Alastair Luft's Blog

February 14, 2021

Upcoming Book

My next novel, a literary thriller about a retired Navy SEAL who leads an assassination operation against the president of China, comes out on June 17, 2021. If you're interested in an advance e-copy in exchange for leaving a review on pub day, please fill out this survey.

https://forms.gle/bfRsg3jQbZNfraDP6

Here's an early blurb from Laya V. Smith, author of The Lumbermill:

"This book tries to trick you into believing it's a politician thriller, but it is so much more than that. A compelling social commentary set in the near future, One Kingdom Under Heaven brings the darkest possibilities of contemporary politics into sharp relief. With complex characterization, literary language, and fast-paced storytelling, Luft has created a novel that grabs the reader by the throat and refuses to let go until the very last page."

Thanks!

Alastair

https://forms.gle/bfRsg3jQbZNfraDP6

Here's an early blurb from Laya V. Smith, author of The Lumbermill:

"This book tries to trick you into believing it's a politician thriller, but it is so much more than that. A compelling social commentary set in the near future, One Kingdom Under Heaven brings the darkest possibilities of contemporary politics into sharp relief. With complex characterization, literary language, and fast-paced storytelling, Luft has created a novel that grabs the reader by the throat and refuses to let go until the very last page."

Thanks!

Alastair

Published on February 14, 2021 06:29

•

Tags:

arc, fiction, reader-copy

February 12, 2017

Surprise

2011 was supposed to be a banner year in Afghanistan.

Starting in 2009, the American military began surging an additional 33,000 personnel into theatre, a half-again increase of pre-surge troop levels of 68,000. With these extra boots on the ground, 2010 saw an increase in operations and tempo that pushed the Taliban back on their heels. Following this success, 2011 was supposed to be the year when these gains would become entrenched, thereby allowing the US to dial back on force levels during the summer of 2011, when the extra troops would start leaving while the Afghan security forces took the lead on operations.

Then the Taliban happened.

In April 2011, the Taliban executed a bold prison break at the Sarpoza prison in Kandahar city. That month, just before the start of the spring fighting season, over 400 Taliban prisoners broke-out through a tunnel, which had evidently taken months to build and was sophisticated enough to have electricity and ventilation.

A month later, the spring fighting season kicked off with a bang on 7 May, when a number of Taliban fighters simultaneously attacked multiple locations in Kandahar city, including the governor’s palace. The attack lasted for days and was reportedly conducted by many of the recently liberated prisoners of Sarpoza prison. Needless to say, this operation consumed the focus of Afghan and Coalition security forces, interrupting numerous other operations. Did it derail the overall coalition security plans? Not really, although it did creative an extensive blip in operational tempo. Did it stop the drawdown or transfer of responsibilities to the Afghans? Not at all. But what it did do, was send a strong message about the Taliban’s continued capability, a demoralizing effect that hurt the confidence of Afghan security forces. In doing so, it also demonstrated the principle of war known as surprise, a principle that’s equally effective in an artist’s creative battles.

A month later, the spring fighting season kicked off with a bang on 7 May, when a number of Taliban fighters simultaneously attacked multiple locations in Kandahar city, including the governor’s palace. The attack lasted for days and was reportedly conducted by many of the recently liberated prisoners of Sarpoza prison. Needless to say, this operation consumed the focus of Afghan and Coalition security forces, interrupting numerous other operations. Did it derail the overall coalition security plans? Not really, although it did creative an extensive blip in operational tempo. Did it stop the drawdown or transfer of responsibilities to the Afghans? Not at all. But what it did do, was send a strong message about the Taliban’s continued capability, a demoralizing effect that hurt the confidence of Afghan security forces. In doing so, it also demonstrated the principle of war known as surprise, a principle that’s equally effective in an artist’s creative battles.

Surprise

The essence of surprise in a military sense is to strike an adversary at a time, place, or by a method for which they’re not prepared. By forcing the enemy to deal with something unfamiliar, surprise negatively impacts an adversary’s reaction time and hopefully drives them to make poor decisions. There’s a psychological aspect as well, as anyone who’s experienced surprise should be able to attest. Especially in a competitive sense, it doesn’t feel good when an opponent pulls out the rug, which is why these moments so often end up being ‘TSN turning points.’

More analytically, surprise is achieved through secrecy, concealment, deception, originality, audacity, and / or speed. These can be applied at the strategic or tactical levels, remembering that the strategic level entails those activities that directly contribute to achieving the aim. That said, surprise at the strategic level is infinitely more difficult to achieve since it’s so much more difficult to conceal the aim. Something like the preparations for the Battle of Mosul show that troop buildups take time and are difficult to conceal.

Still, in the rare instances when strategic surprise is achieved, it can be a game changer as it may require an extensive period of adaptation on the part of the adversary to figure out what’s going on and recover. Conversely, at the tactical level, surprise is much easier to achieve – a feint here, a fake there – but the resultant benefits and opportunities are much more fleeting.

So now that we understand a bit about the principle, how to apply this to what Steven Pressfield calls the inner creative battles with Resistance? After all, Resistance feeds off our fears, it knows what we know, so how can it be surprised?

Admittedly, short of some serious Tyler Durden-level psychological shenanigans, tactics like secrecy, concealment, and deception will be difficult to pull off. You can’t exactly hide your creative plans from yourself. And yet, while secrecy, deception, and concealment might not work, audacity, originality, and speed just may be effective if executed with the requisite fighting spirit and at the tactical level, the level of the battle or individual project. With that in mind, here are some suggestions that might put Resistance on its back foot.

Commit to short-term projects and launch them without over-thinking them, like entering National Novel Writing Month and write 50,000 words in the month of November. Go! Or do National Poetry Writing Month and write a poem a day for the month of April. Enter a short story competition; there are hundreds if not thousands. The best thing about the first two options is that nobody need ever read the works except yourself, yet they’ll still serve the aim of a short term campaign to overcome Resistance. There are many other examples, the point is to seize them as a forcing function to commit to an artistic pursuit.

Paralysis by Analysis

The danger in over-thinking these options is that the more time you take to analyze and figure out how you’re going to do it, the more time and opportunity Resistance has to get its shit together and shoot holes in your plan. Worse yet, Resistance may even surprise you by invoking some sort of fear-induced self-dramatization episode, which brings up a secondary, yet just as important, part of applying this principle.

Anticipate Surprises

Ask yourself this: what could happen right now that would stop you dead in your tracks from pursuing a creative calling. Is there a way you could handle that situation and still be able to write / paint / whatever? Even with this little bit of forethought, should that situation ever arise, you’re better prepared to handle it, if by nothing else than by it not being the first time you’ve considered the possibility.

This technique is one foundation of Resistance to Interrogation Training, which recognizes that hostages will be extremely disoriented from the shock of capture. By simulating the experience - even if it only entails talking through what to expect - resilience can be improved, and this tactic can work equally well for creative battles. In other words, to butcher a quote from General James Mattis, ‘Be polite, be professional, but have a plan to write every day no matter what.’

In any battle, creative or otherwise, it’s crucial to be on the lookout for every advantage. That means protecting oneself from surprise just as much as being bold and audacious when the situation calls for it. In the end, the principle of surprise is kind of like the Hail Mary of the principles of war; it’s difficult to pull off, but when it does work, it’s a game changer. Fortunately, for writers anyways, many of the options require far less work than digging a tunnel for two months.

Starting in 2009, the American military began surging an additional 33,000 personnel into theatre, a half-again increase of pre-surge troop levels of 68,000. With these extra boots on the ground, 2010 saw an increase in operations and tempo that pushed the Taliban back on their heels. Following this success, 2011 was supposed to be the year when these gains would become entrenched, thereby allowing the US to dial back on force levels during the summer of 2011, when the extra troops would start leaving while the Afghan security forces took the lead on operations.

Then the Taliban happened.

In April 2011, the Taliban executed a bold prison break at the Sarpoza prison in Kandahar city. That month, just before the start of the spring fighting season, over 400 Taliban prisoners broke-out through a tunnel, which had evidently taken months to build and was sophisticated enough to have electricity and ventilation.

A month later, the spring fighting season kicked off with a bang on 7 May, when a number of Taliban fighters simultaneously attacked multiple locations in Kandahar city, including the governor’s palace. The attack lasted for days and was reportedly conducted by many of the recently liberated prisoners of Sarpoza prison. Needless to say, this operation consumed the focus of Afghan and Coalition security forces, interrupting numerous other operations. Did it derail the overall coalition security plans? Not really, although it did creative an extensive blip in operational tempo. Did it stop the drawdown or transfer of responsibilities to the Afghans? Not at all. But what it did do, was send a strong message about the Taliban’s continued capability, a demoralizing effect that hurt the confidence of Afghan security forces. In doing so, it also demonstrated the principle of war known as surprise, a principle that’s equally effective in an artist’s creative battles.

A month later, the spring fighting season kicked off with a bang on 7 May, when a number of Taliban fighters simultaneously attacked multiple locations in Kandahar city, including the governor’s palace. The attack lasted for days and was reportedly conducted by many of the recently liberated prisoners of Sarpoza prison. Needless to say, this operation consumed the focus of Afghan and Coalition security forces, interrupting numerous other operations. Did it derail the overall coalition security plans? Not really, although it did creative an extensive blip in operational tempo. Did it stop the drawdown or transfer of responsibilities to the Afghans? Not at all. But what it did do, was send a strong message about the Taliban’s continued capability, a demoralizing effect that hurt the confidence of Afghan security forces. In doing so, it also demonstrated the principle of war known as surprise, a principle that’s equally effective in an artist’s creative battles.Surprise

The essence of surprise in a military sense is to strike an adversary at a time, place, or by a method for which they’re not prepared. By forcing the enemy to deal with something unfamiliar, surprise negatively impacts an adversary’s reaction time and hopefully drives them to make poor decisions. There’s a psychological aspect as well, as anyone who’s experienced surprise should be able to attest. Especially in a competitive sense, it doesn’t feel good when an opponent pulls out the rug, which is why these moments so often end up being ‘TSN turning points.’

More analytically, surprise is achieved through secrecy, concealment, deception, originality, audacity, and / or speed. These can be applied at the strategic or tactical levels, remembering that the strategic level entails those activities that directly contribute to achieving the aim. That said, surprise at the strategic level is infinitely more difficult to achieve since it’s so much more difficult to conceal the aim. Something like the preparations for the Battle of Mosul show that troop buildups take time and are difficult to conceal.

Still, in the rare instances when strategic surprise is achieved, it can be a game changer as it may require an extensive period of adaptation on the part of the adversary to figure out what’s going on and recover. Conversely, at the tactical level, surprise is much easier to achieve – a feint here, a fake there – but the resultant benefits and opportunities are much more fleeting.

So now that we understand a bit about the principle, how to apply this to what Steven Pressfield calls the inner creative battles with Resistance? After all, Resistance feeds off our fears, it knows what we know, so how can it be surprised?

Admittedly, short of some serious Tyler Durden-level psychological shenanigans, tactics like secrecy, concealment, and deception will be difficult to pull off. You can’t exactly hide your creative plans from yourself. And yet, while secrecy, deception, and concealment might not work, audacity, originality, and speed just may be effective if executed with the requisite fighting spirit and at the tactical level, the level of the battle or individual project. With that in mind, here are some suggestions that might put Resistance on its back foot.

Commit to short-term projects and launch them without over-thinking them, like entering National Novel Writing Month and write 50,000 words in the month of November. Go! Or do National Poetry Writing Month and write a poem a day for the month of April. Enter a short story competition; there are hundreds if not thousands. The best thing about the first two options is that nobody need ever read the works except yourself, yet they’ll still serve the aim of a short term campaign to overcome Resistance. There are many other examples, the point is to seize them as a forcing function to commit to an artistic pursuit.

Paralysis by Analysis

The danger in over-thinking these options is that the more time you take to analyze and figure out how you’re going to do it, the more time and opportunity Resistance has to get its shit together and shoot holes in your plan. Worse yet, Resistance may even surprise you by invoking some sort of fear-induced self-dramatization episode, which brings up a secondary, yet just as important, part of applying this principle.

Anticipate Surprises

Ask yourself this: what could happen right now that would stop you dead in your tracks from pursuing a creative calling. Is there a way you could handle that situation and still be able to write / paint / whatever? Even with this little bit of forethought, should that situation ever arise, you’re better prepared to handle it, if by nothing else than by it not being the first time you’ve considered the possibility.

This technique is one foundation of Resistance to Interrogation Training, which recognizes that hostages will be extremely disoriented from the shock of capture. By simulating the experience - even if it only entails talking through what to expect - resilience can be improved, and this tactic can work equally well for creative battles. In other words, to butcher a quote from General James Mattis, ‘Be polite, be professional, but have a plan to write every day no matter what.’

In any battle, creative or otherwise, it’s crucial to be on the lookout for every advantage. That means protecting oneself from surprise just as much as being bold and audacious when the situation calls for it. In the end, the principle of surprise is kind of like the Hail Mary of the principles of war; it’s difficult to pull off, but when it does work, it’s a game changer. Fortunately, for writers anyways, many of the options require far less work than digging a tunnel for two months.

Published on February 12, 2017 09:42

February 5, 2017

Keep Your Chin Tucked

"War is an act of violence pushed to its utmost bounds."

Carl von Clausewitz, On War. In 2002, suicide bombers were unheard of in Afghanistan. But in 2005, the tactic began to creep in from the neighbouring conflict in the Iraqi theatre of war. As the years dragged on, the tactic continued to evolve; using women, remote control detonators, and even children. Almost invariably, far more civilians perished in suicide attacks than the intended targets, all collateral damage. To many, this practice was one of the most feared and disgusting tactics to be employed be the Taliban, an unconstrained use of force not because of the power of the weapon itself, but in the cynical view of life that its use required.

In 2002, suicide bombers were unheard of in Afghanistan. But in 2005, the tactic began to creep in from the neighbouring conflict in the Iraqi theatre of war. As the years dragged on, the tactic continued to evolve; using women, remote control detonators, and even children. Almost invariably, far more civilians perished in suicide attacks than the intended targets, all collateral damage. To many, this practice was one of the most feared and disgusting tactics to be employed be the Taliban, an unconstrained use of force not because of the power of the weapon itself, but in the cynical view of life that its use required.

A popular Clausewitz quote on this subject is that a combatant who uses force without restraint will necessarily gain the advantage over an opponent who is more constrained. From this comes Clausewitz’s first reciprocal action, which is that in theory, opponents will meet each other’s uses of force with the same or greater uses of force, until both combatants are at extremes of violence. Ultimately, this is the conceptual foundation for the idea of absolute war.

But in practice, this doesn't happen. In Afghanistan, the coalition didn’t respond to the suicide bomber threat by laying waste to everyone who approached a checkpoint because war isn’t about all-out aggression except in very finite scenarios. From a practical standpoint, no different than in boxing or martial arts, combatants typically have to mix equal parts of offence and defence, protecting their own assets so they can be unleashed at a time and place of their choosing. In Afghanistan, the coalition was protecting its relationship to the populace, a necessity in counter-insurgency, but each situation will be different.

This is the Principle of War known as Security, and it can be just as important in an artist’s inner creative battles with Resistance as any of the others. Security

The principle of security entails protecting oneself against enemy interference. Whatever task a force is doing, this principle recognizes that it’ll need certain assets - or combat power - to get that job done and suggests that it had best preserve those assets so they can be there when needed. In military parlance, this is called protecting combat power in order to provide the freedom of action necessary to take the initiative. In so doing, a combatant seeks to manage risk and avoid surprise.

Of course, combat power isn’t some amorphous blob; it’s composed of real things, ships, tanks, planes. While all of these things have their place, it’s impossible to protect everything, all the time. There’s never enough security to go around, so priorities have to be established to make sure the most important things get protected accordingly. This, in turn, leads to the designation of high value assets, something that contributes directly to achieving the aim.

Think of ‘high-value assets’ this way; if the mission can’t be done without having a certain unit or capability, like ballistic missile submarines to conduct nuclear deterrence, then that asset is high value and should be protected as such.

This concept can be equally applied to an artist's creative battles with Resistance.

Consider the aim of writing as a creative calling. What are the assets, or requirements, that directly contribute to the achievement of this goal? Here’s a few, in no particular order:

A writer needs a place to write. A writer needs time to write. In order to bounce back from the injuries that Resistance will inflict, a writer probably also needs support and desire, or moral forces.

By no means exhaustive, these critical requirements contribute directly to the goal of being a writer, and could therefore be designated as high value assets. Applying the principle of security will suggest that these assets be protected so they're available to defeat Resistance. So what does that look like?

Find a place to work, somewhere that is yours and which is used for writing. This suggestion pops up all the time in books on writing, from Stephen King to Anne Lamott to Julia Cameron. Not to put too fine a point on it, but they are on to something, so protect that space.

Set a time to write. Again, it’s difficult to count the number of books or quotes on writing that extol the benefits of having a routine. Here's a good one attributed to William Faulkner:

'I only write when inspiration strikes. Fortunately it strikes every morning at nine o'clock.' Maybe it should be every day, maybe not, but however frequent it is, it should be often

enough that it becomes a routine because that develops resilience and resilience will help you get through the times when sitting down at the desk is the last thing you want to do. Protect that time or lose it.

On to support; ever heard of a battle buddy? It’s a soldier’s partner, someone for whom there’s a reciprocal responsibility to help each other survive and do the best they can while accomplishing their mission. They can force you to slow down if you’re burning too hot or kick your ass when you want to quit. In this case it could be a spouse, a close friend, even somebody met through a writer’s group, but it's someone who know what you're trying to accomplish and will support you in that endeavor. Whoever that person is, protect that relationship.

In the end, the requirements each individual needs to accomplish their goals will be slightly different. Yes, there are likely going to be parallels, but the fundamental similarity is that whatever those ingredients to success are, they need to be protected. We know that Resistance is going to oppose us; what we’re trying to avoid is making it easy, giving Resistance ways to subvert us without making it work for its victories. Just like a boxer protects against an easy knockout by keeping their chin tucked, a writer can protect against defeat by securing a time and a place to write.

[i] Von Clausewitz, Carl, On War, Penguin Books, Ltd, London: 1982, p. 103.

Carl von Clausewitz, On War.

In 2002, suicide bombers were unheard of in Afghanistan. But in 2005, the tactic began to creep in from the neighbouring conflict in the Iraqi theatre of war. As the years dragged on, the tactic continued to evolve; using women, remote control detonators, and even children. Almost invariably, far more civilians perished in suicide attacks than the intended targets, all collateral damage. To many, this practice was one of the most feared and disgusting tactics to be employed be the Taliban, an unconstrained use of force not because of the power of the weapon itself, but in the cynical view of life that its use required.

In 2002, suicide bombers were unheard of in Afghanistan. But in 2005, the tactic began to creep in from the neighbouring conflict in the Iraqi theatre of war. As the years dragged on, the tactic continued to evolve; using women, remote control detonators, and even children. Almost invariably, far more civilians perished in suicide attacks than the intended targets, all collateral damage. To many, this practice was one of the most feared and disgusting tactics to be employed be the Taliban, an unconstrained use of force not because of the power of the weapon itself, but in the cynical view of life that its use required.A popular Clausewitz quote on this subject is that a combatant who uses force without restraint will necessarily gain the advantage over an opponent who is more constrained. From this comes Clausewitz’s first reciprocal action, which is that in theory, opponents will meet each other’s uses of force with the same or greater uses of force, until both combatants are at extremes of violence. Ultimately, this is the conceptual foundation for the idea of absolute war.

But in practice, this doesn't happen. In Afghanistan, the coalition didn’t respond to the suicide bomber threat by laying waste to everyone who approached a checkpoint because war isn’t about all-out aggression except in very finite scenarios. From a practical standpoint, no different than in boxing or martial arts, combatants typically have to mix equal parts of offence and defence, protecting their own assets so they can be unleashed at a time and place of their choosing. In Afghanistan, the coalition was protecting its relationship to the populace, a necessity in counter-insurgency, but each situation will be different.

This is the Principle of War known as Security, and it can be just as important in an artist’s inner creative battles with Resistance as any of the others. Security

The principle of security entails protecting oneself against enemy interference. Whatever task a force is doing, this principle recognizes that it’ll need certain assets - or combat power - to get that job done and suggests that it had best preserve those assets so they can be there when needed. In military parlance, this is called protecting combat power in order to provide the freedom of action necessary to take the initiative. In so doing, a combatant seeks to manage risk and avoid surprise.

Of course, combat power isn’t some amorphous blob; it’s composed of real things, ships, tanks, planes. While all of these things have their place, it’s impossible to protect everything, all the time. There’s never enough security to go around, so priorities have to be established to make sure the most important things get protected accordingly. This, in turn, leads to the designation of high value assets, something that contributes directly to achieving the aim.

Think of ‘high-value assets’ this way; if the mission can’t be done without having a certain unit or capability, like ballistic missile submarines to conduct nuclear deterrence, then that asset is high value and should be protected as such.

This concept can be equally applied to an artist's creative battles with Resistance.

Consider the aim of writing as a creative calling. What are the assets, or requirements, that directly contribute to the achievement of this goal? Here’s a few, in no particular order:

A writer needs a place to write. A writer needs time to write. In order to bounce back from the injuries that Resistance will inflict, a writer probably also needs support and desire, or moral forces.

By no means exhaustive, these critical requirements contribute directly to the goal of being a writer, and could therefore be designated as high value assets. Applying the principle of security will suggest that these assets be protected so they're available to defeat Resistance. So what does that look like?

Find a place to work, somewhere that is yours and which is used for writing. This suggestion pops up all the time in books on writing, from Stephen King to Anne Lamott to Julia Cameron. Not to put too fine a point on it, but they are on to something, so protect that space.

Set a time to write. Again, it’s difficult to count the number of books or quotes on writing that extol the benefits of having a routine. Here's a good one attributed to William Faulkner:

'I only write when inspiration strikes. Fortunately it strikes every morning at nine o'clock.' Maybe it should be every day, maybe not, but however frequent it is, it should be often

enough that it becomes a routine because that develops resilience and resilience will help you get through the times when sitting down at the desk is the last thing you want to do. Protect that time or lose it.

On to support; ever heard of a battle buddy? It’s a soldier’s partner, someone for whom there’s a reciprocal responsibility to help each other survive and do the best they can while accomplishing their mission. They can force you to slow down if you’re burning too hot or kick your ass when you want to quit. In this case it could be a spouse, a close friend, even somebody met through a writer’s group, but it's someone who know what you're trying to accomplish and will support you in that endeavor. Whoever that person is, protect that relationship.

In the end, the requirements each individual needs to accomplish their goals will be slightly different. Yes, there are likely going to be parallels, but the fundamental similarity is that whatever those ingredients to success are, they need to be protected. We know that Resistance is going to oppose us; what we’re trying to avoid is making it easy, giving Resistance ways to subvert us without making it work for its victories. Just like a boxer protects against an easy knockout by keeping their chin tucked, a writer can protect against defeat by securing a time and a place to write.

[i] Von Clausewitz, Carl, On War, Penguin Books, Ltd, London: 1982, p. 103.

Published on February 05, 2017 10:26

January 29, 2017

Step Into The Arena

There was no shortage of fighting spirit during Canada’s engagement in Afghanistan. Attacks, raids, cordons and searches, reconnaissance operations; every day offensive actions were happening to wear down the enemy.

There was no shortage of fighting spirit during Canada’s engagement in Afghanistan. Attacks, raids, cordons and searches, reconnaissance operations; every day offensive actions were happening to wear down the enemy.And yet, for all this activity, the Taliban endured and today, they remain a viable fighting force, fed and nurtured from generally unreachable safe havens. So was all that offensive activity redundant? A Sisyphean task fed by blood, sweat, and tears?

Far from it.

Success is generally only possible through action, through taking the initiative and holding onto it as if the dogs of hell were in pursuit. This imperative toward action, separate and yet interrelated to the overall aim of the war, is what is embodied in the principle of Offensive Action. Here’s how it can be applied to the inner creative battle with Resistance.

The Offensive

Military doctrine publications define offensive action as the key to defeating an opponent and a prerequisite for success. Impressive-sounding phrases are invariably used, such as offensive action achieving decisive results and preserving freedom of maneuver. But what does all this gobbledygook mean?

It means taking the initiative. It’s about being proactive, not reactive. And once one has the initiative, it’s about keeping it. Yes, there is a time and place for being reactive, such as when buying time, but even then, the seeds must be sown to regain one’s feet. In this case it’s about waiting for an opportunity, holding off until the right conditions, the right opening, presents. And when that happens, hesitation is antithetical with success.

The principle of offensive action does not guarantee that the right actions will be taken, nor does it help recognize when opportunities are presenting. Both of these situations require judgement, which more often than not must be informed by and synchronized with the other principles of war, most especially Selection and Maintenance of the Aim. What’s more, in any battle, the enemy gets a vote. That said, a tendency toward restraint - sometimes called ‘risk-aversion’ - may result in opportunities being bypassed and a general inducement of paralysis by analysis. At a certain point, one has to say, “Damn the torpedoes,” and let the chips fall where they may.

In Clausewitzian theory, the offence has both macro and micro levels, corresponding to the strategic and tactical offences. A strategic offence is any action leading directly to the overall objective, or reason for which the war is being waged. A tactical offence is any action that does not lead directly to the overall objective. By extension, there are also strategic and tactical defences. In his book, On Strategy, Colonel Harry G. Summers Jr. explains how the American strategy of containment during the Cold War was strategically defensive as it did not directly attack the adversary. And yet, it was still possible to go on the tactical offence through a sort-of long term war of indirect attrition in proxy campaigns.

Aside from assessments on how well this theory might explain the collapse of the Soviet Union, the key takeaway from this analysis is to know whether one is on, or should take, the offence or defence. That is, it is important to know what type of war is being fought.

Application

To apply the principle of offensive action to inner creative battles, first, remember the aim; to pursue a creative calling.

Second, remember the enemy. Clausewitz writes of defeating an enemy through the destruction of their forces, through the occupation of their territory, or through the annihilation of their will to resist. Thanks to Mr. Steven Pressfield, we know that our enemy, Resistance, has no territory to occupy. Resistance has no forces. What Resistance does have is will to defy us, in spades and inversely proportional to our fear.

Third, apply a strategy that delivers the aim while taking into account likely enemy actions.

In this case, the strategy is to write, which leads directly to the goal but unfortunately does not destroy the enemy’s will to resist. Although we can achieve short term victories, Resistance will return every day to exploit our weaknesses in its own bid to kill our creative spark.

Thus, we are on the strategic defence. The best we can hope for is to contain Resistance, depriving it of the fuel it needs to survive, but never quite extinguishing it outright.

Resistance, on the other hand, is on the strategic offence. It wants to shut us down for good and it has the tools to do so. That doesn't mean we can't win.

Resistance reacts to us – the harder we push, the harder it resists. This is important, because Resistance is reactive, it's on the tactical defence and therein lies an opportunity to seize the initiative through the tactical offence. Take action. If you’re a writer, pick up the pen (a much more compelling image than, ‘turn on your word processor…’) and write. Each pen stroke, each type of the keyboard is a shot fired, an artillery fire mission called in. At a certain point, Resistance will fly the white flag, at least for a day. Then it will be time to consolidate on position, then prepare for the next day's battle.

But it won’t be easy.

It's true that the adversary should never be underestimated and Resistance will deploy all its resources in opposition to our action. Fear, guilt, procrastination; all these weapons effects will be brought to bear to induce our own paralysis, nulling our activity and gradually wresting the initiative from our grasp. And since an object at rest tends to stay at rest, once Resistance gets us to stop, it is exponentially more difficult to get started again.

In Steven Pressfield’s book, The War of Art, there’s a section entitled, ‘A Professional Acts in the Face of Fear.’ This is ultimately what the principle of offensive action is about. There is one cure, one tactic that Resistance cannot beat, and that’s to do the activity that Resistance is seeking to stop. It’s okay to have fear – indeed, have a healthy respect for fear – but do not be afraid. Respect your enemy, yes. Fear them, yes. But act nonetheless. Write. Paint. Sing. Whatever is the endstate of your inner creative battle, Just Do It.

As Afghanistan has shown to so many countries over time, action alone is no guarantor of success. The corollary, however, is that you almost certainly cannot reach your goals if you do not act.

Published on January 29, 2017 10:27

January 22, 2017

Kandahar Boardwalk: Morale Builder or Distraction?

A few weeks ago, various media outlets announced that the Kandahar Airfield ball hockey rink would be repatriated and displayed for posterity in the Canadian War Museum. The hockey rink was built during Canada’s deployment of military forces to Afghanistan and occupied prime territory in the middle of the Kandahar boardwalk.  The best KFC and T.G.I.Friday's in Kandahar! So what was the boardwalk?

The best KFC and T.G.I.Friday's in Kandahar! So what was the boardwalk?

It was a place to relax at Kandahar Airfield, built around an outdoor track, where visitors could gaze out upon the hockey rink, but also a beach volleyball court, a basketball court, and even, later, a soccer field. ATMs stood nearby for troops and contractors to access money for any number of local tourist shops selling DVDs, electronics, video games, clothing, jewelry, handcrafted mementos, or carpets. For food, Airfield residents could have their choice of pizza, Mexican, Lebanese, Indian, or enjoy North American staples like KFC and TGIFriday’s. And coffee, don’t forget coffee, including Tim Horton’s (for a time), Green Beans, and a number of national cafés.

Yes, for a time, the boardwalk was pretty big, maybe even bigger than the war itself.

In 2010, General Stan McChrystal, then the Commander of ISAF, tried to kill the boardwalk, ordering several franchises (the US ones) to shut down. In his view, the fast food not only made troops soft, it was also an unnecessary logistical burden that made it more difficult to support the troops in the field. His Command Sergeant-Major noted that, “This is a war zone, not an amusement park.”

Six months after giving the order, General McChrystal was gone and the boardwalk was expanding, all in the name of maintaining morale.

Is this, then, what Clausewitz envisioned when he wrote of the importance of moral forces and spirit to the success of an Army? Being able to come off patrol and get a grandé, non-fat caramel latte?

And yet, not without reason, Maintenance of Morale is often regarded as the second most important principal of war after Selection and Maintenance of the Aim. As history has shown, success is often about more than numbers, weapon systems, and physical resources, all of which can’t make up for a lack of courage, determination, and perseverance.

Maintenance of Morale

Clausewitz stated that war had both a physical and moral component. Although combat was conducted in the physical medium, it was more truly a trial of both physical and moral forces, with many practitioners choosing the moral component as more important. In his 1967 book Morale, Sir John Baynes wrote that “…the truth is that a brilliant plan of battle in a tactical sense can be a complete failure if morale is bad, while a poor plan can be made to work well if morale is good.” Perhaps this is why morale is often identified as the next most important element after leadership in promoting fighting spirit and the will to win.

As for Clausewitz, he argued that spirit could only be generated from two sources, a string of victories and incessant activity. Strict discipline, smartness, or cultivated pride had their places in peacetime or in garrison, but were poor stand-ins for what was needed in battle, perhaps even counter-productive. These latter elements could polish the blade, but could never temper it, nor change the blade’s mettle. This view is reflected in UK definitions of the principle of morale, which stresses a shared sense of purpose and values, feeling of worth, and group cohesion.

Confidence, discipline, sense of purpose, success, leadership, material support; all these factors play a role in maintaining morale. And yet, it is undeniable that morale is particularly sensitive to material conditions, or more specifically, the lack thereof. But can an army be too well-cared for? Can it play too much ball-hockey, eat too much KFC?

Depends on the enemy.

In battle, the destruction of an enemy’s moral forces – their will – is the ultimate determinant of victory, arguably above even the destruction of their physical forces. Therefore, any targeting of the enemy should always include targets that affect their moral forces as well. The opposite to this maxim is that the enemy will seek to destroy our own morale and spirit.

Our enemy, Resistance, will seek to break our morale. It will introduce dissonance and confusion in a bid to make us inactive. Resistance would have us believe that the commitment to, and pride in, our mission to be creatives is inconsistent with the sacrifices made and the absence of desired results. It will say, “Why are you getting up at four in the morning to write / paint / design? You haven’t sold anything. Why not stay in bed a few more hours?” Resistance’s tactic is to make us feel like failures.

The insidious part of this tactic is that it plays to our fears, many of which are legitimate. What are you not doing because you’re writing / singing / painting? Missing your kid’s swim class? Ignoring your spouse? Not hitting the gym? It is psychological warfare at its best because it is grounded in truth.

But, we can resist by maintaining our fighting spirit, our morale.

The temptation will be to keep our morale high through the easiest methods. Cue physical comforts; alcohol, food, sex, Maslow’s first few levels of needs. And yet, all of these methods, when taken to their utmost conclusion, eventually distract us from our aim. We can be too well-cared for, smothered in kindness. It’s like the yin/yang of martial art training in that it is sometimes necessary to attack your opponent with the goal of hurting them so they can practice with true feeling. The goon on the street who ambushes you isn’t ‘half’ trying to kill you; they’re all in. Likewise, failing to properly attack your opponent in training does them no favours if their goal is to become better martial artists; it only provides a false sense of security. In this case, we have to try and hurt the ones we love to help them become stronger. So too, I would argue, with physical comforts. They certainly have their place, but they're not an answer by themselves.

Instead, maintenance of morale is accomplished by two things, victory and activity. The second one leads to the first. Remember our own aim versus the aim of Resistance. Resistance's aim is to stop us from reaching our creative calling; it wants to destroy our morale – our moral forces. Our aim is to pursue our calling and our strategy is to do the activity, what Steven Pressfield calls, ‘doing the work.’ Did we write today? Did we read today? If not, what did we do to become better writers? Anything? Then be proud of that, we beat Resistance for another day. Maybe it was a small win, but it’s still a win, so celebrate it. Over time, that activity will become habit and those small victories will add up, resulting in fighting spirit. The end result will be a lean, mean, creative-pursuit focused machine, a much more difficult nut for Resistance to crack.

Of course, there’s nothing wrong with taking a break to down a cappuccino / hit the gym / play ball hockey. The fine line is whether that activity is directly contributing to meeting your aim. Grabbing a coffee to push through a late night of editing? All good. Not able to write because of a hangover? Maybe not so much. In the end, only you can be judge.

The best KFC and T.G.I.Friday's in Kandahar! So what was the boardwalk?

The best KFC and T.G.I.Friday's in Kandahar! So what was the boardwalk?It was a place to relax at Kandahar Airfield, built around an outdoor track, where visitors could gaze out upon the hockey rink, but also a beach volleyball court, a basketball court, and even, later, a soccer field. ATMs stood nearby for troops and contractors to access money for any number of local tourist shops selling DVDs, electronics, video games, clothing, jewelry, handcrafted mementos, or carpets. For food, Airfield residents could have their choice of pizza, Mexican, Lebanese, Indian, or enjoy North American staples like KFC and TGIFriday’s. And coffee, don’t forget coffee, including Tim Horton’s (for a time), Green Beans, and a number of national cafés.

Yes, for a time, the boardwalk was pretty big, maybe even bigger than the war itself.

In 2010, General Stan McChrystal, then the Commander of ISAF, tried to kill the boardwalk, ordering several franchises (the US ones) to shut down. In his view, the fast food not only made troops soft, it was also an unnecessary logistical burden that made it more difficult to support the troops in the field. His Command Sergeant-Major noted that, “This is a war zone, not an amusement park.”

Six months after giving the order, General McChrystal was gone and the boardwalk was expanding, all in the name of maintaining morale.

Is this, then, what Clausewitz envisioned when he wrote of the importance of moral forces and spirit to the success of an Army? Being able to come off patrol and get a grandé, non-fat caramel latte?

And yet, not without reason, Maintenance of Morale is often regarded as the second most important principal of war after Selection and Maintenance of the Aim. As history has shown, success is often about more than numbers, weapon systems, and physical resources, all of which can’t make up for a lack of courage, determination, and perseverance.

Maintenance of Morale

Clausewitz stated that war had both a physical and moral component. Although combat was conducted in the physical medium, it was more truly a trial of both physical and moral forces, with many practitioners choosing the moral component as more important. In his 1967 book Morale, Sir John Baynes wrote that “…the truth is that a brilliant plan of battle in a tactical sense can be a complete failure if morale is bad, while a poor plan can be made to work well if morale is good.” Perhaps this is why morale is often identified as the next most important element after leadership in promoting fighting spirit and the will to win.

As for Clausewitz, he argued that spirit could only be generated from two sources, a string of victories and incessant activity. Strict discipline, smartness, or cultivated pride had their places in peacetime or in garrison, but were poor stand-ins for what was needed in battle, perhaps even counter-productive. These latter elements could polish the blade, but could never temper it, nor change the blade’s mettle. This view is reflected in UK definitions of the principle of morale, which stresses a shared sense of purpose and values, feeling of worth, and group cohesion.

Confidence, discipline, sense of purpose, success, leadership, material support; all these factors play a role in maintaining morale. And yet, it is undeniable that morale is particularly sensitive to material conditions, or more specifically, the lack thereof. But can an army be too well-cared for? Can it play too much ball-hockey, eat too much KFC?

Depends on the enemy.

In battle, the destruction of an enemy’s moral forces – their will – is the ultimate determinant of victory, arguably above even the destruction of their physical forces. Therefore, any targeting of the enemy should always include targets that affect their moral forces as well. The opposite to this maxim is that the enemy will seek to destroy our own morale and spirit.

Our enemy, Resistance, will seek to break our morale. It will introduce dissonance and confusion in a bid to make us inactive. Resistance would have us believe that the commitment to, and pride in, our mission to be creatives is inconsistent with the sacrifices made and the absence of desired results. It will say, “Why are you getting up at four in the morning to write / paint / design? You haven’t sold anything. Why not stay in bed a few more hours?” Resistance’s tactic is to make us feel like failures.

The insidious part of this tactic is that it plays to our fears, many of which are legitimate. What are you not doing because you’re writing / singing / painting? Missing your kid’s swim class? Ignoring your spouse? Not hitting the gym? It is psychological warfare at its best because it is grounded in truth.

But, we can resist by maintaining our fighting spirit, our morale.

The temptation will be to keep our morale high through the easiest methods. Cue physical comforts; alcohol, food, sex, Maslow’s first few levels of needs. And yet, all of these methods, when taken to their utmost conclusion, eventually distract us from our aim. We can be too well-cared for, smothered in kindness. It’s like the yin/yang of martial art training in that it is sometimes necessary to attack your opponent with the goal of hurting them so they can practice with true feeling. The goon on the street who ambushes you isn’t ‘half’ trying to kill you; they’re all in. Likewise, failing to properly attack your opponent in training does them no favours if their goal is to become better martial artists; it only provides a false sense of security. In this case, we have to try and hurt the ones we love to help them become stronger. So too, I would argue, with physical comforts. They certainly have their place, but they're not an answer by themselves.

Instead, maintenance of morale is accomplished by two things, victory and activity. The second one leads to the first. Remember our own aim versus the aim of Resistance. Resistance's aim is to stop us from reaching our creative calling; it wants to destroy our morale – our moral forces. Our aim is to pursue our calling and our strategy is to do the activity, what Steven Pressfield calls, ‘doing the work.’ Did we write today? Did we read today? If not, what did we do to become better writers? Anything? Then be proud of that, we beat Resistance for another day. Maybe it was a small win, but it’s still a win, so celebrate it. Over time, that activity will become habit and those small victories will add up, resulting in fighting spirit. The end result will be a lean, mean, creative-pursuit focused machine, a much more difficult nut for Resistance to crack.

Of course, there’s nothing wrong with taking a break to down a cappuccino / hit the gym / play ball hockey. The fine line is whether that activity is directly contributing to meeting your aim. Grabbing a coffee to push through a late night of editing? All good. Not able to write because of a hangover? Maybe not so much. In the end, only you can be judge.

Published on January 22, 2017 10:11

January 15, 2017

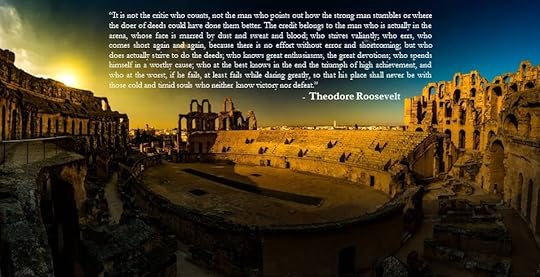

Author Interview: Gregory Taylor

This week's author interview is with Gregory Taylor, a local author from Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. Gregory is a mathematics teacher with a Bachelor of Mathematics from the University of Waterloo, as well as a Bachelor of Education from Queen’s University. Gregory’s been an editor and serial writer, he was a Chief Scriptwriter for Faculty, Alumni, Staff, and Students (FASS), and won the Grand Prize for fan fiction at Anime North. He’s also currently writing a time-travel serial, and a web-comic that personifies mathematics. What made you decide to sit down and actually start writing?

This week's author interview is with Gregory Taylor, a local author from Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. Gregory is a mathematics teacher with a Bachelor of Mathematics from the University of Waterloo, as well as a Bachelor of Education from Queen’s University. Gregory’s been an editor and serial writer, he was a Chief Scriptwriter for Faculty, Alumni, Staff, and Students (FASS), and won the Grand Prize for fan fiction at Anime North. He’s also currently writing a time-travel serial, and a web-comic that personifies mathematics. What made you decide to sit down and actually start writing? It was probably some assignment as a youth; I still remember a time travel story I wrote in middle school. I’ve never really stopped. Assignment writing became fanfiction and scriptwriting in University, then summaries of role-play sessions and work in secretary positions after that, and as the web got bigger, it was on to blogs for both fiction and non-fiction subjects. Some people paint or garden as a hobby; I write.

What is the hardest thing about writing?

For me, the hardest thing is figuring out short, stand-alone pieces. I always see potential in spinning minor details into their own larger story, weaving worlds together or expanding on character backstories. It’s great for serials, less great when you have to convey everything within a word limit or genre requirement. What doesn’t help is that I rarely have an ending in mind when I start, so any limits can prevent my characters from guiding me to a satisfying conclusion.

What’s the best piece of advice you’ve received?

Don’t quit your day job. Granted, I’ve never been in a position where I could consider writing as a full time endeavour, but I have seen the post of another where it went badly. Also, I know of “survivorship bias”, where we tend to take our lessons from whatever happens to survive/succeed out there, rather than learning from the larger pool of failures. Partly that’s because the failures of others go unreported in the age of social media, but the bigger issue is, we don’t properly weight things like timing or random chance. (I believe Alastair himself has said it’s important to learn from one’s mistakes.) For the record, my day job is teaching high school statistics. Related, if you don’t like your day job, you might want to consider an extended vacation (or changing it) before giving it all up to write. What advice would you give to aspiring writers?

Keep a file or directory of your successful moments. Screenshots of tweets sent to you, beta reader comments, journal entries, whatever. I’m not saying to disregard the more negative experiences in favour of those ones, but the low points tend to stick around longer. Having that directory will give you something to look back on during long stretches of silence or even despair, when you feel like giving up. When that feeling hits, you can go back to that directory and say “this person read that, and liked it, so I’m not as terrible at this as I believe I am”. The corrollary to that is to keep at it.

What is your least favorite part of the writing process?

Marketing. These days it’s less a reluctance to talk about my writing, and more the need to distil everything down into a synopsis or elevator pitch that catches someone’s attention for longer than five seconds. Also, knowing where and when to shop such pitches around. I’m not only terrible at it, I tend to fixate in the wrong places, and it doesn’t help that I feel like my writing won’t fit into any of the typical marketing boxes.

Can you please describe your current project?

I write serials, that is, stories with entries that come out every week. In theory each entry can stand alone, but they work best as a whole experience. These days, more and more television programs (and anime) follow that format; think also of the Marvel cinematic universe. My two current efforts are:Book 4 of my time travel serial (“Time & Tied”) which is posting twice weekly on my Wordpress website. It’s urban fantasy (or “temporal fantasy” as I call it) which could also fit into YA (young adult) since it’s centred on a group of present day high school students. In Book 1, they find a time machine. Eventually, they learn it originated at the time of a future war, and one of the teens learns she is tied into a related temporal destiny. It’s actually a rewrite of an effort I began in university, then did periodic work on from 2000-2009; I had to edit it before I started posting (in 2015) to update technology and remove hard date references. (There’s a multiverse story that alternates with T&T on that same website, called “Epsilon Project”. That one’s based on interactive audience votes, and has as a basis a number of characters from my old stories and roleplay campaigns.)

Click cover for more info Personified mathematics (“math-tans”). What if mathematical functions were people, whose actions were indirectly influenced by events in our world? For four years, that premise arced through a number of storylines, including the parabola being kidnapped from the polynomials, mathematical song parodies, and a voyage in Logan’s base to Fractal City. It was shelved for lack of readership, but has returned as a webcomic, now that I can draw a little better. So it’s been around for over five years now. (This is how I don’t fit into the marketing boxes.)

Click cover for more info Personified mathematics (“math-tans”). What if mathematical functions were people, whose actions were indirectly influenced by events in our world? For four years, that premise arced through a number of storylines, including the parabola being kidnapped from the polynomials, mathematical song parodies, and a voyage in Logan’s base to Fractal City. It was shelved for lack of readership, but has returned as a webcomic, now that I can draw a little better. So it’s been around for over five years now. (This is how I don’t fit into the marketing boxes.)  How can readers discover more about you and your work?

How can readers discover more about you and your work?Website: https://mathtans.wordpress.com

Blog: http://mathiex.blogspot.ca

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/mathstans/

Twitter: https://twitter.com/mathtans

Wattpad: https://www.wattpad.com/user/mathtans

Published on January 15, 2017 11:40

Eyes on the Prize

As part of the series on applying the Principles of War to the business of writing, this week looks at the first principle, Selection and Maintenance of the Aim.

What was the aim of Canada’s mission in Afghanistan? Consider:Canada sent forces to Afghanistan in late-2001 / early-2002 as part of Operation Enduring Freedom. The aim of the US-led mission was to dismantle the Al-Qaeda terrorist network in Afghanistan and remove the Taliban from power. When the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA) stood up in late-2002, the aim expanded to include assisting the Afghanistan transition to new leadership. Included in this mandate was the coordination of peace and reconciliation efforts, and also humanitarian assistance. From 2003 to 2004, the aim was to let the fledgling Afghan government develop its constitution and focus on its first elections, with the Canadian focus being on providing security around Kabul. In 2005, Canada’s aim changed to reflect the broader mandate of the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF). The mandate included not only assisting in the provision of security, but in governance and development as well. For Canada, these activates were realized in two primary ways, the conduct of combat operations and through a Provincial Reconstruction Team, both based in Kandahar province. In 2011, the aim remained on provision of security, development, and governance, but the execution changed from primarily combat operations to the training of Afghani national security forces. In 2014, Canada ceased its activities in Afghanistan.

What was the aim of Canada’s mission in Afghanistan? Consider:Canada sent forces to Afghanistan in late-2001 / early-2002 as part of Operation Enduring Freedom. The aim of the US-led mission was to dismantle the Al-Qaeda terrorist network in Afghanistan and remove the Taliban from power. When the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA) stood up in late-2002, the aim expanded to include assisting the Afghanistan transition to new leadership. Included in this mandate was the coordination of peace and reconciliation efforts, and also humanitarian assistance. From 2003 to 2004, the aim was to let the fledgling Afghan government develop its constitution and focus on its first elections, with the Canadian focus being on providing security around Kabul. In 2005, Canada’s aim changed to reflect the broader mandate of the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF). The mandate included not only assisting in the provision of security, but in governance and development as well. For Canada, these activates were realized in two primary ways, the conduct of combat operations and through a Provincial Reconstruction Team, both based in Kandahar province. In 2011, the aim remained on provision of security, development, and governance, but the execution changed from primarily combat operations to the training of Afghani national security forces. In 2014, Canada ceased its activities in Afghanistan.

As of this writing, the Taliban is still an effective adversary in Afghanistan. Indeed, some reports suggest that 2016 may have been a banner year for the Taliban, with the force able to take back more territory than at any time since the 15-year campaign began.

So did Canada meet its aim Afghanistan?

The Objective

The overriding Principle of War is, ‘The Selection and Maintenance of the Aim.’ Whether in the conduct of war as a whole, or in the smallest supporting operation, it is essential to understand what the force is trying to achieve. Not only does this prevent a force from working at cross-purposes, it also ensures scarce resources are efficiently assigned to necessary activities.

Ideally, the aim should be clearly defined, simple, and direct. The acronym SMART applies: Specific, Measurable, Agreed Upon, Realistic, and Time-Based. (Note: there are multiple variations in the acronym – the version presented avoids A = attainable because of conceptual overlap with a goal being Realistic). Removing the Taliban from power is a specific and measurable goal. Assisting in the provision of security, development, and governance is not, or at least it’s much harder to express in terms of SMART criteria.

In theory, the aim cascades through the levels of conflict. The political level sets the overall objective, with the various instruments of national power – diplomatic, informational, military, economic – determining how best to achieve that goal. In turn, this unifying theme extends downward through the strategic, operational, and tactical levels to individual actors actually doing things on the battlefield; the so-called ‘strategic corporals.’

Some terminology:

The goal, or aim, or objective, is what defines a win; it’s what the force wants to happen. The goal can change as the situation evolves. Goals come with parameters, things that need to either happen, or not happen, like obeying laws.

Strategy is the general plan to accomplish a goal. It is executed through tactics, the how or actual activities that accomplish things. Strategy is constrained by the environment; a plan that works in one environment might not be appropriate in another. Lastly, tactics break up into individual techniques, the multitude of individual actions that can be taken as a result of minute to minute changes in the environment.

Goals and parameters dictate strategy.Strategy and environment dictate tactics.Tactics and the minute-to-minute situation dictate techniques.

At every level, there must be an appreciation for the overall aim and how the smallest technique supports the broader intent. Any deviation from rowing forward represents effort that’s at cross-purposes.

It is possible that the aim will change. This is natural and should not be a surprise. This is why the military’s analysis method, the estimate process, has a built-in check: ‘has the situation changed and is the mission still valid?’ That said, should a new aim be required, it should be similarly clear, simple, and direct; almost more so since it’s introducing change.

Using the Principle Against Resistance

The war with Resistance is for keeps. Make no mistake, as an internally generated expression of human self-sabotage, Resistance intuitively understands the nature of war and conflict far better than people consciously understand those same concepts. This includes the understanding that it must bend us to its will, it must compel us to do what it wants. That’s how it wins.

And what does Resistance want? To stop us from pursuing a creative calling.

Our goal, as writers or other creatives, is to pursue our calling. Is that goal clearly expressed, is it SMART? Some might argue that it is not. They are wrong. If the point of the creative calling is to write, or paint, or play music, this goal couldn’t be SMARTer.

Aim: I will write.

Is it specific? Yes. It doesn’t matter what I write, as long as I write.

Is it measureable? Yes. Did I write today? Mission accomplished.

Is it agreed upon? Yes. My body tells me that I have to write – I have no choice in the matter.

Is it Realistic? Yes. Can I write? Just watch me.

Is it Time-based? Yes. Every day I have to write. The clock starts fresh with every sun-rise.

Where this aim becomes less SMART is when exterior factors and desires are introduced. Publishing a book next year. Organizing an art show. Releasing an album. These are second-order considerations resulting from the primary aim, which is only to undertake the creative activity itself. Even then, the aim can be tailored to accommodate these additional goals and in a broader sense, these activities are individual battles, campaigns in an unending war.

What then, of strategy? If pursuing a calling is the object, what is the plan to accomplish the aim? How can the principle be applied?

There are two methods, a macro and a micro.

The War

In the first case, the Principle can be applied to ensure that every action is in line with the goal of pursuing a calling. It might be expressed thus:

Aim: Pursue a calling as a writer.Strategy: Write.Tactics: Three main methods will be employed:Writing: Practice craft in a variety of styles, genres, and forms.Reading: Develop a knowledge base of similar (and non-similar) writing.Outreach: Develop a network of mentors, peers, and reviewers to enable feedback and support.Techniques:Writing: Take a course on characterization to improve on indirect (authorial interpretation or interpretation by another character) and direct methods (dialogue, action, appearance);Reading: Focus on classics to analyze story structure, as well as in genre to learn about conventions; Outreach: Join a writer’s group.

Every activity must be tested for its relation to the chosen aim; is it helping accomplish the goal? Does reading widely help in pursuing a calling as a writer? Assuming the definition entails treating said calling professionally (which it does), then yes, this activity helps. Likewise working on craft.

Combat – the Single Activity of the War

The micro application of the Master Principle of War is through the production of unique works, the battles mentioned above. In this case, the principle is analogous to theme. Each story must be about something; that something is the aim, or theme, of the story. Adapting Shawn Coyne’s wonderful analysis of Silence of the Lambs, this might be expressed as follows:

Aim: Tell a story about how justice prevails when people engage their inner darkness as passionately as their ‘positive’ side.Strategy: Write a thriller where the only way to catch a serial killer is to seek advice from another serial killer, trading favours about one’s inner secrets for information.Tactics: Apply genre conventions, to include:A crime / MacGuffin: Buffalo Bill’s desire to dress up like a woman.Clock: Buffalo Bill captures senator’s daughter.Red herrings: Raspail’s car clue.Speech in praise of the villain: Starling examines Buffalo Bill’s fileStakes become personal for the hero: Starling has to trade personal information to Lecter.Hero at the mercy of the villain: Clarice in Buffalo Bill’s basement.False ending: Buffalo Bill put down, but Lecter escapes.Techniques:POV: Free Indirect StylePOV continued: Primarily Starling, but others.Etc etc

Again, each activity should be tested for adherence to the aim, perhaps a more difficult task in this case, but important nonetheless. Shawn Coyne’s Story Grid should be consulted for more information.

In either case, the process remains the same: determine the aim, develop a strategy to accomplish the aim, then align tactics and techniques with the controlling object. The aim might change; that’s okay, at least in a micro sense. A story’s theme might not even become apparent until the storytelling process is well underway, but the effort can continue. When the theme does get revealed, it will be important to revisit the estimate. If there’s one thing contemporary conflicts have shown, it’s the importance of knowing and revisiting one’s purpose amidst a chaotic and complex operating environment.

Thankfully, Resistance is uncomplicated in this manner. Consequently, overcoming Resistance is equally uncomplicated – write, paint, play music, whatever constitutes the creative calling. Still, as uncomplicated as it may be, it is far from easy. Indeed, as Clausewitz wrote, ‘everything is very simple in War, but the simplest thing is difficult.’

What was the aim of Canada’s mission in Afghanistan? Consider:Canada sent forces to Afghanistan in late-2001 / early-2002 as part of Operation Enduring Freedom. The aim of the US-led mission was to dismantle the Al-Qaeda terrorist network in Afghanistan and remove the Taliban from power. When the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA) stood up in late-2002, the aim expanded to include assisting the Afghanistan transition to new leadership. Included in this mandate was the coordination of peace and reconciliation efforts, and also humanitarian assistance. From 2003 to 2004, the aim was to let the fledgling Afghan government develop its constitution and focus on its first elections, with the Canadian focus being on providing security around Kabul. In 2005, Canada’s aim changed to reflect the broader mandate of the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF). The mandate included not only assisting in the provision of security, but in governance and development as well. For Canada, these activates were realized in two primary ways, the conduct of combat operations and through a Provincial Reconstruction Team, both based in Kandahar province. In 2011, the aim remained on provision of security, development, and governance, but the execution changed from primarily combat operations to the training of Afghani national security forces. In 2014, Canada ceased its activities in Afghanistan.

What was the aim of Canada’s mission in Afghanistan? Consider:Canada sent forces to Afghanistan in late-2001 / early-2002 as part of Operation Enduring Freedom. The aim of the US-led mission was to dismantle the Al-Qaeda terrorist network in Afghanistan and remove the Taliban from power. When the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA) stood up in late-2002, the aim expanded to include assisting the Afghanistan transition to new leadership. Included in this mandate was the coordination of peace and reconciliation efforts, and also humanitarian assistance. From 2003 to 2004, the aim was to let the fledgling Afghan government develop its constitution and focus on its first elections, with the Canadian focus being on providing security around Kabul. In 2005, Canada’s aim changed to reflect the broader mandate of the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF). The mandate included not only assisting in the provision of security, but in governance and development as well. For Canada, these activates were realized in two primary ways, the conduct of combat operations and through a Provincial Reconstruction Team, both based in Kandahar province. In 2011, the aim remained on provision of security, development, and governance, but the execution changed from primarily combat operations to the training of Afghani national security forces. In 2014, Canada ceased its activities in Afghanistan. As of this writing, the Taliban is still an effective adversary in Afghanistan. Indeed, some reports suggest that 2016 may have been a banner year for the Taliban, with the force able to take back more territory than at any time since the 15-year campaign began.

So did Canada meet its aim Afghanistan?

The Objective

The overriding Principle of War is, ‘The Selection and Maintenance of the Aim.’ Whether in the conduct of war as a whole, or in the smallest supporting operation, it is essential to understand what the force is trying to achieve. Not only does this prevent a force from working at cross-purposes, it also ensures scarce resources are efficiently assigned to necessary activities.

Ideally, the aim should be clearly defined, simple, and direct. The acronym SMART applies: Specific, Measurable, Agreed Upon, Realistic, and Time-Based. (Note: there are multiple variations in the acronym – the version presented avoids A = attainable because of conceptual overlap with a goal being Realistic). Removing the Taliban from power is a specific and measurable goal. Assisting in the provision of security, development, and governance is not, or at least it’s much harder to express in terms of SMART criteria.

In theory, the aim cascades through the levels of conflict. The political level sets the overall objective, with the various instruments of national power – diplomatic, informational, military, economic – determining how best to achieve that goal. In turn, this unifying theme extends downward through the strategic, operational, and tactical levels to individual actors actually doing things on the battlefield; the so-called ‘strategic corporals.’

Some terminology:

The goal, or aim, or objective, is what defines a win; it’s what the force wants to happen. The goal can change as the situation evolves. Goals come with parameters, things that need to either happen, or not happen, like obeying laws.

Strategy is the general plan to accomplish a goal. It is executed through tactics, the how or actual activities that accomplish things. Strategy is constrained by the environment; a plan that works in one environment might not be appropriate in another. Lastly, tactics break up into individual techniques, the multitude of individual actions that can be taken as a result of minute to minute changes in the environment.

Goals and parameters dictate strategy.Strategy and environment dictate tactics.Tactics and the minute-to-minute situation dictate techniques.

At every level, there must be an appreciation for the overall aim and how the smallest technique supports the broader intent. Any deviation from rowing forward represents effort that’s at cross-purposes.

It is possible that the aim will change. This is natural and should not be a surprise. This is why the military’s analysis method, the estimate process, has a built-in check: ‘has the situation changed and is the mission still valid?’ That said, should a new aim be required, it should be similarly clear, simple, and direct; almost more so since it’s introducing change.

Using the Principle Against Resistance

The war with Resistance is for keeps. Make no mistake, as an internally generated expression of human self-sabotage, Resistance intuitively understands the nature of war and conflict far better than people consciously understand those same concepts. This includes the understanding that it must bend us to its will, it must compel us to do what it wants. That’s how it wins.

And what does Resistance want? To stop us from pursuing a creative calling.

Our goal, as writers or other creatives, is to pursue our calling. Is that goal clearly expressed, is it SMART? Some might argue that it is not. They are wrong. If the point of the creative calling is to write, or paint, or play music, this goal couldn’t be SMARTer.

Aim: I will write.

Is it specific? Yes. It doesn’t matter what I write, as long as I write.

Is it measureable? Yes. Did I write today? Mission accomplished.

Is it agreed upon? Yes. My body tells me that I have to write – I have no choice in the matter.

Is it Realistic? Yes. Can I write? Just watch me.

Is it Time-based? Yes. Every day I have to write. The clock starts fresh with every sun-rise.

Where this aim becomes less SMART is when exterior factors and desires are introduced. Publishing a book next year. Organizing an art show. Releasing an album. These are second-order considerations resulting from the primary aim, which is only to undertake the creative activity itself. Even then, the aim can be tailored to accommodate these additional goals and in a broader sense, these activities are individual battles, campaigns in an unending war.

What then, of strategy? If pursuing a calling is the object, what is the plan to accomplish the aim? How can the principle be applied?

There are two methods, a macro and a micro.

The War

In the first case, the Principle can be applied to ensure that every action is in line with the goal of pursuing a calling. It might be expressed thus:

Aim: Pursue a calling as a writer.Strategy: Write.Tactics: Three main methods will be employed:Writing: Practice craft in a variety of styles, genres, and forms.Reading: Develop a knowledge base of similar (and non-similar) writing.Outreach: Develop a network of mentors, peers, and reviewers to enable feedback and support.Techniques:Writing: Take a course on characterization to improve on indirect (authorial interpretation or interpretation by another character) and direct methods (dialogue, action, appearance);Reading: Focus on classics to analyze story structure, as well as in genre to learn about conventions; Outreach: Join a writer’s group.