Stephen Hong Sohn's Blog, page 9

May 21, 2024

A Review of Justinian Huang’s The Emperor and the Endless Palace (MIRA, 2024)

Posted by:

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) ccape

ccape

Written by Stephen Hong Sohn

Edited by Corinna Cape

Justinian Huang’s debut novel, The Emperor and the Endless Palace (MIRA, 2024) was one that was recommended to me by two former students of mine. I occasionally keep in touch with former students through unofficial reading groups. I’m glad I got to read this one, which is sort of a low-fantasy, silkpunk inspired work involving queer Asian American romance.

Let’s let the official marketing description give us some context: “In the year 4 BCE, an ambitious courtier is called upon to seduce the young emperor—but quickly discovers they are both ruled by blood, sex and intrigue. In 1740, a lonely innkeeper agrees to help a mysterious visitor procure a rare medicine, only to unleash an otherworldly terror instead. And in present-day Los Angeles, a college student meets a beautiful stranger and cannot shake the feeling they’ve met before. Across these seemingly unrelated timelines woven together only by the twists and turns of fate, two men are reborn, lifetime after lifetime. Within the treacherous walls of an ancient palace and the boundless forests of the Asian wilderness to the heart-pounding cement floors of underground rave scenes, our lovers are inexplicably drawn to each other, constantly tested by the worlds around them. As their many lives intertwine, they begin to realize the power of their undying love—a power that transcends time itself…but one that might consume them both.”

Huang clearly has some knowledge of Chinese cultural and historical contexts, which is crucial to the two sections set in 4 BCE and the 1700s. Here, the novel treads silkpunk fantasy grounds, as we’re in periods where palace intrigue and fox spirits are respectively integrated into the narrative. The novel is primarily anchored in the present day, as River, a queer Asian American man, has a mysterious run-in with a handsome stranger named Joey. The weirdest element of this contemporary storyline is that River meets Joey at a party, but while he is traipsing through the palatial estate in which the festivities are being held, he accidentally steps into a room filled with statues with individuals who look like him. River questions his perception of the experience, as he comes to the party under the influence of drugs. Nevertheless, River is under the impression that there is something more to this connection to Joey, which propels the plot into motion. Interspersed with the contemporary sections are the parts set in the Chinese past. Each of these earlier narratives also involves a romance plot between two men, or at least two individuals who appear to be men. The romance quotient in this novel is high, as this text comes out of MIRA, which is something I should have expected, but nevertheless there were moments I was pulled out of the plot, as Huang wanted to make clear that these relationships are not only illicit but very charged as well. The most interesting aspect of this novel for me was trying to figure out how the narratives would come together. As it becomes clear that Huang is playing with tropes of reincarnation, he still has a couple of tricks under his sleeve because we do not exactly know how River and Joey are situated in those past narratives. It is only within the last 100 pages or so that Huang begins to reveal his cards. Naturally, it is in this phase that the novel moves quickest, as we begin to see how River and Joey’s love has been thwarted over time. What I appreciated most is how the novel ultimately gives us a historically-expansive narrative involving queer Asian and queer Asian American men, something which is still fairly uncommon in contemporary fictional cultural productions. A fun read involving queer Asian/American romance, mischief, with some magical realism thrown in to keep us on our toes.

Buy the Book Here

comments

comments

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) ccape

ccape

Written by Stephen Hong Sohn

Edited by Corinna Cape

Justinian Huang’s debut novel, The Emperor and the Endless Palace (MIRA, 2024) was one that was recommended to me by two former students of mine. I occasionally keep in touch with former students through unofficial reading groups. I’m glad I got to read this one, which is sort of a low-fantasy, silkpunk inspired work involving queer Asian American romance.

Let’s let the official marketing description give us some context: “In the year 4 BCE, an ambitious courtier is called upon to seduce the young emperor—but quickly discovers they are both ruled by blood, sex and intrigue. In 1740, a lonely innkeeper agrees to help a mysterious visitor procure a rare medicine, only to unleash an otherworldly terror instead. And in present-day Los Angeles, a college student meets a beautiful stranger and cannot shake the feeling they’ve met before. Across these seemingly unrelated timelines woven together only by the twists and turns of fate, two men are reborn, lifetime after lifetime. Within the treacherous walls of an ancient palace and the boundless forests of the Asian wilderness to the heart-pounding cement floors of underground rave scenes, our lovers are inexplicably drawn to each other, constantly tested by the worlds around them. As their many lives intertwine, they begin to realize the power of their undying love—a power that transcends time itself…but one that might consume them both.”

Huang clearly has some knowledge of Chinese cultural and historical contexts, which is crucial to the two sections set in 4 BCE and the 1700s. Here, the novel treads silkpunk fantasy grounds, as we’re in periods where palace intrigue and fox spirits are respectively integrated into the narrative. The novel is primarily anchored in the present day, as River, a queer Asian American man, has a mysterious run-in with a handsome stranger named Joey. The weirdest element of this contemporary storyline is that River meets Joey at a party, but while he is traipsing through the palatial estate in which the festivities are being held, he accidentally steps into a room filled with statues with individuals who look like him. River questions his perception of the experience, as he comes to the party under the influence of drugs. Nevertheless, River is under the impression that there is something more to this connection to Joey, which propels the plot into motion. Interspersed with the contemporary sections are the parts set in the Chinese past. Each of these earlier narratives also involves a romance plot between two men, or at least two individuals who appear to be men. The romance quotient in this novel is high, as this text comes out of MIRA, which is something I should have expected, but nevertheless there were moments I was pulled out of the plot, as Huang wanted to make clear that these relationships are not only illicit but very charged as well. The most interesting aspect of this novel for me was trying to figure out how the narratives would come together. As it becomes clear that Huang is playing with tropes of reincarnation, he still has a couple of tricks under his sleeve because we do not exactly know how River and Joey are situated in those past narratives. It is only within the last 100 pages or so that Huang begins to reveal his cards. Naturally, it is in this phase that the novel moves quickest, as we begin to see how River and Joey’s love has been thwarted over time. What I appreciated most is how the novel ultimately gives us a historically-expansive narrative involving queer Asian and queer Asian American men, something which is still fairly uncommon in contemporary fictional cultural productions. A fun read involving queer Asian/American romance, mischief, with some magical realism thrown in to keep us on our toes.

Buy the Book Here

comments

comments

Published on May 21, 2024 11:23

A Review of Justin Torres’s Blackouts (FSG, 2023)

Posted by:

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) ccape

ccape

Written by Stephen Hong Sohn

Edited by Corinna Cape

Occasionally, you read outside of your established field and want the world to know about a book you’ve read. Such is the case with Justin Torres’s Blackouts, which follows his equally stunning but very different debut We the Animals. Torres’s signature, gorgeous prose grounds us, but Blackouts is a different “beast” entirely, made of up archival documents, pictures, redacted portions of apparent academic studies concerning sexology and queerness, especially as it developed in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It’s clear that Torres had to engage in some robust research for this work, which informs and animates his characters and the narrative itself.

Let’s let the publisher do some work for us: “Out in the desert in a place called the Palace, a young man tends to a dying soul, someone he once knew briefly but who has haunted the edges of his life: Juan Gay. Playful raconteur, child lost and found and lost, guardian of the institutionalized, Juan has a project to pass along, one built around a true artifact of a book—Sex Variants: A Study of Homosexual Patterns—and its devastating history. This book contains accounts collected in the early twentieth century from queer subjects by a queer researcher, Jan Gay, whose groundbreaking work was then co-opted by a committee, her name buried. The voices of these subjects have been filtered, muted, but it is possible to hear them from within and beyond the text, which, in Juan’s tattered volumes, has been redacted with black marker on nearly every page. As Juan waits for his end, he and the narrator recount for each other moments of joy and oblivion; they resurrect loves, lives, mothers, fathers, minor heroes. In telling their own stories and the story of the book, they resist the ravages of memory and time. The past is with us, beside us, ahead of us; what are we to create from its gaps and erasures?”

I was thinking about Torres’s choices here: to reconsider the place of both women and minorities in the archive of queer studies. Their lives and their histories have been typically marginalized and, in some cases, as this novel shows, co-opted entirely by other scientists and scholars. Torres seems to be interested in reminding us though that erasures create other erasures. If Jan Gay’s name is buried, so too is Juan’s presence as well, which leads us back to the presence of the narrator, who exists as a kind of younger foil to Juan, someone eager to discover the history of a kind of queer, BIPOC ancestor. I do not know if Torres found robust evidence of such figures in the archive, but the confluence of documents collected (whether fictionally generated or not) suggests that BIPOC individuals were typically objects of study. Thus, narrative provides Torres the apparatus to reconsider the centrality and psychic/emotional expansiveness in characters like Juan and the narrator, while also reminding us that the toil of existing on the margins is truly a madhouse that one is never guaranteed to survive.

Buy the Book Here

comments

comments

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) ccape

ccape

Written by Stephen Hong Sohn

Edited by Corinna Cape

Occasionally, you read outside of your established field and want the world to know about a book you’ve read. Such is the case with Justin Torres’s Blackouts, which follows his equally stunning but very different debut We the Animals. Torres’s signature, gorgeous prose grounds us, but Blackouts is a different “beast” entirely, made of up archival documents, pictures, redacted portions of apparent academic studies concerning sexology and queerness, especially as it developed in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It’s clear that Torres had to engage in some robust research for this work, which informs and animates his characters and the narrative itself.

Let’s let the publisher do some work for us: “Out in the desert in a place called the Palace, a young man tends to a dying soul, someone he once knew briefly but who has haunted the edges of his life: Juan Gay. Playful raconteur, child lost and found and lost, guardian of the institutionalized, Juan has a project to pass along, one built around a true artifact of a book—Sex Variants: A Study of Homosexual Patterns—and its devastating history. This book contains accounts collected in the early twentieth century from queer subjects by a queer researcher, Jan Gay, whose groundbreaking work was then co-opted by a committee, her name buried. The voices of these subjects have been filtered, muted, but it is possible to hear them from within and beyond the text, which, in Juan’s tattered volumes, has been redacted with black marker on nearly every page. As Juan waits for his end, he and the narrator recount for each other moments of joy and oblivion; they resurrect loves, lives, mothers, fathers, minor heroes. In telling their own stories and the story of the book, they resist the ravages of memory and time. The past is with us, beside us, ahead of us; what are we to create from its gaps and erasures?”

I was thinking about Torres’s choices here: to reconsider the place of both women and minorities in the archive of queer studies. Their lives and their histories have been typically marginalized and, in some cases, as this novel shows, co-opted entirely by other scientists and scholars. Torres seems to be interested in reminding us though that erasures create other erasures. If Jan Gay’s name is buried, so too is Juan’s presence as well, which leads us back to the presence of the narrator, who exists as a kind of younger foil to Juan, someone eager to discover the history of a kind of queer, BIPOC ancestor. I do not know if Torres found robust evidence of such figures in the archive, but the confluence of documents collected (whether fictionally generated or not) suggests that BIPOC individuals were typically objects of study. Thus, narrative provides Torres the apparatus to reconsider the centrality and psychic/emotional expansiveness in characters like Juan and the narrator, while also reminding us that the toil of existing on the margins is truly a madhouse that one is never guaranteed to survive.

Buy the Book Here

comments

comments

Published on May 21, 2024 11:08

A Review of Eddie Ahn’s Advocate (Ten Speed Graphic, 2024)

Posted by:

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) ccape

ccape

Written by Stephen Hong Sohn

Edited by Corinna Cape

Well, I know summer is on the way, because I’m starting to catch up on some reading and writing up some reviews. Let’s let the official marketing description get us situated with Eddie Ahn’s textured graphic memoir: “Born in Texas to Korean immigrants, Eddie grew up working at his family’s store with the weighty expectations that their sacrifices would be paid off when he achieved the ‘American Dream.’ Years later after moving to San Francisco and earning a coveted law degree, he then does the unthinkable: he rejects a lucrative legal career to enter the nonprofit world. In carving his own path, Eddie defies his family’s notions of economic success, igniting a struggle between family expectations, professional goals, and dreams of community. As an environmental justice attorney, he confronts the most immediate issues the country is facing today, from the devastating effects of Californian wildfires to economic inequality, all while combatting burnout and racial prejudice. In coming fully into his own, Eddie also reaches a hand back to his parents, showing them the value of a life of service rather than one spent only seeking monetary wealth. Weaving together humorous anecdotes with moments of victory and hope, this powerful, deeply contemplative full-color graphic novel explores the relationship between immigration and activism, opportunity and obligation, and familial duty and community service.”

I’m always looking for new material to add to my race and graphic narrative course; this one definitely fits the bill. What I especially love about this graphic narrative is the honesty with which Ahn is able to articulate the complications of parental expectations against his growing sense of ethics and duty. In this particular case, you can fully understand why his parents are driven so much by the importance of the money that Eddie can make. His parents’ business fails, and they end up divorcing. In the wake of these personal tribulations, Eddie’s career seems to be one of the few, clear bright spots, so he becomes the beacon of hope for the family at large. Of course, working at the intersections of social justice, nonprofits, and environmental law is not necessarily lucrative, so the Ahn’s text finds its rich foundation on this particular site of tension. Ahn’s professional trajectory is ultimately very intriguing and offers much in terms of the so-called “model minority narrative” and how it is finally subverted. Ahn’s artistic approach to the memoir is notable. He reminds me most of Tomine in the use of standard, geometric panels; his icons and images tend toward realism (rather than a cartoon-ish style), which is fitting for this work given the content. I always appreciate diving into a new graphic memoir, and this one is definitely a standout. Highly recommend!

Buy the Book Here

comments

comments

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) ccape

ccape

Written by Stephen Hong Sohn

Edited by Corinna Cape

Well, I know summer is on the way, because I’m starting to catch up on some reading and writing up some reviews. Let’s let the official marketing description get us situated with Eddie Ahn’s textured graphic memoir: “Born in Texas to Korean immigrants, Eddie grew up working at his family’s store with the weighty expectations that their sacrifices would be paid off when he achieved the ‘American Dream.’ Years later after moving to San Francisco and earning a coveted law degree, he then does the unthinkable: he rejects a lucrative legal career to enter the nonprofit world. In carving his own path, Eddie defies his family’s notions of economic success, igniting a struggle between family expectations, professional goals, and dreams of community. As an environmental justice attorney, he confronts the most immediate issues the country is facing today, from the devastating effects of Californian wildfires to economic inequality, all while combatting burnout and racial prejudice. In coming fully into his own, Eddie also reaches a hand back to his parents, showing them the value of a life of service rather than one spent only seeking monetary wealth. Weaving together humorous anecdotes with moments of victory and hope, this powerful, deeply contemplative full-color graphic novel explores the relationship between immigration and activism, opportunity and obligation, and familial duty and community service.”

I’m always looking for new material to add to my race and graphic narrative course; this one definitely fits the bill. What I especially love about this graphic narrative is the honesty with which Ahn is able to articulate the complications of parental expectations against his growing sense of ethics and duty. In this particular case, you can fully understand why his parents are driven so much by the importance of the money that Eddie can make. His parents’ business fails, and they end up divorcing. In the wake of these personal tribulations, Eddie’s career seems to be one of the few, clear bright spots, so he becomes the beacon of hope for the family at large. Of course, working at the intersections of social justice, nonprofits, and environmental law is not necessarily lucrative, so the Ahn’s text finds its rich foundation on this particular site of tension. Ahn’s professional trajectory is ultimately very intriguing and offers much in terms of the so-called “model minority narrative” and how it is finally subverted. Ahn’s artistic approach to the memoir is notable. He reminds me most of Tomine in the use of standard, geometric panels; his icons and images tend toward realism (rather than a cartoon-ish style), which is fitting for this work given the content. I always appreciate diving into a new graphic memoir, and this one is definitely a standout. Highly recommend!

Buy the Book Here

comments

comments

Published on May 21, 2024 10:59

January 29, 2024

A Review of Fonda Lee’s Untethered Sky (Tordotcom, 2023)

Posted by:

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) ljiang28

ljiang28

Written by Stephen Hong Sohn

Edited by Lina Jiang

Fonda Lee’s Untethered Sky (Tordotcom, 2023) was another one of my winter vacation reads. I saw the cover and thought it was probably about dragons. The design suggested high fantasy, and I’ve always been a high fantasy fan, having read things by David Eddings, Terry Goodkin, and Robert Jordan. I was right about the latter (in terms of the genre), but completely wrong about the former. The flying creatures I saw on the cover are actually rocs, which, for the uninitiated, are bird-like creatures commonly found in high fantasy works (a figure you might find in Dungeons and Dragons, for instance).

In any case, let’s let the marketing description give us more direction and context: “Ester’s family was torn apart when a manticore killed her mother and baby brother, leaving her with nothing but her father’s painful silence and a single, overwhelming need to kill the monsters that took her family. Ester’s path leads her to the King’s Royal Mews, where the giant rocs of legend are flown to hunt manticores by their brave and dedicated ruhkers. Paired with a fledgling roc named Zahra, Ester finds purpose and acclaim by devoting herself to a calling that demands absolute sacrifice and a creature that will never return her love. The terrifying partnership between woman and roc leads Ester not only on the empire’s most dangerous manticore hunt, but on a journey of perseverance and acceptance.”

You know, this description really does not reveal too much about the emotional core of the novel, so maybe I shouldn’t spoil that part, but what I absolutely loved about this novel is that it went in a direction that I thought was appropriate yet unsentimental. Lee sets up the monstrous antagonist quite well: the manticore is a villain that readers want to see vanquished. The creature seems to have a voracious appetite and rocs, though not necessarily as fearsome, are one of the few predators that have a chance of killing them. The fictional world also sets up the fact that manticore territory seems to be expanding, so the need for rukhers, the human handlers that are paired with rocs, are increasing. Given the extreme amount of trust required between rukhers and their rocs, the bond that the two beings eventually create is one that truly envelops the rukher, so much so that a rukher that loses their roc (either due to serious injuries in battle or old age) can become depressed or give up the calling entirely. The resolution of this slim little novella—and by the way, another selling point for this work, given that it can easily be read in one sitting—is again perfectly captured and reminds me of why I have always enjoyed Lee’s work. A master at plotting and character development, Lee always finds a way to draw you into whatever unique and dazzling fictional world she’s created. Pick this one up, while you enjoy a cup of hot cocoa, by your fire, or your radiator!

Buy the Book Here

comments

comments

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) ljiang28

ljiang28

Written by Stephen Hong Sohn

Edited by Lina Jiang

Fonda Lee’s Untethered Sky (Tordotcom, 2023) was another one of my winter vacation reads. I saw the cover and thought it was probably about dragons. The design suggested high fantasy, and I’ve always been a high fantasy fan, having read things by David Eddings, Terry Goodkin, and Robert Jordan. I was right about the latter (in terms of the genre), but completely wrong about the former. The flying creatures I saw on the cover are actually rocs, which, for the uninitiated, are bird-like creatures commonly found in high fantasy works (a figure you might find in Dungeons and Dragons, for instance).

In any case, let’s let the marketing description give us more direction and context: “Ester’s family was torn apart when a manticore killed her mother and baby brother, leaving her with nothing but her father’s painful silence and a single, overwhelming need to kill the monsters that took her family. Ester’s path leads her to the King’s Royal Mews, where the giant rocs of legend are flown to hunt manticores by their brave and dedicated ruhkers. Paired with a fledgling roc named Zahra, Ester finds purpose and acclaim by devoting herself to a calling that demands absolute sacrifice and a creature that will never return her love. The terrifying partnership between woman and roc leads Ester not only on the empire’s most dangerous manticore hunt, but on a journey of perseverance and acceptance.”

You know, this description really does not reveal too much about the emotional core of the novel, so maybe I shouldn’t spoil that part, but what I absolutely loved about this novel is that it went in a direction that I thought was appropriate yet unsentimental. Lee sets up the monstrous antagonist quite well: the manticore is a villain that readers want to see vanquished. The creature seems to have a voracious appetite and rocs, though not necessarily as fearsome, are one of the few predators that have a chance of killing them. The fictional world also sets up the fact that manticore territory seems to be expanding, so the need for rukhers, the human handlers that are paired with rocs, are increasing. Given the extreme amount of trust required between rukhers and their rocs, the bond that the two beings eventually create is one that truly envelops the rukher, so much so that a rukher that loses their roc (either due to serious injuries in battle or old age) can become depressed or give up the calling entirely. The resolution of this slim little novella—and by the way, another selling point for this work, given that it can easily be read in one sitting—is again perfectly captured and reminds me of why I have always enjoyed Lee’s work. A master at plotting and character development, Lee always finds a way to draw you into whatever unique and dazzling fictional world she’s created. Pick this one up, while you enjoy a cup of hot cocoa, by your fire, or your radiator!

Buy the Book Here

comments

comments

Published on January 29, 2024 12:43

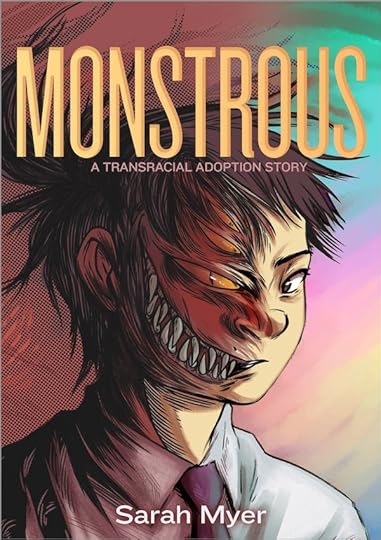

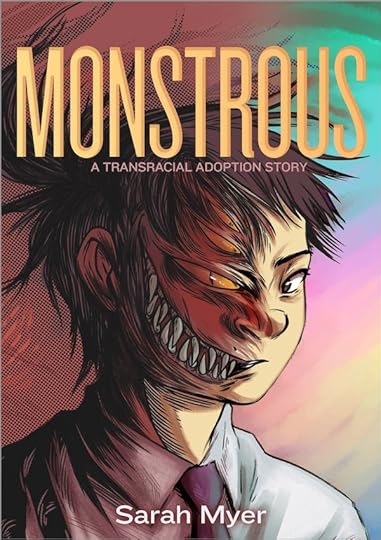

A Review of Sarah Myer’s Monstrous (First Second, 2023)

Posted by:

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) ljiang28

ljiang28

Written by Stephen Hong Sohn

Edited by Lina Jiang

Suffice it to say that I loved Sarah Myer’s Monstrous (First Second, 2023)—another one of my winter vacation reads—so much I actually reached out to the author via her website. Though I have yet to hear back and will likely not (given how many weeks have already gone by, sad face), this graphic narrative is definitely one I will add to the course I have taught in multiple iterations thus far called “Seeing Stories: Race and Graphic Narrative.” At Fordham University, I’ve already taught this course four separate times. Each time, I do try to add a new selection or two and sub out an equal number. Next time around, I will definitely add Monstrous!

The marketing description can be found here: “Monstrous is poignant young adult graphic memoir about a Korean-American girl who uses fandom and art-making to overcome racist bullying. Perfect for fans of Almost American Girl! Sarah has always struggled to fit in. Born in South Korea and adopted at birth by a white couple, she grows up in a rural community with few Asian neighbors. People whisper in the supermarket. Classmates bully her. She has trouble containing her anger in these moments—but through it all, she has her art. She's always been a compulsive drawer, and when she discovers anime, her hobby becomes an obsession. Though drawing and cosplay offer her an escape, she still struggles to connect with others. And in high school, the bullies are louder and meaner. Sarah's bubbling rage is threatening to burst.”

Despite all of this rage inside of her, Sarah continues to sort out her struggles with her racial identity and her artistic side, and the development of this particular character trajectory is hard-earned and heartwarming. By hard-earned, I mean to say that, in advance of teaching a book like this one, I would have to add a trigger warning. The amount of ridicule, bullying, and general bad energy that Sarah faces as a high school student was incredibly depressing to read. Just when you think she’s turned a corner, something else happens at school. I was most distressed at the lack of proper accountability that students were held to, on the one hand, and the almost universal lack of disciplining and oversight provided by adults in the educational system. To say that Sarah is a survivor is an understatement. Part of the reason that Sarah survives is that she never shies away from the power of art to be transformative for her. Of course, it helps a lot that her adoptive parents are so supportive of her unique talents and interests. In fact, I adored Sarah’s parents. One of the sequences in which Sarah’s father takes her to a local anime convention, where Sarah can cosplay and just meet other artists and creators was the moment I could breathe just for a second and know that she was finding a stable and secure path for herself. Of course, it wouldn’t be a graphic narrative review without images and art, and Sarah’s work is incredibly inviting, with shades of the anime she clearly was most drawn to as a child. The marketing description refers to Robin Ha, which certainly comes out a little bit in the similar ethnic contexts and artistic styles, but the plot of Monstrous specifically diverges in its focus on the Korean-American adoptees’ identity formation.

Buy the Book Here

comments

comments

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) ljiang28

ljiang28

Written by Stephen Hong Sohn

Edited by Lina Jiang

Suffice it to say that I loved Sarah Myer’s Monstrous (First Second, 2023)—another one of my winter vacation reads—so much I actually reached out to the author via her website. Though I have yet to hear back and will likely not (given how many weeks have already gone by, sad face), this graphic narrative is definitely one I will add to the course I have taught in multiple iterations thus far called “Seeing Stories: Race and Graphic Narrative.” At Fordham University, I’ve already taught this course four separate times. Each time, I do try to add a new selection or two and sub out an equal number. Next time around, I will definitely add Monstrous!

The marketing description can be found here: “Monstrous is poignant young adult graphic memoir about a Korean-American girl who uses fandom and art-making to overcome racist bullying. Perfect for fans of Almost American Girl! Sarah has always struggled to fit in. Born in South Korea and adopted at birth by a white couple, she grows up in a rural community with few Asian neighbors. People whisper in the supermarket. Classmates bully her. She has trouble containing her anger in these moments—but through it all, she has her art. She's always been a compulsive drawer, and when she discovers anime, her hobby becomes an obsession. Though drawing and cosplay offer her an escape, she still struggles to connect with others. And in high school, the bullies are louder and meaner. Sarah's bubbling rage is threatening to burst.”

Despite all of this rage inside of her, Sarah continues to sort out her struggles with her racial identity and her artistic side, and the development of this particular character trajectory is hard-earned and heartwarming. By hard-earned, I mean to say that, in advance of teaching a book like this one, I would have to add a trigger warning. The amount of ridicule, bullying, and general bad energy that Sarah faces as a high school student was incredibly depressing to read. Just when you think she’s turned a corner, something else happens at school. I was most distressed at the lack of proper accountability that students were held to, on the one hand, and the almost universal lack of disciplining and oversight provided by adults in the educational system. To say that Sarah is a survivor is an understatement. Part of the reason that Sarah survives is that she never shies away from the power of art to be transformative for her. Of course, it helps a lot that her adoptive parents are so supportive of her unique talents and interests. In fact, I adored Sarah’s parents. One of the sequences in which Sarah’s father takes her to a local anime convention, where Sarah can cosplay and just meet other artists and creators was the moment I could breathe just for a second and know that she was finding a stable and secure path for herself. Of course, it wouldn’t be a graphic narrative review without images and art, and Sarah’s work is incredibly inviting, with shades of the anime she clearly was most drawn to as a child. The marketing description refers to Robin Ha, which certainly comes out a little bit in the similar ethnic contexts and artistic styles, but the plot of Monstrous specifically diverges in its focus on the Korean-American adoptees’ identity formation.

Buy the Book Here

comments

comments

Published on January 29, 2024 12:29

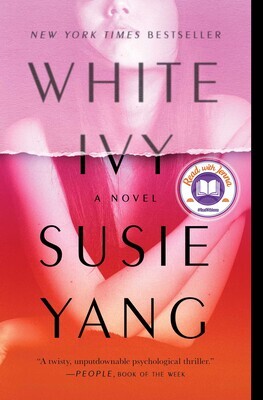

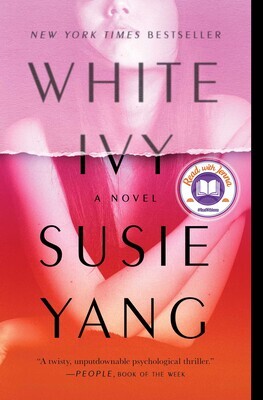

A Review of Susie Yang’s White Ivy (S&S/ Marysue Rucci Books, 2020).

Posted by:

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) ljiang28

ljiang28

Written by Stephen Hong Sohn

Edited by Lina Jiang

Ah, Susie Yang’s White Ivy (S&S/ Marysue Rucci Books, 2020) may be one of the most surprising winter vacation reads. This title had been on my shelf for some time, as I’d lost where it was put during the cross-country move. When I found it one day, I thought it was a sign to crack it open. I’m so glad that I did! I didn’t expect to enjoy this novel so much, given that the protagonist was not my cup of tea.

Let’s let the official marketing description do some work for us: “Ivy Lin is a thief and a liar—but you’d never know it by looking at her. Raised outside of Boston, Ivy’s immigrant grandmother relies on Ivy’s mild appearance for cover as she teaches her granddaughter how to pilfer items from yard sales and second-hand shops. Thieving allows Ivy to accumulate the trappings of a suburban teen—and, most importantly, to attract the attention of Gideon Speyer, the golden boy of a wealthy political family. But when Ivy’s mother discovers her trespasses, punishment is swift and Ivy is sent to China, and her dream instantly evaporates. Years later, Ivy has grown into a poised yet restless young woman, haunted by her conflicting feelings about her upbringing and her family. Back in Boston, when Ivy bumps into Sylvia Speyer, Gideon’s sister, a reconnection with Gideon seems not only inevitable—it feels like fate. Slowly, Ivy sinks her claws into Gideon and the entire Speyer clan by attending fancy dinners, and weekend getaways to the cape. But just as Ivy is about to have everything she’s ever wanted, a ghost from her past resurfaces, threatening the nearly perfect life she’s worked so hard to build.”

The ghost from her past that the description doesn’t cover is part of the key love triangle that develops: this man is someone Ivy also grew up with, but closer to her own class backgrounds. By the time, this individual has grown up, and he has amassed a small fortune, enough to keep Ivy interested in him, while she also pursues Gideon. The complication, of course, is that Gideon has no idea about Ivy’s other man. Ivy is a very complicated character: she is an inveterate social climber, on the one hand, yet she also seeks to have a deep romantic connection to her partner, on the other. Though Gideon looks perfect on paper, their relationship stalls in the physical department, thus leaving the door open for Ivy to look elsewhere. Yang has some big surprises for readers as the novel hurtles toward its dark tragicomic conclusion, and I found myself absolutely riveted in wondering what choices Ivy would ultimately make when it seems that the house of cards she had built for herself had finally fallen. With its tense plot and an unforgettable protagonist you will probably come to love or hate, this debut is the kind I’d recommend to any reader.

Buy the Book Here

comments

comments

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) ljiang28

ljiang28

Written by Stephen Hong Sohn

Edited by Lina Jiang

Ah, Susie Yang’s White Ivy (S&S/ Marysue Rucci Books, 2020) may be one of the most surprising winter vacation reads. This title had been on my shelf for some time, as I’d lost where it was put during the cross-country move. When I found it one day, I thought it was a sign to crack it open. I’m so glad that I did! I didn’t expect to enjoy this novel so much, given that the protagonist was not my cup of tea.

Let’s let the official marketing description do some work for us: “Ivy Lin is a thief and a liar—but you’d never know it by looking at her. Raised outside of Boston, Ivy’s immigrant grandmother relies on Ivy’s mild appearance for cover as she teaches her granddaughter how to pilfer items from yard sales and second-hand shops. Thieving allows Ivy to accumulate the trappings of a suburban teen—and, most importantly, to attract the attention of Gideon Speyer, the golden boy of a wealthy political family. But when Ivy’s mother discovers her trespasses, punishment is swift and Ivy is sent to China, and her dream instantly evaporates. Years later, Ivy has grown into a poised yet restless young woman, haunted by her conflicting feelings about her upbringing and her family. Back in Boston, when Ivy bumps into Sylvia Speyer, Gideon’s sister, a reconnection with Gideon seems not only inevitable—it feels like fate. Slowly, Ivy sinks her claws into Gideon and the entire Speyer clan by attending fancy dinners, and weekend getaways to the cape. But just as Ivy is about to have everything she’s ever wanted, a ghost from her past resurfaces, threatening the nearly perfect life she’s worked so hard to build.”

The ghost from her past that the description doesn’t cover is part of the key love triangle that develops: this man is someone Ivy also grew up with, but closer to her own class backgrounds. By the time, this individual has grown up, and he has amassed a small fortune, enough to keep Ivy interested in him, while she also pursues Gideon. The complication, of course, is that Gideon has no idea about Ivy’s other man. Ivy is a very complicated character: she is an inveterate social climber, on the one hand, yet she also seeks to have a deep romantic connection to her partner, on the other. Though Gideon looks perfect on paper, their relationship stalls in the physical department, thus leaving the door open for Ivy to look elsewhere. Yang has some big surprises for readers as the novel hurtles toward its dark tragicomic conclusion, and I found myself absolutely riveted in wondering what choices Ivy would ultimately make when it seems that the house of cards she had built for herself had finally fallen. With its tense plot and an unforgettable protagonist you will probably come to love or hate, this debut is the kind I’d recommend to any reader.

Buy the Book Here

comments

comments

Published on January 29, 2024 12:04

January 28, 2024

A Review of Beth Nguyen’s Owner of a Lonely Heart (Scribner, 2023)

Posted by:

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) ccape

ccape

Written by Stephen Hong Sohn

Edited by Corinna Cape

*reviewer’s note: In my aim to cover as much ground and texts as I can, I’m focusing on shorter lightning reviews that get to the gist of my reading experience! As Asian American literature has boomed, my time to read this exponentially growing archive has only diminished. I will do my best, as always!

Beth Nguyen’s Owner of a Lonely Heart (Scribner, 2023) was part of my winter break vacation reading. At first, I didn’t even realize that Beth is quite the well-known writer, although I’ve read both of her prior novels and memoir. Indeed, Beth, who has published under the name Bich Minh Nguyen, makes a major change to her publication moniker in her latest work. I will speak on that issue later, but I will provide you with the marketing description, as per usual: “At the end of the Vietnam War, when Beth Nguyen was eight months old, she and her family fled Saigon for America. Only Beth’s mother stayed—or was left—behind, and they did not meet again until Beth was nineteen. Over the course of her adult life, she and her mother have spent less than twenty-four hours together. Owner of a Lonely Heart is ‘a portrait of things left unsaid’ (The New York Times), a memoir about parenthood, absence, and the condition of being a refugee: the story of Beth’s relationship with her mother. Framed by a handful of visits over the course of many years—sometimes brief, sometimes interrupted, some alone with her mother and others with the company of her sister—Beth tells an ‘unforgettable’ (People) coming-of-age story that spans her childhood in the Midwest, her first meeting with her mother, and her own experience of parenthood.”

This read was a difficult one, as we get into the complicated family dynamics that Beth faces mostly in relation to her biological mother. They often remain at an arm’s distance from each other, but Nguyen continually finds herself drawn back into her mother’s orbit. It’s interesting to see how Nguyen outlines the different responses between herself and her sister. Nguyen’s sister tends to put a little bit more distance between herself and their biological mother, while Nguyen incessantly seeks her out, despite the often uneven interactions they have. Nguyen also explains the shift in her publication name, as “Beth” is a name that she has often used growing up and well into her adulthood, especially because “Bich” has been such a problem for her as a child and as a racial minority having lived in many areas that are not very diverse. Perhaps, the most incredible aspect of this memoir is a conscientious act of withholding. The readers know well by the concluding pages that Nguyen is desperately seeking more information about her mother, how her mother came to know her father, and how her mother truly fell out of their lives. The conversations up to the end of the memoir are stilted, oblique, filled with absences. Finally, there is a breakthrough, but Nguyen chooses not to detail any of it, to keep it in the realm of private utterance. I’ve been thinking a lot about how the memoir as a form tends to expect forms of transparency and even expansive vulnerability, as personal details are shared to a reading audience often filled with strangers. Nguyen’s choice thus felt incredibly appropriate, a climactic un-reveal that gets at the heart of memoir’s complicated nature of utterance and revelation. We are waiting for that information, but never get it, and we understand that we should not have it. It is in this sense that Nguyen’s memoir truly soars.

Buy the Book Here

comments

comments

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) ccape

ccape

Written by Stephen Hong Sohn

Edited by Corinna Cape

*reviewer’s note: In my aim to cover as much ground and texts as I can, I’m focusing on shorter lightning reviews that get to the gist of my reading experience! As Asian American literature has boomed, my time to read this exponentially growing archive has only diminished. I will do my best, as always!

Beth Nguyen’s Owner of a Lonely Heart (Scribner, 2023) was part of my winter break vacation reading. At first, I didn’t even realize that Beth is quite the well-known writer, although I’ve read both of her prior novels and memoir. Indeed, Beth, who has published under the name Bich Minh Nguyen, makes a major change to her publication moniker in her latest work. I will speak on that issue later, but I will provide you with the marketing description, as per usual: “At the end of the Vietnam War, when Beth Nguyen was eight months old, she and her family fled Saigon for America. Only Beth’s mother stayed—or was left—behind, and they did not meet again until Beth was nineteen. Over the course of her adult life, she and her mother have spent less than twenty-four hours together. Owner of a Lonely Heart is ‘a portrait of things left unsaid’ (The New York Times), a memoir about parenthood, absence, and the condition of being a refugee: the story of Beth’s relationship with her mother. Framed by a handful of visits over the course of many years—sometimes brief, sometimes interrupted, some alone with her mother and others with the company of her sister—Beth tells an ‘unforgettable’ (People) coming-of-age story that spans her childhood in the Midwest, her first meeting with her mother, and her own experience of parenthood.”

This read was a difficult one, as we get into the complicated family dynamics that Beth faces mostly in relation to her biological mother. They often remain at an arm’s distance from each other, but Nguyen continually finds herself drawn back into her mother’s orbit. It’s interesting to see how Nguyen outlines the different responses between herself and her sister. Nguyen’s sister tends to put a little bit more distance between herself and their biological mother, while Nguyen incessantly seeks her out, despite the often uneven interactions they have. Nguyen also explains the shift in her publication name, as “Beth” is a name that she has often used growing up and well into her adulthood, especially because “Bich” has been such a problem for her as a child and as a racial minority having lived in many areas that are not very diverse. Perhaps, the most incredible aspect of this memoir is a conscientious act of withholding. The readers know well by the concluding pages that Nguyen is desperately seeking more information about her mother, how her mother came to know her father, and how her mother truly fell out of their lives. The conversations up to the end of the memoir are stilted, oblique, filled with absences. Finally, there is a breakthrough, but Nguyen chooses not to detail any of it, to keep it in the realm of private utterance. I’ve been thinking a lot about how the memoir as a form tends to expect forms of transparency and even expansive vulnerability, as personal details are shared to a reading audience often filled with strangers. Nguyen’s choice thus felt incredibly appropriate, a climactic un-reveal that gets at the heart of memoir’s complicated nature of utterance and revelation. We are waiting for that information, but never get it, and we understand that we should not have it. It is in this sense that Nguyen’s memoir truly soars.

Buy the Book Here

comments

comments

Published on January 28, 2024 15:44

A Review of Jen Soriano’s Nervous: Essays on Heritage and Healing (Amistad, 2023)

Posted by:

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) ccape

ccape

Written by Stephen Hong Sohn

Edited by Corinna Cape

*reviewer’s note: In my aim to cover as much ground and texts as I can, I’m focusing on shorter lightning reviews that get to the gist of my reading experience! As Asian American literature has boomed, my time to read this exponentially growing archive has only diminished. I will do my best, as always!

Ah, dear fellow book lovers. It is such an exciting time to be delving into Asian American literature. Clear evidence of the broad plasticity and depth of this field is shown in Jen Soriano’s Nervous: Essays on Heritage and Healing (Amistad, 2023), which revels in the expansiveness enabled by a genre such as the essay. Let’s let the official marketing description get us off the ground: “The power of quiet can haunt us over generations, crystallizing in pain that Jen Soriano views as a form of embodied history. In this searing memoir in essays, Soriano, the daughter of a neurosurgeon, journeys to understand the origins of her chronic pain and mental health struggles. By the end, she finds both the source and the delta of what bodies impacted by trauma might need to thrive. In fourteen essays connected by theme and experience, Soriano traverses centuries and continents, weaving together memory and history, sociology and personal stories, neuroscience and public health, into a vivid tapestry of what it takes to transform trauma not just body by body, but through the body politic and ecosystems at large. Beginning with a shocking timeline juxtaposing Soriano’s medical history with the history of hysteria and witch hunts, Nervous navigates the human body—centering neurodiverse, disabled, and genderqueer bodies of color—within larger systems that have harmed and silenced Filipinos for generations. Soriano’s wide-ranging essays contemplate the Spanish-American War that ushered in United States colonization in the Philippines; the healing power of an inherited legacy of music; a chosen family of activists from the Bay Area to the Philippines; and how the fluidity of our nervous systems can teach us how to shape a trauma-wise future.”

The essential thesis of this text is that Soriano’s chronic pain and mental health issues cannot be seen as purely physiological. Soriano dives deeply into still-debated understandings of epigenetics and intergenerational trauma. What’s interesting about this text is that it begins to open up the conversation about how memory and trauma end up affecting certain forms of gene expression over time. The more complicated question that the essays cannot yet answer and is perhaps evident of the need for more scientific studies is the way in which certain bodies become more sensitive to these intergenerational expressions of trauma. Soriano ultimately makes the claim that things like colonial domination can affect one’s life multiple centuries later, but the large question looms: why is it that certain individuals are more likely to exhibit and manifest these latent forms of trauma? Despite the fact that this question is not fully answered, what I have found so compelling about these essays is the way in which they drive the individual afflicted into a kind of detective quest: to seek out answers, to outline the social contexts in which trauma is produced, and to take control of the narrative that concerns their own body and how it may express pain. For Soriano, her body’s constant state of pain pushes her to look into the histories of her family, but it also encourages her to look into activist efforts produced by and animated through the work of so many others in the quest for social justice. In this way, there is something absolutely agential and powerful about acknowledging what intergenerational trauma does to the body, despite the fact that it can be so debilitating.

Buy the Book Here

comments

comments

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) ccape

ccape

Written by Stephen Hong Sohn

Edited by Corinna Cape

*reviewer’s note: In my aim to cover as much ground and texts as I can, I’m focusing on shorter lightning reviews that get to the gist of my reading experience! As Asian American literature has boomed, my time to read this exponentially growing archive has only diminished. I will do my best, as always!

Ah, dear fellow book lovers. It is such an exciting time to be delving into Asian American literature. Clear evidence of the broad plasticity and depth of this field is shown in Jen Soriano’s Nervous: Essays on Heritage and Healing (Amistad, 2023), which revels in the expansiveness enabled by a genre such as the essay. Let’s let the official marketing description get us off the ground: “The power of quiet can haunt us over generations, crystallizing in pain that Jen Soriano views as a form of embodied history. In this searing memoir in essays, Soriano, the daughter of a neurosurgeon, journeys to understand the origins of her chronic pain and mental health struggles. By the end, she finds both the source and the delta of what bodies impacted by trauma might need to thrive. In fourteen essays connected by theme and experience, Soriano traverses centuries and continents, weaving together memory and history, sociology and personal stories, neuroscience and public health, into a vivid tapestry of what it takes to transform trauma not just body by body, but through the body politic and ecosystems at large. Beginning with a shocking timeline juxtaposing Soriano’s medical history with the history of hysteria and witch hunts, Nervous navigates the human body—centering neurodiverse, disabled, and genderqueer bodies of color—within larger systems that have harmed and silenced Filipinos for generations. Soriano’s wide-ranging essays contemplate the Spanish-American War that ushered in United States colonization in the Philippines; the healing power of an inherited legacy of music; a chosen family of activists from the Bay Area to the Philippines; and how the fluidity of our nervous systems can teach us how to shape a trauma-wise future.”

The essential thesis of this text is that Soriano’s chronic pain and mental health issues cannot be seen as purely physiological. Soriano dives deeply into still-debated understandings of epigenetics and intergenerational trauma. What’s interesting about this text is that it begins to open up the conversation about how memory and trauma end up affecting certain forms of gene expression over time. The more complicated question that the essays cannot yet answer and is perhaps evident of the need for more scientific studies is the way in which certain bodies become more sensitive to these intergenerational expressions of trauma. Soriano ultimately makes the claim that things like colonial domination can affect one’s life multiple centuries later, but the large question looms: why is it that certain individuals are more likely to exhibit and manifest these latent forms of trauma? Despite the fact that this question is not fully answered, what I have found so compelling about these essays is the way in which they drive the individual afflicted into a kind of detective quest: to seek out answers, to outline the social contexts in which trauma is produced, and to take control of the narrative that concerns their own body and how it may express pain. For Soriano, her body’s constant state of pain pushes her to look into the histories of her family, but it also encourages her to look into activist efforts produced by and animated through the work of so many others in the quest for social justice. In this way, there is something absolutely agential and powerful about acknowledging what intergenerational trauma does to the body, despite the fact that it can be so debilitating.

Buy the Book Here

comments

comments

Published on January 28, 2024 15:33

A Review of Johanna Hedva’s Your Love is Not Good (And Other Stories, 2023)

Posted by:

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) ccape

ccape

Written by Stephen Hong Sohn

Edited by Corinna Cape

*reviewer’s note: In my aim to cover as much ground and texts as I can, I’m focusing on shorter lightning reviews that get to the gist of my reading experience! As Asian American literature has boomed, my time to read this exponentially growing archive has only diminished. I will do my best, as always!

Well, if there was any novel that is the narrative embodiment of Lady Gaga’s “Bad Romance,” then it is Johanna Hedva’s Your Love is Not Good (And Other Stories, 2023). Let’s let the description at the official publisher’s website give us some much-needed grounding: “At an otherwise forgettable party in Los Angeles, a queer Korean American painter spots a woman who instantly controls the room: gorgeous and distant and utterly white, the centre of everyone’s attention. Haunted into adulthood by her Korean father’s abandonment of his family, as well as the spectre of her beguiling, abusive white mother, the painter finds herself caught in a perfect trap. She wants Hanne, or wants to be her, or to sully her, or destroy her, or consume her, or some confusion of all the above. Since she’s an artist, she will use art to get closer to Hanne, beginning a series of paintings with her new muse as model. As for Hanne, what does she want? Her whiteness seems sometimes as cruel as a new sheet of paper. When the paintings of Hanne become a hit, resulting in the artist’s first sold-out show, she resolves to bring her new muse with her to Berlin, to continue their work, and her seduction. But, just when the painter is on the verge of her long sought-after breakthrough, a petition started by a Black performance artist begins making the rounds in the art community, calling for the boycott of major museums and art galleries for their imperialist and racist practices. Torn between her desire to support the petition, to be a success, and to possess Hanne, the painter and her reality become more unstable and disorienting, unwilling to cut loose any one of her warring ambitions, yet unable to accommodate them all. Is it any wonder so many artists self-destruct so spectacularly? Is it perhaps just a bit exciting to think she could too?”

This description is quite robust and actually brings readers up to speed in relation to 2/3 of the novel’s plot. What this summary doesn’t fully convey is the intriguing formal dynamics of the novel, which involve vignette-esque chapters that always begin with an art-based heading. The heading typically references some sort of painting technique or style (e.g. chiaroscuro, tenebrism, impasto, etc), which reminds us that we’re in the specific and rarefied world of artistic production. Perhaps the element that I was most impressed with was Hedva’s incredibly immersive first-person narrator. Hedva’s protagonist is one willing to admit her faults, her obsessions, and many of her most intimate habits. In this respect, we get quite the complicated and textured psychological view of a character who is slowly unraveling. There is a point in the text when the narrator receives a significant head injury, which occurs in a period of time when her artistic future may be in jeopardy. After that incident, I wasn’t quite sure what was going on, as the narrative includes some surrealistic moments in which I began to question the reliability of the storyteller. As Hedva seems to be drawing out, this protagonist has a sadomasochistic relationship not only to others but to art, but the question is whether or not this relationship is fully toxic. The title, which at first seems directed toward the narrator’s relationship to Hanne, might actually be reframed as the distorted parenting which she has received, and which is “not good” for the constitution of her identity over time. Another element of this text that was illuminating concerns the multifaceted relationship between gallerists, artists, and museums. I didn’t realize that an artist could be in that kind of debt—the narrator is hundreds of thousands of dollars in the hole from her various art degrees and contracts—and then could walk into a working relationship with a gallerist, knowing that she would be working overtime with the hopes that her work would eventually sell so that she would be able to cover some of what was owed. Finally, perhaps, the most philosophical element that Hedva ingeniously threads through is the discourse of race as it pertains to art. Since the narrator and many of her friends occasionally produce art that borders on the abstract, the question then becomes: where is race in this work? Should race be at all understood as a framing mechanism for the minority artist? Such questions continually animate multiple narrative sequences, giving readers much to chew on in relation to authorial ancestry and its impact on the way we read artistic production. A truly distinctive novel with an equally singular narrative perspective.

Buy the Book Here

comments

comments

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) ccape

ccape

Written by Stephen Hong Sohn

Edited by Corinna Cape

*reviewer’s note: In my aim to cover as much ground and texts as I can, I’m focusing on shorter lightning reviews that get to the gist of my reading experience! As Asian American literature has boomed, my time to read this exponentially growing archive has only diminished. I will do my best, as always!

Well, if there was any novel that is the narrative embodiment of Lady Gaga’s “Bad Romance,” then it is Johanna Hedva’s Your Love is Not Good (And Other Stories, 2023). Let’s let the description at the official publisher’s website give us some much-needed grounding: “At an otherwise forgettable party in Los Angeles, a queer Korean American painter spots a woman who instantly controls the room: gorgeous and distant and utterly white, the centre of everyone’s attention. Haunted into adulthood by her Korean father’s abandonment of his family, as well as the spectre of her beguiling, abusive white mother, the painter finds herself caught in a perfect trap. She wants Hanne, or wants to be her, or to sully her, or destroy her, or consume her, or some confusion of all the above. Since she’s an artist, she will use art to get closer to Hanne, beginning a series of paintings with her new muse as model. As for Hanne, what does she want? Her whiteness seems sometimes as cruel as a new sheet of paper. When the paintings of Hanne become a hit, resulting in the artist’s first sold-out show, she resolves to bring her new muse with her to Berlin, to continue their work, and her seduction. But, just when the painter is on the verge of her long sought-after breakthrough, a petition started by a Black performance artist begins making the rounds in the art community, calling for the boycott of major museums and art galleries for their imperialist and racist practices. Torn between her desire to support the petition, to be a success, and to possess Hanne, the painter and her reality become more unstable and disorienting, unwilling to cut loose any one of her warring ambitions, yet unable to accommodate them all. Is it any wonder so many artists self-destruct so spectacularly? Is it perhaps just a bit exciting to think she could too?”

This description is quite robust and actually brings readers up to speed in relation to 2/3 of the novel’s plot. What this summary doesn’t fully convey is the intriguing formal dynamics of the novel, which involve vignette-esque chapters that always begin with an art-based heading. The heading typically references some sort of painting technique or style (e.g. chiaroscuro, tenebrism, impasto, etc), which reminds us that we’re in the specific and rarefied world of artistic production. Perhaps the element that I was most impressed with was Hedva’s incredibly immersive first-person narrator. Hedva’s protagonist is one willing to admit her faults, her obsessions, and many of her most intimate habits. In this respect, we get quite the complicated and textured psychological view of a character who is slowly unraveling. There is a point in the text when the narrator receives a significant head injury, which occurs in a period of time when her artistic future may be in jeopardy. After that incident, I wasn’t quite sure what was going on, as the narrative includes some surrealistic moments in which I began to question the reliability of the storyteller. As Hedva seems to be drawing out, this protagonist has a sadomasochistic relationship not only to others but to art, but the question is whether or not this relationship is fully toxic. The title, which at first seems directed toward the narrator’s relationship to Hanne, might actually be reframed as the distorted parenting which she has received, and which is “not good” for the constitution of her identity over time. Another element of this text that was illuminating concerns the multifaceted relationship between gallerists, artists, and museums. I didn’t realize that an artist could be in that kind of debt—the narrator is hundreds of thousands of dollars in the hole from her various art degrees and contracts—and then could walk into a working relationship with a gallerist, knowing that she would be working overtime with the hopes that her work would eventually sell so that she would be able to cover some of what was owed. Finally, perhaps, the most philosophical element that Hedva ingeniously threads through is the discourse of race as it pertains to art. Since the narrator and many of her friends occasionally produce art that borders on the abstract, the question then becomes: where is race in this work? Should race be at all understood as a framing mechanism for the minority artist? Such questions continually animate multiple narrative sequences, giving readers much to chew on in relation to authorial ancestry and its impact on the way we read artistic production. A truly distinctive novel with an equally singular narrative perspective.

Buy the Book Here

comments

comments

Published on January 28, 2024 15:20

November 7, 2023

A Review of Neel Patel’s Tell Me How to Be (Flatiron, 2021)

Posted by:

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) ccape

ccape

Written by Stephen Hong Sohn

Edited by Corinna Cape

I had meant to read this book long ago, but I actually lost it in a cross-country move. I eventually got my hands on another copy, so I can rectify my oversight. Neel Patel’s Tell Me How to Be (Flatiron, 2021) is one of those books that I would have written on awhile back had it come out sooner. The novel is especially important because it reminds us of the complicated contours of the queer Asian American experience, especially in relation to transnational dynamics and family formations. Let’s let B&N give us more context: “Renu Amin always seemed perfect. But as the one-year anniversary of her husband’s death approaches, she is binge-watching soap operas and simmering with old resentments. She can’t stop wondering if, thirty-five years ago, she chose the wrong life. In Los Angeles, her son, Akash, has everything he ever wanted, but he is haunted by the painful memories he fled a decade ago. When his mother tells him she is selling the family home, Akash returns to Illinois, hoping to finally say goodbye and move on. Together, Renu and Akash pack up the house, retreating further into the secrets that stand between them. Renu sends an innocent Facebook message to the man she almost married, sparking an emotional affair that calls into question everything she thought she knew about herself. Akash slips back into bad habits as he confronts his darkest secrets—including what really happened between him and the first boy who broke his heart. When their pasts catch up to them, Renu and Akash must decide between the lives they left behind and the ones they’ve since created, between making each other happy and setting themselves free. By turns irreverent and tender, filled with the beats of ’90s R&B, Tell Me How to Be is about our earliest betrayals and the cost of reconciliation. But most of all, it is the love story of a mother and son each trying to figure out how to be in the world.”

This particular description is fairly robust, and I don’t need to add too much more general information. The one thing that it really misses is the interesting discursive mode, as Patel chooses to use alternating first person perspectives, shifting between the aforementioned Renu and Akash. I’m always a huge fan of the first person, but Patel doesn’t necessarily give you characters that you can just sit by and observe. Indeed, I read Patel’s story collection, If You See Me, Don’t Say Hi, and Patel always retains these fairly strident first person perspectives. These characters are fully formed and exhibit both strengths and major flaws, so they can be a lot. This novel is no different. For instance, Akash is pretty messy: he has some substance abuse problems, he’s pretty flaky, he’s broke, and he keeps a lot of secrets. While Akash’s mother clearly has more of her life put together, she has her own issues, living in an area with a majority-white community and the fact that she is grappling with a major move to London. Renu has her own secret as well, so you might conceive of this novel as one involving comparative “closets,” with Akash being queer and his mother having a still-burning love for a Muslim man in her past. The novel works best as Patel’s incisive indictment of transnational Asian American parents, who no doubt have many things that they keep from their children. The novel unmasks the hypocrisy potentially existing within the Asian American parental structure, which can produce heteronormative relationship standards that are not only destructive but do not acknowledge relational forms of queerness existing even in seemingly heterosexual relationships. On the level of plot, the novel occasionally suffers from periodic dips in momentum, but Patel ultimately knows that what progresses the narrative is the dissonant and synergistic nature of these various relationships.

Buy the Book Here

comments

comments

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) ccape

ccape

Written by Stephen Hong Sohn

Edited by Corinna Cape

I had meant to read this book long ago, but I actually lost it in a cross-country move. I eventually got my hands on another copy, so I can rectify my oversight. Neel Patel’s Tell Me How to Be (Flatiron, 2021) is one of those books that I would have written on awhile back had it come out sooner. The novel is especially important because it reminds us of the complicated contours of the queer Asian American experience, especially in relation to transnational dynamics and family formations. Let’s let B&N give us more context: “Renu Amin always seemed perfect. But as the one-year anniversary of her husband’s death approaches, she is binge-watching soap operas and simmering with old resentments. She can’t stop wondering if, thirty-five years ago, she chose the wrong life. In Los Angeles, her son, Akash, has everything he ever wanted, but he is haunted by the painful memories he fled a decade ago. When his mother tells him she is selling the family home, Akash returns to Illinois, hoping to finally say goodbye and move on. Together, Renu and Akash pack up the house, retreating further into the secrets that stand between them. Renu sends an innocent Facebook message to the man she almost married, sparking an emotional affair that calls into question everything she thought she knew about herself. Akash slips back into bad habits as he confronts his darkest secrets—including what really happened between him and the first boy who broke his heart. When their pasts catch up to them, Renu and Akash must decide between the lives they left behind and the ones they’ve since created, between making each other happy and setting themselves free. By turns irreverent and tender, filled with the beats of ’90s R&B, Tell Me How to Be is about our earliest betrayals and the cost of reconciliation. But most of all, it is the love story of a mother and son each trying to figure out how to be in the world.”

This particular description is fairly robust, and I don’t need to add too much more general information. The one thing that it really misses is the interesting discursive mode, as Patel chooses to use alternating first person perspectives, shifting between the aforementioned Renu and Akash. I’m always a huge fan of the first person, but Patel doesn’t necessarily give you characters that you can just sit by and observe. Indeed, I read Patel’s story collection, If You See Me, Don’t Say Hi, and Patel always retains these fairly strident first person perspectives. These characters are fully formed and exhibit both strengths and major flaws, so they can be a lot. This novel is no different. For instance, Akash is pretty messy: he has some substance abuse problems, he’s pretty flaky, he’s broke, and he keeps a lot of secrets. While Akash’s mother clearly has more of her life put together, she has her own issues, living in an area with a majority-white community and the fact that she is grappling with a major move to London. Renu has her own secret as well, so you might conceive of this novel as one involving comparative “closets,” with Akash being queer and his mother having a still-burning love for a Muslim man in her past. The novel works best as Patel’s incisive indictment of transnational Asian American parents, who no doubt have many things that they keep from their children. The novel unmasks the hypocrisy potentially existing within the Asian American parental structure, which can produce heteronormative relationship standards that are not only destructive but do not acknowledge relational forms of queerness existing even in seemingly heterosexual relationships. On the level of plot, the novel occasionally suffers from periodic dips in momentum, but Patel ultimately knows that what progresses the narrative is the dissonant and synergistic nature of these various relationships.

Buy the Book Here

comments

comments

Published on November 07, 2023 07:28