Alastair Luft's Blog, page 2

December 18, 2016

Clausewitz and the War of Art: How the Principles of War Can Help Defeat Resistance

"You know you never defeated us on the battlefield," said the American colonel.

The North Vietnamese colonel pondered this remark a moment. "That may be so," he replied, "but it is also irrelevant."[1] How could the United States military have succeeded so well in Vietnam, yet still lost the war? This was the question Colonel Harry G. Summers sought to answer in his 1982 book, On Strategy: A Critical Analysis of the Vietnam War. His approach was straightforward; apply Clausewitzian theories to conduct a post-facto analysis. The results were impressive. Carl von Clausewitz To some, it may seem disappointing that On War continues to be the go-to source for theories on war and conflict. After all, almost 200 years have gone by since it was published and still, a sort of Godwin’s Law could be postulated for Clausewitz to the effect that the longer a discussion about military theory goes on, the greater the probability that one of the participants will bring up Clausewitz.

Carl von Clausewitz To some, it may seem disappointing that On War continues to be the go-to source for theories on war and conflict. After all, almost 200 years have gone by since it was published and still, a sort of Godwin’s Law could be postulated for Clausewitz to the effect that the longer a discussion about military theory goes on, the greater the probability that one of the participants will bring up Clausewitz.

There’s a good reason for this phenomenon, which is that Clausewitz’s ideas are still relevant.

Having just finished a series on applying the CAF principles of leadership to the business of writing, is it possible to apply other military theories in the interests of becoming better writers. Can the Principles of War be applied?

In short, yes. The Argument

Proposition One. Writers, like all artists, are at war. Each and every day, whether they know it or not, they take up the battle anew.

Proposition Two. The nature of war is immutable, although its character can change.

Proposition Three. It is possible to derive basic beliefs about the conduct of armed conflict. These ideas are called, ‘The Principles of War.’

Proposition Four. Given One and Two, it is possible to apply Three to the conduct of a writer’s war against the all-time enemy: Resistance.

Now, purists may argue that Clausewitz’s ideas and the Principles of War are generally considered applicable to armed, that is physical, conflict. And yet, the extension of the principles is not without precedent; witness the difficulties arising from trying to define cyber warfare. Similarly, understanding the operational environment requires getting beyond an understanding of the physical environment of air, land, and maritime, to include the information environment and human terrain. Clausewitz himself refers to the necessity of engaging beyond the physical domain by observing that disarming an enemy consists of targeting three objects, the military power, the country, and the enemy’s will. And when the enemy’s military power is composed primarily of non-munitions based weapons systems, such as fear, then so much greater the argument for war on the cognitive plane. Understanding The Nature of War and the Enemy

To win at war, practitioners need to understand its nature. This is, after all, the whole point of Clausewitzian theory. And Clausewitz provides many descriptors of the enduring parts of war. War is an act of violence pushed to its utmost bounds. The aim of war is to compel our opponents to fulfil our will. The result in war is never absolute. War is a serious means for a serious object.

There are others, all equally profound and at the same time offering grist for historians, strategists, and theorists to argue over. But the point here isn’t to dredge up these debates, but to assess how accurately they describe the war with Resistance. Let’s meet our enemy.

Target Information Package 01: Resistance

. J2 Briefer: Steven Pressfield.

Target Information Package 01: Resistance

. J2 Briefer: Steven Pressfield.

“Are you a writer who doesn’t write, a painter who doesn’t paint, an entrepreneur who never starts a venture? Then you know what Resistance is.”[2] - Steven Pressfield

Resistance is the universal force dedicated to stopping the soul’s call to realization. Although Resistance operates virtually entirely through non-munitions based targeting, it maintains an impressive list of lethal and non-lethal capabilities, and can weaponeer with the best of them. Fear, guilt, procrastination, self-medication, victimhood; these are but a view of the insidious weapon effects that Resistance can marshal to its cause. The High Payoff Target List (HPTL) for Resistance includes any creative endeavor, such as writing, painting, or music, but also includes other pursuits like education, beating addiction, or launching new ventures.

Does it make sense to look at war with Resistance through a Clausewitzian lens? Consider the enduring nature of war:

Q. Is war with Resistance an act of violence that knows no bounds?

A. Pressfield says yes. The more important our creative urge, the more powerfully Resistance will oppose it. (This is actually Clausewitz’s first reciprocal action, when one side uses an amount of force to impose its will, the other side will respond with an equal or greater use of force or risk defeat)

Q. Is the aim of war with Resistance to compel it to fulfill our will?

A. Pressfield says yes. Resistance has only one objective: stop us from doing our work. Our objective as creatives? Get the work done. Therefore, we must bend Resistance to our will.

Q. Is the result of war with Resistance ever absolute?

A. Pressfield says no. Resistance never sleeps, and although it can be temporarily kept at bay, the battle starts fresh every time the sun comes up.

Q. Is war with Resistance a serious means for a serious object?

A. Pressfield says you better believe it. Resistance’s ultimate target is our own Center of Gravity, our creative genius. Losing to Resistance will effectively turn us into shades of our potential selves. It seems clear, writers are at war with a ruthless adversary. Given the enduring nature of war, Clausewitzian concepts can be applied to describe this war with Resistance. So what about the Principles of War?

The Principles of War, or similar versions, have been around since at least Sun Tzu. Most of the big names have their variants, from Sun Tzu, to Miyamoto Musashi, Machiavelli, Jomini, Napoleon, and of course, Clausewitz.

Clausewitz is particularly notable since his ideas have generally formed the basis of Western military doctrine. In fact, the Soviet doctrine recognized many of the same principles, although their emphasis was placed on different aspects - a bit analogous to different martial arts systems placing greater or lesser emphasis on striking vs grappling.

In contemporary Western military doctrine, the Principles of War guide practitioners in the conduct of military actions. They’re not laws and they don’t need to be dogmatically followed. But, like so many things, practitioners are encouraged to understand them before deciding to disregard them. What’s more, the principles are inter-related. None of the principles in isolation will ensure victory. Instead, only through skillful integration and balancing can they contribute to success.

The Principles of War

In Canada, the Principles of War are: Selection and maintenance of the aim;Maintenance of morale;Offensive action;Security;Surprise;Concentration of force;Economy of effort;Flexibility;Cooperation; andAdministration. Over the next ten weeks, each of these principles will be analyze to determine how it can be applied in the war with Resistance.

Over the next ten weeks, each of these principles will be analyze to determine how it can be applied in the war with Resistance.

Colonel Summers’s conclusion in On Strategy was that the application of the principles of war had been critical to success in Vietnam, just not American success. As a result, his final point was an appeal to relearn the fundamental principles, to once more become brilliant at the basics as a prerequisite to mastering the profession of arms.

This entreaty should be equally compelling for writers because it plots a path to victory in the war with Resistance. Perhaps that’s why Steven Pressfield’s strategy for combatting Resistance is simply termed, Turning Pro, or in other words, becoming a professional. After all, one definition of professional is, ‘a person who engages in an activity with great competence.’[3]

So as professionals, it makes sense to use every resource available to us, including the Principles of War. [1] As cited in Harry G. Summers, On Strategy: A Critical Analysis of the Vietnam War, (New York: Presidio Press, 1982), 1.

[2] Steven Pressfield, The War of Art: Break Through the Blocks and Win Your Inner Creative Battles, (New York: Black Irish Entertainment LLC, 2002).

[3] "Professional,"Dictionary.com, accessed 18 December 2016, http://www.dictionary.com/browse/professional.

The North Vietnamese colonel pondered this remark a moment. "That may be so," he replied, "but it is also irrelevant."[1] How could the United States military have succeeded so well in Vietnam, yet still lost the war? This was the question Colonel Harry G. Summers sought to answer in his 1982 book, On Strategy: A Critical Analysis of the Vietnam War. His approach was straightforward; apply Clausewitzian theories to conduct a post-facto analysis. The results were impressive.

Carl von Clausewitz To some, it may seem disappointing that On War continues to be the go-to source for theories on war and conflict. After all, almost 200 years have gone by since it was published and still, a sort of Godwin’s Law could be postulated for Clausewitz to the effect that the longer a discussion about military theory goes on, the greater the probability that one of the participants will bring up Clausewitz.

Carl von Clausewitz To some, it may seem disappointing that On War continues to be the go-to source for theories on war and conflict. After all, almost 200 years have gone by since it was published and still, a sort of Godwin’s Law could be postulated for Clausewitz to the effect that the longer a discussion about military theory goes on, the greater the probability that one of the participants will bring up Clausewitz.There’s a good reason for this phenomenon, which is that Clausewitz’s ideas are still relevant.

Having just finished a series on applying the CAF principles of leadership to the business of writing, is it possible to apply other military theories in the interests of becoming better writers. Can the Principles of War be applied?

In short, yes. The Argument

Proposition One. Writers, like all artists, are at war. Each and every day, whether they know it or not, they take up the battle anew.

Proposition Two. The nature of war is immutable, although its character can change.

Proposition Three. It is possible to derive basic beliefs about the conduct of armed conflict. These ideas are called, ‘The Principles of War.’

Proposition Four. Given One and Two, it is possible to apply Three to the conduct of a writer’s war against the all-time enemy: Resistance.

Now, purists may argue that Clausewitz’s ideas and the Principles of War are generally considered applicable to armed, that is physical, conflict. And yet, the extension of the principles is not without precedent; witness the difficulties arising from trying to define cyber warfare. Similarly, understanding the operational environment requires getting beyond an understanding of the physical environment of air, land, and maritime, to include the information environment and human terrain. Clausewitz himself refers to the necessity of engaging beyond the physical domain by observing that disarming an enemy consists of targeting three objects, the military power, the country, and the enemy’s will. And when the enemy’s military power is composed primarily of non-munitions based weapons systems, such as fear, then so much greater the argument for war on the cognitive plane. Understanding The Nature of War and the Enemy

To win at war, practitioners need to understand its nature. This is, after all, the whole point of Clausewitzian theory. And Clausewitz provides many descriptors of the enduring parts of war. War is an act of violence pushed to its utmost bounds. The aim of war is to compel our opponents to fulfil our will. The result in war is never absolute. War is a serious means for a serious object.

There are others, all equally profound and at the same time offering grist for historians, strategists, and theorists to argue over. But the point here isn’t to dredge up these debates, but to assess how accurately they describe the war with Resistance. Let’s meet our enemy.

Target Information Package 01: Resistance

. J2 Briefer: Steven Pressfield.

Target Information Package 01: Resistance

. J2 Briefer: Steven Pressfield.“Are you a writer who doesn’t write, a painter who doesn’t paint, an entrepreneur who never starts a venture? Then you know what Resistance is.”[2] - Steven Pressfield

Resistance is the universal force dedicated to stopping the soul’s call to realization. Although Resistance operates virtually entirely through non-munitions based targeting, it maintains an impressive list of lethal and non-lethal capabilities, and can weaponeer with the best of them. Fear, guilt, procrastination, self-medication, victimhood; these are but a view of the insidious weapon effects that Resistance can marshal to its cause. The High Payoff Target List (HPTL) for Resistance includes any creative endeavor, such as writing, painting, or music, but also includes other pursuits like education, beating addiction, or launching new ventures.

Does it make sense to look at war with Resistance through a Clausewitzian lens? Consider the enduring nature of war:

Q. Is war with Resistance an act of violence that knows no bounds?

A. Pressfield says yes. The more important our creative urge, the more powerfully Resistance will oppose it. (This is actually Clausewitz’s first reciprocal action, when one side uses an amount of force to impose its will, the other side will respond with an equal or greater use of force or risk defeat)

Q. Is the aim of war with Resistance to compel it to fulfill our will?

A. Pressfield says yes. Resistance has only one objective: stop us from doing our work. Our objective as creatives? Get the work done. Therefore, we must bend Resistance to our will.

Q. Is the result of war with Resistance ever absolute?

A. Pressfield says no. Resistance never sleeps, and although it can be temporarily kept at bay, the battle starts fresh every time the sun comes up.

Q. Is war with Resistance a serious means for a serious object?

A. Pressfield says you better believe it. Resistance’s ultimate target is our own Center of Gravity, our creative genius. Losing to Resistance will effectively turn us into shades of our potential selves. It seems clear, writers are at war with a ruthless adversary. Given the enduring nature of war, Clausewitzian concepts can be applied to describe this war with Resistance. So what about the Principles of War?

The Principles of War, or similar versions, have been around since at least Sun Tzu. Most of the big names have their variants, from Sun Tzu, to Miyamoto Musashi, Machiavelli, Jomini, Napoleon, and of course, Clausewitz.

Clausewitz is particularly notable since his ideas have generally formed the basis of Western military doctrine. In fact, the Soviet doctrine recognized many of the same principles, although their emphasis was placed on different aspects - a bit analogous to different martial arts systems placing greater or lesser emphasis on striking vs grappling.

In contemporary Western military doctrine, the Principles of War guide practitioners in the conduct of military actions. They’re not laws and they don’t need to be dogmatically followed. But, like so many things, practitioners are encouraged to understand them before deciding to disregard them. What’s more, the principles are inter-related. None of the principles in isolation will ensure victory. Instead, only through skillful integration and balancing can they contribute to success.

The Principles of War

In Canada, the Principles of War are: Selection and maintenance of the aim;Maintenance of morale;Offensive action;Security;Surprise;Concentration of force;Economy of effort;Flexibility;Cooperation; andAdministration.

Over the next ten weeks, each of these principles will be analyze to determine how it can be applied in the war with Resistance.

Over the next ten weeks, each of these principles will be analyze to determine how it can be applied in the war with Resistance.Colonel Summers’s conclusion in On Strategy was that the application of the principles of war had been critical to success in Vietnam, just not American success. As a result, his final point was an appeal to relearn the fundamental principles, to once more become brilliant at the basics as a prerequisite to mastering the profession of arms.

This entreaty should be equally compelling for writers because it plots a path to victory in the war with Resistance. Perhaps that’s why Steven Pressfield’s strategy for combatting Resistance is simply termed, Turning Pro, or in other words, becoming a professional. After all, one definition of professional is, ‘a person who engages in an activity with great competence.’[3]

So as professionals, it makes sense to use every resource available to us, including the Principles of War. [1] As cited in Harry G. Summers, On Strategy: A Critical Analysis of the Vietnam War, (New York: Presidio Press, 1982), 1.

[2] Steven Pressfield, The War of Art: Break Through the Blocks and Win Your Inner Creative Battles, (New York: Black Irish Entertainment LLC, 2002).

[3] "Professional,"Dictionary.com, accessed 18 December 2016, http://www.dictionary.com/browse/professional.

Published on December 18, 2016 10:54

December 15, 2016

AUthor Interview: Janna Grace

For those with questions on crowdfunding and the Inkshares platform, Inkshares author Donna Fung has started a new series called Coming Clean on Crowdfunding that looks into both of those topics. This first interview is with Janna Grace, author of

The Talkers are Talking

. Check out the interview below!

Published on December 15, 2016 16:34

December 11, 2016

The Importance of Fighting Spirit

There are many high standards in the military, which is a good thing. After all, entrusting an institution with the use of violence on behalf of society is an impressive responsibility. As necessary as these standards are, it can be difficult to meet them all the time. Over the course of my career, as ashamed as I am to admit it, I’ve periodically taken the easy way out.

There are many high standards in the military, which is a good thing. After all, entrusting an institution with the use of violence on behalf of society is an impressive responsibility. As necessary as these standards are, it can be difficult to meet them all the time. Over the course of my career, as ashamed as I am to admit it, I’ve periodically taken the easy way out.On one night navigation exercise, with three legs left, untold kilometers to go, and only about ten minutes to do so, it seemed pretty obvious to me that I wasn’t going to make it. Instead of bashing through a dark swamp for the remaining time, I sat down, had a big dip of Skoal, then trudged back to the admin area. So what, right? It was only 10 minutes or so and it wasn’t a test, only a practice run.

Except it matters.

It matters because it didn’t embody the values of fighting spirit and the will to win, values that compose the ethos of the Canadian military. So while I’m virtually certain I wouldn’t have made the navigation points if I’d kept going, that’s not what matters.

What matters is that there’s a difference between giving up and failing. And in that particular situation, I chose poorly. Luckily, I got another chance, which led me to reflect on this week’s leadership principle. Exemplify and Reinforce the Military Ethos; Maintain Order and Discipline; Uphold Professional Norms

This principle is kind of three distinct ideas woven into one, so it’s tempting to believe that in true military fashion this is really a catch-all tenet, or something that picks up the loose ends not covered in the other principles. At least it’s consistent though, as the predecessor principle appears to have been the previous catch-all, ‘Lead by Example,’ which pretty much covers everything. For all that, Lead by Example continues to be one of my favorite leadership principles of all time.

Diving into the component parts of current principle, upholding professional norms refers to living up to the standards of the profession, which has both behavioral and performance aspects, such as acting in a certain way or meeting qualifications. Maintaining order and discipline is, I think, broadly self-explanatory. Lastly, exemplifying the military ethos refers to embodying the spirit of a community, in this case, a military one.

These component parts can be applied to writing in a variety of ways. For example, standards of style and format apply to different types of professional writing. While what’s expected from a journalist is different from a copy writer, and different again from technical writing or creative fiction, there are some unifying themes, such as expressing ideas with clarity, in an organized manner, and with a high level of grammar and language. Yes, this could differ wildly between applications. Writing for a technical journal is far different than blogging, but the standards are applied regardless.

In the interest of time and space, I won’t discuss applicability of maintaining good order and discipline as I want to focus on the idea of ethos. According to Leading People, ethos is the, ‘essential character, identity, and guiding motivational spirit of an institution, desired by its members in pursuit of institutional goals.’ An ethos is particular to a certain set of conditions, based largely on the role of the institution - the ethos expresses the values, beliefs, and expectations that are believed to be necessary to accomplish the institutional mission.

This is easy to see in some of the CAF’s expressed values, beliefs, and expectations about military service (which aren’t really all that different from comparison militaries). Unlimited liability, fighting spirit, courage, and teamwork; these all articulate beliefs consistent with an expectation of what it takes to succeed in the profession of arms. Then again, tracking causality is easy in this case as the role of the military in society is generally well accepted.

What’s the role of the writer in society?

What’s the role of the writer in society?Unlike the military, does it even make sense to talk about writers as a group? E.B. White appears to have been against this idea. In The Duty of Writers , he suggested that the quality of writing didn’t do well when writers formed groups and instead, benefitted when writers held adversarial relationships. What’s more, he also questioned the possibility of a collaborative goal for writers in general except to write about whatever they want, or, “…it is the duty of writers to pay no attention to duty.’

In another essay, E.B. White expands on this idea by proposing the role of a writer as a custodian. More articulately, a writer is, ‘…charged with the safekeeping of all unexpected items of worldly or unworldly enchantment, as though I might be held personally responsible if even a small one were to be lost.”

Nicholas Conley expands on this idea by saying that writers are people who’ve accepted the responsibility to document the, ‘…time, place and character of whatever era they live in.’ This could manifest in different ways, and Conley suggests that different genres correspond to reflections of different facets of society at a particular time. So yes, even the authors writing cat mysteries (there is such a genre) are contributing to something much bigger than cats solving cold cases. the preservation of society. Pretty heady stuff.

So what ethos can be developed that helps a writer live up to this responsibility?

I think the most important thing here is to pick something. E.B. White suggested, ‘be good, not lousy; true, not false; lively, not dull; accurate not full of error.”

Or, seek inspiration in Steven Pressfield’s rules for professionals:

Show up every day;Show up no matter what;Stay on the job all day;Commit to the long haul;Accept that the stakes are high and real;Accept remuneration for labour;Do not over-identify with you job;Master the techniques of your job;Have a sense of humour about your job; andReceive praise or blame in the real world.

There are so many great resources here, again, I think the important thing is to pick something that you can live up to, which brings us to the last point.

Align Your Actions With Your Ethos

Align Your Actions With Your EthosThis is what is meant by leading by example, picking an ethos to embody and then owning it from then on out. As heretical as it probably is for a writer to say this, but actions can sometimes speak louder than words and this is one of those times where showing is much more powerful than telling. Of course, the path will be difficult to hold to sometimes, but just keep coming back to it.

I remember my basic pilot training and being told to hold steady at a certain altitude and heading. I found it very difficult to hold the plane perfectly steady as conditions are always changing, but as long as I stayed on top of what was going on and made the appropriate course corrections, I was always able to bring it back. The same thing applies here.

Alternatively, being off the path might seem more like being in the literary equivalent of lost in a swamp, tired and soaking wet. Even then, every day starts afresh. So take a Marlboro Moment, reshoot the bearing, and keep trying. Better to fail attempting great things than attempt nothing and succeed.

Published on December 11, 2016 10:01

December 4, 2016

On Edumacation

Yogi Berra reportedly said that, ‘you can observe a lot just by watching.’

Yogi Berra reportedly said that, ‘you can observe a lot just by watching.’ Sounds similar to the After-Action Review (AAR) process, a tool of organizational learning that is indeed based on observing a lot. Briefly, the AAR process begins by compiling observations about an event or action. When the event is done, these observations are discussed by those involved to determine what happened, why it happened, and how it could be done better in the future. For those things identified as needing improvement, the observations (and recommendations) get fed to commanders who direct change. When the change has been implemented, the organization has learned its lesson. Tea and medals all around!

Hooray! In theory, the system is great and when done well, it’s extremely effective.

Hooray! In theory, the system is great and when done well, it’s extremely effective.But Yogi Berra also reportedly said that, ‘In theory, there is no difference between theory and practice. But in practice, there is.’ This is one of those times. In practice, many observations get compiled into matrixes that go into databases where they are promptly forgotten. This conundrum worsens due to personnel turnover. By some accounts, approximately a third of CAF military personnel change positions each year and the transaction costs often include incomplete IM passage. On the procedural side, a commander may not implement a change, sometimes for good reasons like the juice not being worth the squeeze. Other reasons could include wanting to leave the decision to their successor because they only have a few months left, or conversely, not wanting to do anything rash because they just took over.

Still, as this week’s principle illustrates, at least the military knows that learning is important and as they say, knowing is half the battle.

In case you doubted that 'they' say this... Learn From Experience and Those Who Have Experience

In case you doubted that 'they' say this... Learn From Experience and Those Who Have ExperienceI think this principle evolved from, ‘Appreciate Your Strengths and Limitations, and Pursue Self-Improvement.’ Then again, pursuing self-improvement was the first principle in the revised set, so maybe not. Still, since none of the earlier principles address the concept of learning from experience, it has to be an improvement, right?

Although it probably seems like applying this principle to the business of writing would be easy (Want to get better as a writer? Try learning from your experiences...aaaah), it’s worth digging a little deeper into the concepts.

Deliberate learning from experience implies the conduct of an objective analysis, or receiving that analysis from others. For the former, time must be set aside for reflection, something easier said than done. Also, to be worth the effort an honest attempt to identify things that can improve has to be made as opposed to going through the process for appearances. The latter entails being open to constructive criticism, something much easier said than done. Even in the military - which sometimes parrots the necessity of having thick skin - we often sanitize our criticism to avoid hurt feelings. It’s done with the best of intentions, but in the long run, it does no favours.

The lesson on the flip side is to practice how to give criticism. There are some very easy to implement guidelines for doing this well, such as not framing the critique as a personal attack. There are other guidelines too, some of which may or may not work for writing. Although writing is craft, which can be improved, it's also an art form - no two people will read a book and have the exact same impression of it. A great quote by Mr. Neil Gaiman is to, “Remember: when people tell you something’s wrong or doesn’t work for them, they are almost always right. When they tell you exactly what they think is wrong and how to fix it, they are almost always wrong.”

So how to go about getting useful critique in order to learn? As with many things, the military has a five step process.

Prepare. This stage involves setting the parameters of the investigation, which brings clarity to collection efforts. What are you trying to learn about? What questions need to be asked to learn about that issue and what data needs to be collected to provide the answers? For that matter, how will observations be collected? Unsolicited feedback? Observations from the comments sections of online articles? Beta readers? All great questions to think about.

One of the more practical pieces of advice I read in this area is to develop a questionnaire for beta readers, particularly for early drafts. Give them the five or six major areas to focus on and tell them to ignore grammar / punctuation etc.. What's more, choose your beta readers carefully, people who are ideally in the target audience for the book, are regular readers, and will not eviscerate you with their comments.

Click for more info on Beta readers Collect. This is the gathering of data in line (ideally) with whatever plan was identified in the preparation stage. Maybe this is getting feedback from beta readers or editors, maybe it’s working with a script doctor, or maybe it’s posting chapters on Wattpad for comment. Either way, feedback is going to be coming in and the challenge will be to keep an open mind. This is definitely where an effort is made to reach out to those with experience, but keep in mind that nobody has the experience of telling your exact story. Story telling in general and in similar genres, yes, but in the end the story is uniquely your own.

Click for more info on Beta readers Collect. This is the gathering of data in line (ideally) with whatever plan was identified in the preparation stage. Maybe this is getting feedback from beta readers or editors, maybe it’s working with a script doctor, or maybe it’s posting chapters on Wattpad for comment. Either way, feedback is going to be coming in and the challenge will be to keep an open mind. This is definitely where an effort is made to reach out to those with experience, but keep in mind that nobody has the experience of telling your exact story. Story telling in general and in similar genres, yes, but in the end the story is uniquely your own.The collection stage should also involve some rough analysis and filtering, such as grouping observations with common themes or topics. In this way, it's possible to determine if obserations are stand-alone topics or possibly indicate trends. Is the illogical conversation that takes place on page 14 a quick fix to clean up, or is it symptomatic of needing to improve dialogue in general? Preliminary filtering may also help weed out irrelevant feedback like, "I thought it was good," which, while good for the ego, contributes little to use in improvement - and everything can improve a bit.

Analyze. The aim of this stage is to identify what’s working, what needs to change, and identify viable ways to affect that change. To come back to Mr. Gaiman’s quote, not every suggestion is going to be helpful in improving the story, so this is where those judgements are made.

Commit. I adapted this step somewhat as the original is designed for a commander who’s deciding on recommendations from their staff. Some recommendations might get implemented, but invariably some don’t. Ultimately, this is about making a conscious decision and owning the areas where change is needed. Commitment is really the only way, nobody else is as invested in your self-improvement as you are.

Implement the Change. A lesson isn’t learned until a behavior has been changed, so the final step of the process is to take action. If it’s a manuscript in development, then make the appropriate amendments. Or find a mentor to work on systemic issues that have routinely come up. Whatever the action is, put it in place. And don’t forget to periodically check your progress.

Alternatively, don’t do any of these things. Put those observations in a drawer that you plan on never opening and get back to work - there are important things to accomplish! Just remember, even as there’s a good reason behind the saying that the definition of insanity is doing the same thing repeatedly and expecting a different result, there’s also a good reason behind the saying that generals always prepare for the last war.

I'm sure none of these books include blunders based on failing to learn from experience...

I'm sure none of these books include blunders based on failing to learn from experience...  In other words, if the whole working smarter thing isn’t working out, just work harder. But keep in mind one last quote from Yogi Berra, ‘losing is a learning experience. It teaches you humility. It teaches you to work harder. It’s also a powerful motivator.”

In other words, if the whole working smarter thing isn’t working out, just work harder. But keep in mind one last quote from Yogi Berra, ‘losing is a learning experience. It teaches you humility. It teaches you to work harder. It’s also a powerful motivator.”

Published on December 04, 2016 10:32

November 27, 2016

4 Steps to Maintaining Situational Awareness

I began my Patrol Pathfinder Course in September of 2002, having just returned from a six month deployment to Afghanistan. Three months later and 20 pounds lighter (incidentally 20 pounds more than I lost in Afghanistan), I’d passed.

Still, while I may have received my torch, it wasn’t exactly covered in glory.

On one particular patrol, we’d just finished up a dusk assault and were back in the Objective Rendezvous (ORV) waiting to exfiltrate the area. I was the navigator and I while I was plotting my exit route, one of the instructors leaned over and said we had to get out of the bush ASAP. It must have really been urgent, because the instructor also said I could use light to navigate.

On one particular patrol, we’d just finished up a dusk assault and were back in the Objective Rendezvous (ORV) waiting to exfiltrate the area. I was the navigator and I while I was plotting my exit route, one of the instructors leaned over and said we had to get out of the bush ASAP. It must have really been urgent, because the instructor also said I could use light to navigate.

That was a pretty big deal because we normally had to bash around in the bush in the dark, so before the instructor could change his mind, I fired up my headlamp with its red tactical filter, took my bearing by putting ‘red-in-the-bed’, and stepped off. Behind me, eleven other tired men hoisted their hundred-pound rucksacks and trudged along.

Guess what red-in-the-bed looks like through a red-filtered light? To make a long story short, after about 15 minutes of bumbling along, the instructor stopped me, shone a white light onto my compass and told me to stop heading on the back-bearing (at least that was the gist – it was more colourful, trust me). Because I’d been excited to get out of the bush, I’d lost track of my surroundings and ended up dragging a tired platoon almost a kilometre in the wrong direction. Turns out, ‘red-in-the-bed’ looks the same for both directions under a red filter; who knew?

Guess what red-in-the-bed looks like through a red-filtered light? To make a long story short, after about 15 minutes of bumbling along, the instructor stopped me, shone a white light onto my compass and told me to stop heading on the back-bearing (at least that was the gist – it was more colourful, trust me). Because I’d been excited to get out of the bush, I’d lost track of my surroundings and ended up dragging a tired platoon almost a kilometre in the wrong direction. Turns out, ‘red-in-the-bed’ looks the same for both directions under a red filter; who knew?

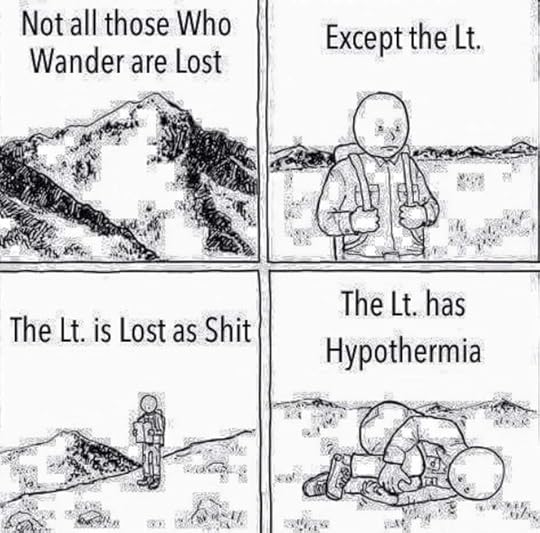

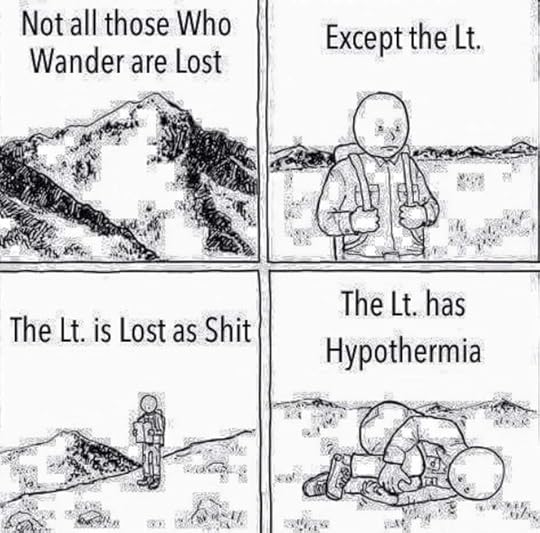

At least I didn't get hypothermia - only cellulitis! Which introduces the CAF leadership principle for this week,

At least I didn't get hypothermia - only cellulitis! Which introduces the CAF leadership principle for this week,

Maintain Situational Awareness; Seek Information; Keep Current

Try as I might, I actually couldn’t find a good equivalent to this principle in the previous versions. Although one could argue that this principle is implied within ‘Keep Your Subordinates Informed,’ I’m not sure how somebody can do that without being informed themselves. Needless to say, I think there’s merit in a principle that exhorts a person to keep current.

So what exactly is entailed by maintaining situational awareness?

For starters, situational awareness refers to being aware of what’s going on around you. Especially in dynamic and complex environments, situational awareness is crucial as a mechanism to perform effectively. In effect, a person will find it difficult to make appropriate decisions if they don’t understand what’s going on around them. Of course, your environment is constantly changing, so to maintain awareness, it’s necessary to seek feedback – or information – in order to keep one’s perspective current.

Pretty straightforward, right?

Now for the tricky part, which is how to apply this principle to the business of writing. Luckily, the military has a four step process for maintaining situational awareness that can easily be adapted.

Define The Environment

The aim of this principle is ultimately to understand one’s environment – not what’s going on in the environment, only what the environment actually is. To do that, one must first define what specific environment is being understood. What does it include?

In our running example, readers are within the environment, but so are other writers. More broadly, the publishing industry is part of the environment as well, as are developments in online marketing or other services.

All of these things could impact decisions a writer must make, such as whether to self-publish, go with traditional publishing, or try something new, like crowdfunded publishing. To best understand the roles that these things have on decision making, a writer must first define them as constituting the environment.

Seek Information

Once the environment has been defined, a writer needs to determine how they’re going to seek out the information they need to stay current. If readership is the environmental component, then the question is how to interact with readers. A practical outcome in this case includes decisions such as how an author sets up their author platform. Does the platform solicit feedback? Does it have a blog? Is it just another soapbox from which to sell things? All of these examples could be termed passive information collection, since it relies on readers coming to the writer.

Building author platforms is an emerging cottage industry On the flip side, an author platform probably won’t help an author stay abreast of other aspects of the defined environment, such as developments in the publishing industry. As opposed to passive collection, this type of information has to be actively sought out, which means active engagement. Decisions that might be influenced for a writer here include participation in writing groups, conferences, or other forms of direct engagement.

Building author platforms is an emerging cottage industry On the flip side, an author platform probably won’t help an author stay abreast of other aspects of the defined environment, such as developments in the publishing industry. As opposed to passive collection, this type of information has to be actively sought out, which means active engagement. Decisions that might be influenced for a writer here include participation in writing groups, conferences, or other forms of direct engagement.

Process the Information

This is taking the principle to the next level (it only speaks about maintaining situational awareness, not doing anything with that information), but to me, this includes analyzing the information to gain some sort of an understanding. Ultimately, once the information has been gathered, the next step is thinking about what it means.

Some of the questions to consider could include questioning the information itself. Are there themes? Is it accurate? Trends probably can’t be established from single source information, so should ideally be corroborated.

More practically, what does the information mean for outreach activities? Are they collecting the required information? Should alternatives be introduced? Should the weighting be more geared for maximum social media participation, or only a few platforms? What about e-mail lists? And most important of all; what does this mean for the individual writer and their unique goals and personality? This are a few of the possible things to think through, but I’m sure there many more.

Take Action

Once the information has been considered, do something. Drop Instagram to go for Twitter. Offer free material as an incentive to join a mailing list.

Or do nothing, that’s a legitimate choice, as long as it’s a conscious decision to do nothing as opposed to doing nothing through indecision – there’s a difference. And don’t stress, the individual actions or decisions don’t need to be earth shattering. Some of these environmental aspects are slow movers with long time horizons, so it could take years to decades for trends to emerge and processes to change. Maybe the only decision to make is to keep observing and refining the perspective. Then again, if its technology related, things could change quickly. In either case, make a choice, then own it.

In an ideal world, if you’ve been objective about what matters to you and implemented effective mechanisms to collect and analyze information, you should be able to maintain a good overview of what's going on in the surrounding environment. That will at least provide the framework for steering a general course toward whatever goal you’re trying to reach, although it's still no guarantee. Even if that's the case, take heart in the observation that sometimes the best lessons are learned after heading in the wrong direction for a while.

Still, while I may have received my torch, it wasn’t exactly covered in glory.

On one particular patrol, we’d just finished up a dusk assault and were back in the Objective Rendezvous (ORV) waiting to exfiltrate the area. I was the navigator and I while I was plotting my exit route, one of the instructors leaned over and said we had to get out of the bush ASAP. It must have really been urgent, because the instructor also said I could use light to navigate.

On one particular patrol, we’d just finished up a dusk assault and were back in the Objective Rendezvous (ORV) waiting to exfiltrate the area. I was the navigator and I while I was plotting my exit route, one of the instructors leaned over and said we had to get out of the bush ASAP. It must have really been urgent, because the instructor also said I could use light to navigate.That was a pretty big deal because we normally had to bash around in the bush in the dark, so before the instructor could change his mind, I fired up my headlamp with its red tactical filter, took my bearing by putting ‘red-in-the-bed’, and stepped off. Behind me, eleven other tired men hoisted their hundred-pound rucksacks and trudged along.

Guess what red-in-the-bed looks like through a red-filtered light? To make a long story short, after about 15 minutes of bumbling along, the instructor stopped me, shone a white light onto my compass and told me to stop heading on the back-bearing (at least that was the gist – it was more colourful, trust me). Because I’d been excited to get out of the bush, I’d lost track of my surroundings and ended up dragging a tired platoon almost a kilometre in the wrong direction. Turns out, ‘red-in-the-bed’ looks the same for both directions under a red filter; who knew?

Guess what red-in-the-bed looks like through a red-filtered light? To make a long story short, after about 15 minutes of bumbling along, the instructor stopped me, shone a white light onto my compass and told me to stop heading on the back-bearing (at least that was the gist – it was more colourful, trust me). Because I’d been excited to get out of the bush, I’d lost track of my surroundings and ended up dragging a tired platoon almost a kilometre in the wrong direction. Turns out, ‘red-in-the-bed’ looks the same for both directions under a red filter; who knew?  At least I didn't get hypothermia - only cellulitis! Which introduces the CAF leadership principle for this week,

At least I didn't get hypothermia - only cellulitis! Which introduces the CAF leadership principle for this week,Maintain Situational Awareness; Seek Information; Keep Current

Try as I might, I actually couldn’t find a good equivalent to this principle in the previous versions. Although one could argue that this principle is implied within ‘Keep Your Subordinates Informed,’ I’m not sure how somebody can do that without being informed themselves. Needless to say, I think there’s merit in a principle that exhorts a person to keep current.

So what exactly is entailed by maintaining situational awareness?

For starters, situational awareness refers to being aware of what’s going on around you. Especially in dynamic and complex environments, situational awareness is crucial as a mechanism to perform effectively. In effect, a person will find it difficult to make appropriate decisions if they don’t understand what’s going on around them. Of course, your environment is constantly changing, so to maintain awareness, it’s necessary to seek feedback – or information – in order to keep one’s perspective current.

Pretty straightforward, right?

Now for the tricky part, which is how to apply this principle to the business of writing. Luckily, the military has a four step process for maintaining situational awareness that can easily be adapted.

Define The Environment

The aim of this principle is ultimately to understand one’s environment – not what’s going on in the environment, only what the environment actually is. To do that, one must first define what specific environment is being understood. What does it include?

In our running example, readers are within the environment, but so are other writers. More broadly, the publishing industry is part of the environment as well, as are developments in online marketing or other services.

All of these things could impact decisions a writer must make, such as whether to self-publish, go with traditional publishing, or try something new, like crowdfunded publishing. To best understand the roles that these things have on decision making, a writer must first define them as constituting the environment.

Seek Information

Once the environment has been defined, a writer needs to determine how they’re going to seek out the information they need to stay current. If readership is the environmental component, then the question is how to interact with readers. A practical outcome in this case includes decisions such as how an author sets up their author platform. Does the platform solicit feedback? Does it have a blog? Is it just another soapbox from which to sell things? All of these examples could be termed passive information collection, since it relies on readers coming to the writer.

Building author platforms is an emerging cottage industry On the flip side, an author platform probably won’t help an author stay abreast of other aspects of the defined environment, such as developments in the publishing industry. As opposed to passive collection, this type of information has to be actively sought out, which means active engagement. Decisions that might be influenced for a writer here include participation in writing groups, conferences, or other forms of direct engagement.

Building author platforms is an emerging cottage industry On the flip side, an author platform probably won’t help an author stay abreast of other aspects of the defined environment, such as developments in the publishing industry. As opposed to passive collection, this type of information has to be actively sought out, which means active engagement. Decisions that might be influenced for a writer here include participation in writing groups, conferences, or other forms of direct engagement.Process the Information

This is taking the principle to the next level (it only speaks about maintaining situational awareness, not doing anything with that information), but to me, this includes analyzing the information to gain some sort of an understanding. Ultimately, once the information has been gathered, the next step is thinking about what it means.

Some of the questions to consider could include questioning the information itself. Are there themes? Is it accurate? Trends probably can’t be established from single source information, so should ideally be corroborated.

More practically, what does the information mean for outreach activities? Are they collecting the required information? Should alternatives be introduced? Should the weighting be more geared for maximum social media participation, or only a few platforms? What about e-mail lists? And most important of all; what does this mean for the individual writer and their unique goals and personality? This are a few of the possible things to think through, but I’m sure there many more.

Take Action

Once the information has been considered, do something. Drop Instagram to go for Twitter. Offer free material as an incentive to join a mailing list.

Or do nothing, that’s a legitimate choice, as long as it’s a conscious decision to do nothing as opposed to doing nothing through indecision – there’s a difference. And don’t stress, the individual actions or decisions don’t need to be earth shattering. Some of these environmental aspects are slow movers with long time horizons, so it could take years to decades for trends to emerge and processes to change. Maybe the only decision to make is to keep observing and refining the perspective. Then again, if its technology related, things could change quickly. In either case, make a choice, then own it.

In an ideal world, if you’ve been objective about what matters to you and implemented effective mechanisms to collect and analyze information, you should be able to maintain a good overview of what's going on in the surrounding environment. That will at least provide the framework for steering a general course toward whatever goal you’re trying to reach, although it's still no guarantee. Even if that's the case, take heart in the observation that sometimes the best lessons are learned after heading in the wrong direction for a while.

Published on November 27, 2016 10:23