R.J. Stowell's Blog: rjsomeone, page 33

December 19, 2019

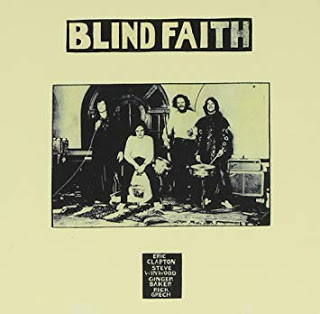

Blind Faith

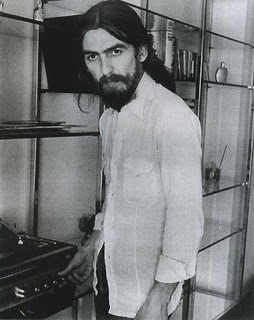

Rock musicians are kind of like a high school clique. This one's friends with that one and then, not so much. That one moves on, hooks up with this one, then the ex comes along… That really was the case in the late 60s with the first rock supergroups, among them, Blind Faith. Okay, so Cream broke up in 1968 and Traffic was on a bit of a hiatus. Eric Clapton and Steve Winwood were milling about; Clapton had played with the Beatles and John Lennon even suggested that Eric join the band on a tense day in which George Harrison essentially quit the Beatles. While still with Traffic, Jimi Hendrix asked Winwood to play organ on "Voodoo Chile."

Rock musicians are kind of like a high school clique. This one's friends with that one and then, not so much. That one moves on, hooks up with this one, then the ex comes along… That really was the case in the late 60s with the first rock supergroups, among them, Blind Faith. Okay, so Cream broke up in 1968 and Traffic was on a bit of a hiatus. Eric Clapton and Steve Winwood were milling about; Clapton had played with the Beatles and John Lennon even suggested that Eric join the band on a tense day in which George Harrison essentially quit the Beatles. While still with Traffic, Jimi Hendrix asked Winwood to play organ on "Voodoo Chile." In early 1969, Ginger Baker joined up with former bandmate, Clapton, and Winwood at Traffic's studio in Berkshire. As the sessions progressed, they, in turn, were joined by Traffic bandmates, Jim Capaldi and Chris Wood. Rumor is, going forward, Clapton would have preferred working with Capaldi than Baker, but the point was moot, neither Capaldi nor Wood was interested in leaving Traffic, though Traffic would break up shortly thereafter. Wait – where's my scorecard? – The group, now consisting of Clapton, Winwood, and Baker was announced as a thing in February 1969 with the trio adding Ric Grech on bass, but still not having a name.

The American IssueThat would come with the controversial photograph that graced the album cover, a nude photograph of a young girl holding the hood ornament of a 1957 Belair. Keep in mind that the only albums up to that point that didn't have the band's name and the title of the LP on the cover had been King Crimson's In the Court of the Crimson King, Abbey Road, Music from the Big Pink and The Velvet Underground and Nico.

The American IssueThat would come with the controversial photograph that graced the album cover, a nude photograph of a young girl holding the hood ornament of a 1957 Belair. Keep in mind that the only albums up to that point that didn't have the band's name and the title of the LP on the cover had been King Crimson's In the Court of the Crimson King, Abbey Road, Music from the Big Pink and The Velvet Underground and Nico.Photographer, Bob Seidermann, had in his mind what he wanted to capture. In many an article, he has tried to explain the concept, but it seems to be something that was just there in his mind and he could only express it visually. Despite the nudity of the cover, Seiderman was hoping to express innocence in the form of a girl as young as Shakespeare's Juliet, in this case, an 11-year-old. The photograph was of Mariora Goschen who was paid £40. Seidermann was given consent for the photograph by Goschen’s parents. He ultimately called the photograph "Blind Faith," which of course would become the band's name.

Blind Faith's most famous track, "Can't Find My Way Home" was written by Winwood and is one of those tracks that nearly everybody knows, but no one knows who it’s by, despite Winwood's unmistakable vocal. Without much rehearsal time behind them, Blind Faith would play a free concert on June 7, 1969, at London’s Hyde Park. It would be the biggest concert ever held up to that point with upwards of one hundred thousand in attendance, a record that would, of course, be shattered by Woodstock's half a million strong less than two months later. And keep in mind that in 1969, Winwood was 21, Clapton 24, Grech 22 and Ginger Baker the old man at 27.

Blind Faith would only produce one LP. Clapton would go on to Delaney and Bonnie, Derek and the Dominoes and his solo career, Winwood would return for Traffic's best jams, while Baker formed another supergroup, Ginger Baker's Air Force with Grech, Denny Laine from The Moody Blues, who would go on to work with McCartney and Wings, and Alan White who would move on to Yes.

Did you get all that?

Published on December 19, 2019 03:51

December 18, 2019

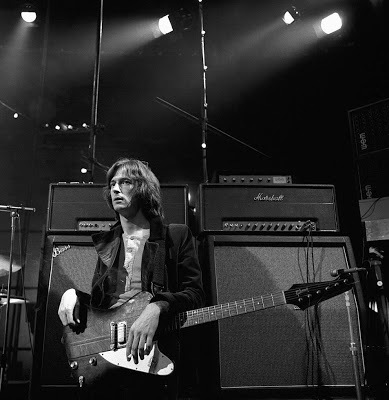

Clapton is God

Eric Clapton is one of the great rock guitarists. One of those artists who are so totally dedicated to his craft that in a career that now spends 55 years, he’s never lost his dedication to learning and growing.

Eric Clapton is one of the great rock guitarists. One of those artists who are so totally dedicated to his craft that in a career that now spends 55 years, he’s never lost his dedication to learning and growing.Clapton has the nicknamed Slowhand, and many are under the misconception that, while Clapton is undoubtedly one of the greats in the history of rock music, he plays slowly and methodically. That is not the basis for the nickname. Instead, Clapton, when with the Yardbirds, who he joined in 1963 alongside Jimmy Page and Jeff Beck, would make the audience wait should a guitar string break during a show. The audience would start to do a slow handclap making Eric’s restringing of his guitar a part of the show; hence “Slowhand.”

Then there’s the “Clapton is God” thing which inspired the famous photograph of a dog doing his business on the wall where the epithet was painted. Clapton hated that. He said he never thought of himself as the greatest guitar player in the world. He only wanted to be the greatest guitar player in the world.

From the Yardbirds, Clapton moved on to John Mayall and the Bluesbreakers and then of course to Cream with Ginger Baker and Jack Bruce, whose 1967 album Disraeli Gears is one of my top 10 rock albums.

After Cream, another supergroup was formed with Clapton, Ginger Baker, Steve Winwood of Traffic and Rick Grech from Family. That band was called Blind Faith who debuted the act before 100,000 people in London’s Hyde Park in June 1969 with the megahit “Can’t Find My Way Home.”

But Clapton was the consummate artist and didn’t like being in the spotlight. In the summer of 1969, he toured with Delaney and Bonnie and Friends. Delaney and Bonnie were like Ringo Starr today, who’s All-star Band is ever-changing; everyone wanting to play with Ringo. Clapton was content to play his guitar quietly, so to speak, off to the side.

But that wasn’t all. He was in the Plastic Ono Band and, of course, played guitar on George Harrison’s “While My Guitar Gently Weeps." Clapton and the Delaney and Bonnie Band were also the session musicians for Harrison‘s All Things Must Pass. This was a busy guy.

50 years ago, the anonymity afforded him with Delaney and Bonnie led to Clapton's new project with Bonnie Bramlett as his Muse, Derek and the Dominos, and the LP with Clapton‘s most famous song “Layla,” one of the greatest singles ever released.

Published on December 18, 2019 05:04

December 16, 2019

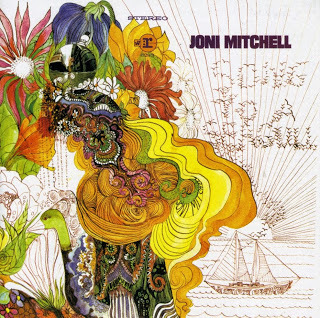

Ladies of the Canyon - The Joni 70s

1970's Ladies of the Canyon was written and recorded at the height of Joni Mitchell's early phase while living in Laurel Canyon, and is a grand debut for the Joni of the 70s. It was here, on Ladies, that Joni started her venture into jazz. The album was produced by Joni, who also played piano, guitar and keyboards with a handful of jazz musicians, including Paul Horn on clarinet and sax. It’s not the lavishly orchestrated jazz of Court and Spark, but the spark is there.

1970's Ladies of the Canyon was written and recorded at the height of Joni Mitchell's early phase while living in Laurel Canyon, and is a grand debut for the Joni of the 70s. It was here, on Ladies, that Joni started her venture into jazz. The album was produced by Joni, who also played piano, guitar and keyboards with a handful of jazz musicians, including Paul Horn on clarinet and sax. It’s not the lavishly orchestrated jazz of Court and Spark, but the spark is there. Deep in a relationship with Graham Nash, the songs reflect her homely life. "Willy" and "Blue Boy" are profound, gentle love songs to Nash, while "Morning Morgantown" and "Ladies of the Canyon" offer sweet, romantic small town portraits. Some of the lyrics have twee elements, and others are overly sweet or pretty, but there is an often underrated power to Joni’s hippie album. "For Free" is one of her strongest early songs, exploring the dichotomy between being a successful and wealthy recording artist and a modest street busker; it also features a dazzling clarinet solo at its climax.

"The Arrangement" is one of her first songs to explore jazz structures, if not jazz textures or arrangements. It is her most experimental and challenging song to this point, and also perhaps the least accessible. "Rainy Night House" and "The Priest" are two definite highlights, gems tucked away on this album. It takes a while for them to leap out, but they have immense staying power with their gorgeous melodies and heartfelt performances. Mitchell's voice is sweet and girlish here, somewhat odd compared with the deep tone on Clouds. It gives the album a pretty, romantic quality, and the hit "Big Yellow Taxi" is characteristic of the album's guitar-driven songs. "The Circle Game," a Joni Mitchell 'standard,' fits into this category.

Ladies of the Canyon also features piano prominently, a move Mitchell credited to listening to Laura Nyro, who was at this time perhaps a more sophisticated and developed artist. The album is notable for exploring woodwind for the first time, and it's the fullest-sounding of her early acoustic works. It also features her soaring electric piano rendition of "Woodstock."

Overall, Ladies of the Canyon was an important step forward for Joni Mitchell, adding texture and substance to her previously modest, understated acoustic pieces. She would explore these sounds further into the 1970s, but this is the most important albums in her artistic evolution.

Published on December 16, 2019 05:41

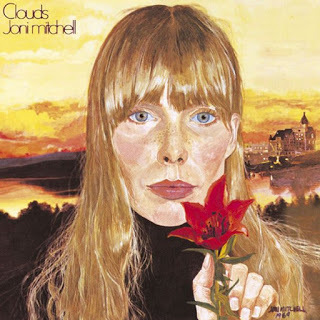

Song to a Seagull and Clouds

Recorded in the midst of the Vietnam War and surrounded by sweeping social changes, Joni Mitchell's 1968 underrated debut, Song to a Seagull (AM7), is an elegant and timeless microcosm. The songs are captivating and complex, drawing the listener into a misty and melancholic realm that fills the cracks between genres: a unique artistry that blends the heartfelt simplicity of folk, the rhythmic, youthful allure of rock and the expansive, detail-mindedness of classical. (Later she would incorporate the improvisational, bonds-loosened feel of jazz as well, not yet.) The sound of the recording is atmospheric and for the most part the music broods, yet Joni is the ultimate storyteller and the characters are portrayed with a strong sense of reality: songs about common relationships, people we may have met, emotions we too may feel or thoughts we may have once pondered. We know straight away that this is no average songwriter. Joni draws attention to certain lines in circumspect unfamiliar ways. In "Sisotowbell Lane" she takes the melody from the second to the last line of the verse and repeats it on the second to the last line of the chorus: simple complexity. The lyrics are similar, she holds a note on the verse and cuts off one from the chorus. This clipped note sets up for the last line of the chorus. The projected imagery expands from colorful to so vibrantly tactile you can touch it.

Recorded in the midst of the Vietnam War and surrounded by sweeping social changes, Joni Mitchell's 1968 underrated debut, Song to a Seagull (AM7), is an elegant and timeless microcosm. The songs are captivating and complex, drawing the listener into a misty and melancholic realm that fills the cracks between genres: a unique artistry that blends the heartfelt simplicity of folk, the rhythmic, youthful allure of rock and the expansive, detail-mindedness of classical. (Later she would incorporate the improvisational, bonds-loosened feel of jazz as well, not yet.) The sound of the recording is atmospheric and for the most part the music broods, yet Joni is the ultimate storyteller and the characters are portrayed with a strong sense of reality: songs about common relationships, people we may have met, emotions we too may feel or thoughts we may have once pondered. We know straight away that this is no average songwriter. Joni draws attention to certain lines in circumspect unfamiliar ways. In "Sisotowbell Lane" she takes the melody from the second to the last line of the verse and repeats it on the second to the last line of the chorus: simple complexity. The lyrics are similar, she holds a note on the verse and cuts off one from the chorus. This clipped note sets up for the last line of the chorus. The projected imagery expands from colorful to so vibrantly tactile you can touch it. The album reveals a master at work; not the work of a novice, these aren't the lyrics of a beginner, a flower child or a sophomoric "student" of art, but the uncommon work of a true artist. It's cerebral, beautiful, thought-provoking and mature - free of any pretense. Blue, Court and Spark, the jazz albums are Joni’s shining moments, but Song to a Seagull is quietly brooding magic, Joni's marriage of the earthy and the celestial (captured beautifully in David Crosby understated production). Most important is the imagery apparent within the groves; one can see her there in Laurel Canyon at the piano, David Crosby sitting on the couch behind her, Graham Nash at the dining table scribbling the lyrics to "Our House," the smell of eucalyptus in the air.

The album reveals a master at work; not the work of a novice, these aren't the lyrics of a beginner, a flower child or a sophomoric "student" of art, but the uncommon work of a true artist. It's cerebral, beautiful, thought-provoking and mature - free of any pretense. Blue, Court and Spark, the jazz albums are Joni’s shining moments, but Song to a Seagull is quietly brooding magic, Joni's marriage of the earthy and the celestial (captured beautifully in David Crosby understated production). Most important is the imagery apparent within the groves; one can see her there in Laurel Canyon at the piano, David Crosby sitting on the couch behind her, Graham Nash at the dining table scribbling the lyrics to "Our House," the smell of eucalyptus in the air. Song to a Seagull was released March 1, 1968, with production beginning sometime after August 1967, when Joni met David Crosby. Joni's second LP, Clouds (AM7) would not be released until May 1969, a long span for the era, offering her the luxury of time that many new artists weren't granted (standard contracts called for two LPs per year). Among Clouds' ten tracks, were her own versions of songs already covered by other artists, including "Chelsea Morning," "Tin Angel," and "Both Sides Now."

Song to a Seagull was released March 1, 1968, with production beginning sometime after August 1967, when Joni met David Crosby. Joni's second LP, Clouds (AM7) would not be released until May 1969, a long span for the era, offering her the luxury of time that many new artists weren't granted (standard contracts called for two LPs per year). Among Clouds' ten tracks, were her own versions of songs already covered by other artists, including "Chelsea Morning," "Tin Angel," and "Both Sides Now.""Both Sides Now," written more than a year before it ran up the charts for Judy Collins in 1968, was inspired by Saul Bellow's Henderson the Rain King on a jetliner; in particular, a passage where the main character is traveling by plane looking out over the clouds. The novel includes the line, "we are the first generation to see the clouds from both sides."

Joni's metaphor alluded to how children see clouds from the ground below, concocting fanciful and innocent images, then, as adults find nothing in them but inclement weather – indeed, both sides, the innocence, the trials and tribulations, the judgments of, let’s call it "the moon and the stars." Joni just didn't understand life or love at all. She was 21. Probably still doesn’t.

Other songs on the Clouds LP, mostly written in late 1967 and early '68, deal with love, lovers, unrequited love, the uncertainty of love, you get the point, in tracks like "I Don’t Know Where I Stand," "Tin Angel," "That Song About the Midway," and "The Gallery." But Clouds also includes "The Fiddle and The Drum," a song that compares America during the Vietnam War to a bitter friend, and "I Think I Understand, which is about mental illness.

In 1969, Joni Mitchell’s Clouds rose to No. 22 on the Canadian chart and No. 31 on the Billboard 200. Mitchell produced all the songs on the album (except for one), played acoustic guitar and keyboards, and was joined by Stephen Stills on bass guitar for just one track. Clouds brought Joni Mitchell a Grammy Award for Best Folk Performance. On Clouds, as well as Song To A Seagull we encounter a woman in a tug of war between innocence and experience. Joni's painterly influence on her compositions is in full evidence on both early LPs, from the Rembrandt browns of "Tin Angel" to the bright golds and yellows of "Chelsea Morning." The experience of innocence: as difficult a concept as the child being father to the man.

Side note: Bill and Hillary Clinton would go on to name their daughter, Chelsea, after the Mitchell track.

We are the first generation to see the clouds from both sides. - Saul Bellow

Published on December 16, 2019 05:35

December 13, 2019

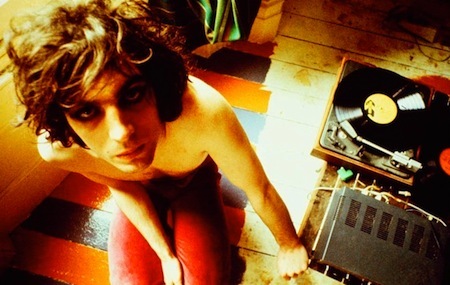

Syd - 50 Years Ago - The Madcap Laughs

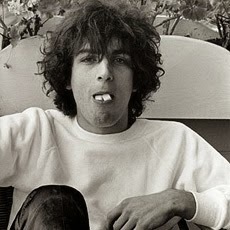

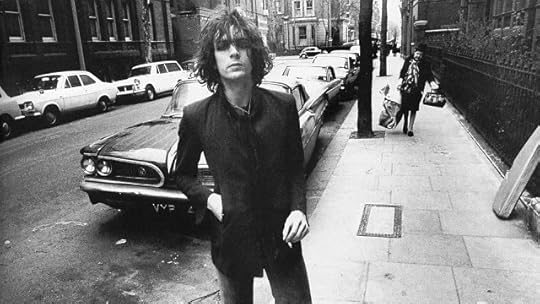

Syd Barret was a martyr for 60's extremism, a man whose mental health issues were exacerbated by drug use, particularly LSD, and who would spend his life, after founding Pink Floyd, in obscurity. After his departure, Roger Waters became the principal songwriter for the band that in the 1970s offered up Dark Side of the Moon (AM10), an album that spent 736 weeks on Billboard’s Top 100 (more than 14 years). Following the release of Piper at the Gates of Dawn, Syd Barrett's decline into obsuricty became apparent, flipping out in classic 60s burnout fashion. Barret would contribute to Pink Floyd's sophomore effort, but by December '67, Pink Floyd would add guitarist David Gilmour to the lineup to compensate for Barrett’s erratic behavior, and by March of the following year, Barrett would leave the band.

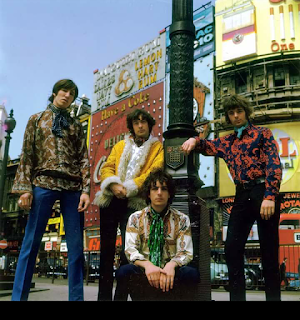

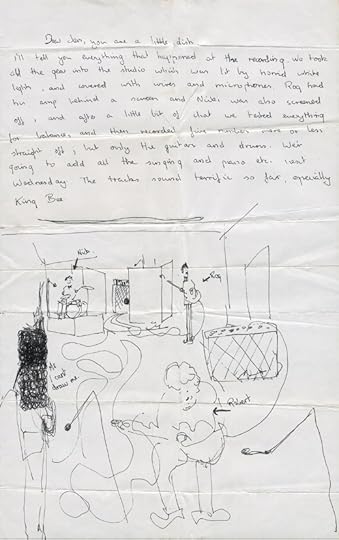

Syd Barret was a martyr for 60's extremism, a man whose mental health issues were exacerbated by drug use, particularly LSD, and who would spend his life, after founding Pink Floyd, in obscurity. After his departure, Roger Waters became the principal songwriter for the band that in the 1970s offered up Dark Side of the Moon (AM10), an album that spent 736 weeks on Billboard’s Top 100 (more than 14 years). Following the release of Piper at the Gates of Dawn, Syd Barrett's decline into obsuricty became apparent, flipping out in classic 60s burnout fashion. Barret would contribute to Pink Floyd's sophomore effort, but by December '67, Pink Floyd would add guitarist David Gilmour to the lineup to compensate for Barrett’s erratic behavior, and by March of the following year, Barrett would leave the band. Waters, Mason, Barrett, WrightRoger Keith Barrett had attained the nickname "Syd" by 1963. By then he was writing nearly obsessively and honing his songwriting abilities. He carried a notebook called “Roger’s Songs” everywhere he went. He formed a blues/R&B band called Those Without, yet a turning point came in November that year when Syd, accepted at London’s Camberwell Art School ran into Cambridge friend, Roger Waters. Waters asked Syd to join his band, which among other names had gone by The T-Set and The Abdabs. The line-up included Nick Mason on drums and Rick Wright on keyboards. Syd mentioned that two of his favorite bluesmen (both from Georgia) were Pink Anderson and Floyd Council. Pink Floyd officially took off on their new journey with a gig in 1965. There are those who would argue, but Pink Floyd was Syd's band only in name; the found of Pink Floyd was clearly Waters.

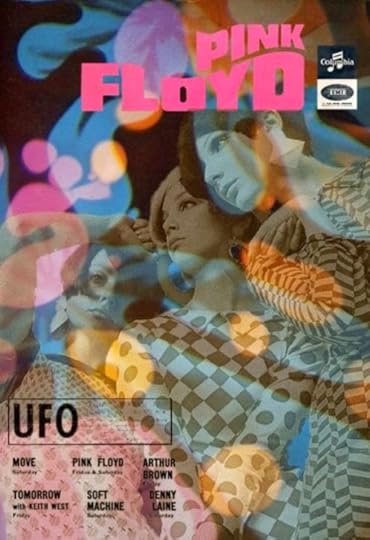

Waters, Mason, Barrett, WrightRoger Keith Barrett had attained the nickname "Syd" by 1963. By then he was writing nearly obsessively and honing his songwriting abilities. He carried a notebook called “Roger’s Songs” everywhere he went. He formed a blues/R&B band called Those Without, yet a turning point came in November that year when Syd, accepted at London’s Camberwell Art School ran into Cambridge friend, Roger Waters. Waters asked Syd to join his band, which among other names had gone by The T-Set and The Abdabs. The line-up included Nick Mason on drums and Rick Wright on keyboards. Syd mentioned that two of his favorite bluesmen (both from Georgia) were Pink Anderson and Floyd Council. Pink Floyd officially took off on their new journey with a gig in 1965. There are those who would argue, but Pink Floyd was Syd's band only in name; the found of Pink Floyd was clearly Waters. The band's gigs at The Marquee and UFO brought them to the attention of Peter Jenner and Andrew King, who would both eventually sign on as managers. The first was an intricate light show, something that had never been seen in England before. The only other band at doing something similar of course was The Velvet Underground. The second factor was the band's decision to do strictly originals, a concept that in '65 even the Beatles had not accomplished.

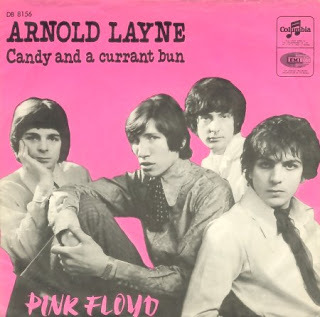

The band's gigs at The Marquee and UFO brought them to the attention of Peter Jenner and Andrew King, who would both eventually sign on as managers. The first was an intricate light show, something that had never been seen in England before. The only other band at doing something similar of course was The Velvet Underground. The second factor was the band's decision to do strictly originals, a concept that in '65 even the Beatles had not accomplished.The duality of Syd's influence was reflected on the two disparate sides to the band’s music. The "A" side featured long free-form instrumentals like "Interstellar Overdrive" and "Astronomy Domine," which highlighted the freak-outs at UFO. The "B" side was the poppy side, which Jenner and King hoped to exploit for commercial purposes. Syd was pushed to the forefront and told to "Come up with a hit song." At the same time, LSD was becoming the drug of choice over pot among the Swingin' London Set and Syd was an overzealous participant. On March 10, 1967, Pink Floyd’' first single "Arnold Layne" was released by EMI and became a UK Top 20 hit, though it was banned by Radio London as "too smutty." The second single “See Emily Play” was released on June 16, 1967 and was also a UK smash. The song was based on a 16-year-old schoolgirl who frequented Floyd shows but was made fun of by the older crowd ("Emily tries but misunderstands."). Suddenly Pink Floyd was a pop sensation, even appearing on "Top Of The Pops."

Syd's contribution to The Piper at the Gates of Dawn success was immeasurable. He wrote all the songs except one and created a sonic landscape of guitar effects using wah-wah, distortion and other strange methods (such as playing with a ruler) to create the albums revolutionary atmospherics. Although Piper was well received in both the UK and abroad, the pressure was on Syd to produce the next big single. When "Apples and Oranges" was released on Nov 17, 1967, it tanked. Syd said he "Couldn’t care less," but this was probably not the case. Syd was starting to crack under the strain. TV appearances in the U.S. were so awful that the band agreed that something had to be done. American Bandstand required a mime job and The Pat Boone Show was even worse. Syd refused to answer any of the host's questions, just staring into space instead.

Syd's contribution to The Piper at the Gates of Dawn success was immeasurable. He wrote all the songs except one and created a sonic landscape of guitar effects using wah-wah, distortion and other strange methods (such as playing with a ruler) to create the albums revolutionary atmospherics. Although Piper was well received in both the UK and abroad, the pressure was on Syd to produce the next big single. When "Apples and Oranges" was released on Nov 17, 1967, it tanked. Syd said he "Couldn’t care less," but this was probably not the case. Syd was starting to crack under the strain. TV appearances in the U.S. were so awful that the band agreed that something had to be done. American Bandstand required a mime job and The Pat Boone Show was even worse. Syd refused to answer any of the host's questions, just staring into space instead.Barrett would go on to release two LPs, each showcasing what may have been, though The Madcap Laughs makes Barrett's marginal functionality obvious through his often rambling incoherent lyrics and out of time backing tracks. It's an effort not without its charm, and it's an ultimately sad indicator of who Syd could have been, particularly the out of nowhere "No Man's Land" and the Floydesque "Long Gone." The album was recorded throughout 1968 and 1969 with producers Malcolm Jones who produced most of the first half of the disc and the closing classic "Late Night." The rest of the tracks were produced by Roger Waters and David Gilmour.

Gilmour and Richard Wright got Syd back into the studio to cut Barrett, with Gilmour on bass, Wright on keyboards and Humble Pie's Jerry Shirley on drums, but this illusion of a real band only negated the charm. Barrett and The Madcap Laughs are definitely worth a listen. If not time well spent (I'd rather suggest listening to The Soft Machine, who's obscurity is absurd rather than self-inflicted). By this point, the effects of Syd's drug use sadly started to deteriorate his songwriting skills and his mental state (he sadly passed away from pancreatic cancer in 2006). There are those who look back on Piper and the singles and envision a Floyd with a coherent, healthy Syd. To me, that scenario obfuscates Dark Side and Wish You Were Here; I cannot even fathom such a world.

Published on December 13, 2019 13:54

Acid Casualty - Part 2

Most writers focus on Syd's "deterioration" as the reason for the breakdown/breakup with Pink Floyd, and while there's no denying it, a component is missing in that theory. As the band began to attract a larger fanbase, it became clear that Syd's fluid approach to writing, performing and recording – spontaneous, one take only, nothing repeated – was increasingly at odds with the expectations of the band. After bringing in Gilmour, Pink Floyd hoped to call on Syd's compositional artistry for their studio work – similar to not-quite-as-crazy Brian Wilson's role in the Beach Boys – while David Gilmour bolstered the band in live performances. The experiment didn't work and, in January 1968, after a handful of shows as 5-piece, the band elected not to pick Syd up on the way to a Southampton University show. So it goes.

Most writers focus on Syd's "deterioration" as the reason for the breakdown/breakup with Pink Floyd, and while there's no denying it, a component is missing in that theory. As the band began to attract a larger fanbase, it became clear that Syd's fluid approach to writing, performing and recording – spontaneous, one take only, nothing repeated – was increasingly at odds with the expectations of the band. After bringing in Gilmour, Pink Floyd hoped to call on Syd's compositional artistry for their studio work – similar to not-quite-as-crazy Brian Wilson's role in the Beach Boys – while David Gilmour bolstered the band in live performances. The experiment didn't work and, in January 1968, after a handful of shows as 5-piece, the band elected not to pick Syd up on the way to a Southampton University show. So it goes.Syd and Floyd officially parted company in March 1968 and EMI's new Harvest label committed to a Barrett solo project. Over the course of a year, Syd recorded The Madcap Laughs. Recording commenced in earnest in April 1969 with EMI's Malcolm Jones alongside David Gilmour, Rick Wright and Roger Waters.

Thanks only to Yoko Ono, every piece of crap that John Lennon ever wrote is available in a myriad of formats. From a historical view, that’s a bonus; the ability to look deeply into the processes of Lennon's writings, good, bad and ugly. But it's not what John would have wanted. Like William Butler Yeats, Lennon wanted his finished works to look effortless. They were not. He toiled over every track he released. Syd Barrett, on the other hand, didn’t care. His output was out there; if not his life, he wore his art on his sleeve. And so, released in January 1970, we have the sprawling, raw, insane The Madcap Laughs, in which the first seven cuts are brilliance, with the bullshit (bar "Octopus" and "Late Night") tagged onto side-two. From the hypnotic, bluesy opener "Terrapin", to the Soft Machine drenched astral psychedelia of "No Good Trying" where Syd's guitar, distorted organ solos, fuzz bass and blasting drums are all played with no-holds-barred insanity, Madcap show a promise from Barrett that Pink Floyd lacked after his departure. The jaunty lounge-bar, piano-driven ditty "Love You," the distorted rocker "No man's Land," the acoustic "Dark Globe" and a skewed love song called "Here I go" help to convey a sense that Barrett, not Floyd, would find his niche, particularly amidst the Soft Machine backdrop.

Thanks only to Yoko Ono, every piece of crap that John Lennon ever wrote is available in a myriad of formats. From a historical view, that’s a bonus; the ability to look deeply into the processes of Lennon's writings, good, bad and ugly. But it's not what John would have wanted. Like William Butler Yeats, Lennon wanted his finished works to look effortless. They were not. He toiled over every track he released. Syd Barrett, on the other hand, didn’t care. His output was out there; if not his life, he wore his art on his sleeve. And so, released in January 1970, we have the sprawling, raw, insane The Madcap Laughs, in which the first seven cuts are brilliance, with the bullshit (bar "Octopus" and "Late Night") tagged onto side-two. From the hypnotic, bluesy opener "Terrapin", to the Soft Machine drenched astral psychedelia of "No Good Trying" where Syd's guitar, distorted organ solos, fuzz bass and blasting drums are all played with no-holds-barred insanity, Madcap show a promise from Barrett that Pink Floyd lacked after his departure. The jaunty lounge-bar, piano-driven ditty "Love You," the distorted rocker "No man's Land," the acoustic "Dark Globe" and a skewed love song called "Here I go" help to convey a sense that Barrett, not Floyd, would find his niche, particularly amidst the Soft Machine backdrop. While "Octopus" sums up Syd's sad story ("Isn't it good/ Lost in the woods/ Isn't it bad/ So quiet there/ In the woods), don’t confuse intrigue with anything more than an AM6+; this is far from Piper, with only "Octopus" coming close to "Arnold Layne" or "See Emily Play" (and Madcap is slightly better than Barrett).

While "Octopus" sums up Syd's sad story ("Isn't it good/ Lost in the woods/ Isn't it bad/ So quiet there/ In the woods), don’t confuse intrigue with anything more than an AM6+; this is far from Piper, with only "Octopus" coming close to "Arnold Layne" or "See Emily Play" (and Madcap is slightly better than Barrett). The Madcap Laughs was well received and sold reasonably by the standards of the time, so EMI decided to record a follow-up straightaway. The sessions for the album Barrett started in February 1970, with David Gilmour as producer, Richard Wright on keyboards and Humble Pie's Jerry Shirley on drums. The album was released in November 1970.

Syd was pretty much a wreck of a man by this time, but managed, with the help of Gilmour and Wright, to create his most sane if over-polished pop offering. It's not as good or as consistent as The Madcap Laughs or Piper, and while it's no Pink Moon, it's still pretty damn compelling as far as albums written by drug-riddled folksy artists go. Considering his state of mind at the time, and how he still had some negative vibes towards Gilmour and Waters for taking control of "his" band, this is a trippy reminder of just how much Syd could play the strings of a listener's soul and mess with his head so much that he has to stop and figure out what the hell he just heard. It's eerily brilliant and deranged, and because of that, it doesn't hold up as much as it could have if Syd had complete control of his mind, which wandered and wavered in a sea of abstract uncertainty, but then it wouldn't have been Syd.

In 1970 after the release of Barrett, David Gilmour and Jerry Shirley backed Syd for his one and only live concert. The trio played four songs at the Olympia Exhibition Hall in London as part of a Music and Fashion Festival. Syd made one last appearance on BBC Radio with three songs from his sophomore effort on February 16, 1971.

In 1972, Syd formed a short-lived band called Stars with ex-Pink Fairies member Twink on drums and Jack Monck on bass. Though the band was initially well received, one of their gigs at the Corn Exchange in Cambridge was disastrous, and Syd quit the band after a scathing review. In August 1974, Peter Jenner convinced Syd to return to Abbey Road Studios in hope of recording another album, but little came of the sessions. Syd withdrew from the music industry and subsequently returned to Cambridge for a life of painting, creating large abstract canvases. Syd had one noted reunion with the members of Pink Floyd on June 5, 1975 during the recording sessions for Wish You Were Here, when he turned up at Abbey Road unannounced as the band was working on "Shine On You Crazy Diamond," itself a dedication to absent friends, including their erstwhile leader. As the story goes, the members of Pink Floyd didn't even recognize who he was.

There isn't much to the Barrett canon: a few singles, Piper, Madcap and Barrett, and his life overshadows his music, but step back from that and just listen with a British ear: you'll hear England amidst the insanity with odd snippets of reality smouldering underneath. It's like if The Wind in the Willows was set to music.

Published on December 13, 2019 13:34

Acid Casualty - Syd Barrett - Part 1

Some 51 years ago The Pink Floyd recorded their first single, "Arnold Layne," a psychedelic bauble written by the not quite [yet] madcap Syd Barrett about a transvestite who steals ladies' underwater off backyard clotheslines. Radio London banned the track, but "Arnold Layne" made the UK top 20. In March 1967, the band recorded a follow-up, the sparklingly sinister "See Emily Play," one of the great tracks in British psychedelia, a song that I didn't discover until the David Bowie cover LP Pinups. It went top 10 and Pink Floyd (sans definite article) would soon lose Barrett, whose drug use and increasingly distracted behavior got him kicked out of the band by early '68; Barrett's behavior is ofttimes described as that of an "Acid Casualty." Syd recorded two solo efforts, moved back in with his mum, and took to gardening, while his ghoulish presence imbued his former band's greatest works, Dark Side of the Moon and Wish You Were Here. He died of cancer in 2006.

Some 51 years ago The Pink Floyd recorded their first single, "Arnold Layne," a psychedelic bauble written by the not quite [yet] madcap Syd Barrett about a transvestite who steals ladies' underwater off backyard clotheslines. Radio London banned the track, but "Arnold Layne" made the UK top 20. In March 1967, the band recorded a follow-up, the sparklingly sinister "See Emily Play," one of the great tracks in British psychedelia, a song that I didn't discover until the David Bowie cover LP Pinups. It went top 10 and Pink Floyd (sans definite article) would soon lose Barrett, whose drug use and increasingly distracted behavior got him kicked out of the band by early '68; Barrett's behavior is ofttimes described as that of an "Acid Casualty." Syd recorded two solo efforts, moved back in with his mum, and took to gardening, while his ghoulish presence imbued his former band's greatest works, Dark Side of the Moon and Wish You Were Here. He died of cancer in 2006.

Put like that, Syd's story is really quite tepid. I've tried to decode and understand the life of the elusive enigma that was Syd for a very long time. While the band ousted Barrett, part of me thinks that he wanted exactly that; Syd was too much the genius, and no one knows exactly how much acid he took and how frequently he tripped, the dosage back then severe and pure. Couple this with his schizophrenia and bam! Back in the 60s, acid was everywhere and so many voyagers ignited their pineal glands in amazement, taking too much (the heroic dose), too frequently, and Syd was the first in line. (I'm reminded of high school in the 70s. The acid didn't flow as easily by then, but I remember a kid on the bus in the morning who had taken acid 13 days in a row. I was in awe of him. Through my college years and my minimal experiences with LSD, I can say for a fact that I could only do it back then because I had the brash bravery of my youth – I couldn't do it anymore and quite frankly I'm scared to.)

My theory rests on the fact that Syd didn't like the limelight, and that, like so many artists, his art, not his success as an artist, was key in his synesthetic-psyche. Syd was a gallant soul, and while he may have "reached for the secret too soon" and, you know, "cried for the moon," maybe he just wanted to be left alone.

It's a coincidence that AM has taken this route as a mini-history of progressive rock and that I have started watching Philip K. Dick's Electric Dreams. The 2nd episode is amazing, by the way, but episode four (the least amazing I’ve seen so far, but still intriguing), begins with Steve Buschemi listening to a cover version of Barrett's "Octopus." And so, in the Pink Floyd spirit that follows along this prog history, I've taken up the task of looking further into Barrett, not as an acid casualty, but as a reclusive artist. What follows is far from comprehensive and merely a smattering of research that reflects Syd's art and artistry.

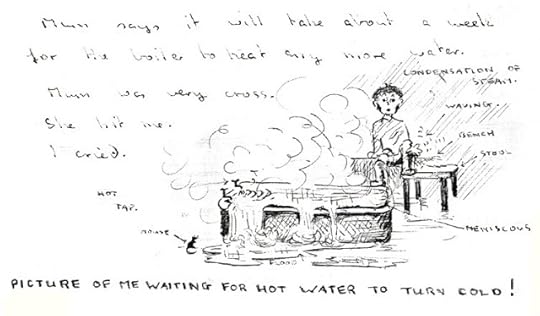

In the graphic above, Syd probably messed up the water heater at his childhood home and wrote, "Mum was very cross. She hit me. I cried." There's artistry right there, and in it, there is little question that Syd Barrett was one of the "umma" (the brotherhood of prophets - see Herbert's "Dune") and "just mad enough to be holy." Barrett's madness was not quite a sudden explosion, however, but rather a gradual implosion, the clues to which he articulated in his music long before his behavior signaled distress. Syd's songs contained warnings from the beginning: he dealt with instability and the primal need for comfort via authority's fairytales ("Matilda Mother"), the desire for control of a situation and the outsider/observer role ("Flaming"), while even "Jugband Blues" (on Floyd's Saucerful Of Secrets) spelled out inner conflicts. By the time of The Madcap Laughs and Barrett, Syd's songs clearly revealed raw spots in his psyche amid the poetically jumbled voodoo of his writing.

In the graphic above, Syd probably messed up the water heater at his childhood home and wrote, "Mum was very cross. She hit me. I cried." There's artistry right there, and in it, there is little question that Syd Barrett was one of the "umma" (the brotherhood of prophets - see Herbert's "Dune") and "just mad enough to be holy." Barrett's madness was not quite a sudden explosion, however, but rather a gradual implosion, the clues to which he articulated in his music long before his behavior signaled distress. Syd's songs contained warnings from the beginning: he dealt with instability and the primal need for comfort via authority's fairytales ("Matilda Mother"), the desire for control of a situation and the outsider/observer role ("Flaming"), while even "Jugband Blues" (on Floyd's Saucerful Of Secrets) spelled out inner conflicts. By the time of The Madcap Laughs and Barrett, Syd's songs clearly revealed raw spots in his psyche amid the poetically jumbled voodoo of his writing.

What Syd created in sound and imagery was brand new; no one had yet discovered Hendrix and the Beatles were just recording Sgt. Pepper (at the same time and in the same studios) as Pink Floyd were cutting Piper. Barrett's music was as experimental as you could get without crossing over entirely into freeform jazz; there simply were no other bands extending the boundaries of rock beyond the basic 4/4 sex-and-love themes. Funny what happens simultaneously - Pepper, Velvet Underground and Nico, King Crimson, Cream - squint a little, drink the Kool-Aid and maybe Syd is the catalyst for all of it. Syd certainly listened to American jazz, blues, jug band music and rock, as did most young British rock 'n' rollers of the time. He used to cite Bo Diddley as his major influence, yet each of these is no more than alluded to in his music, which contains every style of guitar playing imaginable: funky rhythm churns up speeding riffs that distort into jazzy improvisational blues. At times an Eastern influence surfaces, blending vocal chants, jangling guitar and devotional hum in tunes like "Matilda Mother" and the lovely I Ching-inspired "Chapter 24."

His trademark (and Achilles heel) was sudden surprise: trance-like riffs would slide abruptly into intense, slightly offbeat strumming ("Astronomy Domine"), choppy urgency gives way to powerful, frightening peaks ("Interstellar Overdrive"), harmless lyrics skitter over a fierce undertow of evil-sounding feedback and menacing wah-wah ("Lucifer Sam"). Stylized extremes made Barrett's guitar the focus of Floyd's early music; his instrumental mannerisms dominated each song even when Syd merely played chords. Barrett's rhythms were usually unpredictable; one never knew what process in Syd's brain dictated when to speed up or slow down the pace, when to sweeten or sour the sound, and when to wrench the tempo totally out of joint, shifting gears to turn rhythms inside-out. As a result, Barrett's playing was variously described by critics as "clumsy and anarchic," "adventurous and distinctive," "idiosyncratic," "revolutionary" or "brilliant and painful."

Syd's influence on Pink Floyd continued to manifest itself long after he left the band. Carrying on without him was difficult at first since the public and the label obviously felt that Syd was all the band had, which led theoretically to the band's decision to concentrate on the filmscores.

Published on December 13, 2019 13:33

December 12, 2019

Troubled Waters

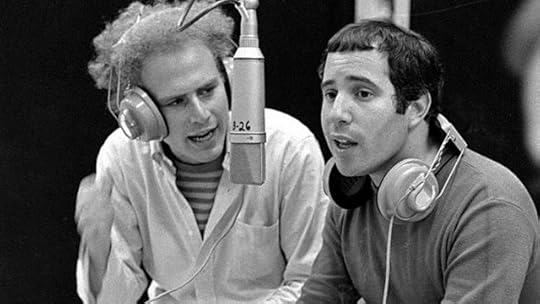

One of my Top 20 LPs is Simon and Garfunkel's Bookends, with classics like "The Zoo" and "Mrs. Robinson," but more specifically, the beautiful title track, Old Friends and one of the most poignant and beautiful songs ever released, "America."

One of my Top 20 LPs is Simon and Garfunkel's Bookends, with classics like "The Zoo" and "Mrs. Robinson," but more specifically, the beautiful title track, Old Friends and one of the most poignant and beautiful songs ever released, "America."The duo would follow up with Bridge Over Troubled Water, their 5th and final LP. Simon would continue writing and performing, and Garfunkel would pursue his film career before releasing his solo LPs. 1970 was a contentious year for the duo and despite the incredible success of their final LP, with the No. 1 title smash, the recording of the LP was laborious, particularly the production of "The Boxer." The pair, because of the lengthy recorded process, declined to perform at Woodstock. With production of The Boxer lasting more than 100 studio hours (unheard of), there was just no time.

The initial recording session for "The Boxer" was at Columbia Recording Studios in New York. Based on other obligations, including Art Garfunkel's role in Mike Nichol's Catch 22, the 2nd session was delayed and then recorded at Columbia in Nashville. Back to NYC for the third and final section, for which the horns were recorded at St. Paul's Chapel at Columbia University, then back to the studio for the strings. Hal Blaine's echo chamber reverb effect for the drums was recorded in a hallway with a tiled floor. "There we were with all these mic cables, my drums, and a set of headphones," said Blaine. "When the chorus came around — the 'lie-la-lie' bit — Roy had me come down on my snare drum as hard as I could. In that hallway, right next to this open elevator shaft, it sounded like a cannon shot! Which was just the kind of sound we were after." The incredible guitar is by Nashville's Fred Carter Jr. Of the session, Carter said, "Paul and I sat down to cut the basic track, and suddenly I’m surrounded by seven or eight different microphones — in front, behind . . . he even mic'ed my breathing!"

Like Bookends, the album's recording was quite experimental, including the use of 16 tracks (actually, two 8 track recording units) and while it proved a monster success, by the time Bridge was complete on January 26, 1970, so was the career of the duo. Bridge Over Troubled Water would go on to become Simon and Garfunkel's greatest success, scoring a sea of Grammys and topping album surveys worldwide (in the U.K. it charted for more than 300 weeks total, 41 of them at number one).

Published on December 12, 2019 06:27

Miles From Nowhere

Miles From Nowhere...

...is available on Amazon and for your Kindle!

Join Miles for free on Kindle Unlimited or order the Kindle version for $2.99. The softbound version is $10.99.

Miles From Nowhere is a rock 'n' roll pilgrimage, the journey of a young man in poor health as he travels from California to Woodstock to see his idol, Jimi Hendrix. Along the way, he meets friends and family, an entourage of hippies and bohemians, musicians and socialites, and each time you put the novel down you'll have another familiar song in your head.

Order your copy of Miles From Nowhere on Amazon or click the links in the sidebar. Order here on the website and get a personally autographed copy for just $11.00 including shipping.

Published on December 12, 2019 05:26

December 11, 2019

1969 45s and the End of AM Radio

1969 was the year of the Beatles' "Come Together" and "Something," their double A-sided No. 1 smash, Led Zeppelin's "Whole Lotta Love," David Bowie's "Space Oddity," the Rolling Stones' "Honky-tonk Women," "Pinball Wizard" from The Who, Elvis Presley's comeback No. 1 single "In the Ghetto," and Crosby Stills and Nash's "Suite: Judy Blue Eyes." There was "Touch Me" from The Doors, "Venus" from Shocking Blue, on and on. I know this just seems like an endless refrigerator list, because it is. Here's more: Neil Diamond's "Sweet Caroline," The Temptations' "Psychedelic Shack," and Badfinger's "Come and Get It," which people thought was the Beatles. One of my favorite story songs, Glen Campbell's version of "Galveston" by Jimmy Webb.How about "The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face" from Roberta Flack, Blood Sweat and Tears' "Spinning Wheel," Peter Paul and Mary's "Leaving on a Jet Plane," and we're only talking huge hits so far. Here's one a bit more obscure but still classic: "White Bird" from It's a Beautiful Day.1969 was really the end of an era in that it was also the first year of AOR, Album Oriented Rock. AM was on its way out and FM would become the new mainstay. But what a way to go. For all the new bands that were created in 1969 like Jethro Tull and Led Zeppelin, FM radio would give them a voice.

1969 was the year of the Beatles' "Come Together" and "Something," their double A-sided No. 1 smash, Led Zeppelin's "Whole Lotta Love," David Bowie's "Space Oddity," the Rolling Stones' "Honky-tonk Women," "Pinball Wizard" from The Who, Elvis Presley's comeback No. 1 single "In the Ghetto," and Crosby Stills and Nash's "Suite: Judy Blue Eyes." There was "Touch Me" from The Doors, "Venus" from Shocking Blue, on and on. I know this just seems like an endless refrigerator list, because it is. Here's more: Neil Diamond's "Sweet Caroline," The Temptations' "Psychedelic Shack," and Badfinger's "Come and Get It," which people thought was the Beatles. One of my favorite story songs, Glen Campbell's version of "Galveston" by Jimmy Webb.How about "The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face" from Roberta Flack, Blood Sweat and Tears' "Spinning Wheel," Peter Paul and Mary's "Leaving on a Jet Plane," and we're only talking huge hits so far. Here's one a bit more obscure but still classic: "White Bird" from It's a Beautiful Day.1969 was really the end of an era in that it was also the first year of AOR, Album Oriented Rock. AM was on its way out and FM would become the new mainstay. But what a way to go. For all the new bands that were created in 1969 like Jethro Tull and Led Zeppelin, FM radio would give them a voice.

And while the biggest selling album of the year would be the Beatles' Abbey Road, The No. 1 single of the year was the Archie's "Sugar Sugar;" now that's diversity. The Archies, by the way, are the only animated group ever to reach the number one spot. Again, that's diversity.

And while the biggest selling album of the year would be the Beatles' Abbey Road, The No. 1 single of the year was the Archie's "Sugar Sugar;" now that's diversity. The Archies, by the way, are the only animated group ever to reach the number one spot. Again, that's diversity.On the AM network, we always look back 50 years and in 2020, as we look back to 1970, we've got some great music in store, but I am going to miss talking about 1969.

Published on December 11, 2019 05:49