R.J. Stowell's Blog: rjsomeone, page 15

November 10, 2020

The Great L.A. Record Stores - Part 2

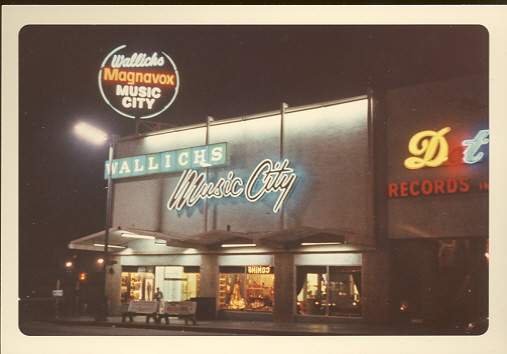

Of course, the big guns of the 60s, Sight and Sound and Wallichs Music City (spelling is correct), would evolve, if that’s the right word, into the world’s largest record store in 1971 with the opening of Tower Records on the Sunset Strip in West Hollywood. (Some of you may remember the Wallichs radio jingle: "It's Music City…") While I was more about Aron's and Vinyl Fetish by the early 80s, it was Tower in between, whether the main store or the one in Panorama City across from the Americana Theater. I even worked in the Sunset Strip store for a stint. Aspiring L.A. Actors either worked as waiters (which I did for three days at Otto's Pink Pig) or they worked at Tower.

Tower Records was the first Southern California location of the Sacramento-based chain, and the most famous. Before Tower was built, the corner had been a drive-in restaurant in the '40s, a coffee shop in the '50s, and in 1964, Earl "Madman" Muntz sold car stereos there. I mentioned in a previous post that Moby Disc was 900 square feet; Tower was 8,660.

Tower Records was the first Southern California location of the Sacramento-based chain, and the most famous. Before Tower was built, the corner had been a drive-in restaurant in the '40s, a coffee shop in the '50s, and in 1964, Earl "Madman" Muntz sold car stereos there. I mentioned in a previous post that Moby Disc was 900 square feet; Tower was 8,660. The store's lengthy aisles with rows and rows of music were crowded with an eclectic group of hippies and elites searching for the next great find. And, unlike other stores, Tower Records stayed open until midnight—and 1 a.m. on the weekends—so you could shop late. The video shows a collage of the store and includes a glimpse of Elton John. I was off that day.

The following is a true story and a passage from my first novel, Jay and the Americans, available on Amazon or at the link in the sidebar. You can read Jay for free on Kindle Unlimited.

The next day my mother said with urgency, “Gather your things, let’s go.” I didn’t know what she meant; grown-ups talk so fast. I took a Beatles trading card, and my Tony the Tiger spoon, the things one values when five. We packed the Rambler, his car, and went to the White Front on Roscoe Blvd. where I single-handedly catapulted “Glad All Over” to No. 1 on the KHJ Boss-30.

The White Front had a 45 vending machine. I wanted “In My Room,” the B side to The Beach Boys’ “Be True to Your School.” I always liked the B sides. I pushed D12, my 45¢ clattered back into the change slot and out came “Glad All Over” by the Dave Clark Five. I tried again. A quarter, two dimes, “Glad All Over.” Soon a crowd of teens and would-be hippies gathered round, my mother and I passing out “Glad All Over” like samples at See’s Candies. It was the first time I’d seen my mother smile in a long while.

I looked at toys as my mother tried on stirrup pants. We bought incidentals on a White Front credit card with my father’s name, we ate hamburgers at Beeps and drove forever into the night; the forever when you’re five. Kneeling on the back seat, gazing out the rear window, I watched as the mindless golden glow of the Valley faded to black.

Published on November 10, 2020 07:30

The Great L.A. Record Stores - Part 1

Having a family in the industry, music has been a part of my life since I can remember. My mother was a back-up singer, my father painted those famous rock billboards that lined the Sunset Strip. Obviously, it rubbed off; and today, as you may have surmised, I am the author of two (soon to be three) novels about L.A. with rock music as a character in each.

Having a family in the industry, music has been a part of my life since I can remember. My mother was a back-up singer, my father painted those famous rock billboards that lined the Sunset Strip. Obviously, it rubbed off; and today, as you may have surmised, I am the author of two (soon to be three) novels about L.A. with rock music as a character in each.Records became an obsession for me in the early 1970s. I bought my first LP, Sgt. Pepper, at the Licorice Pizza on Van Nuys Blvd. in Panorama City (1967). And my brother would take me down to Wallichs Music City in the middle of the night. We’d pick out records and take over one of the listening booths. I've recently posted about Sight and Sound in Van Nuys where I bought Richard Harris's (Dumbledore's) A Tramp Shining, with "MacArthur Park."

Across Victory Blvd., though, in the early 70s, opened Moby Disc. The store would become a small chain and my new wave years were spent at the location in Sherman Oaks across from Casa de Cadillac, but for this short series on L.A.'s record stores, it was the Moby on Victory that I remember most fondly. (Don't get me wrong, though, it was in Sherman Oaks that I first heard Elvis Costello!, Human League, and the B52s.)

The tiny 900 square foot space was the premiere store for progressive rock. It was there that I bought the progressive staples, Close to the Edge, the Yes solos, PFM, Camel, Renaissance, Aphrodite's Child, on and on.

At Wallichs at Sunset and Vine and across Victory Blvd. at The House of Sight and Sound, there were listening booths. You’d grab a handful of records and spend hours under the headphones, but there was no such thing at Moby. Immediately upon entering on the right were the new releases. Across from that, with an aisle through which two people couldn’t fit, was the cash register and it was there, crowding the front of the store, that we'd gather and crank up whatever was new. There were times that ring so clearly in my head: the first time I heard Relayer and Gentle Giant’s Octopus, or "Hocus Pocus" by Focus. That era lasted for me from 1972 or so until I no longer had to take a bus anywhere (circa 1979). Before that, it was the 93 RTD bus that stopped right there in front of Moby.

At Wallichs at Sunset and Vine and across Victory Blvd. at The House of Sight and Sound, there were listening booths. You’d grab a handful of records and spend hours under the headphones, but there was no such thing at Moby. Immediately upon entering on the right were the new releases. Across from that, with an aisle through which two people couldn’t fit, was the cash register and it was there, crowding the front of the store, that we'd gather and crank up whatever was new. There were times that ring so clearly in my head: the first time I heard Relayer and Gentle Giant’s Octopus, or "Hocus Pocus" by Focus. That era lasted for me from 1972 or so until I no longer had to take a bus anywhere (circa 1979). Before that, it was the 93 RTD bus that stopped right there in front of Moby.As the millennium kicked in, vinyl began its collapse. While it had struggled amidst the promises of digital music with the CD, the vapid world of downloading began. Digital downloads are a lonely and sterile beast, unsatisfying to the soul. Worse, because of them, the album format died an untimely death.

Because of them, stores like Aron's and Rhino shuttered their doors. And the new giants, like Amoeba in Hollywood, failed to fill the gap. Amoeba was like the Walmart of vinyl (I'll amend that to say that Amoeba today is a far more satisfying experience, but it's no Vinyl Fetish, that’s for sure).

Because of them, stores like Aron's and Rhino shuttered their doors. And the new giants, like Amoeba in Hollywood, failed to fill the gap. Amoeba was like the Walmart of vinyl (I'll amend that to say that Amoeba today is a far more satisfying experience, but it's no Vinyl Fetish, that’s for sure).For me, in the late 70s and early 80s, Aron's was a rite of passage. I was living in Hollywood, having shrugged off the Valley (sorry Moby Disc), and I'd wander over to Melrose. Aron's was there before Melrose was trendy, before Poseur and Cowboys and Poodles, maybe even before Aardvark and Flip. Then came Rene's All Ears, which was smaller and more intimate. I'd be lurking among the bins in my painter's pants and my cons flipping through the racks, the stack of $3.00 LPs getting bigger and bigger. I invested a lot of money and a lot of time.

Just a Cool Pic of Capitol Records Pre-Tower. It Would Become Dot Records.

Just a Cool Pic of Capitol Records Pre-Tower. It Would Become Dot Records.Wallichs Was to the Left.By '81 or so, when the new wave kicked in, it was all about Vinyl Fetish, a more European-like venue with 12-inch import singles lining the walls in plastic sleeves. If you wanted something you’d point. At Aron's, I was more eclectic, everything from Lena Lovich to The Wall, but at Vinyl Fetish, it was all about The Cure, Blancmange, Haircut 100, and especially about New Order. It was there that I heard "Blue Monday" for the first time, the biggest selling 12-inch of all time. It was there that I first saw the video for "Girls on Film."

My collection of imports was, by 1983, over a thousand units. Honestly, if I had them today, I could buy a house. Indirectly, maybe I did. I was accepted at UCLA and then transferred to Rutgers College and unable to afford my education, I sold all my records back to Aron's. They bought the whole collection for $4300, enough for my first year as a Bruin.

Published on November 10, 2020 07:28

October 31, 2020

VOTE

On a day that saw more than 100,000 new cases of COVID-19 and 1000 more deaths, the president called American doctors and health care workers frauds.Shame on the president and shame on you if you vote for him. Don’t be a part of the problem. Vote responsibly and compassionately or stay home.

On a day that saw more than 100,000 new cases of COVID-19 and 1000 more deaths, the president called American doctors and health care workers frauds.Shame on the president and shame on you if you vote for him. Don’t be a part of the problem. Vote responsibly and compassionately or stay home.Save the nation. Remove the virus from the White House.

Published on October 31, 2020 05:23

October 29, 2020

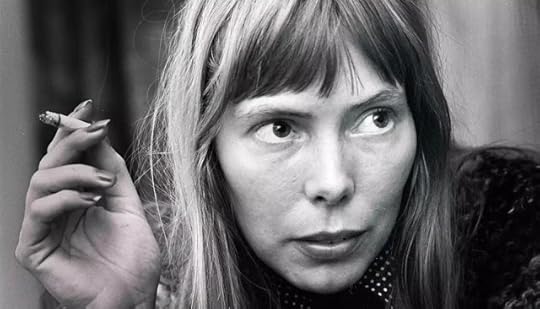

Joni Mitchell - For the Roses

Joni went home after Blue; not California: Canada, and the result, For the Roses (AM8), was like Court and Spark practice; multi-layered madness, crazy harmonies and a myriad of Jonis. Her voice hadn't matured, it succumbed instead to cigarettes, and if chain-smoking ever did anyone justice, well it was us. Side one continues Joni's pre-70s groove, vacillating from love song to social observation with several truly topical pieces. One in particular "Cold Blue Steel and Sweet Fire," describes so beautifully heroin addiction, growing in prevalence in the So. Cal. scene and part of the reason Joni took refuge in Saskatoon (more on it in a moment). Side one essentially starts off where Blue ended. The album opener, "Banquet," is a song that uses a dinner table as a metaphor for the world Joni experienced: "Some get the gravy, and some get the gristle...And some get nothing, though there's plenty to spare." It's just Joni and her piano. Angry chords force her point of the greedy world we live in. This is followed by the aforementioned (and superb) "Cold Blue Steel And Sweet Fire." This chilling song details the life of a heroin addict, the inescapable insatiability and desperation for the drug-fix. The imagery created from these lyrics is dark, sharp and gleaming: "Come with me, I know the way," she sings, "It's down, down, down, the dark ladder." The reeds fill the song with an airy, meditative atmosphere, while Joni's vocal delivery is so sensual and the melody so lovely. "Barangrill" provides a much-needed respite while very much in-theme with the tense, tight nature of the album overall. "Lesson In Survival" is the first love song of the album, about what is always new, the longing and need for love: "I'm gonna get a boat, and we can row it, if you ever get the notion, to be needed by me."

Joni went home after Blue; not California: Canada, and the result, For the Roses (AM8), was like Court and Spark practice; multi-layered madness, crazy harmonies and a myriad of Jonis. Her voice hadn't matured, it succumbed instead to cigarettes, and if chain-smoking ever did anyone justice, well it was us. Side one continues Joni's pre-70s groove, vacillating from love song to social observation with several truly topical pieces. One in particular "Cold Blue Steel and Sweet Fire," describes so beautifully heroin addiction, growing in prevalence in the So. Cal. scene and part of the reason Joni took refuge in Saskatoon (more on it in a moment). Side one essentially starts off where Blue ended. The album opener, "Banquet," is a song that uses a dinner table as a metaphor for the world Joni experienced: "Some get the gravy, and some get the gristle...And some get nothing, though there's plenty to spare." It's just Joni and her piano. Angry chords force her point of the greedy world we live in. This is followed by the aforementioned (and superb) "Cold Blue Steel And Sweet Fire." This chilling song details the life of a heroin addict, the inescapable insatiability and desperation for the drug-fix. The imagery created from these lyrics is dark, sharp and gleaming: "Come with me, I know the way," she sings, "It's down, down, down, the dark ladder." The reeds fill the song with an airy, meditative atmosphere, while Joni's vocal delivery is so sensual and the melody so lovely. "Barangrill" provides a much-needed respite while very much in-theme with the tense, tight nature of the album overall. "Lesson In Survival" is the first love song of the album, about what is always new, the longing and need for love: "I'm gonna get a boat, and we can row it, if you ever get the notion, to be needed by me."

On side two we even get a hit and some radio play, ironically, in "You Turn Me On, I'm a Radio," a song in which it became obvious that Joni would shirk song structure for good, but it's an altogether new magic we find in "See You Sometime" and "Electricity." This is our first glimpse of the inimitable Joni. "Blonde in the Bleachers" is the best song ever written about a rock star on the road. "It seems like you've got to give up such a piece of your soul when you give up the chase," she sings, about finding identity in oneself and meaning in whomever one fucks. The songs weren't protest, they were reflection, instead, allowing the listener to determine the politicism rather than pounding her over the head with it. The album's standout, particularly in this vein, is "Woman of Heart and Mind:" "Drive your bargains, push your papers, win your medals, fuck your strangers; don't it leave you on the empty side?" It isn't protest, it's a call-out, and so much more effective because of it.

For the Roses is a gorgeous musical tapestry that epitomizes the best of Mitchell's poetic prowess and musical genius. It comes into your life and weaves itself firmly into your fabric. It is a testament to the days when albums were listened to from start to finish; each song a stopping-point on a musical journey. After the ultra confessional Blue, Joni found ithard to move forward and holed herself up in a Canadian cabin for more than a year. For the Roses shows her sorting out the confused and bleeding emotions she felt at the time. The result, another brilliant masterwork with all of the inner pain of "Blue"

Published on October 29, 2020 04:23

October 28, 2020

Woman of Heart and Mind

As a teacher, I would hand out dittos (well, not dittos, I'm not that old), photocopies of lyrics, and the class would analyze them line by line. In the last couple of posts on FaceBook, I offered up my diatribe about Kate Bush songs without providing the lyrics, which makes it more of a sermon than a forum. Instead, today, this post brings it home with the poet laureate of American realism, Joni Mitchell. I left L.A. in 1984 but like Joni, "I couldn’t let go of L.A., city of the fallen angels." 50 years ago with her album Ladies of the Canyon, Joni established herself as a singer-songwriter and recording artist. Her first two albums, while noteworthy, of course, didn’t hint at her brilliance. Joni would follow up Ladies of the Canyon with her masterpiece, Blue, and then with For the Roses, the most underrated LP in her canon. For the Roses is Joni Mitchell at her most poetic, every song a homerun hinting at the jazz of Joni’s future with a band unmatched, particularly Tom Scott and Wilton Felder, and the guitars of Stephen Stills (“Blonde in the Bleachers") and James Burton (“Cold Blue Steel”). And while both “Let the Wind Carry Me” and “Judgment of the Moon and the Stars” are epic, lyrically I’m drawn to the suite that begins with “Blonde in the Bleachers” and follows up with a song that, though written from a woman’s intuitive perspective, hits the same nerve for those men trying to listen, “Woman of Heart and Mind.” Instead of sermonizing, here are the lyrics:I am a woman of heart and mindWith time on her handsNo child to raiseYou come to me like a little boyAnd I give you my scorn and my praiseYou think I'm like your motherOr another lover or your sisterOr the queen of your dreamsOr just another silly girlWhen love makes a fool of meAfter the rush when you come back downYou're always disappointedNothing seems to keep you highDrive your bargainsPush your papersWin your medalsFuck your strangersDon't it leave you on the empty side?I'm looking for affection and respectA little passionAnd you want stimulation, nothing moreThat's what I thinkBut you know I'll try to be there for youWhen your spirits start to sinkAll this talk about holiness nowIt must be the start of the latest styleIs it all books and wordsOr do you really feel it?Do you really laugh?Do you really care?Do you really smileWhen you smile?You criticize and you flatterYou imitate the bestAnd the rest you memorizeYou know the times you impress me mostAre the times when you don't tryWhen you don't even try

Published on October 28, 2020 09:15

October 26, 2020

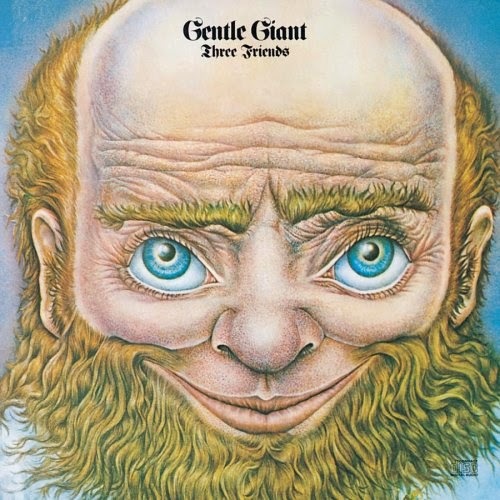

A Brief History of the Gentle Giant

Woe to the musician who can actually play his or her instrument. In that direction ridicule awaits, or so the three-chord purist would have you believe. In this regard, consider the plight of Gentle Giant, among the most reviled of prog-rock outfits from the 70s, at least in the eyes of the rock purists, I'm calling bullshit. Reality is, 4/4 time gets pretty boring pretty quickly; counterpoint is challenging and aesthetically pleasing to the ears, music with texture and complex instrumentation is far more interesting then the bland purist backbeat (think Please Please Me Vs. Sgt. Pepper).

Woe to the musician who can actually play his or her instrument. In that direction ridicule awaits, or so the three-chord purist would have you believe. In this regard, consider the plight of Gentle Giant, among the most reviled of prog-rock outfits from the 70s, at least in the eyes of the rock purists, I'm calling bullshit. Reality is, 4/4 time gets pretty boring pretty quickly; counterpoint is challenging and aesthetically pleasing to the ears, music with texture and complex instrumentation is far more interesting then the bland purist backbeat (think Please Please Me Vs. Sgt. Pepper).

Gentle Giant, founded by three brothers with a Glasgow Blues background (yeah, it's a thing), succeeded in a daring fusion of jazz, classical and rock. The strength of the sextet was Kerry Minnear's keyboards (Minnear had a degree in music from the Royal Academy), the guitar virtuosity of Gary Green (a blues veteran) and Phil Schulman’s rococo woodwinds, with each member a multi-instrumentalist. Besides the complex scores, their sound was light years removed from even the most progressive or fusion oriented bands, particularly Derek Schulman's nearly inhuman (giant) vocals, so aseptic they more resembled conservatory solfeggios and Gregorian chant. This wasn't rock; it was some other medieval concoction.

The first album, Gentle Giant (AM5, Vertigo, 1970), only points to who they would or could become with the dissonant counterpoint, the nearly eponymous peculiarity that made them renowned not materializing until Acquiring The Taste (AM6, Vertigo Records, 1971). Each Giant played a miscellany of instruments with massive use of keyboards lending a symphonic quality to the album. Kerry Minnear's role included electric piano, organ, mellotron, vibraphone, synthesizer, celesta, harpsichord and vocals, while bassist Ray Schulman added violin and viola, and Tony Visconti, David Bowie's producer, added flute. There are typanis, skulls, claves, recorders, jawbones and cowbells. Acquiring the Taste is exactly that, a veritable taste of complex honey.

Three Friends (AM 7, Columbia, 1972), essentially a "rock opera," contains six long ballads with "Mister Class And Quality" and "Working All Day" the most accessible. "Prologue," "Schooldays" and "Peel The Paint" were like cryptic chamber-music. The harder-edged Octopus (AM8, Columbia, 1972), with the exception of "Think of Me With Kindness," is almost dauntingly complex, with counterpoint and opposing melodies riddled with dead air and aural or negative space, the rest as intoxicating as the note. Generally it's more math-rock, Bach-rock than art-rock in which each instrumental passage is layered and interwoven and complete unto itself. In particular, the vocal harmonies of Knots, inspired by psychologist RD Laing's enigmatic poems (?), were an antithesis to the British tradition both musically and thematically, and the clumsy "Dog's Life," is an eccentric paean to giant's best friend.

In A Glass House (AM8, Vertigo/WWA, 1973 - not initially released in the US), another concept album, is probably their most ambitious work. The exuberant experimentation took particular advantage of Phil Schulman’s departure from the band earlier in the year. The socio-political concept, The Power And The Glory (AM7, Capitol, 1974) is less ambitious yet still fluid and classy and possibly their roughest edge, tempered only by Kerry Minnear's beautiful "Aspirations."

Free Hand (AM8, Capitol, 1975) is Gentle Giant’s "medieval" album. Nearly all the songs ("Just The Same," "On Reflection," "Free Hand," "Time To Kill," "His Last Voyage") reached a formal perfection in their attempt at reinventing the rock song.

And then it was over. Record company pressures, a changing listenership, a new sense that progressive rock was not only passe but that it had done a disservice, led to albums that didn't make sense except as contractual obligations. Part jazz-rock, part folk, part medieval polyphony or renaissance dance music, Gentle Giant was a crazy hybrid of music that shouldn't have worked on any level, but instead, in perfect counterpoint, worked on them all.

Published on October 26, 2020 04:40

October 23, 2020

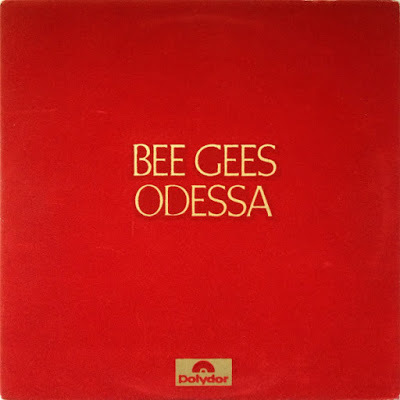

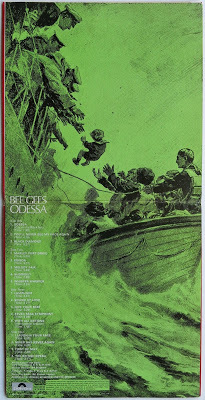

Bee Gees Odessa

Despite what may be the most lavish LP cover in rock history, a velour sleeve in a deep red stamped in gold with the album's title and band name, the Bee Gees' epic was nonetheless doomed from the get-go. Fans had grown accustomed to the psych-pop of Idea and 1st and had gobbled up hits like "Holiday," but for this, they merely scratched their heads. Indeed the Gibb brothers themselves derided producer Robert Stigwood for browbeating them into such a grandiose venture, despite the infighting that had them disagree on everything else.

Despite what may be the most lavish LP cover in rock history, a velour sleeve in a deep red stamped in gold with the album's title and band name, the Bee Gees' epic was nonetheless doomed from the get-go. Fans had grown accustomed to the psych-pop of Idea and 1st and had gobbled up hits like "Holiday," but for this, they merely scratched their heads. Indeed the Gibb brothers themselves derided producer Robert Stigwood for browbeating them into such a grandiose venture, despite the infighting that had them disagree on everything else. My grandmother worked for a psychiatrist as a housekeeper in 1969. She'd take me at times to their home, a beautiful mid-century modern structure with a bright red door, a pool and a guesthouse. I'd play with the dogs, dalmatians; she'd give me lunch in a bright red kitchen, and then she'd let me sit in the son's room and play his records. One of those records was Odessa. I liked the look and feel of it, the soft velvet – the music, not so much (it was on that same day that I first heard Tommy as well). I never owned Odessa. Years later I'd picked it up in a record store bin and put it back down. A mint copy is today on my bucket list.

As the years sailed by, the fearless ambition of Odessa became more difficult to dismiss. Like sonic landmarks with similar histories – Pet Sounds, Forever Changes – Odessa finds its authors amid personal crisis while working at the absolute peak of their powers. Capping a furious two-year whirlwind in which the group produced four albums and half-a-dozen Top 40 singles, arguments over Odessa's production, coupled with an exhausting schedule, created a battle between Barry and Robin Gibb for the leadership of the group. Though they finally reconvened in 1971, they never again produced a work as focused and affecting as Odessa.

This was the Bee Gees' fourth album of all-original material in just over 18 months and a double LP at that. Odessa may be the pinnacle of "baroque-pop," with its lush string arrangements and lavish production. It starts and ends quite remarkably, opening with the 7-minute epic title track and closing with the instrumental "The British Opera." If it sounds pretentious, you bet, but keep in mind that it was recorded in the days when pretension was called ambition (think Let It Be). That said, not everything works. The album's two excursions to the wild west failed to move me and few critics find the necessity in the instrumentals (I like them). Far better are the last vestiges of the silly-psychedelia the band permitted themselves, which made their first two albums such fun, namely "Edison", "Suddenly" and "Whisper Whisper."

This was the Bee Gees' fourth album of all-original material in just over 18 months and a double LP at that. Odessa may be the pinnacle of "baroque-pop," with its lush string arrangements and lavish production. It starts and ends quite remarkably, opening with the 7-minute epic title track and closing with the instrumental "The British Opera." If it sounds pretentious, you bet, but keep in mind that it was recorded in the days when pretension was called ambition (think Let It Be). That said, not everything works. The album's two excursions to the wild west failed to move me and few critics find the necessity in the instrumentals (I like them). Far better are the last vestiges of the silly-psychedelia the band permitted themselves, which made their first two albums such fun, namely "Edison", "Suddenly" and "Whisper Whisper."Elsewhere they settle into solid balladry including the remarkably candid "I Laugh In Your Face" and "You'll Never See My Face Again", the should-have-been-a-hit "Lamplight" and the yearning "Never Say Never Again". The two singles, both nearly child-like in their simplicity and far from chart-toppers, "First Of May" and "Melody", fail to stand out in the good company here. Odessa spawned a family feud over whose song should get to be a single which escalated into a two-year hiatus. After that, the brothers were never the same again as they struggled to reinvent themselves for the new decade. Of course they did, and spectacularly, somewhere out on the dance-floor, but that is a whole different discussion.

Published on October 23, 2020 13:24

October 12, 2020

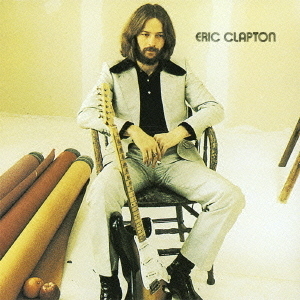

After Midnight - Clapton - 50 Years Ago

50 Years Ago J.J. Cale's "After Midnight" hit the charts in a cover by Eric Clapton. It was released by Cale in 1966 to no acclaim. But Clapton's success with the song prompted Cale to re-record the song for 1972's Naturally. It's interesting that this is one of those signature songs with two signatures.

50 Years Ago J.J. Cale's "After Midnight" hit the charts in a cover by Eric Clapton. It was released by Cale in 1966 to no acclaim. But Clapton's success with the song prompted Cale to re-record the song for 1972's Naturally. It's interesting that this is one of those signature songs with two signatures. When Eric Clapton was working with Delaney & Bonnie Bramlett, Delaney Bramlett, a relative muse to Eric, introduced him to the music of Cale. "After Midnight" was the first of several Cale songs covered by Clapton. The performers on the radio version were Clapton on vocals and guitar, Bobby Whitlock on organ and vocals, Jim Gordon on drums, Delaney Bramlett on rhythm guitar, Carl Radle on bass, Leon Russell on piano, Jim Price on trumpet, and Bobby Keys on saxophone. While Clapton was no stranger to the charts, having several hits with the Yardbirds and Cream, this was his first solo triumph.

Published on October 12, 2020 05:57

October 11, 2020

Rock Lit 101 - Chaucer and the Piano Man

The Executive Lounge, 1972I had an English professor who pointed out that "Piano Man" was Chaucerian in concept and structure, bearing resemblance to the General Prologueof the Canterbury Tales. In each the we meet simple folk in quick succession, in such a way that we want to know more about them; our attention is drawn away from the narrator as we take his perspective.

The Executive Lounge, 1972I had an English professor who pointed out that "Piano Man" was Chaucerian in concept and structure, bearing resemblance to the General Prologueof the Canterbury Tales. In each the we meet simple folk in quick succession, in such a way that we want to know more about them; our attention is drawn away from the narrator as we take his perspective.To telle yow al the condicioun, [It’s nine o’clock on a Saturday]

Of ech of hem, so as it semed me, [The regular crowd shuffles in]

And whiche they weren, and of what degree, [There’s an old man sitting next to me]

And eek in what array that they were inne, [Making love to his tonic and gin.]

And at a knyght than wol I first bigynne...

The verses are sung from the point of view of a bar piano player who focuses on the regulars: an old man, John, the bartender, Paul, the "real estate novelist," Davy, a sailor, and the waitress. These are characters with unrequited, dissatisfying lives who've come to "forget about life for a while." The chorus, in bar-room sing-along style, comes from the patrons themselves, who plead, "Sing us a song/ You're the piano man/ Sing us a song, tonight/ Well, we're all in the mood for a melody/ And you've got us feeling all right."

The verses are sung from the point of view of a bar piano player who focuses on the regulars: an old man, John, the bartender, Paul, the "real estate novelist," Davy, a sailor, and the waitress. These are characters with unrequited, dissatisfying lives who've come to "forget about life for a while." The chorus, in bar-room sing-along style, comes from the patrons themselves, who plead, "Sing us a song/ You're the piano man/ Sing us a song, tonight/ Well, we're all in the mood for a melody/ And you've got us feeling all right."The song was inspired by a gig in L.A. at The Executive Room while Joel was recovering from the failure of his first album Cold Spring Harbor. The LP tanked and Joel was looking to be released from his contract with Family Records in order to sign with Columbia. The Cold Spring Harbor Billy Joel effectively disappeared,playing under a pseudonym with handbills and advertisements touting "The Piano Stylings of Bill Martin." During his time at the lounge, Joel wrote "Piano Man" based directly on his experiences at the bar.

The narrative shifts away from the crowd and back to Bill Martin to prepare for the verse: "And the piano sounds like a carnival,/ And the microphone smells like a beer./ And they sit at the bar, and put bread in my jar,/ And say, 'Man, what are you doing here?'" These lines reflect a Columbia Records Exec who saw how talented Billy Joel (Bill Martin) was. After a fateful performance, the man, asked Bill why he was playing little gigs at the piano lounge. The man ultimately realizing that Bill Martin was actually the Billy Joel they were searching for, was finally able to finagle him out of his contract with Family Records.

Though Billy Joel would go on to produce hit after hit, it's the story songs, his Canterbury Tales, songs like "Scenes from Italian Restaurant," "New York State of Mind" and "Downeaster, 'Alexa'", that would cement his rep as a preeminent singer/songwriter and elevate his craft to something vaguely Chaucerian.

Published on October 11, 2020 14:45

October 7, 2020

EVH - 1955 - 2020

My most vivid Van Halen memory predates the band. The pic above is the brothers' first venture, The Trojan Rubber Company. They played small venues, Pasadena City College and at PHS. I remember a time, I think it was 1972, when my friends ventured into Pasadena for a gig. I wasn't allowed to go. By then, I think they were already playing under the name Van Halen.

Published on October 07, 2020 05:42