Simon Ings's Blog, page 25

March 1, 2020

Over-performing human

Nearly two years in the making, Overflow is a political piece by any measure — a survey of our spiritual condition under surveillance capitalism, and our relationship to the machines that increasingly govern our lives…

Talking to choreographer Alexander Whitley for the Financial Times, 28 February 2020

February 16, 2020

Nicholas, c’est moi

Watching Color Out of Space for New Scientist, 12 February 2020

Nicholas Cage’s efforts to clear his debts after 2012’s catastrophic run-in with the IRS continue with yet another relatively low-budget movie, Color Out of Space, a film no-one expects much of. (It’s in US cinemas now; by the time it reaches UK screens, on 28 February, it will already be available on Blu-Ray.)

Have you ever watched a bad film and found yourself dreaming about it months afterwards? Color Out of Space is one of those.

To begin: in March 1927 the author H. P Lovecraft wrote what would become his personal favourite story. In “The Color Out of Space”, a meteor crashes into a farmer’s field in the Massachusetts hills. The farmer’s crops grow huge, but prove inedible. His livestock go mad. So, in the end, does the farmer, haunted by a colour given off by a visiting presence in the land: a glow that belongs on no ordinary spectrum.

This is Lovecraft’s riff on a favourite theme of fin-de-siecle science fiction: the existence of new rays, and with them, new ways of seeing. The 1890s and 1900s were, after all, radiant years. Victor Schumann discovered ultraviolet radiation in 1893. Wilhelm Röntgen discovered X-rays in 1895. Henri Becquerel discovered radioactivity in 1896. J. J. Thomson discovered that cathode rays were streams of electrons in 1897. Prosper-René Blondlot discovered N-rays in 1903 — only they turned out not to exist: an artefact of observational error and wishful thinking.

And this is pretty much what the local media assume has happened when Nathan Gardner, the not-very-effective head of a household that is downsizing after unspecified health problems and financial setbacks, describes the malevolent light he catches spilling at odd moments from his well. The man’s a drunk, is what people assume. A fantasist. An eccentric.

The film is yet another attempt to fuse American Gothic to a contemporary setting. Director Richard Stanley (who brough us 1990’s Hardware, another valuable bad movie) has written a script that, far from smoothing out the discrepancies between modern and pre-modern proprieties, manners, and ways of speaking, leaves them jangling against each other in a way that makes you wonder What On Earth Is Going On.

And what is going on, most of the time, is Nicholas Cage as Gardner. Has anyone before or since conveyed so raucously and yet so well the misery, the frustration, the rage, the self-hatred of weak men? Every time he gets into a fist-fight with a car interior I think to myself, Ah, Nicholas, c’est moi.

Even better, Cage’s on-screen wife here is Joely Richardson, an actress who packs a lifetime’s disappointments into a request to pass the sugar.

Alien life is not like earth life and to confront it is to invite madness, is the general idea. But with tremendous support from on-screen children Madeleine Arthur and Brendan Meyer, Cage and Richardson turn what might have been a series of uninteresting personal descents into a family tragedy of Jacobean proportions. If ever hell were other people, then at its deepest point you would find the Gardner family, sniping at each other across the dinner table.

Color Out of Space mashes up psychological drama, horror, and alien invasion. It’s not a film you admire. It’s a film you get into internal arguments with, as you try and sort all the bits out. In short, it does exactly what it set out to do. It sticks.

An embarrassment, a blowhard, a triumph

Watching Star Trek: Picard for New Scientist, 24 January 2020

Star Trek first appeared on television on 8 September 1966. It has been fighting the gravitational pull of its own nostalgia ever since – or at least since the launch of the painfully careful spin-off Star Trek: The Next Generation 21 years later.

The Next Generation was the series that gave us shipboard counselling (a questionable idea), a crew that liked each other (a catastrophically mistaken idea) and Patrick Stewart as Jean-Luc Picard, who held the entire farrago together, pretty much single-handed, for seven seasons.

Now Picard is back, retired, written off, an embarrassment and a blowhard. And Star Trek: Picard is a triumph, praise be.

Something horrible has happened to the “synthetics” (read: robots) who, in the person of Lieutenant Commander Data (Brent Spiner, returning briefly here) once promised so much for the Federation. Science fiction’s relationship with its metal creations is famously fraught: well thought-through robot revolt provided the central premise for Battlestar Galactica and Westworld, while Dune, reinvented yet again later this year as a film by Blade Runner 2049‘s Denis Villeneuve, is set in a future that abandoned artificial intelligence following a cloudy but obviously dreadful conflict.

And there is a perfectly sound reason for this mayhem. After all, any machine flexible enough to do what a robot is expected to do is going to be flexible enough to down tools – or worse. What Picard‘s take on this perennial problem will be isn’t yet clear, but the consequences of all the Federation’s synthetics going haywire is painfully felt: it has all but abandoned its utopian remit. It is now just one more faction in a fast-moving, galaxy-wide power arena (echoes of the Trump presidency and its consequences are entirely intentional).

Can Picard, the last torchbearer of the old guard, bring the Federation back to virtue? One jolly well hopes so, and not too quickly, either. Picard is, whatever else we may say about it, a great deal of fun.

There are already some exciting novelties, though the one I found most intriguing may turn out to be a mere artefact of getting the show off the ground. Picard’s world – troubled by bad dreams quite as much as it is enabled by world-shrinking technology – is oddly surreal, discontinuous in ways that aren’t particularly confusing but do jar here and there.

Is the Star Trek franchise finally getting to grips with the psychological consequences of its mastery of time and space? Or did the producers simply shove as much plot as possible into the first episode to get the juggernaut rolling? The latter seems more likely, but I hold out hope.

The new show bears its burden of twaddle. The first episode features a po-faced analysis of Data’s essence. No, really. His essence. That’s a thing, now. How twaddle became an essential ingredient on The Next Generation – and now possibly Picard – is a mystery: the original Star Trek never felt the need to saddle itself with such single-use, go-nowhere nonsense. But by now, like a hold full of tribbles, the twaddle seems impossible to shake off (Star Trek: Discovery, I’m looking at you).

Oh, but why cavil? Stewart brings a new vulnerability and even a hint of bitterness to grit his seemlessly fluid recreation of Picard, and the story promises an exciting and fairly devastating twist to the show’s old political landscape. Picard, growing old disgracefully? Oh, please make it so!

February 1, 2020

“I heard the rustling of the dress for two whole hours”

By the end of the book I had come to understand why kindness and cruelty cannot vanquish each other, and why, irrespective of our various ideas about social progress, our sexual and gender politics will always teeter, endlessly and without remedy, between “Orwellian oppression and the Hobbesian jungle”…

Reading Strange Antics: A history of seduction by Clement Knox, 1 February 2020

“So that’s how the negroes of Georgia live!”

Du Bois was struck by the fact “that there are nearly half as many Negroes in the United States as Spaniards in Spain”, their illiteracy less than that of Russia. A chart called “Conjugal Condition” suggests that black Americans were more likely to be married than Germans…

“If we’re going to die, at least give us some tits”

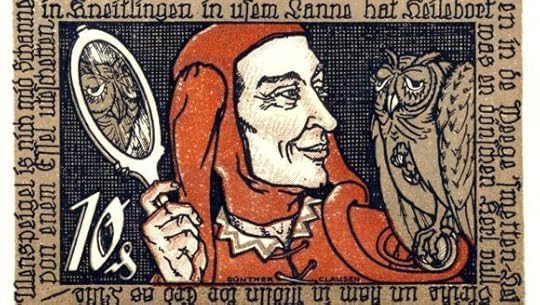

The Swedes are besieging the city of Brno. A bit of Googling reveals the year to be 1645. Armed with pick and shovel, the travelling entertainer Tyll Ulenspiegel is trying to undermine the Swedish redoubts when the shaft collapses, plunging him and his fellow miners into utter darkness. It’s difficult to establish even who is still alive and who is dead. “Say something about arses,” someone begs the darkness. “Say something about tits. If we’re going to die, at least give us some tits…”

Reading Daniel Kehlmann’s Tyll for the Times, 25 January 2020

January 26, 2020

Wolves: the US edition is out!

“Me, Washoe”

Watching Nick Lehane: Chimpanzee at Barbican Centre, London

for New Scientist, 20 January 2020

The puppet, a life-sized female chimpanzee, is made out of wood, rope, carved hard foam and paper mâché. She gazes out at the audience from a raised platform and, through movement alone, weaves her tale. When she was young, she lived as part of a human family. Now she is incarcerated in a research laboratory, deprived of company, her mind slowly deteriorating.

Rowan Magee, Andy Manjuck, and Emma Wiseman operate the chimpanzee, the sole actor in a puppet play running at the Barbican Centre in London. The play, Chimpanzee, by Brooklyn-based actor and puppeteer Nick Lehane, is a highlight of 2020’s London International Mime Festival. It is a moving story that is attracting attention from neurologists and cognitive scientists along with the usual performing-arts crowd.

Lehane conceived the show after reading Next of Kin, a memoir by psychologist and primate researcher Roger Fouts. Fouts’s tales of experiments in fostering young chimpanzees in human homes had obvious dramatic potential. Then, as Lehane looked deeper, he discovered a much darker story.

The Fouts family’s own chimps enjoyed a relatively comfortable life once they outgrew their human home. But other chimpanzees in similar programmes found themselves sold to research labs, living out almost inconceivably solitary lives of confinement and vivisection.

Modern efforts to communicate with chimpanzees began in 1967 at the University of Nevada, Reno, when primatologists Allen and Beatrix Gardner set up a project to teach American Sign Language (ASL) to a chimp called Washoe. These experiments have so transformed our view of chimp culture that many of the original researchers are campaigning to end the practice of keeping primates in captivity. (It is still legal to keep primates as pets in the UK.)

Chimpanzee vocalisations aren’t under conscious control, but the apes can communicate using body gestures. “This happens naturally in the wild,” says Mary Lee Jensvold, who advised Nick Lehane on his play. A former student of Roger Fouts, she too campaigns to end primate captivity. “And because chimps live in communities that are relatively closed and quite aggressive with each other, each community has its own repertoire of gestures. Where there’s some overlap, there are differences in how the gestures are articulated.”

In other words, each community speaks in its own accent, and this, says Jensvold, “really speaks to chimpanzees being cultural beings“.

As the sign-language studies grew more ambitious, the Gardners and their colleagues Roger and Deborah Fouts took the chimps into their own homes, acculturating them as humans as far they could to encourage communication.

The obvious question – what is it like growing up in a family that contains chimpanzees? – is the only question Roger Fouts’s son Joshua struggles to answer: “The reality is it’s all I knew.” Joshua, now a media scholar, was raised in a family whose rituals involved members that weren’t human, whose human members would sign to each other so the chimpanzees wouldn’t feel left out of the conversation, and the experience has left him with a profound sense that every non-human has inherent sapience. “When I’m walking down the sidewalk, and I see a human walking with their dog,” he says, “I tend to greet the dog.”

Roger Fouts and his colleagues found that their animals used ASL to communicate with each other, creating phrases by combining signs to denote novel objects.

Washoe was the first chimpanzee to wield ASL in a convincing fashion. Others followed: when Washoe’s mate Moja didn’t know the word for “thermos”, he referred to it as a “metal cup drink”. When Washoe was shown an image of herself in the mirror, and asked what she was seeing, she replied: “Me, Washoe.”

The researchers could hardly credit what they were seeing – and some of their peers still don’t. Jensvold believes there may be a cultural conflict at work. “In the US, comparative psychology has historically been a very lab-based science, where you set up these contrived experiments in order to answer your research questions,” she says. “Out of Europe comes an ethological approach, which is really more about taking the time to observe.”

The sign language research has drawn Jensvold and her colleagues into animal welfare and protection. “We can’t keep doing to them what we’ve been doing,” she says.

Joshua recalls the moment his father reached the same conclusion: “About midway through his career, Roger realised that this was an experiment that should never have been done. Out of the desire to determine what it is about humans that makes us special, we’ve effectively condemned these chimpanzees to a life of incarceration. They’re enculturated to our behaviours. They can never be reintroduced to the wild.”

There are no captive chimps in New York, so Nick Lehane’s research for his play consisted almost entirely of watching videos. According to Jensvold, he couldn’t have picked a better form of study. “With video tape,” she says, “you can take close observation down to a minute level.”

By the time Jensvold got involved in Lehane’s project, there was already a performance ready for her to judge. For Lehane, that was a heart-in-mouth moment: “I was afraid that despite our best efforts, we had missed the mark. If anyone was going to think that we had missed something vital about chimp movement or behaviour, it would be Mary Lee.”

He needn’t have worried. “Chimpanzee was phenomenal,” says Jensvold. “I was spotting things that I knew other people in the audience, people who weren’t experts, weren’t going to notice. He captured these incredible nuances.” She pauses: “So the level of suffering that he’s depicting: he gets that right, too.”

How does Lehane’s chimpanzee convey emotion, given that chimp and human expressions don’t overlap at all precisely?

“A lot of it is in the miming of breath patterns,” says Lehane. “Short little pants and hoots look happy; deep intense heaves and cough will register as a different emotion.”

“One of the things I think is so cool about puppetry is that the audience fills in so many blanks,” he says. “I can’t tell you the number of times that someone has said, ‘How did you make the puppet cry?’ ‘How did you make the puppet frown?’ ‘I loved it when the puppet blinked!’ It tickles me because I just didn’t do any of those things.”

Is there a danger here that the audience is merely anthropomorphising his subject, interpreting his chimpanzee as little more than a funny-shaped human?

In answer, Lehane quotes primatologist Frans de Waal: “To endow animals with human emotions has long been a scientific taboo. But if we do not, we risk missing something fundamental, about both animals and us.”

Cutting up the sky

Reading A Scheme of Heaven: Astrology and the Birth of Science by Alexander Boxer

for the Spectator, 18 January 2020

Look up at sky on a clear night. This is not an astrological game. (Indeed, the experiment’s more impressive if you don’t know one zodiacal pattern from another, and rely solely on your wits.) In a matter of seconds, you will find patterns among the stars.

We can pretty much apprehend up to five objects (pennies, points of light, what-have-you) at a single glance. Totting up more than five objects, however, takes work. It means looking for groups, lines, patterns, symmetries, boundaries.

The ancients cut up the sky into figures, all those aeons ago, for the same reason we each cut up the sky within moments of gazing at it: because if we didn’t, we wouldn’t be able to comprehend the sky at all.

Our pattern-finding ability can get out of hand. During his Nobel lecture in 1973 the zoologist Konrad Lorenz recalled how he once :”… mistook a mill for a sternwheel steamer. A vessel was anchored on the banks of the Danube near Budapest. It had a little smoking funnel and at its stern an enormous slowly-turning paddle-wheel.”

Some false patterns persist. Some even flourish. And the brighter and more intellectually ambitious you are, the likelier you are to be suckered. John Dee, Queen Elizabeth’s court philosopher, owned the country’s largest library (it dwarfed any you would find at Oxford or Cambridge). His attempt to tie up all that knowledge in a single divine system drove him into the arms of angels — or at any rate, into the arms of the “scrier” Edward Kelley, whose prodigious output of symbolic tables of course could be read in such a way as to reveal fragments of esoteric wisdom.

This, I suspect, is what most of us think about astrology: that it was a fanciful misconception about the world that flourished in times of widespread superstition and ignorance, and did not, could not, survive advances in mathematics and science.

Alexander Boxer is out to show how wrong that picture is, and A Scheme of Heaven will make you fall in love with astrology, even as it extinguishes any niggling suspicion that it might actually work.

Boxer, a physicist and historian, kindles our admiration for the earliest astronomers. My favourite among his many jaw-dropping stories is the discovery of the precession of the equinoxes. This is the process by which the sun, each mid-spring and mid-autumn, rises at a fractionally different spot in the sky each year. It takes 26,000 years to make a full revolution of the zodiac — a tiny motion first detected by Hipparchus around 130 BC. And of course Hipparchus, to make this observation at all, “had to rely on the accuracy of stargazers who would have seemed ancient even to him.”

In short, a had a library card. And we know that such libraries existed because the “astronomical diaries” from the Assyrian library at Nineveh stretch from 652BC to 61BC, representing possibly the longest continuous research program ever undertaken in human history.

Which makes astrology not too shoddy, in my humble estimation. Boxer goes much further, dubbing it “the ancient world’s most ambitious applied mathematics problem.”

For as long as lives depend on the growth cycles of plants, the stars will, in a very general sense, dictate the destiny of our species. How far can we push this idea before it tips into absurdity? The answer is not immediately obvious, since pretty much any scheme we dream up will fit some conjunction or arrangement of the skies.

As civilisations become richer and more various, the number and variety of historical events increases, as does the chance that some event will coincide with some planetary conjunction. Around the year 1400, the French Catholic cardinal Pierre D’Ailly concluded his astrological history of the world with a warning that the Antichrist could be expected to arrive in the year 1789, which of course turned out to be the year of the French revolution.

But with every spooky correlation comes an even larger horde of absurdities and fatuities. Today, using a machine-learning algorithm, Boxer shows that “it’s possible to devise a model that perfectlly mimics Bitcoin’s price history and that takes, as its input data, nothing more than the zodiac signs of the planets on any given day.”

The Polish science fiction writer Stanislaw Lem explored this territory in his novel The Chain of Chance: “We now live in such a dense world of random chance,” he wrote in 1975, “in a molecular and chaotic gas whose ‘improbabilities’ are amazing only to the individual human atoms.” And this, I suppose, is why astrology eventually abandoned the business of describing whole cultures and nations (a task now handed over to economics, another largely ineffectual big-number narrative) and now, in its twilight, serves merely to gull individuals.

Astrology, to work at all, must assume that human affairs are predestined. It cannot, in the long run, survive the notion of free will. Christianity did for astrology, not because it defeated a superstition, but because it rendered moot astrology’s iron bonds of logic.

“Today,” writes Boxer, “there’s no need to root and rummage for incidental correlations. Modern machine-learning algorithms are correlation monsters. They can make pretty much any signal correlate with any other.”

We are bewitched by big data, and imagine it is something new. We are ever-indulgent towards economists who cannot even spot a global crash. We credulously conform to every algorithmically justified norm. Are we as credulous, then, as those who once took astrological advice as seriously as a medical diagnosis? Oh, for sure.

At least our forebears could say they were having to feel their way in the dark. The statistical tools you need to sort real correlations from pretty patterns weren’t developed until the late nineteenth century. What’s our excuse?

“Those of us who are enthusiastic about the promise of numerical data to unlock the secrets of ourselves and our world,” Boxer writes, “would do well simply to acknowledge that others have come this way before.”

Can you use a bottle opener?

EXHIBITIONS about our relationship with the environment tend to be bombastic. Either they preach doom and destruction, or they reckon our children will soon be living lives of plenty on artificial atolls.

Animalesque at the Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art in Gateshead, UK, knows better than this. In an international selection of art, sculpture and film, curator Filipa Ramos points out how little we know about other species, and how much we might still learn. With this humility comes hope that we can reform our relations with Earth.

Research has a major role to play, but it can only go so far. One unassuming TV monitor is screening a video from Tupilakosaurus, a long-running project by Danish-Greenlandic artist Pia Arke. It is a telling but not unsympathetic satirical film, in which examinations of a fossil dinosaur throw up folk tales, mangled histories and surreal mountains of paperwork as researchers try to represent and classify the Arctic’s life and history.

Often, we find out about other species only as we are evicting and replacing them. This happened to the Malayan tiger, which now numbers just some 300 wild cats in the Malay Peninsula. 2 or 3 Tigers (2015) by Singaporean artist Ho Tzu Nyen is a 19-minute, two- screen video, made using CGI and some very dodgy operatic singing, about the were-tigers of Malayan folklore. As ancestors, companions, competitors, protectors, destroyers and gods, tigers were central to the indigenous culture. Western settlers couldn’t find any there, however, until one sprang out of the forest in 1835 and attacked a hapless surveyor’s theodolite.

Our most stable cross-species relationships are with domesticated animals, even if they are sometimes discomforting or guilt-ridden affairs. In French artist Pierre Huyghe’s Untitled (Human Mask) (2014), a macaque explores an abandoned restaurant in Fukushima, Japan, an area gutted by the 2011 tsunami. Identifying the species of our protagonist takes a while. You would be forgiven for thinking you were watching a girl, because the macaque is wearing a wig and an eerily beautiful mask (pictured above).

The uncanny collision of categories (girl and pet, puppet and creature) only becomes more dizzying when you discover that Huyghe recruited his “star” from a Tokyo restaurant where the macaque spent many apparently happy hours working as a waiter.

It is a film of great pathos, more moving and less disturbing than this bald description suggests. It speaks to our difficulty understanding other animals, steeped as we are in human concerns.

The difficulty is real, can research help us? Degreecoordinates, Shared traits of the Hominini (humans, bonobos and chimpanzees) (2015) attempts it. For this, UK artist Marcus Coates worked with primatologist Volker Sommer to list questions relevant to all three: do you resolve conflicts using sex? Can you use a bottle opener? Do you kiss? Are you preoccupied with hierarchy and status?

Human answers vary, but so do those gleaned from studying individual chimps and bonobos. The differences between individuals of each of the three species far exceed those across species. Animalesque celebrates what we share – and what we can learn.

Simon Ings's Blog

- Simon Ings's profile

- 147 followers