited for most of their history. When critics, for example, contemplate the top bassists or drummers of the rock era, the names often and deservedly listed are Chris Squire (bass, Yes), John Entwistle (bass, The Who), Jack Bruce (bass, Cream), Bill Bruford (Drums, Yes; King Crimson), John Bonham (Drums, Led Zeppelin), but the likes of Carol Kaye and Hal Blaine remain anonymous. It’s a scenario in the industry leftover from the era of the American Standard and singers like Frank Sinatra, Sammy Davis Junior and Doris Day. During the 1940s, the Big Band Era, band leaders like Glen Miller, Harry James and Tommy Dorsey had singers as members of the band. As the era faded, those singers would then tour and record with talented though unknown musicians. By the late 1950s, many of these musicians settled in L.A., working the studio circuit. The Wrecking Crew (minus the name) was born.With artists like Sonny and Cher, Petula Clark and The 5th Dimension there was no presumption of these singers playing their own instruments. Studios would hire musicians on a per diem basis and a track like “The Beat Goes On” would be recorded in a matter of hours. That time frame was important in the industry; studio time was expensive and record labels demanded quality in no time at all. The Beach Boys were indeed capable of playing their own instruments, but they were young and inexperienced, and even back in 1961 when he was 19 years old, Brian Wilson was a perfectionist. To save on studio time, in came The Crew. That incredible guitar on "Surfin' USA" was all the work of Carl Wilson (you thought I was going to say The Wrecking Crew), but in the name of expediency, The Crew was called in to "double track" the production to get it done. Here, as was often the case, The Crew went uncredited and anonymous without so much as a receipt or a paper trail of their contribution.

Brian Wilson's expertise as a producer brought Carol Kaye into his purview in 1965 and subsequently led to his using The Crew exclusively on the Pet Sounds sessions, not even including any of the other Beach Boys in the initial production of the LP. The instrumental track for “Wouldn’t It Be Nice” was laid down with the other band members out on tour, unaware that Brian was busily at work on his masterpiece. As the story goes, when the other Beach Boys returned from touring, it was with the intent of returning to the studio and returning to the patented Beach Boys surfin’ sound which Brian had outgrown. When the band, led by singer/songwriter Mike Love, threatened to revolt (to either quit the band or fire Brian), founding member and multi-instrumentalist Al Jardine played the instrumental track for "Wouldn’t It Be Nice" and asked "Are you sure you don’t want to be a part of that?"

Brian Wilson's expertise as a producer brought Carol Kaye into his purview in 1965 and subsequently led to his using The Crew exclusively on the Pet Sounds sessions, not even including any of the other Beach Boys in the initial production of the LP. The instrumental track for “Wouldn’t It Be Nice” was laid down with the other band members out on tour, unaware that Brian was busily at work on his masterpiece. As the story goes, when the other Beach Boys returned from touring, it was with the intent of returning to the studio and returning to the patented Beach Boys surfin’ sound which Brian had outgrown. When the band, led by singer/songwriter Mike Love, threatened to revolt (to either quit the band or fire Brian), founding member and multi-instrumentalist Al Jardine played the instrumental track for "Wouldn’t It Be Nice" and asked "Are you sure you don’t want to be a part of that?"This vignette proves a point: the proficiency of musicians like Jardine, who played a myriad of stringed instruments including the stand-up bass on early Beach Boys tracks, was trumped by the talent and expertise of The Wrecking Crew. Roger McGuinn of The Byrds said The Crew and he "knocked out two tracks in one three-hour session. When the rest of the band got to play, it took us 77 takes to get 'Turn! Turn! Turn!'"

The Wrecking Crew can be heard on hits like Johnny Rivers' "The Poor Side of Town," "You're my Soul and Inspiration" from The Righteous Brothers, Nancy Sinatra's "These Boots Are Made For Walkin'," Simon and Garfunkel's "Mrs. Robinson," and hundreds of others. I'll go out on a limb and say that The Wrecking Crew, despite their anonymity and lack of any record-keeping, has record sales in the hundreds of millions. The Beatles have 27 No. 1 selling singles, and while that record is unapproachable, if The Wrecking Crew Really was a band, they would have more than 100 No. 1s! As an example, Drummer Hal Blaine played on 40 U.S. No. 1s and over 150 songs that entered the Top 10.

It's interesting to note that The Crew's incredible musicianship ushered in its own demise. In 1967, The Crew recorded, under Jimmy Webb's direction, the Richard Harris smash hit "MacArthur Park." That single, originally written for The Association, broke the mold in the record industry establishing the model for songs over three minutes and clocking in at 7:21. The dominoes continued to fall with singles like "Hey Jude" at over six minutes and 1971's "Stairway to Heaven" at 8:02. Lengthier songs on the radio meant the number of tracks played per hour was diminished providing less work for studio musicians. "MacArthur Park" had opened the doors for bands like Genesis and Pink Floyd to create songs that exceeded ten minutes and often covered an album side. That freedom, the experimentation, and the artistry of bands rising in the early 70s would end The Crew's dominance and 1974's "Love Will Keep Us Together," by The Captain and Tennille, the biggest selling single of the year, would be their last No. 1.

And yet…

Stay tuned to AM for "The California Sound."

Published on October 20, 2019 06:54

October 18, 2019

The Synthesizer in Pop Music

My first experience with the Moog Synthesizer was in 1968 with Walter Carlos's Switched-On Bach, still the biggest selling classical LP of all time. It's an intensely complex production that includes an incredible performance of the Brandenburg Concertos, Bach compositions written between 1711 and 1721. Now keep in mind that when the Moog was utilized on this recording, it was so primitive that only one note could be played on the keyboard at a time; something as simple as a C chord could not be "played," it had to be manipulated by playing and recording one note, a C, then playing and recording the next note, E, without erasing the original C, then adding atop them both the G note that completes the chord. With thousands of notes layered one upon the next, one can imagine the time and effort put into Carlos's production.

Now maybe I should back-track a bit. The synthesizer developed by Moog was a complex electronic device that created sounds that essentially had never before been heard by the human ear, synthesized sound – manufactured sounds. The synthesizer was programmed by the musician utilizing an electronic keyboard with each note creating a different sound in a musical progression. Pianos, for instance, utilize mechanical means to create sound; in this case, a felt-covered hammer striking a metal string. But there is nothing mechanical about synthetic sound, it is purely the result of electronics. Some will point back to the Moody Blues in 1966 or King Crimson in 1968 and the use of the mellotron as the first synthesized sounds on record, but mellotrons were actually keyboard-driven tape loops. You would record on tape the sound of a single note played by a physical instrument like the French Horn and then loop that tape through the mellotron. Strike a corresponding key on the keyboard and you hear the tape loop of the horn. It’s simply not synthesized sound.

Now, aside from Switched-On Bach, I thought my first exposure to the synthesizer was on the Beatles' Abbey Road in 1969 in songs like "Because" and the Abbey Road Medley. George Harrison had exposed the other Beatles to its sound and said, "I first heard about the Moog synthesizer in America. I had to have mine made specially, Mr Moog had only just invented it. It was enormous, with hundreds of jackplugs and 2 keyboards." But it was two years earlier when Robert Moog, who invented the synthesizer in the mid-sixties, marketed the complex machine at the Monterey Pop Festival in 1967 and caught the ears of both Simon and Garfunkel and the Byrds. The Moog is subsequently heard on Simon and Garfunkel's Bookends in 1968 and on The Notorious Byrd Brothers, which was recorded in late 1967. So, we've moved back a few years, but we're not done.

Brian Wilson had utilized a different type of synthesized sound in 1966 in the recording of Good Vibrations, the Theremin, invented in 1928 by Leon Theremin. It's an electronically manipulated device on which the thereminist essentially waves his hands over the instrument creating scales, physically touching nothing. Because of the sliding scales, the Theremin has an eerie sound that was utilized in films like Hitchcock’s Spellbound and in sci-fi classics like Bernard Herrmann's The Day the Earth Stood Still. The penultimate use in rock music though goes back beyond the Beach Boys to 1965 and an early psychedelic band called Lothar and the Hand People. But we're not done.

In 1962, The Tornados' smash hit "Telstar" utilized a synthesizer called the Clavioline invented in France in 1948. With that info, 1962 was my go-to date for the synthesizer; that is until I watched Stanley Kubrick's Dr. Strangelove the other day. I hadn't seen it in years. In the end, after the hilarious scene with Slim Pickins, the greatest stage name ever, Vera Lynn's British hit from 1938, "We'll Meet Again," plays over the video footage of nuclear mushroom clouds. There's a strange instrument in the background that sounded to me like a synthesizer. Indeed, after doing my research, I discovered that the instrument is called a Novachord, invented by Hammond Organ in the mid-1930s. It is actually the first polyphonic synthesizer, meaning it could play more than one note at a time, something the early Moog Synthesizer could not do.

In 1962, The Tornados' smash hit "Telstar" utilized a synthesizer called the Clavioline invented in France in 1948. With that info, 1962 was my go-to date for the synthesizer; that is until I watched Stanley Kubrick's Dr. Strangelove the other day. I hadn't seen it in years. In the end, after the hilarious scene with Slim Pickins, the greatest stage name ever, Vera Lynn's British hit from 1938, "We'll Meet Again," plays over the video footage of nuclear mushroom clouds. There's a strange instrument in the background that sounded to me like a synthesizer. Indeed, after doing my research, I discovered that the instrument is called a Novachord, invented by Hammond Organ in the mid-1930s. It is actually the first polyphonic synthesizer, meaning it could play more than one note at a time, something the early Moog Synthesizer could not do. And there you have it: the first use of a synthesizer in pop music, not the Beatles, not Simon and Garfunkel, The Moody Blues, or the Tornados, but Vera Lynn in 1938 with "We'll Meet Again."

Published on October 18, 2019 05:12