Crescent Dragonwagon's Blog, page 2

April 21, 2011

whimper while you work: life-density, writing, very dark chocolate

First, let me say how humiliated I am that I haven't done a new blog post since (OH my GOD, this is ETERNITY in Blogland!) ... since last July.

Actually, I did do one. It was, juicily, about older babes who are still sex-positive in  their late 50's and onward, sometimes way onward. I number myself, gladly, among this group, despite being 58 (see left; the 'after', by David Koff). This is an age when, had you told me when I was a

their late 50's and onward, sometimes way onward. I number myself, gladly, among this group, despite being 58 (see left; the 'after', by David Koff). This is an age when, had you told me when I was a  teenager (see right, the WAY 'before', by Vernon Tucker), I'd still be desiring, enjoying, and having sex, I would have said 'ewwww'. You may have seen this post, in late March, 2011, but you probably didn't: I had it out there for about 15 minutes before I pulled it. (Here we have the down-side of being able to push a button that says 'publish', instead of working with an editor and having a delay of years, in the case of books, or months, in the case of magazine pieces, to reconsider, rework, and get an outside opinion).

teenager (see right, the WAY 'before', by Vernon Tucker), I'd still be desiring, enjoying, and having sex, I would have said 'ewwww'. You may have seen this post, in late March, 2011, but you probably didn't: I had it out there for about 15 minutes before I pulled it. (Here we have the down-side of being able to push a button that says 'publish', instead of working with an editor and having a delay of years, in the case of books, or months, in the case of magazine pieces, to reconsider, rework, and get an outside opinion).

It wasn't inhibition that caused me to pull it; rather, though it was a good post, I decided I hadn't quite said what I wanted to say in the way I wanted to say it. Sigh. If nothing is wasted on the writer, that includes drafts, and the hours of times spent on them, and other pieces --- any length, any genre --- which may or may not finally work out to one's satisfaction. Yet each one increases one's development as a writer. It's that old practice makes practice thing again.

So, I'm reworking the older-babes-in-sexland thing. Consider this reference as a preview of coming (yes, that was intentional) attractions. And, while I would have prefered ending this long near-silence with a bang (yes, intentional too), I am going to start instead with a whimper.

With two whimpers. Followed by a groan of a pleasure and ah-hah, now-I-really-get-it wave of observation. (All of which also pertain, at times, to sexual activities, now that I think of it.)

This first whimper is metaphorical: the subject of this post, chocolate- and writing-related, is seemingly much more minor than the highly-relevent-to-baby-boomers SHOUT of sexual seniority.

The second is a real, actual, literal whimper, one I remember making shortly before indulging in a little strictly legal but serious self-medication. Which, when you hear the circumstances, I think you'll agree was more than justifiiable.

This was was a while back, too: in the, oh gosh, probably late 1980's. If you think this makes both the pained whimper and its palliation memorable, you are right.

So memorable that it all surfaced as I read the following innocent, offhand Twitter post this morning, from @simmertildone: "I know many writers report that when running or driving or gardening, they're 'writing.' How about 'standing in kitchen eating brownies?' "

Well, yeah. Why would that be any different?

Digression: I would be remiss if, before telling you more about the whimpers et al which that tweet pulled for me, I didn't introduce @simmertildone, aka Marilyn Naron, a  little further. Marilyn (pictured left; from her site) lives in Lawrence, Kansas. She describes herself on Twitter as "Recovering pastry chef. Writer, blogger, dumpling-eater and chief dog-walker."

little further. Marilyn (pictured left; from her site) lives in Lawrence, Kansas. She describes herself on Twitter as "Recovering pastry chef. Writer, blogger, dumpling-eater and chief dog-walker."

She also has a blog, also titled Simmer Til Done. I will add that she A) updates her blog somewhat more frequently than I do, B) writes with a nonchalant, charming, hey-we're-just-hangin'-in-the-kitchen together personal voice, witty and gently self-deprecating, about C) not just food, with lust-wothy recipes that actually work, and musings on same, but stuff like her daughter, Josie, the writer Judy Blume, and the odd non-craft craft. Too, she happens to have a black Labrador named Cleo --- the same name as our family's black standard French poodle when I was growing up.

Something else about her blog: while really good, professional-quality photographs have become almost de rigeur in

food blogs, Marilyn's are over-the-top. You might drool over them; you might gaze at them as longingly as Cleo the dog does here, at some brisket (which almost though not quite looks good to me, and I've been a vegetarian for more than 30 years --- this is Marilyn's photo, obviously).

But she (Marilyn, not Cleo) also does drawings, too. Her Baker's Alphabet, which I think one of these years will develop into a children's book, if there is any justice, is what first led our paths to cross. See her sketch below. But that's another story.

Now you might have been wondering about how a pastry chef could describe herself as "recovering," which is going to slowly lead us back to the point. Marilyn elucidates this  statement on the "about" page of her blog: "I'm a pastry chef – but I don't work in restaurants anymore, so you can just call me giver of dessert happiness." She also gives more details on Lawrence, Kansas, "the coolest college town in America", which she calls affectionately, as perhaps many there do, "Larryville."

statement on the "about" page of her blog: "I'm a pastry chef – but I don't work in restaurants anymore, so you can just call me giver of dessert happiness." She also gives more details on Lawrence, Kansas, "the coolest college town in America", which she calls affectionately, as perhaps many there do, "Larryville."

As you'll see, I really, really understand the "don't work in restaurants anymore" bit. Which leads us back to whimpering. End of digression.

I have written here before about my former life as a writer-innkeeper (at Dairy Hollow House, in Eureka Springs, Arkansas), and the truly insane (as it appears to me now, from this remove) daily schedule I kept, more or less as follows:

Somewhere between 6:30 & 9:00 am: get up, breakfast, a little time with Ned.

9:30 am to noon: write

Noon: eat lunch, sometimes with Ned.

1:15 to 2:15 pm: nap (very occasionally, not nearly often enough, with Ned).

2:15 to 3:15: work out, then shower, dress.

3:55 pm-ish: walk to the inn, a few minutes away. As I wrote in that previous post " ...as I approached the inn's door, I'd feel my other, non-writer life, as an innkeeper, kick in."

4:00 pm: get into the inn's kitchen, and start cooking dinner for the evening's guests --- anywhere from 15 to 45 people.

5:00 pm: Ned would arrive, to maitre d' (a rare, if blurry, in-action photo of him, right... imagine! Phones still had curly cords, and look at that antique computer! Oh, Ned.)

7:00 pm: dinner at the inn; Ned "front of the house", me "heart of the house", waitstaff the intermediaries

8:30-9:00-ish pm: "make the rounds," as Ned used to call it, visiting with guests at the table usually as they were having dessert.

9:30-ish pm: staff dinner

10:00 pm at the earliest, 1 or 2:00 am latest, leave inn/restaurant/kitchen, Ned arriving usually an hour or so later

Any sane person who says, "I've always wanted to have a restaurant" should read this schedule as a cautionary note.

And I feel sure any person, of any degree of sanity or insanity, who has worked in, or is presently working in, a restaurant, is probably heaving a sigh, relating all too well, and maybe having their feet give a twinge or two in symapthetic recall.

And anyone, period, who didn't understand why Marilyn refers to herself as a "recovering pastry chef" --- well, now maybe you get it.

But: I was productive in those days. As a writer, as well as a cuisinere ('chef' always felt a little high-falutin' for what I was, but 'cook' a little too greasy-spoonish; 'cuisinere', French for 'cook', felt, maybe irrationally, just right).

With so very little time to write then, there was always a heavy-handed external  deadline: I had to go cook at the inn, in a very few hours. In memory, I did not waste time. I did not procrastinate much or at all. I did not play computer Hangman or Bedazzled like a person could do if they didn't have to be up at their restaurant by 4:00 (This is theoretical, not confessional, please understand. Just because I have a lot more time to write these days now than then, doesn't mean that I... Oh, okay, it is confessional.) (Left, me in the wonderful writing studio, Moonshine Cottage, where I worked so hard during the inn days. Will I ever have another writing room that suits me as well? Seems unlikely. I still have the sweater I wore in that picture, though, and the mug that's in my hand. Odd what lasts and what doesn't, isn't it?)

deadline: I had to go cook at the inn, in a very few hours. In memory, I did not waste time. I did not procrastinate much or at all. I did not play computer Hangman or Bedazzled like a person could do if they didn't have to be up at their restaurant by 4:00 (This is theoretical, not confessional, please understand. Just because I have a lot more time to write these days now than then, doesn't mean that I... Oh, okay, it is confessional.) (Left, me in the wonderful writing studio, Moonshine Cottage, where I worked so hard during the inn days. Will I ever have another writing room that suits me as well? Seems unlikely. I still have the sweater I wore in that picture, though, and the mug that's in my hand. Odd what lasts and what doesn't, isn't it?)

Back then, I think the writing time kept me cooking and the cooking kept me writing.

But of course those solitary mornings of writing rested on uninterrupted time. And that was the great gift Ned, my dear late husband, gave me, on an ongoing basis. (Left, on our wedding day.) For while he appeared at the inn at 5:00 (or at least, was supposed to; he was frquently  late, to the ire of our front desk people), he did all, or almost all, of the other stuff before then.

late, to the ire of our front desk people), he did all, or almost all, of the other stuff before then.

Other stuff like fixing things, doing repairs, maintenance around the property. Paying bills. Stacking the wood. Meeting with purveyors and staff. Occasionally firing or hiring someone. Covering for a dairymaid who had a sick child, or a front desk person on vacation. Doing legwork for the eternal, infernal City Council and Planning Commision and Parks Commission meetings that anyone who did anything in Eureka Springs, Arkansas, was periodically having to go before. Making sure vehicles worked, getting windowshields replaced if a rock dinged the glass. And on and on and on.

The minutiae that is the basal metabolism of life doubles when you are an innkeeper, if  you take seriously the safety, needs, and delight of your guests. Ned and I did. Ned also managed to scoop in civic duty and volunteerism; he himself headed up a comission, the Historic District Commission, known to us in-house as "the H-Dick." (Right, just about a month before he died, withe writer Pat Carr, cooking up big plans about the Writers' Colony at Dairy Hollow --- which is another 'nother story.)

you take seriously the safety, needs, and delight of your guests. Ned and I did. Ned also managed to scoop in civic duty and volunteerism; he himself headed up a comission, the Historic District Commission, known to us in-house as "the H-Dick." (Right, just about a month before he died, withe writer Pat Carr, cooking up big plans about the Writers' Colony at Dairy Hollow --- which is another 'nother story.)

Actually, I don't know how either of us did it.

Where this already tenuously balanced schedule fell apart for me was when or if Ned was out of town. Which brings me to the literal whimper.

One morning he was out of town. It was spring, almost Easter, or Mother's Day --- one of those Sundays where there's a big-ass brunch crowd was coming up, occasions where we dropped brunch into the usual go-round of meals we served the general public (as opposed to just inn guests). I think also it was a Friday morning. Since Eureka Springs was and is primarily a town built around a weekend influx of visitors, I knew I'd  be cooking late and hard that evening, and Saturday, with that killer turn-around-get-up-early-and-do-a-bang-up-brunch on Sunday.(This picture doesn't exactly match, but I've been wanting to use it for awhile, and it is of a brunch at the inn, held circa 1980 as a fundraiser for the Arkansas Literacy Foundation. You can see me, seated, the strap over my white-shirted shoulder. And you can barely see my mother, Charlotte Zolotow, cattycorner to the right, gray-haired. Sitting at the head of the table? Then-Senator Dale Bumpers. And standing? You guessed it: a very young, impassionaed, articulate Hillary Clinton.)

be cooking late and hard that evening, and Saturday, with that killer turn-around-get-up-early-and-do-a-bang-up-brunch on Sunday.(This picture doesn't exactly match, but I've been wanting to use it for awhile, and it is of a brunch at the inn, held circa 1980 as a fundraiser for the Arkansas Literacy Foundation. You can see me, seated, the strap over my white-shirted shoulder. And you can barely see my mother, Charlotte Zolotow, cattycorner to the right, gray-haired. Sitting at the head of the table? Then-Senator Dale Bumpers. And standing? You guessed it: a very young, impassionaed, articulate Hillary Clinton.)

But back to the day of the whimper, when Ned was out of town. Although he may have been just in Iowa, seeing his parents, if memory serves this was one of his longer trips.

Many years, if we could afford it, he went for two weeks or so to South India, a place where, improbably, he felt wholly at home; a place he so loved that he had wanted his ashes put there (as I did, in fact, in the Pamba River, right, as he had requested).

I have the feeling that this particular Friday was in the middle of such a trip; I do remember he was not available even by phone.

In summary, then, a long, very long, weekend, made longer by whatever would fall to me with Ned being gone. I knew that Friday morning would be my last alone-time/writing time for the next several days. So I was camel-ish... drinking long and deep at the oasis of solitude, because it was going to be awhile.

Except. I was interrupted mid-drink. That morning was one of those where everything that could happen, did happen, most of it typically in Ned's bailiwick. A Dairymaid

called to say that tehe toilet in Summer Meadows (left) toilet was backed up. Ned could have unblocked it; I called a plumber. Then the front desk called; Becky, Ned's replacement as maitre d', who was going to be in in the late afternoon, had some kind of family emergency; who did I suggest we call to step in as replacement for her? Then the front desk called again; didn't I remember that Rose, the prep cook, had a doctor's appointment and had to leave early, meaning I would have to come in early, to prep for the dinner we'd be serving (and I'd be cooking) that night? Well, no, I hadn't remembered. (Had I been told? If so, I hadn't written it down. Mistake.)

called to say that tehe toilet in Summer Meadows (left) toilet was backed up. Ned could have unblocked it; I called a plumber. Then the front desk called; Becky, Ned's replacement as maitre d', who was going to be in in the late afternoon, had some kind of family emergency; who did I suggest we call to step in as replacement for her? Then the front desk called again; didn't I remember that Rose, the prep cook, had a doctor's appointment and had to leave early, meaning I would have to come in early, to prep for the dinner we'd be serving (and I'd be cooking) that night? Well, no, I hadn't remembered. (Had I been told? If so, I hadn't written it down. Mistake.)

Okay, I remember thinking as I struggled with resentment at having to leave my precious cocoon early; I might as well try to get in a good space about all this, I'm going to have to do it anyway, and I want good vibes in my heart and in the food I cook, yes? Yes. I thought all this as I opened the French doors from my studio to step out on the porch and walk across the valley to the inn. Or, wait, should I take the car? I'd probably be prettty damned tired by the evening's end...

That's when I saw, on the doormat, a gift from Z-Cat, the then-resident calico: a small dead bloodied snake. Oh-kay. Shake off the doormat, dropping the dead snake into the shrubbery.

And then, I looked down to to the Chevy Blazer, parked below in the driveway: ah yes, of course. Flat tire, passenger's side. Well, I was going to walk to the inn anyway, right?

When I got to the kitchen, David Crough, our erstwhile handyman, popped in to tell me the Eco-lab repairman who was supposed to have come the Monday before and put in a replacement part had not, in fact, come on Monday, and the odds were slim or none that we could get him on the Friday before a holiday weekend which meant the odds were also slim or none that we would have a working commercial dishwasher on this upcoming, particularly busy weekend.

This was the moment I whimpered.

I remember clearly exactly where I was: facing the long, stainless steel table in the kitchen, my back to the little window where guests could look in and I could look out. My feet were on the webby black plastic matting that, at the end of each evening, got run through the now non-working Eco-lab. I remember that it was about 11:00 in the morning.

And suddenly one clear, urgent thought clear appeared as if it had unfurled in 36-point lettering on a screen in my mind above my head. It was this: "I wonder if we have any Double-Density in the walk-in?"

Double-Density was Double-Density Chocolate-Mocha Walnut Torte, one of our two go-to regular chocolate desserts at the inn (the other was Chocolate Bread Pudding Maurice, with Raspberry Sauce). Double-Density was a very adult chocolate dessert; really, you ought to've been over 21 to order it.

It was a very, very bittersweet moist chewy cake with a little inn-made coffee concentrate added to the batter; something like a very rich, extra thick brownie in texture, baked in a round, deeper than usual cake pan. When we reversed it out of its  pan, we iced it with a rich-as-sin, velvety-smooth, also very, very bittersweet glaze, shiny-glossy, pretty much just bittersweet chopped melted chocolate (Vahlrona, we used) and sour cream. Fairly liquid when its main ingredients were first whisked together, the warm glaze was poured over the cake. There it firmed nicely; just enough to set, yet soft enought to stay menltingly voluptuous. And toasted walnuts, hand-chopped, pressed into the glaze around the cake's sides, completed the cake. (I know you'd like a picture. I don't have one. I am not going to make a D-D now in order to take one. But... the Harvard Square, left, made by famed chocolatier L.A. Burdick, is pretty durned similar in taste and texture, though it's much more refined-looking than our D-Ds were; too, the D-D's were cut in triangular wedges. The L.A. Burdick in North Walpole, New Hampshire, is about a 20-minute drive from us here in Vermont, making Harvard Square or any number of wondrous pastries or confections a dangerously doable local possibility at any time.)

pan, we iced it with a rich-as-sin, velvety-smooth, also very, very bittersweet glaze, shiny-glossy, pretty much just bittersweet chopped melted chocolate (Vahlrona, we used) and sour cream. Fairly liquid when its main ingredients were first whisked together, the warm glaze was poured over the cake. There it firmed nicely; just enough to set, yet soft enought to stay menltingly voluptuous. And toasted walnuts, hand-chopped, pressed into the glaze around the cake's sides, completed the cake. (I know you'd like a picture. I don't have one. I am not going to make a D-D now in order to take one. But... the Harvard Square, left, made by famed chocolatier L.A. Burdick, is pretty durned similar in taste and texture, though it's much more refined-looking than our D-Ds were; too, the D-D's were cut in triangular wedges. The L.A. Burdick in North Walpole, New Hampshire, is about a 20-minute drive from us here in Vermont, making Harvard Square or any number of wondrous pastries or confections a dangerously doable local possibility at any time.)

Curiously, my always-active sweet tooth largely abated during the restaurant years. I suspect this was because I did so much baking and dessert-making and plating I got sated by osmosis. My taste, after a long night working the kitchen, ran to the cool, tart, icy sorbets we made in-house (the basil being my particular favorite, followed by the ginger).

But. On the rare night when I really wanted a serious dessert, it was always an after-dinner, late night thing.

And on the really, really rare occasion when I had a yen for a serious sweet midday, it would be after lunch, maybe with a cup of hot tea in the late afternoon. (Still true, to this day.)

For I didn't eat sweet stuff early. Still don't. Not ever. No continental breakfast or danish for me. Have, usually, something proteinaceous, some form of whole grain, and a piece of fruit: typically, a soft-boiled egg or some sauteed tofu, a piece of multi-grain toast, half a fresh grapefruit or a fresh orange or a cup or so of berries. That combo, varied slightly, seems to be just about the perfect fuel for me.

But that particular morning in the way-back, it was 11:00, lunch still a good hour and a half away. Yet stressed beyond endurance, what appeared?

"I wonder if we have any Double-Density in the walk-in?"

Without hesitation I walked across the concrete floor, past the Eco-lab, up the one step to the pantry. Turned left at the bin of onions and the potato bin, past the shelves loaded with jewel-like homemade/inn-made jams and preserves, and to the walk-in, pulling up on its long handle.

And there it was. Two slices left, from the day before yesterday, so it wasn't going to be served tonight anyway.

I carried the pan back to the stainless steel table. I cut a thin slice off one of the two large slices, got out a fork, and put a bite directly in my mouth.

And as immediately as a sedative injected directly into a vein would hit, I instantly felt noticeably, remarkably better. Ahhhh. I mean: as that sugar-chocolate-buttter combination, at the verboten time of day, melted into my tongue, at that milli-second it acted like a drug. Calm and soothe kicked in. I'm sure I closed my eyes for a moment, easing into that sudden Laz-Z-Boy of relaxed feelings and pleasureable sensation. And that was when I let out that soft groan of relief.

But even as I stood there, relieved, drugged with and by chocolate, I was at the same time having the ah-hah moment, with the part of me that stood outside watching and observing.

Being a food-writer (and cuisiniere) I knew cognitively something about chocolate. That its family name is theobroma, which means food of the goods. That in Aztec society priests, warriors and royalty drank a thick, frothy, bitter beverage called chocolatl/xocolatl. That this was cooked to melt the chocolate but served cool, and was  spiced with chiles, vanilla, and achiote. It was said to be an aphrodisac, a stinulant, an elevator of mood; it was said to strengten one, and banish fatigue. I knew Montezuma (right) supposedly drank 50 small golden cups of it a day; his court as a whole is credited with downing 2000 cups daily. (But, I always wonder when I read figures like this: who was there actually counting? Are we supposed to believe the accounts of conquistadors, as notable for their bragging as their cruelty?)

spiced with chiles, vanilla, and achiote. It was said to be an aphrodisac, a stinulant, an elevator of mood; it was said to strengten one, and banish fatigue. I knew Montezuma (right) supposedly drank 50 small golden cups of it a day; his court as a whole is credited with downing 2000 cups daily. (But, I always wonder when I read figures like this: who was there actually counting? Are we supposed to believe the accounts of conquistadors, as notable for their bragging as their cruelty?)

Anyway, I knew that recent neuroscience had borne most of this out. That chocolate contains a host of phyto-chemicals associated with mood, emotion, addiction: though I couldn't have named all of them offhand, I knew that at least four of them --- phenylethylamine, theobromine, anandamide and tryptophan --- did trigger mood enhancent, via neurotransmitters in the brain's own private pharmacy. Phenylethylamine, for instance, is a brain-manufactured chemical similar to amphetamine, kicking off feelings of giddiness, attraction, euphoria and excitement, while phenylethylamine open's the brain's apothecary to release pleasureable mesolimbic dopamine ( a substance which, by the way, peaks at the moment of orgasm; there you go). Tryptophan is an amino acid associated with calmness and relaxation, while anandamide triggers a mild version of goofy well-being that some compare to a mild marijuana high. Yet the theobromine, plus a little caffeine (much less in a cup of coffee) balance things out with their wakifying effect. To boot, it has more anti-oxidants than red wine, or green or black tea.

I knew all that about chocolate abstractly. But until that controlled-substance-like first bite, I had never experienced it. I've heard it said that however true something is, if you merely believe it, it's a lie. The truth comes only via experience.

So there it was: the wham of that chocolate kicking in, side by side with epiphany. Oh! Now I know what all that theobromine stuff is about, and what the heck do you know - it's true!

(And although I didn't know it them, chocolate was also going to be discovered to have a prophylactic effect on heart disease, promoting heart health in effect by Roto-Rootering the arteries.)

And yet, did the exact what and why of theobromine at all really matter to me? Not much. Not at that moment. As Emily Dickinson said:

The pedigree of honey

Does not concern the bee;

A clover, any time, to him

Is aristocracy.

That stressed-out morning, in time, place, and circumstances utterly removed from my  present life except by memory, that glorious Double-Density kindly, sensually played clover to my bee, and made it possibile for me to begin that intense weekend un-freaked-out.

present life except by memory, that glorious Double-Density kindly, sensually played clover to my bee, and made it possibile for me to begin that intense weekend un-freaked-out.

Un-freaked-out, I called the Eco-lab people, threw myself on their mercy, and got them to come out and fix the dishwasher. Meanwhile, David Crough changed the flat tire, and I started cooking.

So. In answer to Marilyn's tweet: yes, while I do mentally 'write' while walking, weeding, driving, I also, as this post proves, do it 'standing in kitchen eating brownies.' Because, when don't I do it?

Even if there is a 25-some year gap between the two, it --- one's whole dense, bittersweet, nut-studded, messy, satisfying wedge of experience --- remains alive and vital somewhere within, waiting to be called forth by the act of putting it into written words.

For nothing is wasted on the writer.

P.S. The recipe, please... this is from Passionate Vegetarian.

DOUBLE-DENSITY CHOCOLATE-WALNUT ESPRESS0 TORTE

Serves 10 to 12

Chocolate for grown-ups: no-kidding, we-really-mean-it, bittersweet; an intense chocolate experience, with a faint touch of coffee. Make it with cold-filtered coffee concentrate if you use such a system, or do a quickie version using concentrate from freeze-dried coffee crystals. It's a one-layer, intentionally very heavy cake; please note there's no baking powder or soda. Fairly simple as tortes go, its dense, moist fervently chocolateness put it is right up there. Be sure to pay attention to the notes on pans and baking time. And try the variations, especially the Chocolate Torte Ibarra.

8 ounces best quality unsweetened chocolate

1 cup butter

4 tablespoons boiling water

3 tablespoons freeze-dried coffee or decaffeinated coffee crystals

5 eggs

3 cups sugar

2 teaspoons vanilla

1/4 teaspoon salt

1 1/2 cups unbleached white flour

oil spray

1 recipe Creole Chocolate Icing, below

2 cups walnuts, toasted and chopped

Preheat oven to 375.

Melt unsweetened chocolate and butter together over very low heat in a heavy saucepan, stirring near-constantly. Remove from heat and set aside to cool for a few moments.

Meanwhile, combine boiling water with freeze-dried coffee or decaffeinated coffee crystals to make a thick coffee syrup. Set this aside.

Set up an electric mixer, and add eggs, sugar, vanilla, and salt to the bowl. Beat together, on high speed, at least 8 minutes, or until light, fluffy, and nearly doubled in bulk. (A hand-held mixer takes a little longer than a stand-type mixer).

Add half the coffee concentrate (the remainder goes into the icing), and the somewhat cooled chocolate-butter mixture, and beat until ingredients are combined.

Remove mixing bowl from stand or put away hand-held mixer. Stir in by hand, using a wooden spoon, the unbleached white flour.

Spray a 10-inch round layer cake pan, preferably one with fairly deep sides, very well with oil. Do not substitute a pie tin, or any round pan with curved sides; do not use a glass pan.

Turn batter into prepared pan, and bake about 35 minutes, or until surface is dulled and edges of cake have started to pull away from pan. It will still look a little underdone in the middle; ignore this. Do not overbake this cake; its moistness is an essential part of its charm.

Leave cake in pan for ten minutes after baking. Run knife around edge of pan and reverse onto rack. Let cake cool completely, and ice with Creole Chocolate Icing, pressing toasted walnuts into the top and sides of cake. Serve at room temperature or slightly warm.

Creole Chocolate-Espresso Icing

Makes Enough for 1 Double-Density, with a bit leftover

Though simplicity itself to make, in flavor and texture this is the most sophisticated and divine icing you will ever taste. Astute Dairy Hollow readers will recognize it as a variation of one which appeared in our first cookbook. Very bittersweet --- again, adult chocolate, not kid stuff. Once you discover this you might not make any other chocolate icing, ever.

12-ounces semisweet chocolate (either chips, or diced squares of semisweet)

1 cup sour cream or whole milk plain yogurt

1/2 teaspoon vanilla

Leftover coffee concentrate from above recipe ( 1 1/2 to 2 tablespoons)

Melt the semisweet chocolate over hot water, stirring often.

When smooth, remove from heat and stir in sour cream or whole milk plain yogurt, vanilla, and coffee concentrate.

Beat by hand until smooth and glossy. Let cool, stirring occasionally, until of spreading consistency, about five minutes.

Pour/ spread over cooled torte.

Variation:

Bittersweet Chocolate Torte Ibarra : Mexico's favored with-chocolate combinations are brilliant, unique, complex: ground almonds, canela cinnamon, and distinctive Mexican vanilla extract. I developed this excellent, even more rich variation of this cake to take advantage of these complex, multi-layered flavors as my contribution to a South of the Border menu'd dinner benefiting the Arkansas AIDS Foundation, with the flavors, held at Eureka Springs' Center Street South, now Caribe. It's now neck and neck with the previous as my favorite chocolate torte.

First, coarsely chop 2 cups whole almonds into chunks in the food processor, and toast them at 350 about 8 minutes or until fragrant and lightly browned. Return them to the processor and pulse again, until they are a ground to a coarse powder. Set aside.

Now, follow the previous recipe, but omit the walnuts, as well as the coffee in both cake and glaze, and substitute pure Mexican vanilla, available at any Hispanic grocery, for the conventional vanilla extract. Cut the flour back to 1 cup. Add, with the flour, ½ teaspoon canela cinnamon (available in Hispanic groceries, and sometimes in bags at the spice sections of supermarkets), and ½ cup of the toasted almonds. Bake the cake, and make icing, as directed. Press remaining toasted almond powder into top and sides of frosted torte.

July 10, 2010

practice makes practice: part one

"Practice makes perfect." We've all heard it. Many of us have said it. But what a damned lie it is! And what assumptions that damned lie makes!

That there is "perfect", first off, and that once you've reached it, you've reached

it. That there is a clear linear progression. It goes from where one is (imperfect) through "practice" (an activity undertaken solely to achieve a clear, previously decided-upon goal, perfection) to where one should be (perfect). (Pictured above : the harpsichordist Wanda Landowska, who had

it. That there is a clear linear progression. It goes from where one is (imperfect) through "practice" (an activity undertaken solely to achieve a clear, previously decided-upon goal, perfection) to where one should be (perfect). (Pictured above : the harpsichordist Wanda Landowska, who had something remarkable to say about practice, and who we'll meet later in

this post).

"Practice makes perfect" also contains many implicit questions. But it answers not one of them. Questions such as: If I get to 'perfect', what then? Where's the next? Am I just supposed to stay perfect once I've achieved it? Is this perfection static, final? And, once I have made it to perfect, do I have to keep practicing to stay there, or not?

I much prefer the truth: practice makes practice.

This elegant, accurate, precise maxim is not original to me. And whenever I use a

direct quote of someone else's piece of wisdom, I like to give attribution. But here's the problem with this one: I heard it from a woman named Susan, whose last name I don't know, and whose phone number I don't have. She said it to me after a Powerseed Yoga class with Sandy Curry almost four years ago ( Sandy pictured left; I took with her weekly, sometimes a couple of times a week, for four years, in Walpole, New Hampshire, until she moved to Philadelphia about a year ago. I am not the only student of hers who still grieves her departure.)

direct quote of someone else's piece of wisdom, I like to give attribution. But here's the problem with this one: I heard it from a woman named Susan, whose last name I don't know, and whose phone number I don't have. She said it to me after a Powerseed Yoga class with Sandy Curry almost four years ago ( Sandy pictured left; I took with her weekly, sometimes a couple of times a week, for four years, in Walpole, New Hampshire, until she moved to Philadelphia about a year ago. I am not the only student of hers who still grieves her departure.) After this particular class, Susan and I were discussing some poses neither of us had been able to come close to executing that day, among them, for me, Crow; I couldn't even get one foot off the ground.

And Susan said, "It was an off day for me, too, I couldn't even do Tree without standing next to a wall for balance. But, as my old yoga teacher used to say, 'practice makes practice.' "

Like a stone thrown in a pond, I watched the ripples of this statement, delivered so offhandedly, spread out and out into my understanding. I'm still watching. I'm still understanding.

This statement comes up often in my internal, eternal dialogue with myself (you know, the conversation within, in which all of us engage in constantly). Time after time, in activity after activity.

For instance: When I just don't want to work out or go on a walk but do anyway, sometimes turning out to enjoy it midway through, sometimes resenting every step or bicep curl, but almost always feeling glad I have done it afterward: I find myself thinking "practice makes practice."

For instance: When I procrastinate about writing, finally start writing, find writing that day like bicycling through hot tar, am sure that what I've written is flat, [image error]contrived, lifeless... When I find, sitting down to write the next day, that what I had written the day before was actually pretty good and that it takes a little less angst to get into it... When I find, the day after that, that I leap into writing as eagerly as I dive into the chilly pond on my property on a hot day, a thoughtless,

hungry, OH-I've-been-waiting-for-this plunge, quickly losing all sense of self, time, or evaluation in the act itself...Only to repeat the whole cycle on the next writing project...

Again, considering this, I find myself thinking "Well, you know, CD, you're never done, you're never there, it's practice makes

practice." (Our pond, pictured above, photographed by David R. Koff: been spending a lot of time in it, this exceptionally hot July of 2010).

For instance: When I feel anxious --- about the perennial sense of not-enough-time, the sometimes-sense of not-enough-money, and the brand-new and at times exceptionally ugly dispute that is looming between my brother and myself about my 95-year-old mother's care --- I think, first, "Why is it, that since I know anxiety is part of the process, and is an unhelpful emotion, that I'm still so affected by it? Why haven't I learned to accept it and just not get too wrapped up in it?"

And then I think, second, "Knowing how it works doesn't exempt you from it." (After all, just because you're an electrician doesn't mean you dont have a fuse occasionally blow. Just because you're a plumber doesn't exempt your pipes from freezing if the winter's cold enough).

And then, third, I think, "Oh. Right. Practice! I just get to practice what it's like to hang out with anxiety some more, not worry about getting over it. Feel it, but don't let it run the show. Use it. Practice. Practice makes practice."

I often think of this, too, when in conversation with others.

When my friend M., pregnant with her first child, said to me, "I just don't know if I'm ready to have a child," I said. "Honey, I don't think anyone's ever ready for anything big. Not beforehand. Doing it makes you ready. Being a parent is the only thing that really teaches you how to be a parent."

This is advice I have more or less given for years when anyone tells me they don't feel ready to get married, study in a foreign country, read their writing aloud to others, or quit their job as a dental hygienist and become a landscape artist.

Because I deeply believe that doing something is what teaches you how to do it.

I'm not saying you shouldn't take classes, read books, develop business plans, talk  to others who've done whatever it is you want to do but feel unready for --- I'm just saying, if that's all you do, if you wait till you feel fully ready to do it, you probably never will. (Left, cellist Pablo Casals, another great practice devotee, who we'll meet below)

to others who've done whatever it is you want to do but feel unready for --- I'm just saying, if that's all you do, if you wait till you feel fully ready to do it, you probably never will. (Left, cellist Pablo Casals, another great practice devotee, who we'll meet below)

And if you do feel fully ready, well, I think in most cases you are probably the proverbial apple cart. Get ready (not that it's possible to get ready) to be knocked over.

And being knocked over teaches you how to be knocked over - and how to get up again, paradigm altered. Practice makes practice.

I knew, pretty quickly, that "practice makes practice," which was

teaching me so much, would be incorporated into my work as a

teacher (for instance, in the Fearless Writing workshops I teach; and of course it became a cornerstone of Build Your Writing Practice).

So naturally I

had to find out to whom to attribute it.

The next time I ran into Susan was on a cold day several months later, outside the Saxtons River Village Market.

I was coming out, with two containers of Liberte Yogurt in an environmentally-correct canvas sack. She, holding her two canvas sacks, was about to go in. The first snowflakes of the season flew. We greeted each other. I said to her, quickly, because it was cold, "Hey, Susan, I've been wondering about something, and I was hoping you could clear it up for me."

She said, "Yes?", drawing her black coat around her a little more closely.

"You remember that thing you told me about practice, after Sandy's yoga class back in, oh, it must have been August, September?"

She looked at me blankly. "Hunh?" she said.

"You know, that thing you told me your previous yoga teacher told you. About how 'practice makes practice' ? "

She said, "I'm sorry, Crescent, I don't remember this at all."

"Well, what was the name of your old yoga teacher?"

She said, shaking her head, "I'm really sorry, but I have no idea what you're talking about. And I've taken yoga with a lot of different people. "

I said, "Well, thank you anyway." We said our goodbyes. She went into the market and I went back down the bricked ramp to my car. Perplexed: I knew she had said that to me.

I'd first met Susan at the home of my neighbor Peter; they were intermittent friends. I asked him for light-shedding. "Oh," he said, with a dismissive flutter of the hand, "her memory has a tendency to come and go."

So, dear person, whoever you are, who told Susan "practice makes practice," and dear Susan, who, though you've forgotten it, passed this on to me, thank you.

Or maybe I should shortcut all this and just say, "Thanks, Universe. I needed that. Much appreciated."

Here is what the great Polish-born pianist Arthur Rubenstein

(pictured left) said

about practice.""\When I don't practice for a day, I know. When I don't practice for two days, the orchestra knows. When I don't practice for three days, the world knows."

about practice.""\When I don't practice for a day, I know. When I don't practice for two days, the orchestra knows. When I don't practice for three days, the world knows."

And here is what another great Polish-born musician, harpsichordist Wanda Landowska (pictured at the top of this post) said on the subject: "I never practice, I always play."

And when the New York Times asked the equally

great Spanish-born cellist Pablo Casals (also pictured above) why, at age 93, he continued to practice three hours a day, here's what he said: "I'm beginning to notice some

improvement."

The great American-born trumpeter Wynton Marsalis also had a lot to say about practice. In fact, he wrote an article about it (very trumpet-playing specific) back in 1987, early in his career. But as time went on, in interview after interview he continued to allude to the importance of practice. He later refined his views into 12 rules for practice. He stated and restated them many times, in many different ways (as you might expect from a master improviser). Here are my Wynton favorites, cobbled together from several of his iterations:

Focus while practicing.Relax. Practice slowly. Take your time. You can't be in a hurry if you're going to get better.

Practice things you can't do. Don't rehearse your instincts.

Don't try to impress those that can hear you practicing.

Always give maximum expression; invest yourself, participate. Don't hold back.(Did you find Wanda Landowska's statement cryptic? I think Wynton is saying exactly the same thing here)

But as you probably noticed, what all these greats are practicing is music.

Do writers practice, too? If so, how? Any why do we rarely hear about it?

What is the difference between "practicing" writing and writing? Is there a difference?

Why do we assume that musicians of course need practice --- we expect that a person who picks up the violin for the first time will produce squeals and squawks, not concertos --- but seem, unconsciously, to believe that those who want to write (especially if the 'those' happens to include ourselves) ought to be able to more or less nail it the first time out?

Does this have any relation to why we never hear about "musician's block"?

I think I have some provisional answers to all these questions.

And (with 50 published books to my credit and God knows how many unpublished ones, having worked with and known hundreds of writers, both as colleagues and as students) I know I can tell you with some authority about some of the ways various writing practices look, even when they're not called practices by their practitioners.

But that will have to wait for a few weeks, say, till the end of July.

Because this concludes my own writing practice for today.

June 20, 2010

a sound of wings unseen, inadvertent wisdom: a fathering day post

Walking yesterday, up near Frazier's sugar shack here in Vermont, I heard an animal rustle in the underbrush edging the woods by the gravel road. Though I stood stock-still and watched, I couldn't see what it was. Too large for a chipmunk or a squirrel, smaller by far than a deer, I was left only with the sudden sound of its movement.

But that was enough. It brought back a particular moment to me as vividly as if it had happened an hour earlier. This was a moment with my late father, the writer Maurice Zolotow, who has been dead now almost twenty years.

But, when I heard that unseen animal, he was alive to me again. "No one ever steps in the same river twice," wrote the Greek philosopher

Heraclitus, "for it is not the same river and one is not the same

person. " I feel that way, too, about memory's river, into which I necessarily step when I think about Maurice.

Another river, the King's, in Northwest Arkansas, is involved in the

moment I recalled.

As is a great blue heron.

(The one pictured left is not "ours" , which I'm about to tell you about, but one

photographed by Sheila L. Chambers for Birdwatcher's

Digest).

As is the inadvertent transmission of wisdom, with which sometimes, if we are fortunate, our parents gift us, almost incidentally.

I've written about Maurice here often, most notably in this post. So I''ll give only a brief back-story. For it was a long way from the circumstances of his birth and later life to the King's River.

Born Morris Zolotoff on November 23, 1913, in Brooklyn, New York, he was a first-generation American who was the son of Russian-Jewish immigrants. Like many of similar background, his idea of sophisticated, upper class America was informed by the movies, and it was towards this world he gravitated, eventually writing magazine articles (for Billboard, Saturday Evening Post, Collier's, Look, Life, and, later, Playboy, Reader's Digest, and Los Angeles) and books, mostly about entertainment figures, musical, theatrical, and cinematic.

Sometime between his graduation from New Utrect High School and his entry into the University of Wisconsin at Madison, Morris became Maurice.

He could (and did) legitimately drop names and anecdotes across an astonishing spectrum: Duke Ellington ("The only place we could eat in together in New York  was a Chinese restaurant," he told me many times. But no matter how many times he said it, it was never without a tightening of his mouth, a slight shake of his head, and a tone of outrage. Racism of any type was incomprehensible to him. He recognized its reality, but, to him, it was so despicable it defied belief, let alone acceptance).

was a Chinese restaurant," he told me many times. But no matter how many times he said it, it was never without a tightening of his mouth, a slight shake of his head, and a tone of outrage. Racism of any type was incomprehensible to him. He recognized its reality, but, to him, it was so despicable it defied belief, let alone acceptance).

He gave Count Basie his first national review (in Billboard), and interviewed most of the sex goddesses of his time: Brigitte Bardot, Marilyn Monroe (about whom he would write many articles, and then the first of her countless book-length biographies), Ursula Andress (best known for her role as Honey Ryder, the Bond Girl in Dr. No), and Grace Kelly (she may have been a princess, but he wrote about her --- making her his subject!).

The now all-but-forgotten outrageous show-business personality/actress Tallulah Bankhead remained memorable to him: during an interview he did in her apartment, she got up to use the bathroom, and continued talking, leaving the door open, as she urinated. She also had a parrot, which she allowed to fly uncaged, It swooped around her living-room room, to my father's great unease, its droppings cleaned up by a maid who stood on guard. Comedians? He interviewed  dozens: Jack Benny, Jerry Lewis, Woody Allen, Dudley Moore, Fred Allen, Allan Sherman, countless others.

dozens: Jack Benny, Jerry Lewis, Woody Allen, Dudley Moore, Fred Allen, Allan Sherman, countless others.

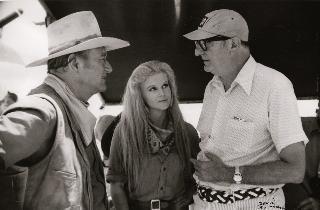

For a change of pace (and probably because he needed the money) he even took on John Wayne. In the picture above right, there's the Duke, with Ann-Margret and my father. This was taken on the set of The Train Robbers, released in 1973, a year before my father's biography of Wayne, Shooting Star, was published).

As I said in the previous post I did about him, at the time of his death he was working on a memoir to be called "Famous People Who Have Known Me." Which about says it all.

Except it doesn't. Not even close.

"I contain multitudes," Walt Whitman may have exulted in Song of Myself, and I think most of us do. But few collections of multitudes can have been so wholly contradictory as those contained by Maurice. I'll touch on just one here: side by side with his enchantment with celebrity, talent, glitz, and being where the action was, was his abiding love of nature and the solacing quietude that comes with immersion in it.

Where did this come from in him? How did it get there? I don't know: I only know that it was always part of him intermittently. And in the last twenty years of his life, it became one of his transcendent, transforming refuges.

Once, sitting on my porch in Arkansas, he saw a black-and-blue mourning cloak  butterfly lit on a snapdragon. Maurice leaned towards it, then stayed perfectly still. The butterfly, likewise, remained on the flower for a long time, its only movement the two wings, fanning like breath.

butterfly lit on a snapdragon. Maurice leaned towards it, then stayed perfectly still. The butterfly, likewise, remained on the flower for a long time, its only movement the two wings, fanning like breath.

I had come out the door, and I too stood still, watching not only the butterfly, but watching my father watch the butterfly. When it flew away, he turned and looked up at me. Normally ebullient and wildly talkative, he was wholly quiet. His usually animated face was both illuminated and still, silenced by wonder, even awe, and peace. He looked as if he had seen the face of God and creation itself, and was still stunned by it.

Whatever he found in that butterfly had been with him for awhile. He attended the University of Wisconsin at Madison, where he met my mother, the former Charlotte Shapiro, in a class on French Romantic poetry. And one of the ways he courted her was by taking her canoeing on Lake Mendota. Where and how did a wholly nonathletic, overly intellectual, skinny, neurotic, glasses-wearing Brooklyn boy get that?

Later, after they married, Maurice and Charlotte rambled England's Lake District, as famous for its  natural beauty as its poets.

natural beauty as its poets.

Still later, as a couple with children, they resided uneasily in the suburbs of New York City, Westchester County. My mother would have preferred "real country", my father, Greenwich Village or the Left Bank. Westchester, a compromise, left them both unhappy and resentful. Yet even there, Maurice, Charlotte and I (I don't remember my 7-years-older brother ever coming along) occasionally went on long walks together, often around the less-developed parts of Tibbett's Brook Park.

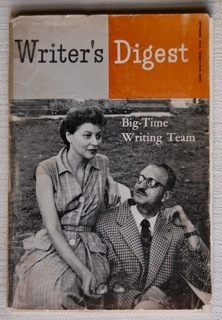

By then, they were both famous, my mother as a children's book author and editor, my father as a biographer. The Zolotows were, as the above cover, from the September, 1951 Writer's Digest says, a "Big-Time Writing Team. " They were also, increasingly, big-time unhappy. My father's drinking, my mother's martyrdom, and the generally anxious, repressed, and sexist tenor of the times, captured accurately in the television series Mad Men: all these played a part. I've written, too, about both their casual, medically and socially sanctioned drug-taking in this post. They divorced in 1969 (I was sixteen.) A year later, my father moved to Los Angeles. A year after that, he joined Alcoholics Anonymous.

And it was in those last twenty sober years of his life that his love of the natural world took its deepest root in him. He became a member of both the Sierra Club

and the Audubon Society and went on Sunday hikes sponsored by both

organizations, often. (Left, a picture of Solstice Canyon, one I believe he hiked, from the Los Angeles Sierra Club's site). "Isn't it amazing, Cres?" he would ask me rhetorically, bursting with his customary enthusiasm, when I came to visit him in LA. "Here we are, in the middle of a city, but you can smell the night-blooming jasmine and orange blossoms, and do you know, in just 20 minutes --- 20 minutes! --- I can be out on a hike or a bird walk in a canyon!"

It was in this phase, too, that he had that encounter with the mourning cloak butterfly on my porch. He came to visit me at least once a year in Arkansas.

And sometimes we floated the King's River. "Oh, yes," said my father confidently before we put in the first time. "Of course I know how to canoe. I used to take your mother canoeing on Lake Mendota, you know." But that was a lake, 40-some years earlier, and this was a river; albeit a gentle one, there were little rills of white water. My father wasn't kidding anyone. He was scared, but he was psyched. He was up for it.

My friend George West, who organized the whole thing, always remembers that my father showed up wearing a safari jacket. George still says, fondly, "Here it was, the King's, to me a very placid little creek, not at all challenging. I looked at Maurice and it was clear that to him it was like, The African Queen. And I realized, anything could be, with that level of enthusiasm and adventure. Walking to the mailbox could be The African Queen. And that was what Maurice gave me. "

The first float we took together --- that time 'we' being me, George West, my late husband, Ned, and my friend Suzanne, then Suzanne Euler, now Suzanne Tucker, and Maurice --- he was still youngish, maybe 63 or 64. He still had some pretty good  vision, was in decent shape, and, with George's help --- George being the most experienced canoeist present --- Maurice could participate fairly fully. (Left: a family portrait of my friends, the dear Mitchell-West clan, left to right: George West, Starr Mitchell, Logan and Cane West, their sons, to whom I am a Cres-Aunt).

vision, was in decent shape, and, with George's help --- George being the most experienced canoeist present --- Maurice could participate fairly fully. (Left: a family portrait of my friends, the dear Mitchell-West clan, left to right: George West, Starr Mitchell, Logan and Cane West, their sons, to whom I am a Cres-Aunt).

But there were a few Mr. Magoo moments that day on the river: George calling out, "Watch out for that branch, Maurice!", Maurice whispering to me (I was in the bow, he in the stern that trip) sotto vocce, "Cres? Do you see a branch?" two seconds before starting to get lightly smacked in the face by the branch, and then, belatedly, ducking. (Of course everyone present could hear his covert whispers to me.)

These days I live in Vermont, not Arkansas. Ned, my husband, has been dead for almost ten years; Maurice, almost twenty. My present, and for-the-duration partner, David, is older than Maurice would have been on that first float. And I take a lot of walks.

Rarely is there a day, at this time in my life, when a walk in the green cathedral of the woods does not, at least for a moment, lift me out of myself. Most often it's the light: the way it comes through the trees, dappling the leaf- or pine-needle covered path or sending an almost Biblical ray down to illuminate a single leaf or, as I wrote about here, the ears of a deer. Since the land I walk is honeycombed with water, springs and seeps and little creeks and marshy areas, sometimes it's water, or light on water, or the sound of water, or a combination of all three.

But often it's wildlife: bird, insect, reptile, mammal. Wild, life: both the wildness --- untamed, unpredictable --- and the life . A tiny burnt-orangey-red salamander (an eft, they're called) on the path, can thrill me, as can a bumblebee, droning drowsily as it moves from wild rose to foam flower in the deep woods, if I stand still and just watch it for awhile.

And the other day a plump brownish gray and white chickenish-shaped game

bird ran across the old gravel road, the part hardly anyone travels, right in front of me.

It was making first a

soft, melodious clucking, which later, as it rustled in the brush &

ferns, turned into an almost purring sound. When I came home, I spent a little time trying to ID it on the Internet (as if that would or could have made it

more wondrous). I think it was a Spruce Grouse. (Picture, right, from

audobon.com, taken by a Glenn Tepke.)

But it was its sound, especially that strange almost-purr that spoke most to me, even more than its shape, beauty, and, for me, rarity.

For sound, like light, water, and greenness, often brings that lifting-out-of-one's-own-small-world, too. The woods and meadows are loud with birds this time of year, in contrast to the near-complete stillness of winter in Vermont.

Which brings me back to the rustle I heard in the woods the other day, and to my father, and to the King's River --- the final float we took together. By then my father's eyesight was very poor, but he still wanted to go.

What did I learn from my father? In that earlier post, I mentioned much of what I imbibed from him about writing and being a writer. But of course, there was - is - more.

Enthusiasm. Joie de vivre. Digging under the surface to find the deeper intricacies of the story, of almost anything and anyone. Reading. Quoting the greats, always with attribution (it is his influence that has brought both Heraclitus and Walt Whitman into this post, for instance.)

Most of all, I think Maurice gave me a sense that a continual falling in love with the world was possible and desirable, despite its --- and one's own --- losses, sorrows, and limitations.

On that final float, we rounded a bend, and George (with Ned in the canoe ahead of Maurice and me). said suddenly, softly, urgently, pointing with his paddle, "Blue heron! One-o'clock!"

My father, the bird-lover, with equal urgency: "Where, where?"

Me (softly, pointing a few feet to the right): "Just there, Maurice."

He turned his head in the direction I was pointing, and said, in a voice wretched with disappointment, "I can't see it."

Just then the great blue heron took off from the stream in which it had been standing. They are big birds, with a wing-span that ranges between 5 1/2 and 6 1/2 feet. And this one flew right over our heads. Right, directly over the canoe in which Maurice and I sat.

Those huge wings beat the air, bearing the heron up and over us. Slowly. Audibly. A pause between each wingbeat.

Beat.

Beat.

Beat.

My father tipped his chin up. And he said, in a voice that was overwhelmed with a joy, gratitude, and a deep satisfaction even larger than his sorrow of a few seconds before, "I can hear it, though."

(Picture above, again not "our" heron, but by Jules Frederick. I am so grateful to have found this image!)

May 31, 2010

the deer's ears: Mose, me, misery & moments

Today, coming down to the hill towards the pond, beginning my morning walk, two animals --- one large, one small --- standing in the middle of the gravel road. I caught my breath, stood stock-still, blinked and waited, blinking a few times to clear my not-so-good vision so I could identify them.

Ah. A white-tailed deer, and - what was that smaller creature? If a faun, the tiniest one I had ever seen, and low to the ground, and dark. No, surely no, not a faun.I waited on my eyes and brain...

Ah. A cat. A small, peripatetic black cat named Bootsie, belonging to my neighbor Andrew, who lives about a quarter-mile away (across from the graveyard I  wrote about last time). Bootsie often wanders over here to play with my two cats --- at least, they play when they are all outside, but hissing and yowling begins if mine are on one side of the screen and Bootsie on the other. (David's portrait of Bootsie, looking spooky, which he's not, and half-wild, which he is, taken the April afternoon David visited the graveyard with me to take pictures.)

wrote about last time). Bootsie often wanders over here to play with my two cats --- at least, they play when they are all outside, but hissing and yowling begins if mine are on one side of the screen and Bootsie on the other. (David's portrait of Bootsie, looking spooky, which he's not, and half-wild, which he is, taken the April afternoon David visited the graveyard with me to take pictures.)

The deer (I had a side view, and I believe it was a him, a buck, though too young to have antlers) was facing the right, where the large meadow begins. Only his white tail moved, flickering upright occasionally. Bootsie, with all the delusions of grandeur that only a fearless young half-wild black cat can have, was crouched, in a stalking position. Both, at the sound of my feet, as still (except for that white tail) as the figures on Ode on a Grecian Urn.

Then I began to walk, slowly, towards them. The buck took off for the meadow, Bootsie in pursuit.

That glimpse would have been enough to transform that walk for me, to take my brooding heart from itself back to its true home: wonder. The life-work of seeing and loving the world and what's in it as it is, without being caught on the briers of fear, self-doubt, self- or other-hate, anxiety, all the thousand small things that remove us from the vastness. Yet knowing when and how to move in action, however one can from as it is to as it might be. Or should be. Yet to stay loving, seeing, eyes --- however imperfect one's vision --- open.

But when I got down to the break in the trees edging the meadow through which the two had disappeared, there stood the young buck, facing me, perhaps a hundred feet away. (No sign of Bootsie; the grass is tall).

All I could see was the buck's head, held nobly erect.

And here is the surpassing wonder of that moment: with morning sun behind him, the two thin-skinned upright elongated triangles of his ears were illuminated - a bright translucent deep red, each outlined by a two-sided triangular rim of brown fur.

As brilliant, and to me, more uplifting, than the rose windows at Notre-Dame de Paris.

I had never seen deer's ears like this before; I will almost certainly never see them again.

At that moment, the troubles I had begun the walk with dropped. "Such a perfect moment," as Mose Allison, sometimes called "the William Faulkner of jazz," sings, "Nothing you can say / One such perfect moment / Gets you through the day."

David, the resident photographer, is not here now, but in Los Angeles. He'll be there about a month, getting ready to sell a home he owns there. But even if he were here, he rarely goes on walks in the morning, so the only real way for you to picture it is through my description. Maybe that's enough.

(My friend Traca Savadago, the Seattle-based food maven and blogger said, generously, in a post about our friendship, "I photograph everything. Crescent photographs nothing. As a skilled

observer, I'm convinced she "sees" more. I lean on the image; she

expresses it through words.")

However, as I walked on down the hill, and then up, and then to the right, up and up through the woods above the pond, into and through more woods where Frazier has his sugaring operation, along one of the paths he keeps clear for access to his

sugaring lines, I remembered a picture David had taken on another walk. Not of a deer, not of a wild creature at all, but of a domesticated turkey, albeit a 'heritage' variety (you can tell because it's not pure white, and its breast is not so gargantuan that it is falling over).

But the sun was behind that turkey, too, and lit up its red wattle as if it was a blessed and sacred thing, as the deer's ears appeared to me.

As perhaps anything in the world is or would be, if we looked sufficiently closely, with sufficient illumination.Or, perhaps, if we had sufficient distance, to see the whole picture; a God's-eye view.

But who among us has that?

Deer were a problem in Eureka Springs, that sweet and vitriolic, contentious, lovely little Ozark Mountain town in Arkansas where I used to live. No one could agree about what should be done about them.

The deer there had no natural predators left, and had gotten complacent about the human inhabitants. They bred and bred and bred, and they lived close-up with the people. On the one hand, I could watch a doe nuzzle her two darling dappled fauns just a few feet from my kitchen window. Sometimes they stood; sometimes they knelt, napping. No one could have watched them and not said "Awwwww."

Yet no one in town had had a tulip bloom in years (the deer adored tulip bulbs); and, indeed, it was reaching the point where no one had much of a garden, vegetable or flower, at all, other than one composed of those plants the nurseries labeled "deer-proof." You had to be careful driving certain stretches of road, those in town but bordered by woods or brush-covered patches, because you were liable to hit a deer.

Certainly you would see the deer, even if you didn't hit them, all the time back in Eureka Springs; you could not avoid them. I still remember fondly a remark made by my first post-Ned boyfriend. We were driving into Dairy Hollow the back way one early evening in late summer; it was still a little light. It must've been a weekend, because he lived in Little Rock and would come up, driving his large loaded brand-new pick-up (he bought a new one every year, an affectation since he had grown up in Westchester, gone to Groton and then Duke, and was, in his business, billing $12K a month. But he lived in Arkansas now, and thiought he should have a pick-up).

A herd of deer, maybe 30 or 40 of them, on either side of the road, were calmly decimating the flora.

He pushed down the window-button, leaned out, and yelled at the deer, "Get a job!"

"The deer problem" was one of the countless things in Eureka people got exercised over (I used to think it was because we cared, because we weren't apathetic. Now I think maybe that that community just has some kind of magnetic pull to people who enjoy arguing, litigating, and busybodying. Probably there's something to both theories).

Shooting inside the city limits was illegal, besides which many opposed hunting on principle, although just as many engaged in it. Having someone from Game and Fish come and shoot the deer with birth control pellets was even discussed, though perhaps that was just a joke someone made, or one of the wild rumors that boomeranged around that place with such force that they took on the patina of truth.

Meanwhile, the deer multiplied, and went hungry.

Whether the town ever solved the this, I do not know; I moved away in 2002.

Here, though, on 35 acres in Vermont, it's rare to see a deer. Coyotes and weasels, natural predators, abound. That's what balance looks like. Things eat each other. That's what life looks like. If you're born (or "take a birth" as I heard said in India) , you eat and, eventually, will be eaten. Basic contract of inhabiting a body.

I stood and watched that deer with its ears like a sign from God, and it watched me, for perhaps 30 seconds, neither of us moving.

Then it stamped one hoof, took a half-step towards me and then turned, gave that strange loud snort they do and bounded away. Those huge leaping effortless bounds! I could see only the top of the deer, its white tail and reddish brown back, at the top of each bound. Then, it was out of sight. I heard one more snort, fainter, as vanished as if the whole episode had never taken place.

I continued my walk through the ferny, now starting-to-be-buggy, woods. There were  more shades of green than I have names for troubles. Yet I still walked weighted: there are no good alternatives for my 95-year-old mother. Every option has drawbacks. I don't have answers, let alone good ones, on to how to make her last years on earth as good as they can be. Every time I think it is figured out, things shift. Hundreds of hours have gone into finding a solution. My brother and I try hard, and come in and out of harmony with each other.

more shades of green than I have names for troubles. Yet I still walked weighted: there are no good alternatives for my 95-year-old mother. Every option has drawbacks. I don't have answers, let alone good ones, on to how to make her last years on earth as good as they can be. Every time I think it is figured out, things shift. Hundreds of hours have gone into finding a solution. My brother and I try hard, and come in and out of harmony with each other.

But I kept remembering the deer's ears.

When I came home I looked up the lyric's of that Mose Allison song, Perfect Moment. And then, because both sorrow and the illuminated ears of a wild creature are both themselves, and, to a writer, material, I came home and wrote this. Nothing is wasted on the writer. Like Mose, whose words follow, I am still in the game:

Mountain sheen, ocean shine

Miocene valentine

One such perfect moment

Never twice the same

Such a perfect moment

Will keep you in the game.

Crescent Dragonwagon's Blog

- Crescent Dragonwagon's profile

- 69 followers