Fiona Murden's Blog, page 3

July 28, 2022

Protected: Working through personality with a mentee

This content is password protected. To view it please enter your password below:

Password:

July 11, 2022

What is it you truly desire?

My eldest daughter Libby has been watching the TV Series Lucifer over the past few weeks. On each episode the devil, working alongside a detective to solve a crime stares into the suspects eyes and (with a bit of comedy) asks them ‘What is it you truly desire?’ If I was there I’d make it a little less catchy by asking –What is getting in your way of going after what it is that you truly desire? Let me explain using a well-worn example….

Steve Jobs was born on February 4th, 1955 to a Syrian father and German-American mother. He showed an early interest in electronics and by the age 20 had started Apple in his parents’ garage with his friend Steve Wozniak. Over the next 10 years Apple grew into a $2 billion company. Then, just as he was at the height of his success – Jobs got fired from the very company that he started. Just like that – the focus of his entire adult life was gone.

Jobs described the experience as leaving him utterly devastated, humiliated and like ‘a very public failure’. He had hit that horrendous low point where it feels like there that there’s no point, no hope of things getting better. Most of us have been there at some stage in life. But when Jobs later recalls this event he says

“Something slowly began to dawn on me — I still loved what I did…I had been rejected, but I was still in love. And so, I decided to start over.”

In the space of 5 years Jobs started Pixar and a company called NeXT, which ended up being bought by Apple, bringing Jobs back to the very organisation he’d started. He returned with new ways of thinking and with the energy, insight and innovative outlook which enabled Apple’s renaissance.

In a speech Jobs gave about his life he said “I’m pretty sure none of this would have happened if I hadn’t been fired….I’m convinced that the only thing that kept me going was that I loved what I did. You’ve got to find what you love. If you haven’t found it yet…. keep looking until you find it.”

It’s often knowing what we desire or love and having a sense of purpose that makes pushing through failure and difficulties most possible, it enables us to weather the storm.

But the problem is we tend to forget or never even discover what it is we truly desire. And when we don’t know what we love, coping with failure is even harder. In fact, failure is one of the biggest barriers. We’re not set up to work with failure, we’re brought up in a way that often allows it to derail us and prevent us from living out our dreams.

Why does fear of failure get in the way of what we truly desire?

Fixed brain and fixed brain beliefs

Until recently it was believed that our brain was fixed in both form and function once we’d reached adulthood. But, over the past couple of decades our understanding has shifted – we now know that the brain’s “circuits” are constantly changing in response to our interaction with the world throughout life. As we think, perceive, form memories or learn new skills, the connections between brain cells change and strengthen. How incredible – just think of the possibilities for growth. The problem is the reality doesn’t align with what most of us were brought up to believe – that if our brain can’t grow and learn then it’s best to avoid any form of failure.

Knowing how to deal with negative emotions

Most of us have not been taught how to handle the bad feelings that come along with ‘failure’. Despite studying psychology for many years I’m only just learning how to experience my more difficult emotions in a way that’s helpful. Sure, sometimes I pushed myself harder when things went wrong and got through it, but other times I’ve avoided situations that may have brought up those ‘icky’ feelings. In other words, it was potluck how I responded, sometimes with the courage to take the leap, sometimes hiding, sometimes trying, sometimes not. It would have been so much more efficient for me to have known the right strategies early on in life, but this stuff isn’t taught in school.

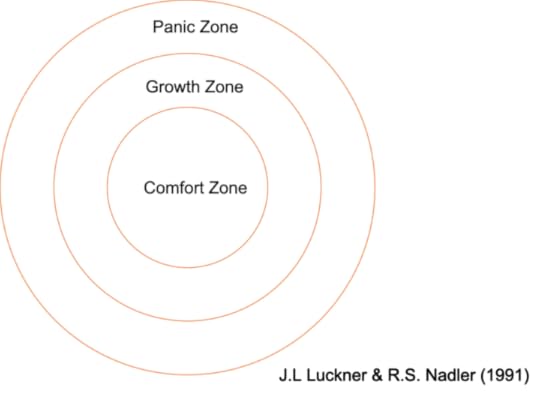

Staying in our comfort zone

Something which in part comes in part from the previous two points is a desire to stay in our comfort zone. If you risk failing and cannot grow from that failure and if you risk experiencing those pesky negative emotions it’s better to stay put. When you’re in your comfort zone you don’t have to take any risks, you know what to expect, and you have a sense of safety and security. It literally feels comfortable.

BUT to learn and grow as a person – to go after what you truly desire, you have to step beyond your comfort zone and into your stretch zone – pursuing situations that create a degree of discomfort.

So, what should you do knowing that you may face failure?

Learn more about why your brain is not fixedSee Carol Dweck’s book for more on this. Another great source of information is Norman Doidge’s work.

Learn how to deal with the discomfort of difficult emotions.A good way to start with this is to begin collecting a ‘living log’ of the evidence-based strategies that help you live with discomfort (Russ Harris’s work is helpful for this).

Sounds like hard work, right? Well think of the hard work that goes into those negative emotions if you’re not dealing with them e.g. the nights lying awake worrying, the angst and negative cycles of thinking. This is far more fun!

Monitor where you are at in spite of discomfort.Using the comfort zone model below keep an eye on where you are. Are you staying in your comfort zone when you could be moving into your stretch zone? At times this takes a bit of courage.

If we compare it to physical growth, an athlete cannot improve their performance by staying in the comfort zone, they need to train hard, to keep pushing themselves to their limits to enable growth and progress. They mustn’t spend too long in the panic zone, sometimes known as the injury zone because it will cause more harm than good, but neither do they want to stay in their comfort zone (for more on this see Ch 7 Defining You).

Comfort Zone Model

Comfort Zone ModelBut doing all of this without knowing what it is you truly desire is even harder. So if you can spend some reconnect with what you love. I’ll write more about this because it’s a big topic. But if you want to do a bit of personal reflection on the beach this summer, maybe defining what it is you truly desire, then it could be worth taking my book Defining You as your companion.

Meanwhile look out for upcoming podcasts episodes about continuing in spite of difficulty including one with Dermot Turing who talks about his Uncle Alan Turing. I find his story so inspiring.

Thank you to Regent’s University who recently invited me to talk on the topic of this blog post.

Suggested Reading:

Carol Dweck – Mindset: Changing The Way You think To Fulfil Your Potential

Russ Harris: The Happiness Trap: Stop Struggling, Start Living

Fiona Murden – Defining You: Build Your Unique Personal Profile and Unlock Your True Potential

There are also a couple of episodes with Russ Harris as a guest on the Dot to Dot podcast.

Image from Pixabay

June 6, 2022

Are negative emotions derailing your chances of success? Here’s how to deal with them…

I believe that everyone deserves access to the knowledge, tools and support that will help them to understand themselves better, so that they can fulfil their potential. Ultimately that means living a happier and more fulfilled life. One of the fundamental elements of this is being able to understand and respond more effectively to negative emotions – there is no doubt that they can trip us up on our way to success. We all have negative emotions, but that doesn’t have to mean we have stressful or distressing lives, or that they need to get in the way of our success. it’s what we do with them that matters. On this week’s podcast I speak to Dr Anna Colton about just this – distress tolerance – the ability to withstand pressure or remain calm in spite of stress. Let me explain using an example…

If you’re one of the many travellers who has experienced cancelled flights back to the UK this week you will have inevitably felt stressed and probably distressed as a result. How much distress however depends on several factors both external and internal. For example, if your child has an exam that it’s critical to get back for, you will probably experience more distress than say a retired person with no particular plans. The exam and delay are external factors which are out of your control. But imagine there are two parents of the same child with the exam next week. Both are experiencing the same situation, and both have the same concerns about getting home. Yet one parent seems hardly ruffled at all, whereas the other is shouting and screaming at everyone. The difference in response comes down to internal factors. So, what’s the point?

We all perceive situations differently and we also perceive our own emotions to those situations differently. So even if the external factors are exactly the same for all of the passengers.

some passengers will be calm and composed – they don’t perceive the situation as stressful. some will perceive the situation as stressful and therefore experience distress but tolerate the emotions that come along with that. They are also relatively calm, but for them it’s in spite of how they perceive the situation. some will overtly display a rainbow of negative emotions to anyone within earshot.What does knowing yourself better have to do with this and how does this relate to distress tolerance?Well for the sake of this article we’re interested in the middle group – the people who experience the situation as stressful, have the negative emotions but remain calm. They have a better level of distress tolerance and are far more likely to live a happier and healthier life. Sounds good right? So, what can you do to improve your distress tolerance?

There’s a lot to this and it’s something worth reading up more on (and of course listening to the podcast), but in summary:

We all (even the calm dude) have a quick emotional response to stressful situations in our heads. You can’t necessarily control that (although you can work on how you perceive situations, I’ll come back to that in another blog), but you can….Be aware of or ask someone you trust to make you aware of when you’re beginning to look like you’re becoming hooked by stress. One leader I work with asks his team to tell him when starts looking agitated, which has been a really effective way for him to raise his awareness and as a result his response…. Being aware brings your response into your conscious awareness, you then have a choice: You can act on the emotion, so if you’re angry that may mean going and shouting at someone, but that generally isn’t very helpful. You can fight that emotion, but a huge body of research shows that that actually makes it worse, it exacerbates the negative emotion. A bit like the response you may expect from shouting at someone but instead of being an argument, it’s a battle in your own head. You can ignore the emotion, but research shows that this also makes things worse, it will rear its head at some point and generally in a way that’s out of our control. Or you can acknowledge and accept the emotion. This is the most helpful response by far BUT it’s not easy. There is however a relatively easy first step which I’ll share in a moment.We often hear of the ability to accept an emotion as surfing a wave (I call it emotion surfing). If you’ve ever tried to stand up to a big wave as it crashes to the shore, you’ll know that it can knock you off your feet. You can’t fight the force of the ocean and you can’t fight the force of your response to threat, but you can learn to surf the wave.

The relatively easy first step is becoming aware of your emotions or asking someone else to help you notice. Then name the negative emotion (e.g. enraged, fuming, desperate). It sounds a bit too simple, but studies have shown that it has a surprisingly significant and helpful effect on your brain. Think of it like processing the emotion.

There are a whole range of other strategies and I’ll share some this week. It’s key to remain curious and examine your response lightly, analysis will lead to paralysis. Empower people you trust to help you. Try out the tools and see which work for you and remember to keep practicing. As P.J. Palmer says

“What a long time it can take to become the person one has always been.” But I would add, it’s well worth the effort the reward being more success yes, but ultimately the reward is living a happier and more fulfilled life.

For more tools go to my book Defining You (amazon links below – also available in national bookstores):

UK

https://bit.ly/DefiningYou2ndEd

USA

http://bit.ly/DefiningYouPaperbackUSA

Canada

Australia

Photo: Ric Rodrigues Pexels

March 2, 2022

Who believes in you?

I believe in you. I believe that you can do whatever it is you set out to. I believe that you are better than you realise.

We may feel like we don’t or shouldn’t need others to believe in us, but in reality, we do. It matters to feel like we matter, that we have worth and that others believe we can do the things we set out to. Even if momentarily it can unblock those concrete barriers we often put up in our own mind – sometimes just long to make a breakthrough or take action before they close back in again.

However, psychologically speaking we know that what’s most important to our self-esteem is our own self-belief. Not someone else’s belief in us but our belief in ourselves. Ultimately that determines what we can and cannot do. As Henry Ford said

“Whether you think you can, or you think you can’t you’re right.”

But there is no doubt one feeds the other. We all have wobbles, we all have doubts and we all, even those of us who may not show it, shine a little brighter with the right kind of encouragement and support. And to grow our self-belief often takes that belief from others, until it finally seeps into our own psyche.

How and where can you find more self-belief?

The good news is you don’t have to pay a coach or a psychologist, just take a look around – there are people who believe in you – I guarantee it. The hard part isn’t finding someone, the hard part is letting them help you.

I work with some amazing people, they are all very successful in their field and completely different from one another, but one thing they all have in common is that they let me help.

If you want someone to believe in you:

let them in, trust themlisten with an open mind and consider what they’re saying before you dismiss it let them believe in you even when you don’t believe in yourselfWhile you can do this without anyone’s help, in reality it’s very hard to build your self-belief on your own. You’ll get much further, far quicker if you find someone to support and encourage you.

Giving the gift of self-belief

A large part of what I do is to spot people’s capabilities, help them to see how to use them and show them that I truly believe in them. While I may be a sounding board to strategic plans, an advisor on team dynamics or a co-curator of communication I’m also nearly always a cheerleader too. And I get an enormous satisfaction from that part of my job. It is after all part of life to take on that role whether as a mentor, parent, leader, friend, actually a human of any kind – it’s something we evolved to do and to enjoy doing.

But despite being ‘natural’ it does take practice. The ultimate aim is the ability to instil such a solid sense of self belief in the person you’re encouraging that they don’t need you. If you’re really skilled they may not even know that you’ve got them to that point. However, on route to this supreme level of skill, be assured that even a slightly clumsy, poorly timed delivery can help positively impact someone’s life.

The three key elements to remember are:

Read the person – and take their lead. This is a far more effective way of approaching encouragement than telling someone what to do or think. It should be led by them, not you.

If I encourage in the wrong way, the people I work with quickly spot my efforts and switch off to what I’m saying. The same is true of anyone who is suspicious of our intentions. In at risk children that awareness comes less from a desire to avoid BS (as for the leader) and more from a need to protect themselves. However, the fundamentals remain the same…

If you don’t know what to say, listen – you’ll learn a lot about what you need to say and do by being open and exploring alongside someone. Advise when asked but don’t tell – encourage, talk, help them to understand what there is of themselves to believe in.

Timing. If you just throw out words of encouragement ‘willy nilly’ it won’t having an impact. Use your read of the person to judge when it’s right to encourage, when it’s right to give a little push and when it’s better to stay quiet and just….

Be there. Never giving up. This is the most powerful element of all. Think about it – if someone says to you ‘I believe in you and I’ll always be here’ and then when you need them, they are nowhere to be found, will you trust them to be there next time? Most probably not.

This is starkly demonstrated in populations of disadvantaged children who are mentored. When those mentors unexpectedly withdraw their support, the kids end up with higher levels of drug use, criminal activity, and depression than those who didn’t have a mentor to start with. Why? It removes trust, it removes hope and it shouts ‘you are not worth believing in’.

While a business relationship may not be as fragile, seemingly simple things like continually changing meeting times or cheering someone on one minute and not the next, can be hugely damaging. If you say you’re going to be there to support someone you better damn well be there. Once you decide to be someone’s cheerleader don’t walk away. Keep going until you have built them up to a place where they can believe in themselves.

Having someone believe in you can change your life course. But you have to let them.

Believing in someone is one of the greatest gifts you can ever give. It’s also one of the most rewarding things you will ever do.

To learn more about the work I’m doing with mentoring please email me at Fiona.murden@aroka.co.uk

For my books which provide more tools and know how for developing you and developing others go to:

https://bit.ly/DefiningYou2ndEd

Image from Pexels.com adapted using Canva

November 9, 2021

Knowing you, knowing me

‘How well do you really know yourself?’ A hugely significant 95% of us think that we’re self-aware, but the reality bears a stark contrast with 10% to 15% actually knowing who we really are (Eurich 2017). Although we believe that we know the image we see starting back at us from the mirror, the way we position our story on Facebook, Instagram or Snapchat, what our co-workers and friends think of us, in reality we spend very little time actually reflecting on who we are or asking people for honest opinions about the impact we’re having on them.

Self-awareness isn’t a new concept – another faddy notion claiming to be the route of all happiness. Plato said, ‘Know thyself’ more than two thousand years ago. Today, the understanding that knowing ourselves which is the cornerstone to realising our potential, is backed by the experience of generations and robust scientific evidence. In fact, as psychologists we even believe that this skill is the foundation of human survival and advancement (Eurich 2017).

Why Does Self-Awareness Matter?

The lack in self-insight that most of us unwittingly have, means we are wandering around with an equivalent of a blindfold on. We may be making it from one place to another but along the way we’re bumping into things, stumbling over obstacles and taking a really inefficient route to our destination. When it comes to behaviour that means unintentionally annoying people and making a myriad of unnecessary mistakes along the way. On the other hand taking that blind fold off would enable us to:

Work out what we actually want from life – without working out what we want there is no way of getting closer to it.Understand our strengths in order to start-making proper use of them.Work on our weaknesses and at the very least mitigate the negative impact they have.Having better self-insight also improves our social skills, decision making capabilities, ability to deal with pressure, resolve conflict and deal with stress.

Given all of this it’s unsurprising that knowing ourselves allows us to fulfil our potential. Indeed, eminent Psychologist Daniel Goleman explains that self-awareness is the cornerstone of emotional intelligence and success. In his book Emotional Intelligence, Goleman explains how in an organisational setting, once someone has an IQ of 120 or above, it’s emotional intelligence that becomes the most significant predictor of successful leaders.

And it’s not just soft skills that benefit, Dr. Richard Boyatzis a Professor of Organisational Behaviour looked at the profits produced by partners in a number of financial services companies measuring the 4 areas of emotional intelligence defined by Goleman. He found three of the facets had a massively significant effect on bottom line results with good self-awareness adding 78 per cent to incremental profit.

Most importantly of all having good self-awareness allows us to thrive. Knowing how to operate at our optimum but also being tuned into our mental and physical needs allows us to know when we need to refuel our body and our mind – leading to better physical and mental health.

How Can You Improve Your Self-Awareness?

Knowing how your brain works – it’s useful to first understand a bit more about how our brain works before delving into introspection. What’s normal and what’s not but also what’s helpful and what’s not. For example if you approach self-reflection in a way that’s hyper vigilant of everything that runs through your mind it will become counter-productive. When it comes to the brain analysis literally is paralysis. Instead try to be curious about yourself and your story but try not to ‘judge’, just observe.

Knowing about the world around you – a core component of self-awareness is understanding how our actions impact the world around us, not just looking inward. This is known as ‘external self-awareness’ and can be developed by:

Being curious – observing how your actions change and impact things. Also take note of how other people alter interpersonal dynamics. This is critical because external self-awareness is as important as internal self-awareness.

Knowing what you don’t know – approaching a situation accepting of your own inexperience. Not presuming you know the answer, rather asking questions with an open mind and really considering the answers.

Asking people what they think – ask for feedback from people who know you well and who you trust. Ask them to help you think through ‘What is really important to me? What am I really good at? What makes me unique?’

Knowing about you – it may seem a bit counterintuitive to put this one last but self-awareness is not pursely about self-absorption, it is about knowing about our passions and feelings but in terms of how they influence and are influenced by the context of the world we exist in. Ways in which to improve ‘internal self awareness’ include:

Writing lists or brainstorming – your strengths, weaknesses, what motivates you, what you stand for, what makes you happiest, what makes you mad.

Keeping a journal – not only does the process of writing itself allow the time and space for reflection, but also the capability to look back and learn from mistakes, at patterns of behaviour and their outcomes, to capture what makes you happy and what takes that away.

Making reflection a habit – this could be in the form of a journal or it could be meditation, mindfulness, going for a walk or a run, saying a prayer – whatever gives you the space to focus on what you’re feeling, how you are, what’s going on for you. Having the space to reflect on what makes us who we are, our own personal life story, is crucial to raising self-awareness.

Self awareness and learning about who we are is a continual journey – although the very core of us remains stable throughout life, our preferences, strengths, goals and passions modify and change as we grow and add to our story. If you make the effort to pay attention to that journey it can and will lead you to a far more fulfilled life.

Defining You: Build Your Unique Personal Profile and Unlock Your True Potential by Fiona Murden, is now out in paperback.

Available on Amazon UK, USA and Australia at the links below:

https://bit.ly/DefiningYou2ndEd

http://bit.ly/DefiningYouPaperbackUSA

To listen to my chat with Dr. Tasha Eurich, the guru on self-awareness go to:

References and links:

For more on how to approach self-reflection in a constructive rather than destructive way go to: https://warwick.ac.uk/services/counselling/informationpages/selfawareness/

Insight: Why We’re Not as Self-Aware as We Think, and How Seeing Ourselves Clearly Helps Us Succeed at Work and in Life by Tasha Eurich Published May 2nd 2017 by Crown Business

Immordino-Yang, M. H., Christodoulou, J. A., & Singh, V. (2012). Rest is not idleness: Implications of the brain’s default mode for human development and education. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 7(4), 352-364.

Tanner, J. L., & Arnett, J. J. (2011). Presenting “emerging adulthood”: What makes it developmentally distinctive. Debating emerging adulthood: Stage or process, 13-30.

Boyatzis, R. (1999). The financial impact of competencies in leadership and management of consulting firms. Department of Organizational Behavior Working Paper, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland

Beyond social capital: How social skills can enhance entrepreneurs’ success. Robert A Baron; Gideon D Markman The Academy of Management Executive;Feb 2000

Brackett, M. A., Rivers, S. E., Shiffman, S., Lerner, N., & Salovey, P. (2006). Relating emotional abilities to social functioning: a comparison of self-report and performance measures of emotional intelligence. Journal of personality and social psychology, 91(4), 780.

Ciarrochi, J., Deane, F. P., & Anderson, S. (2002). Emotional intelligence moderates the relationship between stress and mental health. Personality and individual differences, 32(2), 197-209.

Image: Shutter stock – George Marks

October 16, 2021

In Your shoes

On 2 September 2015 a story stirred something in thousands of people across Europe. For months the news had been inundated with stories of the Syrian refugee crisis, a mumble in the background as we all carried on with our busy lives. But on that morning the image of a small lifeless figure on a beach in Turkey, lying on his front, the palms of his hands and the soles of his tiny shoes facing towards the sky, drove through the shell of oblivion. The image appeared on 20 million screens in just 12 hours.

Another image shows an unsettled policeman carrying the toddler’s body up the beach, cradling it as if he were still alive.

Three-year-old Alan Kurdi drowned with his five-year old brother Ghalib and mother Rehenna while attempting to cross the Aegean Sea; only their father Abdullah survived. He describes the confusion as the flimsy boat was tossed around by the sea:

‘I was holding my wife’s hand. But my children slipped through my hands. It was dark and everyone was screaming. I tried to catch my wife and children but there was no hope. One by one, they died.’

The story of one boy brought the crisis into sharp focus. The human connection was made so much more visceral by seeing one boy and one grieving husband and father. We could understand the pain of one where the ‘many’ had become a blur of data and reports. The crisis of people fleeing civil war in Syria suddenly made sense. The image quickly went viral on social media with the hashtag #KiyiyaVuranInsanlik (‘humanity washed ashore’). Charities supporting refugees saw a dramatic upturn in donations. The amount given to the Swedish Red Cross, for example, was fifty-five times greater in the week following Kurdi’s death.

Perhaps before this the Syrian refugee crisis was too intangible to relate to. A dead child, however, was not. Perhaps most Europeans living in peaceful countries simply could not imagine the terrors faced by these refugees; or maybe up to this point they were the ‘out-group’, people different from ‘us’, which limited our empathic concern.

When asked if we are empathic, most of us will say ‘yes’. But wait a moment before you jump in with your answer. While are all born with the capacity to be empathic, this tragedy illustrates just one of the ways that we can unwittingly switch off our empathy.

Empathy and the Out Group

We have evolved to favour the in-group over the out-group. The driving force for this is simple: not being part of a group causes psychological distress. Individual sociability may vary, but we are innately social beings that yearn to be accepted by other people. Neuroscientific evidence indicates that people invariably favour other members of their in-group over people who are outside of the group. If someone exhibits unusual personality traits – such as a sardonic sense of humour or quirky dress sense – we subconsciously accept them if they are part of our group but tend to see the same tendencies as flaws if that person is not in our in-group.

Shutting Down Empathy to Prevent Pain

Another reason we can fail to be empathic is because we shut our empathy down. It hurts to feel others pain and so to protect ourselves we use mechanisms to prevent this pain, which can become unwittingly ingrained in who we are or at least how we behave. Take for example doctors, a profession where empathy is needed but is often lacking. This is not just my opinion, there is plenty of research to back this up.

While nurses and doctors can give us immense hope by simply telling us everything will work out OK and motivate us to get better if we take care of ourselves, equally they can quickly pull us down with one thoughtless comment or ill-fitting piece of advice. They can make us question ourselves: ‘Maybe I’m not in that much pain, perhaps there is nothing that is wrong with me?’, even when we have been in agony for days.

It’s not hard to see why empathic communication skills are critical to positive outcomes in patients being linked to increased diagnostic accuracy, a positive impact on the extent to which patients adhere to treatment plans, lower levels of emotional distress and more positive patient outcomes.

But although empathy, is positive, it can also go the wrong way and cause burnout and distress to those exhibiting it. After all, feeling what every patient is going through literally hurts at an emotional level. Anyone who watches Grey’s Anatomy will know that the character Izzie Stevens gets pulled along an emotional rollercoaster as a result of feeling the pain of her patients.

I’ve worked with doctors and surgeons who are both highly empathic and others who have shut down their feeling, which serves an unconscious protection. And studies across the world have shown that as medical students pass through their studies their levels of empathy typically decline. Have you shut down your empathy?

Emotional and Cognitive Empathy

What medical schools don’t teach is that it’s possible to have empathy while not burning out. Moving through the brain from emotional empathy where that pain is felt, to cognitive empathy where the pain is understood. A bit like

The second type is called ‘cognitive empathy’ and involves understanding the emotion and what another person is feeling, but not being engulfed by it. This is different from becoming immunised against emotion, which involves shutting that feeling down as a protective mechanism. Cognitive empathy in contrast illustrates a more developed capability than either emotional empathy or emotional immunity.

We can liken this to everyday emotions that we experience. Imagine that someone really annoyed you at work or even at home, and that you are so angry that you want to shout and scream at them. But you don’t: you stop yourself, assessing that feeling instead of giving in to it, and decide that shouting wouldn’t be helpful in the long run. The emotional regions of your brain elicits the initial feeling and your more rational areas of the brain then decides what to do with it. This is in effect what happens with emotional and cognitive empathy.

Empathy and Stress

Even for those of us who believe we are empathic; we can lose it. For example, Neuroscientist Tania Singer found that the part of our brain has an autocorrect mechanism, preventing us from looking only at our own feelings in a situation and ensuring that we are able to see things from others’ perspectives. However, when we have to make very quick, reactionary decisions, we lose this capability—in effect, overriding our empathy.

So when do we get empathy and can we become more empathic?

We continue to develop empathy throughout life. It begins when we stare into our mother’s eyes shortly after we are born and continues through childhood. But it doesn’t stop there. We build it through ever part of life while meaningfully connecting with others. The problem is that we’re losing it, not just because of the barriers I’ve already mentioned – in groups and out groups, shutting it down as a protective mechanism or losing it because we are stressed or working to quickly, but because of the impact of the way society operates more broadly.

“More and more, we live in bubbles. Most of us are surrounded by people who look like us, vote like us, earn like us, spend money like us, have educations like us and worship like us. The result is an empathy deficit, and it’s at the root of many of our biggest problems.” (New York Times).

There are many personal benefits to being empathic, from success in life, leadership and well-being to the organisational benefits, empathy enables diversity & inclusion, through to the societal benefits – creating a better, more sustainable and more humane future.

And sadly, there is evidence that our levels of empathy are on the decline. But there’s also evidence to suggest that we can continue to develop our empathy throughout life. There are some great tips in the NYT article referred to and of course in my books. But very simply speaking

Empathy and the Outgroupbe conscious of putting yourself in others’ shoes, listen, watch, be curious and try to understand. This will help you to overcome outgroup biases that you are probably completely unaware of, but that could have a hugely negative impact on someone else.

Empathy Shut DownIf you feel too little, allow yourself to experience what others are going through. Really make the effort to imagine yourself in their position. If this is hard speak to them to find out as much as you can, the more you know, the easier it will become to experience empathic concern.

Moving Emotional Empathy to Cognitive EmpathyIf you feel too much, work on how to take a step back, still feeling but making it a more rational process. This will help you to help others far more effectively and prevent burnout.

Empathy and StressRemember that when you’re stressed you’re less likely to see someone else’s point of view. Pause, reflect and take time to consider the impact before moving on.

Do these things every day and even remind yourself with every interaction. These may sound like simple things to do, but if you make a conscious effort to include them in your daily to do list, you’ll be amazed at how much it enriches your connections, your life and even your success. And you will be contributing to making our world a better place.

References

Some of the above was adapted from Mirror Thinking – How Role Models Make Us Human

If you’d like to listen to this as audio go to

https://dot-to-dot-behind-the-person.simplecast.com/episodes/in-your-shoes-a-conversation-with-fi

The New York Times Article referred to

https://www.nytimes.com/guides/year-of-living-better/how-to-be-more-empathetic

Photo – pexels.com

September 13, 2021

Why Rituals work

On this week’s episode of the Dot to Dot podcast Lou and I talk about why rituals work. It turns out that there are real, scientific benefits to rituals. Rituals are practiced in all walks of life from preparing for a job interview to playing sport – and of course in every religion. On the whole they ease our worries, concerns, grief, anxieties and give us comfort. When we take them too far they risk becoming OCD, when used in moderation they can actually benefit even people who claim not to believe that they work (Scientific American).

We’re used to the rituals of athletes such as tennis player Nadal, who places his hair behind his ear, pulls his nose and adjusts his shorts while bouncing the ball before every point. People have accused him of using this as a way to break the momentum of his opponents. But Nadal says that these routines are for his psychological benefits. And the research would suggest that this is true, for many of us, not just athletes. Rituals give us a sense of control when we’re facing uncertainty. Research by Harvard psychologists Francesca Gino and Michael I. Norton suggest that engaging in rituals mitigates grief caused by both life-changing losses (e.g. such as the death of a loved one) through to the more mundane ones (e.g. losing a lottery).

To listen in on our chat go to one of the following links:

Read more about Why Rituals Work

https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/why-rituals-work/

September 5, 2021

Not a lot going on at the moment…

I’m in front of a crowded room and desperate to get my point across, I have a burning, passionate view on this topic and my ideas are something I think people need to hear. I raise my hand and wait impatiently to be seen. Beyond jabbing at the air like a crazed loon or waving my arm about I can’t do anything else but wait until I’m noticed. Then finally, ‘yes, you’ says the person leading the discussion looking in my direction and the unimaginable happens – the worst – my mind goes completely blank. I go from feverishly preparing to share my wisdom to feeling like I want the ground to open up and swallow me.

“Our minds are magic. Like a prop in an illusionist’s sleight of hand, they seem to flit from place to place—now here, now there, now …nowhere.” (Ward & Wenger)

Has that ever happened to you? Chances are it has. In fact it’s so common that my friends Giles Paley-Phillips and Jim Daly have hosted a whole podcast (and book) on the topic aptly called ‘The Blank’. Interviewing people from the witty, quick minded Steven Fry to the equally fast thinking Dawn French and many, many more (even me) – it seems we really are definitely not alone. Yet it most certainly leaves you feeling that way.

“This mental state—mind-blanking—may represent an extreme decoupling of perception and attention, one in which attention fails to bring any stimuli into conscious awareness.” (Ward & Wenger)

While in front of family and friends drawing a blank may leave us feeling embarrassed, perhaps irritated, and frustrated in an environment of colleagues or strangers the emotions this can provoke are quite extreme. When the room swivels to hear our point and we are left with nothing we can feel shame, an unbearable embarrassment, fear at the loss of credibility and humiliation with of course the added undertone of emotions we’d feel if we were with friends. In short it’s not nice.

“Seven experiments provide evidence supporting the existence of the blank mind as a distinct mental state with a unique psychological signature.” (Ward & Wenger)

This happens to me frequently, too frequently. It’s even happened a few times when I’ve been midway through giving a talk – I stand there (or sit since the zoom era) searching for what I was just saying, what I just said, without any clue. And I fear that with the double whammy of age and the looming ‘unspoken about’ menopause things will only get worse. In fact with the effects of long Covid and the associated brain fog hitting so many people, the frequency may increase for many of us.

Let’s start with why – there are many reasons but the most common are:

Tiredness – slows down and interferes with all brain functioning Anxiety – fight or flight can mean that our brain prioritises taking action such as fleeing from these people suddenly staring at us over having a rational debate. Feeling overwhelmed – our brains are increadible but have a limited capacity for cognitive processing which can stop us from accessing those great points just when we need them.What to do:

Try to relax (easier said than done I know – it’s like telling someone to ‘just be more confident’) – use slow deep breaths, constructive self talk (i.e. calling yourself an idiot won’t help) and a rapid change of expectations (e.g. it’s ok if I don’t know right in this moment it will come to me). Make a list – of the points you want to make. While you may feel they’re front of mind when you’re waving your arm about, it’s worth doing anyway, just in case. Make a joke of it – laugh at yourself and if you can play it off with a self-assured demeanour and move on to something else. Get comfortable with telling people that your mind has gone blank. Use the silence – it’s ok to have a moment of quiet, in fact if you maintain your composure it could make you appear more confident and secure in yourself, not less. Use visualisation – if you know that you’re going to be in a talk or big meeting where this could happen, mentally rehearse the situation before-hand. See yourself as calm, confident, at ease and articulate. Play through the scenarios of someone calling on you when you are waiting to make your point, or you’re standing in front of an audience. This will give your brain the chance to practice, meaning it will more automatically take that route when you’re in the moment. Stay active – there’s plenty of research that shows exercise improves our thinking ability, concentration and attention by increasing blood flow and oxygen to the frontal lobe of the brain (I did a whole dissertation on this topic but I won’t bore you with the details).For more ideas about how to cope with those blank moments and plenty of fab conversation listen in to Giles and Jim’s podcast (link below) or for a more academic view take a look at the article by Ward and Wegner. I’d love to hear your thoughts and ideas too. For now though – Oh goodness I can’t remember what I was going to say…..

References

https://www.patreon.com/Blankpodcast

For a simple guide on how to use visualization take a look at the second edition of my book Defining You (make sure it’s the second edition – I don’t talk about this in the first).

https://bit.ly/DefiningYou2ndEd

Bunce D; Murden F (2006) Age, aerobic fitness, executive function, and episodic memory. European Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 18 (2), pp. 221-233.

Ward, A. F., & Wegner, D. M. (2013). Mind-blanking: When the mind goes away. Frontiers in psychology, 4, 650.

August 25, 2021

Models and mentors

My Dad died 8 years ago today. If I sit and think about the happy times and the sad, it doesn’t take long for tears to sting my eyes, but whereas once that happened several times an hour, with time that emotion has sunk deeper inside. Grief passes, loss never does.

Who were your role-models when you were growing up?

Dad shaped who I am and how I see the world. Through many years of profiling I’ve heard the impact that every parent has on a life, from childhood through to midlife and beyond. Every single one of us has been shaped by someone in our formative years be it positively or negatively. We, our brains and our identity are moulded by our experiences of the world and most of all that happens as a direct consequence of our interaction with our core caregivers. In the vast majority of instances, it’s our parents who has been the main role-models in our lives. Research tells the same story.

Who are your mentors?

As we grow up that learning doesn’t stop although of course the source does change. As adults we may feel embarrassed to say someone impacted us as a role-model or even a mentor, yet we are still learning from the people around us, all of the time. Some estimates go as far as saying that 90% of our learning is through social means. That presents a massive opportunity if used effectively.

Think about it, how did you learn to do your job or find your way around the services in the town you live in – was it from reading a text book, doing a course or through watching, interacting, listening and doing? Learning this way doesn’t always feel intuitive, despite being one of the most natural things in the world. Why? Because we’re brought up to believe that studying and qualifications matter most. When I first joined the firm of psychologists I worked with straight out of my Masters – YSC, I was raring to go. I wanted to get stuck in, to profile, to pull out insights that would help pin-point what made people tick. But I was told I couldn’t straight in, I had to sit in on profile after profile, making judgements, discussing them, being corrected and encouraged. The intangible of this felt infuriating. But, in reality it is how we learn most effectively, how we learn the nuances that can’t be taught from a book or course, especially those that involve our social and emotional worlds. We learn from and about other people through observing, listening and interacting with them. We are after all such social beings. This type of learning is the core way we know how to navigate our world – how to avoid failure and move toward success and how to have better relationships with those around us. When we observe others’ choices, whether the outcome is good or bad, we have extra information on what the best choice for us to make ourselves. Aside from anything else when it’s someone else’s experience it helps us mitigate our own failure and pain.

Your Models and Mentors

So, whether your aim is to learn how to be a brilliant leaders, be a good parent or train for a 10km race, you’re most likely to learn effectively if you have a mentor or an ‘unexpected’ role-model to guide you. Not a hero or heroine but someone you can see and talk to, or simply observe. They don’t have to be perfect, in fact you’ll learn more from them if they are not. Think about who your role-models and mentors are now, today- who can you learn from? Write them down, reflect on what you want to learn from them, the questions you want to ask, what you need to watch.

And also keep making use of the wisdoms you learnt growing up, reflect back on what they taught you and keep referring to their stories like a guiding light. And remember that just because you’ve grown up doesn’t mean there isn’t learning left to do. If you leave who is shaping you to chance, because people are nudging your behaviour and beliefs all of the time, you’re doing yourself a disservice.

I’m lucky I still have my Mum to check in with and guide me, which I do, daily under the guise of checking in on her, she offers me the comfort that only a Mum can. But although Dad is gone, conjuring up his positivity, wisdom and view of the world feels like a warm hug and still helps, if I let it, to shape the path I take through life. I miss you Dad.

References

Bandura, A. 1977. Social Learning Theory. New York, NY: General Learning Press.

Murden, F. 2020. Mirror Thinking – How Role Models Make Us Human. Bloomsbury Sigma.

August 15, 2021

I can’t get no sleep…

The importance of sleep has been getting increasing coverage over the past decade. We’re slowly moving into greater awareness of how important it is and that it’s not so macho to deprive ourselves. But how many of us still prioritise our social and career activities – whose demands seem so important and pressing – over ensuring that we keep ourselves and the people around us safe through having enough sleep? The problem is that we are surrounded by technology which can turn sleep deprivation into not only a health risk (e.g. A study of 10,000 people carried out over two decades by the University of Warwick and University College London found that people who reduced their sleep from seven to five hours a night nearly doubled their risk of death from cardiovascular disease) but also a fatal disaster.

In the US, The National Sleep Foundation carried out research which showed that 23% of Americans have fallen asleep while driving. Eighty-six per cent of the 1,027 people who participated in the research weren’t able to appreciate or properly identify the factors that made them drowsy. In the UK, statistics show that a quarter of all car crashes are caused by tiredness. Even if someone is not actually asleep, tiredness reduces reaction time, vigilance, alertness and concentration, which are all considered critical factors to driving safely. Judgement is also impaired, leading us to misinterpret distances, speed and the need to respond to stimuli. With this in mind, it is certainly worth considering ways to test for tired driving in a similar way as we do for drink driving.

The problem is, despite being dangerously tired, many of us still think we are functioning at a normal level. This misidentification of our own fundamental physiological drivers can lead to risk-taking that nobody would even consider if they were in full possession of their rational, well-rested faculties. Something that we’re lacking when tired and our survival driven brain takes control.

Lack of sleep is dangerous in many other environments too. Sleep deprivation costs the UK economy between £115 and £240 million per year in work- related accidents. Shift workers, doctors and nurses, lorry drivers and airline pilots are among those most often affected. This figure doesn’t even capture the knock-on impact: the patients who are not treated properly because their doctor hasn’t slept for two nights or the passengers at risk on a plane when the pilot is in charge of a long-haul flight having had barely any sleep.

Needless to say, life would have been utterly different for our ancient ancestors. When night came, most of their activities, in terms of hunting, foraging or doing any work around the settlement, would have been curtailed. Their options for socializing or entertainment would also have been extremely limited. Their living conditions were optimized for a long replenishing sleep. They did not have a thousand interesting distractions that would keep them buzzing and over-stimulated like we do. Unfortunately our brains have not evolved to keep pace with such seismic shifts in our lifestyles.

From an evolutionary perspective, sleeping even appears counterintuitive. Sleeping makes any animal, including humans in the modern world, more vulnerable to predators and threats. Hence sleep must confer some other powerful survival mechanisms for it to override the need for vigilance. Research suggests that sleep has a restorative effect, obviously, but how exactly it works has perplexed scientists for decades. Recent research, however, has potentially uncovered more about the potential function of sleep. Professor Maiken Nedergaard, a neurologist at the University of Rochester Medical Centre, has reported that sleep plays a critical function in ensuring metabolic homeostasis in all animals: preventing the build up of dangerous levels of biochemical waste produced through other chemical activities in the brain during our time awake. Nedergaard and her team showed that in live mice there was a 60% increase in the space between cells in the brain when they sleep. This space allowed a much larger amount of cerebrospinal fluid to pass between the cells and wash away the toxins which built up when the mice were awake. Nedergaard and her team believe the same occurs in humans cleansing our brains of harmful waste proteins. It wouldn’t be possible for us to be awake, attending to all the stimulating business of life, at the same time as closing down the brain to clean it. The bottom line is that if we were not able to clean out these toxins we would die.

Unfortunately, the advanced civilization we live in, with all its tempting distractions and technologies, clearly does not understand that there is a bottom line. Less sleep means less efficacy in removing toxins that can harm our mental and physical health.

Even when problems don’t get that far, our sleep-deprived lifestyles mean that we are less likely to fulfil our potential in more ordinary ways: keeping fit, pursuing satisfying personal relationships and fulfilling our work or creative achievement.

For more on how to optimise your own sleep take a look at:

Photo – pexels.com