Stan Garfield's Blog, page 4

May 7, 2025

Tim Wood Powell: Profiles in Knowledge

This is the 115th article in the Profiles in Knowledge series featuring thought leaders in knowledge management. Tim Wood Powell is a thought leader and organizational catalyst in the economics and strategy of knowledge and intelligence. The President of The Knowledge Agency®, he is an epistemic resources strategist. Tim earned degrees in knowledge (lab sciences, philosophy and psychology) and management (analytics, finance) from Yale. He spent ten years at KPMG and PwC in data analytics and business design and development, then several years helping to establish the emerging field of corporate strategic intelligence. Tim’s current work includes knowledge sustainability, knowledge quality assurance, and the value of knowledge.

Tim and I were both adjunct instructors for Columbia University’s Information and Knowledge Strategy graduate program. We are authors in De Gruyter’s Knowledge Services book series. He has been a faithful participant in the monthly calls of the SIKM Leaders Community. And I am impressed that in addition to being a knowledge management consultant, Tim is also a musician.

Background EducationYale School of Management — MBA, Concentrations in Data Analysis, Operations Research, and FinanceYale University — BA, Psychology and Philosophy; Pre-medical Laboratory SciencesExperienceThe Knowledge Agency — President, 1996 — PresentThe Conference Board — Senior Fellow, 2019 — PresentColumbia University School of Professional Studies — Adjunct Faculty, 2014–2017Long Island University Palmer School of Library and Information Science — Adjunct Faculty, 2004–2005Find/SVP, Managing Director, Strategic Research, 1989–1996PwCManager, Marketing Technologies. 1987–1989Manager, Business Development, 1985–1987Manager, New Service Development, 1983–1985KPMG — Senior Consultant, 1979–1983ProfilesLinkedInTwitterThe Knowledge AgencyConference BoardDeGruyter BrillColumbia University School of Professional StudiesProfiles in Knowledge: Columbia University IKNSSoundCloud

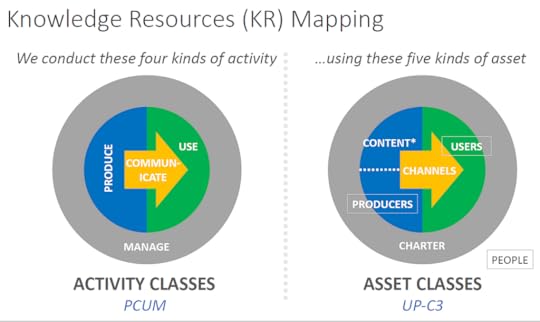

EducationYale School of Management — MBA, Concentrations in Data Analysis, Operations Research, and FinanceYale University — BA, Psychology and Philosophy; Pre-medical Laboratory SciencesExperienceThe Knowledge Agency — President, 1996 — PresentThe Conference Board — Senior Fellow, 2019 — PresentColumbia University School of Professional Studies — Adjunct Faculty, 2014–2017Long Island University Palmer School of Library and Information Science — Adjunct Faculty, 2004–2005Find/SVP, Managing Director, Strategic Research, 1989–1996PwCManager, Marketing Technologies. 1987–1989Manager, Business Development, 1985–1987Manager, New Service Development, 1983–1985KPMG — Senior Consultant, 1979–1983ProfilesLinkedInTwitterThe Knowledge AgencyConference BoardDeGruyter BrillColumbia University School of Professional StudiesProfiles in Knowledge: Columbia University IKNSSoundCloud ContentThe Knowledge AgencyLinkedIn PostsCompeting in the Knowledge Economy (archive of old blog)BlogGenerative AI: Toward A Balanced ViewEnterprise Knowledge: What Is It?Managing the UnmeasurableKnowledge Governance in the Age of AIKnowledge Erosion: How to Avoid ItIntroducing Knowledge Resources Management (KRM)Knowledge: To Have and Have NotThe Speed of KnowledgeKnowledge Is the BusinessMaking Knowledge SustainableIndustrial-Strength KnowledgeIs Knowledge Dead?Knowledge By NumbersWhat Is Knowledge Strategy?What Is the Difference Between Information and Knowledge?Building Knowledge Value In PracticePositioning Knowledge For ValueThe Knowledge PayoutWhatever Happened to Knowledge Management?Knowledge LeadershipKnowledge Strategy SimplifiedStrategic Knowledge — What’s New Is OldMetrics That MatterKnowledge Is Power — Not!Making Intelligence RelevantRebalance Your Knowledge PortfolioInformation Overload: An Urban Myth?The Knowledge ArchipelagoKnowledge Management Ground ZeroThe Knowledge Value ChainAcademia.eduReuters business briefing: An essential tool for real-time strategyBenchmarking: A new use for competitive intelligenceaskSam: The Swiss army knife of file managementAnalyzing your competitionCompetitive knowledge management: You can’t reengineer what never mas engineered in the first placeThe Value of Knowledge: The Economics of Enterprise Knowledge and IntelligenceThe Knowledge Value Chain: How to Fix It When It BreaksKnowledge by Numbers

ContentThe Knowledge AgencyLinkedIn PostsCompeting in the Knowledge Economy (archive of old blog)BlogGenerative AI: Toward A Balanced ViewEnterprise Knowledge: What Is It?Managing the UnmeasurableKnowledge Governance in the Age of AIKnowledge Erosion: How to Avoid ItIntroducing Knowledge Resources Management (KRM)Knowledge: To Have and Have NotThe Speed of KnowledgeKnowledge Is the BusinessMaking Knowledge SustainableIndustrial-Strength KnowledgeIs Knowledge Dead?Knowledge By NumbersWhat Is Knowledge Strategy?What Is the Difference Between Information and Knowledge?Building Knowledge Value In PracticePositioning Knowledge For ValueThe Knowledge PayoutWhatever Happened to Knowledge Management?Knowledge LeadershipKnowledge Strategy SimplifiedStrategic Knowledge — What’s New Is OldMetrics That MatterKnowledge Is Power — Not!Making Intelligence RelevantRebalance Your Knowledge PortfolioInformation Overload: An Urban Myth?The Knowledge ArchipelagoKnowledge Management Ground ZeroThe Knowledge Value ChainAcademia.eduReuters business briefing: An essential tool for real-time strategyBenchmarking: A new use for competitive intelligenceaskSam: The Swiss army knife of file managementAnalyzing your competitionCompetitive knowledge management: You can’t reengineer what never mas engineered in the first placeThe Value of Knowledge: The Economics of Enterprise Knowledge and IntelligenceThe Knowledge Value Chain: How to Fix It When It BreaksKnowledge by NumbersSeven Steps to Improving Knowledge ROI

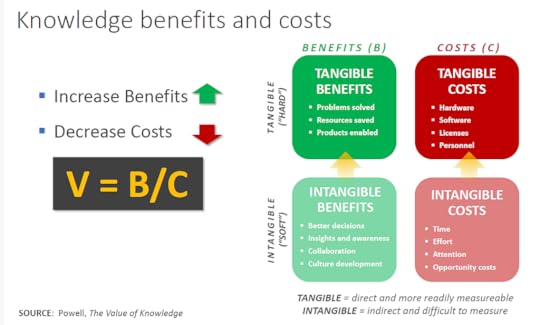

Understand the enterprise value system. What does your client organization measure and reward? Each organization has its own purpose and mission, enterprise metrics, KPIs, and so on. Start by understanding how the organization thinks and communicates about value, both internally and externally. Note that aspects of this will be verticalized, i.e., specific to the client’s industry.Link knowledge metrics directly to these existing enterprise metrics. This linkage is the primary source of strength and ROI for a knowledge initiative. Knowledge goals and metrics become less relevant the farther they are from organizational goals and metrics.Identify behaviors you are trying to produce, optimize, or change. Metrics work — because they drive behavior within the organization. Which behaviors are working in achieving desired enterprise outcomes, and which need to improve?Measure what matters. Develop metrics for those behaviors in a way that is most effective for the benefits (i.e., Results, Outcomes, and Impact) you are trying to achieve. This requires a deep understanding of cause and effect.Bend the value curve. Engage available value levers to drive benefits up, and costs down. This point gets a little involved, I’ll explain this in a separate post.Monitor and anticipate. With each metric comes the risk that people will “work to the metric” — and not to what really produces value. Once operational, metrics should be assessed periodically to insure they are producing the desired outcomeAdd value continually. Adding value is not a one-time event — it’s an ongoing process driven by a deep underlying commitment to thought leadership.What is Knowledge Strategy?Knowledge Strategy is the practice of developing and deploying enterprise knowledge and its component assets as essential and integral resources in competitive business strategy. KS means, simply, actively recognizing and using knowledge as a strategic resource and a direct bridge to competitive advantage.

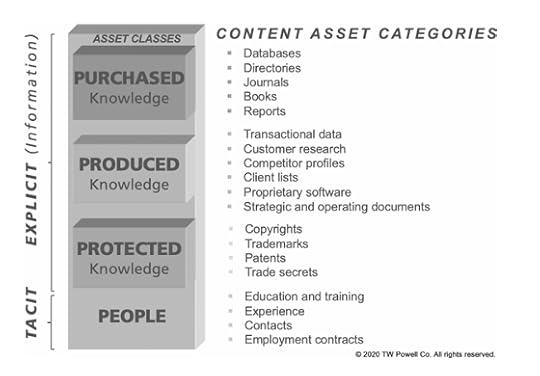

In other words, knowledge strategy should not be developed separately from a competitive business strategy. The two should be developed and implemented in close coordination, as shown in the Strategic Knowledge Architecture diagram below — and should both respond to the value model defined by the overall purpose and mission of the enterprise.

Selected Bibliography“Measuring the Value of Information Investments”. The Journal of the Association for Global Strategic Information (AGSI) 3, no. 2 (1994). AGSI.“The Information Metabolism”. Competitive Intelligence Review 6, no. 4 (1995): 41–45. John Wiley & Sons.“Competitive Knowledge Management: You Can’t RE-Engineer What Never was Engineered in the First Place”. Competitive Intelligence Review 8, no. 1 (1997): 40–47. John Wiley & Sons.“Knowledge: The Engine of Value”. Workshop presented to the Society of Competitive Intelligence Professionals, 1999.“Disinformation About Knowledge Management”. Tech Knowledge column in Competitive Intelligence Magazine 3 (1). Society of Competitive Intelligence Professionals, 2000.“The Knowledge Value Chain: How to Fix It When It Breaks”. Proceedings of the 22nd National Online Meeting, Information Today, 2001b.“From Knowledge to Value: A Roadmap” Keynote address to Management Consultants Association Summit. Istanbul, Turkey, 2015a.“Champagne or Grapes? The Commoditization of Knowledge Services and What To Do Now About It”. Presentation to Special Libraries Association New York 2017 Conference and Expo, 2017b.“Brand Equity Risk: Challenges in the Digital Marketing Era”. The Conference Board, 2019.Quotes on KnowledgeKnowledge is the master resource that controls the others: land, labor, and capital. But because knowledge is intangible — therefore not formally recognized by today’s accounting principles and practices — it’s often poorly-tended, under-resourced, or even entirely neglected.Knowledge is an enterprise resource — and should be held to the same ROI standards that any others are. Knowledge should be managed as an investment — not as an expense.Knowledge is highly leverageable; even modest improvements in how it’s managed can yield disproportionately large outcomes. Any organization — large or small, public, private, or non-profit, in any industry — will benefit.The Value of KnowledgeBook

Selected Bibliography“Measuring the Value of Information Investments”. The Journal of the Association for Global Strategic Information (AGSI) 3, no. 2 (1994). AGSI.“The Information Metabolism”. Competitive Intelligence Review 6, no. 4 (1995): 41–45. John Wiley & Sons.“Competitive Knowledge Management: You Can’t RE-Engineer What Never was Engineered in the First Place”. Competitive Intelligence Review 8, no. 1 (1997): 40–47. John Wiley & Sons.“Knowledge: The Engine of Value”. Workshop presented to the Society of Competitive Intelligence Professionals, 1999.“Disinformation About Knowledge Management”. Tech Knowledge column in Competitive Intelligence Magazine 3 (1). Society of Competitive Intelligence Professionals, 2000.“The Knowledge Value Chain: How to Fix It When It Breaks”. Proceedings of the 22nd National Online Meeting, Information Today, 2001b.“From Knowledge to Value: A Roadmap” Keynote address to Management Consultants Association Summit. Istanbul, Turkey, 2015a.“Champagne or Grapes? The Commoditization of Knowledge Services and What To Do Now About It”. Presentation to Special Libraries Association New York 2017 Conference and Expo, 2017b.“Brand Equity Risk: Challenges in the Digital Marketing Era”. The Conference Board, 2019.Quotes on KnowledgeKnowledge is the master resource that controls the others: land, labor, and capital. But because knowledge is intangible — therefore not formally recognized by today’s accounting principles and practices — it’s often poorly-tended, under-resourced, or even entirely neglected.Knowledge is an enterprise resource — and should be held to the same ROI standards that any others are. Knowledge should be managed as an investment — not as an expense.Knowledge is highly leverageable; even modest improvements in how it’s managed can yield disproportionately large outcomes. Any organization — large or small, public, private, or non-profit, in any industry — will benefit.The Value of KnowledgeBook The Knowledge Balance Sheet

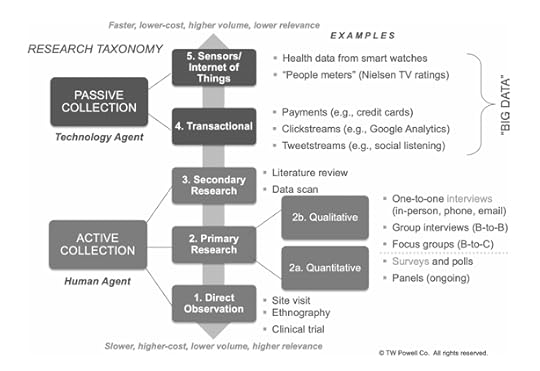

The Knowledge Balance Sheet Map of Potential Data Sources

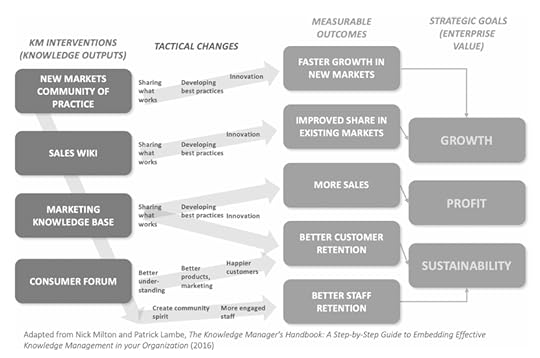

Map of Potential Data Sources Benefits MappingPresentation

Benefits MappingPresentation

Articles by OthersThe Value of Knowledge by Guy St. ClairThe Knowledge Community: Method or Myth? by Guy St. ClairA Provocative Question by Guy St. ClairDefining The Knowledge Strategist by Guy St. Clair

Articles by OthersThe Value of Knowledge by Guy St. ClairThe Knowledge Community: Method or Myth? by Guy St. ClairA Provocative Question by Guy St. ClairDefining The Knowledge Strategist by Guy St. ClairGetting to that KD/KS excellence is a goal Tim Powell recognizes. As someone who works with companies as they pursue knowledge value, Powell has frequent opportunities to observe what works and what doesn’t, and his focus on the Knowledge Value Chain® helps knowledge strategists relate to how companies work with knowledge value.

Powell’s basic focus, re-iterated recently, sets up an almost-perfect scenario for describing how the knowledge strategist can perform, when knowledge value comes into the picture:

‘Value creation’ is the fundamental keystone of our competitive economy — and one of the genuine Mysteries of the Universe. For me one of the best things about business school was the opportunity to think and talk about value for two intense years — both in an abstract theoretical sense, and in very applied sense as it relates to creating value in live casebook situations.

You learn not to take value for granted, even to have a certain reverence for it — that it’s transient, not to be treated carelessly — it can come and go. Much like other living organisms, products, business models, companies, even whole industries have life cycles — they’re born, they grow, they thrive, they ebb, they die.

Knowledge Services: A Strategic Framework for the 21st Century Organization by Guy St. ClairEpilogue — Knowledge Services. The Critical Management Discipline for the Twenty-First Century Organization

Tim Powell, President and CEO of The Knowledge Agency®, created the concept of the knowledge value chain and is recognized for his success with KVC as he applies it for clients and students (he, too, is a Faculty Facilitator at Columbia University in the City of New York). Tim joins with me in acknowledging the value of our historical precedents in information, knowledge, and strategic learning studies:

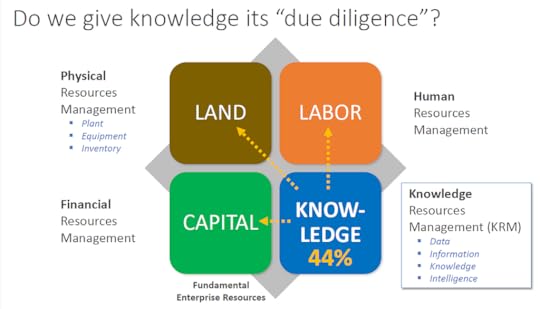

Classical economists defined the three essential productive resources of an economy as: LAND (natural resources), LABOR (human resources), and CAPITAL (financial resources.) Today we recognize a fourth productive resource, KNOWLEDGE (“epistemic” resources, also including data, information, and intelligence).Each of these sets of resources has benefitted from intensive development and pre-eminence during a specific time frame. During the nineteenth century, we achieved mastery of natural resources (mining, manufacturing, materials, etc.). During the early twentieth century, we began to understand human resources (thanks to the work of Frederick Taylor, Henry Ford, and others). In the latter part of the twentieth century, financial principles and technologies became more widely understood and practiced.During the twenty-first century we must (and we will) achieve greater understanding and mastery of epistemic resources — a science of knowledge, accompanied by rapid development of knowledge practices and technologies to help our enterprises perform effectively in the “knowledge economy.”The pioneering work of knowledge strategists and knowledge thought leaders — and those they learn from — has paved the way for these developments. To those starting on your journey of exploration and discovery in the “knowledge domain,” behold and benefit from those who came before you. They did not produce all the answers — in that, they have left plenty for you to accomplish. But they did — spurred on by the needs of their clients, their colleagues, and their consciences — begin to ask the questions: how can knowledge do more for people, for organizations, for civil society — indeed, for the world? Knowledge services and knowledge strategy are leading the way. Listen to those who came before, learn from them, use their insights — and be richly rewarded.Precious Lore by Darren BaguleyNevertheless, much of the techniques that apply to any change-management process can be applied to a KM implementation, says Accenture’s talent and organization performance practice senior executives, Tom Hoglund and Tim Powell.

“The issues are around how you change the culture from knowledge being something you covet, to knowledge being something you share,” says Hoglund. “That involves looking at all the standard levers you would use to change behavior. That includes aligning learning and development with the KM systems. It’s also about alignment with the performance-management system.”

Powell adds that leadership behavior is critical as well. “As with any change-management process, the executive team needs to monitor and measure the behaviors and build them into performance evaluations, and so on.

“But leaders need to be cheerleading the activities, talking about where people are using the KM system to win business, getting things done smarter and faster, as well as banging people over the head if they’re not doing the right thing.”

The business case for business Intelligence by Mor Sela (references Intelligence: Building the Business Case)Position intelligence as an investment. Proving a business case consists of creating a reasonable expectation among investors — in this case, your management team — that value will be created.Let the numbers do the talking. Value in a business context is best measured economically — with hard numbers. Numbers are the language of modern business, and without them, you might as well be speaking classical Greek.Work hard on your business case. While assigning hard numbers to intelligence may be challenging, it is by no means impossible. You may have to sharpen your pencil and put your thinking cap on.Don’t reinvent the wheel. There are existing models “out there” (like the discounted cash flow project financing model we’ve proposed here) that your management will already understand. You can use these to build your case for intelligence.Focus on the benefits. If you really get stuck on the hard benefits, make sure you do a really thorough job on thinking through the soft ones.Practice thinking like a businessperson. Intelligence professionals are usually very good at finding information — but not always so good at realizing what it means for the value of the business.Don’t make promises you can’t keep. Absurdly high claims for value will catch up to you and will tarnish your credibility.KMWorld 2023 Sees a Sea Change by Michael E.D. KoenigA topic that appeared in 2022, in a very prescient KMWorld presentation by Tim Powell, was zombie knowledge. Zombie knowledge is material that is dated, or no longer correct or relevant, which clutters up or degrades your KM system. One of the concerns that arose frequently in 2023 was that, with GenAI, the need arises to recognize and correct hallucinatory information — the false and misleading information that it creates and propagates. Such “knowledge” can not only be misleading, but even dangerous. It was seen as obvious that dealing with hallucinations is a nontrivial problem, and that it will require the same techniques that are appropriate for zombie knowledge.

Put another way, GenAI can be expected to enormously expand the domain of and the problem with zombie knowledge. Powell referred to the potential of GenAI to be an industrial-strength disinformation machine, potentially creating reams of zombie data and purported knowledge, which would need to be recognized and dealt with.

Fourth stage of KM revealed at the KMWorld conference by Michael E.D. KoenigZombie knowledge

The most intriguing new entrant in this year’s conference was the concept of “zombie knowledge” — how to recognize it and respond to it. Zombie knowledge is what is in your KM system but is no longer useful, pertinent, or even accurate. It is zombie-like because it is built from what was live and valid information, but as information that has not died as it should have, it is now capable of behaving malignantly. And, even if nonmalignant, it is noise and clutter that distracts and impedes the system. Maintaining and providing such information is often counterproductive. How should such information be identified and handled?

Explicit recognition of the zombie notion apparently originated in a conversation in the SIKM Leaders Community last January, catalyzed by a phrase tossed out by Patrick Ready, KMS Lighthouse, and seized upon by Jane Dysart, KMWorld conference chair, and Tim Powell, The Knowledge Agency. The topic was bookended at the KMWorld conference by a workshop led by Powell on Monday and a presentation by Patrick Lambe, Straits Knowledge, on Thursday.

The corollary issues that derive from zombie knowledge are fascinating. How do you monitor the accuracy and pertinence of what is in your KM system? This is certainly an issue, even just for routine information. The zombie knowledge concept, however, is broader. For tactical and strategic information, it becomes far more compelling. Knowledge is certainly not simply facts and data; it is also corporate culture and how-to knowledge. Does this how-to knowledge include corporate strategy? Does this mean that a role for KM is, or should be, to monitor corporate strategy? This is not a role that most KM managers have contemplated or anticipated.

Interestingly and insightfully, the new ISO standard on KM, if not explicitly recognizing this issue, provides a place for it. ISO Standard 9001:2015, clause 7.1.6, breaks the KM process down into four steps. Powell parsed it this way: Determine, Maintain, Provide, Refresh. The choice of the term “refresh” seems clearly to imply more than just adding what is new. It also implies the housekeeping of removing what is old and stale before it becomes a dangerous malignancy.

Conferences and CommunitiesKMWorld Conference2023 C303: Knowledge Supply Chains: Governance2022 W18: Knowledge Dynamics: Strategies to Avoid Enterprise Knowledge Turning Zombie2021 A304: The Value of KnowledgeInfoToday2003 W17: The Knowledge Value Chain2001: KnowledgeNets E301: Ten Myths About KM Processes and ImplementationsSIKM Leaders CommunityPostsPresentation: The Value of Knowledge: A quick flyover, and introducing Knowledge Resources Management (KRM)VideosYouTubeChannelThe Value of Knowledgehttps://medium.com/media/e93e778bbe549e09772be343c8e3747f/hrefThe Purpose of Knowledgehttps://medium.com/media/5c9d31cccd400d757dff3a841e413f79/hrefInterviewed by Kendra Albright — Part 1https://medium.com/media/e5de0b10b41895b1566d4a6fdf0bc0c7/hrefInterviewed by Kendra Albright — Part 2https://medium.com/media/859cc7feb1290aca626062e5a00cbf92/hrefWhy Knowledge is Often Undervaluedhttps://medium.com/media/fd5737f7cec868577fb497efe78ca6d9/hrefEffective Knowledge Transfer Must Be Personalizedhttps://medium.com/media/52d5ea6d791b0e09de448af713656541/hrefThe critical role that knowledge playshttps://medium.com/media/4e4e27ea69e99f76376cf53a91f6ef8e/hrefUnlocked: Interviewed by Madelyn Blair BooksThe Value of Knowledge: The Economics of Enterprise Knowledge and Intelligence

BooksThe Value of Knowledge: The Economics of Enterprise Knowledge and Intelligence

Book Structure

Section 1 — Introduction. What is the book’s purpose (i.e., its overall value proposition)? Who are the intended audiences, and how can each put its contents to use? I’ll draw some key taxonomic distinctions and definitions and offer some notes to clarify the scope of what I will cover.Section 2 — Knowledge as an Enterprise Function. Most of you reading this are working in knowledge services or related fields– or studying and planning to do so. Why do organizations create budgets and jobs for such activities? What purposes does knowledge serve in the modern enterprise?Section 3 — Knowledge as an Economic Resource. The idea that knowledge is an essential economic resource is a relatively new one. Where did it arise, and why? Is knowledge fully recognized as a resource, or is there still work to be done?Section 4 — The Knowledge Value Chain®. The KVC framework has evolved into a sort of “skeleton key” that opens the rest of my work. I have lectured on it around the world for over two decades and published one major monograph and many articles and blog posts about it. How does it work? How can it be applied? What value does it add?Section 5 — Increasing Knowledge ROI. My goal in teaching you about how the value of knowledge works is to enable you to recognize and capital ize on new opportunities to do so. How is knowledge ROI measured? What levers can we push to increase its value? How can we balance economic and societal value?Section 6 — Knowledge to Value. Some organizations generate so much knowledge that they can productize or even monetize that knowledge. How do you sell knowledge? What are the steps and resources needed to do this? How do you build a business case for knowledge?Section 7 — Knowledge Strategy. If, by this point in your journey, you have come to believe that knowledge is a key economic resource and is in fact the key resource to compete effectively in the Knowledge Era– as I have– then you will see the connection between knowledge and enterprise strategy. They achieve their maximum impact when they are closely integrated. How is this best accomplished? What are the advantages of doing this?Appendix — Presented here are two model question sets, one for Producers of knowledge, the other for Users. Also included is an index of more than two dozen strategies for adding value and a list of major findings presented in the text.Bibliography — Decades ago, I began reading and collecting books and articles on topics related to the value of knowledge. I am glad to pass along these references that will enable deeper dives and further research into many of the areas covered hereinCore Propositions — The Value of Knowledge

Enterprise is fundamentally a human activity — of people, by people, and for people. Organizations are composed of people making individual and group decisions under uncertainty and exhibit the strengths and weaknesses of human cognition and behavior.Knowledge and information are fundamentally different. All knowledge is tacit, organic, and dynamic. Information is the explicit, inorganic, static manifestation of knowledge.Knowledge is an economic resource — it has costs and benefits. Knowledge value describes the relationship between knowledge costs and knowledge benefits.Knowledge generates actualized enterprise value only in being applied. Prior to being used or applied, knowledge has potential value. The actualized value generated by knowledge is inversely proportional to the distance (in time and space) between its production and its use.The value of knowledge is stakeholder-centric and stakeholder contextual. Different users for a knowledge element may value it in different ways and to different degrees.Knowledge is not power. Knowledge must work within the power structure, rules, strategies, and metrics of the enterprise.Knowledge value development is a process that occurs in time and that consumes resources. It has a series of gated steps and a beginning, a middle, and an end.Knowledge strategies scale. Value principles that apply at a macro level (e.g., the enterprise) may be applied at a micro level (e.g., the work product), and vice versa.Knowledge represents the majority of enterprise value in many industries — yet it rarely shows up in formal financial statements.Value is dynamic and is affected by a number of ever-changing factors. Value propositions must be continually calibrated, refined, and aligned.The Knowledge Value Chain® Handbook The High Tech Marketing Machine: Applying the Power of Computers to Out-Smart the Competition

The High Tech Marketing Machine: Applying the Power of Computers to Out-Smart the Competition Analyzing Your Competition: Its Management, Products, Industry and Markets

Analyzing Your Competition: Its Management, Products, Industry and Markets Book Chapters

Book ChaptersKnowledge Management Lessons Learned: What Works and what Doesn’t edited by Michael E. D. Koenig and T. Kanti Srikantaiah

Chapter 9: Knowledge Return on InvestmentChapter 16: The Knowledge Matrix: A Proposed Taxonomy

The Art and Science of Business Intelligence Analysis Part B: Intelligence Analysis and Its Applications edited by Ben Gilad and Jan P. Herring

Chapter: Analysis in Business Planning and Strategy Formulation[image error]May 2, 2025

Knowledge Management Thought Leader 111: Luis Suarez

Luis Suarez is a Co-Founder of asynco, an international community of practice to help shape the future of distributed and asynchronous work. He previously spent 18 years at IBM. He has helped organizations make the most of their change management initiatives and digital transformation programs through social digital tools as key enablers.

Luis is a self-described community builder, social business strategist, wirearchist, digital humanist, no-email pioneer, blogger, and flaneur. He specializes in knowledge management, collaboration, learning, online communities of practice, remote and distributed work, and social networking for business. His skills include community building, online social networking, and enterprise social networks.

Here are definitions for five of Luis’s specialties:

Collaboration : Interacting with peers and colleagues to exchange ideas, share experiences, work together on projects, and solve problems. Communities : Groups of people who share an interest, a specialty, a role, a concern, a set of problems, or a passion for a specific topic. Community members deepen their understanding by interacting on an ongoing basis, asking and answering questions, sharing their knowledge, reusing good ideas, and solving problems for one another. Distributed Work : Work done at organizations with employees in different physical locations.Learning: The act of gaining knowledge from others, from existing information, and by doing. It is one of the five basic activities of knowledge management. Social Networks : Collections of people who are acquainted or connected as friends, business contacts, or colleagues and communicate, collaborate, or help one another as needed.Luis created the following content. I have curated it to represent his contributions to the field. For more about Luis, see Profiles in Knowledge.

Community: asynco

Community: asynco

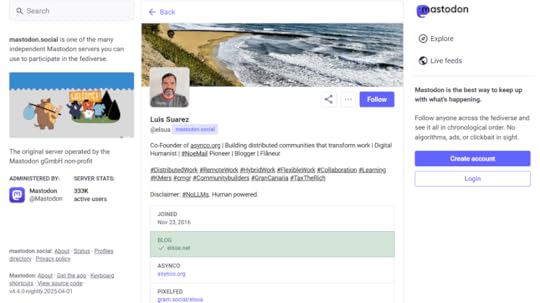

Social Networking in the Fediverse

Social Networking in the FediverseMastodon

Pixelfed

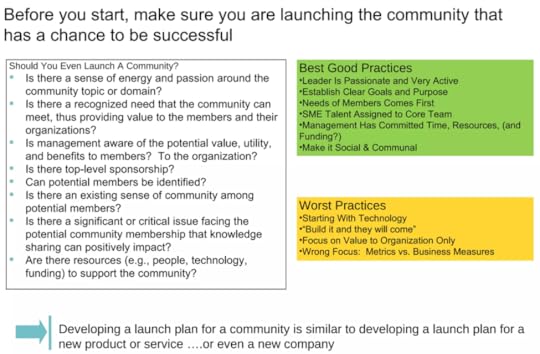

Community Roles and Adoption Planning

Community Roles and Adoption Planning

Becoming a Jedi Master: The secret art of cultivating online communities

Becoming a Jedi Master: The secret art of cultivating online communities

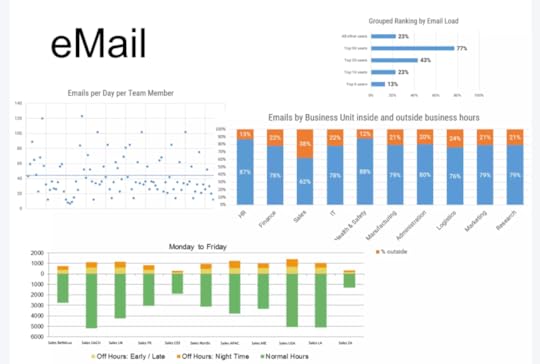

The Impact of Data Analytics in Digital Transformation Programs

The Impact of Data Analytics in Digital Transformation Programs [image error]

[image error]

April 25, 2025

Knowledge Management Thought Leader 110: Tom Stewart

Tom Stewart is a strategist, senior executive, and one of the thinkers who discovered and developed the concepts of knowledge-based businesses, and the role of intellectual capital and thought leadership in strategy. He is an experienced research center leader, book author, business journalist, publishing executive, and C-suite marketing and knowledge management leader.

Tom held positions as the Editor-in-Chief of the Harvard Business Review, Chief Marketing & Knowledge Officer of Booz & Company, and Executive Director of the National Center for the Middle Market. Previously, he had senior roles at Fortune and in book publishing.

Here are definitions for five of Tom’s specialties:

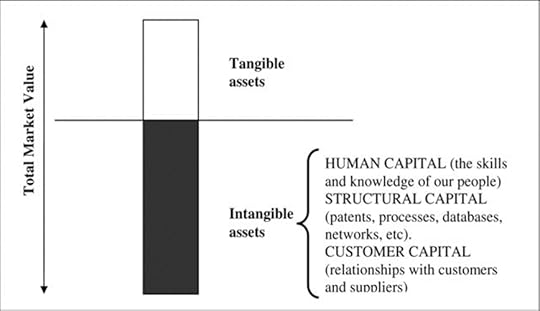

Content Management : Creating, managing, distributing, publishing, and retrieving structured information–the complete lifecycle of content as it moves through an organization.Digital Transformation: The cultural, organizational, and operational change of an organization, industry, or ecosystem through a smart integration of digital technologies, processes, and competencies across all levels and functions in a staged and strategic way. Innovation : The process by which an idea is translated into a good or service for which people will pay. Intellectual Capital : The sum of everything everybody in a company knows that gives it a competitive edge. A metric for the value of intellectual capital is the amount by which the enterprise value of a firm exceeds the value of its tangible (physical and financial) assets. It includes human, structural, and relational capital.Strategy: A set of guiding principles that, when communicated and adopted in the organization, generates a desired pattern of decision making. The way that people throughout the organization should make decisions and allocate resources to accomplish key objectives. A strategy provides a clear roadmap that defines the actions people should take (and not take) and the things they should prioritize (and not prioritize) to achieve desired goals.Tom created the following content. I have curated it to represent his contributions to the field. For more about Tom, see Profiles in Knowledge.

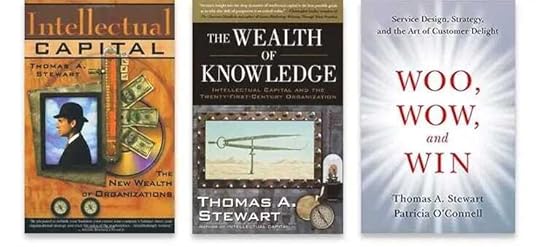

Books by Tom Stewart

Books by Tom Stewart Excerpt from Intellectual Capital, Preface to the Paperback Edition

Excerpt from Intellectual Capital, Preface to the Paperback EditionToo much of what passes for knowledge management is just glorified data processing. On page 71 of this book, I briefly distinguish between intellectual capital and intellectual working capital. This distinction was a new idea to me–it came to me while I was working on the proofs of the book. In the past eighteen months, I’ve come to think it’s a valuable distinction, and especially important to keep in mind as knowledge management becomes the rage. Intellectual working capital is workaday information–the flow or torrent of data, facts, meter readings, and so forth. Of this stuff, I wrote, “A worker might need precise, up-to-date information at any given moment, but not necessarily at this moment. What he does need, at every moment, is a way to get the data he might need at any moment.”

Implicit in those somewhat knotty sentences is a truth that might be lost in some corporations’ full-throttle rush to “do” knowledge management. Intellectual working capital should not be managed the same way as intellectual capital. It wants different aims, different measurements, and possibly different means. These pieces of information are to the New Economy what inventory and receivables are to the Old Economy. Working capital is a Bad Thing. It is a cost to be minimized, not an asset whose value should be increased. It is not to be stored but to be kept moving. Intellectual working capital is a through-put, cycle-time, inventory-management problem.

Knowledge management advocates correctly decry the wastefulness of constantly “reinventing the wheel”; one way to do that is to create a digital warehouse in which is stored every wheel anyone has ever invented. But that dream–the dream of a corporate master file, an encyclopedia where every needed fact, every policy, every conceivably valuable piece of knowledge can be found with just a few clicks of the mouse–is both impractical and wrong. Impractical because technology and markets are changing so quickly that it would be impossible to possibly create such an omnium-gatherum of corporate brainpower, unless one is willing to spend such enormous amounts of money setting up and maintaining the encyclopedia that it will not be worth the effort. Wrong because that’s not the right way to do warehousing–unless your company’s value proposition is to be a storehouse for knowledge, as a silo is for grain. One wants the smallest possible warehouse, which stocks only what’s otherwise hard to get in a timely way. Knowledge management and knowledge databases should really be about linking people to people to serve customers, people needing expertise with people who have expertise. They should be about connection, not collection.

I see a second mistake being made by advocates of knowledge management. Too often they focus inside companies. Much of knowledge management has been an inside job, automating and animating the files. It’s hyperlinked, hypersonic librarianship. Too little is about serving customers. Consultant Stan Davis points out that business people frequently confuse an organization with a business. Organizations are defined from the inside out: They are described by who reports to whom, by departments and processes and matrices and perks. A business, on the other hand, is defined from the outside in, by markets, suppliers, customers, and competitors.

There is money to be saved by improving knowledge management in the organization. But there is money to be made by managing the knowledge of the business. What is the knowledge customers are paying for? Real customers–not phony “internal customers” but people with money in their hands? It’s their money that is important, not the money the budget committee has allocated to knowledge management.

Excerpt from The Wealth of Knowledge, Chapter 1: The Pillars of the Knowledge EconomyThe knowledge economy stands on three pillars. The first: Knowledge has become what we buy, sell, and do. It is the most important factor of production. The second pillar is a mate, a corollary to the first: Knowledge assets–that is, intellectual capital–have become more important to companies than financial and physical assets. The third pillar is this: To prosper in this new economy and exploit these newly vital assets, we need new vocabularies, new management techniques, new technologies, and new strategies. On these three pillars rest all the new economy’s laws and its profits.

Knowledge is what we buy, sell, and do.

It has become traditional in books about knowledge and knowledge management to spend several pages defining knowledge and distinguishing it from data, information, and sometimes wisdom. I feel no need to inflict any such rumination on you, dear reader; dictionaries and common usage are good enough. But it is–I have always maintained–important to make a distinction between data and information, on the one hand, and knowledge, on the other.

Data and information are smaller than knowledge and, if it exists, wisdom. They are also different in kind. In computerese, eight bits equal one byte. But eight–or zubleteen zillion–bits of information do not equal a byte of knowledge. Knowledge is not a sum but a summation, a relation. Data and information plug into knowledge: They are tiles in a mosaic, but they are not its design. Bits of data and information–facts, factoids–can be startling or telling or important, but they’re not like knowledge.

Knowledge involves expertise. Achieving it involves time. It endures longer than information–sometimes forever. To be knowledgeable, to know a subject, is something different from and greater than knowing a fact or possessing a lot of information about something.

It is impossible, however, to make a clear distinction between information and knowledge that works for a very large group. This is because one man’s data can be another man’s knowledge, and vice versa, depending on context. Your deep expertise in accounting, metallurgy, or literature may be an interesting tidbit to the person you sit next to at dinner tonight. Therefore what’s information and what’s knowledge depends on context.

If this were a study of epistemology or information theory, we might want more precise definitions, but it’s not and we don’t.

The Intellectual Capital Model [image error]

[image error]

April 18, 2025

Knowledge Management Thought Leader 109: Dave Snowden

Dave Snowden is the Founder and Chief Scientific Officer of The Cynefin Company. His specialties include Sense-Making, Knowledge Management, Complexity Science applied to organizations, and Narrative.

Dave works on the application of natural sciences to social systems through the development of a range of methods and software. He is the creator of the Cynefin Framework and originated the design of the SenseMaker® software suite, the world’s first distributed ethnography tool.

Dave has pioneered a science-based approach to organizations, drawing on anthropology, neuroscience, and complex adaptive systems theory. He believes that using natural science as a constraint on the understanding of social systems avoids many of the issues associated with inductive or case-based approaches to research. A self-described “proud curmudgeon and pragmatic cynic,” Dave is well known for his iconoclastic style.

Here are definitions for five of Dave’s specialties:

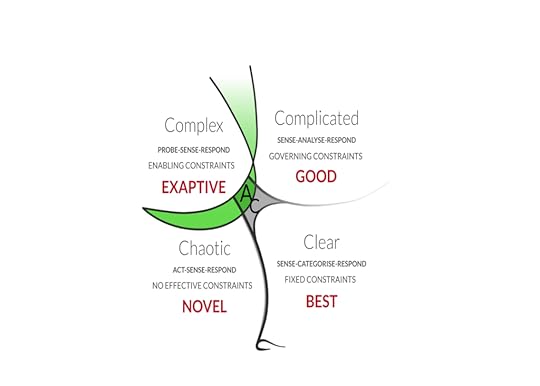

Complex adaptive system: An entangled system where everything is connected to everything else, and we may or may not know how they are interconnected and are constantly changing. A complex adaptive system is also an inherently unknowable system, with no linear material causality.Cynefin (pronounced kuh-nev-in): A Welsh word for habitat that signifies the multiple, intertwined factors in our environment and our experience that influence us (how we think, interpret and act) in ways we can never fully understand. The Cynefin Framework is a conceptual framework used to aid decision-making and is described as a sense-making device. It helps managers to identify how they perceive situations and make sense of their own and other people’s behavior. The framework draws on research into systems theory, complexity theory, network theory, and learning theories.Emergence: Work processes that evolve in real time, in which the outcomes are not predictable, and employees must continuously make sense of, and adjust to, a changing situation. It is generally accepted that new product development, customer service, or any knowledge process conducted in a dynamically changing marketplace must be an emergent one if a company is to turn unpredictability to its competitive advantage. Narrative : A story that you write or tell someone, usually in great detail. The process of collecting anecdotes from people about how they actually do work to make sense of what is really going on in an organization.Sense-making: The process of creating situational awareness and understanding in situations of high complexity or uncertainty in order to make decisions. It is a motivated, continuous effort to understand connections (which can be among people, places, and events) in order to anticipate their trajectories and act effectively.Dave created the following content. I have curated it to represent his contributions to the field. For more about Dave, see Profiles in Knowledge.

Books by Dave Snowden

Books by Dave Snowden Cynefin Framework

Cynefin FrameworkThe Cynefin Framework was developed to help leaders understand their challenges and to make decisions in context. By distinguishing different domains (the subsystems in which we operate), it recognises that our actions need to match the reality we find ourselves in through a process of sense-making. This helps leaders cultivate an awareness of what is really complex and what is not and respond accordingly so that no energy is wasted in overthinking the routine but they also never try to make the complex fit into standard solutions.

The Cynefin Framework is and has been used in almost every conceivable sector: whether strategy, police work, international development, public policy, military, counterterrorism, safety, energy, healthcare, sales or education it has had something to offer. In this video, Dave Snowden introduces the Cynefin framework with a brief explanation of its origin and evolution and a detailed discussion of its architecture and function.

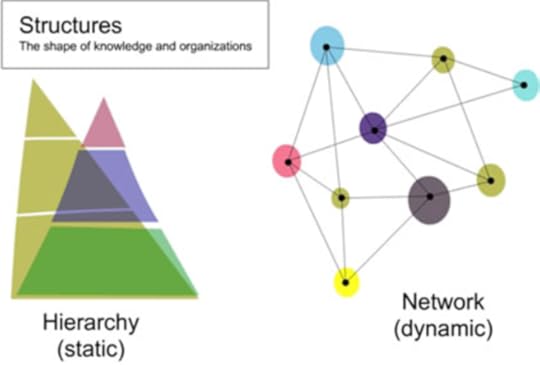

Three basic principles of system design, informed by complexity theoryDistributed cognition means far more than the more popular phrase “wisdom of crowds,” which is a misnomer because crowds can be more foolish than wise. Distributed cognition means using network intelligence. The classic example is the Grameen Bank or micro-lending, with self-forming lending groups determining loan allocation rather than centralized credit scoring. In the context of modern management practice, that means the top-down stimulation of bottom-up activity. It’s not about delegation per se, or the absence of management, but it is about using the capacity of diverse networks to contribute to decision-making and system design; shifting the analyst from prime investigator and interpreter to a role of synthesis; and allowing systems to emerge through the interaction of people with software, rather than designing that use in advance.Finely granulated objects have more utility than chunked up documents (information) or massive organizational empires. (That is the meaning behind this column’s title, Everything is Fragmented.) The basic idea is simple: Small things are more adaptable than big things, and they are frequently more interesting and more able to gain our attention. People will spend more time surfing the Web and using the fragmented material of an RSS feed than reading documents. It’s easier to write a blog than a book. Fine granularity material can combine in novel and different ways more easily than formal documents. Fragmented stories of partial failure create more learning than formal documents summarizing best practice. Fragmented material can combine and recombine in novel and different ways, a form of conceptual blending. In organizations, small, self-forming teams are more adaptive than matrix structures. Networks adapt faster than hierarchies.Disintermediation is one of those interesting words that border on jargon, but it is too useful to abandon. It means removing the layers that separate decision makers from raw data — allowing them to move from an abstract representation of a large data set, spot patterns and anomalies, and focus on the five or six items to which they really need to pay attention. There is an ethical dimension to this too. When people encounter real stories/pictures, etc., they are far more likely to gain empathy and understanding, and therefore make more contextually aware decisions.Volunteer not conscript

Three basic principles of system design, informed by complexity theoryDistributed cognition means far more than the more popular phrase “wisdom of crowds,” which is a misnomer because crowds can be more foolish than wise. Distributed cognition means using network intelligence. The classic example is the Grameen Bank or micro-lending, with self-forming lending groups determining loan allocation rather than centralized credit scoring. In the context of modern management practice, that means the top-down stimulation of bottom-up activity. It’s not about delegation per se, or the absence of management, but it is about using the capacity of diverse networks to contribute to decision-making and system design; shifting the analyst from prime investigator and interpreter to a role of synthesis; and allowing systems to emerge through the interaction of people with software, rather than designing that use in advance.Finely granulated objects have more utility than chunked up documents (information) or massive organizational empires. (That is the meaning behind this column’s title, Everything is Fragmented.) The basic idea is simple: Small things are more adaptable than big things, and they are frequently more interesting and more able to gain our attention. People will spend more time surfing the Web and using the fragmented material of an RSS feed than reading documents. It’s easier to write a blog than a book. Fine granularity material can combine in novel and different ways more easily than formal documents. Fragmented stories of partial failure create more learning than formal documents summarizing best practice. Fragmented material can combine and recombine in novel and different ways, a form of conceptual blending. In organizations, small, self-forming teams are more adaptive than matrix structures. Networks adapt faster than hierarchies.Disintermediation is one of those interesting words that border on jargon, but it is too useful to abandon. It means removing the layers that separate decision makers from raw data — allowing them to move from an abstract representation of a large data set, spot patterns and anomalies, and focus on the five or six items to which they really need to pay attention. There is an ethical dimension to this too. When people encounter real stories/pictures, etc., they are far more likely to gain empathy and understanding, and therefore make more contextually aware decisions.Volunteer not conscriptIf you ask someone, or a body, for specific knowledge in the context of a real need it will never be refused. If you ask them to give you their knowledge on the basis that you may need it in the future, then you will never receive it.

Three rules or heuristics of Knowledge Management

Knowledge will only ever be volunteered; it cannot be conscripted.We only know what we know when we need to know it.We always know more than we can tell and we will always tell more than we can write down.What puzzles me is this. Despite the fact that people agree with these, they still design idealistic systems on the assumption that this time the rules will not apply.

It appears that we can know something without necessarily learning from it.

[image error]April 17, 2025

Brittany Persinger: Profiles in Knowledge — Rising Stars Series

This is the 114th article in the Profiles in Knowledge series featuring thought leaders in knowledge management and the second in the Rising Stars Series. Rachel Teague suggested this series and is my co-author on this article.

Brittany Persinger is a KM specialist with a decade of experience currently working to help drive KM excellence in the UN currently based in Amman, Jordan. She specializes in capacity building, communities of practice, community management, content curation, editing, knowledge management, learning, and project management.

Background In her own words

In her own wordsWhen people ask what I do, I tell them I’m a matchmaker for tools/solutions. I’m an experienced knowledge manager with a passion for taking KM into the future. I currently manage a KM team with the shared vision of using organizational knowledge to make better decisions, increase efficiencies, and improve how work happens. I’ve also developed KM action plans, facilitated virtual and in-person workshops on how to keep Communities of Practice thriving, and used my research and digital content curation skills to build up knowledge bases, make informed arguments for program adaptation, and highlight ways to use technology to share information.

EducationUniversity of Bradford — Master of Arts with Merit Honors, Peace StudiesMessiah University — Bachelor of Arts, Political ScienceExperienceWorld Food ProgrammeHead (OIC), Knowledge Management and Library Unit, 2024 — PresentKnowledge Management Officer, 2023–2024World VisionManager, Knowledge Management, 2020–2023Knowledge Management Advisor, 2017–2020Search for Common Ground — Consultant, 2016–2017Inclusive SecurityKnowledge Management Associate, 2016Program Associate, National Action Plans, 2012–2016Advocacy Associate, 2012ProfilesLinkedInTwitterFacebookKnowledge Management for DevelopmentContentThe Britt BlogInclusive SecurityWFP Innovation AcceleratorThe secret to impactful innovations? Strong Knowledge ManagementLeveraging academic expertise: Students of Vienna University of Economics & Business support WFP’s innovation mission through AI-driven solutions with Julia DaliborConferencesKnowledge Summit Dublin 2025- June 24, 2025: From Urgency to Impact: Harnessing Knowledge for Life-Saving Humanitarian Work — with Davorka GaragicAPQC 2020 KM ConferenceLife After Love: What Happens After CoPs Fail? Keynote presentation on how to keep Communities of Practice from failing — with Sara Crass

https://medium.com/media/cda561f7fb6e3c68db49bf238f7c55bc/hrefhttps://medium.com/media/62c2c24edda5bbb623155ed715b0234b/hrefBuilding KM Skills with Cindy Hubert, Johel Brown-Grant, and Jennifer Hawkins

https://medium.com/media/1dde948423840cfee972da07d6b3cfcf/hrefThe April 2025 Rising Star Interview by Rachel TeagueThough I had known of Brittany through mutual KM circles, I was fortunate enough to meet her for the first time at Knowledge Summit Dublin in June of 2024. Brittany was a breath of fresh air to connect with — someone who balanced both a healthy dose of idealism and realism while simultaneously rolling up her sleeves and asking where we could start. From day one I knew that I had found a new thought partner and friend in KM to share ideas with, dissect problems, and work collaboratively to find solutions. Even if she didn’t have the answer or ability to get it done, she knew where to point me. Having the opportunity to sit and to learn more about Brittany’s journey in KM was enlightening and I genuinely enjoyed the conversation. She is a light in our community and uses her voice to help others amplify theirs.

What led you into the field of KM, and why are you passionate about it?

I didn’t set out to work in knowledge management — I kind of stumbled into it, like a lot of us do. My background is in political science and peacebuilding, and early in my career I was more focused on policy and advocacy. In 2012, I was working at a women and peacebuilding think tank in D.C., and I found myself less interested in tracking Congressional activity and more drawn to building internal systems — documenting lessons learned, curating resources, setting up structures for sharing information. At one point, I literally Googled the kinds of things I was doing to figure out what this role even was. “Knowledge management” popped up, and it was one of those lightbulb moments where I was like — oh, this is what I do. That moment shifted the course of my career.

What makes me passionate about KM is that it taps into the way I naturally approach problems. I’ve always been someone who sees patterns, who likes connecting the dots and bringing clarity to messy situations. KM gives me a way to solve big, complex problems in a way that feels intuitive — especially working in spaces like the UN, where the problems are big. I can see how the pieces fit together, and then the challenge becomes helping others see it too — bringing people along for the journey, making the complex feel understandable. That’s what energizes me about this work. It’s not just about organizing information — it’s about driving impact through clarity and connection.

What are your specialties ?

My core specialties are knowledge retention and transfer, communities of practice, and strategy development. I also really love facilitating — whether that’s virtual or in-person learning spaces. There’s something so rewarding about creating environments where people can connect, share, and experience those “light bulb” moments together.

I’ve been remote for a long time, but in-person facilitation and public speaking are still strengths I bring to the table. I’m especially drawn to collaboration spaces — things like knowledge cafés or communities of practice — where I can help people feel heard, make sure things move forward, and really nurture those connections. It’s kind of funny, because if you asked me if I’m a “people person,” I’d probably say no. But I am really good at facilitating networks and creating structure around how people engage and share.

On the strategy side, that’s where I get to fully nerd out. I love the days where I can just sit down, brain-dump everything into an action plan, sketch out frameworks, build templates — really dig into the process. Strategy isn’t just one document; it’s buy-in, implementation, monitoring, and making sure it all works together. That kind of systems thinking is something I find energizing.

Who are your influences, and why?

I’ve learned a lot from John Hovell, who facilitated my CKM course back in 2018 and has been a mentor and friend ever since. I’ve also had the honor of working alongside Chris Collison and learning from his decades of experience. What I’ve gained from both of them goes beyond technical KM expertise — it’s also about how they lead with relationships, inclusion, and trust. From day one, they treated me like an equal, even though they had years (decades, really) of experience on me. That kind of respect and openness made a huge impact.

Watching how they engage with people — how they listen, facilitate, and create space for collaboration — has shaped the way I think about KM. Yes, we need systems and strategy, but people are at the heart of all of it. And in a field that’s still evolving, I think it’s essential that we make room for “nextperts” — for new voices, emerging perspectives, and people who bring different lived experiences into the conversation. That’s how we grow. That’s how we keep KM relevant in a world that’s changing fast. I feel lucky to have had mentors who modeled that so clearly.

If you could only implement one component as part of a KM program, what would it be, and why?

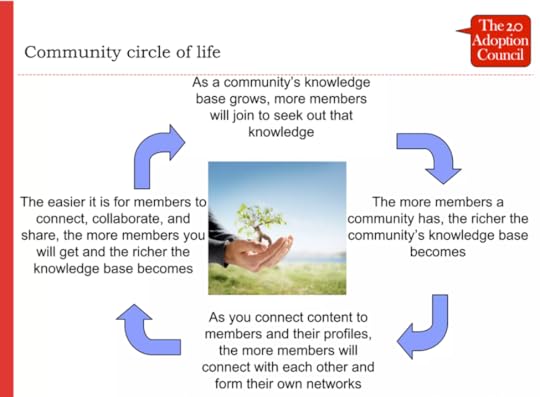

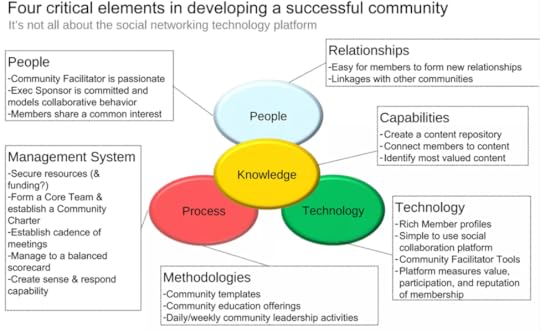

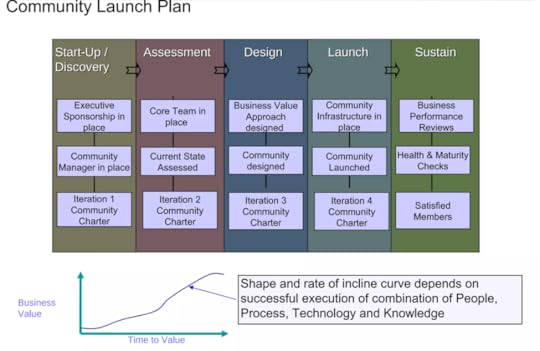

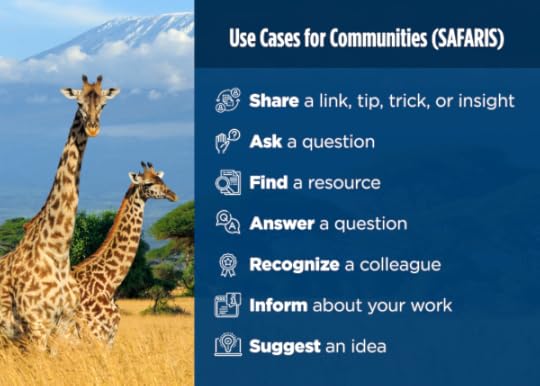

Communities — without question. If I could only implement one component of a KM program, it would be communities of practice. I’ve seen firsthand how powerful they can be as catalysts for collaboration, especially across functions and regions. They’re spaces where learning is shared, where people connect, and where knowledge actually gets re-applied — not just documented and forgotten.

At WFP, we are really leaning into this by working to layer our communities into different types: true communities of practice, communities of interest, and then those more practical spaces where country offices can just exchange information. We feel that structure will help ensure we’re meeting people where they are — whether they’re deep subject matter experts or staff just trying to figure things out on the ground.

Communities are never a silver bullet, but when done well, they move the needle in so many areas — knowledge retention, collaboration, visibility of expertise, even culture. They create the connective tissue across an organization, and that, to me, is one of the most valuable things KM can offer.

What is your vision for a successful KM program?

For me, a successful KM program is one where knowledge is actively flowing across the organization — not just being stored somewhere, but actually moving. What’s being learned over here is known and applied over there if it’s relevant. There are systems and connection points in place to make that happen, and it all works seamlessly enough that most people don’t even realize KM is at play — they just feel like things work.

I often compare it to good design. You don’t notice good design — you notice when it’s bad. It’s the same with KM. When it’s working, people find what they need when they need it, they know who to go to, and they can make better decisions because of it.

In an ecosystem like the UN, that means connecting learning across global programs, across contexts, and ensuring that we’re not just collecting knowledge for the sake of it. We’re using it — to adapt, to respond, to plan smarter. That means investing in the right people, the right tech, and the right culture. It means leadership can speak to the value of KM, even if they don’t use the term explicitly. It means we have systems that surface expertise, that support cross-pollination, and that enable real-time problem-solving.

Ultimately, KM should help us make better, faster, and more strategic decisions — not just in the moment, but over time. And in a humanitarian context, that can literally be the difference between life and death. So when I think about success, it’s not about flashy tools or perfect frameworks. It’s about building something that works — and that leaves the program, the team, or the organization better than you found it.

What are you most proud of in your career so far?

I think what I’m most proud of is that in every KM role I’ve held — whether at WFP, World Vision, or other organizations — I’ve been able to leave the program better than I found it. Sometimes that’s meant improving systems or tools, and other times it’s been about laying a foundation where one didn’t exist. But in each case, I’ve seen real growth in how knowledge is managed and valued.

One thing I’m especially proud of right now is the upcoming revised KM strategy at WFP. It’s been almost a year in the making, with interviews, collaboration, alignment, and a whole lot of thinking and refining. To have contributed and put my stamp on it feels significant.

What’s been even more encouraging is the response. We’re seeing more teams reaching out, asking how they can align with the strategy and wanting to be part of it. That tells me something is shifting — that the value of KM is becoming more visible and more tangible. It’s not just about a document, it’s about momentum. And while it’s absolutely a team effort, being part of that shift is something I’m genuinely proud of.

I’m also proud that in December 2024, WFP was honored as one of the recipients of the 2023/2024 Global Knowledge Management Award, given by Knowledge Management Austria and the Knowledge for Development Partnership (K4DP). It was the first time WFP has received this kind of global recognition for KM. It’s a testament not only to the work of members of our KM team over the years, but also to WFP staff across the globe who learn, share, and apply their knowledge every day to solve problems and save lives. That acknowledgment — and the collective effort behind it — means a lot.

What would you like to accomplish in the short term and long term?

Short term, I want to play a more strategic role in helping institutions like the UN take KM seriously — not just as a back-office function, but as a critical driver of impact. I don’t want visibility just to be on every conference stage. I want to be visible because I’m advocating for something that matters. When people think about KM in institutions that work directly with communities around the world, I want them to understand the value it brings — and I want to be a voice helping make that case clearly and consistently.

Long term, if I’m going to be known as a KM voice, I want to be known as a voice for change. This current period — with all its uncertainty and upheaval — has shown us that we can’t keep doing things the way we’ve always done them. KM needs to keep pace with the world around it. That means welcoming new perspectives, making space for different voices, and pushing the field forward in ways that are more inclusive, adaptive, and grounded in reality. If I can be part of that shift, that’s the kind of legacy I’d be proud of.

What are your top three knowledge nuggets/insights/lessons learned?

Good KM is like good design. You don’t notice when it’s working — you notice when it’s not. People tend to realize the value of KM only when something breaks down: no one knows who the expert is, key documents are missing, lessons aren’t being applied, and suddenly we’re wasting time, money, or worse. That’s why it’s so important to make KM visible and tangible before it becomes a problem. You shouldn’t have to wait for a fire to prove why fire extinguishers matter.Champions matter — especially at the right level. Having the right person in your corner can change everything, no matter how big or small your KM effort is. But you don’t get champions by tossing around KM jargon and hoping they care. You get them by connecting KM to what they care about — in their language, not yours. That strategic communication work upfront is what opens doors and gets buy-in.Be a knowledge storyteller. As KM people, we love our terminology — CoPs, knowledge audits, appreciative inquiry, you name it. And yes, there’s value in precision. But if we’re so busy holding onto the language that we lose our audience, what’s the point? Our job is to translate, to paint the picture in a way that resonates with whoever we’re speaking to. The message doesn’t have to be watered down — it just has to be understood. That’s how you create momentum. That’s how you bring people with you.What is something in the KM space you would like to learn more about?

I know there’s a lot of important work emerging around how to incorporate local and indigenous knowledge into AI initiatives — and I want to learn more about how to do that in a way that’s actually meaningful and not just lip service. The speed at which AI is advancing is staggering, and I don’t think the conversation around inclusion has kept pace. There’s a real risk that if we don’t intentionally design with a wide range of knowledge systems in mind, we’ll end up reinforcing the same narrow perspectives over and over again.

And right now, when terms like “inclusion” and “equity” are being politicized and pushed back on, it’s more important than ever to understand how to amplify diverse forms of knowledge in a tangible, grounded way. I don’t claim to have all the answers — but I want to be part of the learning and the action. I think KM has a real role to play here, and I want to deepen my understanding of how we show up for that work, especially in the context of emerging technologies like AI.

[image error]April 11, 2025

Knowledge Management Thought Leader 108: George Siemens

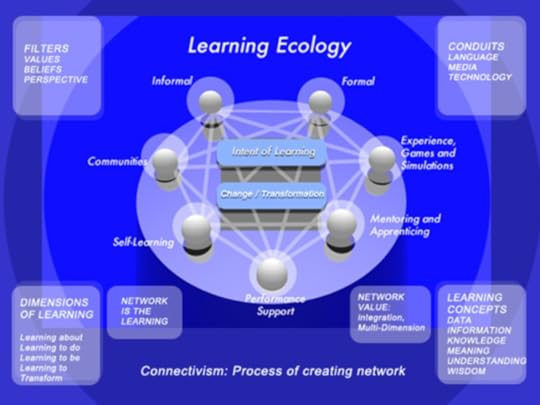

George Siemens is an author, researcher, and theorist in the fields of learning, knowledge management, and technology. He focuses on connectivism, MOOCs (Massive Open Online Courses), learning analytics, human and artificial cognition, and systems.

A professor at multiple universities, George’s research focused on how people learn and build knowledge in digital environments. This involved four key areas of exploration:

Sensemaking and technology in classrooms and online learning, resulting in proposing Connectivism as a theory of learning in social and distributed networks.The impact of systemic changes, such as open education, and how traditional assumptions of learning in classrooms are inadequate online, reflective of his research in Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs).The data that learners generate when engaged in digital environments. The research value of data in understanding learning and social and cognitive processes led him to found the Society for Learning Analytics Research, which became the largest academic organization internationally to support researchers working with learning and knowledge process data.How human and artificial cognition is changing society and how this intersection impacts how humans know and are intelligent.Here are definitions for five of George’s specialties:

Cognition: the sensory processes, general operations, and complex integrated activities involved in interacting with information. Sensory processes include vision, perception, and attention. General operations involve language, memory, recognition, recall, information seeking and management behaviors. Complex integrated activities include reasoning, judgement, decision making, problem solving, sensemaking, and creativity.Connectivism: the integration of principles explored by chaos, network, and complexity and self-organization theories. Connectivism is driven by the understanding that decisions are based on rapidly altering foundations. New information is continually being acquired. The ability to draw distinctions between important and unimportant information is vital. The ability to recognize when new information alters the landscape based on decisions made yesterday is also critical.Learning: actionable knowledge; it can reside outside of ourselves (within an organization or a database), and is focused on connecting specialized information sets, and the connections that enable us to learn more are more important than our current state of knowing. It is a process that occurs within nebulous environments of shifting core elements — not entirely under the control of the individual.Learning Analytics: the measurement, collection, analysis and reporting of data about learners and their contexts, for purposes of understanding and optimizing learning and the environments in which it occursMOOCs (Massive Open Online Courses): online courses aimed at unlimited participation and open access via the web. In addition to traditional course materials, such as filmed lectures, readings, and problem sets, many MOOCs provide interactive courses with user forums or social media discussions to support community interactions among students, professors, and teaching assistants, as well as immediate feedback to quick quizzes and assignments.George created the following content. I have curated it to represent his contributions to the field. For more about George, see Profiles in Knowledge.

Books by George Siemens

Books by George Siemens Not everything we call AI is actually ‘artificial intelligence’. Here’s what you need to know

Not everything we call AI is actually ‘artificial intelligence’. Here’s what you need to knowWhat does ‘AI’ actually mean?

To qualify as AI, a system must exhibit some level of learning and adapting. For this reason, decision-making systems, automation, and statistics are not AI.

AI is broadly defined in two categories: artificial narrow intelligence (ANI) and artificial general intelligence (AGI). To date, AGI does not exist.

The key challenge for creating a general AI is to adequately model the world with all the entirety of knowledge, in a consistent and useful manner. That’s a massive undertaking, to say the least.

Most of what we know as AI today has narrow intelligence — where a particular system addresses a particular problem. Unlike human intelligence, such narrow AI intelligence is effective only in the area in which it has been trained: fraud detection, facial recognition or social recommendations, for example.

AGI, however, would function as humans do. For now, the most notable example of trying to achieve this is the use of neural networks and “deep learning” trained on vast amounts of data.

Neural networks are inspired by the way human brains work. Unlike most machine learning models that run calculations on the training data, neural networks work by feeding each data point one by one through an interconnected network, each time adjusting the parameters.

As more and more data are fed through the network, the parameters stabilize; the final outcome is the “trained” neural network, which can then produce the desired output on new data — for example, recognizing whether an image contains a cat or a dog.

What does AI need to work?

AI needs three things to be successful.

First, it needs high-quality, unbiased data, and lots of it. Researchers building neural networks use the large data sets that have come about as society has digitized.AI also needs computational infrastructure for effective training. As computers become more powerful, models that now require intensive efforts and large-scale computing may in the near future be handled locally. Stable Diffusion, for example, can already be run on local computers rather than cloud environments.The third need for AI is improved models and algorithms. Data-driven systems continue to make rapid progress in domain after domain once thought to be the territory of human cognition.However, as the world around us constantly changes, AI systems need to be constantly retrained using new data. Without this crucial step, AI systems will produce answers that are factually incorrect, or do not take into account new information that’s emerged since they were trained.

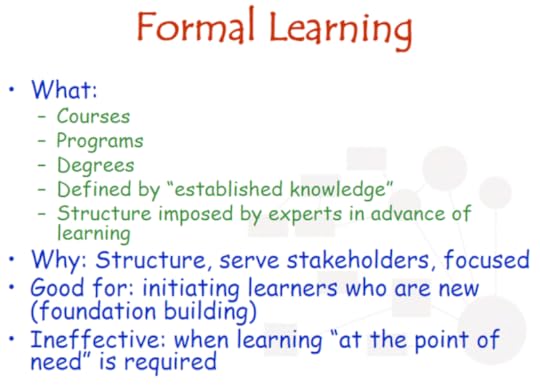

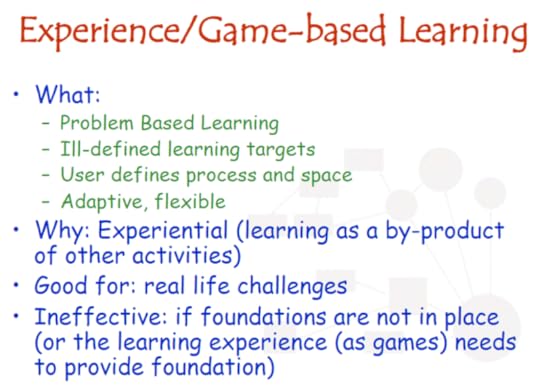

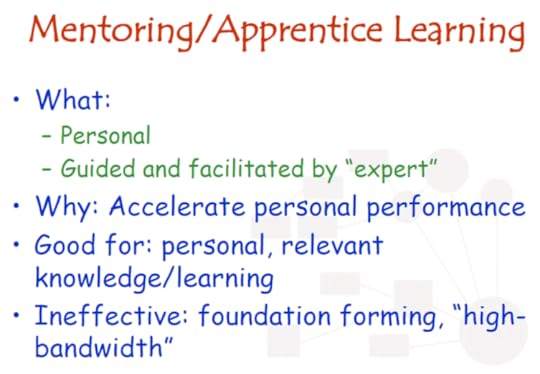

Learning in Context

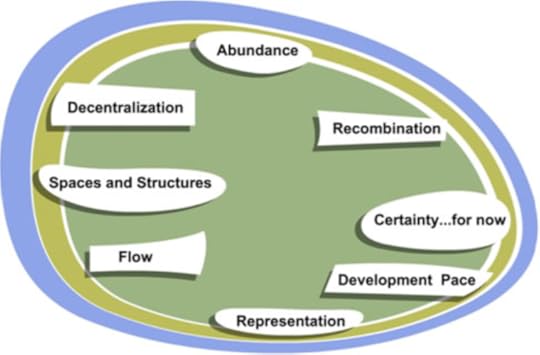

Changed Characteristics and Flow of Knowledge (in Knowing Knowledge)

Changed Characteristics and Flow of Knowledge (in Knowing Knowledge)Changes in Knowledge

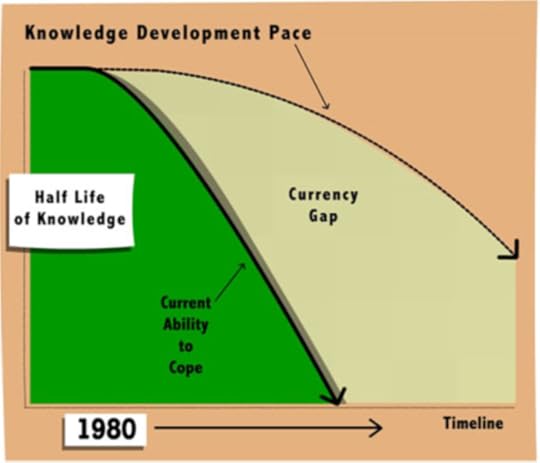

Half Life of Knowledge

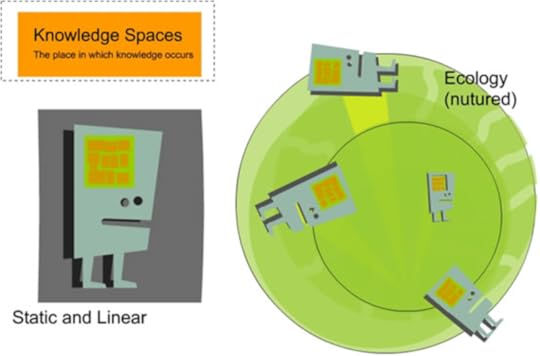

Knowledge Spaces

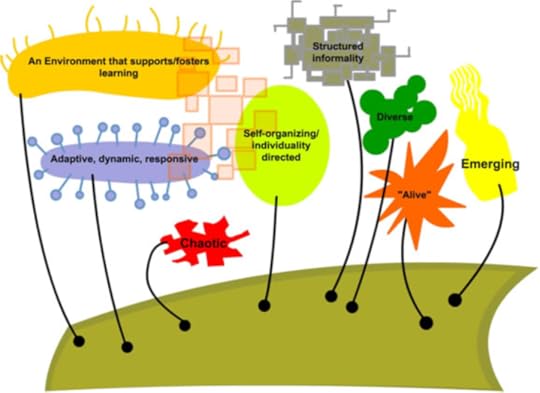

Knowledge and Learning Ecology

Knowledge Structures

[image error]

[image error]

April 5, 2025

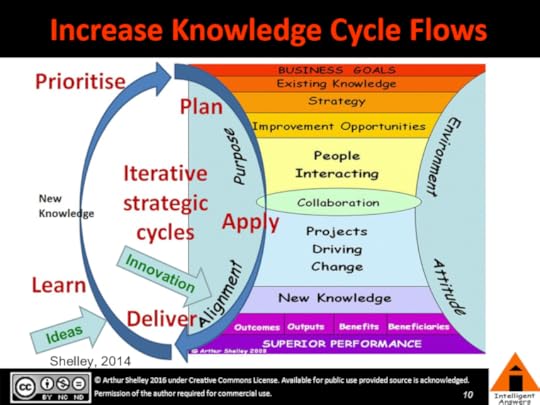

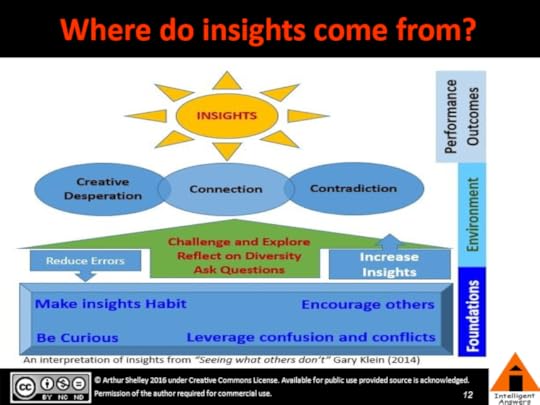

Knowledge Management Thought Leader 107: Arthur Shelley

Arthur Shelley is Founder and CEO of Intelligent Answers, an independent capability development and knowledge strategy consultancy. He is the former Global Knowledge Director for Cadbury Schweppes.

Arthur’s specialties are leadership, knowledge co-creation, behavioral development, team dynamics, stakeholder engagement, facilitation, and inclusive event production. He promotes building relationships based on co-creation and collaboration.

Here are definitions for five of Arthur’s specialties:

Co-creation: collaborative development of new value (concepts, solutions, products and services) together with experts and/or stakeholders (such as customers and suppliers). A form of collaborative innovation: ideas are shared and improved together, rather than kept to oneself. Collaboration : interacting with peers and colleagues to exchange ideas, share experiences, work together on projects, and solve problems. Culture : the way things are done in an organization, and what things are considered to be important and taboo.Facilitation: engaging participants in creating, discovering, and applying learning insights. In contrast to presentation, which is typically characterized by a sage on the stage delivering content to an audience, facilitation usually involves a guide on the side who asks questions, moderates discussions, introduces activities, and helps participants learn. Leadership : a process of social influence, which maximizes the efforts of others, towards the achievement of a goal.Arthur created the following content. I have curated it to represent his contributions to the field. For more about Arthur, see Profiles in Knowledge.

Books

Books Knowledge CoCreation

Knowledge CoCreation

Becoming Adaptable

Becoming Adaptable

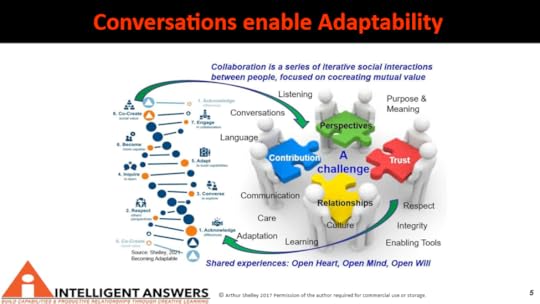

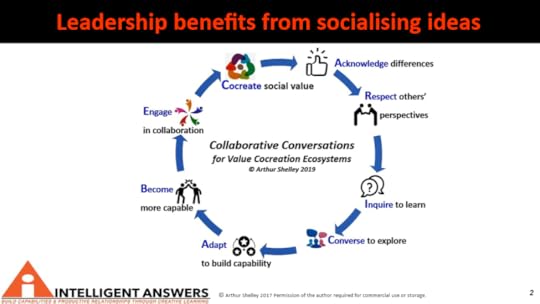

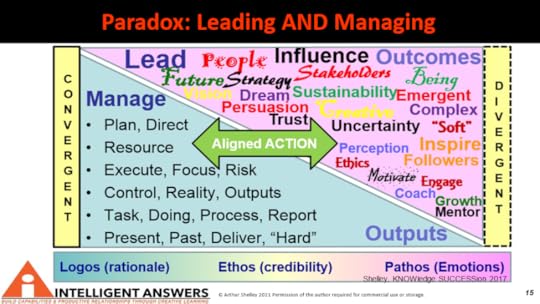

Behavioral DNA of Collaborative Leadership

Behavioral DNA of Collaborative Leadership

[image error]

[image error]

March 28, 2025

Knowledge Management Thought Leader 106: Hubert Saint-Onge

Hubert Saint-Onge is the founder and Principal of SaintOnge Alliance, with expertise in knowledge management, strategy, organization capability and learning, performance enhancement through culture renewal, and leadership development. He developed and refined a model called the Knowledge Assets Framework. This model strategically integrates business plans with branding, leadership, and people management to optimize the performance of an organization.

Hubert specializes in organizational performance, formulation and implementation of knowledge and learning strategies, development of communities of practice, strategic development of organizational capabilities, values alignment, development of leadership teams, leadership assessment and succession planning, assessment of customer-perceived value, and development and implementation of branding strategy. The focus of this work is on strategic planning, organizational change and transformation, collaboration, knowledge sharing, capability building, and leadership development.

Here are definitions for five of Hubert’s specialties:

Change Management : Developing a planned approach to change in an organization to address anticipated obstacles and to ensure successful adoption. Collaboration : Interacting with peers and colleagues to exchange ideas, share experiences, work together on projects, and solve problems. Communities : Groups of people who share an interest, a specialty, a role, a concern, a set of problems, or a passion for a specific topic. Community members deepen their understanding by interacting on an ongoing basis, asking and answering questions, sharing their knowledge, reusing good ideas, and solving problems for one another. Culture : The way things are done in an organization, and what things are considered to be important and taboo. Knowledge Sharing : An activity through which information or expertise is exchanged between people within or between organizations and communities.Hubert created the following content. I have curated it to represent his contributions to the field. For more about Hubert, see Profiles in Knowledge.

Books by Hubert Saint-Onge

Books by Hubert Saint-Onge Knowledge Assets Framework

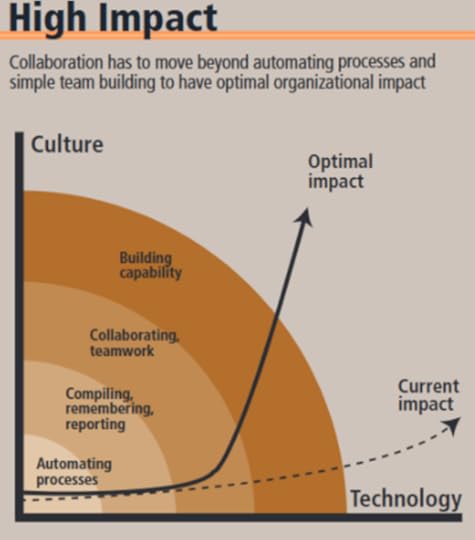

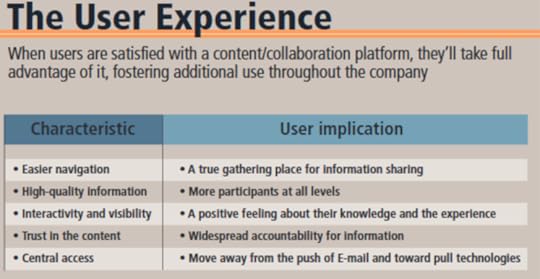

Knowledge Assets FrameworkThe Knowledge Assets Framework is a comprehensive model for leveraging knowledge for value creation, so that knowledge activities in an organization will have maximum impact. It comprises three pillars: knowledge architecture, technology infrastructure and culture.

An integral part of the Knowledge Assets Framework is the articulation of a Knowledge Strategy. This is best developed through a set of multi-dimensional questions to be addressed by the CKO through dialogue with other members of the organization. The questions cover the areas of intangible asset management, business case development, the role of learning and implementation issues.

Knowledge value creation must become a key theme in an organization before implementation begins. A scale determining the ‘knowledge readiness’ of an organization, or its ‘absorptive capability’ will help to determine what pre-cursors need to be in place prior to implementation.

The Power Of Shared Knowledge

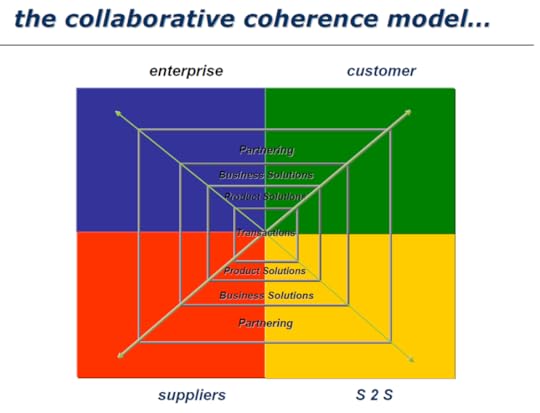

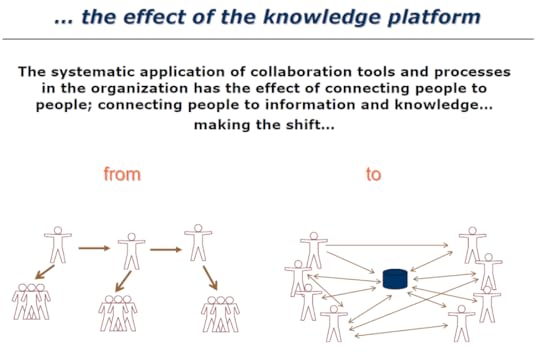

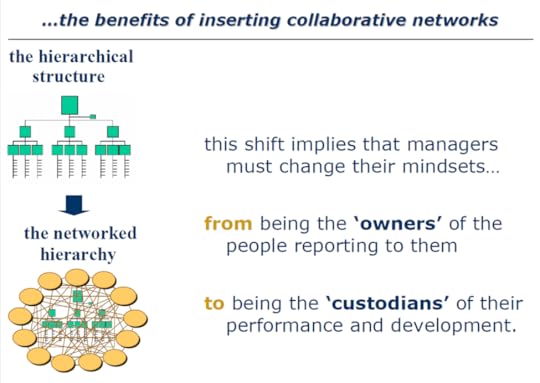

Collaborative Networks and the New Enterprise

Collaborative Networks and the New Enterprise

[image error]

[image error]

March 25, 2025

30th Year: 1,000 Blog Posts, 30 Lessons Learned

This is my 1,000th post since I started blogging in February 2006 on Line56.com (now defunct). In February 2007, I moved the blog to hp.com. When I left HP in 2008, I switched to Twitter.

In June 2014, I started publishing LinkedIn Articles for posts longer than my LinkedIn Posts. In July 2023, I started a LinkedIn Newsletter: Profiles in Knowledge.

My first Quora answer was to What are some recommendations for good social media and/or digital marketing conferences to attend? in January 2011. When Quora began offering blogs, I started one in November 2016.

Lucidea began publishing my content in October 2016 with KM Adoption Can be Increased Through Gamification Techniques. My first blog post for Lucidea was in May 2017.

I began using Medium to restore my Line56 and hp.com blog posts in March 2015. I now use it to make a copy of every post from every other platform.

If you would like to keep up with all of my writing, I invite you to subscribe to my LinkedIn, Medium, and Substack publications: