Crescent Dragonwagon's Blog

January 7, 2013

getting good at it: the three secrets of writing (and pretty much everything else)

Bonnie Raitt? Yo-Yo Ma? John Coltrane? Lady Gaga? Eric Clapton? Youssou N'Dour? Dolly Parton, Mirian McPartland, Wynston Marsalis, Howlin' Wolf, Luciano Pavarotti, Biggie Smalls?

Doesn't matter. She, or he, does, or did, three things.

Practice. Rehearse. Perform.

Practicing

Practice is just playing around. "Just!" It's getting familiar, comfortable with your instument, whether it's your voice or the dobro. It's having fun, even if on a particular day it's not all that much fun. It's experimenting. And it doesn't have an intended specific outcome. It's just how a muscian says to his or her instrument --- or, if you like, to his or her muse --- "You matter to me. I want to hang out with you. And I want to do that just because. Just because I love you. Because I like you. Because you interest me deeply. Because every time I do, even and especially when I think I don't want to, you never, ever fail to show me something."

Rehearsing

Rehearsing? It's almost the same as practice, but with two gigantic differences. The first is, rehearsal has a specific intended outcome. Yeah, there's an element of fooling around, experimentation, and learning, always, but hey --- we're here to decide which songs are going to be in the second set or the next recording. And once we do, we're here to do them over and over again, in different ways. Until we decide on the way that sounds best to us. Thus the second difference: rehearsal is always, at a certain point, repetitive. When we decide on the direction we're going, on what sounds best, we're gonna do the songs that way over and over again, until it's as perfect as we can get it. All while knowing that perfect is an illusion.

Performing

And performance? That's where we show the world what we've done. Everyone won't like it, of course, but we know we've given it our best shot. And those who do like it will really, really like it. And the odds are good that the back-story of our efforts --- the practice, the rehearsals --- won't show a bit. It'll look effortless. (If the effort shows, the musician didn't practice and/or rehearse enough).

And --- here's the most amazing part --- all that work and effort and anxiety will fall away at the moment of performance. Because the performer, too, will be absent. Because he, or she, as an individual, as that person who worked, got bored, got anxious, got tired, didn't know if it would work out, questioned whether it was worth it --- that person is gone. There is just the music. Both the musician and the audience leave the concert hall or stadium transported, intoxicated. "That," we say, when we finally have words again, "was a great show."

Writing practice

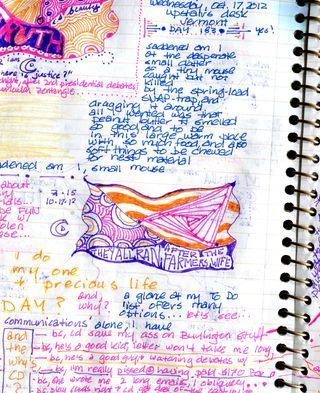

I practice writing every day. Yes, absolutely pointlessly. I can show you the cupboard of notebooks kept on and off since I was sixteen (I'm 60 now, and these days there is no "off"; practice is always on, every single day).

Sometimes I "freewrite." Sometimes I do an acrostic (never with just a single word per line, however). Sometimes I make lists (views I remember from various windows; interactions with birds; things I have lost; beliefs I used to have).

Sometimes I write haiku. Sometimes I do my practice at home; sometimes I take my notebook and little bag of pens to a cafe and work/play there. Sometimes I use a lot of jazzy colors, or doodle and sketch or Zentangle along with or in and out of the words. And I almost never read over what I've done. It's not for that. It's for the doing. It's the way I prostrate, daily, resting my head on the sacred feet of creation, taking refuge in something much bigger than I can understand but in which I trust, perhaps more completely than any other force in the world.

Sometimes I write haiku. Sometimes I do my practice at home; sometimes I take my notebook and little bag of pens to a cafe and work/play there. Sometimes I use a lot of jazzy colors, or doodle and sketch or Zentangle along with or in and out of the words. And I almost never read over what I've done. It's not for that. It's for the doing. It's the way I prostrate, daily, resting my head on the sacred feet of creation, taking refuge in something much bigger than I can understand but in which I trust, perhaps more completely than any other force in the world. Writing rehearsal

Most days I also "rehearse." I consider a first draft of anything I intend or hope to publish "rehearsal". Ditto, second draft. And third. And fourth. And more.

And then, there are all the drafts in response to others' responses to the prior rehearsals. I usually don't show what I'm working on until I've been over it quite a few times myself, and when I do show, especially at the beginning, I am very selective about whom I show it to. I want to know where whatever it is works and where it doesn't, but I'm aware that it, and I, may still be pretty tender. If I and the piece I am writing were a garden of enthusiastic seedlings, I don't want to be stomped on, I want to be thinned, weeded, maybe, and fertilized.

The writer's cast of producer/directors

Usually my partner is the first to hear or read what I've been rehearsing. In the old days, I used to often show these tender, just barely rehearsed starts to my mother, the writer/editor Charlotte Zolotow (at 97, she is far, far past this role).

Sometimes, it's the Second Saturday works-in-progress writing group I facilitate. ("Facilitate" as a verb sets my teeth on edge, but I don't have a better one. So far.).

Somewhere in here, my beloved agent takes a look. Though she is tough --- I have to be sure the work I show her, and my relationship to it, is sturdy enough to bounce back should it get a stomp or two from her. But she, my agent, is good. I don't always like what she says, but I usually wind up agreeing with it, and I never doubt that she wants what's best for the piece of writing.

Rehearsal for publication

If and when a particular piece of writing has been accepted for publication, a whole new round of rehearsal begins. This is the kind of writing called "revisions."

Some writers love this part. Some hate it. Me, at times, both.

Revisions-as-rehearsals are not as scary as those private first draft rehearsals, where one is usually making stuff up out of the most vaguely felt and pieced-together mash-up of ideas, hopes, experiences, and imagined stuff. Not as scary, but not as exhilarating.

The quality of revisions-as-rehearsals depends greatly on the editor.

A good editor pulls from you that which you have not quite said. She or he finds the soft punky spots, where the reader's foot would go right through the floor: where the writer has written inaccurately, or lazily, or without specificity, or untruthfully.

A good editor may make you wince, but his or her comments will also make you think. Spade over what you've done. Aerate your ideas. You read the editor's comments, he or she takes you out to lunch, and suddenly you get excited again. You say, "Yeah, unh-hunh, now I get it. I think. Sort of. Maybe! Let me get in there and see..." A good editor gets you wanting to go back to work. Your same-old piece, that you've been hanging out with so long, is suddenly fresh and eager, and calling to you, yelling to you, standing by the door stamping its feet, saying, "Let's go, let's go!"

A bad editor? A bad editor is a necessary evil: necessary only because every book gets assigned an editor, and she or he is the gatekeeper to publication. and if you want to get published, you have an editor, sometimes a bad editor.

Some bad editors are just plain dumb. They make you do extra work that does not make sense to you; that is unreasonable, that doesn't serve the book, that goes against what you are trying to say. And some bad editors are on an ego trip. It's power, it's I-know-better-than-you-the-writer (and oh how tempting, and foolish, it is to respond on the same level).

Whether benignly dumb or on an ego trip, here's what interactions with bad editors are not, and what they should be, and are with a good editor: how can these two diverse minds and sensibilities, those of the writer and those of the editor, work together, with discernment and respect, to co-create the best possible book/performance?

If you got saddled with a bad editor and you want to get published, you go along with as much as you can stomach. You try to do the absolute best you can with his or her less-dumb comments. You try not to sink to their level. You pick your battles; some things, you realize, you cannot "go along to get along" on. And if you don't do it too often, sometimes you, the writer, can just say, "No," to the editor (and oh how you wish they had been the kind of editor to whom a "Yes!" could have been uttered truthfully and with enthusiasm).

And you can also say the largest "No" and buy back your contract, and look for and hopefully find another publisher, with an editor who, though she or he may make you work your ass off, makes every rehearsal of the book, every rewrite, count. For a hard editor is not a bad editor. Unless she, or he, is.

I've had a few superb editors, a lot of so-so, somewhat competent ones (they improved the books in some ways, but in others did not, and wasted a lot of my time). And I've had a couple who sucked. And I've bought back contracts a couple of times. And/or, when it came time for the next book, "divorced" publishers who saddled me with bad editors.

Writing well, like playing music well, is a lot of work. Why do we --- writers, musicians --- do it, then?

Performance... and practice

Because sometimes a reader closes a book and sighs with pleasure. Says, in effect, "That was a really great show."

But you know what? I can't, in my heart of hearts, say I write to cause this reaction. I love having this reaction as a reader... but if I set out consciously to try to create it as a writer, if I wrote because I wanted to astonish readers, I would freak myself right out of writing a word.

That words which I've written do, sometimes, give something big to my readers: that's extra. That's gravy. I'm delighted. I'm humbled. I'm pleased. And in my heart's core, each and every time I get this reaction, even as I may be saying politely and truthfully, "Thank you so much," I swear to you that inside myself I am prostrating, resting my forehead on the sweet, beloved feet of creation itself, mysterious, strange and compelling.

Unlike a musician's transcendent "great show" moment, we writers have our instances where we are emptied out (in the best possible way), transported, intoxicated in the act of writing itself, not performing as such. Not every day, not every time. But sometimes while practicing and sometimes while rehearsing, it comes.

And so I return to practice. I say to my writing, "You matter to me. I want to hang out with you. Because I love you. Because I like you. Because you

interest me deeply. Because every time I do spend time with you, even and especially when I

think I don't want to, you never, ever fail to show me something."

Because nothing is wasted on the writer.

December 18, 2012

speaking the unspeakable; accepting the unacceptable

Once a month most months,I make the roundtrip drive from Westminster West,Vermont to Hastings-on-Hudson, New York (where I spend a week with my 97-year-old mother, Charlotte Zolotow). Leave Vermont, cross Massachusetts, cross Connecticut, reach New York. And then reverse it. Exit after exit, I read the names of the towns and have my semi-mindless associations with them. Chappaqua, New York; Hillary and Bill Clinton, who have a home there; Pleasantville, New York, my late Aunt Dot's late long-time companion, Jim, who had a home there; Elmsford, New York; that Persian restaurant I like.

Last Thursday, December 13, 2012, I was coming up 84 to Hartford, had almost reached the point in the tangle of lanes where I knew I needed to get to the right to pick up 91 North. Had passed the Connecticut exits with their associations: Waterbury, where I once got fuel, drove off without removing my wallet from where it was resting on the car, and, miraculously, someone turned it in to the local police and I was able to pick it up intact from them. Newtown; I once stopped at an "easy-on easy-off" diner there late at night and had some really not-good lemon meringue pie. Meriden; that's where Ken, who I dated briefly, used to live.

Usually I drive our late model Subaru Forester, but occasionally I drive the crap car: a 2001 Dodge Neon, so low-end that it actually has roll-up (with a crank) windows. I was driving the crap car on Thursday.

It was almost rush-hour as I approached Hartford, a time/place continuum I try hard to avoid on this commute. There was more traffic than I prefer, but I'd still be on the other side of Hartford before it hit full spate. I changed lanes to position myself for the split to 91 North, braking slightly.

And

suddenly

I had

no

brakes

at all.

I considered for maybe 3 seconds trying to pull

off on the nearest ramp and get to a service station. Then in far less

time than it takes to write this account, I ran through the impossible odds of being able to end up at a service station without hitting anyone or anything, off an unknown exit, near rush hour, in downtown Hartford. I realized, "NO."

I was in the right lane. I pulled off onto the shoulder --- narrow, but wide enough --- and glided to a stop. Safely.

I put on the flashers. I called

David. I called AAA. I got right through to Roadside Assistance; they took my position seriously. "We're

putting you on the top of the list."I called another friend. I sat in my car and waited for the tow-truck. I was not yet shaking at my close call, though the car shook with each 18-wheeler that passed. I was relatively still, against the loud white noise of the non-stop traffic stream. I simply couldn't believe I was fine. Alive, unhurt, had not hurt anyone else, had not even dented the crap car. And I was overwhelmed by gratitude and amazement.

The rest of the story --- how I got home, the nice guys at Cameron's Auto Service, David picking up the repaired crap car --- does not really matter.

What matters is, there I was, swimming --- that day and the next --- in astonished gratitude that my life had been spared in Hartford, Connecticut, when I heard the news of the massacre in Newtown. Many other lives, twenty of them the lives of six- and seven-year-olds, had not been spared.

I can make no sense of any of this, on any level. While Rilke advises us to "be patient towards all that is unanswered in your heart, and learn to love the questions themselves," there are some questions, the most profound and fundamental "why" questions, which are simply not lovable and towards which we cannot and perhaps should not and must not be patient.

On one level, the "why" in the case of this slaughter must be addressed. Guns, and the culture of violence so prevalent and glorified in America. Guns and their licensing, or lack of same: I just don't GET why you have to take a test

(not only written but in an actual vehicle, with a policeman no less),

to get a drivers license; then document, tag and title, at each and every point of sale for a car, which is a transportation machine (though it can certainly kill you) but not for a gun, which is a killing machine (though it cannot transport you anywhere, except, possibly, to the next world). Mental health care, and access to it. Causal factors in mental health, including funding cuts not only to clinics and veteran's hospitals, but to programs like Head Start; nutrition and the prevalence of fast food and its effects on mental and emotional state, violence and abuse in the home, and education.

Lord knows these "whys" are complex enough, and faceted, and interrelated. That's the great lesson of ecology: everything affects everything else. As conservationist John Muir famously said, "Pull any thread in nature and the whole unravels." Humans are part of nature. Pull the thread of a human action, sacred or profane, horrific or heroic, and our understanding begins to unravel, deepen, and grow forever more unanswerably perplexing... and "there but for fortune go I."

But even if we could address these sorts of "whys" in the case of this massacre, even if we could alter the legislative and behavioral factors that led to Newtown --- which will now forever bear the crosses of the murdered innocents, which will now forever twist the hearts of even those who casually pass the green and white sign announcing its exit off 84 --- the bigger why remains.

Why are some saved and some lost?

And this is the one that can never, ever even provisionally be answered. (Unless you are Mike Huckabee, who has explained that what happened in Sandy Hook is due to prayer having been 'removed' from our schools.) Wipe out school violence tomorrow, and you are still left with the families who lost their children, who must live forever in an 'after' they had no idea was coming when they got up that morning, made French toast, bundled small arms into sweaters, lifted small back-packs onto small, dear shoulders. The waves of grief spread out and out forever. The circles of grief never stop widening.

I just don't get how our wonderful, gorgeous, one and only world can be so chockablock with hate, evil, ignorance, violence. But, how can anyone get it? It is ungettable.

That being so, what do we do with such events?

I think the trick --- one I so have not come anything

close to mastering --- is to stay permeable to the world in all its

agony and beauty.

Permeable, responsive on a practical level whenever

and however we can... and yet "immunized emotionally" to the extent that

we don't wholly lose our equipoise no matter what.

And when we lose it, as we will, as we must, as we should, in response to things like the deaths at Sandy Hook... Well, I used to have a yoga teacher who would say, on the tricky balance poses as half the class was falling over, "Let your coming and out of the pose be part of the pose."

I think it has to be like that. When we inevitably, and often properly, lose our equipoise, we let that --- that sorrow, that lack of balance --- "be part of the pose." And

return to the reaching for balance. Not achieving it; just reaching for it.

Not blocking out the

world; yet neither so losing ourselves in its infinite painful and

horrific 24/7 news cycle, the endless stories, both new and repeated, that we are flattened and incapacitated.

Not easy. But the alternatives (being flattened by pain or hardening one's heart to it, becoming impermeable) are worse.

My own brush with mortality the day before filled me with gratitude; the news of the innocents' deaths, so nearby, the following day, with heaviness, despair. Yet in one sense both tell the same story: that our lives are on loan to us, and may be recalled at any time. That the veil between life and death may be opaque, but is paper-thin. That, in the end, we must make our lives worthy of the privilege of having been given this precious loan. That we must stay permeable and balanced, the better to do whatever work has our name on it. That this work should be generous --- as generous as the giver of that mysterious gift of our individual loaned lives as been to us.

And the 'what does one do with such events' question takes on another dimension if we are writers. We must write about this, however imperfectly and inadequately. We must try to speak the unspeakble.

It is the tiniest of ways we can not let those small bright lives have been wasted.

This poem comes from her View With a Grain of Sand, translated

Stanislaw Baranczak and Clare Cavanagh (New York: Harcourt, Brace,

1996)

It could have happened.

It had to happen.

It happened earlier. Later.

Nearer. Farther off.

It happened, but not to you.

You were saved because you were the first.

You were saved because you were the last.

Alone. With others.

On the right. The left.

Because it was raining. Because of the shade.

Because the day was sunny.

You were in luck -- there was a forest.

You were in luck -- there were no trees.

You were in luck -- a rake, a hook, a beam, a brake,

A jamb, a turn, a quarter-inch, an instant . . .

So you're here? Still dizzy from

another dodge, close shave, reprieve?

One hole in the net and you slipped through?

I couldn't be more shocked or

speechless.

Listen,

how your heart pounds inside me.

July 30, 2012

Have I missed anything?

I had no idea Nate was an undercover cop in the Narcotics Division of the Chicago police department the first time I slept with him. I will skip the whole long, weird tale of his and my relationship, which only lasted 5 or 6 months, and took place when I was around 23 years old, other than to mention that my not knowing this essential fact was due both to the general social-and-mating practices of the period (early 1970's) and the circumstances under which we met (picked each other up at a now long-defunct bar called The Quiet Night, in Eureka Springs, Arkansas, where I then resided and to which he had come on vacation).

Fast-forward to maybe 3 or 4 months into our relationship, which was a major crush, and of course, very exotic to both of us. No email then, but we managed daily or near-daily phone-calls, notes by mail, and his not infrequent visits to Eureka Springs. I think I'd visited him in Chicago maybe twice before I got the call. I remember my hand flew to my mouth and I literally dropped the phone, and had to pick it back up again from the floor onto which it had clattered, for after I had replied in the affirmative to "Is this Crescent Dragonwagon? " what I heard was "I'm a friend of Nate's. Now, it wasn't fatal, but Nate was stabbed in the middle of the night last night."

I got myself up to Chicago as soon as I could to be with Nate, who was already somewhat up and around by the time I arrived 2 days later. Fortunately, if you can even use 'fortunately' and 'stabbed' in the same sentence, he was stabbed in the spleen. Evidently, if you're going to be stabbed in the viscera, the spleen is a good place for it. Evidently, they got him to the hospital quickly. An inch up, down, sideways, or deeper, it would have been a different story. But this one was mostly, "Don't make me laugh, it hurts," and my going on short walks with him, cooking for him, rubbing his feet, and resuming sexual activity as soon as was possible, which was surprisingly soon.

But though this post has to do with mortality, it is not about Nate's being stabbed. All this is to explain

my being present at the party Nate's buddies on the force threw for him to celebrate his survival, and welcome him back to active duty, a mere two or three weeks after the stabbing.

Now, picture this, though I know it stretches credulity (even mine, and I lived it, however cluelessly). Imagine a 23-year-old New York-Arkansan woman whose lifestyle has been, to put it mildly, alternative and boho from the get-go... a life that has included dropping out of high school, back-to-the-land era communal living, the taking pf psychedelics a few times, along with the straighter things: publication of a few of her books, semi-famous parents. Picture that young woman (I'm tempted, now, to say, 'girl', but such a designation would have outraged me at the time), in a large meeting room in Chicago, at police headquarters. Also present are maybe 20 or 30 Chicago cops, most in the Narcotics Division.

To say that Nate's pals were curious about me is an understatement on the level of "A stegosaurus is larger than a dog," not that I fully understood this at the time. I do not remember any other females present, though there must have been some. I do not remember if there was any food served (this is unusual; I always remember food), but there must have been some. I seem to remember beer. And I do know there was some punch, pink and almost surely non-alcoholic.

I remember the punch because I was standing next to it, ladling some up for myself. I believe it was almost surely non-alcoholic, because, despite the early dabble in psychedelics, I don't drink and never have (other than a few sips of wine from a friend's glass, very occasionally). And it was there, at the punchbowl, that the following conversation took place, between me and a burly, dark-haired guy, one of Nate's colleagues. He had a build one might perceive as threatening in some situations one could imagine a Chicago cop being in. But then and there, towards me, he emitted a sweet vibe.

Burly (friendly, dese-dem-dose accented): So. You're Matt's girlfriend.

Me (demurely): Yes. Yes, I am.

Burly: The one from Arkansas.

Me (agreeably): Yes.

Burly: The one who's a writer.

Me (cheerfully but with a slight manic edge; where is this going?): Yes, that's me!

Burly (musing, a little dreamily): Jeez, a writer. You know, I always thought, a writer, that's gotta be a great thing to be. You see your name on the paper, right there... (he pauses, thoughtfully) ... Jeez, you know, you achieve immorality when you're a writer.

Me (instantly recognizing that I would remember this moment forever and that I must not, in any way, indicate this hilarious slip to this sweet guy, let alone what its nature was, because not only would that be incredibly boorish on my part, it would've embarrassed him down to his follicles... so, replying in a modest tone, lowering my eyes, I said): Well, I do my best.

And I do. Though rarely does it seem all that good to me. Hardly immortal. But not immoral, either.

***

Like anyone about to turn 60, my thoughts turn towards mortality. Even more so because I am not only a writer, but both a literary executor (of my late father, Maurice Zolotow, a show business biographer) and a literary-executor-to-be ( of my 97-as-of-this-writing mother, Charlotte Zolotow, a children's book writer).

And I am an Authors Guild member. Twice a year I read the Guild's Bulletin. Rarely do I get to the boxed-in listing titled "In Memoriam", and the one-paragraph-long obits of the better known writers on that list, which follow later, listed under "Deaths", without feeling that deep, unsettling, resonant twinge, occasionally with a sharp, sudden dart of grief. Sometimes I see the name of someone I actually knew, or knew of, or whose work I loved. The work lives; the person who wrote it does not. Of course I think about mortality. Far more than immortality. (Immorality is another question, one we will not take up here, so don't get your hopes up.)

***

My mother, as I mentioned, is 97. About two months ago, we celebrated her birthday. "We" was me, my partner, David, most of our team of Jamaican and African caregivers and some of their partners and/or adult children, maybe 10 or 15 neighbors from the block on which Charlotte lives, in Hastings-on-Hudson, New York, and a couple of her old friends from the publishing world. The party was held on her front porch, and there was quite a spread of food (of which, she said modestly, the jerk tofu I made was the hands-down favorite). It was a relaxed, come-and-go affair.

Charlotte was in her recliner, which had had to be moved from inside the house, and to which she had had to take a longer than usual wheelchair ride, so she sort of half-listened half-dozed throughout the early part of the party; eyes closed but smiling. I had the sense that she was rocking along in the sounds of conversation, people enjoying themselves, lids being flipped off bottles with church-key openers, laughing, greetings.

People sometimes say to me, "Is she still with-it?" Or "Does she have dementia?" Or they mention Alzheimers, or short-term memory loss... While Alzheimer's is out-and-out inaccurate in her case, I don't really like any of these other summations of her state, for they seem to pathologize (label as illness, or abnormality) the altered working of the mind in the very old, which is as unique, from what I can tell, as the working of a young child's mind... but normal within its paradigm. (Of course, I'm not talking about real illness, where there is a sudden and disordered change of mental state which causes distress, like Alzheimer's).

Charlotte sometimes is clear and coherent, sometimes off the wall. Sometimes she makes jokes. Sometimes she struggles for a word or words, or doesn't complete a phrase. (Like "L...l...l" for "love", let's say). Sometimes she truly is in altered state, perhaps finishing up unfinished matters from her early life (one evening she stayed up all night long, laughing and talking with her sister Dorothy, who died many years ago, and her young daughter Ellen, who was me before I became Crescent at 16 and thus in a sense also died many years ago; every so often she stays up worrying about "the office" and if "everything is organized." The office was HarperCollins, where she worked for many years, and always did worry about).

Late in the afternoon of her birthday, Charlotte opened her eyes suddenly and looked at me. "What, " she asked slowly but clearly, "did I... miss?"

I thought a moment before I answered. Because maybe she meant that afternoon, while she was half-dozing, but maybe she meant something else, something bigger... so I tried to vibe it out. And I always, in such moments, try to orient her a little bit.

"Well, Charlotte, you're at 29 Elm , in Hastings, and we're having your birthday party today. You're 97 years old and ... I don't think you missed much. Let's see... You were married, you had two children, you wrote an incredible number of books, you helped a lot of people write their books when you were an editor. You traveled all over America and through a lot of Europe. You had a lot of friends, you had a lover, you had a garden, you read hundreds and hundreds of books. You ate Indian food and Chinese food and French and Italian and Mexican food and now you're often having African and Jamaican food--- really, I don't think there was anything big that you missed!"

Charlotte, who began laughing during this recitation, said, when I finished, wholeheartedly, "GOOD!"

But, does Charlotte remember writing 100+ children's books? No.

Her readers certainly do. And I (so strangely) am the gatekeeper of the bridge between them and her. The bridge itself is, of course, her work itself, which lasts, even as she does not and cannot, any more than the rest of us.

As this gatekeeper, her literary-executor-to-be, I am sort of Charlotte's executive secretary and the guardian of what I think she would have wanted me to say and do when she was in her middle-aged (as opposed to "right", another pejorative, dismissive word) mind. I answer emails that come in to her, and there are a lot. While some are seeking permission to reprint a poem of hers in an anthology, for instance, many more are just plain fan letters. Except, not just plain. Charlotte's readers, young and older, write about what her books mean to them. Often they reference having read them when they were children, and now reading them aloud to their own children, or even grandchildren.

Here is one email I received, and answered, yesterday.

"Hello! My name is Felicia ... I am 20 years old. I'm writing to you today because I was recently going through some of my old books and I stumbled upon one of my favorite childhood books, I Like To Be Little.

"I researched the author and came across your website and email address. From what I understand, Mrs. Charlotte Zolotow is 97 years old! Wow! I'm happy to see that she has lived such a long and happy life.

"Mrs. Zolotow's book was a staple in my childhood. I remember buying the book from a little shop in our local library where they sold used library books. My family couldn't afford things like video games to buy me so instead they bought books. Whether they were second-hand or brand new, I cherished them all.

"I Like To Be Little taught me how to embrace my youth and not to be in a rush to grow up. This has become such an important lesson to me and now I am able to pass this book on to my 6-year-old niece. This story will always be relevant and I just wanted to thank Mrs. Zolotow for teaching me such a simple yet important life lesson. I hope to also pass this on to my future children so Mrs. Zolotow's work can live on.

"I hope this email reaches you. Thank you, Felicia "

My response to her:

"Thank you, Felicia... I am Crescent, Charlotte's daughter. My mother is indeed 97 years old now (and does not really remember writing her books). But she would have loved your letter. And I love it now! Thank you so much... I am very moved and grateful.

Crescent Dragonwagon"

This response was truthful, yet less than complete. To state the whole truth, I'd have had to describe the poignancy of being in this role and relationship, to someone who created works like my mother did... and who is where and what she is now. And, though I am trying to do that here, I can't describe it, or explain, adequately.

Sometimes --- always, actually --- life just is too big for me. We are such tiny intricate pieces of an infinitely more intricate whole. We do the best we can, but really, with very little understanding of the part we pay in the larger spiritual ecology.

Here in Vermont, in summer --- yet, because we are past the solstice and the days are already shortening, moving towards fall and winter --- the huge bullfrogs in our pond give their nightly throaty resonant calls, which always make me laugh. They sound from different sides of the pond, and, if I sit on the dock and listen, I can hear the distinct and unique tones of each different frog who is part of the choir. The depth of the one on the right, toward the sugar house, versus the one on the upper left in the cattails, a little higher in pitch, and the one in the near left, just past the dock, who is a bit softer. Slightly, subtly one of a kind. But all, to me, just delightfully humorous. (David, my partner, can imitate them flawlessly. And does, sometimes out of the blue, when he feels like making me laugh).

The frogs, like me, like Charlotte, are playing their parts, and presumably don't obsess about not having understanding about what those parts are, about "meaning", as much as I and most human beings do, and as Charlotte did.

And I hope I do as well at my work as the frogs do. And as my mother, who also didn't understand, did. She did so without understanding any more than I do (as I know from many conversations with her in the past and even, sort of, in the present, and from her work itself).

Ah, Mr. Burly Guy, back in Chicago more than 40 years ago, a writer doesn't and can't achieve immortality (though immorality, sure; much easier). If we are fortunate, and diligent enough at our practice of writing to get good at it; if we are able to empty out through and after practice enough for something greater than our small petty confused selves to flow through us, using us a conduit; if, if, and if, than just maybe our work may outlive us. And it may even connect us with others , across space and time and circumstance, in mysterious ways. Most of which, like my mother and Felicia, we will have absolutely no idea about.

Nor would it neccesarily be such a great thing for us if we did. The bullfrogs couldn't make their calls one bit better if they knew there were delighting me. If a writer meditates on immortality, or pleasing his or her readers, or writing something astonishing and earth-shaking, he or she is not working and the earth will not give the slightest shrug of astonishment. As William Faulkner said, "Not 'Be a writer.' Be writing." Well, yes, exactly.

And, as my mother unknowingly reminds me daily, even the chance to "be writing" is time-limited. Even if her mind worked in the fashion it once did --- linear yet poetic, able to put thoughts and feelings into words, and find those words, and craft them into sentences that speak to readers --- her arthritis-crunched fingers could not begin to hold a pen or tap a keyboard.

A woman in her late 20's with the same last name as Nate, my old cop boyfriend, contacted me on Facebook, saying she knew I'd once been friends with her dad. She'd found a copy of one of my books in the attic, inscribed by me to him. She made a friend request; I accepted. She and I have never had much Facebook interaction, but, through her page, I now know the slightest bit about how Nate's story came out. That he married. That he had children. What he looks like now (I cannot recognize, in the picture of her and her dad, the bright-eyed slim young man, the brave cop who survived a stab wound, and lived a fascinating almost actorly life when he was his 'underground' self on the job, with whom I was so briefly deeply and intoxicatingly infatutated, when I was myself younger than she is now).

Are my words or memories made "immortal" just because they are written down? I don't think so, but I don't think it matters, nor is that what I am trying for in my work. What matters is very mortal indeed, to me: life fascinates, seduces, crushes, and mystifies. I keep trying to figure it out, and realizing that I never will have any more than the most provisional understanding.

But one thing I also have come to realize is that, as I said in the subtitle of this blog, the human desire to tell and hear, read and write stories, is part of the process of life figuring itself out. What subtractions! What gifts! All that happens --- love and loss, a stabbing to the spleen, the lovely funny self-important croaking of the bullfrogs, a pink punch, a misspoken word, a laugh, a platter of jerk tofu, a book finding its way into the life of a little girl whose parents couldn't afford video games, an old old lady on a front porch, wondering, one June day, if she has missed anything --- it happens, all of it, in any event.

But if we write about it, for us at least, it goes unwasted. We won't be here long, any of us. But we were here. By writing, we bear witness. And, we bear life.

But in the act of writing, if we are fortunate enough to hit the flow state (as inevitably happens at least sometimes, if one shows up on a daily basis) we don't think about any of that. We are, briefly, exempt from time altogether. We have a moment when, regardless of the quality of the writing produced, and whether anyone likes it or not, we are exempt from time. It has nothing to do, Burly, with seeing your name on a page. But it's as close as one can get to immortality... for a moment or two.

April 14, 2012

just so you know I haven't been totally slacking in the blog department...

Look, I realize that in Blog World having your last post dated December 12 when it's now the following mid-April looks bad. Really bad.

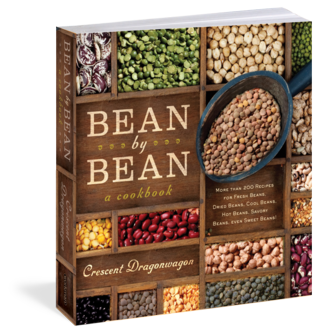

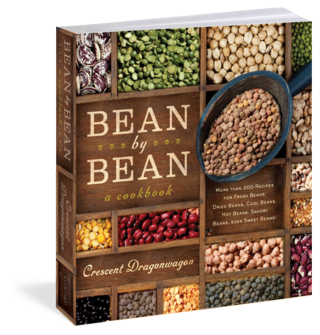

I've had my reasons. New book (Bean by Bean). Book tour. Elder care. Not home much. Blah, blah, blah.

I've had my reasons. New book (Bean by Bean). Book tour. Elder care. Not home much. Blah, blah, blah.

But, I do walk the talk writing-wise, pretty much. I do writing practice, daily or near-daily. And I do a lot of semi-thoughtful quick writing; a paragraph or two on the issue or experience or thought or or insight du jour --- on Facebook. These quick paragraphs are more like the majority of blogs, or micro-blogs, out there. (If you click that link you'll see it takes you a 'fan page'; which I just started. Facebook made me, refusing to allow any more 'friends' to my 'personal' page. Since I consider the cult of celebrity part of the DNA of the spawn of the devil, I am not happy about this. Anyway, that's why you're not seeing many of my paragraphs/'micro-blogs' there. Yet. And maybe one day all the language around 'social media' won't seem so distasteful to me that I have to keep putting it in quotes. Maybe. )

Thing is, as you know if you read me here regularly (or irregularly. That being my fault, not yours) what I do here are not that.

They're what my wise and funny friend Ronni Lundy calls 'blongs': 'blog' + 'long' equals 'blong.' They're what used to be called essays. And to "essay', of course, means, to try.

And these just take awhile, mostly. This kind of writing takes uninterrupted, open-space, free-range thought-and-writing time. Time to get it wrong. Time to get it  right. Time to figure out what it is you're trying to get. Just time.

right. Time to figure out what it is you're trying to get. Just time.

Exactly what you don't get on a book tour where, paradoxically, you are talking about your writing, or at least the subject of your writing, all the time. (It is the writer's need for uninterrupted time that led me, in the course of my life, to periodic stays at writers' colonies, and eventually to co-found one, the Writers' Colony at Dairy Hollow, in Eureka Springs, Arkansas. Another story)

But. Even blog-, or blong-wise, I haven't been a total slacker.

In addition to Nothing is Wasted on the Writer, I have another blog, which I keep up with even more sporadically. It's called Deep Feast: Writing the World through Food, and it focuses on culinary writing and the larger questions eating, cooking, and writing about them bring up. It too, like this blog, is usually in the 'creative non-fiction' (was there ever a more pretentious-sounding term?), or personal history, line.

And there, at Deep Feast, I wrote a blong only last month (which makes it practically current events for me, though for no one else in the online world). It's seemingly about my discovery of goongoo peas.

But it's really about why there's no such thing as a definitive cookbook. Or for that matter, a definitive book of any kind.

As such, it's also germane to Nothing is Wasted. So I'm sending y'all over there while I finish up the book tour and related stuff, as well as write the next post for her. And the rest of my life. Unpacking. Laundry. You know.

Not to give anything away, but I think the next post for here is going to be about the myth of getting caught up, and how it hog-ties us. A blong story, if there ever was one.

P.S. If you're interested in some of what the book tour bebopping included, here are some of the high points that've made it online. In February, I was on NPR's On Point with Tom Ashbrook, a stellar interview, who really, really takes the time to be well-informed on the subject and asks erudite and thoughtful questions. And, in late March, Sheryl Julian, food editor of the Boston Globe, wangled an invitation for lunch, and wrote about it here. It should be said that the wangling was not very difficult. I would frankly prefer to be talked to in my native habitat, over food. And Sheryl's an excellent, thorough, old-school, dig-deep journalist; she actually talked to people who knew me (and got a few hilarious quotes).

December 12, 2011

Are you a real writer? The sure way to find out...

It's 9:24 a.m.

I have to leave at 10:00 to drive a deeply depressed friend to her therapy appointment. I am in the middle of writing one of my long, thoughtful, typical essay-type posts, which my friend Ronni Lundy calls "blongs." I left it, and began writing this instead.

I have a bowl of Irish oatmeal beside me, cooked with diced apples, which melt to creaminess as the oats cook, studded with pieces of medjool dates, which also soften to caramel-like bits, added in the last few minutes. The bowl, brown and grey pottery, with visible finger-rings, was thrown by my late husband. If I lifted it up I'd see, on its bottom, his scratched-in signature: Ned Shank, 1971. Stirred into the finished Irish oatmeal is a heaping teaspoon of almond butter, and a drizzle of maple syrup, from the trees tapped by my nearest neighbor, here in Vermont.

I am going to see if I can write an actual short blog post, and get it done before I hop into the car to do my mission of mercy, which I both want, deeply, to do, and am slightly irritated at having to do (I have been hanging in there with my depressed friend for many months now. It's getting old. But I am ridiculously loyal, to my friend, and stubborn; insistent, internally, that I know this is part of her life process, and mine, and that she and I will get through it, and that it will someday have meaning).

I am trying to finish this because nothing in the universe, that I have found, makes me feel as "God's in heaven and all's right with the world," as writing, particularly when I finish a piece. (I accidentally wrote, and just found and corrected, "all's write with the world.")

I have 50 published books out: all with name, traditional publishers: HarperCollins (Harper & Row when they published me), Simon and Schuster, Macmillan (now also part of Simon and Schuster), Charles Scribners (now defunct), Workman. And I have one coming out with Little, Brown (leading at times to peculiar, hilarious, but truthful statements like, "I'm going in to have lunch with the Little Brown people tomorrow.")

But I don't believe, in my heart of hearts, that I am a real writer until I have written that day. That day, being each day. Being today.

It's the holidays. Should I go to a party that is large enough so that I don't know everyone and strike up conversation with a stranger, it is likely at some point he or she will say, "So, what do you do?"

And I will say, "I'm a writer."

"Oh," he or she will say. And then that subtle shift in tone. "Published?"

Meaning, are you a real writer or an amateur, just futzing around. Meaning, where do I put you on the one-up one-down scale. Should I be impressed (are you famous? have I heard of you?), interested and slightly respectful (oh, you write a column for the Brattleboro Reformer which I may have read) or merely polite (how interesting, excuse me while I get another deviled egg).

I say yes when so asked, because I am a published writer, after all. Yes. True. But if I haven't written that day, I feel, in my heart of hearts, like a hypocrite.

The outside world, in the form of real and imaginary people at cocktail parties, teachers, parents, and siblings, will tell you, directly and indirectly, that a real writer equals a published writer.

Except every writer was at some point an unpublished writer. And even every published writer returns periodically to being unpublished, during the time they are writing.

This is so obvious. Except, evidently, it isn't.

Twitter is a medium I use (I'm @cdragonwagon) and simultaneously like and loathe, in part because the same limitation of characters that forces you to be succinct and pithy also forces you to write "U" for "you" at times.

Here's the one sentence version of this post, as I put it on Twitter a few days back: "Act of writing makes U 'real' writer. O,U thought it was publication? In his lifetime,Van Gogh sold O paintings; was he a 'real' artist?"

I said above, vis a vis the location where I feel like a phony if I haven't written on the day --- any day --- when I'm asked about being a writer if I haven't written that day, "in my heart of hearts."

By which I mean, in that interior True North by which one steers; to which, if one is true, one feels in alignment, living life with purpose and integrity.

Veer a few degrees from that compass point, and one becomes a hypocrite in one's own eyes, whether or not the world notices (and it usually won't, until the degrees are so many that the degree of offness is blindingly evident).

At least I feel that way if I deviate by even a couple of degrees.

But not today.

For now it is 9:50 a.m. And though I have not finished my oatmeal, I have written.

Like one of the ads for one of the airlines used to say, "We earn our wings each day."

Today I earned my wings: I wrote. Therefore, I am a real writer.

It's a relief.

9:55 a.m.

All I have to do is hit "publish" and I will both a real and a published writer.

Again. Until tomorrow.

October 23, 2011

uncovering: a yak, a six-year-old, and some witches walk into a post...

The little girl who asked me the question was a first-grader then. Assuming she is still alive, she's 36 or so, probably with children of her own.

But our paths crossed just the one time. That was in 1982, in Atlanta, Georgia. I came to her class as a visiting writer. So I know her only as a six-year-old, and only from one interaction. In my mind she is today exactly what and who she was then: an adorable, very solemn little girl, with light brown skin and black hair caught back with pink barrettes.

The reason she's in my mind today has to do with children books and their illustrations. I have a new children's book, All the Awake Animals (Are Almost Asleep), coming out about a year from now, which will be illustrated by David McPhail. I am so delighted with what I have seen of the pictures so far that I have posted a few of them on Facebook. Which prompted a comment that reverbed me back to that little girl's question.

All the Awake Animals is my first new children's book to be released in almost a decade (for reasons I describe on a video here, made at a talk I gave about a week  after the book was accepted by Little, Brown... and in which I slip up in a ridiculous way at the end).

after the book was accepted by Little, Brown... and in which I slip up in a ridiculous way at the end).

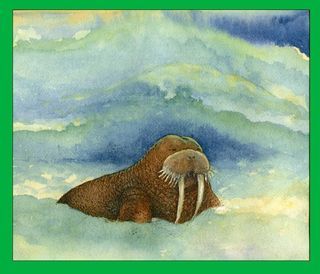

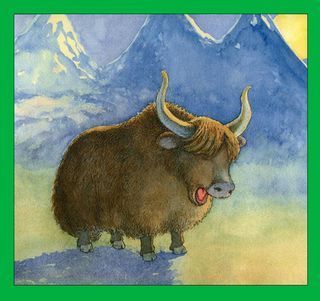

I am loving working with Little, Brown's Andrea Spooner, Senior Executive Editor of Books for Young Readers. She is one of the most attentive and respectful editors I have ever had; even when the discussion runs to, say, at what time of day and in what manner a vole, otter, lion, yak, walrus -- shown here catching "forty wet winks" after "wading into the waves"--- or an urubu actually sleeps. (An urubu is an African vulture; few animals start with "u".)

The book begins:

My little one,

Lay down your head

It's time for sleep

It's time for bed

You tell me,

"I'm not sleepy now,"

"Just try," I say.

You ask me, "How?"

After a few more exchanges, the mother takes the child on a slow, dreamy visit to 26 different animals, all in various stages of snooze or near-snooze. They go animal by animal, one for each letter of the alphabet, from Antelope ("asleep all the way to his antlers" ) to Zebra (who "just zzzzzzzs...") before returning to a final dozy reiteration of rhyme.

Andrea took a lot of time finding just the right artist, and she is taking a lot of time working with him, and me. In 40 years of working with different publishers, I can remember no other children's book editor who has ever involved me quite so much in the selection of the artist, and has engaged me so thoughtfully in discussing the pictures and my reactions to them.

Nor, for that matter, has that happened with any cookbook editor/art director (for non-photographic cookbooks, too, have 'spot art' and 'chapter openers' and while they are less essential than in a children's book, and though the reader may be only aware of them peripherally, these illustrations either do or do not enhance the words and recipes).

Yet this indirect collaboration I'm now experiencing with David is so good! It's so easy! It's so much fun! I wonder why, in  general, there seems to be, in many editors' minds, a separation-of-church-and-state thing about writers and illustrators?

general, there seems to be, in many editors' minds, a separation-of-church-and-state thing about writers and illustrators?

At any rate, I am deeply grateful. And, as I see the watercolors David is doing, I am delighted; exhilarated, even. Though perhaps that's not quite the right word, for the pictures are sleepy, cozy, dozy, soporific. You can hardly look at them and not start yawning, like yak is doing here: just what you want in a goodnight book.

Yet their perfection does exhilarate me. They are luminous and tender, but not anthropomorphic or cute. The textures --- of the animals' fur, feathers, hides, tusks --- are so vivid I can imagine children stroking the paper to feel them, and growing puzzled that they can see but not touch the softness or roughness. The backgrounds are soft, impressionistic dreamscapes, suffused with soft light; light which makes shadows, refracts on water, or pierces clouds.

As I say, I am so delighted with these pictures that I have been sharing a few of them, as they progress, on Facebook. First the sketches, now the almost-finished drawings / paintings. And my Facebook pals --- many of whom are readers, parents or grandparents, or artists themselves --- are also enthusiastic, and many have been commenting on them too.

It is in this context that Cathy Smith, who blogs marvelously at "Growing Curious", and who farms, cans and preserves at Curious Farm and sells at local farmer's markets in her area, just outside of Portland, Oregon, asked me

what is it like to have your story brought into the visual realm by someone else? since you're so comfortable in this publishing world, do you just go with the flow at this point, or does it stop your heart sometimes?"

Let's leave aside the fact that I don't think I or anyone else is exactly "comfortable" in the publishing world. Which is not only changing at this moment with dizzying rapidity technologically, but which has always been at least anecdotally on the verge of collapse, for as long as I can recall.

I still remember my mother, the writer-editor Charlotte Zolotow, who was active during the period which, we can say in retrospect, truly was children's book publishing's golden age, muttering darkly and scornfully about Harper & Row being taken over by "the Harvard MBA's" and "the eleventh floor" --- synonyms for management.

"Can you imagine?" she said once at the dinner table, indignantly, when I was young. "They want me to do something called an ROI!" "What's an ROI?" I asked; I was maybe 10 or 11. "I didn't know either, honey," said my mother. "It's --- " she could hardly splutter it out --- "It stands for return on investment!"

"Well, what's that?" I asked.

And thus, in what was said and the tone in which it was said, and what was not said, I learned business 101; and that it was implicitly in conflict with art, beauty, and purpose. I'm still trying to undo the imprinting on that one. I would like to break the paradigm/archetype of the impoverished artist or writer who lives in the garret. I would like to think that Mammon and the Muse can sit down and have at least an occasional cup of amicable tea, and some hot buttered scones, together.

Don't worry, I'm getting back to that little girl in Atlanta.

My fourth or fifth picture book, Katie in the Morning, was given to a very young artist who had never illustrated a book  before.

before.  This was in 1982/ Full-color illustrations were rarely done at the time; instead, colors were made using transparent overlays, a very tricky business, and in the hands of someone who didn't know what they were doing, could very easily result in muddied, unsatisfying hues. This artist's inexperience showed, and did not, I thought and still think, do justice to its text.

This was in 1982/ Full-color illustrations were rarely done at the time; instead, colors were made using transparent overlays, a very tricky business, and in the hands of someone who didn't know what they were doing, could very easily result in muddied, unsatisfying hues. This artist's inexperience showed, and did not, I thought and still think, do justice to its text.

But justice... who are we, finally, to say what it is and isn't? For, here's a remarkable thing about the present era's access to information: I'd  forgotten the name of the woman who did those illustrations, so I went downstairs to get a copy of the book (and, yes, the pictures seemed every bit as unappealing to me as they always had).

forgotten the name of the woman who did those illustrations, so I went downstairs to get a copy of the book (and, yes, the pictures seemed every bit as unappealing to me as they always had).

But... I Googled her. And there she was: Betsy Day, Illustrator. And my-oh-my has she ever matured as an artist! Take a look at those dancing chickens, for example, on her website. She does gallery work, too, and she's written and illustrated one title, Stefan & Olga, left and above.

Assuming I had written something with the right fit for her current style, I'd be delighted if she was to do one of my books today.

But, though I didn't care for her work on Katie in the Morning back in 1981, on reflection it is good that Harper & Row (this was before they were Collinized, as I like to say) took a chance on Betsy. Their doing so helped enable her to develop into the artist she has become. That is, one might say, a truly good ROI, with, perhaps, a whiff of "justice" in a cosmic sense. Yes, I wish they'd asked her to redo Katie, or ... Well, but I've lived long enough, now, to know that I haven't a clue as to the really big picture. I've kissed the dream of understanding why fully, about much of anything, goodbye.

Here's a slightly expanded version of how I answered Cathy Smith, on Facebook: I told her that when I had disliked the art that had been chosen for me, and about which I'd had no say,

... it was, and sometimes is, pretty unhappy-making. Some editors ask for and welcome feedback which they transmit, politely and kindly, one hopes, to the artist. Some do not. If I can have a beneficial effect and help improve, from my perspective, the fit of the art to the text, I do... If not, and I truly dislike the art, generally what I do is get very disturbed and unhappy about it, cry some, and then live with it. I get over stuff pretty fast. There are only a couple of books where I feel the pictures were truly disastrous; after all, the publisher, too, wants the books to be good as a whole and they do try hard, if sometimes misguidedly, to get the appropriate illustration. There was also one in which I really didn't like the mood of the pictures, though they were good --- just so not what I would have chosen.

That book was Bat in the Dining Room, well-executed by S.D. Schindler in a funny, cartoony style. These pictures are charming in their own way, I think now; I probably would have enjoyed them in someone else's book, or even a different one of my own. But in this one, I so wanted the mystery and wonder of night, such as Jerry Pinkney had created so rapturously in my Half a Moon and One Whole Star, and later, in his own recent retelling of Twinkle Twinkle Little Star. Though I never truly loved the pictures in Bat, I eventually came to peace with that one more easily than I did those of Katie in the Morning, which made me wince, and still do.

(If you should read this, Betsy, I'm sorry. Truly, I am. But I'm guessing you wince, too, as I do over some of my own early work. I hope we both accept these things as part of the process; impersonal, implacable, difficult, with exuberance and disappointment in something like balanced measurement. We must, though maybe it's presumptuous of me to say so: but we're both working artists, who've been at it awhile. And if we didn't get that this is how it is, often uncomfortably, we would've surely given up, no?)

Katie had come out around the time I paid the visit to that first grade class in Atlanta. Though I think children in 3rd, 4th, and 5th grade get much more out of a writer's visit than those kids in earlier grades (who still aren't too clear on the whole concept of "author" generally --- and why should they be, they're in the psychedelic, improbable mystery of being so young that anything... could turn out to be anything!), of course schools always want you to at least pop in and read a book to the youngest students.

And of course I always ask if there are any questions; though at that age, there usually aren't. It's more like, "Does anyone have any questions?" and a small face will look up earnestly and say, "I have a cat."

But that particular morning, that little girl in Atlanta did have a question. A real question, and, as I have said, she asked it with solemnity and gravitas. Her manner made me wonder later if she, literal as all children are, had perhaps been puzzling over it for weeks, as I remember puzzling over why "witches" were in the Pledge of Allegiance. ("And to the Republic, for witches stand...")

"Do you believe," that little girl asked me, "that it's true that you really can't judge a book by its cover?"

This was a question I had never been asked before, or for that matter since.

I thought about it.

"Well, " I finally said, thinking of Katie, "I wrote a story once that I really liked, but I didn't really like the pictures. So I guess, if you picked up that book, and you looked at the cover, and you put it down without reading the words because you thought the cover was ugly, I think you would have judged the book by its cover and made a mistake. So, yes, I think it is true that you can't judge a book by its cover."

Judging. These days I try to replace judging, and certainty, both of which are fixed and static, with curiosity and inquiry, both of which move, change, and flow. As life itself does, and with it, our perspective.

I would have sworn, based on those long-ago illustrations of Katie in the Morning, that Betsy Day had just called it quits. I am so deeply glad that this not the case, that she has grown into her talent, and her talent continues to grow.

And I am glad that I tell students in Fearless Writing that every piece of writing is essential to the writer, regardless of whether it works as a piece or not: because this is true. Seeming unsuccess is as important as seeming success in our lives, as artists and as human beings.

And I love the mysterious fact that somewhere, out there, is a 36-year-old woman who has no clue, no clue at all, that she lives forever as a child in the mind of a woman of whom she almost certainly holds not the faintest memory.

And I am glad my mother, now 96, who has now completely forgotten Harper & Row, was once so deeply passionate about books and art.

And I am glad that I neither accepted nor rejected her scathing views on ROI's, but continue to wrestle with them (a match I think is now taking place on the international level, with the Occupy Wall Street movement, by the way; in essence, can there be enlightened, good for people-planet-and-profitable capitalism, or not? "People" presumably including artists and writers and those who self-nourish from seeing or reading their work.)

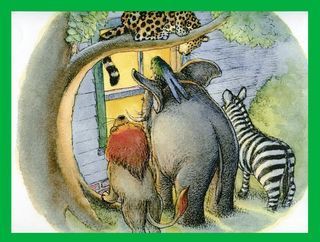

And I am glad to be witnessing David McPhail's illustrations move from sketches to completion: more flow and process. This is the best part of "what is it like to have your story brought into the visual realm by someone else" --- the art doesn't just 'illustrate' what you've put there but expands the story, in a way that is both compatible and surprising. I am amazed and delighted to see David's insertion of what my mother used to call "a visual sub-plot" --- in this case, the animals creeping to the now-sleeping child's bedroom window and peeping in.

Why are they there, those animals? To listen to the story the mother is telling, about them? Because, to them, a little boy is exotic and strange? Or perhaps they are not "really" there; perhaps the sleepy child is "only" imagining them. Who knows? I don't, and neither will the book's young readers. And this isecond story is what the artist has added, layering what I wrote with his own, subtly mysterious and charming.

And what expression is on the faces of those animals as the gaze into the window of the sleeping human child, jaguar hanging upside down to do so? Perhaps they gaze with longing? Perhaps curiosity? Maybe.

But, I think, certainly not with judgment.

You can't judge life by how it looks and feels at any given time; that is only its cover.

You have to open it up.

October 6, 2011

elegy for a tomatillo ... and Steve Jobs

He went back inside, and came out again through the French doors, leading to the garden, where I'd already gone. "Supposed to go down to 28 degrees tonight," he reported. "Yikes," I said, and we both returned to the kitchen to grab several large bowls and the yellow colander. Then back out.

David worked on the beans, which have been producing generously all season long, the pole beans, climbing their rustic tee-pees, tendril by tendril, at the edge of the garden, adding what to my eye is such charm, the

sunflowers behind them. He picked my favorites, the exuberantly abundant densely podded Spanish musicas. Then he picked the others: the flatter white and scarlet runner beans that are so good when cooked slowly, the rattlesnake beans, with their green purple-mottled pods, encasing white beans also mottled purple. Then he crouched to work on the bush beans: the limas, the Kentucky wonders, the yellow waxes, the black valentines (green pods, shiny black beans inside), and the royal burgundies (wondrously purple-podded, and though the pods turn green a few moments after they're submerged in boiling water, the water, after their cooking, turns turquoise, which keeps the wonder going, as far as I'm concerned).

sunflowers behind them. He picked my favorites, the exuberantly abundant densely podded Spanish musicas. Then he picked the others: the flatter white and scarlet runner beans that are so good when cooked slowly, the rattlesnake beans, with their green purple-mottled pods, encasing white beans also mottled purple. Then he crouched to work on the bush beans: the limas, the Kentucky wonders, the yellow waxes, the black valentines (green pods, shiny black beans inside), and the royal burgundies (wondrously purple-podded, and though the pods turn green a few moments after they're submerged in boiling water, the water, after their cooking, turns turquoise, which keeps the wonder going, as far as I'm concerned). I love beans, as you can tell. In fact my book about them, Bean by Bean , will be out early next year.

But. Given the quantities David was picking, I would clearly be canning, pickling, and freezing in the near future. (Below, last year's Green Tomato Mincemeat, which I'm about to make again, from my own Passionate Vegetarian)

While he worked on the beans, I turned my attention to the tomatillos.

I was thrilled, three years ago, to find tomatillo starts at the farmer's market. I love tomatillos (for those of you who don't know them, they're in the tomato family, usually bright green --- though there are purple varieties --- and protected by an elegant papery husk; and they are the stuff of salsa verde). I think I bought six or seven plants that first year, with little idea of how enthusiastically and messily they would grow and produce.

At harvest that year, after canning a dozen half-gallon jars of salsa verde and the same again of just plain tomatillo puree, for our household of two --- yeah, we have a lot of guests, true, but still --- I called it quits. When I added the pulled-up plants to the compost pile that year, I am embarrassed to confess I did so, consciously, knowing I was still leaving plenty of perfectly good tomatillos on the vine: me, to whom wasting food is morally repugnant. I begged the pardon of the plants, and every hungry person in the world, and the generous universe itself, for forgiveness as I discarded them. But I did discard them.

So, last year, I planted cautiously: just two tomatillo plants. They bore, but not with nearly the fervor of their kin the year before. They were far fewer fruits per plant, and, strangely, in quite a few cases the husk would grow full-size, but the tomatillo within it would be only the size of a cherry tomato. I ended up canning just 1 half-gallon and a quart or two... which I kept aside for what is now an annual tradition at the Labor Day Fearless Writing: the Whole Enchilada. Because one dinner at that event, of course, must be enchiladas, which I sauce in long beautiful stripes of red tomato salsa and green salsa verde, and I couldn't know how well the following summer's crop would bear.

This year I hedged my bets. I put in just three tomatillo plants, gave them a corner of the garden in which they could flop uninhibitedly to their heart's content, and basically left them alone, harvesting just a few to freshen up and round out the last year's canned ones, for the Whole Enchilada dinner in early September, which is too early to justify wholesale harvest.

Otherwise, I left them alone. That is, until tonight.

As David did the beans, I pulled tomatillo after tomatillo from the spreading, generous stems, many stems per plant. They bore, this year, as abundantly as they had that first year. I'd break off a stem, and pick the tomatillos from it. I'd drop the husk-wrapped fruits into the 2 1/2 gallon stainless steel bowl, then toss the

stem to the side of the garden to pick up later during the serious fall garden clean-up, which we'll do in a few days, at the same time we plant the garlic.

stem to the side of the garden to pick up later during the serious fall garden clean-up, which we'll do in a few days, at the same time we plant the garlic.(Plant garlic in fall; harvest the next summer... as I did, one hot, hot day a few months back, on my way up from a dip in our pond, as I passed through the garden. Silly picture, but so true to that moment.)

I brought one full bowl of tomatillos in from the cool darkening night to the warm, bright kitchen. I emptied it carefully onto the kitchen counter, returned to the garden, and began to fill the bowl a second time. There was still some light, the sky still recognizably blue, but it was growing darker, more chill by the minute. A sudden half-moon rose in what's east this time of year (here in this northern latitude, the directions change so radically, disorientingly, with each season). Very large, very bright, the moon was more cooly silver than golden, and a few wisps of haziness veiled it. Three or four small puffy pink clouds, still colored by the departing sun, hovered near the moon, seeming like slightly anxious handmaidens: "Is there anything you need?" "Is everything all right?"

Harvesting under this illumination, I suddenly thought of the Edna St.Vincent Millay poem my mother, now 96, used to quote when I was a child, the line "she weeds her lazy lettuce by the light of the moon" sounding in my inner ear as if she had just spoken it in her young mother's voice, getting across, somehow, how succulent those words were to her. My mother, who has forgotten every poem she ever knew, but who, paradoxically, seems to me happier moment to moment than she ever was when in her so-called right mind.

I pulled another large stem from the tomatillo plant I was working on, and, as I pulled the fuits off of it, completely unexpectedly, my heart gave a sudden contraction of grief. Because there, arching out from it, was another stem, covered with the robust fleshy leaves... but also, blossoms. Small bell-shaped bright orange blossoms, star-like in the night, dotting that whole stem... maybe fifteen of them.

"Awww," I called out to David. "I just found a whole lot of blossoms here. They didn't get to be tomatillos!"

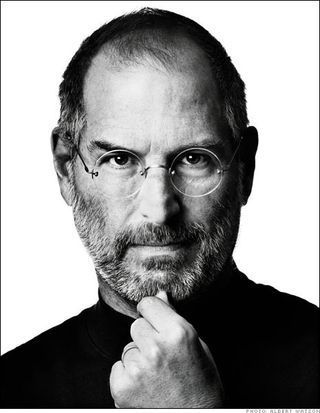

And then, surprising myself, I added, "I wonder if it was like that for Steve Jobs."

And then, surprising myself, I added, "I wonder if it was like that for Steve Jobs." "What?" asked David, in that startled, did-I-miss-something tone, which suggests if-I-didn't-miss-something-you-may-be-insane.

"I wonder if he felt like he still had all these blossoms that weren't going to have a chance to bear fruit."

As I continued picking, that thorn still in my heart, I thought about Steve Jobs, the little I know about him.

I'm still a PC user and I don't own an i-anything, though I can't count how many people I know who've had an Apple moment where the heavens opened up and everything stood revealed, and I have no doubt that one of these years I will have an i-something, and maybe my own Apple moment.

But I do have a mouse. And I do have a laptop. And I do know how much he revolutionized the world. And how much people who knew him, along with the countless many who didn't, revere not just his work, but him.

And then, there are all the things he said that are circulating now: About how he'd "wanted to leave a ding in the universe." And "... the only way to do great work is to love what you do. If you haven't found it yet, keep looking. Don't settle. As with all matters of the heart, you'll know when you find it. And, like any great relationship, it just gets better and better as the years roll on."

But his rolled on only to 56.

And from here, standing at the cusp of 58 and 59, blessed with work I love doing, I know that if I received a terminal diagnosis tomorrow, I would feel like one of the plants I was pulling tomatillos from: partially able to be harvested from, partially fulfilled, but with so many, many unpotentialized blossoms.

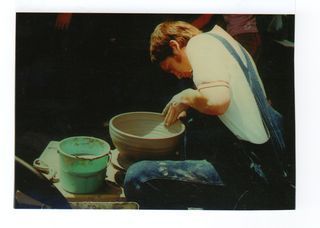

And, I guess inevitably, I wondered about Ned, about the seconds when his bicycle flew through the air before landing in and breaking the windshield of the oncoming vehicle --- if he had a chance to know,

wonder, regret all the things he was not going to have a chance to do. (Ned, right, as a 16-year-old, long before I knew him, throwing wheel pottery in high school. When we were affianced and went to meet his parents, he opened a door in their attic and showed me boxes of his pottery. "My dowry!" he said proudly. I still eat from his soup bowls).

wonder, regret all the things he was not going to have a chance to do. (Ned, right, as a 16-year-old, long before I knew him, throwing wheel pottery in high school. When we were affianced and went to meet his parents, he opened a door in their attic and showed me boxes of his pottery. "My dowry!" he said proudly. I still eat from his soup bowls). I talked to the young man whose pick-up it was --- this was early days, just a week or two after Ned's death; not six months later, when he decided to sue "the estate of Ned Shank" for "pain and suffering due to PTSD" --- on the phone. I told him I didn't hold him responsible; that from what I could tell, from the accident report, it was an act of God, and the laws of phyics.

Then I asked him a question I maybe shouldn't have asked. But I wanted to know, I wanted some clue: how did he feel? Did he know? How much? "Did you see his face, before the moment of impact?"

"Yes, m'am, I did. "

"And... did you get a sense of ... what was his expression?"

"It was like, 'Oh... crap.'"

But balanced against that is the story of the lovely woman named (and how poignantly this struck me) Grace. Grace was 2/3 small-town acquaintaince/ colleague, 1/3 friend, and she was in the car behind the pick-up which struck Ned. She got out, and sat with Ned in that two-lane road, as traffic backed up on both sides, until the EMTs got there.

She told me that when she first sat with him, bloodied and broken but still alive, she said, "Ned, this is Grace." I always wonder how he heard that; how, in that state, he interpreted the word 'grace'. And afterwards, from the first time Grace described the scene to me (very late that same night, after he'd died) to her words at his memorial, to the last time we spoke, identically: she talked about the feeling of peace that descended over the two of them.

And that, when she told him I had been notified, he repeated my name.

Ned's first children's book, The Sanyasin's First Day , had been published just six months before his death. One of the first condolence calls was from his editor, Judith. Judith is a person whose emotional affect is not so much flat as consistently placid, unflappable. For the first time, in the many years I had known her, I heard her express unbridled emotion. "He would have written so many more books!" she said between the sobs, gusts of feeling shaking her. "I just know he would've!"

And he would've painted and drawn countless more pictures. Curled up with me so many more times. Had so many orgasms, and contributed to mine. Closed his eyes in pleasure as he let the first bite of any dessert he particularly liked dissolve slowly in his mouth. Laughed so hard that his whole face scrunched up and all you could see of his huge eyes with their absurdly long eyelashes was the tiny edge of the lashes. Made, on days when he woke up, staggered down to the bathroom, first beheld himself in the mirror and saw his hair crunched from either side into a tall, odd thatch, a "Woo-hoo-HOO" sound, which we referred to as the call of the Great Crested Droon, and which he would make while standing on one leg, indeed, looking oddly like a very peculiar, leggy shore bird.

He would've done so much: in and of himself, but also for and with others.

But, like the tomatillo blossoms, now and forever, he would not.

Ned was 44. An early, killing frost.

Steve Jobs, 56.

xxx

One set of my present-day neighbors, Beth Kaplan and Jim Jordan, who --- with their daughter Stella --- live right down the hill from us here in Vermont, work for Antioch University of New England. Both Beth and Jim are in the Department of Environmental Studies.

Beth runs their graduate center in ecology and primate research, in Nyungwe National Park, Rwanda. She comes and goes from that country several times a year. At any given time, a couple of Rwandan graduate students live in Beth and Jim's downstairs.

Last Thanksgiving, we had dessert with Beth, Jim, their daughter Stella, William and Yves, the students staying with them, and a host of their other friends, in the educational, environmental, local and international communities in which they move. At one point, Yves and William and David and I were talking. They were astonished to learn that David was 71 (true, he looks young for his age). They were also astonished to learn I was 57 (true, I also look young for my age).

But their astonishment had little to do with looks.

"How old people live in your country!" exclaimed Yves. "In my country, 45 is old."

Perhaps a blossom isn't an immature fruit, but a blossom, perfect, orange, bell-like (if it is that of a tomatillo). Perhaps it is complete, completed, in itself.

Perhaps not.