Per Axbom's Blog, page 4

November 15, 2019

Inkludering och hållbarhet för event

För att så många människor som möjligt ska kunna delta och ha behållning av ett arrangemang finns en hel del att tänka på. Det finns tyvärr en uppenbar risk att många arrangörer helt missar att ta hänsyn till detaljer som hjälper människor att känna sig välkomna, och som kan öka deras förmåga till delaktighet.

Ofta faller det på de människor som redan är utsatta, bortglömda och har permanenta eller temporära behov av dessa hänsyn, att själva ifrågasätta och ta strid för sina rättigheter. Men det är självklart inte rättvist att de som redan upplever hinder drabbas dubbelt genom att också hela tiden behöva kämpa för att bli sedda och hörda.

Du kan hjälpa.

Även om du inte själv upplever dig ha dessa behov så kan du uttrycka din omtanke genom att säkerställa att du själv går på sådana arrangemang som aktivt visar hänsyn. När du betalar för arrangemang som utesluter människor så befästs problematiken. När du uppmuntrar önskade beteenden så avlastar du människor som varje dag kämpar med motstånd.

Du kan även vara särskilt proaktiv. Om det inte finns tydlig information om inkludering och hållbarhet, skicka ett mejl med några frågor. Det här hälper också arrangörer att tänka efter före.

Här är en mall du kan använda.

Ämne: Innan jag köper biljett

Hej!

Jag är intresserad av att gå på ert arrangemang. Innan jag köper biljett vill jag dock förhöra mig om sådant jag inte kunde utläsa av inbjudan eller webbsidan:

Är alla lokaler anpassade för enkel framkomlighet för människor med fysiska funktionsnedsättningar?

Finns stöd för att ta till sig innehållet (högtalarsystem, ljudslinga, teckentolkning, live-transkribering)?

Har ni tagit hänsyn till sensorisk påverkan för att minska audiovisuella intryck och/eller erbjuder en yta för att återhämta sig i stillhet? Finns samtidigt tydlig skyltning så att man enkelt hittar rätt utan att behöva hitta någon att fråga?

Finns det en tydligt utpekad person och/eller tillgänglig kanal för att rapportera upplevda obehag om de skulle uppstå (trakasserier, fördomar, med mera)?

Finns det en tydligt utpekad person och/eller tillgänglig kanal för att informera om att man inte vill vara med på bild- och ljudupptagning, eller att kontaktuppgifter delas? Finns samtidigt en rutin för hur man säkerställer att önskemål tillgodoses?

Har ni säkerställt hänsyn till matallergier och doftöverkänslighet?

Finns en strategi för att minimera klimatpåverkan?

Har ni tagit emot rådgivning om inkludering och hållbarhet?

Tydlighet kring dessa frågor i förväg hjälper förstås många människor att förbereda sig på ett bra sätt inför ert event.

Tack på förhand!

.signatur

Jag ber dig inte bojkotta alla event som inte klarar att leva upp till dessa hänsyn. Men hur svaren på dessa frågor ser ut ger dig nog en hel del insikter om arrangörens värderingar och vilja. Och en ökad medvetenhet hjälper garanterat till att ge förändringstakten en skjuts.

Tack för visad omtanke!

Läs också: Sensorisk överbelastning

November 5, 2019

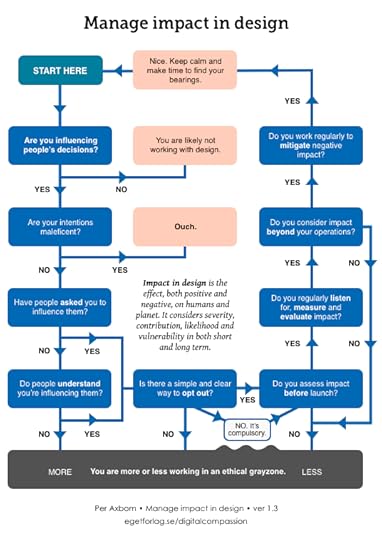

Flowchart: Manage impact in design

The flowchart on managing impact is intended to give you an overview of the elements that help you avoid and mitigate negative impact in digital design. Of course, it likely makes sense for more design situations than digital ones.

I define impact like this:

Impact in design is the effect, both positive and negative, on humans and planet. It considers severity, contribution, likelihood and vulnerability in both short and long term.

With regards to the words in that definition, here is what they refer to:

Severity – How bad (or good) is the effect?

Contribution – If it happens, how much is by our making?

Likelihood – How probable is it that the effect will happen?

Vulnerability – How burdened are the people who experience the effect?

While there are no formal scales for assessing these parameters, they give guidance by allowing us to compare effects to each other and thereby provide input to decisions and prioritizations.

Now, in order to keep negative impact to a minimum, this flowchart provides an overview. Click on the flowchart for a printable PDF version. Each step in the flowchart is explained below.

Start here. The flowchart suggest you start in the top left.

Are you influencing people’s decisions? This is essentially what design does, and so you need to start by acknowledging that you have an important responsibility – also considering how that may translate to accountability.

Are your intentions maleficent? I’m obviously assuming that your intent is more of the good-natured kind, or otherwise you would have little interest in this content.

Have people asked you to influence them? Consent is an important part of doing the right thing. And it’s not truly consent if it’s not informed. This means people understand what they have given consent to.

Do people understand you’re influencing them? Supposing there is no explicit consent, you would have to be able to argue that there is implicit consent in the context of what you are doing. For example, at a magician’s show people have implicitly agreed to be influenced by attending the show and purportedly having an understanding of what magic constitutes. But assuming understanding without knowing they understand can be an ethical conundrum.

Is there a simple and clear way to opt out? It’s not unheard of that some companies make it much harder to end a relationship than start it. In cases where people have invested effort into content that is hosted by an online service, the question of access to that data becomes an important aspect of opting out as well. To be considered ethical, organizations must make leaving simple, clear and without unnecessary obstructions.

NO, it’s compulsory. There are situations where people have no options for leaving because a product or service is part of the workplace, school, organisation or governmental agency that they are required to have a relationship with in specific contexts. In these cases, it’s important to realize that adhering to the following principles of ethical design becomes wildly important as there is no way, or only a very difficult way (for example resigning) to avoid the service.

Do you assess impact before launch? The key here is to make an effort to understand the many ways people could be harmed, before they happen. There is no way of understanding all potential future scenarios, but you will discover – and have an opportunity to mitigate – many more harmful scenarios if you look for them than if you do not. This can involve bringing in and talking to many different people, and allowing them and yourself to brainstorm on the potential risks. By mapping out potential harm beforehand you can avoid a lot of difficult and costly future decisions when a product or feature is live and doing its thing.

Do you regularly listen for, measure and evaluate impact? Of course, once a service is released you can start to learn many new things about how it affects people and their well-being. Having mechanisms in place to gather data about impact, and evaluating how severe the effects are, is fundamental to being able to respond to material harm and working proactively to mitigate it.

Do you consider impact beyond your operations? It’s easy to assume that you only have responsibility for your product and its immediate effects. But more often than not your product is part of larger context and (eco)system, and how it affects people’s lives may not be obvious. For a complete picture of your impact you need to be looking beyond direct use, at autonomy or freedom of choice. You must also understand how the making of your products requires external input: services, energy and labor with questionable safeguards from harm. Addressing these indirect contributions may at first feel counter-intuitive but will become vital in a global economy affected by resource-use, movement of people and climate in ways we have yet to anticipate.

Do you work regularly to mitigate negative impact? With all the knowledge you have when employing these efforts you of course have to take the final step and act on them. Putting a plan in place for how and when you will work with your insights and act on them must in the end be ingrained within the culture of your organisation. Make sure you find your allies and employ help in setting this up.

Answers to these questions will help indicate if you are more or less are operating in an ethical grayzone. By starting at the top you can work your way through and identify your most obvious weaknesses. That way you get an idea of what you can start working with.

Remember to keep calm and make time to find your bearings. It’s rarely an easy task to shift to designing ethically. Try not to do everything at once, but instead to take small steps, one after the other, once you have your goal in sight. Thank you for reading and for walking with me on this path.

—

My next article will address ways of measuring impact.

October 24, 2019

Per Axbom heter jag och är inte ett nyckelord

Jag har fått veta att när man söker på mitt namn så dyker det upp annonser för flera andra svenska konsultföretag och byråer inom digital design och UX. Vilka som dyker upp varierar. Det går alltså till så att en person som söker på mitt specifika namn (“per axbom”) får upp dessa företag som förslag under sponsrade länkar. Personer som letar efter mig lockas alltså till att klicka på andra företag.

Att mitt namn är tätt kopplat till UX och design handlar förstås om att jag under 20 år publicerat en mängd kostnadsfria artiklar, blogginlägg, poddar och inspelade föreläsningar inom dessa ämnen. Det känns först nästan smickrande men sedan ändå olustigt att sökningar på mitt namn genererar annonser till företag som konkurrerar med mina tjänster.

Tack och lov är jag så tekniskt bevandrad att jag inte tror att dessa företag gjort något illvilligt. Antingen har mitt namn halkat med av bara farten i en samling med nyckelord (ibland föreslår Google och man trycker slentrianmässigt okej) eller så använder man mer troligt det som kallas för bred matchning. Ett nyckelord som “UX” med bred matchning skulle kunna göra att annonser även visas för mitt namn.

Nyligen publicerades min bok om att minimera negativ påverkan i den digitala världen. Därför skickar jag Digital omtanke till dessa företag, som ett första steg i en dialog för att komma överens om att de utesluter mitt namn som nyckelord för sina annonser, men också som ett stöd för reflektion. I det här fallet missgynnas jag och min verksamhet, men kanske drabbas vi alla i någon mån.

Jag tar gärna en fika och pratar om hur det blir så här, vilka skador det kan innebära för en frilansande egenföretagare och vad man eventuellt kan göra annorlunda för att mildra problemet.

Bara för att det inte är illvilligt – eller ens medvetet- betyder förstås inte att det är mindre skadligt. Det betyder i stället att vi alltid kan bli bättre på att tänka efter före. Det är just denna aspekt av etisk design som jag utbildar och coachar inom idag, för att säkerställa att så få människor som möjligt, i så liten utsträckning som möjligt, far illa av det vi gör online.

Och till dig som läser, om du är så nyfiken att du ger dig sjutton på att ta reda på vilka företag som dyker upp, så är jag tacksam om du inte hänger ut dem (ingen, eller få, gör sannolikt något medvetet fel). Om du vill kan du meddela privat – då med skärmdump – så att jag kan hitta och skicka boken till alla som på något sätt gynnas av att mitt namn leder till deras annonser.

Fixen är nämligen i slutändan enkel: lägg in “axbom” och “per axbom” som negativa sökord. Då triggas inte er annons på mitt namn.

Kram!

October 20, 2019

Lack of representation in AI puts vulnerable people at risk

In April of 2019 the AI Now Institute of New York University published the research paper DISCRIMINATING SYSTEMS — Gender, Race, and Power in AI. The report concluded that there is a diversity crisis in the AI sector across gender and race. The authors called for an acknowledgement of the great risks of the significant power imbalance. In fact, AI researchers find time and time again that bias in AI reflects historical patterns of discrimination. When this pattern of discrimination keeps repeating itself in the very workforce that calls it out as a problem, it’s time to wake up and call out the bias within the workforce itself.

Providing the most striking and illustrative of examples, less than a month before the research report came out, Stanford launched their Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence. Of 121 faculty members featured on their web page, not a single person was black.

Even a full year before these findings, Timnit Gebru described the core of the problem eloquently, even then referring to a “diversity crisis”, in an interview with MIT Technology Review:

There is a bias to what kinds of problems we think are important, what kinds of research we think are important, and where we think AI should go. If we don’t have diversity in our set of researchers, we are not going to address problems that are faced by the majority of people in the world. When problems don’t affect us, we don’t think they’re that important, and we might not even know what these problems are, because we’re not interacting with the people who are experiencing them.

Timnit Gebru is an Ethiopian computer scientist and the technical co-lead of the Ethical Artificial Intelligence Team at Google. She cofounded the Black in AI community of researchers in 2016 after she attended an artificial intelligence conference and noticed that she was the only black woman out of 8,500 delegates.

While I’m generally not surprised by the systemic discrimination, I am surprised by the lack of self-awareness on display when putting together representative groups within AI. You see, it is quite safe to assume that most AI researchers have read the research paper from the AI Now Institute, that they have been interviewed by newspapers about it and that they stand on stage addressing it. Specialists see the problem, yet often fail to see how they may be part of the problem.

This is why I was especially concerned to see the composition of a new advisory group within the field of AI for Sweden’s government authority for digitalization of the public sector (DIGG). The 8-person team appears to consist of 7 white men and 1 white woman, all around 40 years of age or above. Sweden being one of the world’s most gender-egalitarian countries, this should disappoint.

Of course it doesn’t have to be like this. And shouldn’t. In less than 30 minutes I joined my friend Marcus Österberg in putting together a list of 15 female and/or nonwhite AI experts in Sweden. We obviously shouldn’t stop there, and as many today are pointing out, including Sarah Myers West, Meredith Whittaker and Kate Crawford in their research paper, “a focus on ‘women in tech’ is too narrow and likely to privilege white women over others”. From the report:

We need to acknowledge how the intersections of race, gender, and other identities and attributes shape people’s experiences with AI. The vast majority of AI studies assume gender is binary, and commonly assign people as ‘male’ or ‘female’ based on physical appearance and stereotypical assumptions, erasing all other forms of gender identity.

In the end, the diversity crisis is about power. It affects who benefits from the development of AI-powered tools and services. We need more equitable focus on including under-represented groups. Because if those in power fail to see the issues of vulnerable people, and keep failing to see how representation matters, the issues of the most privileged will ever be the only ones on the agenda.

Further reading/listening

The research paper: AI Now Institute. Discriminating Systems. Gender, Race and Power in AI.

Understand the problem of bias. Can you make AI fairer than a judge? Play our courtroom algorithm game. an interactive article by Karen Hao.

“We’re in a diversity crisis”: cofounder of Black in AI on what’s poisoning algorithms in our lives (MIT Technology Review)

Podcast, CBC Radio: How algorithms create a ‘digital underclass’. Princeton sociologist Ruha Benjamin argues bias is encoded in new tech. Benjamin is also the author of Race After Technology.

Podcast, Clear+Vivid with Alan Alda. I can really recommend this episode of Clear+Vivid where Alan Alda and his producers speak with some of today’s most outspoken advocates for professional women in the STEM fields. We hear from Melinda Gates, Jo Handelsman, Nancy Hopkins, Hope Jahren, Pardis Sabeti, Leslie Vosshall, and many more. Is There a Revolution for Women In Science? Are Things Finally Changing?

In Swedish by Marcus Österberg: DIGG:s AI-referensgrupp 88% vita män

September 20, 2019

Design som lyssnar till hela människan

En återpublicering av anteckningarna jag skrev inför min föreläsning/tirad om etik på World Usability Day 2016.

Inledning / etiketter

Vänner, kamrater, designers, lärare, livsnjutare, fanatiker, köttätare, veganer, användare.

Visst är många ord laddade. Och visst glömmer vi bort hur lätt vi laddar ordet användare med våra fördomar. Användare gör si och användare gör så. Precis som vi säger att ekonomer gör si eller så. Att lärare gör si eller så.

Men alla människor är förstås långt mer komplexa än någon etikett vi kan ge dem. Om en människa har många etiketter kan hen ha många olika mål. Den komplexiteten måste vi vara medvetena om. Och vårda.

(När jag väl stod på scen använde jag ordet vegan för att visa hur det ordet gjort en rejäl resa i hur ordet laddats de senaste 25 åren.)

Kris / drev

Och man lär aldrig känna sig själv så väl som under en kris. För tio år sedan var jag utsatt för ett drev på nätet. Ett drev på den tiden utspelade sig inte på Twitter eller Facebook utan i bloggosfären. Det upptäcktes kanske inte lika lätt av lika många men för den som var utsatt var det förstås en ansträngande upplevelse.

Det här var på den tiden vi bråkade om huruvida vi skulla våga öka bredden på våra webbplatser från 800 pixlar till 1024 pixlar. Och faktiskt också då som UX började leta sig in som begrepp i användbarhetsvärlden i Sverige.

Jag hade skrivit en artikel i papperstidningen Computer Sweden med rubriken Sökmotoroptimering är alltid fult. I korta ordalag gick den ut på att när vi medvetet manipulerar sökresultat så förhindrar vi Google från att ge oss det som är mest relevant. Vi sätter hinder i vägen för att människor ska få hitta det som de kanske egentligen hade störst behov av.

Nåväl, här är ett kostnadsfritt tips. Om det är någon man inte ska bråka med så är det SEO-världen, de människor som är duktigast på att just få deras sidor att hamna högt i sökresultaten. Några försökte också, skapade sidor med mitt namn där jag kallades för idiot. Men den tuffaste dialogen skedde i SEO-forum på nätet. Jag tog mig in som medlem i forumet och ägnade sedan dag och natt i tre dygn att besvara och bemöta påhopp. Min närvaro gjorde att de värsta påhoppen, som skrivits innan jag gick med, tunnades ut. Men oj vad jag hade ont i magen.

Efter dessa tre dygn avslutades i princip tråden med att en respekterad SEO-konsult – Nikke Lindqvist – gick in och svarade… “jag har läst och kommit fram till att jag håller med Per Axbom i precis allt det han skriver, utom rubriken”.

Vilken befrielse de orden var. Det var som en kontinent lyftes av mina axlar. Jag var inte galen. Jag kunde nå fram med vad jag verkligen menade.

För visst var det så att många blev så uppjagade att de inte läst förbi rubriken. Och gjorde de det så hade de ändå redan bestämt sig för vilken idiot jag var.

Jag är så evigt tacksam gentemot Nikke för att han tog sig tid att lyssna på det jag egentligen sa.

Jag kom faktiskt ur den här upplevelsen flera vänner rikare. Jag kom också ur den med en stark drivkraft, en drivkraft för att visa hur man bättre kan arbeta för att göra gott, att jobba användarcentrerat, att vara på användarnas sida.

Hinder / helhet

Jag har alltid varit en person som irriterar sig på designfel. Om en dörr är svår att öppna deklarerar jag det gärna högt och tydligt. Om logistiken i lunchrestaurangen påkallar det så säger jag högt att mjölken borde stå efter kaffet. Men det är inte Don Norman, mannen som myntade begreppet UX, som är min största förebild, utan en kvinna vid namn Lillian Gilbreth, som är sorgligt frånvarande i historieböckerna.

Hon och hennes man, som startade sina karriärer på 1920-talet, ligger bakom hur operationsläkare placerar sina verktyg och får dem tilldelade av en assistent. Själv gick hon även vidare och listade ut hur skolbänkar med lock skulle minska spring i klassen och göra både lärarnas och elevernas jobb lättare. Hon ligger också bakom en designprincip som används för många kök idag som anger hur spis, kylskåp och diskho ska vara placerade i förhållande till varandra för att minska belastningen på den som jobbar i köket.

Gilbreth anses av många vara världens första industriella psykolog. Hon förstod behovet av att inte bara titta på tiden som aktiviteter tar att utföra och eliminera hinder för att minska tiden. Hon såg hela människan och tog även i beaktning saker som ljussättning, ergonomi och tristess.

Jag har nu själv ägnat många år i användarnas tjänst och många gånger pratat om hur viktigt det är att se hela människan. Att UX skiljer sig från användbarhet i att vi inte bara ser till användandet utan även hur människan utvecklas i användandet. Att vi ser bilden av människan innan och efter de har kontakt med vår tjänst eller produkt.

Psykologi / nudging

Som en bekräftelse på hur viktig människan är så vann en psykolog 2002 års nobelpris i ekonomi. Daniel Kahneman och de senaste 30 årens forskning om mänskliga beteenden har varit en viktig inspirationskälla för många av de principer som vi använder inom UX idag. Tillsammans med Robert Cialdini står han för många av de begrepp vi anammar i design: Priming, framing, reciprocity, liking, belöningar. Det har blivit en del av verktygslådan som UX:are använder sig av.

Men de senaste åren har det dock börjat gnaga i mig ordentligt. Jag upplever kognitiv dissonans, det vill säga att jag inte alltid agerar i enlighet med mina värderingar. Två saker:

Evig förenkling. När jag hjälper människor att utföra aktiviteter online. När har jag hjälpt dem för mycket. Om jag eliminerar hinder och tar beslut åt människor blir de då i förlängningen inte sämre på att ta beslut? När blir det för lätt?

Det är skillnad på begär och behov. När jag hjälper till att tillfredställa kortsiktiga begär, vilka långsiktiga behov arbetar då människan mindre med?

Vi pratar om och anammar nudging och gamification som något positivt samtidigt som vi kritiserar spelbranchen som har många krav på sig att motarbeta beroende. När vi använder samma principer inom UX står det inte en myndighet och kollar om vi agerar på ett etiskt sätt.

Tar vi ansvar för det eventuella beroende vi skapar? Att vi arbetar ”för det goda”? Hur kan vi veta det?

Om vi verkligen står på användarnas sida så kan inte vårt mål vara att så få som möjligt ska ta egna, genomtänkta beslut.

Hur kan jag med säkerhet avgöra vad som är viktigt för en annan människa. Hur många chanser ger jag människor att tänka över sitt beslut att använda min tjänst? Hjälper jag människan att agera utifrån sina egna värderingar och sin egen målbild?

Vi kanske skalar bort externa hinder, men de interna utmaningarna slutar inte att komma: Gjorde jag rätt nu? Vill jag hit? Kan jag ångra mig?

Har vi gjort ett bra jobb för människor för att de fortsätter komma till vår webbplats?

Coaching / drivkraft

Sedan ett år tillbaka arbetar jag även som coach och som coach är det viktigt att lyssna, att inte styra personer. Att hitta drivkraften inom sig själva. Drivkrafter är något som måste komma inifrån för att leda till bestående förändringar.

Speciellt en coaching-session som jag hade tidigt under min utbildning gjorde väldigt stort intryck på mig. Min klient behövde bygga en webbplats för att marknadsföra sin nya verksamhet. Något som jag har otroligt mycket åsikter om och erfarenhet av. Min egen utmaning var att inte dela med mig av mina åsikter. Fyrtiofem minuter senare hade han en färdig plan för hur han skulle ägna specifika dagar de närmaste två månaderna till att utforska och bygga sin lösning. Det var garanterat inte i linje med de råd jag skulle gett, men det var något som han kommit fram till utifrån singa egna förutsättningar och därför oerhört mycket mer värdefullt, oerhört mycket mer sannolikt att han skulle genomföra det.

Jag vill inte tänka på hur många inom UX skulle arbeta för att göra det lättare att bestiga Mount Everest. Vi sätter in en rulltrappa och lite schyssta restauranger längs vägen? Vi tar bort det jobbiga så att det blir en oförgklömlig upplevelse… Men så klart: DET ÄR DET JOBBIGA som är upplevelsen! Människor mår bra av att använda sina kroppar, sitt intellekt.

När jag vill att utvecklarna i mina team ska jobba mer med tillgänglighet så säger jag inte åt dem vad de ska göra… jag berättar om Göran som använder en talsyntes för att ut pengar på banken och så säger jag att Göran måste kunna använda vår webbplats också. Jaha, hur då? Säger de. Och jag svarar ”Lös problemet.” Gissa om det blir bra lösningar när människor får en utmaning. När det får något att kämpa för. I just det fallet krävs förstås att jag har en förståelse för deras drivkraft.

Alltför mycket inom UX handlar om att placera saker på rätt sätt så att man inte kan missa det. Men låt människor kämpa också. Låt människor överkomma hinder, demonstrera för oss att de drivs av ett riktigt behov och inte av minsta möjliga motstånd.

Lämmeltåg / hållbarhet

När vi pratar om att skapa lösningar för att påverka människor för en bättre miljö, så är det för att människor enligt vårt sätt att se det gör fel. Människor gör självklart inte fel för att de är elaka. Människor kör inte bil för att de är elaka, människor äter inte kött för att de är elaka.

Däremot har människor väldigt lite tid att att reflektera över sina handlingar. Det är lätt att falla in i mönster. Människor blir inte lyssnade på, inte ens av sig själva.

Vad är mina värderingar och ligger det jag gör i konflikt med min målbild? Vilka andra vägar skulle jag kunna ta mot mitt mål? Hur många människor tar sig tid att tänka så?

Samtidigt ökar antalet fall av utbrändhet, och psykiska sjukdomar bland ungdomar växer lavinartat.

Självklart är det inte klimatet som är hotet. Det är människor. Så långt är vi ofta överens, men sedan försöker vi behandla människor som lämmeltåg som ska styras in i det ena eller andra spåret. Vi sätter ett hinder där, en belöning där och så vips så har vi människor som jobbar för hållbarhet.

Det ser jättebra ut ett tag och så startar nästa säsong av game of Thrones och vips gör alla något annat.

Problemet är människans ständiga uppsåt att hela tiden försöka styra andra människor.

Påverkan / paradox

Här är paradoxen med nudging: Om vi kan påverka människor så kan andra göra det också. Hur kan vi vara säkra på att andra inte lyckas bättre med sin nudging. När vi utsätts för hundratals om inte tusentals nudging-försök varje dag. Hur konkurrerar jag med det? Hur många av dessa vill människan väl?

Om vi sätter nudging som ett sätt att hjälpa människor så har vi ingen konkurrensfördel. Alla gör det. När jag var på Almedalen i somras var det ovanligt om ett seminarium inte nämnde begreppet nudging som en väg framåt för att förändra människors beteenden. Alla vill göra det. Många får pengar för att göra det.

Hur värdefullt var det att vi lyckades få människor att duscha mindre i bostadsrättsföreningen? Det visar sig även att när människor duschar mindre så måste stamspolning ske oftare därför att rören hinner korka igen av smutsen när folk duschar så sällan. Vi lyckas inte alltid tänka hela vägen. När vi sätter oss i en situation där vi säger att vi vill påverka många andra så måste vi nog också vara säkra på att vi gör rätt.

Jag har nyligen läst om psykologisk reaktans, ett fenomen som innebär att människor som känner att de utsätts för extern påverkan kommer att slå tillbaka genom att göra precis tvärtom. När någon får känslan av att någon tar bort hennes val eller begränsar valmöjligheterna kan det göra att personen antar en ställning som är helt motsatt vad som var avsikten – och ökar resistensen mot vidare påverkan. Sannolikheten att du kommer kunna påverka den personen efter att du har försökt påverka dem, blir alltså mindre. Det byggs upp en motståndskraft så stark att fakta inte biter. Det kanske känns igen i våra nätdebatter?

Jag tror inte vi har har fått den här fantastiska kunskapen om hur beteenden skapas så att vi kan använda oss av metoder för att påverka människor i ena eller andra riktningen. Jag tror vi fått den här gåvan för att kunna identifiera när, och undvika att, människor utsätts för påverkan i alltför stor utsträckning.

Förändring / frihet

Om vi i stället hjälper människor att hitta sin inneboende drivkraft så blir det svårare att påverka dem. Och det är något bra. När människor inte påverkas lika mycket av alla externa drivkrafter får de mer tid att bli bättre versioner av sig själv. När människor hittar sin egen kreativitet kommer vi att få långt fler idéer och lösningar om vad var och en kan göra för hållbarheten. Vi måste inte alla göra samma sak. Vi är olika men det betyder inte att människor inte bryr sig om hållbarhet.

Vi måste sluta se på människor som lämmeltåg som ska styras i den ena eller andra riktningen. Vi måste i stället förstå varför de inte känner sig ha tid att göra sitt bästa. Och ge dem tiden. Inte överösa dem med ännu mer krav, förvänta oss att de ska dansa efter just vår pipa. Och en människas handling måste inte vara samma som en annan människas handing.

Jag äter inte kött men det betyder inte att jag prompt måste påverka alla andra till att sluta äta kött. Min svärfar som för ett år sedan direkt kopplade ordet vegan till att släppa ut minkar ur burar, kom till mig för två veckor sedan och sa, “Jag förstår varför du inte äter kött. Du gör helt rätt.” Jag har inte försökt påverka honom och han kommer inte att sluta äta kött, men han bidrog där och då med något oerhört viktigt: ibland så behöver människor också bara få bli hejade på och få glada tillrop för att orka fortsätta. Och om han donerar pengar till trädplantering i stället så får det vara hans sätt att bidra och jag kommer heja på det. Om vi bryr oss om människor så ger vi dem möjlighet bidra utifrån sina egna förutsättningar. Många gör redan mer än vi kan föreställa oss, men vi har inte tagit oss tid att lyssna på dem utan att döma. Vi är så upptagna med att ställa krav på dem.

När jag skulle köpa en vinterjacka nyligen fick jag lite panik som konsument. Jag ville inte ha dun som plockats av fåglar. Jag hittade EcoDown, som är dun skapat av återanvända PET-flaskor och tänkte att det var en smart lösning. Sedan fick jag förståelse för hur dessa mikrofiber av plast letar sig ut i naturen och hamnar i födan hos mindre djur och fiskar, skapar lidande och gifter som letar sig upp i näringskedjan till oss människor igen. Likadant förstås med polyester. Det enda sättet att konsumera rätt idag idag är att inte konsumera alls. Men det stora fokuset på hållbarhet gör att det satsas miljarder på nudging, att påverka oss att köpa det ena eller andra ”miljövänliga” alternativet. Inte konstigt att det blir fel.

I stället för att ägna oss åt att designa om dörrhandtag och dörrar så att de blir mer attraktiva, att placera ut massor av dörrar som ska locka in människor till den bästa lösningen, så kanske vi borde hjälpa människor att först tänka ut vilken dörr som passar just dem.

Dörren / Avslut

För ett par månader sedan stod jag på Medborgarplatsen tillsammans med en grupp vänner. Vi stod utspridda höll varsin skylt. På den stod det: “Gratis lyssnande.”

Erfarenhet av en sådan aktivitet ger otroligt mycket förståelse för hur ovanligt det är med riktigt lyssnande. Om jag aldrig får uttrycka mig själv och formulera mina behov inför andra, hur ska jag då själv kunna höra vad jag egentligen tror på och vill med mitt liv?

Min uppmaning till alla som jobbar med UX idag är att lyfta blicken. Fundera inte så mycket på dörrhandtaget, dörrens utformning eller var den står. Sträck ut din hand, fäll ner dörrhandtaget och hjälp din användare att ta ett steg igenom dörren och verkligen förstå vad som finns bakom den. Ta in vad det innebär att vara där. Är det en bra plats? Om inte, gå ut, stäng dörren och välj en annan.

Jag var nästan på väg att kalla den här föreläsningen för UX är alltid fult. Men även om jag är säker på att ni skulle hållt med om mycket av innehållet så skulle ni garanterat inte ha hållt med om rubriken. Och inte heller jag gör det. Jag har lärt mig min läxa.

Däremot tror jag att vi tillsammans, som designers, kreatörer och skapare av framtiden är redo att ta nästa steg i utvecklingen av vår bransch, från användbarhet till UX till nästa steg för att se – och lyssna till – hela människan.

Tack.

September 18, 2019

Managing persuasive defaults in design

As part of the feedback and reactions to my recent post on the Dangers of Nir Eyal’s books, I received a very relevant question. It relates to how we as designers architect the choices that are available to users, and thereby influence their decision-making. How much of this is really okay? My response turned out quite long and I offer it in a more accessible format here.

The question from Sam Horodezky reads as follows:

Per what do you think about harnessing basic findings about how to frame a problem; for example, if you set as default during employee benefits onboarding to deduct money from the paycheck, it is well known that employees are more likely to save for retirement.

And my response, only slightly revised after my Twitter harangue:

This is an excellent example. There are many ways in which defaults are taught in design as a way to encourage specific behavior. I’m gonna try and break down my process using your example. Bear with me:

First. We are assuming that it is better for employees that we take responsibility for saving for their retirement. To identify risks with this assumption I would run a session asking for situations where this could be considered wrong or harmful.

For example:

A person is terminally ill and money is of value now but not later.

A substantial inheritance is known about as a future installment and there is no need for saving.

The person is more adept at investing and can make money grow faster elsewhere.

Now these scenarios were off the top of my head. But I’m a middle-aged white privileged dude. So this is where it becomes immensely important to bring in people who are experts at understanding risk, because they are themselves always at risk. I don’t fit that profile.

I try to help people understand this in general when I work with usability and accessibility issues. By bringing in those who are experts at seeing how people could get hurt (because they are the people who keep getting sidestepped) we can identify many more risks.

Once we have a list of risks we evaluate the impact of each:

Who is potentially harmed?

How vulnerable are they?

How serious is it?

How likely is it to happen?

How much of this effect is our doing?

By mapping out the impact we can get a better understanding of how much sense it makes to ignore a risk or take actions to avoid it. Generally if a person is vulnerable and the effect is serious, that is a stronger case to take action.

Sometimes we won’t be able to find risks that would motivate a change in the assumption, and sometimes we will. By doing the exercise we will feel much better about the decision, and we have documentation to prove our efforts.

But, it doesn’t end there of course. Our assumption now is that we’ve done our due diligence. To disprove that, we have to set mechanisms in place for listening. This exercise or similar needs to be repeated regularly with feedback solicited actively and passively.

One thing I’d add is to not only involve the risk experts but also leadership and other stakeholders. By participating in impact assessment they also feel more ownership of the outcome. And positive impact can be mapped as well to find a sensible balance.

In the end, it’s all about communication. We get a feel for the room and communicate our message. Then we listen. We listen to see if our message is received and understood. And if it benefits the recipient. Or even harms them.

In many projects, products and services people stop listening at one point or another. And that’s when the discovery of harm is left to chance and whatever happens when trust deteriorates. If we’re lucky, people get angry. Worst case they disappear.

Design is a powerful force. And defaults are extremely powerful if we have a large user base. It’s easy to get distracted by that power and miss the many people at the edges of our research. The best we can do as designers is to promise ourselves to not ignore them.

To protect people we have to assume there are weaknesses in our assumptions. By making people aware of our assumptions there is a greater chance they give us something to listen to. If we hide our assumption from them, we are making it rather difficult for them to object.

Addendum:

Your decision on making people aware – or not – of how you have decided to help them, will be a reflection of how much you believe they should be granted autonomy. From case to case this may not be a self-evident decision, but what should be self-evident is that you always set aside the time for reflective reasoning.

September 17, 2019

How Nir Eyal’s habit books are dangerous

Hired as a speaker throughout Silicon Valley and the international tech world, Nir Eyal’s appeal and influence cannot be ignored. He literally wrote the book that has helped many startups and corporations exploit human weaknesses for profit. He’d just rather they have good intentions.

Using many of the same concepts found in game mechanics and gambling, Nir Eyal’s teachings assist the creation of technology that uses variable rewards systems to make people… not necessarily smarter, happier, or healthier… but primarily: hooked. To his credit, Eyal does not hide behind a euphemism here. In a many dictionaries the example sentence for hooked references narcotics.

hooked. adjective.

informal: Addicted. “A girl who got hooked on cocaine.”

Devoted to or absorbed in something.

— (lexico)

It’s not hard to imagine how ”addiction” springs to mind when discussing the habit-forming techniques outlined in the book. When thinking about video games and casinos, though, remember how playing the game often is the goal itself. Choosing to participate is part of the deal, and for added protection there is often a good deal of regulation around the latter.

Conversely, in the many “free” online communities we devote our time to in the 21st century, few people are aware that they are entering a veritable casino — a place designed specifically to keep them staying longer and paying attention to targeted messages. Now, some people will enjoy themselves thoroughly, accepting the game, some people will not be as hooked as others and others still will feel like their time is stolen from them. People with such a variety of experiences may not understand each other’s reactions, and may argue over whose experience is more valid. Arguments that feed back into the system.

Whether you appreciate them or not, book 1 helped make sure to help put those habits in place. ”Like us, or don’t like us? Discuss. Here is a text area for you. Just make sure you discuss it on our platform.”

Book 1 giving you a headache? Take book 2 and call me in the morning.

In a second book Nir Eyal now wishes to help people distance themselves from the distractions they are hooked on, and become better at taking control over their own life.

Let’s just take a moment to appreciate the irony of how book 2 is written to help people get out of the habits that book 1 taught the tech companies to impose on them. The pitch to the publisher is easy enough to imagine:

“Are you sure there’s a market for this book, Nir?”

“Am I sure there’s are people out there with habits they don’t want? Sure, I helped put them there!”

Cennydd Bowles has a great analogy for this: Poachers turned gamekeepers.

But what about the good habits?

Time and time again, I see the argument that getting people hooked is good if the outcome is positive. Like exercising, like eating healthier, like taking steps to improve the environment. Rarely do I see these arguments address the fact that there are billion-dollar industries focusing minute-by-minute on making us do the exact opposite of positive. And I have a decent idea about which books they read.

The idea that we create change by deviously influencing people to create so-called positive habits, instead of educating them about the many actors already influencing their habits, is a maddening concept for me. If “winning“ relies on getting people subconsciously hooked on the “right stuff”, then we’ve already lost.

I’ll give you this, there are for example exercise apps that help people make changes in their lives. Ones that employ nudging. But once again, these apps were chosen and asked to do just this. I purposely downloaded the app and asked it to nudge me in a certain direction. It’s as close to consent as many apps come in this industry at the moment.

Please note how this differs immensely from downloading an app that is covertly pushing me in a thousand different directions I did not ask for, have not consented to and am likely only vaguely aware of.

And please forgive me, because to make the above point I had to leave out how most health apps are based on bogus science. You’ll notice how I didn’t say the habits they create are necessarily positive.

Nir Eyal and ethics

I of course do not believe Nir Eyal has any evil intent. He says himself he has the exact opposite intent. He wants people to build good, healthy products and use his teachings to attract and keep a user base and change people’s behavior for the better. To reason around good intent, Eyal has even coined the phrase “the morality of manipulation”.

This comes very close to saying that removing people’s autonomy, regardless of the will of the person, is fine as long as you’ve decided that the behavior you are promoting is for the greater good. Is this an unfair interpretation? Please read on.

What I do believe is that Eyal is really good at popularising certain ideas and concepts on human behaviour that others can readily make use of for their own gains. But a focus on simplifying human behavior can lead to some really dangerous assumptions. Some of them strikingly naive.

I am far from the first to criticise and point out how Eyal’s teachings can be used for human exploitation. But the consequent thinking about consciously managing negative impact has not reached the level of maturity one might hope.

In February 2018 Nir Eyal was interviewed for Journalism + Design. One question was: “How can companies build products that are persuasive but not coercive?”

This is Eyal’s response:

There are two questions I tell people to ask themselves:

1. Do you believe the product you’re working on materially improves people’s lives?

2. You have to see yourself as the user. In drug dealing, the first rule is never get high on your own supply. I want people to break that rule and get high on their own supply, because if there are any deleterious effects, you will know about them.

There’s a simple market incentive to not build products to screw people. We’re not automatons, we’re not manipulatable puppets on strings. If a product hurts people, they’ll stop using it.

If I last year had said anything remotely similar to this I would have been ousted by the design industry.

I am distressed by how someone can respond to a question of ethics and not mention anything on actually speaking to other people, involving people who are regular victims of prejudice and mistreatment, or even maybe regularly listening for harm. No, the 2-step program ask of you to believe you will do good and try the product yourself, and you’re good to go. The powers of the market will protect people from harm.

Also, by his own account, Eyal has worked with the tech industry for years, even early on involved in building apps. He has taught a course at the Stanford Graduate School of Business on product design. And yet this simple truth is not expressed: You as the maker do not pretend to be a user. That’s a recipe for disaster, destined to miss important issues with usability, accessibility, diversity, exclusion and impact. Only people not involved in product development will uncover what you are too biased to see. Stanford’s own design school includes in its core abilities ”Learn from Others (people and contexts)”. Thankfully ”Pretend to be the User” is not one of them.

Honestly, what saddens me the most in all of these conversations is this lack of recognition that the people who are being harmed the most are the ones always sidestepped by society, with no voice and no platform to object or stand up for themselves. Not always marginalised but almost always edge cases.

And herein lies the danger, and why I believe Eyal’s books cause significant ethical issues. While providing tools to start experimenting with habit-forming techniques there has to be some reflective reasoning around the potential for negative impact. Something beyond ”your intent and the powers of the market will keep everyone safe”.

But the second book, will it not release people from the powers of habit and make the dangers of the first book obsolete? Well the premise of the second book seems to be exactly this: don’t fight the companies, they are only doing their job, fight your own lack of discipline. Apply yourself and set yourself free from those investing billions to influence your choices.

The takeaway here seems to be that if you’re having problems, the problem is you. I believe it’s fair to point out the intrinsic dangers in this type of assertion. I am a strong believer in that many people can become better at controlling their own emotional reactions to the world around them, but it is precisely because this is a very hard thing to do that we as humans are susceptible to external influence. The very reason why much of the advice in book 1 really works.

To be clear, it is not always the teachings themselves I object to but the lack of guidance around them, or when an illusion of guidance actually exacerbates potential harm. Such as getting high on your own supply.

Guidance would be things like:

Design to change habits is a super-interesting concept, but how about making sure we design with people, with their consent, and not at them.

There is no sure-fire way to change habits (individual traits, external factors and context matters) which is why we have to be really careful about listening to outcomes so we’re not pushing people in a detrimental direction. What I’m saying here is that even with positive intent (as Eyal tells you to abide to) there are obviously dangers.

People can indeed be empowered to better manage their relationships with digital services, but the ability to do so is also influenced by education, power of voice, social support, time, health and resilience. Regulation can help protect those devoid of power to influence the market. Consumer rights are not governed by waiting for market forces to rectify themselves.

That some people have a healthy and joyous relationship with a digital service does not mean that the same service is not also causing a negative impact for a significant number of other people. These two things can be true at the same time, especially with companies dependent on maintaining a massive user-base for their survival.

Impact also applies to people who are excluded. There is something to be said for bridging gaps rather than widening them.

I’m positive you can help me think of more guidance to avoid hurting people with these tools.

Surely, people will see through any wrongdoing?

There are also inconsistencies in the messaging around habit-shaping. Arguments like this pop up:

So in this day and age, if you screw people over, if you make a product people regret using, guess what? Not only are they going to stop doing business with you, they’ll tell all their friends to stop doing business with you. — Nir Eyal

Seemingly never having heard of fake reviews, sometimes Eyal does indeed seem to be saying that the customers, consumers and citizens will prevail in this struggle, because they will see companies for what they really are, and spread the word. But he is simultaneously arguing for companies to create habit-forming products, ones that people use without thinking. Since Eyal likes to allude to narcotics, I’m keen on understanding how a corporate focus on making people unconsciously hooked aligns with empowering people to use less of something, and incentive to tell their friends to stop using it.

I would say the argument that people will just stop using bad products is a dishonest one. Especially for a behavioral scientist. Today we know so much more about how emotions and fear control human behavior. The concept of people as rational creatures is a dwindling one – emphasised by Daniel Kahneman and Richard Thaler’s respective Nobel Memorial Prizes in economics. Consider, for example, how much more we understand today about why people stay in abusive relationships. You don’t have to be addicted to be impelled down a dangerous path by habits.

Of course, it is not likely that Nir Eyal himself truly believes that people will simply leave bad relationships with products. He is otherwise quoted as saying, more to his point: “The best products do not necessarily win.” Really, the point of his teachings have been to create “a monopoly of the mind” and make products “that people turn to with little conscious thought”.

I can’t remember the last time someone solicited my subconscious to make me spend time with them, and I decided to leave them and tell all my friends, I’m no behavioral scientist, but I’m going to presume this is because the whole point was for me to never be conscious of it happening. And to my point, even if I enjoyed the interaction it does not necessarily follow that the manoeuvre was ethical.

Few people can, with a straight face, assert that people will just leave companies that apply bad tactics, and then write a whole book on the premise that people will not just leave companies that demote their well-being.

But Eyal just did. In fact, it would seem people now need Eyal’s second book to exercise forethought and discipline for managing these relationships with products. Obviously, the companies that underpin this need are in no way culprits here. I mean, all they did was follow advice from the first book. Good on them.

Rounding off, I really want to emphasise that I still believe Nir Eyal when he says he has positive intent. But sometimes even positive intent backfires and we all – including myself – need to proactively take responsibility, and recognize accountability, for the ideas and knowledge we share. Minimising negative impact is also about seeing and responding to the many ways people can take your work and misuse it. I hope to highlight dangers to boost awareness. In the end, I much prefer conscious decision-making over subconscious when impacting both others’ and my own well-being.

Sources and further reading:

Is Big Tech addictive? A debate with Nir Eyal. A podcast episode where Ezra Klein and Nir Eyal disagree over the role of technology in hijacking our attention. Here is where Eyal argues that people need to take responsibility for their own actions, and explains how he started wondering why people don’t do what they know they should do.

The Nir Eyal Hypothesis: Products That Create Desirable Habits Win in the Long Game Podcast episode providing good insights into how Nir Eyal reasons. Here we find examples of quotes that when read together will contradict each other.

Nir Eyal on Persuasive vs. Coercive Technology This is where I found Eyal’s idea for a 2-step program on how to avoid coercing people.

“Distraction Starts from Within; It is Our Never-ending Search for an Escape from Psychological Discomfort.” Here is Gretchen Rubin’s interview with Nir Eyal and it is a strictly positive take on his work. I think it’s good to remember that this is how the vast majority looks at his teachings.

August 28, 2019

Messages in WhatsApp are stopping immigrants

Information stored on phones is increasingly used in court cases and to determine the trustworthiness and honesty of people seeking to enter another country. So what happens when the source of the information is someone else entirely, and you had no intention of saving it on your phone or even awareness that it was happening?

As reported by Abed A. Ayoub, Legal and Policy Director of American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee (ADC), people are being denied entry to the United States due to messages sent through the WhatsApp messaging service.

At least twice a month I have clients denied entry because of something in their WhatsApp. Most of the time its pictures or videos forwarded to them in a WhatsApp Group. Many tools being used to stop immigrants from legally entering.

Here is a transcript of parts of an interview, by US Department of Homeland Security, determining right to entry. The interviewer is questioning content on the respondent’s phone.

A. It was broadcast on WhatsApp I received news and I have nothing to do with these. They came to my app.

Q. When did you receive the photos on WhatsApp?

A. I don’t know.

Q. Do you understand the concerns of the United States and its citizens when considering the graphic nature of the images on your cellphone?

A. Of course I understand no one finds the graphic pictured pleasant. It’s inhuman.

Q. Have you ever had military or weapons training anywhere in the world?

A. No.

Q. Considering the totality of this interview and the content on your cellphone. You have been found inadmissible to the United States pursuant to Section 212(a) (7) (A) (i) (I) of the Immigration and Nationality Act. You will be removed from the United States on the next available flight. Do you understand?

(source)

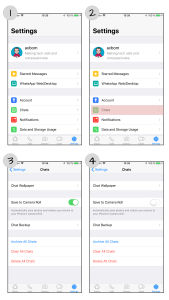

The complication here is that individuals can be members of discussion groups where other members post incriminating content. What responsibility does the first person then have to delete that content from their phone? One significant issue with WhatsApp specifically is the default setting of automatically downloading WhatsApp media content to the photo library on the phone. This means that anyone targeting immigrants can join a discussion group and send violent or pornographic images and films to these groups, and have those images and films stored on the recipients’ personal phones.

While such a person would likely be thrown out of the group, the damage has already been done. The content has been saved to private photo libraries, often without the recipients even considering it.

The other issue is that anyone can be added to a discussion group, and be a recipient of content, as long as the sender has access to that person’s mobile number. To be clear: I don’t even need to be part of a discussion group, someone else can add me without my permission. Access to mobile phone numbers are quickly becoming a privacy issue.

Of course there will be instances where content on a phone is valid reason to deport a person, but there is a considerable source of disarray here, including risks of maleficent targeting, that will result in many false positives. Truly understanding how the content ended up there is vital to a fair assessment.

It’s important to be aware of how services like WhatsApp work, both as a consumer and as an official. A sound recommendation is always to turn off the feature that saves videos and photos to the camera roll.

Turn off this behaviour by going to Settings » Chats and disabling the toggle next to “Save to Camera Roll”. The other option of course is to stop using WhatsApp (A Facebook service) and opting for safer alternatives.

Image: How to turn off saving of images to the camera roll (click to enlarge)

Image: How to turn off saving of images to the camera roll (click to enlarge)Awareness needs to increase about the risks of jumping to conclusions about what anyone’s phone content implies. Share this story and if you have any similar experiences, do not hesitate to let me know.

August 26, 2019

Naiv vårdslöshet med privat information i offentliga system

Det varnas nästan dagligen om hur de globala jättarna i sociala medier är obetänksamma med vår privata information. Att demokratin hotas i sina grundvalar. Tyvärr tar det gärna fokus från läckorna som händer nära oss – där vi hela tiden tänker att vi är säkra. När samhälleliga tjänster regelbundet brister i säkerhet måste den digitala tryggheten adresseras på nationell nivå.

Nu har det än en gång visat sig hur ett offentligt system misslyckas med att skydda den information de har ansvar för att skydda. Namn, personnummer och omdömen för 140 000 barn i Stockholm har gått att nå för den som själv har varit inloggad i skolplattformen och haft grundläggande förståelse för hur information om namn och scheman hämtas.

Det här följer på en rad avslöjanden om oförsiktighet med privat information i offentliga verktyg. Och det kommer inte att vara den sista gången.

Har våra offentliga och statliga verksamheter kompetensen som krävs för att göra rätt? Eller hindrar omständigheter som upphandlingar, prispress, tidsstress och otydliga mål dem från att göra ett bra jobb – och skydda oss?

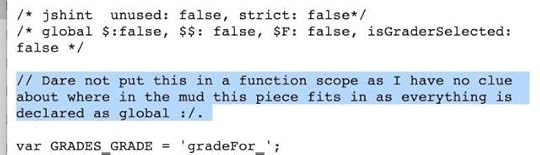

Utvecklare förstår inte koden

Det finns nämligen en historia till i den här härvan som medierna har missat. En av utvecklarna som bidragit till skolplattformen, antingen direkt eller indirekt, har skrivit en kommentar i koden, en förklaring för att hjälpa andra att göra rätt.

Min förenklade översättning av kommentaren:

Våga inte använda den här delen eftersom jag inte har en aning om var i gyttjan den passar.

Skärmdump från föräldern som gjorde avslöjandet:

Det här är uppseendeväckande och borde leda till brådskande utredningar.

Om utvecklarna – som står för ett säkert system – själva inte kan redovisa hur trådarna hänger ihop, då har vi omfattande problem. Kände de som var medvetna om kommentaren tryggheten att kunna säga ifrån, att räcka upp handen och protestera? Och om någon gjorde det, fanns det beslutsfattare som lyssnade?

Vilseledande försvar

Förtroendet grusas ytterligare när Stockholms stad går i försvarsställning för sin plattform som de själva vet är förföljd av brister. Det pratas om att man måste “ändra i programmeringskoden” för att få ut informationen. Det är fel. Om någon kunde ändra i koden skulle vi ha ett ännu större problem.

Föräldern som upptäckte säkerhetsbristen säger själv:

Reagerar på att ansvarig på staden säger att jag ‘ändrat i programmeringskoden’. Det är väldigt vilseledande. Det jag gjorde var mer som om jag skulle måla över en av siffrorna på mitt bankkort med en annan siffra och plötsligt dras pengarna på nån annans konto.

Programmering börjar bli en alltmer utbredd kompetens. Vi är hundratusentals som förstår att det inte var svårt att få tillgång till all information via plattformen. Ge gymnasieelever en checklista och de klarar av det på tio minuter.

Så hur försäkrar vi oss mot offentliga verksamheters naiva vårdslöshet? Svaret är givetvis att vi måste sluta ge dem vårt förtroende om de inte ger oss sin transparens tillbaka. De måste – på riktigt – förstå allvaret när de brister i sitt ansvar. Dessutom måste de – på riktigt – erkänna hur allvarligt det är.

Vem säkerställer medborgarnas skydd?

Dataskyddsförordningen har gett oss rätt att bli bortglömda, att avlägsna vår information från system och plattformar vi inte litar på. Rätten till skyddad information har blivit en mänsklig rättighet. Men om våra statliga system är källan till läckorna – och de systemen dessutom är obligatoriska – hur säkerställs då våra mänskliga rättigheter?

Digitaliseringsrådet, med Anders Ygeman i spetsen, ska hjälpa regeringen med strategiska analyser och rekommendationer. Digital trygghet är ett av sex delmål i digitaliseringsstrategin för Sverige, eftersom det måste “finnas goda förutsättningar för tillit och förtroende i ett digitalt samhälle”. Här är “höga krav på säkerhet” ett av de viktigaste områdena.

Samtidigt som den digitala tryggheten, och förtroendet för landets tjänster, lider bakslag kan vi konstatera att Digitaliseringsrådet har haft exakt NOLL formella möten hittills under 2019. Det håller inte.

Att vi oroar oss för främmande makt är en sak, men det är beklämmande att vi också behöver oroa oss över hur dåligt skyddade vi är från informationsläckor i våra egna samhällstjänster.

Det är dags för Digitaliseringsrådet att kalla till möte. Och det är dags att medborgare varnas för riskerna med de tjänster som samhället fyller med information om oss och våra barn, och sedan tvingar på oss utan att behöva fråga om lov.

Läs också:

Skolplattformen i Stockholm har stora säkerhetshål • axbom.blog

Den största informationsläckan i landets historia • axbom.blog

Skolplattformen i Stockholm Stad – Marcus Österberg

Transportstyrelsens IT-upphandling – Wikipedia

1177 Vårdguiden incidenter – Wikipedia

Rådsmöten – Digitaliseringsrådet

Digital trygghet – Digitaliseringsrådet

“Är Sveriges första sanktion enligt GDPR en papperstiger?” | Dagens Juridik

Norrköping backar om digital barntillsyn | SVT Nyheter

Naiv vårdslöshet med privat information i offentliga system

Det varnas nästan dagligen om hur de globala jättarna i sociala medier är obetänksamma med vår privata information. Att demokratin hotas i sina grundvalar. Tyvärr tar det gärna fokus från läckorna som händer nära oss – där vi hela tiden tänker att vi är säkra. När samhälleliga tjänster regelbundet brister i säkerhet måste den digitala tryggheten adresseras på nationell nivå.

Nu har det än en gång visat sig hur ett offentligt system misslyckas med att skydda den information de har ansvar för att skydda. Namn, personnummer och omdömen för 140 000 barn i Stockholm har gått att nå för den som själv har varit inloggad i skolplattformen och haft grundläggande förståelse för hur information om namn och scheman hämtas.

Det här följer på en rad avslöjanden om oförsiktighet med privat information i offentliga verktyg. Och det kommer inte att vara den sista gången.

Har våra offentliga och statliga verksamheter kompetensen som krävs för att göra rätt? Eller hindrar omständigheter som upphandlingar, prispress, tidsstress och otydliga mål dem från att göra ett bra jobb – och skydda oss?

Utvecklare förstår inte koden

Det finns nämligen en historia till i den här härvan som medierna har missat. En av utvecklarna som bidragit till skolplattformen, antingen direkt eller indirekt, har skrivit en kommentar i koden, en förklaring för att hjälpa andra att göra rätt.

Min förenklade översättning av kommentaren:

Våga inte använda den här delen eftersom jag inte har en aning om var i gyttjan den passar.

Skärmdump från föräldern som gjorde avslöjandet:

Det här är uppseendeväckande och borde leda till brådskande utredningar.

Om utvecklarna – som står för ett säkert system – själva inte kan redovisa hur trådarna hänger ihop, då har vi omfattande problem. Kände de som var medvetna om kommentaren tryggheten att kunna säga ifrån, att räcka upp handen och protestera? Och om någon gjorde det, fanns det beslutsfattare som lyssnade?

Vilseledande försvar

Förtroendet grusas ytterligare när Stockholms stad går i försvarsställning för sin plattform som de själva vet är förföljd av brister. Det pratas om att man måste “ändra i programmeringskoden” för att få ut informationen. Det är fel. Om någon kunde ändra i koden skulle vi ha ett ännu större problem.

Föräldern som upptäckte säkerhetsbristen säger själv:

Reagerar på att ansvarig på staden säger att jag ‘ändrat i programmeringskoden’. Det är väldigt vilseledande. Det jag gjorde var mer som om jag skulle måla över en av siffrorna på mitt bankkort med en annan siffra och plötsligt dras pengarna på nån annans konto.

Programmering börjar bli en alltmer utbredd kompetens. Vi är hundratusentals som förstår att det inte var svårt att få tillgång till all information via plattformen. Ge gymnasieelever en checklista och de klarar av det på tio minuter.

Så hur försäkrar vi oss mot offentliga verksamheters naiva vårdslöshet? Svaret är givetvis att vi måste sluta ge dem vårt förtroende om de inte ger oss sin transparens tillbaka. De måste – på riktigt – förstå allvaret när de brister i sitt ansvar. Dessutom måste de – på riktigt – erkänna hur allvarligt det är.

Vem säkerställer medborgarnas skydd?

Dataskyddsförordningen har gett oss rätt att bli bortglömda, att avlägsna vår information från system och plattformar vi inte litar på. Rätten till skyddad information har blivit en mänsklig rättighet. Men om våra statliga system är källan till läckorna – och de systemen dessutom är obligatoriska – hur säkerställs då våra mänskliga rättigheter?

Digitaliseringsrådet, med Anders Ygeman i spetsen, ska hjälpa regeringen med strategiska analyser och rekommendationer. Digital trygghet är ett av sex delmål i digitaliseringsstrategin för Sverige, eftersom det måste “finnas goda förutsättningar för tillit och förtroende i ett digitalt samhälle”. Här är “höga krav på säkerhet” ett av de viktigaste områdena.

Samtidigt som den digitala tryggheten, och förtroendet för landets tjänster, lider bakslag kan vi konstatera att Digitaliseringsrådet har haft exakt NOLL formella möten hittills under 2019. Det håller inte.

Att vi oroar oss för främmande makt är en sak, men det är beklämmande att vi också behöver oroa oss över hur dåligt skyddade vi är från informationsläckor i våra egna samhällstjänster.

Det är dags för Digitaliseringsrådet att kalla till möte. Och det är dags att medborgare varnas för riskerna med de tjänster som samhället fyller med information om oss och våra barn, och sedan tvingar på oss utan att behöva fråga om lov.

Läs också:

Skolplattformen i Stockholm har stora säkerhetshål • axbom.blog

Den största informationsläckan i landets historia • axbom.blog

Skolplattformen i Stockholm Stad – Marcus Österberg

Transportstyrelsens IT-upphandling – Wikipedia

1177 Vårdguiden incidenter – Wikipedia

Rådsmöten – Digitaliseringsrådet

Digital trygghet – Digitaliseringsrådet

“Är Sveriges första sanktion enligt GDPR en papperstiger?” | Dagens Juridik

Norrköping backar om digital barntillsyn | SVT Nyheter