Susan Bernofsky's Blog

December 29, 2024

The View from Up Here

It’s been a year, or rather several years in fact. From the moment I first began working on my new translation of Thomas Mann’s epochal The Magic Mountain in the fall of 2019, a pandemic has come and (sort of) gone, my father died, I published a biography of Robert Walser and a translation of a Yoko Tawada novel that’s (not so) secretly a love letter to Paul Celan, taught in Germany, came home again, and here we are. It’s always such a thrill to be able to type the words ‘The End’ at the end of a book one is translating; this is my first time doing so (or, more precisely in this case, Finis operis) for a novel well over 1000 pages long – and it will definitely be the last. While the pleasures and possibilities of long books certainly transcend what can be achieved in a a shorter span, I am a sprinter at heart, and books this length are the domain of ultramarathoners. I heaved many a sigh while working on this novel. At the same time, I wouldn’t wish it any shorter; truly, not by a single page. The Magic Mountain is a book about time, and its mountainous expanse is an absolutely crucial feature. The reader needs to feel the weeks, months, and years slipping past in an ever more formless Einerlei (sameness). While the novel has its moments of high drama, for the most part its pace is one of methodical rumination, examination, observation. Working on it has taught me patience. I am also filled with admiration for the book’s great artistry and beauty, and it has been the honor of a lifetime to be entrusted with the task of rendering its magnificent sentences into English. I hope that the reader of my translation (which I expect to be published, by W.W. Norton, in early 2026) will be able to feel and glimpse the power that makes Mann’s novel one of the greatest of all time.

The post The View from Up Here appeared first on TRANSLATIONiSTA.

September 12, 2022

Notes from the Magic Mountain, 9/12/22

The first documented use of the word “glitch,” in 1962, is attributed to John Glenn, and in its figurative sense—meaning “hitch, snag, malfunction”—it’s marked in the Oxford English Dictionary as “astronauts’ slang,” etymology unknown. Who knew these explorers of the universe also made such important contributions to the development of the English language! I was looking into the history of glitches because it occurred to me that Hans Castorp might remark, “I assume there were some glitches in my French” when he’s chatting with Dr. Behrens about an earlier conversation with Madame Chauchat conducted almost entirely in French. But now the line looks a bit too outer-spacey to my taste. Even though the OED is tight-lipped on the question of where the word came from, I’m thinking it must have been inspired by the synonymous “hitch” (first documented usage in this sense 1748). In case you’re wondering, “hiccup” didn’t start referring to a hitch or glitch until 1965. Perhaps a glitch is what happens when you glide into a hitch?

The first documented use of the word “glitch,” in 1962, is attributed to John Glenn, and in its figurative sense—meaning “hitch, snag, malfunction”—it’s marked in the Oxford English Dictionary as “astronauts’ slang,” etymology unknown. Who knew these explorers of the universe also made such important contributions to the development of the English language! I was looking into the history of glitches because it occurred to me that Hans Castorp might remark, “I assume there were some glitches in my French” when he’s chatting with Dr. Behrens about an earlier conversation with Madame Chauchat conducted almost entirely in French. But now the line looks a bit too outer-spacey to my taste. Even though the OED is tight-lipped on the question of where the word came from, I’m thinking it must have been inspired by the synonymous “hitch” (first documented usage in this sense 1748). In case you’re wondering, “hiccup” didn’t start referring to a hitch or glitch until 1965. Perhaps a glitch is what happens when you glide into a hitch?

“Glide” is a word I initially considered to render the German verb “schleichen” – the one Mann repeatedly uses to describe the way Mme. Chauchat crosses the dining room of the sanatorium after each of her door-slamming entrances at mealtime. The German verb “schleichen” implies several things at once: a stealthy, quiet, slow, smooth forward motion. It’s the catlike way the various incarnations of Irma Vep creep down a corridor. (Also: Chauchat!) I see Castorp’s view of La Chauchat’s way of being (and moving) as simultaneously admiring and disapproving. So “glide” can’t do enough of the work “schleichen” is doing; “glide” is too elegant, too positively freighted—“gliding” describes the movement of a swan or a cartoon queen. So for now, I’m experimenting with other options such as the polyvalent “slink” (= “To move, go, walk, etc. in a quiet, stealthy, or sneaking manner,” OED), “steal” (= “To go or come secretly or stealthily; to walk or creep softly so as to avoid observation,” OED), and “skulk” (= “To move in a stealthy or sneaking fashion, so as to escape notice,” OED).

As for the state of Hans Castorp’s French, I have astonishingly (this sort of thing is rare) discovered the model phrase “mit dem Französischen hapert es noch bei ihm” in my favorite 100+ year old German-English dictionary (= “his French is still very imperfect”), which is quite close to Castorp’s admission, “Ich nehme an, daß es mit meinem Französisch etwas gehapert hat.” Well, given that schoolboy Castorp was in the habit of drinking a medicinal beer before heading off to class each morning, it’s no surprise that his French has its shortcomings. Speaking of French, for those of you wondering just how much of that language Mann uses in his novel—above all in that long Carnival-night flirtation between Castorp and Chauchat, but occasionally also when other characters are showing off their savoir-vivre—I’ve now done enough math to report that it adds up to well under 1% of the novel. So: still a pretty German book all in all.

The post Notes from the Magic Mountain, 9/12/22 appeared first on TRANSLATIONiSTA.

August 22, 2022

Notes from the Magic Mountain, 8/22/22

As I work on my translation of Thomas Mann’s monumental novel The Magic Mountain, I learn so many interesting things. I’ve decided to start periodically sharing my thoughts on translation questions that pop up as I work. Here are a few:

The carnival scene in MM is a crucial point of heightened tension—the customs of carnival allow Hans Castorp to approach Clawdia Chauchat and address her informally, using the familiar pronoun “du,” which works similarly to “tu” in French. Indeed, most of their conversation takes place in French, a language she’s more comfortable in than German. This language, which Hans Castorp speaks imperfectly, provides another “mask” he can hide behind as he declares his love to her. “Carnival” is a tricky word here, since its associations in English are more with places where Romance languages are spoken (such as Italy and Brazil). Those who’ve been to Germany (above all Cologne) in February are probably acquainted with “Fasching,” the German word for the carnival celebrated in the days leading up to Shrove Tuesday, the day before Ash Wednesday. It’s pointed out in the novel by resident scholar Settembrini that the word “carnival” comes from “carne” + “vale” = “farewell, meat!”; because meat is something one might be giving up for Lent. But Mann doesn’t use the word “Fasching” in the book as often as he uses the variant “Fastnacht” (= the eve of the fast) which is what Carnival is usually called in German-speaking Switzerland. So I decided to stick to “Carnival” rather than getting into the whole Fasching/Fastnacht distinction, which I decided wouldn’t be worth the confusion it was likely to create for the reader in English. A confusion created for me, on the other hand, was Mann’s use of the word “Trikot” to describe part of the carnival costume worn by a fellow running around in a cape: “A Greek from the Bad Russian table with comely legs was strutting around in [Trikotunterhosen] of [insert color] along with a little cloak, paper ruff, and sword cane, representing a Spanish grandee or fairy-tale princeling.” Now, “Unterhosen” are underpants, and “Trikot” just means “knit” and refers to fabrics produced through a knitting rather than a weaving process. But just as “tricot” and “jersey” are used in English to refer to garments made of cloth produced in this manner, German calls various things Trikot as well. So I wondered about these “tricot underpants”—were they long? short? In a later scene, however, this same fellow was flashing his “Trikotbeine” (tricot legs), making it clear that the garment in question was indeed long underwear. I even found a German WWI-re-enactor online (this may well be part of a politically unsavory project) describing the exact structure of these long johns. Alas the color of the skivvies is ambiguous as well: it’s “lila,” a color I’ve heard Germans use to refer to everything from pale lilac flowers to things of a shade that I, a person from New Orleans of a certain generation, will eternally refer to as “K&B purple.” It’s the color name used in the German translation of Alice Walker’s novel The Color Purple. But my turn-of-the-20th-century Muret-Sanders dictionary specifies “lilac, pale violet,” so I’ve decided to see these underpants as paler than the classic dark purple associated with New-Orleans style Mardi Gras. In my Magic Mountain, this fellow’s legs are lilac.

The carnival scene in MM is a crucial point of heightened tension—the customs of carnival allow Hans Castorp to approach Clawdia Chauchat and address her informally, using the familiar pronoun “du,” which works similarly to “tu” in French. Indeed, most of their conversation takes place in French, a language she’s more comfortable in than German. This language, which Hans Castorp speaks imperfectly, provides another “mask” he can hide behind as he declares his love to her. “Carnival” is a tricky word here, since its associations in English are more with places where Romance languages are spoken (such as Italy and Brazil). Those who’ve been to Germany (above all Cologne) in February are probably acquainted with “Fasching,” the German word for the carnival celebrated in the days leading up to Shrove Tuesday, the day before Ash Wednesday. It’s pointed out in the novel by resident scholar Settembrini that the word “carnival” comes from “carne” + “vale” = “farewell, meat!”; because meat is something one might be giving up for Lent. But Mann doesn’t use the word “Fasching” in the book as often as he uses the variant “Fastnacht” (= the eve of the fast) which is what Carnival is usually called in German-speaking Switzerland. So I decided to stick to “Carnival” rather than getting into the whole Fasching/Fastnacht distinction, which I decided wouldn’t be worth the confusion it was likely to create for the reader in English. A confusion created for me, on the other hand, was Mann’s use of the word “Trikot” to describe part of the carnival costume worn by a fellow running around in a cape: “A Greek from the Bad Russian table with comely legs was strutting around in [Trikotunterhosen] of [insert color] along with a little cloak, paper ruff, and sword cane, representing a Spanish grandee or fairy-tale princeling.” Now, “Unterhosen” are underpants, and “Trikot” just means “knit” and refers to fabrics produced through a knitting rather than a weaving process. But just as “tricot” and “jersey” are used in English to refer to garments made of cloth produced in this manner, German calls various things Trikot as well. So I wondered about these “tricot underpants”—were they long? short? In a later scene, however, this same fellow was flashing his “Trikotbeine” (tricot legs), making it clear that the garment in question was indeed long underwear. I even found a German WWI-re-enactor online (this may well be part of a politically unsavory project) describing the exact structure of these long johns. Alas the color of the skivvies is ambiguous as well: it’s “lila,” a color I’ve heard Germans use to refer to everything from pale lilac flowers to things of a shade that I, a person from New Orleans of a certain generation, will eternally refer to as “K&B purple.” It’s the color name used in the German translation of Alice Walker’s novel The Color Purple. But my turn-of-the-20th-century Muret-Sanders dictionary specifies “lilac, pale violet,” so I’ve decided to see these underpants as paler than the classic dark purple associated with New-Orleans style Mardi Gras. In my Magic Mountain, this fellow’s legs are lilac.

The post Notes from the Magic Mountain, 8/22/22 appeared first on TRANSLATIONiSTA.

March 30, 2022

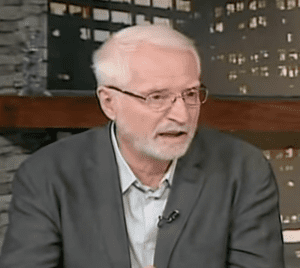

Remembering Humphrey Davies (1947 – 2021)

Translator and Scholar Humphrey Davies left us this past winter. I never got to meet him, but I’ll never forget what a pleasure it was to read his gorgeous translation of Elias Khoury’s The Gate of the Sun. He was a true artist.

Translator and Scholar Humphrey Davies left us this past winter. I never got to meet him, but I’ll never forget what a pleasure it was to read his gorgeous translation of Elias Khoury’s The Gate of the Sun. He was a true artist.

M. Lynx Qualey has published moving words of tribute to him on the ArabLit website, from which the image on this page was borrowed. Please let her tell you about how Davies found his way to translation and became one of our most important translators of Arabic literature.

You’ll also find tributes to him posted by a number of colleagues on a still-growing memorial page on the ArabLit Quarterly website.

The post Remembering Humphrey Davies (1947 – 2021) appeared first on TRANSLATIONiSTA.

February 18, 2022

Remembering Lee Fahnestock (1928 – 2022)

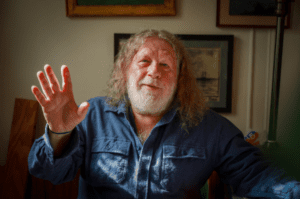

Lee Fahnestock on Thanksgiving 2012 in NYC ©Miguel Cervantes-Cervantes

Words of tribute by Norman MacAfee:

Lee Fahnestock and I met at the PEN American Center in New York in late 1983, during a meeting of the Translation Committee. We soon became close friends and remained so all these years.

Lee’s first book, The Making of the Pré by Francis Ponge, her translation of Ponge, had appeared in 1979, from Indiana University Press, followed by her translations of Paul Fournel’s Little Girls Breathe the Same Air As We Do; Françoise Sagan’s The Painted Lady, and (using the pseudonym M. L Linden) Elvire Murail’s Stairway C. In 1982, Random House had published my first book, my translations made with Luciano Martinengo of major poems by Pier Paolo Pasolini. Jonathan Galassi then at Random House, was the publisher. John Calder published it in London in 1984, and in 1996, Jonathan now at Farrar Straus & Giroux published it again, an edition still in print. I had wanted to translate Pasolini because I loved his films, and the poems are stupendous. But I was writing a lot of my own work—poems, an opera, a novel—and rejected several offers to translate more books.

Then in late December 1985, Lee phoned me. The editor LuAnn Walther at Signet Books wanted a new translation of Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables and asked Lee to do it. In London the musical version had just opened, and we knew it was going to be very big. The Broadway premiere was set for March 12, 1987, at the Broadway Theatre, and the Signet version had to be ready before then. A completely new translation on that schedule would have been impossible. Lee suggested to LuAnn that I be brought in as co-translator. I loved the idea, but still with that deadline, we could not make a translation from scratch.

LuAnn suggested we use as the basis for our translaton the classic American translation from the early 1860s by C. E. Wilbour. We agreed. We worked frantically for five months, translating many sections of the Hugo not found in Wilbour, and making a new version for the twentieth century. Lee and I were neighbors: she lived on East 89th and I on East 79th. We delivered packages of pages to each other at the sign of the John Finley Walk in Carl Schurz Park exactly halfway between our residences, and got the book in sections to LuAnn and from her to the printers. LuAnn made sure that the musical’s producer Cameron Mackintosh granted our book the rights to use the show’s already famous logo—Cosette, in a drawing by Hugo himself, and the tattered tricolor flag of France—on our book’s front cover. We finished on time, and for our superhuman effort, the Cameron Mackintosh office gave Lee and me good seats to the opening night, March 12, 1987. We were more than delighted.

In 1989, Lee asked me to work with her again. Scribner had approached her about translating two volumes of the letters of Jean-Paul Sartre, edited by Simone de Beauvoir. I pounced. I had loved Sartre since the 1950s. From 1989 to 1993, Lee and I translated the first volume, which we titled Witness to My Life, and the second, Quiet Moments in a War. Our editor was Erika Goldman. Hamish Hamilton and Penguin published the books in England. The reviews were mostly splendid.

Our Les Misérables sold its millionth copy in 2016. Into its 35th year it continues to sell well.

Lee served as president of the American Literary Translators Association (ALTA) in 1991–1993.

Lee continued her fascination with Francis Ponge, translating three more books: Vegetation, The Nature of Things, and Mute Objects of Expression. The Making of the Pré by Francis Ponge, Vegetation, and The Nature of Things are out of print, and should be republished.

In 2000, the French Government made Lee a Chevalier dans l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres.

Lee and her former husband, Jack Leggett, bought the house on 89th Street, and also a house in Manchester-by-the Sea, Massachusetts, built in the mid-nineteenth century for Richard Henry Dana, Jr., author of Two Years Before the Mast. Lee invited my spouse, Miguel Cervantes-Cervantes, and me often to both houses. We liked to call the Manchester one “the mansion in the woods on a cliff by the sea.” Lee was a great sailor, as are her three sons and their families.

Lee had been in an assisted living facility in Massachusetts since the summer of 2018. She spent the 2021 Christmas holidays at the Massachusetts home of her son and daughter-in-law, Tony and Claire Leggett, and with their three daughters. She died on January 24, 2022 in hospice care, surrounded by family. She was 93.

–Norman MacAfee

The post Remembering Lee Fahnestock (1928 – 2022) appeared first on TRANSLATIONiSTA.

February 2, 2021

Publishers Need More Black Translator Friends

Aaron Robertson

February is Black History Month in the U.S. – a month that is unfortunately still needed since the history of this country is still largely told in ways that marginalize African-American voices and the stories and histories of Black Americans. In the U.S. publishing world, we’ve seen a lot of statements of solidarity with the Movement for Black Lives appearing over the past year, but it remains the case that there are still very few Black publishing executives in positions of sufficient power and autonomy to set policy and priorities in the industry and houses where they work.

In this context, writer/translator Aaron Robertson‘s recent article in Words Without Borders, “Publishers Need More Black Translator Friends,” is particularly helpful in laying out some practical steps that might be taken to increase the number and scope of foreign-language books from Africa and the African diaspora that reach U.S. bookstores in English translation. I highly recommend you head over to WWOB and check it out along with their entire January 2021 issue, entitled International Black Voices on Race and Racism.

Robertson’s article is the latest (to my knowledge) installment of an important conversation about the need for more inclusion and representation in Translationland begun (or revived) on the Harriet blog of the Poetry Foundation half a decade ago with contributions by Daniel Borzutzky, Don Mee Choi, Cecilia Vicuña, Jen Hofer, Lucas de Lima, and John Keene (who weighed in with the influential article “Translating Poetry, Translating Blackness”). Please check them out too!

Some of Robertson’s recommendations have to do with expanding as well as supporting communities of Black translators – starting with outreach among new generations of writers and language-learners who might find a meaningful outlet in literary translation. For aspiring and emerging translators, I would also point out that poet and translator Aaron Coleman is organizing a new community-building initiative for Black writers and translators: The Patchwork Project: A Home for Black Translators & Writers.

I am so glad to know of this ongoing work and eager to support it in the hope of seeing an ever more inclusive and representative range of voices available in English translation.

The post Publishers Need More Black Translator Friends appeared first on TRANSLATIONiSTA.

November 13, 2020

Climbing the Mountain, Part 2

So it’s been about a year now since I started working on my new translation of Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain, but more than half the intervening months were taken up with other matters, so I’m still working on the book’s first 10%. Given the enormous size of this novel (not to mention its density), I find I’ve been working in a different rhythm than with the shorter books I’m used to, which I translated in a series of passes (rough draft, second draft, etc.) For MM, I’m using a more recursive model in which I revise previously translated sections of the book in between working on my first draft of other passages. This approach is helping me deal with the incredibly thorny prose of the long, nostalgic second chapter, detailing Hans Castorp’s childhood.

So it’s been about a year now since I started working on my new translation of Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain, but more than half the intervening months were taken up with other matters, so I’m still working on the book’s first 10%. Given the enormous size of this novel (not to mention its density), I find I’ve been working in a different rhythm than with the shorter books I’m used to, which I translated in a series of passes (rough draft, second draft, etc.) For MM, I’m using a more recursive model in which I revise previously translated sections of the book in between working on my first draft of other passages. This approach is helping me deal with the incredibly thorny prose of the long, nostalgic second chapter, detailing Hans Castorp’s childhood.

I’ve been speaking about my work on the book publicly as well, as a Fall 2020 Berlin Prize Fellow “at” the American Academy in Berlin. The scare quotes are because I’m still in NYC (thanks, Covid-19), but have been very much enjoying the opportunity to interact virtually with my fellow fellows in Berlin and elsewhere. If you’re interested in reading more about my thoughts on The Magic Mountain and the work of translating it, let me refer you to:

“Fresh Air: Thomas Mann and the Literature of Contagion,” a brief article I recently published in The Berlin Journal.

“The Importance of Being Thomas Mann,” a recorded half-hour conversation with the brilliant Veronika Fuechtner, who’s in the middle of writing a book about Mann’s Brazilian mother and the traces of this legacy throughout Mann’s work.

“Translation as Storytelling,” a lecture I just gave at the Academy about my approach to translating classic works in general and this novel in particular. An article based on this talk is forthcoming in the anthology This is a Classic that Regina Galasso is editing for Bloomsbury. (I believe it’s due out in early 2022.) A more essayistic, abbreviated version will be published sooner, in the Jan/Feb 2021 issue of frieze , so keep an eye out if you’re interested!

Meanwhile the next of my self-imposed internal deadlines is rapidly approaching, so I’d better get back to work. Thanks so much for dropping by!

The post Climbing the Mountain, Part 2 appeared first on TRANSLATIONiSTA.

May 12, 2020

Translating the Future: A Conference and Conversation Series

Translationista is coming out of semi-retirement just long enough to announce the launch of Translating the Future: A Conference and Conversation Series celebrating the 50th anniversary of the historic World of Translation conference put on by PEN America (then the P.E.N. American Center).

Translationista is coming out of semi-retirement just long enough to announce the launch of Translating the Future: A Conference and Conversation Series celebrating the 50th anniversary of the historic World of Translation conference put on by PEN America (then the P.E.N. American Center).

In honor of the anniversary, a number of audio recordings of sessions from the 1970 conference have been placed online – can’t wait to start listening!

There’ll be a proper anniversary conference in September, which I’ll announce here, but meanwhile you can enjoy an entire slate of warm-up events (organized, like the conference, by Esther Allen and Allison Markin Powell), starting with this conversation series being live-streamed to a computer near you starting TODAY!

WEEK 1: Tue, May 12, 1:30 p.m. (EDT):

From 1970 to 2020: Translation Transformations

David Bellos in conversation with Karen Emmerich (with snippets from the original audio archive of the World of Translation conference).

WEEK 2: Tue, May 19th 1:30 p.m. (EDT):

Activism & Advocacy in Translation

Madhu Kaza in conversation with Lina Mounzer.

WEEK 3: Tue, May 26th 1:30 p.m. (EDT):

Global Ecopoetics: Poetry, Translation, Climate Change & Public Health

Forrest Gander in conversation with Raquel Salas Rivera.

WEEK 4: Tue, June 2nd 1:30 p.m. (EDT):

Translating for the Future: Children’s Literature in Translation

Lyn Miller-Lachmann and others.

You’ll find information on streaming the conversations on the conference website. See you there!

The post Translating the Future: A Conference and Conversation Series appeared first on TRANSLATIONiSTA.

January 29, 2020

Translation on Tap in NYC, Feb. 1 – 29, 2020

Gentle readers of Translationista, this is your gentle reminder that events announcements can now be found not here but on the “Upcoming Translation Events in NYC” page of the Columbia University School of the Arts website. Like this page, that one will be updated periodically as new events surface, so please continue to forward your events for posting (in the format followed on that site). Wishing you all a beautiful long February filled with translated books!

Gentle readers of Translationista, this is your gentle reminder that events announcements can now be found not here but on the “Upcoming Translation Events in NYC” page of the Columbia University School of the Arts website. Like this page, that one will be updated periodically as new events surface, so please continue to forward your events for posting (in the format followed on that site). Wishing you all a beautiful long February filled with translated books!

The post Translation on Tap in NYC, Feb. 1 – 29, 2020 appeared first on TRANSLATIONiSTA.

January 2, 2020

Translation on Tap in NYC, Jan. 1 – 31, 2020

Happy new year! Like I just said, there’ll be some changes coming on this blog in 2020, but meanwhile here are some translation events I’d like you to know about. (OK, at the time of posting I’ve only heard about one, but more should be following.) And I wish every one of you a happy and healthy new year!

Happy new year! Like I just said, there’ll be some changes coming on this blog in 2020, but meanwhile here are some translation events I’d like you to know about. (OK, at the time of posting I’ve only heard about one, but more should be following.) And I wish every one of you a happy and healthy new year!

Here’s what’s on tap:

Tuesday, Jan. 7:

First Tuesdays: This month’s installment of this regular reading and open-mic series features translator Mark Weiss. More information here. Espresso 77, 35-57 77th St., Jackson Heights (Queens), 7:00 p.m.

Thursday, Jan 16:

Jill!: The latest event in this new women+ in translation reading series will feature translators Mike Fu (Chinese), Nora Carr (Spanish), and Sharon Rhodes (Danish). More information here. Pen and Brush, 29 W. 22nd St., 7:00 p.m.

The post Translation on Tap in NYC, Jan. 1 – 31, 2020 appeared first on TRANSLATIONiSTA.

Susan Bernofsky's Blog

- Susan Bernofsky's profile

- 62 followers