Stephen Hong Sohn's Blog, page 32

February 3, 2020

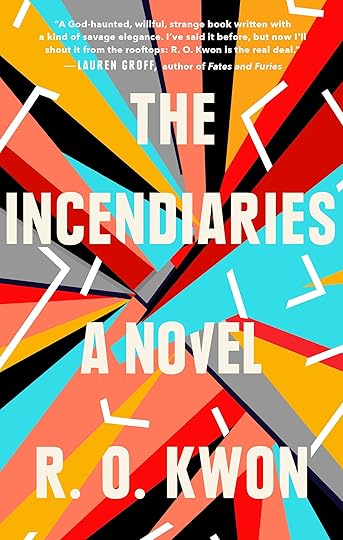

A Review of R.O. Kwon’s The Incendiaries (Riverheard Hardcover, 2018)

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) lesliejfernandez

lesliejfernandez

A Review of R.O. Kwon’s The Incendiaries (Riverheard Hardcover, 2018).

By Stephen Hong Sohn

I had a false start with this novel sometime last year. It is R.O. Kwon’s absolutely stunningly written debut called The Incendiaries (Riverhead, 2019). I was having trouble getting into the narrative discourse, partly I think because there are three fairly distinct narrative perspectives.

The first is given to a man named Will; he has lost his faith and seems to be seeking a new sense of life’s purpose. This narrative perspective is given in the first person. The second is given to Phoebe Lin. This particular narrative perspective was the weirdest to me. It seems to be related to the fact that Phoebe has joined an organization, which we later realize is more likely a cult, and that Phoebe is in the process of a kind of public confession. Thus, Phoebe’s sections are almost like monologue, except for the fact that there are occasional moments where you realize that the section is really being told in the third person, with a very distant narrator. The final narrative perspective is a more standard third, with brief snippets that give us the background of John Leal, the leader of the cultish organization in which Phoebe gets entangled.

I was later listening to a podcast where you get a sense of Kwon’s motivations in terms of the narrative discourse. She makes a really interesting observation that she found it easier to tell the story once she gave the primary narrative perspective to a character that wasn’t a part of much of the direct action. Indeed, Will’s not really the protagonist. Everything centers around and is really about Phoebe and her past. Will’s an incredibly astute and sensitive observer, so his narrative sections really allow the novel to shine brightly. The sections with Phoebe and John tend to be darker, moody, and provide information on each character’s checkered pasts.

Once Phoebe and John really meet in the narrative discourse, it’s pretty much all downhill from that point forward. The basic plot for this spare novel is that Phoebe joins John’s organization, which leads to a series of bombings targeted at abortion clinics. Will is the observer to Phoebe’s descent into John’s machinations. Phoebe and John have a lengthier past history, as John and Phoebe’s family once ran in similar circles.

What Kwon is grappling with most is the question of faith. One of the moments where this problem really becomes apparent is when we find out that the death of Phoebe’s mother was far more protracted than we had at first realized. Indeed, Phoebe and her mother were in a car accident. In the seconds leading up to the collision, Phoebe’s mother had thrown herself in front of Phoebe, which shielded Phoebe from much of the impact. In the aftermath of the crash, her mother is literally dying in front of her, but Phoebe is stuck in the twisted prison of the car and cannot wrest herself or her mother. Whether or not it would have mattered that Phoebe could have gotten her mother out quicker is not the issue: Phoebe’s traumatic experience of this event colors her understanding of the world around her. What matters when this kind of nonsensical torture can be allowed to occur, especially in front of loved ones?

Phoebe’s purposelessness is exactly what John Leal can prey upon. Leal himself is a complicated character who survived time in a North Korean labor camp. Much like Phoebe, the issue of faith has driven him to change his tactics concerning what he considers to be forms of injustice and violence occurring. Perhaps the greatest tragedy in this novel is apparent in the way that such vibrant characters are given over to such extreme actions. You can’t help but want to find a way to help Phoebe. In this kind of readerly response, Kwon has surely succeeded. We’re as helpless as Will is, watching another crash occur—albeit a metaphorical one—unfold before all of our eyes.

Where has Phoebe gone by the novel’s end? We’re not sure but we don’t have much reason to hope in this case, so we’ll relish Kwon’s exquisite prose instead. It’s the salve that makes the narrative’s irresolution that much more bearable. As a note, I later discovered through a podcast that this novel took 10 years to write, partly because of Kwon’s painstaking and meticulous attention to prose. It makes total sense. You’ll see right away that the level of craft and attention to individual words and phrases makes this reading experience its own. The prose sparks off the page, Kwon’s style uniquely hers. Let’s hope she takes way less time for the second publication while retaining her gift for effulgent prose.

Buy the Book Here!

Review Author: Stephen Hong Sohn

Review Editor: Leslie J. Fernandez

If you have any questions or want us to consider your book for review, please don’t hesitate to contact us via email!

Prof. Stephen Hong Sohn at ssohnucr@gmail.com

Gnei Soraya Zarook, PhD Student in English, at gzaro001@ucr.edu

comments

comments

A Review of R.F Kuang’s The Dragon Republic (Harper Voyager, 2019)

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) lesliejfernandez

lesliejfernandez

A Review of R.F Kuang’s The Dragon Republic (Harper Voyager, 2019).

By Stephen Hong Sohn

I read about 1/3 of R.F Kuang’s The Dragon Republic (Harper Voyager, 2019) before I set it down, then promptly forgot about it in the midst of a crazy academic year. I finally had the tail end of summer to read it! I very much enjoyed the action-packed first installment in this series (The Poppy War) and wanted to see how the narrative would continue.

Here is the publicity description: “Three times throughout its history, Nikan has fought for its survival in the bloody Poppy Wars. Though the third battle has just ended, shaman and warrior Rin cannot forget the atrocity she committed to save her people. Now she is on the run from her guilt, the opium addiction that holds her like a vice, and the murderous commands of the fiery Phoenix—the vengeful god who has blessed Rin with her fearsome power. Though she does not want to live, she refuses to die until she avenges the traitorous Empress who betrayed Rin’s homeland to its enemies. Her only hope is to join forces with the powerful Dragon Warlord, who plots to conquer Nikan, unseat the Empress, and create a new republic. But neither the Empress nor the Dragon Warlord are what they seem. The more Rin witnesses, the more she fears her love for Nikan will force her to use the Phoenix’s deadly power once more. Because there is nothing Rin won’t sacrifice to save her country . . . and exact her vengeance.”

I suppose I should provide my requisite spoiler warning here, as I sort of need to unveil plot details concerning the first book and part of the second to set things up. At the conclusion of the first, we see that the Empress Daji throws her assassination squad (called the Cike) under the bus, including its fearless leader Altan. After Altan’s tragic death, the Cike is under turmoil without any stable leadership, and Rin is not quite up to the task required of her. Much of the second novel deals with Rin’s ambivalent relationship not only with the leadership of the Cike (and what remains of it) but also of her own shamanistic power. Kuang throws a wrench into the equation when Daji is able to put Rin’s power under a special seal that is causing her to go mad over time. Eventually, with some help from outliers in the empire, Rin is able to get access to her power back, but must now be bonded with her ally, Kitay.

The novel moves toward is conclusion with a seemingly apocalyptic battle, with Rin and her allies outnumbered by Daji and a powerful wind-based shaman named Feylen. But through some clever tactical maneuvers and last minute aid by the Hesperians, Rin and her allies are able to prevail. Kuang does not let things end here. Just because the Dragon Republic is able to repel Daji and claim some ground does not mean Rin is safe. As the Dragon Republic allies (under the lead of Vaisra) with the Hesperians, who distrust anything related to shamanism, Rin is totally thrown under the bus.

Indeed, one of the most shocking moments—and please recall I did provide my spoiler warning earlier—is when Rin is stabbed by Nezha, her once ally and former comrade-in-arms. This moment of betrayal is particularly hard to swallow because, by this point, readers have discovered that Nezha too is a shaman, though has not told anyone about his powers. While Nezha’s father (Vaisra) works with the Hesperians to maintain control, shamans must now be discarded. The conclusion sees Rin now having to exact revenge and retribution yet again.

Buy the book here!

Review Author: Stephen Hong Sohn

Review Editor: Leslie J. Fernandez

If you have any questions or want us to consider your book for review, please don’t hesitate to contact us via email!

Prof. Stephen Hong Sohn at ssohnucr@gmail.com

Gnei Soraya Zarook, PhD Student in English, at gzaro001@ucr.edu

comments

comments

December 30, 2019

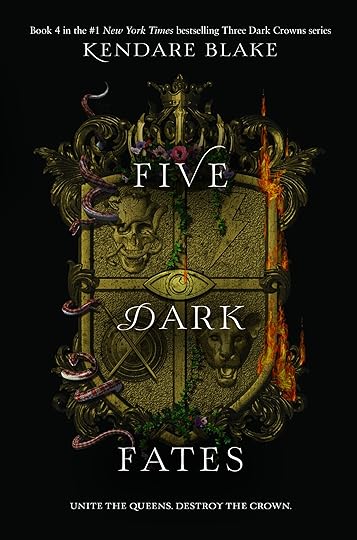

A Review of Kendare Blake’s Five Dark Fates (HarperTeen, 2019)

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) sorayaz

sorayaz

A Review of Kendare Blake’s Five Dark Fates (HarperTeen, 2019)

By Stephen Hong Sohn

In this review, I’m covering Kendare Blake’s Five Dark Fates (HarperTeen, 2019). Let’s let the official site give us some details right off the bat: “In the final book in the #1 New York Times bestselling Three Dark Crowns series, an all-out war is brewing—one that will pit sister against sister and dead against undead. After the grim confrontation with Queen Katharine, the rebellion lies in tatters. Jules’s legion curse has been unbound, and it is up to Arsinoe to find a cure, even as the responsibility of stopping the ravaging mist lies heavy on her shoulders, and her shoulders alone. Mirabella has disappeared. Katharine’s reign remains intact—for now. When Mirabella arrives, seemingly under a banner of truce, Katharine begins to yearn for the closeness that Mirabella and Arsinoe share. But as the two circle each other, the dead queens hiss caution—Mirabella is not to be trusted. In this conclusion to the Three Dark Crowns series, three sisters will rise to fight as the secrets of Fennbirn’s history are laid bare. Allegiances will shift. Bonds will be tested. But the fate of the island lies in the hands of its queens. It always has.”

So, as soon as I got this book, I basically just gave up on the rest of my obligations and started reading it. Frankly, I wanted to know if Blake was somehow going to go against the tradition of the fact that there would only be “one queen” basically “to rule” over all. I won’t spoil that ending but I will say that I was pretty shocked at how it all turned out. There *is* a casualty count, as can be expected about any book related to warfare. I think the most interesting thing that Blake has been developing over the course of these books is the arrival of former queens and possible queens. At this point, Katharine is called the “undead” queen because the former “possible” queens—the ones who didn’t defeat the others—have returned to inhabit her body and give her strength. Apparently, these ghosts are also able to transfer to other bodies and momentarily grant that new body some powers. But the arrival of these vanquished queens also brings with them a malevolent mist. What we eventually discover is that this mist holds the power of true queens who defeated their rivals, and the mist is after Katharine and her ghostly inhabitants.

I read this novel basically in one sitting. It’s been a fantastic ride and a serious upgrade from what I thought was a disappointing previous outing (The Goddess War trilogy). The strength of this series has been that you find yourself rooting for so many different characters; even the Poisoners, who I generally find to be snobbish and aloof, have their own charms. And Blake is quite patient in providing us with a sense of each queen’s motivations, thus allowing any ending—catastrophic or not—to be quite emotionally impactful. If there is a critique I’d pose for this particular narrative, it’s the binary that appears between the ghosts inhabiting Katharine and the Mist. I was hoping for a little bit of a more murky line between these two entities, but Blake leaves the concept of revolution and revenge a little bit more neat than I would have preferred.

Nevertheless, fans will be mourning the end of the series. And you can’t help but wonder, based on who actually survived, will there be another generation of sisters who will be born or has this tradition now been broken? Only time and Kendare Blake’s decision to return to Fennbirn one day will tell. Sources tell me that Blake has a stand-alone novel that will be her next outing and that it will be a thriller. It’s not yet listed!

Buy the Book Here!

Review Author: Review Editor: Gnei Soraya Zarook

If you have any questions or want us to consider your book for review, please don’t hesitate to contact us via email!

Prof. Stephen Hong Sohn at ssohnucr@gmail.com

Gnei Soraya Zarook, PhD Student in English, at gzaro001@ucr.edu

comments

comments

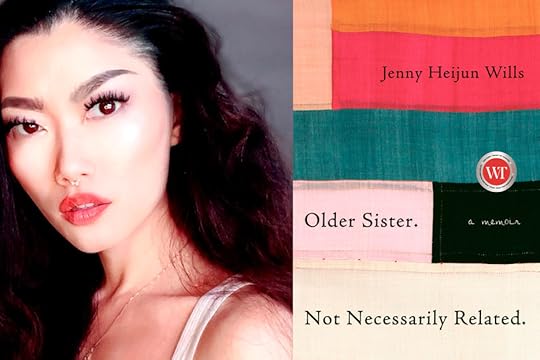

A Review of Jenny Heijun Wills’s Older Sister. Not Necessarily Related. (McLelland & Stewart, 2019)

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) sorayaz

sorayaz

A Review of Jenny Heijun Wills’s Older Sister. Not Necessarily Related. A Memoir (McLelland & Stewart, 2019)

By Stephen Hong Sohn

Well, it’s been the year—or two years, more accurately—of the Asian North American memoir and creative nonfiction! Jenny Heijun Wills’s Older Sister. Not Necessarily Related. A Memoir (McLelland & Stewart) adds to the immense pile of wonderful new publications (standing tall alongside Julie Yip-Williams’s The Unwinding of a Miracle, Esme Weijun Wang’s The Collected Schizophrenias, Alexander Chee’s How to Write an Autobiographical Novel, T. Kira Madden’s The Lost Tribe of Fatherless Girls, among others) with this stunning lyric memoir.

Let’s let the official page give us some context: “A beautiful and haunting memoir of kinship and culture rediscovered. Jenny Heijun Wills was born in Korea and adopted as an infant into a white family in small-town Canada. In her late twenties, she reconnected with her first family and returned to Seoul where she spent four months getting to know other adoptees, as well as her Korean mother, father, siblings, and extended family. At the guesthouse for transnational adoptees where she lived, alliances were troubled by violence and fraught with the trauma of separation and of cultural illiteracy. Unsurprisingly, heartbreakingly, Wills found that her nascent relationships with her family were similarly fraught. Ten years later, Wills sustains close ties with her Korean family. Her Korean parents and her younger sister attended her wedding in Montreal, and that same sister now lives in Canada. Remarkably, meeting Jenny caused her birth parents to reunite after having been estranged since her adoption. Little by little, Jenny Heijun Wills is learning and relearning her stories and those of her biological kin, piecing together a fragmented life into something resembling a whole. Delving into gender, class, racial, and ethnic complexities, as well as into the complex relationships between Korean women--sisters, mothers and daughters, grandmothers and grandchildren, aunts and nieces--Older Sister. Not Necessarily Related. describes in visceral, lyrical prose the painful ripple effects that follow a child's removal from a family, and the rewards that can flow from both struggle and forgiveness.”

This description does a pretty great job of describing the major beats in this particular work. Wills’s prose is absolutely sparking. Each section of the memoir is written in prose blocks that effect something like a prose poem actually, and I would guess I’d teach this text in a similar way. It is a memoir meant to be read aloud, even as the content can be excruciatingly painful. As with most brilliant memoirs, they must plumb the depths of some pretty dark places. Such is the case with Wills’s work, which doesn’t draw back from the complicated and thorny relational dynamics that make for searching for one’s birth family while also retaining connections to one’s adoptive family. What I especially appreciated about this particular work was how it helps carve out a space, however sometimes tenuous and not necessarily harmonious, that the adoptee sustains between multiple families and kinship systems. In this sense, it functions as a necessary corrective to texts that sends the message that poststructural kinships and alternative family structures are impossible. To be sure, Wills’s work also casts a critical lens at the adoption process itself, making it clear that such processes can be understood as a form of human trafficking. Yet, in the ominous shadow of that process, she must find to live her life.

One of the most poignant relationships that Wills explores is the one with her little sister Bora. They do not have the same father, but their connection is perhaps one of the strongest depicted throughout the memoir. Bora will at some point visit Wills in Canada and will study there. It is she who acts as the biggest bridge between Korea and the United States. And this particular sisterhood will resound, especially against the tumultuous journey that Wills so gracefully traces for her ever-growing families. An absolutely astounding work, with incandescent prose and equally luminous content.

Buy the Book Here!

Review Author: Review Editor: Gnei Soraya Zarook

If you have any questions or want us to consider your book for review, please don’t hesitate to contact us via email!

Prof. Stephen Hong Sohn at ssohnucr@gmail.com

Gnei Soraya Zarook, PhD Student in English, at gzaro001@ucr.edu

comments

comments

A Review of Amelie Wen Zhao’s Blood Heir (Delacorte Press, 2019)

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) sorayaz

sorayaz

A Review of Amelie Wen Zhao’s Blood Heir (Delacorte Press, 2019)

By Stephen Hong Sohn

This book was very high on my to-read list for the YA debuts because of the controversy it garnered prior to its publication. There was some critique that its depictions of slavery were racist. After having read the book, I am left to consider again one of the challenges of speculative fictional terrains, which possess “loose” connections to the so-called real world, leaving many interpretive paradigms to emerge.

In the case of Blood Heir, Zhao employs the fictional construct of the Affinites for a stand-in of an indentured servant/slave-type class. Affinites have special abilities but are simultaneously seen as social pariahs for those very same abilities. Their powers are suppressed, and they are forced to take on menial positions throughout the Cyrillian Empire. Apparently, Zhao did code two referential aspects into her fiction: first, because the novel is inspired by the myth of Anastasia Romanov, who was rumored to have survived the chaotic circumstances following the Bolshevik revolution; second, the Affinites were, according to Zhao (having spoken in contexts outside of the text), based upon Asian indentured slavery (that primarily occurred in the 19th century). Delacorte and/or Zhao may have been worried about adhering the text too closely to anything in our world, as the book does not include any author’s note nor does it explain any of the author’s intentionality. In any case, due to the controversy that occurred prior to the book release, the book was originally canceled by Zhao herself only to be later put back into the production schedule.

Now, after having read the book, I am surprised frankly by how much controversy this particular text has garnered, especially given how many other books involve similar plots and issues related to allegorical/metaphorical relationalities between our world and the fictional world. Nevertheless, the book does present us the opportunity to remember that even highly “estranging” fictional worlds can be politicized and framed through actual historical and social contexts (a connection that Zhao herself cannot escape given certain authorial intentionalities).

The novel itself adheres somewhat closely to the paranormal romance plot. There is a female teenager character who seems relatively normal, but is soon revealed to be absolutely extraordinary, not only in power but also in her heritage. She is a huge big bad to deal with in the form of the corrupted Cyrillian Empire. And, of course, there is a roguish man, who may or may not become a central, romantic lead. The darkness of the fictional world is apparent by much of the carnage and violence that tracks throughout the text, so readers should be aware that there are scenes that are pretty explicit brutality. Because of this representational streak, the novel seems to border on a kind of paranormal horror.

I found the text immensely readable. Upon realizing that there were only 100 pages left and I was already an hour past my bedtime, I made myself put the book away. Make no mistakes: the next night, I concluded my writing early just so I could finish it. Zhao’s novel will continue with Red Tigress, set to be released sometime in 2020. I’ll certainly be ready to read what seems to be the conclusion to a duology. Because of the specific controversies generated by this text, I would actually see this book as one that would be a productive addition to a classroom, as students could explore questions of representational appropriation, metaphorical relationality, and racial discourses as they are presented in YA fictions.

Buy the Book Here!

Review Author: Review Editor: Gnei Soraya Zarook

If you have any questions or want us to consider your book for review, please don’t hesitate to contact us via email!

Prof. Stephen Hong Sohn at ssohnucr@gmail.com

Gnei Soraya Zarook, PhD Student in English, at gzaro001@ucr.edu

comments

comments

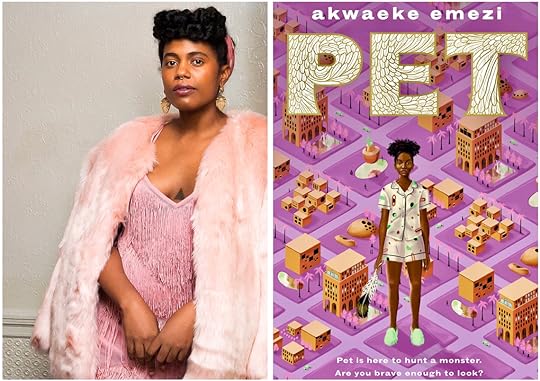

A Review of Akwaeke Emezi’s Pet (Make Me a World, 2019)

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) sorayaz

sorayaz

A Review of Akwaeke Emezi’s Pet (Make Me a World, 2019)

By Stephen Hong Sohn

Ah, yet another YA to help my mind relax. Here, I am reviewing Akwaeke Emezi’s Pet (Make Me a World, 2019), which is her young adult debut. Emezi is also author of a novel (Freshwater) that I have added to my to-read list. Apparently, next year, she has another novel coming out.

Emezi’s Pet had a very interesting premise; I’ll let the marketing description do some work for us here: “The highly-anticipated, genre-defying new novel by award-winning author Akwaeke Emezi that explores themes of identity and justice. Pet is here to hunt a monster. Are you brave enough to look? There are no monsters anymore, or so the children in the city of Lucille are taught. Jam and her best friend, Redemption, have grown up with this lesson all their life. But when Jam meets Pet, a creature made of horns and colors and claws, who emerges from one of her mother's paintings and a drop of Jam's blood, she must reconsider what she's been told. Pet has come to hunt a monster, and the shadow of something grim lurks in Redemption's house. Jam must fight not only to protect her best friend, but also to uncover the truth, and the answer to the question--How do you save the world from monsters if no one will admit they exist? Acclaimed novelist Akwaeke Emezi makes their riveting and timely young adult debut with a book that asks difficult questions about what choices you can make when the society around you is in denial.”

The strength and simultaneous weakness of this work is that it’s set in some sort of allegorical reality. Lucille is somewhere but also nowhere, filled with a vague history in which there were monsters that were later eradicated by angels. In this new, apparently improved town, there are no more bad things or bad people, so the arrival of Pet, who springs magically from a painting, is cause for concern. You see, Pet only comes alive when it is needed for a hunt and apparently, there is a hunt required because Jam’s best friend Redemption has some sort of monster around him. At first Jam thinks Pet is overreacting, but it becomes evident that Jam can’t see the monster at first. Only when Jam and Redemption go to their local library and engage in some old-fashioned reading and research do they discover that there might be an abuser that’s in Redemption’s extended family household. At that point, the novel moves quickly to its conclusion.

Emezi’s Pet would be a wonderful book to teach because of its allegorical qualities. Where is Lucille supposed to be set? What do we make of the fact that Lucille exists in a world in which there was some sort of Revolution? We are led to believe there has been some tremendous social revolution that has occurred and that beings like Pet may have been a part of this process, so we’re given to wonder: is the injustice that Pet helps adjudicate somehow linked to the older Revolution in some way? We’re not given enough information to know, and this kind of elision and vagueness leaves a feeling that something was not quite finished in terms of the heft and the political dynamics of this novel. Nevertheless, the impressionistic quality of the novel is precisely what will lend itself so fruitfully to classroom discussions.The highly-anticipated, genre-defying new novel by award-winning author Akwaeke Emezi that explores themes of identity and justice. Pet is here to hunt a monster. Are you brave enough to look?

There are no monsters anymore, or so the children in the city of Lucille are taught. Jam and her best friend, Redemption, have grown up with this lesson all their life. But when Jam meets Pet, a creature made of horns and colors and claws, who emerges from one of her mother’s paintings and a drop of Jam’s blood, she must reconsider what she’s been told. Pet has come to hunt a monster, and the shadow of something grim lurks in Redemption’s house. Jam must fight not only to protect her best friend, but also to uncover the truth, and the answer to the question–How do you save the world from monsters if no one will admit they exist?

Acclaimed novelist Akwaeke Emezi makes their riveting and timely young adult debut with a book that asks difficult questions about what choices you can make when the society around you is in denial.

SEE LESS

Review Author: Review Editor: Gnei Soraya Zarook

If you have any questions or want us to consider your book for review, please don’t hesitate to contact us via email!

Prof. Stephen Hong Sohn at ssohnucr@gmail.com

Gnei Soraya Zarook, PhD Student in English, at gzaro001@ucr.edu

comments

comments

December 18, 2019

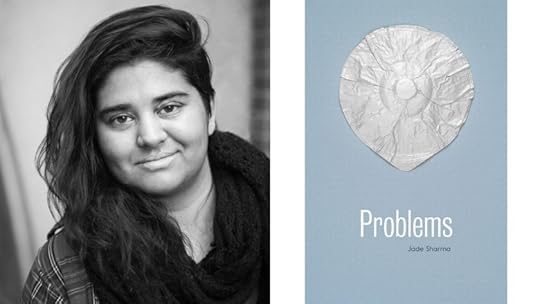

A Review of Jade Sharma’s Problems (Coffee House Press, 2016)

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) sorayaz

sorayaz

A Review of Jade Sharma’s Problems (Coffee House Press, 2016)

By Stephen Hong Sohn

I’ve been trying to catch up with as many Coffee House press books as possible, so this one came to the top of the list! I actually read about half of this book about three months ago, and then got caught up on so much work, I couldn’t come back to it until this summer. To put it bluntly, the read was pretty harrowing, so I didn’t mind a break. Before we move on to the text, I want to note that Jade Sharma passed away in July of 2019 at 39 years old. This page at Catapult where her friends and colleagues share their thoughts on her.

Let’s let the Coffee House Press official page give us some more context: “Dark, raw, and very funny, Problems introduces us to Maya, a young woman with a smart mouth, time to kill, and a heroin hobby that isn’t much fun anymore. Maya’s been able to get by in New York on her wits and a dead-end bookstore job for years, but when her husband leaves her and her favorite professor ends their affair, her barely-calibrated life descends into chaos, and she has to make some choices. Maya’s struggle to be alone, to be a woman, and to be thoughtful and imperfect and alive in a world that doesn’t really care what happens to her is rendered with dead-eyed clarity and unnerving charm. This book takes every tired trope about addiction and recovery, ‘likeable’ characters, and redemption narratives, and blows them to pieces.”

I loved the last line of this description: the term “likeable” is not what I’d call most of these characters. Caught in the depths of addiction, many of these characters simply revolve around the thing that they desperately crave: their next high. For Maya, the first half of the novel is really about her trying to find some balance between her addiction and living her life, but when her marriage to Peter ultimately falters, that seems to be the catalyst for her spiraling out of control. The “problems” of this novel are myriad, but one of the clearest ones is that there’s never a sense of where rock bottom actually is. At some point, she does end up in a rehabilitation center. You get the sense that finally, just finally, she may have kicked her addiction, but the novel’s conclusion sees her fall back into its grips.

Then, in the final pages—and your requisite spoiler warning is here—there seems to be yet another 180. You can’t help but be skeptical: given all of the ways that Maya has seemed unable to wrest herself free from addiction, has it really happened? Whatever the answer to this question, Sharma’s blunt, take-no-prisoners writing style is superbly positioned for this kind of character. There’s lots of other intriguing elements to this novel. For instance, Sharma takes the time to develop the very complicated boundaries of married life. Second, Maya engages in an extramarital affair with one of her professors—she, at one point, is interested in writing a novel. Though this relationship (not surprisingly) ends, she does develop an intriguing, though certainly flawed, friendship with this professor, who somehow manages to stay in touch with her despite her turbulent lifestyle. Sharma’s Problems is something certainly one could add to an Asian American literature course, especially ones that might be considering a topic like “bad” Asian Americans. Perhaps, the most productive intervention the novel does make is to undermine the predominant model minority narrative. A provocative, relentless novel.

Buy the Book Here.

Review Author: Review Editor: Gnei Soraya Zarook

If you have any questions or want us to consider your book for review, please don’t hesitate to contact us via email!

Prof. Stephen Hong Sohn at ssohnucr@gmail.com

Gnei Soraya Zarook, PhD Student in English, at gzaro001@ucr.edu

comments

comments

A Review of Taran Matharu’s The Chosen (Feiwel and Friends, 2019)

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) sorayaz

sorayaz

A Review of Taran Matharu’s The Chosen (Feiwel and Friends, 2019)

By Stephen Hong Sohn

I sometimes say you can’t really beat a mystery plot, and Taran Matharu’s The Chosen begins with a great conceit. The main character Cade basically wakes up in a strange and alien world. What is he doing there? How did he get transported from a boarding school to a place where a strange creature is hunting him? How shall he survive? These questions animate the beginning and push the reader quite properly forward.

Let’s let the official page give us some more information: “The Chosen introduces the first book in the Contender trilogy, an epic young adult fantasy from Taran Matharu, author of the New York Times–bestselling Summoner series. Throughout history, people have vanished with no explanation. A group of teenagers are about to discover why. Cade is settling into a new boarding school, contemplating his future, when he finds himself transported to another realm. He soon discovers their new world is populated with lost remnants from the past: prehistoric creatures, ancient relics, and stranger still—people. Overwhelmed by his new surroundings, Cade has little time to adjust, for soon he and his fellow classmates are forced to become contenders in a brutal game, controlled by mysterious overlords. But who are these beings and why did they choose these teens? Cade must prepare for battle . . . because hiding is not an option. Fans of fantasy and LitRPG will welcome this new character and world from the author of the Summoner series.”

I’m always a bit disappointed by these overviews; they often have to reduce the complexity of the plot down to its barest elements. In this case, the description focuses too much on Cade as the protagonist. This novel was striking to me for its ambitious character-system. Eventually, Cade realizes that he’s been transported to this otherworldly place with a bunch of his classmates, who include Finch (the novel’s main antagonist and a definite bully), Gobbler, Yoshi, Spex, Eric, and Scott. Later on, they’ll combine forces with a field hockey team who have also mysteriously appeared in this place: Amber, Bea, Trix, and Grace. The field hockey team presents more questions for the boarding school teens because they seem confused about certain time-specific elements and later reveal that they think it’s 1985! Then there’s also the strangely, nonverbal Quintus, who seems to be someone from an even earlier time than everyone else.

When dinosaurs start appearing, you know there’s bound to be more trouble and the group must figure out how to regroup so that they can survive the game that they are being forced to play. Suffice it to say that I was confused by the ending and am hoping that it’s a bit of a misleading reveal, but what cannot be denied is Matharu’s ambition. After the very lively Summoner series, he did not rest on his laurels and went in a very new direction! I’ll be sure to pick up the second in the series, which is slated for a June 2020 release!

For more, and to buy the book, go here.

Review Author: Review Editor: Gnei Soraya Zarook

If you have any questions or want us to consider your book for review, please don’t hesitate to contact us via email!

Prof. Stephen Hong Sohn at ssohnucr@gmail.com

Gnei Soraya Zarook, PhD Student in English, at gzaro001@ucr.edu

comments

comments

A Review of Roma Tearne’s The Last Pier (Aardvark Bureau, 2019)

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) sorayaz

sorayaz

A Review of Roma Tearne’s The Last Pier (Aardvark Bureau, 2019)

By Stephen Hong Sohn

So, I don’t want to reveal all my secrets, but I was able to get a copy of Roma Tearne’s The Last Pier (Aardvark Bureau, 2019) before it was officially out. I saved it for a night when I wanted to read something immersive. For those of you who haven’t had the chance to feast your reading eyes on Tearne’s work, you must immediately get Mosquito and Bone China, two of my literature favorites. In any case, before I get any further, I’m going to issue my requisite spoiler warning, as I begin with some big reveals right away because I want to deal with my three quibbles with this novel first.

Okay, so here are some minor critiques, where I focus on the tiny bads before the ginormous good that is this epic, atmospheric novel.

(1) Aardvark Bureau’s page quality and margins are just too small. I want to write with a heftier pen, but it will smudge or rip the pages, and the margins are TINY! I can’t even put one of those thumb print post-it notes at the edge! *sadface*

(2) I wanted to know more about Cecily Maudsley in between the two major temporal periods (prior to WWII and then the late 60s) that are being presented in the novel. Part of the issue here is Tearne’s choice to use an intimate, limited third person narration, who follows Cecily so closely that we’re only really allowed to think about what she is thinking about or trying to avoid thinking about. Thus, Cecily is less interested in what’s gone on with herself since the late 1930s and early 40s, so we don’t get too much of her life after that point. Certainly, Cecily herself is kind of like a living ghost, so perhaps she doesn’t even think that she’s been doing anything of note.

(3) I was torn by Carlo’s reappearance in the final arc of the book. On the one hand, I wanted him to show up. It presents readers with the possibility that there could be something good, even great, from that pre-WWII period to have survived (relatively) unscathed, but the wrap up is so quick, I was hoping for something a little bit more substantive. Again, though, in this fictional world, you can’t expect anything too uplifting. It’s basically a naturalist novel wrapped up in a disintegrative family saga.

So, now let me go back to the major overarching elements: the novel is an intriguing mash-up of a semi-whodunit, a spy narrative, the World War II narrative, and the family (families) saga. The families at the center are the Maudsleys and the Molinellos. Early on, readers discover that Rose Maudsley, though just a teenager, is dead. Cecily, Rose’s younger sister, is the one people indirectly blame, but readers are wondering: why?! This very question is the one that Tearne keeps close to her vest; she doesn’t reveal the intricacies of the chain reaction that results in Rose’s death until the final fifty or so pages. The payoff is well worth it, partly because Tearne is patiently portraying Cecily’s melancholic life and the fact that Cecily’s memory of the events leading up to and including Rose’s death are colored by her somewhat inaccurate, child-like perspective. We can’t quite get to the reveal because Cecily can’t figure it out herself, and our limited third does not, I would argue, know what’s gone on.

The cast of characters that surround Cecily and Rose, include their parents (Selwyn and Agnes), their Aunt Kitty, their older brother Joe, and their residence (The Palmyra House). Their family is intimately linked to an Italian immigrant family: Mario and Anna are at the head; they have a number of sons, including the youngest named Carlo and a daughter named Franca. Joe and Franca engage in a fledgling romance, while Carlo entertains some flirtations with Rose. Cecily looks on with envy because Cecily has a crush on Carlo. The other complication is a farm hand named Bellamy who also is engaging in some dalliances with Rose. When Robert Wilson, a purported surveyor, comes to their town of Bly, Tearne introduces the surveillance element. It’s pretty clear that he’s there in relation to national security, but we don’t understand what it is he is exactly trying to find out. The surveillance theme is mirrored by Cecily, because she has a habit of eavesdropping. As the War looms ever closer, the level of suspicion rises, leaving readers wondering which characters are involved in perhaps some more nefarious dealings.

The late 60s narrative is the diegetic present of the novel. Cecily has returned to The Palmyra House after having left for many years; the residence has been in a sort of fallow state since her mother Agnes died. Readers eventually discover that Cecily’s father, Selwyn, is alive, though in prison. Cecily’s return to Bly, and the Last Pier (the location where a building burned and Rose perished) is one that raises the hackles of townsfolk. She’s been tainted by what occurred just before World War II, but what exactly happened? So, hold on to your seats folks! What readers eventually discover is that Selwyn’s prison sentence is due to espionage; he’s a spy for Germany! When Selwyn suspects that he’s about to be found out, he goes to the building located near The Last Pier to burn it down and all the documents along with it. What he doesn’t realize is that his daughter is inside, having hoped to meet Robert Wilson there! The only reason why Selwyn thought that his cover was blown (which it was, but not in the way he expected) was because Cecily tells Selwyn that Rose has gone off with Captain Pinky (Wilson’s nickname) and that Pinky’s trying to get Rose to be involved somehow in espionage. This information is not quite accurate, but the damage is done.

By the time Selwyn and everyone else has figured out what’s actually happened, Rose has died in the fire, Selwyn’s been found out (due to information likely provided to Wilson by Aunt Kitty), and Cecily has been indirectly blamed for Rose’s death for having suggested to Selwyn that Rose was involved in espionage. Certainly, Wilson was using Rose for any information that she might have given him, but Wilson did not expect Rose to fall in love with him. In any case, the chain reaction is even more complicated precisely because of various love affairs going on between the Maudsleys and the Molinellos. Selwyn only married Agnes because he didn’t figure out that he was truly in love with Kitty until it was too late. Agnes, feeling ignored, eventually turns to Mario’s brother Lucio for affection and love. Eventually Selwyn realizes he cannot continue the affair with Kitty, but the termination of this relationship is one that reveals how much Kitty knows of Selwyn’s espionage duties and the fact that she’s likely to have betrayed him.

But the biggest reveal Tearne leaves is in relation to genealogy. Cecily’s biological mother is, in fact, Kitty. Tearne’s biggest trump card is perhaps the most tragic of the entire novel, because it is evident that Agnes, though far from being the perfect parent, nevertheless went above and beyond her duty to treat Cecily like she was, in fact, her biological daughter. Cecily’s realization that her actual biological mother did not seem to care for her and perhaps even held an active enmity toward her for being a favorite of Selwyn recasts her entire time as a Maudsley. Of course, the tragedy of this novel is not limited to the Maudsleys. Indeed, one of the most chilling aspects that the novel delves into are the internment camps that Italian immigrants were forced to relocate to in England.

Eventually, Mario, Lucio, and the elder sons who were born in Italy and therefore not English citizens are released, but their departure from the camp also coincides with their eventual deportation to Canada. During this period, their ship sinks; their lives are lost. Tearne bases her novel on historical events, and this sinking is a direct reference to the Arandora Star, which sank (with the eventual loss of 714 lives). The intertwining of the war and all of these associated events give Tearne’s work the epic texture we’ve come to associate with so many of her writings. The gravity and the political heft she achieves through this masterful negotiation of the domestic and the intimate, alongside the transnational and the ever-expansive, make The Last Pier more than worthy of your reading time.

Buy the Book Here.

Review Author: Review Editor: Gnei Soraya Zarook

If you have any questions or want us to consider your book for review, please don’t hesitate to contact us via email!

Prof. Stephen Hong Sohn at ssohnucr@gmail.com

Gnei Soraya Zarook, PhD Student in English, at gzaro001@ucr.edu

comments

comments

A Review of Rita Wong and Fred Wah’s beholden: a poem as long as the river (TalonBooks, 2018)

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) sorayaz

sorayaz

A Review of Rita Wong and Fred Wah’s beholden: a poem as long as the river (TalonBooks, 2018)

By Stephen Hong Sohn

So, I’ve been super behind on poetry reviews; there’s a ton I’ve been meaning to write up, but it’s been a crazy, crazy year, full of crazy ups and downs. The lows have been really low, and the highs have been incredibly high. In the midst of all of it, I am still making time to read poetry. The thing is: I read a lot of poetry. The trouble is that reviewing poetry is just harder. It takes more energy for me, so I find myself always a little bit backlogged even after I read and re-read full collections. Wong and Wah’s co-written, co-designed long poem was just a wonderful reading experience.

Let’s let the official site provide some context for us, shall we?: “Comprising two lines of poetic text flowing along a 114-foot-long map of the Columbia River, this powerful image-poem by acclaimed poets Fred Wah and Rita Wong presents language yearning to understand the consequences of our hydroelectric manipulation of one of North America’s largest river systems. beholden: a poem as long as the river stems from the interdisciplinary artistic research project “River Relations: A Beholder’s Share of the Columbia River,” undertaken as a response to the damming and development of the Columbia River in British Columbia, Washington, and Oregon, as well as to the upcoming renegotiation of the Columbia River Treaty. Authors Fred Wah and Rita Wong spent time exploring various stretches of the river, all the way to its mouth near Astoria, Oregon. They then spent several months creating long poems along the Columbia, each searching for a language that evoked the complexities of our colonial appropriation of it. beholden was then assembled as a page-turning book that reproduces the two long poems as they respond to the meanderings of the river flowing two thousand kilometres through Canada, the United States, and the territories and reserves of Indigenous Peoples. Visual artist Nick Conbere then transferred this winding footprint into a monumental, 114-foot horizontal banner. beholden: a poem as long as the river “reads” the geographic, historical, political, and social dimensions of the Columbia River, literally and figuratively, proposing two contrasting kinds of attention. As both a stand-alone poem and an accompanying piece to the visual installation exhibited at various galleries, beholden represents a vital contribution to a larger dialogue around the river through visual art, writing, and public engagement.”

One of the elements that you lose directly from the reading experience is the size and scope of the 114-foot horizontal banner. This poem is in some sense a kind of palimpsest in that it is a different, perhaps a revision, of another cultural production. The multimedia installation could of course perhaps be read as a separate work altogether (especially given the authorship status of the visual artistry of the work). Even in the context of the printed page, the collaborative element was fascinating, as two long, unbroken (for the most part, besides the problem of pagination and the occasional entrapment of words as they crashed into each other, as multiple currents in the poetic system flowed together) poetic lines mediate not only the longer history of the river, but its vital impact on communities, both human and otherwise.

One of the most crucial paratexts for beholden is the dialogue between Wah and Wong that appears just after the long poem ends. The conversation is fascinating because it makes clear the intent behind the construction of the poem, its lengthier germination, its political influences, and aesthetic aspirations. Wong’s prognostications, in particular, are depressing, because she comes to wonder about whether or not there will be the right kinds of readers for the works that she, and others like her, produce. Wong and Wah have produced something that exists at the crucial juncture between activist rhetoric and avant-grade experimentation. The juxtaposition is what may prove to be a harder sell amongst general reading publics, who need to read poetic works such as this one.

The other element that I applaud is Wong and Wah’s willingness to delve into indigenous histories and cultures, well aware that their location of speaking cannot ultimately stand for native voices. The risk they take is something that Trinh T. Minh-ha’s calls “speaking nearby,” which is an attempt to avoid appropriative approaches to representation while still voicing concerns that affect particular groups and communities with whom one might not necessarily have a direct affiliation. It is in this sense that we should this productive, politically grounded, and aesthetically inventive work. We can also look yet again to Canada (and their amazing independent presses) for pushing the bounds of both representation and social justice issues, as they are depicted in print realms.

Buy the Book Here.

Review Author: Review Editor: Gnei Soraya Zarook

If you have any questions or want us to consider your book for review, please don’t hesitate to contact us via email!

Prof. Stephen Hong Sohn at ssohnucr@gmail.com

Gnei Soraya Zarook, PhD Student in English, at gzaro001@ucr.edu

comments

comments