Deborah Blum's Blog, page 6

February 5, 2011

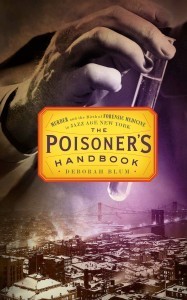

Update: The Poisoner's Giveaway

I was thrilled to wake up this morning and find almost 60 entries – ideas for blog posts about poison and chemistry in general – for my paperback giveaway of The Poisoner's Handbook.

I was thrilled to wake up this morning and find almost 60 entries – ideas for blog posts about poison and chemistry in general – for my paperback giveaway of The Poisoner's Handbook.

Sadly, the entry period is over and although you are still welcome to comment, no entries received after this announcement posts will be accepted as giveaway candidates. As you'll recall from the original announcement, I'm going to select up to ten of my favorite ideas from this list of entries. Actually, all the ideas look very good to me so this is going to be a tough decision-making process.

But I promise to announce the results on Monday. Winners will be contacted by me directly to get mailing information for their paperbacks.

Autographed, of course!

February 3, 2011

To our friends in Egypt

Finally they recognized that we are not animals and they opened the internet I am fine as well as my family… me and my wife we are expecting she should deliver after 2 weeks …hope that things calm down wisely

Pray for us Deb

Oh, I am. I absolutely am, Ashraf. I think of you – you, and Nadia, and Dalia and Mohammed, and Magdy and more – in this week of increasing craziness and brutal government response in Cairo. I think and I hope and I make bargains with the universe if it will just keep my friends safe.

I've watched uprisings and protests in other countries before with the usual detachment one feels when it's someone else's country, someone else's issue. Or that's what we usually tell ourselves, as if it was happening on some other planet, as if it didn't involve people who – just like us – want a decent life, dignity, respect for what they do and what they dream of doing.

Actually, I'm bargaining with the universe on that front as well. That you will prevail in these protests, this courageous and this heartfelt stand for a free and democratic country.

That this is your time.

I got the e-mail from you yesterday and it brought back to me a bright day in Cairo last July. I was meeting you and other local science journalists to help plan for the World Conference of Science Journalists. And you were worried that it was hot and I wasn't drinking anything and you hurried off to get me some tea. And wouldn't let me pay for it because I was your guest in your country.

Geez, that happened to me a lot in Cairo. The hospitality, the instinctive generosity. I stayed with my friend Nadia El-Awady at her apartment, displacing her sons from their bedroom. "You're our guest," they kept saying, when I tried to buy a gift, a coffee, a meal. "It's your home," they said, when I apologized for taking the boys' room. And when I went shopping for gifts to take home to my family, Nadia and Dalia Abdel Salam bargained fiercely on my behalf. No guest of theirs was going to pay too much for even the smallest souvenir.

Nadia and Dalia are, of course, the co-organizers of the WCSJ-2011, due to be held this June in Cairo. I'm working with them as program chair, part of a bridge-building partnership between Arab and American science writers that dates back almost four years.

The National Association of Science Writers (NASW) joined in a partnership with the Arab Science Journalists Association (ASJA) in 2007. It was an unlikely time to connect two such different groups. At the time, we were deep into George W. Bush's insanely wrong and wrong-headed war in Iraq. We were determined to overcome that though. We thought we could learn from each other and we believed – I believed, Nadia believed – that we could learn also to trust each other.

We have, you know. I've been incredibly proud of my NASW friends and colleagues in this regard. They've contributed time and money, ideas and passionate commitment to making our partnership work. We brought the ASJA members to the United States and NASW members including myself have traveled to a variety of Arab countries – Qatar, Morocco, Jordan, Dubai, Egypt – to work with science journalists there.

But, oh, I've admired our ASJA partners as well. Nadia, Dalia, Mohammed Yahia, a blogger for Nature who manages the conference website, Cairo newspaper science editor Magdy Said and Waleed Al-Shobakky, current president of the Arab Science Journalists Association, and, of course, a quiet, serious newspaper science editor named Ashraf Amin, who sent me that e-mail this week. They're amazing hosts, they're united in wanting to raise the bar, to foster not just the conference but science journalism in the Middle East, and as you can undoubtedly tell from this post, I value them as friends.

I can promise you that I've worked hard on this conference, many people at NASW have worked hard – but our Arab partners have worked harder. They know much is at stake – if all goes as planned, this will be the first WCSJ in an Arab country, the first on the African continent, the first in the developing world.

And in the most selfish way, I want them to have that conference, exactly as planned, exactly as scheduled – a showcase for the talent, and intelligence and the passion for communicating science that exists in the Arab world. We all want that actually. The umbrella group for this conference, the World Federation of Science Journalists, issued a statement to that effect just yesterday. We're still planning on it, by the way.

But I'm not bargaining with the universe about the conference at this moment. My hopes and thoughts and energy are directed at wishing my friends safe through a turbulent time. At despising the Mubarak regime and agreeing with our current president (Oh, I do like him so much better than the previous version) that the time for change is now.

Our colleagues, our fellow science journalists, our friends – the people of Egypt – deserve exactly what we fought for ourselves when this country was born in revolution – those same inalienable rights that we still name with just pride: life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

To quote the great Thomas Jefferson on that very point: "That to secure these rights, governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed. That whenever any form of government becomes destructive to these ends, it is the right of the people to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their safety and happiness.

Or as we like to say today: Let freedom ring!

January 27, 2011

The Poisoner's (paperback) giveaway

My book, The Poisoner's Handbook, came out in paperback this week. My publisher kept the beautiful cover – my all time favorite – with the test-tube glowing like a moon over 1920s New York City and the title printed on an old-time poison label.

My book, The Poisoner's Handbook, came out in paperback this week. My publisher kept the beautiful cover – my all time favorite – with the test-tube glowing like a moon over 1920s New York City and the title printed on an old-time poison label.

When I look at it I see an amazing year since hardback publication. I spent most of it traveling around the country – and sometimes outside it – talking about poison, murder and a pair of crusading scientists determined to change the world. I remember the hours I've spent answering letters and e-mail from readers, some of whom wanted me to solve their family murders. A lawyer from Kentucky called to describe the way his step-mother had killed his father with backyard weeds. He'd decided to have the body exhumed. "I know my sister-in-law poisoned my brother," wrote one man. "I saved a few hairs from his head before she had him cremated. What should I have them tested for?"

My publisher sent me on a ten-city book tour with a strong advance warning: do not tell people how to kill each other. And I didn't. But they asked. "I'm belong to the Hemlock Society," one woman said. "And I'm just wondering if there's any special compound you might recommend for a peaceful death." Sometimes these questions can be a little scary. But so, apparently, can I. At a neighborhood party for the book, people on my block reassured my husband that they were there for him, just in case.

He's still safely drinking coffee, in case you wondered, although for some reason he's quit drinking it with me. He just didn't expect, when we got married, to find himself living with a woman whose personal library is packed with books on lethal substances. "I found some really good ingredients for an excellent poison at the grocery store," I reported one day. "Is that so?" he replied, taking himself and his cup elsewhere.

I started a blog – this blog, in fact, and I thought it would be a great place to tell those wonderful, troubling stories of poisons, of our chemical past. And I did that. But I found myself as often writing of our chemical present, of lead poisoning, of modern murder, of carbon monoxide, as murderous today as it was in the 1920s. I was reminded often of how much I love chemistry – that fundamental, beautiful and sometimes sinister science. And I've learned more about it in this year of trying to illuminate the chemical web that weyett navigate every day.

It's been an exhausting, exciting and, yes, educational year leading up to this paperback. And in honor of it, I'd like to propose an exchange with you, the readers of this blog. Send me your ideas for a Speakeasy Science blog post – a poison, a murder, a compound, a dangerous plant, a corner of our chemical world that needs investigation. Just send them in as a comment.

I'll pick my favorites – up to ten – and the winners will receive a copy of the paperback from me. I'll contact you directly if you've won and arrange to send you a copy. True, you can buy it yourself for a great price. But I hope you'll like the idea of having your interesting ideas explored here. And, don't forget, all winner's copies will be autographed by the author herself!

I'll be accepting ideas in the comment section for a full week. You are welcome to suggest more than one idea, of course. Hoping to hear from many of you in this celebration of The Poisoner's Handbook paperback!

January 19, 2011

Up in Smoke

In the last months of her life, my mother-in-law simply denied that she started smoking cigarettes when she was 15 years old. And that – some 65 years later – she still was.

She hid the carton in her dresser under the thin disguise of a layer of t-shirts. She slipped them out when no one was looking, opening the sliding doors of the bedroom, huddling into the shrubbery along the wall, hiding in a haze of smoke and greenery. She trailed the scent of burnt tobacco with her anyway.

"She told the doctor she didn't smoke," my husband confided over the phone. He was calling from a California emergency room in the deep summer of last year, shortly after his mother was diagnosed with lung cancer. His voice sounded soft with grief and worry and guilt. He'd found the hidden carton and hadn't thrown it away yet.

"Did you tell him the truth?" I ask.

"Did you want me to call my mother a liar?" he snaps.

"Yes," I flash back. "He needs to know." Anger and worry hiss across the connection. Both of us right, both of us wrong, catching for that balance between honesty and dignity that's so hard to find in a terminal illness.

But he sighs. She'd finally made herself say she used to smoke, maybe a few cigarettes, you know, now and then. The doctor's voice had been soft also. Gentle even.

He could tell, he said, just by looking at her. I can imagine how she looked there in over-hyped clinic lights: a slight woman with blond hair fading to silver, Norwegian blue eyes, a smile that blazed with friendliness.

Usually, you couldn't miss the smile. But the doctor, I realize, was reading her differently. He saw instead, the etching of lines, the roadmap face of a long-time smoker.

The Mayo Clinic offers this rather ruthless description of the way smoking erodes the skin: "The nicotine in cigarettes causes narrowing of the blood vessels in the outermost layers of your skin. This impairs blood flow to your skin. With less blood flow, your skin doesn't get as much oxygen and important nutrients, such as vitamin A. Many of the over 4,000 chemicals in tobacco smoke also damage collagen and elastin, which are fibers that give your skin its strength and elasticity. As a result, skin begins to sag and wrinkle prematurely because of smoking."

It tells you maybe more than you want to know about the corrosive nature of cigarette smoke. Or maybe not enough; it just hints at the havoc those compounds can create internally – the weakening of the heart and lungs, the sly spread of cancerous tissue. But it doesn't really tell you about the woman, smiling nervously at the doctor while he studies the chemical etching of her face.

Her name was Helen. She laughed like a loon at bad jokes and could dance like a wild woman. She surrounded her home with flowers and fruit trees – peaches and apricots, pomegranates and oranges. When we moved from California to Wisconsin, she bombarded us with boxes of walnuts, oranges, raisins, jars of home-made pomegranate jelly. She took in unwanted cats, wandering dogs, and just about anyone who she thought needed care and feeding. She wanted to make people happy and found it almost impossible to tell them no, a blessing and a curse.

She'd been trying to quit smoking ever since I knew her, an endless struggle with a habit that dated back to 1945. "Don't tell Peter," she would say to me when she came to visit. "Don't do it," I'd say. "I'm down to just a couple a day," she'd insist. "I'm almost done with them."

She'd go sneaking out into the backyard, sometimes shivering in the icy drift of a Wisconsin winter, sometimes leaning against the mulberry tree on a summer evening with the air so soft you could barely see the thin ribbon of smoke.

When my husband threw those hidden cigarettes away last summer, she never said a word.

In November, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration announced plans to require new, more graphic warning labels on cigarette packs: images of a corpse with black stitches tracking up the chest, a mother blowing a gray cloud on a child, toe tags on a body and some cautionary words. WARNING: Smoking can kill you.

Cigarette companies are already going to court to fight the new labels, which are scheduled to take effect this summer. My favorite quote on the subject comes from a New York Times story in which a tobacco company executive complains that the graphic warnings could "denormalize" smoking.

The truth is, there's no warning that comes close to describing a smoker's death. Smoking can kill you, the label says. It doesn't say that death can come like a benediction. That the pain from the spreading cancer can be so intense that you will be gasping with it even while unconscious. That when your son flies to California to say goodbye, you won't know him. You'll look look at him, eyes glazed with narcotics, and you'll call for your mother, dead these 30 years.

After the funeral on Sunday, one of my nephews wonders about the way she chanted her mother's name at the end. We're back at her home, leaving behind the chapel with its welter of flowers and history of grief. I had not realized how empty a house can seem, even when full of people. "Maybe she saw her," he says. "Maybe she knew they'd be together again."

"I hope so," I answer.

But mostly I hope she felt safe in those last moments. That she wasn't in some dark place, calling for a protector who didn't come. I wish for her to be tucked away, happy and warm, in the home of her childhood. Or in a garden awash with orange trees and the starry tangle of jasmine. And I wish for what I cannot have. I wish she had never tried that first cigarette, answered its beckoning glow, taken the path that brought us to this January day as gray and cloudy as smoke itself.

January 5, 2011

A Chemical-Free Resolution

In honor of the International Year of Chemistry, I would like to propose a simple resolution.: Let's resolve to give up the ridiculous, the misleading, the this-is-simply-not-possible-so-just-let-it-go phrase "chemical-free".

In honor of the International Year of Chemistry, I would like to propose a simple resolution.: Let's resolve to give up the ridiculous, the misleading, the this-is-simply-not-possible-so-just-let-it-go phrase "chemical-free".

Why, oh why, in the first week of this celebratory chemical year do I find myself reading on Natural News that "We go to great pains to drink only pure, chemical free water." Maybe in an alternate universe but in this one pure water is a chemical compound. It even has a chemical formula, H2O, which is just another way of saying that it's composed of the chemical elements hydrogen and oxygen.

Model courtesy of 3Dchem.com

In fact, H2O is an essential part of our own body chemistry. Actually, we're a walking soup of chemical compounds; scientists have tallied up some 60 elements in the human body, with oxygen being the most abundant and tungsten being barely there. I've always especially liked knowing that the primary elements that make up our bodies were created long ago in the blaze of stars around us, that we are basically what the astronomer Carl Sagan liked to call "star stuff."

In other words, in a chemical-free world we wouldn't exist.

Yes, I realize that particular phrase was coined by an advertising genius to market products that are meant to be free of industrial or synthetic chemical compounds. And that it's become synonymous with "evil" chemical free. That's why we see headlines like this recent one in the Anchorage, Alaska paper: "Gardeners: Go Chemical-Free in 2011", which, of course, would be during the International Year of Chemistry.

"My wish is that each and every one of us will resolve to turn our backs on the use of chemicals," writes the author of the Anchorage piece. He's not alone in this perspective. If I google the term "chemical free" I get more than 60 million hits in .15 seconds. The number one hit, the website "Go Chemical Free", assures me that a chemical-free diet could help eliminate autism.

Folks, let's be literal for a moment. If we don't use chemicals on our gardens, we won't even be able to use H20 on the plants. And if we restrict ourselves to only chemical-free food we'll be, um, dead. Starvation tends to do that, you know.

Carbon atom (black) bonds with oxygen (red) to form CO

This doesn't mean that I am dismissing the risks posed by many industrial use of chemicals. I spend a depressing amount of time on this blog writing cautionary posts about compounds such as carbon monoxide, which kills hundreds of people in this country every year and sickens thousands. But let's not fool ourselves into thinking that "industrial chemical free" means "toxic chemical free". Let's not forget such well known natural elements as arsenic (As) or lead (Pb).

And all this pseudo-protective chemical-free propaganda does nothing to make us really safer. Instead, it muddies our understanding of the legitimate risks out there. And it muddles our appreciation of ourselves and our own wonderfully complex chemistry. If we all learned this in school, then the distinction wouldn't matter so much. But because we don't, because we're still trying to figure out how to teach science well, chemical-free marketing can act as a weird – and weirdly wrong – kind of post-secondary instruction.

So it's worth pushing back. My favorite scientific response is from the Royal Society of Chemistry in the UK, which last year offered £1 million to the first person to create a genuinely chemical free product. That was almost a year ago and they're still waiting for a winner – which, of course, means that those chemical-free water people over at Natural News still have a chance.

But back to the IYC 2011 and its upbeat motto: "Chemistry—our life, our future". Myself, I prefer the direct approach: "It's a chemical world. Learn to live with it." But just in case that's just a sign of crankiness, I'll go go treat my frustrations with a large glass of C2H5OH. Preferably of the Pinot Noir variety. Of course, Pinot Grigio will do.

December 31, 2010

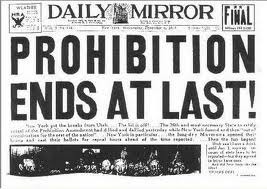

At the Prohibition Bar

In these last moments of 2010, when we raise a glass to the end of the year and the promise of the new one, let's not forget to appreciate that our cocktails are legal and the alcohol in them is unlikely to kill us where we stand. It's especially worth remembering as this year was, after all, the 90th anniversary of that great American experiment called Prohibition.

Prohibition – which made the manufacture, sale, transportation, import and export of alcoholic spirits illegal – began with final approval of the 18th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1919. But it only went into effect in 1920. Although not with the effect, the shining dawn of an alcohol-free nation, that its supporters had hoped to see. Legal drinking definitely disappeared. But scholars today still debate whether Prohibition – which lasted until the 18th Amendment was repealed in 1933 – ever reduced consumption of alcohol in the United States.

It's difficult to measure because so much drinking was done secretly, so many bottles acquired from under pharmacy counters, at roadside ice-cream stands, from grocers and cobblers, and from the countless speakeasies (for which this blog is named) that replaced the rowdy saloons and regulated bars of earlier times. As I discovered from researching The Poisoner's Handbook my story of murder and forensic science in the 1920s, some 30,000 speakeasies were opened in New York City alone during the Prohibition era.

As soon as legal drinking ended, purveyors of illicit alcohol came forward with substitute beverages – moonshine liquor made from wood scraps and sawdust and oddments of plants. In one of my favorite cases, federal agents discovered that moonshiners in Tennessee were cooking a brew made from poison ivy. But there were worse mixtures.

In the first month of Prohibition, poison alcohol deaths rippled across the country: eight in New York City, four dead in a single day in Hartford, Connecticut, two in Toledo, seven in Washington D.C. Soon the police discovered that murderers had learned to take advantage. In a typical case, barely a month after Prohibition, two men were found dead in Newark, several hours after buying liquor at a Bowery joint. The victims were thought to be alcohol deaths until a standard chemical analysis of the bodies found they were loaded with potassium cyanide. And the killer, whoever he was, was long gone.

Within a year, the once openly rowdy saloons had given way to secretive speakeasies and to bootleggers who would sneak gin to one's door at a delivery rate of $2 a bottle. By summer's end, a bare half year into the new amendment, New York officials were already worrying about the direction of Prohibition enforcement. In August, a Brooklyn magistrate presided over the trial of a burglar who broke into a supposedly closed saloon and spent a night guzzling its gin supplies, vented his frustration: "Prohibition is a joke. It has deprived the poor workingman of his beer and it has flooded the country with rat poison."

Police department chemists, analyzing the so-called gin in the Brooklyn bar and around the city, reported that much of it was industrial alcohol, re-distilled to try to remove the wood alcohol content. The re-distilling was not notably successful. The poisonous alcohol remained and there was more: the chemists had detected traces of kerosene and mercury, and disinfectants including Lysol and carbolic acid in the beverages. "Drinkers are taking long chances on their health," warned the police commissioner, "if not their lives."

Dry agents with confiscated stills (courtesy: The Denver Post)

But for the new speakeasy devotees, the risk was part of the fun. Sometimes it was all the fun. It was amusing, exotic, to spend time in the dim light and hot jazz of some hidden corner, to experiment with the strange liquids that appeared at the table. In his 1927 book, New York Nights, writer Stephen Graham described the mix of anticipation tinged with fear when the waiter "brought me some Benedictine and the bottle was right. But the liqueur was curious – transparent at the top of the glass, yellowish in the middle and brown at the base…Oh, what dreams seemed to result from drinking it… That is the bane of speakeasy life. You ring up your friend the next morning to find out whether he is still alive."

At the underground clubs, bartenders enjoyed new respect but also were driven to a new burst of creativity, responding to the frequent need to disguise the taste of the day's alcohol. From the speakeasies came a new generation of cocktails heavy on fruit juices and liqueurs to mix with the bathtub gin, the bright and spicy additions covering the raw sting of the spirits. There was the Bennett cocktail (gin, lime juice, bitters), the Bees Knees (gin, honey, lemon juice), the Gin Fizz (gin, lemon juice, sugar, seltzer water), the Southside (lemon juice, sugar syrup, mint leaves, gin, seltzer water).

At least those were the kind of drinks served at the city's classier joints, say, Jack and Charlie's 21 on 52nd Street. Or Belle Guinan's El Fey Club on West 45th, where the hostess gleamed like a candelabra and the house band played "The Prisoner's Song" when dry agents were spotted in the crowd. Down in the tattered neighborhood of the Bowery, as the police could tell you, the drink of choice was a cloudy cocktail called Smoke, made by mixing water and fuel alcohol. Smoke joints were tucked into the back of paint stores, drug stores, markets, tucked among the dry goods and the stacked cans. The drink was blessedly cheap – 15 cents a glass – and just about pure wood alcohol.

In a bad season, smoke deaths in the Bowery averaged one a day. And the deaths from poison alcohol rose in the mid-1920s thanks to a government notion that if the illegal alcohol was somehow more poisonous, it would scare people into obeying the law. By all accounts, that rather murderous government program – which involved adding toxic contaminants to the industrial alcohol being siphoned off by bootleggers - killed more than 10,000 people. I wrote about it in my book but also in a piece for Slate called The Chemists' War, about the failed efforts to stop the poisoning of alcohol, about the then-City Medical Examiner of New York City, Charles Norris furiously challenging the government's essay in extermination, especially he said, of people who could only afford to drink the dregs.

Because if you had enough money, you could buy your way into a less lethal cocktail, enjoy those jazz-flavored parties so symbolic today of the Prohibition era. Until he was busted by government agents, one of the most famous purveyors of good Prohibition era whiskey to the wealthy was a rum-runner named William McCoy. If you purchased your liquor from him it was guaranteed good, in fact, it was the real McCoy. Once the 18th Amendment was repealed in 1933, the government once again took over that job of inspecting (and taxing) potable spirits, of assuring consumers that their beer and wine and whiskey was regulated, inspected, legitimate.

We've settled back into our safer world of regulation. But we still carry our prohibition legacy with us – our wariness of moral crusades, our distrust of one group imposing its higher values on another. Lessons worth learning, actually. So as we close out this year, this 90th anniversary of a great mistake, let's make a toast to our Prohibition past, let's raise a cocktail glass to health and hopes and happiness and our complete confidence that we are about down and trust that the real McCoy.

December 14, 2010

Calling Dr. Kane

Harry Block: I'm no biologist, but how many cells do single-celled organisms have?

Ira Kane: Harry, if we're going to be big important scientists you have to start to act the part.

I've been irresistibly reminded this month – ever since NASA scientists announced their work on an "arsenic-based life form" – of the 2001 movie Evolution. The story is of an alien organism that rides a flaming meteorite into the Arizona desert one night. The organism is single-celled on arrival but it evolves so rapidly that within a few days it's bugs, it's a bunch of big-toothed fish, it's a hassle of dinosaurs, it's an enormous earth-destroying giant mushroom thing.

Scientists Confront a Nitrogen-Based Life Form (KnowTheMovies.com)

What makes this organism so special? It's a nitrogen-based life form! Why nitrogen? No idea. But, fortunately, the brilliant chemist in charge of the local community college's science department, Dr. Ira Kane (David Duchovny) has nailed it. He and a geologist colleague, Harry Block (Orlando Jones) therefore call a meeting in front of – yes! – a wall chart version of the Period Table of the Elements, so that everyone can get the chemical picture.

No, really, he does. But more about that later. One of my favorite aspects of the NASA announcement – and the scientific controversy following – is that Periodic Table images have abounded. I just caught one in the Pharyngula dissection of the possibility (he thinks not) of arsenic-based life forms. Could this be a start on a better world, one in which we fly Periodic Table charts like triumphant banners?

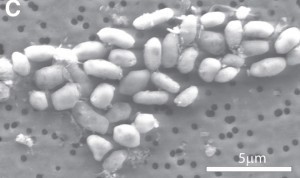

Oops, digressing. If you haven't heard – many times – here's how all this started: On December 2, NASA held a press conference to announce publication of a paper by a research team, led by astrobiologist Felisa Wolfe-Simon. The scientists had developed a strain of bacteria that could thrive using arsenic rather than phosphorus, which is used by every organism on Earth to sustain life.

The implications of this – a life form based on arsenate (one arsenic atom and four of oxygen) rather than phosphate (one phosphorus atom and four of oxygen) were thrilling. As science journalist Carl Zimmer wrote for Slate, "Every living thing that scientists have ever studied uses phosphorus to build the backbone of its DNA… If the authors of the paper were right, we would have to expand our notions of what forms life can take."

We might have to consider that across the universe, alien creatures might be bubbling up from their un-Earth-like environments, unfettered by our particular terrestrial chemistry.

Of course, on Earth, arsenate and phosphate do have well-established relationship. Arsenic is a dangerous poison because it's structurally enough like phosphorus that the body will mistakenly take it up and circulate it into the cellular machinery. This is, in fact, the killing mechanism, allowing arsenic to infiltrate and destroy any phosphate-dependent cell that it enters. And this is the reason that NASA scientists had made a point of looking for arsenic-tolerant bacteria to begin with, hunting them down in the poison-rich waters of California's Mono Lake.

So the NASA investigation was chemically logical. It was biologically logical. As we all know – from antibiotic resistance, if nothing else – bacteria are wonderfully adaptive, rapidly evolving creatures (although not rapidly evolving enough for a spectacularly crazed movie plot). In fact, three years ago, the National Academy of Sciences suggested that arsenic-based life might be a possibility on other worlds.

NASA scientists confront arsenic-based bacteria (Photo courtesy of Science)

Although he acknowledged the exciting idea behind the work, Zimmer's Slate piece was mostly a portrait of scientific unhappiness with the NASA results. The very real problem – the one that has dogged NASA since the announcement – is that many independent scientists found the experiment sloppy. This critical response is the way science works at its best, of course. Researchers announce a finding and other researchers scrutinize the work, testing its solidity. In the first few days, after the NASA paper was published, it appeared that only the agency itself was dazzled by the science.

Harry Block: Shouldn't we call the government to help us out on this?

Ira Kane: Absolutely not! I know those people.

British science writer Ed Yong did a terrific job of chronicling the arsenic-based life story's rise and fall on his blog, Not Exactly Rocket Science. Some scientists were especially bothered by the fact that the agency scientists didn't entirely remove phosphorus from the solution that they used to grow the arsenic-loving bacteria; it seemed to muddy the findings. Others suggested that NASA hadn't clearly demonstrated the presence of arsenic in bacterial structures at all.

And others suggested that part of the problem lay in the desire of space agency scientists and the journal Science, where the article was published, to hype the results. Not to mention the willingness of science journalists to swallow the hype whole. That was the point raised by Dave Munger, editor of ResearchBlogging.org, in a post for Seed magazine titled "Death of Arsenic-Based Life?" Still, Munger continues, "Despite all the misinformation and, perhaps, over-hyping of the study, the findings are still very interesting."

And they are, if for no other reason that arsenic is a very crafty poison and any organism able to tolerate it in high doses is pretty damn fascinating. To me though, the hype, the buzz, the sense of let-down that followed the critiques, tells us something else as well. It says that we loved this story because most of us hoped it was true. We're just here – spinning on a bright little island in the black emptiness of space. How could we not wish for other life forms, for the chemical chance of other beings spinning their own lives out on the twinkle of other planets?

Munger also points out that it's too early to give up. All this up-and-down, back-and-forth is what eventually leads us to a really solid scientific result. And he's right, of course. But that doesn't mean that we don't long occasionally for a Dr. Ira Kane who steps up to a Period Table, and just nails the alien life concept – it's nitrogen, folks! - and, oh, by the way, uses that same arrangement of elements to save the world.

Harry Block: So, do they give the Nobel Prize out in yearly payments or is it just one lump sum, like the lottery?

Ira Kane: Let's not get ahead of ourselves.

Harry Block: Oh, I'm not getting ahead of myself. I'm very concerned about the potential tax consequences.

See what I mean? Now that would have been a great story.

(All quotes from Evolution courtesy of IMDb)

Deborah Blum's Blog

- Deborah Blum's profile

- 439 followers