Stephen Hong Sohn's Blog, page 27

March 12, 2020

A Review of Roshani Chokshi’s The Star-Touched Queen (St. Martin’s Griffin, 2016).

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) lesliejfernandez

lesliejfernandez

A Review of Roshani Chokshi’s The Star-Touched Queen (St. Martin’s Griffin, 2016).

By Stephen Hong Sohn

Occasionally, I will request a review copy of a title I really know I’m going to want to read. This title was one of those titles, but it apparently was so sought after that no review copies were even left. In any case, now that I’ve sat down with a copy, I can see why the work was so popular. It presents us with the tried and true formula in the young adult paranormal romance genre that has taken the world and Hollywood by storm in recent years. In this case, our narrator and our young heroine is named Maya; she is born under a very bad horoscope, one portending doom and destruction.

From here, we’ll let B&N do some work for us: “Fate and fortune. Power and passion. What does it take to be the queen of a kingdom when you're only seventeen? Maya is cursed. With a horoscope that promises a marriage of Death and Destruction, she has earned only the scorn and fear of her father's kingdom. Content to follow more scholarly pursuits, her whole world is torn apart when her father, the Raja, arranges a wedding of political convenience to quell outside rebellions. Soon Maya becomes the queen of Akaran and wife of Amar. Neither roles are what she expected: As Akaran's queen, she finds her voice and power. As Amar's wife, she finds something else entirely: Compassion. Protection. Desire... But Akaran has its own secrets -- thousands of locked doors, gardens of glass, and a tree that bears memories instead of fruit. Soon, Maya suspects her life is in danger. Yet who, besides her husband, can she trust? With the fate of the human and Otherworldly realms hanging in the balance, Maya must unravel an ancient mystery that spans reincarnated lives to save those she loves the most…including herself. A lush and vivid story that is steeped in Indian folklore and mythology. The Star-touched Queen is a novel that no reader will soon forget.”

This description does a great job of giving us a sense of the work without providing too many spoilers. Chokshi’s main selling point is that she gives us the common genre conceits: a teenage female heroine who must somehow save the world, all the while maintaining a relationship with some super mysterious, yet super sexy male character. The challenge for readers outside the genre is probably how to take the romance elements. There were definitely cringe-inducing moments for me based upon those sequences when it’s clear Maya is pining for her dark underworld lover, and I’m obviously a die-hard fan of this particular genre. Is there any way to avoid such erotic, if clichéd sensibilities in this kind of work? Perhaps not, but I figured it would be best to provide that fair warning.

Otherwise, there are some truly compelling aspects of world building here; I’m always on the lookout for the ways that authors consider and create fantastical creatures. Fortunately, Chokshi can borrow from the long-established genre of Oriental tales to populate her world. At the same time, there were many terms that I wasn’t familiar with and that give Chokshi’s fictional world a very unique cast. There’s also an interesting anthropomorphic character that emerges in the back half of the novel that Chokshi clearly had fun with, especially in relation to the dialogue given to the character. The dark comedy offered by this character and the banter between this entity and Maya was a definite high point, given the especially apocalyptic storyline that we’re being offered.

Buy the Book Here:

Review Author: Stephen Hong Sohn

Review Editor: Leslie J. Fernandez

If you have any questions or want us to consider your book for review, please don’t hesitate to contact us via email!

Prof. Stephen Hong Sohn at ssohnucr@gmail.com

Leslie J. Fernandez, PhD Student in English, at lfern010@ucr.edu

comments

comments

A Review of Eugene Lim’s Dear Cyborgs (FSG Originals, 2017)

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) lesliejfernandez

lesliejfernandez

A Review of Eugene Lim’s Dear Cyborgs (FSG Originals, 2017)

By Stephen Hong Sohn

But, where were the cyborgs? Who are the cyborgs? These questions still remain with me, after having read this quirky work of fiction. Eugene Lim has been on my radar for quite awhile, but I’ve been totally behind and haven’t read his first two publications (Fog & Car and The Strangers). Here’s B&N with some more information on his latest Dear Cyborgs: “In a small Midwestern town, two Asian American boys bond over their outcast status and a mutual love of comic books. Meanwhile, in an alternative or perhaps future universe, a team of superheroes ponder modern society during their time off. Between black-ops missions and rescuing hostages, they swap stories of artistic malaise and muse on the seemingly inescapable grip of market economics. Gleefully toying with the conventions of the novel, Dear Cyborgs weaves together the story of a friendship’s dissolution with a provocative and timely meditation on protest. Through a series of linked monologues, a lively cast of characters explores narratives of resistance—protest art, eco-terrorists, Occupy squatters, pyromaniacal militants—and the extent to which any of these can truly withstand and influence the cold demands of contemporary capitalism. All the while, a mysterious cybernetic book of clairvoyance beckons, and trusted allies start to disappear. Entwining comic-book villains with cultural critiques, Eugene Lim’s Dear Cyborgs is a fleet-footed literary exploration of power, friendship, and creativity. Ambitious and knowing, it combines detective pulps, subversive philosophy, and Hollywood chase scenes, unfolding like the composites and revelations of a dream.”

Ah, this description! Well, does this work toy with the conventions of the novel? I suppose so, because it’s not a conventionally linear narrative. To say that I was confused by the ending would put it mildly. The narrative concerning the Asian American friendship is a frame that provides only a loose logic around what ends up actually occurring over the course of a short span of pages. There’s a meta-fictional impulse that seems to suggest that much of what we are reading is the textual translation of the comic book that the two Asian American characters write together once they are adults, but there’s no assurance that this explanation is the proper one. The other thing to note about the narrative is that much of it unfolds much like a play. There were portions that were extended monologues spoken by one character; these monologues were SO long and often so convoluted that I ended up reading them out loud just to keep the train of thought. Much of these monologues were philosophical in nature and spoken amongst the main superhero cadre in the story, but what is the larger point of this work?

There’s quite a lot of mini-narratives concerning artists, writers, and the fact of commodification. There’s also a number of other mini-narratives concerning political activism and resistance, but the circuitous nature of this work leaves us on very unstable ground. References to Richard Aoki and Asian American Studies within the last act of the novel only trouble the waters further, so we’re continually left in a state of stasis. Perhaps, this lack of resolution is part of the point, but Lim is not operating within the standard tropes of postmodernism first hallmarked by Angela Carter, Thomas Pynchon, and others. There seems to be a definitive desire to break out of the aforementioned malaise that exists, an apolitical ennui that suffuses all of the characters and leaves us in a tortuous surrealistic world, the likes of which seem more reminiscent of the fictions of Pamela Lu than the rabbit-hole of traditional postmodern writers. And so, I leave this review much like I began it: where were the cyborgs?

Buy the Book Here:

Review Author: Stephen Hong Sohn

Review Editor: Leslie J. Fernandez

If you have any questions or want us to consider your book for review, please don’t hesitate to contact us via email!

Prof. Stephen Hong Sohn at ssohnucr@gmail.com

Leslie J. Fernandez, PhD Student in English, at lfern010@ucr.edu

comments

comments

A Review of Rakesh Satyal’s No One Can Pronounce my Name (Picador, 2017).

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) lesliejfernandez

lesliejfernandez

A Review of Rakesh Satyal’s No One Can Pronounce my Name (Picador, 2017).

By Stephen Hong Sohn

I was really excited to see Rakesh Satyal move out of the first books club! It’s been a little bit of time since Satyal’s debut Blue Boy, but he’s obviously been hard at work perfecting the comic and dramatic undertones of No One Can Pronounce my Name (Picador, 2017). Let’s let B&N do some work for us: “In a suburb outside Cleveland, a community of Indian Americans has settled into lives that straddle the divide between Eastern and Western cultures. For some, America is a bewildering and alienating place where coworkers can’t pronounce your name but will eagerly repeat the Sanskrit phrases from their yoga class. Harit, a lonely Indian immigrant in his mid forties, lives with his mother who can no longer function after the death of Harit’s sister, Swati. In a misguided attempt to keep both himself and his mother sane, Harit has taken to dressing up in a sari every night to pass himself off as his sister. Meanwhile, Ranjana, also an Indian immigrant in her mid forties, has just seen her only child, Prashant, off to college. Worried that her husband has begun an affair, she seeks solace by writing paranormal romances in secret. When Harit and Ranjana’s paths cross, they begin a strange yet necessary friendship that brings to light their own passions and fears.”

I appreciated this particular description because it focuses primarily on the two characters who seem to have the most heft in the narrative space. One critique I had of this work was that there were characters that seemed to drop out of the story almost entirely after having had a strong introductory sequence (such as the queer bartender Achyut). But I digress: once Harit and Ranjana actually meet within the plotting, we start to see what Satyal is doing: creating a multifaceted depiction of a South Asian American immigrant community that extends beyond the domestic space of the home. Particularly compelling then is the unorthodox friendship between Ranjana and Harit, who don’t seem at first to have much in common, but Satyal makes evident that they are the proverbial “strangers in a strange land,” still trying to make their way in an America in which their brown-ness can isolate them.

The concluding sequence is perhaps the strongest, because it involves an unexpected road trip that seems multiple characters find the courage to pursue some of their more idiosyncratic goals. Satyal’s work finds purchase as both a bildungsroman (with respect to Harit) and a kunslterroman (with respect to Ranjana), as each comes to respective terms with their identity as a queer man, on the one hand, and a writer, on the other. The more humorous element to this work did remind me a little bit of a South Asian American version of As Good as It Gets, and this novel is one I will certainly consider teaching in the future. It’s an especially welcome addition to any course potentially exploring queer dynamics in Asian American literature.

Buy the book Review Editor: Leslie J. Fernandez

If you have any questions or want us to consider your book for review, please don’t hesitate to contact us via email!

Prof. Stephen Hong Sohn at ssohnucr@gmail.com

Leslie J. Fernandez, PhD Student in English, at lfern010@ucr.edu

comments

comments

A Review of Gabrielle Zevin’s Young Jane Young (Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, 2017).

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) lesliejfernandez

lesliejfernandez

A Review of Gabrielle Zevin’s Young Jane Young (Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, 2017).

By Stephen Hong Sohn

You can always count of Gabrielle Zevin to tell a great story in a tone of voice that absolutely hooks you right away. Such is the case with Zevin’s latest publication Young Jane Young (Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, 2017), which follows the masterfully plotted and narrated The Storied Life of A.J. Fikry, which was one of my favorite reads just based upon the story. Let’s let B&N do some requisite work for us: “Aviva Grossman, an ambitious congressional intern in Florida, makes the mistake of having an affair with her boss--and blogging about it. When the affair comes to light, the beloved congressman doesn’t take the fall. But Aviva does, and her life is over before it hardly begins: slut-shamed, she becomes a late-night talk show punch line, anathema to politics. She sees no way out but to change her name and move to a remote town in Maine. This time, she tries to be smarter about her life and strives to raise her daughter, Ruby, to be strong and confident. But when, at the urging of others, Aviva decides to run for public office herself, that long-ago mistake trails her via the Internet and catches up--an inescapable scarlet A. In the digital age, the past is never, ever, truly past. And it’s only a matter of time until Ruby finds out who her mother was and is forced to reconcile that person with the one she knows. Young Jane Young is a smart, funny, and moving novel about what it means to be a woman of any age, and captures not just the mood of our recent highly charged political season, but also the double standards alive and well in every aspect of life for women.”

This plot synopsis reveals quite a lot of information in a way that the novel actually doesn’t. For instance, you don’t even realize for a bit that Aviva Grossman has taken a new name and that name is none other than the titular Jane Young. The “young” part of Jane Young is the fact that when Jane Young was younger, she was actually Aviva Grossman, if that makes any sense. The other element that is slightly overshadowed in this description is the voices of the other characters. The first section of the novel is actually given over to Aviva Grossman’s mother, Rachel. It details a series of bad dates that she’s been going on; this initial section also gives readers a sense why Aviva Grossman would want to move to Maine and recreate her identity, even if that meant completely cutting off her mother. While their relationship is hardly the worst mother-daughter combo I’ve read about, the problem there is connected to the micro-management that makes Aviva feels as if she cannot escape the shadow not only for her disgrace, but also the disapproving eyes of her mother. This burden is too much, so in some sense, it becomes simply easier for Aviva to start anew.

The problem, as the synopsis makes clear, is that her very bright daughter begins to put two and two together, realizing that her paternal lineage is cloudy. Seeking answers, Ruby sets the second half of the novel’s plot in motion, but Zevin always has us in her very capable storytelling hands: the father is someone who you may not expect and in many ways, the novel is less about this mystery than it is about the empowered Grossman women who will find ways to stand tall despite an ignominy that has been unfairly leveraged upon Aviva. I actually found the novel’s ending to be a little bit abrupt and had hoped Zevin would work a little bit more with the parental aspect of the storyline; there’s quite a lot left open there, but perhaps there’s room for a sequel, one that would be commanded by the very spirited character of Ruby.

Buy the Book Here:

Review Author: Stephen Hong Sohn

Review Editor: Leslie J. Fernandez

If you have any questions or want us to consider your book for review, please don’t hesitate to contact us via email!

Prof. Stephen Hong Sohn at ssohnucr@gmail.com

Leslie J. Fernandez, PhD Student in English, at lfern010@ucr.edu

comments

comments

A Review of Kyo Maclear’s Birds Art Life: A Year of Observation (Scribner, 2017).

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) lesliejfernandez

lesliejfernandez

A Review of Kyo Maclear’s Birds Art Life: A Year of Observation (Scribner, 2017).

By Stephen Hong Sohn

The first book I really felt some gravitation toward in a long time was Kyo Maclear’s Birds Art Life (Scribner, 2017). The topic was entirely new to me and Maclear, who I am familiar with because of her pictures books and earlier novels, hadn’t yet produced an adult-oriented work that was available stateside. Her novels, Letter Opener and Stray Love, are in that international publication limbo that makes them really only available through used copies that make it across the border or are sold in online book shops. The official page over at S&S tells us: “A writer’s search for inspiration, beauty, and solace leads her to birds in this intimate and exuberant meditation on creativity and life—a field guide to things small and significant. When it comes to birds, Kyo Maclear isn’t seeking the exotic. Rather she discovers joy in the seasonal birds that find their way into view in city parks and harbors, along eaves and on wires. In a world that values big and fast, Maclear looks to the small, the steady, the slow accumulations of knowledge, and the lulls that leave room for contemplation. A distilled, crystal-like companion to H is for Hawk, Birds Art Life celebrates the particular madness of chasing after birds in the urban environment and explores what happens when the core lessons of birding are applied to other aspects of art and life. Moving with ease between the granular and the grand, peering into the inner landscape as much as the outer one, this is a deeply personal year-long inquiry into big themes: love, waiting, regrets, endings. If Birds Art Life was sprung from Maclear’s sense of disconnection, her passions faltering under the strain of daily existence, this book is ultimately about the value of reconnection—and how the act of seeking engagement and beauty in small ways can lead us to discover our most satisfying and meaningful lives.”

I really appreciated this book description because it captures what is so wonderful about this “year of observation,” but I think it crucially misses what really catalyzes this time period: the possible death of her father. The opening chapter details how Maclear’s father is in the hospital with no clear prognosis on his condition; it is clear even after the most dangerous moments have passed that he is aged and frail, even if he remains stalwart in his commitment to grooming and to being independent. The mortality of our parents is no doubt a concern for so many and has spurred many a writer to generate incredible works of art. In this vein, Maclear is philosophically pursuing a different way of engaging life that is not necessarily so goal-oriented, investment driven, capitalistically-inclined, and she seems to find it in her birding hobby. Birding slows Maclear down, allows her to revel in what seem to be minute details, and also simply enables her to contemplate what is most important to her.

Along the way, these musings allow us a more textured understanding of complicated family dynamics, including her biracial upbringing, the tensions between her parents who would eventually divorce, and how she came to be a writer. As I moved further into this creative nonfictional work, I especially appreciated its patchwork and multigenre qualities: Maclear includes illustrations and biographies of individuals who are birders, so the narrative weaves in memoir, art, and some historical/sociological considerations. Because I know so little about birds, but did once consider going to graduate school in oceanography, I was absolutely compelled to learn about birds, their many varieties, their many histories, and the ways that humans and birds find multiple modes of interaction. Maclear’s work is one that might be part of a literature course that involves Asian North American writers and their connections to and depictions of the animal world; here, I am thinking of Paula Young Lee’s Deer Hunting in Paris, Tania James’s The Tusk that Did the Damage, Sigrid Nunez’s Mitz: the Marmoset of Bloomsbury, among others.

Buy the Book Here:

Review Author: Stephen Hong Sohn

Review Editor: Leslie J. Fernandez

If you have any questions or want us to consider your book for review, please don’t hesitate to contact us via email!

Prof. Stephen Hong Sohn at ssohnucr@gmail.com

Leslie J. Fernandez, PhD Student in English, at lfern010@ucr.edu

comments

comments

March 11, 2020

A Review of Jen Lee’s Garbage Night (NoBrow Press, 2017).

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) lesliejfernandez

lesliejfernandez

A Review of Jen Lee’s Garbage Night (NoBrow Press, 2017).

By Stephen Hong Sohn

What a quirky, difficult to label graphic novel we have here in Jen Lee’s debut Garbage Night (NoBrow Press, 2017). Animals talk, but who knows exactly why? Could it be because we’re in a postapocalyptic wasteland in which no humans seem to be left alive? These animals are basically dumpster diving all day, because that’s where there seems to be what’s left of food to eat. We’ll let B&N give us some more contexts: “In a barren and ransacked backyard, a dog named Simon lives with his two best friends: a raccoon and a deer. The unlikely gang spends their days looting the desolate supermarket and waiting for the return of the hallowed ‘garbage night’ – but week after week, the bins remain empty. While scavenging one day, the trio meet Barnaby – another abandoned dog who tells them about the ‘other town’ where humans are still rumored to live. Spurred on by hunger and the promise of food, the trio joins up with Barnaby and set off into the unknown…With echoes of post-war, derelict places, Garbage Night explores how animals may internalize their changing environment and express their thoughts, fears and hopes.”

This description doesn’t give us any answers. You can’t help but wonder whether or not Simon and his two buddies are able to talk because of some nuclear disaster, which killed off all the humans and mutated the animals to give them the ability to talk. Whatever the case, the animals function with their own hierarchies. The more predatory the animal, the more likely that animal—at least, in this fictional world—is liable to turn on you, turn you into prey. Coyotes, for instance, in a later sequence definitely function in this capacity. Because animals can now talk and because they aren’t always looking for food in the same way, this kind of hierarchy begins to come off as a form of cannibalism reminiscent of something you might have read in a number of novels such as Cormac McCarthy’s The Road.

There is much to praise in this work; I did appreciate the understated quality of the story. The questions leave ample room for a classroom discussion to take place were one to teach this work. And Lee fully provides her wayward trio with enough pathos to evoke sympathies even amongst the most heart-hardened of readers. There’s a moment in which the trio make a tentative new ally, one who seems most intent on fracturing the bonds of this group. Lee chooses to sequence these panels through the deer’s eyes; you get an immediate sense of the deer’s sense of melancholy in this land without garbage, without excess. The art always functions to help evoke this sense of lack; the colors generally move toward earth tones, with strong tinges reds and oranges that suggest that the environment has become overused. Let’s hope Garbage Night has a sequel, so we can see if Simon and his friends ever find the mecca of surfeit that seems to fuel their existence and their inveterate survival instincts.

Buy the Book Here:

Review Author: Stephen Hong Sohn

Review Editor: Leslie J. Fernandez

If you have any questions or want us to consider your book for review, please don’t hesitate to contact us via email!

Prof. Stephen Hong Sohn at ssohnucr@gmail.com

Leslie J. Fernandez, PhD Student in English, at lfern010@ucr.edu

comments

comments

A Review of Curtis C. Chen’s Kangaroo Too (Thomas Dunne Books, 2017).

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) lesliejfernandez

lesliejfernandez

A Review of Curtis C. Chen’s Kangaroo Too (Thomas Dunne Books, 2017).

By Stephen Hong Sohn

Like Curtis C. Chen’s debut (Waypoint Kangaroo), I had a number of false starts with this novel. I’m not sure what the problem is because once I did set my mind to finishing this novel, it took off pretty stratospherically, which is to say that this novel (a kind of sequel to Waypoint Kangaroo) improves (significantly) upon Chen’s debut. I mentioned in my review of Waypoint Kangaroo that Chen doesn’t make much use of the main character’s unique power in that novel: his ability to create a kind of pocket in the fabric of space-time, which allows him to store pretty much anything inside, including people and objects. There’s a limit to what he can store in terms of size and in terms of how it impacts him physiologically: the more he uses the pocket and the more massive pocket he creates, the more fatigued he gets. The pocket is obviously metaphorically related to his codename, which connects him to the lovely, bounding titular marsupial. This sort-of-sequel makes much use of this pocket power and is an immensely readable, plot-twisting narrative that never lets up.

We’ll let B&N do some more work here: “Set in the same world as Waypoint Kangaroo, Curtis C. Chen's Kangaroo Too is bursting with adrenaline and intrigue in this unique outer space adventure. On the way home from his latest mission, secret agent Kangaroo’s spacecraft is wrecked by a rogue mining robot. The agency tracks the bot back to the Moon, where a retired asteroid miner—code named ‘Clementine’ —might have information about who’s behind the sabotage. Clementine will only deal with Jessica Chu, Kangaroo’s personal physician and a former military doctor once deployed in the asteroid belt. Kangaroo accompanies Jessica as a courier, smuggling Clementine’s payment of solid gold in the pocket universe that only he can use. What should be a simple infiltration is hindered by the nearly one million tourists celebrating the anniversary of the first Moon landing. And before Kangaroo and Jessica can make contact, Lunar authorities arrest Jessica for the murder of a local worker. Jessica won’t explain why she met the victim in secret or erased security footage that could exonerate her. To make things worse, a sudden terror attack puts the whole Moon under lockdown. Now Kangaroo alone has to get Clementine to talk, clear Jessica’s name, and stop a crooked scheme which threatens to ruin approximately one million vacations. But old secrets are buried on the Moon, and digging up the past will make Kangaroo’s future very complicated...”

This plot description probably gets us to about page 130 in the novel, which means that it leaves the vast bulk of the mystery unspoiled. I’d rather be mum on the matters because there’s a number of surprises, which I had no idea were coming. Sure, there had to be some betrayals and double-crossings, some masquerades at work, precisely because we’re in the Kangaroo world. One of the biggest allies that Kangaroo was supposed to have in the first novel, Sakraida, of course ends up being the super-villain instead. The legacy of Sakraida’s betrayal of Kangaroo’s larger intelligence agency is felt throughout this particular book. Everyone surmises that Sakraida is behind the blast that almost kills Kangaroo in the opening of the novel. At the same time, this particular narrative ratchets up the stakes because the entire lunar colony is put into jeopardy by whatever is going on. Whereas the first novel dealt with a cruise liner in crisis, one that might crash into Mars (if I can vaguely remember correctly), this installment places us on a lunar mission in which tens of millions of lives may depend upon Kangaroo and his allies unraveling the mysteries that continue to crop up here.

In terms of style and atmosphere, Chen obviously retains the comic tonalities of the debut, with Kangaroo’s requisite heterosexual lens filtering pretty much all of his observations. Chen’s self-consciousness about the “hornified” male gaze is apparent when Kangaroo thinks there’s something flirtatious going on with one of the guides who are helping him and Jessica get settled in their affairs on the moon, but what it turns out to be is that this guide is a lesbian and her connection to Kangaroo is simply a sublimation of her desire for a romance that has gone wrong in her own personal life. Kangaroo’s bust here signals a larger conceit concerning his sometimes obscured and certainly subject way of looking at the unfamiliar lunar culture unfolding and catastrophically disintegrating around him. Once I got within the last one hundred pages, there was no choice but for me to stay up until 3 a.m. to finish the novel. To be sure, today, I am cranky, groggy, and unable to do much of what I had hoped to accomplish, but was it worth it? Most definitely yes. Let’s hope Chen has a couple more installments set for us, though as of this time, there’s no mention of a third in the Kangaroo series. Oh, and by way of a quick addition: the title of this novel is especially clever, but what I mean by that, well you’ll just have to read it to understand.

Buy the Book Here:

Review Author: Stephen Hong Sohn

Review Editor: Leslie J. Fernandez

If you have any questions or want us to consider your book for review, please don’t hesitate to contact us via email!

Prof. Stephen Hong Sohn at ssohnucr@gmail.com

Leslie J. Fernandez, PhD Student in English, at lfern010@ucr.edu

comments

comments

A Review of Christine Hyung-Oak Lee’s Tell Me Everything You Don't (Ecco, 2017). Remember

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) lesliejfernandez

lesliejfernandez

A Review of Christine Hyung-Oak Lee’s Tell Me Everything You Don't Remember: The Stroke That Changed My Life (Ecco, 2017).

I’ve definitely been on a memoir kick lately; seems to be the first thing I pick up these days. Next up on the list was Christine Hyung-Oak Lee’s Tell Me Everything You Don't Remember: The Stroke That Changed My Life (Ecco, 2017). I actually recall this author because I saw that she would be publishing a novel (tentatively called Golem of Seoul and due out sometime in 2018). In any case, I was surprised to see this listing first, but was intrigued by the provocative title. As the official page sets this one up for us: “Christine Hyung-Oak Lee woke up with a headache on New Year’s Eve 2006. By that afternoon, she saw the world—quite literally—upside down. By New Year’s Day, she was unable to form a coherent sentence. And after hours in the ER, days in the hospital, and multiple questions and tests, she learned that she had had a stroke. For months, Lee outsourced her memories to her notebook. It is from these memories that she has constructed this frank and compelling memoir. In a precise and captivating narrative, Lee navigates fearlessly between chronologies, weaving her childhood humiliations and joys together with the story of the early days of her marriage; and then later, in painstaking, painful, and unflinching detail, her stroke and every upset, temporary or permanent, that it causes. Lee processes her stroke and illuminates the connection between memory and identity in an honest, meditative, and truly funny manner, utterly devoid of self-pity. And as she recovers, she begins to realize that this unexpected and devastating event provides a catalyst for coming to terms with her true self.”

Stylistically, what’s interesting about this memoir is that it’s fairly repetitive and pretty much non-linear. This approach was perhaps necessitated by Lee’s condition; it’s evident that she employs notes and other such writings that she penned during her recovery to help generate what would eventually become this memoir. Despite this type of style, the memoir is eminently readable. Perhaps, one of the most tragic things about this memoir is how much the author has to redefine herself in light of the stroke. Because of an underlying medical condition associated with this stroke, the author battled fatigue related to cardiovascular activities all of her life. It was only when the stroke made clear that why this problem occurred (amongst other medical issues) that the author begins to understand that things she thought were all in her head were actually physiologically related. What’s further apparent is that the desire to forge ahead despite these medical issues (leading up to the apocalyptic stroke) created a hardened persona, one that would be categorically undone by the simple fact that the author could not create short term memories following the stroke. In some sense, this inability to remember becomes a way for the author also to have a kind of renaissance, to remake her identity in light of the new information and during her incredible recovery process.

Along the way, readers are treated to the navel-gazing necessary for the best in this genre; particularly crucial is the elliptical, yet nuanced way that the author delves into her marriage, which is slowly crumbling apart. There’s always an intriguing meta-discursive level to this work, as the author makes clear that the very writing of the memoir would have been impossible had she not been able to recover her short term memory capabilities. Indeed, as she explicitly tells us, short term memories allow us to retain what it is we wrote earlier on in a sentence so that we can make sense of the what need to write at the end. Thus, to write this memoir, to become the writer she needs to be, the author achieves more than a publication, she models her amazing, but difficult recovery process. Certainly, a wonderful work to be paired alongside other medical memoirs, such as Paul Kalanithi’s When Breath Becomes Air.

Buy the Book Here:

Review Author: Stephen Hong Sohn

Review Editor: Leslie J. Fernandez

If you have any questions or want us to consider your book for review, please don’t hesitate to contact us via email!

Prof. Stephen Hong Sohn at ssohnucr@gmail.com

Leslie J. Fernandez, PhD Student in English, at lfern010@ucr.edu

comments

comments

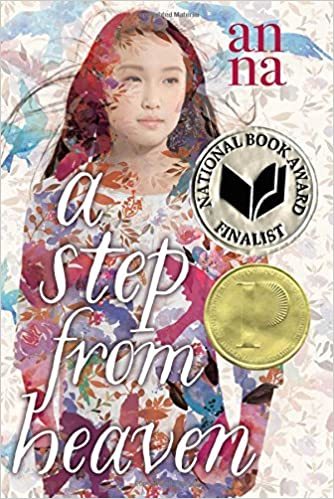

A Review of An Na’s A Step from Heaven (Atheneum Reprint Edition, 2016).

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) lesliejfernandez

lesliejfernandez

A Review of An Na’s A Step from Heaven (Atheneum Reprint Edition, 2016).

By Stephen Hong Sohn

This young adult/ children’s book is one I’ve meant to read forever. Like Linda Sue park, An Na is probably one of the best known Korean American authors who write for the younger age groups. Sadly, I hadn’t read anything from An Na. I’m not sure why, but chalk I it up to the fact that there’s just too much to keep up with. I frequently like to tell people that there was a time that I thought: okay, I can read it all. This thought obviously occurred when I was first delving into the field and was reliant upon the existing criticism to map out what was available. So A Step from Heaven was originally published quite a while back; it made a huge splash and won An Na a number of different accolades, definitely putting her on the map as an author to watch. I was excited to see it come out in this reprint edition, especially because Atheneum (which is a children’s literature imprint of Simon & Schuster) saw fit to publish it in both hardcover and paperback editions).

In any case, here is B&N with their usual pithy description: “At age four, Young Ju moves with her parents from Korea to Southern California. She has always imagined America would be like heaven: easy, blissful, and full of riches. But when her family arrives, she finds it to be the opposite. With a stubborn language barrier and cultural dissimilarities, not only is it impossible to make friends, but even her family’s internal bonds are wavering. Her parents’ finances are strained, yet her father’s stomach is full of booze. As Young Ju’s once solid and reliable family starts tearing apart, her younger brother begins to gain more freedom and respect simply because of his gender. Young Ju begins to lose all hope in the dream she once held—the heaven she longs for. Even as she begins to finally fit in, a cataclysmic family event will change her idea of heaven forever. But it also helps her to recognize the strength she holds, and envision the future she desires, and deserves.”

This novel was a very tough read. It immediately makes you wonder what stands for the generic taxonomy that circumscribes children’s literature? My tendency has been to think of this “form”—if we can call it that—as one that focuses on a singular narrative perspective that tends to see some younger child grow up through a challenging experience. The difference between this form and the bildungsroman is that the child typically does not fully grow up. That is, the child is still a child, just an older version of a child. The other element is that these novels tend to have far more positive resolutions, leading us to the believe that the child figure has the ability to withstand some great conflict or trauma.

The trouble with Asian American writers working in this genre is that the “great conflict or trauma” is so often tied not only to the personal but some larger structural problematic. In this case, the father’s domestic abuse is obviously tied to the class dynamics of the family’s migration: they are barely making ends meet; the “step from heaven” that the United States is supposed to be hardly measures up to that celestial description. In any case, this work deviates from so many other cultural productions because of the gravity of its central conflicts and issues. The domestic abuse becomes so pervasive, I did not even understand how the novel was going to wrap up in any way that would resolve all the storylines.

Buy the Book Here:

Review Author: Stephen Hong Sohn

Review Editor: Leslie J. Fernandez

If you have any questions or want us to consider your book for review, please don’t hesitate to contact us via email!

Prof. Stephen Hong Sohn at ssohnucr@gmail.com

Leslie J. Fernandez, PhD Student in English, at lfern010@ucr.edu

comments

comments

March 2, 2020

A Review of Viet Thanh Nguyen’s The Refugees (Grove Press, 2017).

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) lesliejfernandez

lesliejfernandez

A Review of Viet Thanh Nguyen’s The Refugees (Grove Press, 2017).

By Stephen Hong Sohn

It’s been ages since I’ve had a chance to feast on some magisterial short stories. Lucky for us that Viet Thanh Nguyen is a publication machine and has gifted us with The Refugees so soon after Nothing Ever Dies and The Sympathizer. Let’s hope he keeps churning these gold nugget publications out. In any case, B&N doesn’t really do such a good job of giving us some background on the book, so I’ve gone elsewhere. The Grove Atlantic site gives us this pithy description: “With the coruscating gaze of The Sympathizer, in The Refugees Viet Thanh Nguyen gives voice to lives led between two worlds, the adopted homeland and the country of birth. From a young Vietnamese refugee who suffers profound culture shock when he comes to live with two gay men in San Francisco, to a woman whose husband is suffering from dementia and starts to confuse her for a former lover, to a girl living in Ho Chi Minh City whose older half sister comes back from America having seemingly accomplished everything she never will, the stories are a captivating testament to the dreams and hardships of immigration.” I’m not sure I would call The Sympathizer or The Refugees “coruscating,” but I’ll still give the copy writer an A+ for a great adjective.

Nguyen’s got a deft hand with the short story; the compact style suits him. Each entry in the collection has a fable-like quality. The first, “Black-Eyed Woman,”, sets up the stakes of the collection at large, as a daughter and her mother grapple with ghosts of the past. In some sense, Nguyen is beautifully dredging up the past for the aesthetic purposes of representational resurrections. My favorite story hands-down was “The Other Man,” which details a refugee’s arrival in the United States and his acculturation in San Francisco in the years prior to the AIDS epidemic. In “War Years,” a family grapples with the aggressive fundraising of an anti-communist activist in the Vietnamese community. This story was a tough one, focusing on the complicated political allegiances of families in the wake of war. “The Transplant” was one of the quirkier stories in the collection; the protagonist wants to connect with a family member of the individual who has donated him a liver. In this case, and I’m providing a spoiler warning here, the person who he believes is that family member is someone else entirely.

“I’d Love You to Want Me” was the most poignant collection, as a woman (who very much enjoys working at her local library) deals with the caretaking duties of her husband (a professor), who is slowly losing memory (due to Alzheimer’s. “The Americans” details a family who visits their daughter, who is living in Vietnam. The father is a Vietnam War veteran and returns to Vietnam with mixed emotions. I especially found the conclusion to be affecting. “Someone Else Besides You” explores the life of a recently divorced man; his father is a widower, and he has begun dating again. “Fatherland” involves a young woman who returns to Vietnam to visit her biological family, which she was separated from due to circumstances of the war. Her younger sister realizes that her life in the United States is a fantasy. Nguyen is always at his past looking at the complicated and dysfunctional relationships that bloom among family members. The intricacies of these links flesh out the multifaceted lives of the many refugees that populate these stories.

Buy the Book Here:

Review Author: Stephen Hong Sohn

Review Editor: Leslie J. Fernandez

If you have any questions or want us to consider your book for review, please don’t hesitate to contact us via email!

Prof. Stephen Hong Sohn at ssohnucr@gmail.com

Leslie J. Fernandez, PhD Student in English, at lfern010@ucr.edu

comments

comments