Rodd Wagner's Blog, page 2

February 27, 2017

Happy Employees Equal Happy Customers? Well, Yes, But It’s Complicated

Within the chart above is a counter-intuitive truth employee engagement consultants either don’t know or don’t talk about.

Unhappy employees often give great customer service. In fact, the majority of the unhappiest employees say they’ll go to great lengths for their companies’ customers. So do happy employees = happy customers? Well, yes, but the connections are more complicated than commonly assumed.

You can read the particulars in my latest column for Forbes.

February 14, 2017

Best Friends At Work? With Or Without Benefits, It’s None Of The Company’s Business

It should not be surprising that people find many of their friends, their best friends, their girlfriends, their boyfriends, and even their spouses at work. Take such social creatures and put them in the same building for most of their waking hours and it’s bound to happen.

What’s surprising is how much employee engagement initiatives have presumed to ask about these very personal relationships in order to leverage them for profit. It’s intrusive, if not flat-out creepy.

My latest column for Forbes shares the latest stats and studies on a practice that needs to end.

January 30, 2017

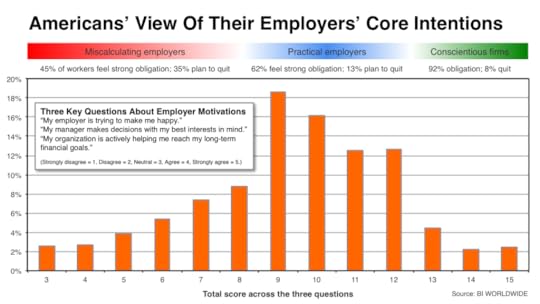

The Most Important Question About Your Employer Goes To Its Heart

Your company does certain things for you. Have you ever wondered why?

It pays you well or poorly or somewhere between. Why not higher? Why not lower?

The medical insurance probably could be better or could be worse. Why is it at that level?

You’re given a certain amount of paid time off. Why not more or less?

Perhaps your company throws the occasional party. Why go to the trouble?

The answer to each of these hints at the answer to the ultimate question: How does your company feel about you and the other people who work there?

It’s a crucial issue, one that goes to the heart of the unwritten social contract. The answer determines your best strategy for how much commitment you should give in return. Organizations often deliver similar perks and benefits for different reasons. A mismatch between your company’s intentions and yours can hurt your career.

In my latest column for Forbes, I share three quick questions that allow you to compare your perception of your employer’s motivations against the answers of the rest of the United States, plus some advice on what it means for your strategy on the job.

January 23, 2017

An ‘Employee Value Proposition’ Mindset Just Might Fix Employee Engagement

What began as a great idea – methodically attending to what people need to be most effective on the job – has become at many enterprises a hodgepodge of perfunctory surveys, consultant malpractice, and fear-mongering.

What can save it? It will take a lot. The effects of a decade or more of bad strategy won’t easily dissipate.

But there is a concept reemerging that just might get things realigned. “Employee value proposition” just might get companies thinking straight again about their relationship with their employees.

My latest column for Forbes makes the case.

December 31, 2016

We Are Leaving Too Many People Behind

The unemployment numbers – at least the ones most commonly cited – looked good in the closing weeks of 2016. People are starting to use the word “strong” to describe the economy.

But just beneath the surface are statistics indicating we’re leaving behind an increasingly proportion of the population. My latest column for Forbes is published in the hope we don’t blast through the self-checkout lane so fast that we forget that machine used to be someone’s job.

November 22, 2016

‘Undead’ Circuit City Won’t Rise If It Forgets What Killed It

Remember Circuit City?

It was featured in the bestselling book Good to Great as one of 11 exemplary organizations that showed “why some companies make the leap and others don’t.”

And then it didn’t.

It died in 2009, a victim of the recession, its own knuckleheadedness, and Best Buy’s smarter strategy and management. Well, most of it died. The brand is still floating out there in cyberspace, undead, part of what one industry website calls “zombie retail.”

Its CEO (yes, it has one) says the company is coming back in the form of stores, kiosks, and a website where people could actually buy something. But will it have learned the management lessons of its namesake predecessor?

Those “Good to Great to (Almost) Gone” lessons are at the heart of my latest column for Forbes.

November 21, 2016

The Case for Happiness at Work Is Self-Evident; But There’s Also Evidence

It is at once the silliest and most important debate going on in the field of human resources.

Should business leaders seek to make their employees happy?

Of course! Why not? Don’t happy employees make for happy customers? Is it not – to borrow a term from the Declaration of Independence – “self-evident?”

Yet some prominent figures argue employee happiness is a foolish goal. “The idea of trying to make people happy at work is terrible,” Gallup CEO Jim Clifton told Fast Company. His nephew, StrengthsFinder 2.0 author Tom Rath, argues “the pursuit of happiness might do us more harm than good. . . . Despite Thomas Jefferson including it in the Declaration of Independence, the ‘pursuit of happiness’ is a shortsighted aim.”

Equating employee engagement and happiness “makes my ears ring and my mouth twitch,” wrote my fellow Forbes contributor Maren Hogan. “There’s no proof that happy employees will do anything great for your company,” she asserted. Writing for the Harvard Business Review, Red Hat CEO Jim Whitehurst asserted, “Engagement isn’t about being happy. Happy people may or may not be engaged in the business.”

The most important reason to make your employees happy is simply because they are your employees, people whose lives are affected for good or bad depending on the quality of leadership and managing where they work. This is, admittedly, a moral argument, a question of conscience rather than profitability. But for a question this serious, we ought not be afraid to begin by interrogating our values.

Why do health care organizations concentrate on the quality of their patient care? Because people’s lives are affected. Why do businesses agonize over profits and share price? Because they have a “fiduciary responsibility” to their shareholders. A company’s responsibility to its employees is no less weighty. Business leaders should not casually dismiss one of the central goals of their employees’ lives.

But even when they do – even if the sole justification for making employees happy were the return on investment – it would still be imperative. The evidence is clear that employees whose companies make them happier reciprocate by investing themselves in the success of the business. Contrary to Hogan’s assertion, there is plenty of “proof” that happy employees do great things for their companies.

In BI WORLDWIDE’s research, happiness is strongly associated with hard work. Nine of 10 happy employees agree they “feel an obligation to work as hard as I can for my organization.” Among unhappy employees, the proportion drops to only six out of 10. Ninety-three percent of happy employees agree they are “willing to work especially hard for my organization’s customers.” Among unhappy employees, the figure drops to 69 percent. Similar differences appear on other predictors of an employee’s best work.

The portion of retention influenced by an employer – factors other than, for example, a spouse being offered a job in another market or wanting to return to college – is largely composed of the worker’s happiness there. Among those who are unhappy at work, 54 percent plan to leave in the next 12 months. It’s only 23 percent among those who are happy at their current jobs.

“Someone can be happy at work, but not ‘engaged,’” wrote engagement author Kevin Kruse. “They might be happy because they are lazy and it’s a job with not much to do. They might be happy talking to all their work-friends and enjoying the free cafeteria food. They might be happy to have a free company car. They might just be a happy person. But just because they’re happy doesn’t mean they are working hard on behalf of the company. They can be happy and unproductive.”

Hogan, Whitehurst, and Clifton make similar arguments. Clifton analogizes employees to bears in a national park whose natural instincts will be messed up if they are fed. “Don’t feed the bears,” he cautions.

Beyond the obvious fact that people are not bears, the evidence clearly refutes the anti-happiness crowd. While technically people could be happy but not engaged, in practice, they aren’t. The overlap between those who are happy and those who are engaged is so large that there simply are no appreciable numbers of people who are happy at work and not engaged, or, conversely, engaged and not happy.

Statistically, it is nearly impossible to be happy and not engaged. Our research indicates they are two sides of the same bargain, that what businesses call engagement (customer focus, retention, collaboration, creativity) they get largely in return for the happiness they create among their employees.

Inherent in the arguments against happiness at work is the discredited Theory X of employee motivation – that given a choice, people will work as little as possible and goof off as much as they can. Also buried within those arguments is a misconception about happiness itself – that it is solely hedonistic. This was not what Jefferson meant when he wrote the “pursuit of happiness” into the Declaration of Independence.

“Scholars have long noted that for Aristotle and the Greeks, as well as for Jefferson and the Americans, happiness was not about yellow smiley faces, self-esteem or even feelings,” wrote Jon Meacham, author of Thomas Jefferson: The Art of Power. “According to historians of happiness and of Aristotle, it was an ultimate good, worth seeking for its own sake. Given the Aristotelian insight that man is a social creature whose life finds meaning in his relation to other human beings, Jeffersonian eudaimonia – the Greek word for happiness – evokes virtue, good conduct and generous citizenship.”

This is the type of happiness that is reflected when BI WORLDWIDE asks an employee, “How Happy Are You at Work?” In fact, that question proved to be so powerful that we made it the first question in the self-assessment we built into workhappier.com. We invented a novel means of capturing it with a face whose smile or frown changes as the employee moves an adjacent 100-point-scale slider. Our analyses show it is as strong or stronger than any “employee net promoter score” measure, such as asking if an employee would recommend the firm as a good place to work.

There is, however, one massive pitfall that brings us back to the morality of the issue. Leaders persuaded of the business case for making employees happy but who are interested in doing so only for the money are at risk of turning the initiative into nothing more than a management technique, if not an outright trick.

“Those who have exploited it best are those with an interest in social control, very often for private profit,” wrote William Davies in The Happiness Industry: How the Government and Big Business Sold Us Well-Being. Happiness “is represented as an input to certain strategies and projects, a resource to be drawn upon, which will yield more money in return.”

BI WORLDWIDE’s ongoing research is now focused, among other issues, on the question of what happens when an employee gets wise to such a maneuver. She may balk: “You mean the only reason you care about my happiness is to make yourself more money?” Or she may brush it aside: “I don’t care why you’re trying to make me happy as long as it means more attention to making this a better place to work.”

These are, at least, legitimate questions rather than the silly assertions by the anti-happiness crowd, citing no evidence, that sparked the whole debate. In this way, the debate is constructive. For that, and for sparking a healthy reexamination of the meaningful reasons why someone would get into the business of managing people, we can be grateful, and maybe even happy.

(Originally published on HR.com. To test your happiness at work, take the free job assessment at WorkHappier.com .)

November 17, 2016

Would You Have Socks With Your Company?

Most firms create some kind of company-branded apparel they hope the employees will wear with pride. But people are selective about the messages they put on their bodies. A new study by BI WORLDWIDE identified the reasons employees will or will not wear company clothing. Those reasons go to the heart of the relationship between people and the places where they work. My latest column for Forbes has the details.

October 31, 2016

‘More Bananas! Oranges Are Awkward’

After an otherwise great keynote a couple years ago, the comment in the headline above was the only negative remark. It’s become something of an inside joke around here: Do all the research, analyses, insight, and graphic design for a great briefing, but never forget the whole thing can fall flat without the right staging on site, especially the food.

There’s a larger truth of behavioral economics in the “More bananas!” comment. In my latest Forbes column, I summarize a few of the more interesting experiments on how food, its temperature, or hunger have a strong effect on how we interact with people around us.

October 14, 2016

What To Do If Your Company Has A Chief Predatory Officer

I prefer to write about happiness at work. But most of the questions my colleagues and I ask employees would sound ridiculous if they were to be posed to a woman being preyed upon by an executive of the company.

When most serious (in other words, not just the creepy guy you can avoid, but the lurking manager you can’t), harassment makes the normal aspects of workplace happiness irrelevant, the employee engagement version of asking, “But how did you like the play, Mrs. Lincoln?”

“How’s your pay?” “How’s your work/life balance?” “Do you feel connected to the mission of the company?” “Is your company a cool place to work?” All great questions under everyday circumstances, but try asking them to a woman who’s the target of a Tic-Tac-popping Top Dog whose greeting is, to quote Trump, “just start kissing.”

“It is impossible to be focused and engaged at work when you feel – perceived threat or real threat, it does not matter – that a leader is after you,” said University of Louisville Associate Professor Brad Shuck. “The focus is on survival, not engagement.”

My latest Forbes column describes some of the recent prominent examples of CEOs who created truly creepy environments and rounds up some solid advice for anyone subjected to such treatment.