Rodd Wagner's Blog, page 8

February 18, 2015

“Human Resources,” the First Chapter of Widgets

Every word in Widgets is locked in. The final files were sent to the printer this week. The jacket design and edits are complete. After three years of research, more than a year of it spent writing and editing, and six months of it spent in pre-production work, it’s done.

Now I can share it. Yesterday we released the first chapter. It’s not among these blog posts, but can be found on the site here. I’d be delighted to hear your reaction.

Widgets is trending as the “#1 New Release in Human Resources & Personnel Management” on Amazon. Not bad for a book just going to press. Stay tuned. We’re just getting started.

If you haven’t checked your New Rules level lately, the link is at the bottom of this page. Take charge of your own “engagement.” Don’t be a widget.

February 3, 2015

No Robots Were Employed in the Writing of this Post

One of the little secrets you learn when you become a business author is that some books in the category are not written by the people whose names appear on the covers.

Either because they are “too busy” or, more likely, can’t write, some consultants hire ghostwriters who interview them and then handle the real work of putting thoughts on paper. I get the occasional inquiry from someone eager to take the problem off my hands, for a fee, of course.

In one case, an ostensible author got up to give a speech shortly after his book was released and proceeded to flummox the audience. He was not conversant with the material in his book like an author would be after wrestling with the ideas sufficiently to get them ready for publication. “Not only was it apparent he had not written the book,” said one person who saw the show, “it raised a real question as to whether he had read the book.”

This occurrence came to mind when I saw in Fast Company recently a piece on a firm that apparently has improved robotic technology to the point that a machine can write a “personal” note the recipient will mistake for the real thing. The technology is fascinating; the implications of using it are disturbing.

A still from Bond’s video showing a robot “handwriting” a note on behalf of a human somewhere.

A still from Bond’s video showing a robot “handwriting” a note on behalf of a human somewhere.“We’ve built a robot that can do anything a human can do with a pen and output it exactly,” says Matt the “roboticist” in a video for the company, New York-based Bond.

You can choose from several existing handwriting-based fonts or, for a fee, submit a handwriting sample and have it digitized and placed on file for the robot’s use.

“Brides and grooms can personalize stationery and send out thank you notes in a matter of minutes instead of days,” the video continues. “An organization can add the personal touch in a way they’ve never been able to do before.”

You can “send handwritten notes in seconds,” says Bond’s website.

Except that the notes will not be written by hand.

“We have really set out to reimagine what that would look like—how we can create a truly personal experience that lets people deliver that personal touch that is truly theirs, but let them do it from anywhere,” the CEO of Bond told the magazine. “Ultimately people are about the human experience,” said the dude who’s taking the pen out of people’s hands and attaching it to a robot. Get Orwell on the phone.

The irony was not lost on some of the people who read and commented on the Fast Company piece.

“Sincerity is everything. If you can fake that, you’ve got it made,” wrote one woman.

“This is lazy and thoughtless,” wrote another. “Nothing replaces something done by the human hand, and whether it looks ‘real’ is not the issue.”

“I thought that this was an article on The Onion,” said one reader, referring to the satirical fake newspaper.

Counterfeit handwritten notes are not the biggest issue of the day. But they illustrate a larger issue of decreasing trust as people worry that in matters large and small, from company announcements to the note from the sales guy who wants to wish you a Happy New Year, things are not what they appear to be.

If you’re cool with the fact that the person on the other end will be tricked into believing you put the time and thought into writing a personal note when you instead wrote a form letter and had the thing processed, however elegantly, then go for it. The technology is ready for you.

And if you’ve always wanted to write a book but don’t want to do the whole writing thing, email me. I know a person.

January 26, 2015

What Your New Rules Index Says About Whether You Should Quit

In September 2013, video producer Marina Shifrin announced her resignation by producing one final video at her job.

“It’s 4:30 a.m. and I am at work,” says the subtitle as the beginning footage shows her setting up the camera to face herself. Then she starts dancing.

“I work for an awesome company that produces news videos. For almost two years I’ve sacrificed my relationships, time, and energy for this job,” say the subtitles as she continues to dance.

“And my boss only cares about quantity and how many views each video gets. So I figured I’d make one of my own to focus on the content instead of worry about the views. Oh, and to let my boss know (dance break) . . .

“I quit.”

Shifrin became a YouTube hit – her video has accumulated 19 million views – and she changed jobs.

The ultimate self-defense technique for an employee who feels she is being treated like a widget is to resign and move on. That leverage was largely lost during the Great Recession. Now that the labor market is strengthening, that leverage is back. Chances are much better than they were a few years ago that you could get out if you wished.

But should you?

It would be presumptuous of me to answer the question. It’s your life. I don’t know you. Depending on where you are in your career and how many people depend on your income, quitting or staying can be a huge decision. A lot of factors are involved, many beyond the scope of my team’s studies.

What I can do, however, is give you comparative information to help you make the decision, plus a brief editorial at the end of this post based on advising many people I do know.

First, go to the link at the lower left of this page and get your New Rules index report. You, of course, know going in if you have a good job or a bad one. Once you have the report, you’ll know precisely how good or bad it is compared with the rest of the country, and what makes it so. If the self-assessment shows you’re in a better spot than 95 percent of employees in the United States, it’s unlikely you’ve been eyeing the exit sign. Count yourself extremely fortunate. If your job rates a 55, you need to decide if that’s okay. If it came in at 10, something’s got to change.

Pay particular attention to what the report says about your job on rules 2, 3, 4, and 8. Being fearful, feeling poorly compensated, suffering burnout from too much work, and not seeing much future in the company are more powerful motivators for getting out than the other rules.

In the future, we’ll build into the New Rules index report the additional comparisons I’m about to share below. But if you’re wrestling with these issues now, you need that information now. With apologies for showing more of the wiring than some people might want to see, here we go.

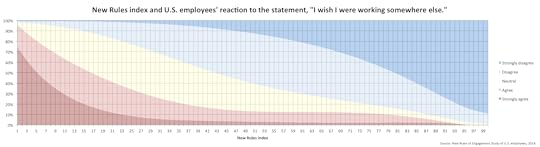

One of the statements to which you reacted on the self-assessment is, “I wish I were working somewhere else.” Your answer there was not factored into your current New Rules index. We analyze it separately.

The proportions above your New Rules index show how much others at your level are wishing they worked somewhere else.

The proportions above your New Rules index show how much others at your level are wishing they worked somewhere else.The graph above (if it displays too small, click on it) shows the proportions of U.S. employees at each percentile of the New Rules index wishing they were working elsewhere. Find your current number on the bottom scale and then follow the vertical line to see how many people in situations similar to yours are wishing they could bolt.

Not surprising, the worse the job, the more people wish they could do what Marina Shifrin did. More counterintuitive is how many people with jobs in the middle ranges (New Rules indexes between, say, 40 and 60) who nonetheless say they don’t wish they were working somewhere else. Not until people give answers putting their jobs at the 16th percentile do a majority say they wish they were somewhere else.

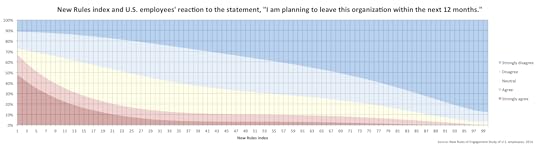

The proportions above your New Rules index in this chart show what proportions at that level are planning to quit or stay.

The proportions above your New Rules index in this chart show what proportions at that level are planning to quit or stay.What about actually preparing to pull the ripcord? The second graph shows what proportions are planning or not planning to leave their current employer at each level of the New Rules index. Here, too, you can take the number from your report, find it at the bottom of the graph, and find out what the rest of Americans at your level plan to do about it.

Notice the differences between the two charts, how many more people wish they were working somewhere else than are planning to actually go somewhere else. In the second graph, the combination of resilience and reticence is startling. Things have to get truly horrible – down to the 5th percentile – before a majority of employees say they plan on leaving in the coming year.

A New Rules index of 5 is a terrible place to be. It means that out of the 12 New Rules, at best just one of them is in a healthy range. It means your manager is neglectful, you’re fearful, you don’t like your pay, you feel overworked, your company is not a cool place to work, there’s little transparency, you find little meaning in your work, you don’t see much of a future there, you’re not getting recognition, the collaboration is poor, you get few chances to take the lead, and you have little sense of accomplishment. Going to stay with that company? About three in 10 say yes and another two in 10 are neutral.

Why does it take things getting so bad before people are willing to take action? Because there’s a mortgage to pay. Because the kids are in a good spot at school and you don’t want to relocate. Because you’re early in your career and being at your first job less than a year would make you look flaky. Because you’re a few years from retirement and the pay would be tough to replace. Because your spouse’s New Rules index is much higher and changing your job would make him or her change jobs as well. Etcetera, etcetera. As a good friend of mine said when he saw these charts, “When the costs of not having a job are high, you’re willing to suffer many smaller costs of having a bad job.”

These things are always complicated. No one who has not been caught in a rotten job can blithely advise someone else to make the switch.

Still, these data indicate that too many people – and maybe you’re one of them – tolerate work situations they should not. They don’t take control of their own careers. They get complacent. They accomplish much less than they could, doing a disservice to themselves and their employers. Treated poorly over a long enough period of time, they lose confidence. They go to YouTube and watch Marina Shifrin dance out the door, get a vicarious thrill seeing her take charge – and then they go back to work.

They let themselves become widgets.

Don’t be a widget.

Maybe you should quit. Maybe you should stay. Maybe you should create a plan to make more of the job you’ve got. But you should not be shy about making an informed decision and strategically looking out for your own best interests. That’s the one job only you can fill and you should never quit.

(If you’d like to share your story confidentially with me about your stay-or-go decision, click the contact link at the lower right corner or email me directly at Rodd@WidgetsTheBook.com.)

January 13, 2015

(Almost) Everything You Need to Know About Your Own Engagement

We’ve had a cool piece of career navigation technology locked in the lab here for a couple years while we calibrated it and shined the brass. I couldn’t be more amped up to share it with you now.

Perhaps you’ve already found your way over to the links that get you to the New Rules index and you have your report. If not, the link is at the bottom of this page.

With that report and all the secrets I’m about to spill in this post, you’ll have more information about where you are relative to others’ experiences at work, more of a guide on how to chart your course at your job, than any research team (so far as I’m aware) has shared broadly with the public.

You may have noticed that more of what a company used to take care of is now your responsibility. Few organizations offer pensions anymore; you get matching funds for a self-directed 401(k). Health care decisions and their financial consequences are increasingly on you. It’s rare that you can find one company where you will spend your whole career; you need to manage your own trajectory and your “personal brand” on LinkedIn. You can go to Glassdoor.com and give your opinion about your company any time your want.

It’s only logical that the most important “employee engagement” survey be one that you take when you want and that gives a confidential report directly to you.

With apologies that this will be a longer post that usual, I’ll take you through the wiring behind the technology. This will get ever-so-slightly geeky, nothing you can’t handle.

We conducted two waves of research among a representative sample of employees in the United States. They answered about a hundred questions. Twelve key aspects of a job – what we ended up calling the New Rules – emerged from our analyses. They’re what you need to be motivated to stay and deliver your best for your employer. They’re what you deserve if you’re delivering you best.

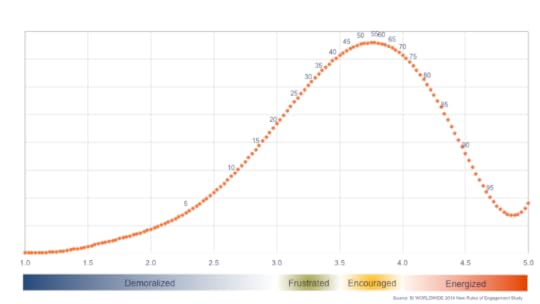

Each rule is measured by three questions, which makes 36 core statement. We analyzed what proportion of people in the representative sample ended up at each level and got this curve.

It’s like a pile of snow the wind has pushed to the right, with a small accumulation pushed against a wall on the far right. (Forgive the snow drift metaphor; I live in Minnesota.)

The report starts with your New Rules index, which comes from calculating where you are on the curve above at the time your take the assessment. It’s a percentile. If your index comes back at 79, you’re currently in a better spot than 79 percent of employees in the U.S. and in a worse spot than 21 percent.

We labeled ranges along the snow drift. We did so a little reluctantly, as we didn’t want to replicate the issues that happen when people get dropped into a bucket and get blamed for it. Four safeguards keep that from happening:

We always supply the New Rules index, which is more precise.

We made sure the names and descriptions of the lower ranges were not accusatory. If you’re currently in the demoralized or frustrated ranges, we assume you didn’t choose to be there and, while you are there, you are not “more or less out to damage” the company.

We don’t assume you’re stuck in one spot. In fact, you can return as often as you like. Your report reflects your current situation, not who you are as an employee.

Unless you told them, no one at your company even knows you took the assessment. (We have additional safeguards if we’re doing this process for a company.)

Your New Rules index is an overall measure. It’s just the start.

One of 180 descriptions that populate a New Rules report depending on your responses. This is the feedback on Rule 7 for those who have high index numbers and answer “strongly agree” to all the meaning statements.

One of 180 descriptions that populate a New Rules report depending on your responses. This is the feedback on Rule 7 for those who have high index numbers and answer “strongly agree” to all the meaning statements.Your report also includes where you are now on each of the 12 rules. That index of 79 might have come by virtue of generous pay and modest company transparency, or vice versa, just to mention two of the 12 rules. Multiply the scenarios across 12 rules with five levels within each rule and there are more than 244 million possible reports at least slightly different from all the rest. (When I saw that number, I had to double-check the math. It’s right.)

If you get your New Rules index when things are bad and then return when things are good, you’ll notice a difference in the tone of the reports. If your number is high, we figure it’s okay to joke around or make a bad pun. If your index is low, you almost certainly don’t think it’s funny, and neither do we.

At the lower right of the report page is a spot where you can generate a PDF for your reference. Many people find it useful to share the report with a friend or family member whose advice they trust. But that’s your call.

The New Rules index is empirically sound and grounded in our team’s extensive research advising people on how to make the most of their careers. It gives you immediate information and advice, because no one is going to take responsibility for your situation more than you will. Use it as you see fit.

If you like where this is headed, I would greatly appreciate you sharing it with your network.

It helps keep my meaning level high.

(If you don’t have your current New Rules index, you can get it through the link at the lower left of the blog page.)

January 9, 2015

“Get Me Out of This Bucket!”

There’s a trap waiting behind traditional employee engagement surveys.

The moment the worker hits “Submit,” she’s destined to be dropped into a bucket. She’ll be stereotyped. Her motivations will be assumed. She may be vilified. If she lands in the wrong bucket, she could be targeted for firing.

All because she answered honestly to the survey, and the people behind the survey or at her company misused the information.

It’s time to stop pouring people into buckets. If the practice continues, more and more employees will lie on the surveys, as they should in those situations, and most employee surveys will become a waste of time and money.

Many consultancies bucket the people who take their surveys. (One actually refers to people in one of its compartments as “hamsters.”) The primary offender, because of its prominence and imprecision, is Gallup. Gallup hit the market hard in the late 1990s with its Q12 survey, making hundreds of millions in revenue and inspiring a number of copycats that picked up some of its bad habits.

Gallup drops employees into three buckets: “engaged,” “not engaged,” and “actively disengaged.” Only three in 10 workers are in the shiny best bucket, we’re told. Roughly half fall into the big bucket of “not engaged.” And about two in 10 are in the contemptible container of “actively disengaged.”

The worst thing about the buckets is what some consultancies say about the people who on the day of the survey gave answers that got them dropped into a middle or left-most bucket. Bucket language got us to a point where we talk about “disengagement” as a character flaw. It led to talking as if there were three kinds of employees, not a wide range of situations, largely external to the worker, which create a wide range in motivation and commitment.

Here’s how Gallup describes its middle bucket:

Not engaged workers can be difficult to spot: They are not hostile or disruptive. They show up and kill time with little or no concern about customers, productivity, profitability, waste, safety, mission and purpose of the teams, or developing customers. They are thinking about lunch or their next break. They are essentially “checked out.”

That description is poorly written. It assigns the blame to the employee, not to the situation in which she finds herself. And, based on in-depth studies my colleagues and I conducted for Widgets, the description is flat-out wrong. People in the middle of the range display high levels of responsibility and maturity.

It gets worse. This is Gallup’s allegation against the two in 10 workers who they classify as “actively disengaged.”

Actively disengaged employees are more or less out to damage their company. They monopolize managers’ time; have more on-the-job accidents; account for more quality defects; contribute to “shrinkage,” as theft is called; are sicker; miss more days; and quit at a higher rate than engaged employees do. Whatever the engaged do — such as solving problems, innovating, and creating new customers — the actively disengaged try to undo.

It is remarkable that any business gets done if 20 percent of the workforce are borderline criminals. But the work gets done because this definition, too, is false.

Of course some people are laggards. Some try to work as little as possible. A few will steal. Some will heave fragile customer packages over fences. We’ve all seen the YouTube videos. But just as the company would rush to mention that misbehaving employee is not representative of their brand, the bulk of the frustrated or demoralized employees, if they could speak up, would rush to emphasize they are absolutely not trying to “undo” what their better-managed colleagues are getting done.

Nobody wants the kind of job that reduces him or her to the point of not giving a damn. No one wants to be on that end of the scale. And for the vast majority of people most frustrated by their jobs, the answer is not to blame them for their so-called “disengagement.”

The bucketing of employees leads to several additional problems for leaders, managers, and the people they supervise.

It grossly simplifies the range of engagement. Engagement runs along a wide continuum, something of a snowdrift blown to the right. On a given day, an employee is most likely to find herself somewhere in the well-populated middle of the curve, but she could be anywhere. Every parent and high school student knows this. Standardized tests have long reported the percentile score of the student: “Tommy scored at the 79th percentile in math and at the 72nd in reading.” If schools started bucketing kids into just three categories – passing, not passing, and actively failing – there would be pitchforks and torches at the next board of education meeting. Yet, for some reason, we’ve put up with it for employees.

Based on only 12 five-point-scale questions, Gallup’s curve can only have 49 distinct points. How many are at each point and which scores put you in one bucket or another are closely guarded secrets. It’s therefore impossible for all the journalists and engagement commentators to know the details beneath the generalities Gallup supplies. They have to take Gallup’s word for it. In our age of transparency, telling people just enough to mess with their heads is a disservice to the working public and their employers.

No one tells the employee which bucket she’s in. Perhaps she can guess, but it would be just that – a guess. If it did tell her where she landed, chances are the survey would not say to her face what some advisors say about her and her bucket buddies behind her back.

The percentages in each bucket are not really meaningful. When you slice up something close to a bell curve, tiny movements of the knife to the left or right dramatically change the percentages in the two slices. This is Statistics 101. Right next to the 30 percent who are supposedly engaged are another five or 10 percent who are closer to the border between the two groups than they are to the midpoint of their assigned group.

Bucketing, combined with infrequent measurement, masks the dynamic nature of people’s attitudes about their work. People have good days and bad ones. Some get praised by their managers right before the survey; others have managers who yell at them. People get new bosses. New policies are announced, for good and bad. Their coworkers come and go. Projects dry up or swamp an employee’s personal life. Their engagement goes up and down by small degrees or huge swings in response to the conditions around them. But in the records, until the next survey, people are trapped in the bucket to which they were assigned at survey time.

Described precisely and accurately, there is nothing wrong with bracketing some ranges within the larger statistical distribution of responses employees give to a survey. We do it, as I describe here. But ranges become buckets when a worker is stuck with that label, blamed for being there, and deprived of knowing how she is being categorized.

Of course, no reputable survey company tells anyone at a client organization into which bucket a given employee falls. Her responses are technically “confidential.” But when some team engagement reports show the results for as few as four or five people, it leads to a lot of guessing and, sometimes, hunting down of the suspected “disengaged” as leaders try to ferret out those people who are ostensibly “more or less out to damage the company.” Their time would be better spent figuring out why their employees would grow frustrated or demoralized.

It’s well past time we freed people from the buckets.

January 7, 2015

Quiet Praise to Keep Employees Captive?

There are a lot of dumb ideas about employee engagement floating around out there. Most are not worth mentioning. This one is just dumb enough I feel compelled to share it. I’ll leave out which company cooked it up so they can destroy whatever copies they have left.

Here’s the passage that caught my attention:

Let’s follow the logic:

“I’d like to recognize you for your great work, but I’m just going to do it internally, because I don’t want someone finding out how good you are and coming to you with what might be a better job. After all, it’s not really about what you want; it’s about what I want from you.”

One of the best gauges of whether an engagement strategy is sound is whether you could share it with a straight face with your employees. Anyone who thought the document excerpted here was part of his manager’s playbook would get out as soon as she could. As she should.

10 Reasons Not to Do an Employee Survey

In November, I awakened one morning and started tweeting five top reasons not to do an employee survey. Before I’d finished my orange juice, the list grew to 10. Each could come back to bite you.

It’s not a bad checklist to decide whether an employee survey is worth the investment or whether it’s best to work on other areas first. If more than six or seven of these are currently true for your company, save your money or set up your survey differently.

10. Your survey provider’s executive briefing looks suspiciously like the last client’s presentation.

9. Your firm’s results will go into the survey company’s “database” to help advise your competition.

8. Your execs and managers will use the info to hunt down the so-called “disengaged” and fire them.

7. The survey will be open for two weeks, then closed for 11-and-a-half months.

6. After answering super-sensitive questions, the employee gets no personal feedback.

5. You’ll tell them it’s confidential, then aggregate so few respondents in a report that it’s not.

4. Your employees are afraid to tell the truth.

3. You’re not going to do anything with the results that will mean something to the employees.

2. The survey questions were written when your Millennial employees were in kindergarten.

1. Deep down, your executives don’t care.

January 6, 2015

Driving Home the Wrong Point

“Your people are not your greatest asset. They’re not yours, and they’re not assets. Assets are property. You don’t own your people.”

I had already written these opening lines months earlier in the manuscript for Widgets. I was driving through Illinois last year when I saw ahead of me what’s in the photo above.

“Our most valuable resource sits 63 feet ahead.”

What’s wrong about this declaration is not what the people who wrote it intended. They probably meant it either warmly or, at worst, as a marketing gimmick. It’s that they failed to appreciate they were using terms of ownership to refer to people.

A resource or asset of a business is, by the definition in the accounting textbooks, owned by the company. The enterprise can do with it pretty much whatever it wishes. Lumber, coal, patents, buildings, water rights, trademarks, cattle, or that 18-wheeler being driven through the Midwest – all assets. All to be used, sold, left sitting idle, or traded in as best serves the interests of the company without any say in how they are treated, because they are property.

This would be nothing more than my personal hang-up were it not for so many other ways that some organizations today treat their employees like – their term – “human resources.”

At a time when most organizations are less likely to take a long-term interest in the people who work there, too many are assuming they essentially own all of a person’s time, evenings and weekends included. They are reducing people to electronic bits and bytes in their “eHR” systems. They are assuming they own the employee’s “wellbeing” and private health information, even as they boost others off the company insurance. They are far more willing to send their so-called “greatest resources” packing if the next couple quarters threaten to be below analysts’ expectations.

I used this photo in a presentation after my friend Dr. Brad Shuck and I spoke to a business group last spring in Scottsdale, Arizona. On his way back, he spotted this truck, which took the “greatest resource” thing yet another step too far with what was painted on the side.

This raises the ridiculousness to Dilbertian proportions.

For the best managed of these drivers, it’s probably no big deal. They might even get a warm feeling from it. But for the most frustrated drivers – those who haven’t seen their families for weeks, who are being given poor routes by dispatch, or whose pay isn’t what they thought it would be – coming out of the truck stop to climb back in front of the company’s clumsy slogan has to take some of the air out of their tires.

In any case, it’s not right. No employee is a company’s resource or asset. He’s a person, plain and simple, not the punctuation on a big rolling company billboard.

(If you come across other examples of companies pointing at their employees and calling them assets, please send them along.)