Jeff Atwood's Blog, page 5

April 30, 2015

What is Trolling?

If you engage in discussion on the Internet long enough, you're bound to encounter it: someone calling someone else a troll.

The common interpretation of Troll is the Grimms' Fairy Tales, Lord of the Rings, "hangs out under a bridge" type of troll.

Thus, a troll is someone who exists to hurt people, cause harm, and break a bunch of stuff because that's something brutish trolls just … do, isn't it?

In that sense, calling someone a Troll is not so different from the pre-Internet tactic of calling someone a monster – implying that they lack all the self-control and self-awareness a normal human being would have.

Pretty harsh.

That might be what the term is evolving to mean, but it's not the original intent.

The original definition of troll was not a beast, but a fisherman:

Troll

verb \ˈtrōl\

to fish with a hook and line that you pull through the water

to search for or try to get (something)

to search through (something)

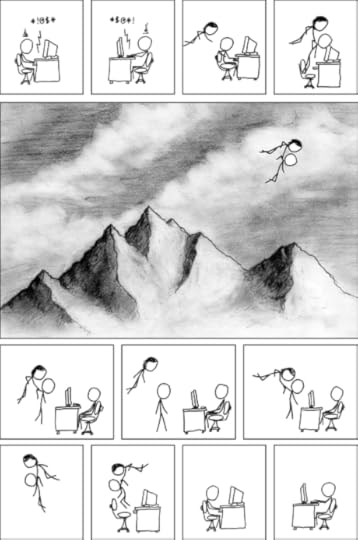

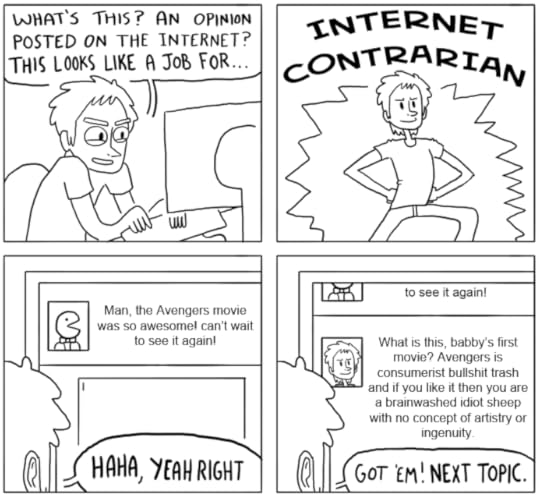

If you're curious why the fishing metaphor is so apt, check out this interview:

There's so much fishing going on here someone should have probably applied for a permit first.

He engages in the interview just enough to get the other person to argue with them. From there, he fishes for anything that can nudge the argument into some kind of car wreck that everyone can gawk at, generating lots of views and publicity.

He isn't interested in learning anything about the movie, or getting any insight, however fleeting, into this celebrity and how they approached acting or directing. Those are perfunctory concerns, quickly discarded on the way to their true goal: generating controversy, the more the better.

I almost feel sorry for Quentin Tarantino, who is so obviously passionate about what he does, because this guy is a classic troll.

He came to generate argument.

He doesn't truly care about the topic.

Some trolls can seem to care about a topic, because they hold extreme views on it, and will hold forth at great length on said topic, in excruciating detail, to anyone who will listen. For days. Weeks. Months. But this is an illusion.

The most striking characteristic of the worst trolls is that their position on a given topic is absolutely written in stone, immutable, and they will defend said position to the death in the face of any criticism, evidence, or reason.

Look. I'm not new to the Internet. I know nobody has ever convinced anybody to change their mind about anything through mere online discussion before. It's unpossible.

But I love discussion. And in any discussion that has a purpose other than gladiatorial opinion bloodsport, the most telling question you can ask of anyone is this:

Why are you here?

Did you join this discussion to learn? To listen? To understand other perspectives? Or are you here to berate us and recite your talking points over and over? Are you more interested in fighting over who is right than actually communicating?

If you really care about a topic, you should want to learn as much as you can about it, to understand its boundaries, and the endless perspectives and details that make up any interesting topic. Heck, I don't even want anyone to change your mind. But you do have to demonstrate to us that you are, at minimum, at least somewhat willing to entertain other people's perspectives, and potentially evolve your position on the topic to a more nuanced, complex one over time.

In other words, are you here in good faith?

People whose actions demonstrate that they are participating in bad faith – whether they are on the "right" side of the debate or not – need to be shown the door.

So now you know how to identify a troll, at least by the classic definition. But how do you handle a troll?

You walk away.

I'm afraid I don't have anything uniquely insightful to offer over that old chestnut, "Don't feed the trolls." Responding to a troll just gives them evidence of their success for others to enjoy, and powerful incentive to try it again to get a rise out of the next sucker and satiate their perverse desire for opinion bloodsport. Someone has to break the chain.

I'm all for giving people the benefit of the doubt. Just because someone has a controversial opinion, or seems kind of argumentative (guilty, by the way), doesn't automatically make them a troll. But their actions over time might.

(I also recognize that in matters of social justice, there is sometimes value in speaking out and speaking up, versus walking away.)

So the next time you encounter someone who can't stop arguing, who seems unable to generate anything other than heat and friction, whose actions amply demonstrate that they are no longer participating in the conversation in good faith … just walk away. Don't take the bait.

Even if sometimes, that troll is you.

[advertisement] How are you showing off your awesome? Create a Stack Overflow Careers profile and show off all of your hard work from Stack Overflow, Github, and virtually every other coding site. Who knows, you might even get recruited for a great new position!

April 23, 2015

Your Password is Too Damn Short

I'm a little tired of writing about passwords. But like taxes, email, and pinkeye, they're not going away any time soon. Here's what I know to be true, and backed up by plenty of empirical data:

No matter what you tell them, users will always choose simple passwords.

No matter what you tell them, users will re-use the same password over and over on multiple devices, apps, and websites. If you are lucky they might use a couple passwords instead of the same one.

What can we do about this as developers?

Stop requiring passwords altogether, and let people log in with Google, Facebook, Twitter, Yahoo, or any other valid form of Internet driver's license that you're comfortable supporting. The best password is one you don't have to store.

Urge browsers to support automatic, built-in password generation and management. Ideally supported by the OS as well, but this requires cloud storage and everyone on the same page, and that seems most likely to me per-browser. Chrome, at least, is moving in this direction.

Nag users at the time of signup when they enter passwords that are …

Too short: UY7dFd

Lack sufficient entropy: aaaaaaaaa

Match common dictionary words: anteaters1

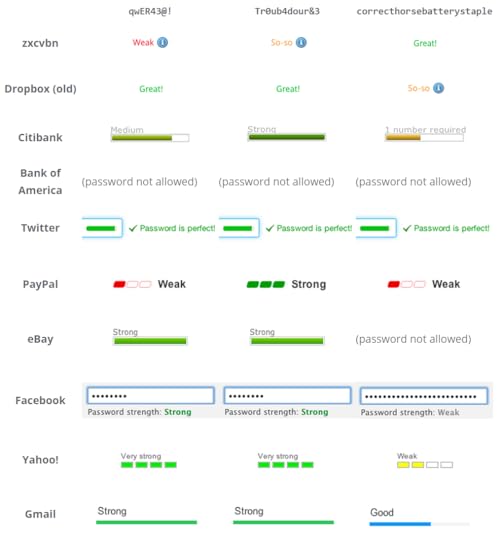

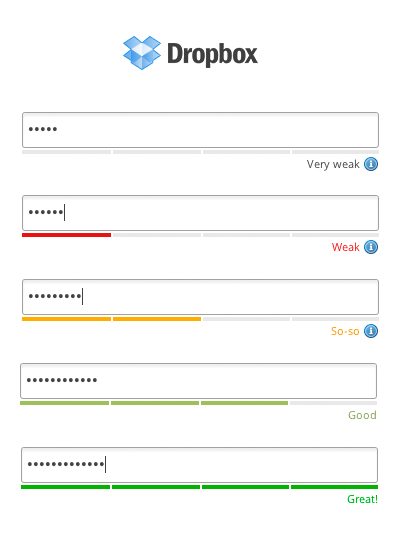

This is commonly done with an ambient password strength meter, which provides real time feedback as you type.

If you can't avoid storing the password – the first two items I listed above are both about avoiding the need for the user to select a 'new' password altogether – then showing an estimation of password strength as the user types is about as good as it gets.

The easiest way to build a safe password is to make it long. All other things being equal, the law of exponential growth means a longer password is a better password. That's why I was always a fan of passphrases, though they are exceptionally painful to enter via touchscreen in our brave new world of mobile – and that is an increasingly critical flaw. But how short is too short?

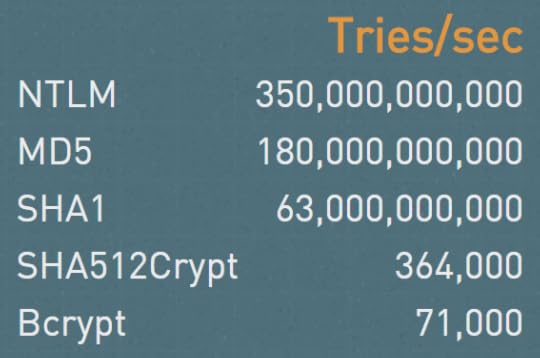

When we built Discourse, I had to select an absolute minimum password length that we would accept. I chose a default of 8, based on what I knew from my speed hashing research. An eight character password isn't great, but as long as you use a reasonable variety of characters, it should be sufficiently resistant to attack.

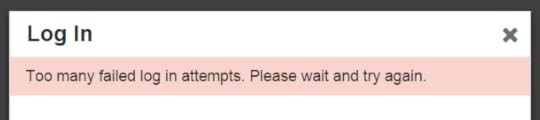

By attack, I don't mean an attacker automating a web page or app to repeatedly enter passwords. There is some of this, for extremely common passwords, but that's unlikely to be a practical attack on many sites or apps, as they tend to have rate limits on how often and how rapidly you can try different passwords.

What I mean by attack is a high speed offline attack on the hash of your password, where an attacker gains access to a database of leaked user data. This kind of leak happens all the time. And it will continue to happen forever.

If you're really unlucky, the developers behind that app, service, or website stored the password in plain text. This thankfully doesn't happen too often any more, thanks to education efforts. Progress! But even if the developers did properly store a hash of your password instead of the actual password, you better pray they used a really slow, complex, memory hungry hash algorithm, like bcrypt. And that they selected a high number of iterations. Oops, sorry, that was written in the dark ages of 2010 and is now out of date. I meant to say scrypt. Yeah, scrypt, that's the ticket.

Then we're safe? Right? Let's see.

Start with a a truly random 8 character password. Note that 8 characters is the default size of the generator, too. I got U6zruRWL.

Plug it into the GRC password crack checker.

Read the "Massive Cracking Array" result, which is 2.2 seconds.

Go lay down and put a warm towel over your face.

You might read this and think that a massive cracking array is something that's hard to achieve. I regret to inform you that building an array of, say, 24 consumer grade GPUs that are optimized for speed hashing, is well within the reach of the average law enforcement agency and pretty much any small business that can afford a $40k equipment charge. No need to buy when you can rent – plenty of GPU equipped cloud servers these days. Beyond that, imagine what a motivated nation-state could bring to bear. The mind boggles.

Even if you don't believe me, but you should, the offline fast attack scenario, much easier to achieve, was hardly any better at 37 minutes.

Perhaps you're a skeptic. That's great, me too. What happens when we try a longer random.org password on the massive cracking array?

9 characters2 minutes

10 characters2 hours

11 characters6 days

12 characters1 year

13 characters64 years

The random.org generator is "only" uppercase, lowercase, and number. What if we add special characters, to keep Q*Bert happy?

8 characters1 minute

9 characters2 hours

10 characters1 week

11 characters2 years

12 characters2 centuries

That's a bit better, but you can't really feel safe until the 12 character mark even with a full complement of uppercase, lowercase, numbers, and special characters.

It's unlikely that massive cracking scenarios will get any slower. While there is definitely a password length where all cracking attempts fall off an exponential cliff that is effectively unsurmountable, these numbers will only get worse over time, not better.

So after all that, here's what I came to tell you, the poor, beleagured user:

Unless your password is at least 12 characters, you are vulnerable.

That should be the minimum password size you use on any service. Generate your password with some kind of offline generator, with diceware, or a passphrase approach – whatever it takes, but make sure your passwords are all at least 12 characters.

Now, to be fair, as I alluded to earlier all of this does depend heavily on the hashing algorithm that was selected. But you have to assume that every password you use will be hashed with the lamest, fastest hash out there. One that is easy for GPUs to calculate. There's a lot of old software and systems out there, and will be for a long, long time.

And for developers:

Pick your new password hash algorithms carefully, and move all your old password hashing systems to much harder to calculate hashes. You need hashes that are specifically designed to be hard to calculate on GPUs, like scrypt.

Even if you pick the "right" hash, you may be vulnerable if your work factor isn't high enough. Matsano recommends the following:

scrypt: N=2^14, r=8, p=1

bcrypt: cost=11

PBKDF2 with SHA256: iterations=86,000

But those are just guidelines; you have to scale the hashing work to what's available and reasonable on your servers or devices. For example, we had a minor denial of service bug in Discourse where we allowed people to enter up to 20,000 character passwords in the login form, and calculating the hash on that took, uh … several seconds.

Now if you'll excuse me, I need to go change my PayPal password.

[advertisement] What's your next career move? Stack Overflow Careers has the best job listings from great companies, whether you're looking for opportunities at a startup or Fortune 500. You can search our job listings or create a profile and let employers find you.

April 3, 2015

Given Enough Money, All Bugs Are Shallow

Eric Raymond, in The Cathedral and the Bazaar, famously wrote

Given enough eyeballs, all bugs are shallow.

The idea is that open source software, by virtue of allowing anyone and everyone to view the source code, is inherently less buggy than closed source software. He dubbed this "Linus's Law".

Insofar as it goes, I believe this is true. When only the 10 programmers who happen to work at your company today can look at your codebase, it's unlikely to be as well reviewed as a codebase that's public to the world's scrutiny on GitHub.

However, the Heartbleed SSL vulnerability was a turning point for Linus's Law, a catastrophic exploit based on a severe bug in open source software. How catastrophic? It affected about 18% of all the HTTPS websites in the world, and allowed attackers to view all traffic to these websites, unencrypted... for two years.

All those websites you thought were secure? Nope. This bug went unnoticed for two full years.

Two years!

OpenSSL, the library with this bug, is one of the most critical bits of Internet infrastructure the world has – relied on by major companies to encrypt the private information of their customers as it travels across the Internet. OpenSSL was used on millions of servers and devices to protect the kind of important stuff you want encrypted, and hidden away from prying eyes, like passwords, bank accounts, and credit card information.

This should be some of the most well-reviewed code in the world. What happened to our eyeballs, man?

In reality, it's generally very, very difficult to fix real bugs in anything but the most trivial Open Source software. I know that I have rarely done it, and I am an experienced developer. Most of the time, what really happens is that you tell the actual programmer about the problem and wait and see if he/she fixes it – Neil Gunton

Even if a brave hacker communities to read the code, they're not terribly likely to spot one of the hard-to-spot problems. Why? Few open source hackers are security experts. – Jeremy Zawodny

The fact that many eyeballs are looking at a piece of software is not likely to make it more secure. It is likely, however, to make people believe that it is secure. The result is an open source community that is probably far too trusting when it comes to security. – John Viega

I think there are a couple problems with Linus's Law:

There's a big difference between usage eyeballs and development eyeballs. Just because you pull down some binaries in a RPM, or compile something in Linux, or even report bugs back to the developers via their bug tracker, doesn't mean you're doing anything at all to contribute to the review of the underlying code. Most eyeballs are looking at the outside of the code, not the inside. And while you can discover bugs, even important security bugs, through usage, the hairiest security bugs require inside knowledge of how the code works.

The act of writing (or cut-and-pasting) your own code is easier than understanding and peer reviewing someone else's code. There is a fundamental, unavoidable asymmetry of work here. The amount of code being churned out today – even if you assume only a small fraction of it is "important" enough to require serious review – far outstrips the number of eyeballs available to look at the code. (Yes, this is another argument in favor of writing less code.)

There are not enough qualified eyeballs to look at the code. Sure, the overall number of programmers is slowly growing, but what percent of those programmers are skilled enough, and have the right security background, to be able to audit someone else's code effectively? A tiny fraction.

Even if the code is 100% open source, utterly mission critical, and used by major companies in virtually every public facing webserver for customer security purposes, we end up with critical bugs that compromise everyone. For two years!

That's the lesson. If we can't naturally get enough eyeballs on OpenSSL, how does any other code stand a chance? What do we do? How do we get more eyeballs?

The short term answer was:

Create more alternatives to OpenSSL for ecosystem diversity.

Improve support and funding for OpenSSL.

These are both very good things and necessary outcomes. We should be doing this for all the critical parts of the open source ecosystem people rely on.

But what's the long term answer to the general problem of not enough eyeballs on open source code? It's something that will sound very familar to you, though I suspect Eric Raymond won't be too happy about it.

Money. Lots and lots of money.

Increasingly, companies are turning to commercial bug bounty programs. Either ones they create themselves, or run through third party services like Bugcrowd, Synack, HackerOne, and Crowdcurity. This means you pay per bug, with a larger payout the bigger and badder the bug is.

Or you can attend a yearly event like Pwn2Own, where there's a yearly contest and massive prizes, as large as hundreds of thousands of dollars, for exploiting common software. Staging a big annual event means a lot of publicity and interest, attracting the biggest guns.

That's the message. If you want to find bugs in your code, in your website, in your app, you do it the old fashioned way: by paying for them. You buy the eyeballs.

While I applaud any effort to make things more secure, and I completely agree that security is a battle we should be fighting on multiple fronts, both commercial and non-commercial, I am uneasy about some aspects of paying for bugs becoming the new normal. What are we incentivizing, exactly?

Money makes security bugs go underground

There's now a price associated with exploits, and the deeper the exploit and the lesser known it is, the more incentive there is to not tell anyone about it until you can collect a major payout. So you might wait up to a year to report anything, and meanwhile this security bug is out there in the wild – who knows who else might have discovered it by then?

If your focus is the payout, who is paying more? The good guys, or the bad guys? Should you hold out longer for a bigger payday, or build the exploit up into something even larger? I hope for our sake the good guys have the deeper pockets, otherwise we are all screwed.

I like that Google addressed a few of these concerns by making Pwnium, their Chrome specific variant of Pwn2Own, a) no longer a yearly event but all day, every day and b) increasing the prize money to "infinite". I don't know if that's enough, but it's certainly going in the right direction.

Money turns security into a "me" goal instead of an "us" goal

I first noticed this trend when one or two people reported minor security bugs in Discourse, and then seemed to hold out their hand, expectantly. (At least, as much as you can do something like that in email.) It felt really odd, and it made me uncomfortable.

Am I now obligated, on top of providing a completely free open source project to the world, to pay people for contributing information about security bugs that make this open source project better? Believe me, I was very appreciative of the security bug reporting, and I sent them whatever I could, stickers, t-shirts, effusive thank you emails, callouts in the code and checkins. But open source isn't supposed to be about the money… is it?

Perhaps the landscape is different for closed-source, commercial products, where there's no expectation of quid pro quo, and everybody already pays for the service directly or indirectly anyway.

No Money? No Security.

If all the best security researchers are working on ever larger bug bounties, and every major company adopts these sorts of bug bounty programs, what does that do to the software industry?

It implies that unless you have a big budget, you can't expect to have great security, because nobody will want to report security bugs to you. Why would they? They won't get a payday. They'll be looking elsewhere.

A ransomware culture of "pay me or I won't tell you about your terrible security bug" does not feel very far off, either. We've had mails like that already.

Easy money attracts all skill levels

One unfortunate side effect of this bug bounty trend is that it attracts not just bona fide programmers interested in security, but anyone interested in easy money.

We've gotten too many "serious" security bug reports that were extremely low value. And we have to follow up on these, because they are "serious", right? Unfortunately, many of them are a waste of time, because …

The submitter is more interested in scaring you about the massive, critical security implications of this bug than actually providing a decent explanation of the bug, so you'll end up doing all the work.

The submitter doesn't understand what is and isn't an exploit, but knows there is value in anything resembling an exploit, so submits everything they can find.

The submitter can't share notes with other security researchers to verify that the bug is indeed an exploit, because they might "steal" their exploit and get paid for it before they do.

The submitter needs to convince you that this is an exploit in order to get paid, so they will argue with you about this. At length.

The incentives feel really wrong to me. As much as I know security is incredibly important, I view these interactions with an increasing sense of dread because they generate work for me and the returns are low.

What can we do?

Fortunately, we all have the same goal: make software more secure.

So we should view bug bounty programs as an additional angle of attack, another aspect of "defense in depth", perhaps optimized a bit more for commercial projects where there is ample money. And that's OK.

But I have some advice for bug bounty programs, too:

You should have someone vetting these bug reports, and making sure they are credible, have clear reproduction steps, and are repeatable, before we ever see them.

You should build additional incentives in your community for some kind of collaborative work towards bigger, better exploits. These researchers need to be working together in public, not in secret against each other.

You should have a reputation system that builds up so that only the better, proven contributors are making it through and submitting reports.

Encourage larger orgs to fund bug bounties for common open source projects, not just their own closed source apps and websites. At Stack Exchange, we donated to open source projects we used every year. Donating a bug bounty could be a big bump in eyeballs on that code.

I am concerned that we may be slowly moving toward a world where given enough money, all bugs are shallow. Money does introduce some perverse incentives for software security, and those incentives should be watched closely.

But I still believe that the people who will freely report security bugs in open source software because

It is the right thing to do™

and

They want to contribute back to open source projects that have helped them, and the world

… will hopefully not be going away any time soon.

[advertisement] How are you showing off your awesome? Create a Stack Overflow Careers profile and show off all of your hard work from Stack Overflow, Github, and virtually every other coding site. Who knows, you might even get recruited for a great new position!

March 27, 2015

Toward a Better Markdown Tutorial

It's always surprised me when people, especially technical people, say they don't know Markdown. Do you not use GitHub? Stack Overflow? Reddit?

I get that an average person may not understand how Markdown is based on simple old-school plaintext ASCII typing conventions. Like when you're *really* excited about something, you naturally put asterisks around it, and Markdown makes that automagically italic.

But how can we expect them to know that, if they grew up with wizzy-wig editors where the only way to make italic is to click a toolbar button, like an animal?

I am not advocating for WYSIWYG here. While there's certainly more than one way to make italic, I personally don't like invisible formatting tags and I find that WYSIWYG is more like WYCSYCG in practice. It's dangerous to be dependent on these invisible formatting codes you can't control. And they're especially bad if you ever plan to care about differences, revisions, and edit history. That's why I like to teach people simple, visible formatting codes.

We can certainly debate which markup language is superior, but in Discourse we tried to build a rainbow tool that satisifies everyone. We support:

HTML (safe subset)

BBCode (basic subset)

Markdown (full)

This makes coding our editor kind of hellishly complex, but it means that for you, the user, whatever markup language you're used to will probably "just work" on any Discourse site you happen to encounter in the future. But BBCode and HTML are supported mostly as bridges. What we view as our primary markup format, and what we want people to learn to use, is Markdown.

However, one thing I have really struggled with is that there isn't any single great place to refer people to with a simple walkthrough and explanation of Markdown.

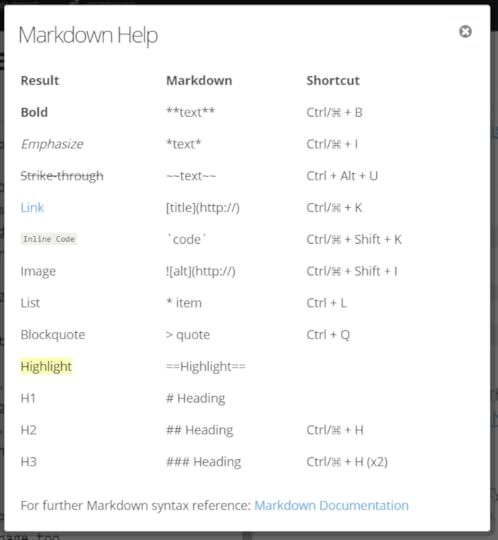

When we built Stack Overflow circa 2008-2009, I put together my best effort at the time which became the "editing help" page:

It's just OK. And GitHub has their Markdown Basics, and GitHub Flavored Markdown help pages. They're OK.

The Ghost editor I am typing this in has an OK Markdown help page too.

But none of these are great.

What we really need is a great Markdown tutorial and reference page, one that we can refer anyone to, anywhere in the world, from someone who barely touches computers to the hardest of hard-core coders. I don't want to build another one for these kinds of help pages for Discourse, I want to build one for everyone. Since it is for everyone, I want to involve everyone. And by everyone, I mean you.

After writing about Our Programs Are Fun To Use – which I just updated with a bunch of great examples contributed in the comments, so go check that out even if you read it already – I am inspired by the idea that we can make a fun, interactive Markdown tutorial together.

So here's what I propose: a small contest to build an interactive Markdown tutorial and reference, which we will eventually host at the home page of commonmark.org, and can be freely mirrored anywhere in the world.

Some ground rules:

It should be primarily in JavaScript and HTML. Ideally entirely so. If you need to use a server-side scripting language, that's fine, but try to keep it simple, and make sure it's something that is reasonable to deploy on a generic Linux server anywhere.

You can pick any approach you want, but it should be highly interactive, and I suggest that you at minimum provide two tracks:

A gentle, interactive tutorial for absolute beginners who are asking "what the heck does Markdown even mean?"

A dynamic, interactive reference for intermediates and experts who are asking more advanced usage questions, like "how do I make code inside a list, or a list inside a list?"

There's a lot of variance in Markdown implementations, so teach the most common parts of Markdown, and cover the optional / less common variations either in the advanced reference areas or in extra bonus sections. People do love their tables and footnotes! We recommend using a CommonMark compatible implementation, but it is not a requirement.

Your code must be MIT licensed.

Judging will be completely at the whim of myself and John MacFarlane. Our decisions will be capricious, arbitrary, probably nonsensical, and above all, final.

We'll run this contest for a period of one month, from today until April 28th, 2015.

If I have hastily left out any clarifying rules I should have had, they will go here.

Of course, the real reward for building is the admiration of your peers, and the knowledge that an entire generation of people will grow up learning basic Markdown skills through your contribution to a global open source project.

But on top of that, I am offering … fabulous prizes!

Let's start with my Recommended Reading List. I count sixteen books on it. As long as you live in a place Amazon can ship to, I'll send you all the books on that list. (Or the equivalent value in an Amazon gift certificate, if you happen to have a lot of these books already, or prefer that.)

Second prize is a CODE Keyboard. This can be shipped worldwide.

Third prize is you're fired. Just kidding. Third prize is your choice of any three books on my reading list. (Same caveats around Amazon apply.)

Looking for a place to get started? Check out:

https://github.com/gjtorikian/markdowntutorial.com and http://markdowntutorial.com/ by Garen Torikian

https://github.com/chrisalley/commonmark-website and http://chrisalley.github.io/commonmark-website/ by Chris Alley

If you want privacy, you can mail your entries to me directly (see the about page here for my email address), or if you are comfortable with posting your contest entry in public, I'll create a topic on talk.commonmark for you to post links and gather feedback. Leaving your entry in the comments on this article is also OK.

We desperately need a great place that we can send everyone to learn Markdown, and we need your help to build it. Let's give this a shot. Surprise and amaze us!

[advertisement] Stack Overflow Careers matches the best developers (you!) with the best employers. You can search our job listings or create a profile and even let employers find you.

March 9, 2015

Our Programs Are Fun To Use

These two imaginary guys influenced me heavily as a programmer.

Instead of guaranteeing fancy features or compatibility or error free operation, Beagle Bros software promised something else altogether: fun.

Playing with the Beagle Bros quirky Apple II floppies in middle school and high school, and the smorgasboard of oddball hobbyist ephemera collected on them, was a rite of passage for me.

Here were a bunch of goofballs writing terrible AppleSoft BASIC code like me, but doing it for a living – and clearly having fun in the process. Apparently, the best way to create fun programs for users is to make sure you had fun writing them in the first place.

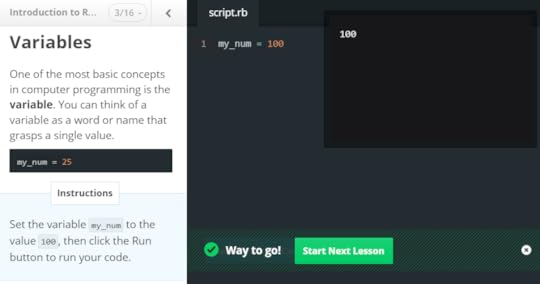

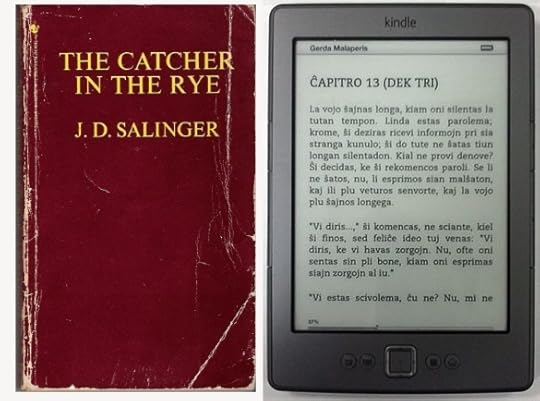

But more than that, they taught me how much more fun it was to learn by playing with an interactive, dynamic program instead of passively reading about concepts in a book.

That experience is another reason I've always resisted calls to add "intro videos", external documentation, walkthroughs and so forth.

One of the programs on these Beagle Bros floppies, and I can't for the life of me remember which one, or in what context this happened, printed the following on the screen:

One day, all books will be interactive and animated.

I thought, wow. That's it. That's what these floppies were trying to be! Interactive, animated textbooks that taught you about programming and the Apple II! Incredible.

This idea has been burned into my brain for twenty years, ever since I originally read it on that monochrome Apple //c screen. Imagine a world where textbooks didn't just present a wall of text to you, the learner, but actually engaged you, played with you, and invited experimentation. Right there on the page.

(Also, if you can find and screenshot the specific Beagle Bros program that I'm thinking of here, I'd be very grateful: there's a free CODE Keyboard with your name on it.)

Between the maturity of JavaScript, HTML 5, and the latest web browsers, you can deliver exactly the kind of interactive, animated textbook experience the Beagle Bros dreamed about in 1985 to billions of people with nothing more than access to the Internet and a modern web browser.

Here are a few great examples I've collected. Screenshots don't tell the full story, so click through and experiment.

Visualizing Algorithms – amazing dynamic visualizations of several interesting and popular algorithms.

Parable of the Polygons – a playable post on the shape of society.

Sight and Light – interactive explanation of 2D visibility calculations.

Rolling Shutters – an animated explanation of the visual glitches introduced in digital cameras by CMOS sensors when taking pictures of fast moving objects.

Sorting.at – a live visualization of common sorting algorithms.

The future of games history is workplace theft – illustrates software history by embedding an emulated, fully playable version of Wolfenstein 3D right in the page.

Feel free to leave links to more examples in the comments, and I'll update this post with the best ones.

(There are also native apps that do similar things; the well reviewed Earth Primer, for example. But when it comes to education, I'm not too keen on platform specific apps which seem replicable in common JavaScript and HTML.)

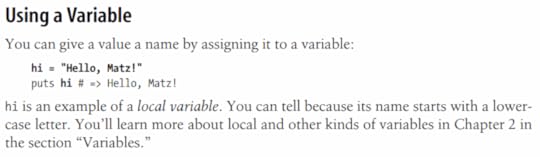

In the bad old days, we learned programming by reading books. But instead of reading this dry old text:

Now we can learn the same concepts interactively, by reading a bit, then experimenting with live code on the same page as the book, and watching the results as we type.

C'mon. Type something. See what happens.

I certainly want my three children to learn from other kids and their teachers, as humans have since time began. But I also want them to have access to a better class of books than I did. Books that are effectively programs. Interactive, animated books that let them play and experiment and create, not just passively read.

I want them to learn, as I did, that our programs are fun to use.

[advertisement] Stack Overflow Careers matches the best developers (you!) with the best employers. You can search our job listings or create a profile and even let employers find you.

January 9, 2015

The God Login

I graduated with a Computer Science minor from the University of Virgina in 1992. The reason it's a minor and not a major is because to major in CS at UVa you had to go through the Engineering School, and I was absolutely not cut out for that kind of hardcore math and physics, to put it mildly. The beauty of a minor was that I could cherry pick all the cool CS classes and skip everything else.

One of my favorite classes, the one I remember the most, was Algorithms. I always told people my Algorithms class was the one part of my college education that influenced me most as a programmer. I wasn't sure exactly why, but a few years ago I had a hunch so I looked up a certain CV and realized that Randy Pausch – yes, the Last Lecture Randy Pausch – taught that class. The timing is perfect: University of Virginia, Fall 1991, CS461 Analysis of Algorithms, 50 students.

I was one of them.

No wonder I was so impressed. Pausch was an incredible, charismatic teacher, a testament to the old adage that your should choose your teacher first and the class material second, if you bother to at all. It's so true.

In this case, the combination of great teacher and great topic was extra potent, as algorithms are central to what programmers do. Not that we invent new algorithms, but we need to understand the code that's out there, grok why it tends to be fast or slow due to the tradeoffs chosen, and choose the correct algorithms for what we're doing. That's essential.

And one of the coolest things Mr. Pausch ever taught me was to ask this question:

What's the God algorithm for this?

Well, when sorting a list, obviously God wouldn't bother with a stupid Bubble Sort or Quick Sort or Shell Sort like us mere mortals, God would just immediately place the items in the correct order. Bam. One step. The ultimate lower bound on computation, O(1). Not just fixed time, either, but literally one instantaneous step, because you're freakin' God.

This kind of blew my mind at the time.

I always suspected that programmers became programmers because they got to play God with the little universe boxes on their desks. Randy Pausch took that conceit and turned it into a really useful way of setting boundaries and asking yourself hard questions about what you're doing and why.

So when we set out to build a login dialog for Discourse, I went back to what I learned in my Algorithms class and asked myself:

How would God build this login dialog?

And the answer is, of course, God wouldn't bother to build a login dialog at all. Every user would already be logged into GodApp the second they loaded the page because God knows who they are. Authoritatively, even.

This is obviously impossible for us, because God isn't one of our investors.

But.. how close can we get to the perfect godlike login experience in Discourse? That's a noble and worthy goal.

Wasn't it Bill Gates who once asked why the hell every programmer was writing the same File Open dialogs over and over? It sure feels that way for login dialogs. I've been saying for a long time that the best login is no login at all and I'm a staunch supporter of logging in with your Internet Driver's license whenever possible. So we absolutely support that, if you've configured it.

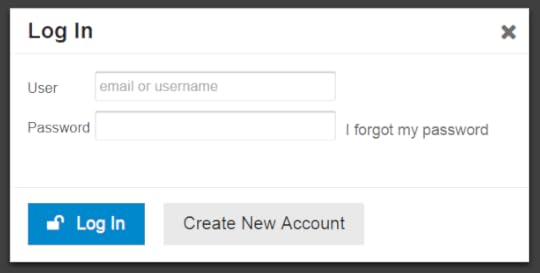

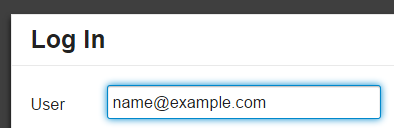

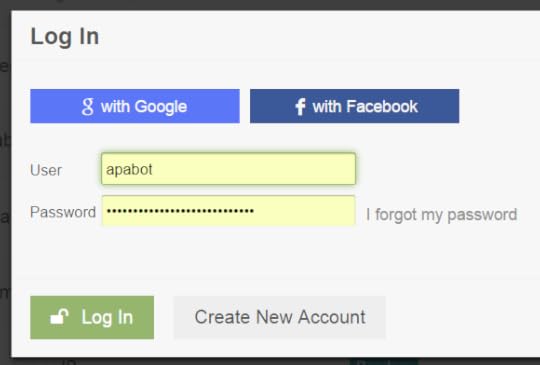

But today I want to focus on the core, basic login experience: user and password. That's the default until you configure up the other methods of login.

A login form with two fields, two buttons, and a link on it seems simple, right? Bog standard. It is, until you consider all the ways the simple act of logging in with those two fields can go wrong for the user. Let's think.

Let the user enter an email to log in

The critical fault of OpenID, as much as as an early login solution, was its assumption that users could accept an URL as their "identity". This is flat out crazy, and in the long run this central flawed assumption in OpenID broke it as a future standard.

User identity is always email, plain and simple. What happens when you forget your password? You get an email, right? Thus, email is your identity. Some people even propose using email as the only login method.

It's fine to have a username, of course, but always let users log in with either their username or their email address. Because I can tell you with 100% certainty that when those users forget their password, and they will, all the time, they'll need that email anyway to get a password reset. Email and password are strongly related concepts and they belong together. Always!

(And a fie upon services that don't allow me to use my email as a username or login. I'm looking at you, Comixology.)

Tell the user when their email doesn't exist

OK, so we know that email is de-facto identity for most people, and this is a logical and necessary state of affairs. But which of my 10 email addresses did I use to log into your site?

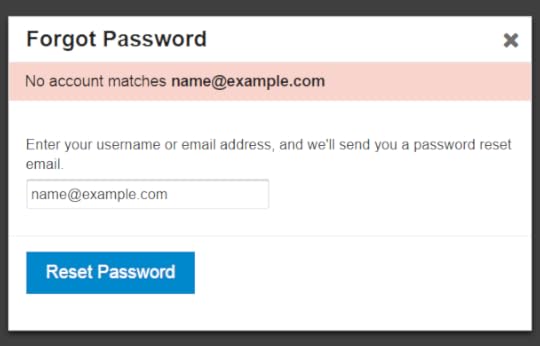

This was the source of a about whether it made sense to reveal to the user, when they enter an email address in the "forgot password" form, whether we have that email address on file. On many websites, here's the sort of message you'll see after entering an email address in the forgot password form:

If an account matches name@example.com, you should receive an email with instructions on how to reset your password shortly.

Note the coy "if" there, which is a hedge against all the security implications of revealing whether a given email address exists on the site just by typing it into the forgot password form.

We're deadly serious about picking safe defaults for Discourse, so out of the box you won't get exploited or abused or overrun with spammers. But after experiencing the real world "which email did we use here again?" login state on dozens of Discourse instances ourselves, we realized that, in this specific case, being user friendly is way more important than being secure.

The new default is to let people know when they've entered an email we don't recognize in the forgot password form. This will save their sanity, and yours. You can turn on the extra security of being coy about this, if you need it, via a site setting.

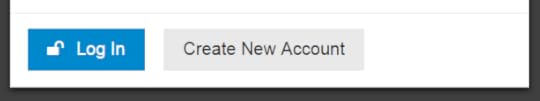

Let the user switch between Log In and Sign Up any time

Many websites have started to show login and signup buttons side by side. This perplexed me; aren't the acts of logging in and signing up very different things?

Well, from the user's perspective, they don't appear to be. This Verge login dialog illustrates just how close the sign up and log in forms really are. Check out this animated GIF of it in action.

We've acknowledged that similarity by having either form accessible at any time from the two buttons at the bottom of the form, as a toggle:

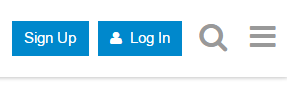

And both can be kicked off directly from any page via the Sign Up and Log In buttons at the top right:

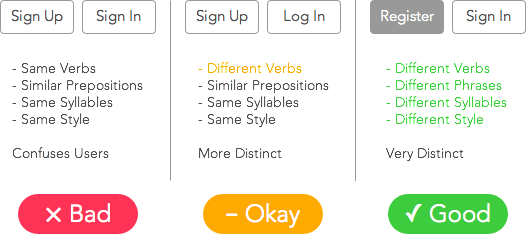

Pick common words

That's the problem with language, we have so many words for these concepts:

Sign In

Log In

Sign Up

Register

Join

Create Account

Get Started

Subscribe

Which are the "right" ones? User research data isn't conclusive.

I tend to favor the shorter versions when possible, mostly because I'm a fan of the whole brevity thing, but there are valid cases to be made for each depending on the circumstances and user preferences.

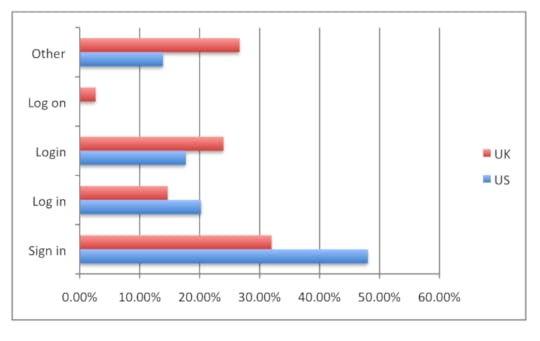

Sign In may be slightly more common, though Log In has some nautical and historical computing basis that makes it worthy:

A couple of years ago I did a survey of top websites in the US and UK and whether they used “sign in”, “log in”, “login”, “log on”, or some other variant. The answer at the time seemed to be that if you combined “log in” and “login”, it exceeded “sign in”, but not by much. I’ve also noticed that the trend toward “sign in” is increasing, especially with the most popular services. Facebook seems to be a “log in” hold-out.

Work with browser password managers

Every login dialog you create should be tested to work with the default password managers in …

Internet Explorer

Chrome

Firefox

Safari

At an absolute minimum. Upon subsequent logins in that browser, you should see the username and password automatically autofilled.

Users rely on these default password managers built into the browsers they use, and any proper modern login form should respect that, and be designed sensibly, e.g. the password field should have type="password" in the HTML and a name that's readily identifable as a password entry field.

There's also LastPass and so forth, but I generally assume if the login dialog works with the built in browser password managers, it will work with third party utilities, too.

Handle common user mistakes

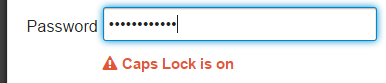

Oops, the user is typing their password with caps lock on? You should let them know about that.

Oops, the user entered their email as name@gmal.com instead of name@gmail.com? Or name@hotmail.cm instead of name@hotmail.com? You should either fix typos in common email domains for them, or let them know about that.

(I'm also a big fan of native browser "reveal password" support for the password field, so the user can verify that she typed in or autofilled the password she expects. Only Internet Explorer and I think Safari offer this, but all browsers should.)

Help users choose better passwords

There are many schools of thought on forcing helping users choose passwords that aren't unspeakably awful, e.g. password123 and iloveyou and so on.

There's the common password strength meter, which updates in real time as you type in the password field.

It's clever idea, but it gets awful preachy for my tastes on some sites. The implementation also leaves a lot to be desired, as it's left up to the whims of the site owner to decide what password strength means. One site's "good" is another site's "get outta here with that Fisher-Price toy password". It's frustrating.

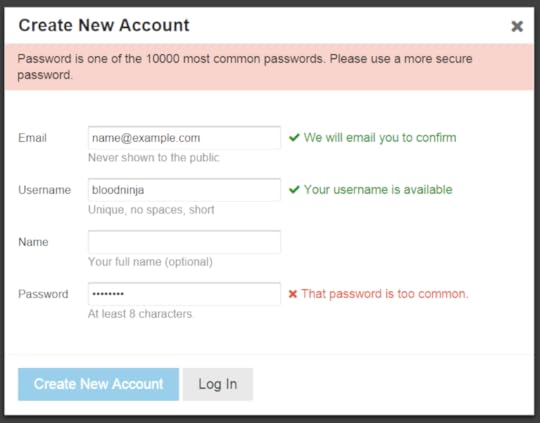

So, with Discourse, rather than all that, I decided we'd default on a solid absolute minimum password length of 8 characters, and then verify the password to make sure it is not one of the 10,000 most common known passwords by checking its hash.

Don't forget the keyboard

I feel like keyboard users are a dying breed at this point, but for those of us that, when presented with a login dialog, like to rapidly type

name@example.com, tab, p4$$w0rd, enter

… please verify that this works as it should. Tab order, enter to submit, etcetera.

Rate limit all the things

You should be rate limiting everything users can do, everywhere, and that's especially true of the login dialog.

If someone forgets their password and makes 3 attempts to log in, or issues 3 forgot password requests, that's probably OK. But if someone makes a thousand attempts to log in, or issues a thousand forgot password requests, that's a little weird. Why, I might even venture to guess they're possibly … not human.

You can do fancy stuff like temporarily disable accounts or start showing a CAPTCHA if there are too many failed login attempts, but this can easily become a griefing vector, so be careful.

I think a nice middle ground is to insert standard pauses of moderately increasing size after repeated sequential failures or repeated sequential forgot password requests from the same IP address. So that's what we do.

Stuff I forgot

I tried to remember everything we went through when we were building our ideal login dialog for Discourse, but I'm sure I forgot something, or could have been more thorough. Remember, Discourse is 100% open source and by definition a work in progress – so as my friend Miguel de Icaza likes to say, when it breaks, you get to keep both halves. Feel free to test out our implementation and give us your feedback in the comments, or point to other examples of great login experiences, or cite other helpful advice.

Logging in involves a simple form with two fields, a link, and two buttons. And yet, after reading all this, I'm sure you'll agree that it's deceptively complex. Your best course of action is not to build a login dialog at all, but instead rely on authentication from an outside source whenever you can.

Like, say, God.

[advertisement] How are you showing off your awesome? Create a Stack Overflow Careers profile and show off all of your hard work from Stack Overflow, Github, and virtually every other coding site. Who knows, you might even get recruited for a great new position!

December 15, 2014

The Evolution of eInk

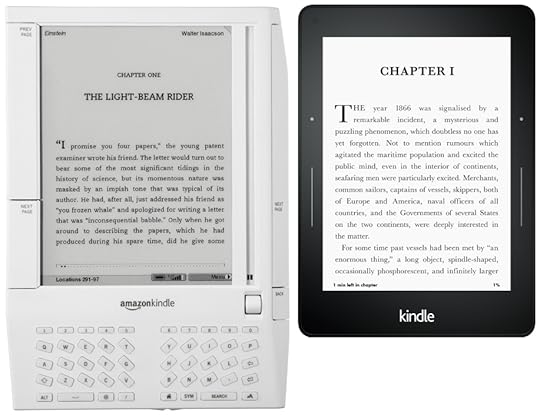

Sure, smartphones and tablets get all the press, and deservedly so. But if you place the original mainstream eInk device from 2007, the Amazon Kindle, side by side with today's model, the evolution of eInk devices is just as striking.

Each of these devices has a 6 inch eInk screen. Beyond that they're worlds apart.

8" × 5.3" × 0.8"

10.2 oz

6.4" × 4.5" × 0.3"

6.3 oz

6" eInk display

167 PPI

4 level greyscale

6" eInk display

300 PPI

16 level greyscale

backlight

256 MB

4 GB

400 Mhz CPU

1 GHz CPU

$399

$199

7 days battery life

USB

6 weeks battery life

WiFi / Cellular

They may seem awfully primitive compared to smartphones, but that's part of their charm – they are the scooter to the motorcycle of the smartphone. Nowhere near as versatile, but as a form of basic transportation, radically simpler, radically cheaper, and more durable. There's an object lesson here in stripping things away to get to the core.

eInk devices are also pleasant in a paradoxical way because they basically suck at everything that isn't reading. That doesn't sound like something you'd want, except when you notice you spend every fifth page switching back to Twitter or Facebook or Tinder or Snapchat or whatever. eInk devices let you tune out the world and truly immerse yourself in reading.

I believe in the broadest sense, bits > atoms. Sure, we'll always read on whatever device we happen to hold in our hands that can display words and paragraphs. And the advent of retina class devices sure made reading a heck of a lot more pleasant on tablets and smartphones.

But this idea of ultra-cheap, pervasive eInk reading devices eventually replacing those ultra-cheap, pervasive paperbacks I used to devour as a kid has great appeal to me. I can't let it go. Reading is Fundamental, man!

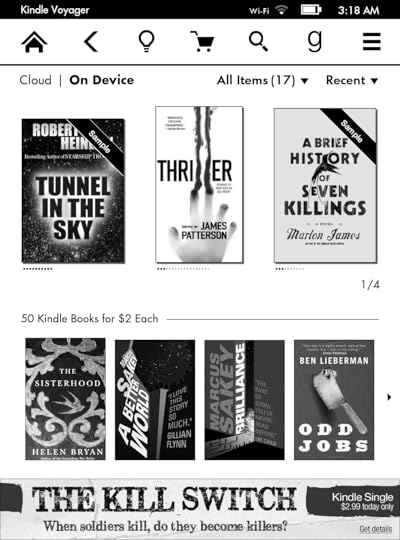

That's why I'm in this weird place where I will buy, sight unseen, every new Kindle eInk device. I wasn't quite crazy enough to buy the original Kindle (I mean, look at that thing) but I've owned every model since the third generation Kindle was introduced in 2010.

I've also been tracking the Kindle prices to see when they can get them down to $49 or lower. We're not quite there yet – the basic Kindle eInk reader, which by the way is still pretty darn amazing compared to that original 2007 model pictured above – is currently on sale for $59.

But this is mostly about their new flagship eInk device, the Kindle Voyage. Instead of being cheap, it's trying to be upscale. The absolute first thing you need to know is this is the first 300 PPI (aka "retina") eInk reader from Amazon. If you're familiar with the smartphone world before and after the iPhone 4, then you should already be lining up to own one of these.

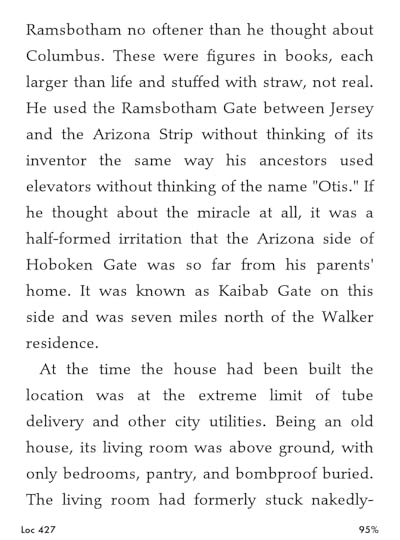

When you experience 300 PPI in eInk, you really feel like you're looking at a high quality printed page rather than an array of RGB pixels. Yeah, it's still grayscale, but it is glorious. Here are some uncompressed screenshots I made from mine at native resolution.

Note that the real device is eInk, so there's a natural paper-like fuzziness that makes it seem even more high resolution than these raw bitmaps would indicate.

I finally have enough resolution to pick a thinner font than fat, sassy old Caecilia.

The backlight was new to the original Paperwhite, and it definitely had some teething pains. The third time's the charm; they've nailed the backlight aspect for improved overall contrast and night reading. The Voyage also adds an ambient light sensor so it automatically scales the backlight to anything from bright outdoors to a pitch-dark bedroom. It's like automatic night time headlights on a car – one less manual setting I have to deal with before I sit down and get to my reading. It's nice.

The Voyage also adds page turn buttons back into the mix, via pressure sensing zones on the left and right bezel. I'll admit I had some difficulty adjusting to these buttons, to the point that I wasn't sure I would, but I eventually did – and now I'm a convert. Not having to move your finger into the visible text on the page to advance, and being able to advance without moving your finger at all, just pushing it down slightly (which provides a little haptic buzz as a reward), does make for a more pleasant and efficient reading experience. But it is kind of subtle and it took me a fair number of page turns to get it down.

In my experience eInk devices are a bit more fragile than tablets and smartphones. So you'll want a case for automatic on/off and basic "throw it in my bag however" paperback book level protection. Unfortunately, the official Kindle Voyage case is a disaster. Don't buy it.

Previous Kindle cases were expensive, but they were actually very well designed. The Voyage case is expensive and just plain bad. Whoever came up with the idea of a weirdly foldable, floppy origami top opening case on a thing you expect to work like a typical side-opening book should be fired. I recommend something like this basic $14.99 case which works fine to trigger on/off and opens in the expected way.

It's not all sweetness and light, though. The typography issues that have plagued the Kindle are still present in full force. It doesn't personally bother me that much, but it is reasonable to expect more by now from a big company that ostensibly cares about reading. And has a giant budget with lots of smart people on its payroll.

This is what text

— Justin Van Slembrou… (@jvanslem) February 6, 2014

looks like on

a kindle.

If you've dabbled in the world of eInk, or you were just waiting for a best of breed device to jump in, the Kindle Voyage is easy to recommend. It's probably peak mainstream eInk. Would recommend, would buy again, will probably buy all future eInk models because I have an addiction. A reading addiction. Reading is fundamental. Oh, hey, $2.99 Kindle editions of The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich? Yes, please.

(At the risk of coming across as a total Amazon shill, I'll also mention that the new Amazon Family Sharing program is amazing and lets me and my wife finally share books made of bits in a sane way, the way we used to share regular books: by throwing them at each other in anger.)

[advertisement] What's your next career move? Stack Overflow Careers has the best job listings from great companies, whether you're looking for opportunities at a startup or Fortune 500. You can search our job listings or create a profile and let employers find you.

November 25, 2014

Because Reading is Fundamental

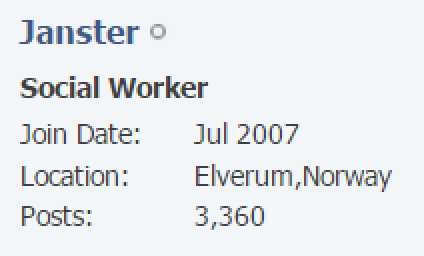

Most discussions show a bit of information next to each user:

What message does this send?

The only number you can control printed next to your name is post count.

Everyone who reads this will see your current post count.

The more you post, the bigger that number next to your name gets.

If I have learned anything from the Internet, it is this: be very, very careful when you put a number next to someone's name. Because people will do whatever it takes to make that number go up.

If you don't think deeply about exactly what you're encouraging, why you're encouraging it, and all the things that may happen as a result of that encouragement, you may end up with … something darker. A lot darker.

Printing a post count number next to every user's name implies that the more you post, the better things are. The more you talk, the better the conversations become. Is this the right message to send to everyone in a discussion? More fundamentally, is this even true?

I find that the value of conversations has little to do with how much people are talking. I find that too much talking has a negative effect on conversations. Nobody has time to listen to the resulting massive stream of conversation, they end up just waiting for their turn to pile on and talk, too. The best conversations are with people who spend most of their time listening. The number of times you've posted in a given topic is not a leaderboard; it's a record of failing to communicate.

Consider the difference between a chat room and a discussion. Chat is a never-ending flow of disconnected, stream of consciousness sentences that you can occasionally dip your toes in to get the temperature of the water, and that's about it. Discussion is the process of lobbing paragraphs back and forth that results in an evolution of positions as your mutual understanding becomes more nuanced. We hope.

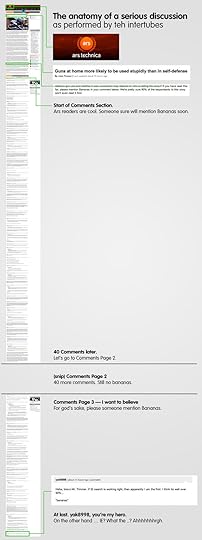

The Ars Banana Experiment

Ars Technica ran a little experiment in 2011. When they posted Guns at home more likely to be used stupidly than in self defense, embedded in the last sentence of the seventh paragraph of the article was this text:

If you have read this far, please mention Bananas in your comment below. We're pretty sure 90% of the respondants to this story won't even read it first.

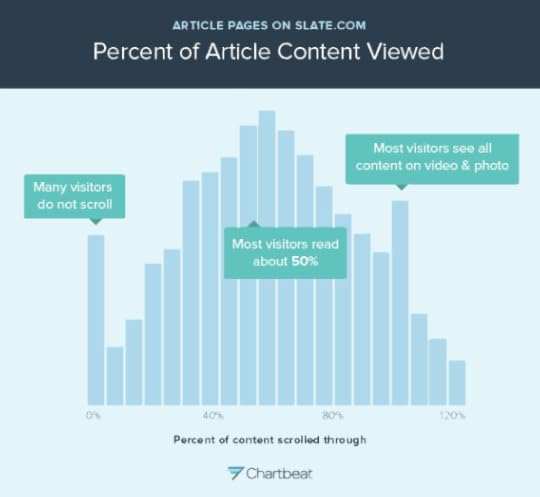

The first person to do this is on page 3 of the resulting discussion, comment number 93. Or as helpfully visualized by Brandon Gorrell:

Plenty of talking, but how many people actually read up to paragraph 7 (of 11) of the source article before they rushed to comment on it?

The Slate Experiment

In You Won't Finish This Article, Farhad Manjoo dares us to read to the end.

Only a small number of you are reading all the way through articles on the Web. I’ve long suspected this, because so many smart-alecks jump in to the comments to make points that get mentioned later in the piece.

But most of us won't.

He collected a bunch of analytics data based on real usage to prove his point:

These experiments demonstrate that we don't need to incentivize talking. There's far too much talking already. We badly need to incentivize listening.

And online, listening = reading. That old school program from my childhood was right, so deeply fundamentally right. Reading. Reading Is Fundamental.

Let's say you're interested in World War II. Who would you rather have a discussion with about that? The guy who just skimmed the Wikipedia article, or the gal who read the entirety of The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich?

This emphasis on talking and post count also unnecessarily penalizes lurkers. If you've posted five times in the last 10 years, but you've read every single thing your community has ever written, I can guarantee that you, Mr. or Mrs. Lurker, are a far more important part of that community's culture and social norms than someone who posted 100 times in the last two weeks. Value to a community should be measured every bit by how much you've read as much as how much you talked.

So how do we encourage reading, exactly?

You could do crazy stuff like require commenters to enter some fact from the article, or pass a basic quiz about what the article contained, before allowing them to comment on that article. On some sites, I think this would result in a huge improvement in the quality of the comments. It'd add friction to talking, which isn't necessarily a bad thing, but it's a negative, indirect way of forcing reading by denying talking. Not ideal.

I have some better ideas.

Remove interruptions to reading, primarily pagination.

Here's a radical idea: when you get to the bottom of the page, load the next damn page automatically. Isn't that the most natural thing to want when you reach the end of the page, to read the next one? Is there any time that you've ever been on the Internet reading an article, reached the bottom of page 1, and didn't want to continue reading? Pagination is nothing more than an arbitrary barrier to reading, and it needs to die a horrible death.

There are sites that go even further here, such as The Daily Beast, which actually loads the next article when you reach the end of the one you are currently reading. Try it out and see what you think. I don't know that I'd go that far (I like to pick the next thing I read, thanks very much), but it's interesting.

Measure read times and display them.

What I do not measure, I cannot display as a number next to someone's name, and cannot properly encourage. In Discourse we measure how long each post has been visible in the browser for every (registered) user who encounters that post. Read time is a key metric we use to determine who we trust, and the best posts that people do actually read. If you aren't willing to visit a number of topics and spend time actually listening to us, why should we talk to you – or trust you.

Forget clicks, forget page loads, measure read time! We've been measuring read times extensively since launch in 2013 and it turns out we're in good company: Medium and Upworthy both recently acknowledged the intrinsic power of this metric.

Give rewards for reading.

I know, that old saw, gamification, but if you're going to reward someome, do it for the right things and the right reasons. For example, we created a badge for reading to the end of a long 100+ post topic. And our trust levels are based heavily on how often people are returning and how much they are reading, and virtually not at all on how much they post.

To feel live reading rewards in action, try this classic New York Times Article. There's even a badge for reading half the article!

Update in real time.

Online we tend to read these conversations as they're being written, as people are engaging in live conversations. So if new content arrives, figure out a way to dynamically rez it in without interrupting people's read position. Preserve the back and forth, real time dynamic of an actual conversation. Show votes and kudos and likes as they arrive. If someone edits their post, bring that in too. All of this goes a long way toward making a stuffy old debate feel like a living, evolving thing versus a long distance email correspondence.

These are strategies I pursued with Discourse, because I believe Reading Is Fundamental. Not just in grade school, but in your life, in my life, in every aspect of online community. To the extent that Discourse can help people learn to be better listeners and better readers – not just more talkative – we are succeeding.

If you want to become a true radical, if you want to have deeper insights and better conversations, spend less time talking and more reading.

[advertisement] Stack Overflow Careers matches the best developers (you!) with the best employers. You can search our job listings or create a profile and even let employers find you.

November 10, 2014

The Tablet Turning Point

Remember how people in the year 2000 used to say how crazy and ridiculous it was, the idea that Anyone Would Ever Run Photoshop in a Web Browser? I mean come on.

Oops.

One of my big bets with Discourse is that eventually, all computers will be tablets of varying size, with performance basically indistinguishable from a two year old desktop or laptop.

Apps are great and all, but there has to be some place for this year's bumper crop of obscene amount of computing superpower to go. I like to use history as my guide, and I believe it's going exactly the same place it did on desktops and laptops — that no-installing-anything friend of every lazy user on the planet, the inevitable path of least resistance, the mobile web browser.

For the last few years, I've been buying every significant tablet device in the run up to the big holiday sales season, and testing them all, to see how many years are left until mobile devices catch up to desktops on general web and JavaScript performance.

How are we doing? Let's benchmark some Discourse client-side Ember JavaScript code:

iPhone 4

June 2011

2031ms

iPhone 5

Sept 2012

600ms

iPhone 5s

Sept 2013

300ms

iPhone 6

Sept 2014

250ms

iPad Air 2

Oct 2014

225ms

My Core i4770k desktop machine scores 180ms in the same benchmark on the latest version of Chrome x64. I'd say we're solidly within striking distance this year.

I don't like to spend a lot of time talking about news and gadgets here, since the advice and commentary will be inevitably outdated and irrelevant within a few years. But this year marks a key turning point for mobile and tablet performance, and I've lived with every iteration of these devices for the last couple of years, so I'll make an exception.

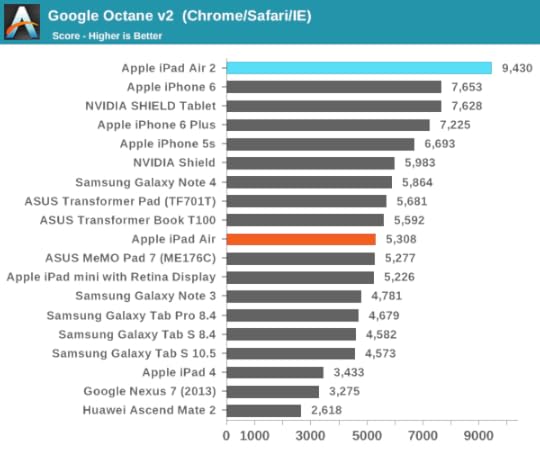

Look at this performance rampage the iPad Air 2 goes on:

Just look at it! All the graphs are like this!

It's hard to believe we now live in a world where the Apple "Premium" is no longer about aesthetics, but raw, unbridled, class-leading performance. And you know what? That's something I can totally get behind.

Anyone who tells you the iPad Air 2 is some kind of incremental update must not actually use theirs. As someone who does regularly use his iPad, I can say without hesitation that this is a massively upgraded device. I grew to hate my old iPad Air because of the memory restrictions; I could barely have three tabs open in Mobile Safari without one of them paging out of memory. Thanks x64 and iOS7!

The bonded screen, touchid, the now-adequate-for-x64 2GB of RAM, the amazingly fast triple core CPU, the GPU, and yeah, it's a little thinner. For performance, nothing else even comes close.

It's so fast I sometimes forget I'm not using my Surface Pro 3 with its 4GB RAM and Core i5 CPU. I get hassled when I bring my Surface to meetings, but I patiently explain that it's a very nice third gen hardware design with a fully integrated keyboard cover, IE11 is a great touch browser, and that I'm mostly using the device as a tablet, as a sneak preview of what iPad 8 performance will look like. Based on today's benchmarks with the iPad Air 2 – chronologically, the iPad "6" – I believe that's about right.

I also purchased a Nexus 9. It's the first device to ship with Android 5 and the vaunted Nvidia Tegra K1.

I'm very impressed with Android 5.0; aesthetically I think it's superior to iOS 8 in a lot of ways, and it is a clear step forward over Android 4. Anyone on older Android devices should definitely upgrade to Android 5 at their first opportunity.

Performance-wise, it is what I've come to expect from Android: erratic. In our Discourse benchmarks, and the latest version of Chrome Android beta, it scores about 750ms, putting it somewhere between the 2011 iPhone 4s and the 2012 iPhone 5. That said, this is the fastest Android device I have ever laid hands on. I just wish it was consistently faster. A lot faster.

To that end, I'd like to ask for your help. We've identified some deep bugs in the Android Chrome V8 engine that cause fairly severe performance issues with JavaScript frameworks like Angular and Ember. (Desktop Chrome performance remains class leading; this is highly specific to the Android version of Chrome.) If you know anyone at Google, please ping them about this and see if it can be escalated. I'd love it if more Android users – including me – could have a better browser experience when using large JavaScript apps.

I hope over the next year the remaining Android 5 performance bumps can be ironed out. I still like the Nexus 9; if you're a big fan of Google services like GMail, Docs, and Maps like I am, I definitely recommend it. The one I have will be a gift to my mom.

[advertisement] How are you showing off your awesome? Create a Stack Overflow Careers profile and show off all of your hard work from Stack Overflow, Github, and virtually every other coding site. Who knows, you might even get recruited for a great new position!

October 23, 2014

What If We Could Weaponize Empathy?

One of my favorite insights on the subject of online community is from Tom Chick:

Here is something I've never articulated because I thought, perhaps naively, it was understood:

The priority for participating on this forum is not the quality of the content. I ultimately don't care how smart or funny or observant you are. Those are plusses, but they're never prerequisites. The priority is on how you treat each other. I expect spats, arguments, occasional insults, and even inevitable grudges. We've all done that. But in the end, I expect you to act like a group of friends who care about each other, no matter how dumb some of us might be, no matter what political opinions some of us hold, no matter what games some of us like or dislike. This community is small enough, intimate enough, that I feel it's a reasonable expectation.

Indeed, disagreement and arguments are inevitable and even healthy parts of any community. The difference between a sane community and a terrifying warzone is the degree to which disagreement is pursued in the community, gated by the level of respect community members have for each other.

In other words, if a fight is important to you, fight nasty. If that means lying, lie. If that means insults, insult. If that means silencing people, silence.

I may be a fan of the smackdown learning model and kayfabe, but I am definitely not a fan of fighting nasty.

I expect you to act like a group of friends who care about each other, no matter how dumb some of us might be, no matter what political opinions some of us hold, no matter what games some of us like or dislike.

There's a word for this: empathy.

One of the first things I learned when I began researching discussion platforms two years ago is the importance of empathy as the fundamental basis of all stable long term communities. The goal of discussion software shouldn't be to teach you how to click the reply button, and how to make bold text, but how to engage in civilized online discussion with other human beings without that discussion inevitably breaking down into the collective howling of wolves.

That's what the discussion software should be teaching you: Empathy.

You. Me. Us. We can all occasionally use a gentle reminder that there is a real human being on the other side of our screen, a person remarkably like us.

I've been immersed in the world of social discussion for two years now, and I keep going back to the well of empathy, time and time again. The first thing we did was start with a solid set of community guidelines on civilized discussion, and I'm proud to say that we ship and prominently feature those guidelines with every copy of Discourse. They are bedrock. But these guidelines only work to the extent that they are understood, and the community helps enforce them.

In Your Community Door, I described the danger of allowing cruel and hateful behavior in your community – behavior so obviously corrosive that it should never be tolerated in any quantity. If your community isn't capable of regularly exorcising the most toxic content, and the people responsible for that kind of content, it's in trouble. Those rare bad apples are group poison.

Hate is easy to recognize. Cruelty is easy to recognize. You do not tolerate these in your community, full stop.

But what about behavior that isn't so obviously corrosive? What about behavior patterns that seem sort of vaguely negative, but … nobody can show you exactly how this behavior is directly hurting anyone? What am I talking about? Take a look at the Flamewarriors Online Discussion Archetypes, a bunch of discussion behaviors that never quite run afoul of the rules, per se, but result in discussions that degenerate, go in circles, or make people not want to be around them.

What we're getting into is shades of grey, the really difficult part of community moderation. I've been working on Discourse long enough to identify some subtle dark patterns of community discussion that – while nowhere near as dangerous as hate and cruelty – are still harmful enough to the overall empathy level of a community that they should be actively recognized when they emerge, and interventions staged.

1. Endless Contrarianism

Disagreement is fine, even expected, provided people can disagree in an agreeable way. But when someone joins your community for the sole purpose of disagreeing, that's Endless Contrarianism.

Example: As an athiest, Edward shows up on a religion discussion area to educate everyone there about the futility of religion. Is that really the purpose of the community? Does anyone in the community expect to defend the very concept of religion while participating there?

If all a community member can seem to contribute is endlessly pointing out how wrong everyone else is, and how everything about this community is headed in the wrong direction – that's not building constructive discussion – or the community. Edward is just arguing for the sake of argument. Take it to debate school.

2. Axe-Grinding

Part of what makes discussion fun is that it's flexible; a variety of topics will be discussed, and those discussions may naturally meander a bit within the context defined by the site and whatever categories of discussion are allowed there. Axe-Grinding is when a user keeps constantly gravitating back to the same pet issue or theme for weeks or months on end.

Example: Sara finds any opportunity to trigger up a GMO debate, no matter what the actual topic is. Viewing Sara's post history, GMO and Monsanto are constant, repeated themes in any context. Sara's negative review of a movie will mention eating GMO popcorn, because it's not really about the movie – it's always about her pet issue.

This kind of inflexible, overbearing single-issue focus tends to drag discussion into strange, unwanted directions, and rapidly becomes tiresome to other participants who have probably heard everything this person has to say on that topic multiple times already. Either Sara needs to let that topic go, or she needs to find a dedicated place (e.g. GMO discussion areas) where others want to discuss it as much as she does, and take it there.

3. Griefing

In discussion, griefing is when someone goes out of their way to bait a particular person for weeks or months on end. By that I mean they pointedly follow them around, choosing to engage on whatever topic that person appears in, and needle the other person in any way they can, but always strictly by the book and not in violation of any rules… technically.

Example: Whenever Joe sees George in a discussion topic, Joe now pops in to represent the opposing position, or point out flaws in George's reasoning. Joe also takes any opportunity to remind people of previous mistakes George made, or times when George was rude.

When the discussion becomes more about the person than the topic, you're in deep trouble. It's not supposed to be about the participants, but the topic at hand. When griefing occurs, the discussion becomes a stage for personal conflict rather than a way to honestly explore topics and have an entertaining discussion. Ideally the root of the conflict between Joe and Sam can be addressed and resolved, or Joe can be encouraged to move on and leave the conflict behind. Otherwise, one of these users needs to find another place to go.

4. Persistent Negativity

Nobody expects discussions to be all sweetness and light, but neverending vitriol and negativity are giant wet blankets. It's hard to enjoy anything when someone's constantly reminding you how terrible the world is. Persistent negativity is when someone's negative contributions to the discussion far outweigh their positive contributions.

Example: Even long after the game shipped, Fred mentions that the game took far too long to ship, and that it shipped with bugs. He paid a lot of money for this game, and feels he didn't get the enjoyment from the game that was promised for the price. He warns people away from buying expansions because this game has a bad track record and will probably fail. Nobody will be playing it online soon because of all the problems, so why bother even trying? Wherever topics happen to go, Fred is there to tell everyone this game is worse than they knew.

If Fred doesn't have anything positive to contribute, what exactly is the purpose of his participation in that community? What does he hope to achieve? Criticism is welcome, but that shouldn't be the sum total of everything Fred contributes, and he should be reasonably constructive in his criticism. People join communities to build things and celebrate the enjoyment of those things, not have other people dump all over it and constantly describe how much they suck and disappoint them. If there isn't any silver lining in Fred's cloud, and he can't be encouraged to find one, he should be asked to find other places to haunt.

5. Ranting

Discussions are social, and thus emotional. You should feel something. But prolonged, extreme appeal to emotion is fatiguing and incites arguments. Nobody wants to join a dry, technical session at the Harvard Debate Club, because that'd be boring, but there is a big difference between a persuasive post and a straight-up rant.

Example: Holly posts at the extremes – either something is the worst thing that ever happened, or the best thing that ever happened. She will post 6 to 10 times in a topic and state her position as forcefully as possible, for as long and as loud as it takes, to as many individual people in the discussion as it takes, to get her point across. The stronger the language in the post, the better she likes it.

If Holly can't make her point in a reasonable way in one post and a followup, perhaps she should rethink her approach. Yelling at people, turning the volume to 11, and describing the situation in the most emotional, extreme terms possible to elicit a response – unless this really is the worst or best thing to happen in years – is a bit like yelling fire in a crowded theater. It's irresponsible. Either tone it down, or take it somewhere that everyone talks that way.

6. Grudges

In any discussion, there is a general expectation that everyone there is participating in good faith – that they have an open mind, no particular agenda, and no bias against the participants or the topic. While short term disagreement is fine, it's important that the people in your community have the ability to reset and approach each new topic with a clean(ish) slate. When you don't do that, when people carry ill will from previous discussions toward the participants or topic into new discussions, that's a grudge.

Example: Tad strongly disagrees with a decision the community made about not creating a new category to house some discussion he finds problematic. So he now views the other leaders in the community, and the moderators, with great distrust. Tad feels like the community has turned on him, and so he has soured on the community. But he has too much invested here to leave, so Tad now likes to point out all the consequences of this "bad" decision often, and cite it as an example of how the community is going wrong. He also follows another moderator, Steve, around because he views him as the ringleader of the original decision, and continually writes long, critical replies to his posts.

Grudges can easily lead to every other dark community pattern on this list. I cannot emphasize enough how important it is to recognize grudges when they emerge so the community can intervene and point out what's happening, and all the negative consequences of a grudge. It's important in the broadest general life sense not to hold grudges; as the famous quote goes (as near as I can tell, attributed to Alcoholics Anonymous)

Holding a grudge is like drinking poison and expecting the other person to die.