R.J. Stowell's Blog: rjsomeone, page 16

October 2, 2020

Ah, Diversity - 50 Years Ago

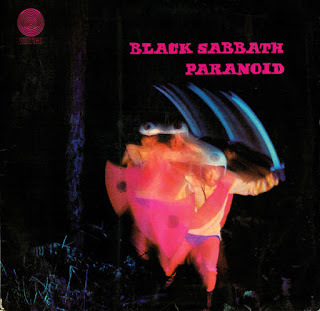

It was 50 years ago that Black Sabbath released their most famous LP, Paranoid. I'm one to appreciate their less-metal debut, but no one will argue that Paranoid is the forerunner to Heavy Metal. Other bands were as hard-rocking as Black Sabbath – The 13th Floor Elevators, Blue Cheer, The MC5 – but it was Paranoid that ushered in metal. Not only did the album serve as a catalyst, the band's persona created a whole new genre. "Iron Man" remains one of those "riffs that must not be played" (there’s a Harry Potter reference there, if lame) at Sam Ash and Guitar Center. Only "Smoke on the Water" gets played poorly more often.

AM radio, while in its death throes in the early 70s as listeners switched over to the stereo counterpoint, FM, was still in that Top 30 mode that served the eclectic. Listening to a Yachtrock channel on Sirius the other day (you know how I despise that term), it struck me that Sirius and Spotify led to the current lack of diversity. While AM stations were simultaneously the home of Motown, Beatles, R&B, rock and blues (etc.), streaming services offer musical genres and stick to them. AM, indeed, was so diverse that, 50 Years ago, as we listened to "Iron Man" on the local station, the next track could very well be "I Woke Up In Love This Morning" by the Partridge Family.

It was in September 1970 that ABC added to a family line-up that included The Brady Bunch. The Partridge Family debuted as one of the most popular shows of the early 70s. The "band" was headed by Shirley Partridge (Shirley Jones - Broadway and movie star) and Keith Partridge (David Cassidy) and backed, not by other "family" members, but by L.A,'s famous session musicians, The Wrecking Crew. The Partridge Family had 9 hits on American Top 40, three in the Top 10, and one, "I Think I Love You," making it to the top spot.

It was in September 1970 that ABC added to a family line-up that included The Brady Bunch. The Partridge Family debuted as one of the most popular shows of the early 70s. The "band" was headed by Shirley Partridge (Shirley Jones - Broadway and movie star) and Keith Partridge (David Cassidy) and backed, not by other "family" members, but by L.A,'s famous session musicians, The Wrecking Crew. The Partridge Family had 9 hits on American Top 40, three in the Top 10, and one, "I Think I Love You," making it to the top spot.

So there you go, diversity in a nutshell, Black Sabbath vs. The Partridge Family.

#milesfromnowhere

September 30, 2020

Bowie - An Early History

I guess one could go back to St. Mary's Church Choir in Bromley, 1958, for David Jones' first concert performance, but more legitimately (some would argue), Jones's first real concert gigs were with The Konrads in 1962, The King Bees in January 1964, or The Manish Boys in March 1964. We'll start there. The Manish Boys were Davie Jones (vocals, sax), Johnny Flux (lead), John Watson (guitar, vocals), Bob Solly (organ), Paul Rodriguez (bass, trumpet), Wolfe Byrne (bari sax, harmonica) and Mike White (drums). Jones joined the band in '64 and for the next year, until March 1965, The Manish Boys (changing their name to Davy Jones and the Manish Boys in June) played a myriad of venues (in particular, a six-date tour opening for Gerry and the Pacemakers in December 1964. Also on the bill were The Kinks, Gene Pitney and Marianne Faithful.) and cut their first and only record, "I Pity the Fool" b/w "Take My Tip" in March 1965. In April 1965, Jones joined established band The Lower Third, while continuing to play with The Manish Boys. In August 1965, Davie Jones and The Lower Third supported The Who in Bournemouth.

I guess one could go back to St. Mary's Church Choir in Bromley, 1958, for David Jones' first concert performance, but more legitimately (some would argue), Jones's first real concert gigs were with The Konrads in 1962, The King Bees in January 1964, or The Manish Boys in March 1964. We'll start there. The Manish Boys were Davie Jones (vocals, sax), Johnny Flux (lead), John Watson (guitar, vocals), Bob Solly (organ), Paul Rodriguez (bass, trumpet), Wolfe Byrne (bari sax, harmonica) and Mike White (drums). Jones joined the band in '64 and for the next year, until March 1965, The Manish Boys (changing their name to Davy Jones and the Manish Boys in June) played a myriad of venues (in particular, a six-date tour opening for Gerry and the Pacemakers in December 1964. Also on the bill were The Kinks, Gene Pitney and Marianne Faithful.) and cut their first and only record, "I Pity the Fool" b/w "Take My Tip" in March 1965. In April 1965, Jones joined established band The Lower Third, while continuing to play with The Manish Boys. In August 1965, Davie Jones and The Lower Third supported The Who in Bournemouth. On September 16, 1965, Jones officially and legally changed his name to David Bowie to avoid any conflict with Oliver star (as The Artful Dodger) and Monkee Davy Jones. In February 1966, Bowie held auditions for his new band, tentatively called The Buzz; its members included John Hutchinson on guitar, Derek Fearnley on bass, John Eager on drums and Derrick Boyle on drums. Bowie, with backing from The Buzz would start a sojourn at the Marquee club in June 1966.

On September 16, 1965, Jones officially and legally changed his name to David Bowie to avoid any conflict with Oliver star (as The Artful Dodger) and Monkee Davy Jones. In February 1966, Bowie held auditions for his new band, tentatively called The Buzz; its members included John Hutchinson on guitar, Derek Fearnley on bass, John Eager on drums and Derrick Boyle on drums. Bowie, with backing from The Buzz would start a sojourn at the Marquee club in June 1966. This article does not effectively portray the number of dates played by Bowie exerting what would remain an unstoppable work ethic. Amidst gigs with The Lower Third and The Buzz, Bowie soloed with The Bill Saville Orchestra, performed a number of mime acts with a troupe called Turquoise and played with The Strawbs, where he first met Rick Wakeman (Wakeman would go on to be instrumental on Hunky Dory, of course, playing the piano on "Life on Mars").

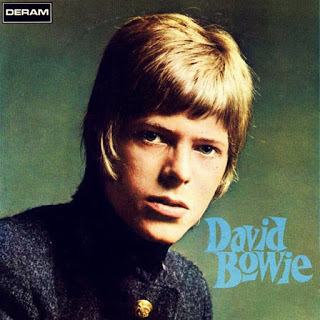

Bowie's first album originally released in June 1967 is a pretty cool little record. How’s that for skirting the issue that while many debuts remain an artist's greatest effort (think Rickie Lee Jones, The Killers, The Beastie Boys)? If you like quirky mid-60's British pop, then you really can't go wrong here. "Join the Gang" is a rip on "Swinging London" and a personal fave. "Rubber Band" is a fun nostalgia trip on big bands during the Great War. "Uncle Arthur" is a silly song about the ultimate mama's boy. "When I Live My Dream" is generally considered the best song on the disc; it definitely seems the most mature. Even "Sell Me Your Coat" sounds cheerful though the poor guy is freezing to death. David will always be one of rock's greatest songwriters and lyricists and David Bowie has its fair share of hilarious stories of maids, transvestites, models in adverts, megalomaniacs, childhood fantasists and psychotic gravediggers. Not essential listening for 60's psychedelic enthusiasts but more for Bowie completists. In 1967 a 20-year-old genius was obviously having a blast giving commentary on both Mod London and Twentieth-Century England in general.

It's quite easy, and seemingly the accepted wisdom, to disregard the album, even pretend it doesn’t exist, yet there is an obvious fondness for narratives and character sketches that will blossom in years to come and define Bowie's ever-shifting persona. Not exactly where one should start with Bowie, his debut album catches him with one foot in the past and one in the future. On the one hand, you have songs in an old-fashioned “easy listening” style with interesting, off-beat lyrics, and on the other you have tracks tied in with the trends of the day - whether the mild psych of "Join the Gang" or the orchestral-trippy "Silly Boy Blue" - with stilted, cliched lyrics.

It's quite easy, and seemingly the accepted wisdom, to disregard the album, even pretend it doesn’t exist, yet there is an obvious fondness for narratives and character sketches that will blossom in years to come and define Bowie's ever-shifting persona. Not exactly where one should start with Bowie, his debut album catches him with one foot in the past and one in the future. On the one hand, you have songs in an old-fashioned “easy listening” style with interesting, off-beat lyrics, and on the other you have tracks tied in with the trends of the day - whether the mild psych of "Join the Gang" or the orchestral-trippy "Silly Boy Blue" - with stilted, cliched lyrics.David Bowie is s a pleasant enough listen; other favorites are probably the cross-dressing rock story "She's Got Medals" or the nostalgia-inducing "There Is a Happy Land" (though the latter's a guilty pleasure, considering how sappy it is), not to mention the gloomy poetry of "Please, Mr Gravedigger." It's just that Bowie's still trying to work out who he is and what he wants to do. His recording track record is similar to that of his extensive touring.

Most of us will begin our journey with Bowie on Space Oddity, where the alien truly finds his voice but also reveals his chameleon-like nature, one that next would explore early heavy metal with The Man Who Sold the World. Years after his debut release, when Bowie became Ziggy and ruled the world, he may have been a bit embarrassed by this record. However, fans of folky, campy rock will enjoy, if only once.

September 29, 2020

Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow, Creeps in this petty pace from day to day...

...And so it was for rock 'n' roll in the mid-60s: malingering, strolling casually down Tin Pan Alley. In '65 we'd gone wild with Freddie and the Dreamers and Herman's Hermits (let your freak flag fly!), and then, bam, like a supernova, a bi-polar onslaught of MC5 and Moby Grape, of 13th Floor Elevators and Zombies. Out of this schizoid cavalcade came King Crimson like lab-quality LSD25, and despite the advent of metal and psychedelia, the critics were left to ponder, "Where the fuck did that come from?"

...And so it was for rock 'n' roll in the mid-60s: malingering, strolling casually down Tin Pan Alley. In '65 we'd gone wild with Freddie and the Dreamers and Herman's Hermits (let your freak flag fly!), and then, bam, like a supernova, a bi-polar onslaught of MC5 and Moby Grape, of 13th Floor Elevators and Zombies. Out of this schizoid cavalcade came King Crimson like lab-quality LSD25, and despite the advent of metal and psychedelia, the critics were left to ponder, "Where the fuck did that come from?" King Crimson formed in 1968 with former band members of Giles, Giles and Fripp: Robert Fripp (guitar), Michael Giles (drums) and Peter Giles (bass), plus Greg Lake (vocals), Ian McDonald (winds, vibes) and Pete Sinfield (lyrics and light show). From its formative years in Bournemouth, England, King Crimson's guiding force has constantly been Fripp who attributes the band's longevity to the "collective brilliance of its individual members." Fripp bfirst picked up the guitar at the age of eleven. By 18 he was playing bar-mitzvahs and weddings with a band in Bournemouth. While early influences included Bartok and Debussy and Django Reinhardt and Hendrix, Fripp was particularly drawn to The Beatles' "A Day In The Life," which he claimed affected him in the same manner as classical compositions and free form jazz. The Cheerful Insanity of Giles Giles & Fripp was released on Deram Records in September 1968. Despite the humorous folky musings and jazzy guitar riffs by Fripp, sales were dismal. It was then that Fripp and the Giles brothers evolved into King Crimson; playing their first gig at London's Speakeasy in April '69. The following week the band began a three month Sunday residency at the Marquee Club, overwhelming London's already avant-garde music scene with an impressive mix of rock, jazz and classical music. The acid test was Crimson's performance at The Rolling Stones' free concert in Hyde Park in front of half a million of London's hippest folks. KC's impact was immeasurable, with Jimi Hendrix shaking Fripp's hand and heavy hitting record companies vying for contracts, with Island Records in the UK and Atlantic in North America emerging as victors.

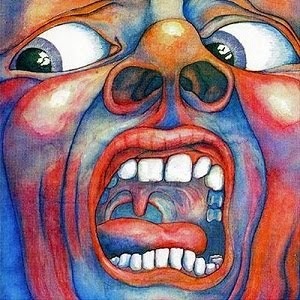

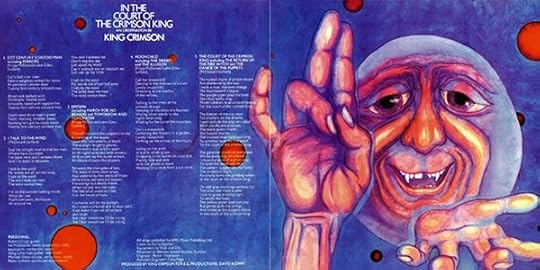

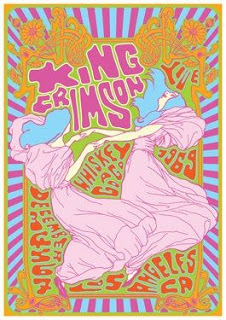

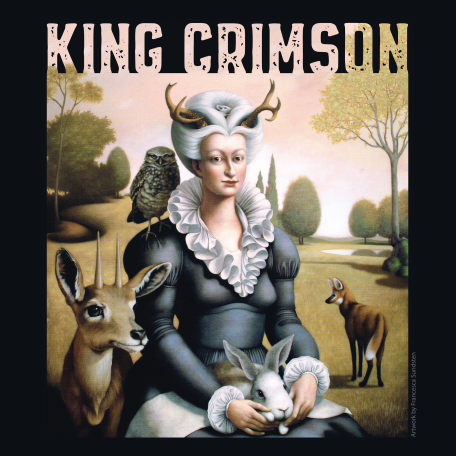

King Crimson's legendary debut album, In the Court of the Crimson King, remains the most influential progressive album in rock history and one of the most innovative and creative works ever recorded. Pete Townsend of The Who described it as an "uncanny masterpiece." Adorned with ominous neo-gothic gatefold artwork by Barry Godber, a friend of Pete Sinfield's, it would become one of the most recognizable LP covers. Tragically Godber would die of a heart attack in February of 1970 at the age of 24. The music, with its portentous lyrics, spacious Mellotron passages and futuristic angular guitar lines had a dark, orchestral sound. Tranquil ethereal atmospheres with baroque touches were interspersed with dramatic crescendos and psychotic be-bop, particularly on opening track, "21st Century Schizoid Man," highlighting the band's musical prowess. The piece would become the band's trademark over the next few years and conjured up enough doom, gloom and confusion to rival any prototypical metal band of the day. In November 1969, In The Court Of The Crimson King hit number 5 in the UK and the band embarked on a tour of the United States to support its release on Atlantic Records. The 20 gig tour opened at Goddard College in Vermont and included Boston, Detroit, New York, Palm Beach, a sold out five night stint at the Whiskey-a-Go-Go and three nights at the Fillmore.

In the Court of the Crimson King

(AM9)

In the Court of the Crimson King

(AM9) Artist: King Crimson

Producer: KC

Length: 43:53

Released: October 10, 1969

Tracks: 1) 21st Century Schizoid Man (7:24) 2) I Talk to the Wind (6:04) 3) Epitaph (8:49); 4) Moonchild (12:13) 5) The Court of the Crimson King (9:26)

Personnel: Bass, Lead Vocals – Greg Lake; Drums, Percussion, Vocals – Michael Giles; Guitar – Robert Fripp; Keyboards, Mellotron, Woodwind, Vibraphone, Reeds – Ian McDonald; Lyrics, Other [Illumination] – Peter Sinfield

In the Court of the Crimson King is powerfully dark, unwaveringly ambitious, and fearlessly experimental. The much-maligned Mellotron was never utilized as deftly before or since, nor have tender balladry, symphonic dirge and ferocious jazz-metal worked so well together on any other album. The overwhelming power of "21st Century Schizoid Man" took 1969 by surprise, and its instrumental ferocity, compositional obliquity and KC’s stunning musical chops – Fripp's roaring guitar, McDonald's piercing sax, Giles' drum demolishment and Lake's unsubmissive bass and ghostly vocals – are still capable of making 1st time listeners drool, or they should. It's kind of like reading Shakespeare, you get revelation after revelation: "Wow, that's where it first came from." In the Court of the Crimson King takes every stereotype and joke about prog rock and confounds, defies, and destroys them. Doesn't rock hard enough? Bollocks. Aimless? If only all rock albums were this focused. Too pretentious? That's pretty much this album's greatest strength - without that pretention and ambition, it wouldn't have been such a seismic release. In the Court of the Crimson King owns its hefty reputation because it's brilliant. It's a-okay here to be Catherine Obvious; it's honestly as simple as that. "Epitaph" is one of man's greatest musical achievements (maybe that's the booze talking). Still, based on its feet-wet experimentation and an inability to edit itself, the Crimson King is but an AM9.

Live at the Whiskey-a-Go-GoDespite the enthusiastic reception the band received in America, Michael Giles and Ian McDonald quit the band citing the rigors of touring and Fripp's heavy-handedness. This development left the future of King Crimson in doubt amidst rumors that Fripp was going to replace Peter Banks in Yes. Greg Lake also had reservations and had discussed the possibility of forming a band with Keith Emerson (the two met backstage at the Fillmore in San Francisco). Nonetheless, Lake stayed aboard long enough for the 2nd outing. Over the next few months other musicians were recruited as "guests," most notably jazz pianist, Keith Tippett and session man, Mel Collins, on woodwinds, with Peter Giles returning to lay down bass. In March 1970 a crazed, left of center single was released entitled "Cat Food," on which Tippett's jazz finagling combined with Lake's evocative vocals culling one of the most extreme singles ever to hit the airwaves. In The Wake Of Poseidon followed in May sounding notoriously like its predecessor with neo-classical styling, sweeping Mellotrons (now formidably handled by Fripp) as well as a "21st Century Schizoid Man" doppelganger, "Pictures Of A City."

Live at the Whiskey-a-Go-GoDespite the enthusiastic reception the band received in America, Michael Giles and Ian McDonald quit the band citing the rigors of touring and Fripp's heavy-handedness. This development left the future of King Crimson in doubt amidst rumors that Fripp was going to replace Peter Banks in Yes. Greg Lake also had reservations and had discussed the possibility of forming a band with Keith Emerson (the two met backstage at the Fillmore in San Francisco). Nonetheless, Lake stayed aboard long enough for the 2nd outing. Over the next few months other musicians were recruited as "guests," most notably jazz pianist, Keith Tippett and session man, Mel Collins, on woodwinds, with Peter Giles returning to lay down bass. In March 1970 a crazed, left of center single was released entitled "Cat Food," on which Tippett's jazz finagling combined with Lake's evocative vocals culling one of the most extreme singles ever to hit the airwaves. In The Wake Of Poseidon followed in May sounding notoriously like its predecessor with neo-classical styling, sweeping Mellotrons (now formidably handled by Fripp) as well as a "21st Century Schizoid Man" doppelganger, "Pictures Of A City." In the Wake of Poseidon

(AM8)

In the Wake of Poseidon

(AM8) Artist: King Crimson

Producer: Fripp, Sinfield

Length: 41:02

Released: May 15, 1970

Tracks: 1) Peace, A Beginning (:51) 2) Pictures of a City (7:57) 3) Cadence and Cascade (4:35); 4) In the Wake of Poseidon (8:24) 5) Peace, A Theme (1:15) 6) Cat Food (4:52) 7) The Devil's Triangle (11:30); 8) Peace, An End (1:54)

Personnel: Lead Vocals (except 3) - Greg Lake; Drums, Percussion, Vocals - Michael Giles; Guitar, Celesta, Mellotron - Robert Fripp; Woodwinds, Flute - Mel Collins; Words, Production - Pete Sinfield; Bass - Peter Giles; Piano - Keith Tippet

On a personal note, if I'd heard In the Court of the Crimson King before In the Wake of Poseidon, who knows what would have been the outcome? Here the AM rubric fails a bit. This was exciting stuff; certainly it was exciting to me. It was '74 by the time I'd picked up KC, thoroughly immersed in Yes and Tull, and singing like Jon Anderson in a high school band. But Poseidon raised the bar. In retrospect there's an obvious link between the first two Crimson albums, the first serving as template; however, Fripp & Co. set out to make an even more advanced album in the second round, despite the break-up of the band; Poseidon shouldn't even have happened.

On a personal note, if I'd heard In the Court of the Crimson King before In the Wake of Poseidon, who knows what would have been the outcome? Here the AM rubric fails a bit. This was exciting stuff; certainly it was exciting to me. It was '74 by the time I'd picked up KC, thoroughly immersed in Yes and Tull, and singing like Jon Anderson in a high school band. But Poseidon raised the bar. In retrospect there's an obvious link between the first two Crimson albums, the first serving as template; however, Fripp & Co. set out to make an even more advanced album in the second round, despite the break-up of the band; Poseidon shouldn't even have happened. The opening, "Peace - A Beginning," has Lake in an enigmatic cavern, chanting an ethereal pastiche. "Pictures of a City" crashes in like thinking man's metal with medieval nodes and a jazz structure far more sophisticated than anything on Court. The piece does indeed bear a strong relation to "21st Century Schizoid Man," but a clone? No way. Nothing as complex and demanding as this could be seen as part of a formula. "Cadence & Cascade" as "I Talk to the Wind 2.0?" Again, nearly, yet more sophisticated. This is an adult ballad, a summery-yet-melancholy love-song. Beautiful. The title track has echoes of "Epitaph" but its lyrical cleverness lends it credibility. The rest of the album holds its own, moves on, exemplifies: "Peace (A Theme)" shows just how good Fripp was as an acoustic minstrel; the hilarious and jazzy "Cat Food" is "Moonchild" plus; and "Peace (An End)" wraps it up in emotive style. "Peace is the end, like death of the war" - lump in throat time. Advice: listen to Wake as if Court didn't exist. It's the better of the two and yet an AM8 (the rubric and the rules to blame).

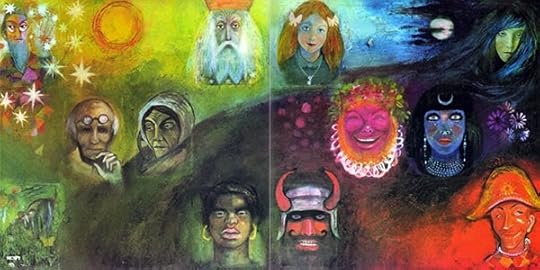

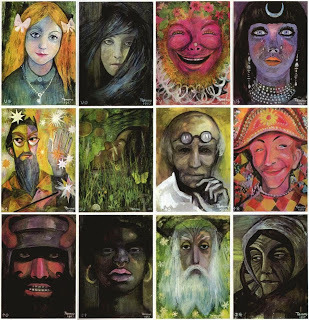

The composite above reflects the 12 Faces of Humankind (from left to right): The Child (Water and Air): A picture of innocence; a girl with a delicate sweet smile and butterfly-shaped bows at each side in her long golden hair. She wears a gold chain, on the end of which is a small golden key. The Enchantress (Water and Earth): A sad girl with watery eyes; The Fool (Fire and Water): A laughing man with a wispy beard. The Actress (Water and Fire): An Egyptian girl with long pearl earrings and many pearl necklaces around her neck, she has tears in her eyes; The Logician (Air and Fire): A scientist or wizard with a long face, dark hair and long dark holding a wand with his right hand and his left is held aloft and surrounded by stars. Mother Nature (Earth and Water): Lying asleep in the long grass; The Observer (Air and Earth): A scientist with round spectacles pushed up above his brow; The Joker (Fire and Air): A smiling twinkle-eyed Harlequin with his typical gold motley crew. The Warrior (Fire and Earth): A dark and powerful warrior in blacks and reds; The Slave (Earth and Fire): An African woman with large gold earrings and a ring through her nose, her expression is warm and friendly; The Patriarch (Air and Water): An old philosopher, with a long face and long white hair and long white beard; The Old Woman (Earth and Air): A woman with much wrinkled face wrapped up against the cold.

September 28, 2020

Fracture – King Crimson

Call it 1974, I was at Crane's Records in Van Nuys. I’d bought Court and Spark there, my first Joni album (and still my favorite). The guy behind the counter was like my Merlyn, always allowing me to choose but guiding me to something new. I was pondering Eno’s Here Come the Warm Jets, but "the guy" said, "Maybe it's time to move on." I didn't know that I was to embark on the most difficult musical journey a listener could imagine: Starless and Bible Black. I was already familiar with King Crimson; the Crimson King album cover scared the bejeebers out of me – I had virtually no bejeebers.I was already a prog kid who appreciated the complexities of Gentle Giant and Genesis and Caravan, but this was something else. I go on and on these days about musicianship and theory and the objective ways in which a musician can be rated, but I had no idea. Starless and Bible Black was KC's most stripped-down iteration with Fripp, of course, on guitar, the jazz stylings of Bill Bruford on drums, John Wetton on vocals and bass and David Cross rounding up the line up with keys and strings. Bruford was simply amazing; Cross was a nice string counterpoint to Fripp’s guitar and Wetton was the consummate musician, like Ringo, who knew how he fitted. I only missed Greg Lake's vocals, those these were better served in ELP where they were appreciated. The record store guy, who knew how much of a fan I was of Steve Howe in Yes, said, "You let me know what you think about Howe, when you hear 'Fracture,'" the Fripp instrumental that closes Side 2. Fripp called it "Impossible." Its complexities purposefully created so that he had something to work towards, a high-water mark that he hadn’t really reached at that point. There’s a guy on YouTube who practiced 22 years to be able to play the piece and then gave himself a B-; it’s that intricate and dense. So, it's been 46 years now since my first exposure and while I navigate more readily to Crimson King and Poseidon, it's Starless and Bible Black and "Fracture" that opened my eyes that music, like literature and painting, could be difficult and frustrating, that it took work and effort. The version provided is from the studio LP, but check out the live versions on YouTube to see just how compelling the piece can be.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZaD7gk7BTwU

September 23, 2020

The Beat Goes On

In 4th grade, a salesman came to our door, Apt. 22 on Hazelhurst Avenue in North Hollywood, California. He carried a small case, inside of which was an accordion. He sat me down on the couch and asked me to play, showing me the oom-pah-pah of the left hand and maneuvering my right hand to play "Down in the Valley." My mother, instantly buying in, insisted that lessons were a great idea and that the accordion was the way to go. "After all," she said, "When you grow up you'll be able to take it to parties." Who knew that the accordion would one day take on the cool vibe (think Beirut and Fleet Foxes). I did not evolve into a musician, opting instead for music as a pass-time, a passion, a constant companion, an obsession; over time, though, I've gained a working knowledge of music theory and the few remaining brain cells I nurture tend to ponder the oddities and eccentricities of modern music. Maybe I owe that to the accordion.

In 4th grade, a salesman came to our door, Apt. 22 on Hazelhurst Avenue in North Hollywood, California. He carried a small case, inside of which was an accordion. He sat me down on the couch and asked me to play, showing me the oom-pah-pah of the left hand and maneuvering my right hand to play "Down in the Valley." My mother, instantly buying in, insisted that lessons were a great idea and that the accordion was the way to go. "After all," she said, "When you grow up you'll be able to take it to parties." Who knew that the accordion would one day take on the cool vibe (think Beirut and Fleet Foxes). I did not evolve into a musician, opting instead for music as a pass-time, a passion, a constant companion, an obsession; over time, though, I've gained a working knowledge of music theory and the few remaining brain cells I nurture tend to ponder the oddities and eccentricities of modern music. Maybe I owe that to the accordion. One such oddity is the one chord song. Despite my lack of musicianship, I do know my scales and chords on the Gibson acoustic I acquired from my stepfather, and can think back to being able to play "Horse With No Name," the first week I picked it up. Just two chords there: Em and D6/9. America's first hit was a masterpiece of laziness (this may have also inspired the insistence by many that the song was about heroin use). Lou Reed has said that, "One chord is fine. Two chords is pushing it. Three chords and you're into jazz."

One such oddity is the one chord song. Despite my lack of musicianship, I do know my scales and chords on the Gibson acoustic I acquired from my stepfather, and can think back to being able to play "Horse With No Name," the first week I picked it up. Just two chords there: Em and D6/9. America's first hit was a masterpiece of laziness (this may have also inspired the insistence by many that the song was about heroin use). Lou Reed has said that, "One chord is fine. Two chords is pushing it. Three chords and you're into jazz."But lacking harmonic variety, successful one-chord songs are forced to place their emphasis on the groove of the song, the notes and rhythm of the melody, the lyric, and the performance. There are a lot of songs that I'd arguably call almost one-chord songs: The Who’s "Magic Bus," Talking Heads' "Once In A Lifetime," Creedence Clearwater Revival's "Born On The Bayou" and The Beatles' "Tomorrow Never Knows." I'd argue that these, in various different ways, introduce enough of the tonality of a second chord to fall outside the category. Even the Brazilian classic, Antonio Carlos Jobim's "One Note Samba" has a chord change. In rock history, there aren't many songs that truly stick to one chord, but the good ones are strong. There's a long tradition of one-chord blues songs, from Willie Dixon's "Spoonful" to "I'm A Man" by Muddy Waters. A lot of even earlier country blues songs have only one chord, the one that comes to mind is Porkchop Willie's "Too Many Cuts."

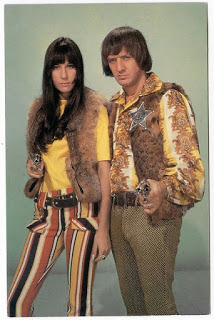

Cole PorterThere are some pretty classic one-chord R&B songs as well, such as Aretha Franklin’s "Chain Of Fools" and Wilson Pickett's "Land Of A Thousand Dances," and the occasional Pop song, like The Guess Who's "American Woman" or Sonny & Cher's "The Beat Goes On" (by Sonny Bono – based on Donovan’s "The Trip"). (I challenge you not to hum the bass line.)

Cole PorterThere are some pretty classic one-chord R&B songs as well, such as Aretha Franklin’s "Chain Of Fools" and Wilson Pickett's "Land Of A Thousand Dances," and the occasional Pop song, like The Guess Who's "American Woman" or Sonny & Cher's "The Beat Goes On" (by Sonny Bono – based on Donovan’s "The Trip"). (I challenge you not to hum the bass line.)One chord songs, of course, have something in common, simplicity. Simplicity, often in the form of repetition, is a cornerstone of songwriting, both musically and lyrically (no one ever leaves a Broadway show humming the verse). You probably don't know all the words to "While My Guitar Gently Weeps," but I'll bet you know them to "Why Don't We Do it In the Road." As a teacher, not often willfully, I'm exposed to a plethora of music, most modern pop just making me sad. Today, though, in the hallway, some kids were playing Kendrick Lamar and I was struck once again with the intricacies and complexity of the production, the nuances and the inaccessibility. While ultimately sophisticated, it reeked of the same over-the-top self-indulgence that brought down late era prog - taking itself way to seriously; as if like HDTV, 1080 pixel per square inch isn't enough, so we have to have Hi Def Hi Def, making the world super real or something. In this vein, Lamar hoped to fit in every possible chord the human ear can bear.

Big Yes fan, btw, and love the complexities of Bach's inventions, but really, I lean toward Reed's sentiments: rock 'n' roll is about sex and simplicity, as is the tradition of popular music. In Plato’s Republic, he stated that "the introduction of a new kind of music can alter the character of a nation." Indeed, the modern assault upon traditional American moral values begins with the permissiveness of the Roaring 20s (just look at the lyrics of the popular 1921 song "Sheik of Araby"). In 1934, the bisexual Cole Porter (frivolous outing) introduced a popular musical and song by the title Anything Goes, an intense shift away from restrictive codes of conduct. And in 1936, Irving Berlin composed the music and lyrics for the motion picture Follow the Fleet, starring Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers, in which Rogers sings, "Let Yourself Go." In the same film, Harriet Hilliard (Ozzie and Harriet's Harriet) sang a song with the following lyrics: "Get thee behind me, Satan,/ But the moon is low and I can't say 'no.'/ Someone I’m mad about is waiting in the night for me,/ Someone that I mustn’t see./ Satan, he's at my gate. Get thee behind me./ Stay where you are. It’s too late.” The message is clear – resistance to temptation is futile. Now that's rock 'n' roll: one chord and doin' it in the road. Thanks, Sonny & Cher; thanks, Irving Berlin.

Hendrix and Audiation

There is no record of Hendrix rehearsing in the studio, but if there were, what an event it would be. There are musicians, of course, Steve Howe of Yes comes to mind, who are classically trained, who read and are able to transcribe music and have the theory to understand the complexities of what they do. Then there are people like Hendrix (and McCartney who, without the ability to read music, has composed symphonies). We know that Hendrix loved the studio because it enabled him to record long, complex tracks like "1983… (A Merman I Should Turn to Be)" in separate sessions and edit them together—this was done of necessity because the only three musicians on the track are Hendrix, Mitch Mitchell and Chris Wood of Traffic on flute. In order for him to be able to maintain control over such a long, structured track, Hendrix must have heard the different parts in his head with great clarity. This is known in music theory as audiation. When you compose music, you are constantly audiating - your "inner ear" "hears" something, you write it down, you check it, and if it matches, you move on. If it doesn't, then you modify your understanding of what it is you're hearing until you are.

There is no record of Hendrix rehearsing in the studio, but if there were, what an event it would be. There are musicians, of course, Steve Howe of Yes comes to mind, who are classically trained, who read and are able to transcribe music and have the theory to understand the complexities of what they do. Then there are people like Hendrix (and McCartney who, without the ability to read music, has composed symphonies). We know that Hendrix loved the studio because it enabled him to record long, complex tracks like "1983… (A Merman I Should Turn to Be)" in separate sessions and edit them together—this was done of necessity because the only three musicians on the track are Hendrix, Mitch Mitchell and Chris Wood of Traffic on flute. In order for him to be able to maintain control over such a long, structured track, Hendrix must have heard the different parts in his head with great clarity. This is known in music theory as audiation. When you compose music, you are constantly audiating - your "inner ear" "hears" something, you write it down, you check it, and if it matches, you move on. If it doesn't, then you modify your understanding of what it is you're hearing until you are.By contrast, musicians with poor audiation tend to have problems creating music, unless there's someone in the room who can do it for them, namely a gifted producer. The most infamous example goes back again to Hendrix: one of his concert-stoppers early in his career was "Wild Thing," a song that was originally a hit for the English band the Troggs. The Troggs, it's fair to say, were not audiators. As long as they had producer Larry Page to direct them, they were able to make songs of classic simplicity like "Wild Thing" (which they didn't write), "With A Girl Like You" and "Love Is All Around" (which they did), but when they neglected to invite Page along, they found themselves struggling to agree on what exactly they ought to be doing. The result was captured by their engineers one night in the legendary Troggs Tape, a recording of them arguing in the studio. It wasn't a case of alpha musicians bickering over a sound or an arrangement, it was a studio ball of confusion. It's an interesting listen if you have time on your hands, and often hilarious. The point is this: had their usual producer been in the room, he would have been able to suggest a direction that the band would have gone with. In his absence, it's clear that nobody has a coherent idea of what the track ought to sound like.

Audiation is not a substitute for scoring. There are levels of detail that you can't just hum to other people. Had Hendrix lived, I suspect he might have learned to write music because his ideas were becoming more and more complex and the people he wanted to play with were at a level that he would have needed some study to keep up with them. It's the kind of thing that haunted Lennon. He had the audiation, but couldn't express it, often not even to George Martin. Aside from Hendrix and The Beatles, other musicians who have no formal training in music but were blessed instead with an innate ability to hear the music in their heads (audiation in its truest form) include Dave Grohl, Robert Johnson, Eddie Van Halen, Michael Jackson, Eric Clapton and Elvis. Pretty good trick.

When Push Shoves… Let’s Do Some MUSIC THEORY (Simplified)

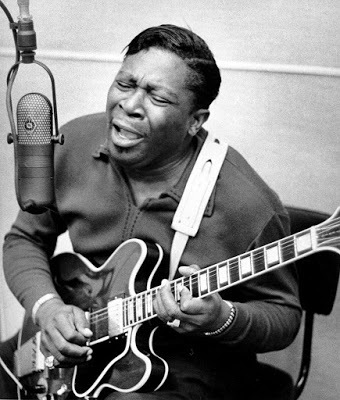

When I started AM five years ago, the intent was the "Absolute Magnitude" (AM) of an LP – an objective rubric of an album's "greatness." That, of course, remains impossible – at least to a degree. The network has more appropriately switched its attention to what is objective: music history.But Facebook insists on its apple and orange comparisons. The most recent I witnessed was on a jazz site in which the "analysis" was the greatest bassist. Hundreds of followers commented, argued and reasoned, some volatilely - yikes.YouTube, as well, is chock full of these comparisons. The Point: when push shoves, "greatest" is subjective and unmeasurable. But wait! Is there a way to apply the AM rubric? There is, but many won't like it, particularly those whose rock heroes are "shredders" (usually metal), who insist that a guitarist is "best" because of the speed or dexterity with which he or she plays. Hands down, that is incorrect.Here's the theory: Great musicianship comes with essential and non-essential elements. The Essentials: Rhythm, Harmony, Melody – Sounds obvious, no? "Music" is defined by these three elements. Rhythm: Without this guy, it's not music. Great musicians, classical, rock, otherwise, have rhythm or learn it. Great musicians have practiced endlessly with a metronome. In a band, that metronome is replaced by the drummer (keeping this simple). Speed and dexterity (non-essentials) play no role and matter not without rhythm. (So, yes, you can eliminate many a lightning-fast shredder straight off.) Melody: Since we already know what melody is, here's a more technical definition: Melody is a collection of musical tones grouped together as a single entity. Compositions consist of multiple melodies working in conjunction with one another. In a rock band, the vocalist, guitarist, keyboardist, and bassist are all playing melodies on their respective instruments. Even the drummer is playing one (in addition to keeping rhythm). Melody consists of two primary components: Pitch, which refers to the audio vibration produced by an instrument arranged as a series of notes with names like C4 or D#5; and Duration, the length of time each pitch sounds. These durations are divided into lengths such as whole notes, half notes, quarter-note triplets, and more. This one is obvious: without melody, again, it's not music.Harmony: Yes, the kind you're thinking (Beach Boys, CSN), but no, not the kind you're thinking. Melodies are not just played alone by a solo instrument or a group of instruments playing the same thing. Very frequently there are 'lead' instruments which play melodies (such as the voice, wind instruments, etc.) and, at the same time, others that accompany them doing something else. This relationship between different notes played at the same time is called harmony. Oh yeah, and without it, it's not music.If you have these three elements, you have MUSIC by definition. Hence, the composer utilizes the tools of composition for the intimacies of musical expression – melody, harmony and rhythm – all a part of what we know simply as a "song."But we can, indeed, add to that the "non-essentials": dexterity, speed and strength. The great (note I didn’t say greatest) blues guitarist, B.B. King, was still performing at 89 years old. Watch him on YouTube, knock your socks off. He lacked, dexterity in those years, speed as well, but 70 years of practice and play left him with the strength to perfectly execute “stretched” chords and to execute each chord. And note that some of the greatest guitar players like David Gilmour and Larry Carlton rarely (if ever in Gilmour's case), rely on speed. They succinctly land the essentials and then add on dexterity and strength.The point is, forget all those apple/orange comparisons or participate because it's fun – first and foremost, music is about appreciation. If you appreciate music, though, put your “greatests” to the test. Is it just shredding at lightning speed that you appreciate (on YouTube it seems to be the fastest "Flight of the Bumblebee" that gets the accolades)? If so, you probably think that those who participate in hot dog eating contests are gourmands.

When I started AM five years ago, the intent was the "Absolute Magnitude" (AM) of an LP – an objective rubric of an album's "greatness." That, of course, remains impossible – at least to a degree. The network has more appropriately switched its attention to what is objective: music history.But Facebook insists on its apple and orange comparisons. The most recent I witnessed was on a jazz site in which the "analysis" was the greatest bassist. Hundreds of followers commented, argued and reasoned, some volatilely - yikes.YouTube, as well, is chock full of these comparisons. The Point: when push shoves, "greatest" is subjective and unmeasurable. But wait! Is there a way to apply the AM rubric? There is, but many won't like it, particularly those whose rock heroes are "shredders" (usually metal), who insist that a guitarist is "best" because of the speed or dexterity with which he or she plays. Hands down, that is incorrect.Here's the theory: Great musicianship comes with essential and non-essential elements. The Essentials: Rhythm, Harmony, Melody – Sounds obvious, no? "Music" is defined by these three elements. Rhythm: Without this guy, it's not music. Great musicians, classical, rock, otherwise, have rhythm or learn it. Great musicians have practiced endlessly with a metronome. In a band, that metronome is replaced by the drummer (keeping this simple). Speed and dexterity (non-essentials) play no role and matter not without rhythm. (So, yes, you can eliminate many a lightning-fast shredder straight off.) Melody: Since we already know what melody is, here's a more technical definition: Melody is a collection of musical tones grouped together as a single entity. Compositions consist of multiple melodies working in conjunction with one another. In a rock band, the vocalist, guitarist, keyboardist, and bassist are all playing melodies on their respective instruments. Even the drummer is playing one (in addition to keeping rhythm). Melody consists of two primary components: Pitch, which refers to the audio vibration produced by an instrument arranged as a series of notes with names like C4 or D#5; and Duration, the length of time each pitch sounds. These durations are divided into lengths such as whole notes, half notes, quarter-note triplets, and more. This one is obvious: without melody, again, it's not music.Harmony: Yes, the kind you're thinking (Beach Boys, CSN), but no, not the kind you're thinking. Melodies are not just played alone by a solo instrument or a group of instruments playing the same thing. Very frequently there are 'lead' instruments which play melodies (such as the voice, wind instruments, etc.) and, at the same time, others that accompany them doing something else. This relationship between different notes played at the same time is called harmony. Oh yeah, and without it, it's not music.If you have these three elements, you have MUSIC by definition. Hence, the composer utilizes the tools of composition for the intimacies of musical expression – melody, harmony and rhythm – all a part of what we know simply as a "song."But we can, indeed, add to that the "non-essentials": dexterity, speed and strength. The great (note I didn’t say greatest) blues guitarist, B.B. King, was still performing at 89 years old. Watch him on YouTube, knock your socks off. He lacked, dexterity in those years, speed as well, but 70 years of practice and play left him with the strength to perfectly execute “stretched” chords and to execute each chord. And note that some of the greatest guitar players like David Gilmour and Larry Carlton rarely (if ever in Gilmour's case), rely on speed. They succinctly land the essentials and then add on dexterity and strength.The point is, forget all those apple/orange comparisons or participate because it's fun – first and foremost, music is about appreciation. If you appreciate music, though, put your “greatests” to the test. Is it just shredding at lightning speed that you appreciate (on YouTube it seems to be the fastest "Flight of the Bumblebee" that gets the accolades)? If so, you probably think that those who participate in hot dog eating contests are gourmands.

September 21, 2020

Listening Booth - LPs for Isolation

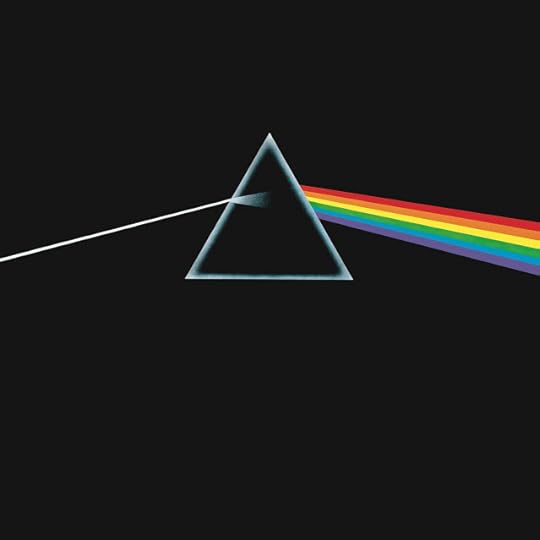

Over the years, particularly in the digital age, we've lost that sense of active listening. There's less time these days to sit there and meditate on the entirety of an LP. As magnificent as it is, we've parted out Dark Side of the Moon, as if we were following the instructions from "One of These Days:" "One of these days I’m going to cut you into little pieces."

Over the years, particularly in the digital age, we've lost that sense of active listening. There's less time these days to sit there and meditate on the entirety of an LP. As magnificent as it is, we've parted out Dark Side of the Moon, as if we were following the instructions from "One of These Days:" "One of these days I’m going to cut you into little pieces."Over the pasts six months, many of us have the time again, and rather than tearing our hair out, here are some albums that approach the brilliance of DSOTM, albums well worth devoting 40 minutes of uninterrupted time.

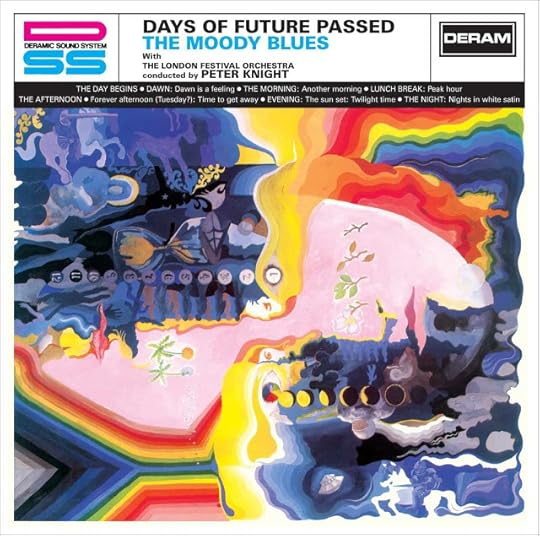

Moody Blues, Days of Future Passed. Commissioned to record a stereophonic rock 'n' roll version of Dvorak's New World Symphony for the new "stereo" label, Deram, the Moodies were given a top-notch producer (Tony Clarke), a full orchestra, and conductor/arranger Peter Knight. Though initial sessions went well, there was little heart in the project. With an orchestra on hand, the band were able to convince Clarke and Knight to record the group's own songs. Though Decca was initially appalled that the band would be brash enough to hijack the project, they let it go through. The result was Days of Future Passed. It was an album overshadowed by the heavy hitters that year, from Sgt. Pepper and Magical Mystery Tour to The Velvet Underground and Nico, Days stands up to this day.

Radiohead, Kid A. Those who know me know that I don’t have much regard for the 90s musically. Not that there weren’t great LPs, just not many of them. So when Kid A appeared in 2000, I was thrilled, if not overwhelmed. Was it as good at Dark Side? That part was a little frightening. Of all things, it's Neil Young, particularly with After the Gold Rush, who is Thom York's biggest influence. One of Neil's "tricks," like Bowie's, is to start afresh with each LP – which for Neil has led to a lot of subpar recordings, but that’s what York did with Kid-A, abandoning the guitar-oriented splendor of the first LPs for PF-like synths. Kid A is that good: it deserves its place alongside Dark Side of the Moon.

While King Crimson's In the Court of the Crimson King, while still obscure to most, is the monumental LP in the band’s 50-year canon, I tend to listen to In the Wake of Poseidon a bit more. The opening, "Peace - A Beginning," has Greg Lake in an enigmatic cavern, chanting an ethereal pastiche. "Pictures of a City" crashes in like a thinking man's metal with medieval nodes and a jazz structure far more sophisticated than anything on Court. The piece does indeed bear strong relation to "21st Century Schizoid Man," but a clone? No way. Nothing as complex and demanding as this could be seen as part of a formula. "Cadence & Cascade" as "I Talk to the Wind 2.0?" Again, nearly, yet more sophisticated. This is an adult ballad, a summery-yet-melancholy love song. Beautiful. The title track has echoes of "Epitaph" but its lyrical cleverness lends it credibility. The rest of the album holds its own, moves on, exemplifies: "Peace (A Theme)" shows just how good Fripp was as an acoustic minstrel; the hilarious and jazzy "Cat Food" is "Moonchild" plus; and "Peace (An End)" wraps it up in emotive style. "Peace is the end, like death of the war" - lump in throat time. Advice: listen to Wake as if Court didn't exist.

September 20, 2020

A Quick History - Laurel Canyon

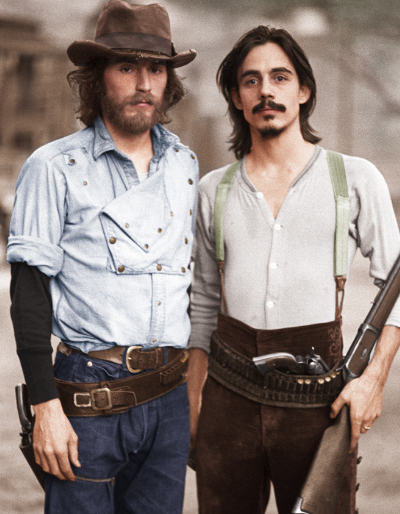

Stephen Stills and Peter TorkFrom his 2006 treatise on the L.A. music scene (Hotel California), British journalist Barney Hoskyns wrote, "In a way it's a death-of-60s-utopianism story. When you look back down the corridors of rock & roll time there aren't that many homogenous scenes that you can write about, that are like stories of dysfunctional families where there's a real coherence in what a group of artists is trying to do and say. It seemed to be crying out for an overview. Plus you have this great setting, this rural oasis right in the midst of freeway hell."

Stephen Stills and Peter TorkFrom his 2006 treatise on the L.A. music scene (Hotel California), British journalist Barney Hoskyns wrote, "In a way it's a death-of-60s-utopianism story. When you look back down the corridors of rock & roll time there aren't that many homogenous scenes that you can write about, that are like stories of dysfunctional families where there's a real coherence in what a group of artists is trying to do and say. It seemed to be crying out for an overview. Plus you have this great setting, this rural oasis right in the midst of freeway hell.""After 1968 I think there was a sense in the global music community that we needed to slow down and chill out," wrote Hoskyns. "We’ve got to get 'back to the garden,' to use Joni's phrase. And I think what Laurel Canyon represented was a place of refuge. And it happened to be right in the middle of the city. The recording studios were there, the clubs, down on the Strip. I think it was a place to stop and take stock. People had not looked inward up to that point; everyone was looking outward, usually through the prism of drugs. And now it was like, 'My god, we really need to look inside and ask ourselves some questions.'"

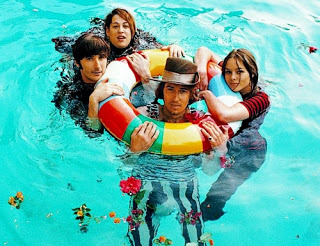

JD Souther and Jackson BrowneIn 1969, David Geffen, then a 26-year-old talent agent who managed Laura Nyro, took on Crosby, Stills & Nash. Soon he partnered with Joni Mitchell's manager Elliot Roberts; Lookout Management became Geffen-Roberts and in 1971 the multitasking Geffen launched Asylum Records with the backing of Atlantic's Ahmet Ertegun. Wrote Hoskyns, "In essence what people like David Geffen did was to market the very non-commercialism, turn that kind of laid-back, patched-denim dropout thing into a product."

JD Souther and Jackson BrowneIn 1969, David Geffen, then a 26-year-old talent agent who managed Laura Nyro, took on Crosby, Stills & Nash. Soon he partnered with Joni Mitchell's manager Elliot Roberts; Lookout Management became Geffen-Roberts and in 1971 the multitasking Geffen launched Asylum Records with the backing of Atlantic's Ahmet Ertegun. Wrote Hoskyns, "In essence what people like David Geffen did was to market the very non-commercialism, turn that kind of laid-back, patched-denim dropout thing into a product." Laurel Canyon scenesters had found a regular hangout in The Troubadour, but in 1973, the Roxy opened in direct competition. Its owners were David Geffen and Lou Adler, so naturally they had money on their minds; producers can only pretend or actualize their altruism for just so long. "The Roxy was very symbolic of a shift toward something that was more glitzy and in-crowd and movie-star oriented," said Hoskyns. “Maybe this was the dawn of the celebrity era. You think of it in terms of Cher and people like that. It certainly isn’t about banjos anymore." Hoskyns tells the story of a legendary summit in David Geffen's sauna at which he informed his guests — Glenn Frey, Don Henley, Jackson Browne and Ned Doheny — that he was starting a small record label: "I’ll never have more artists than I can fit in this sauna." Just two years later Geffen sold Asylum to Warner Bros., and then in '73 the label merged with Elektra. Geffen immediately cut Elektra's artist roster and soon he was racking up enemies almost as quickly as the zeroes in his paychecks. By the early 80s the Bronx entrepreneur's ruthless business practices had led to his falling out with Joni Mitchell, Neil Young and Henley. The times they were-a changin'.

Carole KingVoices of a generation or not, by the mid-70s some of the leading lights of the scene — including Crosby, Stills, Henley, and Frey — began, said Walker, "to behave very much like Nero on his way to the vomitorium." A string of early 70s feel-good hits like America's "Ventura Highway (AM10)," Jackson Browne’s "Doctor My Eyes," and the Eagles’ "Take It Easy" (co-written by Browne), made the Hollywood hippies easy targets. The Laurel Canyon cohort was fracturing, and there was no Yoko to blame. Frank Zappa came up with the derisive term "navel gazers" to describe his former neighbors. Tom Waits, whose song "Ol' 55" was covered by the Eagles, said the band was "about as exciting as watching paint dry." Taking those sentiments a few steps further, Lester Bangs wrote an essay entitled, "James Taylor Marked For Death," declaring, "I call it I-Rock because most of it is so relentlessly, involutedly (sic) egocentric that you finally actually stop hating the punk and just want to take the poor bastard out and get him a drink, and then kick his ass." Despite the ridiculous contrarian journalism, no one can argue the lasting evidence: Young's “Ohio” (written in Nash's backyard), or Carole King's Tapestry or Mitchell's Ladies of the Canyon, Blue and For the Roses; or later, the Eagles' canonical (if overplayed) Hotel California, which chronicles the scene's decline into nihilism. Though Hoskyns' text is more like someone weaving a story around mythologies, the language is convoluted at times (and the grammar a bit wasted, maybe), it's a stunning read with familiar characters that 40 years on still have many of us under their spell.

Carole KingVoices of a generation or not, by the mid-70s some of the leading lights of the scene — including Crosby, Stills, Henley, and Frey — began, said Walker, "to behave very much like Nero on his way to the vomitorium." A string of early 70s feel-good hits like America's "Ventura Highway (AM10)," Jackson Browne’s "Doctor My Eyes," and the Eagles’ "Take It Easy" (co-written by Browne), made the Hollywood hippies easy targets. The Laurel Canyon cohort was fracturing, and there was no Yoko to blame. Frank Zappa came up with the derisive term "navel gazers" to describe his former neighbors. Tom Waits, whose song "Ol' 55" was covered by the Eagles, said the band was "about as exciting as watching paint dry." Taking those sentiments a few steps further, Lester Bangs wrote an essay entitled, "James Taylor Marked For Death," declaring, "I call it I-Rock because most of it is so relentlessly, involutedly (sic) egocentric that you finally actually stop hating the punk and just want to take the poor bastard out and get him a drink, and then kick his ass." Despite the ridiculous contrarian journalism, no one can argue the lasting evidence: Young's “Ohio” (written in Nash's backyard), or Carole King's Tapestry or Mitchell's Ladies of the Canyon, Blue and For the Roses; or later, the Eagles' canonical (if overplayed) Hotel California, which chronicles the scene's decline into nihilism. Though Hoskyns' text is more like someone weaving a story around mythologies, the language is convoluted at times (and the grammar a bit wasted, maybe), it's a stunning read with familiar characters that 40 years on still have many of us under their spell. Mama Cass

Mama CassThe magic of the LP is that it is, truly, a record — of a mood, of a time and a place with gorgeous specimens like Crosby, Stills & Nash or Court and Spark. This was a truly magical time in the industry's history: the Brits were all about art rock moving towards progressive; the Americans found jazz in its sidestep from folk - and the end result was rock's annus mirabilis. Happening upon "Suite: Judy Blue Eyes" on the car radio, one can still feel the electric thrill of a moment that was less about dropping out than tuning in.

September 19, 2020

"There Was No Doubt Gertrude Stein Had Come Back to Life."

AM has long maintained that Cass Elliot was the Gertrude Stein of Laurel Canyon. Stein, who lived in Paris in the 6th Arrondisement at 27 rue de Fleurus, spent the informative years of her life as host, along with partner Alice B. Toklas, to the American Expatriates of the 1920s – the likes of Avant Garde photographer Man Ray, F. Scott Fitzgerald and Ernest Hemingway – and European artists alike, in particular Pablo Picasso, Luis Bunuel, Francis Picabia and Henri Matisse. If one is impressed with the ghetto of artists that populated L.A.'s Laurel Canyon in the 1960s, one would be overwhelmed by those who frequented No. 27. Essentially, Stein was mentor, editor, guru and critic, not to mention champion, of the artistic renaissance that pervaded Paris in the 1920s. Two accounts that bring Stein’s enclave into focus are her biopic, The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas (oddly titled an "autobiography" and credited to Toklas), and Hemingway's posthumously published A Moveable Feast. As well, Stein is expertly portrayed by Kathy Bates in Woody Allen's Midnight in Paris, lounging in a Queen Anne-styled chair, dressed in brown corduroy, with an entourage of the famous, or soon to be famous, hanging on her every word. It would not be unusual for Fitzgerald and Hemingway, already fully established in the writing community (Fitzgerald with Gatsby under his wing and Hemingway, having already published The Sun Also Rises, working on A Farewell to Arms), Fitzgerald stumbling on his words, Hemingway, cocksure and arrogant, telling off Juan Gris, simply because that was Hemingway's M.O.

AM has long maintained that Cass Elliot was the Gertrude Stein of Laurel Canyon. Stein, who lived in Paris in the 6th Arrondisement at 27 rue de Fleurus, spent the informative years of her life as host, along with partner Alice B. Toklas, to the American Expatriates of the 1920s – the likes of Avant Garde photographer Man Ray, F. Scott Fitzgerald and Ernest Hemingway – and European artists alike, in particular Pablo Picasso, Luis Bunuel, Francis Picabia and Henri Matisse. If one is impressed with the ghetto of artists that populated L.A.'s Laurel Canyon in the 1960s, one would be overwhelmed by those who frequented No. 27. Essentially, Stein was mentor, editor, guru and critic, not to mention champion, of the artistic renaissance that pervaded Paris in the 1920s. Two accounts that bring Stein’s enclave into focus are her biopic, The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas (oddly titled an "autobiography" and credited to Toklas), and Hemingway's posthumously published A Moveable Feast. As well, Stein is expertly portrayed by Kathy Bates in Woody Allen's Midnight in Paris, lounging in a Queen Anne-styled chair, dressed in brown corduroy, with an entourage of the famous, or soon to be famous, hanging on her every word. It would not be unusual for Fitzgerald and Hemingway, already fully established in the writing community (Fitzgerald with Gatsby under his wing and Hemingway, having already published The Sun Also Rises, working on A Farewell to Arms), Fitzgerald stumbling on his words, Hemingway, cocksure and arrogant, telling off Juan Gris, simply because that was Hemingway's M.O. As an Angelino, I drove by "Our House," the hillside home Joni Mitchell shared with Graham Nash, on a million occasions, making it a part of my tour for house guests, forever overawed – but I can't imagine walking into No. 27 to find the wall covered in Cezannes or the early works of Matisse. The constant flux of people in and out brings to mind T.S. Eliot's Prufrock: "In the room the women come and go,/ Talking of Michelangelo," but these weren't "people," these were the great minds of the 20th Century, coming and going, each hoping for an audience with Stein. In the mid-20s, the scene established itself as a more formal Salon on Saturday evenings with Alice B. Toklas acting as hostess. Stein's idea was to allow these incredible masses to entertain themselves while she holed up with her own interests. It was the perfect time for her to work on the autobiography. James R. Mellow describes a typical evening at the Saturday Salon: "Among the crowd of Hungarian painters, French intellectuals, English aristocrats and German students, one might pick out the figures of Picasso and his mistress, Fernande Olivier (Picasso looking like an intense young bootblack; Fernande, almond-eyed and attractive). The man with the reddish beard and spectacles, looking like a German professor, would be Matisse. Next to him might be the poet Guillaume Apollinaire and his clinging friend, the painter Marie Laurencin. The tall figure would be that of Georges Braque, whose superior stature among the smaller cubists made him the official hanger- of-pictures in the atelier. In the American contingent, the familiars would be the painters Patrick Henry Bruce and Alfred Maurer, both of them early advocates of the modernist vision and both, at the same time, followers of Matisse."

As an Angelino, I drove by "Our House," the hillside home Joni Mitchell shared with Graham Nash, on a million occasions, making it a part of my tour for house guests, forever overawed – but I can't imagine walking into No. 27 to find the wall covered in Cezannes or the early works of Matisse. The constant flux of people in and out brings to mind T.S. Eliot's Prufrock: "In the room the women come and go,/ Talking of Michelangelo," but these weren't "people," these were the great minds of the 20th Century, coming and going, each hoping for an audience with Stein. In the mid-20s, the scene established itself as a more formal Salon on Saturday evenings with Alice B. Toklas acting as hostess. Stein's idea was to allow these incredible masses to entertain themselves while she holed up with her own interests. It was the perfect time for her to work on the autobiography. James R. Mellow describes a typical evening at the Saturday Salon: "Among the crowd of Hungarian painters, French intellectuals, English aristocrats and German students, one might pick out the figures of Picasso and his mistress, Fernande Olivier (Picasso looking like an intense young bootblack; Fernande, almond-eyed and attractive). The man with the reddish beard and spectacles, looking like a German professor, would be Matisse. Next to him might be the poet Guillaume Apollinaire and his clinging friend, the painter Marie Laurencin. The tall figure would be that of Georges Braque, whose superior stature among the smaller cubists made him the official hanger- of-pictures in the atelier. In the American contingent, the familiars would be the painters Patrick Henry Bruce and Alfred Maurer, both of them early advocates of the modernist vision and both, at the same time, followers of Matisse." By the same token, it was Cass Elliot who shaped the 60’s behind-the-music scene. The Top Ten smash "I Saw Her Again" by The Mamas and the Papas was the first major hit of the summer of 1966. By then, the band was L.A. royalty, with their own table reserved at the Whiskey-a-Go-Go. One could go so far as to say that this was when and where the unwitting Salon of the Canyon began (unofficially Cass had overseen the same scene in Greenwich Village years before). Keep in mind that what may read as pretentious, was in no way the case. Neither Stein nor Cass Elliot orchestrated their guru-like draw; both were genuine and charming, welcoming people, regular people too, to their homes. Cass though, by all accounts, was unassuming and genuinely appreciated those who sought her attention. I would love to have created the idea of Cass Elliot as Gertrude Stein, but Graham Nash had the thought back in '67: "There was no doubt that Gertrude Stein had come back to life. She [Mama Cass] was brilliant and she loved friends and she loved to get high with all of us. She was the queen!"

By the same token, it was Cass Elliot who shaped the 60’s behind-the-music scene. The Top Ten smash "I Saw Her Again" by The Mamas and the Papas was the first major hit of the summer of 1966. By then, the band was L.A. royalty, with their own table reserved at the Whiskey-a-Go-Go. One could go so far as to say that this was when and where the unwitting Salon of the Canyon began (unofficially Cass had overseen the same scene in Greenwich Village years before). Keep in mind that what may read as pretentious, was in no way the case. Neither Stein nor Cass Elliot orchestrated their guru-like draw; both were genuine and charming, welcoming people, regular people too, to their homes. Cass though, by all accounts, was unassuming and genuinely appreciated those who sought her attention. I would love to have created the idea of Cass Elliot as Gertrude Stein, but Graham Nash had the thought back in '67: "There was no doubt that Gertrude Stein had come back to life. She [Mama Cass] was brilliant and she loved friends and she loved to get high with all of us. She was the queen!" Donovan remembers Cass from his celebrity filled L.A. debut at The Trip in 1966 as "The most vocal fan in the audience." He went on to say that he became friendly with all four members of the band, but that "Cass made this eighteen-year old boy welcome in America and she treated me like a sister in a time of overwhelming fame for me" (Donovan had become a star overnight, first with "Catch the Wind" and then with the monster hit "Sunshine Superman"). He would later immortalize his feelings for her in a stylized psychedelic homage called "Fat Angel."

Donovan remembers Cass from his celebrity filled L.A. debut at The Trip in 1966 as "The most vocal fan in the audience." He went on to say that he became friendly with all four members of the band, but that "Cass made this eighteen-year old boy welcome in America and she treated me like a sister in a time of overwhelming fame for me" (Donovan had become a star overnight, first with "Catch the Wind" and then with the monster hit "Sunshine Superman"). He would later immortalize his feelings for her in a stylized psychedelic homage called "Fat Angel."There are conflicting stories with regard to The Hollies living on Cass's floor. Guy Webster, who photographed the cover of the "Stop Stop Stop" single, said that The Hollies slept on Cass's floor because "they had no money since they hadn't any hits." Nash tells it differently (and indeed the history seems to jive with Nash’s): "Whenever you went over to Cass's house you got so bloody loaded that, sure, you ended up crashing over there. We saw the sun come up many times." Either story fits the Stein analogy: patron or party host.

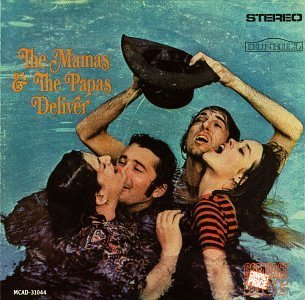

Things would change dramatically for Cass in 1966 with her pregnancy with Owen. Determined to keep the child despite the lack of support from the father, a new focus was apparent in her life. An underlying loneliness was exchanged for motherhood. The inherent difficulties transformed themselves in The Mamas and the Papas' third LP, which was, with Cass in mind, titled Deliver. On it were two new singles, the Michelle Phillips focused "This is Dedicated to the One I Love," and the autobiographical "Creeque Alley," which would become the band's third-best selling single.

Things would change dramatically for Cass in 1966 with her pregnancy with Owen. Determined to keep the child despite the lack of support from the father, a new focus was apparent in her life. An underlying loneliness was exchanged for motherhood. The inherent difficulties transformed themselves in The Mamas and the Papas' third LP, which was, with Cass in mind, titled Deliver. On it were two new singles, the Michelle Phillips focused "This is Dedicated to the One I Love," and the autobiographical "Creeque Alley," which would become the band's third-best selling single. A change in lifestyle did nothing to stall Cass's dedication to those with whom she surrounded herself. Over the next few years Cass's home remained open to the likes of The Beatles, Crosby, Stills and Nash, Jim Morrison and Frank Zappa.

Part II – Monterey – Next.