Simon Ings's Blog, page 28

September 11, 2019

In Berlin: arctic AI, archeology, and robotic charades

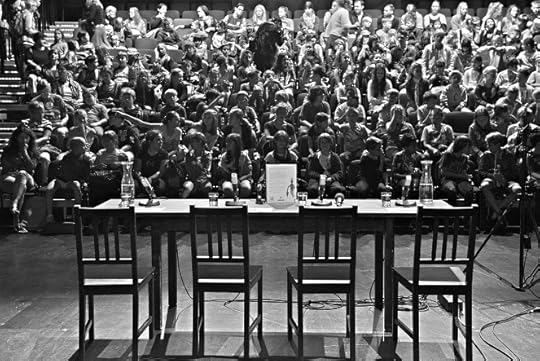

Thanks (I assume) to the those indefatigable Head of Zeus people, who are even now getting my anthology We Robots ready for publication, I’m invited to this year’s Berlin International Literature Festival, to take part in Automatic Writing 2.0, a special programme devoted to the literary impact of artifical intelligence.

Amidst other mischief, on Sunday 15 September at 12:30pm I’ll be reading from a new story, The Overcast.

September 5, 2019

Lost in the quiet immensities

Watching Aniara for New Scientist, 7 September 2019

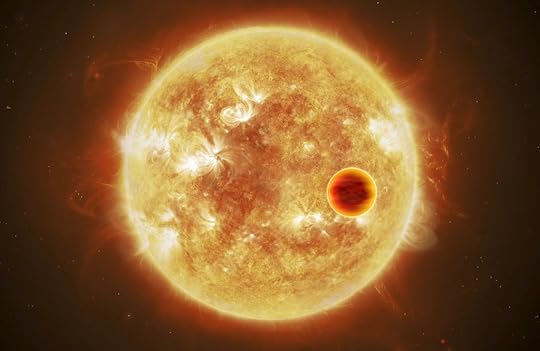

In the opening sequence of the Swedish sci-fi film Aniara, a space elevator rises into low earth orbit to meet an interplanetary cruiser, bound for new settlements on Mars. (The Earth, pillaged to destruction by humanity, is by now literally burning.)

But when we cut to its interior, the elevator turns out to be, well, a night bus. A tight focus on lead actress Emelie Jonsson, staring out a misted-up window into the featureless dark, accentuates, rather than conceals, the lack of set.

The interplanetary cruiser Aniara is a pretty decent piece of model work on the outside but on the inside, it’s a ferry. I know, because work for New Scientist once had me sailing down the coast of Norway on board the same vessel, or one very like it, for an entire week.

Have writer-directors Pella Kagerman and Hugo Lilja turned out a film so low-budget that they couldn’t afford any sets? Have they been inept enough to reveal the fact in the first reel?

No, and no. Aniara is, on the contrary, one of the smartest movies of 2019.

Aniara’s journey to Mars is primarily a retail opportunity. Go buy some duty-free knits while your kids knock each other off plastic dinosaurs in the soft-play area. Have your picture taken with some poor bugger on a minimum wage dressed as large, stupid-looking bird. Don’t worry: in a real crisis, there’s always the pitch-and-putt.

When the worst happens — colliding with a piece of space debris, the Aniara is nudged off course into interstellar space with no hope of return or rescue — the lights flicker, someone trips on some stairs, a couple of passengers complain about the lack of information, and the hospitality crew work the mall bearing complementary snacks.

“Transtellar Cruise Lines would like to apologize to passengers for the continuing delay to this flight. We are currently awaiting the loading of our complement of small lemon-soaked paper napkins for your comfort, refreshment and hygiene during the journey.”

Not Aniara, this, but a quotation from Douglas Adams’s peerless radio tie-in novel The Restaurant at the End of the Universe, to which Aniara serves as a particularly bleak twin. Don’t think for a moment this is a film without humour. There’s a scene in which the captain (played with pitch-perfect ghastliness by Arvin Kananian) reassures his castaway passengers that rescue is imminent while playing televised billiards. Balls and pockets; planets and gravity wells. It’s every useless planetary mechanics lecture you’ve ever suffered through and you realise, watching it, that everyone is doomed.

“They awoke screaming and clawing at their straps and life support systems that held them tightly in their seats.” (Adams again, because I couldn’t resist, and besides, it’s as good a summation as any of where Aniara is headed.)

Not only will there be no rescue. It begins to dawn on our heroine, Mimaroben (a sort of ship’s counsellor armed with a telepathic entertainment system that (you guessed it) kills itself) that there there is no such thing as rescue. “You think Mars is Paradise?” she scolds a passenger. “It’s cold.” May as well be here as there, is her conclusion. Death’s a waiting game, wherever you run.

Aniara is based on a long narrative poem by the Nobel laureate Harry Martinson, and the sci-fi writer Theodore Sturgeon, reviewing a 1964 American edition of the poem, said it “transcends panic and terror and even despair [and] leaves you in the quiet immensities”. So there.

But I don’t care how bleak it is. I am sick to the back teeth of those oh-so-futuristic science fiction films, and their conjuring-up of scenarios that, however “dystopic”, are really only there to ravish the eye and numb the mind.

Aniara gets the future right — which is to say, it portrays the future as though it were the present. When we finally build a space elevator, it’s going to be the equivalent of a bus. When we fly to Mars, it’ll be indistinguishable from a ferry. The moment we attain the future, it becomes now, and now is not a place you go in order to exprerience a frisson of wonder or horror. It’s where you’re stuck, trying — and sometimes failing — to scrape together a meaning for it all.

August 30, 2019

Transports of delight

Durham Cathedral’s stained glass windows inspired artist Dominic Wilcox’s contribution to Driverless, a tiny but thought-provoking exhibition at London’s Science Museum.

It occurred to Wilcox that artificial intelligence could make traffic collisions a thing of the past, which means “we don’t need the protection systems that are built into contemporary cars”, he told design magazine Dezeen. “We can just have a shell of any design.”

His Stained Glass Driverless Sleeper Car of the Future is the sort of vehicle we may be driving when road safety has improved to the point where we can build cars out of whatever we want. It suggests a future in which safety is no longer a set of barriers, cages, buffers and lights, and is instead a dance of algorithms. Rather than measuring out a bike lane, say, we will have an algorithm that decides whether to leave a smaller distance to the bicycle on its left to reduce the chance of hitting a truck on its right.

What if that causes more cyclists, but fewer passengers, to die every year? Such questions aren’t new. But they are having to be asked again and in a different and disconcerting form as we move more safety systems off the roads and into vehicles.

On show is the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s “Moral Machine”, a website using more than 40 million participants’ decisions on what to do in certain situations to inform our autonomous machinery design. The findings can be unsettling: would-be designers are more likely to sacrifice your safety if you are fat, a criminal or a dog

This is a show as much about possible futures as it is about the present. Interviews, archival footage, models and some interactive displays create a series of provocations, more than a fully fledged exhibition.

I especially liked the look of the MIT Senseable City Lab and the AMS Institute’s “Roboats”, currently on trial on Amsterdam’s canals. These autonomous floating platforms form spontaneous bridges and event platforms and can transport goods and people.

The exhibition spends much of its time off-road, investigating drone swarms and privacy, flocking behaviour and mine clearance, ocean mapping and planetary surveillance.

Don’t let its size put you off: this little show is full of big surprises.

August 7, 2019

Priority message

Exploring The Current War for New Scientist, 10 August 2019

Let’s begin by being boorish. Thomas Edison did not invent the light bulb. The German-born precision mechanic Heinrich Goebel demonstrated a practical prototype in 1854.

But of course you can play this game with pretty much any invention. The correct response to such nit-picking is given to Edison himself – inventor of the phonograph, inventor of motion pictures, holder of over 2000 patents – in a new movie, The Current War, which lays out, as surely as any circuit diagram, the battle between Thomas Edison and George Westinghouse to bring electric light to America at the end of the 19th century.

Salt. Fat. Flour. Water. Only when you put all the ingredients together, in the right proportions, using the right method, so people will spend their hard-earned pennies on the stuff, do you get bread. Priority – being the first to file a patent – is not won by dreaming alone. Edison, played by Benedict Cumberbatch, teaches this hard lesson to his personal secretary Samuel Insull, an entertainingly exasperated Tom Holland.

The film itself is the bloodied but unbowed victim of no end of industry trouble. It premiered at the Toronto Film Festival ahead of a scheduled release of November 2017 by the Weinstein Company. But as allegations about Harvey Weinstein gathered and grew in severity, the decision was made to quietly shelve the film for a while.

It doesn’t feel like an old movie, but it does feel like an odd one. Big, bold, none-too-subtle speeches by playwright Michael Mitnick are directed by Alfonso Gomez-Rejon as though they were set pieces by Martin Scorcese, for whom he once worked as a personal assistant.

Inventor George Westinghouse (played by Michael Shannon in a sensitive, understated performance which rather puts Cumberbatch’s familiar schtick to shame) has developed a system of electrification using alternating current. For cost and efficiency, this has Edison’s direct-current system beat. Westinghouse offers Edison a partnership, but Edison behaves like a cad, disparaging Westinghouse’s “lethal” technology and executing dogs, sheep and eleven horses with AC to prove his point. Irony piles on irony as Edison’s demonstrations lead him inevitably towards designing, much against his better ethical judgement, the first electric chair.

In the world outside the cinema, the “war of the currents” is not yet done. DC lost out to AC in the early days of electrification because efficient long-distance transmission required high voltages while the public needed safer, lower voltages. That required transformers, which existed for AC networks, but not for DC.

When it comes to transmitting large amounts of power over long distances, however, high-voltage direct current (HVDC) is way more efficient than conventional AC lines.

The length and capacity of new HVDC projects has risen fast, particularly in China, and calculations suggest that continent-wide HVDC “supergrids” could help smooth out the variable levels of power created by renewable sources.

In 2009 an influential study by Gregor Czish, of Kassel University in Germany, proposed a “super grid” to connect various European countries and bordering regions including North Africa, Kazakhstan, and Turkey, and at a total cost that virtually guarantees cheap green electricity for all.

No one’s heard of Czish, of course, though his insight may give the next generation cheap green energy and a chance to save civilisation from global warming.

It was ever thus: we only remember Nikola Tesla (The Current War’s peculiar third wheel, an AC pioneer and inventor of fluorescent light) because David Bowie played him in Christopher Nolan’s magical puzzler The Prestige.

Priority is a twisty business, and fame is twistier still. Westinghouse so despised the whole business he burned his papers, ensuring that his deeds alone would outlast him. “If you want to be remembered,” he says in the film, “it’s simple: shoot a president. But if you prefer to have what I call a legacy, you leave the world a better place than you found it.”

August 6, 2019

Something for the voyage

I’ve been editing a white paper for Pedro Russo and an international team about the European Space Agency’s strategies for public engagement and education. It’s part of ESA’s big consultation effort, called Voyage 2050.

You can find our paper on Zenodo at https://zenodo.org/record/3360374#.XUkydpMzbOQ

and on arXiv at http://arxiv.org/abs/1908.01546

August 5, 2019

Turning over new leaves

Contemplating Trees at Fondation Cartier, Paris for the Financial Times, 1 August 2019

Trees, a group show at the Fondation Cartier in Paris featuring artists, botanists and philosophers, screams personality — by which I mean eccentricity, thought and argument. Appropriately, it’s an exhibition that lives and breathes. I hated some of it and walked out of the gallery grinning from ear to ear. It absolutely does its job: it makes trees treeish again.

The French state’s funding for the arts is generous in quantity but conservative in taste. It doesn’t fund the Fondation Cartier, leaving it free to be playful — to hang so-called “outsider” and indigenous artists alongside established names; to work with artists in the long term, developing and acquiring pieces as collaborations grow. In other words, Paris’s first private foundation for contemporary art is free to behave as a private patron should and to learn on the job.

Trees is the latest in a line of exhibitions conceived by the Fondation Cartier that seek to decentre humans’ view of ourselves as overlords of creation. In 2016, The Great Animal Orchestra exhibition (which visits London in October) sought to establish common intellectual ground between species. Trees goes further, seeking a rapprochement between two kingdoms, the animals and the plants.

Trees are weirdly hard to see because they hide in plain sight. “The tree is the chair on which we sit, the table we use to write, it is our cupboards, our furniture, but also our most ordinary tools,” as Parisian philosopher Emanuele Coccia writes in the exhibition catalogue.

Tree-blindness is made worse by a western intellectual inheritance. When Aristotle asserted in his De plantis that vegetable life is insensate, he was going against Plato, Anaxagoras, Democritus and Empedocles. And he was wrong: plants detect and react to temperature, humidity, air pressure, vibration, sound, touch, trauma and chemical information that we have no short names for. They respond to these sensations as quickly as any animal. They are not less than animals, but they are radically, mind-bendingly different.

A life among trees does things to the eye. Perspective is not much help in reading a treescape, while pattern recognition is vital. Work here by Kalepi, Joseca and Ehuana Yaira, Yanomami artists from the Amazon rainforest, explores the architectonic quality of trees, expressing them as entire bodies rather than (as the western eye prefers) complex assortments of twigs and leaves. The Paraguayan artists of the Gran Chaco region included here, meanwhile, express their forest home more through typology than through aesthetics. Theirs is a forest as well-stocked and well-ordered as a supermarket. Count all the little animals and plants laid out in rows: this is not a wilderness but a tally of self-renewing plenty. The general lesson seems to be that a forest is an environment that’s easier to read for what it contains than to swallow in one gulp.

Drawings and diagrams by contemporary botanist Francis Hallé honour natural history, a European tradition in which aesthetic knowledge and scientific knowledge run parallel. Twentieth-century laboratory-based science finds its way on to Fabrice Hyber’s huge canvases — like wall-sized notebook pages annotated with multicoloured scribbles, graphs, colour wheels and wave forms. In each, Hyber reduces the trees to a single trunk, or a trunk and a branch: a world of abstractions and generalisations. Cesare Leonardi’s meticulous drawings reveal the architectural potential of trees — a potential mischievously misappropriated in Peruvian photographer Sebastian Mejía’s pictures of trees strained through fence wire, incorporated into walls or otherwise appropriated by the unliving city.

Some works here protest against the world’s breakneck deforestation. Thijs Biersteker, in collaboration with botanist Stefano Mancuso, offers a salve, wiring two trees in the Fondation’s extensive garden to scientific visualisations to help us empathise with what trees are sensing in real time. (This is more than a rhetorical flourish: the sense data that the piece collects are being corroborated and fed into scientific research, in a work that fulfils a dual artistic and scientific function.)

The lion’s share of the show is given over to Brazilian artist Luiz Zerbini, whose muted, simple monotypes and huge, complex, colourful canvases surround a table herbarium and a tree. The paintings are an Anthropocene jungle of sorts in which urban and natural forms hide in plain sight within a fiercely perpectiveless, rectilinear grid. Give your eyes time to adjust, and you find yourself in a city/forest of the future, where nature is exploited but not exhausted, and beauty and utility coexist.

These canvases suggest that we humans, having crafted our way out of the trees and developed those crafts on an industrial scale, can perhaps learn an even neater trick and make the whole human adventure last beyond this current, rapine moment

I came out of this show happy. I wasn’t just enthused. I’d been converted.

Attack of the Vocaloids

Marrying music and mathematics for The Spectator, 3 August 2019

In 1871, the polymath and computer pioneer Charles Babbage died at his home in Marylebone. The encyclopaedias have it that a urinary tract infection got him. In truth, his final hours were spent in an agony brought on by the performances of itinerant hurdy-gurdy players parked underneath his window.

I know how he felt. My flat, too, is drowning in something not quite like music. While my teenage daughter mixes beats using programs like GarageBand and Logic Pro, her younger brother is bopping through Helix Crush and My Singing Monsters — apps that treat composition itself as a kind of e-sport.

It was ever thus: or was once 18th-century Swiss watchmakers twigged that musical snuff-boxes might make them a few bob. And as each new mechanical innovation has emerged to ‘transform’ popular music, so the proponents of earlier technology have gnashed their teeth. This affords the rest of us a frisson of Schadenfreude.

‘We were musicians using computers,’ complained Pete Waterman, of the synthpop hit factory Stock Aitken Waterman in 2008, 20 years past his heyday. ‘Now it’s the whole story. It’s made people lazy. Technology has killed our industry.’ He was wrong, of course. Music and mechanics go together like beans on toast, the consequence of a closer-than-comfortable relation between music and mathematics. Today, a new, much more interesting kind of machine music is emerging to shape my children’s musical world, driven by non-linear algebra, statistics and generative adversarial networks — that slew of complex and specific mathematical tools we lump together under the modish (and inaccurate) label ‘artificial intelligence’.

Some now worry that artificially intelligent music-makers will take even more agency away from human players and listeners. I reckon they won’t, but I realise the burden of proof lies with me. Computers can already come up with pretty convincing melodies. Soon, argues venture capitalist Vinod Khosla, they will be analysing your brain, figuring out your harmonic likes and rhythmic dislikes, and composing songs made-to-measure. There are enough companies attempting to crack it; Popgun, Amper Music, Aiva, WaveAI, Amadeus Code, Humtap, HumOn, AI Music are all closing in on the composer-less composition.

The fear of tech taking over isn’t new. The Musicians’ Union tried to ban synths in the 1980s, anxious that string players would be put out of work. The big disruption came with the arrival of Kyoko Date. Released in 1996, she was the first seriously publicised attempt at a virtual pop idol. Humans still had to provide Date with her singing and speaking voice. But by 2004 Vocaloid software — developed by Kenmochi Hideki at the Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona — enabled users to synthesise ‘singing’ by typing in lyrics and a melody. In 2016 Hatsune Miku, a Vocaloid-powered 16-year-old artificial girl with long, turquoise twintails, went, via hologram, on her first North American tour. It was a sell-out. Returning to her native Japan, she modelled Givenchy dresses for Vogue.

What kind of music were these idoru performing? Nothing good. While every other component of the music industry was galloping ahead into a brave new virtualised future — and into the arms of games-industry tech — the music itself seemed stuck in the early 1980s which, significantly, was when music synthesizer builder Dave Smith had first come up with MIDI.

MIDI is a way to represent musical notes in a form a computer can understand. MIDI is the reason discrete notes that fit in a grid dominate our contemporary musical experience. That maddenning clockwork-regular beat that all new music obeys is a MIDI artefact: the software becomes unwieldy and glitch-prone if you dare vary the tempo of your project. MIDI is a prime example (and, for that reason, made much of by internet pioneer-turned-apostate Jaron Lanier) of how a computer can take a good idea and throw it back at you as a set of unbreakable commandments.

For all their advances, the powerful software engines wielded by the entertainment industry were, as recently as 2016, hardly more than mechanical players of musical dice games of the sort popular throughout western Europe in the 18th century.

The original games used dice randomly to generate music from precomposed elements. They came with wonderful titles, too — witness C.P.E. Bach’s A method for making six bars of double counterpoint at the octave without knowing the rules (1758). One 1792 game produced by Mozart’s publisher Nikolaus Simrock in Berlin (it may have been Mozart’s work, but we’re not sure) used dice rolls randomly to select beats, producing a potential 46 quadrillion waltzes.

All these games relied on that unassailable, but frequently disregarded truth, that all music is algorithmic. If music is recognisable as music, then it exhibits a small number of formal structures and aspects that appear in every culture — repetition, expansion, hierarchical nesting, the production of self-similar relations. It’s as Igor Stravinsky said: ‘Musical form is close to mathematics — not perhaps to mathematics itself, but certainly to something like mathematical thinking and relationship.’

As both a musician and a mathematician, Marcus du Sautoy, whose book The Creativity Code was published this year, stands to lose a lot if a new breed of ‘artificially intelligent’ machines live up to their name and start doing his mathematical and musical thinking for him. But the reality of artificial creativity, he has found, is rather more nuanced.

One project that especially engages du Sautoy’s interest is Continuator by François Pachet, a composer, computer scientist and, as of 2017, director of the Spotify Creator Technology Research Lab. Continuator is a musical instrument that learns and interactively plays with musicians in real time. Du Sautoy has seen the system in action: ‘One musician said, I recognise that world, that is my world, but the machine’s doing things that I’ve never done before and I never realised were part of my sound world until now.’

The ability of machine intelligences to reveal what we didn’t know we knew is one of the strangest and most exciting developments du Sautoy detects in AI. ‘I compare it to crouching in the corner of a room because that’s where the light is,’ he explains. ‘That’s where we are on our own. But the room we inhabit is huge, and AI might actually help to illuminate parts of it that haven’t been explored before.’

Du Sautoy dismisses the idea that this new kind of collaborative music will be ‘mechanical’. Behaving mechanically, he points out, isn’t the exclusive preserve of machines. ‘People start behaving like machines when they get stuck in particular ways of doing things. My hope is that the AI might actually stop us behaving like machines, by showing us new areas to explore.’

Du Sautoy is further encouraged by how those much-hyped ‘AIs’ actually work. And let’s be clear: they do not expand our horizons by thinking better than we do. Nor, in fact, do they think at all. They churn.

‘One of the troubles with machine-learning is that you need huge swaths of data,’ he explains. ‘Machine image recognition is hugely impressive, because there are a lot of images on the internet to learn from. The digital environment is full of cats; consequently, machines have got really good at spotting cats. So one thing which might protect great art is the paucity of data. Thanks to his interminable chorales, Bach provides a toe-hold for machine imitators. But there may simply not be enough Bartok or Brahms or Beethoven for them to learn on.’

There is, of course, the possibility that one day the machines will start learning from each other. Channelling Marshall McLuhan, the curator Hans Ulrich Obrist has argued that art is an early-warning system for the moment true machine consciousness arises (if it ever does arise).

Du Sautoy agrees. ‘I think it will be in the world of art, rather than in the world of technology, that we’ll see machines first express themselves in a way that is original and interesting,’ he says. ‘When a machine acquires an internal world, it’ll have something to say for itself. Then music is going to be a very important way for us to understand what’s going on in there.’

July 12, 2019

Art that hides in plain sight

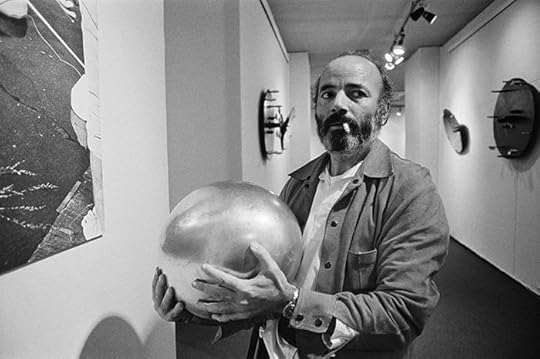

We’re presented with many wonders — objects rendered weightless, or put into permanent vibration, vaporous blue mercury and traffic signals turned into lonely, monstrous eyes. And as the show progresses (it’s surprisingly large, designed to unfold around corners and spring surprises at your back) the work gets less intuitive, and a lot louder. A pendulum, orbiting a strong, floor-mounted magnet, whips eccentrically and not at all gently about its centre of attraction. It’s like nothing in visible nature. There’s no “magnetic breeze” here, no “force like gravity”, just the thing, the weirdness itself. Now we’re getting somewhere.

Visiting Takis’s survey show at Tate Modern for the Spectator, 13 July 2019

The end of the line

IT IS 2011, a couple of years after the Great Recession. Quantitative analyst Vincent (Jesse Eisenberg) and his programmer cousin Anton (Alexander Skarsgård) have found a way to steal a march on Wall Street: trading a millisecond ahead of the competition.

Where will they find this tiny, telling pinch of extra time? They plan to make it themselves, by stretching an optical fibre from Kansas City Internet Exchange to New York in as straight a line as possible. While everyone else waits 17 milliseconds for their information (the beat of a hummingbird’s wing is the film’s poetic, and accurate enough, conceit), Vincent, Anton and their backers will only have to wait 16 milliseconds. That’s time enough to squeeze in a few thousand algorithmically generated trades.

The trick will be to lay the cable as straight as the law allows. Never mind Amish farms, Appalachian mountain ranges, loneliness, obsession or physical frailty. They will build this thousand-mile long, 4-inch wide fibre tunnel if it kills them.

Scripted and filmed like a true-life story (after all, who in their right mind would make up a thriller about high-frequency trading infrastructures?) The Hummingbird Project, incredibly, springs entirely from the head of writer-director Kim Nguyen. It can’t quite decide whether to be a think piece or a buddy movie, but it can be staggeringly funny. Salma Hayek has indecent amounts of fun as Eva, the cousins’ abandoned boss.“I think we can break the walls of perception together!” she screams at one point, in a frantic attempt to keep them on her payroll.

It is one of those stories that, in being made up, encapsulates a lot of historical and technical insight. Hayek’s Eva can talk “nanosecond financial engineering” all she wants. As a sceptical investor notes, her style of trading is really just scalping: profiting off small, short-lived price anomalies between financial exchanges.

Scalping is hard because one hefty loss wipes out millions of tiny profitable trades. And it is also impossible to do without computers because markets adjust quicker than the eye can follow.

When world markets crashed in 2008, this strategy took a lot of the heat. It was easier for politicians to point the finger at runaway tech and artificially accelerated trading than to challenge and dismantle key institutions. But while trading algorithms have caused the odd “flash crash”, they do far more to sustain a market economy than to threaten it. This is why so-called mechanical arbitrage runs over half the trades in many markets.

Vincent and Anton’s project is entirely reasonable in a world that puts commercial operations as close to market exchanges as possible to steal millisecond advantages over competitors. Hanging over the cousins’ project is a rival bid to leave fibre behind and send financial information by microwave (and the discussion of “pulse-shaping algorithms” will warm the heart of any telecoms engineer). Today, the industry is even more complex, with atomic clocks to arbitrate the timing of financial information. Financial instruments that scalp multiple markets are driving the creation of strategic data centres in unlikely places, as banks head for space via Elon Musk’s Starlink servers.

All of which gives the film a curiously nostalgic feel. Do you recall when it took a thousandth of a second to win or lose a fortune? What slowcoaches we were, eight years ago.

A clown, a fool, a “klimatosser”

I went round to Olafur’s house for New Scientist, 13 July 2019

SIXTEEN years ago, Danish-Icelandic artist Olafur Eliasson caught London off guard with a massive indoor artwork. Some 2 million people visited The Weather Project at the Tate Modern gallery to bask in the glow of a giant, artificial sun. It was a rare moment of collective awe – created using the simplest of materials. This week, Eliasson is back with a major retrospective exhibition and most of the pieces are new to the UK. But a lot has changed since 2003. Days before his new show opens, we asked the artist about selfie culture, what accessible art looks like in the teched-up Anthropocene, and the hefty carbon footprint that pictures and installations leave behind.

Do big art and big science have to justify themselves to people who don’t get the point?

Sadly, yes, and it’s an argument we’re losing because great science and great art are very much long-term projects, views given to politicians with short-term goals. Making a work might take 10 years. Getting it shown might take another 10. For people to finally settle down with the experience might take 10 years, too. It’s a very slow piece of communication.

You command big budgets. Is the relationship with money tricky for artists?

To make big projects is expensive. But think about how much money an alcohol company throws into the promotion of some new drink! I believe there are studies showing that if you throw a euro or a pound into the culture sector, it generates two to three times as much income. There are more people working in the culture sector than there are in the car industry. It’s also a part of our democratic stability. It’s a space where we feel we can have difficult conversations. Is that expensive? No. It’s actually very cheap.

What can we expect from the show at Tate Modern?

We have about 42 works, big and small. Some are entertaining, like Your Uncertain Shadow and Your Blind Passenger, where a tunnel full of smoke gives you the experience of being blind. Of course, instantly your ears get more active, you touch the wall and stretch out your hand so as not to bump into somebody. Other works are more contemplative.

Wasn’t there a plan to stage something outside the gallery?

Yes. We’re installing three waterfalls. We know today there are no real waterfalls left because they’re all human-influenced, if not human-made. So our waterfalls are as real as anything in nature – or as unreal.

Do you consider yourself an environmental artist?

In the show, there is a series of 40 photos of glacial tongues from Iceland, taken in 1998. I believed then that culture and nature were two distinct spaces. I didn’t fully understand that the Anthropocene age had started. When people look at the photos now, they say “this is about climate”. When I took them, it was about their beauty. Soon, I’ll be retaking those photos from the same angles, in the same places. Maybe in October, if I’ve finished, we will sneak in the new pictures so we have the two series hanging next to each other, 20 years apart.

In December, you brought 30 polar ice blocks from Greenland to London and let them melt. Why?

Some 235,000 people were estimated to have been not just walking by, but at the ice – sometimes physically hugging it – and this, I think, made Ice Watch a clear and robust statement. This is what the data from the scientists looks like. This is what a block of ice 15,000 years old looks like. And it’s going to be gone in a week.

How big is the carbon footprint of your work?

We worked with a consultancy called Julie’s Bicycle, which helps people in the culture sector calculate their climate footprint. The London project came to the equivalent of 52 return flights from London to Ilulissat in Greenland. For almost two years, we’ve been trying to come up with a step-by-step solution for my Berlin studio. And whenever I work with museums and logistics teams, I ask them to come up with a response to the climate.

Our readers care about green footprints, but does everyone?

I was with teenage children in Ethiopia in January. They knew all about global warming, they understood about greenhouse gases and how it wasn’t really them, their parents or their ecology that created this problem. There is no place left where people don’t know this. There are deniers in places like the White House who deny things because they’re following other economic or power priorities.

What can artists bring to the climate debate?

Recently, a far right Danish politician lost a huge number of voters and one of the most prominent members of that party said, well, it’s all these climate fools. And immediately, across the political spectrum, people picked up on it, saying “I’m a clown, a fool, a klimatosser“. If we’re going to re-engineer the systems of tomorrow, we need to risk being foolish. Previous models of success can’t be applied. The planet simply can’t host them any longer. We need to take risks.

How has social media affected your work?

It’s kind of the stone age, the way people walk through exhibitions. People walk up to a piece of art that’s very tangible, highly emotional, with sounds and smells and all sorts of things – and they just bloody look at their phone! The problem isn’t necessarily the audience, but the way institutions over-explain everything, as though without a long text people just won’t get it. And once we are used to that, that’s how we react: “My God, there was no text! I had to find out everything myself!” I say, yes, art and culture are hard work, not consumerism. You have to give something to get something.

Does activism consume much of your working life?

I’m lucky that art can be seen to be flirting with activism, and maybe there is a fertilising relationship there. But that’s one of the good things about getting older: you know there are things that you aren’t good at. I’m very content just being an artist.

But you run a business to drive social change.

I have a social entrepreneurship project called Little Sun, which makes a small, handheld, portable solar lantern. On one side, it has a photovoltaic panel, on the other an LED. It replaces the kerosene or petroleum lantern that you would have used previously. Obviously, sitting with an open-wick petroleum lantern is both very unhealthy and very bad for the climate. It’s also expensive.

Is the Little Sun a success?

We’ve done studies on the impact of the lamp. Say a family eats dinner, then the girl does the dishes while the boy does his homework. Once the girl is done, she sits down only to find there’s not enough petroleum left for her homework. One study showed that the Little Sun increased the boy’s homework efficiency by 20 per cent, but increased the girl’s efficiency by 80 per cent. So the Little Sun project is incredibly inspiring.

Simon Ings's Blog

- Simon Ings's profile

- 147 followers